THE LINGUIST - Horace Mann School€¦ · issue of The Linguist, a magazine dedicated to showcasing...

Transcript of THE LINGUIST - Horace Mann School€¦ · issue of The Linguist, a magazine dedicated to showcasing...

2

Letter from the Editors:

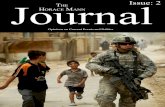

We are very excited to present the second issue of The Linguist, a magazine dedicated to showcasing the linguistic and cultural diversity at Horace Mann and worldwide. This year, we are doing a spotlight on New York City and its surrounding area, the melting pot in which hundreds of languages are spoken.

Students have written on various ethnic neighborhoods, the history of the city, personal experiences, and more. All pieces were written in foreign languages and are accompanied by an English translation. We hope the issue will create a greater appreciation for the multitude of languages and the cultural richness of the area in which we live.

Sincerely, Isaac and Joanna

Editors in Chief: Isaac Grafstein & Joanna ChoCreative Director & Photography: Andie FialkoffFaculty Advisor: Susan Carnochan

3

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

Table of Contents:

La Toulousaine BakeryGina Yu

Spotlight on Washington Heights Benjamin Fink

Being Polish in NYCKasia Kalinowska

Dutch Legacy in New YorkNoa Meerschwam

Spotlight on WilliamsburgSabrina Lautin

Moroccan Jews in the CityTali Benchimol

Spotlight on Little ItalyIsaac Grafstein

A City of ImmigrantsLibby Smilovici

A Review of Kunjip RestaurantSeunghyun Chung

4

8

10

14

16

18

22

24

28

4

Mon amour avec la langue Française a commencé quand j’avais 5 ans. En habitant à New York, c’était facile de nourrir cette volonté de savoir la langue. Tout simplement, j’avais la chance. Et moi, je travaille à une petite boulangerie, qui s’appelle La Toulousaine. Le jour commence avec les huit premiers sons de « Alors on Danse. » Je quitte ma maison et le soleil brille, l’or jette par le bleu de matin. Quand j’arrive à la boulangerie, l’air est épais et plein de la pâte des croissants et baguettes. Le tranquille sourire de Nabou et la grande voix de Jean-Francois me saluent. Le calme de 6h30 de matin attire peu de gens, sauf ceux qui commandent leurs simples cafés noirs et leurs croissants pour em-porter. Les pâtisseries exsudent une chaleur et je me mets un grand café noir et je fonds au goût du pain au chocolat. Je le chasse avec le jus brun et amer de New York. Les gens qui entrent sont un ensemble étrange, de ceux qui sont vraiment ennuyeux jusqu’à ceux qui sont incroyablement bizarres. Parfois, quand je travaille, je pense à son authenticité, que ça c’est le vrai New York. C’est les clients parlant en anglais, français, espagnol, portugais, coréen et allemand. C’est une petite opération, avec une équipe de 10 personnes qui servent toute Manhattan. Il y a un truc spécial et irremplaçable de travaillant à New York, parce que même dans une boulangerie, les lignes culturelles disparais-sent et ils deviennent une collection homogène. Plein de soupe à l’oi-gnon.

French:

La Toulousaine Bakery

5

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

Gina Yu

My love of the French Language started when I was 5 years old. Liv-ing in New York, it was easy to nourish this love- I was and am lucky. I get to work at a small bakery called La Toulousaine. !e day starts with the "rst eight notes of Stromae’s “Alors on Danse” rising to a crescendo. I leave my house and the sun leaks through the morning sky’s thin blue screen, the gold dripping with new warmth, ooz-ing through the caustic yet stagnant early air. When I arrive, the whirling baguette and croissant laden air is thrust into my olfactory glands. Na-bou’s easy smile and either Jean-Francois’ booming voice and intimidating stature or Nora’s petite frame and large heart bid me good morning. !e hush of 6:30AM draws few people, save those who order their no-frills large co#ees and croissants in to-go bags. !e pastries ooze heat, the still air thick and doughy. I fashion for myself a large cup of iced black co#ee and melt at the taste of the Dijon and Swiss Cheese Croissant en-veloping my mouth and savor each bite, chasing it with sips of the bitter brown juice of New York. Time is momentarily suspended and I exhale. !e people who enter are an amalgam of characters, ranging from stunningly monotonous to bizarre beyond belief. Sometimes, as I am working, I think about the authenticity of it all- that this is the real New York. It is having customers speak in English, French, Spanish, Portu-guese, Korean and German. It is having French customers that stop by just to say hello to the owner, who just so happens to be the main chef. It is having a small-scale operation, and a daily team of 10 people serves what can sometimes feel like the entirety of Manhattan. !ere is something special and irreplaceable about working in New York, because even in a French bakery, the cultural lines blur and they become the quintessential melting pot. Full of French Onion soup.

La Toulousaine Bakery

8

El barrio de Nueva York que está más al norte de la ciudad es Washington Heights. Esta zona se llama Washington Heights por dos razones: para recordar Fort Washington, que sirvió de fortaleza durante la Guerra Civil Americana y para desta-car que la elevación natural más alta de la ciudad de Nueva York está aquí. El área, que originalmente sirvió de terreno para las haciendas de la aristoc-racia de Nueva York, entre ellos el señor John James Audobon (de la Sociedad Au-dobon), tiene como perímetro la calle 115 al sur, la Calle Dykman al norte, y el Río Hudson al oeste. Cuando el metro, un sistema de transporte público, llegó al área, varios grupos de inmigrantes y otros neyorquinos se mudaron al área. Llegaron los irlandeses, los judíos europeos, los afroamericanos, los griegos y los cubanos. A lo largo de los últi-mos treinta años, fueron los dominicanos los que lo habitaron y hoy en día, Washing-ton Heights tiene la población dominicana más grande fuera de la República Domini-cana. Recientemente, los inmigrantes de Ecuador también han empezado a vivir en el barrio. Un diario local, el “Manhattan Times,” está publicado en inglés y español. Fue en Washington Heights donde el famoso activista, Malcolm X fue asesina-do. Otros residentes antiguos de este barrio incluyen al músico de jazz, Count Basie, el beisbolista Lou Gehrig, y Pedro Álvarez, ex-alumno de Horace Mann y actual beis-bolista de los Pittsburgh Pirates. Muchos profesores de Horace Mann también actual-mente viven en Washington Heights. En los años 80, Washington Heights tuvo que enfrentar a varios ma"osos que tra"caron drogas. Desde principios del Siglo XXI, ha habido una nueva urbanización y hoy en día, además de vistas hermosas, los turistas, tanto como los residentes dis-frutan de la arquitectura de la época, los parques y los museos. Algunos atractivos importantes son: los Cloisters, una parte del Museo Metropolitano de Arte, todo en Fort Tryon Park, Audobon Terrace, con sus mansiones de la época de Beaux Artts, y el museo de la Sociedad Hispanoamericana, además de la casa más antigua de Man-hattan, la mansión de Morris-Jumel. Cada primavera el barrio tiene el Uptown Arts Stroll, un festival de un mes de duración que destaca la diversidad de idiomas y que celebra la cultura de Washington Heights. Otro atractivo que llegará pronto a Washington Heights es el High Bridge, el puente más antiguo de Nueva York, que se está renovando como paseo para ciclistas y peatones en 2014.

Spotlight on...

Spanish:

Washington Heights

9

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

Benjamin FinkWashington Heights

!e northernmost neighborhood in New York City is Washington Heights. !is area is named for two facts: to commemorate Fort Washington, a fort used in the American Revolutionary War and to highlight the fact that this place is the highest natural elevation in all of New York City. Also, because of the steep ter-rain, there are many “step streets,” with the longest totaling 130 steps, but people can take a series of three elevators instead of walking up the many steps. Bounded on the south by 115th Street, to the north by Dykman Street, to the west by the Hudson River and stretching to the East, Washington Heights was originally settled by wealthy New Yorkers for their country estates, including John James Audubon (of the Audubon Society). !en, when the City’s public subway system reached the area, various groups of immigrants and upwardly mobile New Yorkers moved in. !e waves were the Irish, European Jews, African Americans, Greeks, and Cubans. How-ever, for the last thirty years, Dominicans have immigrated to the area and to-day, Washington Heights is the place that has the largest Dominican population outside of the Dominican Republic. Recently, immigrants from Ecuador have moved into the neighborhood, too. A community newspaper called “!e Man-hattan Times” is the local bilingual newspaper, written in Spanish and English. Notoriously, Malcolm X was assassinated in Washington Heights. Fa-mously, past residents of Washington Heights include jazz musician Count Basie, baseball hall-of-famer Lou Gehrig, and Horace Mann’s own Pedro Alvarez who plays for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Currently, many HM teachers call Washington Heights their home. In the 1980s, Washington Heights faced gangster rule with a large, illegal drug trade. However, since the early 2000s, there has been a lot of urban renewal. Today, in addition to the beautiful views, visitors and residents enjoy the histor-ic architecture, parks, and museums. To name a few: the Cloisters, part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, located within Fort Tryon Park, Audubon Terrace, with its Beaux Arts mansions and the Hispanic Society of America museum, as well as the oldest house in Manhattan, the Morris-Jumel Mansion. Each spring, the neighborhood has the Uptown Arts Stroll, a month-long festival that highlights the diverse language and celebrates the culture of Wash-ington Heights. Also, a coming-attraction to Washington Heights is the 2014 opening of the High Bridge, the oldest bridge in New York City, which is being redeveloped as a pedestrian and bicycle bridge.

10

Pierwszy tydzie$ wrze%nia jest zawsze troch& dziwny: szko'a si& znów zaczyna i moje urodziny s( dz-iewi(tego. Jest to tak)e tydzie$ w ci(gu którego musz& uczy* si& ponownie angielskiego. Dobra, przesadzam. Po powrocie z mojich wakacji w Polsce, jest mi trudo przyzwyczai* si& znów mówi* po angielsku. Po rozmowie z przyjació'mi w pierwszych dniach szko'y, zauwa)am )e zapominam prostych s'ów jak „purse” i „vacuum.” Nie mam akcentu ale zawsze odczuwam t( zmani& po dwóch miesi(cach bez j&zyka angielskiego. Polski by' moim pierwszym j&zykiem . Nauczy'am si& czyta* po po polsku jak wi&kszo%* pol-skich dzieci, z Elementarzem który przedstawia histori& dziewczynki o imieniu Ala i jej psa o imieniu As. I pami&tam, )e jest lekko co% o jakim% tam ulu. Moi rodzice rozmawiali ze mn( w domu tylko po polsku. Urodzi'em si& w Nowym Jorku i tam mieszka'am przez cztery lata przed pójs*iem do przedszkola bez wcze%niejszej wiedzy j&zyka angiel-skiego. Jednak, cztero latki maj( swój w'asny j&zyk i nie mia'am trudno%ci w znajdywaniu przyjació'. Po roku, zna'am angielski równie) dobrze jak oni. Moi rodzice nigdy nie powiedzieli mi czy mia'am jakikolwiek polski akcent, ale na pewno nie mam go teraz . Nie zauwa)y'am )e ja jestem nawet troch& inna, a) nie mia'am osiem lat. By'am na obozie letnim w Polsce i moi koledzy zapytali mnie gdzie mieszkam . Roze%mieli si&, kiedy powiedzia'em )e w Nowym Jorku . – Ale) ty nie mówisz po angielsku – mówili. Powiedzia'am im )e owszem, mówi&, i zacze'am si& przedstawia* po angielsku i mówi* o najbardziej ameryka$skiej rzeczy jakiej mog'am wymy%le*, o hamburgerach. Nazywali mnie „hamburgerka” od tego dnia. Nie mog'am by* bardziej dumna. Jak by'am starsza, jednak zacze'em czu* si& troch& inaczej. Zauwa)y'am )e trudniej mi by'o porozumie* si& z wieloma polskimi dzie*mi których spotyka'am, nie dlatego, )e straci'am moje umi-ej&tno%ci j&zyczne, ale dlatego )e nie urodzi'am si& i nie mieszka'am w tym kraju. Zacze'am uczy* si& z czasopism plotkarskich aby zrozumie* slang i odniesie$ kulturalnych. Oni te) nie bardzo rozumi-eli kiedy próbowa'am rozmawia* o ameryka$skich rzeczach– najtrudniejsze by'o wyt'umaczenie im „Glee.” Tak samo z moim )y*iem w Nowym Jorku. Dorastaj(c , wszystko by'o polskie. W szkole przed-stawiana mi by'a Dora the Explorer. Pozna'am Spongeboba w pi(tej klasie. Nawet czasami dzisiaj nie ca'kowicie rozumiem niektóre ma'e rzeczy o kulturze ameryka$skiej bo moje interakcje z moj( polsk( rodzin( w domu s( inne. Ale ogólnie, nie mog'abym by* bardziej wdzi&czny za to )e jestem dwuj&zyczna. To )e by'am w stanie nauczy* si& j&zyka polskiego przed angielskim i utrzyma* go przez te wszystkie lata jest dzi&ki moim rodzicom. Spotykam si& z polsko-ameryka$skimi dziecmi dzi%, i wiem )e wiele z nich nie zna-j( tak dobrze j&zyka lub przynajmniej gramatyki jak ja. Jest to, szczerze mówi(c, do%* niesamowite . Równie) nie szkodzi )e mog& rozmawia* z mam( o kim% kto stoi przy nas i kto nigdy nas nie zrozumie.

Being Polish in NYCPolish:

11

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

Being Polish in NYCKasia Kalinowska

!e "rst week in September is always a little weird. For starters, school starts again and my birthday is on the 9th. It’s also the week during which I have to relearn English. Okay, I’m exaggerating. A+er I return from my annual summer in Poland, I "nd it to be the most bizarre experience speaking English again. When speaking to my friends during the "rst days of school I "nd myself forgetting simple words like “purse” and “vacuum.” I don’t have an accent or anything, but I always presently feel the adjustment a+er spending two months away from the English language. Polish was my "rst language. I learned to read in Polish from the illustrated workbook most young Polish children grow up with: the “Elementarz,” which depicts the story of a girl named Ala and her dog As. I faintly remember there being something about a beehive, or “ul,” as well. My parents spoke only Polish to me at home. I was born in New York and had lived there for four years before I was thrust into my local preschool without any prior knowledge of English. Four year olds have a language of their own, however, so I didn’t have a hard time making friends. By the end of the year, I was just as ,uent as they were. My parents never told me if I had any form of Polish accent then, but I sure don’t have one now. It didn’t hit me that my situation was at all peculiar until I was about eight. I was at a summer camp in Poland and my friends asked me where I lived. !ey laughed when I said that it was in New York. “But you don’t speak English,” they said. I assured them I did and proceeded to introduce my-self in English and talk about the most American thing I could think of: hamburgers. !ey called me hamburger girl from that day forward. I could not have been more proud. As I got older, however, I began to feel a little di#erently. I found it harder to communicate with a lot of the Polish kids I met, not because I had lost any language skills, but because I hadn’t grown up and didn’t live in the country. I found myself “cramming” from gossip magazines to try to understand the slang and cultural references. !ey also didn’t really get it when I tried to talk about my American cultural references--the most di-cult was trying to explain “Glee.” !is carried over to my life in New York as well. Growing up, everything had been Polish. In elementary school I didn’t know who Dora the Explorer was. I was acquainted with Spongebob in the 5th grade. !ere are still times today when I don’t completely comprehend how some American cultural intricacies work just because my interactions with my Polish family at home is di#erent. Overall, however, I couldn’t be more grateful for being bilingual. Being able to learn Polish be-fore English and maintain it for all of these years was a gi+ from my parents. I do meet Polish-Ameri-can kids today, but many of them aren’t as familiar with the language, or at least the grammar, as I am and it feels, quite honestly, pretty awesome. It also doesn’t hurt to be able to talk with my mom about a person with him or her standing within earshot of us and not being able to understand a word we say.

14

Alhoewel de stad die we tegenwoordig New York noemen slechts voor een korte periode onder controle van Nederlandse bestuurders hee+ gestaan, is desalniettemin de culturele invloed van de Ned-erlandse kolonisten op het hedendaagse eiland onuitwisbaar. In 1609, vertrok de Engelse ontdekkings-reiziger, Henry Hudson naar de Nieuwe Wereld. Deze expeditie werd ge"nancierd door het Nederlandse koopvaartbedrijf “De Verenigde West-Indische Compagnie (WIC), en niet door zijn Engelse landge-noten. De geogra"sche landmassa tussen het huidige Massachussetts en Delaware werd in 1614 bes-chouwd als een provincie van de Nederlandse Republiek, en kreeg de naam “De Nieuwe Nederlanden”, o+ewel “!e New Netherlands”. Het was gedurende deze periode dat Peter Minuit, de directeur van deze jonge Nederlandse kolonie, de aankoop bewerkstelligde van het eiland Manhattan, en onder het “Nieuwe Amsterdam Charter” werden, in 1653, de Staaten Eilanden (Staten Island) en de Lange Eilanden (Long Island) aangekocht. De aankoop van het eiland Manhattan, wordt tot op heden nog betwist. Het enige bewijs van deze aankoop van de Lenape Indianen, voor de somma van zestig gulden, bestaat uit een brief, geschreven door een Nederlandse vertegenwoordiger van de WIC, Peter Schagen, waarin de logistieke handelingen van deze investering staan beschreven. De Nederlandse aanschaf van “New Amsterdam” resulteerde tevens in een overdracht van Ned-erlandse culturele normen en waarden, en deze zijn tot op vandaag de dag nog in New York terug te vinden. Veel stadsdelen in- en rondom New York dragen nog steeds benamingen die zijn gebaseerd op Nederlandse steden; Harlem (naar de Nederlands stad Haarlem), Flushing (naar de Nederlandse stad Vlissingen, in de Zuidelijke provincie van Zeeland), Yonkers (naar de Nederlandse kolonist, Jonkheer (Esquire) Adriaen van der Donk), Gravesend (‘s Gravezande), the Bowery (naar “De Bouwerij”, de bo-erderij van Peter Stuyvesant in New York), !e Bronx (naar de Nederlandse kolonist Jonas Bronck) en zelfs Van Cortlandt Park (naar de eerste Burgemeester van Nederlandse a.omst in New York, in de 17e eeuw, Stephanus van Cortlandt). In dezelfde geest is het Nederlands word “kils” (‘stream”) terug te vinden in vele regio’s in de staat New York; zoals de Catskill bergen, de Westkill berg, en de stad Peekskill. De Nederlandse cultuur hee+ ook diverse humanitaire sectoren in de gemeenschap geïnspireerd, zowel in lit-eratuur als in educatie. Het wereldberoemde boek van Washington Irving, “Rip van Winkle”, is gebaseerd op Nederlandse volksverhalen, en het oudste gebouw dat dienst doet als middelbare school in de stad New York, “Erasmus Hall Campus”, is genoemd naar de beroemde 15e eeuwse Nederlandse renaissance geleerde en humanist, Desiderius Erasmus. De vlag van de steden New York, Albany, en Nassau, bestaan uit dezelfde kleuren als de oude Nederlandse vlag; blauw, wit, en oranje. Deze kleuren worden nog steeds gebruikt in de uniformen van de New York Knicks, het basketbal team van New York, terwijl ook de naam van zowel de Knicks als die van de Yankees van Nederlands origine is. Vanaf het prille begin, rond 1600, hee+ de Nederlandse cultuur invloed uigeoefend op de samen-leving in New York. Ondanks dat noch de Nederlandse taal, noch de Nederlandse religie van blijvende invloed is geweest, hee+ desalniettemin de Nederlandse cultuur haar stempel gedrukt op de geschiedenis van New York, en het ziet ernaar uit dat New York dit cultuurgoed zal blijven behouden.

Dutch:

Dutch Legacy in New York

15

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

Noa Meerschwam

Dutch Legacy in New York While the Dutch only controlled the area we now call New York for a brief period of time, the cultural heritage that the Dutch settlers le+ behind on the island have proven to be long lasting. In 1609, the English voyager Henry Hudson traveled to the New World. !is expedition, however, was funded and sponsored by the Dutch West India Company, not the English. By 1614, the geographic area situated between modern-day’s Massachusetts and Delaware was deemed a province of the Dutch Republic and was named New Netherlands. It was around this time that Peter Minuit, the director of this new Dutch colony, purchased the island of Manhattan, and by 1653, under the New Amsterdam Charter, Staaten Eylandt (Staten Island) and Lange Eylandt (Long Island) were bought. !e purchase of the island is still up for debate. Bought from the Lenape Indians for 60 guilders, Peter Schagen, the Dutch liaison between the government and the Dutch West India Company, wrote to the government of the purchase, and is the only real proof of the logistics of the investment. !e purchase of New York resulted in an acculturation of Dutch values and customs that are evident to this day. Many areas are named using Dutch roots such as Harlem, Flushing, Yon-kers, Gravesend, the Bowery, the Bronx and even Van Cortlandt Park. Similarly, the Dutch word kils (“stream”) is used in many regions of the state such as Catskill, Westkill, and Peekskill. Dutch culture also inspired many humanitarian sectors of society, such as literature and education. Wash-ington Irving’s famous book “Rip Van Winkle” was inspired by Dutch folktales and the oldest high school building in New York City, Erasmus Hall Campus, is named a+er the Dutch 15th century renaissance scholar, Desiderius Erasmus. !e ,ags of the City of New York, Albany, and Nassau all use the same colors as the Old Dutch ,ag: blue, white and orange. !ese colors are also used in the uniforms of the New York Knicks, New York City’s basketball team; both the Knicks and the Yan-kees take their names from Dutch origins. !e Dutch in,uence in New York has permeated its culture and society since its beginnings in the 1600s. While apparently “key” in,uences such as language and religious ideology did not result, a large sector of society and speci"c aspects of New York’s culture today are clearly Dutch and will preserve the legacy for years to come.

16

Il existe à New york une communauté juive marocaine relativement importante. Ma famille fait partie de cette culture di#érente. Nous allons à la synagogue Maro-caine de l’Upper East Side, Manhattan Sephardic Congregation. Déjà, dans cette petite communauté il y a au moins une centaine de personnes. Mais, ca c’est juste une partie de New York. Par exemple, la plupart de nos copains Marocains vivent dans l’ Upper West Side. Il y en a Downtown aussi. Est-ce-que vous savez qu’il y a sans doute plus de Français-Juifs-Marocains à New York qu’au Maroc? Si vous allez au Lycée Français, vous en verrez beaucoup. Ils ont un accent précis. Je pense que les Français peuvent l’entendre, par contre, c’est probablement plus dur pour les Américains. Ils ne parlent pas que Francais; il y’en a beaucoup qui parlent Espagnol, Anglais, et même Arabe. Il y a plein de traditions qui font parti de cette culture unique. Ces traditions se voient plus particulièrement lors des fêtes juives. A Pessach, il y a Bibilou, ou on fait passer un plateau sur la tête de chaque convive, et la Mimouna pour célébrer la "n de Pessah. Aux mariages il y a la cérémonie du Henné, et à Shabbat le couscous du ven-dredi soir et la da"na du samedi midi sont de rigueur. Les juifs marocains viennent principalement de Meknès, Rabat, Casablanca, et Fès. Aujourd’hui, il n’y a que 5,000 Juifs au Maroc, dont 3,000 vivent à Casablanca. Mais, comment se fait-il qu’il y ait tellement de Juifs-Marocains á New York? Comment sont-ils arrivés? En 1492, la Reine Isabelle a dit aux Juifs qu’ils devaient se convertir ou quitter le pays. C’est comme ca qu’ils sont arrivés au Maroc. En 1967, la Guerre des Six Jours a eu lieu entre Israël et les pays Arabes qui l’entouraient. Jusque là, les Juifs du Maroc se faisaient traiter très bien. Par contre, avec la guerre, et vivant dans un pays arabe, ils se sont trouvés moins en sécurité. La majorité a quitté le Maroc et est partie soit en Israël, en France, ou au Canada. Le Maroc étant alors un pays fran-cophone, le Canada et la France furent des destinations logiques. Beaucoup plus tard, plein de Juifs en France ont decidé de venir aux Etats Unis, et en particulier a New York où il est facile d’être juif. C’était le rêve: le rêve Americain qui existe toujours. Aujourd’hui, une petite partie des 13,000,000 de Juifs dans le monde représente la communauté marocaine. La majorité d’entre eux et en Israël, en France, et au Can-ada. Seul un petit nombre d’entre eux sont à New York, mais cette communauté reste très soudée et attachée à ses traditions.

French:

Moroccan Jews in the City

17

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

Tali Benchimol

Moroccan Jews in the City !ere is a relatively important Moroccan-Jewish community in New York City. My family is part of this distinctive population. We attend the Manhattan Sephardic Congregation on the Upper East Side. Already, in this small little place there are at least 100 people. But, this is just a piece of New York. For example, most of my fam-ily friends live on the West Side or maybe even Downtown. Did you know that there are more French-Moroccan-Jews in New York City than in Morocco? If you were to drop by the Lycée, you would see many. !ey have a very distinct accent that a native speaker could catch in an instant, but may be hard to identify for Americans. Moroc-can-Jews don’t only speak French; they also speak Spanish, Arabic, and English. !ere are many traditions that take part in this speci"c section of Jews. Most of them occur during holidays. During Passover, we perform “Bibilou” while hitting a plateau over people’s heads and we celebrate the Mimouna, which signi"es the last day of the no-bread holiday. During weddings, there is the Henna ceremony. On Shabbat, it is tradition to make Couscous on Friday nights and Da"na Saturday a+ernoon. Most Moroccan Jews come mainly from Meknes, Rabat, Casablanca, and Fes. Today there are only 5,000 Jews in Morocco, 3,000 of which are in Casablanca. How is it that there are so many Moroccan Jews in NYC? How did they get here? In 1492, Isabel, the Queen of Spain, told the Jews that they either had to con-vert to Catholicism or leave. !is is how so many Jews arrived in Morocco. Later, in 1967, the Six-Day War took place between Israel and the Arab Countries surrounding it. Until then, the Jews had been treated with respect. However, with the war, living in Arab countries, they found themselves in a less secure and safe zone. !e major-ity of them ,ed and went either to Israel, France, or Canada. Since Morocco, was a French-speaking country, it only made sense for people to go to Canada or France. Later on, Jews in France began to immigrate to the United States, particularity New York City. !is was the American dream for them. Today, a small part of the 13,000,000 Jews in the world represent the Moroc-can community. !e majority remains in Canada, France, Israel, and Argentina. Even though this community is very small, it still stays very connected to their culture and traditions.

19

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

Williamsburg, BrooklynSabrina Lautin

Williamsburg is a neighborhood in the part of Brooklyn that is close to Man-hattan. Over the years, many writers, families, and other di#erent types of people resided in Williamsburg. Additionally, many religious and ethnic groups inhabit the neighborhood. Judaism is just one of the many religions found in Williamsburg, which is just one of many Jewish neighborhoods in Brooklyn. !e Jews’ ancestors immigrated to Williamsburg a+er World War II. !is neighborhood was the center for the Satmar Jews, one of the many denominations of Orthodox Judaism. !e name “Satmar” originated from the name of the town in Eastern Europe in which the movement was started. !e Satmar Jews are famous for their anti-Zionist views and their attempting to isolate themselves from society. In addition, there is an ongoing con,ict in WIlliamsburg between the Satmar Jews and the Lubavitch Jews because the Satmar believe that the Lubavitch are trying to proselytize Satmar Jews to the Lubavitch sect. Even so, the Satmar Jews aren’t only the cause of strife in Williamsburg. On the other hand, the Satmar Jews manage many organizations within the community, such as “Bikur Cholim” (helping the sick), several yeshivas, and “Rav Tov,” an organization that helps refugees. Williamsburg is merely a microcosm within a larger community, and there are things in today’s world that threaten to upset this equilibrium. !e Israeli government dra+ed all the Orthodox Jews into the Israeli army be-cause multiple political parties believe that the Jews must take part in the war e#ort. As a result of the dra+, the Satmar Jews, as well as all the Jews from around the world, have come to realize that the Jewish communities cannot remain in isolation forever. Just like the changing trends in Williamsburg, the denominations of Judaism within Williamsburg must change in order to stay intact.

21

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

http://travel-for-love.com/2011/10/27/koreatown-thursday-travel-photo/

KOREATOWN

23

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

Kunjip Restaurant Korea Town in the center of the Korean culture in New York. !e area is "lled with shops and restaurants that can usually only be seen in Korea, and Kunjip is one of them. First, the restaurant itself is set up like any other Korean restaurants at Korea – the way that the logs chairs are lined up and the pictures of the “Special Menus” that are "lling up the wall de"nitely plays a role in mak-ing this place a restaurant at Korea. !ere is a comfortable and a busy Korean atmosphere that can’t exactly be explained in words that is around the whole restaurant. All these things make Kunjip look like a kitchen of a common household or a small inn.

Unlike the American restaurants, Korean restaurants serve the custom-ers some small side dishes and things to drink before they even order their meals. Kunjip also served some side dishes – there were many di#erent variet-ies of di#erent dishes that were being served such as seaweed, "shcakes, radish dishes and varieties of Kimchi and vegetable. !ese dishes were not di#erent from the dishes that are actually served at Korean restaurants at Korea. Chilled barley tea was served instead of iced water.

Even the main dishes and the cultures were kept the same at Kunjip. !e more authentic dishes like Bean paste soup and Korean barbeque were not a#ected by American dishes at all, making them exactly like the food from Ko-rea. Rice soup and Ginger–cinnamon drinks that are implicitly almost always served at authentic Korean restaurants were served at Kunjip.

Overall, Kunjip is one of the most authentic Korean restaurants even in Korea town. !e small things that are kept in this restaurant is what makes Kunjip more like the restaurants at Korea. But because Kunjip manages to keep culture together, it makes itself seem like any other Korean restaurants that can be found in the streets of Korea.

Seunghyun Chung

25

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

Old ideas are le+ in the countries they came from. Immigrants, wanting to come to America, where dreams live. Every block having di#erent people, and every day, those people live in New York together.It’s di-cult but worth it.Every day brings di#erent problems, but we would not want to go anywhere else.Each person is beautiful and unique.!e tra-c lights excite your eyes and move you.!is city gives me life.!is city gives us life.

A City of ImmigrantsLibby Smilovici

http://www.libertyharborrv.com/statue-of-liberty

28

In una certa area di Manhattan del centro, le strade diventano strette, come quelle di Venezia. Nonostante l’aria fredda d’inverno, si può sentire gli odori delle spezie, formaggi e ca#è. I ristoranti Italiani, le pizzerie, le pas-ticcerie, i bar e i chioschi di Gelato riempiono le piccola area che si estende per la Strada Mulberry. Le pompe antincendi sono dipinte di rossa, verde e bianco. Le maglie di football si appendono fuori dei negozi dei souvenir. Questo è Little Italy. Una volta, il quartiere era abitato quasi esclusivamente da poveri immigranti Italiani. Era una zona insulare, separata dal resto di Manhattan con sua propria lingua, costumi e istituzione. In seguito le quote d’immigrazione sono state abolite nell’anno 1965, Chinatown si è estesa e ha cominciato a invadere l’area mentre gli italiani hanno iniziatto a trasfer-irsi nelle periferie o Staten Island. Adesso, il quartiere è molto piccolo ma ancora sta prosperando. Little Italy non è più la zona povera che era nel passato. Si tratta di un’at-trazione turistica con edi"ci costosi. Di fatto, si può trovare più turisti che Italiani lì. Gli italo-americani hanno una forte tradizione cattolica, così le strade sono già adornate con decorazioni Natalizie dall’inizio d’inverno. Sicuramente, queste decorazioni aggiungono l’atmosfera turistica alla zona. D’altra parte, c’è una grande varietà di specialità italiane nel quartiere. La gente si trova aspettando in "la per comprare i cannoli, il prosciutto, il ca#è, le spezie, e altri cibi deliziosi. Oltre ai prodotti buonissimi, Little Italy ospita il museo italo-americano, che o#re mostre interessanti per tutto l’anno. La prossima volta quando stai pensando di andare in centro, pensa veramente a visitare la Strada Mulberry. Little Italy è sicuramente un luogo da visitare.

A Spotlight on...

Italian:

Little Italy

29

2013-2014 | Volume II, Issue I

In a certain area of lower Manhattan, the streets become narrow, like those of Venice. Even in the cold winter air, one can smell spices, cheeses and co#ee. Italian restaurants, pizzerias, pastry shops, bars, and gelato stands permeate the small area that extends down Mulberry Street. Fire hydrants are painted red, green and white. Soccer jerseys hang outside souvenir shops. !is is Little Italy. !e neighborhood was once inhabited almost exclusively by poor Italian immigrants to New York City. It was an insular town, separated from the rest of Manhattan, with its own language, customs, and institutions. However, as immigration quotas were li+ed in 1965, Chinatown grew and began to encroach on the area as Italians began to move to the outer suburbs or Staten Island. Now the neighborhood is very small, but it is still thriving. Little Italy is no longer the poor area that it once was. It is a high-rent tourist attraction. In fact, one can spot more tourists there than Italians. Italian-Americans have a strong Catholic tradition so the streets are adorned with Christmas deco-rations beginning in early winter. !ese decorations de"nitely add to the touristy atmosphere of the area. Regardless, the plethora of traditional foods in the neigh-borhood is authentically Italian. !e people stand in huge lines outside of shops for cannolis, prosciutto, co#ee, spices, and other treats. In addition to great food, Little Italy is home to the Italian American museum, which houses interesting exhibits year-round. Next time you are thinking of heading downtown, consider stopping by Mulberry street. Little Italy is de"nitely a place worth visiting.

Little ItalyIsaac Grafstein