Sub-Module 1: Inter-governmental Relations in Japan

Transcript of Sub-Module 1: Inter-governmental Relations in Japan

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

Sub-Module 1: Inter-governmental Relations in Japan

Noriaki WATARI Graduate School of Law, Kyoto University

Chikara NAGATO Lecturer, Faculty of Law, Meijo University

Kentaro SO Graduate School of Law, Kyoto University

Seong Kook Youn Graduate School of Law, Kyoto University

Section1. RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN CENTRAL AND LOCAL GOVERNMENTS 1. Administrative development and achievement of a National Minimum* in Japan (*National Minimum : A national entitlement of standard of

living. To guarantee this standard, minimum wage system and livelihood protection

system are introduced. )

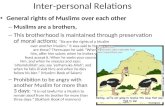

1-1. “Centralization-decentralization”/“separation-interfusion” model To analyze Japanese intergovernmental relationships, we can use the two-axes model

developed by Akira Amakawa, identified as the “Centralization-Decentralization/

Separation-Interfusion” model. Refer to Diagram 1 below. According to Amakawa, the

two axes can be used to explain the relationship between the central government and

local governments.

Diagram 1: Amakawa’s “Centralization-Decentralization / Separation-

interfusion” Model

1

Centralization

Separation Interfusion

Decentralization

centralization-separation

decentralization-interfusion

centralization-interfusion

decentralization-separation

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

The vertical, centralization-decentralization axis refers to the level of autonomy that local

governments have in terms of their decision-making. It shows how much the local

government can accommodate suggestions, ideas, and opinions of local residents in their

decisions. A fully “centralized” situation is one where the central government makes most

of the decisions for a local government and fully controls the decision-making capacity of

a local government and its residents. On the other hand, a fully “decentralized” situation

is characterized by decision-making power controlled and executed by the local

government and its residents.

The horizontal, Separation-Interfusion axis refers to the level of central government

involvement in the administrative responsibility within the local government territory.

“Separation” is the situation where central governments agents manage the central

administrative operations within the local territory. At the other end, “Interfusion” is the

situation where the local government manages the central administrative operations

independent of any central government control.

Using this diagram, central-local relations can be divided into four types; “Centralization-

separation,” “Centralization-interfusion,”“Decentralization-separation,” and

“Decentralization-interfusion.” (Amakawa, 1986).

1-2. Japan - A centralization-interfusion Japan is a unitary state and has agency delegation 1, subsidiary and ‘amakudari’

relocation (a system whereby a central bureaucrat is posted to a senior position in the

prefectures). Quoting Yoshizaburo Ichikawa, “In the agency delegation system, the local

government carries out the nation’s affairs under the nation’s supervision. To conduct

affairs in the agency delegation system, the acting agency in the local government is

recognized as a lower-class national institution, controlled and supervised by the

competent minister.” (Ichikawa 2002, p35) The motivation behind the agency delegation

system is to ensure a system of government where business is carried out based on the

central government’s directives, thereby eliminating local authorities’ intervention

1 After the introduction of the Comprehensive Decentralization Law in 2000, agency delegation has been

abolished and its function divided into local government function and statutory trusted function, however,

central control remains in statutory trusted function (Kume, 2001).

2

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

(Tusjiyama, 1992). As such, the Japanese model may be classified as a “centralized”

type.

Since Japan’s intergovernmental allocation of functions is vertically done (Takahashi 1978,

p157), and it follows the agency delegation pattern, the Japanese system may be

characterized as the “interfusion” type.

1-3. Achievement of the National Minimum in Japan It was the agency delegation system that contributed substantially to achieving the

National Minimum in Japan. Since welfare administration was delegated to the Chief of

local government, and implementation was ruled out as national policy, the leadership

profile of the local Chief was raised in relation to his peers. (Kume, 2001)

In summary, the Japanese system of government is, according to Amakawa’s model, a

centralization-interfusion type. Its “centralized” character is visible where the decision-

making authority is reserved by the central government, even though most of its affairs

are delegated to prefectures and municipalities. At the same time its “interfused”

character is seen in the involvement of local governments in local affairs as well as the

affairs of the lower-class national institution (agency delegation). (Nishio, 1999).

In conclusion, Japan’s intergovernmental relations is characterized by two observations:

(1) heavy involvement or intervention by the central government, and (2) actual

involvement of local governments in their own affairs and services. In terms of the

National Minimum, its interfusion character, most importantly the agency delegation

system, has contributed much to its success.

2. Dissolution of the Bakuhan system and reforms by the Meiji Government

2-1. Dissolution of the Bakuhan system During a time in history known as the Tokugawa period, from 1603-1867, Japan was

governed by the ‘Bakuhan’ system. Tokugawa Bakuhu, the ruling party, did not have

direct sovereignty over the land (known as ‘han’), nor over the citizens (known as ‘seki’).

3

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

Thus, Japan was not considered a nation by modern definition. The Bakuhan system

was governed by one man (shogun) and his hundreds of coalition members, known as

the ‘Daimyo’.

In 1853 (Kyōei 6), a visit by American naval ships under the command of Matthew

Galbraith Perry, brought about the overthrow of the Tokugawa Bakuhu, which in turn led

Japan to be rebuilt as the modern nation it is today. In January 1867, (Keio 3), Emperor

Meiji ascended to the throne. By October of the same year, the last shogun, Tokugawa

Yoshinobu, returned sovereignty to the Imperial Court (this event is known as ‘Taisei

Hōkan’). By December 1867, the Bakuhan system was dissolved when the restoration of

imperial rule was announced.

After the overthrow of Tokugawa Bakuhu, political power was jointly held by Satsuma-

han and Chōshū-han, powerful Daimyos at the time. They regarded Emperor Meiji as

their national symbol and sought to build a centralized political system on par with the

western world. Although the new government had announced the restoration of imperial

rule, the ruling system remained practically unchanged. In January 1868, (Keio 4), in the

battle of Tobahushimi, the new ruling party defeated the former Bakuhu regime. Later, in

March of the same year, a meeting between representatives of the old and new regimes

was held, in which Katsu Kaishū (Bakuhu regime) and Saigō Takamori (new government)

agreed to open up Edo castle, previously the military base of the Bakuhu. In April 1868,

the Charter Oath2 was issued, revealing the new government’s ruling mandate. In

September, Meiji was chosen as the imperial era’s name, thus beginning the Meiji era

and its reforms.

In June 1886 (Meiji 2), an event known as the Hanseki Hōkan saw the return of all

Daimyo sovereignty over land and people to the imperial court. This reform stripped

Bakuhan power from the prefectures and established new ‘han’ prefectures, to be ruled

by governors. However, all 274 Daimyos from the previous era retained their titles as

governor, or ‘Chihanji’. In July 1871 (Meiji 4), the new government enforced ‘Haihan-

2 The Charter Oath was the tool to justify the creation of a modern nation by the new Meiji Government.

The contents of Charter Oath included five points : 1) Major political matters shall be discussed and decided

in accordance with public opinion. 2) All shall cooperate in governing the nation. 3) Leaders will endeavor

to engage the people. 4) Old habits shall be abolished and a right path shall be followed. 5) Intelligence shall

be searched throughout the world and the Emperor’s governance shall be promoted.

4

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

Chiken’, an event that abolished ‘han’ and introduced ‘ken’ prefectures. This brought

about the dismissal of Daimyos from their Chihanji positions and the appointment of

political activists of the Meiji revolution as governors. In principal, new positions as

governor were given to persons from different prefectures in order to ensure a clear

separation from the previous ‘han’ style of administration. By November 1871, the

number of prefectures was reduced to 75 (3 ‘hu’ and 72 ‘ken’)3. At the same time, the

government introduced an ordinance to control prefectures, in which each prefecture

was organized into four divisions — general affairs, judicial, taxation, and finance. This

helped to standardize staffing and allocation of local government employees across

different prefectures, as well as to allocate additional powers and responsibilities over

financial and political authority. For example, each prefecture was given a range of

internal political responsibility that included police authority.

Over time, it was evident that the Meiji reforms had transformed the old Bakuhan system

of government into a dramatically different, centralized system to establish control over

Japan.

2-2. Principle of state formation and central-local relations The Meiji Constitution of 1889 was put into effect during the pre-World War II period

(Meiji 22). About the same time, the Meiji Local Government System was introduced. It

formed a major component of the country’s nation-building principles. Hence, it is

necessary to understand the nation-building principles of the Meiji government in order

to appreciate the dynamics of the Meiji local government system. According to political

scientist Fujita Shozo (1927-2003), there were two distinct principles involved in

constructing pre-war national governments with an emperor at the helm. One was the

principle of the “power state.” The second was the principle of the “community state.”

The former sought to construct a nation as “the device for political power,” and the latter

sought to construct the nation as “an ordinary community in itself, whose foundation lies

3 Since then, the new government enforced mergers between prefectures almost every year. In 1876 (Meiji

9), the total number of prefectures went down to 39 (3 ‘hu’, 35 ‘ken’ and 1 ‘han’ (Ryukyu-‘han’)). These

mergers, however, invited rebellion, which led to a movement to divide prefectures. Gradually the new

government started accepting more prefectures, and in 1888 (Meiji 22), the number went back up to 47 (3 hu

and 43 prefectures), which has become the base number of the current prefecture system.

5

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

in community, or a nation that can be identical with the community”.4

It is difficult for these two principles to co-exist. However, it was imperative for Japan to

maintain a strong sense of Japanese identity in the heart of each citizen of its community,

yet it was also crucial to build a nation with a strong and rational system of government

in order to compete with developed Western countries. To deal with these challenges,

the Meiji leadership established the local government system as its vehicle for political

government.

Why was the local government system considered to be the effective vehicle to achieve

these political goals? In essence, its most important component was the Ministry of

Interior (‘Naimusho’), which represented the core of Japan’s central-local relations. This

structure represented the centralization-interfusion type. The Ministry of Interior, which

was installed in 1873 (Meiji 6), was not abolished until 1947 (Showa 22), after World

War II.

Designated as the ministry in charge of domestic affairs, the Ministry of Interior had two

main functions. Recalling the local government system of the Meiji era, it was a two- tier

system, the prefecture and the municipality. The first function of the Ministry of Interior

was to control the autonomous decision-making of prefectures and municipalities, as well

as to direct and supervise local administration. This coincides with the centralized style of

government.

The second function of the Ministry of Interior was to prevent other ministries from

performing special operations by creating local branch offices. To do so, all requests from

other ministries were subject to the scrutiny of the Ministry of Interior and the decisions

of its appointed governors. In this way, prefectures were organized like branch offices of

the central government. This fits into the interfusion type of central-local relations.

The interfusion style of central-local relations was an effective mechanism to convey

central government intentions all the way down to municipalities through its appointed

governors. At the same time, this mechanism had the added advantage of

understanding the actual conditions and interests of locals and reflecting these

4 Fujita Shozo ,“Tennoseikokka no Shihaigenri, The Ruling Principle in the Nation of Emperor System”,

Miraisha, 1996.

6

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

conditions and interests in its policy planning and operation. This mechanism was

possible because bureaucrats from the Ministry of Interior were positioned at the

connecting points of information and resources with regard to central-local relations

throughout the network.

The establishment of the local government system was recognized as a modernization

effort in transforming Japan from a nation ruled by an emperor into a competitive world

power5.

2-3. Features of the Meiji Local Government System Although the Meiji local government system had undergone several transitions following

a variety of legislative changes, there are some features worthy of note. In the Meiji

system, municipalities were recognized as having absolute local autonomy, yet they were

also required to function as national administrative organizations. In order to do this, the

“agency delegation system” was introduced, in which the central government would

delegate national administration functions to the chief of municipalities. The authoritative

entity that decided how and which national administration functions would be delegated

was the Central Ministries, headed by the Ministry of Interior. As a result, local

governments were denied the power to make autonomous policy decisions and, in this

sense, did not have an independent political status.

Under the general supervision of the Ministry of Interior, local government officials such

as governors and county chiefs instructed and directed local governments. These officials

came under a local government official system that governed their organization,

authority, and personal affairs. Imperial ordinances ruled over local government official

systems, independent of the Japanese Diet. In prefectures, governors appointed by the central government executed national

administration policy directly. Appointed governors had the authority to execute original

bills, but the Minister of Interior had the ultimate authority to dissolve assemblies.

Although municipalities could establish ordinances, prefectures could not do so. In

comparison with municipalities, prefectures had less of an autonomous character. It

5 It is meant to address the relationship between nation building principles and the pattern of central-local

relations, and so it is a different issue from praise that the pre-war Japanese national system had the right

foundation.

7

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

could be said that they had a sort of imperfect autonomy.

In Japanese urban areas, cities grew from ‘wards’ and were given the status of local

governments just like towns and villages. As towns and villages merged, the number of

cities kept increasing. City councils were formed. They were executive organizations

consisting of mayors, deputy mayors, and honorary council members. The Ministry of

Interior chose and appointed mayors from among three candidates nominated by city

assembly, which was the decision-making structure of cities. Village and town chiefs

were selected by indirect election in the town and village assemblies.

In the Meiji local government system, all males 25 years old and above who paid an

annual property tax or national tax of 2 yen or higher were recognized as citizens and

were distinguished from the other residents. Since citizens held elective power, and since

being a citizen meant being a rich landowner, the local government was, in practice, led

by local men of high reputation. It was not only a privilege for landowners but also a

duty for them to participate in local government. Other than the mayor, official positions

of local government were basically honorary posts with no pay. There was even a

punishment such as suspension of citizenship or additional taxes imposed on those

citizens who did not carry out this honorary role without a proper reason.

In the election for the local assembly, a system based on economic class was adopted. In

this system, all voters were categorized by the size of taxes paid and were divided into

groups (three groups at the city assembly level and two groups at the town and village

assembly level), such that the total amount of tax paid by each group would be the

same. This class-based election system clearly favored the rich, as an equal number of

assembly members were elected from each group. This meant that candidates of the

group with the wealthiest voters stood the highest chance of election. Elections in the

prefectures and county assemblies took the form of an indirect election.

Lastly, in the three largest cities, Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto, a unique system was applied.

In these three cities, the appointed governor also acted as mayor, and the secretary also

acted as deputy mayor. The reason that this irregular system was introduced in these

cities was due to a desire for tighter control, since the rate of movement and change in

the growing cities was deemed to pose a greater threat to the central government.

8

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

2-4. Changes in the Meiji Local Government System Over time, the local government system underwent multiple changes and evolutions

throughout the Meiji era. Each change was introduced to reflect social, political and

economic realities. Some of these changes followed the gradual emergence of party

politics, the birth of the universal suffrage system, changes in the subsidy system due to

urbanization and industrialization, and the introduction of a local allocation tax system.

2-5. Emergence of Party Politics and the universal right to vote One of the first changes took place after the adoption of the Meiji Constitution. The

oligarchy led by political activists of the Meiji revolution and bureaucrats from ‘han’

factions were gradually sidelined, and a gradual democratization was introduced with the

emergence of party politics and the growing electoral power of the people.

The latter half of the Meiji era was characterized by a period of power play. In the

Cabinet, it was clear that two political parties, the ‘Seiyu kai’ and non-‘Seiyu kai’ would

take turns holding cabinet power. By the Keien-era, it was evident that the Ministry of

Interior and appointed governors had begun to assert their political views. In 1893 (Meiji

26), a civil official appointment system was introduced. This was a merit system by

which public management officials were selected from among those who successfully

passed the “advanced examination for civil officials.” In 1899 (Meiji 32), the civil official

appointment system was revised and expanded. Officials who were previously appointed

by imperial order were now required to pass the advanced examination and be

recommended by the prime minister before being appointed by imperial order. This

revision strengthened the merit system and prevented political parties from misusing the

role of appointed governor for political means. However, it was not as effective in

preventing power plays within the cabinet. Activities inside the cabinet were rife with

personnel manipulations by high-ranking civil bureaucrats for political reasons. Traditionally, voting rights were limited to landowners and the rich. However, this

restriction was gradually relaxed to include more people by lowering tax requirements.

By 1925 (Taisho 14), this limitation was completely abolished, thereby giving all males 25

years old and above the right to vote. Thus, a universal electoral system was born.

In this political environment, the local government system was further revised and given

more autonomy. This time, counties (which were considered territories between the size

9

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

of prefectures and municipalities) were abolished, thereby removing a distinction in

character between prefectures and municipalities. Indirect election in prefectures was

also abolished, along with the class-based election system. At the same time, voting

rights at the local government level were extended to more citizens. In the reform of

1929 (Showa 4), local assemblies were also given the right to propose ordinances, and

prefecture assemblies were given the right to establish ordinances.

2-6. Changes in the subsidy system and introduction of the local allocation tax system Other changes were introduced for financial reasons. Due to urbanization and

industrialization, the financial gap widened between regions. This situation was

especially severe in the agricultural districts.

In the Meiji local government system, the main source of local revenue came from

public property. When funds were insufficient, rent and commissions were used to

supplement local revenue, and in the worst case, tax revenue was used. After the Meiji

reforms that resulted in the merger of towns and villages, public property owned by the

towns and villages remained in a status quo, and were not available to the local

governments as extra revenue sources. As a result, in those agricultural districts that

tended to be slow in economic development, the local government had to utilize taxes as

the main source of revenue. On the other hand, their delegated tasks from the national

administration were increasing, generating expenses within the agricultural district that a

local government with poor revenues could not cover. This resulted in a risk of gradual

paralysis to these delegated tasks and their local administrations.

As a result, the central government was forced to seek a new policy to adjust the

revenue imbalance between itself and local governments. To start with, the national

subsidy was increased. Among the key national subsidies, the Law concerning the

National Treasury's Share of Municipal Compulsory Education Expenses (1918) was

evaluated. This is the system in which a national subsidy is distributed to municipalities

in accordance with the number of teachers and students. In the case of municipalities

with poor sources of revenue, a special allotment was arranged. In this way, the national

subsidy helped to balance local finances to some extent.

Next, there were attempts to change the allocation of funds between the central and

10

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

local governments. From the Taisho era to the beginning of Showa era, the ‘Seiyu-kai’

had supported the idea of giving tax revenue from both land and business to the local

government. In 1929 (Showa 4), the ‘Seiyu-kai’ Cabinet led by Tanaka Giichi made this

tax revenue proposal to the Diet, but ‘Minsei-tou’ turned down the proposal. The

explanation was that such a proposal would not only reduce national tax revenue but

also worsen the unbalanced financial situation among local governments. In 1931

(Showa 6), the Manchurian Incident occurred, throwing Japan and China into the

quagmire of war. In 1940 (Showa 15), in the middle of this war, a local distribution tax

system was established. It consisted of a tax refund and a distribution tax. The tax

refund component would return land tax, estate tax and business tax to the prefectures

where these tax revenues had originally come from. The distribution tax component

would transfer a certain portion of the revenue from national taxes, such as income

taxes and corporate taxes, to local governments. This was a fiscal equalization system

that laid the foundation for the current local allocation tax system.

At the end of 1941 (Showa 16), Japan was plunged into the Pacific War. In 1943 (Showa

18), local system reforms adopted a shift to centralization in place of the on-going idea

of increasing local autonomy. Tokyo city was abolished and became Tokyo metropolis

(Tokyo-to), and the control over this locality became tighter compared to other

prefectures. Further, Japan was divided into nine regions and council for local

administration was introduced. The members of the council for local administration were

the governors and chiefs of branch offices of central ministries. The Prime Minister

appointed one of his governors to head the conference, and gave him authority over the

other governors and chiefs. In June 1945 (Showa 20), once it became obvious that

Japan was going to lose the war after the United States landed in Okinawa, Office of

local Superintendent-General, which had more authority than the council for local

administration, was introduced in order to prepare the country for battle on Japanese

territory. It was recognized as an authority higher than governors and branch offices of

central ministries. Before this system became fully functional, in August, Japan lost the

war.

3. Local System Reforms under the U.S Occupation World War II ended on August 15th, 1945, after the unconditional surrender of Japan.

During the next seven years, Japan was subject to a U.S. led Occupation that brought

11

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

about drastic reforms in various areas, including politics, administration, the economy,

and education. The impact of these reforms, measured by their size, content, and effect

on the Japanese way of life, was said to be as significant as that of the Meiji Revolution.

It was as if Japan had experienced two revolutions within a span of merely 80 years. In

the following paragraphs, these topics will be discussed: the impact of Occupation

reforms on the local government system, the Shoup recommendations, and what was

left of the pre-war centralized system of local government.

3-1. Post-war Changes in Central-Local Relations (1) Reforms under Occupation and the New Constitution System General Douglas MacArthur’s General Headquarters, (GHQ) was the agency in effective

control of the U.S. Occupation immediately after the Japanese surrender. The GHQ

issued a “Five-Points Reform Order,” with the basic goals of demilitarizing Japan and

making it a democratic nation. The five major reforms involved the following:

• Emancipating women and giving them the right to vote

• Protecting labor rights and recognizing labor unions

• Liberalizing and democratizing school education

• Abolishing the secret police and emancipating citizens from autocracy

• Democratizing the Japanese economy

Reforms made to the local government system were primarily shaped by the Constitution

of Japan, which was drafted with major involvement by the GHQ. In particular, Chapter 8

of the Constitution, “Guarantee of the local government system” was of major

significance to the local governments. The pre-war Imperial Constitution had made no

mention of the local governments, except for indirect references to the Emperor’s

authority over administrative organizations and the appointment of local officials. The

structure of the pre-war local government system had been simply based upon the

accumulation of separate, individual laws that covered such matters as municipal

organization, town and village organization, prefecture organization, and the

appointment of local government officers. After World War II, in accordance with the

provisions of the Constitution, Japan's local governments gained broad recognition of

their autonomy and self-standing, both at the formal level and at the operational level in

terms of their actual dealings with the central government. For instance, Section 92 of

12

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

the Constitution states that the operations of local public entities shall be fixed by law, in

accordance with “the Principle of Local Autonomy”.

The “Principle of Local Autonomy” defines the existence of a local government based on

two factors, group autonomy and resident autonomy. Group autonomy ensures that the

politics and administration of local areas are controlled by a local group independent of

the rest of the country. Resident autonomy refers to the decision-making power

controlled by residents of the local area. It has been evident that the Principle of Local

Autonomy was effective in decentralizing the relations between the central government

and prefectures/municipalities. The post-Constitution central government, prefectures,

and municipalities were operated as independent governments whose authority was

controlled by resident-representatives who bore a direct responsibility to the citizens and

to all residents. Another post-war change was in the area of citizens’ (komin) self-government. Previously,

citizens of autonomous local areas participated in and handled, to varying degrees,

activities of the local public entities. After the war, the concept of citizens’ self-

government was changed to one of residents’ self-government. The Local System

Revision in 1946 and the implementation of the Local Autonomy Law in 1947 both

contributed to this change. In accordance with the national change from the Emperor’s

sovereignty to citizen sovereignty, the discrimination between citizens (komin) and

residents was abolished. Residents (which embraced a larger proportion of the

population) were then invited to participate to a greater extent in local government

management.

(2) Three Points of the Local System Revision The post-war Occupation reform brought about a shift in the Japanese local government

system from an extremely centralized operation to a more decentralized one. In

particular, three specific points ranked among the important changes to the local system.

i. Complete autonomy in Prefectures This was achieved through the introduction of a publicly elected governor in place of an

appointed governor, and recognizing all prefecture staff members as local public service

workers.

13

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

The introduction of publicly elected governors was particularly important. Before this

reform, the governor was appointed by the Ministry of Interior (MoI). The pre-war

prefecture governor used to function more like a national secretary for local

administration rather than as a representative of local residents. Under the revised

system, the governor was publicly elected by local residents, thus not only affecting his

public status, but also the prefecture’s role in central-local relations.

The initial draft for revision of the prefecture system proposed by the MoI recommended

the introduction of public elections and terms of service for a governor. However there

had been no intention to change the prefectures’ basic character, as evident from the

MoI’s suggestion to give governors the status of national public officials. When the

Ministry of Interior’s proposal went up for discussion, the issue of a governors’ status as

publicly elected national officials inadvertently became a focus of discussion. In the end,

Chapter 8 of the New Constitution prevailed, i.e., that the chief officer and the members

of a local public body were to be directly elected by residents. The MoI’s proposal was

thereby revised, maintaining the status of national officials until the New Constitution

took effect. After all these changes, prefectures that once had the character of national

general branch offices became fully recognized as local autonomies.

With the change in the autonomy of a prefecture that abolished its character as a

national general branch office, a new problem arose – the question of dealing with

national administrative affairs. One of three solutions could be adopted. The first was to

establish a new general branch office in place of prefectures. A second proposal was for

individual branch offices of central ministries to deal with national administration issues.

The third option was to entrust national administration to prefectures as if they were

completely autonomous. A task force within the Cabinet looked into establishing a ‘Dō-

shu-sei’ system, (meaning a wide-area administration system that merged existing

prefectures into 7 or 9 do or shu) for the first proposal. Central ministries (other than the

MoI) initiated the setting up of a central branch office in response to the second

proposal. A third task team, led by the MoI, evaluated the possibility of expanding the

agency delegation system to the prefecture level in order to adopt the third proposal. In

the end, the establishment of the Local Autonomy Law enabled the agency delegation

system to be extended to the prefecture governor, thereby allowing the prefecture to

continue dealing with national administrative affairs.

14

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

In summary, prefectures in the post-war period were reborn as complete autonomies,

but were never freed from the responsibilities of national administration.

ii. Dismantlement of the Ministry of Interior The status of the MoI diminished with the increase in prefectures’ autonomy. At the

same time, the influence of other central ministries grew stronger. These changes were

brought about by the implementation of the Local Autonomy Law, by which the chief of

municipalities and the governors of the prefectures were given expanded roles as branch

offices of central ministries under the agency delegation system.

The reform policy of the GHQ also accelerated the decline of the MoI’s status. As soon as

the Local Autonomy Law was established, the Civil Affairs Division of the GHQ requested

the decentralization of the MoI. Two reasons were given to support this request: firstly, it

considered the MoI to be at the center of the existing centralized system in Japan.

Secondly, it considered the police system to be a vehicle of totalitarianism (the police

system was under the direct control of the MoI).

At that time, in the midst of these changes, there was no evidence that the MoI was

contemplating reforms to its existing organization. The MoI was content to maintain its

role as guardian of the local government entities. It considered that its key

responsibilities were to maintain jurisdiction over local government systems and local

finance systems at the national level, and to represent the opinions and interests of local

governments at the national administration level. At the same time, the MoI feared that

complete autonomy of prefectures would pose an obstruction to its own comprehensive

administration, since it would encounter stronger influence from other ministries,

resulting in more branch offices to deal with.

Meanwhile, the Cabinet established the Administrative Research Board, which began a

study to consider a new central administrative arrangement that fit better with the new

Constitution. In this study, the re-alignment of the MoI, at the request of the Civil Affairs

Division of the GHQ, was discussed. The MoI’s initial proposal for decentralization was

rejected by the GHQ’s Civil Affairs Division on the basis that the proposal carried no real

changes besides revisions of the names of divisions within the MoI. Some time later,

under the supervision of the Administrative Research Board, the idea of dismantling the

MoI was raised, which began to shape discussions about separating each division from

the MoI. Upon the approval from the Civil Affairs Division of the GHQ, a legal document

15

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

was drafted to develop a new organization based on this idea. In this draft however,

details for decentralization of the police system was omitted. But the Civil Affairs Division

of the GHQ intervened by drafting a police decentralization bill in consultation with the

U.S. Department of Justice and obtained its approval within the GHQ. Although there

was intense opposition from the General Staff Office, MacArthur, the Supreme

Commander for Allied Power, sent an order for the reform of the police system directly to

Prime Minister Tetsuya Katayama.

Two schools of thoughts existed within the GHQ with regard to the police system. The

first school adopted an aggressive approach in its attempt to institute the Occupation’s

reforms and conclude a peace treaty as soon as possible. The other school attempted to

place greater importance on maintaining Japanese security during the cold war era. This

disagreement over the police system put a halt to the MoI’s reform plan, only to result in

a series of drastic reforms later. In the midst of the police controversy, discussions in the

Diet on the draft to dismantle the MoI had to be curtailed, only to be rewritten later in

order to reflect the more drastic reforms.

The Ministry of Interior was finally dismantled in December, 1947. It was broken down

into the Ministry of Health, Ministry of Labor, Ministry of Construction, Ministry of Home

Affairs, National Public Safety Commission, and National Police Agency.

iii. Establishment of Local Autonomy Law The Local Autonomy Law (LAL) was promulgated on April 17th, 1947. By May 3rd, the

LAL was put into effect along with the new Constitution of Japan. At this time, all

previous laws and ordinances that related to local administration since the Meiji era were

abolished. This effectively led to the demise of separate governance through several pre-

war local systems (where the city system, the town and village system, and the

prefecture system were separately governed by individual laws), in favor of a collective

law to deal with the organization and management of local autonomies. The LAL became

the general law relating to all Japanese local governments.

The LAL provided local autonomies with greater recognition and self-standing by

empowering the local residents based on the principles of self-rule and self-responsibility.

This meant that local residents would determine local administration matters by

themselves (self-rule) on their own behalf (self-responsibility). The new law stipulated a

dual representation system, in which the chief and the assembly members were to be

16

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

publicly elected, and each functioned independent of the other. The chief was expected

to operate in the capacity of an executor, whereas the assembly was expected to operate

as decision maker. Although both functions appeared to operate independently of each

other, the chief had the authority to dissolve the assembly and the assembly in turn, had

the authority to overrule the chief by a vote of no-confidence. In this sense, the new

system bore a similarity to the Diet Cabinet system, but, at the same time, it adopted a

democratic approach by giving residents the rights not only to re-elect a chief and

assembly members, but also to indirectly to dissolve an assembly.

The establishment of the LAL as a general law eliminated a failing of the pre-war system,

which had allowed for different levels of local autonomy. In the pre-war system, local

governments were overly centralized and suffered loss of their autonomy. Under the

new law, the local autonomy was guaranteed by the new Constitution, and was

recognized as the basis for democracy. However, the new law was criticized for its lack

of flexibility. Critics cited the hurried manner in which the LAL was put together following

a series of snap decisions, hence little attention was paid to the diversity of autonomies.

For example, the LAL was so standardized that it overlooked the differences between

prefectures and municipalities. Although prefectures were said to involve municipalities,

the LAL regarded both as general local public bodies, with no mention of their

differences.

3-2. Further issues (1) The Shoup Report As mentioned before, the post-war reforms introduced by the new Constitution broke up

the pre-war local administration system in which the Ministry of Interior and prefectures

had been core centers of leadership. Establishing a new local administration system to

replace the MoI and prefectures remained the outstanding issue to be resolved. At that

time, a research group (the Shoup taxation research group) was visiting Japan to

promote the Dodge Line Policy of government retrenchment and a balanced budget 6.

What followed was the issuance of the Shoup Report in 1949, which recommended two

reform principles to address local financial concerns. The first recommendation

6 Economic Policy of retrenchment finance and a super balanced budget conducted in 1945-50. This was

guided by Dodge J.M, GHQ’s economic and finance advisor, based on 9 principles suggested by GHQ in

December 1948.

17

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

attempted to clarify the work and responsibilities of a three-layered government (central

government, prefectures, and municipalities) in order for taxpayers to understand their

responsibility and benefits. The second recommendation tried to institute municipalities

as the core center of local government, on the basis of their proximity to residents.

Soon after the taxation reforms based on the Shoup recommendations commenced,

problems arose. For example, prefectures and municipalities got into disputes over the

allocation of local tax income. A related issue of contention was the introduction of a

local finance equalization grant to replace the distribution tax revenue. Following the

rejection of a two-layered division of government (one to administer national affairs and

the other to administer local affairs) and the abolition of the national subsidy, a local

finance equalization grant was introduced to ensure that local governments had

sufficient finances. However, because the equalization grant was completely dependent

on the budgetary process, it often ended up not making up the insufficiencies of local

finance, hence rendering the equalization grant ineffective.

In addition to taxation reforms, the Shoup Report recommended the redistribution of

public services. The Investigation Committee of Local Administration, also known as the

“Kobe Committee,” was installed to look into this recommendation. The Kobe Committee

produced the Kobe Recommendation in 1950, which focused on two issues, the

improvement of work efficiency and the provision of higher priority to municipalities. It

also proposed that municipalities should be merged to raise their autonomy, in order to

take care of higher volumes of work.

When the Shoup Report was introduced, there had been widespread anticipation that

the end of Occupation control and the conclusion of a peace treaty was near. As

expected, in 1951 the Allied Powers signed the Treaty of Peace with Japan at the San

Francisco Peace Conference. Soon after, a sense of nationalism grew in Japan. It sought

to restore what existed before the period of Occupation. This quickly led to the

unpopularity of the Shoup recommendations (whose basic philosophy differed from the

traditional Japanese system) and the Kobe recommendations (which were based on the

Shoup anyway). Only a handful of reforms, like the merger of towns and villages and the

local finance equalization grant (later redesigned as the local subsidy), were completed

and remained.

18

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

(2) Succeeding the centralization system of the pre-war era Although the Japanese local government system underwent several reforms under the

Occupation, the pre-war centralized style of government was not completely gone. Nishio

Masaru (2001) cited three areas that remained centralized even after the Occupation

reforms.

1) First of all, the authority of local governments remained unclear, due to vague

declarations provided in the Constitution. Therefore some entities were not fully

decentralized.

2) Secondly, local government had been operating as local branch offices of central

ministries right up to the Occupation. The agency delegation system was

introduced to prefectures after the practice of appointing local government

officers was abolished and prefecture governors were stripped of their role as

national executives of local administrations. Agency delegation was originally

intended for pre-war municipalities, but was eventually extended to prefectures.

Consequently, the executive function of prefectures (governor), and the

executive function of municipalities (mayor), were both used as part of the

executive arm of the central government.

3) Thirdly, a control and supervision structure still existed between prefectures and

municipalities. This was due to the responsibilities given to prefectures to control

and supervise the municipalities’ execution of work on behalf of the central

government. At the same time, municipalities were required to go through

prefectures in their communications with the central government, thereby

providing prefectures with a wider control over the municipalities.

4. Economic growth and Central-Local relations From the post-war years through the 1980s, the Japanese economy had experienced

remarkable growth. It continued until the economic depression of 1990. Among the

various reasons for the steady growth was the role of the central government. It has

been a known fact that Japanese spending on public works far exceeded that of other

countries. As a result of this spending, Japanese infrastructure was established to

support the high rate of growth of its economy. In this chapter, the relationship between

the central government and local governments will be discussed in relation to Japanese

public works.

19

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

4-1. Emphasis on planning In Japan, public works are systematically planned on a national scale. All master plans

relating to public works are subject to approval by the Cabinet. They are carried out at

the national level. Examples of national master plans include the Income Doubling Plan

of 1960, the First Comprehensive National Development Plan7 of 1962 (First CNDP), the

Second Comprehensive National Development Plan of 1969 (Second CNDP), the Third

Comprehensive National Development Plan of 1977 (Third CNDP), the Fourth

Comprehensive National Development Plan of 1987 (Fourth CNDP), and the Grand

Design for the 21st Century of 1998.

The Income Doubling Plan, as its name suggests, aimed to double national income by

reaching a Gross National Product (GNP) of JPY26.0 trillion within 10 years from the

1960 level of JPY13.0 trillion. In order to achieve this goal, the GNP was expected to

grow at 9% per year for the first 3 years to reach JPY17.6 trillion by 1963. By way of

background to understand this strategy for growth, it should be noted that this plan was

implemented during a time of rapid technological revolution in Japan and an abundant

labor supply. Thus it was considered an appropriate policy, which drew on strong

cooperation from its citizens. The plan focused on the modernization of agriculture, the

growth of small and medium-sized enterprises, the development of the underdeveloped

regions, re-arrangement of industries, and distribution of public works in different

regions.

In each of the four CNDPs, the objectives and strategies were laid out to reflect changes

applicable to each period. For example, in the First CNDP, the key objective was to

achieve a balanced, nationwide development by developing certain regional zones. In

the Second CNDP, the key objective was to create a robust environment employing the

strategy of large-scale construction projects. The objective of the Third CNDP was to

provide self-contained, quality environments where people lived. Improving

neighborhoods was seen as a way to support the industrial development of earlier plans.

The Third CNDP also dealt with issues of under and over-population. In the Fourth CNDP,

the goal was a well-designed national land with multi-polar structure (referring to land

with multiple core areas). The strategy was to construct nationwide exchange networks

7 All the explanation about Comprehensive National Development Plan in this chapter are sourced from

Honda Hiroshi, Shimojo Michihiko, “Local Government under decentralization, Kouninsha, 2002

20

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

relating to transportation, information, and communication systems. Finally, in the Grand

Design for the 21st Century, the formation of multi-axial national land structures

(referring to land with diverse core zones) was the key objective. In order to achieve this

objective, its strategy was widened to encourage cooperation between neighboring

regions and to draw participation from the private sector, citizens and volunteer groups.

4-2. Public Infrastructure (Public Works) and economic growth Economic growth is closely related to the standard of a country’s infrastructure. It is

typically the responsibility of the public sector to provide for society’s need for good

general infrastructure, since the profit motive from the supply of infrastructure is low.

Public infrastructure (or public works) is considered a significant foundation for economic

growth. To meet the public objective of achieving a higher standard of urban

infrastructure, the central and local governments had to work together to establish a

systematic development plan for public works relating to roads, ports, sewerage, and

embankment (flood control). Public works can be divided into two categories, foundation

for industry and foundation for living. Foundation for industry would include public

facilities with production and distribution functions, such as factory sites, industry water

supply, roads, railroads, airports, and ports. Foundation for living would encompass

facilities such as housing, schools, hospitals, welfare facilities, streets, sewerage, and

parks. Public works are further divided according to four jurisdictions, or areas of responsibilities

- public works under the jurisdiction of the national government, public works under the

jurisdiction of the local government with partial support from the national government,

public works under the sole jurisdiction of local governments, and, lastly, the public

corporations, such as the Japan Highway Public Corporation.

The most fundamental plan for public works is the “Central National Development Plan”

(CNDP), which outlines an overall, long-term plan for Japanese public works. On the

operational level, mid to long-term plans are formulated by each ministry and bureau

(government level) that is assigned responsibility over individual construction projects.

Examples of such mid-term plans include the 5-year Road Construction Works Plan, the

5-year Port Construction Works Plan, and the 5-year Airport Construction Works Plan.

21

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

Public works are funded by three main sources - national finance (from the General and

Special Account Budgets), the Fiscal Investment and Loans Program (FILP), and local

finance. National finance refers to the national government budget, which consists of the

General Account budget and 31 Special Account budgets. Revenue for the General

Account budget comes from tax income, non-tax income, and national bonds. Revenue

for the Special Account budgets comes from ear marked tax, non-tax income, and

transfers from the General Account budget. The Special Account budget is three times

larger than the General Account budget, and correspondingly, its involvement with public

works funding is larger. The funds for FILP are sourced mainly from tax and non-tax

income and national bonds, and among these, postal saving and non-tax income are

used quite substantially. The source of revenue from the local budget originates from

local taxes, local allocation tax, grants or subsidies, and local bonds.

In terms of expenditure on public works, it has been kept at an average of 20% of

general expenditure (Table 1). The largest share of public works-related expenditure

goes to road projects (Table 2).

Table 1: Components of General Expenditure

(Unit: %)FY1965 FY1975 FY1985 FY2000

Social Security 17.8 24.8 29.4 34.9Public Works 25.1 18.4 19.5 19.6Education & Science 16.3 16.4 14.9 13.6Defense 10.3 8.4 9.6 10.3Economic Assistace 0.9 0.6 1.8 2Food Supply 3.6 5.7 2.1 0.5Energy - 1.2 1.9 1.3Others 26.0 24.5 20.8 17.8Source: "Picture of Japanese economy", Miyazaki Isamu, Honjo Makoto, 2001, Iwanami B

22

MODULE Inter governmental relationship

Table 2: Changes in Public work-related expenditures

(Unit: %)Public work-related expenditure FY1980 FY1985 FY1990 FY1994Foresty and Flood Control 16.2 15.7 15.6 16.6Road 28.6 26.8 25.7 26.2Ports/Harbor, airport 7.8 7.4 7.4 7.2Housing 11.4 13.6 13.2 11.7Sewage system and waste management 14.2 14.1 13.8 16.6Agricultural Development 13.2 12.8 12.5 13.3Water supply for foresty and industry 2.6 2.4 2.3 3.3Adjustment 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.1Recovery from disaster 5.7 7.0 9.4 4.9Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0Srouce: "Public works and decentralization", Kato Ichiro, 1998, Nihon Keizai Hyoronsha

There are three main effects of public works on an economy: economic growth, regional

development, and reduction of social costs. Firstly, public works have the effect of

stimulating economic growth by job creation due to their nationwide scale and their

requirement for large capital investment. Secondly, public works improve regional

development by providing a uniform standard of public infrastructure to be achieved

across all local governments. Aside from ensuring full utilization of local government,

public works projects also foster stronger support and cooperation between the

governments, enabling them to provide public services in a well-planned manner. In this

way, the central government was able to employ its policies to direct local governments,

an example being the use of the subsidy system. By employing the subsidy system

(instead of the local allocation tax), the central government was able to specify the

usage of subsidies directly in accordance with national policy. Recently however, this

same centralized character has brought the subsidy system under heavy criticism and

subject to being a target for reform (Trinity Reform). Thirdly, public works can have an

impact on social reform, since the improvement in the level of infrastructure will

contribute to reducing social costs by improving the quality of people’s lives.

23