The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp....

-

Upload

abuabdur-razzaqal-misri -

Category

Documents

-

view

218 -

download

0

Transcript of The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp....

-

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

1/26

Society of Systematic iologists

The Limits of CladismAuthor(s): David L. HullSource: Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd.for the Society of Systematic BiologistsStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2412558.

Accessed: 21/07/2014 17:05

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at.http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Taylor & Francis, Ltd.and Society of Systematic Biologistsare collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Systematic Zoology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll bj JSTOR T d C di i

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=taylorfrancishttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ssbiolhttp://www.jstor.org/stable/2412558?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/stable/2412558?origin=JSTOR-pdfhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ssbiolhttp://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=taylorfrancis -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

2/26

THE LIMITS OF CLADISM

DAVID L. HULL

Abstract

Hull, David L. (Department of Philosophy,University f Wisconsin, Milwaukee, Wisconsin

53201) 1979. The Limits of Cladism. Syst.

Zool. 28:416-440.-The goal

of cladistic

systematics

is to discern sister-grouprelations (cladistic relations) by

the

methods

of

cladistic analysis

and to represent

them

explicitly

and

unambiguously

in

cladograms

and

cladistic classifica-

tions. Cladists have selected

cladistic relations to

represent

for wo

reasons: cladistic relations

can be

discerned with reasonable

certainty y

the methods

of

cladistic

analysis

and

theycan

be represented

with

relative

ease

in

cladograms

and classifications. Cladists

argue

thatfea-

tures

of

phylogeny

other than cladistic relations cannot

be

discerned

with

sufficient ertainty

to warrant ttempting o represent

them

in

either

cladograms

or

classifications

and

could

not

be

represented

if

they

could.

I

argue

that

a

better alternative

is

to work

toward

improving

methods of cladistic analysis (or else

to supplement

them with

other methods) so thatsuch

features ofphylogeny

can be discerned

and to devise methods of

representation capable

of

representing them

in

both

cladograms

and classifications. However, cladograms and classi-

fications cannot represent everything

bout

phylogeny.

It is

better

to

represent

one or two

aspects of phylogeny explicitly and unambiguously than nothing at all. [Cladism; classifica-

tion; evolution; species.]

Our classifications

will come

to

be,

as far

s

they

can be

so made, genealogies;

and will then truly

give what

may

be

called the plan

of creation.The

rules for

classifying

will no doubt

become sim-

pler when

we

have a definite object

in view

(Darwin,

1859:486).

Charles

Naudin's

simile of tree and classifica-

tion

is like mine (and others), but

he cannot,

I

think,have reflectedmuch on the subject, oth-

erwise

he would

see that genealogy by

itself

does not give

classification (Darwin,

1899,

2:42).

One

possible

goal

forbiological

clas-

sification

s

to represent

hylogeny,

o

construct

lassifications

o

that

certain

features

f

phylogeny

an be

read off

n-

equivocally.

However,

Darwin was quite

correctwhen he noted thatgenealogy byitself does not give classification.Differ-

ent

taxonomists

may

select

different s-

pects

of

phylogeny

to

represent.

One

mightchoose

order of branching,

nother

degree

of divergence,

another amount

of

diversity,

nd

so on. Whether or not

the

rules

for classifying

become simpler,

as

Darwin

hoped they

would,

depends on

the features

of phylogeny

which

the tax-

onomist

chooses

to

represent

nd the par-

-ticular

et

of

principles

which

he

formu-

lates to represent them. A classification

which

attempts

o

represent

only

one

as

pect of

phylogeny

s

likely

to be

simpler

than one

which attempts

o

represent

two

simultaneously.

Given any particular

goal,

the simplicity

of the rules

capable

of accomplishing

this goal depends

both

on the

inherent

limitations

of

the

mode

of representation

nd the ingenuity

of

the

taxonomist.For example, the traditional

Linnaean

hierarchy

might

lend itself

to

representing

certain

features

of phylog-

eny

more readily

than

others,

but nothing

precludes

a

taxonomist

from

ntroducing

additional

representational

devices to

re-

move these

limitations.

The end

result

s,

of course,

more

complex

rules for

classi-

fying.

Systematists

are thus

forced

to

strike

balance

between

how much

they

wish

to

represent

and

how complicated

they are willing to make their principles

of classification

and

resulting

classifica-

tions.

In recent

years a

school

of taxonomy

has arisen

whose members

have serious-

ly

taken up

the challenge

of

attempting

to

represent

explicitly

and

unambiguous-

ly

something about

phylogeny.

The

school

is

cladism,

the

aspect

of phyloge-

ny which

the cladists

have chosen

to rep-

resent

is order

of

branching.

The cladists

have given two reasons forchoosing this

416

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

3/26

1979

LIMITS OF

CLADISM

417

particular

eature

f

evolutionary

evel-

opment

o

represent. irst,

he

Linnaean

hierarchy, s a list of indentednames,

lends itselfmorenaturally o

expressing

discontinuous

han continuous

henom-

ena. Whether r not evolution s gradual

or saltative, hylogeny

s

largely matter

of plitting

nd

divergence.

A

hierachy

f

discrete axa names s

well-calculated o

represent uccessive plitting.t is not s

well-calculated

o

represent arying

e-

grees of divergence. econd, the

cladists

argue that

rderof

branching

an

be

as-

certained

with ufficient

ertaintyo war-

rant he nclusion f such information

n

a

classification

while

other aspects of

phylogeny annot e. The methodwhich

cladistshave

devised

to

discover rder

f

branching

s

cladistic

nalysis.

Cladists

argue that, y and large, ll

a

systematist

as

to

go

on is

the

traits f

the

specimens before him, whether

these

specimens represent

extant

or extinct

forms.

y studying

is

specimens, e

can

discover ested ets

of haracters.

nique

derived

characters istinguish mono-

phyletic roupfrom ts nearest

elatives;

sharedderivedcharacters ombine hese

monophyletic roups ntomore nclusive

monophyleticroups.

n

this

way

the

sys-

tematist

an ascertainnested sets ofsis-

ter-groups. his method, o cladists ar-

gue,

cannotbe used

to discern variety

of

other

elations-speciation

without he

appearance

of at

least one unique

de-

rived character, reticulate evolution,

multiple speciations, nd the

ancestor-

descendant relation-nor

can

any

other

method.

Several questions rise at

this

uncture.

If

the

Linnaean hierarchy annotrepre-

sent

certainfeatures

fevolutionary

e-

velopmentverywell,

is

not that

limi-

tation f

he Linnaean

hierarchy?nstead

of

refusing

o

represent

what

particular

system

f

representation

as

difficulty

n

representing, better lternative

might

be

to

abandon

or

improve

hat

ystem

f

representation.

his is

one avenue

which

the cladists hemselves ave taken Grif-

fiths, 976; Hennig,1966; L0vtrup, 973;

Nelson, 1972a,

1973c;

Patterson nd Ro-

sen,

1977;

Wiley,1979).

Do

the evolu-

tionary

henomena

which

cladistic

nal-

ysis

cannot

discern

actuallyexist?

As

I

understand

volution and

evolutionary

theory,

wo

of

these

phenomena

learly

occur (ancestorsgivingrise to descen-

dants and

reticulate

evolution),

one

is

quite

ikely

multiple

peciation),

nd the

fourth

s

doubtful

speciation

without

e-

viation,

although

the

unique

derived

character

may

be

all but

undetectable).

s

not

the

inability f cladistic

analysisto

discern

the

preceding

phenomena,

as-

suming

they

take

place,

a

limitation

f

the

methods f

cladistic

nalysis?

nstead

of

declining

o

deal with such

phenom-

ena because the methods of cladistic

analysis cannot

discern

them,

perhaps a

better

trategy

ight e

to

attempt

o

m-

prove

upon

the

methods f

ladistic

nal-

ysis

or

to

supplement hem

with

other

methods.

The

crucial

question with

re-

spect to

cladism,

as

I

see

it,

is

what is

cladistic

nalysis?

What re

its

imits? s

cladistic

nalysis

one

way

of

scertaining

phylogeny,

he

only

way of

ascertaining

phylogeny,

he

only

way

of

obtaining

knowledge fanyphenomena?

One fact

bout

cladism

which

compli-

cates

attempts o

answer

the

preceding

questions

s that

ladism,

ike all

scien-

tific

movements,

s

neither

mmutable

nor

monolithic. t

any one

time,

ladists

can be

found

isagreeing

with

ach other

about

particular

rinciples

and

conclu-

sions.

In

addition,

f

one

traces

the

de-

velopment

f

cladism

hrough

ime,

rom

its

inception

in

the

works

of

Hennig

(1950), through ts introductiono En-

glish-speaking

systematists

Hennig,

1965,

1966;

Brundin,

1966;

Nelson,

1971a,

1971b,

1972a,

1972b,

1973a,

1973b,

1973c,

1974)

to

the

latest

publi-

cations

of

present-day

ladists,

signifi-

cant

changescan be

discerned.

he

most

significant

hange whichhas

taken

place

in

cladism

is

a

transition

rom

pecies

being

primary

o

characters

being

pri-

mary.

or

Hennig

1966,

1975)

and

Brain-

din (1972a), the basic unitsof cladistic

analysis

are

species, characterized

y

at

least

one

unique

derived

haracter.

ow,

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

4/26

418

SYSTEMATIC

ZOOLOGY

VOL.

28

for a growing

number

of cladists, any

monophyletic roup whichcan be char-

acterizedby appropriate

raits

an func-

tion in cladistic analysis,

regardlessof

whether

hat

group

s

more nclusive or

less inclusive than traditionally-defined

species. Cladistic classifications

o not

represent heorder fbranching

f ister-

groups,but the order of emergence of

unique derived characters,

whether or

not the development f

these characters

happens to coincide with speciation

events.

t

is

not

the

emergenceof

new

species which

s

primary

ut

the

emer-

gence

of new traits

Tattersall

nd

El-

dredge, 1977:207; Rosen,

1978:176).

In

general, ladists seem to be moving o-

ward the

position

hat he

particulars

f

evolutionary evelopment

re not rele-

vant o cladism.

t

does notmatter heth-

er

speciation

s

sympatric

r

allopatric,

saltativeor gradual,Darwinian or La-

marckian,ust

so

long

as

it

occurs

nd

is

predominantlyivergentCracraft,

974;

Bonde, 1975; Rosen, 1978;

andforthcom-

ing works by Nelson and

Platnick,El-

dredge

and

Cracraft,

nd

others).

The writingsof most cladists have

been

concernedwith

developing

meth-

ods

of

ascertaining

he

cladistic elations

between

biological axa,

ut

Platnick

nd

Cameron

1977)

have shown thatthese

same techniques

can

be

used

to

discern

the cladistic relations xhibitedby

lan-

guages

and

texts see

also

Kruskal, yen,

and

Black, 1971; Haigh,

1971; and Nita,

1971).

n

general

ladistic nalysis an be

used to

discover

the cladistic relations

between any entitieswhichchange by

means of modification

hrough escent

(Platnick, 979).

As

general

s thisnotion

of

cladisticanalysis s,

it still

retains

necessary emporal imension.

ransfor-

mation series must be established

for

characters,

ot

ust

an

abstract

temporal

transformation

eries like the cardinal

numbers r the

periodic

table, but

a se-

ries of ctualtransformations

n

time.For

example,

the vast

majority

f

matter

n

theuniversehappens tobe hydrogen.n

isolated pockets of the universe,more

complex

molecules have

developed,

but

theyhave not developed by

progressing

up

the periodic table, from

ydrogen o

helium, ithium,

eryllium, tc.

From the

beginning,Gareth Nelson

(1973c) seems to have been

developing

twonotions f cladistic nalysis imulta-

neously, one limited to

historically e-

veloped patterns

cladismwith a small

'c'),

the

other more

generalnotion p-

plicable to all

patternsCladism with a

big C'). His

method f

component nal-

ysis

is

a generalcalculus for

discerning

and

representing

atterns

f

ll sorts. or

example,

n a

recent

discussion,Nelson

(1979:28) states that

cladogram

s

an

atemporal

oncept

...

a

synapomorphy

scheme. It remains o be seen whether

all

of

the terms f cladistic

nalysisfrom

sister

group to

synapomorphy can

be

defined o that

none of them neces-

sarily resupposes

temporal imension.

Although think

hat the principlesof

cladistic

nalysis

an

be

extended

o any

system

which

genuinelyevolves (i.e.,

changes through

ime

by means of

mod-

ification hrough

descent), I

will limit

myself n this

paper to phylogeny nd

biological evolution. also will not ad-

dress

myself

o

Nelson's

more general

notion.

Attemptingo discussthe princi-

ples of cladistic

nalysis s

they pply to

phylogeny s a

sufficiently

ifficultask

without

ttempting

o

present nterpre-

tations f

these

principleswhich re also

consistent

with

Nelson's more

general

program.

METHODOLOGICAL

PRINCIPLES

AND

OBJECTIONS

In

spite

of

certain bservations

which

cladists

have made

periodically

boutthe

evolutionary rocess,

the

principles

of

cladistic

analysis

do not concern

evolu-

tion

but the

goals

of

biological

classifi-

cation

nd the means

by

which

they

an

be realized.

These

principles

re

primar-

ily

methodological.

s

I

see

it,

the

goal

of cladism

s to

represent

ladistic

rela-

tions

in

both

cladograms

nd classifica-

tions s explicitlynd unambiguouslys

possible. Thus,

cladistic

methodology

has two

parts:

ules for

iscerning

ladis-

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

5/26

1979

LIMITS OF CLADISM

419

tic

relations nd

rules for

representing

them

in cladograms nd

classifications.

For example,

Nelson raises

two objec-

tions o the

ancestor-descendant

elation:

first,

ancestral

pecies cannot

be iden-

tified s such in thefossilrecord Nel-

son,

1973b:311),

and

second,

they

are

also

inexpressible

in

classifications

(Nelson,

1972a:227).

One sourceof

the confusion

whichhas

accompanied the

controversyver clad-

ism is the

interpretationf

their meth-

odological

principles

s

empirical

eliefs

aboutevolution. he claim that

dichoto-

mous

speciationneveroccurs

s an em-

pirical

claim to be

tested by

empirical

means.The claim thatwe can neverdis-

tinguish

between dichotomous

pecia-

tion events and

more complex

sorts of

speciation is a

methodological claim

about

the limitsof our

methodsof

sci-

entific

nvestigation.

inally,

the

claim

thatmultiple

peciation,

f

t

occurs and

if it can be

discerned,

annotbe

repre-

sented

unambiguously

in

cladograms

and/or

lassifications

s

a comment

bout

the

limitationsf

these modes of repre-

sentation. nce theprinciples fcladism

are

recognizedforwhat

they re,

meth-

odologicalprinciples,

he

ogic

of

he cla-

distic positionon

a

variety

f ssues

be-

comes

much

clearer.

Scientists re interested

n

truth,

ot

Absolute

Truth,

but truth

nevertheless.

Although

hilosophershave

yet to pro-

duce

a

totally

nproblematic

nalysis

of

science as

the

pursuit

of truth

see, for

example,Laudan,

1977),

think

hat

ci-

entists re correct n the focus of their

attention.

cientists also

present

argu-

mentsto buttress

heir mpirical

laims

and

try

o make their

rguments

s

good

as

possible.

Unfortunately,

cientists

re

rarely ble to

present

heir rguments

n

the

unproblematic

orms hus

far ana-

lyzed

successfully by

mathematicians

and

logicians.

The

reasoning

which

goes

into the

formulationnd

testing f sci-

entific

heories

s a

good

deal more

om-

plex and informal hanany explicitra-

tional

reconstructionas

yet

been

able to

capture.

cientists

re

interested

n

both

truthnd

cogencyof argument,

ut they

are a

good deal more

nterested

n

truth

than

n

cogency fargument.f

a line of

reasoningwhich

ed to a

particular on-

clusion turns out

to be

somewhat ess

thanperfect,treallydoes notmatter ll

that

much, ust so long

as the

conclusion

depicts

reality

with

greater

idelity

han

previous

ttempts.

Scientists ave

limited

patience when

it

comes to discussing

rguments. hat

patience s even more

imitedwhen the

argumentsre

methodological. s

strange

as

it

may sound

coming

from

philoso-

pher,

am

highly ceptical of

methodo-

logical principles

nd

prescriptions,

s-

peciallywhenthey represented n the

midst

fscientific

isputes.They tendto

be

suspiciously

elf-serving,esigned

to

put one's opponentsat a

disadvantage

while

shoring p

one's

own

position.

n-

variably the advocates of a

particular

methodology an know

what

they

need

to

knowwhile their

pponents an never

hope

to know what

theyneed

to know.

For example,

hepheneticists

laim that

we can

analyze

traits

nto

unit

haracters,

butwe can neverhope to establishgen-

uine,

evolutionary

ransformationeries

among

haracters. one too

surprisingly,

the

pheneticists

eed toknow

he former

but

not the

latter.

Only

the

cladists and

evolutionists

eed

to know

the unknow-

able.

Similarly,

he cladists

laim

that

we

can establish

transformation

eries with

sufficient

ertainty

o warrant he role

which

they

play

in

cladistic

ystematics

but that

ancestor-descendant

elations

are unknowable.As luck would have it,

cladistsneed to

knowthe former ut not

the

atter. nly the

evolutionists eed to

knowthe

unknowable.

As

cynical as the

precedingremarks

may

ound,

think

heyhave some valid-

ity.

t is

no

accident that ll

four f the

phenomenawhich

he cladists laim can-

not be

known,

annotbe

discerned by

the traditional

eans

ofcladistic

nalysis

and

cause

problems

for he

explicit

nd

unambiguous representation f sister-

group relations

n

both

cladograms nd

classifications.

t is

also

no

accidentthat

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

6/26

420

SYSTEMATIC

ZOOLOGY VOL. 28

one of the

phenomena

which cladists

claim cannot

be

known

(the

ancestor-de-

scendant relation) plays

a central

role

in

the research program of their chief

ri-

vals-the evolutionists. I do not mean

to

imply that the preceding remarks apply

uniquely to the

cladists. They apply to

scientists

n

general.

If

I

were

investigat-

ing the pheneticists or the

evolutionists,

comparable

observations would

apply

as

readily to them. These are the sorts of

games

which scientists

(not

to mention

philosophers)

play with each other.

In

general,

I think

t

is

very bad strat-

egy

for

proponents

of a

particularscien-

tific research program to stake their fu-

ture on epistemological considerations,

especially

on

our

inability

to

know some-

thing. Phenomena

which

scientists

in

one

age

claim

can

never

be

known often

become common

knowledge

at a

later

date.

The

history

of science

is

littered

with

the bodies

of

scientists who

staked

the success of their movements on

what

we can never know.

I

agree

with

Einstein

(1949:684),

who,

in

response to philo-

sophical criticismsof his

work, stated:

Science without

epistemology

is-insofar as it

is

thinkable

at

all-primitive

and

muddled.

How-

ever,

no

sooner has the

epistemologist,

who

is

seeking

a clear

system, fought

his

way

through

to

such

a

system,

han

he

is

inclined to

interpret

the

thought-content

f science

in

the sense

of his

system

and

to

reject

whatever does not fit

nto

his

system.

The

scientist,however,

cannot afford

to

carry

his

striving

for

epistemological system-

atic that far.

I

hardly want

to argue against

meth-

odological rigor n science, but I also do

not want to see scientificprogress

sacri-

ficed to

it.

Invariably methodological rig-

or is a

retrospective

exercise, carried on

long after

ll

the

Nobel prizes have been

won.

From the

point of view of current

methodologies, scientists will, as

Ein-

stein

(1949:684) noted, appear to

the

systematic epistemologist as a type

of

unscrupulous opportunist. Instead

of

cladists

insisting

that

certain aspects of

phylogeny can never be known and

could

not be

represented cladistically

if

they could be known,

wiser strategy

would be

to

attempt

o devise methods f

analysiscapable

of discerning hese fea-

tures of evolutionary

evelopment

nd

representational

echniquessufficiento

representhem. n thispaper, have at-

tempted o

produce an internal riticism

of

cladism;

that

s,

I have

accepted

the

goals

of cladism

and

have

set

myself

he

task of decidingwhich

methodological

principles

re central

o the

undertaking,

which

peripheral,

nd which could

be

modified

r abandoned without oss

and

possibly

with

ome

gain.

CLADOGRAMS,

PHYLOGENETIC TREES,

AND EVOLUTIONARY SCENARIOS

A curious featureof scientific

evel-

opment

s

the

frequency

with

which a

new movement

s named

by its oppo-

nents. ocial

Darwinists o morewanted

to be called

Social

Darwinists han

clad-

ists have

wanted to be called cladists.

Twentyyears

ago, JulianHuxley 1958)

coined

the terms

clade

and

grade

to

distinguish

etweengroups

f

organisms

with common enetic rigin

nd

groups

distinguished y differentevels of or-

ganization.

Later Mayr (1965:81)

and

Camin and

Sokal

(1965:312)

introduced

the term

cladogram o refer o

a

dia-

gram depicting

the

branching

of the

phylogenetic

reewithout espect

o rates

of

divergence Mayr,

1978:85). Finally,

Mayr 1969:70)

invented he term clad-

ism as a substitute or phylogenetic

ys-

tematics, he name preferred

y Hennig

and

his

followers.

Gradually

he cladists

themselves ave cometo use theterm o

refer o

themselves, lbeit

grudgingly.

Whether

he

Hennigian

school

of

sys-

tematics

s

called

phylogenetic

r cla-

distic

s

not

very mportant,

ut the

pre-

cise nature

f

cladograms

s

they

unction

in

cladistic

nalysis

s.

In

fact,

ncertain-

ty ver

what

t s

that ladograms

re

sup-

posed

to

depict

and how

they

are

sup-

posed

to depict

it

has been

the

chief

source

of confusion

n

the

controversy

overcladism.Like all terms,hemeaning

of

cladogram

has

changed

through

he

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

7/26

1979

LIMITS OF

CLADISM

421

years.

t

no longermeansto cladistswhat

Mayr,

Camin

and

Sokal

proposed. The

meanings

of cladism and

cladistic

analysis

have

changed

accordingly.

n

an

attempt o

reduce the

confusion verthe meaning of cladogram, cladists

have introduced he

distinction

etween

cladograms,

hylogeneticrees,

nd evo-

lutionarycenarios.'

Once again,

he par-

ticular erms

sed tomark hese

distinc-

tions are

not important;he

distinctions

themselves

re.

It

is

also truethat the

cladists

have devised

these distinctions

for

their

own

purposes. Others

might

want o

draw

ther

istinctions

rto draw

these distinctions

differently.

n

anycase, all three ppellationsrefer o rep-

resentations,ot o the

phenomena

eing

represented. Cladogram nd

tree re-

fer

o two

sorts

f

diagrams, hile scen-

ario refersto a

historical narrative

couched

n

ordinary iological

anguage.

Phylogenetic rees

re designedto de-

pict

phylogenetic evelopment,

ndicat-

ing which

taxa are extinct, hich

extant,

which

gave

rise to

which,degrees

of

di-

vergence, nd so on. As

diagrams

hey

do

not include discussions ofthe methods

used to construct

hem,

he natural

ro-

cesses which

produced

the

phenomena

theydepict,

nd

a

variety

f

other onsid-

erations

f

equal importance.

tree

s a

diagram,

ot an

entire

axonomicmono-

graph.

All

sorts f

conventions ave been

devised to

represent hylogeny

n a dia-

grammatic

orm; or xample,

ines

usu-

ally represent

ineages,

forks

epresent

speciation

vents,

he

slant nd

length

f

a line reflect herapiditywithwhichdi-

vergence ookplace, and

the termination

of line

indicates xtinction.

ther

ech-

niques of

representation ave

also been

used on

occasion; for xample,

dots

in-

dicating uestionable

connections,

ines

of

varying

hicknesses

eflecting

elative

1

The

distinction

between

cladograms,trees,

and

scenarios

discussed

in

Tattersall

nd

Eldredge

(1977)

was takenfrom manuscriptbyGarethNelson. See

Mayr

(1978)

for early

definitionsof

such

terms as

i'cladogram

.

phenogram, and

phylogram.

numbers

of

organisms,

and so

on. How-

ever,

as a

diagram

in

two-dimensional

space, a

tree can

include

only

so much

information

efore

a point of

diminishing

returns ets in. Eventually attempts o in-

clude additional

sorts of

information

e-

sult in

the

loss

of

nformation. f

trees are

supposed to

be

systems of

information

storage

and

retrieval, the

information

must be

retrievable.

Scenarios, as

cladists

use the

term,

re

not

diagrams.

They

are

historical

narra-

tives

which

attemptto

describe not

only

which

groups

gave

rise

to

which

(the

sort

of

information

contained

in

trees)

but

also the ecological changes and evolu-

tionary

forces

which

actually

produced

the

adaptations

which

characterize the

organisms

discussed.

Romer's

(1955:57)

story of the role which

the

drying up

of

ponds and streams

played

in

the

transi-

tion

from the

crossopterygians

to early

amphibians is

by now

a

classic

example

of an

evolutionary

scenario.

Because

scenarios

are

presented

in

ordinary

an-

guage-supplemented

with a host

of

technical biological terms-the phenom-ena which scenarios can

describe are

lim-

ited

only by

the

limitations

of

language.

Hennig's early

cladograms

(Hennig,

1950:103;

1966:59, 71)

give every

ap-

pearance

of

being

highly stylized

trees.

The

circles

arrayed along

the top of

the

diagram

apparently

represent extant

species,

while

those

at

the

nodes

repre-

sent

extinct, ommon

ancestors

(see

Fig.

la).

At

one

stage

in

the

development

of

the cladogram, Nelson (1972b, 1973b) ar-

gued that the

circles at

the

nodes

did

not

represent

real common

ancestors

but

hypothetical

ancestors.

The

term is

problematic.

All

taxa that

ever

existed

are

equally

real.

Only

our

ability

to

discern

them varies.

We

can

usually discern

ex-

tant

species with

greater

certainty

than

extinct

forms,

but the

postulation of

any

taxon,

whether

extant or

extinct,

nvolves

highly

complex

inferences and

requires

evidence

which is

frequently quite dif-ficult to obtain.

(Recall

the

objections

which

pheneticists

raised to

the

biologi-

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

8/26

422

SYSTEMATIC

ZOOLOGY

VOL. 28

A

B C

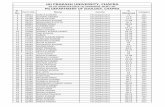

FIG.

1.-The

evolution of the cladogram. (a) A

cladogram

in

which the darkened circles

at the ter-

mini represent

extant

species,

while those at the

nodes represent

ommon

ancestors. b) A cladogram

in which

the darkened circles at the

termini rep-

resent species,

both extantand extinct,

while the

circles at the nodes represent hypothetical

com-

mon ancestors,

i.e., morphotypes. c)

A cladogram

in which the darkened

circles at the termini rep-

resent species, both extant

and extinct,while the

nodes represent

speciation events

and/or

he emer-

gence of unique derived

characters.

cal

species

concept

even when

it is

ap-

plied to extant

forms.)

f

extinctforms

re

hypothetical

because

of their inferen-

tial basis, then so

are extant

forms.The

difference

between

extant

and

extinct

species

is

not between observation

and

inference, but between

inferences of

varying degrees of

certainty.

Another

nterpretation f hypothetical

ancestor

is that he

circles

which

appear

at the nodes of cladograms are not sup-

posed

to

be taxa

at

all

but

morpho-

types,

rational constructs characterized

by

the

defining

traitsof the taxa

listed at

the termini

of the

cladogram

and

no

oth-

ers.

As Platnick

1977c:356)

observes,

the

nodes

of cladograms

representonly

in-

ferred

species (or,

more accurately, only

minimum sets of synapomorphic

charac-

ters).

In this sense, hypothetical

ances-

tors are

hypothetical,

but they are not

ancestors. They are not even taxa (see

Fig. lb).

In

present-day

cladograms,

all

taxa,

whether

extinct or extant, appear

along

the top

of the

cladogram.

Clado-

grams

would

be much

less

misleading

if

they

included nothing

at the nodes (see

Fig. ic).

If

the nodes

in

a cladogram

do

not rep-

resent real taxa

(ancestral

or

otherwise),

what do the

lines and

forks

n

cladograms

represent?

Two answers

have been

given

to this question, which may or may not

'be reducible

to the

same

answer.

A fork

in

a cladogram can

representeither

a

spe-

ciation vent

the splittingfone

species

intotwo),

or the emergence f an

evolu-

tionary

ovelty a unique derived

char-

acter),

or both.

If

the

emergence

of a

unique derived character

ccurs

always

and onlyat speciation, hen the twoan-

swers lways oincide.

f

not,not. imilar

observations

old for he term cladistic

relation.

t

can refer

o order f splitting

of taxa,

or to order fappearance

of evo-

lutionaryovelties, r

both.The decision

hinges

on how operational

ne wishes

to

make cladistic nalysis.Since

specia-

tion events

re inferred y

means

of

the

appearance

of evolutionary

novelties,

one

inferential

tep

can be eliminated

y

talking nly bouttheemergence fevo-

lutionarynovelties

and not speciation

events.

CERTAINTY

AND LEGITIMATE DOUBT

One reason

for he

cladists' ntroducing

the

distinction between

cladograms,

trees, and

scenarios

was

to clarify

he

technical

ense

in

which heywere

using

the term

cladogram.

Too manypeople

were misinterpretingladograms

s bi-

zarre, ighly tylized rees.A secondrea-

son was

to establish

he

ogical

and

epis-

temological

priority

f

cladograms

ver

trees nd

of reesover

cenarios.

As clad-

ists define

hese terms, n inclusion

re-

lation

xists etweenthem.

cenarios

n-

clide

all

the information

ontained

in

trees,

and more besides. Trees

include

all

the

nformationontained

ladograms,

and more

besides.

Thus, any knowledge

required

for

cladogram

s

required

for

a tree, nd anyknowledge equiredfor

tree

is

required

for

scenario,

but not

vice versa.

Thus,

cladograms

re more

certain

han

rees,

nd treesmore ertain

than

scenarios.

As harmless

s the dis-

tinction

etween cladograms, rees,

nd

scenariosmay

seem on

the

surface,

t

re-

sults

n

cladistic

nalysisbeing

in

some

sense

basic

to

all

evolutionary

tudies.

The relations

et outabove do

obtain

between

cladograms,

rees,

and scenar-

ios-as the cladists definethese terms.

That is one reason why non-cladists

might refer

therdefinitions. ut even

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

9/26

1979

LIMITS OF

CLADISM

423

if

one were to accept the cladists'

defi-

nitions, ertain onclusionswhich

clad-

istshave claimedfollow rom he

preced-

ing ine ofreasoning o not.For

example,

in claiming hat trees should always

be

based on cladograms nd that cenarios

should follow rom rees,

Tattersall nd

Eldredge (1977:205)

are confusing ogi-

cal and

epistemological

rder

with tem-

poral order.The

conclusion

to

an argu-

ment

follows ogically

rom

ts

premises.

That does not mean

that

people

must

think f the premisesfirst nd only

then

thinkof the conclusion.Sense

data are

epistemologically

rior

o

all

knowledge,

but that

does

not mean

that

scientists

should beginevery cientifictudywith

an

extensive

nvestigation

f their own

sense data.

f scientists ad actually ro-

ceeded

in

this

fashion,

we would

still

be

awaiting Ptolemaic

astronomy, ot to

mention

elativityheory.

he

inferences

which

take

place

in

the

actual

course of

scientificnvestigations

re

very ntricate

and

frequently

feed

back

upon each oth-

er, as Tattersall nd Eldredge 1977:205)

note.

n

retrospect,

here s considerable

pointtounravelinghese nferencesnd

setting hem ut

n

some ogically

oher-

ent

fashion,

ut the insistence

hat

sci-

en-tists

must

always begin

at

the

begin-

ning and proceed step by step

according

to some sort f ogical or epistemological

order would

stop

science

dead

in its

tracks.2

Cladists

also

make

much

of

the

differ-

ences

in

certainty

etween

cladograms,

trees,

and

scenarios.

n

actual practice,

scientistswanderfromne level ofanal-

ysis to

another

n

the course of their

n-

vestigations.

As a result knowledge ac-

2The pheneticists

presented similar arguments

for the

epistemological

priority

f

phenetic

classi-

fications.

According to

the

pheneticists, the only

place at which systematists

an legitimately begin

is

phenetic characters nd

the construction f

pure-

ly phenetic

classifications. Once such

a phenetic

classification

is

erected,

then a systematistcould

put various interpretations on his classifications

and

possibly produce

one or more special pur-

pose

classifications; see e.g., Sneath

and Sokal

(1973).

quisition

s a

process of

both

reciprocal

illumination

Hennig,

1950;

Ross,

1974)

and

reciprocal

lundering.

etting

ne

element

right

elps

improve

ur

under-

standing fthe

other

lements, ut

errors

feed throughhe systemust as readily.

Although ladists

might

well

admit

that

knowledge

acquisition

in

general

is

a

process

of

reciprocal

llumination,

hey

also

tend

to be

so

sceptical

oftrees

and

scenariosthat

hey

see all

the

illumina-

tion

going in

a

single

direction-from

cladogramsto

trees and

scenarios. At

times

ladists eem

to

argue

hatnot

only

should

evolutionary

tudies

begin with

cladogramsbut

also

they should

end

there as well. Cladistic relations are

knowable;

verything

lse

about

phylog-

eny

s

unknowable.

For

example,

Platnick

1977d:439) ar-

gues

that

he

onlyway

that

hylogenetic

trees an

be tested

s

by the

same

means

used

to

test

cladograms,

by

evaluation

in

the

lightof

newly

discovered

harac-

ters.

Any

hree axa

can

be

ordered

nto

22

different

rees.

omeof

hese

rees an

be

rejected

by

discovering

ppropriate

characters,.e., the appropriate utapo-

morphies

and

synapomorphies.

Other

trees

can

be

rejected

only by

claiming

that

no

autapomorphies

xistfor

he rel-

evant

taxa.

Since

the most hat

system-

atist

an

legitimately

laim

s that

he has

yet

to

detect uch

autapomorphies,

e is

not

ustified n

rejecting

hese

trees.Plat-

nick

1977d:440) concludes

that

phylo-

genetic

rees

re

not estable

y character

distributionsnd

thus hat

cientific

hy-

logenyreconstructions not possible at

the evel

of

phylogenetic

rees nd must

be

restrictedo

the evel of

cladograms.

But

the

same

sort

f

rgumentan be

pre-

sented

against

he

cladists.

They

do

not

need

to

know

ancestor-descendantela-

tions,

ut

they

do

need

to establish

rans-

formation

eries nd

to

determine he

po-

larity

f

these

series.

They do

need to

individuate

haracters nd

decide which

are

autapomorphic,

ynapomorphic,

tc.

For instance, synapomorphies an be

used to

test

cladograms

f

they re

syn-

apomorphies,

ut

no one

has

yetto

sug-

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

10/26

424 SYSTEMATIC ZOOLOGY VOL. 28

gest any infallible means

for

deciding

whether

r

not a trait s

actually syn-

apomorphy.

he same can

be said

for

such relations s

thepolarity

f transfor-

mation

eries. In fact,

Tattersall

nd El-

dredge 1977:206)state, In practice t s

hard, even

impossible, to

marshal a

strong,ogical

argument or

given

po-

larity

formany

characters

n a given

group. The

sortof

argument

rom eg-

ative

evidence

which the

cladists

use

againstothers t

the evel of taxa

can be

used

againstthem

at the

level of

traits.

Of

course,

their

pponents

lso

must n-

dividuate nd

categorize raits.

hus, the

cladists'

position s

refuted t

only

one

level of analysis,while the positionof

their

opponents s

refuted t

two.

Put

more

directly, uch

arguments efute o

positions

whatsoever.

The

cladists

have weakened

the force

of

their

rguments

y

presenting

hem

n

a

needlessly dichotomous

ashion.The

only

thing

hat

hey

need to

know

o pro-

duce

cladograms

re cladistic

relations,

and

they re

knowable.Others

who wish

to produce

trees

need to

know much

more; e.g., ancestor-descendantrela-

tions,

the

existence of

multiple specia-

tion and

reticulate

volution, tc. These

phenomena re

totally

nknowable. he

cladists

need not

present

such an ex-

treme

and

suspiciously

elf-serving)o-

sition. Estimations

f

cladistic

relations

are

inferences

nd

as such

carrywith

them he

possibility ferror.

owever, t

is certainly

ruethat

everything

hich

the cladists

need to know

the

evolution-

istsalso need toknow,whiletheevolu-

tionists

need to

know more besides.

These additional

phenomena

lso

carry

with

them

certain

egree

of

uncertain-

ty.

Hence,

evolutionary lassifications

are

bound to be

moreuncertain

han

la-

distic

classifications. he

question re-

mains

whether

ll

evolutionary

henom-

ena

other han

cladisticrelations

re so

uncertain hat

o

attempt

houldbe made

to

include

informationbout

them n a

classification.n thesucceeding ections

of this

paper,

I

will

investigate

arious

phenomenawhich

cladists

rgue cannot

be

known or

at

least

cannot

be known

with

ufficient

ertainty)

o

see

why hey

are so

difficult

o discern. s it

that

hey

cannotbe

known, r

that

hey

annotbe

knownby

means of

cladistic

nalysis?

s

therenowaytoacquireknowledge f he

world

other than

by

cladistic

analysis?

The

pointof

his

ection s,

however, hat

the

difference

n

our

ability o ascertain

cladistic

elations nd

other

volutionary

phenomena s

one of

degree,not

kind.

Differences

r1

degree of

certainty re

neither

eryneat

nor

esthetically.

leas-

ing,but

theyare

the

most

thatcladists

can

justifiably

laim. What

they

ose

in

elegance

and

simplicity,

hey gain

in

plausibility.

Certain

ladists,

n

more

recent

publi-

cations,

eem

to be

moving

n

precisely

this

direction. For

example,

Eldredge

(1979:169)

states hat,

ontraryo

hisear-

lier

opinions:

I

no

longer

oppose the

construction

f

phyloge-

netic trees

outright,or

for

that

matter,

scenar-

ios (which

are,

after

ll,

the

most

fun),

but

mere-

ly point

out

that,

in

moving

through the

more

complex

levels,

we

inevitably

become further e-

moved from he original data base in adding as-

sumptions

and ad

hoc

(and

largely

untestable)

hypotheses.

As

long as we

understand

precisely

what

we are

doing

at each

step

in

the

analysis,

which includes

having

an

adequate

grasp

of the

probability

that

we are

wrong

and

of what the

assumptions are what we have

added

along

the

way,

there no

longer

seems to me

any

reason

for

anyone to

tell anyone

else what

notto

do.

Although hoseworkers

ngaged

n

the

production f

trees and

scenarios

might

differwith Eldredge on the situationbeingas extreme s he makes touttobe,

they oo

are aware

ofthe

difficulties.

or

example,

Lucchese

(1978:716)

concludes

a

paper on the

evolution

f sex

chromo-

somes

with

he

followingemarks:

...

for

n

individual

to

profess

n

insight

nto

the

biological

changes

that

have

occurred

through

time

remains

an

act of faith

of

considerable mag-

nitude.

[Yet,

within]

the

limitationsust

set forth,

the

purpose

of

this

article

has been

to

spin a rel-

ativelyreasonable evolutionarytale in the hope

of

expanding

the

current

perception of a

highly

significant

xample

of genetic

regulation

in eu-

karyotes.

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

11/26

1979

LIMITS

OF CLADISM

425

THE

PRINCIPLE

OF

DICHOTOMY

Few

principles

attributed

to cladistic

taxonomists

have caused

more

conster-

nation and

confusion

than the claim

that

all cladogramsand classificationsmust be

strictly

dichotomous.

When cladism

was

first

ntroduced

to English-speaking

sys-

tematists,

cladists

and anti-cladists

alike

agreed

that the principle

of

dichotomy

was

essential

to

the

philosophy

of

Hen-

nig and

Brundin

(Nelson,

1971a:373;

see

also

Darlington,

1970:3;

Mayr,

1974:

100;

Bonde,

1975:302;

Platnick,

1977d:438).

Although

Cracraft

1974:79)

agrees

that phylogenetic

classification

sensu Hennig and Brundin would appear

to require

the

assumption

of dichotomous

branching,

cladistic

classification

in

a

more

general

sense

does

not necessitate

dichotomous

branching,

and the exact

pattern

f branching

s determined

by

the

manner

in

which

shared

derived

charac-

ter-states

cluster

taxonomic

units. The

question

remains

why

the principle

of

dichotomy

has seemed

so central

to most

cladists

and continues

to seem

so to

some.

Although

no

cladist

has ever

main-

tained

that the

principle

of

dichotomy

s

an empirical

claim

about the

speciation

process,

few

cladists

have

been

able

to

resist the

temptation

to justify

t

by ref-

erence to empirical

considerations.

For

example,

Hennig (1966:210,

211) begins

by stating

hatdichotomy

s

primarily

no

more than

a methodological

principle

and then goes

on

to

add,

A

priori

it is

very improbable that a stem species ac-

tually

disintegrates

nto several

daughter

species

at once.

Cracraft

1974:79)

in-

terrupts

the

discussion quoted

above

with the

remark

that the

principle

of

di-

chotomy

can

be

justified

on

theoretical

grounds

not

associated

with classifica-

tion.

Bonde

(1975:302)

agrees.

Although

dichotomy

s

a

methodological

principle,

in nature

speciations

are probably

near-

ly

always

dichotomous.

Whether multiple speciation seems

possible

or

impossible

depends

on

the

unit

of

time one

selects to

define

simul-

taneous.

As

Hennig

(1966:211)

notes,

the

issue

of dichotomous

speciation

can

be trivialized

by defining

simulta-

neous

too

narrowly.

If

it

is defined

in

terms

of split

seconds,

then

multiple

spe-

ciation is impossible. Conversely, if si-

multaneous

is

defined

too

broadly,

everything

an be

made to occur

at

the

same

time.

The question

of

dichoto-

mous speciation

can

be

made significant

only

by

the specification

of a unit of

time

which

makes

sense

in

the context of

the

evolutionary

process.

In the absence

of

such

a unit,

the notion

of

simultaneity

can

be

expanded

or contracted

t will

and

the

issue

decided

by

fiat

see

Cracraft,

1974:74).

Whether

multiple speciation

as an em-

pirical

phenomenon

seems plausible

or

implausible

depends

on

the

model

(or

models)

of

speciation

which one

holds.

If

speciation

is viewed

as the

gradual

split-

ting

and

divergence

of

large

segments

of

a species,

as Hennig (1966:210)

main-

tains,

then

multiple

speciation

looks

less

likely

than

if it is

viewed

as

a

process

in

which

small,

peripheral

populations

be-

come isolated and develop into separate

species,

as

Wiley (1978:22)

supposes.

But, as

the cladists

have reminded

us

often

enough,

dichotomy

is

a

methodo-

logical

principle.

If

speciation

were

al-

ways

dichotomous,

this fact

about

evor

lution

would

certainly

lend support

to

dichotomy

s

a methodological

principle,

but

good

reasons might

exist

for

produc-

ing exclusively

dichotomous

cladograms

and

classifications

even

if

speciation

is

not always dichotomous.

Cladists

have

presented

two sorts

of

justification

for

their preference

for the

principle

of

dichotomy:

our inability

to

distinguish

dichotomous

speciation

from

more

complex

sorts

of speciation

and our

inability

to

represent

unequivocally

more

complex

sorts

of speciation

in

cladograms

and classifications.

If

one

limits

oneself

ust to

traditionally-defined

traits

e.g.,

presence

of

various sorts

of

appendages, dentitions,etc.) and if one

assumes

that these

traits have

been

ap-

propriately

individuated

and identified,

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -

8/10/2019 The Limits of Cladism- by David L. Hull Systematic Zoology, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 1979), pp. 416-440.

12/26

426

SYSTEMATIC ZOOLOGY

VOL.

28

then he argument hichthe

cladistsput

forth

s

reasonably traightforward.

f a

cladist

tarts ith

nytwo pecies

chosen

at random nd compares third

pecies

to them, wo ofthese species

will be cla-

disticallymore closely relatedto each

other

than

either

is

to the remaining

species.

If

the cladist continues o add

species to his study ne at a time,he will

produce a consistently dichotomous

cladogram

ntil

ne oftwothings ccurs:

either he happens upon

a

genuine

in-

stance of multiple peciation

or else he

is unable to resolve this complex situa-

tion nto he ppropriateequence

of uc-

cessive dichotomies.

ecause dichotomy

is the simplesthypothesis,t should al-

ways

be

preferred,

vidence

permitting.

But as the cladists see it, giventhe sort

of

data available to the

systematist

nd

the resolvingpower of his methods of

analysis, e

will

always

end

up

wherehe

begins-with

doubt

or

with

dichotomy.

Never is

a

systematistustified

n

con-

cluding

that

speciation

vent

s

genu-

inely trichotomous ecause he is never

justified

n

dismissing hepossibilityhat

an apparent richotomys really pair of

unresolveddichotomies.

If

the preceding

s a fair

haracteriza-

tion of the cladists'argument,

t has

two

weaknesses.

First,

he cladists re

selec-

tive

in

acknowledging ossible

sources

of error.After

ll,

a

systematist

annot

guarantee

hat trait

which

he considers

to be unique and derived actually is.

There

is

always the possibility

hathe

is

dividing singlegroup

nto woor ump-

ing two groups nto one. Ifa trichotomy

represents ither genuine richotomyr

two unresolveddichotomies, hen a

di-

chotomy

could

just

as

well

represent

either

genuinedichotomy,

lumped

ri-

chotomy,

r a

single ineage

dividedmis-

takenly nto

two. When

a

systematist

claims that

particular peciation

vent

is trichotomous,e maybe mistaken, ut

he

may

lso

be

mistaken

n

claiming

hat

it s dichotomous. uring heearly tages

of nvestigation,oubtsaboutthe actual

cladistic elationswhichcharacterize he

groups under study are legitimate.

Many

trichotomies re very likely to

be resolv-

able into

dichotomies

after

urther tudy,

many of the groups treated as

single may

have to be split

into two or

more groups,

and vice versa. However, as the groups

are studied

more exhaustively, the legit-

imacy of continued doubt decreases.

If

after xhaustive study,three

species con-

tinue to appear

to be related

trichoto-

mously, the claim

that they mightactual-

ly be related by a pair of dichotomies

begins to ring rather

hollow. Descartes

has shown where that sort of

mindless

scepticism

leads.

If

a

systematist

an be-

come

reasonably certain

that

he

has

cor-

rectly discerned a genuine dichotomy,

see no

reason why

he

cannot also

attain

that same

level of certainty

n the iden-

tification of

trichotomies-even

using

just the

traditional methods of cladistic

analysis.

But

systematists re not

limited

just to the study

of ordinary taxonomic

traits.There

is

no reason fornot

using the

methods of

cladistic analysis on other

sorts of evidence, e.g.,

the

data

of histor-

ical biogeography.

As Platnick and Nel-

son (1978: 10) remark:

Trichotomous

cladograms are of no signifi-

cance

as tests

or

as initial

hypotheses)

unless

the

cladograms

for

all available

test

groups

are

tri-

chotomous,

in

which case we

may

suspect

that

an event disconnected

an area

into

three smaller

areas

simultaneously. Testing

this

hypothesis by

biotic relationships

seems

impossible (because

we have no

way

of

distinguishing

those clado-

grams reflecting

ctual trichotomiesfrom those

reflecting

only our

failure

to

find the relevant

synapomorphies

that would

resolve

a dichoto-

mous cladogram),but it should be subject to in-

dependent testing by

data

from

historical

geolo-

gy,

which

can

either be

in

accordance

with such

a

synchronoustripartite

isconnection of

the

to-

tal area or not.

If

multiple

speciation can occur

in na-

ture and

if n

certain circumstances

t can

be

discerned,

then cladists would be

wise to devise

methods of

representing

multiple speciation

in

their cladograms

and

classifications.One theme

which the

cladists repeatedlyvoice is thatanything

represented

in

a

cladogram

and

classifi-

This content downloaded from 142.51.1.212 on Mon, 21 Jul 2014 17:05:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsphttp://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp -