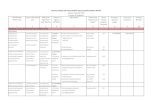

Mandate for Gender Mainstreaming and Related Institutional Arrangement National and International.

The IMF and Gender A Critical Analysis · 2016-06-23 · The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical...

Transcript of The IMF and Gender A Critical Analysis · 2016-06-23 · The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical...

The IMF and GenderA Critical Analysis

P u b lis h e r : B r e t t o n W o o d s P r o je c t

June 2016

A n y e r r o r s a n d o m is s io n s a r e s o le ly t h e r e s p o n s ib ilit y o f t h e a u t h o r s .

C o p y r ig h t n o t ic e : T h is t e x t m a y b e f r e e ly u s e d p r o v id in g t h e s o u r c e is c r e d it e d .

Glossary

EM Emerging MarketFLFP Female Labour Force ParticipationGII Gender Inequality IndexILO International Labour OrganisationLIC Low Income CountryMDGs Millennium Development GoalsOECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and DevelopmentSDGs Sustainable Development GoalsSDN Staff Discussion NoteSRHR Sexual and Reproductive Health and RightsTA Technical AssistanceUNFPA United Nations Population FundUNICEF United Nations Children’s Emergency FundVAT Value Added TaxesWHO World Health Organization

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

Cover photo: The Brick Factory Pt. 2, Myanmar, 2015

© Ar

iel L

euen

berg

er

1. Introduction 4

2. IMF Mandate and Functions 53. The IMF’s recent work on gender equality 64. Reconsidering Macro-criticality 75. Conventional Policy Impacts 8

6. Conclusion 12

Endnotes 13

C o n t e n t s

Acknowledgements:

This briefing was written by Emma Bürgisser and Sargon Nissan of the Bretton Woods Project.

It is part of the Gender Equality and Macroeconomics (GEM) Project, a collaborative effort between theBretton Woods Project and the Gender & Development Network (GADN), which aims to expose andchallenge the way current macroeconomic policies, and particularly those promoted by the InternationalMonetary Fund and World Bank, undermine gender equality. Working with allies globally, the GEM Projectencourages decision-makers to promote better and alternative policies.

Invaluable input was generously provided by Jessica Woodroffe and Megan Daigle (GADN), Chiara Capraro(Christian Aid), Kate Bedford (University of Kent) and Rachel Moussié (public policy and gender consultant),as well as Luiz Vieira, Petra Kjell and Roosje Saalbrink (Bretton Woods Project).

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

In September 2015, the United Nations General Assembly adoptedthe Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), replacing the expiredMillennium Development Goals (MDGs) and setting out 17 universallyaccepted, globally applicable goals to realise sustainabledevelopment. Reacting to the adoption of the SDGs, the IMFpresented itself as “uniquely positioned to support countries as theypursue the SDGs” and “committed, within the scope of its mandate,to the global partnership for sustainable development”.¹ Inparticular, it has “undertaken to deepen policy advice on aspects ofinclusion [including inequality and gender] and environmentalsustainability – core SDGs that are macro-relevant in many countries– and bring it to its operational work”.² It has also committed toconduct related policy-oriented research, including on “deepeningeconomic, gender and financial inclusion”.³

Prior to making these commitments, the IMF had not systematicallyaddressed the gendered impacts of its work, nor considered genderanalysis as an integral component of its macro‐economic analysis.⁴ Theadoption of this new work by the Fund therefore reflects abroadening of the orthodox interpretation of its macro-economicmandate as outlined in its Articles of Agreement. This appearsparticularly true for initiatives supporting SDG 5, the achievement ofgender equality and empowerment of all women and girls, an issue atthe heart of deeply entrenched political and societal powerstructures.

Such a broadening of interpretation and commitment to supportcountries in achieving gender equality by the IMF is welcome. It notonly enables the Fund to better carry out its mandate by providingmore comprehensive macro-economic analysis, but it is also key toachieving SDG 5 and realising the rights of all women and girls byrecognising the significant influence the Fund has on macro-economic policy and the lives of women and girls around the world.To strengthen this approach, this paper argues such an adjustmentalso merits critical analysis. While recognising that the Fund’s workdone so far in support of gender equality is still in its infancy, thispaper aims to contribute to shaping this potentially ground breakingwork by providing a critical perspective in three specific ways.

First, this paper asks how far the IMF has already fulfilled itscommitment to deepen its policy advice on gender and bring thisinto its operational work, in particular in a sustainable way. Secondly,the discussion will turn to some of the implications of adopting thisbroader approach to macro-criticality for the work on gender. Andfinally, the paper examines what role conventional IMF policy adviceplays in supporting the realisation of SDG 5. These questions will beasked in the context of the three core areas of IMF policy advice.Having tested IMF research and policy advice in the context of itsmandate and core functions against a survey of literature andresearch, the findings indicate that the macro-economic policyimplications of gender equality and the realisation of SDG 5 willnecessitate much deeper engagement by the Fund.

1. Introduction

©Tr

ocai

re

4

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

Mandate

The mandate of the IMF is stated in its Articles of Agreement, settingout the limits for the scope of its work. With such a mandate, theFund has been given the unique and specialised role of promotinginternational monetary cooperation. This includes facilitating theexpansion and balanced growth of international trade, therebycontributing to the promotion and maintenance of high levels ofemployment and real income as well as the maintenance of globalmacro‐financial stability.⁵ The latter role has expanded significantly inthe wake of the 2008 financial crisis. The Fund’s mandate restricts itsfield of work to matters that are either ‘macro-critical’ – those thathave influence over national, regional or international aggregateindicators such as GDP and unemployment rates – or that may beinfluenced by using macro-economic tools, such as the adjustmentof trade or fiscal policy. It is within the confines of this macro-economic mandate that this paper will examine the Fund and itsrelation to gender equality.

The IMF exercises its mandate through its three operationalfunctions, or core business areas: surveillance, technical assistanceand lending. Lending provides the institution with its greatest directinfluence over countries’ macro-economic policy making becauseloans are provided only if agreements are made on policy reforms.These are the known as conditionalities.

Surveillance

Established in Article IV of the Fund’s Articles of Agreement, IMFsurveillance monitors risks to national and global economic stability.The Fund reviews country policies annually and regularly monitorsnational, regional and global economic and financial developmentsvia periodic reports.⁶ Fund surveillance of its member states isconducted through annual country visits and regular discussionsbetween IMF staff and country officials. This interaction provides thebasis for a country’s annual surveillance study, known as its Article IVreport, which is submitted to the IMF executive board. The board’sviews on the report are subsequently shared with the country underreview, constituting the Article IV consultation, and are thenpublished by the IMF, subject to the permission of the country underreview.

The IMF’s surveillance function has a significant impact on countries’macro-economic policies. Surveys indicate a large share of low-income countries (LICs) and emerging markets (EMs) see the Fundas their key external advisor on macro-economic policy decisions,with “no other institution coming close to that position.”⁷ A 2014Surveillance Review report indicated EMs and LICs are likely to turnto the Fund for ad hoc advice outside regular consultations, withnearly “90 per cent of LIC and 60 per cent of EM respondents”indicating that they had approached the Fund in this way.⁸

Technical Assistance

The second function of the IMF is the provision of technicalassistance (TA). TA is designed to strengthen the human andinstitutional capacity of countries in developing their macro-economic policies. Comprising 27 per cent of the Fund’s spendingand often accompanied by training, TA is limited to the “core areasof expertise” of the Fund, which are “macro-economic policy, taxpolicy and revenue administration, expenditure management,monetary policy, the exchange rate system, financial sector stability,legislative frameworks, and macroeconomic and financialstatistics”.⁹

About half of all IMF TA was received by low-income and developingcountries in 2015, while 40 per cent targeted emerging and middle-income countries. A 2012 IMF TA evaluation survey found that 92 percent of responding agencies indicated that their staff “values IMFtraining more than training by other providers on similar topics”.¹⁰

Lending

The Fund lends to its members when they experience actual orpotential balance of payments problems – in short, a financial crisisor risk of one. To provide emergency finance, the Fund’s lendingfacilities are designed to be loans of last resort, aiming to “ease theadjustment policies and reforms that a country must make tocorrect its balance of payments problem and restore conditions forstrong economic growth”.¹¹ The IMF is thus the institution thatprovides an emergency loan when a country can no longer access itfrom any other source, such as financial markets. IMF loans comewith required economic policy conditions, known as conditionalities,which the member state agrees to undertake in order to receive thefinancing.

In 2015 the IMF provided $2.7 billion in concessional lending,meaning charging zero interest, to 17 low-income countries, plus $112billion in non-concessional lending to nine countries.¹² During thatyear, 58 low-income countries held outstanding debts to the Fund.¹³The volume of loans provided by the Fund, and therefore itsinfluence, grows during times of financial crisis, as each of the fivemajor international debt crises since the 1970s have demonstrated.¹⁴In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the Fund has increasedits lending firepower from $250 billion to nearly $1 trillion.¹⁵ The IMFis the leading international institution shaping macro-economicpolicy, most directly through its lending conditionalities; however, itis also a gatekeeper, effectively deciding which macro-economicpolicies are permissible, even in advanced economies.¹⁶

2. IMF Mandate and Functions

5

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

Since 2013, the IMF has explored the relevance of gender equality tomacro-economic growth and stability. This work has so far comprisedresearch and operationalising some of the research findings into theFund’s surveillance function. Research produced by the IMF isexplicitly not intended to represent the institutional view of the IMFand does not necessarily inform its policy.¹⁷ However, the research ongender conducted by the IMF, explored in more detail below, hasinformed a formal guidance note, a type of document used totranslate new evidence and policy approaches into practice. TheGuidance Note for Surveillance under Article IV Consultation waspublished in March 2015 and classified gender as one the “structuralissues that staff may wish to consider”, without further instruction.¹⁸Reflecting that guidance, some of the research findings wereoperationalised and adopted into pilot surveillance activitiesthroughout 2015. The IMF has also committed to increase coverageand in depth analysis throughout 2016 on inequality, climate changeand energy policies in addition to “gender issues”.¹⁹

Research findings

The IMF began to systematically undertake research consideringgender equality in 2013 with the publication of the Staff DiscussionNote (SDN) Women, Work and the Economy: Macroeconomic Gainsfrom Gender Equity, which examined the macro-critical features offemale labour force participation (FLFP). Based on the idea thatgender gaps in the labour market impose economic inefficiencies, itsmain finding was that there is ample evidence that when women areable to develop their full labour market potential, “there can besignificant macro-economic gains”, but that major global gaps in FLFPremain.²⁰ It considered evidence of structural constraints facingwomen to achieve equal labour force participation such as gendergaps in education and health, as well as high fertility rates. Theresearch made recommendations, most of which focused on macro-economic policy including tax and public expenditure reform.Amongst the recommendations were replacing family with individualincome taxation; publicly financed parental leave schemes; publicelderly care; comprehensive, affordable and high quality child care;pension reform and investment in pro-women education andinfrastructure. Finally, the SDN recommended policies on social andlegal anti-discrimination enforcement, increased awareness of legalrights and provision of alternative resolution mechanisms.

A 2015 SDN, informed by the World Bank’s Women, Business and theLaw publications, highlighted how legal barriers can constrain femalelabour force participation with often major macro-critical impacts. Itargued that legal restrictions can create economic inefficiencies asthey “restrict access to productive resources and economic choiceand prevent the efficient allocation of (labour) resources”.²¹ Asubsequent 2015 SDN entitled Catalyst for Change: EmpoweringWomen and Tackling Income Inequality focused on the linkagesbetween gender and income inequality, which reinforced

the previous findings that both gender and income inequalitysignificantly impede economic growth, finding moreover that“moving from 0 (perfect gender equality) to 1 (perfect genderinequality) on the gender equality index, or GII, can cause anincrease of 10 Gini points”.²² This suggests that gender inequalityshould be considered a major source of income inequality.²³ Itargued for a focus on complementing redistributive policies with i)correction of gender-based legal restrictions, ii) tax policy reform, iii)fiscal space for priority expenditures such as infrastructure, healthand education, iv) well-designed family benefits, v) genderresponsive budgeting, and vi) making financing more available towomen.

Surveillance

The SDNs’ findings have so far only impacted upon one of the threecore functions of the Fund: surveillance. The inclusion of data,analysis and, to a limited degree, recommendations featuring femalelabour force participation was piloted in at least nine Article IVreviews in 2015, including Chile, Costa Rica, Germany, Hungary, India,Japan, Korea, Mauritania and Sweden. Gender equality has not asyet been included in any IMF lending or TA programme.

The breadth of this pilot surveillance work varies widely per review.The 2015 Article IV review of India is limited to one sentencewelcoming the improvement of labour market flexibility as a way ofboosting falling female labour force participation rates.²⁴ The ArticleIV review of Sweden demonstrated that even in countries withrelatively small gender gaps there is “room for improvement[because] gender equity in participation rates and hours workedcould lift Sweden’s potential output by 6 per cent.”²⁵ The mostcomprehensive analysis is found in the 2015 Article IV review of Chile,which includes a separate annexe on women in Chile’s labourmarket. The review pointed out that narrowing the gender gap inChile could lead to important macro-economic gains, citing GDPlosses due to economic gender gaps equivalent to 17 per cent ofGDP.²⁶ The study recommended broad reforms to correct Chile’slabour force gender gap, including i) extending early-childhoodeducation and childcare services, ii) improving flexibility in hours ofwork and promoting a better transition to full-time, permanent jobs,including through strengthening workers’ rights to request changesin working hours and the possibility to “reverse” from part-time tofull-time hours, iii) investing in transport infrastructure, iv) ensuring adesired take-up of policy measures, through measures like non-transferable or “take-it or lose-it” paternity leave and facilitatingaccess to available subsidies for women workers, and v) reducinggendered occupational segregation through policies that improvegender equality in the labour market.

3. The IMF’s recent work on gender equality

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

6

The Fund’s initial attempts at deepening policy advice on gender andoperationalising its own analysis are so far limited. Its analysis reliesalmost exclusively on examination of female labour forceparticipation, which comprises only one element of gender equality.Collectively, the Article IV reports do not draw upon the full breadthof research findings on the barriers to gender equality and the reportsvary widely in scope. The operationalisation to date of the findingsthrough surveillance represents only 5 per cent of the Fund’smembership and only one of the Fund’s core functions. The concernremains that existing activity does not provide a route to graduatingthis work from pilots to further institutionalisation via GuidanceNotes. As such the sustainability of this new approach, despite theobvious benefits to fulfilling the core of the IMF’s mandate, remains inquestion.

The Fund’s recent work on gender equality prompts the question ofwhat the IMF understands to be ‘macro-critical’ – the term it uses toindicate what falls within the IMF’s scope for policy interventions, andconsequently what lies outside of its mandate.

As discussed in Section 3, the bulk of the IMF’s recent work on genderapplies an FLFP lens. This is a natural choice for piloting genderanalysis in a macro-economic review. Identifying the connectionbetween gender inequality and a potentially significant increase inlabour supply, and therefore potential economic growth, is relativelystraightforward. While the amount of potential growth benefit variesper country, gaps in FLFP are prevalent across all countries and the2013 SDN demonstrates the significant gains to be made in everyeconomic context. For the purposes of establishing gender equality asmacro-critical and therefore relevant to the Fund’s mandate, theconsideration of FLFP is thus a welcome first step.

However, gaps in FLFP cannot be considered in a vacuum, detachedfrom the shifts in power relations and conditions required to enablewomen to join the formal labour market, such as safety, health,freedom from unpaid care burdens and quality of work. Withoutconsidering these complex and interrelated structural, social andeconomic gender inequalities as underlying causes and FLFP gaps as asymptom of those causes, the IMF’s analysis and policy advice willremain incomplete.

Violence, for example, affects women and girls in their ability to attainlivelihoods and economic participation in a variety of ways. Somewomen are prevented from working in the formal sector by violence,while others may be prevented from controlling their income at homethrough violence. Violence is also often experienced by women at oron their way to the workplace and can restrict girls in accessing theireducation, such as when child marriage forces girls to leave schoolprematurely.²⁷

Violence against women and girls can therefore not only be a causeof FLFP gaps, but it is also integrally linked to other areas that arerecognised as being ‘macro-critical’, such as health and education, asstudies from the World Bank have indicated.²⁸ The World Bankfurther estimated lost productivity resulting from intimate partnerviolence alone ranged from 1.2 to 2 per cent of GDP annually acrosscountries, not including costs associated with long-term emotionalimpacts and second‐generation consequences.²⁹ Addressing andpreventing violence against women and girls requires a variety ofmeasures by a variety of institutions and stakeholders. Somemeasures, such as creating fiscal space to protect minimum socialspending floors for public expenditures on prevention andawareness education, fall directly within the IMF’s mandate. It istherefore crucial that the Fund recognise the macro-criticaldimensions of violence against women and girls when prescribingmacro‐economic policies.³⁰

The link between underlying structural gender inequalities and themacro-critical mandate of the IMF is also revealed by therecommendations made in several 2015 Article IV reviews forcomprehensive public childcare provision as a means of increasingFLFP. This approach implicitly recognised that womendisproportionately carry the burden of child care. If that barrier wereto be recognised comprehensively however, promoting women’ssexual and reproductive health rights (SRHR) would naturally followas another way of shifting this time burden away from women.Extensive evidence from the WHO, UN Women, UNFPA, UNICEF andothers has documented how promotion of SRHR can lead tosignificant micro- and macro-economic gains as it reduces healthcarecosts, improves productivity and increases rates of education.³¹ Justas with violence against women and girls, SRHR is therefore not onlyintegrally linked to established macro-critical issues, but can also beconsidered macro-critical as a standalone issue. Yet, while the 2013SDN recognises fertility as a factor in determining FLFP, it falls shortof recommending the importance of sufficient fiscal space toprovide critical SRHR services. Comprehensively addressing unpaidcare burdens as barriers to female labour force participation wouldalso entail recognising that women do not only disproportionatelycarry the burden of care for children, but also spend significantamounts of time on other types of unpaid care work, such as caringfor the sick and elderly and water and firewood collection.³² Policyadvice that neglects these structural barriers will remain incomplete.

This analysis can be extended to a range of other interrelatedstructural inequalities, such as occupational gender segregation; thegender pay gap; lack of decent work for women; women’s power indecision making; access to and control over land, property andfinancial services; the role of men and boys in achieving genderequality; and addressing deeply-rooted social and cultural norms andpower structures. All of these inequalities have macro-criticaldimensions and thus could fall under the purview of the IMF.

4. Reconsidering Macro-Criticality

7

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

Similarly, just as the exclusion of women from the labour marketcauses economic inefficiencies, so does the exclusion of othergroups, such as persons with disabilities, who represent 15 per centof the total population but are disproportionately representedamong the poorest and most marginalised, and are excluded fromopportunities to access and develop jobs and livelihoods.³³ Achievingfull and productive employment and decent work, including forpersons with disabilities as described in SDG 8.5, should thereforealso be considered part of the IMF’s mandate.

However, this is not to say that the Fund should endeavour toprovide advice on how to combat violence against women or deliverSRHR services, or provide lending for specific gender equalityprogrammes. Not only would such activities fall outside the mandateand expertise of the IMF, but they fall within the scope of otherinstitutions such as the World Bank, UN Women and nationalgovernments, with which the IMF should collaborate to betterunderstand the gendered dimensions of macro-economic policy.Rather, within its unique and specialised role of promoting globaleconomic growth and financial stability, the IMF should expand itsunderstanding of what it deems macro-critical in recognition of thefull macro-economic spectrum of gender equality.

The IMF has long faced criticisms of the macro policies it imposesthrough lending conditionalities. The criticisms have highlightedconditionality-driven reforms that have caused regressive shifts inthe distribution of power, income and wealth, and whichdisproportionately affected women and men living in poverty. TheIMF’s approach has subsequently evolved, in particular in the lastdecade. The IMF now claims to have moved towards a focus onreducing the number of conditionalities and providing greatercountry ownership. This has included endorsing the use of socialprotection floors in low-income countries to safeguard minimumspending on social provision such as health or education. Since July2015, the Fund has committed to providing Rapid Credit Facility loansto low-income countries at zero per cent interest permanently.Scepticism persists, however, as to whether the IMF’s approaches toits most influential functions have fully reflected these changes.³⁴Despite the IMF’s professed move toward fewer conditionalities,greater country ownership and (in the case of LICs) recognition ofthe need to protect key social provisions, recent studies haveidentified the IMF’s influence on macro-economic policy through itssurveillance function as a main contributing factor to theimplementation of deep and prolonged austerity measures indeveloping countries.³⁵

The ILO comprehensively investigated this question for the periodfollowing the 2008 financial crisis. It examined IMF government

spending projections contained in the World Economic Outlookdatabase for 187 countries, covering the period between 2015 and2020, and IMF country surveillance reports for 183 countries from2010 to 2013.³⁶ It found that, after an initial period where the IMFdiscouraged excessive cuts to spending and contractionary fiscalpolicy, the IMF subsequently strongly advised public spending cutsand austerity measures across the board from 2010 that werepremature in terms of economic recovery.³⁷ Two IMF papers thatyear called for large-scale fiscal adjustment to be initiatedimmediately, “even in countries where the recovery is not yetsecurely underway”.³⁸ The ILO review argued that these “suggestedreforms became mainstream policy advice in a majority of countriesaround the world after 2010 and shaped the direction embraced bythe economic adjustment programmes agreed with countries facinga sovereign debt crisis”.³⁹ Austerity measures recommended by theIMF since 2010 included the elimination or reduction of subsidies (in132 countries); wage bill cuts or caps (in 130 countries); rationalisingand targeting of safety nets (in 107 countries); pension reforms (in105 countries); labour market reforms (in 89 countries); andhealthcare reforms (in 56 countries), as well as broadeningconsumption taxes (in 138 countries) and privatising state assets andservices (in 55 countries).⁴⁰ Four of these conventional policies willbe examined below in light of the IMF’s commitment to genderequality in the context of the SDGs.

Wage bill cuts or caps

Cutting, capping or freezing public sector wages remained afrequent IMF policy recommendation. These reforms are attractivebecause public sector wages comprise what is often the largestshare of national budgets, but such measures often have adepressive effect on salaries of teachers, health staff and local civilservants. In its lending arrangements, the IMF included wage billceilings as a criterion in 17 countries between 2003 and 2005,positioning wage bills cuts directly within IMF conventional policy.⁴¹This trend continued, as 96 developing countries and 34 high-incomecountries in total considered this policy stance according to Article IVreports from 2010 to 2013.⁴² More recently, in Zimbabwe, the IMFcalled for the government to “reign in employment costs” from 82per cent of government spending to 52 per cent by 2019.⁴³ Similarly,the 2015 IMF review of Jamaica argued that “efforts are urgentlyneeded to sustainably lower the wage bill by creating a smaller andmore effective public sector. Such efforts should begin immediatelysince they will take time to yield results.”⁴⁴

In the context of the IMF’s commitment to gender equality, cutting,capping or freezing wages or recruitment in the public sector isperhaps one of the most clear-cut ways in which macro-economicpolicy can undermine gender equality, as such policiesdisproportionately affect women.

5. Conventional Policy Impacts

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

8

Women make up 58 per cent of the total public sector workforce inOECD countries, as compared to the whole economy where femaleemployment as a share of total employment only reaches 45 percent.⁴⁵ The public sector is also one of the main employers of womenin developing nations. ILO data for 49 developing and transitioncountries show that the share of women in public sector employmentexceeded their share in total employment in a majority of countries.⁴⁶Women tend to have more opportunities in civil service due togovernmental policies on equality of opportunity and treatment, aswell as flexible working hours and relative job stability. Wage bill cutsalso often include teachers and nurses, which are positionspredominantly held by women. However, within the public sectorwomen are also often clustered in lower-level and lower-paidadministrative positions, which are more vulnerable under IMF-proposed public sector wage cuts. Recommending increasing FLFPwhile cutting or capping the public sector wage bill can therefore becontradictory and requires gender impact analysis.

Labour market reforms

Reforms in the labour market commonly prescribed by the IMFgenerally include lowering minimum wages, limiting salaryadjustments to cost-of-living benchmarks, decentralising or limitingcollective bargaining and thereby weakening unions’ bargainingpower, and relaxing dismissal regulations. Commonly called labourflexibilisation, such measures were considered by 49 developing and40 high income countries as reflected in the Article IV reports of 2010to 2013.⁴⁷ In Germany’s 2015 Article IV report, the IMF argued againstmeasures to strengthen the negotiating power of workers to increasewages.⁴⁸ After the 2008 financial crisis collective bargaining reformswere also a notable criterion in IMF lending programmes to Portugal,Greece, Spain and Romania. In the latter case, a 2011 StandbyAgreement abolished the national collective agreement that hadpreviously set the national minimum wage and basic conditions for allRomanian workers. An ITUC report noted that “in the eighteenmonths since the labour reforms were introduced in Romania,collective bargaining has been reduced by two‐thirds.”⁴⁹

In the context of an economy where women’s position in the formallabour force is already disproportionately vulnerable, labourflexibilisation measures can further set back gender equality as itundermines the quality and conditions under which women work. UNWomen has found that collective action, or union-based bargaining,has in fact been crucial to improving women’s access to decent work,introducing childcare services, lowering gender pay gaps and attainingsafe working conditions.⁵⁰ In that light, Germany’s 2015 Article IVreview calling for increased high quality childcare while discouragingmeasures to strengthen the negotiating power of workers seemsinconsistent.⁵¹ The 2015 Article IV review of India also found that legalreform to allow women to work night shifts was reported as asuccessful move towards attaining higher FLFP.⁵²

It neglected, however, to include recommendations forexpenditures on supportive interventions such as safe transportprovision to safeguard against such reforms potentially exposingwomen to more violence, as illustrated by the recent multiple high-profile rape cases in India related to women returning late at nightfrom work.⁵³ Therefore, without policy measures ensuring theprotection of the quality and conditions under which women join theformal labour force, labour flexibilisation measures can significantlyundermine gender equality and the achievement of SDG 5.

Healthcare reforms

Healthcare reforms endorsed by the IMF have often comprisedincreased user fees and co-payments, rationalising healthcarebenefits for vulnerable groups, and expenditure cuts in public healthcentres and hospitals, including reductions in medical personnel.⁵⁴The impacts of the latter can be further compounded by publicsector wage bill cuts, which often also target medical personnel.Such reforms were considered in 34 developing countries and 22high‐income countries between 2010 and 2013.⁵⁵ In Jordan’s 2015Article IV review, the IMF endorsed the adoption of measures “toreduce health funds outlays, focused on streamlining the eligibilitycriteria for medical treatment”.⁵⁶ The 2015 Article IV review of Austriasimilarly called for cutting “about a quarter of current healthexpenditures [or] 2 per cent of Austria’s GDP”.⁵⁷ Cambridge scholarsargued in 2015 during the height of the Ebola crisis that the IMF hadpromoted policies in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone between 1990and 2014 through its lending conditionalities that “contributed tounderfunded, insufficiently staffed and poorly prepared healthsystems in the countries with Ebola outbreaks”.⁵⁸

Health care reforms as endorsed or required by the IMF havegendered impacts in three specific ways. Women and girls havedifferent and arguably more health care needs than men and boysfor biological and societal reasons. For example, globally, 830women suffer preventable deaths every day due to complicationsfrom pregnancy and child birth.⁵⁹ Women also tend to have lessaccess to regular medical care and are more likely to bemalnourished. Cutting national health care budgets or rationalisingbenefits may therefore disproportionately impact women’s and girl’shealth simply because they have a greater need for it.⁶⁰

Second, increasing user fees and co-payments directly anddisproportionately impacts women and girls because of their lack ofaccess to resources and inequitable decision-making power on howto spend household resources. Women are less likely than men to bein a position to afford increased user fees for their own care. Girlsare especially vulnerable to being cut off from health services as feesincrease and their health needs are de-prioritised by restrictive socialnorms.⁶¹

9

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

Finally, health care reforms impact women and girlsdisproportionately because the burden of replacing these serviceswith unpaid care work most often falls on them. Such policies cansimply shift the work predominantly to women and girls, asdemonstrated by data from, amongst others, the World Bank, UNWomen, the ILO and the OECD.⁶² This dynamic of shifting unpaid carework to women and girls goes largely unrecognised, but it raises twokey challenges to the IMF’s approach. First, an increased healthcareburden on women’s time is a direct obstacle to their participation inthe labour market. Even in the European Union, for example, whereFLFP gaps are relatively small, “25 per cent of women report care andother family and personal responsibilities as the reason for not beingin the labour force, versus only three per cent of men”.⁶³ The IMF’srecognition of FLFP gaps as macro-critical therefore suggests thatany health care reforms it advocates should also be recognised asimpacting upon and potentially undermining women’s economicempowerment. Second, unequal care burdens expose women andgirls to greater health risks, causing more strain on the health caresystem and undermining their ability to participate in the labourforce. A prominent example is the case noted above of Liberia,Guinea and Sierra Leone in the wake of the Ebola crisis. Studies foundthat the disease disproportionately affected women and girls, largelybecause of their wide-ranging roles as caregivers, nurses andmothers, as well as economic agents in the informal sector”.⁶⁴Therefore, if gender gaps are deemed macro-critical, health carereforms that undermine gender equality must be consideredinconsistent with pursuing economic growth as well.

Value-Added Taxes

A revenue-related approach the IMF often recommends to countriesas a way to stabilise their fiscal position is revising consumption-based taxes, such as increasing Value Added Taxes (VAT) or removingexemptions to them. As reflected in Article IV reports between 2010and 2013, 93 developing countries and 45 high-income countriesconsidered these policies, making it “the most prominent revenueside [policy] considered in response to fiscal pressure”.⁶⁵ In its mostrecent 2015 Article IV reviews, the IMF called strongly for VATincreases in, amongst others, Indonesia, the Bahamas and the UnitedArab Emirates. It urged them to implement VAT policies immediately,resist any temptation to weaken VAT regimes, and consider VATincreases as a fast and simple way to achieve big revenue gains.During the 1990s, the spread of VAT was vast and it became a crucialcomponent of tax systems across the world, raising about $18 trillionin tax receipts – roughly one‐quarter of all government revenue.⁶⁶ TheIMF provides a substantial amount of TA on how to administer VAT,implicitly endorsing this approach to raising revenue. A 2001 IMFpublication celebrated that “well over half of all countries that haveintroduced a VAT during the last twenty years made use of [IMF]Fiscal Affairs Department advice in doing so, and the proportion hasbeen rising.”⁶⁷

For example, Kenya enacted VAT reform in September 2013 that“reduced the list of VAT exempt items from 400 to 30 and applied aflat rate of 16 per cent to everyday goods [including electricity].”⁶⁸ Asreported in its 2011 Article IV report, the draft VAT bill “reflectedinput from the IMF’s Fiscal Affairs and Legal Departments”.⁶⁹

VAT is a regressive tax, or one that sees the proportion of anindividual’s income expended on that tax fall as income increases.⁷⁰Consequently, poorer women and men pay a disproportionatelyhigh percentage of their income in VAT. This is aggravated byevidence across countries showing that women spend a greateramount of their earnings on the consumables often targeted by VAT,such as food, clothes and medicine, as a result of their high care-related work burdens.⁷¹ Imposing VAT, rather than more progressiveforms of taxation, can therefore disproportionately impact womennegatively.

From macro-critical to a comprehensive analytical framework

As the preceding chapters have demonstrated, the approachadopted towards gender equality in the IMF’s research since 2013and operationalised in certain surveillance reviews since 2015 is toadd FLFP to the list of issues considered macro-critical. While thisrecognition is indeed important, the IMF’s approach nonethelessrequires substantial adjustment as it fails to analyse howconventional IMF policies may already impact gender equality,including upon the capacity of women to engage in decent paidwork. This is reminiscent of an ‘add women and stir’ approach togender equality that does not challenge the structurally gendereddimensions of conventional IMF policy advice.⁷²

Article IV reviews, for example, are designed to focus only on themost important macro-economic developments, creatingcompetition amongst issues to be considered. Adopting genderequality only as an additional issue therefore risks side-lining it whena country is dealing with many other urgent macro-economic issues.Instead, the Fund should examine how its conventional macro-economic policy advice and orthodox approach to assessing policyimpacts could be adapted to promote gender equality.

The previous chapter demonstrated how four conventional IMFpolicies can at times undermine gender equality. Providingconventional policy advice while simultaneously acknowledging thesignificant potential macro-economic gains from closing gender gapstherefore seems inconsistent and can certainly becounterproductive. While outside the scope of this briefing, a casecould also be made for how other conventional policies that the IMFprescribes impact on gender equality. For example, the ILO studycited in Section 4 also identified rationalisation and further targetingof safety nets, and privatisation of state assets and services, asmacro-economic policies commonly prescribed by the IMF,considered by 107 and 55 countries respectively between 2010 and

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

1 0

Former UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and HumanRights Magdalena Sepúlveda Carmona recently argued that theFund’s approach to social protection is focused on streamlining andtargeting only the most vulnerable or poor populations, contrary tothe ILO’s alternative approach of universal social protection, andcould further undermine gender equality. Sepúlveda noted that suchunintended consequences appear in conditional social cash transferprogrammes, which can use women as instruments to improve theirfamily’s lives while increasing their unpaid care burdens.⁷⁴Privatisation of state assets also often leads to increased user fees,which, as argued above, can disproportionately impact women andgirls.

Similarly, many of the arguments on the gendered impacts of healthcare reforms made above can equally apply to streamlining otherpublic services such as education, infrastructure and social services.Each of these services has disproportionate direct impacts on womenand girls as recipients of those services as well as the indirect impactof shifting largely unpaid workloads to women and girls. The ILO andothers have also recently published evidence of the possible negativeconsequences of export-led growth strategies on women’s lives inLICs, while others have now published research demonstrating howinsufficient international efforts to end tax avoidance and evasion is agender equality issue.⁷⁵ In order to comprehensively and coherentlyaddress gender equality and contribute to SDG 5, the IMF shouldcritically analyse all of its conventional policy advice from two distinctgendered approaches that were developed in the earliest feministwriting on structural adjustment.⁷⁶

First, it should be recognised that all IMF policies impact men andwomen differently, even if they seem superficially ‘gender neutral’, asthey necessarily operate in highly gendered and unequal economicand social contexts. Notably this argument was endorsed inparagraph 22 of the 2013 IMF SDN on macro-relevant gender gaps.Economic gender gaps exist in nearly every conceivable indicator. Forexample, women now represent 40 per cent of the global formalwork force, with only 50 per cent of women above the age of 15working in formally recognised employment as compared to 75 percent of men.⁷⁷ Globally, it is estimated women earn 52 to 60 per centof men’s annual earnings.⁷⁸ Gender‐based occupational segregation –whereby women and men tend to be employed in differentoccupations (horizontal segregation) and at different levels, gradesor positions of seniority (vertical segregation) – is widespread,persistent and resistant to change.⁷⁹ Jobs typically performed bywomen are also widely considered less valuable from the outset, andpowerful positions of all kinds are predominantly occupied by men.For instance, out of the 49 finance ministers and central bankdirectors of the G20 who met in Ankara in November 2015, only fourwere women. In developing economies, women are 20 per cent lesslikely than men to have a bank account and have consistently lessaccess to financial services.⁸⁰

In virtually every country in the world, men spend more time onleisure each day while women spend more time on unpaid carework, such that women work more hours (paid and unpaid) thanmen every day despite their prevailing unemployment andunderemployment.⁸¹

Second, and more fundamentally, the argument can be made thatrather than endorsing neutral macro-economic policies that operatein unequal contexts, the IMF’s macro-economic policies arethemselves gendered, as they are predicated upon the hidden labourof women, such as unpaid care burdens, which underpin the overalllabour force. Policies focusing on increasing labour forceparticipation that do not recognise, redistribute and reducewomen’s unpaid care burdens can only exacerbate such structuralbarriers to equality. While an extensive account of this analysis liesbeyond the scope of this briefing, the UK Gender & DevelopmentNetwork’s 2016 briefing Making the Case for Macroeconomics inGender Equality Work offers a clear analysis that is applicable to theIMF’s approach.⁸²

In the wake of the Fund’s new findings recognising gender gaps as asignificant macro-economic issue, it is incumbent on the Fund toensure not only that none of its policies exacerbate existing gendergaps, but that they actively promote gender equality as a core partof achieving its mandate across all three of its core functions.

1 1

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

In the context of its commitment to support the SDGs, the IMF hasundertaken to deepen policy advice and conduct research on genderinclusion. Its approach to gender equality requires a critical andcomprehensive analytical framework because the IMF is a key actorin shaping the macro-economic policies that will make theachievement of women’s and girls’ rights possible.

This paper has shown that, to properly assess the potential of theIMF’s latest work targeting gender equality, it is necessary to alsoconsider the Fund’s conventional policy advice and how it mayimpact and at times even undermine gender equality.

The IMF’s gender-specific work has so far been limited to research,which is not designed to represent the views or decisions of theFund, and piloting of gender analysis in some surveillance reports.The surveillance pilots have suffered from a failure to make full use ofthe IMF’s research findings, and their results have consequently beenhighly varied. Perhaps most importantly, the research findings haveas yet only been incorporated into one of the IMF’s three corefunctions. From an institutional perspective, therefore, the IMF’sgender work has thus far been limited and has not been madeinstitutionally sustainable, as there remains an urgent need toexplore the implications for the IMF’s TA programmes and design ofits lending conditionalities.

Second, this analysis has demonstrated that the rationale used by theFund to consider gender equality as macro-critical, and therefore partof its mandate, can be applied to a wide range of issues that arecurrently not part of the IMF’s analysis or policy recommendations.While the Fund’s commitment to SDG 5 broadens its conventionalinterpretation of what it deems to be macro-critical, this needs to beaccompanied by a more comprehensive understanding of the fullmacro-economic spectrum of gender equality.

Finally, this analysis has shown that conventional IMF policy advice,which is most often fiscally contractionary and places emphasis onindirect tax revenue collection, has specific effects on genderequality. Elements such as wage bill cuts, labour market andhealthcare reforms, and VAT enhancement are still commonlyprescribed by the IMF and widely implemented at the national level.Each of these policies carries unintended negative impacts on genderequality in a variety of ways. Without critically and comprehensivelyreviewing its work from a gender perspective – and adjusting itsconventional policy advice accordingly – the IMF is at risk ofproviding inconsistent and counterproductive policy guidance.

Therefore, rather than falling outside the scope of its work, theIMF’s commitment to gender equality should be understood assquarely fitting within its mandate and furthermore as required by it.To avoid a limited approach to gender equality the IMF shouldsystematically institutionalise the findings of its gender work acrossits core functions. To do so comprehensively and consistently, theFund needs to move beyond FLFP and expand its understanding ofwhat it deems macro-critical in recognition of the entire macro-economic spectrum of gender equality, provide critical genderanalysis and reform its policies accordingly to enhance genderequality.

6. Conclusion

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

1 2

1. IMF ‘From ambition to execution: Policies insupport of the Sustainable Development Goals’ StaffDiscussion Note, September 2015, p. 4.

2. IMF ‘The IMF and the Sustainable DevelopmentGoals’ Factsheet, 29 March 2016.

3. Ibid.

4. See for example IMF gender publications, whichwere sporadic and specialised before 2013<http://www.imf.org/external/ns/cs.aspx?id=355>.

5. IMF ‘Articles of Agreement’.

6. Such as the World Economic Outlook, the GlobalFinancial Stability Report, analyses of spillover risksfrom systemically important countries, as well asregional outlook studies.

7. IMF ‘2014 Triennial Surveillance Review’ para. 17.

8. Ibid.

9. IMF ‘FY2015 Administrative and Capital Expensesand Output Cost Estimates’ August 2015, para. 2,IMF ‘Technical Assistance and Training Factsheet’ 29September 2015.

10. Ibid.

11. IMF ‘Lending Factsheet’ 21 September 2015.

12. IMF ‘2015 Annual Report: Tackling ChallengesTogether’ p. 43.

13. Ibid, p. 48.

14. IMF ‘Lending Factsheet’ 21 September 2015.

15. Council on Foreign Relations ‘The IMF’s GrowingPowers’ 6 October 2009.

16. See for example, Financial Times ‘As obituariesare written for the World Bank, the IMF is set tobecome indispensable’ BeyondBrics, accessed 18May 2016 <www.FT.com>.

17. See Bretton Woods Project’s guide to IMFresearch, 2014, ‘Inside the Institutions: IMFpublications’<www.brettonwoodsproject.org/2014/06/imf-publications/>.

18. IMF ‘Guidance Note for Surveillance underArticle IV Consultation’ March 2015, para. 81.

19. Ibid, fn. 55.

20. IMF ‘Women, Work and the Economy:Macroeconomic Gains from Gender Equity’ SDN,2013, para. 1.

21. IMF ‘Fair Play: More Equal Laws Boost FemaleLabor Force Participation’ SDN, 2015, para. 31.

22. The Gini coefficient is a measure of statisticaldispersion intended to represent the incomedistribution of a nation's residents, and is the mostcommonly used measure of inequality.

23. IMF ‘Catalyst for Change: Empowering Womenand Tackling Income Inequality’ SDN, 2015, para. 3.

24. IMF ‘India 2015 Article IV Consultation – StaffReport’ para. 37.

25. IMF ‘Sweden 2015 Article IV Consultation – StaffReport’ p. 19.

26. IMF ‘Chile 2015 Article IV Consultation – StaffReport’ p. 39.

27. UNFPA estimates one in every three girls indeveloping countries is married by the age of 18‘Marrying Too Young: End Child Marriage’ 2012.

28. World Bank ‘Intimate Partner Violence:Economic Costs and Implications for Growth &Development’ 2014, p. 25.

29. Ibid.

30. For widely accepted policy recommendationsto address violence against women and girls seefor example the 2013 Committee on the Status ofWomen ‘Agreed Conclusions on the elimination andprevention of all forms of violence against womenand girls’.

31. UN Foundation ‘Sexual and Reproductive Healthand Rights and the Post-2015 Development Agenda’Universal Access Project, p. 7-8.

32. IDS ‘Redistributing Unpaid Care Work – Why taxmatters for Women’s Rights’ Issue 109, January2016.

33. ADD International ‘Jobs and Livelihoods’ 2014,submission to the IDC.

34. See for example, Alfredo Saad-Filho ‘Growth,Poverty and Inequality: From Washington Consensusto Inclusive Growth’ UN DESA Working Paper No.100, 2011, p. 17, Mohammed Mossallem ‘IMF Policyin the MENA Region; Lessons unlearnt’ BrettonWoods Project 2015, and Kentikelenis, Stubbs andKing ‘IMF conditionality and development policyspace, 1985-2014’ Review of International PoliticalEconomy, 2016.

35. ILO ‘The Decade of Adjustment: A Review ofAusterity Trends 2010-2020 in 187 Countries’ ESSWorking Paper No. 53, 2015, p. 10.

36. For a full accounting of its methodology andscope, see ibid, p. 1.

37. Ibid.

38. IMF ‘Strategies for Fiscal Consolidation in thePost-Crisis World’ 4 February, 2010 p. 3, IMF ‘Exitingfrom crisis intervention policies’ 4 February, 2010.

39. ILO ‘The Decade of Adjustment: A Review ofAusterity Trends 2010-2020 in 187 Countries’ ESSWorking Paper No. 53, 2015, p. 9.

40. Ibid, p. 11.

41. IMF ‘Aid Scaling Up: Do Wage Bill Ceilings Standin the Way?’ 2006, Annexe II.

42. ILO ‘The Decade of Adjustment: A Review ofAusterity Trends 2010-2020 in 187 Countries’ ESSWorking Paper No. 53, 2015, p. 12.

43. IMF ‘Press Release No. 16/96’, The Herald‘Government to cut wage bill by 52 per cent’ March14 2016.

44. IMF ‘Jamaica 10th Review under theArrangement under the EFF Staff Report’ 2015, para.30.

45. OECD, Women, Government and Policy Makingin OECD Countries: Fostering Diversity for IG, 2014.

46. UN Women ‘Transforming Economies, RealisingRights’ Progress of the World’s Women 2015-2016,p. 114.

47. ILO ‘The Decade of Adjustment: A Review ofAusterity Trends 2010-2020 in 187 Countries’ ESSWorking Paper No. 53, 2015, p. 11.

E n d n o t e s

1 3

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

48. IMF ‘Germany 2015 Article IV Consultation StaffReport’ para. 19.

49. ITUC ‘Frontlines Report 2013’ p. 17.

50. UN Women ‘Transforming Economies, RealisingRights’ Progress of the World’s Women 2015-2016,p. 117.

51. IMF ‘Germany 2015 Article IV Consultation StaffReport’ para. 19 & para. 27.

52. IMF ‘India 2015 Article IV Consultation StaffReport’ p. 23.

53. Patel ‘Working the Night Shift’ 2010 p. 34.

54. See for example Stuckler and Basu ‘The BodyEconomic: Why Austerity Kills’ 2013, p. X.

55. ILO ‘The Decade of Adjustment: A Review ofAusterity Trends 2010-2020 in 187 Countries’ ESSWorking Paper No. 53, p. 12.

56. IMF ‘Jordan Seventh and Final Review under theStand-By Arrangement and Proposal for Post-Program Monitoring Staff Report’ para. 16.

57. IMF ‘Austria 2015 Article IV Consultation StaffReport’ para. 23.

58. Kentikelenis, King, McKee, Stuckler ‘TheInternational Monetary Fund and the Ebolaoutbreak’ The Lancet Global Health, February 2015.

59. WHO, ‘Maternal Mortality’ Fact sheet N° 348,November 2015.

60. See for example, WHO ‘A foundation toaddress equity, gender and human rights in the 2030agenda’ 2016.

61. For a more detailed analysis of genderedimpacts of health user fees in Africa, see forexample: Nanda ‘Gender Dimensions of User Fees:Implications for women’s utilization of health care’Elsevier Science, Reproductive Health Matters2002, p. 127.

62. World Bank ‘World Development Report’ 2012,p. 80, UN Women ‘Transforming Economies,Realising Rights’ Progress of the World’s Women2015-2016, p. 84, ILO ‘The unpaid care work - paidwork connection’ Working paper No. 86, 2009,OECD ‘Unpaid Care Work: The missing link in theanalysis of gender gaps in labour outcomes’,December 2014.

63. UN Women ‘Transforming Economies, RealisingRights’ Progress of the World’s Women 2015-2016,p. 84.

64. UNDP ‘Confronting the Gender Impact of EbolaVirus Disease in Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone’ 2015 p.2.

65. ILO ‘The Decade of Adjustment: A Review ofAusterity Trends 2010-2020 in 187 Countries’ ESSWorking Paper No. 53, p. 13.

66. IMF ‘The Modern VAT’ 2001 p. xi.

67. Ibid, p. xi.

68. ChristianAid, ‘Taxing men and women: whygender is crucial for a fair tax system’ July 2014, p. 6.

69. IMF ‘Kenya 2011 Article IV Review Staff Report’,para. 18.

70. Tax Research UK ‘Why VAT is regressive’ 2011.

71. ChristianAid ‘Taxing men and women: Whygender is crucial for a fair tax system’ 2014, p. 12.

72. Steans ‘Gender and International Relations’1998, p. 12.

73. ILO ‘The Decade of Adjustment: A Review ofAusterity Trends 2010-2020 in 187 Countries’ ESSWorking Paper No. 53, p. 11.

74. Magdalena Sepúlveda ‘Missing the biggerpicture for women’s economic empowerment?’ 75.Notes from CSO Forum Spring Meetings, 12 April2016, Washington DC, available athttp://tinyurl.com/bwpgender.

75. ILO ‘Export-led development, employment andgender in the era of globalization’ WP No 197, 2015,and i.e., ChristianAid, ‘Taxing men and women: whygender is crucial for a fair tax system’ July 2014.

76. Sparr ‘Mortgaging Women’s Lives’ 1994, Bakker‘The Strategic Silence: Gender and Economic Policy’1994.

77. IMF ‘Women, Work and the Economy:Macroeconomic Gains from Gender Equity’ SDN,2013, para. 6.

78. See for example WEF ‘The Global Gender GapIndex 2015’ Report Highlights, World Bank GenderData Portal.

79. UN Women ‘Transforming Economies, RealisingRights’ Progress of the World’s Women 2015-2016,p. 89.

80. WorldBank, ‘The Global Findex 2014’.

81. UN Women ‘Transforming Economies, RealisingRights’ Progress of the World’s Women 2015-2016,p. 84.

82. GADN ‘Making the Case for Macroeconomics inGender Equality Work’ 2016.

The IMF and Gender Equality: A Critical Analysis

1 4

B r e t t o n W o o d s P r o je c t3 3 - 3 9 B o w lin g G re e n L a n eL o n d o n E C 1 R 0 B JU n it e d K in g d o m

T h e B r e t t o n W o o d s P r o je c t is a nA c t io n A id - h o s t e d p r o je c t , U Kr e g is t e r e d c h a r it y n o . 2 7 4 4 6 7 , E n g la n da n d W a le s c h a r it y n o . 2 7 4 4 6 7 , S c o t t is hc h a r it y n o . S C 0 4 5 4 7 6 .

T e l: + 4 4 ( 0 ) 2 0 3 1 2 2 0 6 1 0E m a il: in f o @ b r e t t o n w o o d s p r o je c t .o r gw w w .b r e t t o n w o o d s p r o je c t .o r g

@ b re t t o n w o o d s p r

f a c e b o o k .c o m / B r e t t o n W o o d s P r o je c t

P u b lis h e r : B r e t t o n W o o d s P r o je c t

June 2016

A n y e r r o r s a n d o m is s io n s a r e s o le ly t h e r e s p o n s ib ilit y o f t h e a u t h o r s .

C o p y r ig h t n o t ic e : T h is t e x t m a y b e f r e e ly u s e d p r o v id in g t h e s o u r c e is c r e d it e d .