SULFONAMIDE-RESISTANTdm5migu4zj3pb.cloudfront.net/manuscripts/101000/101490/JCI44101490.pdf ·...

Transcript of SULFONAMIDE-RESISTANTdm5migu4zj3pb.cloudfront.net/manuscripts/101000/101490/JCI44101490.pdf ·...

SULFONAMIDE-RESISTANTSTAPHYLOCOCCI: CORRELATIONOF IN VITRO SULFONAMIDE-RESISTANCEWITH

SULFONAMIDETHERAPY1

By WESLEYW. SPINK AND J. J. VIVINO(From the Division of Internal Medicine, University of Minnesota Hospials and Medical School,

Minneapolis)

(Received for publication September 20, 1943)

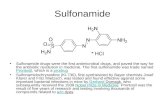

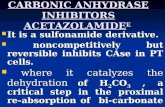

A feature of sulfonamide therapy for bacterialinfections is that species of bacteria differ intheir resistance to the antibacterial action of thecompounds. It is also recognized that strains ofmicroorganisms within the same species displayvariations in susceptibility. A disconcertingand confusing factor associated with chemo-therapy, which appears to be assuming increasingclinical significance, is the ease and frequencywith which some species of bacteria may developin vtro and in vivo resistance to the bacteriostaticaction of the sulfonamides. In the literature, theterm "sulfonamide-fast" has been applied tothose strains which become resistant to theantibacterial action of the compounds. This isparticularly applicable to studies involvingspecies of bacteria whose progenitors were knownto be sensitive to the sulfonamides. Because thedevelopment of resistance is a relative phenome-non, and because, under proper experimentalconditions, the growth of even the most resistantstrains of bacteria may be inhibited by the drugs,the term "sulfonamide-resistant" is believed tobe a more accurate description.

The purpose of this report is to review brieflythe problem of sulfonamide-resistant bacteria ingeneral, and to record the results of investiga-tions with several strains of staphylococcusisolated from patients. An attempt has beenmade to answer the following questions: If astandard in vitro test is used for quantitatingthe inhibitory effect of the sulfonamides uponthe growth of staphylococci, do strains of thisspecies vary in their susceptibility to the anti-staphylococcic action of the compounds? Isthere any correlation between the isolation ofsulfonamide-resistant strains of staphylococci

IAided by grants from the Committee on ScientificResearch, American Medical Association, and the CharlesP. DeLaittre Research Fund, University of MinnesotaMedical School.

from patients and previous sulfonamide therapycarried out in these patients? Is the develop-ment of strain resistance a permanent charac-teristic of the bacteria?

Several species of bacteria have been renderedresistant to the in vitro and in vivo action of thesulfonamides. Many of the investigations havebeen carried out with different strains of thepneumococcus (1 to 5). Sesler and Schmidt (6)observed the development of sulfonamide-re-sistant pneumococci, and concluded that strainsvary in developing this sulfonamide-resistance;that a given strain develops resistance to theseveral sulfonamides at different rates; that themore susceptible a parent strain is to the actionof a sulfonamide, the more difficult it is to developresistance; and that strains which become re-sistant to one sulfonamide, are resistant to allthe other compounds tested. There is evidencethat the development of sulfonamide-resistantpneumococci is more than a temporary phe-nomenon (7 to 9). On the other hand, sulfona-mide-resistant pneumococci are sensitive to theaction of specific antipneumococcus serum.Hemolytic streptococci, particularly Lancefieldgroup A strains, are usually quite susceptible tothe action of sulfanilamide, and yet strains inthis group may acquire in vitro and in vivo re-sistance to the drug (10, 11). While staphy-lococci as a species are more refractory to thebacteriostatic effect of all of the sulfonamidesthan are pneumococci and hemolytic streptococci,it has been demonstrated that strains of staphy-lococci may develop an increased resistance tothe compounds (12, 13). Gram-negative speciesof bacteria, whose growth is usually inhibitedin vitro by the sulfonamides, have been shownto develop sulfonamide-resistance. These in-clude E. coli (14, 15), B. abortus (16), meningo-cocci (17), and Shigella paradysentariae (strainsof Flexner and Sonne) (18). Strains of gono-

267

WESLEYW. SPINK AND J. J. VIVINO

cocci, a species which is highly susceptible to thebacteriostatic action of the sulfonamides, havebeen made resistant to sulfanilamide and sulfa-pyridine (19, 20). Carpenter and his associates(21) could not develop an increased tolerance of10 strains of gonococci to sulfathiazole over a

period of 3 months. Nevertheless, this has beenaccomplished by Kirby (22).

If invasive strains of microorganisms developresistance to the sulfonamides both in vitro andin experimental animals, the question immedi-ately arises as to whether such a phenomenonmay transpire in human subjects while they are

being treated with one of the sulfonamides, andwhether the development of sulfonamide-re-sistant strains will affect the ultimate recovery

of the patient. While caution must be exercisedin transposing quantitatively in vitro data or theresults of animal protection tests with the sul-fonamides to the problem of chemotherapy inhuman subjects, these data are often quitehelpful in directing the clinical application of thedrugs. Several investigators have confirmedthe observation that specific types of pneu-

mococci isolated from patients have shown an

initial sensitivity to a sulfonamide, but as

chemotherapy proceeded, subsequent isolation ofthe same type of pneumococcus revealed thedevelopment of sulfonamide-resistance (8, 23 to28). In some instances, coincident with thedetection of sulfonamide-resistant pneumococci,the patients' condition became worse or theyfailed to respond as anticipated. Similar ob-servations have been made with other species ofbacteria. Francis (29) encountered a group of13 individuals on a plastic surgery ward whoselesions were infected by a group A, type 12,strain of beta hemolytic streptococcus, and thelocal application of sulfanilamide was withouteffect. In vitro tests showed the organisms tobe resistant to sulfanilamide, although otherstrains of this type had been shown to be quitesensitive. It is of interest that the local appli-cation of gramicidin in one case eradicated theinfection. Strains of Brucella abortus, sensitiveto the in vitro action of sulfanilamide, have beenmade sulfanilamide-resistant by repeated ex-

posure of the organism to the drug. Green (30)reported that 2 individuals in a laboratorybecame infected with these sulfanilamide-resist-

ant strains. The patients finally recovered,although a strain isolated from the blood of oneof the victims was still resistant to sulfanilamide.It was observed by Cohn and his associates (31),in gonorrheal patients who did not respondfavorably to therapy with sulfathiazole, thatstrains of gonococci from these individuals fre-quently showed in vitro evidence of resistance tosulfathiazole. Similar observations have beenrecorded by Petro (32). Strains of staphylococcihave been shown to develop sulfonamide-resist-ance in patients undergoing therapy with one ofthe sulfonamides (13).

As a species, the staphylococcus is generallymore resistant to the sulfonamides than areseveral other species of pyogenic bacteria.However, several experimental and clinicalstudies, carried out at the University of Minne-sota Hospitals, have revealed that the sulfon-amides are effective antistaphylococcic agents(13, 33 to 37). As a result of these investiga-tions, sulfathiazole has been accepted at theUniversity Hospitals as the most effective of theavailable sulfonamides in the therapy of staphy-lococcic sepsis, but this still leaves much to bedesired. While the failure of patients withstaphylococcic infections to respond to therapywith sulfathiazole is dependent upon severalfactors, the apparent increasing incidence ofpatients having infections due to staphylococciwhich are highly resistant in vitro to sulfathiazolemerits further inquiry.

MATERIALS AND METHODSOF STUDY

Investigations have been carried out with a total of 57strains of staphylococci, obtained from an equal number ofpatients who had various types of staphylococcic infec-tions. Isolation of the parent strains was made in brainbroth or on veal agar-blood plates. The strains were thengrown on slants of veal agar, having a pH of 7.8, and keptin the refrigerator until ready for transfer to a syntheticmedium. Only those strains were selected for study whichgave a positive coagulase test. This test provides themost simple procedure for identifying pathogenic strainsof staphylococci (39). Sodium sulfathiazole was selectedfor testing the resistance of the microorganisms. Com-parative observations with sulfanilamide, sodium sulfa-pyridine, sodium sulfadiazine, and sodium sulfathiazolerevealed that staphylococci were inhibited in their growthto a greater degree by sodium sulfathiazole than by theother sulfonamides. Furthermore, strains that wereresistant to sodium sulfathiazole were more resistant to the

268

SULFONAMIDE-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCI

aforementioned compounds. A water-clear medium ofknown chemical constituents, buffered to give a pH of 7.4,was employed in testing the staphylococci for their re-sistance to sodium sulfathiazole (40). The preparation ofthis medium will be described below. As far as is known,this medium has a neglible amount of sulfonamide inhibi-tor. A standard in vitro test for sulfathiazole-resistancewas used throughout. Strains to be tested were grown forseveral generations in the synthetic medium. As will bepointed out, variable results will be obtained if the initialinoculum of bacteria is not standardized. In performingthe test, 10-fold dilutions of a 24-hour bacterial suspensionwere made in the synthetic medium. Then 0.1 cc. of the10-8 dilution was added to each of several test tubes con-taining the synthetic medium. The approximate numberof cocci seeded to each tube was determined by making du-plicate agar pour plates with 0.1 cc. of the 10-7 dilution. Afreshly prepared, aqueous solution of sodium sulfathiazolewas used. Each strain was tested against varying concen-trations of the compound. This was done by startingwith an initial concentration of 1 mgm. per 100 cc. andthen increasing the concentration of the drug in each of aseries of tubes until a maximum concentration of 360 mgm.was reached. The final total volume of each tube was10 cc. The bacterial suspensions, with and without addedsodium sulfathiazole, were incubated for 24 hours at 370 C.At the end of this period, the degree of bacterial growthwas determined according to the turbidity of the contentsin each tube. Sulfathiazole-resistance was quantitated byselecting the tube which showed complete inhibition ofbacterial growth with the lowest concentration of sodiumsulfathiazole.

In a few instances, cultures of staphylococci were isolatedfrom patients before they had been given a sulfonamide.In the remaining cases, this was not possible becausechemotherapy had been instituted before the patients wereseen.

INGREDIENTS AND PREPARATIONOF

SYNTHETIC MEDIUM

For the preparation of 50 liters of synthetic medium, thefollowing weighed ingredients are mixed together in alarge mortar. The mixture may then be stored in a cleancontainer in the refrigerator until ready for further use.

KH2PO4MgSO4-7H20FeSO4(NH2) 2SO4*6H20NaNOsGlucoseCystinedl methionine1 tryptophanedl valinedl leucine1 aspartic aciddl alanined glutamic aciddl iso-leucine

225.0 grams

2.05 grams

1.25 grams

8.5 grams112.5 grams

1.2 grams

1.5 grams

0.51 grams

7.5 grams

7.5 grams

5.0 grams5.0 grams

5.0 grams

5.0 grams

dl B phenylalanine 5.0 gramsdl lysine.2 HCI 5.0 gramsglycine 2.5 grams1 proline 2.5 grams1 hydroxy-proline 2.5 grams1 tyrosine 2.5 gramsd arginine- HCI 2.5 grams1 histidine HCl 2.5 grams

To prepare a liter of medium, 8.2 grams of the abovemixture are placed in a volumetric flask of 1 L. capacity.Twenty-six cc. of IN NaOHare then added and 0.0337mgm. of thiamin chloride. This quantity of thiaminchloride may be conveniently added by making up astandard solution in distilled water in which there are 10mgm. of thiamin chloride per cc. A dilution of 1 to 296.7is made with this standard solution, and then 1 cc. of thisdilution added to the volumetric flask. Ten cc. of aM/1,000 solution of nicotinic acid are added, and thenenough distilled water to bring the total volume up to 1 L.After thorough mixing in the flask, the pH of the solutionis adjusted to 7.4. The solution is sterilized by passingit through a fine Berkefeld candle (size W) and collecting itin a sterile flask having a capacity of 2 L. The medium isthen tested for sterility.

RESULTS

Standard in vitro test for detectingsulfonamide-resistance

After many in vitro tests for sulfonamide-resistance had been carried out, it became quiteobvious that variable results would be obtainedif the number of cocci inoculated into the testmedium was not controlled. Furthermore, inno instance was a completely resistant strain ofstaphylococcus encountered. The resistance ofstaphylococci to the antibacterial action of thesulfonamides is relative, and the degree of re-sistance is directly related to the size of the inocu-lum. No matter how resistant a strain was, sod-ium sulfathiazole inhibited growth when higherconcentrations of the compound were employed.The effect of the size of the inoculum upon growthinhibition by sodium sulfathiazole is shown inTable I. The strains of staphylococcus cited inTable I were considered to be sensitive to theaction of sodium sulfathiazole. The results with2 sulfonamide-resistant strains are presented inTable II. On the basis of many similar ob-servations, the standard inoculum selected foruse in all the comparative studies was 0.1 cc. ofa 10-3 dilution of a 24-hour culture. Thenumber of organisms in such an inoculum variedbetween 40,000 and 180,000 colonies.

269

WESLEYW. SPINK AND J. J. VIVINO

TABLE I

Influence of sise of inoculum of staphylococci upon inhibition of growth by sodium sulfathiazolIncubation for 24 hours at 370 C.

Concentration of sodium sulfathiazoleStrain

Size of inoculumI 5 10 20 40 60 80 100

mgm. Per 100 cc.0.1 cc. 10-4dilution 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

39 0.1 cc. 10-3dilution + + 0 0 0 0 0 00.1 cc. 10 dilution + + + + + + + + +0.1 cc. 10-1 dilution ++++ ++++ +++ +++ +++ ++ ++ ++

0.1 cc. 10-dilution + + 0 0 0 0 0 033 0.1 cc. 10-1 dilution ++++ ++ 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.1 cc. 10- dilution ++++ ++++ +++ ++ + 0 0 00.1 cc. 10-1 dilution ++++ +++ +++ +++ +++ +++ +++ ++

0.1 cc. 10-4 dilution 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 01 0.1 cc. 1-0 dilution 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.1 cc. 10- dilution + 0 0 0 0 0 0 00.1 cc. 10-1 dilution +++ ++ ++ ++ ++ + 0 0

0.1 cc. 10-4 dilution 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 02 0.1 cc. 10-3 dilution 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.1 cc. 10- dilution 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 00.1 cc. 10-1 dilution ++++ +++ ++ ++ ++ ++ + +

0.1 cc. 104 dilution 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 035 0.1 cc. 10-3 dilution 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.1 cc. 10- dilution 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 00.1 cc. 10-1 dilution ++++ ++ ++ ++ ++ ++ + +

0= No growth.+ ++ + Maximum growth.

TABLE II

Influence of sie of inoculum of sulfonamide-resistant staphylococci upon inhition of growth by sodium sidfathialeIncubation for 24 hours at 370 C.

Concentration of sodium sulfathiazole

Snumbe Size of inoculumSize of 100 j 140 180 220 260 300 340

mgm. per 100 cc.0.1 cc. 10-4dilution ++++ +++-+ 0 0 0 0 0

42 0.1 cc. 10-' dilution ++++ ++++ ++ 0 0 0 00.1 cc. 102dilution ++++ +++ +++ ++ 0 0 00.lcc. l0 Idilution ++++ ++++ +++ +++ +++ +++ ++

0.1 cc. 10' dilution ++++ ++++ ++ ++ 0 0 041 0.1 cc. 10-' dilution ++++ ++++ ++++ ++ + 0 0

0.l cc. 10- dilution ++++ ++++ ++++ ++++ +++ +++ ++

0 = No growth.+ + ++ = Maximum growth.

Correlion between strains of staphylococci sensi- Table III. These strains were considered to betive to sodium sulfathiazole in vitro and the the most sensitive to the antibacterial action of

results of sulfonamide therapy sodium sulfathiazole. It will be noted that 9 ofData for 32 strains of staphylococci, whose 32 patients from whomthe strains were isolated

in vitro growth was inhibited by less than 1 mgm. received one or more of the sulfonamides priorper 100 cc. of sodium sulfathiazole, are given in to the time when the culture of staphyloccus

270

SULFONAMIDE-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCI

TABLE III

Summary of non-resistknt strains of staphylococcusGrowth inhibited by less than 1 mgm. per 100 cc. of sodium sulfathiazole

ant ad Type oflesionA Sulfonamide therapy prior to Commentsttrain aneProflstio isolation of strainnumber SCX ~~1~

Bacteremia, Prostatitis, Thrombo-phlebitis

Osteomyelitis,. left femurImpetigo, Acute hemorrhagic ne-

phritisDiabetes mellitus, Bacteremia,

Osteo. rt. foot

37 M. Tbc. rt. wrist

Osteo. rt. femur

Subacute bacterial endocarditis

CellulitisBacteremia, Osteo. left femurBacteremia, Osteo., Pneumonia,

EmpyemaChronic osteo. with exacerbation

and bacteremiaBacteremia, Thrombophlebitis,

MeningitisChronic osteo.Chronic osteo.

Chronic osteo.

Chronic osteo., Perinephritic ab-scess, Empyema

Ca bladderChronic osteo. left femur and

humerus

Bacteremia, Osteo., Pericarditis,Empyema

Osteo., Pericarditis, Empyema

Bacteremia, Osteo., Pneumonia

Tbc. adenitisReticulo-endotheliosis, Abscess of

neckBacteremia, Pneumonia, Osteo. of

mandible, Abscess of neck

Abscess rt. thighHydrocephalus, Meningitis

Bacteremia, Chronic osteo., Pul-monary abscesses, Meningitis

Left pyelonephritis and hydrone-phrosis

Diabetes mellitus, BacteremiaActinomycosis liver and perito-

neumBacteremia, Osteo.

Bacteremia, Osteo.

13 grams sod. sulfathiazole i.v.in 3 days.

42 grams sulfathiazole, 11 days.None

34 grams sulfadiazine in 9 days.33 grams sulfathiazole in 8days. Sulfathiazole locallyto osteo.

Sulfathiazole locally for 2months and 4 grams dailyorally for 1 month. No drugfor 2 months prior to obtain-ing culture.

Large amounts sulfathiazoleand sulfadiazine for 3 months.

None

NoneNoneSulfanilamide, amount not

known.None

Sulfapyridine and sulfathiazole,amounts not known.

NoneNone

None

None

NoneLarge amounts sulfapyridine

and sulfathiazole, none for 6months prior to isolatingculture.

None

Sulfadiazine for 9 days, amountnot known.

None

NoneNone

None

NoneNone

None

None

NoneNone

None

None

Died. Some improvement follow-ing penicillin.

No improvementDied

Recovery. Bacteremia persistedwith sulfonamide therapy. Bloodsterile after penicillin. Amputa-tion rt. leg.

No improvement from chemother-apy. Surgery, rt. wrist.

No improvement

Died. Temporary improvementfrom sulfapyridine.

Died. Strain produced lethal toxin.Recovery. No chemotherapy.Died

Recovery. Improvement from sul-fanilamide and sulfapyridine.

Died

Improvement following surgery.Improvement following surgery and

sulfapyridine.Improvement following surgery.

Questionable value of sulfonamidetherapy.

Recovery following surgery.

No changeImprovement

Recovery following penicillintherapy.

Recovery following penicillintherapy.

Recovery following penicillintherapy.

ImprovementDied

Recovery following surgical drain-age. Also received sulfanilamideand staphylococcus antitoxin.

RecoveryRecovery. Received sulfanilamide

Died

Recovery following surgery.

DiedDied

Recovery. Received sulfanilamideand sulfapyridine.

Died

78 M.

43 F.3 M.

51 M.

1

23

4

5

6

7

89

10

11

12

1314

15

16

1718

19

20

21

2223

24

2526

27

28

2930

31

32

43 M.

25 F.

23 F.16 M.20 M.

39 F.

14 M.

7 M.13 F.

40 M.

36 M.

84 M.4 M.

7 F.

9 F.

13 F.

74 M.23 M.

26 M.

19 M.16mo.

M.14 F.

32 F.

68 M.22 M.

12 M.

26 M.

271

WESLEYW. SPINK AND J. J. VIVINO

was isolated from the patient. In 2 of 10patients, a sulfonamide had not been taken forseveral months before isolating the strain ofstaphylococcus (Patients 6 and 19). In mostinstances, treatment with the sulfonamides wasinstituted by physicians before the patientsentered the University Hospitals. This andother circumstances did not permit us to deter-mine the precise amount of sulfonamide that hadbeen administered.

Since the strains of staphylococcus isolatedfrom the patients in this series were sensitive tothe in vitro action of sodium sulfathiazole, thenext step was to analyze the effect of sulfona-mide therapy upon the clinical course of thesepatients. Sulfonamides were administered to10 patients after the test cultures were isolated.Patient 7 had subacute bacterial endocarditis.She was given sulfapyridine over a prolongedperiod of time which was associated with tem-porary improvement, but her clinical courseended in death. Patient 11 had a chronic osteo-myelitis with an acute exacerbation and staphy-loccic bacteremia. Following the administra-tion of sulfapyridine, the blood stream becamesterile and the patient improved. Chemo-therapy had little effect upon the local lesion.Surgical drainage of an osteomyelitic lesion wascombined with sulfapyridine in Patient 14,which was followed by improvement. This alsoapplies to Patient 15. In both cases, it wasdifficult to assay the benefit of treatment withsulfapyridine. Treatment with sulfanilamidewas without effect in Patient 24. Patient 26was a small infant with staphylococcic menin-gitis and coincident with the use of sulfanilamide,the child recovered. Patient 31 received sulfa-pyridine for the treatment of acute osteomyelitisand bacteremia. Chemotherapy appeared to bedefinitely effective in this patient. Penicillinwas given to 3 patients (Patients 1, 4, and 20),after either sulfathiazole or sulfadiazine hadfailed to control the infections.2 Of the 9patients (Patients 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 10, 12, 18, and 20)who received one or more of the sulfonamidesprior to isolation of the test culture, only one

2 The penicillin used for experimental and clinicalpurposes was obtained through the Committee of Chemo-therapeutic and Other Agents of the National ResearchCouncil.

(Patient 18) appeared to benefit from suchtherapy.

In summary then, although a group of patientshad infections due to a strain of staphylococcuswhich was sensitive in vitro to sulfathiazole, andto a less extent to some of the other sulfonamides,no consistent and outstanding therapeutic re-sults were obtained in 13 of 32 patients who weregiven one of the sulfonamides.

Attention is called to the fact that several ofthe strains listed in Table III were isolated frompatients before it had been established at theUniversity Hospitals that sulfonamide therapymight be of definite value in selected cases ofstaphylococcic sepsis. Cultures of many ofthese strains had been maintained on veal-agarslants under oil for several months before theirin vitro susceptibility to sodium sulfathiazole wastested. It might be postulated that some of theparent cultures of these strains may have beensulfonamide-resistant, but during the course ofmany subcultures, this resistance became lost.Evidence will be presented to show that theacquisition of sulfonamide-resistance by sta-phylococci is more or less a permanent charac-teristic, and that this resistance does not disap-pear or diminish following many subcultures.

Correlation between strains of staphylococci moder-ately resistant to sodium sulfathiazole in vitro

and the results of sulfonamide therapyA second series of 8 strains of staphylococcus

were tested in vitro and all were found to bemore resistant to sodium sulfathiazole. Theresults with this group are presented in Table IV.These strains required more than 1 mgm. per100 cc. of sodium sulfathiazole and a concentra-tion of less than 100 mgm. before growth wasinhibited. In all but 3 cases (Patients 33, 37,and 40), a sulfonamide had been administeredprior to isolation of the test strain. There is thepossibility that Patients 37 and 40 received asulfonamide before they were seen at the Univer-sity Hospitals, but definite evidence is lacking.

In 2 of the patients (Patients 33 and 36), aculture of staphylococcus was isolated beforechemotherapy, and then after a sulfonamide hadbeen given. Patient 33 had a severe staphylo-coccic bacteremia associated with a thrombo-

272

SULFONAMIDE-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCI

TABLE IV

Summtary of resistant strains of staphylococcusGrowth inhibited by less than 100 mgm. per 100 cc. sodium sulfathiazole

Patient Mgm. per 100and Age Sulfonamide therapy ccfsuoatiuml omet

strain and Type leion prior to isolation |ithicole Commentsnum- sem of strain with com lete

inhibition

33 59 F. Bacteremia, Thrombophle- None 10 Died. Received 52 gramsbitis sulfathiazole in 8 days.

34 12 F. Bacteremia, Cellulitis, Osteo. 174.5 grams sulfathiazole over 20 Marked improvement.2-year period. Also sulfa-nilamide.

35 32 F. Pneumonia, Empyema, Sulfonamide in largeamounts. 20 Marked improvement.Osteo. of ribs Quantity not known. Osteo. persistent after

chemotherapy.36 46 M. Bacteremia, Retrobulbar 195.75 grams sulfathiazole 5 Complete recovery.

abscess, Osteo. orally and parenterally. 78grams sulfadiazine orally.Sulfathiazole locally.

37 64 F. Urethritis and urethral car- None 5 Improvement after opera-buncle tion.

38 57 M. Ca prostate with cystitis 21 grams sulfathiazole. 80 Died following operation.39 32 F. Bacteremia, Carbuncle, Large amounts of sulfathiazole 10 Marked improvement follow-

Osteo. of spine, tibia, for several weeks. Quantity ing sulfonamide therapy.fibula, and rt. femur not known. No evidence of active in-

fection after penicillin.40 78 M. Ca prostate and bladder None 20 Receiving stilbesterol.

phlebitis. Prior to treatment with sulfathiazole,the growth of a strain of staphylococcus isolatedfrom her blood was completely inhibited by lessthan 1 mgm. of sodium sulfathiazole.. Therewere 100 colonies of staphylococci per cc. in herblood when therapy with sulfathiazole was insti-tuted. After receiving 52 grams of sulfathiazolein 8 days, she appeared moribund. The colonycount of a blood culture was 473, and a strainof staphylococcus isolated from her blood re-quired 10 mgm. of sodium sulfathiazole beforegrowth was inhibited. The concentration offree sulfathiazole in her blood at this time was15 mgm. per 100 cc. While care must be takenin transposing in vitro observations of this natureto clinical phenomena, it is not unlikely that theincrease in in vitro resistance may have beenassociated in part with a fatal outcome. Similarobservations were made with cultures obtainedfrom Patient 36. This individual recoveredafter a very serious infection, and there is nodoubt that the intensive use of sulfathiazoleplayed a r8le in his favorable outcome. At onetime, during the course of treatment, a bloodculture revealed a colony count of 264 organismsper cc. In spite of the use of large amounts ofsulfathiazole, the causative organism apparentlydeveloped only a minimal degree of resistance.

The results of therapy with sulfathiazole inthe group of cases presented in Table IV weremore satisfactory than had been obtained withsulfapyridine. This was to be anticipated, inpart, following comparative in vitro tests withthe 2 compounds when it was shown that sulfa-thiazole was superior to sulfapyridine in inhibit-ing growth of the staphylococcus.

Correlation between strains of staphylococci highlyresistant to sodium sulfathiazole in vitro and

the results of sulfonamide therapyTable V presents a summary of 17 strains of

staphylococci which are considered highly re-sistant to the sulfonamides. A concentration ofat least 100 mgm. per 100 cc. of sodium sulfa-thiazole was necessary before growth was com-pletely inhibited. All of the patients except one(Patient 54) received sulfonamide therapy priorto isolation of the test strain. In this one pa-tient, there remains a possibility that sulfona-mide treatment had been carried out before hewas admitted to the hospital. An importantand interesting aspect of this group of sulfon-amide-resistant strains is that 14 of the 17strains were isolated from the urine of patientshaving urinary tract infections. In 12 of the 14patients with infection of the urinary tract, there

273

WESLEYW. SPINK AND J. J. VIVINO

TABLE V

Summary of resistant strains of staphylococcusGrowth inhibited by 100 mgm. per 100 cc. or more of sodium sulfathiazole

Patient Mgm. per 100and Age Sulfonamide therapy cc. of sodium

strain and Type of lesion prior to isolation sut atiazole Commentsnum- sex of strain giohbt

~~~~~~~~I ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~inhibitionUlcerative colitis, Chr

pyodermaBacteremia, Osteo.

Bacteremia, Cellulitis, Itatic obstruction

Encysted cystitis, Prosiobstruction with cysti

Prostatic obstructioncystitis

Rt. ureter obstructed,lonephritis

Prostatic obstructioncystitis. Suprapubictostomy

Rt. renal calculi andscesses

Prostatic obstructionacute pyelonephritis

Bilateral renal calculileft hydronephrosis

Chronic pyelonephritiswith left tubo-ovariarscess

Purulent bronchiolitisliver abscesses

Prostatic obstructioncystitis

Ca bladder, Bilaterallonephritis

Prostatic obstructioncystitis

Prostatic obstructioncystitis

Bilateral polycystic kidwith uremia

with

126 grams sulfathiazole orally,sulfathiazole locally.

326 grams sulfathiazole orallyover 2 years, 46 gramssulfapyridine, sulfathiazolelocally.

Large amounts sulfonamide,quantity unknown.

15 grams sulfadiazine. Con-tinuous bladder irrigationwith 0.8 per cent sulfa-nilamide solution, 5 days.

Sulfonamides at intervalsfor several months. 6.5grams sulfathiazole.

Sulfonamides intermittently,amount not known.

Sulfathiazole orally, amountnot known. Sulfathiazolelocally.

38 grams sulfathiazole. 29grams sulfadiazine.

51 grams sod. sulfathiazolei.v.

Unknown amounts sulfona-mide.

29 grams sulfadiazine.

21 grams sulfadiazine. 9grams sulfamerazine.

Continuous bladder irrigationwith 0.8 per cent sulfanila-mide solution. 5.5 gramssulfathiazole.

None

39.5 grams sulfathiazole.

112 grams sulfadiazine.

17 grams sulfathiazole.

250

200

100

100

200

180

200

180

200

200

200

160

200

160

180

200

200

Died. Only temporary im-provement of skin lesions.

Marked impfovement. Re-sidual active osteo.

Died. No improvement.

Improvement following op-eration. Resistant staph.from urine 5 times.

Improvement following op-eration. Resistant staph.persisted in urine afteroperation.

Improvement following op-eration.

Improvement following op-eration.

Improvement following ne-phrectomy.

Died. Bacteremia due togammastrept.

Improvement following sur-gery.

Improvement following ne-phrectomy.

Died

Died. Acute cardiac failure.

Died. Cardiac failure afteroperation.

Improvement following op-eration.

Improvement following op-eration.

Died. Resistant staph. inurine 3 times.

was definite evidence of some degree of obstruc-tion to the free flow of urine. It is well recog-

nized that the efficiency of the sulfonamides isreduced in the treatment of urinary tract diseasewhen a free flow of urine is interrupted. Thismeans that in the latter group of patients, sta-phylococci were being constantly exposed torelatively high concentrations of one or more ofthe sulfonamides. It is not unlikely that underthese circumstances the organisms become in-creasingly resistant to the compounds. Anothersignificant feature is that this group of resistant

strains, isolated from urine, were obtained over

a short period of time. In 2 instances (Patients44 and 45), sulfonamide-resistant staphylococcipersisted in the urine after the obstruction hadbeen corrected by surgical interference. Un-fortunately, we were unable to obtain strains ofstaphylococci from any of the patients given inTable V before the administration of a sulfon-amide. Several of these highly resistant strainshave been investigated concerning the mecha-nism whereby they become resistant to the sul-fonamides. This will be discussed. A definite

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

13 F.

15 F.

72 M.

74 M.

72 M.

28 F.

66 M.

65 M.

74 M.

45 M.

38 F.

4 F.

80 M.

75 F.

86 M.

60 M.

50 M.

274

SULFONAMIDE-RESISTANT STAPHYLOCOCCI

relationship was found to exist between thetherapeutic response to a sulfonamide and thepresence of sulfonamide-resistant staphylococci.In the cases of urinary tract obstruction, definiteclinical improvement occurred only after the ob-struction had been eliminated. The most re-sistant strain of staphylococcus that we haveencountered was isolated from Patient 41, whohad an extensive infection of the skin. She hadreceived large amounts of sulfathiazole orally,and sulfathiazole ointment had been appliedlocally. There was only temporary improve-ment in her skin lesions and she died because ofa chronic ulcerative colitis.

Summary of relationship between in vitro suscepti-bility of staphylococci to sodium sulfathia-

zsol and sulfonamide therapy priorto isolation of the strains

A summary of this relationship is given inTable VI. Group I comprises all the strainssensitive to the action of sodium sulfathiazole.Of the 32 patients from whom these strains wereobtained, only 9 had received a sulfonamide

TABLE VI

Summary of relationship between the in vitro susceptilityof staphylococci for sodium sulfathiazole and sulfon-

amide therapy prior to isolation of the strains

Number of

Nu. patientsof sulfonmide Commentsris pior tostrains isolation of

staphylococci

Group I strains- 32 9sensitive to sodiumsulfathiazole.

Group II strains- 8 5 Possibly 2 additionalmoderately resistant to patients receivedsodium sulfathiazole. sulfonamide.

Group III strains- 17 16 Possibly seventeenthhighly resistant to patient receivedsodium sulfathiazole. sulfonamide.

prior to isolation of the strains. There were 8strains in Group II, and these strains were

moderately resistant. Five, and possibly 7, ofthe 8 patients had been given a sulfonamidebefore the staphylococci were recovered fromtheir lesions. There were 17 strains in GroupIII, all of which were highly resistant to sodiumsulfathiazole. Sixteen of the 17 patients fromwhom these strains were isolated had had sul-fonamide therapy prior to the isolation of theorganisms. There is some evidence that the

seventeenth patient had been given a sulfona-mide. Although it cannot be concluded that theresistance of staphylococci to the inhibitoryaction of sodium sulfathiazole is due to previoussulfonamide therapy, it is obvious that themajority of the resistant strains were isolatedfrom patients who had been given a sulfonamide.

Acquired sulfonamide-resistance apersistent characteristic

All of the resistant strains of staphylococciincluded in this report have been subculturednumerous times on veal agar slants, and insynthetic medium, and in no instance did astrain lose its ability to resist the action of thesulfonamides. This relatively permanent featureof sulfonamide-resistance is emphasized byresults obtained with strains 41 and 42. Asnoted in Table V, these 2 strains of staphylococciwere quite resistant to sodium sulfathiazole.Each of these strains was subcultured on vealagar and in synthetic medium for 75 generations.Comparative in vitro tests revealed that theseventy-fifth generations possessed the samedegree of resistance as the parent strains. Bothstrains remained coagulase-positive. Strains 41and 42 were each grown on veal agar slants, andthen the cultures were covered with oil andstored in a refrigerator for 114 days. At the endof this time, the 2 strains were grown for severalgenerations in synthetic medium and their invitro resistance to -sodium sulfathiazole tested.There was no diminution in the resistance of theorganisms to the inhibitory effect of the sulfon-amide.

DISCUSSION

The foregoing data represent the results ofobservations that have been made during thepast 2 years. It became apparent early in thecourse of these studies that the mechanismwhereby staphylococci developed resistance tothe sulfonamides required elucidation. Thiseffort was stimulated by the investigations ofMacLeod (41) who showed that a Type I strainof sulfapyridine-resistant pneumococcus pro-duced a substance which inhibited the action ofsulfapyridine. Mirick (42) investigated thissulfonamide inhibitor and brought forth con-siderable evidence that this inhibitor was actually

275

WESLEYW. SPINK AND J. J. VIVINO

p-aminobenzoic acid. This information sug-

gested to us that staphylococci became resistantto kthe sulfonamides by means of a similarmechanism. The most resistant strains includedin the present report were subjected to a groupof observations with this thesis in mind. As aresult, we have concluded that as far as thestaphylococcus is concerned, sulfonamide-re-sistance is dependent at least in part, upon theelaboration of p-aminobenzoic acid by thebacterial cell. These observations will be pub-lished in detail elsewhere. This supports theconclusions of Landy and his group (43). Itshould be emphasized that even the so-callednon-resistant strains of staphylococcus producep-aminobenzoic acid, but to a lesser degree thanthe resistant strains. There is some evidence athand which would indicate that the more re-

sistant strains of staphylococci produce relativelylarge amounts of p-aminobenzoic acid, especiallyin the presence of the sulfonamides (44). Whilethe mechanism whereby staphylococci resist theinhibitory action of the sulfonamides may beexplained in part on the basis of the formationof p-aminobenzoic acid acting as a sulfonamideinhibitor, this mechanism does not necessarilyapply to other species of bacteria. Recent evi-dence would indicate that another mechanism or

mechanisms is responsible (9, 43).The use of the sulfonamides in the treatment

of staphylococcic infections presents many

problems. Even though in vitro tests may showthat a particular strain of staphylococcus issusceptible to the action of a sulfonamide,attempts at therapy with this sulfonamide may

be unsuccessful or not too satisfactory. This isrelated in large part to the nature of staphy-lococcic sepsis. Localized lesions, serving as

foci for blood stream invasion, are made up ofexudate, tissue necrosis, cellular debris, and deadorganisms, all of which may inhibit the action ofthe sulfonamide. If, in addition to these factors,the organism becomes resistant to the sulfon-amide, the likelihood of controlling an infectionis further reduced. Another disturbing featurein our experience with staphylococcic infectionsis that sulfonamide-resistant strains of staphy-lococci are being encountered much more fre-quently at the present time than 2 or 3 years

ago. This may be due to several factors. One

is that the sulfonamides are being administeredmore freely to patients with staphylococcicsepsis before they are brought to the UniversityHospitals for further treatment. Another possi-bility is that sulfonamide-resistant strains arebeing disseminated because of the widespreaduse of the sulfonamides.

Particular attention should be given to the fre-quency with which sulfonamide-resistant strainsof staphylococci were isolated from the urine ofpatients with varying types of urinary tract in-fections. In many cases, a low-grade infectionwas associated with obstruction to the flow ofurine. The development of sulfonamide-resist-ant organisms is not to be taken too lightly,particularly if operative interference is con-templated. In one patient (Patient 43), ahighly resistant strain of staphylococcus wasobtained from the urine. This individual hadbenign prostatic hypertrophy with obstruction.Sulfonamides were administered prior to surgery,and following a transurethral prostatic resection,he developed a fatal staphylococcic bacteremia.The strain isolated from his blood was also re-sistant to the in vitro action of sulfathiazole, andtherapy with this compound was of no value incontrolling the infection. It is possible that thesame sequence of events may take place inpatients with other species of bacteria in theurinary tract as brought out in the followingobservation. Patient 49 developed a fatal bac-teremia due to an anhemolytic strain of strep-tococcus, following a transurethral prostaticresection. This organism was cultured from theurine and the blood, and in vitro tests showed itto be highly resistant to sulfathiazole. It isof interest that, in 1926, Feirer and his associates(45) called attention to the development of"drug-fast" organisms in the urine againsturinary antiseptics, which were derivatives of theheavy metals. On the basis of this observation,they suggested a rotation of drugs in the treat-ment of chronic urinary infections.

It is becoming more and more apparent thatspecific agents, other than the commonly usedsulfonamides, are desirable in the treatment ofpatients with severe staphylococcic infections.There is increasing evidence that the antibioticagents, such as penicillin, will yield more satis-factory clinical results. Wehave compared the

276

SULFONAMIDE-RESISTANTSTAPHYLOCOCCI

in vitro action of sulfathiazole and penicillin.against the 57 strains given in this report, theresults of which work will be presented elsewhere.It is significant that p-aminobenzoic acid doesnot inhibit the action of penicillin against thestaphylococcus. On the other hand, staphylo-cocci may develop in vitro resistance to penicillin,apparently by means of a different mechanism.This feature is undergoing investigation at thepresent time.

SUMMARY

1. The problem of sulfonamide-resistant bac-teria in general is briefly reviewed.

2. Fifty-seven strains of coagulase-positivestaphylococci, isolated from an equal number ofpatients, were tested in vitro with a standardprocedure against sodium sulfathiazole in a

synthetic medium, containing negligible amountsof sulfonamide inhibitor. Thirty-two of thestrains were considered non-resistant; 8 were

moderately resistant; while 17 strains required a

concentration of 100 mgm. per 100 cc. or more

of sodium sulfathiazole. before growth was com-

pletely inhibited.3. The acquisition of sulfonamide-resistance

by staphylococci is a persistent characteristic ofthe organisms.

4. Although it is apparent that sulfonamide-resistant staphylococci do not necessarily developas a result of the administration of the sulfon-amides, the evidence presented in this paper

indicates that resistant strains are almost alwaysisolated from patients who have had previoussulfonamide therapy.

5. The development of sulfonamide-resistanceby staphylococci is dependent, at least in part,upon the elaboration of p-aminobenzoic acid bythe bacterial cells.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. MacLean, I. H., Rogers, K. B., and Fleming, A., M.and B. 693 and pneumococci. Lancet, 1939, 1, 562.

2. MacLeod, C. M., and Daddi, G., A "sulfapyridine-fast" strain of pneumococcus Type I. Proc. Soc.Exper. Biol. and Med., 1939, 41, 69.

3. Schmidt, L. H., and Dettwiler, H. A., Development of"sulfapyridine-fastness" in vivo. J. Biol. Chem.,1940, 133, lxxxv.

4. Dettwiler, H. A., and Schmidt, L. H., Observations on

the development of resistance to sulfapyridine bydiplococcus pneumoniae. J. Bact., 1940, 40, 160.

5. Schmidt, L. H.,rSesler, C. L., and Dettwiler, H. A.,Studies on sulfonamide-resistant organisms. I. De-velopment of sulfapyridine resistance by pneumo-cocci. J. Pharmacol. and Exper. Therap., 1942, 74,175.

6. Sesler, C. L., and Schmidt, L. H., Studies on sulfon-amide-resistant organisms. II. Comparative de-velopment of resistance to different sulfonamides bypneumococci. J. Pharmacol. and Exper. Therap.,1942, 75, 356.

7. MacLeod, C. M., The antibacterial action of the sulfo-namide drugs. Advances in Internal Medicine,1942, 1, 83.

8. Frisch, A. W., Price, A. E., and Myers, G. B., TypeVIII pneumococcus: Development of sulfadiazineresistance, transmission by cross infection, and per-sistence in carriers. Ann. Int. Med., 1943, 18, 271.

9. Tillett, W. S., Cambier, M. J., and Harris, W. H., Jr.,Sulfonamide-fast pneumococci. A clinical report oftwo cases of pneumonia together with experimentalstudies on the effectiveness of penicillin and tyro-thricin against sulfonamide-resistant strains. J.Clin. Invest., 1943, 22, 249.

10. Hendry, J. L., A study of hemolytic streptococci froma horse treated with sulfanilamide after strepto-coccal bacteremia developed during immunization.J. Infect. Dis., 1942, 70, 112.

11. Cutts, M., and Troppoli, A. V., Acquired drug re-sistance in the hemolytic streptococcus. J. Lab.and Clin. Med., 1942, 28, 14.

12. Strauss, E., Dingel, J. H., and Finland, M., Studies onthe mechanism of sulfonamide bacteriostasis, in-hibition and resistance: Experiments with staphylo-coccus aureus. J. Immunol., 1941, 42, 331.

13. Vivino, J. J., and Spink, W. W., Sulfonamide-resistantstrains of staphylococci: Clinical significance. Proc.Soc. Exper. Biol. and Med., 1942, 50, 336.

14. Strauss, E., Dingle, J. H., and Finland, M., Studies onthe mechanism of sulfonamide bacteriostasis, in-hibition and resistance: Experiments with E. coliin a synthetic medium. J. Immunol., 1941, 42, 313.

15. Kirby, W. M. M., and Rantz, L. A., Quantitativestudies of sulfonamide resistance. J. Exper. Med.,1943, 77, 29.

16. Green, H. N., The mode of action of sulphanilamide:With special reference to a bacterial growth-stimulating factor ("P" factor) obtained from Br.abortus and other bacteria. Brit. J. Exper. Path.,1940, 21, 38.

17. Marshall, E. K., Jr., Bacterial chemotherapy. Ann.Rev. Physiol., 1941, 3, 643.

18. Cooper, M. L., and Keller, H. M., Sodium sulfathiazoleresistant Shigella paradysenteriae Flexner andSonne. Proc. Soc. Exper. Biol. and Med., 1942,51, 238.

19. Boak, R. A., and Carpenter, C. M., Resistance of thegonococcus in vitro to gradually increased concen-

- trations of sulfanilamide. J. Bact., 1939, 37, 226.

277

WESLEYW. SPINK AND J. J. VIVINO

20. Westphal, L., Charles, R. L., and Carpenter, C. M.,The development of sulfapyridine-fast strains of thegonococcus. Ven. Dis. Inform., 1940, 21, 183.

21. Carpenter, C. M., Charles, R., and Allison, S. D.,Effect of gradually increased concentrations ofsulfathiazole on the gonococcus in vitro. Proc. Soc.Exper. Biol. and Med., 1941, 48, 476.

22. Kirby, W. M. M., Development of sulfathiazole-resistant gonococci in vitro. Proc. Soc. Exper.Biol. and Med., 1943, 52, 175.

23. Ross, R. W., Acquired tolerance of pneumococcus toM. and B. 693. Lancet, 1939, 1, 1207.

24. Lowell, F. C., Strauss, E., and Finland, M., Observa-tions on the susceptibility of pneumococci to sulfa-pyridine, sulfathiazole and sulfamethylthiazole.Ann. Int. Med., 1940,14, 1001.

25. Moore, F. J., Thomas, R. E., and Hoyt, A., Sensitivityof pneumococci to sulfapyridine. J. A. M. A.,1941, 117, 437.

26. Frisch, A. W., Sputum studies in pneumonia: In vivoand in vitro susceptibility of pneumococci to sulfa-pyridine and sulfathiazole. Am. J. Clin. Path.,1941, 11, 797.

27. Auger, W. J., Sulfapyridine resistance of pneumococcifollowing sulfapyridine therapy in infants andchildren and comparative potency of three chemo-therapeutic agents for pneumococci as shown bylaboratory tests. J. Pediat., 1941, 18, 162.

28. Hamburger, M., d al., Sulfonamide resistance develop-ing during treatment of pneumococcic endocarditis.J. A. M. A., 1942, 119, 409.

29. Francis, A. E., Sulphonamide resistant streptococci ina plastic surgery ward. Lancet, 1942, 1, 408.

30. Green, H. N., Laboratory infection with Brucellaabortus. Brit. M. J., 1941, 1, 478.

31. Cohn, A., Steer, A., and Seijo, I., Correlation betweenclinical and in vitro reactions of gonococcus strainsto sulfathiazole: A preliminary report. Am. J. M.Sc. 1942, 203, 276.

32. Petro, J., Sulphonamide resistance in gonorrhoea.Lancet, 1943, 1, 35.

33. Spink, W. W., The bactericidal effect of sulfanilamideupon pathogenic and non-pathogenic staphylococci.J. Immunol., 1939, 37, 345.

.34. Spink, W. W., and Jermsta, J., Effect of sulfonamidecompounds upon growth of staphylococci in presenceand absence of p-aminobenzoic acid. Proc. Soc.Exper. Biol. and Med., 1941, 47, 395.

35. Spink, W. W., The pathogenesis and treatment ofstaphylococcal infections. Internat. Clin., 1941, 4,236.

36. Spink, W. W., Hansen, A. E., and Paine, J. R.,Staphylococcic bacteremia: Treatment with sulfa-pyridine and sulfathiazole. Arch. Int. Med., 1941,67, 25.

37. Spink, W. W., and Haserick, J. R., Treatment ofstaphylococcal infections. Staff Meeting Bulletin,Hospitals of the University of Minnesota, 1942, 13,196.

38. Spink, W. W., Sulfanilamide and Related Compoundsin General Practice. Year Book Publishing Co.,Chicago, 1942, 2nd ed., p. 104.

39. Spink, W. W., and Vivino, J. J., The coagulase test forstaphylococci and its correlation with the resistanceof the organisms to the bactericidal action of humanblood. J. Clin. Invest., 1942, 21, 353.

40. Gladstone, G. P., Inter-relationships between aminoacids in the nutrition of B. anthracis. Brit. J.Exper. Path., 1939, 20, 189.

41. MacLeod, C. M., The inhibition of the bacteriostaticaction of sulfonamide drugs by substances ofanimal and bacterial origin. J. Exper. Med., 1940,72, 217.

42. Mirick, G. S., Enzymatic identification of p-amino-benzoic acid (PAB) in cultures of pneumococcusand its relation to sulfonamide-fastness. J. Clin.Invest., 1942, 21, 628.

43. Landy, M., Larkum, N. W., Oswald, E. J., andStreightoff, F., Increased synthesis of p-amino-benzoic acid associated with the development ofsulfonamide resistance in staphylococcus aureus.Science, 1943, 97, 265.

44. Spink, W. W., and Vivino, J. J., Pigment production bysulfonamide-resistant staphylococci in the presenceof the sulfonamides. Science, 1943, 98, 44.

45. Feirer, W. A., Meader, P. D., and Leonard, V., Devel-opment of the drug fast character in vitro and itsbearing upon drug rotation in the management ofchronic urinary infections. J. Urol., 1926, 16, 97.

278