The Laments of Mani

-

Upload

gareth-morgan -

Category

Documents

-

view

215 -

download

2

Transcript of The Laments of Mani

The Laments of ManiAuthor(s): Gareth MorganSource: Folklore, Vol. 84, No. 4 (Winter, 1973), pp. 265-298Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of Folklore Enterprises, Ltd.Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1259835 .

Accessed: 16/06/2014 07:20

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Folklore Enterprises, Ltd. and Taylor & Francis, Ltd. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve andextend access to Folklore.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FOLKLORE * VOLUME 84 ?

WINTER 1973

The Laments of Mani

by GARETH MORGAN

THE landscape of Mani and the character of its inhabitants have been described many times. From the seventeenth century on- wards, Western travellers have expressed their amazement at this embattled headland of the Balkans, and the ferocity of the Mani- otes has excited all degrees of astonishment. They have been admired for their pride, patriotism, and independence; and castigated for a range of vices that goes from morosity to cannibal- ism. More scholarly studies have been slow to appear. Even in Greece, there would seem to be few people who are at the same time far enough from the Maniotes to look at them dispassionately and dedicated enough to stay for long in the arduous conditions of their life.

The present essay has a very limited objective: to describe the folk-poetry of Mani, and to bring to the the attention of people who do not read Greek a rare phenomenon of folk-song. Societies in which one genre of folk-song has come to dominate the rest are not unknown elsewhere, but usually it is a dance-style, or a feast- style, that has taken the prime position. In Mani, it is the funeral- lament that has become the vehicle and summation of popular composition.

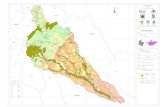

Mani (Maina, Magne) is the name given to the middle of the three southern headlands of the Peloponnese. Its seaward end is Cape Matapan: on the landward side its boundaries are less definite, but the line joining the northern coasts of the Gulf of Messenia and the Gulf of Laconia is a rough approximation. The great ridge of Taigetos runs like a spine down the thirty-five miles or so of the peninsula, dividing it into two parts-'Sunny' Mani (Prosiliaki) to the East, and 'Shady' Mani (Aposkiaderi) to the West. But this division is not as important as the distinction between Outer Mani (to the North) and Inner Mani (to the South).

Q 265

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

The dividing line crosses the principal saddle of Ta5getos, from Vitylo and Areopolis to Gythion.

Inner Mani is felt by its inhabitants to be the part of Greece which has best maintained its independence from foreign domin- ance, and therefore has the most direct connexion with antiquity. There is a certain amount of truth in this as far as freedom from Turkish rule is concerned, but Byzantine records and modern place-names suggest considerable Slavic settlement in the Middle Ages. There has also been immigration from other parts of Greece. The Nykliani, prominent in Maniote studies, preserve the memory of a movement from Nykli in the Central Peloponnese in the early thirteenth century. For all this, the southerners see themselves as the purer repository of tradition, and there is clear division of folk-song style between Inner and Outer Mani.

The internal distinction is small compared with the feeling that unites all Maniotes against outsiders. Mani is an island. If a man goes even to neighbouring Messenia as a hired workman for harvest or vintage, it is said that he is going 'to the Morii' (Pelo- ponnese). Only Maniotes speak Greek: the dialects of Messenia and Arcadia are contemptuously referred to as 'Vlachika'-the Romance tongue of the nomad shepherds of Greece.

The outstanding characteristic of the society of Mani is its preoccupation with death and the lamentation that goes with death.

When someone dies, the corpse is laid out by women from outside the family (if this possible), and dressed in holiday clothes. Candles are placed at head and foot, and flowers are scattered on the body-notably the scented herbs of the countryside, basil, marjoram, and mint. So far, these are usages common to most of Greece. It is in the afternoon and evening, when the friends and family assemble to lament the dead, that the customs of Mani begin to take their special form. As each mourner reaches the outer door of the house, he begins to repeat, over and over again, the word addrphi, a diminutive form of the words for 'brother' and 'sister'. This chant continues as the mourner passes through the courtyard and up the many steps to the room where the corpse is laid; for Mani is the place where families live in towers, and the biggest room is likely to be in the top storey, where there is less need of internal walls to bear weight. Each man and woman throws

266

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

onto the corpse a small bunch of flowers gathered on the way, and goes to drink a little wine, or the bean-soup that has been prepared by the women of the household to give strength for the ordeal that is to come. Through the night there is silence. Only with the first light of dawn does the lament itself begin.

The men stand silent around the walls of the room. The orna- ments of the house-pictures, photographs, curtains-have been brought in to deck the walls, but the windows are closed and shuttered, and the mirror and doorway are covered with black cloths. The women, through the night, have been gathering around the body. They sit cross-legged. At the sides of the corpse are the closest female members of the family, and the mourning-women (miroloyitres) who have been invited. The relations and mourning- women take off their shawls, unplait their hair, and divide it in two, left and right, holding it in their hands. As the lament goes on, they slowly pull down their hands alternately on each side of their head, stroking and swaying in time with the chant.

The most respected of the mourners, usually an old woman, rises to her knees and begins the lament. She may have been in- vited from another village, even one quite distant. Skilled mourners are famous throughout Mani, and the memory of some has been preserved a century and more.

The tune of the lament is a very primitive one that is found in various forms all over Greece. In its basic pattern it begins with a single note repeated a number of times, and has a range of a minor third, sometimes extended to a fourth. The last note is pro- longed, with a sudden upward swoop turning almost into a scream. The other women join in this cadence, and in the last few syllables of the line, if these are predictable. The Maniote lament is an improvised form, with a low proportion of formulaic structure, but Greek accidence, especially in its verb-patterns, allows a great deal of predictability at the ends of words, and makes possible this form of cooperative improvisation.

The same tune may be used for three quite different poetical forms. Since the most obvious distinction between them is metrical, we can call these three forms 'octosyllabic', 'mixed', and 'political', (i.e. fifteen-syllabled).

267

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

'POLITICAL' LAMENTS

The common metre of Greek folk-poetry is the 'political' fifteen-syllabled line. The accents fall predominantly on the even syllables, and always on the penultimate. There is a break between the first eight syllables and the last seven, and the lament-tune is used twice to each line of verse, with the upward swoop much more pronounced at the end of the line. Funeral laments of this pattern are known all over Greece, but in Mani they are considered to be characteristic only of Outer Mani, and especially of the north- western part bordering on Messenia.

The subjects are those of the common Greek funeral lament. First comes the Underworld, sometimes retaining its ancient name of Hades. Then Death himself, who is the old ferryman of Styx, Charon-but a Charon who has lost his former personality, and become more awesome and lordly. It is astonishing that these songs, associated in Mani with the depths of human sorrow, are sung in Crete as feast-songs, to tunes which, though still solemn and imposing in tone, are meant for the enjoyment of a family upon its great festivals, its weddings, and its baptisms.

[i]

Death planned to make an orchard. He dug it and prepared the ground, to plant trees in it. He plants young maids as lemon-trees, young men as cypresses, he planted little children as rose-trees all around, and put the old men too, as a hedge around his orchard.

[z]

You have been tricked, you are deceived, you go to the Underworld. And did you think the Underworld was like the world above? There are no shops, there are no coffee-houses, but the white become black, the rosy pale: faces blushing like the rose grow black and fill with cobwebs.

[3] So many good things that God made - but one he has not made: he does not make the ocean dry, or make a path in Hell, for the tombs to open and the dead to come out, for mother to see child for one day and for one night, - the day to be the first of May, and the night to last a year.

268

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

The desolation of bereavement is an obvious theme. In Outer Mani it is often particularised to the person who has died; there are laments for a son, a daughter, an old man, a child, and so on.

[4] Tombstone of gold, tombstone of silver, tombstone of gold refined. This maiden that we send to you is spoilt with our dear love. She wants her coffee in the dawn, and wine at the hour of noon, and at the setting of the sun she wants to bake and cook. She wants a new coverlet, she wants a thick soft bed, and a pillow full of down.

[5]sl Last night I had a dream, and in my sleep I dreamed: I was in a garden and among my herbs. I plucked the parsley and pulled up leeks and gathered the lovely carnations in my apron. The parsley is my tears, the leeks are my sorrow, and the lovely carnations are my bereavement.

Something of the high quality of these political laments comes through even in translation. Versions in other languages can usually keep the system of balances between one half of the line and the other, the triadic patterns that run through two consecutive lines ('coverlet-bed-pillow', 'parsley-leeks-carnations') and the minia- ture repetitions that can give an architectural structure even to poems of this size: but they cannot preserve the variations of rhythm in the first half of the line, or the sense of flow that comes from a language rich in elisions and other possibilities of rhythmic- ally alternative forms in common words.1 The Inner Maniotes acknowledge the quality of these laments, but tend to despise them as being practised and studied, in contrast to the momentary inspiration that they think proper to the intensity of their sorrow. At best, the political laments may be used as a prooemium to what they consider the true Maniote style, the lament in octosyllables.

1 For example, in narrative passages the aorist and present tenses are used interchangeably. So a plural verb in the third person, where a euphonic epsilon may be added, can have four forms, in three metrical varieties: e.g. 'they planted' might have the forms /wed'ovv, /#U7EOUVE, b'-regav, U-vr~bavE.

On a small scale, this metrical variation corresponds in function with the variation of Homeric noun + adjective patterns - the 'Homeric epithet'.

269

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

MIXED LAMENTS

The line of the Inner Maniote lament has eight syllables, with an accent on the sixth or the eighth (and occasionally both). In a large number of cases, where the line ends in a word of three or more syllables, an accent on the eighth implies a subsiduary accent on the sixth. It will be seen that this is a stricter version of the first half of a political verse.

Octosyllables such as these are used in Byzantine poetry, and it is arguable that as a popular form they preceded the political. In some of the earliest strata of Greek folk-poetry one comes across passages in which the sense is carried by the first half of the line, and the second appears as an extension or anticipation:

Now eat and drink, my noble lords and I a tale will tell to you about a young man that I saw was hunting and was coursing

hares

and I a tale will tell you, about a fine young warrior, who on the plain was hunting, with his handsome greyhounds.

There are also musical arguments, in which we may include the common lament tune that we have already described. It is used for both the long and the short metres, but more naturally for the short. It is tempting, therefore, especially when dealing with an obviously archaic backwater like Mani, to consider the octosyllabic lament as the earlier form. There is no certainty about this, and the octosyllable's comparative freedom from formulas, which are commonly regarded as a sign of long development in folk- poetry, may even suggest the opposite. The question is complicated by the existence of a mixed form, in which a prooemium in politicals is followed by a lament in octosyllables.

Until fairly recently, the mixed laments that we had came from a comparatively small area of the extreme north-west of Mani, around the village of Cardamili. Of these we have few examples. There are twenty-two in Pasayannis' collection, made in the decade or so before 1898, and three in Petrunias, who gathered his material in the first quarter of this century. One of his pieces is for the death of a Maniote colonel killed in the Asia Minor disaster in 1921. These laments have been neglected by modern scholars, and this is all the more regrettable, since they provide interesting materials for the study of the collision of two folk-song styles.

270

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

The prooemium may consist of a couplet, or as many as thirteen lines. The octosyllabic lament runs from two to twenty lines. There are three ways in which the components of this combina- tion differ from the original unmixed forms. The first concerns the degree of compatibility between the introduction and the lament.

The introduction in politicals may be a completely independent piece, which has no relation to what comes after, and may even conflict with it. A glaring example is the prooemium suitable for a child or a lover (it is used elsewhere as a love-song) but here beginning a lament upon an old man.

[6] I had a little bird in a cage, and I had tamed it, and fed it with sugar, fed it with musk. And from the musk in plenty, and from its perfume my bird was naughty, my nightingale fled.

Listen to this, old Stavrian6s! You've made your wife a slave, and your children and grandchildren.

It may have only a general relevance:

[7] If only the dead of the world could return, the mother would not mourn her child, and the child its mother, wife and husband would not mourn, who loved each other deeply. But when the sea dries up and turns into an orchard, when the olive gives us wine and the grape gives us oil, then we shall expect them to come out of Hell.

Nicolena, my little goose, my little swallow on the cliff. Alas, fine mistress of the house, who kept her house so humbly. My sieve of silk, who made fine white bread, and made much out of little.

More often, one sees an attempt to make the prooemium fit. A particularly beautiful example is this lament for a little boy. In Mani, male children are so important that they may be called

271

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

by the same term 'master' (aphendi) that is applied to their fathers; in Inner Mani the augmentative form of their name is used where a diminutive would be more normal in most of Greece.

[8] There is no sprig of herb that is scented like a child, not the fine basil nor the marjoram - only the frankincense that the priests keep and put into the censer on red-letter days.

My Giorgakis, my master, joy and plaything of the house, enjoyment of our table. My eyes, my little child, my silver candlestick.

A rougher sort of assimilation occurs when the name of the dead person is fitted in, with more or less dexterity, to an independent poem. This prooemium comes from the days of the slave-traders of the Mediterranean, and Death has a new persona as a slaving- captain. Christos, the dead man, is introduced clumsily, but the use of the widow as a transition-motif between the two parts is more ingenious:

[9] A ship was sighted far out at sea, and the word ran through the villages and through all the province: 'Women, your husbands are coming; mothers, your children come; sisters, poor sisters, your brothers are coming back!' Mothers went out with golden florins, sisters with golden pounds, and the widows, the black widows, with the keys in their hands. Christos was sitting in the stern of the ship. He fell down before the master, and begged him to put him on the shore, to go to his own kin. 'A curse on the mothers' florins and the sisters' pounds.' And the widow, the black widow, crosses her arms in prayer:

'Listen, Christos, my master, dolphin and ghost, warrior elect.'

The surprising 'dolphin' (delphini) is a corruption of delini, an 'earth-spirit' or 'elemental'. While the corpse is unburied, the soul still ranges the earth.

272

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

More successful is the assimilation of the following poem. The theme of the horrifying prologue-youth and the dissolution of the grave-is artfully echoed in the lament proper, that begins with 'youth', goes on to speak of the young man who is dead, and ends with praise of his physical beauty, that now in its turn must rot:

[IO] He did not fear anything on his first night in Hell. But the snake came and sat upon his head, and began at the eyes that were white as curdled milk, and went to his eyebrows that were like plaited silk, and went to his tongue that sang like the nightingale, and was the rival of the birds when they sang together.

Youth such as this, and chosen manliness, should have two hearts in the breast and two guns at the side. Moustache like a craftsman's masterpiece, back straight as a rifle-barrel, famous fighter! No man came out to face you. But there came a time [poor man] when they broke faith and killed you treacherously. Listen, Alexis, my master, who had a back like a floor: it will rot in the earth! Alexis, body without an heir, listen, paper without writing..

The second difference is already illustrated. The narrative that, as we shall see, is the bulk of the pure lament of Inner Mani, is almost completely absent in the mixed genre. Here, the octo- syllables are of praise and description. The lament for Alexis that has just been quoted contains just two or three lines that might be regarded as a rudimentary narrative of the subject's death, and even this bare mention is exceptional. In other words, the two parts of the mixed lament have grown towards each other. The politicals have been varied more or less to suit the lament: but the octo- syllables have quite lost the characteristic quality of the Inner Maniote lament, and retain only that part of their nature that is

273

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

close to the common Greek usage. In many parts of Greece the 'vocative' eulogy of the dead is an important element, even the principal element, in mourning.

Thirdly, the octosyllables of the mixed lament differ from the pure laments in their treatment of rhyme. Rhyme is not an essential element in the poetry of Inner Mani, and there is at least one lament that has none. Generally, however, there is a tendency to rhyme, not only in couplets, but also in groups of three or four, or even as many as eight lines together. In this, the folk-poetry of Mani is at the point that political verse reached in most of Greece towards the end of the fifteenth century.

When we examine the narrative laments in our three collections, we find that in Petrunias' work and that of Theros (whose own collecting took place before 1i910o, but who incorporates contribu- tions from a much later period, perhaps even as late as 1950) the proportions of rhyming lines are almost identical-43.o% and 43.2%.2 Both Petrunias and Theros concentrated upon the poetry of Inner Mani-the former almost chauvinistically. Pasayannis, who worked both in Inner and in Outer Mani, has a significantly higher figure, 49-7%, for his narrative laments. When we turn to his mixed laments, the figure for the octosyllabic sections goes up to 56.2%, and more than a quarter of them are entirely in rhyme. Petrunias publishes only three mixed laments, all of a period later than Pasayannis; all three are completely rhymed. We see that the octosyllables in the mixed form have moved towards the common Greek form not only in content, but in technique. Even more noticeable is the fact that three poems from this small corpus have political lines appearing among the octosyllables. It is clear that when the two styles meet, the longer line which predominates over most of Greece is obviously the stronger.

The observations based on the mixed lament in North-West Mani are borne out by the emergence of the same form in North- East Mani, in material collected in the Gythion area about I96o. There are eight pieces, of not very great quality. The proportion of rhyme is very high indeed, so high in most of the poems that it

2 There are considerable difficulties in taking these counts, and the figures would be much higher if accent were ignored, or the final sigma of certain forms were dropped, as often happens in the dialect of Mani. But the same method was used for all the material, and the relation between the figures would be much the same if other principles were adopted.

274

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

has become the norm, and the occasional unrhymed line has the feeling almost of failure.

OCTOSYLLABIC LAMENTS

The narrative laments of Inner Mani stand alone in Greek folk- poetry. They have a naivety that is at the same time prosaic and ominous, ready to erupt at any moment into passion. Here is a lament from Yerolimena in the far South. His mother mourns for the young man Dikbos Kundunakos, killed in the Balkan War of I897. The simplicity of her memories, the meaning of her life summed up in a dozen lines, is shattered by a torrent of agonized questions.

(In the interest of space these laments are printed double column)

[II] When man and wife come together they lay their heads on one little pillow. They reckon, they plan, to make good sons, and to leave much wealth.

When we came together - a crazy man and a poor

woman - we laid our heads on one little pillow. We reckoned, we planned, to make good sons.

We made a good son, and set him to study, and sent him to college. And when a great war came, the King sent a paper that our Dikdos should go.

O raven flying by with the coal-black feathers, where were you, where do you

come from? From Lirissa, from Domok6s? Have you seen my Dikdos? Did he give you greetings to carry to his mother? That she should make his funeral

meal? That the priest should say his

blessing? Or perhaps you've brought some token of him? A hand, a foot, or his little finger with the silver ring upon it?

As late as the fifteenth century, Maniotes still preserved the custom

275

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

of keeping the hand or finger of a dead man, to dip in the wine at banquets.

In the next lament, for Vagakis, the outburst comes first. His widow feels that she can go up on a mountain peak and shake the world with the intensity of her sorrow, just as the hero Digenis wished in the moment of his death to grasp the ring on the door of heaven, and make the whole firmament quake. Then her lament turns to mourn Thodorti, a kinswoman who had died before. (It is not uncommon for past bereavements to be incorporated in the new, sometimes with only the most perfunctory reference to the corpse that is laid before the mourners.) The question "Where are you?" brings her back to herself and her surroundings. She must greet the guests and thank them for their condolences- another frequent theme in these laments-and then, only then, with her first passion drained, can she address her dead hus- band.

[Iz] I shall go up to Ano Pula to see the stars in heaven, to shout a wild scream for the universe to shake. Where are you, Thodorfi? - to loosen your plaits, to tear your hair like a preening

duck, for the tidings to be borne, for Th6doris to hear in the cafe, in the shop, where he drinks the red wine; for his glass to crack, and the wine to spill. Where are you, Mistress

Vagsikena?

- on Saint Philip's Morn, when you've laid the table with seven kinds of food, with the silver plates and the golden forks; and the Mayor has come in with his clerk, and they went up on the parlour-

floor and walked there for a long while as their tears fell.

Vagakis, universe and world, and all my neighbourhood! You will not come again to the Sasariani

Death can break glasses and spill wine. In the lament for Gitas Spentzurakos, his wife tells the dying man to go as a ghost and bring the news to his brother, so that he may come back to the village. We are reminded of our own stories of clocks stopping and mirrors cracking when a far-away kinsman dies.

276

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

[I31 When Gitas lay dying, mumbling at midnight, I combed his hair smartly, combed his shaggy hood, and twisted his moustache. And I held him and I asked him, 'Gitas, do you owe any money? - for our children are young, too young for work.' And he said he had no debts. 'Then, Gitas, go now to Phytii in Kalamata

where Poitas is training in the Royal Infantry. You must give a sign to him, for his straps to burst, or his rifle to misfire, for Poitas to understand that our Gitas is going away. Perhaps the commander will say 'What, Spentzurakos, are you a

coward?' 'No, but my eldest brother is

dead.'

The poverty of widowhood is a frequent theme. In the mixed lament for Christos, the mothers and sisters come down to the shore with gold in their hands, but the widows bring only the keys of their houses, all the possessions that they have. The next lament was sung in the Maniote community in Athens in the twenties, after the death of a young man from tuberculosis. The mother appeals for help that she may take the corpse back to Mani, and then retire to an oblivion in which (the phrase is untranslatable and sardonic) she may be proud that she had done for her son all that she had done.

['4] I rose early in the morning to go down to the lowland to Doctor Chrysospathis - a good and famous man - to take him my lovely son, my dear, only, son. For he was all I had, no brother and no sister, no daughter did I have. And when I got there [Phyti in Kalamata] Doctor Chrysospathis said 'To make him better, this beloved son of yours, you must take him to professors, who have many medicines

and a wealth of knowledge.' I took him and I laid him in a railway carriage. I borrowed for the tickets and used up all my money. And when I got here and the doctors said 'No hope', he understood it all, made a sign to me, and said 'Mother, poor mother, hire me a car and take me to our house. You've wasted your time and my youth is wasting.'

I beg of you,

277

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

all you men of Mani, whose word is like the cross, let me take my child.

When I became a widow I was twenty-four, a housewife in poverty. I ran here, I ran there, to Elos and to Durali, to work for other people, to raise my child;

for him to go on studying and become a scientist, so that I might see old age. Now I put him through his studies and he got his degree, and God has taken him from me. I beg of you, help me, all of you, that I may go to Ayia Kyriaki, and lock myself in to be proud of my zeal.

So the lament goes on. When each woman finishes, she literally 'hands over' the lament to her successor, stretching out her hand over the corpse to touch the hand of the woman who is to follow. Sometimes the handing-over is accompanied by a line or two giving the woman's name. If possible, women from outside alternate with those from the family, but every woman must have her turn and 'mourn her fill'. The technical term is klaio, 'to weep', and weeping and sobbing accompany the lament from the beginning. The orderly sequence of lamentation may be changed, as the next two examples show. In the first, Giorgikena is overcome as she mourns her drowned son, and a kinswoman continues the lament. (There must be no break, for such interruption is the worst of omens.) The kinswoman's lament is pedestrian. Obviously she had not been anticipating the sudden need to sing. But soon Giorgikena resumes, imagining her son coming wet and naked to the Under- world, and appealing for the older dead to take care of him:

['5] [Mother] Saint Dimitris, master, did we not burn incense, did we not burn you candles? Did not my Dimitris bring four silver candlesticks, a golden chandelier, and four candle-pillars of iron? Why did you not help him in the straits of Cythera, when the storm came on the sea and piled the heavy waves and drowned angelic bodies?

[Kinswoman] Mistress Giorgikena, you had an only son. Katsimandis admired him and made a sailor of him, and he went and drowned in the straits of Cythera. [Mother] O my dead kinsmen, give him clothes to dress in, warm him by the fire for my son not to get cold.

278

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

The circumstances of the next example are strange. The dead man is Yannis Pilokotsifnos, who had married into the Sid&ris clan. Later, one of the Pilokotsiini had been killed by a Sid&ris, and a vendetta exists between the families. Yet members of both sides, in a state of truce, are present to lament the dead. One of the Siddris women mourns in terms meant as a provocation, sug- gesting that Yannis had taken part in the decision to hold vendetta against his own family, but she is interrupted violently by the oldest of her clan, who (in a way untypical of Maniote society) regrets that her small family had become enemies of the powerful Pilokotsiini, whom she describes as a 'Russian kingdom'. This is a metaphor from the eighteenth century, when the Orthodox Empire of the Muscovites was the great hope of Greece against the Turks. The old woman's words seem to prepare the way for a reconciliation.

We did not count you as a brother-in-law,

but as a Sidiris - O my golden cupboard in the night and in the day...

[The eldest of the Siddris women interrupts]

Be careful, filthy tongue, do not insult the dead and offend another, or I will uproot you whole! Be patient for a little while, my friends and my enemies. My mourning is not proud, I have no wish for boasting. I say that they were wrong and that they did great harm, my few kinsmen and my poor husband. If only there were worthy good men

to pour cold water on you, for you not to commit a wrong against the Russian kingdom. You know very well we had no quarrel with the Pilokotsiini in those early days. They were beloved brothers, of one loaf and of one cup. Cursed be Satan who schemes and comes between brothers who loved each other. At one breast they suck, in one cradle lie. Yannis was a man of sense, a man with pride and honour. When the weather broke and the times had changed, he came no more visiting in the Siddris lands.

Those who have read before of Maniote society may think it eccentric to have gone so far before mentioning the vendetta. To most observers it has seemed the outstanding fact of existence in Mani. There are other places where vendetta has been a way of life: nowhere has it been more cruel and relentless, nowhere has it so pervaded every fibre of society.

279

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

When a family felt that it had been gravely insulted, the male members held a council, and decided by majority vote whether vendetta should be declared. A formal declaration, in set words ('We are enemies, and you should know it') was necessary, unless the insult had been a killing or an offence against a woman. The council, having decided upon vendetta, drew lots to find an avenger, whose duty it was to kill a male of the other family. The person who had committed the offence was not necessarily the one marked out for killing. More often, the council would decide to kill the most effective member of the enemy.

Once the decision was made, an inexorable process had been started. The victim might go far away, to Athens, to Egypt (this seems to have been common), even to America, and years might pass; the duty of murder still lay on the avenger, and was often fulfilled. But this was not the end. The killings would go on until one side was wiped out, or a reconciliation took place. Such an event was rare and could come about in two ways. One was by the intervention of a clan so powerful that its prestige could impose itself on the warring families-an uncommon situation: the other could happen immediately after a murder, when the killer would go and kneel before the mother or wife of the victim and beg her forgiveness. If this were granted, the two clans became united as blood-brothers in a bond so close that marriage between them became impossible.

Vendetta shaped society. Women were exempt from all the slaughter unless they so forgot themselves as to take up weapons. A man was known as a 'rifle', and the birth of a 'rifle' was announced to the world with fusillades and feasting; the birth of a girl was ignored and made its parents sad. The strength of a family de- pended on its males. There is a famous couplet, all that is left of a lament on an eight-year-old boy. He was the only male left of two warring clans; when he fell ill and died the mourner sang

['7] The amber has lost its scent, and the phial is cracked. A little cannon burst, and the tower is disarmed.

One of the greatest of Greek critics sets this among the five best folksongs of Greece.

People lived in towers from which the men shot at each other,

280

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

while the women worked in the fields. Towers might be armed with cannons and a vendetta might involve siege-operations, with mining and sapping. A tower higher than your neighbour's gave you great advantage, but to build an extra storey might itself be the provocation to another vendetta.

Life would have been impossible without some alleviations that the system allowed. There was a code which provided for truces of various degrees. Some were for the necessities of a poor agri- cultural existence-sowing, harvest, the gathering of olives: others were more complicated. One was called the 'splinterless truce': it stopped hostilities as long as neither side added even a splinter to the height of its tower. Another confined the war to sniping from towers, with the proviso that if a shot missed its mark, the gun that had fired it had to be surrendered. This usually meant a complete cessation of hostilities. To a Maniote, being disarmed was the greatest of disgraces. Even in modern times, poaching episodes which elsewhere in Greece would have led to the grudging surrender of the poacher's shotgun have in Mani produced battles and murder. Rarest truce of all was one which confined the vendetta to specified members of two families which had previously been close friends.

Laments for victims of vendetta might be sung by men, and there were famous male mourners just as there are still famous women-mourners. The last recorded instance of a male mourner seems to have occurred in I935. The style of the male lament had certain differences from what we have met so far. There is one example dating from 1841 which seems to be part of a series of couplets, an exchange of epigrams between the visitors and the dead man's kinsmen. In this century, the octosyllabic style was used by men, but without the common lament-tune. The lines were delivered in a long-drawn-out recitative. The first four or five syllables were chanted very slowly, with long distorted vowels. The end of the line was still slow, but distinctly faster than the beginning. There seem to be only two published octosyllabic laments that can definitely be ascribed to male mourners.

The laments for people who were murdered (as opposed to those who died 'by the sword of God') have become the ballads of Mani, that are remembered and repeated, and suffer the changes in- herent in oral tradition. Some of them have lost the marks of the

R 28i

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

occasion that we see in the recording of funeral improvisations- the welcome to guests, the compliments to other mourners, the signs of 'handing over' and above all the impassioned vocative to the corpse: others keep remnants of these things. In all, it is the narrative that has become supreme.

The lament for Poit6s the Deaf tells its own story of the mechan- ics of vendetta, with no complications. Its interests lies only in the disguise, and the journey overseas. The date is closely fixed by the building of the Alexandria railway, that was completed in 1855.

[I8] Forty-five men at Petalidhi on Stavri held a clan council to draw lots for an avenger who would go after Lazaros. The lot fell on Poit6s the Deaf. And so they bought a boat and gathered money for him and put him aboard. Over the mountains he went to Spetses and to Ydra where he'd a first cousin. He stained him like a negro and dressed him in Turkish

clothes. Off he went from there, and crossed to Alexandria. And there, on the railway, Lazaros was working. He found him in the store, and took out his pistol.

A pistol-shot he fired, and took his strength away. Lazaros shouted loudly, 'The negro dog has killed me!' 'It was no negro born, it was Poit6s the Deaf.' Off he went from there, and came back to his home. 'Mother, congratulate me, for I have killed Lazaros.' 'If it is true, Poit6s, that you have killed Lazaros, - five caiques we have, and all of them we'll sell, to buy a cage for you. In a cage we'll put you to keep you safe from harm: and if it is not true, that old ship of yours shall be broken all in pieces, and we'll drive you from us.'

The most famous of all these laments of vendetta is the song of Ligor4i. There are at least nine published versions, and many more unpublished. It is a measure of the 'balladizing' (if we may use such a term) of the original lament that the versions range from 25 to 249 lines. All are completely narrative, shorn of any of the funereal conventions. The laments of Mani are often characterized by a precision of detail far removed from what we expect in Greek

282

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

ballads as a whole; but the lament of Ligorii surpasses them all, and gives a close picture of a society that has now vanished. In addition, the facts narrated in the poem are supported and ex- tended by a rich family tradition recorded in Mani within the last twenty years.

The story happened in the years 1828-36. There was a vendetta between the Liakakos family of Alyka and the Li6pulos family of Upper Bularii. Petros Li6pulos killed Dimitrios Liakakos at a spot on the seashore, called Yiilia. Dimitrios was generally known by his nickname 'V6tulas'-'a young goat'-perhaps because of his hoarse high voice, perhaps because of his agility.

V6tulas' sister, Ligorii, was married to a man who lived in Kitta. On 14 September she set out to visit her family in Alyka. Her way took her through Upper Bularii. Most of the versions suggest that she had mistaken the path; their performers obviously cannot understand why a woman should have walked past the houses of her enemies. But all these villages lie within a radius of two miles. To the outsider, it seems impossible that Ligorfi could have made a mistake; she was doing what she did deliberately, provoking the revenge that was to follow. In the village she met Petros Li6pulos. Playing maliciously on the name 'Vitulas', he offered compensa- tion suitable for an animal. What follows-the killing of Petros by YAnnakas Liakakos-is told in the lament.

[x9] One Saturday morning Ligori got ready to go and see her family, from Kitta back to Alyka. On the road she went she passed through Bularii and through Spiliotiinika, as the priest was ending his

service. All the men were sitting in the

street and were playing cards. She made her heart like a stone and greeted every one. And not a man replied,

except V&tulas' killer; Petros Li6pulos got up from his chair and welcomed her courteously: 'Welcome to Ligorid, welcome, welcome to you! And if you're going to Alyka, please tell your kinsmen there [and Yinnakas especially] that if he wants us to put things

right, then we're prepared to pay for that old goat of theirs six pounds, say, or even seven, or even put it up to nine.

283

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

But if they won't take nine, then the brine can eat it down on the shore at Yiilia. We've set it as a watchman on the cisterns at Monodendri. More than that we shall not give - not a brass farthing more. They can do just what they want, just as the fancy takes them.'

When Ligordi came to Alyka she passed along the Litoma, where they all sat in the street. She greeted not a man of them. Her sister-in-law rose before her; 'Welcome to Ligori ! Tell me, what is your bitterness that you did not greet us? Has anyone struck you or spoken filthy words?' But she did not speak, and went on to their house. Now Yannis was a clever man and straightaway he knew that she had met the enemy and that they had mocked her. Swiftly he caught up with her - 'Welcome to Ligorii, welcome to Beikis' wife! Tell me, what is your bitterness that you did not greet us? Has anyone struck you or spoken filthy words?' 'Since you ask me, I shall speak. Nobody has struck me or spoken filthy words. On the road as I was coming I passed through Bularii as the priest was ending his

service. All the men were sitting in the

street and were playing cards.

I made my heart like stone and greeted every one and bade them all good-day. And not a man replied, not one gave me answer, except VWtulas' killer, Petros Li6pulos. He answered me and said 'Welcome to Ligori, welcome, welcome to you. And if you're going to Alyka, please tell your kinsmen there [and Yainnakas especially] that if he wants us to put things

right, then we're prepared to pay for that old goat of theirs six pounds, say, or even seven, or even put it up to nine. But if they won't take nine, then the brine can eat it down on the shore at Yilia. We've set it as a watchman on the cisterns at Monodendri. More than that we shall not give - not a brass farthing more. They can do just what they

want, just as the fancy takes them.' And Ligori screamed out 'Vitulas has no brother! Not a man in his family to take back his blood to avenge his death! A bird of the wilderness! If only I'd been a man!'

The fury came on Yinnakas like a madness on him. But he waited and was patient until the dusk came down. Then he went to his sister-in-

law.

284

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

'Give me the Sarmai3 that's on the rifle-rack with the rust eating into it. Night is coming on, and the cow still not in.' But she understood that he was out for murder, and she spoke to him and said 'Sit down, master, I'll go with your wife, and Ligord as well, and we'll take our mother with us. For the enemy will kill you just as they killed VWtulas.' His mind was filled with agony, and he took down the Sarm~i, and dashed out of the house. At the door as he went out Yannis struck the gun: 'Listen, masterless Sarmi, either VWtulas shall be avenged, or the rope will double. If I'm not back by morning throw my pebble down, just like VWtulas'.'

And so off he went. On the road as he was going he heard the sound of running feet. He turned back and looked. It was his poor sister-in-law following after him. 'Yannis, are you leaving me for PNtrakas to drive me out?' 'Dimitrdi, go back,

for the rage has come upon me for my mind to climb the

mountains and see the whole world smiling.' 'Tell me, Yannis, master, how long shall I wait for you, when shall we expect you?' 'Until the sun strikes down: if I do not come and show my face, throw my pebble down just like V6tulas'.'

He took the road for Bularii. At the foot of Bur6lia a goat bleated high upon the cliff. 'Come close by me, Satan, let's do our work together. Or if it's you, Dimitrakas, come and keep me company, for I'm going to Bularii.' When he got to Bularii, at Petros Li6pulos' house the doors were all shut. He stood at the front gate, and waited and listened, and nothing did he hear. He pulled at the latch, but it did not open the gate. He waited, then made up his

mind and sprang across the fence. He sat by the hen-house and made the Sarmi ready and primed it for firing. Then the door opened

9 The Sarma was a flintlock, probably one of the Austrian style that was used all through the Balkans in the first three-quarters of the nineteenth century. It was simple to load and maintain, but suffered from frequent misfires, a shortcoming which provides one of the great moments of this poem. It was superseded by the 'Gras', mentioned in many Maniote laments, including nos. 21 and 25 in this article. This rifle was invented by a French officer of the same name during the Franco-Prussian War, put into production in 1874, and supplied to the Greek army in 876. This may be a dating-criterion for some folk-poems, but it is possible that the various terms were used indiscriminately.

z85

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

and a woman came out, to give the oxen straw. This was his opportunity to go up on the porch. He came close to the keyhole and looked inside. He saw the killer sitting, playing with his child: he heard him shouting 'Women, bring the barley-

cakes.'

Yinnakas pulled the trigger, and the gun did not fire! 'Oh! well done, Satan! You promised me, then tricked me.' Again he pulled the trigger and the Sarmi fired through the keyhole and found Petros' heart. There were screams and shouts

inside. Yannis jumped up and ran. He found the gate was locked and so he gave a leap and jumped across the fence. But the old gun caught there, caught so he could not free it. 'Free yourself, old Sarmfi, for I shall leave you there. I have done my deed.'

And so off he went and came to Niasa where he had alliance. He spoke to the watchman, and Lias it was that answered. 'Who is it speaking there? What do you want at this hour

of night?' 'I am Yinnakas, and I have killed your uncle, who was your mother's brother,

Petros Li6pulos.' 'Hurry from here, Yinnakas, go to the Skyllakiani tower, lest my mother should come and lay her curse upon me.' Yinnakas hurried away and went to the Skyllakiani

tower.

Old Liak6l waited patiently until it was breakfast-time, and Yinnakas had not come. And Old LiakAi got up and walked out on the highroad, screaming and shouting: 'Yinnakas, Vitulas, I shall mourn for you together.' As she went by Kivaros' house a good man passed her by, it was old Kyraklilakas. 'Eh! Uncle Kyrakdilakas, have you heard any news from Upper Bularii? What is the wailing for?' 'The best of the clan is killed, the first of their elders killed, Petros Li6pulos.' 'And who was it that killed him, that old stupid ox?' 'They say that Vitulas came back and they found his gun, that old Sarmi.'

Old Liakdi hurried on and went to the Skyllakiani

tower. There she spoke to Gi6rgaros, 'Come out, Giorgo, let me see

you, and ask, for you to tell me, is Yfinnakas in here?' 'Yinnakas is here. Go your way, and do not worry.'

286

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

There are many things in this that might hold our attention. There is the belief that when a man dies a pebble should be thrown into the sea; and that a murdered man may cry out in the night for vengeance-here in the voice of a goat, elsewhere as the sound of the wind or the distant sea. There is the mention of the 'alliance' (syntrophid) sworn between young men, that could act as a counter- balance for men from small and weak families against the power of the great clans. There is the pathos of V6tulas' widow, newly married when her husband was killed. In this strange family, Yinnakas is her protector, but his younger brother wants to drive her back to her old home, where she would be a useless burden, despised and condemned to a miserable life. (The tradition tells us that she was in fact pregnant, and that one branch of the Liakakos family is descended from the son she bore.)

Above all these details is the sense and structure in the poem. There is hardly any exposition. Ten lines of peaceful, almost idyllic description are suddenly broken by 'she made her heart like stone'. Li6pulos' words are like a bitter ritual that must be repeated without the change of a syllable. The formulaic structure of the first half gives way to the agonized precision with which Yinnakas' approach to his victim is narrated. The slow tension culminates in the first failure of the gun-a poetic coup-and then everything is hasty and abrupt until the tower of refuge is reached.

There are internal echoings and balances. The street of Bularii is matched with the street of Alyka. The unanswered greetings of the one are balanced with the unspoken greetings of the other. The play on V6tulas' name comes first from Li6pulos, and then from Yinnakas as he hears the bleating of the goat. Ligorli's measured narrative ends in a sudden scream; her mother's patient waiting ends in a sudden scream. The trinity of women, Ligori, Dimitrfi, and Old Liakfi, are three aspects of Maniote womanhood placed at the beginning, the middle, and the end of the narrative.

Finally, what translation cannot show is the completely demotic purity of the poem. There is not a word from outside the everyday Maniote dialect, no hint or suggestion of any influence from learned literature.

The family traditions have preserved a detailed account of the way in which Y~nnakas evaded his enemies and succeeded in getting back to his own home at Alyka, and also of the vendetta

287

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

that followed. It ended with a ceremony of reconciliation, in which the killer was forgiven by the widow of his victim. The two families became blood-brothers, and have remained closely connected right up to the present day.

Yinnakas himself went to Athens in I840, and took up service in the bodyguard of that eccentric figure, the Duchess of Placentia. One of her palaces is used today as the Byzantine Museum of Athens, on Queen Sophia Boulevard; another stands in ruins on the slopes of Mount Pendeli. Once, when Yinnakas was returning from Athens to Pendeli, he was forced by a storm to take refuge in a police station at Psychik6, and met some Maniote exiles who were serving in the Royal Constabulary. After much drinking, they fell to singing laments, and Yinnakas was moved to tears by the story of his own deeds in the lament of Ligorii.

He died in 1893, at the age of ninety-three. His family has a photograph of him, an old man with beard and flashing eyes.

One of the most terrible situations of the vendetta was that of the woman who married into a family which later declared war on her kinsfolk. This conflict of loyalties led, in one famous lament, to the poisoning of a household by the daughter-in-law. The example we shall give is more restrained, but has its own merits. The flat narrative is suddenly lifted by the mother's lyric outbursts. In the middle of the poem it is the tie of maternity that inspires her, the memory of her first child: at the end it is the tie of blood, the death of her only brother and his son. All through the poem the formulaic repetition of their names comes like a knell.

[2zo] On a Monday morning my sons came to me - Livos and Nic6las -

for me to give them blessing from my heart and from my soul, that their uncle should be

avenged and the stain be taken from us. 'Go with my blessing, Divos, and do what you will. One thing alone I ask you: Divos, spare for me

Constandis and Vrett6s, my brother and my nephew.'

So off they went away to Ayia Kyriaki, and there they waited for the enemy to pass. They lay down to rest, but Divos, who was sly, put a sharp stone under him so that he would not sleep. In the night, at midnight,

288

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

he heard the sound of feet, and said to Nic61as, 'Nic61as, master, wake. Here comes the fat ram and the lamb for Easter.' Up they rose and loosed a volley: killed their uncle and their first cousin, Constandis and Vrett6s, the brother and the nephew.

They got up and fled and crossed to Kechriinika. And their mother asked them 'Tell me, Divos, master, you who were my first child, and broke the silver button and sucked the virgin breast; tell me what success you had in Ayia Kyriaki.' 'Why, mother, what shall I tell

you? We had no success. We lay down to rest,

and the enemy passed us by.' 'Now you tell me, Nic61as, you who were my last child, and sucked my breast so long. Tell me the bare truth.' 'Why, mother, what shall I tell

you? D~ivos is sly, and his talk is lies. We have killed our uncle and our first cousin, Constandis and Vrett6s, your brother and your nephew.' 'I would have wished, my

children, that the bullet had turned to chill your hearts; it would have been better than

killing my brother and my nephew, Constandis and Vrett6s. How shall I live my life? - he was my only brother. How shall I live my time? - in his assassin's house.

The change of aspect as the poem procedes, from first person to third person, is found in many of these laments, and may reflect the transition from real mourning to ballad.

Another possibility of heroic lamentation came when there was a breaking of the taboo that kept women outside the workings of the vendetta. The lament of Paraski begins with the amazing metaphor of her father's death. He is seen petrified, a carved monolith on a threshing floor, sculpted by Death the Master-Craftsman. It was on a threshing-floor that the hero Digenis wrestled with Charos, like Hercules before him.

A more mundane narrative follows, that suddenly shocks, as the dying man tells his daughter to carry on the vendetta. There is a weaker version of this lament, without the magnificent opening, that goes on to say that Paraski refused her father's command, since it would bring disgrace on him. Yet something has already

289

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

come through to us of her nature, that could prompt her father to such a thought. When she hears the shot, she realises 'that shot belonged to me': she is already in the vendetta in her mind. The threshing-floor is already 'my threshing-floor': she is the head of the household. She speaks to the killer, at this moment when you might expect hysteria, with sardonic confidence, uttering the ultimate provocation.

[zI]

The6doris Achumakakos, you were a rounded stone and a flower on the scree. You were not seized by hands, you did not stand at the wall. But you found the Master-

Craftsman, the excellent stone-mason, and he hewed you finely and stood you as a marker in the middle of the threshing-

floor.

Towards evening I was at home, I'd started to make barley-cakes. And I heard a rifle-shot and sprang to go outside. Immediately I knew the shot belonged to me. I saw the killer coming with his Gras across his back and the strap over his shoulder. 'Bravo, my warrior! So you have avenged her,

the ring made of wire, a whore to all the world?' And off I went and ran to my threshing-floor. There I found my father writhing like a slaughtered beast covered all with chaff. He was on the stone ledge, and I heard his voice so harsh: 'Come close to me, my Paraski, and take off your shawl and gently bandage me; for the bullet's got me in the place where there's no

healing. My belly and bowels are out. Go and take my Gras from the wild walnut-tree. Over the mountains with you to hunt the killer down, to hunt these mules from

Yerakarii, these treacherous dogs who kill me in treachery.

Every death deserved its mourning. If a stranger died in Mani, then strangers would mourn him, and his isolation would be the main theme of their lament. Here it is the aunt of the killer who is kneeling at the side of the corpse:

290

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

[22] If you wanted to be a killer why did you not decide to go to the pass of Kunos to the house of Ikonomakos, to find Damitranos and cover yourself in glory from your head down to your

toes? But no, you went off and killed the poor old policeman, just for a bit of bread.

Eh! great fat Kyriakdlakas!

But greetings to you all! Mourn, let us all mourn this policeman who lies here. He has no mother or sister to stand beside his coffin to clench her fists and beat

herself, and to pluck out her hair.

The last example of the vendetta laments is undistinguished in comparison with some that have gone before. It deserves our attention for two things. It shows how small a change of attitude was needed to turn the plain narrative into satire. Secondly, it records the chief factor in the breakdown of the vendetta system, the intervention, in strength, of the forces of the law.

[231 What a shameful family! O Mayor of Stephanii, Dikio from B~imbaka and Michalakos M6phoris - Voidis killed you all, and Damian6s wasn't there! Come on, Damian6s Bathrellos, vampire of Sivvata! Come, Bathrellos, it's time for

you to take your company and go down to Trinisa, where Voidis will pass by,

for the Mayor to be avenged.

And so they went to Trinisa, and came across a band of men, but Voidis wasn't there. It was the King's Constabulary, and they started shooting. M6phoris was killed, and Damian6s was wounded. Stavrian6s was shut up in the sanctuary of the church. And Chondrokukis the coward jumped into the sea.

Intervention in Mani by forces of the law on near-military scale had started soon after the liberation of Greece in 1828. A hundred years after, it could be written that vendetta had completely dis- appeared from North-West Mani, and that cases of individual murder for revenge were fewer than in other parts of Greece. Elsewhere in Mani, at the same date, the system of vendetta, with its clan-councils and allotted avengers and shooting from towers,

291

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

was also extinct, but there were still many cases of revenge-killing. Now, however, it was the offender who was killed, and not any other member of his family.

Severe depopulation had also sapped the strength of Mani. Recent writers have described the strangeness of walking through villages that are completely deserted in the day, and gain a half- ghostly existence in the evening as a few women come from the fields. Already in the last century there was emigration to Piraeus, to Zikynthos, to the mining community at Lavrion in Attica, and to Smyrna. It is a measure of the poverty of Maniote agriculture that many families elected to go from there to farm semi-barren areas of Thrace and Macedonia. Even when there was no perma- nent emigration, the men regularly went out of Mani to work as labourers in richer parts of the Peloponnese.

This economic decline was the result of the disappearance of Mani's trade by sea. In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Mani, as a semi-independent state in a strategic position on the Mediterranean sea-routes, had developed a rich overseas trade (mixed with a certain reputation for piracy). Even as late as 1855, we hear how the family of Poit6s the Deaf had five caiques. With the shift of Greece's centre of gravity to Athens, the building of the new port of Piraeus, and the increase in the size of merchant- vessels, the old seafaring communities of Greece-Mani, Syra, Spetses, Hydra-fell into decline.

There seems to be in the folk-poetry no expression of this economic catastrophe. Another factor, however, is stressed time and time again. In the early years of Greek independence, the Maniote chiefs, who felt that they had contributed so much to the struggle for liberation, were out-manoeuvred in the political turmoil of the new state. In particular, they had attached them- selves closely to Otho, the new king imported from Bavaria, and had suffered severely in his disgrace and expulsion. From then on, Maniote influence in politics was very small, and economic aid to the area was slight.

The army was a natural profession for the men of Mani, and we have laments for people killed in all the recurring Balkan Wars. This attrition, coming on top of the economic and political pressure, seems to have produced a kind of sublimation of the old instincts towards vendetta. The women's laments begin to talk more and

292

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

more of the wastage of men who should be fighting against the common enemy. The mother of Yannis Arvanitis, who had been killed in Northern Greece in 1912, calls upon her sons to help in rearing the dead man's child:

[24]

Another day will come, and there will be a war. Giorgis will join up, and go up to the front near his father's grave. He'll shout a fierce cry for the whole land to shake and our Yannis to be avenged...

She tells her daughter-in-law not to take from her dress the coloured band of braid, as all other widows do, but to wear it as a sign of her pride in her husband's heroic death.

These sentiments-the sublimation of the vendetta into patriot- ism, the political resentment-are heard clearly in the lament for Dimitrios Livanis. The circumstances of this lament are very well recorded. It was taken down by a schoolmaster, G. D. Manolakos, at the tiny village of Pachiinika, on Christmas Eve, 1912, when family and friends had assembled to mourn for Livanis, who had been killed in Epirus. His father had just come back from Epirus, where he had gone to see if the report of his son's death was true. The invited mourning-woman was Dimosthinena Kuvarina, from Kokkila, whose own son had recently been killed in the battle of Sarandiporos (and whose husband was to be the subject of another published lament when he died fighting in Asia Minor in 1922). She was answered by Stavrianti Murkikena, grandmother of the dead soldier.

The songs of both mourners are extraordinary in the absence of the expected lamentation. The content is almost entirely political-international diplomacy seen through the eyes of peasant- women in a remote province, naive and shrewd by turns. Dimos- thinena explicitly rejects the idea of lamenting a person who had died for his country, but this is too much for the older woman, who contradicts her.

293

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

[251

[Kuvarina] Dear Stavrianmi, your every wish is mine. Women, on left and right, allow me to begin.

Three years have gone by since good Venizelos [who is a great minister, and life to him, long life] knew the secret, and this year he revealed it. Four powers all together have warred against the Turk. Everywhere they have conquered and put him to shame.

Come close by me, Livanis, who went up to the fighting. Tell me, what did you get from

it? Where are our children? Yesterday in my house I was dressing my children for it was holiday and feast the day of Saint Spyridon and off Cape Tainaron our ships were passing. All our sons were shouting greetings for us to carry to their homes; for they were going to Yinnina, going to the battle, to conquer the Turk. And if they did not conquer, they would not come back. Come close by me, Livanis. Do we not think it wrong, and a great disgrace, to mourn for our sons? Why, the women of Sparta

do not mourn their sons when they go and die for their country's good. Good Venizelos [who is our Prime Minister] sent a telegram to Mavromichilena, that her son was killed, who was an officer. And she answered him that her son had done his duty. We have it in our blood, and from our tradition; our fathers came from Sparta. But have we become cowards without our knowing it?

Come close by me, Livanis. You know it well that I reared my son with love, and sent him to study medicine for my old age to be happy. And then they killed him up in Sarandiporos. I do not grudge his death, for he has freed a people! Is this the first time there have been slayings in Mani? Weren't Maniotes killed in Crete, where they went to join the guerrilla war? When they were taken from us by the party-leaders? Did we not want a Maniote as Minister to do us services, and for us to have respect? - though the Cretan is a good

man, he is a great man, and prosperity to those

294

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

who voted him to power and brought him over here to make Greece great. Listen when I tell you what the priest has told me. Our Venizelos has been asked to go and join a council in the capital of England. O Greek and Christian women, this evening at the lamp before your icon-shrine, make your children stand and let them say a prayer to the Lady Virgin to give him strength. May Archangel Michael stand close at his back, that we may not be cheated. For they are powerful men, and full of injustice.

[Murkdkena] Mourn, my dear child, and my blessing on you! You do honour to the bones of your grandfather, the captain.

But what did you say, did I not hear

[I'm an old woman, and don't hear well]

'our men have become cowards'? This is not the first time they've been in war and fighting. Why, haven't they got their Gras on the gunrack, their cruel rifles? Don't our men know how to aim and shoot and despise the Turks? If they have turned cowards, let them not come back,

not one of them come back.

But listen, Dimosthinena, these things are all lies. Our men are being slandered and insulted slyly. They're making them seem

cowards - it was written in the papers! The Prime Minister was asked, and he said it was all lies. Women, I beg of you, listen to me, for I am older than you. Send your children to the school [we've got one here] to learn to read and write. Some day the time will come for a Maniote to be senator, a Maniote to be minister, to stand up for our rights. You made me sad, my daughter, and I shall call you foolish. What is it that you said? That it's a shame and wrong to mourn for our children? No, people mourn their children, Spartan mothers mourn them and the Mavromichilenes.

Now I shall leave my mourning and look around to see the people all about me. Welcome, all of you, priests and laymen, teachers and clerks. I do not want mourning - the holy days are coming - but I will advise you. Men, who carry weapons, go away to Yinnina, and help our sons to conquer the Turks.

295

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

With this lament, the range of the genre may seem to be complete, but there are associated forms that must be mentioned. There are humorous poems in octosyllables, usually recited rather than sung, but sometimes having the conventional elements of the mock lament. The subjects include satirical comment on village immorality, and mildly improper nonsense-stories about old women. These poems seem to be associated with the women who come up from the North-East to glean in Inner Mani, but some of the more realistic satires are admitted as true Maniote products by the most austere collectors. The great pan-Hellenic ballads are rare in Mani, but one at least, The Dead Brother (The Suffolk Miracle, Child 272), has been recast in the style of the lament, to which its theme is particularly appropriate.

Even in the happiest moments of all, in the ceremonies that attend betrothal and wedding, the lament cannot be forgotten. As the procession approaches the bridegroom's village, 'the weari- ness of the long journey under the intense heat of the sun, and their familiarity with the rhythm of the laments (the only products of their native muse) so affect the singing of wedding-songs that any- one who hears it, accompanied as it is by fusillades of rifle-shots let off by the procession and the villagers who greet it, might well ask if he is watching a celebration, or a hard battle against an enemy'.4

The people may not now be as austerely humourless as they used to be in the days when a smiling face was considered a sign of weakness in a man: but feasting and dancing are still rare in Mani, and the lament holds its place as the medium of artistic expression. The great occasions are wakes and funerals; and then there are the memorial rites upon the third and fourth and eighth and fortieth days after death, upon the first anniversary, and at the third year, when the bones are dug up to take their place in the village ossuary. On All Souls' Day the cemeteries are filled with women, each at the grave of her own kin, so that the air is full of laments, twenty or thirty at the same time. Laments pass the time when men drink together, as they did at Psychik6 in 1840. Young girls grinding at the hand-mill sing laments and weep, just as Theros heard in I904. It is preparation for the time when they will have to mourn in earnest.

SA. I. KovwraAs4nrs FaljXAp ia )sea ri MivY' (Aaoypa?,a 19 (1960) I59-186).

See page 177.

296

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE

For some of the travellers' comments, see T. Spencer Fair Greece, sad relic.. London 1954, pp. 133, 223-9, etc. In modern times, P. Leigh Fermor Mani London 1958, is outstanding, and there is much of interest [at least as far as the edges of Mani are concerned] in K. Andrews The flight of Ikaros London 1959. In Greek, we have H. H. Kahovpos 'HOoypaeLKa M9v Athens 1934, and A. B.

Azlpp•rpcKoS- MeoY&KATy O NUKhAL VOL Athens I949. There is a good article by F. A. Ka dyh in the

Poivtw encyclopaedia, and a very interesting memoir of

modern travel in Mani by B. HAdLravos, serialised in the newspaper T N&'a [20o-24 February 1973]. More detailed bibliography is given in Vayakakos, below.

The standard work on the language is A. Mirambel Etude descriptive du parler maniote meridional Paris 1929, whose introduction contains much of general interest on history and customs.

There are three modern collections of Maniote laments: K. 1Hauayivrl MavLcdrTLKa topohdyta KaL 7payovt'a Athens 1928 B. E.

IH1ErpoVL•a MavLcBLKa L0oLpoodyLa Athens 1934 A. O'pos~ Td rpayo8cta -rv 'EEAAvwv, B' Athens 1952

This volume, no. 47 in the series BaarUK7 B•fLAho

I7K7), is the second half of Theros' fine anthology of Greek folk-poetry, and the great majority of his selections come from published texts. The section on Maniote laments, however, [nos. 771-784] is composed of unpublished material contributed by Theros himself and by Vayakakos.

Other texts are found in the following articles: N. I.

HoA&r• MotpoAdyta ets ErroAELriv . . . (Aaoypaela 4 (1912-13)

3-II) X. I. XpLUOALLKOS, (Aaoypabai 4 (1912-13) 670-672) T. A. MavoAKOS (Aaoypaqa 4 (1912-13) 673-680) 1. I. OlKOVOLLcKOS (Aaoypabla II (1934-37) 246-249) K. Nrac~b s To' /LavLdc7LKO ,LOLpoAdyL (NEa 'Earia 57 (no. 664)

I March 1955) K. z. A(LcLKKOS MoLpodyt• t riS Mcvr] (ARoypcbt 17 (I957-58)

179-185) [with information on male mourners]

A. B. BayLaK KOS- H A'qyopov ('E7rrS.

Aaoy. 'ApXElov, 'AK.'A8 x9 (1958)39-64)

s 297

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE LAMENTS OF MANI

This is the most scientific work on the history and variants of a lament. Much background material is cited.

A. Ka1rEaviKov, H. Kov•,p/

, A. I. KovKovAoCr~

L7c (Aaoypat a

I9 (1960-61) 379-398) Until recently, Laiphis' article was the only one to attempt detailed literary criticism. Now we have another work, which suffers from being based only on the three principal collections, but makes many acute observations:

Z. 2KorE1raE Td ,avAR1rLKa toOphoyta. Athens 1972

Sources of Poems translated

I Pasayannis 7, 2 ibid. I2, 3 ibid. 57, 4 ibid. 53, 5 ibid. 36, 6 ibid. 68, 7 ibid. 70, 8 ibid. 69, 9 ibid. Ioz, 10 ibid. IIo, i i Theros 774, I2 ibid, 782, 13 Petrunias p. 63, 14 ibid. p. 57, I5 Theros 776, i6 Petrunias p. 68, 17 Theros 771, i8 Petrunias p. 36, 19 Vayakakos p. 43, 2o Petrunias p. 43, 2I Petrunias p. 42, 22 Petrunias p. 37, 23 Petrunias p. 40, 24 Manolakos p. 677 (extract), 25 Politis p. 6

298

This content downloaded from 188.72.126.181 on Mon, 16 Jun 2014 07:20:29 AMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions