The Nile treaty II - Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung - Auftrag ... · PDF fileThe Nile water treaties...

Transcript of The Nile treaty II - Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung - Auftrag ... · PDF fileThe Nile water treaties...

1

East Africa 9

By Arthur Okoth-Owiro

THE NILE TREATY

StateSuccession and

InternationalTreaty

Commitments:A Case Study ofThe Nile Water

Treaties

2

Published by: Konrad Adenauer Foundation Law and Policy Research Foundation27 Mbaruk Road Dhanjay ApartmentsGolf Course 9th Floor, Apt. 904Nairobi, Kenya Valley Arcade/Korosho Road

P. O. Box 20428Telephone: 254-(0)20-272595 NAIROBITelefax: 254-(0)20-2724902E-mail: [email protected] Telephone: 575197Internet: http://www.kas.de Telefax: 575198

Mobile: 0735-241550P. O. Box 66471Westlands 00800Nairobi, Kenya

ISSN 1681-5890

Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and Law and Policy Research Foundation do not necessarily subscribe to the opinion ofcontributors.

By Arthur Okoth-Owiro

Produced by Jacaranda Designs Limited - Post Office Box 76691, Nairobi, Kenya

© Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and Law and Policy Research Foundation 2004.

3

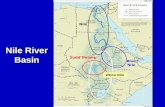

Source: World Bank

4

5

THE NILE TREATY

State Succession andInternational Treaty Commitments:

A Case Study of The Nile Water Treaties

BY ARTHUR OKOTH-OWIRO

Nairobi 2004

6

7

ContentsPart II. Introduction .............................................................................................. 1

II. The Nile: Hydrological, economic and legal aspects ................................. 2III. The Nile water treaties ............................................................................. 6III. State succession to treaties ...................................................................... 10V. Tthe legal status of the Nile water treaties .............................................. 13VI. Tthe Nile: In search of a legal regime .................................................... 21VII. The Nile questions: Implications for East Africa .................................... 28VII. Summary and conclusions ..................................................................... 34References ..................................................................................................... 35

Annex I. The position of the Nile basin countries onthe Nile water treaties .............................................................................. 37

Part II: The Nile treaties ............................................................................. 43Preamble ....................................................................................................... 44Factfile about the Nile river ........................................................................... 44Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Egypt .............................................. 49

v

8

9

declared that they are not bound by anysuch treaties.

On the other hand, competing principlesof international fluvial law has allowedlower riparian states, especially Egypt, toargue that the Nile water treaties arebinding in perpetuity. Water scarcity andthe national security of the Nile riparianstates now threaten to escalate tension overaccess to Nile waters into an open conflict,with Egypt threatening war should upperriparians divert the waters of the Nile. Aframework for the equitable distribution ofNile waters is urgently required.

The purpose of this paper is to explore thelegal position of successor states with regardto international treaty commitments. Acase study of the Nile Water Agreements isundertaken to clarify the rights and dutiesof states with regard to water treaties ingeneral and Nile waters in particular.

This study is considered useful because thestatus of the Nile as a shared water resource,and the emergence of new states on itsbasin, dictate that a legal regime to regulateaccess to its waters has to be negotiated inthe 21st Century. It is, therefore, necessaryto clarify the historical and contemporarysituation in order to prepare for the future.It may also be useful to remind riparianstates of their fundamental interests in theNile waters and treaty negotiations.

Ultimately, the views expressed in this paperare an East African view of the Nile question.

Many bilateral treaties were concludedbetween Egypt, Britain and other powersbetween 1885 and the Second World Warto regulate the utilisation of the waters ofthe River Nile. At that time, the entire NileBasin was under the sovereignty of foreign,mainly European powers. They committedthemselves to Egypt and Britain that theywould respect prior rights to, and especiallyclaims of “natural and historic” rights toNile waters, which Egypt asserted. A legalregime based on these treaties was thusestablished over the Nile.

Since the Second World War, most of theterritories on the Nile Basin have changedsovereignty with the majority acquiring fullstatehood as a result of de-colonization. Arethese successor states bound by treaties,which were purportedly concluded on theirbehalf by their predecessors? It is obviousthat the treaties can no longer reflect thepriorities and the strategic interests of these“new” states as they see them. In particular,access to the Nile waters is now regardedby these states as a sovereign right and aprerequisite for development.

Indeed, many of the upper-riparian statesinvoke the Harmon doctrine, which holdsthat a state has the right to do whatever itchooses with the waters that flow throughits boundaries, regardless of its effect on anyother riparian state. It has also beensuggested that the independence of the newstates was a fundamental change incircumstances that made the continuedvalidity of colonial-era treaties untenable.Some of the Nile basin countries have

I. INTRODUCTION

1

10

II. THE NILE: HYDROLOGICAL, ECONOMIC AND LEGALASPECTS

2.1 Hydrological FeaturesThe Nile, which is the only drainage outletfrom Lake Victoria, is one of the longest riversin the world. Its total length together withthose of its tributaries is about 3,030,300kilometres. The catchment area of the Niletotals some 2,900,000 square kilometres,representing about one-tenth of the surfacearea of the entire African Continent.

The Nile measures some 5,611 kilometresfrom its White Nile source in Lake Victoria(East Africa) and some 4,588 kilometresform the Blue Nile source in Lake Tsana(Ethiopia). Thus, the river system originatesfrom two distinct geographical zones.

One subsystem, with the White Nile as itsmain artery, originates in the equatoriallakes of East and Central Africa, the mostimportant of which is Lake Victoria, andin the Bahr-el-Ghazal water system — a vastlagoon formed by the convergence of anumber of streams rising to the East andNorth of the Nile-Congo divide.

The other subsystem consists of the BlueNile and its tributaries, the Atbara and theSobat. It originates from the EthiopianPlateau (Hurst, 1952; Waterbury, 1979;Godana, 1985).

The Nile is made up of three maintributaries. These are the White Nile, theBlue Nile and the Atbara. The White Nilerises from its source in the highlands ofRwanda and Burundi and flows into Lake

Victoria. It leaves Lake Victoria at itsnorthern shore near the Ugandan town ofJinja, through a swampy stretch aroundLake Kyoga in Central Uganda and thenheads north towards Lake Albert.

Lake Albert receives a good amount of waterfrom the Semliki River, which has its sourcein the Congo and empties first into LakeEdward, where it receives additional waterfrom tributaries coming from the RwenzoriMountains on its way to Lake Albert. FromLake Albert, the White Nile flows Northinto Southern Sudan (Kasimbaji, 1998).

Lake Victoria, Edward and Albert are thenatural reservoirs, which collect and storegreat quantities of water from the highrainfall regions of eastern Equatorial Africaand maintain a permanent flow down theWhite Nile with relatively small seasonalfluctuations (Beadle, 1974: 124).

In Southern Sudan, near the capital city ofKhartoum, the White Nile meets the BlueNile, which drains Lake Tsana in theEthiopian Highlands. The two flowtogether to just north of Khartoum wheresome 108 kilometres downstream, they arejoined by the Atbara, the last importantriver in the Nile system, whose source is inEritrea. The river then flows north throughLake Nasser and the Aswan Dam beforesplitting into major distributaries, theRosetta and Damietta, just north of Cairo.These distributaries flow into theMediterranean Sea (Okidi, 1982).

2

11

discharge, but at the lowflow it accounts for four-fifths of the total deltadischarge” (page 81).

Secondly, there is something infinitelymisleading about measuring the flow of theNile at Khartoum. It is estimated that some24 milliards of cubic metres of water flowdown the White Nile from Lake Albert andthe East African highlands, half of which islost through the intense evaporation andsoakage in the Sudd (Godana, 1985). Infact an official Sudanese Governmentpublication puts the total swamp losses at42 milliards of cubic metres (Sudan, 1975).

What should be measured is the amountof water leaving the lake plateau of EastAfrica, rather than what passes throughKhartoum. This is a more realistic estimateof the White Nile’s contribution. After all,Egypt and Sudan already have a treaty, the1959 Agreement, on how to apportion anyadditional Nile waters, and the JongleiCanal project is being undertaken toachieve the purpose of reducing the lossesof water in the Sudd, in order to increasethe amount reaching Khartoum.

Thirdly, estimating the flow of the Nile onthe basis of how much water reaches Sudanor Egypt appears to assume that the purposeof the Nile is to feed these two countrieswith water. On such an assumption, onlythe water reaching its destination is worthaccounting for! Surely, the waters of the Nileare important and useful for and in theentire basin – from Kagera to theMediterranean.

According to Godana (1985), the averageannual flow of the Nile is 84 milliards ofcubic metres as measured in Aswan. Ofthis total, Bard (1959) estimates that 84 percent is contributed by Ethiopia and only16 per cent comes from the Lake Plateauof Central Africa. A similar distributionpattern is given by Godana (1985: 82) whoasserts that 85 per cent of the flow of theNile originates from the Ethiopian plateau,whereas only 15 only comes from the EastAfrican source areas. It is, however,important to note that the statistics of theflow of the Nile are a complex matter, whichthe above estimates tend to over-simplify.

First, it must be remembered that the flowof the White Nile is relatively regularthroughout the year as opposed to the BlueNile - Atbara sub-system, which fluctuatesseasonally. At its peak discharge is July-September, Godana (1985: 81) reports thatthe Blue Nile swells to an enormoustorrential flow and accounts for some 90per cent of the waters passing throughKhartoum. By April, however, by April,the volume of water from these two sourcesdwindles to one-fortieth of the flooddischarge, to account for no more than 20per cent of the waters passing Khartoum.This calculation tallies with Garretson’s(1967) estimates that at the peak of its flood(April-September), the Blue Nile alonesupplies 90 per cent of the water passingthrough Khartoum, but in the low season(January-March) it provides only 20 percent. From this statistical informationGodana (1985) concludes:

“the White Nile atKhartoum provides only 40per cent of the river’s peak

3

12

apart from all other international rivers(Pompe, 1958).

Increasingly, all the basin states have cometo view the Nile as a principal feature oftheir economies. They show an increasinginterest in the abstraction and diversion ofNile water for various developmentpurposes, irrigation included. Examples ofsuch developments include the JongleiCanal Project in Sudan (which has beendormant due to the raging conflict since1983), and the planned construction, byEthiopia, of a new facility on the Blue Nileto supply irrigation water for 1.5 millionnewly resettled peasants in the westernprovince of Welega as well as to provide asteady source of hydroelectric power for thecountry (Kukk and Deese, 1996:44).

Godana (1985) also reports that Tanzaniahopes to implement a plan to abstract thewaters of Lake Victoria to irrigate therelatively low and dry steppes of CentralTanzania. And with the establishment ofthe Lake Basin Development Authorityin Kenya, the country has began to treatthe resources of the Lake Victoria basinmore comprehensively.

The economic importance of the Nile isalso reflected in the establishment of varioussub-basin initiatives for the developmentand management of basin resources. Theseinclude the Kagera Basin Organisation, theTechnical Cooperation for the Promotionof the Development and EnvironmentalProtection of the Nile Basin(TECCONILE) and the Lake VictoriaEnvironment Management Programme(LVEMP) (Kazimbazi, 1998).

2.2 Economic AspectsIn general, the waters of the Nile are utilisedfor irrigation, hydro-electric powerproduction, water supply, fishing, tourism,flood control, water transportation and theprotection of public health (Kazimbazi,1998). In particular, it should be noted thatthe economy of the entire Nile Basin almostentirely consists in the agricultural activitiesof the co-riparians of the Nile - Rwanda,Burundi, Congo, Tanganyika, Kenya,Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea and Egypt.

In the upper-basin states of Ethiopia,Eritrea, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania,Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwandaand Burundi, settled agriculture is thegeneral economic activity. The lower-basinstates of Sudan and Egypt are also primarilyagricultural economies but, in contrast withthe upper-basin states, their agriculture islargely irrigation-based. The economic useof the Nile for purposes of agriculture(particularly irrigation-based agriculture) is,therefore, its most important use.

In Egypt, a desert agricultural country, theentire life of the nation is dependent on theriver’s waters. As President Anwar Sadatstated in 1978,

“We depend upon the Nile100 per cent in our life, so ifanyone, at any moment,thinks of depriving us of ourlife we shall never hesitateto go to war” (Kukk andDeese, 1996:46).

The complete control of the river over theeconomy of Egypt has been characterisedas the unique feature of the Nile, setting it

4

13

2.3 The Legal AspectsThe Nile is an international river. As ashared water resource, the development,utilisation and management of the Nilebasin waters is regulated by internationalwater resources law. Following thenomenclature of Article 38 of the Statuteof the International Court of Justice,international water resources law may bederived from:

a) International conventions, whethergeneral or particular;

b) International customs;c) The general principles of law

recognised by civilized nations; andd) As a subsidiary means, the judicial

decisions and the teachings of themost highly qualified publicists ofthe various nations.

The conclusion of international treaties orconventions has been the most importantmethod of international law-making, hencethe primary means for the establishmentof international rights and obligations overshared water resources. Most authoritieswould hold that an international treaty orconvention is needed to ensure the mostreasonable utilisation of international water

courses (Bruhacs, 1993:59). There is nosuch international treaty applicable to theNile, and even the United NationsConvention on the Law of the Non-Navigational uses of Internationalwatercourses of 1997 (36 I.L.M. 700),which is sure to change the regime ofinternational water law, has not entered intoforce.

Besides, although “nearly all thecommentators on the problems of the fulldevelopment of the Nile basin haveconcluded their various analyses with asuggestion in one form or another of theneed for a Nile River Basin Authority orAdministration” (Garretson, 1960:144),such a basin-wide institution has nevermaterialised.

The legal regime for the utilisation andmanagement of the Nile, therefore, consistsof bilateral treaties concluded amongst theriparian states, and the internationalcustomary law. It has been suggested thatthese bilateral treaties reflect customary lawprinciples (Fahmi, 1986) — a position thathas been vigorously contested (Batstone,1959; Pompe, 1958).

5

14

III. THE NILE WATER TREATIES

The purpose of this section is to describeand analyse the treaties and legalinstruments, which fall into the first threecategories. These are the legal instrumentswhose devolution or inheritance is thesubject matter of this paper.

3.1 Treaties between U.K andthe powers controlling the NileBasinBetween 1891 and 1925, the UnitedKingdom of Great Britain entered into fiveagreements on the utilisation of the watersof the Nile.

On April 15, 1891, the United Kingdomand Italy signed a protocol for thedemarcation of their respective spheres ofinfluence in Eastern Africa. Article III ofthis Protocol sought to protect the Egyptianinterest in the Nile waters contributed bythe Atbara River, the upper reaches of whichfell within the newly acquired Italianpossession of Eritrea. The Article providedas follows:

“The Government of Italyundertakes not toconstruct on the Atbaraany irrigation or otherworks which might sensiblymodify its flow into theNile”.

On May 15, 1902, the United Kingdomof Great Britain and Ethiopia, the formeracting for Egypt and the Anglo-EgyptianSudan, signed at Addis Ababa, a Treatyregarding the Frontiers between the Anglo-

The Nile water treaties have been thesubject of many studies and comments,most notably by Batstone (1959),Garretson (1960), Teclaff (1967), Okidi(1982 and 1994), Godana (1985) andCarrol (1999).

As Godana (1985) observes, with theestablishment of European colonial ruleover most of the Nile basin in the closingdecades of the 19th Century, it becamenecessary to regulate, through treaties andother instruments, the water rights andobligations attaching to the various colonialterritories within the basin.

In this manner, the colonial period cameto witness a steady development of formaltreaties and regulations as well as ofinformal working arrangements andadministrative measures which, takentogether, constituted the legal regime of theNile drainage system.

The treaties and legal instrumentsregulating the use of Nile waters may bedivided into four categories. These are:-

(i) Treaties between the UnitedKingdom and the powers in controlof the upper reaches of the Nilebasin around the beginning of the20th Century;

(ii) The 1929 Nile Waters Agreement;(iii) Agreements and measures

supplementing and consolidatingthe 1929 Agreement; and

(iv) Post-colonial treaties and otherlegal instruments.

6

15

Egyptian Sudan, Ethiopia and BritishEritrea. Article III of the Treaty wasconcerned, not with boundaries, but withthe Nile waters originating in Ethiopia.It provided:

“His Majesty the EmperorMenelik II, King of kings ofEthiopia, engages himselftowards the Governmentof His Britannic Majesty notto construct or allow to beconstructed, any worksacross the Blue Nile, LakeTsana or the Sobat, whichwould arrest the flow oftheir waters into the Nileexcept in agreement withhis Britannic Majesty’sGovernment and theGovernment of theSudan”.

On May 9, 1906, the United Kingdomand the Independent State of the Congoconcluded a Treaty to Re-define TheirRespective Spheres of Influence inEastern and Central Africa. Article IIIof the Treaty provided:

“The Government of theIndependent State ofCongo undertakes not toconstruct or allow to beconstructed any work overor near the Semliki orIsango Rivers, which woulddiminish the volume ofwater entering Lake Albert,except in agreement withthe SudaneseGovernment”.

On April 3, 1906, the United Kingdom,France and Italy signed a tripartite

agreement and set of declarations inLondon. Article IV(a) provided that:

“in order to preserve theintegrity of Ethiopia andprovide further that theparties would safeguardthe interests of the UnitedKingdom and Egypt in theNile basin, especially asregards the regulation ofthe water of that river andits tributaries …”.

Finally, in December 1925, there was anexchange of Notes between Italy and theUnited Kingdom by which Italy recognisedthe prior hydraulic rights of Egypt and theSudan in the headwaters of the Blue Nileand White Nile rivers and their tributariesand engaged not to construct on the headwaters any work which might sensiblymodify their flow into the main river.

Garretson (1960) and Godana (1985)observe that regardless of whether theabove agreements were concluded byBritain with another European powerseeking to establish a sphere of influence,or with an African state such as Ethiopia,they had the common objective ofsecuring recognition of the principle thatno upper-basin state had the right tointerfere with the flow of the Nile, inparticular to the detriment of Egypt.

3.2 The 1929 Nile WatersAgreement.The Exchange of Notes between GreatBritain (acting for Sudan and her EastAfrican dependencies) and Egypt inregard to the use of the waters of the Nile

7

16

any works on the river and itsbranches, or to take any measurewith a view to increasing thewater supply for the benefit ofEgypt, they will agree beforehandwith the local authorities on themeasures to be taken to safeguardlocal interests. The construction,maintenance and administrationof the above mentioned worksshall be under the direct controlof the Egyptian Government.

The Agreement also expressed recognitionby Great Britain, of Egypt’s “natural andhistoric rights in the waters of the Nile”,even though the precise content of theserights was not elaborated.

The 1929 Nile Waters Agreement has beeninvoked by those who regard it as apraiseworthy recognition of the water rightsof Egypt (Smith, 1931). To some Egyptianwriters, it has merely recorded Egypt’sestablished rights over the Nile sinceantiquity (Khadduri, 1972). But theoverwhelming weight of expert opinionappears to favour the view that the “The1929 settlement of the Nile waters was apolitical matter and that it cannot be usedas a precedent in internationallaw““(Berber, 1959:96)”.

3.3 Agreements Consolidatingand Supplementing the 1929AgreementThe most important agreements falling intothis category are the supplementaryAgreement of 1932 (the Aswan DamProject) and the Owen Falls Agreement.Given the effect of the 1959 Agreement forthe full utilisation of the Nile Waters

for irrigation purposes (“The 1929 NileWaters Agreement”) is the mostcontroversial of all the Nile Wateragreements. It is also the most important.According to Batstone (1959), it is thedominating feature of legal relationshipsconcerning the distribution andutilisation of the Nile waters today.Godana (1985) adds that theagreement”“has become the basis of allsubsequent water allocations (but) hasbeen viewed differently by variouswriters” (page 176).

The purpose of the 1929 Nile Watersagreement was to guarantee and facilitatean increase in the volume of water reachingEgypt. The Agreement was based on theoutcome of political negotiations betweenEgypt and Great Britain in 1920s, and inparticular on the report of the 1925 NileWaters Commission, which was attachedto the agreement as an integral part thereof.

The Agreement provided as follows:(i) Save with the previous agreement

of the Egyptian Government, noirrigation or power works, ormeasures are to be constructed ortaken on the River Nile or itsbranches, or on the lakes fromwhich it flows in the Sudan or incountries under Britishadministration, which would, insuch a manner as to entail prejudiceto the interests of Egypt, eitherreduce the quantities of waterarriving in Egypt or modify thedate of its arrival, or lower its level.

(ii) In case the Egyptian Governmentdecides to construct in the Sudan

8

17

Uganda Electricity Board,the latter will regulate thedischarges to be passedthrough the dam on theinstructions of the EgyptianGovernment for thispurpose in accordancewith arrangements to beagreed upon between theEgyptian Ministry of PublicWorks and the a pursuantto the provisions ofagreement to beconcluded between thetwo Governments.”

The Agreement also provided that theUgandan Government could take anyaction it considered desirable before or afterthe construction of the dam, provided thatit did so after consultation and with theconsent of the Egyptian Government, andprovided further that:

“— this action does notentail any prejudice to theinterests of Egypt inaccordance with the NileWaters Agreement of 1929and does not adverselyaffect the discharge ofwater to be passedthrough the dam inaccordance with thearrangements to beagreed between the twoGovernments —.”

In other words, the Egyptian interests inthe flow of the Nile waters, as defined inthe 1929 Nile Agreement, remainedpredominant, and Uganda’s sovereign rightto deal with its dam was made subject tothe established and future Egyptian rightsand interests. The Owen falls Dam wascompleted in 1954.

between Egypt and Sudan, only the OwenFalls Agreement merits analysis here.

The last colonial-era treaty regulation of theNile River System was the 1952 Agreementconcluded by Exchange of Notes betweenEgypt and the United Kingdom (acting forUganda) concerning the construction of theOwen Falls Dam in Uganda, then underBritish colonial administration. Thepurpose of the Agreement was two-fold:

(a) the control of the Nile Waters, and(b) the production of hydroelectric

power for Uganda.

The most important point of thesubstantive legal regime created by OwenFalls Dam Agreement was the regulationof the Nile River flow. The Agreementprovided as follows:

“The two governmentshave also agreed thatthough the construction ofthe dam will be theresponsibility of theUganda Electricity Board,the interests of Egypt will,during the period ofconstruction, berepresented at the site bythe Egyptian residentengineer of suitable rankand his staff stationedthere by the RoyalEgyptian Government towhom all facilities will begiven for theaccomplishment of theirduties. Furthermore, thetwo governments haveagreed that although thedam when constructed willbe administered andmaintained by the

9

18

The purpose of this section is to outlinethe law on state succession and how thislaw affects treaties, with particular emphasison water treaties.

3.1 State SuccessionState succession arises when there is adefinitive replacement of one state byanother in respect of sovereignty over agiven territory in conformity withinternational law (Brownlie, 1990:654). Inother words, state succession consists of anychange of sovereignty over a given territorywhose effect is recognised in internationallaw. It includes both “Succession in fact”and”“Succession in law”.

Succession in fact refers to the factualsituation in which, through some politicalevolution, a territory that previously wasplaced under the sovereignty of one statecomes to fall under that of another statei.e. to the transfer of territory from one stateto another.

Such a transfer may occur when theterritory of one state is annexed, in wholeor in part; by another state, when one statecedes part of its territory to another; whentwo or more states merge to form a singlestate; when part of a national communitysecedes from a state, or combines withanother existing state; or when a territorialcommunity which was under colonial ruleachieves independence by a process ofrevolution or constitutional evolution.

The common feature of all these forms offactual succession is that one state ceases to

be real in a territory and another takesits place.

Succession in law refers to the successionof the new sovereign to legal rights andobligations of the old sovereign, or moregenerally, to pre-existing legal situations.Thus, succession in law is a legalconsequence of succession in fact. We arehere concerned with the obligations of theprevious sovereign to its territorial successor.

State succession is an area of greatuncertainty and controversy. This is duepartly to the fact that much of the statepractice is equivocal and could be explainedon the basis of special agreement andvarious rules distinct from the category ofstate succession. Not many settled legalrules have emerged as yet (Brownlie, 1990).

In other words, it is not clear, from eitherwritings on international law or the practiceof states, how and to what extent a legalprinciple of state succession applies in thesense of the transmissibility of rights andobligations from one state to another. Forstate succession in fact does not entail anautomatic juridical substitution of thefactual successor state in the complex sumof rights and obligations of the predecessorstate (Godana, 1985:134).

3.2 State Succession in the NileBasinThe Nile Basin has witnessed severalchanges in territorial sovereignty over theyears. Just as European occupation andcolonisation was the most important

III. STATE SUCCESSION TO TREATIES

10

19

treaties of the predecessor sovereign byvirtue of a principle of state succession.

As a matter of general principle a new state,ex-hypothesi a non-party, cannot be boundby a treaty, and in addition other parties toa treaty are not bound to accept a new party,as it were, by operation of law (Brownlie,1990:668). The rule of non-transmissibilityapplies both to secession of newlyindependent states (that is, to cases ofdecolonisation) and to other appearancesof new states by the union or dissolutionof states.

To the general rule of non-transmissibility(the “clean state” doctrine) there are someexceptions. The clear examples are:

i) law-making treaties or treatiesevidencing rules of generalinternational law,

ii) boundary treaties.

It is held by some writers that a thirdcategory of treaties, which they call“dispositive,””“localized” or “real,” are alsoan exception to the general rule of non-transmissibility (O’Connel, 1956; McNair,1938). Proponents of the doctrine ofdispositive treaties divide all treaties intotwo main categories, viz, personal treatiesand impersonal or dispositive treaties.Personal treaties are those dealing withpolitical, administrative or economicrelations; they are, therefore, basicallycontractual in character in that they arepersonal to the parties. A personal treaty issaid to be fundamentally a contract and,therefore, dependent on the continuedexistence of the parties. If any of the partiesto such a treaty disappears in relation to a

influence in state-formation in the region,decolonisation has been the most importantcause of state succession. All the ten NileBasin countries, except Egypt and Ethiopia,were dependencies of various Europeanpowers and became independent states inthe second- half of the 20th Century. Andaside from decolonisation, state successionin the Nile basin has been prompted bysuch diverse factors as conquest,annexation, merger and secession. A fewexamples will suffice.

Egypt has been part of the OttomanEmpire, under Turkish Suzerainty; aprotectorate of Great Britain, anindependent state and finally in 1958, partof the United Arab Republic after unitingwith Syria. Ethiopia, a sovereign state, wasconquered by Italy in 1936, a change ofsovereignty that was recognised byEuropean powers. Eritrea was a colony ofItaly, became a part of Ethiopia and is nowan independent state, after a war ofsecession. And Tanganyika, Rwanda andBurundi were colonised by Germany andthen became mandated territories,respectively under Britain and Belgium,before gaining independence to becomesovereign states. In 1964, Tanganyikamerged with Zanzibar to form Tanzania.All the 10 riparian states on the Nile aresuccessor states.

3.3 Succession to TreatiesThe effect of change of sovereignty ontreaties is not a manifestation of somegeneral principles or rule of state succession,but rather a matter of treaty law andinterpretation (O’Connell, 1956). When anew state emerges it is not bound by the

11

20

insufficient evidence ineither principle or practicefor the existence of thisexception to the generalrule. First, much of thepractice is equivocal andmay rest onacquiescence. Secondly,the category is verydifficult to define and it isnot clear why treatiesapparently includedshould be treated in aspecial way. Supporters ofthe alleged exceptionlean on materials, whichare commonly cited asevidence of anindependent concept ofstate servitude “(Brownlie1990:669)”

3.4 The PracticeIn practice problems of succession are dealtwith by devolution (or inheritance)agreements, by original accession toconventions by new states and by unilateraldeclarations. (Brownlie, 1990:671).

On a considerable number of occasions theinheritance or devolution of treaty rightsand obligations has been the subject ofagreements between the predecessor andsuccessor states. Such agreements promotecertainty and stability of relations. InAfrica, Great Britain concluded inheritanceagreement with Ghana, Nigeria, SierraLeone and the Gambia (Mutiti, 1976:33-39). It is, therefore, reasonable to conclude/infer that Great Britain did not want treatyrights and obligations over the Nile todevolve. Otherwise, she would haveconcluded inheritance treaties with herformer dependencies.

part of its territory, it ceases to be able tofulfil the obligations undertaken as asovereign power over that territory.

Dispositive treaties, on the other hand, arethose which create “real” rights andobligations i.e. rights and obligations in remin territory. As such, dispositive treaties areimmune to the change of sovereignty andrem with the land like the easement ofEnglish Common law or the servitudes ofRoman law. Examples of such treaties aresaid to include river treaties, boundarytreaties and treaties of peace and neutrality.

The idea of dispositive treaties isunconvincing. Lester (1963) discusses itat length and finds first, that it isimpossible to define the differencebetween localised and non-localisedtreaties, and second, that British statepractice does not appear to recognise aspecial category of localised (dispositive)treaties for purposes of state succession.

In his opinion, both in theory andaccording to British and Commonwealthpractice, localised treaties are no exceptionto the general rule that bilateral treaties donot devolve upon successor states, and thisopinion accords with the position ininternational law. Where rights in rem arerecognised by new states, recognition isexplained otherwise than an account of theautomatic descent of treaties.

A similar conclusion is reached by Brownlie(1990) when he says;

“The present writer, incompany with others,considers that there is

12

21

V. THE LEGAL STATUS OF THE NILE WATER TREATIES

on behalf of Kenya, Tanganyika andUganda (Lester, 1963:501). And August27, 1959, the United Kingdom made thefollowing statement.

“—the territories of BritishEast Africa will need fortheir development morewater than they at presentuse and will wish theirclaims for more water tobe recognised by otherstates concerned.Moreover, they will find itdifficult to press aheadwith their owndevelopment until theyknow what new worksdownstream states willrequire on the headwaterswithin British East AfricanTerritory. For this reason theUnited KingdomGovernment wouldwelcome an earlysettlement of the wholeNile waters question”.(Garrestson, 1960:143).

It is also a significant fact that as soon asthe dependent territories becameindependent, they refused to accept thevalidity of the Nile Water Treaties. Thus,after attaining independence in 1956,Sudan denied the continued validity ofthe 1929 Nile Water Agreement. In fact,Egypt was compelled to negotiate a newtreaty with its southern neighbour, the1959 agreement on the full utilisation ofthe Nile Waters.

When it became independent in 1960,Tanganyika refused to be bound by treaties

What is the legal status of the Nile watertreaties described above – or morespecifically, is the international legal regimeestablished over the Nile through treatiesconcluded between Great Britain and Egyptwith other powers still operational andbinding on Nile basin states? The answerto this question is fundamental to the issueof rights and obligations over Nile waters.

If the Nile Waters Treaties are valid andbinding, they legitimise the legal order ofthe colonial period that gave Egypt pre-eminence in the control of the Nile anddevelopments in the basin. This would bea severe constraint on the developmentefforts and opportunities of upper riparianstates. But if the Nile Waters treaties arenot binding, then the control andutilisation of Nile waters are regulated bythe principles of customary internationalwater law. It would also mean that the Nileis in search of a new legal regime in theform of a basin-wide agreement. This wouldprovide plenty of room for negotiation andbargaining as amongst the riparian states.It could help develop a utilisation regimethat is more sustainable and equitable.

5.1 The Problem in PerspectiveThe legal status of the Nile Water treatieshas been a contentious issue since the1950s. On May 18, 1956, in a statementattributed to the Joint Undersecretary forForeign Affairs, it was stated that the BritishGovernment regarded the 1929 agreementand other treaties creating a regime over theNile waters as subject to revision, and thatit was intended to negotiate new terms

13

22

identical notes to the Governments ofBritain, Egypt and Sudan outlining thepolicy of Tanganyika on the use of thewaters of the Nile. The note read as follows:

“The Government ofTanganyika, conscious ofthe vital importance ofLake Victoria and itscatchment area to thefuture needs and interestsof the people ofTanganyika, has given themost serious considerationto the situation that arisesfrom the emergence ofTanganyika as anindependent sovereignstate in relation to theprovisions of the NileWaters Agreements on theuse of the waters of theNile entered into in 1929 bymeans of an exchange ofNotes between theGovernments of Egypt andthe United Kingdom.

As the result of suchconsiderations, theGovernment ofTanganyika has come tothe conclusion that theprovisions of the 1929Agreement purporting toapply to the countriesunder British Administrationare not binding onTanganyika. At the sametime, however, andrecognising theimportance of the watersof the Nile that have theirsource in Lake Victoria tothe governments andpeople of all riparianstates, the Government ofTanganyika is willing toenter into discussions withother interested

concluded by Great Britain on her behalf,and in particular, objected to the 1929 NileWaters Agreement. In 1961 theGovernment of Tanganyika made adeclaration to the Secretary-General of theUnited Nations in the following terms:

‘As regards bilateraltreaties validly concludedby the United Kingdom onbehalf of the territory ofTanganyika, or validlyapplied or extended bythe former to the territoryof the latter, theGovernment ofTanganyika is willing tocontinue to apply within itsterritory on a basis ofreciprocity, the terms of allsuch treaties for a periodof two years from the dateof independence— unlessabrogated or modifiedearlier by mutual consent.At the expiry of thatperiod, the Government ofTanganyika will regardsuch of these treatieswhich could not by theapplication of rules ofcustomary internationallaw be regarded asotherwise surviving, ashaving terminated.’(Seaton and Maliti, 1973;Brownlie, 1990).

Tanganyika’s approach was adopted byother countries including Kenya, Uganda,Burundi and Rwanda, who all refused tobe bound by treaties concluded by colonialpowers (Okidi, 1982).

In the matter of the 1929 Nile WatersAgreement, the Government ofTanganyika, on July 4, 1962, addressed

14

23

This pressure is compounded by the factthat most of the Nile Basin states have onlyrecently started making systematic andappreciable (usually very unilateral)demands on the waters of the Nile and itseffluents, as they embark on post-colonialprogrammes of development.

It is, therefore, not surprising that the statusof the Nile treaties keep being raised as anissue in the fora in which resource rightsand water are being discussed. In Kenya inrecent times, there have been no less thanfour appeals to address the Nile watersquestion. Thus, speaking to journalists onFebruary 12, 2002, Energy Minister RailaOdinga said that the 1929 Agreementshould be renegotiated. Continued he;

“The three countries(Kenya, Uganda andTanzania) were notindependent and wereunder colonial rule. That iswhat makes the treatyunfair. Why should we bedenied the use of ourwater in the name ofconserving it for othersdownstream?” (DailyNation, 13th Feb, 2002,page 5).

And speaking at a water conference inNairobi on 21st March 21, 2002, aprominent international lawyer, Prof.Charles Odidi Okidi declared that the1929 Agreement was not binding andshould not be honoured by Kenya andother East African countries (page 4,Daily Nation March 22, 2002) Mbaria(2002) and Kamau (2002) have madesimilar statements.

governments at theappropriate time, with aview to formulating andagreeing on measures forthe regulation and divisionof the waters in a mannerthat is just and equitable toall riparian states and thegreatest benefit to all theirpeoples” (Seaton andMaliti, ‘973).

Another source of pressure on the legalstatus of the Nile Water Treaties is waterstress and water scarcity in the Nile Basin.Hydrologists define countries whose annualwater supply averages between 1,000 and2,000 cubic meters per person as waterstressed (the category before water scarce).A country is determined to be water scarcewhen its annual supply of internalrenewable water falls below 1,000 cubicwaters per person (2,740 litres per day). Insocio-economic terms, scarcity occurs whenthe lack of water endangers foodproduction, constrains economicdevelopment and jeopardises a country’snatural systems (Gleick, 1993).

Due to a combination of factors, includingpopulation growth, consumption practicesand patterns, diversionary activities of waterresources and climatic and environmentalconditions, the Nile basin countries arebeginning to experience water scarcity, withfour of them (Egypt, Kenya, Rwanda andBurundi) already classified as water-scarcestates. (Kukk and Deese, 1996). Access tothe waters of the Nile is becoming a securitymatter, and the matter of rights andobligations is at the centre of things.

15

24

And from statements attributed to herpolitical leaders, Egypt clearly regards accessto the waters of the Nile as a nationalsecurity matter. Egypt has repeatedly statedthat if Ethiopia or any other upstreamcountry diverts the Nile, she would useforce to rectify the situation (Myers, 1989;Starr, 1991).

(iii) The Writings of PublicistsSome writers have expressed the view,based on the controversial idea ofdispositive treaties, that the Nile Waterstreaties were either declaratory ofprescriptive rights or territorial incharacter and, therefore, transmissible.

Thus Vali (1958) describes the 1929 NileWaters Agreement as an agreement whoseterritorial character necessitates its respectby successor states (Lester, 1963:500).And Godana (1985) proceeds on theassumption that the 1929 agreement isbinding. He declares:

“— Of all the earlyinstruments on theutilisation of the NileWaters, only the 1929agreement, asimplemented by a numberof subsequent agreementsand measures, seems tosurvive. The survival of thisparticular treaty isunmistakably attested toby available evidence”(page 156).

But the “available evidence” is difficult toisolate, given that elsewhere, Godana(1985) opines as follows:

The status of the Nile Water treaties hasalso been raised in the East Africanlegislative Assembly by Yona Kanyomozi ofUganda (Kamau, 2002).

5.2 The Claim that the NileWater Treaties are valid andbindingThe claim (and assertion) that the NileWater treaties are valid and binding onsuccessor states is based on, or encouragedby three sets of factors. These are theattitude of Egypt towards the treaties, thewritings of certain publicists and theambivalent position expressed by someriparian countries.

(i) Egypt’s PositionEgypt holds the view that all the Nile Riveragreements are by their nature perpetuallybinding on successor states. In herestimation, these instruments aretransmitted to the successor states and maybe either amended or abrogated only byconsent in accordance with the ViennaConvention on the Law of Treaties. Egyptfurther asserts that treaties concluded byEuropean powers acting on behalf ofcolonised African states continue to be inforce by virtue of the law of state successionand because of the territorial nature of theobligations resulting from these treaties(Godana 1985).

Egypt also holds the view that she has“natural and historic” rights over Nilewaters acquired by long usage andrecognised by other states like Great Britainand Sudan, and that the Nile Water treatieshave been declaratory of internationalcustomary law relating to fluvial law.

16

25

two years within which to re-negotiatetreaties entered into on her behalf by theUnited Kingdom. By a communication tothe Secretary-General of the UnitedNations dated March 25, 1964, the PrimeMinister of Kenya made the followingdeclaration on the subject of succession oftreaties extended or applied to Kenya bythe Government of the United Kingdomprior to independence:

“In so far as bilateraltreaties concluded orextended by formerKingdom on behalf of theterritory of Kenya or validlyapplied or extended bythe former to the territoryof the latter areconcerned, theGovernment of Kenya iswilling to be a successor tothem subject to thefollowing conditions:

a)That such treaties shallcontinue in force for aperiod of two years fromthe date of Independence(i.e. until December 12,1965)

b)That such treaties shall beapplied on a basis orreciprocity.

c)That such treaties may beabrogated or modified bymutual consent of theother contracting partybefore December 12,1965.

At the expiry of theaforementioned period oftwo years, theGovernment of Kenya willconsider these treaties,which cannot beregarded as survivingaccording to the rules of

“It seems doubtful that the1929 agreement wasseriously regarded or evenintended as permanent inthe sense that it wouldbind all successor states inperpetuity” (page 143).

Be that as it may, such opinions expressedby learned publicists create the impression,and encourage the interpretation that theNile Water agreements are binding andvalid, either because of their territorialcharacter, or because it was the intentionof the high contracting parties that the newsovereign states would be automaticallybound by such treaties.

(iii) The Uncertain Position of SomeRiparian StatesSome Nile Riparian Countries have spokenstrongly and consistently on the Nile WaterTreaties, making it clear that they are notbound, and the treaties are not valid. Thesecountries include Tanzania, Ethiopia,Sudan (on the 1929 Agreement) andBurundi. But there are states on the Nilebasin whose positions have been ratherambiguous. A good example of such a stateis Kenya.

Even before independence, it was reportedthat “the local legislative councils of theterritories (of East Africa, Kenya included)have indicated their dissatisfaction at whatthey consider to be the United Kingdom’sinadequate international expression of theirinterests as upper riparians” as regards theNile Water treaties (Garretson, 1960:144).

Then at independence, Kenya adopted theNyerere doctrine and declared her intentionnot to be bound, giving a grace period of

17

26

Nile Water Treaty and the Owen FallsAgreement. Godana (1985) takes the viewthat the 1929 Agreement has “survived”.O’Connell (1967) and others would takethe view that such treaties are binding onsuccessor states because of their “territorialcharacter”. However, the reasons adducedbelow make these treaties as invalid as anyother colonial era treaties.

Secondly, it is clear from the discussion inchapter IV that the strongest reason forclaiming that the Nile Water treaties arebinding is the doctrine of dispositive treaties.But it has already been shown that there isinsufficient evidence for the existence of sucha category of treaties as an exception to thegeneral rule of non-transmissibility.

Moreover, in the absence of the doctrine ofdispositive treaties, some other basis for thesurvival of the Nile water agreements mustbe demonstrated. These alternative theoriescould be servitudes, acquiescence or the ideaof law-creating treaties (Lester, 1963). Butnone of these have been shown to be thereason for the survival of the Nile treatiesand authorities are in agreement that thesetheories are inapplicable to the case of theNile water agreements.

Thirdly, it has been implied by Egypt andsome publicists that the validity of the Nilewater agreements, their devolution onsuccessor states, and their being binding inperpetuity is inferred from the intention ofthe parties. It is sometimes suggested thatthe description of a treaty as localised mayrefer to the intention of the high contractingparties with regard to the effect upon thetreaty of alienation of territory to which it

customary internationallaw as having terminated.The period of two years isintended to facilitatediplomatic negotiations toenable the interestedparties to reachsatisfactory accord on thepossibility of thecontinuance ormodification or terminationof the treaties” (Mutiti,1976:114).

But recently, at a water conference inNairobi, the Minister for WaterDevelopment, Mr. Kipngeno Arap Ngeny,inexplicably stated that the 1929 Nile WaterAgreement was binding on Kenya”(DailyNation, Saturday 23 March 2002, page 4).Some top government officials have evendenied the existence of such treaties.

This kind of ambivalence encourages theassumption and belief that the EgyptianGovernment’s position on the Nile is thetrue and legal position.

5.1 The Case AgainstThe thesis of this paper is that the NileWater agreements concluded during thecolonial era are not binding on the successorstates of the Nile basin and that this is theposition in international law as buttressedby the practice of the states. The followingreasons support this thesis.

First, the majority of commentators, withthe distinct exception of Egyptians havecome to the conclusion, or taken theposition that these treaties are not binding(see Godana, 1985:144-157). The onlycontroversial cases appear to be the 1929

18

27

doctrine on state succession to treaties andhave thus refused to be bound. Availableevidence also shows that states on the Nileare taking unilateral decisions (or sub-basinapproaches towards) in the utilization anddevelopment of Nile water resources.

Lastly, and independently of the above, theconduct of Egypt with regard to theutilisation of the Nile Waters raises seriousdoubts about her capacity to bind co-riparians to their treaty and customary lawobligations. Writing in 1958, Pompesubmitted that the upper-basin states,already before their independence,

“Could certainly not beheld to the obligationswhich they undertooktowards Great Britain bythe aforementionedagreements of whichGreat Britain asadministering powerundertook towards Egyptby the 1929 agreementwith regard to theconstruction of worksaffecting the Nile flow, ifEgypt, or for that matterthe Sudan were toconstruct dams whichwould change the naturalconditions of the Nile Basinto the seriousdisadvantage of theupstream states.” (Pompe,1958:287, Godana,1985:146-7).

In this connection, the building of theOwen Falls Dam (resulting in a rise of twoand a half meters in the level of LakeVictoria), the Jonglei Canal project andparticularly the diversion and piping of Nile

has been specifically applied, and that suchintention might be

“that the new sovereignwill automatically bebound by the treaty”(Lester, 1963:490). But theattitudes of Egypt and theUnited Kingdom and theprovisions in the treaties donot evince suchan”intention.

Fourthly, there is the doctrine of rebus sicstantibus. This doctrine asserts that ifcircumstances, which constituted anessential basis of the consent of the partiesto be bound by a treaty, undergo such far-reaching changes as to transform radicallythe nature and scope of obligations still tobe performed, the agreement may beterminated on the initiative of a party. It issubmitted that the changes introduced bythe decolonisation process and theemergence of independent states in areaswhich were formerly territories underBritish administration are of suchfundamental importance as to permit theoperation of the doctrine of rebus sicstantibus, and that the declarations of thenew states to the effect that the treatiesentered into by former colonial powers ontheir behalf does not bind them is theirinitiative to terminate these treaties. Nilewater agreements could, therefore, notsurvive colonialism.

Fifth, state practice is inconsistent with anyclaim of validity of the Nile water treaties.To this end, Great Britain had adopted theattitude that these treaties should be re-negotiated, and all states on the Nile basin(except Egypt) have adopted the Nyerere

19

28

water to Sinai Desert. (Okidi, 1999,Mbaria, 2002), and its reported sale to Israelwould appear to be conduct that shouldrelease the upper riparians from anyobligation towards Egypt. If Egypt can doas she pleases with the water, why shouldthe other riparians be restricted?

The position adopted by Egypt on the legalstatus is dictated more by self-interest thanby international law and state practice.That may explain her frequent resort tothreats of military action and other “sabre-rattling behaviour.”

20

29

applicable to international rivers or othershared water resources, in the absence ofparticular law in the form of treaties. Thesedoubts have now been dispelled.

But such general law as has recentlydeveloped is not yet a fully-fledged system,as uncertainty remains on the scope ofspecific principles or rules. (Godana,1985:135).

International law is particularly contentiouson the issue of territorial sovereignty ininternational relations arising from the non-navigational uses of watercourses. Asummary of the contending theories ofwater rights illustrates the problem. Theessential point to note here is that due tothe underdevelopment of international law,states are able to assert an almost infiniterange of contradictory and mutuallyexclusive doctrines and principles whenevertheir interests demand that they do so.

There are two conflicting water rightstheories known to international law.These are the doctrine of absoluteterritorial sovereignty (“the HarmonDoctrine.”) and its antithesis, theabsolute territorial integrity doctrine.Absolute territorial sovereignty doctrineholds that a state has the right to dowhatever it chooses with the waters thatflow through its boundaries, regardless ofits effect on any other riparian state.Under this doctrine, a lower riparian hasno recourse but to hope for cooperationfrom the upper riparian or threatenmilitary action.

VI. THE NILE: IN SEARCH OF A LEGAL REGIME

The import of the conclusion that the NileWater Treaties are no longer binding andoperational is that only post-colonialagreements can be said to be valid. The onlysuch treaty is the 1959 agreement for thefull utilisation of the Nile waters. Thisagreement is a bilateral arrangementbetween Sudan and Egypt, which does notbind or affect the other riparian states ofthe Nile. Thus, the legal regime governingthe utilisation of the waters of River Nile iscustomary international law. As theinternational law commission advised:-

“In the absence ofbilateral or multilateralagreements, memberstates should continue toapply generally acceptedprinciples of internationallaw in the use,development andmanagement of sharedwater resources”(Biswas,1993:175).

What then does international law say aboutshared water resources?

6.1 Customary International LawInternational law concerning internationalfresh water resources has been vague andgenerally not accepted by states (Kukk andDeese, 1996:52). International water lawas one of the new areas of the law of Nationshas not yet fully coalesced into firmprinciples and rules. The problem here isnot just one of lacunae in the law. Untilvery recently, there was doubt as to whetherthere were any principles and rules ofgeneral international law, which were

21

30

Writers, state practice and jurisprudencehave all consecrated this theory, which isgenerally accepted today (Godana,1985:40). It is the overall position ofinternational law then, that while eachstate enjoys sovereign control within itsown boundaries where internationaldrainage basins are concerned, it may notexercise such control over the portions ofsuch basins located in its territory withouttaking into account the effects upon otherbasin states.

The customary international law conceptof reasonable or equitable utilisation hasnow been granted the status of law by theUnited Nations …. on the Law of the non-navigational uses of InternationalWatercourses adopted in 1997 (36 I.L.M.700). Article V of the convention statesthat parties shall utilise an internationalwatercourse in an equitable and reasonablemanner. Article VI then gives the factorsto be considered in determiningreasonableness. These are “all relevantfactors and circumstances, including”:-

(a) Geographic, hydrographic,hydrological, climatic, ecological andother factors of a natural character;

(b) The social and economic needs ofthe watercourse states concerned;

(c) The population dependent on thewatercourse in each watercourse state;

(d) The effects of the use or uses of thewatercourses in one watercoursestate on other watercourse states;

(e) Existing and potential uses ofthe watercourse;

(f ) Conservation, protection,developments and economy of useof the use of the water resource of

Absolute territorial integrity is the oppositeview. Under this doctrine, an upper riparianmay not harness a river if this would harma lower riparian. Every state must allowrivers to follow their natural course; it maynot divert the water, interrupt or artificiallyincrease or diminish its flow. The doctrinereflects the claim that there is a principle ofgeneral international law that substantiallyrestricts the water uses of the upstream state.

As would be expected, upper riparians havebeen quick to adopt the absolute territorialsovereignty doctrine. On the Nile Basin,Ethiopia has consistently subscribed to theHarmon Doctrine (Godana, 1985:33-4,Bruhacs, 1993:44). On the other hand,absolute territorial integrity is the commonposition of lower riparians. On the NileBasin, Egypt has persisted in asserting thisdoctrine (Lipper, 1967:18).

Many scholars believe that both absoluteterritorial sovereignty and absoluteterritorial integrity are untenable as trans-boundary water-sharing regimes, andneither is generally accepted as a norm ofcustomary international law.

Therefore, a third approach, essentially acompromise position between the two, hasbeen developed. This is the limitedterritorial sovereignty doctrine, also knownas the limited territorial integrity doctrine.Under this doctrine, every state is free touse the waters flowing on its territory, aslong as such utilisation does not interferewith the “reasonable utilisation” of waterby other states. In short, states havereciprocal rights and obligations in theutilisation of the waters of theirinternational drainage basins.

22

31

therefore, be managed effectively throughthe use of general rules universally appliedto all watercourses. The particular characterof international watercourses requires theconclusion of treaties, preferably bilateralor restricted multilateral treaties.

The second is the problem of reciprocity.International law has been based uponasymmetry of obligations, on mutualadvantages granted by the states to eachother on the basis or reciprocity. In thecase of international watercourses, therespective states are in an unequalsituation, as a consequence of the relativeunidirectional character of the relevanttrans-frontier effects.

This upstream/downstream relationshipcreates a permanent situation of conflict,and makes international law-makingdifficult. The particular character ofinternational watercourses essentiallyrequires bilateral law-making but theabsence or limits of reciprocity hereconstitutes a serious obstacle. Anassumption has usually been made that anupstream state does not need theestablishment of international legal rules onaccount of its favourable situation (beatipossidentes). But this has led to overconcentration on the problem of lowerriparian. This leads to the complaint thatinternational law “has focused on theconcerns of downstream states withoutproviding real incentives for upstreamstates” (Lupu, 2000:366).

In 1997, the United Nations adopted theConvention on the Law of the Non-Navigational uses of InternationalWatercourses. But the convention, which

the watercourse and the costs ofmeasures taken to that effect;

(g) The availability of alternatives, ofcomparable value, to a particularplanned or existing use.

However, the adoption of the limitedterritorial sovereignty doctrine ininternational law has not solved theproblem of water rights in internationalwatercourses. The main reason why thisdoctrine presents complications is that thedefinition of “reasonable” is unclear:-

“The substantive law onthe utilisation of sharedwater resources is definedin the vague language ofthe doctrine of equitableutilisation and offers littleguidance to states on howthey may proceed lawfullywith the utilisation of“thesewaters in their territories”(Wouters, 1997).

The consensus of opinion appears to be thatcustomary international law is not acomprehensive framework for theregulation of the utilisation of internationalwatercourses. The law is underdevelopedand vague, with weak or non-existentmechanisms for enforcement.

Two other inherent limitations have beennoted. The first is that each internationalwatercourse constitutes a specific unitwithout an equal counterpart and withdisparate types of hydrologic, economic andpolitical conditions. In other words,international watercourses have a particularcharacter from a geographic, economic,social, political and legal point of view(Bruhacs, 1993:53). They cannot,

23

32

structure or a restricted multilateral treatyregime or both. Writing in 1960, Garretsonobserved as follows:

“Nearly all thecommentators on theproblems of the fulldevelopment of the Nilebasin have concludedtheir various analyses witha suggestion in one form oranother of the need for aNile river Basin Authority orAdministration” (1960:144)

This idea is supported by Godana (1985),who points to the realisation that the fulldevelopment of the Nile can only be madepossible through agreements which areconcluded between all the basin states andin which all interests are taken into account.He then adds:

“Basin states are bound togain much from thecreation of acomprehensive Nile BasinCommission serving as aninstitutional vehicle forcooperation. Above all,such a commission wouldensure cooperation in therational planning,conservation anddevelopment of resourcesof the basin as a whole”(page 264).

Okidi (1999) is also in favour of aninstitutional structure for cooperation inthe management of the Nile. But a basinwide institution for the management ofthe Nile has never been established. Infact, the existence of sub-basin

attempts to modify and develop norms ofcustomary international law, is only a partialresponse to the limitations of internationalwater law.

The convention adopts the vague conceptof “reasonable and equitable” use (Article5). It then pins its faith on the negotiationof “watercourse agreements” as theinstitutional and normative framework forregulating the use of international waters(Articles 3 and 4). In other words, it doesnot add anything to the law as it existedbefore 1997, and most commentators donot think it provides a basis for regulatingthe use of international watercourses (Kahn,1997, Hey 1998).

The weakness of the customaryinternational legal regime has created orencouraged interest in the development ofother approaches to the management ofshared water resources. An interesting oneis based on the theory of community ofinterests in the waters. Here, internationalborders would be ignored and the riverbasin would be administered as a collectivewater resource by an internationalinstitutional structure. A single state wouldneed cooperation from its co-riparians tomake any use of the shared water (Godana,1985:48-9, Cohen, 1991).

At this stage it may be appropriate toconsider the situation of the Nile.

6.2 The Case for a Nile BasinCommissionThe management of the Nile watersrequires either an international institution

24

33

The imperative of an internationalinstitutional structure for the managementof international water resources is arrivedat by Beavenisti (1996) through a differentroute: the logic of collective action. Thebasic argument is simple. Internationalrivers are a unique type of good. Unlikeinternal resources, controlled by a singlestate, they are not a purely public good towhich all states enjoy potentiallyunrestricted access, like the high seas, themineral resources of the deep seabed, theelectromagnetic spectrum and space.Freshwater resources that traverse politicalboundaries are a collective good to whichonly the riparian states enjoy access. Eventhough other states are excluded from usingthem, the riparian states still need toregulate their respective rights andobligations. To obtain the optimalutilisation of these resources, the riparianstates must act collectively.

Benvenisti’s approach is useful in anothersense. It explains why cooperation throughcommon action has been difficult toinstitutionalise, and demonstrates theimportance of international law inencouraging it. Again the proposition isstraightforward. The classical distinctionamong types of goods in economicliterature is between “pure public”and”“pure private”.

Pure public goods are goods whose benefitsare non-excludable and non-rival. They arenon-excludable because it is impossible orprohibitively costly to prevent outsidersfrom gaining access to them. They are non-rival because a user’s consumption of a unitof that good does not detract from itsbenefits to others. In contrast, the benefits

institutional arrangements notwithstand-ing (Kasimbazi, 1998):-

“The pursuit in the Nilebasin of nationalist endswith national means withinnational frontiers in thehope that regional andinternational difficultiescan be avoided”.

remains the typical approach of the Nilebasin states (Garretson, 1960:144).

The importance of river basin organisationshas been emphasized by Kukk and Deese(1996). According to them, one reasonwhy political tensions and conflict arecommon along some international riversis the lack of river basin organisations.Where such organisations are establishedin water scarce areas, they provide ameans for voicing and resolving waterissues without resort to force.

A famous example is the Organisation forthe Development of the Senegal River(OMUS). It is said to have beeninstrumental in averting internationalconflict among the riparians, and to havefostered such strong cooperation amongthem as joint owners of all major river worksalong the basin that it is used as a model bythe United Nations and the World Bankwhen developing plans for managing otherbasins (Rangeley, 1994).

Establishing an international river basinorganisation, authority, or commission isone of the best solutions for preventing andresolving water conflicts because it engageswater scarce as well as water rich countriesin negotiations.

25

34

excluding outsiders from using common-pool resources gives the limited number ofinsiders the opportunity to coordinate theiractivities in the interest of the optimal andsustainable use of the water, and therebyavert a tragedy of their commons.Why then, would they not cooperate toavert a tragedy of their commons?

Since different states enjoy access to sharedfreshwater, they face a “collective actionproblem”. Each has an interest in gettingmore out of the resource, and these interestsconflict with each other. The key tocooperation lies in the solution of thecollective action problem.

In this regard, it is possible to identify areaswhere international law may proveinstrumental in enhancing states’ willingnessto cooperate, and there are at least three suchareas: direct interaction, substantiverequirements and effective institutions.

First, by insisting on negotiations as thebasis for any arrangement, the law can prodthe riparians to establish direct interaction.

Secondly, the law can prescribe minimalstandards for water allocation, waterquality and the sustainable developmentof the resource.

Finally, the law may offer riparianscontemplating cooperative institutionalmeans of enforcing commitments andensuring long-term interdependence(Benvenisti, 1996:400).

However, cooperation can only trulyemerge from a genuine realisation of shared

of a private good, such as a loaf of bread,are fully excludable and rival. The user mayprevent others from using it and theconsumption of any part detracts fromthe whole. Positioned between pureprivate and pure public goods are twoother types of goods;

(a) Impure public goods that are non-excludable, yet rival, which may beconsumed by all who gain accessto them but whose consumptiondetracts from the consumption ofothers (for example, fisheries in theoceans, open-access pastures), and

(b) Common pool resources, which arepartially excludable and rival.

International freshwater resources, to whichonly the riparian states enjoy access forpurposes other than navigation, are anexample of common-pool resources. Theirbenefits are partly excludable. In contrastto open-access commons, such as high seasfisheries and the electromagnetic spectrum,non-riparians have no access to the waterresources and cannot benefit form themdirectly. Their benefits are also rival, sinceany unit of water diverted or polluted byone riparian reduces the amount availableto the other riparians or its quality.

Both impure public goods and common-pool resources are susceptible to the tragedyof the common “syndrome” in which eachof the appropriators receives direct benefitsfrom its unilateral act, while the costs ofthe act are shared by all (Harding, 1968).

There is, however, a crucial distinctionbetween common-pool resources andimpure public goods: the possibility of

26

35

utilisation of shared water resources. Notonly because customary international lawis underdeveloped, but also specificallybecause the state of the law requires andrecommends it, restricted multilateraltreaties must be negotiated for the majorinternational river basins of the world. Thishas been accomplished in the case of mostbasins. The Nile is a curious exception.

In negotiating a multilateral treaty, thebargaining is going to be between upperriparians and lower riparians. Thecollective and joint interests of theseupstream/downstream countries dictatethis. East African countries shouldprepare for this bargaining.

interest in the water resource. Thepracticality and inevitability of negotiationbetween upper and lower riparians cannotbe over-emphasised. In the case of the Niletherefore, the states must address their“collective action problem” instead ofbasing their claims on conflicting andoutmoded theories of water rights, orhistorical relics.

6.3 The Case for a RestrictedMultilateral TreatyAs demonstrated above, international lawis too general and inchoate to address theproblems of particular international basins.At the same time, collective action isinevitable in the promotion of peaceful andsustainable international cooperation in the

27

36

The need to negotiate a legal andinstitutional framework for themanagement and utilisation of the watersof the Nile has been canvassed in this paper.Such a “framework” should take theinstitutional form of a Basin Organizationand the normative form of a restrictedmultilateral treaty. The states in the EastAfrican region need to take a commonposition on the Nile question, and moreimportantly to develop that position inpreparation for negotiations with otherriparian states.

7.1 The Case for a CommonEast African PositionThe logic of a common East Africanposition on the Nile question is dictatedby a number of considerations. Theseinclude the pact signed by Egypt and Sudanin 1959, the fact that the East Africancountries are upper riparians, the idea ofregional integration, their sharing of LakeVictoria, the history of sub-basin initiativesand the war in Sudan.

(a) The Egyptian-Sudanese Pact (the1959 Treaty)In 1959 Egypt and Sudan signed anagreement, (“The 1959 Agreement for theFull Utilisation of Nile Waters”) whichguaranteed that 55.5 billion cubic metersper year would flow into Egypt without anyhindrance from Sudan. The agreement alsoallowed Egypt to construct the Aswan Damfor “long term” water needs. Mostimportantly, the agreement was a pactbetween the two countries to act together,and against the upper riparian states of the

Nile. Article V, in purporting to recognisethe rights and interests of these other co-riparians provided:

“Since other ripariancountries of the Nilebesides the Republic ofthe Sudan and the UnitedArab Republic claim ashare in the Nile waters,both republics agree tostudy together theseclaims and adopt a unifiedview thereon”.

This commonality of interest expressed inthe form of a binding commitment by thetwo states dictates that other states withcommon interests should also take acommon position on Nile waters interests.As Okidi (1999) has observed”:-

“Since Egypt and Sudanhave retained theircommitment for acollective bargainingposition, it may beappropriate for Kenya,Tanzania and Uganda,and possibly Rwanda andBurundi to have acommon position” (pages42-3).

(b) The Upper Riparian ScenarioThe interest conflict in sharinginternational rivers is between upperriparians and lower riparians. As alreadyindicated, the problem lies in thediametrically opposed theories of waterrights, which these two groups of riparianstend to take.

VII. THE NILE QUESTIONS: IMPLICATIONS FOR EAST AFRICA

28

37

these”“new” post-colonial states could notassert an interest in the waters of the Nilebefore they were born into statehood.

The upstream/downstream relationshipbetween the two groups of riparians, andtheir unequal situation, dictates that EastAfrican countries should develop aposition that is common as amongstthemselves, but may be different fromthat of the lower riparians.

(c) Regional IntegrationThe East African region, which shares acommon colonial history, has beenexperimenting with various forms of regionalcooperation since the end of the SecondWorld War. These efforts have resulted in theestablishment, by treaty, of the East AfricanCommunity, whose partner states are Kenya,Uganda and Tanzania.

The objectives of the community are todevelop policies and programmes aimed atwidening and deepening cooperationamong the East African states in political,economic, social and cultural fields,research and technology, defence, securityand legal and judicial affairs, for theirmutual benefit (Article 5). The PartnerStates of the community undertake toestablish among themselves a customsunion, a common market, subsequently amonetary union and ultimately a politicalfederation. Clearly, the East Africanregion will be transformed into a singlepolitical unit for purposes of the exerciseof sovereignty.

In matters relating to natural resources, thecommunity is to ensure “the promotion ofsustainable utilisation of the natural

As a general rule, upper riparians insuccessive rivers have asserted claims toindividual property rights in the part of theriver flowing in their territory (e.g. theHarmon Doctrine), while lower riparianshave made the opposite claim, insisting onthe principle of non-interference with thenatural flow of the river in their territory.

The “inherent conflict” is exacerbated bythe problem of absence reciprocity in thesharing of successive rivers, caused by theunidirectional flow of trans-boundaryeffects. Upper riparians are expected tosacrifice for the benefit of lower riparianswho do not bear responsibility for the costs.For example, a rule forbidding causingharm to co-riparians in the use of a sharedriver benefits lower riparians, andparticularly the lower most, at the expenseof upper riparians. It is difficult to see whatthe lower riparian can do to cause harm tothe upper riparian.

For the case of the Nile, an accident ofhistory has complicated the relationshipbetween upper and lower riparians evenfurther. Historically, the lower mostriparian started using the waters of theNile earliest - “from antiquity”. It waslater followed by the next (Sudan) inasserting interest in the use of the sharedwaters. The upper riparians meanwhilebecame states as a result of colonisationat the end of the 19th Century, emerginginto full statehood after 1959.

Although other civilizations andpredecessor states living on the Nile Basinmust have relied on the waters of the Nilefrom antiquity (some are actually culturallyand linguistically identified as “Nilotics”!)

29

38

African states to take a common positionon the utilisation and management of theNile waters resources.

(e) Sub-basin InitiativesThe importance of sub-basin initiatives inthe management of the Nile basin resourceshas been formally acknowledged by scholarsand commentators on the subject(Kasimbazi, 1998). In the absence of abasin-wide agreement on the utilisation ofthe Nile waters, a number of sub-basininitiatives have been developed by like-minded co-riparians. These include the1959 Agreement between Egypt and theSudan and the development projectsinitiated under its auspices.

In the East African region, the sub-basininitiatives most relevant to the utilisationof the Nile waters are the Kagera BasinOrganisation, the Lake VictoriaEnvironment Management Programme(LVEMP) and the Lake Victoria FisheriesOrganization (LVFO). The agreementestablishing the Kagera Basin Organisationwas concluded in 1977 between Tanzania,Rwanda and Burundi. Uganda acceded tothe treaty in 1981 (Godana, 1985: 191-3;Kasimbazi, 1998: 29-30).