Improvement of Banana and Plantain in West and Central Africa

The International Magazine on Banana and Plantain€¦ · The International Magazine on Banana and...

Transcript of The International Magazine on Banana and Plantain€¦ · The International Magazine on Banana and...

INFOMUSAINFOMUSAThe International Magazine on Banana and Plantain

INFOMUSA is published with the support of the Technical Center for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA)

CTA

Vol. 9 N° 2December 2000

IN THIS ISSUE

Screening Musa hybrids for resistance to Radopholus similis

Variability in the root systemcharacteristics of bananaaccording to genome groupand ploidy level

A new biological nematicide to protect the roots ofmicropropagated plantain

Proposed mechanisms on how Cavendish bananas arepredisposed to Fusarium wilt during hypoxia

Soil chemical parameters and incidence and intensity of Panama disease

Intensity of black and yellowSigatoka in cv. ‘Dominico Hartón’ subjected to irradiation by 60Co

Evaluation of banana bunchtrimming (cv. ‘Valery’)

Consumer acceptability of introduced bananas in Uganda

Corm decortication method for the multiplication of banana

Preliminary evaluation ofsome banana introductions in Kerala (India)

Morphological diversity of Musa balbisiana Colla in the Philippines

MusaNews

Thesis

Books etc.

Announcements

INIBAP News

PROMUSA News

FR

UITFUL N

ET

WORKING

�

• FIFTE

EN YEARS

O

F •

�

1985

inibap

2000

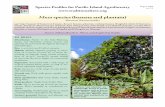

Vol. 9, N° 2Cover photo:Banana is an important staple food in Uganda(Jean-Vincent Escalant, INIBAP)Publisher: International Network for the Impro-vement of Banana and PlantainManaging editor: Claudine PicqEditorial Committee: Emile Frison, Jean-Vincent Escalant,Suzanne Sharrock, Charlotte LustyPrinted in FranceISSN 1023-0076Editorial Office: INFOMUSA, INIBAP, Parc ScientifiqueAgropolis II, 34397 Montpellier Cedex5, France. Telephone + 33-(0)4 67 6113 02; Telefax: + 33-(0)4 67 61 03 34; E-mail: [email protected] are free for developingcountries readers. Article contributionsand letters to the editor are welcomed.Articles accepted for publication may beedited for length and clarity. INFOMUSAis not responsible for unsolicited mater-ial, however, every effort will be made torespond to queries. Please allow threemonths for replies. Unless accompaniedby a copyright notice, articles appearingin INFOMUSA may be quoted or repro-duced without charge, provided ac-knowledgement is given of the source.French-language and Spanish-languageeditions of INFOMUSA are also pub-lished.To avoid missing issues of INFOMUSA,notify the editorial office at least sixweeks in advance of a change of address.

Views expressed in articles arethose of the authors and do not nec-essarily reflect those of INIBAP.

INFOMUSA Vol. 9, N° 2

CONTENTS

Screening Musa hybrids for resistance to Radopholus similis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Assessment of variability in the root system characteristics of banana(Musa spp.) according to genome group and ploidy level . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

Use of a new biological nematicide to protect the roots of plantain (Musa AAB) multiplied by micropropagation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Proposed mechanism on how Cavendish bananas are predisposedto Fusarium wilt during hypoxia . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Soil chemical parameters in relation to the incidence and intensity of Panama disease . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Intensity of black Sigatoka (Mycosphaerella fijiensis Morelet) and yellowSigatoka (Mycosphaerella musicola Leach) in Musa AAB cv. ‘Dominico hartón’ subjected to irradiation by 60Co . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Methodological consideration in ths evaluation of banana bunch trimming (Musa AAA, cv. ‘Valery‘). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Consumer acceptability of introduced bananas in Uganda. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Corm decortication method for the multiplication of banana . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26

Preliminary evaluation of some banana introductions in Kerala (India) . . . . . 27

Morphological diversity of Musa balbisiana Colla in the Philippines . . . . . . . . 28

Musa News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Thesis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Announcements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

INIBAP News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Books etc . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 40

PROMUSA News . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . I to XVI

The mission of the International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plan-tain is to sustainably increase the productivity of banana and plantain grown onsmallholdings for domestic consumption and for local and export markets.The Programme has four specific objectives:• To organize and coordinate a global research effort on banana and plantain,

aimed at the development, evaluation and dissemination of improved cultivarsand at the conservation and use of Musa diversity

• To promote and strengthen collaboration and partnerships in banana-related re-search activities at the national, regional and global levels

• To strengthen the ability of NARS to conduct research and development activitieson bananas and plantains

• To coordinate, facilitate and support the production, collection and exchange ofinformation and documentation related to banana and plantain.

INIBAP is a programme of the International Plant Genetic Resources Institute(IPGRI), a Future Harvest center.

INFOMUSAINFOMUSAThe International Magazine on Banana and Plantain

INFOMUSA is published with the support of the Technical Center for Agricultural and Rural Cooperation (CTA)

CTA

Vol. 9 N° 2December 2000

IN THIS ISSUE

Screening Musa hybrids for resistance to Radopholus similis

Variability in the root systemcharacteristics of bananaaccording to genome groupand ploidy level

A new biological nematicide to protect the roots ofmicropropagated plantain

Proposed mechanisms on how Cavendish bananas arepredisposed to Fusarium wilt during hypoxia

Soil chemical parameters and incidence and intensity of Panama disease

Intensity of black and yellowSigatoka in cv. ‘Dominico Hartón’ subjected to irradiation by 60Co

Evaluation of banana bunchtrimming (cv. ‘Valery’)

Consumer acceptability of introduced bananas in Uganda

Corm decortication method for the multiplication of banana

Preliminary evaluation ofsome banana introductions in Kerala (India)

Morphological diversity of Musa balbisiana Colla in the Philippines

MusaNews

Thesis

Books etc.

Announcements

INIBAP News

PROMUSA News

FR

UITFUL N

ET

WORKING

�

• FIFTE

EN YEARS

O

F •

�

1985

inibap

2000

Carine Dochez, Paul R. Speijer†, John Hartman†, Dirk Vuylsteke†

and Dirk De Waele

Plant parasitic nematodes are amajor constraint to sustainableMusa production (Stover and

Simmonds 1987). In Uganda, which isthe world‘s largest producer of EastAfrican highland bananas (Musa spp.,AAA group) (Lescot 1998), nematodeshave been identified as a major factorcontributing to declining production(Speijer et al. 1999). The most destruc-tive nematode attacking bananas in thetropics is Radopholus similis (Cobb)Thorne (Gowen 1993), which was ac-cordingly used as the test species inthis screening procedure.

Nematodes can be controlled withchemicals, but these may have adverseenvironmental effects and the use ofnematicides is too expensive and theproducts too dangerous for subsistencefarmers. Breeding for host plant resis-tance is a promising strategy for con-trolling nematodes (Speijer and DeWaele 1997). However, screening newhybrids in the field is very time- andspace-consuming. Therefore, an earlyand rapid method for screening bananagermplasm for nematode resistance,based on inoculation of individual roots,was used (De Schutter et al., in prepa-ration).

Materials and methodsScreen-house experiments were estab-lished in Central Uganda at the Easternand Southern Africa Regional Centre ofthe International Institute of TropicalAgriculture (IITA-ESARC), SendusuFarm, Namulonge. The station is at analtitude of 1150 m asl and is represen-tative for the East African highland ba-nanas.

Tested cultivars included the refer-ence cultivars Yangambi km 5 (MusaAAA group), which is highly resistant toRadopholus similis , Gros Michel(Musa AAA, partially resistant to R.similis) and Valery (Musa AAA, suscep-tible to R. similis).

Several hybrids were selected by theIITA-ESARC breeding programme fortesting, including: the plantain deriveddiploid hybrids TMP2x 2521S-31,TMP2x-47, and TMP2x-50; the bananaderived diploid hybrids TMB2x 1411S-2,

TMB2x 1411S-10, TMB2x 2559S-1 andTMB2x 2559S-2; the ‘Pisang Awak’ de-rived tetraploid hybrid TMBx 2094S-1;and the East African Highland Bananaderived tetraploid hybrid TMHx 660K-1.

Nematode inoculum was obtainedfrom carrot (Daucus carota L.) disccultures (Pinochet et al. 1995). Carrotswere surface-sterilized by sprayingthem with 96% ethanol followed byflaming, peeled, cut in discs (3 mmthick) and placed in 35 mm-diameterPetri dishes. Nematodes were surface-sterilized with aqueous streptomycinsulphate (2000 ppm) for 6 hours fol-lowed by three rinses with sterile dis-tilled water. About 100 nematodes, in10 µl of water, were placed on each car-rot disc. The Petri dishes were sealedwith parafilm and incubated at 28°C inthe dark. Nematodes were sub-culturedonto fresh carrots every 5 to 7 weeks.Inoculum was prepared by rinsing thePetri dishes containing the carrot discswith sterile distilled water and collect-ing the nematodes in a test tube.

All Musa genotypes were planted inwooden boxes containing steam-steril-ized sawdust. Each box contained 9suckers, which were pared and hotwater-treated (Colbran 1967). Fourweeks after planting, three roots wereselected from each sucker. Every se-lected root was carefully excavated andat a distance of 5 cm from the rhizome,a small plastic container was placedaround the root. Inoculation was doneby pouring a suspension of 50 femalesof R. similis on each individual root.

The root and plastic container werethen covered with steam-sterilizedsand. Eight weeks after inoculation, theinoculated roots were harvested.

The harvested roots were washed andmacerated in a blender for 10 seconds.Nematodes were extracted overnightusing a modified Baermann funneltechnique (Hooper 1990). Nematodeswere concentrated by collecting themon a 20 mm sieve. All vermiform devel-opmental stages and sexes werecounted. For each cultivar the repro-duction ratio (final population/initialpopulation) of R. similis was calcu-lated. Orthogonal contrasts (SAS 1997)of the test materials to the referencecultivars Yangambi km 5 and Valerywere run to compare the mean repro-duction ratios.

Results and discussionTable 1 shows the reproduction ratio ofR. similis on the different cultivars,while Table 2 shows the orthogonal con-trasts between the test cultivars andthe resistant and susceptible checks.The nematodes on all the other culti-vars showed a lower reproduction ratiothan on Valery (Tables 1 and 2). Thegenotypes Gros Michel, TMP2x 2521S-31 and 47, TMB2x 1411S-10, TMBx2094S-1, TMHx 660K-1 and TMB2x2569S-2 supported a reproduction ratiothat was not significantly different fromthat on Yangambi km 5. Genotypes witha reproduction ratio not statisticallydifferent from Yangambi Km5 supportlow densities and are therefore promis-

INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2 3

Screening Musa hybrids for resistance to Radopholus similis

Genetic resources Early tests for selection

Table 1. Reproduction ratio of Radopholus similis on individual roots of 12 Musagenotypes, 8 weeks after inoculation with a suspension containing 50 females of R. similis

Genotype Parents Pf Rr1 = Pf2/Pi3

Yangambi km5 1 0.02

Gros Michel 82 1.64

Valery 883 17.66

TMB2x 1411S-2* TMB2x 7197-2 x TMB2x 9839-1 427 8.54

TMB2x 1411S-10* TMB2x 7197-2 x TMB2x 9839-1 10 0.20

TMB2x 2569S-1* TMB2x 7197-2 x TMB2x 9128-3 2 0.04

TMB2x 2569S-2* TMB2x 7197-2 x TMB2x 9128-3 491 9.82

TMBx 2094S-1* Kayinja x TMB2x 7197-2 73 1.46

TMP2x 2521S-31* TMP2x 1518 x TMB2x 8075-3 66 1.32

TMP2x 2521S-47* TMP2x 1518 x TMB2x 8075-3 60 1.20

TMP2x 2521S-50* TMP2x 1518 x TMB2x 8075-3 0.3 0.006

TMHx 660K-1 Enzirabahima x Calcutta 4 99 1.981 Rr = Reproduction ratio (final population/initial population).2 Pf = Final population including all vermiform stages and sexes.3 Pi = Initial population, 50 females of R. similis.

* Hybrids with Pisang Jari Buaya in their pedigree.

ing genotypes for further evaluation.Except for the hybrid TMHx 660K-1, allthe other hybrids have Pisang JariBuaya (Musa AA) in their pedigree,which is highly resistant to R. similis(Pinochet 1988).

AcknowledgementsFinancial support by the Flemish Asso-ciation for Development Cooperationand Technical Assistance (VVOB) andby the Belgian Administration for De-velopment Cooperation (BADC) isgratefully acknowledged. The authorswish to thank Mrs Pamela Mpirirwe andMs Christine Kajumba for technical as-sistance. This is IITA manuscript num-ber IITA/00/JA/29. ■

ReferencesColbran R.C. 1967. Hot water tank for treatment of

banana planting material. Queensland Depart-ment of Primary Industries, Brisbane. Advisoryleaflets Division of Plant Industry 9(24): 4.

De Schutter B., P.R. Speijer, C. Dochez, A. Ten-kouano & D. De Waele. (in preparation). Scree-ning of Musa germplasm for resistance to nema-todes by inoculating individual roots.

Gowen S.R. 1993. Yield losses caused by nematodeson different banana varieties and some manage-ment techniques appropriate for farmers inAfrica. Pp. 199-208 in Biological and integratedcontrol of highland banana and plantain pestsand diseases. Proceedings of a research coordi-nation meeting. Cotonou, Bénin, 12-14 November1991 (C.S. Gold & B. Gemmill, eds.). Internatio-nal Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan, Ni-geria.

Hooper D.J. 1990. Extraction and processing ofplant soil nematodes. Pp. 137-180 in Plant para-sitic nematodes in subtropical and tropical agri-culture (M. Luc, R.A. Sikora & J. Bridge, eds).CAB International, Wallingford, UK.

Lescot T. 1998. Banana. Little-known wealth of va-riety. Fruitrop 51: 8-11.

Pinochet J. 1988. Comments on the difficulty inbreeding bananas and plantains for resistance tonematodes. Revue de Nématologie 11(1): 3-5.

Pinochet J., C. Fernandez & J.L. Sarah. 1995. In-fluence of temperature on in vitro reproductionof Pratylenchus coffeae, P. goodeyi and Rado-pholus similis. Fundamental and Applied Nema-tology 18(4): 391-392.

SAS. 1997. SAS guide for personal computers. 6thed. SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA.

Speijer P.R. & D. De Waele. 1997. Screening ofMusa germplasm for resistance and tolerance tonematodes. INIBAP Technical Guidelines 1. In-ternational Plant Genetic Resources Institute,Rome, Italy; International Network for the Im-provement of Banana and Plantain, Montpellier,France; ACP-EU Technical Centre for Agricultu-ral and Rural Cooperation, Wageningen, The Ne-therlands. 47 p.

Speijer P.R., C. Kajumba & F. Ssango. 1999. EastAfrican highland banana production as influen-

ced by nematodes and crop management inUganda. International Journal of Pest Manage-ment 45: 41-49.

Stover R.H. & N.W. Simmonds. 1987. Banana. 3rd ed. Longman Scientific and Technical, London, UK.

This work was carried out by Carine Dochez, Paul R.Speijer, John Hartman and Dirk Vuylsteke fromthe International Institute of Tropical Agriculture–Eas-tern and Southern Africa Regional Centre (IITA-ESARC), PO Box 7878, Kampala, Uganda, and DirkDe Waele from the Laboratory of Tropical Crop Im-provement, Catholic University of Leuven (KUL), Kas-teelpark Arenberg 13, 3001 Leuven, Belgium.

4 INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2

Table 2. Orthogonal contrasts between Yangambi km 5 (R. similis-resistant), Valery(R. similis-susceptible) and the other cultivars.

Cultivars Contrast with Yangambi km5 Contrast with Valery

Yangambi km5 ***

Gros Michel Ns ***

Valery ***

TMB2x 1411S-2 ** **

TMB2x 1411S-10 Ns ***

TMB2x 2569S-1 ** **

TMB2x 2569S-2 Ns ***

TMBx 2094S-1 Ns ***

TMP2x 2521S-31 Ns ***

TMP2x 2521S-47 Ns ***

TMP2x 2521S-50 * ***

TMHx 660K-1 Ns ***Ns = Contrast not significant at P > 0.05.

*** Contrast significant at P = 0.001.

** Contrast significant at P = 0.01.

* Contrast significant at P = 0.05.

G. Blomme, R. Swennen and A. Tenkouano

Genetic improvement in root traitsof crop species requires knowl-edge of intraspecies variability in

root characteristics (O’Toole and Bland1987). Genotypic differences in rootsize have been reported for maize (Zeamays L.) (Pan et al. 1985, Aina and

Fapohunda 1986, Mackay and Barber1986), barley (Hordeum vulgare L.)(Hackett, 1968), wheat (Triticum aes-tivum L.) (Hurd 1968), tomatoes (Ly-copersicon esculentum Mill.) andbeans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) (Zobel1975), rice (Oryza sativa L.) (Nicou etal . 1970, Reyniers et al . 1975,Ekanayake et al. 1985a, 1985b) and sev-eral other species (O’Toole and Band1987).

Genotypic differences in Musa spp.root traits have been investigated underhydroponic conditions (Swennen 1984,Swennen et al. 1986) with the conclu-sion that dessert bananas had a largerroot system than plantains. In a similarstudy, genotypic differences in lateralroot initiation were also observed(Draye et al. 1999).

Ploidy level may influence the size ofdifferent plant parts in Musa species

Assessment of variability in the root systemcharacteristics of banana (Musa spp.) according to genome group and ploidy level

Physiology Influence of ploidy

(Simmonds 1962 and 1966, Vandenhoutet al. 1995), but no systematic study onthe effect of ploidy level and genomegroup on root traits of field grownplants has been carried out.

The objective of this study was to as-sess the relative contribution of ploidystatus and genome composition to thevariability of root traits in Musa.

Materials and methodsThis study was carried out at the IITAHigh Rainfall station at Onne in south-eastern Nigeria (4°42’ N, 7°10’ E, 5masl). Its soil is an ultisol derived fromcoastal sediments, well drained butpoor in nutrients and with a pH of 4.3 in1:1 H2O. The average annual rainfall is2,400 mm distributed monomodallyfrom February until November. Detailsof the site have been described by Ortizet al. (1997).

Eighteen genotypes (Table 1) belong-ing to 5 genomic groups and 3 ploidy

levels of banana and plantain (Musaspp.) were assessed at flower emer-gence. In vitro-derived plants were pro-duced following standard shoot-tip cul-ture techniques (Vuylsteke 1989,Vuylsteke 1998). Rooted plantlets weretransferred to polybags (height = 25cm, circumference = 44 cm) in a green-house nursery (Vuylsteke and Talengera1998, Vuylsteke 1998) and transplantedto the field during June 1996, six weeksafter acclimatization.

The trial site, which had been undergrass fallow for a period of 8 years, wasmanually prepared in order to avoid soildisturbance. Plants were fertilized withmuriate of potassium (a.i. K20, 60% K)at a rate of 600 g plant-1 year-1, andUrea (47% N) at a rate of 300 g plant-1

year-1, split over 6 equal applicationsduring the rainy season. No mulch wasapplied. The experimental area wastreated with the nematicide Nemacur(a.i. fenamiphos) at a rate of 15 g plant-

1 (3 treatments year-1) to reduce nema-tode infestation. The fungicide Bayfidan(a.i. triadimenol) was applied threetimes per year at a rate of 3.6 ml plant-1

to control the leaf spot disease blacksigatoka (Mycosphaerella fijiensisMorelet). Plants were irrigated duringthe dry season at a rate of 100 mmmonth-1.

The field layout was a randomizedcomplete block design with two replica-tions of two plants per genotype. Toavoid overlapping of adjacent root sys-tems, plant spacing was 4 m x 4 m. Theplants were completely excavated andthe characteristics measured includedplant height (PH, cm), number ofleaves (NL), pseudostem circumferenceat soil level (PC, cm) and height of thetallest sucker (HS, cm). In addition,leaf area (LA, cm2) was calculated ac-cording to Obiefuna and Ndubizu(1979). Corm characteristics measuredwere fresh corm weight (CW, g), cormheight (CH, cm) and widest width ofthe corm (WW, cm). The number ofsuckers (NS) on the corm werecounted. Root characteristics includedthe number of adventitious roots orcord roots (NR), root dry weight (DR, g)and the average basal diameter of thecord roots (AD, mm) measured with aVernier Calliper. The cord root length(LR, cm) was measured using the lineintersect method (Newman 1966, Ten-nant 1975). Other root system charac-teristics were total dry weight (TD, g)of the mat (i.e. plant crop and suckers)and total cord root length of the mat(TL, cm). Aerial growth, corm develop-ment and root system growth character-istics were also measured for the tallestsucker.

Statistical analysis was carried outusing the SAS statistical package (SAS,1989). Variability of the differentgrowth characteristics was assessedusing PROC GLM in SAS. Total pheno-

INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2 5

Table 1. Name, genome, ploidy level, type and suckering behaviour of thegenotypes assessed in this study.

Name Genome Ploidy level Type Suckering

Niyarma Yik AA 2 Musa acuminata banksii Non regulated

Calcutta 4 AA 2 Musa acuminata burmannica Non regulated

Pahang AA 2 Musa acuminata malaccensis Non regulated

Pisang J. Buaya AA 2 Musa acuminata microcarpa Non regulated

Pisang Madu AA 2 Musa acuminata microcarpa Non regulated

Tjau Lagada AA 2 Musa acuminata microcarpa Non regulated

Yangambi km5 AAA 3 Dessert banana Regulated

Valery AAA 3 Dessert banana Regulated

Obino l’Ewai AAB 3 Plantain Inhibited

Agbagba AAB 3 Plantain Inhibited

Pelipita ABB 3 Cooking banana Regulated

Cardaba ABB 3 Cooking banana Regulated

Fougamou ABB 3 Cooking banana Regulated

TMPx 2796-5 AAB x AA 4 Plantain hybrid (Bobby Tannap x Pisang lilin) Regulated

TMPx 7152-2 AAB x AA 4 Plantain hybrid (Mbi Egome 1 x Calcutta 4) Regulated

TMPx 548-9 AAB x AA 4 Plantain hybrid (Obino l’Ewai x Calcutta 4) Regulated

TMPx 5511-2 AAB x AA 4 Plantain hybrid (Obino l’Ewai x Calcutta 4) Inhibited

TMPx 1658-4 AAB x AA 4 Plantain hybrid (Obino l’Ewai x Pisang lilin) Regulated

Table 2. Mean square and significance tests of different quantitative traits of plants at flower emergence.

Trait#

Source of variation Df LA PH CW NS HS DR NR

Replication 1 1017416013 392 2737103 1 2088 15212 201

Ploidy level 2 7547029458*** 5680*** 12051416*** 41** 28298*** 93565*** 20537***

Genome group 2 2608843147** 6364*** 11752654*** 65*** 7595* 45845*** 8463**

Genotype 13 2106141878*** 3575*** 8429250*** 33*** 10571*** 18524*** 2874*

Residual 50 363318642 321 1109510 6 1526 4442 1330

LR AD TD TL % MPDR % MPLR DTFL

Replication 1 4563021 0,04 24291 9812 12 198 1197

Ploidy level 2 53138430*** 7,83** 18217 54977396 4497*** 3503*** 48142***

Genome group 2 4179499 1,49** 62806 34364239 1090*** 1217*** 2297

Genotype 13 10764435* 0,38* 128050***133333288*** 404** 287* 10774***

Residual 50 4845881 0,19 23054 38834528 134 146 1741#: Df: degrees of freedom; LA: leaf area (m2); PH: plant height (cm); CW: corm weight (g); NS: number of suckers; HS: height of the tallest sucker (cm); DR: root dry weight (g); NR: number of cordroots; LR: cord root length (cm); AD: average basal cord root diameter (mm); TD: total root dry weight of the mat (g); TL: total length of the cord roots of the mat (cm); %MPDR: percentage root dryweight of the plant crop to the mat; %MPLR: percentage cord root length of the plant crop to the mat; DTFL: days to flower emergence.

*, **, *** Significant at P < 0.05, 0.01 and 0.001, respectively.

typic variance was partitioned accord-ing to the following sources of variation:replication, ploidy level, genome groupand genotype.

Results and discussionThere was a significant effect of ploidylevel on the different characteristics,except for root dry weight and cord rootlength of the mat (Table 2). Generally,with increasing ploidy level the magni-tude of plant characteristics tends toincrease. For example, the tetraploidshad the highest values for leaf area,plant height, corm fresh weight, plantcrop root traits and their respectivedaily growth rates (Table 3). The effectof genotype was significant for all as-sessed traits, while the effect ofgenome group was significant for allshoot and several root traits.

Simmonds (1962) reported also thatfruit sizes increased with increasingploidy levels, while Vandenhout et al.(1995) noted the same for the stomatasize. Apparently the increased chromo-some number resulted in larger cellscausing an increase in the size of theplant organs. Vakili (1967) reportedthat colchicine derived tetraploids fromM. balbisiana were taller and more ro-

bust but had slower growth rate, fewersuckers and scantier root systems thandiploids. Contrary to these observa-tions, higher daily growth rates andlarger plant crop root systems were ob-served with increasing ploidy level inthis study (Table 3). Cord root diameterincreased with higher ploidy level(Table 3) confirming observations madeby Monnet and Charpentier (1965).

There was an increase in sucker de-velopment with decreasing ploidy level.All diploid bananas had a non-regulat-ing suckering behaviour (i.e. all suckersgrow vigorously) resulting in a faster cy-cling, while the studied triploids andtetraploids had a regulated (i.e. 2 or 3suckers grow vigorously) or an inhibitedsuckering (i.e. no sucker grows vigor-ously) (Table 1). For example, the plantcrop accounted for only 45% of the rootdry weight of the mat for the diploid ba-nanas indicating a strong suckergrowth. Conversely, the plantains, thecooking bananas and the tetraploidplantain hybrids had more than 60% ofthe root system accounted for by theplant crop.

Blomme and Ortiz (1996) reportedsignificant positive correlation betweenroot and shoot growth characteristics

during the vegetative stage, indicatingthat vigorously growing plants also hadlarger root systems. In this study therewas a clear relationship between shootand root growth according to genomegroup. For example, diploids (AAgenomes) and dessert bananas (AAA)had low values for most root and shootgrowth characteristics, while plantains(AAB), cooking bananas (ABB) andtetraploid plantain hybrids (AAAB) hadhigher values (Tables 3 and 4). The lowvalues for shoot and root traits of thedessert banana group is probably due tothe inclusion of the semi-dwarf variety‘Valery’.

In this study, there was a tendency ofincreased shoot and root vigor for thehigher ploidy levels. Conversely, suckerdevelopment and thus perenniality wasenhanced with decreasing ploidy level.

AcknowledgementsFinancial support by the Flemish Asso-ciation for Development Cooperationand Technical Assistance (V.V.O.B.:Vlaamse Vereniging voor Ontwikkel-ingssamenwerking en Technische Bijs-tand) and the Directorate General forInternational Cooperation (DGIC, Bel-gium) is gratefully acknowledged. Theauthors thank Miss Lynda Onyeukwufor helping with the data collection. ■

ReferencesAina P.O.& H.O. Fapohunda. 1986. Plant Soil 94:

257-265.Blomme G. & R. Ortiz. 1996. Preliminary evaluation

of variability in Musa root system development.Pp. 51-52. In Biology of root formation and deve-lopment (A. Altman ed.). Plenum PublishingCompany, New York.

Draye X., B. Delvaux & R. Swennen. 1999. Distribu-tion of lateral root primordia in root tips ofMusa. Annals of Botany 84: 393-400.

Ekanayake I.J., D.P. Garrity, T.M. Masajo & J.C.O’Toole. 1985b. Root pulling resistance in rice:Inheritance and association with drought resis-tance. Euphytica 34: 903-913.

Ekanayake I.J., J.C. O’Toole, D.P. Garrity & T.M.Masajo. 1985a. Inheritance of root charactersand their relations to drought resistance in rice.Crop. Sci. 25: 927-933.

Hackett C. 1968. A study of the root system of Bar-ley. I. Effects of nutrition on two varieties. NewPhytol. 67: 287-299.

Hurd E.A. 1968. Growth of roots of seven varieties ofspring wheat at high and low moisture levels.Agron. J. 60: 201-205.

Mackay A.D. & S.A. Barber. 1986 Effect of nitrogenon root growth of two corn genotypes in the field.Agron. J. 78: 699-703.

Monnet J. & J.M. Charpentier. 1965. Le diamètredes racines adventives primaires des bananiersen fonction de leur degré de polyploïdie. Fruits20: 171-173.

6 INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2

Table 3. Musa spp. growth characteristics at flower emergence according to ploidylevel.

Ploidy level

Trait# 2 3 4

LA 92 635 ± 6 617 78 968 ± 5 290 115 547 ± 5 366

NL 13 ± 0,4 10 ± 0,6 14 ± 0,5

PH 228 ± 8 248 ± 7 260 ± 5

PC 53 ± 2 63 ± 2 63 ± 1

CW 4 135 ± 444 5 312 ± 274 5 498 ± 344

CH 24 ± 1 22 ± 1 20 ± 1

WW 16 ± 1 20 ± 1 21 ± 1

NS 13 ± 1 11 ± 1 10 ± 0,5

HS 161 ± 15 141 ± 12 90 ± 8

DR 212 ± 15 281 ± 22 343 ± 19

NR 122 ± 9 162 ± 9 182 ± 9

LR 5 807 ± 571 6 136 ± 365 8 707 ± 618

AD 4,53 ± 0,13 5,34 ± 0,11 5,70 ± 0,07

TD 533 ± 59 513 ± 33 475 ± 31

TL 15 236 ± 2 173 12 468 ± 1 064 12 760 ± 1 098

% MPDR 45 ± 3 56 ± 3 74 ± 2

% MPLR 46 ± 3 53 ± 3 71 ± 3

DTFL 381 ± 16 348 ± 12 288 ± 6

LA/DTFL 242 ± 14 237 ± 19 406 ± 22

PH/DTFL 0,61 ± 0,02 0,73 ± 0,03 0,91 ± 0,02

CW/DTFL 11 ± 1 16 ± 1 19 ± 1

HS/DTFL 0,44 ± 0,04 0,41 ± 0,04 0,31 ± 0,03

DR/DTFL 0,56 ± 0,04 0,84 ± 0,08 1,21 ± 0,07

NR/DTFL 0,32 ± 0,02 0,49 ± 0,04 0,64 ± 0,04

LR/DTFL 15 ± 1 18 ± 1 31 ± 2

TD/DTFL 1,39 ± 0,13 1,50 ± 0,10 1,67 ± 0,12

TL/DTFL 39 ± 5 36 ± 3 45 ± 4#: see Table 1; NL: number of leaves; PC: pseudostem circumference (cm); CH: corm height (cm); WW: corm widest width (cm).

Newman E.I. 1966. A method of estimating the totallength of root in a sample. J. Appl. Ecol. 3: 139-145.

Nicou R., L. Seguy & G. Haddad. 1970. Comparaisonde l’enracinement de quatre variétés de riz plu-vial en présence ou absence de travail du sol.L’Agronomie tropicale 25: 639-659.

Obiefuna J.C. & T.O.C. Ndubizu. 1979. Estimatingleaf area of plantain. Sci. Hortic. 11: 31-36.

Ortiz R., P.D. Austin & D. Vuylsteke. 1997. IITA highrainfall station: Twenty years of research for sus-tainable agriculture in the West African HumidForest. HortScience 32(6): 969-972.

O’Toole J.C. & W.L. Bland. 1987. Genotypic varia-tion in crop plant root systems. Adv. Agron. 41:91-145.

Pan W.L., W.A. Jackson & R.H. Moll. 1985. J. Exp.Bot. 36: 1341-1351.

Reyniers F.N., J.M. Kalms & J. Ridders. 1975. Etudedu comportement de deux types de variétés deriz selon leur alimentation hydrique. I. Etude desfacteurs permettant d’esquiver la sécheresse.Rapp. Inst. rech. agron. trop. (IRAT), Côted’Ivoire.

SAS Institute, Inc. 1989. SAS/STAT user’s guide,version 6, 4th ed., Vol. 1. Cary, N.C.: SAS InstituteInc.

Simmonds N.W. 1962. The evolution of bananas.Longman. London.

Simmonds N.W. 1966. Bananas. Tropical AgricultureSeries, Longman, London.

Swennen R. 1984. A physiological study of the suc-kering behaviour in plantain (Musa cv. AAB).Ph. D. thesis, Dissertationes de Agriculturan°132, Faculty of Agriculture, Katholieke Univer-siteit Leuven, 180 pp.

Swennen R., E.A. De Langhe, J. Janssen & D. Deco-ene. 1986. Study of the root development of someMusa cultivars in hydroponics. Fruits 41: 515-524.

Tennant D. 1975. A test of a modified line intersectmethod of estimating root length. J. Ecol. 63:995-1001.

Vakili N.G. 1967. The experimental formation of po-lyploidy and its effects in the genus Musa Am. J.Bot. 54: 24-36.

Vandenhout H., R. Ortiz, D. Vuylsteke, R. Swennen& K.V. Bai. 1995. Effect of ploidy on stomatal andother quantitative traits in plantain and bananahybrids. Euphytica 83: 117-122.

Vuylsteke D. 1989. Shoot-tip culture for the propa-gation, conservation, and exchange of Musagermplasm. Practical manuals for handling cropgermplasm in vitro 2. International Board forPlant Genetic Resources, Rome. 56 pp.

Vuylsteke D. 1998. Shoot-tip culture for the propa-gation, conservation, and distribution of Musagermplasm. International Institute of TropicalAgriculture, Ibadan, Nigeria. 82 pp.

Vuylsteke D. & D. Talengera. 1998. Postflask Mana-gement of Micropropagated Bananas and Plan-tains. A manual on how to handle tissue-cultu-

red banana and plantain plants. InternationalInstitute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan, Nige-ria. 15 pp.

Zobel R.W. 1975. The genetics of root development.Pp. 261-275 in The development and function ofroots (G. Torrey & D.C. Clarkson, eds.). Acade-mic Press. London and New York.

G. Blomme* and A. Tenkouano work at the CropImprovement Division, International Institute of Tropi-cal Agriculture (IITA), Onne High Rainfall Station, L.W. Lambourn & Co. Carolyn House, 26 DingwallRoad, Croydon, CR9 3EE, England and R. Swennenat the Laboratory of Tropical Crop Improvement, Ca-tholic University of Leuven (K.U.Leuven), KasteelparkArenberg 13, 3001 Leuven, Belgium.* Guy Blomme is currently working in Kampala,Uganda as the INIBAP assistant regional coordinatorfor East and Southern Africa.

INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2 7

Table 4. Musa growth characteristics at flower emergence for the triploid genome groups

Genome group

Trait # AAA AAB ABB

LA 58 208 ± 9 730 92 365 ± 5 888 85 513 ± 7 710

NL 8 ± 1 11 ± 0,5 12 ± 0,9

PH 215 ± 11 257 ± 8 268 ± 8

PC 55 ± 2 62 ± 1 69 ± 2

CW 3 945 ± 354 6 285 ± 290 5 662 ± 369

CH 23 ± 2 22 ± 1 22 ± 1

WW 17 ± 1 22 ± 1 20 ± 1

NS 14 ± 1 13 ± 1 8 ± 1

HS 165 ± 23 106 ± 10 150 ± 22

DR 220 ± 30 254 ± 31 361 ± 39

NR 135 ± 10 151 ± 9 195 ± 16

LR 5 285 ± 793 6 465 ± 397 6 599 ± 618

AD 4.9 ± 0.1 5.8 ± 0.2 5.3 ± 0.1

TD 556 ± 81 409 ± 18 567 ± 45

TL 14 883 ± 2 647 11 278 ± 1 358 11 379 ± 1 266

% MPDR 43 ± 5 62 ± 7 64 ± 4

% MPLR 39 ± 5 61 ± 5 60 ± 5

DTFL 368 ± 24 338 ± 9 340 ± 25

LA/DTFL 168 ± 35 276 ± 20 264 ± 32

PH/DTFL 0.61 ± 0.06 0.77 ± 0.04 0.82 ± 0.06

CW/DTFL 11 ± 1 19 ± 1 17 ± 2

HS/DTFL 0.45 ± 0.06 0.32 ± 0.03 0.46 ± 0.07

DR/DTFL 0.60 ± 0.07 0.77 ± 0.11 1.13 ± 0.15

NR/DTFL 0.38 ± 0.05 0.45 ± 0.03 0.61 ± 0.08

LR/DTFL 15 ± 2 19 ± 1 20 ± 2

TD/DTFL 1.50 ± 0.19 1.21 ± 0.05 1.75 ± 0.17

TL/DTFL 40 ± 7 33 ± 3 34 ± 3#: see Tables 2 and 3.

Lazaro L. Castellanos Lopez, JorgeLopez Torrez, Julian Gonzalez

Rodriguez. Sergio Rodriguez Moralesand José De La C. Ventura Martín

The cultivation of bananas andplantains represents substantialfood and economic resources for a

large proportion of the world’s popula-tion, mainly in the developing countriesin Asia, Africa and Latin America. Al-though conventional propagation meth-ods are still used in many of these coun-tries, micropropagation has gainedpopularity in recent years as an innova-tive alternative in multiplication.

Indeed, in vitro culture makes it pos-sible to produce disease and pest-freeplants for transfer to the field. However,the plants are still very delicate attransplantation, making them suscepti-ble to plant parasitic nematodes, whichsometimes cause considerable yieldlosses, as in the case of Meloydoginespp. These losses can be almost com-pletely eliminated if the soil is disin-fected before planting or if planting isperformed in nematode-free soil. How-ever, this is not very easy to achieve. Onthe one hand, the application of chemi-cal nematicides considerably affectsthe production process and destroys theecological balance of the soil, and onthe other hand the methods for the de-tection of nematodes in the soil are nottotally reliable. Nematodes are practi-

cally impossible to detect when the soilpest population is very small. As a re-sult, farmers may be inclined to use in-fested land that appears to be com-pletely free of nematodes andconsidered unworthy of nematicide ap-plication. However, as months go by, itwill be seen that nematode populationsare indeed present and that the de-fenceless roots of the plantlets are ei-ther practically non-existent or are cov-ered with thick nodules.

The use of nematode-trapping fungibelonging to different genera such asHarposporium sp., Dactylella spp.,Stylopage sp., Dactylaria spp., Cate-naria sp. and Arthrobotrys sp. (Dud-dington 1956, Cortado 1968, Generalao1986, Stirling 1988, Persson 1997) ap-pears to be a promising alternative foraddressing this problem.

These organisms have several kindsof advantage in the biological control ofnematodes, including:• their ability to trap and eliminate a

large number of nematode speciesusing specialized capture structuresor organs to trap moving parasites(loops, contractile or not; nets; stickystructures and other methods). Thisis a particularly interesting feature ascontrol is thus performed before thenematode penetrates the root andcauses damage there;

• their biological cycle involves twophases: 1) a saprophytic phase duringwhich they use only the soil organic

matter as a source of carbon (energy)and aminoacids (nitrogen), and 2) aparasite phase during which theyfeed only on the organic matter ofcaptured nematodes (Stirling 1988,Persson 1997). It has been observedthat in the presence of nematodesthey are capable of changing rapidlyfrom the saprophytic to the parasitephase and that this also triggersspore germination and the develop-ment of capture organs;

• their ability to produce substancesthat attract the parasites; this furtherincreases their control effectivenesswith regard to the latter;

• some of these fungi release a largequantity of resistance spores, makingit possible to formulate them in dif-ferent ways.INIVIT maintains a stock of nemato-

phagous and/or nematode parasitefungi isolated from Cuban soils plantedwith banana and plantain. Many havealready been characterized and havedisplayed considerable pathogenicitywith regard to the main nematodespecies infecting Cuban banana crops.

The introduction of nematophagousfungi in the rhizosphere of tissue cul-ture plants would make it possible toreduce or eliminate production losses,to reduce the costs involved in the useof chemicals and to conserve soils,since the protection of the roots ofplantlets would be achieved in a nat-ural and ecological manner. This wasthe reason for undertaking research onthe strain INIVIT 99-1 TPB of Arthro-botrys sp. with regard to protection ofthe roots of CEMSA 3/4 plantain(MusaAAB) multiplied by micropropagation.

Material and methodsThe research was conducted at INIVITin the tissue culture plant weaningzone in 1999.

In vitro plants of the CEMSA 3/4plantain clone (Musa spp. AAB) wereused and the work concerned only theadaptation phase. The treatments arelisted as A = control, B = biological ne-maticide + Radopholus similis inocu-lum, C = R. similis inoculum and D =biological nematicide only.

Micropropagated plants ready forweaning were used. They were plantedin pots containing sterilized substrate

8 INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2

Figure 1. Effect of the biological nematicide for the protection of roots of micropropagated plantain.

0% p

aras

itis

m

A.ControlB. Biological nematicide + R. similisC. R. SimilisD. Biological nematicide

80

60

40

20

0

A B C D

Use of a new biological nematicide to protect the roots of plantain (Musa AAB) multiplied bymicropropagation

Biological control A nematophagous fungi

prepared from red soil, compost andbagasse. Ten days after planting, treat-ments B and D were inoculated withnematicide. After five days, each pot oftreatments B and C received a suspen-sion of 5 x 103 nematodes (R. similis)prepared by tissue culture on slices ofcarrot (Daucus carota). The percent-age of root infection, total weight, rootweight and the height of each tissueculture plant were measured 60 dayslater.

Results and discussionUnlike treatment C, treatments B and Ddid not display significant differenceswith regard to the control treatment Afor all the parameters evaluated (Fig-ure 1). This shows that when biologicalcontrol is present, R. similis does notcause serious damage to in vitro plantroots. These results confirm those re-ported for other biological nematicides(Jatala 1986, Davide1994) used to pro-tect the roots of other crops.

The plants to which the nematicideonly had been applied displayed greaterheight and weight than those of theother treatments; significant differ-ences were very small for the controland treatment B but high for treatmentC (Table 1).

The greater height and root weight ofthe in vitro plants on which the strainINIVIT 99-1 TPB was introduced may re-sult from the fact that this organismcontributes to the decomposition of or-ganic matter and releases nutrients intothe soil that can then be taken up by thein vitro plants, which is not the case inthe treatments not including microor-ganisms. It is also possible that the or-ganisms produce substances that stimu-

late plant growth, as occurs in other soilmicroorganisms (Davide 1994).

Conclusions and recommendationsThe use of biological nematicide (CepaINIVIT 99-1 TPB de Arthrobotrys sp.)effectively protects the roots of CEMSA3/4 plantain in vitro plants from attackby R. similis.

When it is used during the adaptationphase, INIVIT 99-1 TPB combined withcompost and bagasse increases theheight and weight of CEMSA 3/4 tissueculture plants.

Use of the new biological nematicideINIVIT 99–1 TPB is recommended forthe protection of the roots of plantainin vitro plants.

It is recommended that the efficacyof the nematicide should be tested onother banana and plantain clones sus-ceptible to plant nematode attacks.

It is recommended that the efficacyof the nematicide should be tested onother nematode species of great eco-nomic importance, such as Meloy-dogine spp., Pratylenchus coffeae andHelicotylenchus multicinctus. ■

ReferencesCortado R & R.G. Davide. 1968. Nematode-trapping

fungi in the Philippines (abstr). Phil. Phytopath.4: 4.

Davide R.G. 1994. Biological control of banana ne-matodes: development of BIOCON I (BIOACT)

and BIOCON II technologies. Pp. 139-146 in Ba-nana nematodes and weevil borers in Asia andthe Pacific. Proceedings of a conference-work-shop on nematodes and weevil borers affectingbananas in Asia and the Pacific. 18-22 April 1994,Serdang, Malaysia (R.V. Valmayor, R.G. Davide,J.M. Stanton, N.L. Treverrow and V.N. Roa, eds.).ASPNET Book Series 5. INIBAP/ASPNET, LosBaños, Philippines.

Duddington C.L. 1956. The friendly fungi. Faber andFaber Ltd., London. 168 pp.

Generalao L. & R.G. Davide. 1986. Biological controlof Radopholus similis with three ne-matophagous fungi. Phil. Phytopath. 22: 36-41.

Jatala P. 1986. Biological Control of Plant ParasiticNematodes. Ann. Rev. Phytopathol. 459-489.

Persson C & H.B. Jansson. 1997. Colonization of soilby nematophagous fungi. Tercer Seminario Cien-tífico Internacional sobre Sanidad Vegetal. Ciu-dad Habana. Resúmenes. 127 pp.

Stirling G.R. 1988. Biological Control of Plant Para-sitic Nematodes. Pp. 93-139 in Diseases of nema-todes. Vol. II. CRC Press Inc., Boca Raton,Florida.

The authors work at the Instituto de Investigacionesen Viandas Tropicales, INIVIT, Santo Domingo, VillaClara, Cuba, CP 53000, e-mail: [email protected].

INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2 9

Table 1. Effect of the different treatments on the root weight of plantain tissueculture.

Treatement Control A B C D

Root weight (g.) 5.9a 6.2a 1.3b 7.3aThe values followed by the same letter are significantly different at P < 0.05.

Edna A. Aguilar, David W. Turner andK. Sivasithamparam

Localized wilting in Cavendishplants in the Philippines (Stover1990) and Carnarvon, Western

Australia (Pegg et al. 1995) have beenassociated with sub-optimal conditions

such as waterlogging and poordrainage. These anecdotal reportshave not been investigated experimen-tally.

Excess water can be a problem in ba-nana plantations, particularly after aheavy rainfall or irrigation of heavysoil. Banana fields may suffer floodingor long-term waterlogging that may

damage the root system and contributeto the susceptibility of bananas toFusarium wilt (FW).

Waterlogging reduces O2 and in-creases CO2 and ethylene concentra-tion in soil (Ponnamperuma 1984). Thediffusivity of O2 in water is 1/10 000th ofits value in air; thus, dissolved O2 in thesoil solution is depleted in a few hoursor days due to consumption by plantroots and soil microorganisms (Drew1990). O2 is essential for respiration,the process by which aerobic organismsproduce energy in the form of ATP.Here, we review recent studies on theshort-term response of banana rootsand the FW pathogen (Fusarium oxys-porum f.sp. cubense (E.F. Smith) Sny-der and Hansen) to O2 deficiency andsuggest a role for these responses in the

Proposed mechanisms on howCavendish bananas arepredisposed to Fusarium wiltduring hypoxia

Effect of waterloggingPhysiology

predisposition of putative resistant ba-nana cultivars to FW.

Possible role of aerenchymaLysigenous air spaces (aerenchyma)have been reported in earlier studies ofbanana roots and in a number of culti-vars (Acquarone 1930, Riopel & Steeves1964, Aguilar et al . 1999). Theaerenchyma provides a continuous pathfor O2 diffusion from shoots to roots, in-creasing the flux of O2 along the cortex.We quantified the root porosity of dif-ferent banana cultivars and measuredinherent differences in ease of O2 move-ment along roots. The mature roots ofCavendish cultivars (AAA) have 10% ofthe volume as aerenchyma whileGoldfinger (AAAB) has 5% (Aguilar et

al. 1999). Hypoxia further increasedporosity and the thickness of the roots(Figure 1). When the physical resis-tance to internal gas diffusion was com-pared, the differences between the fourcultivars studied disappeared (Aguilaret al. 1998), suggesting that these rootswere equally adapted to stagnant condi-tions and potentially conduct gaseousO2 three to five times more easily thanaerated roots. O2 concentration in theroot tissues is sensitive to changes inthe outside O2 concentration. Even withcortical aerenchyma, the stele, wherethe pathogen initiates the disease, haslow O2 concentrations (1.3-2.6 kPa)even if the medium outside of the rootis fully aerated (21 kPa) (Aguilar et al.1998) (Figure 2). Hypoxia (4 kPa O2)

outside the roots induces stelar anoxiain excised banana roots (Aguilar 1998).Reducing the O2 concentration at theroot surface to about 18 kPa is esti-mated to already create an anoxic corein the stele. This finding has implica-tions for the development of Fusariumwilt because it is in the stele where thehost and pathogen interaction is criti-cal in disease development. When thestele is anoxic, the mobilization of thehost defense mechanisms in infectedroots may be slowed or stopped alto-gether, since most of these processesrequire energy.

If the FW pathogen could better tol-erate lower O2 concentrations, it wouldhave the impetus to colonize and besystemically distributed along the rootswhile the root suffers. In in vitro stud-ies, mycelial growth remained unim-paired even at 1% O2 but no growth oc-curred under anoxia (0% O2).Regeneration of growth following re-turn of aeration was observed (Aguilar1998). Germinating Foc conidia had lowhyphal density and frequently ceasedactivity and produced chlamydosporesor resting hyphae when O2 becomeslimiting (Figure 3). Our studies furthershowed that the pathogen could exploitthe presence of aerenchyma and the as-sociated higher concentrations of O2 itcontains (Aguilar 1998) (Figure 4).

Thus, the aerenchyma, although pro-viding an advantage for the host to sur-vive hypoxic conditions, could be the“Achilles heel” of some banana culti-vars that could otherwise resist Fusar-ium wilt. Aerenchyma appears to offeran alternative and favourable path forthe pathogen to invade the root longitu-dinally, outside of the vascular system.It is possible to envisage a scenariowhere the pathogen, using theaerenchyma as a base, occasionallygrows into the stele, to access nutri-ents, then transfers them via cytoplas-mic streaming back to the mycelium inthe aerenchyma where it obtains itsrespiratory requirement. This situationenables the pathogen to continue itsgrowth in the stele that by itself wouldbe an adverse environment. It is likelythat when conditions in the stele are in-hospitable for the pathogen, Foc couldresort to a latent phase. The process in-volving the passage of the pathogenthrough the aerenchyma could con-tribute to rapid invasion of the corm(Aguilar 1998).

Role of reduced root elongationand root tip death under anoxiaAnoxia (0% O2) in the root mediumstopped root elongation within 30 min-utes. Re-aeration after 4 h of anoxia re-stored elongation rate to only 50% of

10 INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2

Figure 2. Oxygen profile of banana root (28 mm from the apex) measured by a microelectrode instreaming solution.

Figure 1. Aerenchyma development in roots of cv. Williams grown in stagnant or aerated nutrientmedium. Roots were about 200 mm long. The sections were taken 50 mm and 100 mm from the roottip. Scale is 0.1 mm.

Roots emerged in stagnantmedium (50mm from tip)

Roots emerged in aerated medium(50mm from tip)

Roots emerged in stagnantmedium (100mm from tip)

Roots emerged in aerated medium(100mm from tip)

Oxy

gen

e d

iffu

sio

n c

urr

ent

(pA

) Oxyg

en co

ncen

tration

(kPa)

boundary layer

non-porous cotex

porous cortex

stele

continuously aerated roots. Anoxia formore than 6 h killed the root tips(Aguilar 1998) (Figure 5). Reduced rootgrowth can favour infection by increas-ing the time of exposure of susceptibleparts of the root to the inoculum, whiledeath of root tips would give thepathogen an open infection route withdirect access to the stele. This suggeststhat even temporary flooding could fa-cilitate the entry and perhaps patho-genic activity of the pathogen into theroot without it being subject to the nor-mal host resistance mechanisms of un-affected tissue. Fusaria appear to havethe capacity to be a facultativenecrotroph capable of being an endo-phyte in susceptible and resistanthosts.

Several, short bursts of anoxia, eachof which was not severe enough to killthe root tips, enabled the roots to sur-vive and elongate further but at a re-duced rate (Aguilar et al. 1998). Thissuggests the ability of roots to acclima-tize to hypoxia. Hypoxic pretreatmentimproves tolerance to anoxia in maize(Gibbs et al. 1998).

Role of peroxidase (PER) andphenylalanine ammonia lyase(PAL) enzymesPER and PAL are key enzymes impli-cated in induced resistance. The pro-duction of peroxidase (PER) is corre-lated with increased lignification anddisease resistance in host-pathogen sys-tems such as cabbage and Fusariumoxysporum f.sp. conglutinans (Heite-fuss et al. 1960), potato and Phy-topthora infestans (Friend et al. 1973),diploid banana (Musa acuminataColla) and Foc (Morpugo et al. 1994).PAL activity is correlated with resis-tance in crops, such as cowpea, to thepathogen Phytophthora vignae (Ralton

et al. 1988) and soybean toP. megasperma f.sp. glycinea (Bhat-tacharya and Ward 1988).

We investigated the effects of Foc in-fection and hypoxia on the activities ofPER and PAL in the roots of cultivarsknown to be resistant or susceptible toFoc (Aguilar et al. 2000).

Hypoxia stimulated PAL and PER ac-tivity. It is not known whether the in-creased activities of these enzymes, re-sulting from hypoxic stress, could offersome protection to the host. Foc infec-tion increased PER activity. When thepathogen and hypoxia were combined,the differences in rapidity and degreeof increase in PAL and PER activitiesappear to be associated with resistanceto FW, particularly with the breakdownin resistance of Williams (a Cavendishcultivar). Goldfinger, known to be moreresistant to FW, responded with higherand more sustained PER and PAL activ-

ities compared with either cv. Williamsor cv. Gros Michel (Figures 6 and 7).This quantitative difference could be afactor that contributes to Williams suc-cumbing to FW under waterlogging(Aguilar et al. 2000). There are someexciting issues here that need furtherinvestigation. While hypoxic treatmentmight be a way to stimulate the root’sdefence mechanism, it has to be at alevel, duration and timing that wouldenhance PER and PAL activities with-out causing irreparable damage to rootfunctions. Genetic markers may befound among banana cultivars for theseenzymes which could be used in build-ing up quantitative resistance in ba-nanas to Fusarium wilt.

The site of synthesis and enzyme ac-tivity in the root is critical in determin-ing its importance for Fusarium wilt re-sistance. To be effective, increasedenzyme activity should be concentratedin, or around, the vascular systemwhere the active host defence mecha-nisms operate and in tissues adjacentto the root tip which could be sites ofinfection, particularly in the event ofroot tip death. Phenol metabolism is anoxidation process and hypoxia shouldhave rendered parts of the stele anoxicwhile the cortex will be relatively moreaerated. It is possible that PAL is syn-thesized in the more aerated parts ofthe root but whether it can be active inthe stele where it is much needed is yetto be established (Aguilar et al. 2000).

The PAL and PER enzyme activitiesdeclined upon re-aeration, whereas thepathogen (which forms resting sporesunder hypoxia) easily reverts to nor-mal mycelial growth upon re-aeration.Thus, Foc’s renewed activity withinhours of re-aeration should bematched with sustained enzyme activ-

INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2 11

Figure 4. Hyphal growth of Fusarium wilt pathogen in cortical aerenchyma of banana roots.

hyp

hal

den

sity

(m

m/m

m2 )

Diffuse path length (mm)

40

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

00 2 4 6 8 10 12

Figure 3. Effect of increasing diffusive path length (mm) of O2 on hyphal density (mm/mm2) ofFusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense (Foc) 24 h after inoculation.

ity in a host resistant interaction. Thebest option for the host to incur resis-tance would be to sufficiently increaseenzyme activities during hypoxia tocontain the then inactive pathogen be-fore re-aeration. Post-anoxic injurywhen the stress becomes too severe,could deprive the host of its ability forcontinued resistance (Aguilar et al.2000).

ConclusionIt is the physiological state of the hostupon re-aeration that will determinethe outcome of host-pathogen interac-tion under oxygen deficiency. Irrepara-ble damage to root function wouldsurely favour the pathogen, and hence,disease development follows or may

even be enhanced. If the root acclima-tizes and elicits timely and sufficientdefence reactions during hypoxia, thenit could gain advantage over thepathogen. When the next stress occurs,its duration and severity will most likelydetermine the ensuing host-pathogendynamics (Aguilar 1998). ■

ReferencesAcquarone P. 1930. The roots of Musa sapientum L.

Rep. No. 26. United Fruit Co., Research Dept.Boston, Mass.

Aguilar E.A. 1998. Responses of banana roots to oxy-gen deficiency and implications for Fusariumwilt infection. PhD Thesis, The University of Wes-tern Australia. 148 pp.

Aguilar E.A., D.W. Turner, D.J. Gibbs, W. Armstrong& K. Sivasithamparam. 1998. Response of banana

(Musa sp.) roots to oxygen deficiency and its im-plications for Fusarium Wilt. Acta Horticulturae490: 223-228.

Aguilar E.A., D.W. Turner & K. Sivasithamparam.1999. Aerenchyma formation in roots of four ba-nana (Musa spp.) cultivars. Scientia Horticultu-rae 80: 52-72.

Aguilar E.A., D.W. Turner & K. Sivasithamparam.2000. Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense inocu-lation and hypoxia alter peroxidase and phenyla-lanine ammonia lyase enzyme activities in nodalroots of banana cultivars (Musa sp.) differing intheir susceptibility to Fusarium wilt. AustralianJournal of Botany 48: 589-596.

Bhattacharya M.K. & E.W.B. Ward. 1988. Phenylala-nine ammonia-lyase activity in soybean hypoco-tyls and leaves following infection with Phytoph-thora megasperma f. sp. glycinea. CanadianJournal of Botany 66: 18-23.

Drew M.C. 1990. Sensing soil oxygen. Plant, Cell andEnvironment 13: 681-693.

Friend J., S.B. Reynolds & M.A. Aveyard. 1973. Phe-nylalanine ammonia-lyase, chlorogenic acid andlignin in potato tuber tissue inoculated with Phy-tophthora infestans. Physiological Plant Patho-logy 3: 495-507.

Gibbs J., D. W. Turner, W. Armstrong, M.J. Darwent& H. Greenway. 1998. Response to oxygen defi-ciency in primary roots of maize. 1. Developmentof oxygen deficiency in the stele reduces radialsolute transport to the xylem. Australian Journalof Plant Physiology 25: 745-758.

Heitefuss R., M.A. Stahmann & J.C. Walker. 1960.Oxidative enzymes in cabbage infected by Fusa-rium oxysporum f. conglutinans. Phytopatho-logy 50: 370-375.

Morpugo R.S., V. Lopato & F.J. Novak. 1994. Selec-tion parameters for resistance to Fusarium oxy-sporum f.sp. cubense race 1 and race 4 on di-

12 INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2

Figure 6. Effect of inoculation by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp.cubense (Foc) and/or hypoxia on phenylalanine ammonia-lyase(PAL) enzyme activity in roots of banana cvs a) Williams, b)Goldfinger, c) Gros Michel and d) Sugar. Treatments were: noFoc, continuously aerated (NFA); Foc-inoculated, continuouslyaerated (FA); Foc-inoculated, continuously hypoxic (FHH); noFoc, continuously hypoxic (NFHH); no Foc, hypoxic for 48 h, thenre-aerated (NFHA); and Foc-inoculated, hypoxic for 48 hours,then re-aerated (FHA). Vertical bars along line plots arestandard errors where they are larger than the symbols. Verticallines outside of plots are measures of significant meandifferences at p = 0.05 using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test(DMRT). Top to first division is for comparison of adjacentpoints, while from top to the bottom division is for comparisonof highest to lowest points.

a)Williams

25

20

15

10

5

00 24 48 72 96 120 144

0 24 48 72 96 120 144

c) Gros Michel25

20

15

10

5

0

b)Goldfinger25

20

15

10

5

00 24 48 72 96 120 144

Time (hours)

Time (hours)

Time (hours)

Time (hours)

d) Sugar25

20

15

10

5

00 24 48 72 96 120 144

NFA FA FHHNFHH NFHA FHA

PA

L ac

tivity

( m

ol C

A/h

/g F

oc)

PA

L ac

tivity

( m

ol C

A/h

/g F

oc)

PA

L ac

tivity

( m

ol C

A/h

/g F

oc)

PA

L ac

tivity

( m

ol C

A/h

/g F

oc)

Figure 7. Effect of inoculation by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. cubense (Foc)and hypoxia on peroxidase (PER) enzyme activity in roots of banana cvs a)Williams, b) Goldfinger, c) Gros Michel and d) Sugar. Treatments were: noFoc, continuously aerated (NFA); Foc-inoculated, continuously aerated (FA);Foc-inoculated, continuously hypoxic (FHH); no Foc, continuously hypoxic(NFHH); no Foc, hypoxic for 48 hours, then re-aerated (NFHA); and Foc-inoculated, hypoxic for 48 hours, then re-aerated (FHA). Vertical bars alongline plots are standard errors where they are larger than the symbols.Vertical lines outside of plots are measures of significant mean differencesat p = 0.05 using Duncan’s Multiple Range Test (DMRT). From top to firstdivision is for comparison of adjacent points, while from the top to thebottom division is for comparison of highest to lowest points. Horizontalline HH indicates the duration of the continuous hypoxic treatment (120 htotal) and HA indicates the duration of the short-term hypoxia (48 h) andwhen re-aeration commenced (72 h).

0 24 48 72 96 120 144

a) Williams10

8

6

4

2

0PE

R a

ctiv

ity (

AO

D/s

/g F

oc)

PE

R a

ctiv

ity (

AO

D/s

/g F

oc)

PE

R a

ctiv

ity (

AO

D/s

/g F

oc)

PE

R a

ctiv

ity (

AO

D/s

/g F

oc)

Time (hours)

HH

HA

0 24 48 72 96 120 144

b) Goldfinger10

8

6

4

2

0

Time (hours)

0 24 48 72 96 120 144

c) Gros Michel10

8

6

4

2

0

Time (hours) Time (hours)

d) Sugar10

8

6

4

2

00 24 48 72 96 120 144

NFA FA FHH NFHH NFHA FHA

Figure 5. Root elongation of banana cv. Williams in aerated nutrient solution (control) and afterimposition of 2,4 and 6.5 hours of anoxia.

0

50

40

30

20

10

050

40

30

20

10

0

50

40

30

20

10

050

40

30

20

10

15 30 45 60 0 15 30 45 60

0 15 30 45 60 0 15 30 45 60

Time (hours)

Elo

ng

atio

n (

mm

)

aerated control aerated control

recoveryrecoveryan

oxi

a

ano

xia

ano

xia

aerated

aerated

aéré

2h

4h 6.5h

1.02 = 0.08

0.45 = 0.04

0.88 = 0.15 0.02 = 0.02

0.47 = 0.060.83 = 0.14 0.42 = 0.01

ploid banana (Musa acuminata Colla). Euphy-tica 75: 121-129.

Pegg K.G., R.G. Shivas, N.Y. Moore & S. Bentley.1995. Characterisation of a unique population ofFusarium oxysporum f.sp. cubense causing Fu-sarium wilt in Cavendish bananas at Carnarvon,Western Australia. Australian Journal of Agricul-tural Research 46: 167-178.

Ponnamperuma F.N. 1984. Effects of flooding onsoils. Pp. 10-46 in Flooding and Plant Growth(T.T. Kozlowski, ed.). Academic Press, Inc., Flo-rida.

Ralton J.E., B.J. Howlett, A.E. Clarke, J.A.G. Irwin &B. Imrie. 1988. Interaction of cowpea with Phy-tophthora vignae: inheritance of resistance andproduction of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase as aresistance response. Physiological and MolecularPlant Pathology 32: 89-103.

Riopel J.L. & T.A. Steeves. 1964. Studies on theroots of Musa acuminata cv. Gros Michel: theanatomy and development of main roots. Annalsof Botany 28: 475-494.

Stover R.H. 1990. Fusarium wilt of banana: somehistory and current status of the disease. Pp. 1-18in First International Conference on FusarialWilt of Banana (R.C. Ploetz, ed.). American Phy-topathological Society Press, St. Paul, Minn.

Edna A. Aguilar works at the Farming Systems andSoil Resources Institute, College of Agriculture, Uni-versity of the Philippines at Los Baños, College, La-guna 4031, Philippines, David W. Turner works inPlant Sciences, and K. Sivasithamparam in SoilScience and Plant Nutrition at the Faculty of Agricul-ture, The University of Western Australia, Nedlands,WA 6907, Australia.

INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2 13

Josué Francisco da Silva Junior, ZiltonJosé Maciel Cordeiro and Arlene

Maria Gomes Oliveira

Panama disease or Fusarium wilt ofbanana caused by the fungusFusarium oxysporum f. sp.

cubense (Foc) is one of the most seri-ous problems in banana production asit causes serious damage in outbreakzones. The decisive role played by thegenotype of banana cultivars in the ex-pression of their resistance or suscepti-bility to the disease is well known. How-ever, it is also considered that theintensity of Panama disease is more orless directly related to edaphic factorsand plant nutrition and that these fea-tures may affect resistance mechanismssuch as gel (gum) formation and tylosis(Stover 1962, Borges Perez et al. 1983,Beckman 1990).

In the Canary Islands, Alvarez et al.(1981), Gutierrez Jerez et al. (1983),Borges Perez et al. (1983) and TrujilloJacinto del Castillo et al. (1983) per-formed soil observations in healthy andinfected zones and concluded that thepH, the organic matter content (OM),levels of calcium (Ca), magnesium(Mg) and zinc (Zn) and Ca:Mg andK:Mg ratios were closely correlatedwith the appearance of the disease. InTaiwan, Tu and Cheng (1982), Hwang(1985), Sun and Huang (1985) and Suet al. (1986) obtained promising resultswhen they undertook tests with a viewto controlling Panama disease bymeans of suppressive and conducivesoils and the addition of various organicor inorganic compounds to soils wherethere had been severe attacks of thedisease. Observations in Bahia State inBrazil showed that the organic mattercontent was higher in healthy soil zones(EMBRAPA 1987).

In Brazil again, Malburg et al. (1984)reported that low pH values and Ca, Mgand Zn levels in soils in Santa CatarinaState planted with ‘Enxerto’ (‘PrataAnã’ AAB) and ‘Branca’ (AAB) bananaswere related to a high wilt level. Obser-vations in Bahia and Espirito Santoshowed that in infected zones the pHand Ca, Mg and Zn levels were lowwhereas K:Ca and K:Mg ratios werehigh (EMBRAPA 1987, EMCAPA 1988).

In Tenerife, Borges Perez et al. (1991)observed that Zn fertilization for threeyears significantly reduced the inci-dence in the field of Panama disease in‘Dwarf Cavendish’ banana.

In the light of these resultsis, thework presented here was aimed at eval-uating the effect of chemical character-istics of soils such as the organic mattercontent, pH, level and Ca, Mg and Znlevels on the incidence and intensity ofPanama disease in ‘Prata Anã’ banana(AAB).

Material and methodsThe trial was performed on land belong-ing to the Centro Nacional de Pesquisade Mandioca e Fruticultura Tropical(CNPMF), Empresa Brasileira dePesquisa Agropecuária (EMBRAPA), atCruz das Almas, Bahia State, Brazil.Holes with a volume of 0.38 m3 (0.70 min diameter and 0.30 m deep) linedwith polyethylene were filled with ei-ther yellow latosol with cohesion Tb,and medium to clayey texture or withorganic soil collected at a depth of 0 to30 cm. The original chemical character-istics of the soils used are shown inTable 1. Corms weighing about 2 kg ofthe cultivar ‘Prata Anã’ (AAB), consid-ered to be susceptible to Panama dis-ease (Cordeiro et al. 1991), wereplanted.

A fully random statistical protocolwas used with 10 treatments and 10repetitions, with each plant represent-ing an experimental plot. The followingtreatments were applied to evaluate theeffect of Ca alone or in combinationwith Mg, pH, OM or soil sterilizationand the addition of Zn: 0) Organic soil + liming1) Sterilized organic soil + liming2) Sterilized inorganic soil + liming3) Inorganic soil with no liming4) Inorganic soil + ZnSO4 + liming5) Inorganic soil + liming6) Inorganic soil + liming with CaCO3

(pH approximately 7.5)7)Inorganic soil + liming with

CaCO3.MgCO3 (pH approximately 7.5)8) Inorganic soil + liming with MgO

(pH approximately 7.5)9) Inorganic soil + CaSO4.2H2OInorganic and organic soils were steril-ized by fumigation with methylene bro-mide at 340.55 cm3 per m3 soil.

Soil chemical parameters inrelation to the incidence andintensity of Panama disease

Diseases Influence of soil composition

Dolimitic limestone (total relativeneutralization capacity 99%) was usedin treatments 1, 2, 3, 5 and 6 to achieveCa+Mg contents of 40 mmolc/dm3 inconformity with the indications pro-vided by the soil analysis (Comissão Es-tadual de Fertilidade do Solo 1989).This means that 3.13 t/ha lime wasadded in treatments 1 and 2 and 2.93t/ha to treatments 3, 5 and 6. Treatment4 was the control since it does not in-clude any liming.

In treatments 7, 8 and 9, the Ca andMg sources (calcitic lime, dolomiticlime and magnesium oxide respec-tively) raised the soil pH to approxi-mately 7.5. In conformity with the incu-bation method recommendations, 9.48t/ha calcitic lime was added in treat-ment 7, while 7.46 t/ha dolomitic limewas added in treatment 8, and 3.23 t/hamagnesium oxide in treatment 9.

In treatment 10, application of 13.70t/ha agricultural plaster correspondedto 277.12 g Ca per hole, i.e. the sameamount Ca as applied in treatment 7 inthe form of CaCO3.

Zinc sulphate at 19.05 g/hole, theequivalent of 4.0 g Zn/plant was addedtwo months after sowing in treatment 5at the same time as the first nitrogenfertilization.

The plants were fertilized with NPKat 100 kg N/ha, 40 kg P2O5/ha and 450kg K2O/ha, provided by ammonium sul-phate, single superphosphate andpotassium chloride respectively.

Soils were analyzed using themethodology of the Serviço Nacionalde Levantamento e Conservação deSolos - SNLCS (EMBRAPA 1979). Sam-ples were taken during the followingphases of the experiment: before theholes were dug, at planting (twomonths after chemical correction) andafter 11 months of plant growth.

The plantlets were inoculated fourmonths after planting with 6.0 ml sus-

pension of Foc spores, corresponding to8.3 x 107 conidia/hole or 700 conidia/gsoil. The inoculum was placed in 100gmaize flour-sand mixture. Inoculationwas performed by digging furrows 10cm deep around each plant, spreadingthe inoculum and then refilling imme-diately (EMBRAPA 1991).

The final evaluation of infection wasperformed seven months after inocula-tion by pulling out 11-month-old plantsto observe the degree of rhizome infec-tion in a series of cross sections run-ning from the base to the apex andrecording scores of 0 to 6 on the scaleproposed by Cordeiro et al. (1993):0. Rhizome totally undamaged1. Isolated points of infection2. Infection covering more than 1/3 of

the stele cross section3. Infection covering 1/3 to 2/3 of the

stele cross section4. More than 2/3 of the stele cross sec-

tion infected5. Overall infection6. A plant displaying external symptoms

and/or symptoms visible on the pseu-dostem.

Analysis was performed from the dataobtained by applying Tukey’s test (P <0.05) to compare the averages of thedifferent treatments. Pearce’s correla-tion coefficients were also calculated.

Results and discussion

The effect of organic matterThe high OM content of the organic soilin comparison with that of the inor-ganic soil affects the levels of intensity

of the disease. Indeed, treatments 1and 2 display lower indices of infectionthan those of the other treatments (Fig-ure 1). The strong correlation (r = 0.61)between the average score for Foc in-fection and the organic matter content(Table 2) confirms the positive effect ofOM on the control of Foc, with a 1% de-gree of significance. In addition, withno sterilization (treatment 1), the useof organic soil results in significant dif-ferences compared to the control(treatment 4) in Tukey’s test (5%).

These results show that the damageto plants caused by the pathogen is in-significant, implying that this soil maypossess a suppressive character that re-mains as long as the conditions deter-mining it are maintained. According toHornby (1983), the majority of themechanisms proposed for explainingthe suppression of the disease on thistype of soil have not been proved. It isassumed that abiotic factors such as cli-mate, soil chemical characteristics(acidity, type of clay) and physical char-acteristics (moisture) act in synergywith the biotic factors.

Among biotic factors, it is supposedthat the phenomenon of antagonism be-tween the original soil microbiosphereand the pathogen causes the reductionof infection. The phenomenon is verycommon in soils that are very rich inOM and is important for the microbio-logical equilibrium of the soil and thebiological control of pathogenic organ-isms (Clark 1965, Siqueira and Franco1988). The high percentage of OM isgenerally related to a high microbialpopulation (Warcup 1965) and in-creases the soil fungistasis effect, mak-ing it difficult for a newly introducedmicroorganism to become established.This results in reduction or control ofthe disease.

There are no significant differencesbetween infection levels with regard tothe sterilization or not of organic soils(treatments 1 and 2) and mineral soils(treatments 3 and 6) (Figure 1). Ac-cording to Hemwall (1960), soils with ahigh OM content are relatively difficultto fumigate. Later, Kreutzer (1965)pointed out that OM can also protectsoil microorganisms from the effect offumigants.

In addition, it is known that whensoils are sterilized, as in this experi-ment, the original microbiosphere recov-

14 INFOMUSA — Vol 9, N° 2

Table 1. Initial chemical characteristics of the yellow latosol and the organic soil(from a depth of 0-30 cm) used in the trial at Cruz das Almas, BA, Brazil.

Characteristics Yellow latosol Organic soil

pH - H2O 4.80 4.70

P (mg/dm3) 0.90 27.50

K (mmolc/dm3) 0.50 0.90

Ca (mmolc/dm3) 6.50 6.50

Mg (mmolc/dm3) 4.50 2.50

Al (mmolc/dm3) 1.00 1.20

Na (mmolc/dm3) 0.50 0.90

H + Al (mmolc/dm3) 54.00 188.00

CTC (mmolc/dm3) 66.00 198.00

Organic matter (g/dm3) 21.00 173.00

Mn (mg/dm3) 3.94 1.10

Fe (mg/dm3) 89.05 27.49

Zn (mg/dm3) 3.50 3.17

Cu (mg/dm3) 0.31 0.71

Table 2. Coefficients of correlation between organic matter, pH and Foc infectionscores.

Variables pH Organic matter

Organic matter -0.22*

Infection score 0.43** -0.61*** Significant at 0.05 probability.

** Significant at 0.01 probability.

ers rapidly because methyl bromide doesnot have any residual effects (Kreutzer1965, Vanachter 1979). Some microor-ganisms that possess survival structuresand resist fumigation—in particular cer-tain fungi—may be capable of initiatingrepopulation (Kreutzer 1965).

The effect of pH, calcium and magnesiumThe application of large quantities ofCa alone, using agricultural plaster,without changing the initial pH of inor-ganic soil (treatment 10), did not havea positive effect on the control of thedisease (Figure 1). This is in conformitywith the experiments performed byKnudson from 1923 to 1927 (Stover1962), in which the Ca compounds useddid not modify the soil pH.

It is observed that the high soil pH re-sults in an infection rate that is alsohigh. The liming performed to raise thepH to approximately 7.5 in treatments7, 8 and 9 using large quantities of Ca,Ca+Mg and Mg respectively did nothave a positive effect with regard tocontrol of Panama disease, since the in-fection levels observed were higherthan that of the control (Figure 1).

Similar results were obtained in someproduction regions in the world (Stover1962, Blesa Rodríguez and FernandezCaldas 1973, García 1977) where soilswith high pH and high Ca and Mg con-

tents were affected by the disease.There have even been cases, as in Tai-wan (Hwang 1985), in which the high-est infection indexes were recorded in

zones where liming was performed(zones with a pH higher than 7.0). How-ever, the positive effect on Panama dis-ease of a high pH combined with Ca andMg has been widely described in the lit-erature, with the observations and testsperformed by Knudson (1923-1927),Volk (1930 a, b), Volk and Gallatin(1930), Wardlaw (1935), quoted byStover (1962), Scarseth (1945), Rish-beth (1957), Stover and Malo (1972),Alvarez et al. (1981), Malburg et al.(1984) and EMCAPA (1988).

In treatments 7, 8 and 9, the largedoses of Ca and Mg applied singly or to-gether, combined with a high pH proba-bly caused an imbalance in the inor-ganic soil, influencing not only itschemical characteristics but also itsoriginal microbiosphere, in which mi-croorganisms that are important com-petition for the pathogen were thuseliminated. This imbalance, combinedwith the susceptibility of the cultivarused, may have contributed to higherlevels of infection in the plants.

In treatment 4 (Figure 1), the bal-ance of soil characteristics was almostunchanged and this may be one of thereasons for the minor incidence of thedisease. In addition to this, the poorsoil fertility conditions in this treat-ment may have caused less root growthresulting in a smaller infection indexbecause the pathogen penetrates theplants via the secondary and tertiaryroots (Stover 1962). The more devel-oped the root system, the greater thechances of new infections.

The effect of zincThere were no significant differences ininfection levels when zinc was added toinorganic soil (treatment 5) and com-pared with treatments 4 (control) and 6(treatment without Zn but with liming)(Figure 1). Because of its susceptiblebehaviour, the cultivar ‘Prata Anã’ isprobably not effective in time and spacein the development of effective resis-tance mechanisms (Beckman et al.1962, Borges Perez et al. 1983, Beck-man 1990). Or perhaps it might havebeen necessary to add larger quantitiesof this nutrient, as is done on ‘DwarfCavendish’ in the Canary Islands(Borges Perez et al. 1991). A third hy-pothesis could be that Zn has little orno effect on the control of Panama dis-ease in contrast with suppositions.

Conclusions• Organic soil was found to be a sup-

pressive substrate for the develop-ment of Panama disease in ‘PrataAnã’ banana.

• Liming performed to raise the soil pHto approximately 7.5 using Ca and Mg

and the addition of large quantities ofCa alone without modifying the soilpH have no positive effect on the con-trol of Panama disease.

AcknowledgementsThe authors thank Ana Lucia Borgesand Aristóteles Pires de Matos, re-searchers at Embrapa Mandioca eFruticultura, for their suggestions. ■

ReferencesAlexander M. 1961. Introduction to soil microbiol-

ogy. John Wiley & Sons, New York. 472 pp.Alvarez C.E., V. García, J. Robles & A. Díaz. 1981.

Influence des caractéristiques du sol sur l’inci-dence de la maladie de Panama. Fruits 36(2): 71-81.

Beckman C.H. 1990. Host responses to thepathogen. Pp. 93-105 in Fusarium wilt of banana(R.C. Ploetz, ed.). The American Phytopathologi-cal Society, Saint Paul, Minnesota.