The Goshawk in Britain - British Birds · The Goshawk in Britain M. Marquiss and I. Newton As a...

Transcript of The Goshawk in Britain - British Birds · The Goshawk in Britain M. Marquiss and I. Newton As a...

The Goshawk in Britain

M. Marquiss and I. Newton

A s a result of deforestation and persecution, the Goshawk Accipiter gentilis was more or less exterminated in Britain by the late 19th

century, with only sporadic breeding thereafter (Hollom 1957, Newton 1972). From the late 1960s, however, the situation improved, with breeding pairs becoming established in several areas to form the basis of the present population. This paper reviews the current status of the species in Britain and gives some information on origins, breeding, mortality and diet, in an attempt to assess the main factors influencing numbers and distribution.

Current status Speculation on the numbers of Goshawks in Britain is rife. Optimistic estimates, based largely on hearsay and rumour, put the current breeding population as high as 145 pairs. The main idea giving rise to extravagant speculation is that Goshawks (traditionally thought of as secretive forest birds) must exist in large numbers to be seen even rarely. Thus, every sighting is held to be the tip of an iceberg, with as-yet-unreported populations living in the forest plantations that now clothe the hills in remote areas. This optimism has not been discouraged in previous publications on the status of Goshawks in Britain which have bemoaned the fact that many observers still withhold records (Brown 1976, Sharrock 1980). This paper should go some way to clarify the situation, since it incorporates much information previously unpublished. Moreover, the authors and their associates have systematically searched large areas of suitable woodland and have therefore been able to evaluate sight records as well as to say with some confidence that there are thousands of hectares of British forests unoccupied by Goshawks.

In some places, we have noted the presence of single birds which, despite vigorous display, apparently found no mate and did not breed. On two occasions, single birds built nests, and one of these laid and incubated eggs, though these proved, not unexpectedly, to be infertile. In other places where there were records of displaying pairs, we searched suitable habitat intensively, but produced no evidence of nests. In five such places, the woodland was so restricted that we could be certain that no nest was built. Thus, it seems that pairs have displayed regularly, sometimes in more than one year, in various places where they have not nested. This is not

[Brit. Birds 75: 243-260, June [982] 2 4 3

244 The Goshawk in Britain

unexpected, since non-breeding pairs are frequent among the larger raptors, particularly where food is in short supply or where territory holders include many individuals in immature plumage (Newton 1979).

It was usually obvious when Goshawks were using an area, since even non-breeders left plenty of signs (kills, droppings and moulted feathers) characteristic of the species. Where there were no such signs and nests only of Sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus were found, we suspected that Sparrow-hawks displaying above the canopy had been misidentified as Goshawks. An experienced observer is unlikely to confuse the species because they are so different in shape as well as in size. Inexperienced observers, however, may have been misled by the frequent statements in bird books that male Goshawks can be confused with female Sparrowhawks. Most Goshawks in Britain are of the large northern type (see later), so many females are larger even than Buzzards Buteo buteo, while all males are considerably larger than any Sparrowhawk, and three times as heavy.

In this paper, we are concerned mainly with breeding pairs or potential breeding pairs, so have ignored records of single birds and separated records of proven breeders from records of 'pairs seen'. The latter were likely to have overestimated the numbers of Goshawks present because they could have included some Sparrowhawks and the same individual Goshawk displaying over different places.

Another source of error in population estimates is the overlap between records from different observers, who seem to have operated unknown to one another. In one area, for example, we received records of the same nests from four different sources. We have therefore been conservative in our estimates, so as to ensure that the figures given represent the minimum

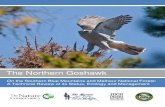

76. First-year Goshawk Accipiter gentilis mantling dead rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus. West Germany (Hansgeorg Arndl)

The Goshawk in Britain 245

numbers of pairs. If we had erred in the opposite direction for those records which were possibly of different pairs in the same county, we could have added only six nesting places and eight pairs of displaying birds to the total.

Records fall naturally into 'areas', often straddling county boundaries. The size and shape of these areas (labelled by code letters A-V, table 1) varied according to the number of sites encompassed, but none was larger than 1,650km2. Within areas, most sites were less than 10km apart (occasionally up to 40km), and no two areas were closer than 80km. Areas were widely distributed over mainland Britain, and only northwest Scotland provided no records. Although more than 90% of the recoveries of ringed Goshawks were within 40km of their birthplace (see later), there may have been some interchange between adjacent areas. For the most part, however, the separate populations appeared to have arisen independently of one another.

Since 1965, Goshawk nests have been found in at least 60 different places in 14 areas, and pairs have been seen at a further 34 places, including eight additional areas where breeding has not been proved. Far fewer places, however, were occupied in any one year, and, of 56 different places (including all known 'alternatives' for each place) that were checked in 1979 and 1980, nests were found at only 39 (70%): a poor result for what should be an expanding population. Of the 22 areas, nine were represented over the years by only one known site and only three of these were used for nesting in 1979 and/or 1980. Of the remaining 13 areas, only six have had more than three pairs present in any one year, and only five had more than three pairs in 1979-80. Only in two areas (A and B) can it be said that the numbers have continued to increase over the years. Area D had at least five pairs breeding as long ago as 1973 and now has only two known pairs. Taken together, these various observations imply that the future for Goshawks breeding in Britain is far from secure.

It is unlikely that we have been informed of every nest found or pair displaying, so the figures we give are minimum values. In all but one of the areas where Goshawks have been proved to breed, however, their presence has been recorded independently by people with different interests. For example, records of birds killed have come from every area where more than one pair has been known to breed, mostly from people different from those who found the nests. We therefore find it hard to believe that there are large, as yet undiscovered, populations of Goshawks breeding in remote parts of Britain. All the evidence indicates the contrary: that as soon as Goshawks become established, they are all-too-obvious to birdwatchers as they display, and to foresters and gamekeepers if they nest and rear young.

Origins Goshawks currently breeding in Britain are apparently not derived from Continental immigrants, but rather from birds which have escaped from falconers or been deliberately released. Both the geographical distribution and the timing of first breeding records are more consistent with the distribution of falconry activities and known releases than with natural colonisation (Kenward et al. in press). The Goshawks now breeding in

246 The Goshawk in Britain

Pai

rs

seen

bO <= ?

"O >

Yea

r(s)

2 e

Pair

s se

en

60 c c

"O > 4> 0

bree

ding

1

st p

rove

n pa

ir 1

st

reco

rded

A

rea

C J M M O CO W -

c n N ^ - f N O ^ - *

1979

19

80

1977

& 1

980

1973

19

76

1979

19

79 &

198

0

CM CM CM O CM CM —

co r-* ^ j * i n ^ ^ •*

CM •"*• —< —' CO CM U*>

TJ- [x co yp <N • * "4-

<£> to r- <& *-- i"- r-» <y> o i o i o as <n cr>

m co — m en to co ^D ^D r~̂ oo CTJ r^ t o 0") C) <Ti CTi C> CTi CT5

< « U Q W h O

o n n o o - o o o o — o o o o

CM O O O — O O — O — O O O O O

| 19

73, 1

977,

1

1979

& 1

980

1980

19

80

1978

19

73 &

197

7 19

76 &

197

9 19

71

1978

& 1

979

1977

19

80

1977

-80

1974

-78

1977

19

75

1976

o co eo — — i — < o o o o — — — —> —

CM O O — • — O — • — ' — — O O O O O

o n n « c N - o o o o - - " - -

o o o — * o - • — • — C M O O O O O

CM CO Gl , — 0 0 1^« Ch

r^ r^ to | r~- r-~ t^ r- i j 1 \ en 1 l o i a j I c n a i c T i c n l 1 [ 1 1

C7> cnC^C7)CT jC^CChC?JCT)C^O>C^C^a^CT>

X - - , i i j S z ; O o , a a i w h D >

o CM

CO

CO

o

Q Ed o 1 « P CT> O r-» O C7> o —• d 2 z

o CO

en m en

*̂ be c

•c 3 'B •S H *c 3 < « 8 " •S d g « Z O 2 H >-

1 gs 2 < 5 o ss

•s ° > e

i "E o

.*> H H3 as • g o

S H

S° * v a :

•"£ w • • & . H

| §

1 •s § o

i >• z 1 H

The Goshawk in Britain 247

Britain became established at a time when those in the Netherlands and other nearby parts of Europe were much reduced from pesticide poisoning. As Goshawks had not colonised Britain in the previous 70 years, they would have been even less likely to do so then. Moreover, most established populations are in western, rather than eastern, districts of Britain, farthest from Continental sources.

Goshawks have been released at least in areas B, E, H, M, N, Q and T, and in three of these areas breeding records followed within two years of the releases. Falconers are known to have lost birds in areas C, D, F, L and T and at least nine different breeding females and one male have been able to carry leather anklets, jesses or bells in areas A, B (2), C (2), E, F, H (male) andL(2) .

Kenward ei al. (in press) have estimated that each year since 1970 about 20 imported Goshawks have successfully entered the wild, and in this decade a further 30-40 have been purposefully released in small groups. This is sufficient to explain the present population and the proliferation of breeding records in new areas through the 1970s. As Kenward points out, it is at first sight surprising that the current population is not larger, but this can be explained by persecution (see later), the sedentary nature of the species, and the sporadic nature of most escapes, which presumably leaves many birds without a breeding partner.

In addition, the majority of Goshawks breeding in Britain are larger than the Continental Goshawks which one would expect to colonise Britain naturally by immigration. To judge from the lengths of moulted feathers found at nests (Marquiss unpublished), most are approximately the size of those breeding in the north and east of Europe, from whence came most imported Goshawks in the early 1970s. Thus, there is nothing in present evidence which is inconsistent with the view that recent British Goshawks have been derived entirely from falconry sources.

Breeding We have nest records of 177 breeding attempts from 1965 to 1980, chiefly after 1974. Most nests were in large blocks of mature woodland, but occasionally in woods as small as 3ha or in trees only 12m high. Of 66 nests where the tree species was recorded, 27% were in spruce Picea, 11% in Douglas fir Pseudotsuga menziesii, 18% in larch Larix, 15% in pine Pinus, 6% in beech Fagus sylvatica, 9% in oak Quercus and 14% in sycamore Acer pseudoplatanus. It seemed that nests were built in whatever species of tree was available; the openness of the tree stand appeared to be more important than the tree species, Goshawks tending to use more open woodland than Sparrowhawks nesting in the same area. Some of the places used by Goshawks had been used by Sparrowhawks in previous years, when the stand was denser. The height of nests above ground varied from 8 to 25m, depending on the size and species of tree, nests usually being placed just below the canopy or in the lower parts of it. Breeding activity sometimes began as early as February with display and nest building, and nests were sometimes lined several weeks before egg laying. On some territories, more than one nest was built or refurbished in the same year, but pairs usually

248 The Goshawk in Britain

Table 2. Laying dates, clutch-sizes, brood-sizes and Goshawks Aaipiter genlilis at various

Altitude (m)

301-400

201-300

101-200

1-100

1-400

DATE OF 1ST EGG

Mean ± SD in days (n) (range)

11 Apr ±9 .5 (11) (22 Mar to 23 Apr) 8 A p r ± 12.2(19)

(23 Mar to 26 Apr) 5 A p r ± 10.1 (8)

(2? Mar to 26 Apr) 26 Mar ±9.1 (9) (12 Mar to 8 Apr) 6 A p r ± 11.8(47) (12 Mar to 26 Apr)

2

0

1

1

1

3

CLUTCH-

Frequencie; 3 4

5 6

5 12

2 6

0 4

12 28

5

0

0

2

3

5

s 6

0

0

0

1

1

•SIZE

Mean ± SD

3.5 ±0.5

3.6 ± 0.6

3.8 ± 0.9

4.3+ 1.1

3.8 ± 0.8

concentrated their efforts in one particular part of a nesting wood and usually lined only the nest in which they eventually laid. At least eight breeding attempts involved individuals in first-year plumage (three males and seven females, including both members of two pairs), all in places where food was abundant.

Only 73 breeding attempts, drawn from 26 different nesting places, provided sufficient data to allow estimates of breeding performance in situations free from direct human influence. The date of first eggs varied from 12th March to 26th April, with most clutches started in the first week of April. The majority were of three or four eggs and most broods contained three young (table 2). From 47 fully incubated clutches which hatched at least one chick, 16 eggs failed to hatch: in most cases, a single addled egg from a clutch of four. The remaining discrepancy between clutch- and brood-sizes was due to the death of one or two young during hatch or in their first week. On only one occasion was an older chick known to die—at about three weeks of age. There were frequent instances of whole nest contents deserted, perishing or disappearing, but many were attributable to human interference, and are considered later.

In general, breeding performance was related to altitude (table 2), largely demonstrated by correlations between the altitude and mean laying date at particular nesting places (r=0.47, df= 17, F<0.05) and between the mean laying date and mean clutch-size (r=0.61, df= 15, P<0.01). The frequency of.addled eggs was greater at higher altitudes ( r s =l , P=0.05) and this, combined with the deaths of small young, led to a significantly smaller brood-size for places above 300m (t=2.6, df= 16, P<0.02).

Despite the large number of nests which failed completely, there were only three proven replacement clutches. In these, the first clutches were lost in the first two weeks of incubation, but early failure did not necessarily lead to replacement, as an additional seven clutches lost in early incubation were not replaced. On the other hand, all three repeats followed first clutches that had been laid earlier than average (in the last week of March). At least two of the replacement clutches were small (three eggs and one egg) and the resulting broods were also small (two of two young and a single).

The Goshawk in Britain

frequency of addled eggs in breeding attempts by altitudes in Britain during 1959-80

BROOD-SIZE

Frequencies 12 3 4 Mean ± SD

0 4 2

0 4 8

0 1 5

1 4 7

1 13 22

1

3

4

6

14

2.6 ±0.8

2.9 ±0.7

3.3 ±0.7

3.0 ± 0.9

3.0 ±0 .8

No. addled eggs per fully incubated

clutch (no. clutches)

0.60(5)

0.37(19)

0.30(10)

0.23(13)

0.34 (47)

Nes t fai lures Of the 177 recorded breeding attempts, only 101 (57%) produced fledged young. Some of the failures resulted from direct human interference, mainly by egg-collectors, gamekeepers and hawk keepers or their agents. Several carcases of shot or poisoned adults were found. Gamekeepers, by their own admission, were also responsible for the failure of some breeding attempts by removing nest contents or disturbing the breeding site until the nest contents perished. Clutches of Goshawk eggs collected in Britain have been seen in private collections and in one case the collector admitted the eggs were from a particular site. Similarly, some hawk keepers have admitted that their birds came from British nests and have named five specific sites.

To assess the effects of wilful human interference on production, we investigated the frequency and causes of total nest failure in six areas where there was proof of robbing or persecution, separately from five other areas where, in the absence of contrary evidence, we assumed that all failures were due to natural causes or to unintentional disturbance, such as tree-felling. Of 66 attempts in the latter areas, 55 (83.3%) produced fledged young; five (7.6%) nests were deserted, one clutch failed to hatch after full incubation, and in another nest the contents disappeared around hatching time (table 3). Two nests collapsed, one destroying a partly completed clutch and the other a brood of young about two weeks old, and tree-thinning operations led to desertion of one clutch and the death of a newly hatched brood.

In contrast, in areas where nest robbing and persecution occurred, only 46 (41.4%) of 111 breeding attempts were successful. Fourteen (12.6%) at tempts were proved to have failed due to persecution and 35 (31.5%) others failed in circumstances suggesting robbing or persecution. The failures of the seven nests where eggs or small young disappeared were probably also due to persecution, because five of these were at sites where wilful disturbance had occurred in previous years. Other failures were on average slightly less frequent than in the areas free of persecution, probably because many failures due to persecution or robbing occurred early in the breeding cycle, leaving fewer to fail subsequently from other factors. It is

249

250 The Goshawk in Britain

P (28 sites) No. %

111 46 41.4

10 9.0 4 3.6

15 13.5 13 11.7 7 6.3

6 5.4 7 6.3 0 1 0.9 1 0.9 1 0.9

NP (22 sites) No

66 55

0 0

0 0 0

5 1 1 0 2 2

.%

83.3

7.6 1.5 (1.5)

3.0 3.0

Table 3. Frequency and circumstances of nest failures of Goshawks Accipiier gentilis during 1959-80 in areas of Britain where persecution or robbing of nesting pairs was proved (P), compared with failures in other areas where causes of nest failure were

assumed to be free of wilful human interference (NP)

No. recorded breeding attempts No. (%) producing fledged young Failures proved due to wilful human interference:

Adults killed Disturbance leading to death of nest contents

Failures thought due to human interference because of circumstantial evidence: Tree climbed, eggs disappeared Tree climbed, young disappeared Disturbance followed by death of nest contents

Other failures: Nest deserted Eggs or small young disappeared Eggs failed to hatch All young died at hatch Nest collapsed Timber operations leading to death of nest contents

therefore not unreasonable to assume that the success rate in these areas would have been about 83%, and that robbing and persecution reduced this by about half, to 41%. Taking into consideration repeat layings, deliberate human interference resulted in a loss of an estimated 135 fledged young from 1965 to 1980 in those areas where nests have been monitored. Because gamekeepers were known to have climbed to some nests and removed their contents, it was impossible to estimate the proportion of failures due to egg-collectors or hawk keepers, but, if some well-known nests had not failed early due to one type of person, they would almost certainly have been robbed later by another.

Ringing recoveries and mortality of full-grown Goshawks From 1975 to 1980, at least 101 nestling Goshawks were ringed in Britain, and at least 14 were recovered, all but one within 40km of the birthplace. Two were trapped and released and another, which had hit a fence, was rehabilitated and also released. Of the other 11 recoveries, two were reported as road casualties, eight had been shot, trapped or poisoned, and the cause of death of the remaining one was unknown. The proportion recovered varied from area to area. In one where there were few gamekeepers, 25 Goshawks have been ringed and none recovered. In another area which had many private estates with gamekeepers, nine of the 37 Goshawks ringed have been recovered. In this area, it seems that, in recent years, gamekeepers have stopped reporting rings. One gamekeeper reported the ring on only the first Goshawk which he killed, though he later killed four others, at least three of which were also ringed. Furthermore, in 1980, two more ringed Goshawks were killed and reported to us, but neither was reported to the ringing office. This explains the reduction in recoveries

The Goshawk in Britain 251

in this area from six out of 13 ringed during 1976-77 to three out of 24 ringed during 1978-80. It also shows the high proportion of local young from successful nests which were removed in this way after becoming independent.

The evidence that many full-grown hawks have been killed in Britain (mainly by gamekeepers) is considerable when one takes into account (i) carcases found at breeding sites, handed into museums and private taxidermists or sent for post-mortem or chemical analysis; (ii) deaths reported to local recorders, or the ringing office; and (iii) the admissions of gamekeepers themselves, who on occasions also produced some Goshawk remains or a ring in support of their claims (table 4).

Of the 49 full-grown Goshawks recorded as killed by man since 1971, 13 were breeding adults at nesting sites (11 shot, one poisoned and one pole-trapped). Of those killed away from nests, at least four were falconers' birds, but most of the remaining 32 were thought to have been wild, as they were near breeding areas. At least eight were shot or pole-trapped at Pheasant Phasianus colchicus release pens, four of them within two months of fledging.

Table 4. Recorded deaths of full-grown Goshawks Actipiter gentilis in Britain during 1959-80

Killed Cause of (method

death not unknown Collision specified) Trapped Shot Poisoned

Deaths reported to local recorders or to ringing office 2 2 3 1 8 0

Carcases found, sent for post-mortem or analysis, to museums or to private taxidermists 0 2 0 2 15 4

Reports from gamekeepers, mostly substantiated 0 0 9 5 2 0

TOTALS 2 4 12 8 25 4

Food In Britain, as elsewhere (Glutz von Blotzheim et al. 1971, Opdam et al. 1977), breeding Goshawks took a wide variety of prey, as large as the brown hare Lepus capensis or as agile as the Sparrowhawk, the proportion of different species in the diet being largely determined by their availability. Thus, in any one area, the major part of the diet consisted of the most abundant species of medium-sized mammals, particularly squirrels Sciurus, rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus and hares, and large birds, particularly Wood-pigeons Columba palumbus, feral Rock Doves C. livia, grouse (Tetraonidae) and partridges Alectorisl Perdix (appendix 1).

From 30 different nesting sites, 848 prey items were recorded between March and August in the years 1974-80. There were insufficient records from particular sites to detect any variations between years in prey whose numbers fluctuate greatly, such as mountain hare Lepus timidus or Red

252 The Goshawk in Britain

Grouse Lagopus lagopus. For four sites, there were enough records from all parts of the breeding season to show a significant variation between months in the composition of prey brought to the nest (x2=34.4, df=9, P<0.001). This was largely due to peaks in the numbers of game-birds taken in spring (March to May) and in August (table 5). Rabbits were taken from spring through to July, and hares mainly in June. Doves and pigeons occurred throughout the season, forming a slightly lower proportion in July and August when the diet became more diverse, including appreciable numbers of other large birds (particularly crows), and small numbers of other passerines. Table 5. Variation between months in number of prey items brought to four nests of

Goshawk Accipiter gentilis in Britain All nests were 190-240 m above sea level

Prey

Rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus Hare Lepus Red squirrel Sciurus vulgaris Game-birds (Galliformes) Pigeons Columba 13 other species

March/ April

No. %

4 25.0 0 — 0 — 6 37.5 5 31.3 1 6.3

May No. %

9 21.4 0 — 2 4.8

16 38.1 13 31.0 2 4.9

June No. %

39 24.2 31 19.3 4 2.5

30 18.6 47 29.2 10 6.2

July-No. %

34 28.1 9 7.4 7 5.8

33 27.3 23 19.0 15 12.4

August No. %

14 14.9 7 7.4 0 —

33 35.1 19 20.2 21 22.3

Total items 16 42 161 121 94

The Goshawk in Britain 253

These prey figures were perhaps unrepresentative for Britain as a whole, because many records came from upland areas, where the diet was dominated by moorland species. It is likely that Goshawks in lowland areas have a distinctly different diet (e.g. Kenward 1979 showed that Goshawks temporarily released in Oxfordshire in winter 1974/75 preyed mainly on Woodpigeons, rabbits and Moorhens Gallinula chloropus). We therefore segregated food data by altitude (appendix I) and some general trends emerged (table 6). At low-ground sites, more-diverse prey were recorded, with more species forming a substantial (>5%) part of the diet (r=0.70, df= 10, F<0.02), whereas, on higher ground, a single major prey species contributed a greater proportion of the total food (rs=0.61, N=12, P<0.05). On low ground, the principal prey species for individual sites were red squirrel Sciurus vulgaris, Woodpigeon or rabbit, but above 250m Red Grouse usually outnumbered all other prey. Although Goshawks nested in woodland, open-country prey—such as hares, grouse or partridges—were between 16% and 90% of the diet, this proportion increasing with altitude (r=0.69, df=10, P<0.02). Conversely, strictly woodland species, such as squirrels, Woodcock Scolopax rusticola and Jay Garrulus glandarius, were taken more frequently at low-ground sites (r=0.70, df=10,/><0.02).

Table 6. Variation with altitude in composition of prey brought to nests of British Goshawks Accipiter gentilis

Number of different nest sites studied Total number ofitems recorded Total number of species recorded Number of species comprising more than 1 %

ofitems Proportion (%) ofitems comprising predominant

species Proportion (%) of all items that were woodland

species Proportion (%) of all items that were open-

country species

The relationships between prey-composition and altitude again reflected variation in prey availability. At lower elevations, land-use was more varied and habitats were more productive, giving a greater variety of abundant prey species. At high altitudes, moorland was one of the few habitats providing reasonably abundant prey of the right size, namely Red Grouse and mountain hares. Thus, above 300m, although Goshawks used woodland for nesting, they were dependent on adjacent open country for most of their food.

Organochlorme levels in unhatched eggs Persistent pesticides have been implicated in the declines of some raptor populations, partly through causing eggshell thinning and reduced breeding success (Ratcliffe 1970, Newton 1979). Twelve unhatched Goshawk eggs from Britain (representing nine clutches from six areas during

100

4 116 25

16

22.4

22.4

30.2

ALTITUDE ( M )

100-200

8 210 32

12

27.1

15.7

38.6

200-300

10 374 32

11

27.8

7.8

45.2

300-400

8 148 13

9

54.1

5.4

74.3

254 The Goshawk in Britain

Adult Goshawk Accipiter gentilis at nest with three young, Czechoslovakia, 1977 {Josef Hlasek)

1974-79) were analysed for organochlorine compounds. Compared with the eggs of some other birds of prey (Newton & Bogan 1974, Peakall 1976, Newton et al. 1978), these Goshawk eggs contained low organochlorine levels and the shells showed little or no thinning. The mean shell index of the five clutches represented was 2.16, which was only 3% less than the pre-DDT mean of 2.22 (based on 79 northwest European eggs examined by Anderson & Hickey 1974) (table 7). These findings were not unexpected because, in their breeding, Goshawks in Britain showed none of the other

The Goshawk in Britain 255

79. Adult Goshawk Accipiter gentilis leaving nest with three young, Czechoslovakia, 1977 (JoseJ H/asek)

symptoms (e.g. egg-breakage and high embryo-mortality) associated with substantial organochlorine contamination. It thus seems unlikely that persistent organochlorines have had a significant effect upon Goshawks in Britain in the years concerned.

Discussion The Goshawk is still one of the scarcest raptors breeding in Britain, being closer in abundance to the Osprey Pandion haliaetus and Red Kite Milvus

Table 7. Organochlorine levels and eggshell indices of undeveloped eggs from nests of British Goshawks Accipiter gentilis during 1974-79

DDE is the main terminal metabolite of DDT; PCBs are from industrial polychlorinated biphenyls; HEOD is from aldrin and dieldrin. Levels are given as ppm in lipid. Shell indices

are calculated using Ratcliffe's method (Ratcliffe 1970). * = trace

Year

1974 1975 1975 1975 1975 1976 1976 1977 1977 1977 1979 1979

Nest

1 2 3

4

5 6 7 8 9

Shell index

2.45 2.30 2.32 2.34 2.02 1.98 2.00 2.03 — —

DDE

4 3 6 5 6 6 7

12 10 7 * 1

PCBs

4 2

18 17 20 8

14 44 20 32 20 12

HEOD

4 1 1 1 2

21 17 2 1 4 2 1

256 The Goshawk in Britain

80. First-year female Goshawk Accipittrgentilis at nest, Denmark (Arthur Gilpin)

milvus than to the Hobby Falco subbuteo, which is the next most numerous species. Goshawks do not have stringent habitat requirements. They take a variety of prey, are able to hunt both in open country and in woodland, and nest in quite small woods, as well as large forests. Thus, the only parts of Britain unlikely to support breeding Goshawks are extensive tracts of open country devoid of woodland, and extensive planted hill forests which are devoid of suitable prey, unless they are adjacent to open country. Clearly, many more parts of Britain are suitable for Goshawks than are occupied at present.

The current breeding stock in localised pockets has arisen as a result of escapes or releases of captive birds and, because Goshawks are essentially sedentary, they are unlikely to colonise the rest of Britain rapidly. New areas may develop only by the slow expansion from existing centres, by further escapes or releases, or by deliberate translocations. Releases occur less frequently now than formerly (Kenward et al. in press) because, with licensing restrictions and quarantine requirements, it is more difficult and expensive to import Goshawks. The feral populations now established are, however, potentially highly productive. With about 80% of nesting attempts producing on average three young each, the production could be 2.4 young per attempt. Moreover, in a colonising species, one would expect first-year mortality to be less than usual because young birds do not have to disperse far to settle in places free of competition from older birds. It is difficult to estimate mortality because, in Britain, as in other areas (e.g. Scandinavia: Haukioja & Haukioja 1970), the biases introduced by persecution overemphasise the mortality of birds in their first year or two of

The Goshawk in Britain 257

life. This point is largely academic, however, because the British Goshawk population is still so small and localised that human interference—which has lowered production by half in some areas and caused the death of at least 49 individuals (13 of which were known to be breeding)—must inevitably have greatly curtailed numbers and distribution. Of the seven areas in Britain where two or more nests were found in any one year, robbing and persecution at the breeding site has occurred at five, and was worst at those designated A and D. The killing of Goshawks away from nests has occurred in all seven areas, but was worst in D and C. The populations of Goshawks at A and C are currently stable and probably increasing, albeit slowly. At D, where most of the known nests have been robbed and full-grown Goshawks frequently killed, known nests have declined from at least five in 1973 to two in 1980. So, once Goshawks had begun to breed in an area, the subsequent population trend depended primarily on the extent of persecution.

Although our records of pairs or nests came from 22 areas, nine of these were represented by only one known site, and only three of these nine were occupied during 1979-80. Records of one pair do not therefore offer much hope for the establishment of viable populations, and only the five areas where more than three pairs were found during 1979-80 can be considered as likely centres from which the British population may expand.

In view of the amount of persecution already suffered by British Goshawks from gamekeepers, it is pertinent to comment on the extent of Goshawk predation on game-birds. At lower altitudes, game-birds (mainly partridges) formed 22% of the prey brought to nests. Above 300m this rose to 5 4 % , made up exclusively of Red Grouse. Without some measure of the size of the grouse population, however, we could not say whether Goshawk predation reduced the numbers of grouse available for shooting. The figure of 5 4 % grouse in the diet was derived mainly from nests in areas and in years when grouse numbers were very high. As grouse numbers declined,

81. Female Goshawk Accipitergenlilis at nest with young, Sweden, June 1962 (Gunnar Lind)

258 The Goshawk in Britain

one Goshawk pair failed to lay and another deserted during incubation, but two other pairs turned to rabbits, hares and Woodpigeons in these years, and bred as usual. For all four pairs, it was clear that predation on grouse decreased markedly when there were fewer available, so the figure of 54% did not always apply.

Nowhere did we find Pheasants taken in numbers, but the fact that several Goshawks were killed at Pheasant release sites in autumn suggests that predation on Pheasants may increase at that season. In lowland Britain, alternative prey is abundant, so predation on Pheasants is unlikely to reach the levels it has in central Sweden (Kenward 1978), though of course there may always be local problems at Pheasant release pens. Viewed on a national scale, however, Goshawks are still too rare to be making serious inroads on game populations.

Acknowledgments Only about one-fifth of the data for this paper was collected by ourselves. Much of the remainder was provided by five amateur ornithologists who have not only recorded nest details, but repeatedly searched large areas of forest, often only to record the absence of Goshawks. All five wished to remain anonymous, convinced that the best interest of the birds is served by secrecy. We also acknowledge 53 other informants whose individual contributions were smaller, but in total no less significant. These people include local recorders (11), foresters (7), gamekeepers (5), falconers (4), reserve wardens (5), land-owners (2), museum staff (2), private taxidermists (2), and 16 others whose interest in the species is part of their general interest in birds. We wish to thank the RSPB for their full co-operation, in particular the species protection officers who kindly made available some data on persecution, and the Rare Breeding Birds Panel for asking observers to send information to us. Finally we are grateful to Dr J. Bogan who analysed the eggs for organochlorine content and Dr R. E. Kenward who criticised the paper in draft.

Summary 1. Since 1965, pairs or nests of Goshawks Accipiter gmtilis were known to us in 22 widespread areas of Britain. During 1979-80, only five of these areas held more than three known nests or pairs. The total nesting places known was 60, but only 39 (70% of those examined) were recorded as occupied during 1979-80. 2. The present population of Goshawks breeding in Britain is thought to have originated entirely from released birds or falconers' escapes, rather than from immigration. 3. In areas where persecution from people seemed lacking, 83% of nests produced young, whereas, in areas where wilful human interference was proved, only 41% of nests produced young. 4. In two areas, the killing of full-grown Goshawks (mainly by gamekeepers) was frequent, and, in the area where this was accompanied by nest robbing, the population has declined since it was discovered. Of 55 deaths of full-grown Goshawks known to us, at least 49 (89%) were of birds shot, poisoned, trapped, or killed by man in an unspecified manner. 5. Most clutches consisted of three or four eggs and most successful broods consisted of three young. 6. In lowland, Goshawks took a great variety of prey, especially pigeons Columba, squirrels Sciurus and rabbits Oryctolagus cuniculus, and no one species was of overriding importance. In upland, they fed mainly on a smaller variety of open-country prey, especially Red Grouse Lagopus lagopus and hares Lepus. 7. The levels of persistent organochlorines in unhatched eggs were low and seem unlikely to have had any significant effect on Goshawks in Britain. 8. Although Goshawks are still among the scarcest of British raptors, they do not have stringent habitat requirements. The main factor currently limiting their population expansion appears to be persecution. At this stage, the species could still be wiped out again in this country.

The Goshawk in Britain 259

82. First-winter female Goshawk Accipitergentilis, Sweden, February 1981 (Bjt'n Huseby)

References ANDERSON, D. VV., & HICKEY, J. J. 1974. Eggshell changes in raptors from the Baltic region.

Oikos 25: 395-401. BROWN, L. 1976. British Birds of Prey. London. CRAMP, S., & SIMMONS, K. E. L. (eds.) 1980. The Birds of the Western Palearctic. vol.2. Oxford. GLUTZ VON BLOTZHEIM, U. N., BAUER, K., & BEZZEL, E. 1971. Handbuch der Vbgel Mitteleuropas.

vol. 4. Frankfurt am Main. HAUKIOJA, E., & HAUKIOJA, M. 1970 Mortality rates of Finnish and Swedish Goshawks

(Accipitergentilis). Finnish Game Research 31: 13-20. HOLLOM, P. A. D. 1957. The rarer birds of prev, their present status in the British Isles:

Goshawk. Bnl. Birds 50: 135-136. KENWARD, R. E. 1978. Birds of prey as economic problems. In GEER, T. G. (ed.) Birds of Prey

Management Techniques. British Falconers' Club. 1979. Winter predation by Goshawks in lowland Britain. Brit. Birds 72: 64-73.

, MARQUISS, M., & NEWTON, I. In press. Goshawk re-establishment in Britain—causes and implications.,/. Wildlife Management.

NEWTON, I. 1972. Birds of prey in Scotland: some conservation problems. Scot. Birds 7: 5-23. 1979. Population Ecology of Raptors. Berkhamsted. & BOGAN, J . 1974. Organochlorine residues, eggshell thinning and hatching success in

British Sparrowhawks. Nature 249: 582-583. ——, MEEK, E., & LITTLE, B. 1978. Breeding ecology of the Merlin in Northumberland. Brit.

Birds 71: 376-398. OPDAM, P., THISSEN, J., VERSCHUREN, P., & MUSKENS, G. 1977. Feeding ecology of a

population of Goshawks (Accipiter gentilis). J. Orn. 118: 35-51. PEAKALL, D. B. 1976. The Peregrine Falcon (Falco peregrinus) and pesticides. Canadian Field

Naturalist 90: 301-307. RATCLIFFE, D. A. 1970. Changes attributable to pesticides in egg breakage frequency and

eggshell thickness in some British birds. J. Appl. Ecol. 7: 67-115. SHARROCK, J . T. R. 1980. Rare breeding birds in the United Kingdom in 1978. Brit. Birds 73:

5-26.

Dr M. Marquiss, Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Bush Estate, Penicuik, Midlothian EH260QB; DrI. Newton, Institute of Terrestrial Ecology, Monks Wood Experimental

Station, Abbots Ripton, Huntingdon PE172LS

260 The Goshawk in Britain

Appendix 1. Number of prey items of Goshawks Accipiter gentilis recorded at British nest sites at different altitudes during March-August 1974-80

Number of nest sites: 4 at < 100m, 8 at 100-200m, 10 at 200-300m and 8 at 300-400m

ALTITUDE ( M )

<:100 100-200 200-300 300-400 Prey No. % No. % No. % No. %

Rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus Mountain hare Lepus timidus Brown hare L. capensis Red squirrel Sciurus vulgaris Grey squirrel S. carolinensis Water vole Arvicola terrestris Mouse/vole (Rodentia) Stoat Muslela erminea Weasel M. nivalis Common Frog Rana temporaria Mallard Anas plalyrhynchos Teal A. crecca Sparrowhawk Accipiter nisus Kestrel Falco tinnunculus Red Grouse Lagopus lagopus Black Grouse Lyrurus tetrix Capercaillie Tetrao urogallus Red-legged Partridge Alectoris ruj'a Grey Partridge Perdix perdix Pheasant Phasianus colchicus Moorhen Gallinula chloropus Lapwing Vanellus vanellus Golden Plover Pluvialis apricaria Woodcock Scolopax rusticola Curlew Numenius arquata Common Gull Lams canus Black-headed Gull L. ridibundus Stock Dove Columba oenas Feral Rock Dove C. livia Woodpigeon C. palumbus Turtle Dove Streptopelia turtur Cuckoo Cuculus canotus Little Owl Athene noclua Green Woodpecker Picus viridis Great Spotted Woodpecker

Dendrocopos major Skylark Alauda arvensis Rook/crow Corvus jackdaw C. monedula Magpie Pica pica Jay Garrulus glandarius Mistle Thrush Turdus viscivorus Song Thrush T. philomelos Redwing T. iliacus Blackbird T. merula Meadow Pipit Anthus pratensis Starling Slurnus vulgaris Chaffinch Fringilla caelebs Sparrow Passer

12 10.3 — — 20 17.2 — — — —

1 —

2 4 2

— — — — 11 11 3 2

— — — — — —

3 1

0.9

1.7 3.4 1.7

9.5 9.5 2.6 1.7

2.6 0.9

26 22.4 1

— — —

— —

3 2 1 2 1 1 1 2 1 2 1

—

0.9

2.6 1.7 0.9 1.7 0.9 0.9 0.9 1.7 0.9 1.7 0.9

16 18 2

13 2 1 2 1

_ —

1

— — —

7.6 8.6 1.0 6.2 1.0 0.5 1.0 0.5

0.5

38 18.1 1 3 2 7 6 1 1

— 2 2 1 1

— 4

0.5 1.4 1.0 3.3 2.9 0.5 0.5

1.0 1.0 0.5 0.5

1.9 57 27.1

— — —

1

— 1 2

— —

8 8 3

— 2

— 2 1

—

0.5

0.5 1.0

3.8 3.8 1.4

1.0

1.0 0.5

59 15.8 33 —

6 1

— 1

— —

1 1

— 2 1

8.8

1.6 0.3

0.3

0.3 0.3

0.5 0.3

104 27.8

— 3

— 3 9

— 1 2 3 1 2

— —

6

0.8

0.8 2.4

0.3 0.5 0.8 0.3 0.5

1.6 81 21.7

— —

1 —

— —

8 1 3

10 15 3

— 3 1 7 1 1

0.3

2.1 0.3 0.8 2.7 4.0 0.8

0.8 0.3 1.9 0.3 0.3

1 0.7 4 2.7

— — — — — — — — — — —

2 1.4 80 54,1

— — — — — — — — — — — —

1 0.7 22 14.9 21 14.2

— 4 2.7

_ —

1 0.7 — — —

2 1.4 7 4.7 1 0.7

— —

2 1.4 __ — — —

Total items 116 210 374 148