T he P eloPonnesian War - Classical Christian...

Transcript of T he P eloPonnesian War - Classical Christian...

Aristotle was the first to

attempt a careful expla-nation of how historical writing differs from other types of writing. In his day, this meant distinguishing historical writing from

epic poetry, which was the only other type of writing about the past known to him.

The distinction between historian and poet is not in the one writing prose and the other

verse—you might put the work of Hero-dotus into verse, and it would still be a

species of history; it consists really in this, that the one describes the thing that has been, and the other a kind of thing that might be. Hence poetry is something more philosophic and of graver import than history, since

its statements are of the nature rather of universals, whereas those of history

are singulars (Aristotle, Poetics 9).

Thucydides does not neatly fit Aristotle’s notion of history. He saw the singulars of history as a window to universals. Thucy-

dides believed that the specific events of the Peloponnesian War manifested

the general way humans

T h e P e l o P o n n e s i a n W a r

o m n i b u s i V2

will act in similar circumstances. The human impulses that animated Athens and Sparta in the fifth century b.c. are the same impulses that guided human behavior in the Punic Wars, the Thirty Years War, the Napoleonic Wars, the Second World War, and America’s war in Iraq at the dawn of the twenty-first century.

General informaTion

Author and Context What little we know of Thucydides comes from auto-biographical traces we find in his work. He was Athenian, son of a man named Olorus. Thucydides operated gold mines in Thrace which gave him wealth and influence (1.1.1, 4.104.3). He began recording the events of the war immediately from the time it first began in 431 b.c. (1.1.1) and pointed out that at that time he was “of age to compre-hend events” (5.26.5). These remarks suggest that he was in his early adulthood at the outbreak of the war, which would mean that he was born sometime in the 450s. When plague hit Athens in the summer of 430, the disease afflicted Thucydides, but he survived (2.48.3). We find him commanding Athenian forces in Thrace in 424 and 423 b.c. During his command the city of Amphipolis, an Athe-nian ally in Thrace, defected to the Spartans. Thucydides claims he reacted to the crisis as soon as possible, and thanks to his quickness he prevented nearby Eion from defecting to Sparta as well (4.106.3–4). Nonetheless, the people of Athens held Thucydides responsible for losing Amphipolis and imposed a 20-year exile upon him. Thucydides reports that his exile proved advantageous for the writing of his history because it gave him access to the Peloponnesian view of events, which was unusual for an Athenian (5.26.5). Indeed, Thucydides was aware that his judgment could be clouded by the fact that he was a participant in the war. “I did not even trust my own impres-sions,” he said (1.22.2). The Roman Lucian praised Thucy-dides’ relentless pursuit of objectivity:

There stands my model, then: fearless, incorrupt-ible, independent, a believer in frankness and veracity; one that will call a spade a spade, make no concession to likes and dislikes, nor spare any man for pity or respect or propriety; an impartial judge, kind to all, but too kind to none; a literary cosmopolite with neither suzerain nor king, never heeding what this or that man may think, but set-ting down the thing that befell.1

Thucydides’ attitude toward truth and objectivity exem-

plifies an intellectual movement that moved among some elites at the time. Proponents of this movement were highly skeptical of supernatural claims and sought truth through the careful observation of nature. A good illus-tration is Thucydides’ highly clinical description of the plague that swept through Athens in 430 b.c. (2.48–54). Among Thucydides’ contemporaries who also adhered to this secular and rationalistic view of knowledge and reality were the physician Hippocrates, the philosopher Anaxagoras, and Pericles the Athenian statesman.2 Thucydides’ earlier contemporary, Herodotus, did not share these ideas.

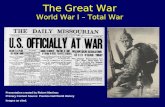

Significance Secretary of State George C. Marshall was the architect of U.S. foreign policy immediately following World War II when the U.S. entered into a tense Cold War with the Soviet Union. He also read Thucydides. In 1947 he con-templated a new global situation that placed the United States as a global superpower. He said, “I doubt seriously whether a man can think with full wisdom and with deep conviction regarding certain of the basic international is-sues today who has not at least reviewed in his mind the period of the Peloponnesian War and the fall of Athens.”3

Thucydides’ analysis of the Peloponnesian War has shaped intellectuals and statesmen alike through-out modern times. His outlook deeply influenced early modern political theorists such as Niccolò Machiavelli and Thomas Hobbes. It also guided many nineteenth-century heads of state in Europe, most notably Otto von Bismarck. Twentieth-century advocates of Thucydides’ outlook include Hans Morgenthau and Edward Carr. Among American statesmen, we see his influence in the policies of Secretary of State George Marshall, ambas-sador to the U.S.S.R. George F. Kennan, and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. Thucydidean ideas have also been proposed as a guide for U.S. policy for the post-Cold War era by Dennis Ross, who held influential diplomatic posts in the administrations of George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama.4 Whether you agree or disagree with Thucydides’ perspective, it is a perspec-tive that has shaped many statesmen and is one that we must take into account.

Main Characters The second half of the fifth century b.c. is often called the “age of Pericles,” so named after Athens’ leading man of the era. We first encounter Pericles in history when he sponsored the playwright Aeschylus in around 472. Ten years later he came to prominence in Athenian politics

The Peloponnesian War 3

when he opposed a faction that wanted Athens to be-friend Sparta. Beginning in 460 and for 29 years thereaf-ter, the Athenians annually elected Pericles to the office of military archon, or strategos (often translated into Eng-lish as general). His policies led to a string of skirmishes against Sparta that are collectively known as “The First Peloponnesian War” of 461–446, which concluded in the “Thirty Years Peace.” Pericles also oversaw a massive public building campaign that included the construction of the Parthenon. He died in a plague that swept through Athens in 429. Thucydides had great respect for Pericles, but little respect for Athenian leaders who came after him. Among them was Cleon, who figures prominent-ly in books 3 and 4. Thucy-dides uses Cleon as a foil to set up Dodotus’s brilliant speech in book 3, and also blames him (and the Athenians who supported him) for refus-ing a generous offer of peace from Sparta, a peace that Peri-cles would surely have accepted (4.17–22, 41.4). While Cleon is leading Athens in some bad decisions, Brasidas, an effective Spartan leader, enters the narrative. Brasidas was important because he seems to be the only Spartan who understood how to defeat Athens: not by a direct invasion of their territory, but by supporting rebellions among Athens’ subject states. Athens’ allies were the source of Athenian strength (cf. 2.13.2, 65.7). Thucydides recognizes Brasidas’s valor in a few places (e.g., 2.35.2, 3.79.3, 4.11.4) and shows that his leadership was especially effective in a campaign through Thrace (book 4). Other significant characters include Nicias and Al-cibiades, who are discussed below.

Summary and Setting Our name for this conflict, the “Peloponnesian War,” was coined a few centuries ago. It reflects the western

affinity for classical Athens that pervaded early modern Europe. (What Americans refer to as “the Korean War” is surely not what Koreans call it!) Interestingly, though Thucydides was Athenian, he called the conflict by a less partisan name than we give it: “the war between the Pelo-ponnesians and the Athenians” (1.1.1). This great war lasted from 431 to 404 b.c. Some people today mistakenly think of the Pelopon-nesian War as a civil war because it was a war in which Greeks fought Greeks. But this overlooks the fact that Greek cities in this era were separate political entities,

distinct from one another. Thus the Peloponne-sian War was an international conflict

that convulsed the entire Greek-speaking world. Even Persia,

the great near-eastern em-pire of that age, became

deeply involved. From the Greek perspective, this

was literally a world war. In book 1, Thucydides outlines his

approach and then addresses the causes of the war. This book is divided into five sections.

The first is a brief introduction in which Thucydides as-serts that the war between the Peloponnesians and the Athenians was the “greatest movement” in history up to his time (1.1.2). Then follows the second section, called the Archaeology, in which Thucydides defends his “great-est movement” claim while at the same time he explains methods of fact-finding (1.2–23). Here he reviews the most important Greek wars of the past, the Trojan War and the Persian Wars, in order to minimize their great-ness in comparison to the war he is writing about. At the end of this section (1.23.5–6), Thucydides distinguishes two causes of the Peloponnesian War, which form the structure of the remainder of book 1. The first cause is

Thucydides thought highly of Pericles, the

Athenian leader who consis-

tently opposed Sparta.

Among other notable acts,

he sponsored the playwright Aeschylus and

oversaw the con-struction of the

Parthenon.

o m n i b u s i V4

and child rearing, clothing, and other aspects of culture. Thucydides’ approach to history resembled that of many modern historians from the enlightenment era through the nineteenth century. A good representative is Edward Gibbon, who wrote in his famous Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire that “wars, and the administration of pub-lic affairs, are the principal subjects of history” (ch. IX). Like many who came after him, Thucydides saw this as the most rational or scientific way to look at human soci-ety. We find almost nothing in his work about private life, religion or kinship. As an observer of politics, however, Thucydides has much to offer. Thucydides sometimes refers to himself in the third person, as though he as a writer stands with Olympian detachment from the events he describes (1.1.1, 4.104–106). He cleanly separates Thucydides the historical ac-tor from Thucydides the writer of history. Indeed, Thucy-dides believes that history is made up of an objective body of facts about the past, and that these facts can be accessed and understood by any observer who employs the proper method to get at them. Any intelligent observ-er should see the same facts the same way. Thus, in the age-old debate over whether history should be grouped among the sciences or the humanities, Thucydides is a science man. A key assumption underlying any scientific pursuit is that the thing being studied behaves in a law-like man-ner—it acts consistently, predictably. This is how chem-ists and physicists think about the natural world, or at least the parts of it they study. Some disciplines treat hu-mans in a similar way. Sociology and modern economics are good examples. Practitioners of these social sciences treat human actions as data points, compile and organize them, analyze them with statistical tools, and use the re-sults to form theories about human behavior in general. Social sciences arose a little over a century ago. Around the turn of the nineteenth century, intellectuals began viewing humans as part of nature rather than above, distinct from, or different from nature. If humans func-tion within the ordinary operations of nature, then they can be studied using the same methods we use to study nature—that is, with scientific methods. Out of this intel-lectual transformation came many new developments in the nineteenth century, including an evolutionary view of human origins, advances in modern medicine, and the rise of the social sciences. Thucydides would probably have been comfortable with these changes. While he seldom used numbers, averages or statistics (though one place where he does is 1.10.4–5), he certainly analyzed the past in a systematic way in order to theorize about human behavior in general. For Thucydides, social and political laws are like natural laws. This is why, for more

the pretext for war, or the grievances each side had against the other. It boils down to a quarrel over who broke a treaty to which they had agreed back in 446 b.c. Then Thucy-dides mentions the “real cause,” kept hidden, that actually motivated Athens and Sparta to fight one another. In the third part of book 1 Thucydides recounts the first kind of cause, or the pretext for war, which features Corcyra and Potidaea (24–88). In the fourth part, Thucydides narrates background to what he deems to be the war’s real cause, which is the growth of Athens and the fear it aroused in Sparta (89–117). Finally, in the remaining fifth part of book 1, he returns to the pretext for war, describing nego-tiations prior to the outbreak of war (118–146). Thucydides turns to the war itself beginning in book 2. The first phase of the war is called the Archidamian War after the Spartan king Archidamus. The Archida-mian war lasted from 431–421 b.c. and spans books 2 through 5.24 in Thucydides’ account. This first phase concluded when Athens and Sparta reached an agree-ment called the Peace of Nicias, named for the Athenian leader who represented Athens in the negotiations. Ten-sions continued under the Peace, which Thucydides de-scribes in the rest of book 5. Books 6–7 recount Athens’ magnificent but ill-fated expedition to Sicily. Many have said that Thucydides’ account of the Sicilian expedition is the greatest narrative in all western literature. Toward the end of the expedition, Athens and Sparta came to blows once again, shattering the Peace of Nicias. This brought the war into its final phase from 413–404 b.c. This phase is called the Decelean War, so named because an important strategic feature of this phase was the Spar-tan occupation of Decelea, a small city dangerously close to Athens. The final book of Thucydides, book 8, opens with events in 413 b.c. and continues to an abrupt end in the middle of 411 b.c. Leaving his work unfinished, Thucydides does not record the final seven years of the war. The Greek historian Xenophon, not Thucydides, is our most important source for the end of the Pelopon-nesian War and the fall of Athens.5

Worldview Historians inevitably infuse their own understanding of human nature and society into their narratives of the past. This is certainly true of Thucydides. He believed that political ties are more important to one’s identity than ties of kinship, friendship, religion or business. He saw the office of citizen as more important than the office of mother or husband. Not surprisingly, his history focuses on politics to the exclusion of other dimensions of society and culture. In this way he differed sharply from Herodo-tus, who wrote a good deal about religion, diet, marriage

tives. When the Greek cities invited Athens to lead them in their campaigns against Persia, Athens accepted the invitation—as any city would have—because it suited her interest to do so. Later, when their leadership became irksome to the various Greek allies, Athens tightened her grip on these allies because she feared what could hap-pen if they lost control of cities that despised her leader-ship. These disgruntled allies would surely look for help from Athens’ rival, Sparta, thereby causing Athens to lose face (honor), not to mention the tribute she received from these allies (interest). “It follows,” they explained,

that it was not a very remarkable action, or con-trary to the common practice of mankind, if we did accept an empire that was offered to us, and refused to give it up under the pressure of the three strongest motives, fear, honor, and interest. And it was not we who set the example, for it has always been the law that the weaker should be subject to the stronger (1.76).

Notice that Athens’ policy toward her allies accordedwith “the common practice of mankind” and reflected an unchanging “law.” This is a law of national behavior that the Spartans themselves followed, just as any nation would (1.75–76). In Thucydides’ outlook, the motives fear, honor, and

than a century now, scholars have described Thucydides’ approach to history as “modern.” Thucydides believed that anyone who understands the general rules or common habits of human action will be able to predict how people (or nations) are likely to be-have in certain situations. He measured the value of his work by how well it fostered this skill: “. . . if it be judged useful by those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the understanding of the future, which in the course of human things must resemble it if it does not reflect it, I shall be content.” Thucydides’ proj-ect was far more ambitious than merely setting forth a re-liable account of the Peloponnesian War. He treated the war as a lens through which to study the general work-ings of human society, which can be applied to any age. “I have written my work,” he says, “not as an essay which is to win the applause of the moment, but as a possession for all time” (1.22.4). Political science is the social science that captured Thucydides’ attention. His political philosophy can be summarized in five basic principles. The first principle is the most important. Thucydides held that nations act according to three basic motives: fear, honor, and inter-est. When Peloponnesian cities complained about Athe-nian supremacy, Athenian representatives explained that their city’s actions were grounded in these three mo-

The Peloponnesian War 5

Thucydides believed that no

city-state answered to any law higher

than itself. This means that the

realm of interna-tional relations is a free-for-all. Put

simply, the world is in a perpetual state

of international anarchy.

o m n i b u s i V6

do what they can and the weak suffer what they must” (5.89). Thucydides believed that morality has a place in political events, but only a subordinate place. Power sits in the driver’s seat. Fourth, Thucydides believed that hegemony brings order and peace among the nations. Hegemony is a con-dition in which one nation is preeminent and exercises control or influence over the others. The presence of a hegemonic power diminishes the chaos of international rivalry due to several factors. Less powerful nations will either ally with or oppose the hegemonic power. Allying with the powerful nation brings trade and military pro-tection to a smaller nation. The small nations who dislike the hegemonic power are unlikely to take up arms against it for fear of being crushed. The hegemonic power, in turn, shapes its own policies to preserve its superiority. Because war tends to disrupt the status quo, a hegemonic power is unlikely to instigate war. If war does break out, the strongest nation will step in to contain it and bring it to a speedy end. Thucydides credits hegemonic power with the high-est attainments of Greek antiquity. For example, in the Minoan era, King Minos of Crete wielded hegemonic power over the Aegean islands. He expelled the Carians (who were pirates that disrupted trade) and through his power he ushered in a heyday of trade and communica-tion among various Greek peoples (1.4, 7–8). Thucydides had a similar view of Mycenean power under Agamem-non’s leadership during the Trojan War. According to leg-end that survives in Homeric epic, leaders of the Achaean armada assembled against Troy to fulfill an oath. But Thucydides attributes the fleet to Agamemnon’s “supe-riority in strength;” those who followed his command did so out of fear (1.9). During the half-century interval between the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, Athens became the greatest hegemonic power in Greek history (1.10.3; cf. 1.118.2, 3.10–12, passim), an assess-ment that figured into Thucydides’ claim that the Pelo-ponnesian War was the greatest disturbance yet known. The fifth principle has to do with the political order within a nation rather than between nations. Thucydides believed that it is advantageous to align the personal am-bition of a capable leader (or leaders) with the national interests of his city. In Thucydides, this principle plays out in the careers of Pericles and Alcibiades. Thucydides admired Pericles for exercising inde-pendent control over the Athenian people, going so far as to say that during his tenure Athens was a democ-racy in name only (2.65.9). Pericles urged Athens not to give in to Sparta’s ultimatum, thereby bringing on the war (1.139–146). He also orchestrated Athenian strat-egy in the early years of the war (2.13.2, 65.7), a strategy

interest sometimes converge, but at a given moment one may be more prominent than the other two. Interest is the motive that seeks national gain, whether it is a gain in wealth, strategic advantage, or honor. Fear is the motive that seeks to prevent the loss of any of these qualities. Honor is a motive that seeks prestige, eminence or “face.” It has more to do with a nation’s standing relative to others than with being known as a virtuous nation. Of the three, honor is the most confusing to us because our western notion of honor is laden with Christian underpinnings. Remember that Thucydides lived in Greece five centuries before the arrival of Christianity. In Thucydides, Pericles’ speeches illustrate the motive of honor nicely. He urged Athens not to yield to a trifling Spartan demand, saying, “. . . make them clearly understand that they must treat you as equals” (1.140.5). He praised Athens in his famous funeral oration by saying, “Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves” (2.37.1). This same sense of honor figures prominently in Homer’s Iliad. Achilles quarrels with Agamemnon and leaves the battle because Agamemnon slighted his honor. Second, Thucydides believed that nations (or in his Greek context, city-states) are truly sovereign. No nation answers to a law above itself. Thus, when two nations come into conflict, there is no higher court of appeal that can rightly claim jurisdiction over both. No legitimate authority exists that can preside over and adjudicate the dispute. This means that the realm of international rela-tions is a free-for-all. Put simply, the world is in a per-petual state of international anarchy. Third, in the absence of an enforcer to which all the nations are beholden, nations work out their differences by appealing to power or force. This does not mean that nations will always fight all the time, as many mistak-enly assume. Fighting is often disadvantageous to one or both sides in a dispute. Nonetheless, weaker nations tend to make concessions to stronger nations, and stron-ger nations tend to place demands upon weaker nations. Thucydides filled his work with examples of such com-plex power relationships among the Greek cities. Thucydides acknowledged that nations justify their policies by appealing to justice and morality. Every nation will claim that it is always “doing right.” This is certainly true of nations in a dispute with one another. Thucydides believed that, in the end, neither justice nor righteous-ness can settle the dispute. But power can, and always will, settle such disputes. The cleanest summary state-ment of this principle appears in an Athenian speech to the ignorant leaders of the puny island of Melos: “. . . you know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong

The Peloponnesian War 7

ous Nicias in command. By preferring Nicias over Alcibi-ades, the naïve Athenians sided with morality over compe-tence. In Thucydides’ assessment, the factional squabbling caused the Sicilian expedition to end in disaster for Athens (cf. 2.65.11 and 6.15.4). In Federalist #10, the most famous of the Federal-ist Papers, James Madison took a page from Thucydides when he criticized democracies for their inability to control the violence of faction. Madison, of course, pre-ferred a republic. Thucydides did not mind republican rule so long as a voice in government was given to only

those who had a direct personal or financial investment in the nation. Rulers who di-

rectly benefit from their position have a personal stake in the well-being

of the state. Thus they have per-sonal incentive for the state to succeed (cf. 8.97).6 Many of America’s early founders agreed, and applied this prin-ciple by extending voting privi-leges only to those who owned land. This principle fell into dis-

favor during the Jacksonian era. These five principles about

nations (they are motivated by fear, honor and interest; they are

sovereign over their own affairs; they will appeal to force if not forced to peace by a greater power; the hege-mony of one nation over many others

brings order and peace; and that wise states align the personal interests

of ambitious and able

Thucydides believed would have brought success. After Pericles succumbed to the plague in 429 b.c. , various fac-tions fought to fill the void of leadership he left behind. It was the petty squabbling of these factions that caused Athens’ downfall (2.65). Thucydides believed that petty factions are the bane of democracy. To illustrate the ills of faction in a democracy, Thucy-dides uses prominent Athenians who came into leader-ship after Pericles. None of these successors possessed Pericles’ ability to exercise independent control over the Athenian people. Among them was Cleon, whom Thucydides describes as “a popular leader of the time and very powerful with the multitude”—which are negative attri-butes in Thucydides’ outlook (4.21.3; cf. 3.36.6). Another leader was the incompetent Nicias, whom the Athenians placed in leader-ship because he was nice and pious, in contrast to the highly capable Alcibiades. Alcibiades came under fire because his ostentatious personal habits offended the Athenian people. When Ni-cias attacked Alcibiades’ char-acter on this point, Alcibiades ad-mitted to being ambitious. But he was quick to add that the fame he sought for himself brought fame to Athens as well, and this benefited all Athenians (6.12.2, 4.16). This reason-ing reflects Thucydides’ own outlook. But Athens did not embrace this princi-ple, to her own destruction. Once the Sicilian expedition got underway, a faction of Alcibiades’ opponents implicated Alcibia-des in a scandal. Be-cause they loathed Alcibiades’ personal habits, the simple-minded Athenian people were duped. They recalled Al-cibiades from the expedition, though he was an outstand-ing military leader, and they kept the incapable but virtu-

Does personal morality matter in a leader? While lead-

ing the Athenian military expedition in Sicily, Alcibiades

was recalled to Athens after

being charged in a scandal. Rather

than returning, he defected to

the Spartans. The loss of his leader-

ship was a blow to the Athenians and contributed

to their calamitous defeat in Sicily.

leaders with the interests of the state) show up repeatedly in the speeches of Thucydides. Thucydides uses speeches as an effective tool to represent the motives behind per-sonal and state action. These principles are also evident in occasional editorial remarks that Thucydides offers. By studying these principles and how they played out in the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides believed that it is possible to discern the basis for the political maneuver-ings of any nation in practically any age. Thucydidean principles run afoul of just war theory that developed within the context of Christian culture in the Middle Ages. Early just war principles were articu-

lated by Cicero, and Augustine developed them within the context of Christian thought.

These principles were further re-fined in the Middle Ages, es-

pecially by Gratian in his Decretum, the basis for

church law, and by Thomas Aquinas

in the thirteenth century (Sum-

ma II.a.II.a.e. Q.40). There are various f o r m u l a -tions of just war prin-

ciples, but they basi-

cally include these: War may

be waged (1) only by a legitimate author-

ity, and (2) only to punish wrongdoers; (3) peace and righteous-

ness must be the goal of war; (4) use no more force than necessary to achieve that goal. Other just war principles address the treatment of prisoners and non-combatants, fighting on the Sabbath, and using certain types of weap-ons. Some of these principles have carried into mod-ern times and have taken on a secularized form in the Geneva and Hague conventions.

—Chris Schlect

The hoplite was the infantryman in ancient Greek war-fare. His armor was made of bronze up to half an inch thick, providing great protection from the blows of the enemy. The large and heavy hoplon, or shield, could be carried with one hand, allowing the other hand freedom to wield a spear or sword. While arranged in a tight formation called a phalanx, each hoplite’s shield protected not only himself but his neighbor on the left.

o m n i b u s i V8

The Peloponnesian War 9

that this attribute does not describe Thucydides’ ap-proach to the past.

2. Though Thucydides was Athenian, why did he be-lieve he could faithfully represent both sides of the war in his account?

3. How did Athens function as a democracy during the height of Pericles’ rule? How did it not?

4. Explain how Thucydides reasoned that democracy con-tributed to the failure of Athens’ expedition to Sicily.

5. Though World War II began in 1938 or ’39, the United States did not enter the war until December of 1941 following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Briefly explain the United States’ motives for entering World War II in terms of the Thucydidean motives of fear, honor and interest.

readinG assiGnmenT: The Peloponnesian War, Book 1.1–46

session ii: discussionThe Peloponnesian War, Book 1.1–46

A Question to Consider In book 1 Thucydides traces some of the events that led up to the Peloponnesian War. At points, participants in these events seem to take the coming of the war as some-thing almost predestined. In some of the Star Trek movies, there is an inevitable conflict scenario—the famous Ko-bayashi Maru Flight Simulator Test. In this test there is no possibility of victory. War and defeat are inevitable—or so everyone seems to think.8 Are events inevitable?

Discuss or list short answers to the following questions:

Text Analysis1. What caused the conflict between Corcyra and

Corinth to erupt?2. Why did the Epidamnians seek help from the

Corinthians?3. Why did the Corcyraean and Corinthian envoys end

up in Athens?4. What arguments did the Corcyraeans make to at-

tempt to win Athenian support?5. What arguments did the Corinthians make to en-

courage Athens to refuse support to Corcyra?6. What decision did the Athenians make? Why did

they make this decision?

For Further ReadingConnor, W. Robert. Thucydides. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1984.

Crane, Gregory. The Blinded Eye: Thucydides and the New Written Word. London: Rowman and Littlefield Publish-ers, Inc., 1996.

Crane, Gregory. Thucydides and the Ancient Simplicity: The Limits of Political Realism. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 1998.

Dewald, Carolyn. Thucydides’ War Narrative: A Structural Study. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press, 2006.

Forde, Steven. The Ambition to Rule: Alcibiades and the Politics of Imperialism in Thucydides. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1989.

Hornblower, Simon. A Commentary on Thucydides; Vol. I: Books I–III, and Vol. II: Books IV–V.24. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991 and 1996.

Hornblower, Simon. Thucydides. Baltimore, Md.: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987.

Kagan, Donald. The Peloponnesian War. New York: Viking, 2003.

Orwin, Clifford. The Humanity of Thucydides. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1994.

Rood, Timothy. Thucydides: Narrative and Explanation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Spielvogel, Jackson J. Western Civilization. Seventh Edition. Belmont, Calif.: Thomson Wadsworth, 2009. 73–78.

Veritas Press History Cards: New Testament, Greece and Rome. Lancaster, Pa.: Veritas Press. 14.

session i: Prelude

A Question to Consider How would you think Thucydides would react to this statement by Theodore Roosevelt? Roosevelt wrote, “War, like peace, is properly a means to an end—righteousness. Neither war nor peace is in itself righteous, and neither should be treated as of itself the end to be aimed at. Righ-teousness is the end.”7

From the General Information above, answer the following questions:1. What did Aristotle mean when he said that the state-

ments of history are “singulars”? Explain how it is

o m n i b u s i V1 0

session iii: sTudenT-led discussionThe Peloponnesian War, Book 1.47–117

A Question to Consider Is it ever wrong for a person or a country to act in its own best interest?

Students should read and consider the example ques-tions below that are connected to the Question to Consid-er above. Last session’s assignment was to prepare three questions and answers for the Text Analysis section and two additional questions and answers for both the Cul-tural and Biblical Analysis sections below.

Text Analysis Example: How did the Athenians justify the accumula-tion of power and the creation of their empire?

Answer: They did not apologize for it. On the contrary, they claimed they were simply acting in their own inter-est. They reminded the Spartans that everyone would hate them too if they had had the good fortune to have built an empire. They argued that they had been more gentle and considerate of others than they had had to be. In sum-mary, they claimed it is only natural to act in one’s own best interest and that is all they have done (1.72–78).

Cultural AnalysisExample: Where do we see people acting in their own in-terest in our society today? Is this often wrong? When is it wrong?

Answer: We see this everywhere. We can note that it oc-curs in business—one businessman tries to sell more widgets than his competitor by selling for less. Custom-ers shop ceaselessly for widgets, plasma screen TVs, and candy bars, trying to find the best deal, because keeping their money is in their own best interest. We see this in politics where speakers carefully measure their words to try to communicate their message without offending any voters, because they wish to be re-elected. Often acting in one’s own interest is fine so long as it is done within the

Cultural Analysis1. Where do you see examples in our culture of con-

flicts that are deemed inevitable?2. How does our culture view genetics as an inevitable

cause of actions?

Biblical Analysis1. What was the string of events that led Cain to kill

Abel? Do these events exonerate Cain (Gen. 3)?2. Do pagans have an excuse for the sins that they com-

mit? Why not, if they have never heard someone preach the gospel (Rom. 1:18–22, Acts 17:30)?

3. Was the crucifixion an inevitable event? Does God’s hand in the event exonerate those who crucified Him (Acts 2:22–23)?

summa Write an essay or discuss this question, integrating

what you have learned from the material above. Does understanding that God is sovereign over

all events make them easier to bear?

The next session will be a student-led discussion. Students will be creating their own questions concerning the issue of the session. Students should create three Text Analysis Questions, two Cultural Analysis questions, and two Biblical Analysis questions. For more detailed instruc-tions, please see the chapter on the Iliad, Session III.

Issue Acting in one’s own best interest

readinG assiGnmenT: The Peloponnesian War, Book 1.47–117

Thucydides believed naval power was a key factor in Athenian dominance in the Aegean Sea. He himself had commanded a squadron of triremes. These light but strong ships were used for ramming enemy ships with their reinforced prows. Their name (trieres, “three-

fitted”) comes from the three levels of rowers who powered and maneuvered the ship.

The Peloponnesian War 1 1

session iV: reciTaTionThe Peloponnesian War, Book 1.1–146

Comprehension QuestionsAnswer the following questions for factual recall:1. What caused the Greeks to colonize? 2. Who was the first city-state to develop the trireme? 3. What was the cause of the Peloponnesian War ac-

cording to Thucydides? 4. What started the strife between Corcyra and

Corinth? 5. Which side—the Athenians/Corcyraeans or the Cor-

inthians—erected trophies and celebrated victory at Leukimme?

6. What did Athens tell the Potidaeans they must do? 7. What arguments did the Corinthian envoys use to

convince the Spartans to defend Potidaea? 8. What did King Archidamus of Sparta wonder con-

cerning the conflict with Athens? 9. Why did Themistocles go to Sparta to discuss the Spar-

tan demand that Athens not rebuild their city wall? 10. When the Helots revolted against their Spartan masters,

what did the Athenians do? What became of this? 11. What are “The Long Walls?” 12. Whom did the exiled Themistocles end up serving? 13. What did Pericles recommend concerning the Spartan

pressure on Athens to rescind the Megarian Decree?

readinG assiGnmenT: The Peloponnesian War, Book 2.34–65, 71–85 and Book 3.1–21

session V: WriTinG

Speech for the NationThe Peloponnesian War, Book 2.34–65 This session is a writing assignment. Remember, quality counts more than quantity. You should write no more than 1,000 words, either typing or writing legibly on one side of a sheet of paper. You will lose points for writ-ing more than this. You will be allowed to turn in your writing three times. The first and second times you turn it in, your teacher will grade it by editing your work. This is done by marking problem areas and making suggestions for improvement. You should take these suggestions into consideration as you revise your assignment. Only the grade on your final submission will be recorded. Your

confines of God’s commandments. If we look at the world as He does and see our best interest in light of His per-spective, we can see that our best interest and righteous-ness will always coincide. Seeing this, however, is often difficult. One large problem that has prevailed since the Enlightenment is that we tend to see the world (and reck-on our interests) individually rather than covenantally. Other cultural issues to consider: Capitalism v. social-ism, supply and demand, pre-nuptial agreements (which are not in one’s best interest) and focus groups.

Biblical AnalysisExample: In Proverbs 22:7, it says that the “borrower is slave of the lender.” If we want to be humble and avoid “acting selfishly in our own interest,” should we then be-come the borrower?

Answer: This is not what the Scripture is trying to con-vey. It recognizes that debt can turn the borrower into a slave. While the Scriptures recognize that sometimes we can not avoid debt and slavery, it recommends that we avoid debt-slavery and commends savings, hard work, and frugality. The Bible expects us to act shrewdly with the resources that we are given. It commends reasonable risk so that we can make a profit and use that profit to further serve God. Remember, all that we have belongs to the Lord—not just the tithe. He gives to us that we might give to others. Other Scriptures to consider: Genesis 12:1–3; Prov-erbs 14:1; Hebrews 12:2.

summa Write an essay or discuss this question, integrating

what you have learned from the material above. With so many people shouting so many ideas

today, how can we determine our best interest?

readinG assiGnmenT: The Peloponnesian War, Book 1.118–146

o m n i b u s i V1 2

results of revolution? Particularly, how does revolu-tion affect the meaning of words, the perception of masculinity, promises and oaths, and nobility?

8. What motive drives the destructive forces of revolution?

Cultural Analysis1. Where do you see a lust for power in our political

culture?2. Where do you see greed at work in our culture—par-

ticularly in people using force to take property from their enemies?

Biblical Analysis1. Does Adam’s rebellion against God count as a revolu-

tion (Gen. 3)?2. Why did the people rebel against God’s leadership and

demand a king “like the other nations” (1 Sam. 8)?

summa Write an essay or discuss this question, integrating

what you have learned from the material above. How can we oppose the forces of revolution in

our days? When should we become the forces of revolution?

The next session will be a student-led discussion. Students will be creating their own questions concerning the issue of the session. Students should create three Text Analysis Questions, two Cultural Analysis questions, and two Biblical Analysis questions. For more detailed instruc-tions, please see the chapter on the Iliad, Session III.

IssueHow the strong should treat the weak

readinG assiGnmenT: The Peloponnesian War, Book 4.1–41 and Book 5.84–116

session Vii: sTudenT-led discussion

A Question to Consider How should strong groups of people treat weak groups of people?

grade will be based on the following criteria: 25 points for grammar, 25 points for content accuracy—historical, theological, etc.; 25 points for logic—does this make sense and is it structured well?; 25 points for rhetoric—is it a joy to read?

Your objective is to imagine yourself as the leader of your country or the speech writer for the President. Imag-ine that your country is at war and that you are speaking at the memorial service for a number of fallen soldiers. Write a speech imitating Pericles’ Funeral Oration.

Optional Activity Watch another interesting example of a speech in-spired by Pericles’ Funeral Oration in the movie City Hall starring Al Pacino. Pacino plays the mayor, and he is eu-logizing a child killed by gang violence. Note, however, the similarities and differences between what Pericles and Pacino say in their speeches. Both are talking about the state and virtues and problems of their cities. You can watch the speech online.9

readinG assiGnmenT: The Peloponnesian War, Book 3.22–85

session Vi: discussion

A Question to Consider When is revolution (the overthrow of an established government) justified?

Discuss or list short answers to the following questions:

Text Analysis1. After the Athenians put down the revolution in Mytilene,

Cleon and Diodotus argued for very different treatment of the rebels. For what did they each argue?

2. What did the Athenians decide concerning Mytilene?3. When the Plataeans surrendered to the Spartan siege,

what did they hope to receive from Sparta? What did the Thebans want for the Plataeans?

4. What did the Spartans decide concerning Plataea?5. What did the Corcyraean oligarchs do in the summer

of 427 b.c. ?6. How did the Peloponnesians and the Athenians

again become involved in Corcyra’s politics?7. In book 3.82–85, how does Thucydides describe the

The Peloponnesian War 1 3

summa Write an essay or discuss this question, integrating

what you have learned from the material above. How should we as believers treat those weaker

than us? How should we act when we are weak-er and others are stronger?

readinG assiGnmenT: The Peloponnesian War, Book 6.1–72

session Viii: reciTaTionThe Peloponnesian War, Book 2.34–6.72

Comprehension QuestionsAnswer the following questions for factual recall:1. In the Funeral Oration what did Pericles say that Ath-

ens was for Helles and what it was worthy to do? 2. In the Funeral Oration what did Pericles say should

be done by widows, and what did he say would be done for the children of the dead soldiers?

3. Each year an army from the Peloponnesus invaded Athenian territory, burning crops and homes. What did Pericles say about this?

4. When the Peloponnesians attacked Plataea, what did the Athenians ask the Plataeans to do?

5. Why did the Mytilenians join with the Athenians—and what did they say was not the reason they joined them?

6. What happened when the Spartan, Salaethus, armed the common people of Mytilene?

7. On what point of debate did Cleon and Diodotus disagree?

8. What did the Spartans and Thebans do to Plataea when they surrendered?

9. When the Athenians had the upper hand at Pylos, Spartan envoys offered terms of peace to Athens. How did the Athenians react to these terms?

10. What tactic did Demosthenes use to defeat the Spartan forces on Sphacteria? What was he trying to avoid?

11. What was the outcome of the Athenian siege of Melos? 12. Why was Alcibiades recalled from Sicily and con-

demned to death in absentia by Athens?

Tomorrow’s session will be a Current Events session. Your assignment will be to find a story online, in a maga-zine, or in the newspaper that relates to the issue that you discussed today. Your task is to locate the article, give a copy of the article to your teacher or parent and provide some of your own worldview analysis to the article. Your

Students should read and consider the example ques-tions below that are connected to the Question to Consid-er above. Last session’s assignment was to prepare three questions and answers for the Text Analysis section and two additional questions and answers for both the Cul-tural and Biblical Analysis sections below.

Text Analysis Example: What does Thucydides think of the fact that Athenians treated the Melians based on the principle that the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must?

Answer: Thucydides thinks this is simply the way the world works. His observations have a lot of history be-hind them. Strong nations tend to do what they want to do and then figure out ways to justify their actions after they have accomplished their objectives (5.89).

Cultural AnalysisExample: In our culture where do we see the weak suffer-ing at the hands of the powerful?

Answer: We see this in many places. It is typical of what happens when political divisions occur within a society. It also occurs often in wars. When stronger forces meet weaker ones, they typically have their way with them—even if the results are atrocious. We also see this sort of oppression financially when people are trapped in debt. Other cultural issues to consider: Abortion and eu-thanasia, families trapped by gang violence, war.

Biblical AnalysisExample: In 1 Samuel 11, Nahash the Ammonite be-sieged God’s people at Jabesh Gilead. What were Na-hash’s terms for a treaty? Why did the people consider complying? How were they spared?

Answer: His terms were that he would only make a treaty with them and break the siege if he were allowed to put out the right eye—the eye used by the archers of Israel—of all the men in Jabesh Gilead. This would both neutral-ize the men of Jabesh Gilead as a fighting force and “bring disgrace on all Israel.” The men of Jabesh Gilead consid-ered taking these terms because otherwise he might kill all of them simply by keeping up the siege and starving them to death. They, like Thucydides, realized the weak often have to suffer terrible injustice. God, however, sent Saul to break the siege and rescue Jabesh Gilead. Other Scriptures to consider: Exodus 1, Exodus 20:8–11, Matt. 23:14, James 1:27, Romans 5:8, Romans 14, Proverbs 13:23.

o m n i b u s i V1 4

IssuePersonal life affecting national politics

Current events sessions are meant to challenge you to connect what you are learning in Omnibus class to what is happening in the world around you today. After the last session, your assignment was to find a story online or in a magazine or newspaper relating to the issue above. Today you will share your article and your analysis with your teacher and classmates or parents and family. Your analysis should follow the format below:

B r i e f i n t r o d u c t o r y P a r a g r a P h In this paragraph you will tell your classmates about the article that you found. Be sure to include where you found your article, who the author of your article is, and what your article is about. This brief paragraph of your presentation should begin like this:

Hello, I am (name), and my current events article is (name of the article) which I found in (name of the web or published source) . . .

c o n n e c t i o n P a r a g r a P h In this paragraph you must demonstrate how your article is connected to the issue that you are studying. This paragraph should be short, and it should focus on clearly showing the connection between the book that you are reading and the current events article that you have found. This paragraph should begin with a sen-tence like

I knew that my article was linked to our issue be-cause . . .

c h r i s t i a n W o r l d v i e W a n a l y s i s In this section, you need to tell us how we should respond as believers to this issue today. This response should focus both on our thinking and on practical ac-tions that we should take in light of this issue. As you list these steps, you should also tell us why we should think and act in the ways you recommend. This paragraph should begin with a sentence like

As believers, we should think and act in the fol-lowing ways in light of this issue and this article.

readinG assiGnmenT: The Peloponnesian War, Book 7.20–87

analysis should demonstrate that you understand the issue, that you can clearly connect the story you found to the issue that you discussed today, and that you can provide a biblical critique of this issue in today’s context. Look at the next session to see the three-part format that you should follow.

Issue Personal life affecting national politics

readinG assiGnmenT: The Peloponnesian War, Book 6.73–Book 7.19

session Xi: currenT eVenTs

In The Peloponnesian War, we meet a number of lead-ers. Some of them are good leaders, others are failures. One leader, Alcibiades, stands out because he works for both the Athenian and Spartan side. He is young, brash, exces-sive, and proud. He is also able, but his flamboyant life-style earns him many enemies who believe that he wants to overthrow democracy and introduce oligarchy or tyr-anny to Athens. He recognizes this fact, but simply claims that his arrogant attitude comes from his own excellence. Basically, he says, his pride is part of the package. This, of course, alienates and aggravates many Athenians, who hatch a plan to humiliate the proud Alcibiades. They use a case of vandalism to trump up charges of blasphemy against him. They delay the trial and stir up public sen-timent against him before he returns to Athens, leaving the Sicilian Expedition in the hands of Nicias, who has few enemies but is not the caliber of general that Alcibi-ades is. Eventually, Alcibiades flees to the Spartan side and helps them understand how to defeat Athens by making them fight wars on two fronts, Syracuse and At-tica. Thucydides recognizes Alcibiades’ abilities and sees the ruin of Athens in Alcibiades’ excesses, saying, “. . . and although in his public life his conduct of the war was as good as could be desired, in his private life his habits gave offense to everyone, and caused them to commit affairs to other hands, and thus before long to ruin the city.” All too often today,leaders want to divorce private and public life. This, however, can not be done. Our private lives af-fect the trust that people have in us.

The Peloponnesian War 1 5

oPTional session a: acTiViTy

The Democracy Game Athenian democracy was a model for future repub-lics like America. We might have warm feelings in our hearts when we hear words like “democracy.” Many phi-losophers down through the ages, however, have been ter-rified of it. Democracy in Athens was a dangerous game for some who used the state for their own personal gain. (Of course, this could not happen in America, right? Seri-ously, democracies can be swayed by demagogues. Con-stitutional republics, like America, have protections—like hopefully having wise representatives—but we could and sadly do see the American Republic being swayed by demagogues in our day.) Often, politicians had a deep personal stake in the decisions that the government was making. Alcibiades longed for fame and fortune, thereby burning through the trust of many. Today, we are going to do an experiment that will help us understand the dangers of democracy when peo-ple use the state for their own personal gain; to make it fun and to sharpen our persuasive abilities, we are going to play for some rewards. Choose at least two, but preferably three, people as speakers. Each speaker will be given a Position and Re-ward Slip—see Rule #1 below. (These slips can be found in the Teacher’s Edition. Print out the page containing them, cut out each slip, and distribute one to each speak-er randomly.) If you are playing this game at home, you may limit the speakers to two. Parents and siblings are welcome to play. There should be at least one person in the audience. The audience will decide which position they will support after hearing the speeches. One person must be designated as the G.O.C. (Guardian of the Candy) and must, in fact, actually guard it until the game is over. This should be a teacher or parent if at all possible. The winning proposition will be the one with the most votes in the election. To begin this activity the G.O.C. is given a candy bar for each participant and one dollar is given to each participant. (If you have time and resources, play more than once with different speakers).

r u l e s

1. Each of the speakers has received a Position and Reward Slip. It tells them the position they must per-suade the audience to support and what reward they (and possibly the audience) are to receive if they suc-cessfully get the most votes for their position.

2. All participants have been given one dollar. At the end of the game you might be allowed to keep it, or make a

session X: discussionThe Peloponnesian War, Book 6.1–7.87

A Question to Consider How does a person or a country turn a defeat into a ruinous calamity like the Sicilian Expedition?

Discuss or list short answers to the following questions:

Text Analysis1. How did Nicias try to convince the Athenians to re-

consider their decision concerning the invasion of Sicily? What did his argument do?

2. Who was chosen to lead the expedition? Why was one of them recalled? Why?

3. How did Nicias display his indecisiveness after Gylip-pus’ arrival?

4. Why did the Spartans fortify Decelea? What effect did this have on the Athenians?

5. What was the structural advantage of the new Corin-thian triremes?

6. On what strategic steps did Demosthenes and Nicias disagree? What sorts of things were convincing Ni-cias that he was correct?

7. How did the different sides seek to motivate their fighters before the final battle?

8. What was the outcome of the Sicilian Expedition?

Cultural Analysis1. Where do you see short-sighted or wrong-headed ac-

tions being taken by governments today?2. Where do you see leaders avoiding hard decisions in

order to curry the favor of the people?3. Where do you see pride at work in the leadership of

our culture?

Biblical Analysis1. How did Rabshakeh’s arrogance lead to a disaster for

the Assyrians? How did Hezekiah’s humility save his people (2 Kings 18:9–19:37)?

2. How did Hezekiah’s pride lead to disaster (2 Kings 20:12–19)?

summa Write an essay or discuss this question, integrating

what you have learned from the material above. How can we help our nation avoid disasters like

the Sicilian Expedition?

o m n i b u s i V1 6

questions and answers for the Text Analysis section and two additional questions and answers for both the Cul-tural and Biblical Analysis sections below.

Text Analysis Example: In 1.23 Thucydides says that the cause of the Peloponnesian War was Sparta’s fear of growing Athe-nian power. Should the Spartans have feared the growth of Athenian power?

Answer: Yes, they should have. The Athenians consis-tently proved that they wielded power unapologetically in their own interest. This interest might mean the total destruction of another city. When a group of people say that “the strong will do what they can and the weak will suffer what they must,” it makes those who are seeking to keep their own freedom nervous. The Athenians contin-ued to act arrogantly throughout the war. They wiped out Melos. They started a new war in Syracuse. They rejected generous peace terms on the part of Sparta.

Cultural AnalysisExample: Where are the forces of empire loose in our world today?

Answer: Since the end of World War II—and especially since the end of the Cold War—America has held a sort of hegemony over the nations of Europe and over the rest of the world. Our temptation is to act increasingly like an empire—rather than being a republic. Today, we are tempted to insert ourselves into many conflicts across the globe. Our interests are broad. America must carefully consider its place in the world and whether we should continue on the path of empire or look more to be the republic that our Founders envisioned. Other cultural issues to consider: U.S. aid for foreign countries, peacekeeping, international treaties, interna-tionalism, American Empire.

Biblical AnalysisExample: What form of government did ancient Israel have? Does this tell us anything about God’s perspective on empires (singular or narrow freedom) or confedera-cies (freedom being spread more broadly)?

Answer: Israel was much more confederacy than empire. For most of the history of the nation, the leadership of each tribe was critical to the functioning of the state. El-ders, since the time of Moses, were the functional local government of Israel. During the reign of Solomon, Israel became more centralized. After Solomon, however, Re-

purchase with it, depending on the outcome of the vote and the reward on the winning speaker’s slip.

3. Each speaker will have two chances to speak.4. The speakers will present their speeches in turn. Dur-

ing the second round of speeches they will speak in reverse order.

5. Each speech will be limited to two minutes.6. After all the speeches are completed there will be a

short time for questions and answers.7. Speakers should vote, but they may not vote for their

own proposal. 8. Speakers may not reveal what the reward is or any-

thing about the reward promised on their slip.9. After the speeches hold the election to determine the

winning speaker. If there is a tie, hold a run-off elec-tion between those speakers only.

10. When the game is over, each speaker reads the re-ward on his slip. Follow the instructions for the win-ner’s reward.

t h e Q u e s t i o n

Should participants in this game receive a candy bar?

Consider the following questions after the game is over:1. What types of arguments were persuasive? (Did

people argue emotionally or rationally? Did they twist people’s arms to try to get their votes?)

2. Did personal interest corrupt the process?3. Was the interest of the entire group served by the

final decision or not?

oPTional session b: sTudenT-led discussionThe Peloponnesian War

A Question to Consider In The Peloponnesian War, we see a battle between the Athenian empire and the forces led by Sparta. Athens was a democracy, but she ruled her empire as though it were made up of slaves. Sparta was an oligarchy, but for many Greek city-states Spartan victory meant freedom from Athenian oppression. Which then is better: an em-pire (if you can have it) or a confederacy where one party does not have to submit to the other?

Students should read and consider the example ques-tions below that are connected to the Question to Consid-er above. Last session’s assignment was to prepare three

The Peloponnesian War 1 7

2 Plutarch, Life of Pericles VI.3 “Feb. 27, 1947,” Time (10 March 1947).4 See Alexander Kemos, “The Influence of Thucydides in the

Modern World,” Point of Reference: A Journal of Hellenic Thought and Culture (Harvard University, Fall 1994), available at http://www.hri.org/por/thucydides.html; also Dennis Ross, Statecraft: And How to Restore America’s Standing in the World (Union Square West, NY: Ferrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007). Ross does not mention Thucydides, but his outlook is laden with Thucydidean practicality.

5 See Xenophon’s Hellenica I–III.6 Thucydides praised the rule of the 5,000 that Athens instituted

in 411 b.c. (8.97.2). Aristotle informs us that an important fea-ture of this government was that members of the 5,000 needed to have a personal or financial stake in Athens. “The whole of the rest of the administration was to be committed, for the pe-riod of the war, to those Athenians who were most capable of serving the state personally or financially, to the number of not less than five thousand” (Athenian Constitution, 30).

7 Theodore Roosevelt, Fear God and Take Your Own Part. (New York: George H. Doran Co., 1916), 66.

8 Film clips concerning the infamous the Kobayashi Maru Flight Simulator Test (the test where victory was impossible) from var-ious Star Trek movies both old and new can be found through Links 1 and 2 for this chapter at www.VeritasPress.com/Om-niLinks.

9 Watching the scene online is best because the movie was not memorable and has some vulgar language and violence. A video of this speech is available through Link 3 for this chapter at www.VeritasPress.com/OmniLinks.

hoboam was asked to decrease the control of the central government. Sadly, he rejected the wise counsel of the older men and tried to increase the centralized control (and worked the people like slaves). This rejection of wise advice led to the schism between the northern tribes, Is-rael, and the southern tribes, Judah. God, however, makes it clear that His people can thrive under the rule of many different kinds of governments. Still, governments, if they wish to please God, need to be servants of their people, protecting their freedom and liberty to serve Him and do what is righteous. Other Scriptures to consider: Deuteronomy 17:14ff, 1 Samuel 8, Jeremiah 29:7, Isaiah 9:6–7, Revelation 11:15.

summa Write an essay or discuss this question, integrating

what you have learned from the material above. As we have influence over our government, what

type of government should we desire, hope for, and work to have?

e n d n o t e s1 Lucian, “The Way to Write History” 42, in The Works of Lucian,

trans. H.W. Fowler and F.G. Fowler, four volumes (Oxford Uni-versity Press, 1905), vol. 2, 129.