The Coins of Late Antiquity AD 400-700

-

Upload

syed-mustafa-ali -

Category

Documents

-

view

77 -

download

6

description

Transcript of The Coins of Late Antiquity AD 400-700

British Museum Keys to the Past

The Coins Oi

AD 400-70 Andrew Burnet

Andrew Curnett

Tie Coins of Late Antiquity 400700

Coins are reproduced x 1.5 except where indicated.

(Front corer) Enlargement of fig.14.

(Left) Enlargement of fig.21.

_imperial Coinage and Finance From about the second century AD the most formidable threats t the security of the Roman world came from the barbarian trib across the Danube and from the Parthians (and their Sassania successors) in the East. The main focus of the empire fell increasing' on the Danube-Persia axis, and Rome and Italy lost the preemine position they had formerly enjoyed. Diocletian (284-305) ha established his imperial residence at Nicomedia in north-we Turkey, and the shift of emphasis to the East found its culminatio in Constantine's foundation and dedication in 330 of the city Constantinople. •

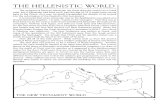

Another trend was towards fragmentation. The difficulty governing the empire from a single central point led to the establis ment of a system whereby there were several emperors (Augus and their junior colleagues (Caesars) at the same time, each taki special responsibility for a particular geographical area.. Togethe with the shift to the East this trend led naturally to the split of th empire : after 395 it was divided into the East ruled from Con stantinople by Arcadius (383-408) and his successors, and th West ruled from Italy by Honorius (393-423) and his successor The two parts were not reunited under a single ruler. until the rei of Justinian in the sixth century (see map, page 7), although in theo the empire remained a unity. Laws, for instance, were headed by t names of the current rulers of both parts of the empire, and coin issued by any emperor were legal tender throughout the empir Moreover a mint, whether it was in the East or the West, woul usually strike coins in the names of all the current emperors.

During the fourth century there had been some fifteen mints acti throughout the empire. As the empire collapsed in the fifth centur the number contracted : Anastasius (491-518) struck coins at onl four mints, and gold coins at only two. The number of mint increased again in the sixth century, particularly as a result Justinian's reconquest of much of the Western empire, until abo twelve were active. In the reign of Heraclius (610-41) most of t Eastern mints except Constantinople were closed. The Weste empire was again lost, and consequently by the ninth centw Constantinople was the only mint to issue coins regularly.

The mints were under the control of the comes sacrarurn lar tionum (Count of Imperial Expenditure), the head of one of the thr main financial departments. The other two were the res privata a

the praetorian prefecture. Each department was independent of t others and had, for instance, its own large central staff. The privata looked after the emperor's personal property (he owned to 20 per cent of some provinces) and the rents accruing from it. T department of the praetorian prefects was easily the most import •

and supervised the corn supply for the two capitals, the public p

5 or transport system and public works, particularly roads, bridges and granaries. One of its most important functions was the payment of troops in kind. The department of the sacrae largitones controlled not only the mints and the production of coins, but also mines, state factories and the provision of clothing for civil servants and the army. It was also responsible for the payment of cash to the troops. As well as their payment in kind (provided by the praetorian prefects) they were given a cash bonus or donative at the accession of a new emperor (five 'solidi', i.e. gold coins, and a pound of silver) and at intervals of five years (five solidi). These distributions were very important as the emperor's survival depended on the loyalty of the army, which could be ensured only by regular donatives.

Gold coins, of which the solidus and its third part or `tremissis' were the most important, were normally struck only at mints where the emperor was present (usually Ravenna in the West and Constan-tinople in the East). These mints signed their products with their abbreviated names, e.g. RV for Ravenna and CON for Constantinople

(figs.1-2). Western mints added com to the mint mark (fig.1), whic stood for comitatus and referred to the emperor's household an presence in the mint city. In both East and West the letters 013 wer added (figs. 1-2), standing for (aurum) ob(ryzum) or 'purified gold'

The types used on solidi varied from East to West. In the West th emperor's bust was normally shown in profile (fig.1), whereas in th East he was, with rare exceptions, shown almost facing, wearing helmet and holding a spear and a shield (fig.2); in 538 this was re placed by a facing bust with an orb and a shield (fig.3), and from th reign of Tiberius II (578-82) the helmet was often replaced by crown (fig.4). The reverses also varied. The predominant type of th western solidus of the fifth century showed the emperor holding long cross and trampling down a human-headed serpent (fig.1). I the East the usual type was the long cross supported by Victor (fig.2), which was introduced by Theodosius II in 422 and may we be connected with the raising of a large jewelled cross on the sup posed site of Golgotha two years before. This type persisted wit variations (fig.3) into the seventh century when it was supplants by a cross on steps (fig.4), which may also be a representation of t same monument.

Half solidi or semisses were minted in small numbers, but t production of thirds or tremisses was abundant froM the introdu tion of the denomination in 383. They always had a profile bust the emperor. In the fifth century the usual reverse types were t cross in wreath in the West (fig.18) and the facing figure of Victo in the East (fig.5).

With two exceptions, silver coins were only minted intermittentl and in small numbers. There was a plentiful coinage of silv siliquae in the late fourth century (fig.6), anti in the seventh centur Heraclius and Constans II struck numerous silver hexagrams (fig. some of which were made out of melted down church plate.

1. Valentinian III (425-55). Gold solidus. Mint of Ravenna. 2. Zeno (474-91). Gold solidus. Mint of Constantinople. 3. Justinian (527-65). Gold solidus. Mint of Ravenna. 4. Heraclius (610-41). Gold solidus. Mint of Constantinople. 5. Zeno (474-91). Gold tremissis. Mint of Constantinople. 6. Valens (364-78). Silver siliqua. Mint of Constantinople. 7. Heraclius (610-41) and his two sons. Silver hexagram. Mint of Constantinopl

See inside back cover for enlargement of fig.10.

It

During the fourth century bronze coins had been struck in a variety of denominations, but in the fifth century they were nearly all of a tiny size, about 9 millimetres in diameter. These `nummi' often had monograms of the emperor's name as their reverse type (fig.8), but one type has a lion (fig.9), a punning allusion to the emperor Leo (457-74). In the absence of any plentiful silver coinage, there was no common coin between the nummus and the gold tremissis (which seems to have been worth about 2400 nummi in the mid fifth century), but from 498 a series of large bronze denomina- tions was struck. The Vandals in Africa and the Ostrogoths in Italy provided the inspiration when they produced several denominations of large bronze coins in about 490. The Vandals and Ostrogoths may themselves have been prompted by the discovery of a hoard of bronze coins of the first century AD. The coins from this hoard were engraved in either Italy or Africa with a value expressed in nummi (Lxxxiii for the larger and xui for the smaller coins), and the convenience of these large denominations may have been the reason why the Vandals and the Ostrogoths produced similar large coins of their own.

The reforms in Africa and Italy were followed by the similar reform of the imperial coinage, introduced in 498 by John, the comes sacrarum largitionum of the emperor Anastasius. The reform had more than one stage, but it consisted essentially of the produc-tion of several large denominations of copper coins marked with their value in nummi expressed in Greek numerals :

M = 40 (called the `follis') (fig.10) I = 10 K =20 (called the 'half follis') E= 5

Nummi continued to be struck, and other denominations were made from time to time, for instance the 1B or 12 nummi coin at the mint of Alexandria. The numeral expressing the value occupied a prominent position on the reverse, and the obverse had the emperor's bust, at first in profile (fig.10) and from 538 facing.

The module and weight of the coins declined steadily until in the reign of Constans II (641-68) the follis was small and crudely produced (fig.11). There was a corresponding decrease in the number of small denominations struck : by the late sixth century the minting of nummi had been abandoned. By the early eighth century the production of five and ten nummi coins was dropped, and during this century the production of larger denominations was reduced to a trickle.

A solidus was probably worth 12 silver hexagrams in the reign of Heraclius, and there were 7200 nummi to the solidus in the mid fifth century. Under Justinian (527-65) there were 180 folles to the solidus. Some idea of the value of these coins can be given by their purchasing power. For example, in the fifth century the cost of maintaining a soldier was four solidi per annum. Contemporary prices show that this would have provided him with a pound of

meat, two loaves of bread, some oil and a bottle of wine every da Prices seem to have remained stable in terms of gold and therefor of solidi, since the solidus remained a coin of the same weight an fineness. The fluctuation in the quality of the copper coins, howeve and particularly their reduction in size, will have led to inflation a the value of the follis fell in relation to the solidus and its purchasin power.

Since the solidus was worth thousands of nummi, there was clearl a social need in the fifth century for a coin between the nummus an the gold tremissis. That such a coin was not produced for almost century reflects one of the major differences between ancient an modern attitudes to coinage. In the ancient world coins wer produced not to meet daily social needs, but as the medium of stat expenditure, pre-eminent in which was military pay. The greates priority of the late Roman and early Byzantine financial system wa the finding of sufficient quantities of gold to pay for the militar expenditure necessary to preserve the security of the empire and o the emperor.

8. Martian (450-57). Bronze nummus. Mint of Constantinople. 9. Leo (457-74). Bronze nummus. Mint of Constantinople.

10. Anastasius (491-518). Copper follis. Mint of Constantinople. 11. Constans II (641-68). Copper follis. Mint of Constantinople.

8

9

Figs.8 and 9 are reproduced x 2.

4

Reconquered by Justi n ian (527-65)

BURGUNDIANS

sTy, 4.c" r-- 4BVZA NTINE)

'1"-‘ EMPIR

kings conspicuously avoid (compare fig.12 with fig.21). Thi: suggests that with the fall of the Western empire the Vandal king: assumed the privileges they had previously acknowledged as the prerogatives of the emperor : to wear the diadem and to strike coin: in their own name.

They struck silver coins marked c, L (fig.12) and xxv DN. D

probably stands for denarius which may mean '10 nummi coin'. 1 so, these were coins of 1000, 500 and 250 nummi. The Vandal produced two series of large bronze coins marked with XLII, x (fig.13) and xii. The 42 and 21 nummi coins were sixths and twelft I

of the smallest silver coin, but it is not clear why the anomalo 12 nummi denomination was chosen. One of these series (fig.13) h the standing figure of a Vandal king on the obverse with the lege

12. Gelimer, king of the Vandals. Silver 50 denarii. 13. Vandals (late 5th century). Bronze 21 nummi.

The Mediterranean World in 53(

The barbarian tribes had no tradition of coinage. The first coins that they met were those of the late Roman empire, which they received as pay when fighting in the imperial armies, as `danegeld' for not attacking the empire or as the spoils of war. Consequently it is no surprise that they produced the same sort of coins as the Romans. They used the same denominations and their coins had the same general appearance, often closely imitating imperial prototypes. Tribes outside the boundaries of the old empire do not seem to have produced coins and most of the barbarian coinages were produced by tribes which had been settled in or seized part of the empire.

The coinages follow the same general pattern. Imitations of imperial coins (usually in the name of the contemporary emperor) would be made for many years, sometimes more than a century, and would then be replaced by a national coinage struck in the name of the barbarian king. This is an over-generalisation and there were exceptions ; for instance the Burgundians and the Suevi produced only imitative coins, while the Ostrogoths produced imitative gold, partially imitative silver and copper in the king's name all at the same time. It remains, however, generally true that imitative coin-ages were replaced by national ones, even though the change might take place at widely different times (the late sixth century for the Visigoths, but the late seventh century for the Lombards).

Barbarian coins were struck mostly in gold, and the gold tremissis was the most popular denomination. Silver was not extensively minted except by the Vandals and Ostrogoths (perhaps because of shortages of gold) and copper coins were confined to the Vandals, Ostrogoths and to a lesser extent the Burgundians.

The Vandals in Africa (429-533) The Vandals crossed the frozen Rhine in 406. They passed through France and, after some years in Spain, they crossed to Africa in 429 and established their kingdom there (see map).

It is not clear whether they produced any coins before the reign of their king Gunthamund (484-96), although some silver coins which were made in Africa and imitate coins of the emperor Honorius (393-423) have been attributed to them. Gunthamund and his successors provide firmer ground, since they place their names on the obverse, e.g. D(ominus) N(oster) REX GEILAMIR (fig. 12) on coins of Gelimer (530-33). The decision to mint their own coins may be connected with the end of the Western empire. After the deposition of the emperor Romulus Augustus in 476, his predecessor Julius Nepos was probably restored as titular emperor of the West until his death in 480, and he had no successor. At this point the coinage of the Vandal kings begins, and it may be significant that they adopt the diadem, the symbol of the emperor, which other barbarian

arbarrian Coinages

6

KARTHAGO, referring to the Vandal capital and mint. On the rever is the traditional symbol of North Africa, the horse's head, togeth with the denomination. At the same time nummi were struck in t king's names, but these are very rare.

The last king of the Vandals, Gelimer (530-33), was conquere by Justinian's general Belisarius and thereafter Africa remained part of the empire. A huge gold medallion (fig.14), equivalent t 36 solidi, was thought by later Byzantine historians to have bee struck on the occasion of the triumph celebrated at Constantinop11 for Belisarius's victory.

The Visigoths in Spain and southern France (418-711)

The Visigoths had invaded Italy in the first decade of the fifth centur and their king Alaric had forced the Roman senate to declare hi nominee Priscus Attalus as emperor (409-10). They failed, howeve to depose the legitimate emperor Honorius and soon retired southern France. They helped Honorius against the usurpz Jovinus in Gaul and against the Vandals in Spain, and were give a home in south-west France where they probably produced a sm. series of imitative gold and silver coins.

The Visigoths soon extended their kingdom into Spain, but thy lost most of France to the Franks in 507. For all this period t Visigoths produced imitative solidi and tremisses. Some of the tremisses do not copy the normal tremissis type (fig.15), but u instead a scaled-down version of the solidus type, the long cro supported by Victory (compare fig.15 with fig.2). From about 500 cross was put on the breast of the emperor and on the rever appeared a figure of Victory with a palm branch over her should, and a wreath in her hand and drawn in a distinctive style (fig.16 Although this new reverse had not appeared on imperial coins sin, about 400 some rare Ostrogothic tremisses of Theoderic (493-52 have it, and these Ostrogothic coins probably provided the prat,

type which the Visigoths copied. The tremissis increasingly became the more important denomi

tion and the imitation of solidi seems to have stopped in the ea sixth century. The module of the tremissis became more spread a fi thin and it was on such coins that king Leovigild (568-86) began t regal Visigothic coinage when he placed on them his own name a title with a stylised bust of himself. This bust was repeated on t reverse, whose legend gave the name of the mint. About fifty of the are named, but many were unimportant and the bulk of the coina: was produced at a few main mints like Toledo and Seville. Leovigill successors copied the pattern of his coins. The name of the king his title appear on the obverse, such as WITTIRICVS RE(X) on coins Witteric (603-9), and on the reverse the epithet of the king and t name of the mint, e.g. PIVS ELIBERRI for the mint of Eliberri nei modern Granada (fig.17).

Fig.14 is reproduced life size.

See front and back corers Or enlargement offig.14.

14. Justinian (527-65). Gold medallion. 15. Visigoths (late 5th century). Gold tremissis in the name of Zeno. 16. Visigoths (mid 6th century). Gold tremissis in the name of Justinian. 17. Witteric, king of the Visigoths. Gold tremissis. Mint of Eliberri.

18

19

See inside front cover for enlargement of fig.21.

23

Towards the middle of the seventh century the bust on the reverse was usually replaced by a cross on steps or the monogram of the mint city, but the general appearance of the Visigothic tremisses remained the same until the conquest of Spain by the Arabs in 711-3.

The Suevi in Portugal (409-585) The Suevi had accompanied the Vandals into Spain, but remained there when the Vandals crossed to Africa. A series of gold tremisses is attributed to them. They were struck at first in the name of the emperor Honorius, but the majority imitate the tremisses of the emperor Valentinian III (425-55). They have a distinctive repre-sentation of the normal cross in wreath type of tremissis (compare fig.18 with fig.19). Some of them have been attributed to the late fifth and sixth centuries, but it is by no means clear that any were struck after the death of Valentinian. Imitations usually have the name of the *current emperor, so it is quite possible that Suevian coinage may have virtually ceased with their crushing defeat in 456 after which they were confined to a small part of north Portugal (see map). They were finally destroyed in 585 by the Visigoths.

The Ostrogoths in Italy (493-553)

In 476 Julius Nepos had probably been restored as the western emperor by Odovacar or Odoacer, a man of royal barbarian descent (fig.20). After Nepos's death in 480, Odovacar ruled Italy acknowl-edging the eastern emperor Zeno, but in 488 Zeno commissioned Theoderic, king of the Ostrogoths, to reconquer Italy in his name. Theoderic's conquest of Odovacar in 493 may possibly have been the occasion on which a large gold medallion was struck-(fig.21). The portrait of the king is accompanied by the legend REX

THEODERICVS PIVS PRINCIS Ming Theoderic, the Good, the Prince') and on the reverse, a figure of Victory celebrates his conquest with the legend REX THEODERICVS VICTOR GENTIVM (Xing Theoderic, conqueror of the barbarians').

This is the only portrait of Theoderic which survives, as the gold and silver coinage of his reign (493-526) was struck in the name of the contemporary emperors Anastasius (491-518) and Justin (518-27). The reverses of the solidi occasionally add the king's monogram to the end of the legend (fig.22), and sometimes an abbreviation for the mint city appears next to the figure on the reverse, e.g. a monogram of R and V for Ravenna (fig.22). The coins of Theoderic and his immediate successors were struck at the mints of Ravenna, Milan and (particularly) Rome, but the coins of the last kings seem largely to have been made at the mint of Ticinum (=modern Pavia).

The Ostrogothic kings did not strike gold coins in such great numbers after Theoderic's reign, and this reduced production is probably the explanation of the increase in the number of silver

:1

coins which were issued. These normally had the head and name the Byzantine emperor on the obverse and the name of the Osti gothic king written across the reverse. During the reigns of Badu or Totila (541-52) and Theia (552-53), however, the contemporE, emperor Justinian was replaced by the long dead Anastasius a even, in the case of Totila, by the Ostrogothic king himse Dominus) N(oster) BADVILA REX appears on both the obverse a the reverse (fig.23). This is a reflection of the bad relations betwe emperor and king as the result of Justinian's invasion of Italy a campaigns against the Ostrogoths at the time.

Ostrogothic copper coinage was diverse in nature. The denomil Lions were the same as the Byzantine ones, and the coins are of marked with a numeral expressing their value in nummi v, X (fig•2 xx and XL. Sometimes the king appears on the obverse, in particu on the fine bronze coins of Theodahad (fig.24), but many of

18. Valentinian III (425-55). Gold tremissis. Mint of Rome. 19. Suevi (mid 5th century). Gold tremissis in the name of Valentinian 20. Odovacar. Silver coin. Mint of Ravenna. 21. Theoderic, king of the Ostrogoths. Gold medallion. Mint of Rome. 22. Theoderic. Gold solidus in the name of Anastasius. Mint of Ravenna. 23. Totila, king of the Ostrogoths. Silver coin. Mint of Ticinum. 24. Theodahad, king of the Ostrogoths (534-6). Bronze 40 nummi.

20

I 0

30

coins show instead the personification of a mint city, e.g. FELIX RAVENNA (fig.25). In this respect they resemble the large Vandal coins which had also preferred to name the city rather than the king. The reverses have either the king's name or one of a number of types derived from earlier imperial coins. The reverse of Theo-dahad's coins, for instance, copies coins of the first century AD.

The Lombards in Italy (568-774)

The emperor Justinian finally overwhelmed the Ostrogoths in 553, but fifteen years later Italy was invaded by the Lombards who had been driven south by their fear of the Avars on the Danube. For over a century the coins they produced were imitations of contem-porary gold and silver imperial coins. Some of these are thick and chunky like the later coins of the Lombardic dukes of Beneventum in South Italy, but others have a characteristic wide and thin flan with a rim around the type (fig.26). Most of these imitations were tremisses, and they copy the types of the contemporary Byzantine emperor, for instance Maurice Tiberius (fig.26).

During the reign of Cunicpert (688-700) these types were replaced by the king's own bust and name (e.g. D N CVNICPER(T): fig.27), and the figure of the reverse (derived from the figure of Victory on Byzantine coins) is identified by the legend as St Michael, scs MIHAHIL (fig.27). These types were later replaced by a cross on the obverse and a star on the reverse, and in the reign of Desiderius (757-74) the reverse legend named the various north Italian towns used as mints, for instance Lucca, Milan and Pavia.

Desiderius succumbed to Charlemagne's invasion of Italy in 774, and the Lombardic coins were soon replaced by Charlemagne's silver denier. The Lombardic duchy of Beneventum, however, produced gold coins from the reign of Gisulf (689-706) until the ninth century.

The Burgundians in southern France (5th century-534) The Burgundians had entered France in the early fifth century, and some gold solidi imitating those of the emperor Valentinian (425-55) have been attributed to them on the basis of style and find spots. More certain is the attribution of coins to their kings Gundobad (473-516), Sigismund (516-524) and Gondemar (524-32), for these coins have monograms of the king's name on the reverse. On a solidus of Sigismund, for instance, the obverse and reverse imitate coins of the emperor Anastasius, but a monogram of Sigismundus is placed to the left of the figure of Victory (fig.28). Gold tremisses were also struck, as were tiny silver and very rare bronze nummi, all with the kings' monograms. The coinage of the Burgundians, however, came to an end with their defeat by the Franks in 534.

The Franks in Gaul (5th century-751) The Franks had invaded France in the early fifth century, but di not rise to prominence until later in the century. Clovis (481-511 took over the last remnant of the Roman empire in the north

an( after his defeat of the Visigoths in 507, he added most of the sou to his kingdom. In 534 the Burgundians were conquered, and the territory became part of the Frankish kingdom, which therefo comprised most of France and West Germany.

Frankish coinage defies generalisation, since unlike the unifo coinage of the Visigothic kingdom it varied from region to regio In the sixth century most of the Frankish coinage consisted d imitations of imperial gold coins, but Theodebert (534-48), one Clovis's sons, issued a striking series of gold solidi and tremisses. these he placed his own portrait and name with the title D(omin N(oster) and epithet VICTOR (fig.29); and sometimes VICTOR w replaced by the title of the Byzantine emperor AvG(ustus). T coinage was untypical for its time and it attracted adverse comme from the contemporary Byzantine historian Procopius, w thought that it was not right for a barbarian king to replace t emperor's bust with his own on the obverse of his coin. Th Theodebert had done so was a reflection of his imperial ambitions he attacked Italy and even threatened to march on Constantinop1(

During the second half of the sixth century the weight of Franki solidi was reduced from 24 carats to 21. Consequently xxi appe as a mark of value on the reverse of the Frankish coins produced Provence in southern France. These solidi were struck for so forty years in the names of the Byzantine emperors from Justin (565-78) to Heraclius (610-41), but from the early seventh centu the emperor was replaced by the ruling king, e.g. Clothar II (584

628: fig.30). These coins were made until about 700. On the reve they had the mark of value and the abbreviated names of the mi of which the most important was MA = Marseilles (fig.30).

25. Ostrogoths (6th century). Bronze 10 nummi. 26. Lombards (late 6th century). Gold tremissis in the name of Maurice Tiberiu 27. Cunicpert, king of the Lombards. Gold tremissis. 28. Sigismund, king of the Burgundians. Gold solidus in the name of Anastasiu 29. Theodebert, Frankish king. Gold solidus. 30. Clothar II, king of the Franks. Gold solidus. Mint of Marseilles.

31

33

34

36

Much of the Frankish coinage of the late sixth and early seventh centuries does not, however, bear the name of the king or the Byzantine emperor, since there was a large coinage of tremisses signed only by moneyers. Well over a thousand moneyers are known. The reverses of their coins (fig.31) have the moneyer's name (e.g. ELEGIVS) and abbreviated title MONE= monetarius or `moneyer'. The reverse type is often a cross, for instance the Croix ancree which was introduced in about 610 (fig.31). The obverse has a conventionalised head with a legend which refers to the mint, e.g. PARISIVS for Paris.

The chronology of these coins is based on the purity of the gold from which they are made. There was a steady decline in the fineness of the few Frankish coins with kings' names, and the moneyers' coins can be given an approximate date by the corresponding decline in their purity. By such reasoning a date of c.625 has been suggested for the Frankish coins from the famous Sutton Hoo ship burial.

The debasement of the gold coins continued until it was as low as about twenty per cent. In the late seventh century a new coinage of silver `denarii' had begun, and, although there was an overlap of the two sorts of coin, the silver coinage replaced the gold in the early eighth century. The types on these are very degenerate : they usually have a head and an illiterate inscription, with a pattern or design (often a cross) on the reverse. It seems that most of these were produced by civic authorities, and moneyers rarely appear on them.

A new royal dynasty of the Franks was founded by Pepin the Short (751-81), who reformed the coinage in two ways. The dumpy silver coins of his predecessors were replaced by thinner and more spread coins (fig.32), probably in imitation of the contemporary Arabic dirhams of Spain and Africa (fig.39). Secondly the name of the king was placed prominently on the coins, e.g. PIPI(nus) R(ex) F(rancorum) of 'Pepin, king of the Franks', implying that the control of minting had again come under direct control of the crown. Exceptions were soon made to this royal prerogative. At first abbeys were granted coining rights and, as the power of the kings declined, feudal lords were also granted them. From this naturally developed the royal and feudal silver coinage of the French middle ages.

Anglo-Saxon England The widespread use of Roman coins in Britain had ceased in about 420. Thereafter coins were occasionally put in burials, but the economy must have reverted to a form of barter for the next two centuries.

In about 600 a moneyer named Eusebius appears to have made a gold tremissis of the Frankish type at Canterbury, and some Frankish coins entered the country in the early seventh century (e.g. in the Sutton Hoo ship burial), but coins were not otherwise made in England until after 630. The earliest English tremisses

(fig.33) were made mainly in Kent and London. They copied till weight and fineness of the contemporary Frankish gold coins. As ir France, a coinage of silver coins, conventionally called `sceatta (fig. 34), began and by the early eighth century this replaced the gold coinage. Many of the types used on these coins are derived fro 0 Roman coins (e.g. fig.33 is derived from solidi of the late fourt century), and it is possible that this influence is to be explained b the discovery at the time of hoards of the earlier Roman coins whic

fl thereby became available as prototypes.

Not very long after the reform of the Frankish coinage by Pepi the Anglo-Saxon coinage followed suit and the broad penny W. introduced. Some of the earliest of these (fig.35) were struck b, King Offa of Mercia (757-796), and from these developed t coinages of the later Anglo-Saxon kings.

The Rise of lisilarn The two greatest threats to the late Roman world had come fro the European barbarians and the Sassanian Persians in the Eas Barbarian coinages were largely confined to those tribes which ha( settled within the boundaries of the old Roman empire, and alwa looked to imperial coins for their inspiration. In contrast, the coi of the Sassanians were completely divorced from this tradition an( their thin silver coins have an entirely different style and appearance

On the obverse is the portrait of the king and on the reverse is t Zoroastrian fire altar with two attendants (fig.36). The Sassanian made virtually no gold coins (they may have used Roman an. Byzantine solidi instead); a king of Sri Lanka, when visited b

31. Franks (early 7th century). Gold tremissis of the moneyer Eligius. Mint of Par 32. Pepin, king of the Franks. Silver penny. 33. England (mid 7th century). Gold tremissis. 34. England (8th century). Silver `sceatta'. 35. Offa, king of Mercia. Silver penny of the moneyer Beaneard. 36. Khusro II, Sassanian king (590-628). Silver drachm.

(Right) Enlargement of fig. 10.

(Back cover) Enlargement of fig. 14.

Byzantine and Persian merchants, is supposed to have taken this as a sign of the inferiority of the Persian king to the Roman emperor.

The Sassanians were overthrown by the Arabs in the seventh century, and by the early eighth century the Arab invasions had swept through the Near East, Africa and Spain. The conquerors replaced the coinages of these areas with their own coins, which at first imitated imperial coins (figs.37-8). From about 700, however, the imitative coins were replaced by ones without figure types : the legends give the date and mint and a quotation from the Koran (fig.39).

Despite the cultural differences the coins of the Arabs and the Christian kingdoms of Europe were surprisingly similar. The physical shape of the Arabic dirham may have influenced the introduction of the broad penny, and the Arabs replacement of pictorial coin types by inscriptions written in lines across the coin was followed in France and England. The coins of Byzantium, however, had representational types. This contrast with the coins of the Christian kingdoms demonstrates that by the eighth century the development of European coin design had reached the point where little trace remained of its origins in the Roman empire of the fifth century.

37. Heraclius (610-41) and his sons. Gold solidus. 38. Arab dinar imitating the solidus of Heraclius. AD 693. 39. Arab silver dirham. AD 721. Minted in north Africa.

Further Reading

J. P. C. Kent and M. Hirmer Roman Coins (Thames and Hudson, 1977)

P. D. Whitting Byzantine Coins (Barrie and Jenkins, 1973)

P. Grierson Monnaies du Moyen Age (Fribourg, 1976)

© 1977 The Trustees of the British Museum Published by British Museum Publications Limited 6 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3RA ISBN 0 7141 0067 6 Designed by James Shurmer Printed in England by Martin Cadbury, Worcester