THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE -...

Transcript of THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE -...

1THE ENTREPRENEURIAL

PERSPECTIVE

C H A P T E R 1

Entrepreneurship and the Entrepreneurial Mind-Set

C H A P T E R 2

Entrepreneurial Intentions and Corporate Entrepreneurship

C H A P T E R 3

Entrepreneurial Strategy: Generating and Exploiting New Entries

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/31/09 9:19 PM Page 1

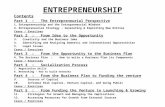

1To introduce the concept of entrepreneurship and explain the entrepreneurial process.

2To introduce effectuation as a way that expert entrepreneurs sometimes think.

3To develop the notion that entrepreneurs learn to be cognitively adaptable.

4To acknowledge that some entrepreneurs experience failure and to recognize the

process by which they maximize their ability to learn from that experience.

5To recognize that entrepreneurs have an important economic impact an an ethical and

social responsibility.

1ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THEENTREPRENEURIAL MIND-SET

L E A R N I N G O B J E C T I V E S

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/31/09 9:20 PM Page 2

3

O P E N I N G P R O F I L E

EWING MARION KAUFFMAN

Born on a farm in Garden City, Missouri, Ewing Marion Kauffman moved to Kansas City

with his family when he was eight years old. A critical event in his life occurred several

years later when Kauffman was diagnosed with a leakage of the heart. His prescription

was one year of complete bed rest; he was not even allowed to sit up. Kauffman’s

mother, a college graduate, came up with a solution to

keep the active 11-year-old boy lying in bed—reading.

According to Kauffman, he “sure read! Because nothing

else would do, I read as many as 40 to 50 books every

month. When you read that much, you read anything. So I read the biographies of all

the presidents, the frontiersmen, and I read the Bible twice and that’s pretty rough

reading.”

Another important early childhood experience centered on door-to-door sales.

Since his family did not have a lot of money, Kauffman would sell 36 dozen eggs col-

lected from the farm or fish he and his father had caught, cleaned, and dressed. His

mother was very encouraging during these formative school years, telling young Ewing

each day, “There may be some who have more money in their pockets, but Ewing, there

is nobody better than you.”

During his youth, Kauffman worked as a laundry delivery person and was a Boy

Scout. In addition to passing all the requirements to become an Eagle Scout and a Sea

Scout, he sold twice as many tickets to the Boy Scout Roundup as anyone else in Kansas

City, an accomplishment that enabled him to attend, for free, a two-week scout sum-

mer camp that his parents would not otherwise have been able to afford. According to

Kauffman, “This experience gave me some of the sales techniques which came into

play when subsequently I went into the pharmaceutical business.”

Kauffman went to junior college from 8 to 12 in the morning and then walked two

miles to the laundry where he worked until 7 P.M. Upon graduation, he went to work

at the laundry full time for Mr. R. A. Long, who would eventually become one of his

role models. His job as route foreman involved managing 18 to 20 route drivers, where

he would set up sales contests, such as challenging the other drivers to get more cus-

tomers on a particular route than he could obtain. Ewing says, “I got practice in selling

and that proved to be beneficial later in life.” R. A. Long made money not only at the

www.kauffman.org

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/31/09 9:20 PM Page 3

laundry business but also on patents, one of which was a form fit for the collar of a

shirt that would hold the shape of the shirt. He showed his young protégé that one

could make money with brains as well as brawn. Kauffman commented, “He was quite

a man and had quite an influence on my life.”

Kauffman’s sales ability was also useful during his stint in the Navy, which he joined

shortly after Pearl Harbor on January 11, 1942. When designated as an apprentice sea-

man, a position that paid $21 per month, he responded, “I’m better than an apprentice

seaman, because I have been a sea scout. I’ve sailed ships and I’ve ridden in whale

boats.” His selling ability convinced the Navy that he should instead start as a seaman

first class, with a $54 monthly salary. Kauffman was assigned to the admiral’s staff,

where he became an outstanding signalman (a seaman who transmitted messages from

ship to ship), in part because he was able to read messages better than anyone else due

to his previous intensive reading. With his admiral’s encouragement, Kauffman took a

correspondence navigator’s course and was given a deck commission and made a nav-

igation officer.

After the war was over in 1947, Ewing Kauffman began his career as a pharmaceu-

tical salesperson after performing better on an aptitude test than 50 other applicants.

The job involved selling supplies of vitamin and liver shots to doctors. Working on

straight commission, without expenses or benefits, he was earning pay higher than the

president’s salary by the end of the second year; the president promptly cut the com-

mission. Eventually, when Kauffman was made Midwest sales manager, he made 3 per-

cent of everything his salespeople sold and continued to make more money than the

president. When his territory was cut, he eventually quit and in 1950 started his own

company—Marion Laboratories. (Marion is his middle name.)

When reflecting on founding the new company, Ewing Kauffman commented, “It

was easier than it sounds because I had doctors whom I had been selling office supplies

to for several years. Before I made the break, I went to three of them and said, ‘I’m

thinking of starting my own company. May I count on you to give me your orders if

I can give you the same quality and service?’ These three were my biggest accounts

and each one of them agreed because they liked me and were happy to do business

with me.”

Marion Laboratories started by marketing injectable products that were manufac-

tured by another company under Marion’s label. The company expanded to other ac-

counts and other products and then developed its first prescription item, Vicam, a vitamin

product. The second pharmaceutical product it developed, oyster shell calcium, also

sold well.

To expand the company, Kauffman borrowed $5,000 from the Commerce Trust

Company. He repaid the loan, and the company continued to grow. After several years,

outside investors could buy $1,000 worth of common stock if they loaned the company

$1,000 to be paid back in five years at $1,250, without any intermittent interest. This

initial $1,000 investment, if held until 1993, would have been worth $21 million.

Marion Laboratories continued to grow and reached over $1 billion per year in

sales, due primarily to the relationship between Ewing Kauffman and the people in

4 PART 1 THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 4

the company, who were called associates, not employees. “They are all stockholders,

they build this company, and they mean so much to us,” said Kauffman. The concept

of associates was also a part of the two basic philosophies of the company: Those who

produce should share in the results or profits, and treat others as you would like to be

treated.

The company went public through Smith Barney on August 16, 1965, at $21 per share.

The stock jumped to $28 per share immediately and has never dropped below that level,

sometimes selling at a 50 to 60 price/earnings multiple. The associates of the company

were offered a profit sharing plan, where each could own stock in the company. In

1968 Kauffman brought Major League Baseball back to Kansas City by purchasing the

Kansas City Royals. This boosted the city’s economic base, community profile, and civic

pride. When Marion Laboratories merged with Merrill Dow in 1989, there were 3,400

associates, 300 of whom became millionaires as a result of the merger. The new com-

pany, Marion Merrill Dow, Inc., grew to 9,000 associates and sales of $4 billion in 1998

when it was acquired by Hoechst, a European pharmaceutical company. Hoechst Marion

Roussel became a world leader in pharmaceutical-based health care involved in the dis-

covery, development, manufacture, and sale of pharmaceutical products. In late 1999

the company was again merged with Aventis Pharma, a global pharmaceutical company

focusing on human medicines (prescription pharmaceuticals and vaccines) and animal

health. In 2002, Aventis’s sales reached $16.634 billion, an increase of 11.6 percent

from 2001, while earnings per share grew 27 percent from the previous year.

Ewing Marion Kauffman was an entrepreneur, a Major League Baseball team

owner, and a philanthropist who believed his success was a direct result of one funda-

mental philosophy: Treat others as you would like to be treated. “It is the happiest

principle by which to live and the most intelligent principle by which to do business

and make money,” he said.

Ewing Marion Kauffman’s philosophies of associates, rewarding those who produce,

and allowing decision making throughout the organization are the fundamental con-

cepts underlying what is now called corporate entrepreneurship in a company. He

went even further and illustrated his belief in entrepreneurship and the spirit of giving

back when he established the Kauffman Foundation, which supports programs in two

areas: youth development and entrepreneurship. Truly a remarkable entrepreneur,

Mr. K, as he was affectionately called by his employees, will now produce many more

successful “associate entrepreneurs.”

Like Ewing Marion Kauffman, many other entrepreneurs and future entrepreneurs

frequently ask themselves, “Am I really an entrepreneur? Do I have what it takes to be

a success? Do I have sufficient background and experience to start and manage a new

venture?” As enticing as the thought of starting and owning a business may be, the

problems and pitfalls inherent to the process are as legendary as the success stories.

The fact remains that more new business ventures fail than succeed. To be one of the

few successful entrepreneurs requires more than just hard work and luck. It requires

the ability to think in an environment of high uncertainty, be flexible, and learn from

one’s failures.

CHAPTER 1 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE ENTREPRENEURIAL MIND-SET 5

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 5

NATURE AND DEVELOPMENT OF ENTREPRENEURSHIP

Who is an entrepreneur? What is entrepreneurship? What is an entrepreneurial process?These frequently asked questions reflect the increased national and international interest inentrepreneurs by corporate executives, venture capitalists, university professors and stu-dents, recruiters, and government officials. To an economist, an entrepreneur is one whobrings resources, labor, materials, and other assets into combinations that make their valuegreater than before, and also one who introduces changes, innovations, and a new order. Toa psychologist, such a person is typically driven by certain forces—the need to obtain or at-tain something, to experiment, to accomplish, or perhaps to escape the authority of others.To one businessman, an entrepreneur appears as a threat, an aggressive competitor, whereasto another businessman the same entrepreneur may be an ally, a source of supply, a cus-tomer, or someone who creates wealth for others, as well as finds better ways to utilize re-sources, reduce waste, and produce jobs others are glad to get.1

Although being an entrepreneur means different things to different people, there is agree-ment that we are talking about a kind of behavior that includes: (1) initiative taking, (2) theorganizing and reorganizing of social and economic mechanisms to bundle resources in in-novative ways, and (3) the acceptance of risk, uncertainty and/or the potential for failure.2

Entrepreneurship is the dynamic process of creating incremental wealth. The wealth iscreated by individuals who assume the major risks in terms of equity, time, and/or careercommitment to provide value for some product or service. The product or service may ormay not be new or unique, but the entrepreneur must somehow infuse value by receivingand bundling the necessary skills and resources.3

To be inclusive of the many types of entrepreneurial behavior, the following definitionof entrepreneurship will be the foundation of this book:

Entrepreneurship is the process of creating something new with value by devoting the neces-sary time and effort; assuming the accompanying financial, psychic, and social risks and un-certainties; and receiving the resulting rewards of monetary and personal satisfaction.4

This definition stresses four basic aspects of being an entrepreneur. First, entrepreneur-ship involves the creation process—creating something new of value. The creation has tohave value to the entrepreneur and value to the audience for which it is developed. This au-dience can be (1) the market of organizational buyers for business innovation, (2) the hos-pital’s administration for a new admitting procedure and software, (3) prospective studentsfor a new course or even college of entrepreneurship, or (4) the constituency for a new serv-ice provided by a nonprofit agency. Second, entrepreneurship requires the devotion of thenecessary time and effort. Only those going through the entrepreneurial process appreciatethe significant amount of time and effort it takes to create something new and make it op-erational. As one new entrepreneur so succinctly stated, “While I may have worked asmany hours in the office while I was in industry, as an entrepreneur I never stop thinkingabout the business.”

The third part of the definition involves the rewards of being an entrepreneur. The mostimportant of these rewards is independence, followed by personal satisfaction, but mone-tary reward also comes into play. For some entrepreneurs, money becomes the indicator ofthe degree of success achieved. Assuming the necessary risks and uncertainties is the finalaspect of entrepreneurship. Because action takes place over time, and the future is un-knowable, action is inherently uncertain.5 This uncertainty is further enhanced by the nov-elty intrinsic to entrepreneurial actions, such as the creation of new products, new services,and new ventures.6 Entrepreneurs must decide to act even in the face of uncertainty over theoutcome of that action. Therefore, entrepreneurs respond to, and create, change through

6 PART 1 THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE

entrepreneur Anindividual who takesinitiative to bundleresources in innovativeways and is willing tobear the risk and/oruncertainty to act

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 6

their entrepreneurial actions, where entrepreneurial action refers to behavior in response toa judgmental decision under uncertainty about a possible opportunity for profit.7 We nowoffer a process perspective of entrepreneurial action.

THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PROCESS

The process of pursuing a new venture is embodied in the entrepreneurial process, whichinvolves more than just problem solving in a typical management position.8 An entrepre-neur must find, evaluate, and develop an opportunity by overcoming the forces that resistthe creation of something new. The process has four distinct phases: (1) identificationand evaluation of the opportunity, (2) development of the business plan, (3) determinationof the required resources, and (4) management of the resulting enterprise (see Table 1.1).Although these phases proceed progressively, no one stage is dealt with in isolation or istotally completed before work on other phases occurs. For example, to successfully iden-tify and evaluate an opportunity (phase 1), an entrepreneur must have in mind the type ofbusiness desired (phase 4).

Identify and Evaluate the Opportunity

Opportunity identification and evaluation is a very difficult task. Most good businessopportunities do not suddenly appear, but rather result from an entrepreneur’s alertness topossibilities or, in some cases, the establishment of mechanisms that identify potential op-portunities. For example, one entrepreneur asks at every cocktail party whether anyone isusing a product that does not adequately fulfill its intended purpose. This person is con-stantly looking for a need and an opportunity to create a better product. Another entrepreneur

CHAPTER 1 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE ENTREPRENEURIAL MIND-SET 7

entrepreneurial actionRefers to behavior inresponse to a judgmentaldecision under uncertaintyabout a possibleopportunity for profit

entrepreneurial processThe process of creatingsomething new with valueby devoting the necessarytime and effort, assumingthe accompanyingfinancial, psychic,and social risks anduncertainties, andreceiving the resultingrewards of monetary andpersonal satisfaction

Identify and Evaluate the Opportunity Develop Business Plan Resources Required Manage the Enterprise

TABLE 1.1 Aspects of the Entrepreneurial Process

• Opportunity assessment

• Creation and length ofopportunity

• Real and perceivedvalue of opportunity

• Risk and returns of opportunity

• Opportunity versus personal skills and goals

• Competitive environment

• Title page

• Table of Contents

• Executive Summary

• Major Section

1. Description of Business

2. Description of Industry

3. Technology Plan

4. Marketing Plan

5. Financial Plan

6. Production Plan

7. Organization Plan

8. Operational Plan

9. Summary

• Appendixes (Exhibits)

• Determine resourcesneeded

• Determine existing resources

• Identify resource gapsand available suppliers

• Develop access toneeded resources

• Develop managementstyle

• Understand key variables for success

• Identify problems andpotential problems

• Implement control systems

• Develop growth strategy

opportunity identificationThe process by which anentrepreneur comes upwith the opportunity for anew venture

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 7

always monitors the play habits and toys of her nieces and nephews. This is her way oflooking for any unique toy product niche for a new venture.

Although most entrepreneurs do not have formal mechanisms for identifying businessopportunities, some sources are often fruitful: consumers and business associates, membersof the distribution system, and technical people. Often, consumers are the best source ofideas for a new venture. How many times have you heard someone comment, “If only therewas a product that would . . .” This comment can result in the creation of a new business.One entrepreneur’s evaluation of why so many business executives were complaining aboutthe lack of good technical writing and word-processing services resulted in the creation ofher own business venture to fill this need. Her technical writing service grew to 10 em-ployees in two years.

Because of their close contact with the end user, channel members in the distributionsystem also see product needs. One entrepreneur started a college bookstore after hearingall the students complain about the high cost of books and the lack of service providedby the only bookstore on campus. Many other entrepreneurs have identified businessopportunities through a discussion with a retailer, wholesaler, or manufacturer’s repre-sentative. Finally, technically oriented individuals often conceptualize business opportu-nities when working on other projects. One entrepreneur’s business resulted from seeingthe application of a plastic resin compound in developing and manufacturing a new typeof pallet while developing the resin application in another totally unrelated area—casketmoldings.

Whether one identifies the opportunity by using input from consumers, business associates,channel members, or technical people, each opportunity must be carefully screened andevaluated. This evaluation of the opportunity is perhaps the most critical element of theentrepreneurial process, as it allows the entrepreneur to assess whether the specificproduct or service has the returns needed compared to the resources required. As indi-cated in Table 1.1, this evaluation process involves looking at the length of the opportu-nity, its real and perceived value, its risks and returns, its fit with the personal skills andgoals of the entrepreneur, and its uniqueness or differential advantage in its competitiveenvironment.

The market size and the length of the window of opportunity are the primary bases fordetermining the risks and rewards. The risks reflect the market, competition, technology,and amount of capital involved. The amount of capital needed provides the basis for the re-turn and rewards. The methodology for evaluating risks and rewards, the focus of Chap-ters 7 and 10, frequently indicates that an opportunity offers neither a financial nor a per-sonal reward commensurate with the risks involved. One company that delivered barkmulch to residential and commercial users for decoration around the base of trees andshrubs added loam and shells to its product line. These products were sold to the same cus-tomer base using the same distribution (delivery) system. Follow-on products are importantfor a company expanding or diversifying in a particular channel. A distribution channelmember such as Kmart, Service Merchandise, or Target prefers to do business with multi-product, rather than single-product, firms.

Finally, the opportunity must fit the personal skills and goals of the entrepreneur. It isparticularly important that the entrepreneur be able to put forth the necessary time and ef-fort required to make the venture succeed. Although many entrepreneurs feel that the desirecan be developed along with the venture, typically it does not materialize. An entrepreneurmust believe in the opportunity so much that he or she will make the necessary sacrificesto develop the opportunity and manage the resulting organization.

Opportunity analysis, or what is frequently called an opportunity assessment plan, is onemethod for evaluating an opportunity. It is not a business plan. Compared to a business

8 PART 1 THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE

window of opportunityThe time period availablefor creating the newventure

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 8

plan, it should be shorter; focus on the opportunity, not the entire venture; and provide thebasis for making the decision of whether or not to act on the opportunity.

An opportunity assessment plan includes the following: a description of the product orservice, an assessment of the opportunity, an assessment of the entrepreneur and the team,specifications of all the activities and resources needed to translate the opportunity into aviable business venture, and the source of capital to finance the initial venture as well as itsgrowth. The assessment of the opportunity requires answering the following questions:

• What market need does it fill?

• What personal observations have you experienced or recorded with regard to thatmarket need?

• What social condition underlies this market need?

• What market research data can be marshaled to describe this market need?

• What patents might be available to fulfill this need?

• What competition exists in this market? How would you describe the behavior of thiscompetition?

• What does the international market look like?

• What does the international competition look like?

• Where is the money to be made in this activity?

Develop a Business Plan

A good business plan must be developed to exploit the defined opportunity. For example, abusiness plan is often required to obtain the resources necessary to launch the business.Writing a business plan is a very time consuming phase of the entrepreneurial process. Anentrepreneur usually has not prepared a business plan before and does not have the re-sources available to do a good job. Although the preparation of the business plan is the fo-cus of Chapter 7, it is important to understand the basic issues involved as well as the threemajor sections of the plan (see Table 1.1). A good business plan is essential to developingthe opportunity and determining the resources required, obtaining those resources, and suc-cessfully managing the resulting venture.

Determine the Resources Required

The entrepreneur must determine the resources needed for addressing the opportunity.This process starts with an appraisal of the entrepreneur’s present resources. Any re-sources that are critical need to be differentiated from those that are just helpful. Caremust be taken not to underestimate the amount and variety of resources needed. The en-trepreneur should also assess the downside risks associated with insufficient or inappro-priate resources.

The next step in the entrepreneurial process is acquiring the needed resources in a timelymanner while giving up as little control as possible. An entrepreneur should strive to main-tain as large an ownership position as possible, particularly in the start-up stage. As thebusiness develops, more funds will probably be needed to finance the growth of the ven-ture, requiring more ownership to be relinquished. The entrepreneur also needs to identifyalternative suppliers of these resources, the focus of Chapter 11, along with their needs anddesires. By understanding resource supplier needs, the entrepreneur can structure a dealthat enables the resources to be acquired at the lowest possible cost and with the least lossof control.

CHAPTER 1 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE ENTREPRENEURIAL MIND-SET 9

business plan Thedescription of the futuredirection of the business

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 9

Manage the Enterprise

After resources are acquired, the entrepreneur must use them to implement the businessplan. The operational problems of the growing enterprise must also be examined. This in-volves implementing a management style and structure, as well as determining the keyvariables for success. A control system must be established so that any problem areas canbe quickly identified and resolved. Some entrepreneurs have difficulty managing and grow-ing the venture they created.

HOW ENTREPRENEURS THINK

Entrepreneurs think differently than nonentrepreneurs. Moreover, an entrepreneur in aparticular situation may think differently when faced with a different task or decisionenvironment. Entrepreneurs must often make decisions in highly uncertain environmentswhere the stakes are high, time pressures are immense, and there is considerable emo-tional investment. We think differently in these environments than we do when the natureof a problem is well understood and we have time and rational procedures at hand to solveit. Given the nature of an entrepreneur’s decision-making environment, he or she mustsometimes (1) effectuate, (2) be cognitively adaptable, and (3) learn from failure. We nowdiscuss the thought process behind each of these requirements.

Effectuation

As potential business leaders you are trained to think rationally and perhaps admonishedif you do not. This admonishment might be appropriate given the nature of the task, but itappears that there is an alternate way of thinking that entrepreneurs sometimes use, es-pecially when thinking about opportunities. Professor Saras Sarasvathy (from Darden,University of Virginia) has found that entrepreneurs do not always think through a problemin a way that starts with a desired outcome and focuses on the means to generate that out-come. Such a process is referred to as a causal process. Our description of the entrepre-neurial process in the preceding section reflects a causal explanation. But, entrepreneurssometimes use an effectuation process, which means they take what they have (who theyare, what they know, and whom they know) and select among possible outcomes. Profes-sor Saras is a great cook, so it is not surprising that her examples of these thought processesrevolve around cooking.

Imagine a chef assigned the task of cooking dinner. There are two ways the task can be organ-ized. In the first, the host or client picks out a menu in advance. All the chef needs to do is listthe ingredients needed, shop for them, and then actually cook the meal. This is a process ofcausation. It begins with a given menu and focuses on selecting between effective ways to pre-pare the meal.

In the second case, the host asks the chef to look through the cupboards in the kitchen forpossible ingredients and utensils and then cook a meal. Here, the chef has to imagine possiblemenus based on the given ingredients and utensils, select the menu, and then prepare the meal.This is a process of effectuation. It begins with given ingredients and utensils and focuses onpreparing one of many possible desirable meals with them.9

Sarasvathy’s Thought Experiment #1: Curry in a Hurry

In this example I [Sarasvathy] trace the process for building an imaginary Indian restaurant,“Curry in a Hurry.” Two cases, one using causation and the other effectuation, are examined.For the purposes of this illustration, the example chosen is a typical causation process that

10 PART 1 THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE

causal process Aprocess that starts with adesired outcome andfocuses on the means togenerate that outcome

effectuation process Aprocess that starts withwhat one has (who theyare, what they know, andwhom they know) andselects among possibleoutcomes

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 10

underlies many economic theories today—theories in which it is argued that artifacts such asfirms are inevitable outcomes, given the preference orderings of economic actors and certainsimple assumptions of rationality (implying causal reasoning) in their choice behavior. The cau-sation process used in the example here is typified by and embodied in the procedures stated byPhilip Kotler in his Marketing Management (1991: 63, 263), a book that in its many editions isconsidered a classic and is widely used as a textbook in MBA programs around the world.

Kotler defines a market as follows: “A market consists of all the potential customers shar-ing a particular need or want who might be willing and able to engage in exchange to satisfythat need or want” (1991: 63). Given a product or a service, Kotler suggests the following pro-cedure for bringing the product/service to market (note that Kotler assumes the market exists):

1. Analyze long-run opportunities in the market.

2. Research and select target markets.

3. Identify segmentation variables and segment the market.

4. Develop profiles of resulting segments.

5. Evaluate the attractiveness of each segment.

6. Select the target segment(s).

7. Identify possible positioning concepts for each target segment.

8. Select, develop, and communicate the chosen positioning concept.

9. Design marketing strategies.

10. Plan marketing programs.

11. Organize, implement, and control marketing effort.

This process is commonly known in marketing as the STP—segmentation, targeting, andpositioning—process.

Curry in a Hurry is a restaurant with a new twist—say, an Indian restaurant with a fast foodsection. The current paradigm using causation processes indicates that, to implement thisidea, the entrepreneur should start with a universe of all potential customers. Let us imaginethat she wants to build her restaurant in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA, which will thenbecome the initial universe or market for Curry in a Hurry. Assuming that the percentage ofthe population of Pittsburgh that totally abhors Indian food is negligible, the entrepreneur canstart the STP process.

Several relevant segmentation variables, such as demographics, residential neighbor-hoods, ethnic origin, marital status, income level, and patterns of eating out, could be used.On the basis of these, the entrepreneur could send out questionnaires to selected neighbor-hoods and organize focus groups at, say, the two major universities in Pittsburgh. Analyz-ing responses to the questionnaires and focus groups, she could arrive at a target segment—for example, wealthy families, both Indian and others, who eat out at least twice a week.That would help her determine her menu choices, decor, hours, and other operational de-tails. She could then design marketing and sales campaigns to induce her target segment totry her restaurant. She could also visit other Indian and fast food restaurants and find somemethod of surveying them and then develop plausible demand forecasts for her plannedrestaurant.

In any case, the process would involve considerable amounts of time and analytical effort.It would also require resources both for research and, thereafter, for implementing the market-ing strategies. In summary, the current paradigm suggests that we proceed inward to specificsfrom a larger, general universe—that is, to an optimal target segment from a predeterminedmarket. In terms of Curry in a Hurry, this could mean something like a progression from theentire city of Pittsburgh to Fox Chapel (an affluent residential neighborhood) to the Joneses(specific customer profile of a wealthy family), as it were.

Instead, if our imaginary entrepreneur were to use processes of effectuation to build herrestaurant, she would have to proceed in the opposite direction (note that effectuation issuggested here as a viable and descriptively valid alternative to the STP process—not as a

CHAPTER 1 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE ENTREPRENEURIAL MIND-SET 11

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 11

normatively superior one). For example, instead of starting with the assumption of an existingmarket and investing money and other resources to design the best possible restaurant for thegiven market, she would begin by examining the particular set of means or causes available toher. Assuming she has extremely limited monetary resources—say $20,000—she should thinkcreatively to bring the idea to market with as close to zero resources as possible. She could dothis by convincing an established restaurateur to become a strategic partner or by doing justenough market research to convince a financier to invest the money needed to start the restau-rant. Another method of effectuation would be to convince a local Indian restaurant or a localfast food restaurant to allow her to put up a counter where she would actually sell a selectionof Indian fast food. Selecting a menu and honing other such details would be seat-of-the-pantsand tentative, perhaps a process of satisficing.10

Several other courses of effectuation can be imagined. Perhaps the course the entrepreneuractually pursues is to contact one or two of her friends or relatives who work downtown andbring them and their office colleagues some of her food to taste. If the people in the office likeher food, she might get a lunch delivery service going. Over time, she might develop enoughof a customer base to start a restaurant or else, after a few weeks of trying to build the lunchbusiness, she might discover that the people who said they enjoyed her food did not reallyenjoy it so much as they did her quirky personality and conversation, particularly her rather un-usual life perceptions. Our imaginary entrepreneur might now decide to give up the lunch busi-ness and start writing a book, going on the lecture circuit and eventually building a business inthe motivational consulting industry!

Given the exact same starting point—but with a different set of contingencies—the entrepre-neur might end up building one of a variety of businesses. To take a quick tour of some possi-bilities, consider the following: Whoever first buys the food from our imaginary Curry in aHurry entrepreneur becomes, by definition, the first target customer. By continually listeningto the customer and building an ever-increasing network of customers and strategic partners,the entrepreneur can then identify a workable segment profile. For example, if the first cus-tomers who actually buy the food and come back for more are working women of varied eth-nic origin, this becomes her target segment. Depending on what the first customer really wants,she can start defining her market. If the customer is really interested in the food, the entrepre-neur can start targeting all working women in the geographic location, or she can think interms of locating more outlets in areas with working women of similar profiles—a “Women ina Hurry” franchise?

Or, if the customer is interested primarily in the idea of ethnic or exotic entertainment,rather than merely in food, the entrepreneur might develop other products, such as cateringservices, party planning, and so on—“Curry Favors”? Perhaps, if the customers buy food fromher because they actually enjoy learning about new cultures, she might offer lectures andclasses, maybe beginning with Indian cooking and moving on to cultural aspects, includingconcerts and ancient history and philosophy, and the profound idea that food is a vehicle ofcultural exploration—“School of Curry”? Or maybe what really interests them is theme toursand other travel options to India and the Far East—“Curryland Travels”?

In a nutshell, in using effectuation processes to build her firm, the entrepreneur can buildseveral different types of firms in completely disparate industries. This means that the originalidea (or set of causes) does not imply any one single strategic universe for the firm (or effect).Instead, the process of effectuation allows the entrepreneur to create one or more several pos-sible effects irrespective of the generalized end goal with which she started. The process notonly enables the realization of several possible effects (although generally one or only a feware actually realized in the implementation) but it also allows a decision maker to change hisor her goals and even to shape and construct them over time, making use of contingencies asthey arise.11

Our use of direct quotes from Sarasvathy on effectuation is not to make the case that itis superior to thought processes that involve causation; rather, it represents a way that en-trepreneurs sometimes think. Effectuation helps entrepreneurs think in an environment of

12 PART 1 THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 12

high uncertainty. Indeed organizations today operate in complex and dynamic environ-ments that are increasingly characterized by rapid, substantial, and discontinuous change.12

Given the nature of this type of environment, most managers of firms need to take on anentrepreneurial mind-set so that their firms can successfully adapt to environmentalchanges.13 This entrepreneurial mind-set involves the ability to rapidly sense, act, andmobilize, even under uncertain conditions.14 In developing an entrepreneurial mind-set,individuals must attempt to make sense of opportunities in the context of changing goals,constantly questioning one’s “dominant logic” in the context of a changing environment,and revisiting “deceptively simple questions” about what we think to be true about marketsand the firm. For example, effective entrepreneurs are thought to continuously “rethinkcurrent strategic actions, organization structure, communications systems, corporateculture, asset deployment, investment strategies, in short every aspect of a firm’s operationand long-term health.”15

To be good at these tasks individuals must develop a cognitive adaptability. MikeHaynie, a retired major of the U.S. Air Force and now professor at Syracuse University, hasdeveloped a number of models of cognitive adaptability and a survey for capturing it, towhich we now turn.16

Cognitive Adaptability

Cognitive adaptability describes the extent to which entrepreneurs are dynamic, flexible,self-regulating, and engaged in the process of generating multiple decision frameworksfocused on sensing and processing changes in their environments and then acting onthem. Decision frameworks are organized prior knowledge about people and situationsthat are used to help someone make sense of what is going on.17 Cognitive adaptabilityis reflected in an entrepreneur’s metacognitive awareness, that is, the ability to reflectupon, understand, and control one’s thinking and learning.18 Specifically, metacognitiondescribes a higher-order cognitive process that serves to organize what individuals knowand recognize about themselves, tasks, situations, and their environments to promote ef-fective and adaptable cognitive functioning in the face of feedback from complex anddynamic environments.19

How cognitively adaptable are you? Try the survey in Table 1.2 and compare yourself tosome of your classmates. A higher score means that you are more metacognitively awareand this in turn helps provide cognitive adaptability. Regardless of your score, the goodnews is that you can learn to be more cognitively adaptable. This ability will serve you wellin most new tasks, but particularly when pursuing a new entry and managing a firm in anuncertain environment. Put simply, it requires us to “think about thinking which requires,and helps provide, knowledge and control over our thinking and learning activities—itrequires us to be self-aware, to think aloud, to reflect, to be strategic, to plan, to have aplan in mind, to know what to know, to self-monitor.20 We can achieve this by asking our-selves a series of questions that relate to (1) comprehension, (2) connection, (3) strategy,and (4) reflection.21

1. Comprehension questions are designed to increase entrepreneurs’ understanding of thenature of the environment before they begin to address an entrepreneurial challenge,whether it be a change in the environment or the assessment of a potential opportunity.Understanding arises from recognition that a problem or opportunity exists, the natureof that situation, and its implications. In general, the questions that stimulate individu-als to think about comprehension include: What is the problem all about? What is thequestion? What are the meanings of the key concepts? Specific to entrepreneurs, the

CHAPTER 1 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE ENTREPRENEURIAL MIND-SET 13

entrepreneurial mind-setInvolves the ability torapidly sense, act, andmobilize, even underuncertain conditions

cognitive adaptabilityDescribes the extent towhich entrepreneurs aredynamic, flexible, self-regulating, and engagedin the process ofgenerating multipledecision frameworksfocused on sensing andprocessing changes intheir environments andthen acting on them

comprehension questionsQuestions designed toincrease entrepreneurs’understanding of thenature of the environment

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 13

14

AS SEEN IN ENTREPRENEUR MAGAZINE

WHAT ME WORRY? HOW SMART ENTREPRENEURS HARNESS THE POWEROF PARANOIA

Depending on who you’re talking to, paranoia is:(1) a psychotic disorder characterized by delusions ofpersecution, (2) an irrational distrust of others, or(3) a key trait in entrepreneurial success.

Sound crazy? Not according to Andrew S. Grove,president and CEO of Intel Corp. in Santa Clara,California, and author of Only the Paranoid Survive(Doubleday/Currency). The title of Grove’s bookcomes from an oft-repeated quote that has becomethe mantra of the chip king’s rise to the top of thetechnology business.

“I have no idea when I first said this,” Grovewrites, “but the fact remains that, when it comes tobusiness, I believe in the value of paranoia.” To thosewho suffer from clinical delusions of persecution, ofcourse, paranoia is neither a joke nor a help. How-ever, in a business context, the practice of voluntarilybeing highly concerned about potential threats toyour company has something of a following.

“If you’re not a little bit paranoid, you’re compla-cent,” says Dave Lakhani, an entrepreneur in Boise,Idaho, who offers marketing consulting to small busi-nesses. “And complacency is what leads people intomissed opportunities and business failure.”

PICK YOUR PARANOIABeing paranoid, according to Grove, is a matter of re-membering that others want the success you have,paying attention to the details of your business, andwatching for the trouble that inevitably awaits. Thatbasically means he is paranoid about everything. “Iworry about products getting screwed up, and I worryabout products getting introduced prematurely,”Grove writes. “I worry about factories not performingwell, and I worry about having too many factories.”

For Grove, as for most advocates of paranoia, be-ing paranoid primarily consists of two things. Thefirst is not resting on your laurels. Grove calls it a“guardian attitude” that he attempts to nurture inhimself and in Intel’s employees to fend off threatsfrom outside the company. Paranoia in business isalso typically defined as paying very close attentionto the fine points. “You need to be detail-orientedabout the most important things in your business,”says Lakhani. “That means not only making sureyou’re working in your business but that you’re thereevery day, paying attention to your customers.”

As an example of paranoia’s value in practice,Lakhani recalls when sales began slowly slumpingat a retail store he once owned. He could have dis-missed it as a mere blip. Instead, he worried andwatched until he spotted a concrete cause. “Itturned out one of my employees had developed anegative attitude, and it was affecting my business,”Lakhani says. “As soon as I let him go, sales wentback up.”

The main focuses of most entrepreneurs’ paranoia,however, are not so much everyday internal details asmajor competitive threats and missed opportunities.Situations in which competition and opportunity areboth at high levels are called “strategic inflectionpoints” by Grove, and it is during these times, typi-cally when technology is changing, that his paranoiais sharpest.

Paranoia is frequently a welcome presence at ma-jor client presentations for Katharine Paine, founderand CEO of The Delahaye Group Inc. In the past,twinges of seemingly unfounded worry have causedPaine to personally attend sales pitches where shelearned of serious problems with the way her firm wasdoing business, she says. The head of the 50-personPortsmouth, New Hampshire, marketing evaluationresearch firm traces her paranoid style to childhooddays spent pretending to be an Indian trackingquarry through the forest. When she makes mentalchecklists about things that could go wrong or op-portunities that could be missed, she’s always keep-ing an eye out for the business equivalent of a benttwig. “If you are paranoid enough, if you’re goodenough at picking up all those clues, you don’t haveto just react,” says Paine, “you get to proact and beslightly ahead of the curve.”

PARANOID PARAMETERSThere is, of course, such a thing as being too para-noid. “There are times when it doesn’t make anysense,” acknowledges Lakhani. Focusing on details tothe point of spending $500 in accounting fees to finda $5 error is one example of misplaced paranoia.Worrying obsessively about what every competitor isdoing or what every potential customer is thinking isalso a warning sign, he says. Lack of balance with in-terests outside the business may be another. “If yourwhole life is focused around your work, and that’s

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 14

15

the only thing you’re thinking about 24 hours a day,that becomes detrimental,” Lakhani says.

For Paine, failing to act is a sign that you’re goingpast beneficial paranoia and into hurtful fear. “Fearfor most of us results in inaction—absolute death foran entrepreneur,” she says. “If we feared the loss of apaycheck or feared entering a new market, none ofour businesses would have gotten off the ground.”

All this may be especially true for small-businessowners. While paranoia may be appropriate forheads of far-flung enterprises, some say entrepre-neurs are already too paranoid. It’s all too easy forentrepreneurs to take their desire for independenceand self-determination and turn it into trouble, saysRobert Barbato, director of the Small Business Insti-tute at the Rochester Institute of Technology inRochester, New York. Typically, entrepreneurs takethe attitude that “nobody cares as much about thisbusiness as I do” and exaggerate it to the point ofhurtful paranoia toward employees and even cus-tomers, he says. “They’re seeing ghosts where ghostsdon’t exist,” warns Barbato.

That’s especially risky when it comes to dealing withemployees. Most people—not just entrepreneurs—do their work for the sense of accomplishment,not because they are plotting to steal their em-ployer’s success, Barbato says. He acknowledges thismay be a difficult concept for competition-crazedentrepreneurs—especially those who have neverthemselves been employees—to understand. “Peoplewho own their own business are not necessarily usedto moving up the ranks,” Barbato notes. Entrepre-neurs must learn to trust and delegate if their busi-nesses are to grow.

PRACTICAL PARANOIANo matter how useful it is, paranoia may be tooloaded a label for some entrepreneurs. If so, criticalevaluation or critical analysis are the preferred terms ofStephen Markowitz, director of governmental and

political relations of the Small Business Association ofDelaware Valley, a 5,000-member trade group. The dis-tinction is more than name-deep. “When I say ‘criticallyevaluate,’ that means look at everything,” Markowitzexplains. “If you’re totally paranoid, the danger is notbeing able to critically evaluate everything.”

For example, Markowitz says a small retailerthreatened by the impending arrival of a superstorein the market would be better served by criticallyevaluating the potential for benefit as well as harm,instead of merely worrying about it. “If you’re para-noid,” he says, “you’re not going to critically evaluatehow it might help you.”

Whatever name it goes by, few entrepreneursare likely to stop worrying anytime soon. In fact,experience tends to make them more confirmed intheir paranoia as they go along. Paine recalls thetime a formless fear led her to insist on going to aclient meeting where no trouble was expected. Shelost the account anyway. “The good news is, myparanoia kicked in,” she says. “The bad news is, itwas too late. That made me much more paranoid inthe future.”

ADVICE TO AN ENTREPRENEURA friend who has just become an entrepreneur hasread the above article and comes to you for advice:

1. I worry about my business, does that mean that Iam paranoid?

2. What are the benefits of paranoia and what arethe costs?

3. How do I know I have the right level of paranoiato effectively run the business and not put me inthe hospital with a stomach ulcer?

4. Won’t forcing myself to be more paranoid takethe fun out of being an entrepreneur?

Source: Reprinted with permission of Entrepreneur Media, Inc.,“How Smart Entrepreneurs Harness the Power of Paranoia,” byMark Henricks, March, 1997, Entrepreneur magazine: www.entrepreneur.com.

questions are more likely to include: What is this market all about? What is this tech-nology all about? What do we want to achieve by creating this new firm? What are thekey elements to effectively pursuing this opportunity?

2. Connection tasks are designed to stimulate entrepreneurs to think about the currentsituation in terms of similarities and differences with situations previously faced andsolved. In other words, these tasks prompt the entrepreneur to tap into his or herknowledge and experience without overgeneralizing. Generally, connection tasksfocus on questions like: How is this problem similar to problems I have already

connection tasks Tasksdesigned to stimulateentrepreneurs to thinkabout the current situationin terms of similaritiesand differences withsituations previouslyfaced and solved

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 9:17 PM Page 15

16 PART 1 THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE

How Cognitively Flexible Are You? On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is “not very much like me,”and 10 is “very much like me,” how do you rate yourself on the following statements?

Goal Orientation

I often define goals for myself. Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Verymuch like me

I understand how accomplishment Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very of a task relates to my goals. much like me

I set specific goals before Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very I begin a task. much like me

I ask myself how well I’ve Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very accomplished my goals once much like meI’ve finished.

When performing a task, I Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Veryfrequently assess my progress much like meagainst my objectives.

Metacognitive Knowledge

I think of several ways to solve a Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very problem and choose the best one. much like me

I challenge my own assumptions Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very about a task before I begin. much like me

I think about how others may react Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very to my actions. much like me

I find myself automatically Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very employing strategies that have much like meworked in the past.

I perform best when I already Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very have knowledge of the task. much like me

I create my own examples to make Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very information more meaningful. much like me

I try to use strategies that have Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very worked in the past. much like me

I ask myself questions about the Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very task before I begin. much like me

I try to translate new information Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very into my own words. much like me

I try to break problems down into Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very smaller components. much like me

I focus on the meaning and Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very significance of new information. much like me

Metacognitive Experience

I think about what I really need Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very to accomplish before I begin a task. much like me

I use different strategies depending Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very on the situation. much like me

I organize my time to best Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very accomplish my goals. much like me

TABLE 1.2 Mike Haynie’s “Measure of Adaptive Cognition”

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 16

CHAPTER 1 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE ENTREPRENEURIAL MIND-SET 17

I am good at organizing Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Veryinformation. much like me

I know what kind of information is Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very most important to consider when much like mefaced with a problem.

I consciously focus my attention on Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very important information. much like me

My ”gut” tells me when a given Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very strategy I use will be most effective. much like me

I depend on my intuition to help Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very me formulate strategies. much like me

Metacognitive Choice

I ask myself if I have considered all Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very the options when solving a problem. much like me

I ask myself if there was an easier Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very way to do things after I finish a task. much like me

I ask myself if I have considered all Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very the options after I solve a problem. much like me

I re-evaluate my assumptions when Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very I get confused. much like me

I ask myself if I have learned as Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very much as I could have after I finish much like methe task.

Monitoring

I periodically review to help me Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very understand important relationships. much like me

I stop and go back over information Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very that is not clear. much like me

I am aware of what strategies I use Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very when engaged in a given task. much like me

I find myself analyzing the Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very usefulness of a given strategy while much like meengaged in a given task.

I find myself pausing regularly to Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very check my comprehension of the much like meproblem or situation at hand.

I ask myself questions about how Not very much like me—1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10—Very well I am doing while I am much like meperforming a novel task. I stop and re-read when I get confused.

Result—A higher score means that you are more aware of the way that you think about how you make decisions and are there-fore more likely to be cognitively flexible.

Source: M. Haynie and D. Shepherd (2009) “A Measure of Adaptive Cognition for Entrepreneurship Research.” Entrepreneur-ship, Theory and Practice vol. 33(3): pp. 695–714.

solved? Why? How is this problem different from what I have already solved? Why?Specific to entrepreneurs, the questions are more likely to include: How is this newenvironment similar to others in which I have operated? How is it different? How isthis new organization similar to the established organizations I have managed? Howis it different?

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 17

3. Strategic tasks are designed to stimulate entrepreneurs to think about whichstrategies are appropriate for solving the problem (and why) or pursuing the op-portunity (and how). These tasks prompt them to think about the what, why, andhow of their approach to the situation. Generally, these questions include: Whatstrategy/tactic/principle can I use to solve this problem? Why is this strategy/tactic/principle the most appropriate one? How can I organize the information tosolve the problem? How can I implement the plan? Specific to entrepreneurs, thequestions are likely to include: What changes to strategic position, organizationalstructure, and culture will help us manage our newness? How can the implemen-tation of this strategy be made feasible?

4. Reflection tasks are designed to stimulate entrepreneurs to think about their under-standing and feelings as they progress through the entrepreneurial process. These tasksprompt entrepreneurs to generate their own feedback (create a feedback loop in theirsolution process) to provide the opportunity to change. Generally, reflection questionsinclude: What am I doing? Does it make sense? What difficulties am I facing? How doI feel? How can I verify the solution? Can I use another approach for solving the task?Specific to the entrepreneurial context, entrepreneurs might ask: What difficulties willwe have in convincing our stakeholders? Is there a better way to implement our strat-egy? How will we know success if we see it?

Entrepreneurs who are able to increase cognitive adaptability have an improved abilityto (1) adapt to new situations—i.e., it provides a basis by which a person’s prior experienceand knowledge affect learning or problem solving in a new situation; (2) be creative—i.e.,it can lead to original and adaptive ideas, solutions, or insights; and (3) communicate one’sreasoning behind a particular response.22 We hope that this section of the book has not onlyprovided you a deeper understanding of how entrepreneurs can think and act with greatflexibility, but also an awareness of some techniques for incorporating cognitive adaptabil-ity in your life.

We have discussed how entrepreneurs make decisions in uncertain environments and howone might develop an ability to be more cognitively flexible. It is important to note thatentrepreneurs operate in such uncertain environments because that is where the oppor-tunities for new entry are to be found and/or generated. There is the possibility that op-portunities exist in more stable environments, but even in this situation the entrepreneur’snew entry may create industry instability and uncertainty. Given the inherent uncertaintyin entrepreneurial action, there is the possibility that an entrepreneur will experience fail-ure. Failure can be valuable if the entrepreneur is able to learn from it. We now investigatethe process of learning from business failure.

Learning from Business Failure23

Businesses fail. In 2008, a total of 6,513 U.S. firms filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy(Chapter 11 provides for a business to continue operations while formulating a plan to re-pay its creditors) and 23,372 U.S. firms filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy (Chapter 7 is de-signed to allow individuals to keep certain exempt property while the remaining propertyis sold to repay creditors) (www.uscourts.gov). Business failure occurs when a fall in rev-enue and/or a rise in expense is of such magnitude that the firm becomes insolvent and isunable to attract new debt or equity funding; consequently, it cannot continue to operateunder the current ownership and management. Projects also fail, such as failure of a newproduct development effort, the entry into a new market, or an alliance with a former

18 PART 1 THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE

reflection tasks Tasksdesigned to stimulateentrepreneurs to thinkabout their understandingand feelings as theyprogress through theentrepreneurial process

strategic tasks Tasksdesigned to stimulateentrepreneurs to thinkabout which strategies areappropriate for solvingthe problem (and why) orpursuing the opportunity(and how)

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 18

competitor. Failure is particularly common among entrepreneurial firms because thenewness that is the source of an opportunity is also a source of uncertainty and changingconditions.

Although there are many causes of failure, the most common is insufficient experi-ence. That is, entrepreneurs who have more experience will possess the knowledge toperform more effectively the roles and tasks necessary for success. This experience neednot come solely from success. In fact, it appears that we may learn more from our fail-ures than our successes.24

A leading entrepreneurship scholar, Rita McGrath, has argued that because entrepre-neurs typically seek success and try to avoid failure for their projects, errors are intro-duced that can not only inhibit the learning and interpretation processes but also makeproject failure more likely or expensive than necessary. She proposes that there are ben-efits to be gained from the pursuit of risky opportunities, even if that pursuit increasesthe potential for failure. This entrepreneurial process of experimentation generatesimprovements in technologies.25 Although Professor McGrath focuses on the failureof projects within a firm, it appears that the process of learning from failure alsobenefits society through the application of that knowledge to subsequent businesses.Other businesses can learn from an entrepreneur’s mistake and that learning can helpour economy.

Does failure always lead to learning? Perhaps, but it would seem that the issue is morecomplex. The motivation for managing one’s own business or the creation of a new projectat work is typically not simply one of personal profit but also loyalty to a product, loyaltyto a market and customers, personal growth, and the need to prove oneself.26 Some entre-preneurs use their ventures to “create a product that flows from their own internal desiresand needs. They create primarily to express subjective conceptions of beauty, emotion, orsome aesthetic ideal.”27 For members of a family business, the firm may not only be asource of income but also a context for family activity and the embodiment of family prideand identity. This suggests that the loss of a business is likely to generate a negative emo-tional response from the entrepreneur.28

One entrepreneur that I know exhibited a number of worrying emotions when his fam-ily business failed. There was numbness and disbelief that this business he had created20-odd years ago was no longer alive. There was some anger toward the economy, competi-tors, and debtors. A stronger emotion than anger was that of guilt and self-blame. He feltguilty that he had caused the failure of the business, that it could no longer be passed on tohis children, and that as a result he had failed not only as a businessperson but also as afather. These feelings caused him distress and anxiety. He felt the situation was hopeless,became withdrawn, and at times depressed. These are all strong negative emotions. Afterthe failure of their businesses or projects, it is likely that most entrepreneurs feel a negativeemotional response to that loss.

This negative emotional reaction can interfere with entrepreneurs’ ability to learn fromthe failure and quite possibly their motivation to try again. For entrepreneurs, learning fromfailure occurs when they can use the information available about why the venture failed(feedback information) to revise their existing knowledge of how to manage their venturesmore effectively (entrepreneurial knowledge)—that is, revise assumptions about the conse-quences of previous assessments, decisions, actions, and inactions. For example, RaviKalakota has learned a number of lessons from the loss of his business, Hsupply.com, suchas, “Don’t let venture capitalists hijack your vision,” “Don’t rapidly burn through capital toachieve short-term growth,” and “Don’t underestimate the speed others will imitate yourproducts and services.”29

CHAPTER 1 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE ENTREPRENEURIAL MIND-SET 19

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 19

Indeed, negative emotion(s) have been found to interfere with individuals’ allocation ofattention in the processing of information. Such interference negatively impacts their abil-ity to learn from negative events.30 For the entrepreneur, this could mean focusing atten-tion on the day that the business closed (i.e., dwelling on announcements to employees,buyers, and suppliers, as well as handing over the office keys to a liquidator), rather thanallocating sufficient attention on feedback information, such as previous actions and/orinactions that caused the deterioration in business performance and ultimately the loss ofthe business.

Recovery and Learning Process

An individual has emotionally recovered from the failure when thoughts about the eventssurrounding, and leading up to, the loss of the business no longer generate a negative emo-tional response. The two primary descriptions of the process of recovering from feelingsarising from failure are classifiable as either loss-oriented or restoration-oriented.

Loss-orientation refers to working through, and processing, some aspect of the lossexperience and, as a result of this process, breaking emotional bonds to the object lost.This process of constructing a series of accounts about the loss gradually provides theloss with meaning and eventually produces a changed viewpoint of the self and theworld. Changing the way that an event is interpreted can allow an entrepreneur to regu-late emotions so that thoughts of the event no longer generate negative emotions.Entrepreneurs with a loss-orientation might seek out friends, family, or psychologists totalk about their negative feelings. But they may also focus their thoughts on the timespent in creating and nurturing the business and may ruminate about the circumstancesand events surrounding the loss. It appears that such thoughts could evoke a sense ofyearning for the way things used to be or foster a sense of relief that the events sur-rounding the loss (e.g., arguing with creditors, explaining to employees, family, andfriends the business has failed) are finally over. While these feelings of relief and painwax and wane over time, in the early periods after the failure, painful memories arelikely to dominate.31

Restoration-orientation is based on both avoidance and a proactiveness toward second-ary sources of stress arising from failure. For avoidance, it is possible that entrepreneurscan distract themselves from thinking about the loss of the business or project to speed re-covery. For the entrepreneur, founding a new venture might enhance recovery from the neg-ative emotions over the loss of the previous business (although there is the possibility thatthe same mistakes will be replicated because these entrepreneurs have not sufficientlylearned from their experience).

A restoration-orientation is not simply about avoidance, however; it also involves theway that an entrepreneur attends to other aspects of his or her life (e.g., coping with dailylife, learning new tasks). It refers to being proactive toward secondary sources of stressinstead of being concerned with the loss itself. Such activities enable entrepreneurs to dis-tract themselves from thinking about the loss while simultaneously maintaining essentialactivities necessary for restructuring aspects of their lives. This may apply to the entre-preneur, for whom the loss of the business itself generates a negative emotional responsewhile causing the loss of income, social status, and positive perceptions of self. Forexample, an entrepreneur must reorganize his life to cope without the business. It mightbe necessary to apply for jobs, join the unemployment line, and/or sell the house andmove to a less expensive neighborhood (requiring the children to change schools). Theremight also be other stressors, such as responding to questions such as: “What do you dofor a living?” or “How is your business going?” In addressing these secondary sources of

20 PART 1 THE ENTREPRENEURIAL PERSPECTIVE

loss-orientation Anapproach to griefrecovery that involvesworking through, andprocessing, some aspectof the loss experienceand, as a result of thisprocess, breakingemotional bonds to theobject lost

restoration-orientationAn approach to griefrecovery based on bothavoidance and aproactiveness towardsecondary sources ofstress arising from amajor loss

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 20

stress, the entrepreneur is able to eventually reduce the negative emotions associated withthoughts of the events surrounding the loss of the business.

A Dual Process for Learning from Failure

Which process of recovery is most effective in promoting learning from the experience? It isnot an “either/or” choice between the two orientations. Both loss-oriented and restoration-oriented coping styles are likely to have different costs. A loss-orientation involves confronta-tion, which is physically and mentally exhausting, whereas a restoration-orientation involvessuppression, which requires mental effort and presents potentially adverse consequences forhealth. Oscillation between the two orientations enables an entrepreneur to obtain the bene-fits of each and to minimize the costs of maintaining one for too long—this dual processspeeds the recovery process.32 Speeding the recovery process is important because it morequickly reduces the emotional interference with learning.

For example, starting with a loss-orientation provides an individual the ability to firstfocus on aspects of the loss experience and begin processing information about the busi-ness loss as well as breaking the emotional bonds to the failed business or project. Whenthe entrepreneur’s attention begins to shift from the event to aspects of the emotions it-self, then learning is likely reduced by emotional interference and the entrepreneurshould switch to a restoration-orientation. Switching to a restoration-orientation en-courages individuals to think about other aspects of their life. It also breaks the cycle ofcontinually thinking about the symptoms arising from the failure; such thoughts can in-crease negative feelings.33 This restoration-orientation also provides the opportunity toaddress secondary causes of stress, which may reduce the emotional significance of thefailure. When information processing capacity is no longer focused on the symptoms,the entrepreneur can shift back to a loss-orientation and use his or her information pro-cessing capacity to generate further meaning from the loss experience and also furtherreduce the emotional significance of the loss of the business. Oscillation should con-tinue until the entrepreneur has emotionally recovered and been able to fully learn fromthe experience.

The dual process of learning from failure has a number of practical implications. First,knowledge that the feelings and reactions being experienced by the entrepreneur are nor-mal for someone dealing with such a loss may help to reduce feelings of shame and em-barrassment. This in turn might encourage the entrepreneur to articulate her feelings, pos-sibly speeding the recovery process. Second, there are psychological and physiologicaloutcomes caused by the feelings of loss. Realizing that these are “symptoms” can reducesecondary sources of stress and may also assist with the choice of treatment. Third, there isa process of recovery to learn from failure, which offers entrepreneurs some comfort thattheir current feelings of loss, sadness, and helplessness will eventually diminish. Fourth,the recovery and learning process can be enhanced by some degree of oscillation betweena loss- and a restoration-orientation. Finally, recovery from loss offers an opportunity toincrease one’s knowledge of entrepreneurship. This provides benefits to the individual andto society.

ETHICS AND SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY OF ENTREPRENEURS

The life of the entrepreneur is not easy. An entrepreneur must take risks with his or her owncapital to sell and deliver products and services while expending greater energy than theaverage businessperson to innovate. In the face of daily stressful situations and other diffi-culties, the possibility exists that the entrepreneur will establish a balance between ethical

CHAPTER 1 ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE ENTREPRENEURIAL MIND-SET 21

dual process for griefInvolves oscillationbetween the two griefrecovery approaches(loss-orientation andrestoration-orientation)

his30328_ch01_001-033.qxd 7/29/09 8:56 PM Page 21

exigencies, economic expediency, and social responsibility, a balance that differs from thepoint where the general business manager takes his or her moral stance.34

A manager’s attitudes concerning corporate responsibility are related to the organiza-tional climate perceived to be supportive of laws and professional codes of ethics. On theother hand, entrepreneurs with a relatively new company who have few role models usuallydevelop an internal ethical code. Entrepreneurs tend to depend on their own personal valuesystems much more than other managers when determining ethically appropriate coursesof action.

Although drawing more on their own value system, entrepreneurs have been shownto be particularly sensitive to peer pressure and general social norms in the community,as well as pressures from their competitors. The differences between entrepreneurs indifferent types of communities and in different countries reflect, to some extent, thegeneral norms and values of the communities and countries involved. This is clearly thecase for metropolitan as opposed to nonmetropolitan locations within a single country.Internationally, there is evidence to this effect about managers in general. U.S. man-agers seem to have more individualistic and less communitarian values than theirGerman and Austrian counterparts.

The significant increase in the number of internationally oriented businesses has im-pacted the increased interest in the similarities and differences in business attitudes andpractices in different countries. This area has been explored to some extent within the con-text of culture and is now beginning to be explored within the more individualized conceptof ethics. The concepts of culture and ethics are somewhat related. Whereas ethics refers tothe “study of whatever is right and good for humans,” business ethics concerns itself withthe investigation of business practices in light of human values. Ethics is the broad field ofstudy exploring the general nature of morals and the specific moral choices to be made bythe individual in his or her relationship with others.

A central question in business ethics is, “For whose benefit and at whose expense shouldthe firm be managed?”35 In addressing this question we focus on the means of ensuring thatresources are deployed fairly between the firm and its stakeholders—the people who havea vested interest in the firm, including employees, customers, suppliers, and society itself.If resource deployment is not fair, then the firm is exploiting a stakeholder.

Entrepreneurship can play a role in the fair deployment of resources to alleviate theexploitation of certain stakeholders. Most of us can think of examples of firms that havebenefited financially because their managers have exploited certain stakeholders-receivingmore value from them than they supply in return. This exploitation of a stakeholdergroup can represent an opportunity for an entrepreneur to more fairly and efficiently re-deploy the resources of the exploited stakeholder. Simply stated, where current pricesdo not reflect the value of a stakeholder’s resources, an entrepreneur who discovers thediscrepancy can enter the market to capture profit. In this way the entrepreneurialprocess acts as a mechanism to ensure a fair and efficient system for redeploying theresources of a “victimized” stakeholder to a use where value supplied and received isequilibrated.36