The Nimadi-speaking people of Madhya Pradesh A ... · The Nimadi-speaking people of Madhya Pradesh...

Transcript of The Nimadi-speaking people of Madhya Pradesh A ... · The Nimadi-speaking people of Madhya Pradesh...

-

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2012-002

The Nimadi-speaking people of Madhya PradeshA sociolinguistic profile

Kishore Kumar VunnamatlaMathews JohnNelson Samuvel

-

The Nimadi-speaking people of Madhya Pradesh

A sociolinguistic profile

Kishore Kumar Vunnamatla Mathews John Nelson Samuvel

SIL International

2012

SIL Electronic Survey Report 2012-002, January 2012 2012 Kishore Kumar Vunnamatla, Mathews John, Nelson Samuvel, and SIL International All rights reserved

-

2

Contents

ABSTRACT PREFACE 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Geography 1.2 People 1.3 Language 1.4 Purpose and goals

2 DIALECT AREAS 2.1 Lexical similarity 2.1.1 Procedures 2.1.2 Site selection 2.1.3 Results and analysis 2.1.4 Conclusions

2.2 Dialect intelligibility 2.2.1 Procedures 2.2.2 Site Selection 2.2.3 Results And Analysis 2.2.4 Conclusions

3 BILINGUALISM 3.1 Sentence Repetition Testing 3.1.1 Procedures 3.1.2 Demographic details of the area 3.1.3 Results and Analysis

3.2 Questionnaires and observation 4 LANGUAGE USE, ATTITUDES, AND VITALITY 4.1 Procedures 4.2 Results 4.2.1 Language use 4.2.2 Language attitudes 4.2.3 Language vitality

5 SUMMARY OF FINDINGS 5.1 Dialect area study 5.2 Bilingualism study 5.3 Language use, attitudes, and vitality

6 RECOMMENDATIONS 6.1 For a Nimadi language development programme 6.2 For a Nimadi literacy programme

APPENDICES Appendix A: Lexical Similarity Lexical Similarity Counting Procedures Wordlist Information and Informant Biodata International Phonetic Alphabet Wordlist Data

Appendix B: Recorded Text Testing Introduction Snake Story Leopard Story Accident Story Recorded Text Testing in Awlia Recorded Text Testing in Sonipura Recorded Text Testing in Bhorwada Recorded Text Testing in Bhilkheda Recorded Text Testing in Jajamkhedi Recorded Text Testing in Sirpur

Appendix C: Sentence Repetition Testing Hindi Sentence Repetition Test Sentences Hindi SRT Scoring Key Sentence Repetition Testing in Awlia

-

3

Sentence Repetition Testing in Sonipura Appendix D: Questionnaires Language Use, Attitudes, and Vitality Questionnaire Questionnaires in Awlia Questionnaires in Sonipura Questionnaires in Bhilkheda Questionnaires in Jajamkhedi

REFERENCES

-

4

Abstract

The purpose of this sociolinguistic survey among the Nimadi-speaking people was to

assess the need for mother tongue literature development and literacy work. Wordlist

comparisons showed a relatively high degree of lexical similarity among the Nimadi

varieties compared. Recorded Text Testing (RTT) revealed adequate comprehension

of the selected Nimadi varieties in test points across the Nimad region. Responses of

Nimadi speakers to sociolinguistic questionnaires indicated strong vitality of the

language. Nimadi speakers have positive attitudes towards their language, but no

central or prestige variety was identified. Attitudes towards Hindi are slightly

positive; Hindi is seen as the language of education. Although questionnaire subjects

felt they can handle basic tasks in Hindi, there are indications from Sentence

Repetition Testing (SRT) that the Nimadi-speaking population as a whole is probably

not adequately bilingual in Hindi to use available materials effectively.

Preface

This sociolinguistic survey of the Nimadi-speaking people was sponsored and carried

out by the Indian Institute for Cross Cultural Communication (IICCC), which has an

interest in developing mother tongue literature and promoting literacy among the

language groups of India.

The project fieldwork started the last week of May 1999 and continued through the

first half of September 1999. We took a break of three weeks in August to review our

goals as well as do data entry and some preliminary analysis.

We began our work with no contacts in the area, but whenever we needed help, we

met new friends in a timely way. Many people helped us, but it is not possible to

thank them all. Almost all of them were strangers initially. We would like to thank

our main language helper who took care of us during the research; the different block

development officers and village leaders of the area who assisted us in selecting

appropriate sites; and the Catholic priests who helped us complete our tasks,

sometimes by providing accommodation and sometimes by introducing us to people

who could assist us. We are grateful to all of the survey subjects, the experts on the

-

5

Nimadi language, who enabled us to achieve our goals by accepting us in their

villages, patiently listening to the stories, and answering many questions.

Many people contributed to different aspects of this survey such as background

research, project coordination, data entry, and report writing. Every effort has been

made to collect accurate information and present it clearly. The authors take

responsibility for any errors. Corrections to this end would be welcome.

The survey team trusts that this report reflects our brief research in the Nimadi

language accurately and hopes that this work will benefit the Nimadi-speaking people

and contribute to continued Nimadi language development.

-

6 1 Introduction

1 Introduction

1.1 Geography

One of the biggest states located in the heart of India is Madhya Pradesh. The state

ranges from the Chambal River in the north to the Godavari River in the south. The

landscape of the state changes quite often and includes jungles, ravines, hilly regions,

rocky regions, a highland plateau, and great arid plains. Madhya Pradesh is

politically divided into districts, tahsils, blocks, and panchayats.

This sociolinguistic survey was conducted in the Nimad region (Map 1), the uttermost

south-western part of Madhya Pradesh. According to Ramnarayan Upadhyay (1977:52),

Nimad is the joint place for north and south India where Aryans and non-Aryans were

mingled with one another. Nim means half and perhaps Ary refers to Aryans, which

may be why the people were called Nim-ary. Secondly, the Nimad region is further south

and at a lower elevation than the Malwa region, so it was called Nimnagami, which may

mean lower parts. Some other sources report that Nimad is derived from Neem ki Ad,

which means Shade of Neem, since there are many neem trees in the area.

Map 1. The Nimad

MAHARASHT

GUJARAT

RAJASTHAN UTTAR PRADESH

BIHAR

ORISSA

ANDHRA PRADESH

INDIA

Key

State boundary

Nimad region

GUJARAT Neighbouring states

-

1.2 People 7

The Nimad region is located roughly from 21.50 to 22.40 degrees north latitude and

74.50 to 77.00 degrees east longitude, and is spread between the mountain ranges

Vindhya and Satpura and the rivers Narmada and Tapi or Tapti to the north and

south respectively. The regions that border Nimad are Malwa in the north, Khandesh

in the south, Gujarat in the west, and Hoshangabad in the east. The Nimad is

politically divided into Khandwa, Khargone, Barwani, and the southern part of Dhar

districts. These four districts (Map 2) were traversed during this survey and are listed

along with tahsils visited in Table 1. The present Khandwa district was formerly

called East Nimad and the present Khargone and Barwani districts were formerly

called West Nimad. Although the names have officially changed, these former names

are still in common use.

Table 1. The Nimad and its political divisions

State Districts Tahsils Madhya Pradesh Khandwa Khandwa Pandhana Burhanpur Harsud Khargone Khargone Kasrawad Maheshwar Badwah Sanawad Bikhangaon Barwani Barwani Sendhwa Rajpur Dhar Kukshi Manawar Dhar

Nimad is a part of the larger region called Bhilanchal or Bhil country, as some

scholars refer to the tribal area of western India. A good part of this survey was in

areas that are not very hilly. The medical and transport facilities are minimal in the

rural areas.

1.2 People

People in Nimad are of different caste groups and tribes and thus do not have a

general people group name, but the Nimadi language binds them together. The

Bhilala, Korku, Gond Ramcha, and Barela are Scheduled Tribes (ST). Balai is a

-

8 1 Introduction

Scheduled Caste (SC). Other Backward Class (OBC) and General Caste (GC)1 groups

are also common. Singh and Manoharan (1993:324) mention that the following

people groups reportedly speak Nimadi: Nahal (ST); Dhed Bawa and Zamral (SC); and

Jangada Porwal, Mavi, Newa Jain, Salvi, and Srimali Vaishya Baniya (OC). However,

during this survey, the researchers could not locate Nimadi speakers from any of

these groups except the Srimali Vaishya Baniya.

The people in Nimad have their own traditional identity, but in recent times, because

of modernisation and the influence of the media, these people are slowly adopting

changes and joining the mainstream. Nimadi speakers celebrate all major Hindu

festivals, but they also have their own festival called Gannagoria. Many people are

animists; some of them believe in sacrifices and still practice them. Because of the

caste hierarchy, untouchability is also present among them. Illiteracy and poverty

prevail among the Scheduled Castes (Singh 1993) and Scheduled Tribes (Singh 1994).

The Madhya Pradesh government has introduced several development programmes to

help uplift these people.

The estimated literacy rate is fairly low among Nimadi speakers; it could be less than

45 per cent overall. Nevertheless, because of their better opportunities for education,

the literacy rate among Nimadi speakers is generally higher than that of the other

tribals in the region.

Though some publications and audio-cassettes have helped Nimadi language

development to some extent, it is not widely publicised. Devanagari script is used to

write the language. The state government has started schools all over the region, but

children face much difficulty; in the fourth and fifth standards, they often give up

studies. The reason could be that the teaching is in Hindi and the teachers are often

outsiders. On the other hand, those who get good education speak Hindi, the state

language, fairly well. Men generally have higher literacy levels than women.

1The terms Scheduled Tribe, Scheduled Caste, Other Backward Class, and General Caste are official

designations made by the government. These designations qualify members of the groups for certain

types of economic and social development.

-

1.3 Language 9

1.3 Language

Madhya Pradesh is home to many languages, one of which is Nimadi. The language

name is Nimadi because it is spoken in the region of Nimad (Ramnarayan 1977:52).

Though Nimadi is the mother tongue of some tribals, people from different caste

groups live in this large area and also speak Nimadi, thus making it a distinguished

regional language. The Ethnologue

(http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=noe, accessed 8 February

2010) gives Nimadis linguistic classification as Indo-European, Indo-Iranian, Indo-

Aryan, Central zone, Rajasthani, Unclassified. The Ethnologue notes alternate

spellings for the language as Nemadi and Nimari, and also mentions a dialect called

Bhuani. Grierson (1907:60) states, Nimadi is really a form of the Malvi dialect of

Rajasthani, but it has such marked peculiarities of its own that it must be considered

separately. It has fallen under the influence of the neighbouring Gujarati and Bhil

languages, and also of the Khandesi which lies to its south.

Nimadi functions as the main language for intra-group and inter-group

communication for Nimadi speakers. Hindi, the state language of Madhya Pradesh

and a widely used language of north India, is commonly spoken across the Nimad

area. Nimadi speakers use Hindi mainly in education and for communication with

outsiders. Malvi is another regional language, and Gujarati, Marathi, and Rajasthani

are the neighbouring state languages. In addition to the main languages, several other

languages are indigenous to the Nimad. Table 2 shows the changing population of

Nimadi speakers through the decades according to Census of India records.

Table 2. Census figures of Nimadi speakers

Year Number of speakers 1901 474,777 1911 361,217 1921 275,088 1931 398,060 1951 291,174 1961 527,091 1971 794,246 1981* 1,045,782 1991* 1,297,318

*The 1981 and 1991 population figures are projected from the census because the researchers were not able to get the exact census data.

-

10 1 Introduction

Table 2 shows that from 1901 to 1951 the population figures for Nimadi speakers

have ups and downs, but from 1951 to 1991 there is a sharp increase. This may be

due to population changes and may also be affected by peoples willingness to claim

Nimadi as their mother tongue. The important point is that numerically the Nimadi

language does not appear to be dying out but rather is increasing.

All India Radio has a daily broadcast in Nimadi from its Bhopal and Indore stations.

There is a television broadcast in Nimadi from a Bhopal station. Audio-cassettes of

Nimadi folk songs have been produced. Catholics working in the area produce some

religious cassettes.

Once a week some articles in Nimadi are printed in a Hindi newspaper called Nayi

Duniya. There is a thesis prepared about Nimadi folk songs by Father Norbat, who

previously lived in Indore. Log Sagithya Samagra is a Nimadi book by Ramnarayan

Upadhyaya. Gouri Shankar compiled a Nimadi songbook entitled Seva Ki Lagayar.

Bombay University published a book by Stephen Hooks in Nimadi entitled Children

of Hari.

1.4 Purpose and goals

The purpose of this sociolinguistic survey among the Nimadi-speaking people was to

assess the need for mother tongue literature development and literacy work. If there

was a need for a language programme, a subsequent purpose was to determine

whether there was a central or standard variety of Nimadi in which language

development could be carried out. To fulfil this overall purpose and to guide the

course of research, the following goals for the project were devised.

1. To locate the geographical areas where Nimadi-speaking people are living.

2. To examine the differences, if any, among Nimadi speech varieties.

3. To study the lexical relationship between Nimadi and other neighbouring

languages.

4. To investigate the levels of bilingualism in Hindi among Nimadi speakers.

5. To study the language use of Nimadi speakers in different domains, their attitudes

towards Nimadi and Hindi, and the vitality of Nimadi.

-

2.1 Lexical similarity 11

2 Dialect Areas

2.1 Lexical similarity

2.1.1 Procedures

One method of gauging the relationship among speech varieties is to compare the

degree of similarity in their vocabularies. This is referred to as lexical similarity.

Speakers of varieties that have more terms in common (thus a higher percentage of

lexical similarity) generally, though not always, understand one another better than

do speakers of varieties that have fewer terms in common. Since only elicited words

and simple verb constructions are analysed by this method, lexical similarity

comparisons alone cannot indicate how well certain speech communities understand

one another. It can, however, assist in obtaining a broad perspective of the

relationships among speech varieties and give support for results using more

sophisticated testing methods, such as comprehension studies.

The tool used for determining lexical similarity in this survey was a 210-item wordlist

that has been standardised and contextualised for use in sociolinguistic surveys of this

type in South Asia. The elicited words were transcribed using the International

Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) shown in Appendix . Each wordlist was compared with every

other wordlist, item by item, to determine whether they were phonetically similar.

Those words that were judged similar were grouped together. This process of

evaluation was carried out according to standards set forth in Blair (1990:3033). For

a description of the criteria and procedures used in determining lexical similarity,

refer to Appendix .

2.1.2 Site selection

Eighteen wordlists from several sites (Error! Reference source not found.) were

compared for this lexical similarity study. Ten wordlists were collected during

this survey and eight were from previous surveys done in this area. Since Nimadi

is a regional language, sites for wordlist collection were selected to represent not

only different groups such as SC, ST, OBC, and GC, but also to represent

urban/rural and geographical variation.

-

12 2 Dialect Areas

Map 2. Wordlist Sites

Three Nimadi wordlists are from previous surveys; one wordlist is from the Bhil

country survey (Maggard et. al. 1998) and two are from the Bareli survey (Vinod

Wilson Varkey, personal communication). Wordlists from the neighbouring

languages Parya Bhilali and Malvi were also compared. Three standard wordlists

from the state languages Hindi, Gujarati, and Marathi were included in the

comparisons as well.

From the Nimad, two wordlists were collected from Khandwa district, three from

Barwani district, four from Khargone district, and two from the southern part of Dhar

district. This covered several of the caste groups, most of the geographical area, and

urban and rural sites. It was possible to collect many wordlists from interior places

during this survey. To provide better reliability, three wordlists were checked with

second mother tongue speakers in the same sites.

MAHARASHTRA

MADHYA PRADESH

KHARGONE

BARWANI

DHAR

Bhilkheda Khajuri

Bhorwad

a Kupdol

Sonipura

Balekhad

Maheshwa

Awlia

Awlia

Jajamkhedi

INDORE

Badgav

KHANDWA Sirpur

Melgav

Rupkheda

Key

State boundary

District boundary

District headquarters

* Wordlist from this survey

Wordlist from previous survey

-

2.1 Lexical

similarity

13

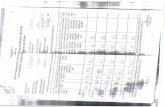

Table 3. Speech variety, location, and origin of wordlists

No. Language Village Urban/Rural Communities Tahsil District Geographical State WL ob-

tained in 1 Nimadi Sonipura Rural but

developed Balai (SC), Patidar (General)

Khargone Khargone Central MP This Project

2 Nimadi Sonipura Rural but developed

Patidar (OBC) Khargone Khargone Central MP This Project

3 Nimadi Balkhad Rural General Kasrawad Khargone Central-North MP This Project 4 Nimadi Jajamkhedi Rural/Urban OBC Manawar Dhar North MP This Project 5 Nimadi Bhilkheda Rural ST-Bhilala Barwani Barwani West MP This Project 6 Nimadi Awlia Rural ST-Bhilala Dhar Dhar North MP This Project 7 Nimadi Khajuri Rural ST-Bhilala Rajpur Barwani West MP This Project 8 Nimadi Maheshwar Urban ST-Bhilala Kasarawad Khargone Central-North MP Bareli-1999 9 Nimadi Rupkheda Urban General Sanawad Khagone East MP This Project 10 Nimadi Khargone Urban Not known Khargone Khargone Central MP Bhil Country-

1998 11 Nimadi Awlia Rural but

developed Balai (SC) Khandwa Khandwa East MP Bareli-1999

12 Nimadi Sirpur,Melgav* Rural ST-Bhilala Harsud Khandwa East MP This Project 13 Nimadi Kupdol,Badgav* Rural/Urban OBC Khargone Khargone Central MP This Project 14 Parya

Bhilali Bhorwada Rural Parya-Bhilala Rajpur Barwani Central-West MP Bareli 1999

15 Malvi Thillor Khurd Indore Indore MP Bhil Country-1998

16 Hindi Standard 17 Gujarati Standard 18 Marathi Standard

*In Sirpur, there were two informants, one from Sirpur and one from Melgav, which is three kilometres from Sirpur. In Kupdol, there were two informants, one from Kupdol and one from Badgav, which is eight kilometres from Kupdol.

-

14 2 Dialect Areas

Table 3 gives the speech variety, location, and origin of the wordlists utilised in

this project. The sampling is listed according to different caste groups,

urban/rural sites, and geographic locations. The table is ordered by speech

variety and the state in which the wordlist site is located. Further details about

each wordlist and its informant, as well as phonetic transcriptions of the

wordlists, are given in Appendix .

2.1.3 Results and analysis

Overall results

The lexical similarity percentages for the speech varieties under consideration are

shown in Table 4. As much as possible in this chart, varieties are ordered by

similarity percentages, with the highest being placed nearer to the top.

Table 4. Lexical similarity percentages matrix

Nimadi-Sonipura-Balai-Khargone 94 Nimadi-Sonipura-Patidar-Khargone 90 88 Nimadi-Balkhad-Brahmin-Khargone 86 86 87 Nimadi-Bhilkheda-Bhilala-Barwani 87 85 86 88 Nimadi-Awlia (Dhar)-Bhilala-Dhar 86 85 88 87 83 Nimadi-Jajamkhedi-OBC-Dhar 87 85 86 82 85 81 Nimadi-Khajuri-Bhilala-Barwani 86 83 85 85 84 83 83 Nimadi-Maheshwar-Bhilala-Khargone 87 83 84 83 84 81 81 85 Nimadi-Rupkheda-Brahmin-Khargone 85 82 83 82 85 83 82 86 85 Nimadi-Khargone-General-Khargone 84 85 85 83 83 80 80 83 84 82 Nimadi-Awlia-Balai-Khandwa 84 81 84 78 79 77 77 75 78 74 80 Nimadi-Sirpur-OBC-Khandwa 84 80 83 77 75 79 76 75 79 74 74 78 Nimadi-Kupdol-Darbar, OBC-Khargone 79 78 80 80 78 79 79 78 75 78 74 73 74 Parya Bhilali-Bhorwada-Barwani 74 73 73 72 74 71 75 73 73 74 73 69 64 67 Malvi-Thillor Khurd-Indore 72 70 74 74 72 70 70 77 73 75 77 66 62 65 67 Hindi-Standard 63 63 65 63 62 62 62 64 61 64 63 60 56 57 64 66 Gujarati-Standard 55 54 58 53 54 54 53 54 56 56 56 49 51 51 52 61 60 Marathi-Standard

When using the lexical similarity counting procedures put forth in Blair (1990:30

33), it has been found, generally speaking, that speech varieties that have less

than 60 per cent lexical similarity with each other are unlikely to be intelligible

(Blair 1990:20). The overall lexical similarity percentages among all Nimadi

wordlists ranged from 74 to 94 per cent, indicating that they may all be

considered related varieties of the same language. The Nimadi varieties of

Khargone district have the highest lexical similarity percentages with most of the

other Nimadi varieties surveyed.

-

2.1 Lexical similarity 15

The Kupdol and Sirpur wordlists show percentages mostly in the 70s with the other

Nimadi varieties. The researchers feel that the Kupdol wordlist is perhaps the least

reliable of all the Nimadi wordlists, since it was elicited without the presence of the

local language helper or the more experienced surveyor on the team. However, this

percentage is included with the others since all other wordlists except three also were

not rechecked. The low similarities of the Sirpur wordlist with the other Nimadi

samples are likely because Sirpur is towards the eastern border of the Nimad, where

the influence of other languages is stronger.

The Parya Bhilali wordlist from Bhorwada village shows 73 to 80 per cent similarities

with the Nimadi wordlists. The people of Bhorwada village are Parya Bhilalas who

speak a form of Bhilali as their mother tongue. This form is reportedly closer to

Nimadi than to the other Bhilali varieties. In this village along with Parya Bhilali,

Rathwi is also spoken.

Malvi is a related language and also a neighbouring regional language to Nimadi.

Malvi from Thillor Khurd shows 64 to 75 per cent lexical similarity with the Nimadi

varieties. Nevertheless, scholars who have done research on Malvi consider it a

separate language from Nimadi. Mother tongue speakers of both Nimadi and Malvi

also identify their respective languages as distinct from each other.

The Nimadi varieties are also less similar to Hindi, Gujarati, and Marathi than to one

another. Nimadi has slightly higher lexical similarity percentages with Hindi (62 to

77 per cent) than with Gujarati (56 to 64 per cent) and Marathi (49 to 58 per cent).

Some borrowing of words from all three state languages seems to be present in these

Nimadi varieties. Overlap may also be due to the fact that all are Indo-Aryan

languages. The slightly stronger influence of Hindi may be because it is the state

language of Madhya Pradesh. However, there does not seem to be a notable influence

according to whether the Nimadi wordlist sites are urban or rural.

Results within Nimadi varieties

Within the Nimadi varieties, there was the possibility of influence from geographical

location, caste/tribe, and urban/rural setting on the lexical similarity results. Table 5

shows the lexical similarity percentages across the districts.

-

16 2 Dialect Areas

Table 5. Lexical similarity percentages matrix arranged by districts

Nimadi-Sonipura-Balai

Khargone 94 Nimadi-Sonipura-Patidar 90 88 Nimadi-Balkhad-Brahmin 86 83 85 Nimadi-Maheshwar-Bhilala 87 83 84 85 Nimadi-Rupkheda-Brahmin 85 82 83 86 85 Nimadi-Khargone-General

Barwani 84 80 83 75 79 74 Nimadi-Kupdol-Darbar,OBC 86 86 87 85 83 82 77 Nimadi-Bhilkheda-Bhilala 87 85 86 83 81 82 76 82 Nimadi-Khajuri-Bhilala

Dhar 87 85 86 84 84 85 75 88 85 Nimadi-Awlia(Dhar)Bhilala 86 85 88 83 81 83 79 87 81 83 Nimadi-Jajamkhedi-OBC 84 85 85 83 84 82 74 83 80 83 80 Nimadi-Awlia-Balai

Khandwa 84 81 84 75 78 74 78 78 77 79 77 80 Nimadi Sirpur-OBC Within Khargone district (excluding Kupdol), the lexical similarity percentages are 82

to 94 per cent, within Khandwa district it is 80 per cent, within Barwani district it is

82 per cent, and within Dhar district it is 83 per cent. When comparing similarity

percentages across the districts, the range is 74 to 88 per cent, which is not notably

different from the similarities within the districts.

The lexical similarity comparisons within and across the Nimadi-speaking

communities, summarised in Table 6, also show no notable differences. In fact, the

highest lexical similarity percentage between any two Nimadi varieties is 94 per cent.

These two wordlists come from within the same village but from different castes (SC

Balai and OBC Patidar).

Table 6. Lexical similarity percentages matrix among castes

SC ST OBC General

SC 84% 80%-88% 74%-88% 82%-94%

ST 80%-88% 82%-88% 74%-86% 75%-88%

OBC 74%-88% 74%-86% 77%-79% 74%-88%

GENERAL 82%-94% 75%-88% 74%-88% 82%-88%

2.1.4 Conclusions

For the most part, comparison of these wordlists shows that the Nimadi varieties

spoken in the communities listed in Table 3 appear to be quite similar, based on the

fairly high lexical similarity. This is an indicator that the Nimadi varieties spoken in

the region are not different enough to be considered separate languages. Geography,

caste/tribe, and urban/rural location did not exert any notable influence on lexical

-

2.2 Dialect intelligibility 17

similarity results. The Nimadi varieties are less similar to the state languages in their

respective locations.

2.2 Dialect intelligibility

The researchers believe that an important factor in determining the distinction

between a language and a dialect is how well speech communities can understand

one another. Low intelligibility2 between two speech varieties, even if one has been

classified as a dialect of the other, impedes the ability of one group to understand the

other (Grimes 1996:vi). Thus comprehension testing, which allows a look into the

approximate understanding of natural speech, was an important component of this

research.

2.2.1 Procedures

Recorded Text Testing (RTT) is one tool to help assess the degree to which speakers

of related linguistic varieties understand one another. A three- to five-minute natural,

personal experience narrative is recorded from a mother tongue speaker of the speech

variety in question. It then is evaluated with a group of mother tongue speakers from

the same region by a procedure called Hometown Testing (HTT). This ensures that

the story is representative of the speech variety in that area and is suitable to be used

for testing in other sites.

Mother tongue speakers from other locations and differing speech varieties then listen

to the recorded stories and are asked questions, interspersed in the story, to test their

comprehension. Subjects are permitted to take tests of stories from other locations

only if they perform well on a hometown or control test. This ensures that the test-

taking procedure is understood.

Ten is considered the minimum number of subjects to be given this test, and subjects

responses to the story questions are noted down and scored. A persons score is

2Intelligibility is a term that has often been used to refer to the level of understanding that exists

between speech varieties. The researchers share the view of OLeary (1994) that RTT results should be

discussed as comprehension scores on texts from different dialects, not as intelligibility scores nor as

measures of inherent intelligibility. Thus the term intelligibility has been used sparingly in this

report, with the term comprehension used more frequently.

-

18 2 Dialect Areas

considered a reflection of his comprehension of the text, and the average score of all

subjects at a test point is indicative of the communitys understanding of the speech

variety represented in the story. Included with the test points average score is a

calculation for the variation between individual subjects scores, known as standard

deviation, which helps in interpreting how representative those scores are.

After each story, subjects are asked questions such as how different they felt the

speech was and how much they could understand. These subjective post-RTT

responses give an additional perspective for interpreting the objective test data. If a

subjects answers to these questions are comparable with his or her score, it gives

more certainty to the results. If, however, the post-RTT responses and test score show

some dissimilarity, then this discrepancy can be investigated.

For a fuller description of Recorded Text Testing, refer to Appendix as well as to

Casad (1974). The stories and questions used in the testing also appear in Appendix ,

as do the demographic profiles of the subjects at each test site, the test scores, and

the post-HTT/RTT responses.

2.2.2 Site Selection

In order to understand the dialect intelligibility of selected Nimadi varieties,

three stories were tested in different locations (Error! Reference source not

found.). Out of these three, one story was from a survey of Bareli (Vinod Wilson

Varkey, personal communication) and the other two were collected during this

project. The testing was done in six sites located in four districts. The

information about these three stories is given in Table 7.

Table 7. RTT stories

Story

name

People Language Village District Story obtained

during

Snake Bharud (OBC) Nimadi Sonipura Khargone This survey

Accident Parya Bhilala (ST)

Parya Bhilali/Nimadi

Bhorwada Barwani This survey

Leopard Balai (SC) Nimadi Awlia Khandwa Bareli survey

-

2.2 Dialect intelligibility 19

Map 3. Recorded Text Testing Sites

Sonipura

This village is seven kilometres from Khargone, the district headquarters and the

central part of Nimad. This village contains a mixture of higher and lower castes;

Muslims also live here. The wordlist from this village has the highest lexical

similarities with other Nimadi varieties. The Snake story was therefore collected from

Sonipura and tested in five other sites. The Awlia Leopard story was used in Sonipura

to test the comprehension of that variety.

Awlia

The Awlia Leopard story was collected during a survey of Bareli (Vinod Wilson

Varkey, personal communication). Awlia is in Khandwa district. This story was used

for comprehension testing in five other locations. The Snake story was played in this

site to investigate the intelligibility of the Sonipura Nimadi speech form in Awlia. In

this village Christians and Hindus are present in almost equal populations; a few

Muslims also live there. People from SC, ST, and OBC groups live in this village.

MAHARASHTRA

MADHYA PRADESH

KHARGONE

BARWANI

DHAR

Bhilkheda

Bhorwad

a

Sonipura

Awlia

Jajamkhedi

INDORE

KHANDWA Sirpur

Key State boundary

District boundary

District headquarters

HTT/RTT site

RTT site

-

20 2 Dialect Areas

Bhorwada

Bhorwada is 30 kilometres from Khargone. This village is near the borders of

Khargone and Barwani districts. It has a large concentration of Parya Bhilalas and

their lexical similarity ranges from 73 to 80 per cent with other Nimadi varieties.

Since the Parya Bhilala speech form appeared to have little lexical difference from

Nimadi, one story was collected from the Parya Bhilala community and all three

stories were played at this site to look at the relationship between Parya Bhilali and

selected Nimadi speech varieties.

Bhilkheda

This village is only three kilometres from Barwani town, but is in a rural setting.

Bhilalas are the majority community in this village. The Snake and Leopard stories

were tested among Bhilalas here.

Jajamkhedi

Jajamkhedi was the site selected to represent Dhar district. Jajamkhedi is three

kilometres from Manawar in Dhar district. Malvi is the dominant language in Dhar

district but in the southern part, people speak Nimadi also. This area was beyond the

official boundary of the Nimad area, formed by the Narmada River. Two stories were

tested in this village.

Sirpur

This area represents the far eastern part of Nimad. Sirpur is 35 kilometres distant

from Khandwa, the district headquarters. Christians are the majority community in

this village. Comprehension testing was done among them only. The Snake and

Leopard stories were played in this site to investigate the comprehension of the

Sonipura and Awlia Nimadi speech forms.

2.2.3 Results And Analysis

The RTT results are shown in Table 8. The rows of the table list the villages where

the stories were tested and the columns list each story used for testing.

-

2.2 Dialect intelligibility 21

Table 8. RTT results

Reference Point

Test Point Sonipura-

Nimadi

Snake story

Awlia-Nimadi

Leopard story

Bhorwada-Parya Bhilali

(Nimadi)

Accident story

Sonipura Avg Sd No

99 2 13

90 8 11

Not tested

Bhilkheda Avg Sd No

99 3 13

95 6 12

Not tested

Jajamkhedi Avg Sd No

98 4 10

90 9 8

Not tested

Awlia Avg Sd No

98 4 10

98 4 10

Not tested

Sirpur Avg Sd No

99 3 16

96 5 16

Not tested

Bhorwada Avg Sd No

100 0 11

90 7 11

99 1 11

In interpreting RTT results, three pieces of information are necessary. The first is

average percentage (shown as Avg, which is the mean or average of all the

participants individual scores on a particular story at a particular test site). Also

necessary is a measure of how much individuals scores vary from the community

average, called standard deviation (shown as Sd). The third important piece of

information is the size of the sample, that is, the number of people that were tested

(shown as N). In addition, to be truly representative, a sample should include people

from significant demographic categories, such as men and women, younger and

older, and educated and uneducated. The relationship between test averages and

their standard deviation has been summarised by Blair (1990:25) and can be seen in

Figure 1.

-

22 2 Dialect Areas

Standard Deviation

High Low

Average

score

High Situation 1 Many people understand the story well, but some have difficulty.

Situation 2 Most people understand the story.

Low Situation 3 Many people cannot understand the story, but a few are able to answer correctly.

Situation 4 Few people are able to understand the story.

Figure 1. Relationship between RTT averages and standard deviations

Since results of field-administered methods such as Recorded Text Testing cannot be

completely isolated from potential biases, OLeary (1994) recommends that results from

RTTs not be interpreted in terms of fixed numerical thresholds, but rather be evaluated

in light of other indicators of intelligibility such as lexical similarity, dialect opinions,

and reported patterns of contact and communication. In general, however, RTT mean

scores of around 80 per cent or higher with accompanying low standard deviations3 are

usually taken to indicate that representatives of the test point dialect display adequate

understanding of the variety represented by the recording. Conversely, RTT means below

60 per cent are interpreted to indicate inadequate comprehension.

The following sections highlight the results of comprehension testing, discussed in

terms of the understanding of each story. The discussion basically follows the order of

how extensively stories were tested, though related speech varieties are discussed

together. For all HTTs, the average scores were high and the standard deviations

were low, indicating that the HTTs were valid in all sites. The post-HTT responses

indicated that even for the stories used as control tests but not from the subjects own

village, a majority of the people reported that the story is close to their speech form.

Sonipura Snake story

This story was tested among a total of 73 subjects in six sites. It was very well

understood throughout all test points and among various communities. The storys

topic was simple, straightforward, and interesting. The average scores on this story

were high in all sites. The averages were 98 to100 per cent, with low standard

3Usually ten and below; high standard deviations are about 15 and above.

-

2.2 Dialect intelligibility 23

deviations. The highest average was 100 per cent in Bhorwada among the Parya

Bhilala people. This is interesting in view of the fact that the lexical similarities were

lower between Parya Bhilali and the Nimadi varieties than within Nimadi varieties.

Since Sonipura is near Bhilkheda and Jajamkhedi, the Snake story was tested first in

these locations; subjects scored an average of 99 per cent and 98 per cent

respectively. Therefore this story was used as the control test for subjects from these

villages.

In response to post-RTT questions, many subjects from all the sites except Bhorwada

said this story is from their area and that it was fully understandable to them, with

little or no difference from their own speech. Eighty four per cent (of the 73 subjects)

said the speech is good and 78 per cent said the speech is pure. Some educated

subjects and those who travelled widely said some Hindi words were also used in this

story.

Awlia Leopard story

This story, tested among 68 subjects in six sites, was also very well understood in all

of the locations where it was tested4. The average score was 95 per cent in Bhilkheda

and 90 per cent in Sonipura, Jajamkhedi, and Bhorwada. The standard deviation was

low in each place.

In response to the post-RTT questions, a majority of the subjects said they were able

to understand the story fully, but some subjects said they understood only half.

Most of the subjects said the speech form is a little different or very different from

their own speech form. Most of the subjects said this story is from the Nimad area.

In Sirpur, seven of the subjects said the Leopard storys speech form is nearer to

their own form, six said the Snake story was closer, and three said both stories are

close to their own speech form. In Bhilkeda and Jajamkhedi, a majority of the

subjects said the Sonipura Snake storys speech variety is closer to their own speech

4This story was tested in Awlia as a Hometown Test twice. The first was done during the Bareli survey

(Vinod Wilson Varkey, personal communication). At that time the average score was 99 per cent with

a standard deviation of two. During this survey, the average score was 98 per cent with a standard

deviation of four.

-

24 3 Bilingualism

form than that of the Awlia Leopard story. Some people said both speech forms are

close to their own.

Bhorwada Accident Story

Bhorwada has a larger concentration of Parya Bhilalas and it was reported that the

Parya Bhilala speech form has little difference from Nimadi. Hence Bhorwada was

selected as a test point. This story was tested in no other sites because the goal was

only to discover whether this community could understand the Nimadi varieties

selected for testing.

2.2.4 Conclusions

Comprehension testing revealed that in almost all cases the stories representing the

selected varieties (Sonipura Nimadi of Khargone district and Awlia Nimadi of

Khandwa district) were well understood in the test locations. Subjects from all six test

points around the Nimad region consistently scored well on both stories. This

suggests that Nimadi-speaking people from locations across the Nimad should be able

to adequately comprehend materials based on either of these varieties.

In post-RTT responses, 50 per cent of the subjects said the Sonipura Snake story is

closer to their own speech form than the Awlia Leopard story, while 20 per cent of

the subjects said the speech forms in both stories are close to their own varieties. The

rest of the subjects favoured their respective HTTs.

3 Bilingualism

Bilingualism refers to the knowledge and skills acquired by individuals which enable

them to use a language other than their mother tongue (Blair 1990:52). A second

language may be acquired either formally (as in a school setting) or informally

through other types of contact with speakers of the second language.

Blair (1990:51) further points out, The goal of a study of community bilingualism is

to find out how bilingual the population of a community is. Bilingualism is not a

characteristic which is uniformly distributed. In any community, different individuals

or sections of the community are bilingual to different degrees. It is important to

avoid characterizing an entire community as though such ability were uniformly

-

3.1 Sentence Repetition Testing 25

distributed. It is more accurate to describe how bilingualism is distributed throughout

the community.

Hindi is the official state language and medium for instruction in schools in Madhya

Pradesh, where most of the research for this survey was carried out. Since Hindi has a

great influence in this area, it was important to assess the bilingual proficiency of the

Nimadi-speaking people in Hindi as part of considering the possible need for a

language development programme in Nimadi. The main tool used to gauge

bilingualism in Hindi was the Sentence Repetition Test (SRT). Some questions

regarding self-reported bilingual ability were also included on the Language Use,

Attitudes, and Vitality questionnaire that was administered to subjects in four

locations.

3.1 Sentence Repetition Testing

3.1.1 Procedures

A Sentence Repetition Test (SRT) consists of a set of fifteen carefully selected

sentences recorded on an audio-cassette. Each sentence is played once for each

subject and the subject is asked to repeat the sentence exactly the same way. Each

sentence is scored according to a four-point scale (03) for a maximum of 45 points

for 15 sentences. Each subject is evaluated on his ability to repeat each sentence

accurately. Any deviation from the recorded sentences is counted as an error. A

subjects ability to accurately repeat the sentences of increasing difficulty is directly

correlated with the ability to speak and understand the language: the higher the

score, the higher the bilingual proficiency.

The SRT results are expressed as a point total out of the maximum 45 points. They

are also expressed as an equivalent bilingual proficiency level or Reported Proficiency

Evaluation (RPE) level.5 The RPE levels range from 0+ (very minimal proficiency) to

4+ (approaching the proficiency level of a native speaker). Table 9 shows the RPE

levels equivalent to the Hindi SRT score ranges (Varenkamp 1991:9, Radloff

1991:242). It is generally believed that at a minimum, second language proficiency

5Two sentences had recording problems in two places. If the subjects missed or pronounced the words

in those sections incorrectly, they still received full credit.

-

26 3 Bilingualism

levels of approximately RPE level of 3+ or above are necessary for persons to

adequately understand and use complex written materials in a language other than

the mother tongue.

Table 9. Hindi SRT score ranges and corresponding RPE levels

Hindi SRT score RPE level Proficiency description 4445 4+ Near native speaker 3843 4 Excellent proficiency 3237 3+ Very good general proficiency 2632 3 Good, general proficiency 2025 2+ Good, basic proficiency 1419 2 Adequate, basic proficiency 0813 1+ Limited, basic proficiency 0407 1 Minimal, limited proficiency 0003 0+ Very minimal proficiency

The Hindi SRT was developed by Varenkamp (1991). Initial construction of an SRT is

time-consuming, but after it is developed, it is relatively quick and easy to administer

once test administrators are trained. It is also possible with SRT to analyse a large

sample in a relatively short time. When compared to RTT, SRT gives a more accurate

and complete evaluation of a communitys bilingual proficiency.

Since bilingual proficiency frequently correlates with independent variables such as

gender, age, and education, it is important to test an adequate sample in each

category. A sample of at least five people should be tested for each category of

demographic factors that is selected by the researchers. Appendix shows the Hindi

SRT sentences, along with the individual demographic details and scores of the test

subjects.

3.1.2 Demographic details of the area

In this survey, the Hindi SRT was administered in two villages of Madhya Pradesh,

among two mixed communities where Nimadi is spoken, namely Sonipura and Awlia

(Map 4). The researchers set gender, age, and education as the variables to

investigate in relation to Hindi bilingualism. While the overall population figures

were extracted from the 1991 Census of India, the adult population and education

figures were estimated based on the 1995 Voters List and interviews with village

leaders. In this survey, the researchers examined the variances between people who

had never been through any formal education (Uneducated), people who finished

their primary education (Primary-standards one through five), and people who

-

3.1 Sentence Repetition Testing 27

studied through higher education levels (Higher-standard six and above). The

researchers categorised subjects aged 17 to 34 years as Younger and aged 35 years

and above as Older.

Map 4. Questionnaire and Sentence Repetition Testing Sites

Sonipura

Sonipura is a large and prosperous village located seven kilometres north of the

district headquarters, Khargone. It is situated on the state highway towards Sanawad.

In this village, the majority of the people are from SC and other communities; few are

from STs. There is frequent transportation available by government and private

services every day. There is a school up to seventh standard in this village. Khargone

is the nearest town to go to for higher studies.

According to the village leader and the 1995 Voters List, the total population of

Sonipura is 1200. The following groups live in this village: Balai 90 houses, Patidar

80 houses, Muslims 30 houses, Chamar 15 houses, Dhankhar ten houses, Rathod

three houses, Kumar two houses, and Adivasi one house. The literacy percentages

were estimated by the village leader. Since the target subjects for SRT are adults

(above 17 years), the researchers considered the Voters List as a more appropriate

MAHARASHTRA

MADHYA PRADESH

KHARGONE

BARWANI

DHAR

Bhilkheda

* Sonipura

* Awlia

Jajamkhedi

INDORE

KHANDWA

Key State boundary

District boundary

District Headquarters

Questionnaire site

* Questionnaire/SRT site

-

28 3 Bilingualism

source for this information. According to the Voters List, the total number of adults in

Sonipura is 736, among which the males are 332 and females are 404. The

demographic information for Sonipura is summarised in Table 10.

Table 10. Demographic information for Sonipura

Total

population

Total

households

Literate Over 17 years

old

Male 540 --- 85% 332

Female 660 --- 25% 404

Total 1200 241 55% 736 The village leader estimated that 85 per cent (282) of the males are educated and 25

per cent (101) of the females are educated. At the time of this survey, the elders of

the community still had little interest in sending their female children to school.

Thirty per cent of the people aged 35 and above are reportedly educated; among

them the majority are males. The younger generation of Nimadi speakers is more

educated than the older generation.

Awlia

Awlia is a large village situated 30 kilometres west of Khandwa, the district

headquarters. This village contains a mixture of religions and castes. Hindus,

Christians, and Muslims live in this village. The castes are Bharud, Kachi, Kumbi

(OBC); Balai, Chamar (SC); and Bhilala, Bhil (ST).

All of the villagers are Nimadi speakers. Awlia is connected to the Khandwa-

Khargone state highway by a paved road. There is a mini-bus service from the village

to Khandwa.

According to the 1991 Census of India, the total population of Awlia is 3000. Seventy

per cent of the population are Hindus, 25 per cent are Christians and five per cent are

Muslims. Table 11 shows the demographic information available for Awlia village.

The literacy percentages were estimated by the village leader.

-

3.1 Sentence Repetition Testing 29

Table 11. Demographic information for Awlia

Total

population

Total

household

Literate Below 17 years

old

Over 17 years

old

Male 80% 589

Female 40% 576

Total 3000 264 67% 1835 1165 Awlia village has two primary schools (standards one through five) and one middle

school (standards six through eight). There are two hospitals, one general and one for

leprosy patients. Among the total population, approximately 2000 people reportedly

know how to read and write Hindi and 1000 do not. The researchers found it difficult

to find uneducated young subjects, either male or female, in this village.

3.1.3 Results and Analysis

Sonipura

A total of 48 subjects were tested in Sonipura. The researchers tried to get a sample

of five in each demographic category, but not all categories were well represented in

the village population. There were no older females who had studied higher than

primary levels. Most of the females in Sonipura are uneducated. Because girls go to

their husbands house after marriage, most of the parents think giving them an

education will be a waste of time and money. During or after primary school, the

majority of female children will drop out.

The SRT results here are summarised in Table 12. Avg is average of the individual

scores for that category, Lvl is the RPE level that is equivalent to the score, Sd is

standard deviation, and N is the number of subjects tested.

-

30 3 Bilingualism

Table 12. SRT results in Sonipura

Uneducated Primary Higher Total

Young Old Young Old Young Old

Male Avg Lvl Sd N

16 2 8 5

15 2 11 5

25 2+ 10 6

27 3 9 5

30 3 7 9

25 2+ 13 4

24 2+ 10 34

Female Avg Lvl Sd N

10 1+ 6 5

9 1+ 6 5

32 3+ 0 1

28 3 0 1

31 3 6 2

16 2 11 14

Total Avg Lvl Sd N

13 1+ 8 10

26 3 8 13

29 3 9 15

In these results, it is clear that, of the three variables investigated (gender, age, and

education), education in Hindi plays a noticeable role in the bilingual ability of the

people. Educated subjects showed more Hindi bilingual ability than uneducated

subjects. Males often show more bilingual ability than females. However, in Sonipura

this only occurred between uneducated males and females, and the difference was

only one-half RPE level (2 for males and 1+ for females). The researchers asked

many people to take the SRT, but few females actually completed the test; most of

them felt they would not be able to repeat the sentences. Because of this, it is likely

that the overall SRT scores for females in Sonipura would be even lower than the

results that appear in Table 12. Age did not have a notable influence on SRT results.

From Table 13, we can see that only 19 per cent of the subjects in Sonipura scored at

RPE level 3+ (good, general proficiency) or above, while the remaining 81 per cent

scored at RPE level 3 or below (from good, basic proficiency to as low as very

minimal proficiency). Although Sonipura is situated only seven kilometres from

district headquarters, thus giving more opportunity for contact with outsiders, the

Hindi proficiency level in this village is still relatively low.

-

3.1 Sentence Repetition Testing 31

Table 13. Tested levels of Hindi proficiency in Sonipura

SRT scores RPE level Predicted RPE levels No. of subjects % 4445 4+ Near native speaker 0 0% 3843 4 Excellent proficiency 1 2% 3237 3+ Very good, general proficiency 8 17% 2632 3 Good, general proficiency 12 25% 2025 2+ Good, basic proficiency 6 12% 1419 2 Adequate, basic proficiency 7 15% 0813 1+ Limited, basic proficiency 8 17% 0407 1 Minimal, limited proficiency 4 8% 0003 0+ Very minimal proficiency 2 4%

From these results, we can say that for Nimadi speakers in Sonipura, education is the

main factor that influences peoples bilingual ability in Hindi. These Hindi SRT results

indicate that a majority of Sonipura Nimadi speakers, especially the uneducated,

would be likely to benefit from a language development programme in their mother

tongue.

Awlia

A total of 52 subjects were tested on the Hindi SRT in Awlia. Of the 12 divisions in

the demographic profile, it proved possible to test a sample for each of the gender,

age, and education categories. The SRT results in Awlia are summarised in Table 14.

Table 14. SRT results in Awlia

Uneducated Primary Higher Total Young Old Young Old Young Old

Male Avg

Lvl

Sd

N

17 2 7 3

7 1 3 5

29 3 7 5

27 3 5 10

28 3 4 6

27 3 4 4

23 2+ 9 33

Female Avg

Lvl

Sd

N

13 2 6 2

13 2 9 6

23 2+ 0 1

17 2 11 4

30 3 4 4

23 2+ 7 2

19 2 10 19

Total Avg

Lvl

Sd

N

12 1+ 7 16

24 2+ 8 20

27 3 4 16

-

32 3 Bilingualism

There were no notable differences based on gender or age, but it is clear from these

results that education in Hindi has an influence on the performance of Awlia subjects

on the Hindi SRT. The more educated subjects performed better. The difference

between primary educated and higher educated subjects is only one-half RPE level,

but between uneducated and educated subjects there is a difference of one to one and

a half levels.

Table 15 shows that only 17 per cent of the Nimadi-speaking subjects in Awlia scored

at RPE level 3+ or above, with the other 83 per cent scoring at RPE level 3 or below.

Even though there have been three schools in this village for the last five decades, the

overall proficiency in Hindi is still relatively low.

Table 15. Tested levels of Hindi proficiency in Awlia

SRT scores RPE level Predicted RPE levels No. of subjects % 4445 4+ Near native speaker 0 0% 3843 4 Excellent proficiency 1 2% 3237 3+ Very good, general proficiency 8 15% 2632 3 Good, general proficiency 13 25% 2025 2+ Good, basic proficiency 13 25% 1419 2 Adequate, basic proficiency 4 8% 0813 1+ Limited, basic proficiency 8 15% 0407 1 Minimal, limited proficiency 3 6% 0003 0+ Very minimal proficiency 2 4% Among the Nimadi speakers tested in Awlia, some (those at RPE levels of 3+ or 4)

could probably understand and use complex written materials in Hindi, but the

majority probably could not. These results indicate that Nimadi speakers in Awlia

would also benefit from a language development programme in their mother tongue.

Sonipura and Awlia combined

The difference in the results from Sonipura and Awlia is relatively small. The key

observation is that although a few subjects were able to score at RPE level 3+ or

above on the Hindi SRT, the average scores among the subgroups of educated

subjects were still only equivalent to RPE level 3 overall. This indicates good, general

proficiency in Hindi, but is probably not adequate for understanding and using

complex written materials in Hindi.

-

3.2 Questionnaires and observation 33

3.2 Questionnaires and observation

To determine self-reported Hindi bilingual ability, bilingualism questions were

included on a Language Use, Attitudes, and Vitality (LUAV) questionnaire. Questions

were asked in Hindi, with mother tongue translation used for communication with

subjects who had limited Hindi ability. Subjects were asked, Can you speak Hindi?

Out of 54 subjects from four sites, 61 per cent (33 subjects) responded that they could

speak and understand Hindi. Thirty five per cent said they could not speak and

understand Hindi. The remaining four per cent said they could speak a little Hindi;

these three subjects were less educated and two were females. The 33 subjects who

reported that they speak Hindi said that they do so with outsiders, in the market, and

with government officials. Out of these, 54 per cent are younger and 46 per cent are

older; 65 per cent are male and 35 per cent are female; and 86 per cent are educated

and 14 per cent are uneducated. This shows that younger generation, the men, and

the educated reported that they are more bilingual in Hindi than the older

generation, the women, and the uneducated, respectively. Many of the subjects who

were surveyed have a fairly high self-perceived ability in Hindi. This probably

indicates that subjects can gain a basic understanding of Hindi in the situations where

they encounter it, but more complex details may not be understood.

Another way to assess bilingualism in Hindi is observation. The researchers observed

that many Nimadi speakers use a simplified variety of Hindi for market purposes and

basic communication with outsiders. However, the variety of Hindi used in Indian

television is perceived as standard Hindi, and televisions are becoming more common

in villages where Nimadi speakers live.

4 Language Use, Attitudes, and Vitality

A study of language use patterns attempts to describe which languages or speech

varieties members of a community use in different social situations. These situations,

called domains, are contexts in which the use of one language variety is considered

more appropriate than another (Fasold 1984:183).

A study of language attitudes generally attempts to describe peoples feelings and

preferences towards their own language and other speech varieties around them, and

-

34 4 Language Use, Attitudes, and Vitality

what value they place on those languages. Ultimately, these views, whether explicit

or unexpressed, will influence the results of efforts towards literacy and the

acceptability of literature development.

Language vitality is a key concept in sociolinguistic research. It refers to the overall

strength of a language, its perceived usefulness in a wide variety of situations, and its

likelihood of enduring through the coming generations. Many variables may

contribute to vitality, such as social status of the language, the number of speakers,

and whether it has a writing system.

4.1 Procedures

In this survey, orally administered questionnaires were the primary method for

assessing patterns of language use, language attitudes, and factors related to language

vitality. In addition to these questionnaires, observation and informal interviews were

also used. The questionnaires were asked in Hindi and/or in Nimadi. Because Hindi

was used, a potential bias was added to the study since Hindi is a prestige language.

The Language Use, Attitudes, and Vitality (LUAV) questionnaire is found in Appendix

, along with the demographic details and responses of the individual subjects.

A total of 54 subjects from four different villages (Map 5) responded to the LUAV

questionnaire. In order to get a broad overview, four sites from four districts were

selected. These villages include members of various caste groups. The overall sample

distribution is shown in Table 16. More than half of the subjects in the sample are

educated; most of the older subjects are uneducated.

Table 16. Sample distribution of LUAV subjects

Sex Age Uneducated Primary educated

(15)

Secondary educated (6+)

Male

36

Young (1735) 19

4 6 9

Old (35+) 17

7 5 5

Female

18

Young (1735) 9

5 2 2

Old (35+) 9

6 2 1

Total 54

22 15 17

-

4.2 Results 35

4.2 Results

4.2.1 Language use

Nimadi, or some variety thereof, is spoken as the mother tongue by all of the subjects

questioned. Approximately 61 per cent of the subjects who responded to the

questionnaires reported that they could speak or understand Hindi, while 35 per cent

of the subjects reported that they could not speak any other languages besides their

mother tongue. A very few said they could speak other languages such as English,

Bhilali, and Rathwi.

According to the questionnaire results as seen in Table 17, Nimadi is definitely the

language of choice in the home and with other villagers. Out of 54 subjects, virtually

all reported that they use Nimadi in their home and with villagers. Though different

language speakers come to the market, a majority (68 per cent) of the subjects also

reported using only Nimadi in the market. However, 20 per cent responded that they

speak Hindi as well as Nimadi. With government officials, Hindi is used on an equal

basis with Nimadi. Even with outsiders, Nimadi is being used by a majority (59 per

cent) of the subjects. Finally, for private prayer, 68 per cent of the subjects reported

using Nimadi, 25 per cent Hindi, and five per cent both languages; two per cent

reported using Sanskrit.

Table 17. Domains of language use among LUAV subjects

Domains Nimadi Hindi Both Sanskrit

In home with family members 100% 0% 0% 0%

Within the village with villagers 99% 1% 0% 0%

In the market 68% 12% 20% 0%

With government officials 44% 40% 16% 0%

With outsiders 59% 25% 16% 0%

In private prayer in temple/mosque/church 68% 25% 5% 2% For the most part, it appears that Nimadi is the language of choice in all domains

except for those situations where Nimadi speakers are in contact with non-Nimadi

speakers. Nimadi is the language of choice in the important domains of home/family,

village, and religion. With outsiders and government officials, the circumstances may

lead Nimadi speakers to learn and speak Hindi as well as Nimadi.

-

36 4 Language Use, Attitudes, and Vitality

In the analysis of responses according to gender, age, and education, Nimadi was

strongly used by the majority of all of the subjects. In domains other than home and

village, subjects with more education reported using Hindi or both Hindi and Nimadi.

With government officials, the older educated female subjects reported using only

Hindi. This was the only instance in which Hindi completely displaced Nimadi. The

younger uneducated subjects reported exclusive use of Nimadi with outsiders.

Table 18. Domains of language use according to gender, age, and education

a. At home

Sex Age Education NS Nimadi Hindi Both Other NA

Male Young

Uneducated 3 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 15 100% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Old Uneducated 7 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 12 100% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Female Young

Uneducated 5 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 4 100% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Old Uneducated 5 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 3 100% 0% 0% 0% 0%

b. In the village

Sex Age Education NS Nimadi Hindi Both Other NA

Male Young

Uneducated 3 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 15 100% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Old Uneducated 7 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 12 92% 0% 8% 0% 0%

Female Young

Uneducated 5 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 4 100% 0% 0% 0% 0%

Old Uneducated 5 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 3 100% 0% 0% 0% 0%

c. In the market

Sex Age Education NS Nimadi Hindi Both Other NA

Male Young

Uneducated 3 66% 0% 34% 0% 0% Educated 15 60% 20% 20% 0% 0%

Old Uneducated 7 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 12 62% 9% 25% 2% 2%

Female Young

Uneducated 5 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 4 50% 25% 25% 0% 0%

Old Uneducated 5 75% 5% 20% 0% 0% Educated 3 0% 66% 34% 0% 0%

-

4.2 Results 37

d. With government officials

Sex Age Education NS Nimadi Hindi Both Other NA

Male Young

Uneducated 3 67% 0% 33% 0% 0% Educated 15 28% 66% 0% 6% 0%

Old Uneducated 7 85% 0% 15% 0% 0% Educated 12 52% 28% 20% 0% 0%

Female Young

Uneducated 5 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 4 25% 50% 25% 0% 0%

Old Uneducated 5 80% 20% 0% 0% 0% Educated 3 0% 100% 0% 0% 0%

e. With outsiders

Sex Age Education NS Nimadi Hindi Both Other NA

Male Young

Uneducated 3 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 15 26% 46% 26% 0% 2%

Old Uneducated 7 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 12 34% 33% 25% 0% 8%

Female Young

Uneducated 5 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 4 25% 50% 0% 25% 0%

Old Uneducated 5 80% 20% 0% 0% 0% Educated 3 34% 33% 0% 33% 0%

f. In private prayer

Sex Age Education NS Nimadi Hindi Both Other NA

Male Young

Uneducated 3 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 15 54% 26% 14% 6% 0%

Old Uneducated 7 82% 16% 2% 0% 0% Educated 12 50% 33% 8% 0% 8%

Female Young

Uneducated 5 100% 0% 0% 0% 0% Educated 4 50% 25% 0% 25% 0%

Old Uneducated 5 80% 20% 0% 0% 0% Educated 3 34% 66% 0% 0% 0%

Informal interviews and observations provided insights into the use of Nimadi in the

educational domain. Hindi is the medium of instruction in the government schools.

The researchers observed that at the primary levels (standards one through five), if

the teacher was local she used primarily Nimadi to explain the lessons to the students

if they did not understand them in Hindi. In middle school (standards six through

eight), the students have a better grasp of Hindi, so more Hindi is used for

explanations. In high school, Hindi is used the majority of the time.

4.2.2 Language attitudes

Attitudes towards Nimadi varieties

Table 19 summarises responses to selected language attitude questions. The vast

majority of subjects expressed the opinion that young people speak Nimadi as well as

old people do, and that men speak Nimadi as purely as women do. This shows that

-

38 4 Language Use, Attitudes, and Vitality

although the younger generation has more exposure to Hindi (through education and

the media), they still reportedly speak Nimadi as well as the older generation. In the

same way, outside contact does not appear to affect the mens way of speaking

Nimadi. Nearly all (93 per cent) of the subjects answered that young people do feel

good about their mother tongue.

Table 19. Selected language attitudes among Nimadi LUAV subjects

Questions Yes Different NA No QNA Do young speak Nimadi as well as old? 51 1 1 0 0 Do men speak Nimadi as purely as women? 43 4 1 5 1

Table 20 summarises responses to the question, Where is pure Nimadi spoken (other

than your village)? Forty three per cent of the subjects replied that pure Nimadi is

found within the same district or in surrounding villages, while 39 per cent answered

that pure Nimadi is found in villages throughout the Nimad. These two responses

support the conclusion that many subjects have a positive attitude about Nimadi in

most other locations. However, most female subjects believed that the purest form

was the local variety, while a lower percentage of men believed so. This may be

because men generally have more opportunities to travel and talk with outsiders, so

are more likely to have been exposed to different varieties. However, women seldom

leave their own villages or have opportunities to interact with outsiders, so they are

less likely to be aware of other varieties. One person said Rajputs (a General Caste)

may speak good Nimadi and another person said that Backward Class (BC) people

might speak good Nimadi.

Table 20. Where is pure Nimadi spoken (other than your village)?

Sites and number of

subjects

Same district/

Surrounding villages

Villages/Nimad Dont

know

NA/Other

Awlia (15) 5 8 1 1 Bhilkheda (12) 5 4 2 1 Jajamkhedi (11) 4 3 3 1 Sonipura (16) 9 6 1 Total 23 (43%) 21 (39%) 6 (11%) 4 (7%)

Attitudes towards Nimadi compared with Hindi

In response to the questions, Hindi and Nimadi, which one do you like? Is Nimadi as

important as Hindi? 69 per cent of subjects said they like their mother tongue, 13

per cent said Hindi and nine per cent said both languages. A large majority of the

-

4.2 Results 39

subjects think Nimadi is as important as Hindi, while a few think that Nimadi is not

as important as Hindi. From these responses, it is clear that Nimadi speakers

interviewed on this survey have pride in their language and view it as important,

even in relation to Hindi.

Attitudes towards literacy and language development

Responses to the question, Are there any books, cassettes, radio or television

programmes in Nimadi? indicated that many subjects were aware of some materials

available in Nimadi. There was more awareness of audio materials and

radio/television programmes than of books. Those who do not know about these

materials are generally uneducated or do not have access to radios or televisions.

When subjects were asked, If there were a Nimadi medium school, would you send

your children? 69 per cent said they would, while 19 per cent said they would not.

This may be because some subjects thought the question meant that a school was

needed for learning Nimadi. However, the majority were open to the possibility of

mother tongue schools.

Responses to questions regarding interest in mother tongue reading materials and

literacy classes were strongly positive among both literate and illiterate subjects. This

shows that Nimadi subjects have a positive attitude towards the usage of their

existing literature and further development of Nimadi as a written form.

4.2.3 Language vitality

Several questions provide insights into Nimadi language vitality. Responses to these

questions are summarised and discussed in this section.

What language do your children learn first? Nearly all (89 per cent) of the subjects

said that children are learning Nimadi first. Two persons said their children should

learn Hindi first because Hindi influences most of the younger generation. Most of the

people reasoned that Nimadi is their mother tongue, and is spoken at home and in

the village, so learning another language first is not possible. What the parents speak,

that only the child will learn was their answer, and this supports the likely

maintenance of the language.

-

40 4 Language Use, Attitudes, and Vitality

Will you allow your son or daughter to marry someone who doesnt know Nimadi?

Almost half (48 per cent) of the subjects said no, while 28 per cent said yes. The

remaining subjects (24 per cent) gave other answers, such as if they are from the

same caste. These results indicate that some Nimadi speakers seem to have a broad

mind to accept speakers of other languages for marriage, on the condition that the

person is from the same community. However, chances are very low that non-Nimadi

speakers would be found within the same community. Overall, this pattern of

responses supports continued maintenance of the Nimadi language.

Do you think your grandchildren will speak Nimadi (after 100 years)? Seventy per

cent responded that Nimadi will be spoken by the coming generations, while 18 per

cent felt that they could not predict what might happen after 100 years. Only six per

cent said that there will be a shift to Hindi.

If Nimadi is not spoken by the next generation, will it be a good thing or a bad

thing? Although subjects report strong use of Nimadi in most domains at present,

responses to this question also indicate their openness to the possibility of future

generations shifting to Hindi; 54 per cent said it would be a good thing, 22 per cent

said it would be a bad thing, and nine per cent said they did not know. Subjects were

probably thinking of Hindi as the language that could displace Nimadi. They have a

high regard for Hindi and realise that Hindi offers opportunities for advancement.

As discussed in sections 4.2.1 and 4.2.2, subjects expressed the opinions that the

younger generation speaks Nimadi as well as the older generation, and that the

younger generation is proud of their mother tongue. Many subjects have a positive

attitude towards Nimadi and feel that it is as important as Hindi. In the key domains

of home, village, and religion, Nimadi language use is very strong among the subjects

interviewed. Overall, these responses indicate that Nimadi is likely to remain vital in

the foreseeable future.

Attitudes towards the use of Hindi are slightly positive, but use of Hindi is mainly

limited to instrumental functions; Hindi is seen as the language of education and

economic advancement. It seems unlikely that Nimadi speakers will give up their

mother tongue and completely shift to Hindi in coming generations.

-

5.1 Dialect area study 41

5 Summary of findings

5.1 Dialect area study

The Nimadi-speaking people are found in the south-western part of Madhya Pradesh.

Wordlist comparisons showed a relatively high degree of lexical similarity among the

Nimadi varieties studied in this survey. Lexical similarity percentages of these

varieties with Hindi, Gujarati, and Marathi were relatively lower. These results, taken

together with the perceptions of Nimadi speakers and the findings of other scholars,

indicate that Nimadi may be considered a distinct language.

The high RTT scores and positive post-RTT responses of all subjects (in six selected

locations) indicated that the subjects speak one and the same language and can

understand the tested Nimadi varieties well. Subjects from all six test locations

consistently scored well on both Nimadi stories. This suggests that Nimadi-speaking

people from locations across the Nimad region should be able to adequately

comprehend materials based on either of these varieties.

5.2 Bilingualism study

Based on self-reported bilingual ability, many subjects felt they can handle basic tasks

in Hindi. However, Hindi SRT results indicated that many Nimadi speakers, especially