Structural Change in the Sierra Leone Protectorate

-

Upload

kenneth-little -

Category

Documents

-

view

220 -

download

1

Transcript of Structural Change in the Sierra Leone Protectorate

International African Institute

Structural Change in the Sierra Leone ProtectorateAuthor(s): Kenneth LittleSource: Africa: Journal of the International African Institute, Vol. 25, No. 3 (Jul., 1955), pp.217-234Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the International African InstituteStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1157103 .

Accessed: 15/06/2014 18:02

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Cambridge University Press and International African Institute are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,preserve and extend access to Africa: Journal of the International African Institute.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

AFRICA JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL AFRICAN INSTITUTE

VOLUME XXV JULY 195 5 NUMBER 3

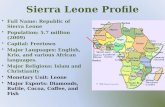

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE'

KENNETH LITTLE

N recent centuries indigenous West African society has experienced the impact of two external cultural forces, the one personified by Moslem invaders and migrants

from the north, the other by European colonists from the West. With the spread of Islam, the way of life of whole peoples has been largely transformed, but the main

changes which have occurred in the structure of African society are the result of Western and Westernizing influences. It is the purpose of this article to examine a

particular aspect of these structural changes which is exemplified by the appearance of a new class of ' educated' and 'literate' individuals and their relationship with traditional society in the Sierra Leone Protectorate. The Protectorate, with which this article is exclusively concerned, comprises the hinterland of the Sierra Leone Colony, and is under a Native Authority system of government. In the Colony, political and

legal institutions are modelled mainly on the English system. As explained later, the terms ' educated' and ' literate' are used throughout to denote relative degrees of Westernization due to education.

The Protectorate has a population of some 2 millions, of whom the overwhelming majority are persons born in a traditional culture. The principal peoples are the Mende and the Temne, numbering respectively some 586,ooo and some 505,6o0. Members of these and other tribal groups are described officially as ' natives' to

distinguish them from 'non-natives '. 'Non-natives' include some 400 Europeans, some I,ooo Lebanese,2 and some 2,000 Creoles.3 The Europeans are principally government officials, missionaries, and mining engineers, the Lebanese mostly traders and their families, and the Creoles are mainly employed in government departments, or are in trade. All three groups are distinguished by their Western way

I Most of the material for this article was gained 2 Popularly spoken of as ' Syrians '. during return visits to Sierra Leone made in the 3 Census of the Colony and Protectorate of Sierra summers of 95 2 and 1953 with the aid of grants, Leone, I148. The population of the Colony comprises which I gratefully acknowledge, from the Carnegie some 570 Europeans, some 28,000 Creoles, some Trust for the Universities of Scotland and the Social 830 Lebanese and Syrians, and some 87,500 Protec- Sciences Committee of Edinburgh University. torate-born persons (ibid.).

'Africa', the Journal of the International African Institute, is published by the Institute, but except where otherwise stated the writers of the articles are responsible for the opinions expressed.

Q

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

218 STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE

of life from the mass of the native population engaged in rice-farming, the Creoles self-consciously so. These people are the descendants of Africans liberated from the

slave-ships and settled in villages in the Colony during the middle years of the last century. This Colony community was heavily indoctrinated with Western religious and social values, with the result that Creoles have generally regarded themselves as

representatives of' Civilization' in West Africa.

THE CULTURAL ROLE OF THE CREOLE

Although Europeans are the politically superior class, it is the Creoles who have been mainly instrumental in spreading Western ideas and ways in the Sierra Leone hinterland. They have been active there for over a hundred years. Long before the declaration of the Protectorate they were busy evangelizing and trading and, when the British took over in 896, Creoles provided most of the clerks for the Administra- tion and many of the interpreters and other intermediaries between Europeans and native society. For many years, therefore, it was they who set the standard for native

people aspiring to a more modern way of life. This process of' creolization 'included the taking of European names in place of native ones, the speaking of Krio-the Creole tongue, the profession of Christianity accompanied by assiduous attendance at church and at church meetings, the use of' marking rings ' and engagement Bibles in the preliminaries of marriage, and, among women, wearing the hair straight instead of in plaits.

In the absence of close relationships between Europeans and the rising class of educated native people, Creoles have also supplied much of the social leadership. They have been active in founding athletic associations and social clubs as well as churches, and it is mainly in Creole homes that the subtleties of European 'drawing- room' behaviour and table manners are learnt by other Africans.' In these con- nexions perhaps one of the most significant practices which Creoles have propagated is that of assembling in public and mixing with persons outside one's own kin-group for purely social and recreational purposes. In traditional culture, people only go out of their homes or meet in public for some fairly specific religious, economic, or other reason and, once the matter is over, they disperse. For example, large crowds collect for prayers at the end of Ramadan, but a person walks straight to the ' praying-field ' and straight home; he does not mix with anyone but his own relatives on the way. Afterwards, he meets and exchanges presents with other kinsfolk, but this is done at each other's homes and not in public.

This dominance of the Creole as arbiter of form and fashion has lasted to the present day, although, with the political development of the Protectorate, there are signs of its waning. Not only has the Protectorate now a large majority of members in the

Legislative Council, but the Sierra Leone People's Party-at present in charge of the

government of Sierra Leone-is controlled by Protectorate-born individuals. Creoles still hold a large number of senior posts in the Protectorate Administration and in the

For a fuller account of the Creole's role as a ch. xiii; also my article,' The Significance of the West cultural medium see my book, The Mende of Sierra African Creole for Africanist and Afro-American Leone (Routledge & Kegan Paul), London, I95I, Studies', African Affairs, xlix, I950, pp. 308-19.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE 2I9 medical and technical branches of the Service, but there is an increasing challenge from educated Protectorate-born individuals. Most of the latter group have been educated at Bo School. Bo School was originally designed for the sons of chiefs, but was subsequently reorganized as a secondary school open to all classes. Its pupils take British school-leaving examinations, and it has had an enrolment of over a hundred for several years. A smaller number of Protectorate boys receive a secondary education in Colony schools, and there are post-primary facilities for girls at a school run by the E.U.B. Mission in the Protectorate. The training of Protectorate-born men and women as teachers is undertaken by several institutions including Fourah Bay College, and a number of Protectorate people have studied law and medicine and attended universities in Britain and North America.

THE EDUCATED CLASS

The result is that there are now several thousands of' educated' native individuals' living and working in the Protectorate. They are mostly clerks in government offices and in the branches of the large overseas mercantile firms, and teachers in Government, Mission, and N.A. Schools. There are also dispensers and nurses, technicians on the railway and in the mines, secretaries to District Councils, a few ordained clergymen, and perhaps some twenty Paramount chiefs. Others are farmers and traders, and there are a few lawyers and doctors. The nature of their jobs obliges most educated people to live in towns on the railway line which are the principal commercial and administrative centres; and Bo, which is the largest and most im- portant town in the Protectorate, has a far greater number of educated people than any other place.

Apart from the fact that they do not earn their living in traditional occupations on the land, these individuals are distinguished as a socio-cultural group from the rest of native society in a number of ways. In the first place, they have on the average a much higher standard of living as measured in monetary terms: even a junior clerk probably earns at least four times as much money during the year as a person working on a farm. The latter probably lives in a native-built hut of wattle-and-daub, whereas most educated people have houses of the stone and concrete type or mud houses of modern design which are decorated in a European style and equipped with a variety of manu- factured articles, including carpets, pictures, and wireless sets. Educated people also possess such things as a full set of crockery and cutlery, books, &c., and some of them have motor-cars. Their outlook, as well as many of their general habits, is also largely Western. For example, whereas most of the Protectorate population are either Moslems or pagans, most educated people profess Christianity. They attend the churches of the Methodist, Roman Catholic, and E.U.B. Missions fairly regularly, and for this and for certain other occasions both men and women usually wear formal clothes of a European kind. For ordinary purposes, however, the women generally prefer African-style clothes and the men a shirt and shorts, though they sometimes

' Educated ' is used specifically throughout the present moment some 530 children are enrolled at text to denote individuals with a post-primary educa- Junior Secondary and full Secondary Schools in the tion. Their exact number is guess-work, but at the Protectorate.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

220 STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE

put on a native gown for ceremonial occasions.' Educated people also take part, along with Creoles, in such recreational activities as card games, tennis, ballroom

dancing, listening to travel talks, and needlework.

THE LITERATE CLASS

In addition to this educated section of native society there is another and much

larger Westernized section, whom it will be convenient to characterize as ' literate '.2

For sociological purposes this term covers not only individuals who have attended a

primary school but anyone who can speak and understand English without neces-

sarily being able to read and write it. This group is also congregated mainly in the

railway-line towns and their neighbourhood, where most of them earn their living as assistants in stores, clerks to N.A.'s, primary school teachers, messengers, police, male nurses, lorry owners and drivers, contractors, and in a large variety of semi- skilled jobs in government departments. There are also a number of literate chiefs and individuals holding chiefdom offices who combine farming and trading with their

political duties. Literate people are distinguished from the mass of non-literate tribal society in

much the same way as is the educated group. Besides having a relatively higher standard of living they also tend to dress in European fashion and to be interested in

European forms of recreation, particularly football. The difference between them and the educated class is largely one of degree. A larger proportion of the literate

group is Moslem rather than Christian, and among Christians monogamy is less

strictly regarded. Literate people are also ' creolized ', but less so than educated

people, and they tend to mix less readily with Creole colleagues and neighbours. As

might be expected, the literate group also participates more generally in traditional activities and institutions.

NEW FORMS OF VOLUNTARY ASSOCIATION

Differences between the educated and literate group as a whole and the non- literate tribal population crystallize to form various kinds of association. Two types of social organization new to the Protectorate have been developed, the one under educated, the other under literate leadership. These are the ' social club' and the

'dancing compin ', and the nature of their aims and activities broadly expresses the kind of relationship that the educated and literate classes have with the rest of society. The ' social club ' is constituted for cultural, recreational, and educational purposes. Its members are nearly all educated or literate people, including a relatively large proportion of Creoles. This is not on account of any formal restrictions, because

membership is theoretically 'open to all'. However, club fees and subscriptions- generally Ios. entrance fee and a monthly subscription of 5s.-are usually beyond the means of people in more poorly paid jobs, and hence of most non-literate people.

I The wearing of native dress by members of the Bureau that some 30,000-35,000 persons are literate 'educated' class is definitely on the increase, for This figure includes my 'educated' category and reasons mentioned below (p. 225). a large number of people who are literate in only a

2 It is estimated by the Protectorate Literature native language.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE 221

Moreover, the kind of activity pursued there excludes, or is unlikely to appeal to, a

person who has not had a Western education. For example, all official business and

proceedings, as well as lectures, debates, &c., are conducted in English. In addition, although a weekly dance is usually one of the club's principal activities, persons wearing native dress are not admitted. The general rule is for the women to wear

print or silk frocks (without the head-tie), and the men open-necked shirts with a blazer or sports jacket. On special occasions evening dress is worn by both sexes.

The principal offices in the club are those of President, Vice-President, and General Secretary. There is also the Financial Secretary, the Social Secretary who organizes dances and other forms of entertainment, the Literary Secretary in charge of the club's small library and store of periodicals,.and the ' Tialler '.I The ' Tialler ' notifies members about meetings, &c. and collects dues and subscriptions on behalf of the Financial Secretary. These posts are filled by election, but the presidential office is

generally reserved for some popular individual relatively senior in government service. For example, two recent presidents of the Bo African Club-the oldest and

largest social club in the Protectorate-have been the Acting Principal of Bo School and the Acting Assistant Director of Medical Services. Both are Creoles and, as indicated above, Creoles generally take a leading part in the organization of the social club. This is partly because of their greater experience of such matters, but the

willingness of native members to accept them implies also an acceptance of the club's

Westernizing function. However, in addition to setting certain Western standards of social behaviour and

etiquette, the social club also serves to institutionalize one of the functions of educated and literate people. This is to provide an avenue of communication between Euro-

peans and Africans and between the various sections of African society. Thus, in addition to its ordinary activities, the club undertakes a number of public functions, including special dances to honour visiting notabilities. It also entertains the teams of visiting football clubs, and its premises are used for such purposes as political meet-

ings and adult education classes. Such occasions are open to the general public and the local European officials are often invited. Europeans are also invited to tennis tournaments, and matches between African and European teams are generally played under the club's auspices. For these reasons, and because it implies a relatively high economic status, membership of the club carries social prestige. Women are admitted as members, but there are very few married couples on the books of the only club at which I inquired about this.

Women have their own associations, however, which broadly complement those under the control of men. These are usually known as Ladies' Clubs and Women's Institutes, some of the latter being associated with church bodies. Quite a large num- ber of literate husbands have non-literate wives and these women's associations reflect the sociological situation in that some of them are divided into ' literate ' and ' illiter- ate' sections which hold separate meetings. ' Literate ' activities consist mainly in

sewing and crochet work, in practising the cooking of European and native dishes, and in listening to talks about household economy. Individual literate women give instruction in these arts to the 'illiterate ' meeting and in return non-literate women

I This word appears to derive from the masonic lodges which were established among Creoles in the Colony at quite an early date.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

222 STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE

teach the ' literate' group such things as garra-dyeing, basketry, spinning, and some of the traditional songs and dances. Sometimes money is collected for educational

purposes. For example, a Women's Institute, under the auspices of the E.U.B. Mission at Bo, hopes to provide one of its girls with a scholarship to a secondary school, its aim being ' to raise the standard of womanhood in Sierra Leone '.

We turn now to the other form of association mentioned above-the dancing compin. In this, fraternal as well as social aims' are stressed and, unlike the 'social club', it is also a species of Friendly Society and its activities are in part traditionalist. Also, although the dancing compin is largely under literate leadership, its members are

mainly non-literate or, at most, semi-literate. In addition to a few teachers and clerks it includes traders, artisans, lorry drivers, shop assistants, labourers, and other manual workers. Women are admitted on the same terms as men, which include an entrance fee of about 2S. 6d. and a weekly subscription of 3d. Compins have such titles as Alimania, Tarancis, Boys London, and Ambas Geda, and their principal activity is the

performance of' plays ' of traditional music and dancing which, however, are strongly affected by Western influence. The music is provided mainly by native drums, xylophones, and calabash rattles, and includes singing. A ' play ' is generally given in connexion with some important event, such as the close of Ramadan, or as part of the ceremonies celebrating a wedding or a funeral.2 The general public, as well as the

person honoured by the performance, are expected to donate money to the compin. These funds, as well as the amount collected in subscriptions, &c., are used for the benefit of members in the event of a relative's death or their own illness. The compin also looks after a member's interests if he becomes involved in a legal dispute. It has its own regulations prohibiting unruly behaviour and other misdemeanours, includ-

ing sexual ones, among members. An offender is fined and, if he persists in his trans-

gressions, may be expelled from the compin. All these matters are explicitly formulated in a written constitution and set of rules by which members must agree to be bound on joining the association. Office-bearers have such titles as President, Sultan, Judge, Provost, Doctor, and Nurse, and are very numerous in relation to total membership.3

Dancing compins are found mainly in Temne country, where the movement first took root from Freetown. There are also comrpins in most of the larger Mende towns, but it is interesting to note that they are invariably under non-Mende leadership, their founders usually being Temne or Mandinka.4

Though dancing compins offer relatively little attraction for the better-off educated native individual and the Creole, they have considerable significance in the new ' urban' environment of the Protectorate. They not only bring persons of different

I The following excerpt from the constitution of 2 See also Michael Banton, ' Ambas Geda ', West a particular compin is fairly typical in this regard: Africa, 24 Oct. I953, and 'The Dancing Compin',

'i. To maintain a co-operation and brotherly West Africa, 7 Nov. 1953. spirit among the people of this country. 3 A detailed description of the organization of the

2. To seek the progress and secure our prestige compin is contained in Michael Banton's unpublished among the people of this country. study, Urbanization in Sierra Leone.

3. To establish perfect unity and safeguard any 4 Banton (ibid.) suggests that the explanation of discord likely any time to arise among mem- this may be found in differences between the political bers. systems of the Temne and Mende. There is apparently

4. To give pecuniary help to any member and greater devolution of authority in the Temne system, strictly to seek the welfare of all in any matter allowing more freedom for the development of new arising either from economic, social or forms of association. domestic aspects.'

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE 223

tribes together in common association and to some extent bridge the gap between the literate and the traditional world, but they also provide mutual aid and protection in situations in which kinship can no longer perform these functions. In a somewhat similar sense the written constitution and regulations of the compin replace, as an agency of social control, the older sanctions which derived from patriarchal authority. The compin is also important politically. Its membership crosses the sectional barriers of a town and this means that its leaders can count on a good deal of popular support outside their own particular ' compound ', or kinship grouping. There are a number of instances where this kind of following is exploited by candidates seeking election as Paramount chief.

On the women's side an organization serving modern needs, though composed almost entirely of non-literate and semi-literate members, is the Bo United Moslem Women's Society. This, too, is a species of Friendly Society. A sixpenny subscription is collected every Sunday and persons joining as new members have to pay the equivalent of what a foundation member has already paid in subscriptions. This money is used, as in the dancing compin, to assist members who are sick or who have expenses in connexion with the burial of a relative. Some of the money is also dis- tributed as alms. The leader of the Society is the Mammy Queen, the present holder of this office being an elderly woman who speaks at least six Protectorate languages. There are a number of additional officials, part of whose duty it is to intervene in domestic quarrels and attempt to reconcile man and wife. The Society has disciplinary rules and expels any of its members who are constant trouble-makers in the home. It takes a prominent part as a group in Moslem festivals and it stages formal receptions for co-religionists returning from the pilgrimage to Mecca. On such occasions its members appear in oshorbi.'

EDUCATED AND LITERATE LEADERSHIP ROLES

The significance of the social club and the compin is also apparent in the fact that most of their leading members are the people mainly to the fore in other spheres of town life. Indeed, the tendency is for a relatively small group of educated and literate people to control most associational activity of a modern kind. Other organizations within this category range from church bodies, local branches of the Civil Service, educational, teachers', and ex-service men's unions, branches of the Sierra Leone People's Party to football clubs. Official bodies, such as the Native Administration, nowadays usually include a number of educated and literate individuals. The District Council is the local government body for about a dozen chiefdoms, and membership of it implies influence in public affairs. Thus X, who is a member of the Bo African Club, is also a leading lay member of his church, a member of the District Council, a prominent figure in the Sierra Leone People's Party, and a highly respected personality in at least two other organizations. Y has a prominent position in the social club, is also a leading light in the Sierra Leone People's Party, and has the principal position in at least one other organization.

I Oshorbi is a Yoruba custom introduced by the and accessories-for women, head-tie, necklace, and Aku Creoles. It is the practice of a group of people, sandals. usually friends, of wearing the same form of dress

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

224 STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE

Thus, although the influence of the traditional authorities is still paramount among the bulk of the non-literate tribal population, there are always certain educated and literate personalities whose advice is sought on any innovation proposed by the Government, not only by other literate individuals but also by tribal people, and even by Africans holding ministerial office in the Government. This consultation is the more likely-for reasons explained below-when the Paramount chief is himself an educated man. It goes, therefore, almost without saying that the presence of this elite is necessary to ensure the social success of any formal or informal gathering of the educated and literate classes, such as a reception or a ' send-off'.1

Informal leadership of this kind depends on a variety of factors. Educational qualifications coupled with the prestige of a senior position in the Civil Service are important. The post ensures a relatively high salary and thus enables a person to entertain friends and acquaintances in the lavish manner expected of a' big man '. It is almost equally important to be outspoken about Europeans, and at the same time to have the ability to deal successfully with them. Possession of the appropriate charac- teristics of personality is even more crucial. Above all, a leader should be a ' good mixer ',2 capable of moving freely among people of every tribe, including non-literate persons, and he should also be a fluent speaker in public. Kinship connexions are particularly important, of course, in all spheres involving traditional society, as in such organizations as the Native Administration, the District Council, and the dancing compin, but they are not indispensable. As already indicated, in matters not specifically connected with custom and tradition Creole leadership is quite acceptable (though more among the educated than the literate section), provided a person shows himself sympathetic to the native man's point of view. Indeed, one of the most respected figures in Protectorate society is the Creole individual mentioned above-the one- time Acting Principal of Bo School. The popular view is that he did much to raise its standards and thus materially assisted Protectorate people towards their political and other aspirations.

NEW HABITS AS A FACTOR IN SOCIAL DIFFERENTIATION

Up to a few years ago virtually the only form of illumination in the Protectorate was provided by kerosene lamps. In recent years, however, electricity has been in- stalled in a number of towns, and one of the results is that people feel able to move about more freely after dark. Whereas leisure time was previously spent chatting and drinking with friends on the veranda of one's house, some educated and literate people have now developed the habit of going out in the evening to meet their friends at a ' bar '. Bars are to be found in most of the larger towns. Often they con- sist simply of a shop entirely open to the street, with bottles of beer and wine stacked on shelves against the back wall. Sometimes, however, this ' shop' is in fact part of

' A 'send-off' is a convivial party, given by his a 'good mixer '-he never refused an invitation to friends and colleagues, to mark the departure of an anyone's house if he could possibly go. The implica- individual going on leave, on transfer to a new post, tion of these remarks is the stronger because, as or overseas. explained above, visiting the homes of non-kinsfolk

2 For example, in proposing the health of the guest and meeting and mixing with all and sundry is of honour at a 'send-off' which I attended, the entirely alien to native custom. M.C. laid special stress on the fact that Y was always

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE 225 a private house and a side door admits to a parlour which is used to accommodate customers personally known to the proprietor. This parlour might be compared with the saloon in English public houses, because it is used mainly by the better-off clientele. Here it is the living-room of the proprietor's house and drinks, served by young girls, cost no more than outside. Non-literate people, however, are generally excluded from the intimacy of the parlour unless personally known to the proprietor. It was explained to me that this was because of the danger of theft.

Another new leisure-time habit is that of cinema-going, although this is virtually confined to Bo, which has the only public cinema in the Protectorate. The charge for admission is 3s. and is. 6d. The cheaper seats are occupied almost entirely by non- literate people, the more expensive ones by Europeans, Lebanese, and educated or literate Africans. At the end of a performance ' God save the Queen' is played. It is

completely ignored by the is. 6d. section of the audience, who scramble noisily for the exits; but the 3s. section rise to their feet and stand conscientiously at attention to the last roll of the drums.

Two educated persons to whom I mentioned this disregard of the National Anthem both said that they deplored it. One of them commented that if' the people couldn't respect this [the Anthem] they would not respect their own symbol ', referring to the time when Sierra Leone would be self-governing. This comment is symptomatic of the educated class having developed a certain esprit de corps of its own, largely as a result of their being in the forefront of most political developments, including nationalism. Though the eventual right of self-determination for Sierra Leone has long since been accepted by the British, and Africans hold ministerial positions in the Government, there is still some opposition towards European officials. The educated

group are also aware of themselves as a very small minority with certain habits which are not only novel but viewed with considerable suspicion by the mass of their fellow Africans. Moreover, their consciousness of sharing ideas and attitudes which are different from those of non-literate tribal people is accompanied by the feeling that their superior knowledge entitles them to a greater share in tribal leadership. This does not mean that the educated group is opposed to tribal society. On the contrary, there is a growing interest, expressed most generally in the wearing of native dress, in traditional usages for their own sake. They also welcome traditional patronage, in the

persons of Paramount chiefs, for their social institutions, and usually seek their collaboration in national politics.' A further consideration is that the educated and literate class is still small enough for most persons of the same age-group to be personally known to each other.

The result of all these factors is a common bond of sympathy analogous to and patterned on traditional institutions of extended kinship which themselves reinforce it. This overrides conventional distinctions of tribe and tribal and official position and expresses itself in various practical ways. For example, an educated individual visiting another town as a stranger can always be sure of hospitality in the home of other educated people; and an educated chief will generally have a close circle of educated friends irrespective of whether they belong to the same chiefdom or tribe as his own. Within this coterie there is always tacit respect for the chief's traditional position. He is usually addressed as ' Chief' and is generally treated as a primus inter pares.

I A number of Paramount chiefs play a leading part in the Sierra Leone People's Party.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

226 STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE

How far does this feeling of group consciousness on the part of educated and literate people also imply consciousness of class differences ? From the evidence of cultural differentiation already cited, it might be argued that there is emerging a

system of social stratification analogous to social classes as found in Western Europe. There are in addition certain conditions and practices which make for social distance. For example, when important football matches are played the majority of the

spectators stand in a throng at the edge of the ground, but a number of seats and benches on the touch-line are left vacant. These are reserved for the patrons of the match, club officials, &c. and their friends, which means, in effect, that most of the educated and literate people present have seating accommodation, while non-literate

people do not. Another more obvious factor is the motor-car. Whereas the great mass of the

population travel about the country in lorries, on bicycles, or on foot, a number of individuals have cars either in connexion with their official duties or because they are

wealthy enough to afford them. Sometimes these cars are chauffeur-driven, either in emulation of highly placed European officials or because their owners cannot drive. The result is an increasing tendency for educated people not to move any distance on foot, and even bicycles seem to be eschewed. I have noted a number of instances when a person with pressing business in another part of the town has preferred to await the

long overdue arrival of some colleague or friend with a car rather than walk there. The reason given is that' it is too hot' or there will be' a shower of rain '. Again, it is not uncommon for Bo schoolboys, returning from holiday, to pay some other small

boy a few pence to carry their loads from the railway station to the school compound -a distance of not much more than zoo yards.

It is evident from these examples that certain forms of' Western' behaviour are

regarded by educated and literate people, if not by Africans in general, as symbolic of high social status. The practice of riding about in a car is associated with a relatively exalted position in the Civil Service, as personified specifically by Europeans. The latter apparently never do any manual work except perhaps gardening, and for a

European to carry his own loads is virtually unheard of.

EDUCATION' AS A SYMBOL OF STATUS

Mainly significant in this respect, therefore, are the institutions which hinge on the Western social system as instituted by British colonialism. This system is based on the

ranking of individuals in hierarchical order according to their positions and occupa- tions in the Civil Service. Thus members of the administrative branch are at the top of the social hierarchy, followed in approximate order by those in the legal and medical branches, education, police, agriculture, forestry, customs, post and tele-

graph, public works, and railway. In African eyes the Civil Service virtually consti- tutes the ' Government' and, until recent years, its senior members were regarded as, and to a large extent were in fact, the real rulers of the country. The inclusion of

larger and larger numbers of Africans in the Legislative Council and the appoint- ment of Africans with ministerial portfolios has somewhat altered the situation and has created new forms of social status. However, these changes have not detracted from the values attaching to 'education'. Most Africans know that the primary

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE 227

qualification for anything but the most subordinate posts in government service is a Western education, and they also know that a senior position requires educational or technical qualifications of a superior kind. It is similarly appreciated that political advancement depends largely on Western forms of knowledge and that, lacking these, no commoner has much hope of finding his way into the Legislative Council, let alone achieving ministerial rank. For reasons of this kind, therefore, education and literacy carry considerable prestige.

However, it is necessary to distinguish between the attitude of educated and literate people and that of the rest of Protectorate society. The former group earn their living for the most part outside tribal culture. Their success depends on having certain requisite skills as teachers, clerks, nurses, &c. Their further prospects, at any rate in an economic sense, are bound up in these occupations and depend on satisfying employers who are either Europeans or other Westernized Africans. Traditional considerations-the membership of a particular kinship group or tribal association- can sometimes be quite important both in securing a job and improving it, but they are transcended by the value placed on such things as technical knowledge, routine habits, and efficiency. In other words, so far as employment in a school, a business firm, or a government department is concerned, the question is primarily whether a person is qualified for the job and not whether he is a Temne or a Mende or a member of a particular family or of the Poro society.

It is possibly for these reasons that' education ' is so greatly prized by most native persons who have been to school, since upon its possession apparently depends not only their present well-being but the fulfilment of their future ambitions. I asked a number of people by questionnaire how a person whom they particularly admire could best be described. After ' good mannered ', 'well-educated' was the criterion most frequently preferred.I Most of my informants explained that by ' well-educated ' they meant the attainment of a standard (of education) which ' will help the community '; others referred to formal qualifications and to the possession of a wide and practical knowledge. This suggests that, apart from its economic implications, 'education'

I My questionnaire took the form of nine type- The following is a summary of the Protectorate written statements, e.g. ' He (or she) dresses well', and Edinburgh results: ' is well-educated ', 'is good-looking ', ' is kind to his (or her) relatives ', ' has a worthwhile job ', ' is wealthy', 'has good manners ', 'goes regularly to church (or to the mosque) ', 'is a good husband'. Informants were asked to choose four of these or to substitute alternative statements of their own. They were also asked to explain their understanding of each of the four statements they chose. I received replies from 83 persons of whom 68 were students at a teachers' training college and at Bo School; the remainder being teachers and clerks. Most of the Protectorate peoples were represented, but Mende comprised rather more than half the sample. I also conducted the same experiment with 15 Creole teachers resident in the Sierra Leone Colony and with 150 British students reading Psychology at Edinburgh University. Thirteen out of the fifteen Creole teachers included 'well-educated' in their selections.

Protectorate Edinburgh group students

No. in sample . . 83 50 Dresses well . . 9 (23) 33 (22) Well-educated . . 66 (80) 97 (65) Good-looking . . 23 (28) I9 (13) Kind to relatives . I (6I) 60 (40) Worthwhile job . 24 (29) 76 (5I) Wealthy .. . (13) 2 (-) Good manners . 78 (94) Ioi (67) Regularly to church . 50 (6i) 40 (27) Good husband . 4(17) 58 (40) Other statements . 4 (5) 95 (65)

N.B. Figures in brackets denote the choice of the particular statement as a percentage of the total sample.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

228 STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE

is regarded as something intrinsically valuable. This was even more evident in replies given to me by a small sample of Creole teachers.I However, there is always the

difficulty of estimating how far answers given formally in response to a questionnaire convey the true nature of informants' attitudes. From further inquiries made more

indirectly among literate people, it also appears that' educated ' is virtually a synonym for ' civilized '. The latter term, in turn, carries the very strong implication of' right- ness' of behaviour in the exact sense in which Sumner interprets the expression m/ores.

The non-literate individual also admires ' education ', and for him, too, the expres- sions 'educated' and 'civilized' are virtually coterminous. But he thinks of an educated person primarily as a ' book man ', 'one who knows book', in other words, simply someone who can read. In a more general and quite neutral sense, a' civilized '

person is someone who practises European ways or someone who has given up farm-

ing and earns his living in some other way than on the land. It has, in addition, the favourable implications of' knowledgeable', ' well travelled ', ' neat in appearance ', and ' generous with money '.2 In these respects, therefore, the non-literate individual is alive to and is fully prepared to acknowledge that ' education ' has certain advan-

tages-it can be a means to a higher income and a less arduous life-but he is quite unmoved by the spiritual and other non-material benefits it is supposed to confer. In addition to respecting the educated man's acquisition of Western ' know-how', he envies his ability to deal with Europeans without an interpreter, and is envious of his

larger supply of enamel ware. But it is doubtful if he feels that the educated African is his superior in any intrinsic sense of the term, and he is inclined to scoff at and regard as completely faddy the emulation of some Western customs-such as boiling drinking-water and protecting food from flies. Any feelings of awe and admiration he reserves for Europeans as the real owners of Western civilization and its wonders, whom in former times he often looked upon as genii on account of their white com- plexions. The educated African is just another African.

These considerations emphasize the difficulty of construing Protectorate society in terms of a single integrated system, and hence of postulating social classes in the Western meaning of the term. This difficulty is the greater because of the different

things that are socially evaluated by the people themselves. In addition to' education ' and its occupational concomitants, educated and literate people estimate social prestige in terms of religion and money income. Among non-literate people, on the other hand, it is age and kinship connexions which largely determine social status. A large kinship circle and the ownership of land are more important than money, and a Moslem has more social standing than a Christian.

THE INFLUENCE OF TRADITIONALISM

The greatest objection, however, to treating the educated and literate group as a separate social class is structural. It lies in the fact that the more intimate part of an educated or literate person's life is still spent in constant association with non-literate

I See footnote i, p. 227. My Creole informants university degrees'. explained that 'well-educated' meant 'intellec- 2 Cf. K. L. Little, The Alende of Sierra Leone, tually, mentally, and morally trained as well as pp. 262-3. possessing significant formal qualifications, such as

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE 229

people. Literate girls are even fewer than literate men, and very few women have been to a secondary school. The result is that every native individual has a large number of relatives, including some closest to him in kin, who are completely non- literate. Moreover, it was in this kind of circle, in most cases, that he was reared and the most impressionable years of his life spent. Thus his personal relationships are still governed by traditional ideas of status and etiquette, and respect for age and one's obligations as a host are taken as much for granted by a literate as by a tribal individual.

An educated young Temne informant explained to me that his own position in this

regard was no different from that of a non-literate person. He wrote: When a stranger' arrives (not necessarily a relative; it may be a close friend), the least a

person can do is to slaughter a fowl for him. The fowl is handed to the stranger who is told that it is his sauce. If the stranger intends to stay long enough for the culinary process he asks for the fowl to be killed; otherwise he retains it and carries it home. Thus, it is necessary to keep fowls for the visits of fathers-in-law and others. After the cooking special parts of the fowl are put out for the stranger and he is often given a special dish. In the case of strangers who are literate visiting illiterates, china-ware and a spoon are provided. Often the host's own friends in the village also send bowls of rice to the stranger. This is to signify to the stranger that his host is well thought of. In the evening the stranger may be offered drink by other friends of the host. This generous reception lasts as long as the visitor stays, which is usually not longer than a month unless he comes from some distant place. Casual visitors are invited to the bowl from which the other men present are eating, and are expected to take at least one handful as a sign of goodwill.

The etiquette, therefore, is fairly rigid and deeply rooted, particularly so far as

commensality is concerned. In a large-sized household the rule is that one set of bowls of rice and sauce is provided first for the older men; there is another set for the

younger men; and further sets for the children according to age, the youngest eating with the women. The women eat separately, of course, though occasionally a woman

may invite a male relative or guest in the house to share her dish. In all the groups each person eats by taking a lump of rice with his fingers from the common bowl and

dipping it in the sauce. Deference to older people is also paid by addressing them as ' father ' and ' mother ', and by bending the knee when passing or approaching them. This is done in the case of older women as well as men, and it is good manners for a wife to salute her husband in this way.

Generally speaking, educated people continue to observe this etiquette so long as the company is confined to other native Africans, educated or not, though some of them prefer to use a spoon when dining alone or with other educated people. If the

group contains both older and younger people, a young man automatically joins his own age-mates; and in his own house an educated man dines by himself or with his male guests, his wife taking her meal after he has finished. It is unusual for even an educated woman to sit among a group of men for conversation; and if there should be a shortage of seats a younger man will give up his place immediately on the arrival of an older man.

However, if a European, or a Creole colleague, calls at the educated native person's The term' stranger ' has the general meaning of ' guest '. It can also refer to a person living in another

man's house in a position of dependence.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

230 STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE

home the situation is changed. Any non-literate persons present will retire into the

background or even from the room, and if the host invites his European or Creole caller to a meal, only the educated people present will sit down together, the non- literate guests taking their food apart. Probably a full set of eating utensils, including knives and forks as well as spoons, will be used. Again, if the educated man's wife is also familiar with Western etiquette, both she and her husband will sit down at a European's or a Creole's table.

Food-eating etiquette essentially symbolizes family feelings, and the continued adherence of literate people to it is an indication of the persistence of kinship as an

integrative force in Protectorate society. In other words, in present circumstances there is no question of the ordinary literate person being divorced or wishing to divorce himself from his kinsfolk. On the contrary, the more ambitious he is the more likely it is that he will rely on them for support in a variety of ways. One or two

typical cases will suffice to exemplify this.

X completed his school education with the Cambridge Junior Certificate. He obtained a job as a clerk in the Civil Service and, after working for a number of years in the office of the District Commissioner, he was fired with the ambition to become a lawyer. He undertook the preliminary study but needed to go to Britain in order to complete the qualifications. By this time he was about 30 years of age, had saved a little money of his own but not nearly enough for the cost of residence abroad. He applied for a Government scholarship, but was unsuccessful. His remaining principal recourse was to his relatives. They agreed to help him. He had shown himself a good kinsman and his conduct in that respect had encouraged them to believe that he would remember his obligations to them on his return.

Y also went to a secondary school. He began his career as a teacher in a Mission school, but has political ambitions. As he is a member of a ' crowning house " there is a possibility of his being elected Paramount chief of his native chiefdom. He proposes therefore to stand as candidate at the first opportunity, but his hope of success depends mainly on the attitude of the 'big men' of the chiefdom who, as the Tribal Authority, are responsible for the election. He must win their favour as soon as possible because there will be other candidates in the field. This means a good deal of expenditure in terms of presents and hospitality which may amount to several years' ' nursing' of his constituency. Not only is family support necessary in this way, but he requires his relatives to canvass for him in the different sections of the chiefdom. Indeed, given the widely ramified nature of kinship ties and affiliations, particularly in the case of a well-established descent group such as a ' crowning house ', this factor is probably more important than the economic one.

The result is that for these or related reasons most educated individuals are in- clined to accommodate themselves so far as possible to non-literate opinion. This means assisting relatives in various small financial ways and attending family cere- monies, especially funerals. Depending on his age and status in the group, an educated relative's advice is sought especially in contacts with Europeans; and family quarrels and disputes are brought to him for settlement. Another appreciable factor is that to an increasing extent the furtherance of a literate man's career is dependent on tribal

goodwill and co-operation in quite a general way. This is most apparent, perhaps, in the political field, where the trend is almost entirely towards ' democratization' on

I A 'crowning house' is a descent group which has at any time supplied a Paramount chief for the chiefdom concerned.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE 23

Western lines. Chiefs, nowadays, are 'elected', and, although this is not done by popular vote, it does mean, as indicated above, that a good deal of solicitation among non-literate people has to be done. Also, membership of a District Council, which is composed of two representatives from each chiefdom, is largely dependent, in the case of commoners, on the attitude of the tribal' big men '. Furthermore, the expan- sion of social services by the Missions as well as by Government means that a host of literate persons now have the task of persuading and encouraging tribal people to attend clinics and schools, to take part in literacy campaigns, to start co-operatives, credit societies, &c. The readiest means of winning non-literate sympathy for these matters is by conforming as closely as possible to customary etiquette, hence there is a further motive for a literate person to identify himself with tribal culture.

DUALISM IN SOCIAL RELATIONS

The result of all this is that the educated African is called upon to move in two social worlds, involving in many respects quite different norms of conduct and behaviour. The kind of behaviour expected of him varies with the nature of the situation, and the situation itself is mainly defined by the extent to which Western agencies-in the persons of Europeans or highly Westernized Africans, or institutions such as an office or a school-are involved. This means that at work or at church, for example, he behaves as a European would in similar circumstances. In his own home and family circle his actions are largely, though by no means wholly, traditional. This is another way of saying, though at the cost of considerable simplification, that in his private life he is an ' African ', in public a ' European '.

This may suggest that the educated person is to be typified as a cultural hybrid, often the prey, according to some writers, of divergent sets of actions and feelings. Studies by Stonequist, for example, indicate that such a person suffers frequently from inner conflict and disharmony resulting from a clash of personal loyalties.' However, among this educated group in the Sierra Leone Protectorate, symptoms of stress are apparently as rare, so far as can be judged, as among Africans living tribally, and there is no emotional problem.

The reason, perhaps, is that the dualism in this case is more apparent than real. As a result of his Western indoctrination the educated African, it is true, is ambitious for personal success in the new careers and occupations opened up to him by contact with the outside world. These new careers-in the Civil Service, in politics, and in the pro- fessions-are attractive because they enable him to improve his social standing at a much earlier age than is possible under the tribal system. They also afford the prospect of a much wider prestige in the new form of national society which is gradually supplanting tribal systems of government.

But these fresh opportunities have to be pursued in what, from the point of view of most Protectorate people, is still an alien culture. As mentioned above, Western influence has only been significant in this part of West Africa for some fifty years. It is a culture, moreover, which is still dominated by Europeans, whose sympathy for African aspirations depends, or appears to depend, on the extent to which a person conforms to Western notions of proper conduct. Most heads of government depart- ments and the managerial class in general are European and many of their senior staff

I Cf. E. V. Stonequist, The Marginal Man, New York, 1937.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

232 STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE

are Creoles, and this, no doubt, partly explains the native man's performance in public as a ' European '. He evidently believes that to gain European or Creole support he must appear, outwardly at least, as Western as possible. It is as if he felt that whatever technical qualifications he possesses have to be supplemented by certain social skills which are part of the art of being ' civilized '. The fact that these social skills-the

ability to converse fluently in English, to serve European dishes, &c.-lead also to the making, or apparent making, of social distinctions between him and his fellow Africans is incidental.

For the educated African realizes, at the same time, that his own strongest and most intimate ties are with traditional society as a whole. He also feels that there is, as yet, no real place for him in the culture outside and nothing really adequate to replace the sense of security and well-being provided by membership of his own kinship circle. He looks upon his relationship with them as an end in itself, whereas his relationship with a European, or even with a Creole, is a means to an end and involves a smaller sense of obligation. Consequently, there is no real psychological dilemma because there is no real division of personal loyalties and feelings. There is a division; but it is a division in the sphere of action rather than sentiment and implies the suiting of action to social situation.

CONCLUSIONS

The crux of contemporary Protectorate society is that its African members are motivated by different ideas of what constitutes social value and prestige. This makes it impossible for us to conceptualize their social behaviour in terms of a single system. It has to be analysed in terms of social situations. Situations vary according to the normative expectations of the actors and in this case considerations of a cultural kind are the principal instrumental factor. In other words, an individual's actions are in- fluenced by the cultural status, in terms of relative degrees of Westernization, of those with whom he interacts as well as by his own cultural status. This implies a

multiple organization of social relationships. However, from the present evidence, it does appear that the social situations involving educated and literate participation can be roughly classified within two distinctive, but overlapping, systems, dominated

respectively by Western and by traditional schemes of value. The existence of the Western system depends on the fact that native Africans are

filling a number of occupational and technical roles unknown to the tribal culture. These individuals constitute new social groups, which, characterized by the common

possession of Western education and literacy, represent a change in the structure of Protectorate society. Whereas its traditional organization is based mainly on factors of kinship and age, the members of these new groups have a community of interest and outlook rooted largely in the Western economic system in which their livelihood is vested. There is among them some consciousness of kind and a confidence that one can meet other members on equal terms and that one's mode of behaviour will be in

harmony with the behaviour prevalent in the group. There is also mobility in that it is

possible for a non-literate individual to move into the literate group. At the minimum he only needs to be fluent in English and to display knowledge of certain European ways and customs.

The question therefore arises as to how far this reorganization of Protectorate

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE 233

society implies a system of social class. Goldschmidt has suggested that ' a true class- organized society is one in which the hierarchy of prestige and status is divisible into groups each with its own social, economic, attitudinal and cultural characteristics and each having differential degrees of power in community decisions. Such groups would be socially separate and their members would readily identify.'"

In terms of the Western aspect of the matter, contemporary Protectorate society clearly approaches this definition. Not only are there groups, each with its own social, economic, attitudinal and cultural characteristics, but in certain situations educated and literate persons enjoy special powers and prestige, identify with each other and are identified by non-literate persons as a separate class.

However, class differentiation is usually associated with feelings of inferiority and superiority towards those above and below one in the social hierarchy. In the present case such feelings have not so far developed, or are largely suppressed because traditional factors, principally kinship, continue to play a very important part in the general ordering of community life. In other words, social classes, in the general meaning of the term, exist in the Sierra Leone Protectorate only in an embryonic form.

I Walter Goldschmidt,'Social Class in America-A Critical Review', American A.nthropologist, vol. lii, no. 4, I950, pp. 483-98.

Resume LES MODIFICATIONS STRUCTURFJLLRS DANS LE

PROTECTORAT DE SIERRA-LEONE

LES changements principaux qui sont survenus dans la structure de la societe de l'Afrique Occidentale sont les resultats des influences occidentales et occidentalisantes. Un aspect particulier de ces modifications structurelles dans le Protectorat de Sierra-Leone se traduit par une nouvelle classe sociale composee de personnes ayant recu une certaine instruction et sachant lire et ecrire et par leurs rapports avec la societe traditionnelle. Cette nouvelle classe se distingue par son niveau plus eleve de logement, d'habillement et de biens materiels, en comparaison avec celui de la population tribale. La plupart de ses membres sont des chre- tiens et ils se livrent a des occupations diverses. Ils sont instituteurs, employes de bureaux, infirmieres, secretaires des conseils regionaux, ouvriers specialises et techniciens.

Les differences entre ce nouveau groupe social et la population tribale analphabete se cristallise sous forme d'associations volontaires de toutes sortes, dont le ' social club ' et le 'dancing compin' sont des exemples typiques. La plupart des membres de la premiere de ces organisations ont frequente, au moins, une ecole primaire et ses activites comprennent des conferences, des debats, des bals ou l'on danse dans le style occidental et des distractions occidentales de toutes sortes, y compris le tennis. Le ' dancing compin' vise egalement des buts sociaux, mais il est, en meme temps, un genre de societe de secours mutuels et ses activites sont plut6t traditionalistes et comprennent l'execution de la musique et des danses, tant indigenes qu'occidentalisees. Il comble, dans une certaine mesure, la lacune entre les gens ayant regu de l'instruction et la societe traditionnelle; il fournit de l'aide et de la protec- tion mutuelles, et constitue une agence d'autorite sociale dans des situations ou la parente a cesse d'etre efficace. Le ' dancing compin ' constitue egalement la base de formes nouvelles d'organisation politique. Les deux genres d'association sont essentiellement des manifesta- tions de la vie des villes ou les nouveaux groupes de personnes instruites et lettrees se sont principalement concentres.

R

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

234 STRUCTURAL CHANGE IN THE SIERRA LEONE PROTECTORATE

La diffusion des nouvelles faSons d'employer les moments de loisir, telles que la frequenta- tion des cinemas, augmente egalement les diffdrences culturelles et autres entre la section occidentalisee et la partie tribale de la population, de sorte que les gens instruits et lettres ont tendance a se considerer comme un groupe distinct ayant une mission civilisatrice parti- culiere. Cependant, ces sentiments et ces attitudes n'ont pas encore fait naitre une conscience de classe dans le sens que ce terme est compris dans l'Europe occidentale. Malgre la place tres importante tenue par l'instruction comme facteur de diff6renciation sociale, une per- sonne instruite frequente une societe qui n'est reglee que partiellement par les valeurs occidentales. A son travail ou a l'ecole, par exemple, une telle personne se comporte comme un Europeen se comporterait dans des circonstances analogues, mais, dans son foyer et dans ses rapports personnels avec les membres de sa famille, dans le sens le plus etendu du terme, ses actions sont, pour la plupart, generalement traditionnelles. Un grand nombre de ses parents les plus proches sont analphabetes et ses rapports avec eux et avec le cercle plus etendu de la parente sont regles par les coutumes de la tribu. Ses connaissances et son habilete occidentales sont respectees, mais il a besoin de l'appui financier de ses parents pour aider son avancement dans sa carriere professionnelle et il est largement tributaire de leur soutien politique s'il vise un rang eleve dans les affaires indigenes.

CONTRIBUTORS TO THIS NUMBER

KENNETH L. LITTLE, M.A., Ph.D. Head of the Department of Social Anthropology, University of Edin- burgh; author of The Mende of Sierra Leone and other studies.

P. C. LLOYD, M.A., B.Sc. Research Fellow (Anthropology), West African Institute of Social and Economic Research, University of Ibadan, Southern Nigeria.

JOHN MIDDLETON, D.Phil. Temporary Senior Lecturer in Social Anthropology, University of Cape Town. W. G. ATKINS, M.A., D.Phil. Lecturer in Bantu Languages at the School of Oriental and African Studies,

University of London. R. E. S. TANNER. District Officer, Tanganyika Territory.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.78 on Sun, 15 Jun 2014 18:02:11 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions