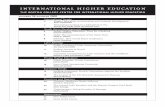

The Boston College Center for International Higher Education - Número 66

the boston college center for international higher · PDF filethe boston college center for...

Transcript of the boston college center for international higher · PDF filethe boston college center for...

international higher educationthe boston college center for international higher education

number 50 winter 2007

The 50th Issue of International Higher Education2 A Dozen Years of Service to Higher Education

Philip G. Altbach

2 Globalization and Forces for Change in Higher EducationPhilip G. Altbach

4 The Growing Accountability Agenda: Progress or Mixed Blessing?Jamil Salmi

6 Internationalization: A Decade of Changes and ChallengesJane Knight

7 Private Higher Education: Patterns and TrendsDaniel C. Levy

9 Graduate Education in Latin America: The Coming of AgeJorge Balán

11 International Research CollaborationSachi Hatakenaka

13 International Student Mobility and the United States: The 2007 Open Doors SurveyPatricia Chow and Rachel Marcus

15 The Management and Funding of US Study AbroadBrian Whalen

16 US Accreditation: International and National Dialogue Judith S. Eaton

Countries and Regions

26 New Publications

27 News of the Center

European Developments

18 The Private Financing of Higher EducationRyan Hahn

20 Higher Education Finance in GhanaFrancis Atuahene

The United States: Global Issues

21 Higher Education under a Labour GovernmentMichael Shattock

23 European Students in the Bologna ProcessManja Klemencic

Financing

Departments

25 Corruption in Vietnamese Higher EducationDennis C. McCornac

A Dozen Years of Service toHigher Education

This is the 50th issue of International Higher Education. Ourfirst issue appeared in the spring of 1995, almost 13 years

ago. Our commitment then, as now, is to provide thoughtfulanalysis of contemporary events in higher education world-wide and information on current developments, especially incountries that do not receive much attention. We have a specialconcern with the broad issues of globalization and internation-alization. Because of our sponsorship by a Jesuit university, wehave been interested in issues relating to Catholic and Jesuiteducation worldwide. Ours has been an effort at network build-ing and information provision.

We have focused attention on themes and countries some-times neglected in discussions of higher education. IHE hasfrom the beginning had a special interest in developing coun-tries—especially on how the developing world can cope withinternational trends largely determined by the major academicpowers. Among the topics we have emphasized over the yearshave been private higher education (our collaboration with theProgram of Research on Private Higher Education-PROPHE atthe University at Albany has been especially important), cor-ruption issues, internationalization and globalization, and oth-ers. A combination of independent and often critical analysis,focus on central issues for higher education worldwide, andshort but incisive articles has proved to be a successful strate-gy.

IHE is aggressively noncommercial. We do not charge for asubscription. We are always happy to provide permission, with-out any fee, to publications interested in reprinting our arti-cles. Our Web site is available without charge and is linkedwith many other Web sites focusing on higher education. Weaccept no advertising in any of our publications or on our Website. We have been able to do this work because of supportfrom the Ford Foundation and from Boston College.

International Higher Education is by now recognized as asource of information and analysis worldwide. We mail toreaders in 154 countries. IHE is available on our Web site andis widely used. We have been careful to archive all of the backissues and have indexed them so that researchers and otherscan have easy access. IHE articles are widely cited in the liter-ature and are often reprinted by journals in many parts of theworld. We currently work with publications in Mexico, theUnited Kingdom, the United States, and China that regularlyreprint our articles. IHE is translated into Arabic, thanks toGoogle, and we are working on starting a Chinese-languageedition in collaboration with the Shanghai Jiao TongUniversity Institute of Higher Education.

We have asked colleagues who have been associated withInternational Higher Education to reflect on some key trends in

higher education in an international perspective over the pastdecade of our publication. Several of these articles follow.Additional contributions will be published in the comingissues. We look forward to our 100th issue!

Philip G. Altbach, Editor

Globalization and Forces forChange in Higher EducationPhilip G. Altbach

Philip G. Altbach is J. Donald Monan SJ professor of higher education anddirector of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College.

What is globalization and how does it affect higher educa-tion policy and academic institutions? The answer is

deceivingly simple and the implications are surprisingly com-plex. For higher education, globalization implies the broadsocial, economic, and technological forces that shape the reali-ties of the 21st century. These elements include advanced infor-mation technology, new ways of thinking about financinghigher education and a concomitant acceptance of marketforces and commercialization, unprecedented mobility for stu-dents and professors, the global spread of common ideas aboutscience and scholarship, the role of English as the main inter-national language of science, and other developments.Significantly, the idea of mass access to higher education hasmeant unprecedented expansion of higher education every-where-there are about 134 million students in postsecondaryeducation worldwide, and many countries have seen unprece-dented and sustained expansion in the past several decades.These global trends are for the most part inevitable. Nations,and academic institutions, must constructively cope with theimplications.

Contemporary inequalities may in fact be intensified byglobalization. Academic systems and institutions that at onetime could grow within national boundaries now find them-selves competing internationally. National languages competewith English even within national borders. Domestic academ-ic journals, for example, often compete with international pub-lications within national academic systems, and scholars arepressured to publish internationally. Developing countries areat a significant disadvantage in the new globalized academicsystem, but smaller academic systems in rich countries alsoface problems. In a ranking-obsessed world, the top universi-ties are located predominantly in the United States, the UnitedKingdom, and a few other rich countries. The inequalities ofthe global age are just as profound and in part more complexthan the realities of the era of colonialism.

Academic systems will need to cope with the key realities of

international higher education

the 50th issue 2

the first part of the 21st century for higher education.Massification Massification is without question the most ubiquitous globalinfluence of the past half century or more. The United Stateshad the first mass higher education system, beginning as earlyas the 1920s. Europe followed in the 1960s, and parts of Asiaa decade or so later. The developing countries were the last toexpand. Most of the growth of the 21st century is taking placein developing and middle-income countries. There are nowmore than 140 million students in postsecondary educationworldwide, and this number continues to expand rapidly.North America, Europe, and a number of Pacific Rim nationsnow enroll 60 percent or more of the relevant age group inhigher education. What has massification brought?

Public good vs. private good. Stimulated in part by the finan-cial pressures of massification and also by broader changes ineconomic thinking, including the neoliberal agenda, highereducation is increasingly considered in economic terms a pri-vate good—a benefit accruing mainly to individuals whoshould pay for it rather than a public good that contributes ben-efits to society and thus should be financially supported by thestate.

Access. Postsecondary education has opened its doors to pre-viously excluded population groups—women; people fromlower socioeconomic classes; previously disadvantaged racial,religious, and ethnic groups; and other populations. Whilemany countries still contain disparities in enrollment, massifi-cation has clearly meant access and thus upward mobility andincreased earning potential. Access also greatly expanded theskills of populations, making economic expansion possible.

Differentiation. All mass higher education systems are dif-ferentiated systems. Institutions serve varied missions, withdiffering funding sources and patterns and a range of quality.Successful academic systems must ensure that the various seg-ments of the system are supported and sustained. Whileresearch universities need special attention, mass-access insti-tutions do as well.

Varied funding patterns. For most countries, the state has tra-ditionally been the main funder of higher education.Massification has placed great strains on state funding, and inall cases governments no longer believe they can adequatelyfund mass higher education. Other sources of funding need tobe found—including student tuition and fees (typically thelargest source), a variety of government-sponsored and privateloan programs, university income generating programs (suchas industry collaboration or consulting), and philanthropic

support.Decline in quality and conditions of study. On average in most

countries, the quality of higher education has declined. In amass system, top quality cannot be provided to all students. Itis not affordable, and the ability levels of both students andprofessors necessarily become more diverse. University studyand teaching are no longer a preserve for the elite—both interms of ability and wealth. While the top of a diversified aca-demic system may maintain its quality (although in somecountries the top sector has also suffered), the system as awhole declines.

Peaks and Valleys in Global Science and ScholarshipA variety of forces have combined to make science and schol-arship global. Two key elements are responsible. The growth ofinformation technology (IT) has created a virtual global com-munity of scholarship and science. The increasing dominanceof English as the key language of communicating academicknowledge is enhanced by IT. Global science provides everyoneimmediate access to the latest knowledge. Thus, everyonemust compete on the same playing field to participate inresearch and discovery. It is as if some teams (the wealthiestuniversities) have the best training and equipment, while themajority of players (universities in developing countries andsmaller institutions everywhere) are far behind. There isincreased pressure to participate in the international bigleagues of science—such as publishing in recognized journalsin English. Thus, while IT makes communication easier ittends to concentrate power in the hands of the “haves” to thedisadvantage of the “have nots.” National or even regional aca-demic communities, located in the valleys of higher education,are overshadowed by the peaks of the global academic powersthat dominate the new knowledge networks.

Globalization of the Academic MarketplaceMore than 2 million students are studying abroad, and it isestimated that this number will increase to 8 million by 2025.Many others are enrolled in branch campuses and twinningprograms. There are many thousands of visiting scholars andpostdocs studying internationally. Most significantly, there is aglobal circulation of academics. Ease of transportation, IT, theuse of English, and the globalization of the curriculum havetremendously increased the international circulation of aca-demic talent. Flows of students and scholars move largely fromSouth to North—from the developing countries to NorthAmerica and Europe. And while the “brain drain” of the pasthas become more of a “brain exchange,” with flows of both

3

international higher education

the 50th issue

Massification is without question the most ubiqui-

tous global influence of the past half century or

more.

The increasing dominance of English as the key lan-

guage of communicating academic knowledge is

enhanced by IT.

people and knowledge back and forth across borders andamong societies, the great advantage still accrues to the tradi-tional academic centers at the expense of the peripheries. EvenChina, and to some extent India, with both large and increas-ingly sophisticated academic systems, find themselves at a sig-nificant disadvantage in the global academic marketplace. Formuch of Africa, the traditional brain drain remains largely areality.

ConclusionThomas Friedman's “flat world” is a reality for the rich coun-tries and universities. The rest of the world still finds itself ina traditional world of centers and peripheries, of peaks and val-leys and involved in an increasingly difficult struggle to catchup and compete with those who have the greatest academicpower. In some ways, globalization works against the desire tocreate a worldwide academic community based on cooperationand a shared vision of academic development. The globaliza-tion of science and scholarship, ease of communication, andthe circulation of the best academic talent worldwide have notled to equality in higher education. Indeed, both within nation-al academic systems and globally, inequalities are greater thanever.

The Growing AccountabilityAgenda: Progress or MixedBlessing?Jamil Salmi

Jamil Salmi is the tertiary education coordinator of the World Bank,Washington, DC, USA. E-mail: [email protected].

Compared to the well-established tradition of accreditationin the United States, public universities in many countries

have typically operated in a very autonomous manner. In thefrancophone countries of Africa, for example, institutionsenjoy full independence in the selection (election) of their lead-ers and complete management autonomy. They do not have toanswer for their inefficient performance. In several LatinAmerican countries, the constitution entitles public universi-ties to a fixed percentage of the annual budget that they are freeto use without accountability. Some countries do not even havea government ministry or agency responsible for steering orsupervising the tertiary education sector.

In the past decade, however, accountability has become amajor concern in most parts of the world. Governments, par-liaments, and society at large are increasingly asking universi-

ties to justify the use of public resources and account morethoroughly for their teaching and research results. This under-taking may include many forms: legal requirements such aslicensing, accreditation, assessment tests to measure what stu-dents have learned; professional examinations; performance-based budget allocation; and governing boards with externalparticipants. Sometimes the press itself enters the accountabil-ity arena with its controversial league tables.

The Accountability AgendaNobody can argue that universities should not be accountable.First, governments are responsible for establishing a regulato-ry framework to prevent fraudulent practices. Accusations of

flawed medical research in the United Kingdom, reports ofAustralian universities cutting corners to attract foreign stu-dents, and the student loan scandal in the United States showthe need for vigilance, even in countries with strong accounta-bility mechanisms. Second, universities should legitimately beheld accountable for their use of public money and the qualityof their outputs (graduates, research, and regional engage-ment). The evolution toward increased accountability is reflect-ed in the expansion in the number of stakeholders, themesunder scrutiny, and channels of accountability.

The teaching staff has traditionally been the most powerfulgroup in universities, especially where the head of the institu-tion is democratically elected. Even at Harvard, the demise ofPresident Summers in 2006 was largely due to the oppositionof some professors. But today university leaders must at thesame time meet the competing demands of several groups ofstakeholders: (a) society at large; (b) government, which can benational, provincial, or municipal; (c) employers; (d) the teach-ing staff; and (e) the students themselves. Even within govern-ment structures, demands for accountability are coming fromnew actors—as has happened in Denmark, where responsibil-ity for the universities' sector is now with the Ministry ofTechnology.

The pressure for compliance comes through an increasing-ly broad variety of instruments. Government controls take theform of compulsory requirements, such as accreditation, per-formance indicators, and mandatory financial audits. They canalso operate indirectly through financial incentives such as per-formance—based budget allocation. In countries with a stu-dent loan system, these loans are usually available only forstudies in bona fide institutions. Innovative funding approach-es—such as the voucher systems recently established in thestate of Colorado and in several former Soviet Union republics

international higher education

the 50th issue4

Governments, parliaments, and society at large are

increasingly asking universities to justify the use of

public resources and account more thoroughly for

their teaching and research results.

or the contracting of places in private universities piloted inBrazil and Colombia—put the decision making on where tostudy in the hands of the students themselves. Establishinguniversity boards with outside members who have the powerto hire (and fire) the leader of the institution, as has recentlyhappened in Denmark, is another accountability channel. Inmany countries, accreditation reports are made available to thepublic, unlike the practice in the United States.

Public OpinionColombia was the first country in Latin America to set up anational accreditation system, but the number of programsreviewed by the new accreditation agency remained relativelylow because accreditation was voluntary and the most presti-gious universities did not feel any compulsion to participate.But after the country's main newspaper started to publish thefull list of accredited programs, many more universities joinedthe accreditation process out of fear of being shunned by thestudents. In the same vein, the Intel Corporation announced inAugust 2007 that due to quality concerns it was removingmore than 100 US universities and colleges from the list of eli-gible institutions where its employees could study, for retrain-ing, at the firm's expense.

The power of public opinion has been revealed in the grow-ing influence of rankings. Initially limited to the United States,university rankings and league tables have proliferated inrecent years, in more than 35 countries. Notwithstanding themethodological limitations of these rankings, the mass mediahave played a useful educational role by making relevant infor-mation available to the public, especially in countries lackingany form of quality assurance. In Japan, for instance, for manyyears the annual ranking published by the Asahi Shimbunnewspaper fulfilled an essential quality-assurance function inthe absence of an accreditation agency.

The Accountability Crisis In recent years, grievances about excessive accountabilityrequirements and their negative consequences have comefrom many quarters. In the United Kingdom and Australia, forexample, universities have complained of performance-indica-tor overload. In the United States, a controversy arose recentlyaround the recommendations of the US Department ofEducation Spellings Commission on the Future of HigherEducation regarding the need to measure learning outcomes.This reaction illustrates the weariness of the tertiary educationcommunity vis-à-vis accountability demands beyond accredita-tion. Another common complaint concerns the tyranny of therankings published by the press.

In developing and transition countries, university leadersmay accuse government of mixing accountability with exces-sive control. Comparing recent trends in two former SovietUnion republics, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, helps to illus-trate practices that may stifle the tertiary education sector. In2001, Kazakhstan introduced a voucher-like allocation systemto distribute public resources for tertiary education. About 20percent of the students receive education grants to study at thepublic or private institution of their choice. To be eligible, insti-tutions must have received a positive evaluation from the qual-ity-assurance unit of the Ministry of Education. As a result, alltertiary education institutions have become more mindful oftheir reputation as it determines their ability to attract educa-tion grant beneficiaries. In Azerbaijan, by contrast, theMinistry of Education controls student intake and programopenings, even at private universities. Thus, for the moredynamic tertiary education institutions it becomes extremelydifficult to innovate and expand.

Even in the absence of unethical behaviors, institutions maysuccumb to the natural temptation to pay more attention tothose factors that receive prominence in rankings. In theUnited States and Canada there have been rumors of universi-ties and colleges “doctoring” their statistics to improve theirstanding in the rankings.

Accountability often involves the need to reconcile multipleobjectives, some of which are incompatible. For example, thepursuit of equity may be defeated by high admissions require-ments—especially in countries like Brazil, with socially segre-gated secondary schools. While the proportion of low-incomefamilies is 57 percent in the state of São Paulo, it is only 10 per-cent at the University of Campinas (UNICAMP), one of thecountry's top universities.

On the positive side, however, many university leaders seekto make their institutions more accountable on a voluntarybasis. In the United States, for example, the same presidentswho decided in 2007 to boycott the US News and World Reportrankings announced that they would start publishing key per-formance indicators in the context of a Voluntary System ofAccountability Program. In Belgium, the Flemish universitieshave voluntarily joined the German ranking exercise forbenchmarking purposes. In France, ironically, when the gov-ernment in July 2007 offered increased autonomy againstmore accountability on a voluntary basis, there was a unani-mous outcry. The scope of proposed autonomy was thenreduced but imposed on all universities.

The Way ForwardThe universal push for increased accountability has made therole of university leaders much more demanding. This irre-versible evolution toward greater accountability has trans-formed the competencies expected of university leaders andthe ensuing capacity-building needs of university managementteams.

5

international higher education

the 50th issue

In recent years, grievances about excessive account-

ability requirements and their negative conse-

quences have come from many quarters.

Accountability is meaningful only to the extent that tertiaryeducation institutions are actually empowered to operate in anautonomous and responsible way. In the final analysis, theirsuccessful evolution will hinge on finding an appropriate bal-ance between credible accountability practices and favorableautonomy conditions. ________________Author's note: The findings, interpretations, and conclusionsexpressed in this article are entirely those of the author and shouldnot be attributed in any manner to the World Bank, the members ofits Board of Executive Directors, or the countries they represent.

Internationalization: A Decadeof Changes and ChallengesJane Knight

Jane Knight is adjunct professor in the Comparative, InternationalDevelopment Education Centre, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education,University of Toronto, Canada. E-mail: [email protected].

As we progress into the 21st century, the internationaldimension is a key factor shaping and challenging the

higher education sector in countries all over the world. Duringthe last decade internationalization has increased in impor-tance, impact, and complexity. It is a formidable force ofchange in its role as agent and reactor to the realities of global-ization. But are all these changes positive?

New ActorsFor several decades international academic relations have gen-erally been under the purview of ministries of education, cul-ture, and foreign affairs. Since the mid-1990s, ministries ofimmigration, trade, employment, industry, and especially sci-ence and technology have focused on the international recruit-ment of students and professors; the global competitivenessfor the production and commodification of knowledge; and thecommercial and economic benefits of cross-border education.Not only have additional national government agenciesbecome more engaged, so have intergovernmental bodies suchas UNESCO, and the Organization for Economic Cooperationand Development, and the World Bank, as well as internation-al and regional nongovernmental agencies. In fact, interna-tional education is now seen by both politicians and academicleaders as instrumental to regionalization initiatives such asthose underway in Europe through the Bologna process, inAfrica through the African Union higher education harmo-nization project, and the efforts in Latin America to work

toward a community of higher education. The role of highereducation as an international or regional political actor hasclearly gained ground in the last decade.

Increased Demand and a Diversity of ProvidersThe forecasted growth for international education moves from1.8 million in 2000 to about 7 million in 2025. This has majorimplications for the number and type of institutions, compa-nies, organizations, and networks involved in the cross-borderprovision of higher education. Traditional public and privateuniversities, primarily in Europe, North America, and Asia, aremore and more active in sending and receiving education pro-grams through a variety of delivery modes including franchis-ing, branch campuses, twinning, and distance. At the sametime, alternative or nontraditional providers are seeking busi-ness opportunities based on the rising demand for higher edu-cation and the attractiveness of foreign degrees for employ-ment mobility. As a result, more than 50 large transnationalcompanies are publicly traded on stock exchanges and areactive in providing international educational programs,degrees, and services on a for-profit basis. In addition, multi-tudes of small private companies are now involved in cross-border education. Many offer quality education programs andrecognized qualifications, but others are rogue, temporary, andunaccredited profit makers. The “for-profit” side of interna-tionalization is increasing in many countries of the world, butcertainly not all.

The recent inclusion of education services in the GeneralAgreement for Trade in Services has been a wake-up call forhigher education. As already noted, the export and import ofhigher education programs have been steadily growing, and soit should be no surprise that the World Trade Organizationsees the education sector as a lucrative market. But what isunexpected, and of concern to many, is that the movement ofprivate higher education services and programs between coun-

tries is now subject to multilateral trade regulations wherebefore it was done primarily on a bilateral basis, usuallybetween government departments related to education andforeign affairs—certainly not trade. This raises new implica-tions, questions, and challenges for higher education.

Quality A worrisome trend is the treatment of quality assurance andaccreditation as strategies for “international branding” andmarket position rather than for academic improvement pur-

international higher education

the 50th issue6

International education is now seen by both politi-

cians and academic leaders as instrumental to

regionalization initiatives such as those underway

in Europe through the Bologna process.

poses. The international ranking “game” is another illustra-tion of a preoccupation with international standings based onquestionable and biased indicators. To what end does thiscompetitiveness for international status serve? Is it toimprove higher education's contribution to solving some ofthe global challenges? Or is it a sign of the market approach,where often position is more important than substance?Internationalization can be used as a strategy to enhance theinternational, global, and intercultural dimensions of teachingand learning, research and knowledge production, and serviceto society. It also has the potential to improve quality, but a pre-occupation with status plus the emergence of rogue providers,diploma, and accreditation mills are overshadowing and jeop-ardizing the added value that internationalization can bring tohigher education.

Institutional Policies and ActivitiesMore institutions around the world are establishing a centraloffice and an institutionwide policy for internationalization.This trend takes many forms but illustrates a gradual changefrom a reactive ad hoc approach to internationalization to amore proactive planned approach. Nevertheless, a strategicapproach is still out of reach for most institutions.Considerations as to the obstacles with regard to international-izing an institution have evolved. Previously, the key barrierswere viewed as lack of senior-level commitment, finances, andpolicies. Currently, the major obstacles include lack of expert-ise in the international office and lack of faculty interest,involvement, and international/intercultural experience.Clearly, human resources are now a major challenge and inneed of more attention.

The approach of a long list of inactive bilateral agreementshas been shifted to participating in international or regionalnetworks. In fact, networks are becoming important brandingtools as institutions look for prestigious partners and fundingsources. Networks are often formed to enhance student andprofessor exchanges, develop joint curriculum and degrees,undertake benchmarking exercises, or engage in collaborativeresearch. In other cases, networks are oriented to cooperatingfor competitive purposes with regard to student recruitment,franchising programs, or applying for research grants. It isinteresting to note that the recent worldwide survey by theInternational Association of Universities found that the threemost important growth areas for internationalization includeinstitutional agreements and networks as number one, fol-

lowed by outgoing student mobility and international researchcollaboration.

International student recruitment remains a top priority fortraditional receiving countries like the United States, UnitedKingdom, Australia, and Canada; but new initiatives by sever-al European and Asian countries are making them populardestination points. The efforts of Asian countries and severalwealthy Gulf states are worth watching in the next few years asthey compete for increased market share of international stu-dents.

Rationales, Benefits, and RisksMany observers would claim that in the last decade they havewitnessed a dramatic movement of internationalization ratio-nales toward income production. While this trend may be truefor a small group of countries, it is certainly not the case for themajority of institutions around the world. A more accuratedescription is an increased diversification of rationales drivinginternationalization at institutional and national levels.Current leading motivations still focus on enhancing the inter-national knowledge and intercultural skills of students andprofessors, but other goals include the creation of an interna-tional profile or brand, improving quality, increasing nationalcompetitiveness, strengthening research capacity, developinghuman resources, and diversifying the source of faculty andstudents. In the past decade the importance and benefits ofinternationalization have been recognized, but at the sametime, new risks have been widely acknowledged. The mostimportant risks include commercialization, foreign degreemills, brain drain, and growing elitism.

All in all, we have seen a very dynamic evolution of interna-tionalization in the past 10 years. It is critical that we continueto nurture positive results and remain vigilant to potentiallynegative and unexpected implications so that internationaliza-tion builds on strengthening individual, institutional, commu-nity, and national development in the more interdependentand interconnected world in which we live.

Private Higher Education:Patterns and TrendsDaniel C. Levy

Daniel C. Levy is Distinguished Professor at the University at Albany, StateUniversity of New York, and director of the Program for Research on PrivateHigher Education. E-mail: [email protected].

In its 12 years, International Higher Education has publishedmany articles on the continued growth of higher education,

7

international higher education

the 50th issue

More than 50 large transnational companies are

publicly traded on stock exchanges and are active in

providing international educational programs,

degrees, and services on a for-profit basis.

as well as on related matters such as access policy. Within thispowerful higher education growth, even more spectacular isthe growth of private higher education. Today, best estimatesindicate that about one in three students globally is in the pri-vate sector.

There is no magic year that marks the inception of acceler-ated private growth. Certainly the last two decades have beenunprecedented in private growth, but each country has a differ-ent starting date or period in which private enrollment beginsto soar. As recently as 1980, while much of the world alreadyhad private higher education, still many countries did not. Nowvirtually all the world's regions have private higher educationin the large majority of their countries and pre-existing privatesectors have grown strikingly

The private higher education surge mixes with a substantialdegree of privatization in a range of other economic and socialfields. However, neither primary nor secondary education hasparalleled higher education for the proportional surge of pri-vate to total enrollment.

In some ways the most arresting private higher educationgrowth has come in regions where two decades ago, evensometimes one decade ago, there was no such sector. In theMiddle East, emergence is often basically a creature of the newcentury, otherwise of the 1990s. We are referring to such var-ied countries as Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Oman, Saudi Arabia, andSyria. With only scattered examples dating to the 1980s, pri-vate growth in Africa has more recently spread to country aftercountry, including all the largest ones. Predictably, the privatesector is larger in anglophone than francophone countries.

Latin America and Asia generally have longer continuousprivate higher education experience. But in the former it hasrecently grown to almost half (45%) of total enrollment andincludes every country except Cuba. Elsewhere in the regionsome countries have gone from minority to majority privateenrollment. Only with the 1989 fall of communism did privatehigher education emerge in modern eastern and centralEurope and it spread like wild fire in the first half of the 1990s.That leaves only western Europe as the outlier region wherethe public sector remains almost unchallenged by privategrowth (though it itself is partially privatizing). In Asia severalcountries, most importantly China, have launched private sec-tors. Several older private sectors account for most of theircountries’ higher education enrollment (notably Japan,Indonesia, the Philippines, South Korea, and Taiwan).

So powerful is global private growth that almost no country

has seen a decline of the private share in the last decade or two.This is not to rule out that changing national conditions couldlead to a decline. Those changed conditions could include anaging population (Japan, eastern Europe), partial privatizationof public sectors, and the threat that populist regimes such asVenezuela’s could curtail private institutions.

Follow the LeadersTwo very common myths about private higher education aremore false than true. One is that private-public differences areinsignificant as both types pursue public purposes. The secondis that each country is unique so we cannot intelligently gener-alize about private higher education. In fact, the private growthof the last decade or two is remarkable not only in weight butin replication of patterns long observed in other countries;among these patterns are prominent private-public differ-ences.

Regarding patterns of growth, for example, we continue tosee private emergence outside government plans (the MiddleEast excluded) and often taking officials and others by surprise.Private institutions continue to be considerably smaller thanpublic ones on average. The basic causes of private expansionremain religion, social advantage, and absorption of the accel-erated demand for higher education. As before, the causes ofthe growth now often shape the kind of ensuing private typethat functions.

In finance, the great majority of private institutions (old andnew) continue to be overwhelmingly financed privately, usual-ly through tuition and fees. Philanthropy, corporate contribu-tions, and alumni giving are still rare outside the UnitedStates, and elite private universities remain almost nonexistentoutside the United States. In governance, private institutionscontinue to be more hierarchical than public counterparts, lim-iting faculty and student participation. The private places stillconcentrate on a few fields, mostly in commercial areas. Theyremain narrower than public institutions in this and otherrespects. Another common and enduring private-public dis-tinction exists where the private institution represents a reli-gious or ethnic group. And concerning the demand-absorbinginstitutions a crucial challenge yesterday and today is to be ableto distinguish “garage” operations from serious operations.Even the serious institutions rarely pursue academic researchor graduate education and rarely have ample full-time facul-ties, top students, and laboratories and libraries.

New PathwaysBut it would be wrong to say there is nothing new under thesun. We should identify several key fresh tendencies andhybrid forms or developments. One tendency is the increasedrole of foreign institutions. In many instances they constructpartnerships with local institutions or government. Usually thepartnerships involve collaboration between countries of moreand less development. On both ends, the institutions may beprivate or public but probably a disproportionate share of the

international higher education

the 50th issue8

The last two decades have been unprecedented in

private growth, but each country has a different

starting date or period in which private enrollment

begin to soar.

involved local institutions are private. In other cases (e.g.,Greece) local institutions engaged in partnership with foreigninstitutions get leeway outside national rules (and cannot offernational degrees).

Local-foreign partnerships increasingly have a for-profitside. The financial incentive for Australian, UK, or US univer-sities is clear, even if their institutions are juridically public. Itappears that an increasing proportion of the local actors arefor-profit, in conjunction with “branch” campuses of foreignuniversities.

In other respects, the for–profit growth is yet more aston-ishing. Several for-profit businesses invest in higher educa-tion. The three most prominent internationally are Laureate(formerly Sylvan), Apollo (which owns the massive Universityof Phoenix in the United States), and Whitney International.Clearly these companies are in it for profit and do not claimotherwise. Alongside them is a growing list of domestic invest-ment companies. In some cases lines between ownership andinvestment are fuzzy. Laureate has often bought up existingprivate nonprofit institutions and invested, yet the institutionsremain legally nonprofit, as law in countries such as Chile andMexico proscribes for-profit higher education. However, theline between nonprofit and for-profit is notoriously unclear.Many legally nonprofit institutions are functionally for-profit,simply not distributing financial gains to stockholders.Meanwhile, even truly nonprofit institutions are becomingmore commercial. For-profit growth is one of the striking glob-al tendencies within the United States.

Even where the basic private types of yesterday are the pri-vate types of today, changed mixes emerge. There is a relativedecline of religious focus. Whereas elite private higher educa-tion is rare outside the United States, exceptions arise (perhapsTurkey's Bilkent University) alongside longer-standingJapanese and Korean cases. A much more common phenome-non is the development of “semielite” private institutions.These may evolve out of some of the serious demand-absorb-ing institutions. Though their elite nature may be more aboutclientele than academics, some do achieve distinction, often ina niche field. The niche field is usually business related.Semielite universities can be markedly entrepreneurial. Theycould evolve into a competitive threat to public universities ofthe second tier.

In terms of sheer numbers the most important privatedevelopment is the clear dominance of demand-absorbinginstitutions. In certain countries (e.g., Brazil, Philippines)such institutions have for many decades held the majority of

private enrollment, sometimes the majority of total enroll-ment. Now, however, the dominance in growth and enrollmentnumbers of these institutions spreads to more and more coun-tries. Unsurprisingly, the proliferation, against a legacy of littleregulation, has given rise to increased concern about qualityassurance and to the establishment of public accrediting agen-cies in country after country.

Graduate Education in LatinAmerica: The Coming of AgeJorge Balán

Jorge Balán is a senior researcher of the Centro de Estudios de Estado ySociedad in Buenos Aires and a visiting professor at the Ontario Institutefor Studies of Education at the University of Toronto. E-mail:[email protected].

Aresearch-based, academically oriented graduate programhad an early start in Latin America. In the 1950s and

1960s, many countries in the region established nationalcouncils for the support of scientific research and advancedtraining. During that period the leading public universitiessought to build a niche for advanced training and research toexpand and renovate the professoriate. Since the mid-1980s,the democratic regimes in the region have provided greaterinstitutional legitimacy and more generous funding toimprove the scale and scope of training and research. Withinthe public university, graduate education obtained a largerdegree of academic and administrative autonomy.

Flying under the radar screen of university politics, gradu-ate education is today perhaps the most dynamic and innova-tive sector of higher education. Its market is expanding anddiversifying, responding to the manpower needs of higher edu-cation and other economic sectors and to the career needs of agrowing number of graduates. Government plays a key role instimulating demand through regulation, incentives schemes,and the provision of funds for research and development. Thisarticle examines academically oriented graduate programs (theMA and PhD degrees) in a few major countries in the region.

Location, Scale, and Funding In 1985 Brazil developed a plan to send 10,000 studentsabroad for advanced training. However, during the 1990s thecountry gave priority to achieving greater domestic capacity forresearch and training in all areas of knowledge. Brazil is todaythe leader in the field of graduate education in the region, withan enrollment of over 100,000 graduate students in academic

9

international higher education

the 50th issue

The great majority of private institutions (old and

new) continue to be overwhelmingly financed pri-

vately, usually through tuition and fees.

degree programs, 38 percent of them in doctoral programs.Scientific production, 85 percent located in university researchand graduate training programs, has grown 2.5 times in thelast 15 years. Mexico shows a larger volume of graduate stu-dents but with a very different mix: around 100,000 studentswere enrolled in master's programs in 2005, five times morethan in 1990, but only 13,000 registered as doctoral students.Argentina ranks third, with almost 25,000 master's and 8,000doctoral students. Chile, a smaller country, currently enrolls13,000 master's and almost 3,000 doctoral students, whileColombia lags behind with less than 12,000 and 1,000 stu-dents in master's and doctoral programs (until recentlyColombia's graduate students largely concentrated in profes-sional specialization programs). In all these countries, the fig-ures correspond to accredited programs recognized by nation-al agencies mandating standards monitored through peerreview processes. Requirements vary significantly, with Brazilshowing the highest standards under a sophisticated qualityassurance system developed in the 1970s. The five countries,with a combined population of approximately 370 million, by2005 offered hundreds of doctoral programs, producing wellover 10,000 doctorates a year.

In contrast to China, Korea, or India, in the 1980s and1990s Latin America did not rely heavily on doctoral trainingoverseas, instead building upon previous investments toexpand the domestic supply. Today many fewer PhDs in theUnited States are granted to Latin American than to Asian stu-dents. In addition, Latin America tends to employ a largernumber of the graduates with doctorates the region producesin higher education. Moreover, a greater proportion ofBrazilians and Mexicans with PhDs earned in the UnitedStates—in contrast to Asians with US PhDs—plan to return totheir home countries.

Doctoral programs are largely concentrated in public uni-versities and almost entirely supported through public fundingallocated to education and/or scientific research. Private uni-versities, with few exceptions, lack the research infrastructurerequired for doctoral programs in the sciences and engineer-ing, although a number of these institutions are highly com-petitive in the social sciences and the humanities—fields inwhich the master's degree is most common. The recurrent fis-cal crises of the state and the equally recurrent governancecrises of the public university in Latin America have not inhib-ited the growing scale and production of graduate and doctor-al education, since the return to democratic regimes in theregion, in spite of neoliberal economic policies. Public fundingfor research has grown in absolute and relative terms. Braziltoday spends approximately 1 percent of its gross nationalproduct in research and development, up from 0.7 percent inthe 1990s, while Argentina and Chile spend a lower percent-age but also have significantly increased public funding forR&D during the years of rapid economic growth. Although stilla minor player in world science, the relative weight of LatinAmerica in world production has doubled in the last 15 years.

Industry plays a modest role in funding and execution ofresearch and employs few people with doctorates. Yet, publicuniversities with capacity for research developed technologytransfer programs, and many projects of university-industrycollaboration (with public-sector support) have proven to besuccessful.

Research and Graduate Education in the PublicMegauniversityAlthough the California three-tiered model was often in theminds of university reformers in Latin America, neither theidea of a research university nor the structure of a graduateschool ever took off in the region. Yet, research and graduatetraining are gaining a more comfortable niche within the tra-ditional megauniversity dominated by professional schoolsand professionally oriented undergraduate programs.

Governments have created significant incentives for univer-sities to develop and support graduate programs. In somecountries higher education institutions are required to offer anumber of research-based graduate programs to gain universi-ty status and thus enhanced autonomy. Graduate degrees aremandatory for entry into the academic profession and providesalary incentives to current faculty, thus fostering demand forgraduate education even in professional schools that tradition-ally required only a professional degree (i.e., engineering, law,medicine). Governments have negotiated loans from theWorld Bank and the Inter-American Development Bank tostrengthen public university research and graduate programs.

Accreditation of graduate programs has become widespreadsince the 1990s—the harbinger of broader efforts in qualityassurance. Peer review plays a key role in accreditation systemsand competitive research funding, strengthening the voice ofthe disciplinary-based academic communities in universityaffairs.

Reforms have often succeeded in shortening the length ofundergraduate professional programs to four or five years. Theexpanding number of graduates has created a larger demandfor professionally oriented graduate certificates and degreesoffered by the same units and faculty in charge of academical-ly oriented MA and PhD degrees. A market-driven, profession-ally oriented segment of graduate education provides someopportunities and fresh funding to the graduate faculty,enhancing its status within the university. Increased decentral-ization, administrative autonomy, and the pressure upon insti-tutions to diversify funding have largely favored graduate pro-grams and graduate faculty. Salaries for graduate faculty might

international higher education

the 50th issue10

Flying under the radar screen of university politics,

graduate education is today perhaps the most

dynamic and innovative sector of higher education.

be paid, or supplemented, by research agencies or specialfunding schemes outside of university control. Competitiveresearch funding, largely from public agencies, became therule. Graduate programs may charge fees, and in fact manyspecialization and master's programs are self-sustained.Diversity of funding at the graduate unit level broughtincreased autonomy vis-à-vis the central administration, withmore flexible contract arrangements and workplace rules.Thus, graduate education became a safer niche for research-oriented, full-time faculty than in the past within the profes-sionally dominated public university. The downside is thatoften this niche is quite isolated from the rest of university life,except for the market-driven specialization courses.

Last, but not least, the growth of graduate education is asso-ciated with increased differentiation within the professoriate interms of academic status, career orientation, and academic val-ues. While in the past an academically oriented professoriateconsisted mostly of a small group of foreign-trained and inter-nationally oriented scholars with a tenuous status within thepublic university, it has now become a major (although by nomeans predominant) segment of locally trained faculty, moreoften than not associated within graduate education.

ConclusionAlthough research and advanced training are certainly themost internationally oriented segments of higher education inLatin America, as elsewhere, the risks of parochialism andinbreeding are not to be dismissed when academic communi-ties are still relatively small, a sizable proportion of researchersare locally trained, and mobility is restricted by the small num-ber of research-oriented universities that often favor their owndoctoral graduates in recruiting new faculty. The reliance upondomestic publication in Spanish or Portuguese, particularlybut not solely in the social sciences and the humanities, is amixed blessing in this regard. Given the decreasing number offoreign-trained researchers in the region, a number of alterna-tives are actively explored by funding agencies, research uni-versities, and the academic community to counteract the risksof development. International coauthorship has increasedmarkedly in some countries and disciplines. Collaborativeefforts in quality assurance involving international counter-parts, often supported by international agencies, are numerousand productive. A number of research and advanced trainingcollaborative efforts are run with the support of electronicmedia, supplementing the expensive academic exchange pro-grams. Sandwich fellowships for doctoral students to spend

time in overseas laboratories and institutes to complete theirtheses have become very common. Internationalization is thusa priority on the agenda, yet it has to compete with many otherfactors for domestic funding at a time when internationaldonor agencies do not find compelling reasons to target theirefforts on Latin American countries.

New Developments inInternational ResearchCollaborationSachi Hatakenaka

Sachi Hatakenaka is an independent consultant and researcher on highereducation policy and management. E-mail: [email protected].

International research collaboration has always helped scien-tists to keep abreast of international science and to share

expertise and resources. Today, one-fifth of the world’s scientif-ic papers are coauthored internationally—a result of increas-ingly easy communication and cross-border travel. However, anew character of international collaboration is emerging, asscientific research has become an integral part of economicand innovation policy and international collaboration hasbecome a key element in globalization strategy.

The Background of Such ChangesThe perception of a “knowledge economy” matured.Knowledge economy has become a key term not only in devel-oped countries but increasingly in developing countries.Excellence in science is a prerequisite for future economic suc-cess, and international collaboration is seen as a key mecha-nism for international scientific competitiveness.

Some emerging economies, such as China and India, arechanging the meaning of international collaboration. Todayglobal networks are known to have contributed significantly tothe success of Silicon Valley. It is possible for the oldeconomies to benefit directly from the information technologyboom in India or from high-tech electronics in China, by beingconnected. Moreover, the success of these countries does notderive just from cheap labor. China and India are attractingglobal R&D activities—something that old economies in NorthAmerica and Europe have been trying to do for decades. Theold economies are keen to establish connections to these newpowerhouse economies—not only in downstream industriesbut also in upstream science.

The world is increasingly united on the need for researchand innovation to tackle global challenges such as poverty and

11

international higher education

the 50th issue

Doctoral programs are largely concentrated in pub-

lic universities and almost entirely supported

through public funding allocated to education

and/or scientific research.

climate change. The growing international concerns regardinggreenhouse gases, crises in Africa, or diseases in developingcountries are leading to new hopes about internationalresearch collaboration to address these issues.

Steps Taken to Encourage International CollaborationThe United States was one of the first nations to establish anapproach to attract the “best and the brightest” in the world totheir institutions. This policy placed the United States at theheart of international research collaboration, with USresearchers coauthoring with researchers from over 170 coun-tries. The unique US position was based, first, on the opennessof financial aid and fellowships supported any deserving grad-uate student. This system grew partly through generous feder-al research funding but also by means of institutional compe-tition to attract the best graduate students. Second, the tradi-tion of openness in hiring academics dated back to World WarII, during which many prominent European scientists movedto the United States. Third, the US labor market has been opento immigrants—particularly for highly skilled ones who couldget companies to sponsor them.

Today, more countries are taking comparable approaches toattract the “best and the brightest” through similar policies toopen up. The stepped-up competition for international stu-dents undertaken by other countries—most notably Australia,the United Kingdom, and Japan—and the tightening of USimmigration and security rules following September 11, 2001,led to the first period when the number of international stu-dents declined in the United States for several years. The trendhas since been reversed, owing in part to some steps alreadytaken to facilitate visa processing. Other immigration meas-ures, particularly to attract highly skilled international workers,are under discussion. Thus, competition will continue.

Since the late 1980s, Japan is a country that has been active-ly investing to become a viable destination for internationalstudents. Japan's strategy has been complemented by anotherapproach to promote international research collaborationthrough well-targeted programs, often based on bilateral agree-ments with collaborating countries. These activities cover jointresearch grants, research fellowships, and joint workshops andseminars—particularly in Asia. Today, their regular work withAsian peers shows that the Japanese researchers have becomekey players in the emerging Asian research hub.

Europe is going a step further. In its Seventh FrameworkProgramme, which just started this year, the European Union

(EU) announced its intention to “mainstream” internationalcollaboration across the range of its programs. In many ways,this policy is a natural extension of the EU's principle role—toencourage cross-border collaboration. However, the keychange is that the EU is now ready to invest in such work, par-ticularly with researchers in emerging and developing coun-tries, by supporting them to a greater extent than in the past.

The EU has also been strengthening its bilateral ties withkey emerging economies, most significantly China and Indiabut also Latin American countries as well as its neighbors—such as Turkey. China was its first Asian partner for scienceand technology (S&T) bilateral agreements a decade ago. Thisyear, the EU and China are jointly hosting a dozen or so eventsacross Europe and China to promote China-Europe S&T col-laboration. These special partnerships are being used to iden-tify specific research themes for targeting funding.

Another approach to international collaboration is to investin world-class research centers of excellence. Japan has beenstepping up its effort to create true hubs in global scientificnetworks through several programs, including the WorldPremier International Research Center Initiative. Singapore'sapproach has been much more aggressive; it was one of thefirst countries to use public money for attracting world-classinstitutions. Singapore has been at work for a decade tobecome a major Asian education and research center, by creat-ing high-profile international partnerships (with theMassachusetts Institute of Technology [MIT], Stanford,Berkeley, and Wharton—to name but a few), inviting world-class foreign universities to open campuses (e.g., INSEAD,University of Chicago Business School, and Waseda), and byits ambitious biomedical science park, Biopolis. However, notall of these ventures have worked. A partnership with JohnsHopkins University was terminated, and the University of NewSouth Wales closed its brand-new campus.

Singapore is not alone in funding institution-level partner-ships with an emphasis on research. The United Kingdom pro-vided its support for an MIT-Cambridge partnership, whichcovered not only education but also research. Scotland fol-lowed suit with the Stanford-Edinburgh link, which gives agreater focus on thematic research and commercialization. Inthe Middle East, many oil-rich nations have been investing ininternational educational partnerships. Recently, one unusualannouncement came from Abu Dhabi on an energy-researchinitiative called MASDER, which is to be based on multipleinternational research partnerships. There is also a California-Canada partnership with an emphasis on research, thoughthere is no promise of new public money. Portugal has alsorecently announced collaborative partnerships with MIT,Carnegie Mellon, and the University of Texas, Austin.

The Implications for Developing Countries For developing countries, these steps are likely to lead toincreases in scholarship and research collaboration opportuni-ties. Indeed, there is a specific focus on research for develop-

international higher education

the 50th issue12

The United States was one of the first nations to

establish an approach to attract the “best and the

brightest” in the world to their institutions.

ing countries. US foundations led the way in supporting pri-vate-public partnerships on key research and innovations—particularly to tackle infectious diseases in developing coun-tries. The need for action on climate change is also leading tonew dialogues to support research and innovation in develop-ing countries. The Department for International Developmentin the United Kingdom was one of the first official donors toarticulate a policy to emphasize the funding need for researchand innovation in international development.

International research collaboration has entered an era inwhich networking has a direct economic significance. Somegovernments are already beginning to pay a premium tobecome hubs in global excellence networks. The question iswhether these developments will produce significant changesin the world's research capacity. Will these reforms yield newcenters of excellence? Will one approach be more successfulthan others in creating effective networks? Finally, will thesetrends create capacity building for research in developingcountries or just more research relevant to developing coun-tries? Only time will tell us the true answers to these questions,but it is worth paying attention to these emerging trends.

International Student Mobilityand the United States:The 2007 Open Doors Survey

Patricia Chow and Rachel Marcus

Patricia Chow is Research Manager and Rachel Marcus is Research Officer,Institute of International Education. E-mail: [email protected]. Moreinformation about the Open Doors survey can be found at: http://open-doors.iietnetwork.org.

In 2005, more than 2.7 million students were pursuingtransnational higher education—a 47 percent increase over

the 2000 figure of 1.7 million students. A concurrent increasehas occurred in the number of students seeking an interna-tional education in nontraditional destinations in Asia, Africa,and Latin America. Several countries in these regions havepositioned themselves as key actors in the global economy,attracting more students to their shores. Despite these develop-ments, the United States continues to be the top host countryfor students seeking higher education abroad. In 2006, theUnited States attracted 30 percent of internationally mobilestudents among the leading eight host countries (Australia,Canada, China, France, Germany, Japan, and the UnitedKingdom).

This article draws upon key findings from the InternationalStudent Census of the recent Open Doors 2007: Report onInternational Educational Exchange to describe the currentinternational student population in the United States and toexamine the future trends in international enrollment. TheInstitute of International Education (IIE) has collected data oninternational student enrollment in the United States since1919 and in the form of the Open Doors survey since 1954.Annually, Open Doors surveys approximately 3,000 regionallyaccredited US higher education institutions on aspects ofinternational educational exchange. The 2007 survey reported582,984 international students studying in the United States

during the 2006/07 academic year—a 3 percent increase overthe previous year and the first significant increase in totalinternational student enrollment since 2001/02. In addition,the number of new international students—those enrolling ata US higher education institution for the first time—increasedby 10 percent, building upon the 8 percent increase seen in2005/06.

OriginsAsia remains the largest sending region, accounting for 59percent of total US international enrollments. The number ofstudents from Asia increased by 5 percent this year, driven byincreases from the top two sending places: India (10%increase) and China (8% increase). For the seventh consecutiveyear, India remained the leading place of origin of internation-al students in the United States, with 83,833 students. Chinaremained in second place, with 67,723 students and theRepublic of Korea in third place, with 62,392 students.

Turning to other regions, in 2006/07 we saw a 25 percentincrease in the number of students from the Middle East (to22,321 students), largely due to the 129 percent increase in stu-dent numbers from Saudi Arabia (to 7,886 students)—theresult of a large Saudi Arabian government scholarship pro-gram launched in 2005. Enrollments from Latin Americaremained steady in 2006/07, with Mexico sending the moststudents from the region (13,826). Kenya, with 6,349 students,was the only African country in the top 20 places of origin thisyear. The number of international students from Europe andOceania declined in 2006/07, to 82,731 and 4,300, respective-ly. Europe and Oceania are the only two world regions wherethe number of US students studying abroad in the regionexceeds the number of students from the region studying inthe United States.

13

international higher education

the united states: global issues

In 2005, more than 2.7 million students were pursu-

ing transnational higher education—a 47 percent

increase over the 2000 figure of 1.7 million students.

Student Profile and Fields of StudyOver the past 30 years, Open Doors data have indicated smallbut significant shifts in the demographics of international stu-dents. In 2006/07, 45 percent of international students in theUnited States were female, a 14 percent increase from the1976/77 figure of 31 percent. Also, a larger proportion of inter-national students were single in 2006/07 (87%), compared to30 years ago (74%).

As has been the case since 2001/02, international graduatestudents outnumbered international undergraduate studentsin 2006/07. Forty-five percent of international students weregraduate students, 41 percent undergraduates, and 14 percentnondegree/certificate students or students on optional practi-cal training.

Business and management remain the leading field of studyfor international students, with 18 percent of the total, followedby engineering with 15 percent. These two fields have been themost popular fields of study for international students over thepast five years. International students in the United States havea particularly large presence in sciences and engineering: in2006, non-US citizens earned 45 percent of all doctorates inthe science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields,and accounted for over half of all doctorate recipients in thefields of engineering, computer science, mathematics, andphysics (National Science Foundation, 2007 <www.nsf.gov>).

DestinationsInternational students were enrolled in all 50 US states in2006/07, highly concentrated in certain states and institu-tions. The 156 US campuses that enrolled (each) over 1,000international students, accounted for 58 percent of total inter-national student enrollment. The top host states are also hometo many of the top host institutions. Colleges and universitiesin California enrolled the largest number of international stu-dents (77,987, or 13% of the total), followed by New York(65,884 students, or 11 percent of the total). New York City wasthe leading metropolitan area, with 51,973 students, followedby Los Angeles, with 35,870 international students. Studentstend to cluster in areas with geographic and linguistic similar-ities to their home country, as well as an area with a large stu-dent or immigrant population from their home country.

Future Trends in International Student EnrollmentThese Open Doors findings, supported by similar data collectedby the Council of Graduate Schools and other surveys, suggestthat the number of international students in the United States

has rebounded and that the United States has not lost its attrac-tion as a destination of choice for international students. Inaddition to providing high-quality teaching, the Americanhigher education system is also esteemed throughout theworld because of the availability of advanced technologicalfacilities and extensive support for basic and applied research.

Meanwhile, US institutions have stepped up recruitment ofinternational students and adjusted their application proce-dures and admissions timetables to accommodate the leadtime needed for visa approval. These university-level effortshave been complemented by the US Department of State'ssteps to streamline the visa application and approval processand to promote the US as a welcoming place for internationalstudents.

While the results of these efforts by government and acade-mia appear to be turning the tide, more comprehensive stepsneed to be taken to ensure that this trend continues. Othercountries have also intensified efforts to attract internationalstudents, eliminating visa barriers and strengthening theirgraduate programs, especially in the sciences and engineering.Although the falling dollar may provide some relief, tuitioncosts in the United States continue to rise, ranging from anincrease of 6.6 percent for public universities, to 4.2 percentfor public two-year institutions. With the financial burdenlargely falling upon individuals and their families (62% ofinternational students use personal/family funds to pay for

their US education), it remains to be seen whether theseincreases will affect students' decisions to study in the UnitedStates. Widely disseminating information on financialresources and expanding financing options may help to allevi-ate the burden.________________Authors' Note: The Open Doors Project has received support from theBureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the US Department ofState since the early 1970s. The opinions expressed in this article areentirely those of the authors.

international higher education

the united states: global issues14

As has been the case since 2001/o2, international

graduate students outnumbered international

undergraduate students. Forty-five percent of inter-

national students were graduate students.

The number of international students in the United

States has rebounded and that the United States

has not lost its attraction as a destination of choice

for international students.

Visit our website for downloadable back issues of

International Higher Education and other publica-

tions and resources at http://www.bc.edu/cihe.

The Management and Fundingof US Study AbroadBrian Whalen

Brian Whalen is associate dean of Dickenson College and executive directorof the college's Office of Global Education in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, USA.He is also president and CEO of the Forum on Education Abroad. Web site:www.forumea.org. E-mail: [email protected].

US colleges and universities manage and fund study-abroadprograms in a tremendous variety of ways. The wide

range includes types of programs, policies for awarding aca-demic credit, structuring of study-abroad program fees, sys-tems for funding the study-abroad office, program evaluationmethods, and other areas of program management. US col-leges and universities frequently partner with overseas univer-sities and program providers.

A recent survey conducted by the Forum on EducationAbroad gives some useful data on the diverse managementpractices in US education abroad (www.forumea.org).Institutional members of the forum include 275 US collegesand universities, international universities, study-abroad-pro-gram providers, and independent organizations. This groupaccounts for approximately 75 percent of the US studentsstudying abroad each year. Over one-third of the membersresponded to the forum's survey, providing a comprehensivepicture of how US study abroad works.

Regarding their international education programs, US col-leges and universities have different approaches for developingand overseeing their curricula, which affects the education-abroad practices. The number and types of programs, the pro-gram models, the role of faculty, and policies for the awardingof credit vary from institution to institution. Study-abroad busi-ness models are based on the many factors influencing institu-tions’ decisions and best practices for funding educationabroad. Charging “home-school fees,” adding a study-abroadfee, negotiating a discount with a program provider, control-ling the number of students allowed to study abroad and forhow long include some of the practices that differ from insti-tution to institution.

Diverse Program TypesCurricular diversity can be seen in the many types of study-abroad programs offered by institutions. Over 85 percent of UScolleges and universities report that they offer multiple types ofeducation-abroad programs: with at least one special coursedeveloped for US or other international students on the pro-gram (93%); integrated university study, where students takeregular university courses (93%); reciprocal exchange (89%);and faculty-led, short-term (less than a quarter or semester)programs (86%). Additionally, over half the institutions offer

faculty-led, long-term (one quarter or semester or longer) pro-grams (55%), while in a number of cases faculty take studentsabroad for course work on sojourns rather than formallyapproved study abroad programs (53%). The majority ofprovider-funded study-abroad programs include at least onespecial course (95%), followed by integrated university study(60%), faculty-led, short-term study (50%), reciprocalexchange (30%), and faculty-led, long-term programs (10%).

Study Abroad FundingStudy-abroad offices and programs are generally fundedthrough the institution's general resources and revenue fromstudy-abroad-program fees. Three-quarters of US study-abroadoffices are funded by general funds, while half the institutionsfund the office through the study-abroad fees paid by students,with the average funding level consisting of 60 percent of theoffice’s operation. Most institutions support the programsfrom the general budget and study-abroad fees, although otherreported sources of funding include student fees paid by everystudent at the institution, restricted endowments, and costsharing provided by program providers.

Institutions and Program ProvidersUS colleges and universities often depend on study-abroad-provider organizations (both nonprofit and for-profit), overseasuniversities, and independent programs to organize these pro-grams; and these partnerships take many forms. Institutionspartner with provider organizations half the time (50%) whenrunning programs with at least one special course and no on-site participation by the institution’s faculty, and 35 percentcooperate with providers when offering nonexchange pro-grams with integrated university study.

Academic quality is the most reported factor that collegesand universities consider when deciding to affiliate with orapprove programs. The next most important factors reportedinclude health and safety, quality of program administrationand ease of working with program provider, in-country support(e.g., resident directors, cocurricular activities), and programstructure (e.g., direct enrollment, hybrid, field study). Notably,despite media reports about program discounts, the cost ofstudy-abroad programs ranks only sixth on the list.

Institutions set the fees for affiliated or approved study-abroad programs in different ways, with the single-most-com-mon practice being that students pay the program providerdirectly (35%). Other approaches are almost as common and

15

international higher education

the united states: global issues

US colleges and universities have different

approaches for developing and overseeing their cur-

ricula, which affects the education-abroad prac-

tices.

include students paying the institution for the program fee andthe institution then paying the program (31%); students payingfull-home-school tuition but paying for their own room andboard (29%); students paying full-home-school tuition andfees and the institution paying all of the program expenses,including room and board (18%). In addition, some institu-tions report that they assess an additional fee that study-abroadstudents must pay.

Institutions report that they commonly negotiate reducedprogram fees with provider organizations. Forty-four percentof institutions reported that in deciding whether to affiliatewith a program they negotiated fee reductions (“always” or“sometimes”) for each student sent on the provider’s program.Fewer institutions report that they (“always” or “sometimes”)negotiate rebates for each student sent (8%), with this rebatefunding used to support their study-abroad office. A morecommon approach employed by institutions is to negotiatescholarships for their students, with 38 percent of institutionsreporting that they (“always” or “sometimes”) take part in thispractice. Seventeen percent of institutions report that they(“always” or “sometimes”) negotiate scholarships based on stu-dent volume.

Also noteworthy, given the recent media coverage in theUnited States, only 3 percent (two institutions) reported havingexclusive agreements with program providers. “Exclusiveagreement” here refers to the practice of an institution notaffiliating with or not permitting a student to enroll in anyother study-abroad program in the same city, country, or regioncovered by the provider program. Based on the survey, exclu-sive agreements appear to be an uncommon practice.