The Dark Side of Cross-Selling

-

Upload

aditya-mishra -

Category

Documents

-

view

95 -

download

5

Transcript of The Dark Side of Cross-Selling

New Thinking, Research in Progress hbr.org

CULTURE 26The role of trust in global negotiations

DEFEND YOUR RESEARCH 28Wall Street doesn’t favor fi rms that are good at innovating

VISION STATEMENT 30How vital are the world’s great urban centers?

COLUMN 36Ronald Coase on saving economics from the economists

Imagine you’re a marketing manager for a national catalog retailer—a company that sells a wide array of wares, includ-

ing apparel, furniture, bed and bath prod-ucts, and outdoor items. Every category has its own catalog. You have before you data on two customers. Each currently buys products from just one of your cata-logs, and each is modestly unprofitable. According to your data models, if you start sending those customers catalogs for your other product lines, they’ll probably start cross-buying. You could entice them with e-mailed discounts and coupons as well.

At an intuitive level, this makes sense: Once you’ve done the hard work of acquir-ing a customer, why wouldn’t you try to sell her more products? That’s what a U.S. retailer we studied (the model for the sce-nario above) did. But although one of the customers ultimately became profitable, generating $297 over the next few years, the other cost the company $315 during the same period.

Most managers cross-sell to every cus-tomer, sure that more sales means more profits. And cross-selling is profitable in the aggregate. But our analysis , to our knowledge the � rst of its kind, found that � rms that indiscriminately encourage all their customers to buy more are making a costly mistake: A significant subset of cross- buyers are highly unpro� table.

We interviewed dozens of managers from 36 � rms across industries in the U.S. and Europe. More than 90% of the firms had run cross-selling campaigns, and all found that their e� orts increased average per-customer profit. Every manager said IL

LUST

RATI

ON

: AN

DREW

BAN

NEC

KER

The Dark Side Of Cross-SellingCompanies work hard to persuade existing customers to buy additional products. Often that’s a money-losing proposition. by Denish Shah and V. Kumar

MARKETING

December 2012 Harvard Business Review 21

Know your problem customers

that because of this lift, he would cross-sell to any customer.

But there’s a deep flaw in the managers’ logic. To tease out the impact on profits of individuals’ cross-buying, we analyzed the customer data sets of five Fortune 1,000 companies—a B2B financial services firm, a B2B IT services firm, a retail bank, a cata-log retailer, and a fashion retailer—over periods ranging from four to seven years. Although we confirmed that the average profit from customers who cross-buy is higher than that from customers who don’t, we discovered that one in five cross-buying customers is unprofitable. That group ac-counts for 70% of a firm’s total “customer loss”—the shortfall when the cost of goods and of marketing to a given customer ex-ceeds the revenue realized. And the more cross-buying an unprofitable customer does, the greater the loss.

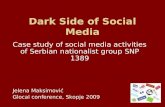

Bad ApplesWho are these profit-destroying custom-ers? Our study revealed four distinct pro-files. Identifying customers who fit these profiles is the first step toward neutralizing their impact.

Service demanders. These people habitually overuse customer service in all channels, from phone to web to face-to-face interactions. The more they cross-buy, the more service demands they make—and the more your costs rise. At the retail bank we studied, requests from service demand-ers for things such as assistance with on-line banking and balance transfers more than doubled after the customers began cross-buying.

Revenue reversers. Customers in this segment generate revenue but then take it back. At firms selling products, this typi-

cally happens through returns. In many cases, the more a revenue reverser buys, the more he returns. At firms selling ser-vices, revenue reversals generally involve defaults on or early termination of loans or contracts. At the retail bank—where revenue reversers cost about $5 million a year—about half of the customers in this group had defaulted more than once.

Promotion maximizers. These cus-tomers gravitate toward steep discounts and avoid regularly priced items. At the catalog retailer and the fashion retailer we studied, the average annual loss from each promotion maximizer was $300.

Spending limiters. Customers in this segment spend only a small, fixed amount with a given company, either because of fi-nancial constraints or because they spread their purchases among several companies. If they cross-buy, they don’t increase their total spending with the company; they re-allocate it among a greater assortment of products or services. This generates cross-selling costs without increasing revenue. At the financial services firm we studied, a number of business customers who kept about $5,000 in their checking accounts responded to cross-selling promotions for products such as insurance or CDs simply by drawing down their checking accounts to buy the products. The increase in reve-nue from the more-profitable products was not enough to cover the cross-selling costs.

Cross-selling to any of these problem customers is likely to trigger a downward spiral of decreasing profits or accumulating losses, for two reasons: First, cross-selling generates marketing expenses; second, cross-buying amplifies costs by extending undesirable behavior to a greater number of products or services. This happens even among customers who were profitable be-fore they began cross-buying.

Halting the SpiralThe size of each problem segment varies from firm to firm. (See the exhibit “Know Your Problem Customers.”) Our research indicates that it depends in part on how companies implement common marketing practices—and suggests four ways to help prevent losses and maximize profits from cross-selling initiatives.

Examine your incentives. Having a substantial segment of problem customers may be a sign of flaws in the incentives—in-ternal or external—created by your market-ing strategy. For example, sales reps at the financial services firm were rewarded for increasing the number of products each customer bought, rather than for increas-ing revenue. As a result, they aggressively cross-sold. Our examination of the cus-tomer data set showed that the propor-tion of customers who merely reallocated their fixed spending with the firm across a greater number of products and services

Cross-selling is profitable in the aggregate. But one in five cross-buying customers is unprofitable—and together this group accounts for 70% of a company’s “customer loss.”

Our study of five Fortune 1,000 firms re-vealed four distinct types of unprofitable customers; the more they cross-buy, the greater the loss. The proportion of each group varied with the kind of firm.

Service demanders Revenue reversers Promotion maximizers Spending limiters

67%

29%

9

58

27

6

B2B finAnciAl ServiceS firm

B2B iT ServiceS firm

4%

ideA WATcH

22 Harvard Business Review december 2012

Know your problem customers

increased. We found a similar effect at the fashion retailer.

The IT services firm we studied, mean-while, invested heavily in customer service, thus inadvertently encouraging overuse by service demanders. And the catalog retailer offered a liberal return policy that made it easier for revenue reversers to abuse the system.

Companies shouldn’t have a blanket prohibition against cross-selling market-ing tactics, some of which, after all, are best practices. Instead, they should determine whether specific practices encourage prob-lem customers and adjust their approach accordingly.

For example, the electronics retailer Best Buy discovered that among the cus-tomers who had high rates of product re-turns were a subset who brought items back without the packaging and then vis-ited the store again and bought the same products at steeply discounted, open-box prices. Best Buy now requires customers who are returning items to present a photo ID, and reserves the right to refuse a return on the basis of a customer’s transaction history.

Don’t cross-sell—smart-sell. State-of-the-art cross-selling uses predictive models to determine which customers are likely to cross-buy which products. Basing marketing decisions solely on such models is ill-advised. Before undertaking cross-selling initiatives, firms need to analyze transaction data for each customer to de-termine whether she fits a problem profile.

If she does, the cross-sell decision should be turned into a no-sell or an upsell decision, depending on her characteristics and previous behavior. If a firm encounters a habitual revenue reverser, it might ex-

clude her from cross-selling campaigns. If it determines that a customer is a spending limiter, it might try to increase her spend-ing through upselling—for example, up-grading a banking customer from a regular to a premium checking account.

“Demarket” when necessary. Not all customer cross-buying occurs in response to cross-selling; some customers cross-buy on their own. When problem customers do, firms might be wise to “demarket” them—to limit or terminate the relationship.

Ending bad customer relationships isn’t uncommon; researchers have found that as many as 85% of executives in an array of firms and industries have done so (see “The Right Way to Manage Unprofitable Custom-ers,” HBR April 2008). When firms have contracts with their customers, they can sever the tie in writing. Sprint, for instance, sent letters to 1,000 of its problem custom-ers in 2007 canceling their wireless service contracts because they had made what the company deemed an unreasonable number of customer-service calls. In the absence of a contract, and particularly in a brick-and-mortar retail setting, ending relationships can be trickier. In 2003 Filene’s Basement prohibited two sisters with histories of ex-cessive returns and complaints from shop-ping at its stores. However, enforcing such bans is obviously difficult, and they can draw negative publicity.

A more feasible approach is to limit the resources devoted to problem customers. For example, in 2003, after Comcast dis-covered that 1% of its broadband customers were using 28% of its bandwidth, it warned those customers to limit their internet use. (Many cable internet service provid-ers impose caps on heavy users.) Similarly, service demanders who repeatedly call a

company’s toll-free number might be left on hold longer times.

Use the right metric. The most com-mon metric for assessing cross-selling campaigns is the average number of differ-ent products (or product categories) sold to each customer. Wells Fargo publishes this information in its annual reports and cites its desired cross-buy level—the number of products it wants each of its customers to own—as a key strategic goal. Like the finan-cial services firm discussed earlier, compa-nies commonly use this metric to create employee incentives.

But as we’ve demonstrated, cross-sell-ing as an end in itself is a bad idea. Before cross-selling to any customer or segment, determine whether the effort is likely to be profitable. Otherwise you may find losses mounting even as sales volume grows.

Remember our catalog retailer? When we examined its customer data, we dis-covered a group of problem customers who could have been identified two years into their relationships with the company. The retailer had unsuspectingly nurtured them, mailing them multiple catalogs and engaging in other cross-selling efforts. And regrettably, the promotions worked: Those customers bought 44% more items, on average, over three years—but during that time the average loss per customer more than doubled, resulting in an additional loss of $41 million.

Before you launch your next cross- selling campaign, pause and ask yourself,

“Do we really want these customers?” HBR Reprint F1212A

Denish Shah is an assistant professor of marketing, and V. Kumar holds the Lenny

Distinguished Chair in marketing, at Georgia State University’s J. Mack Robinson College of Business.

12

24

3

61

47

2231

19

51

6

24

FaSHion RetaileR

Catalog RetaileR

Retail BanK

hBR.oRG

December 2012 harvard Business Review 23