Sylvia Plath - Poetry

-

Upload

miki-kreker -

Category

Documents

-

view

23 -

download

3

description

Transcript of Sylvia Plath - Poetry

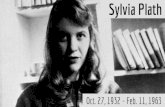

Biography of Sylvia Plath

Sylvia Plath (1932 - 1963)

Sylvia started her life in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts on October 27, 1932. During her early childhood, Sylvia's father Otto suffered from a lengthy illness. Otto, certain he had cancer, did not seek treatment initially. When he finally did see a doctor, a case of diabetes was diagnosed but by that time his illness was advanced. His end was fraught with suffering which included the amputation of a leg. Reference to the leg is made in "Daddy" Otto died just days past Sylvia's 8th birthday.

Sylvia was an excellent student and in 1950 she was accepted into Smith College on a scholarship. She was at the top of her class and should logically have been very happy. That was not the case. She lived in fear that it would be found out that she wasn't the perfectly happy person she tried to project. In 1952 she won the first prize of $500 from Mademoiselle magazine for her short story "Sunday at the Minton’s". The

following June 1953, Sylvia was a guest editor at the Mademoiselle New York offices, which she later wrote about in The Bell Jar. She came home from New York in a state of exhaustion and depression. She was counting on being accepted into Frank O'Connor's creative writing course at Harvard and when she wasn't, she went into a state of withdrawal. She was distraught, scared inside, unable to sleep or function, but still determined to show the world a brave face. On August 24th, unable to carry on any longer, she attempted suicide. For the next months she was institutionalised at Maclean Hospital and was treated with insulin therapy and shock treatments. During this period of hospitalisation, Sylvia unknowingly was collecting material for her novel The Bell Jar and short story "Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams".

In October 1955, Sylvia attended Newnham College at Cambridge University on a Fulbright scholarship. After a series of go nowhere relationships and numerous blind dates, Sylvia met Ted Hughes at a St. Botolph's party on February 25, 1956. They were married on a rainy day in London on June 16th of the same year and honeymooned in Benidorm, Spain. Ted Hughes describes the details of their wedding beautifully in his poem "A Pink Wool Knitted Dress" in Birthday Letters.

After the conclusion of her studies at Cambridge in the spring of 1957, Sylvia was asked to teach English at Smith College, where she had taken her undergraduate studies. Sylvia returned to America, bringing her husband with her. Her mother, Aurelia Plath, made them a present of a vacation on Cape Cod. Sylvia was excited at the prospect of teaching English, an obvious favorite subject area. She wasn't long on the faculty when she felt overwhelmed. She chastised herself for presuming that she could teach. The preparatory work was exhausting and she perceived the faculty's coldness to her. She had dreamed of giving marvellous lectures and leisurely writing her book. As was her lot, she must be brilliant and make it look as "easy as pie". She was sick frequently and most unhappy. When the year was over, she did not return. The College was very satisfied with Sylvia's performance, but Sylvia felt she had failed and she wouldn't go back for another year. Already Sylvia was beginning to have doubts about Ted's love for her. She needed constantly to be reassured. Sylvia took a less taxing clerical position as a receptionist in the psychiatric clinic of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and continued with her writing. In early December of 1958 she began to secretly see Ruth Boucher, her therapist from McLean, where she had been hospitalized after her earlier suicide attempt in the summer of 1953. She also attended an evening poetry class, which was given by Robert Lowell, whose confessional style influenced Sylvia’s poetry.

In December 1959 Sylvia and Ted returned to England. Sylvia was pregnant and due to give birth in the spring of 1960. On April 1st, Frieda Rebecca was born. During her pregnancy, on February 10th, Sylvia signed a contract with William Heinemann Ltd. to publish The Colossus, which was to come out in October 1960. Outwardly Sylvia showed amazing energy. She scoured and scrubbed their London flat, wanting a pretty home for herself, her husband and their yet to be born baby. Inwardly she felt exhausted and barely able to carry on, but unwilling to let the world know and her circumstances pressed in on her. She wanted everything, and the writing was her outlet and her curse. It was both her salvation and her undoing.

The following February 1961 a miscarriage left Sylvia feeling depressed. She wrote of it in a poem "Parliament Hill Fields".

In August 1961 the Hughes family moved to a Devon farm and Sylvia was isolated. Ted had become more removed from her. A son Nicholas Farrar was born on January 17th, 1962. In July, Sylvia discovered Ted's affair with Assia Wevill. Sylvia and Ted separated in September. In the following month Sylvia wrote at least 26 of the Ariel poems.

In December 1962, Sylvia took the children with her to London and moved into an apartment at 23 Fitzroy Road, which was the former home of poet William Butler Yeats. The Bell Jar was published under the pseudonym of Victoria Lucas in January 1963. On February 11, 1963 Sylvia gave up her life.

Concluding remarks Although Sylvia Plath's life was brief in conventional terms, her life was rich in experiences. She received accolades in the form of prizes, awards, and scholarships. She had literary successes, although none so great as those that were endowed on her post-humously. In 1982 she received the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry for her Collected Poems.

Sylvia Plath was many things to many people; she was daughter, sister, student and teacher, wife and mother, and finally a writer. In death, she continues to influence people for more than her literary excellence.

She was a bright, intelligent, and determined young woman with a need to succeed and a burning desire to write. Sylvia had other needs that clashed with her literary ambitions. She dreamed of the comfort of a home of her own where she could belong and be loved for herself. She wanted a good husband and children. In school and outside of it, she was a high achiever never being able to quite reach the very high expectations she set for herself. No one was able to drive Sylvia more than herself. She knew self-doubt and depression. Yet to the world she presented a carefree, it's so easy attitude. In reality she worked, pushing herself relentlessly, whether in her studies, her teaching, in her relationships or her writing. Only those nearest to her knew how troubled Sylvia's life was.

Biography by: This biography was written by Joan Welz of the University of Alberta, as part of a Master's Degree in Library and Information Studies.

Sylvia Plath - A Better ResurrectionI have no wit, I have no words, no tears;My heart within me like a stoneIs numbed too much for hopes or fears;Look right, look left, I dwell alone;A lift mine eyes, but dimmed with griefNo everlasting hills I see;My life is like the falling leaf;O Jesus, quicken me.

Sylvia Plath - A Birthday PresentWhat is this, behind this veil, is it ugly, is it beautiful?It is shimmering, has it breasts, has it edges?

I am sure it is unique, I am sure it is what I want.When I am quiet at my cooking I feel it looking, I feel it thinking

'Is this the one I am too appear for,Is this the elect one, the one with black eye-pits and a scar?

Measuring the flour, cutting off the surplus,Adhering to rules, to rules, to rules.

Is this the one for the annunciation?My god, what a laugh!'

But it shimmers, it does not stop, and I think it wants me.I would not mind if it were bones, or a pearl button.

I do not want much of a present, anyway, this year.After all I am alive only by accident.

I would have killed myself gladly that time any possible way.Now there are these veils, shimmering like curtains,

The diaphanous satins of a January windowWhite as babies' bedding and glittering with dead breath. O ivory!

It must be a tusk there, a ghost column.Can you not see I do not mind what it is.

Can you not give it to me?Do not be ashamed--I do not mind if it is small.

Do not be mean, I am ready for enormity.Let us sit down to it, one on either side, admiring the gleam,

The glaze, the mirrory variety of it.Let us eat our last supper at it, like a hospital plate.

I know why you will not give it to me,

You are terrified

The world will go up in a shriek, and your head with it,Bossed, brazen, an antique shield,

A marvel to your great-grandchildren.Do not be afraid, it is not so.

I will only take it and go aside quietly.You will not even hear me opening it, no paper crackle,

No falling ribbons, no scream at the end.I do not think you credit me with this discretion.

If you only knew how the veils were killing my days.To you they are only transparencies, clear air.

But my god, the clouds are like cotton.Armies of them. They are carbon monoxide.

Sweetly, sweetly I breathe in,Filling my veins with invisibles, with the million

Probable motes that tick the years off my life.You are silver-suited for the occasion. O adding machine-----

Is it impossible for you to let something go and have it go whole?Must you stamp each piece purple,

Must you kill what you can?There is one thing I want today, and only you can give it to me.

It stands at my window, big as the sky.It breathes from my sheets, the cold dead center

Where split lives congeal and stiffen to history.Let it not come by the mail, finger by finger.

Let it not come by word of mouth, I should be sixtyBy the time the whole of it was delivered, and to numb to use it.

Only let down the veil, the veil, the veil.If it were death

I would admire the deep gravity of it, its timeless eyes.I would know you were serious.

There would be a nobility then, there would be a birthday.And the knife not carve, but enter

Pure and clean as the cry of a baby,And the universe slide from my side.

Sylvia Plath - A Lesson In VengeanceIn the dour agesOf drafty cells and draftier castles,Of dragons breathing without the frame of fables,Saint and king unfisted obstruction's knucklesBy no miracle or majestic means,

But by such abusesAs smack of spite and the overscrupulousTwisting of thumbscrews: one soul tied in sinews,One white horse drowned, and all the unconquered pinnaclesOf God's city and Babylon's

Must wait, while here Suso'sHand hones his tack and needles,Scouraging to sores his own red sluicesFor the relish of heaven, relentless, dousing with pricklesOf horsehair and lice his horny loins;

While there irate CyrusSquanders a summer and the brawn of his heroesTo rebuke the horse-swallowing River Gyndes:He split it into three hundred and sixty tricklesA girl could wade without wetting her shins.

Still, latter-day sages,Smiling at this behavior, subjugating their enemiesNeatly, nicely, by disbelief or bridges,Never grip, as the grandsires did, that devil who chucklesFrom grain of the marrow and the river-bed grains.

Sylvia Plath - A LifeTouch it: it won't shrink like an eyeball,This egg-shaped bailiwick, clear as a tear.Here's yesterday, last year ---Palm-spear and lily distinct as flora in the vastWindless threadwork of a tapestry.

Flick the glass with your fingernail:It will ping like a Chinese chime in the slightest air stirThough nobody in there looks up or bothers to answer.The inhabitants are light as cork,Every one of them permanently busy.

At their feet, the sea waves bow in single file.Never trespassing in bad temper:Stalling in midair, Short-reined, pawing like paradeground horses.Overhead, the clouds sit tasseled and fancy

As Victorian cushions. This familyOf valentine faces might please a collector:They ring true, like good china.

Elsewhere the landscape is more frank.The light falls without letup, blindingly.

A woman is dragging her shadow in a circleAbout a bald hospital saucer.It resembles the moon, or a sheet of blank paperAnd appears to have suffered a sort of private blitzkrieg.She lives quietly

With no attachments, like a foetus in a bottle,The obsolete house, the sea, flattened to a pictureShe has one too many dimensions to enter.Grief and anger, exorcised,Leave her alone now.

The future is a grey seagullTattling in its cat-voice of departure.Age and terror, like nurses, attend her,And a drowned man, complaining of the great cold,Crawls up out of the sea.

Sylvia Plath - April 18the slime of all my yesterdaysrots in the hollow of my skull

and if my stomach would contractbecause of some explicable phenomenonsuch as pregnancy or constipation

I would not remember you

or that because of sleepinfrequent as a moon of greencheesethat because of foodnourishing as violet leavesthat because of these

and in a few fatal yards of grassin a few spaces of sky and treetops

a future was lost yesterdayas easily and irretrievablyas a tennis ball at twilight

Sylvia Plath - Frog AutumnSummer grows old, cold-blooded mother. The insects are scant, skinny. In these palustral homes we only Croak and wither.

Mornings dissipate in somnolence. The sun brightens tardily Among the pithless reeds. Flies fail us. he fen sickens.

Frost drops even the spider. Clearly The genius of plenitude Houses himself elsewhwere. Our folk thin Lamentably.

Sylvia Plath - Getting ThereHow far is it?How far is it now?The gigantic gorilla interiorOf the wheels move, they appall me ---The terrible brainsOf Krupp, black muzzlesRevolving, the soundPunching out Absence! Like cannon.It is Russia I have to get across, it is some was or other.I am dragging my bodyQuietly through the straw of the boxcars.Now is the time for bribery.What do wheels eat, these wheelsFixed to their arcs like gods,The silver leash of the will ----Inexorable. And their pride!All the gods know destinations.I am a letter in this slot!I fly to a name, two eyes.Will there be fire, will there be bread?Here there is such mud. It is a trainstop, the nursesUndergoing the faucet water, its veils, veils in a nunnery,Touching their wounded,The men the blood still pumps forward,Legs, arms piled outsideThe tent of unending cries ----A hospital of dolls.And the men, what is left of the menPumped ahead by these pistons, this bloodInto the next mile,The next hour ----Dynasty of broken arrows!

How far is it?There is mud on my feet, Thick, red and slipping. It is Adam's side,This earth I rise from, and I in agony.I cannot undo myself, and the train is steaming.Steaming and breathing, its teethReady to roll, like a devil's.There is a minute at the end of itA minute, a dewdrop. How far is it?It is so smallThe place I am getting to, why are there these obstacles ----The body of this woman,Charred skirts and deathmaskMourned by religious figures, by garlanded children.And now detonations ----Thunder and guns.The fire's between us.Is there no placeTurning and turning in the middle air,Untouchable and untouchable.The train is dragging itself, it is screaming ----An animalInsane for the destination,The bloodspot,The face at the end of the flare.I shall bury the wounded like pupas,I shall count and bury the dead.Let their souls writhe in like dew,Incense in my track.The carriages rock, they are cradles.And I, stepping from this skinOf old bandages, boredoms, old faces

Step up to you from the black car of Lethe,Pure as a baby.

Sylvia Plath - JiltedMy thoughts are crabbed and sallow,My tears like vinegar,Or the bitter blinking yellowOf an acetic star.

Tonight the caustic wind, love,Gossips late and soon,And I wear the wry-faced pucker ofThe sour lemon moon.

While like an early summer plum,Puny, green, and tart,Droops upon its wizened stemMy lean, unripened heart.

Sylvia Plath - Leaving EarlyLady, your room is lousy with flowers.When you kick me out, that's what I'll remember,Me, sitting here bored as a loepardIn your jungle of wine-bottle lamps,Velvet pillows the color of blood puddingAnd the white china flying fish from Italy.I forget you, hearing the cut flowersSipping their liquids from assorted pots,Pitchers and Coronation gobletsLike Monday drunkards. The milky berriesBow down, a local constellation,Toward their admirers in the tabletop:Mobs of eyeballs looking up.

Are those petals of leaves you've paried with them ---Those green-striped ovals of silver tissue?The red geraniums I know.Friends, friends. They stink of armpitsAnd the invovled maladies of autumn,Musky as a lovebed the morning after.My nostrils prickle with nostalgia.Henna hags:cloth of your cloth.They tow old water thick as fog.

The roses in the Toby jugGave up the ghost last night. High time.Their yellow corsets were ready to split.You snored, and I heard the petals unlatch,Tapping and ticking like nervous fingers.You should have junked them before they died.Daybreak discovered the bureau lid Littered with Chinese hands. Now I'm stared atBy chrysanthemums the sizeOf Holofernes' head, dipped in the sameMagenta as this fubsy sofa.In the mirror their doubles back them up.Listen: your tenant miceAre rattling the cracker packets. Fine flourMuffles their bird feet: they whistle for joy.And you doze on, nose to the wall.This mizzle fits me like a sad jacket.How did we make it up to your attic?You handed me gin in a glass bud vase.We slept like stones. Lady, what am I doingWith a lung full of dust and a tongue of wood,Knee-deep in the cold swamped by flowers?

Sylvia Plath - Love Is A Parallax'Perspective betrays with its dichotomy:train tracks always meet, not here, but only in the impossible mind's eye;horizons beat a retreat as we embarkon sophist seas to overtake that mark where wave pretends to drench real sky.'

'Well then, if we agree, it is not oddthat one man's devil is another's god or that the solar spectrum isa multitude of shaded grays; suspenseon the quicksands of ambivalence is our life's whole nemesis.

So we could rave on, darling, you and I,until the stars tick out a lullaby about each cosmic pro and con;nothing changes, for all the blazing ofour drastic jargon, but clock hands that move implacably from twelve to one.

We raise our arguments like sitting ducksto knock them down with logic or with luck and contradict ourselves for fun;the waitress holds our coats and we put onthe raw wind like a scarf; love is a faun who insists his playmates run.

Now you, my intellectual leprechaun,would have me swallow the entire sun like an enormous oyster, downthe ocean in one gulp: you say a markof comet hara-kiri through the dark should inflame the sleeping town.

So kiss: the drunks upon the curb and damesin dubious doorways forget their monday names,

caper with candles in their heads;the leaves applaud, and santa claus flies inscattering candy from a zeppelin, playing his prodigal charades.

The moon leans down to took; the tilting fishin the rare river wink and laugh; we lavish blessings right and left and cryhello, and then hello again in deafchurchyard ears until the starlit stiff graves all carol in reply.

Now kiss again: till our strict father leansto call for curtain on our thousand scenes; brazen actors mock at him,multiply pink harlequins and singin gay ventriloquy from wing to wing while footlights flare and houselights dim.

Tell now, we taunq where black or white beginsand separate the flutes from violins: the algebra of absolutesexplodes in a kaleidoscope of shapesthat jar, while each polemic jackanapes joins his enemies' recruits.

The paradox is that 'the play's the thing':though prima donna pouts and critic stings, there burns throughout the line of words,the cultivated act, a fierce brief fusionwhich dreamers call real, and realists, illusion: an insight like the flight of birds:

Arrows that lacerate the sky, while knowingthe secret of their ecstasy's in going; some day, moving, one will drop,and, dropping, die, to trace a wound that healsonly to reopen as flesh congeals: cycling phoenix never stops.

So we shall walk barefoot on walnut shellsof withered worlds, and stamp out puny hells and heavens till the spirits squeaksurrender: to build our bed as high as jack'sbold beanstalk; lie and love till sharp scythe hacks away our rationed days and weeks.

Then jet the blue tent topple, stars rain down,and god or void appall us till we drown in our own tears: today we startto pay the piper with each breath, yet loveknows not of death nor calculus above the simple sum of heart plus heart.