Strengthening HealthResearch intheDevelopingWorld ...Africa to tackle the major and increasing...

Transcript of Strengthening HealthResearch intheDevelopingWorld ...Africa to tackle the major and increasing...

Strengthening Health Researchin the DevelopingWorld

MalariaResearchCapacity inAfrica

Pauline Beattie

Melanie Renshaw

Catherine S Davies*

Prepared by the Wellcome Trust

for the Multilateral Initiative on Malaria

*Corresponding author

PREFACE 6

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 7

GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS 8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 9

Introduction 9Main elements of the study 9Main findings 9Recommendations for the way forward 13

1 INTRODUCTION 17

1.1 Approaches to the study 171.2 Background 171.3 Health research in developing countries 181.4 Public health significance of malaria 191.5 The Multilateral Initiative on Malaria 20

2 TRAINING OPPORTUNITIES 23

2.1 Methods 232.1.1 Survey of funding agencies 232.1.2 Data analysis 232.2 Results 242.2.1 USA and Canada 242.2.2 Europe 292.2.3 Asia and Australia 402.2.4 International organizations 402.2.5 Developing countries 422.3 Overview of awards and discussion 442.3.1 Investors in training 452.3.2 Expenditure 462.3.3 Training level of awards 482.3.4 Geographical distribution of awards 492.3.5 Training mechanisms 502.4 Conclusions 51

3 OUTPUTS OF MALARIA RESEARCH 53

3.1 Background 533.2 Methods 543.2.1 Overview of bibliometric analyses 543.2.2 Databases and search strategy 543.2.3 National outputs and collaboration patterns 543.2.4 Research categories 553.2.5 Funding acknowledgements 553.2.6 Impact of research 553.2.7 Malaria guidelines and policies 55

CONTENTS

3 OUTPUTS OF MALARIA RESEARCH (cont.)

3.3 Results 553.3.1 Global and African malaria research outputs 553.3.2 International collaboration in malaria research 593.3.3 Research categories 623.3.4 Funding acknowledgements 633.3.5 Characterization of top research institutes in Africa 653.3.6 Impact of research 683.3.7 Malaria guidelines and policies 693.4 Summary and discussion 69

4 MALARIA RESEARCH CAPACITY IN AFRICA 73

4.1 Methods 734.2 Results 744.2.1 Overview of research groups 744.2.2 Profile of malaria researchers 804.2.3 Training needs and solutions: an African perspective 824.3 Summary and discussion 85

5 OVERVIEW AND POLICY ISSUES 89

5.1 Introduction 895.2 Policy issues 895.3 Reflections on methodologies 94

REFERENCES 96

ANNEXES 97

1 Contributions to the UNDP/World Bank/WHO 99Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR) 1989–98

2 Contact details of funding organizations 1003 Search strategy to identify malaria papers using the SCI 102

and MEDLINE databases4 African publication output in SCI and MEDLINE 103

databases (1995–97)5 Malaria control guidelines and policies 1036 Malaria research classification system 1047 Acknowledgements by funding body for papers 106

(international and African) from 1995–978 Questionnaire for the survey of African malaria 108

research laboratories 9 Survey respondents 11110 Funding sources listed by respondents to a survey of 112

African malaria research laboratories11 Funding acknowledgements for Master’s and PhD training 113

in a survey of African malaria research laboratories12 African malaria research groups contact details 114

CONTENTS

6 Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica

Despite nearly a century of research, malaria has yet to be conquered in its bastion, Africa south of theSahara, where the majority of the world’s cases are to be found. Nevertheless, the tremendous effort tounderstand the disease and develop effective methods of control has removed the disease from signifi-cant parts of the world.

A major component of the research effort against malaria is the capacity of scientists based in Africato study the disease on the ground. This report identifies existing centres of excellence as well as high-lighting areas of remaining need. As is typical of reports of this kind, in which new data are brought tothe fore, interesting phenomena are uncovered which, when revealed, suggest obvious solutions.Perhaps the best example of this is that the majority of collaborations that individual scientists in Africahave are with laboratories outside the continent, mainly Europe and the USA. Surprisingly, there isminimal collaboration within Africa. Therefore, funds need to be made available to foster collabora-tions on the continent and maximize the impact of existing knowledge and experiences.

Although the objective of this report was to provide evidence to guide the development of theMultilateral Initiative on Malaria, its findings can probably be generalized to many areas of healthresearch. Clearly, further coordination of the multitude of agencies supporting health research is calledfor, but perhaps more importantly there needs to be a closer link between these agencies and scientiststo identify local needs as well as with governments to ensure the long-term sustainability of theresearch infrastructure. It is very much hoped that this report will stimulate such activities in an analo-gous manner to an earlier report on malaria research from the same stable.

Richard LaneHead of the Wellcome Trust’s International Programmes

October 1999

Preface

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 7

The authors would like to extend their sincere thanks to colleagues at the Wellcome Trust for theirsupport, advice and direction during the preparation of this report: Elizabeth Allen, Graham Dawson,Grant Lewison and David Seemungal of the Wellcome Trust’s Policy Unit provided invaluable adviceand assistance in carrying out bibliometric analyses and survey work.

Individuals who provided constructive input on the draft report are also gratefully acknowledged:Peter Billingsley (University of Aberdeen, UK), Joel Breman and Gerald Keusch (Fogarty InternationalCenter, NIH, USA), John Claxton (Wellcome Trust), Brian Greenwood (London School of Hygieneand Tropical Medicine, UK), Kevin Marsh (Wellcome–KEMRI, Kenya), Ayoade Oduola (Universityof Ibadan, Nigeria), Odile Puijalon (Institut Pasteur, Paris), Robert Snow (Wellcome–KEMRI,Kenya) and Fabio Zicker (TDR, Geneva).

The authors are particularly indebted to those responsible for the African Malaria Vaccine TestingNetwork (AMVTN), especially Wenceslaus Kilama, for allowing inclusion of information from theAMVTN Directory in analyses presented in this report. Similarly, the Fogarty International Center ofthe US National Institutes of Health is gratefully acknowledged for permitting use of informationcontained in the Inventory prepared for the meeting held in Dakar, Senegal, in January 1997.

Finally, the authors would like to express special thanks to representatives of funding agencies whotook time to provide data on training activities, and to all those individuals from African research lab-oratories who participated in the MIM survey and provided so much important information.

This study was funded in full by the Wellcome Trust (registered charity, no. 210183).

The Trust’s sole Trustee is The Wellcome Trust Limited, a company registered in England, no. 2711000,whose registered office is 183 Euston Road, London NW1 2BE.

Acknowledgements

8 Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica

AusAID Australian Agency for International Development

BADC Belgian Administration for Development Cooperation(Administration Générale de la Coopération auDéveloppement)

BMZ Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development

BWF Burroughs Wellcome Fund,USA

CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USA)

CIDA Canadian International Development Agency

CNPq Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Cientifíco eTecnológico,Brazil (National Council for theDevelopment of Science and Technology)

COHRED Council on Health Research for Development

DAAD Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (GermanAcademic Exchange Service)

DANIDA Danish International Development Assistance

DBL Danish Bilharziasis Laboratory

DEA Diplome d’Études Approfondies

DFG Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft

DFID UK Department for International Development(formerly ODA)

DOD US Department of Defense

DG XII Directorate General XII, European Commission

EIS Epidemic Intelligence Service

ENRECA Enhancement of Research Capacity in DevelopingCountries,DANIDA

FCS Federal Commission for Scholarships for foreignstudents, Switzerland

FIC Fogarty International Center,US National Institutes ofHealth

FINEP Financiadora de Estudos e Projectos (Brazilian Agencyfor the Funding of Studies and Projects)

GTZ Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit(German Agency for Technical Cooperation)

HRP UNDP/UNFPA/WHO Special Programme forResearch,Development and Research Training inHuman Reproduction

IAEA International Atomic Energy Agency

IDRC International Development Research Centre,Canada

IHTM Institute of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine,Portugal

INCLEN International Clinical Epidemiology Network

INCO-DC International Cooperation with Developing Countriesprogramme,European Commission

INPA Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas da Amazonia (NationalAmazon Research Institute),Brazil

INSERM Institut National de la Santé Recherche Médicale(French Institute of Health and Medical Research)

IRD Institut de Recherche pour le Développment (formerlyORSTOM),France

IRTC WHO Immunology Research and Training Centre,Lausanne, Switzerland

JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency

KEMRI Kenyan Medical Research Institute

MCT Ministerio da Ciencia e Tecnologia (Ministry of Scienceand Technology),Brazil

MIM Multilateral Initiative on Malaria

MRC Medical Research Council (UK or South Africa)

NGO Non-governmental organization

NIAID National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (USA)

NIH National Institutes of Health,USA

NORAD Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation

NRF National Research Foundation, South Africa

OCEAC L’Organisation de Coordination pour la Lutte contre lesEndémies en Afrique

PAHO Pan American Health Organization Regional Office ofthe World Health Organisation

RCS Research Capability Strengthening

RTG Research Training Grants

SAREC Swedish Agency for Research Cooperation withDeveloping Countries

SCI Science Citation Index

SDC Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation

SEAMEO– South East Asian Ministers of Education Organization TROPMED Regional Tropical Medicine and Public Health Network

Sida Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency

SNSF Swiss National Science Foundation

STI Swiss Tropical Insitute,Basle

TCP Technical Cooperation Projects

TDR UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme forResearch and Training in Tropical Diseases

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNFPA United Nations Population Fund

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

USAID US Agency for International Development

WHO World Health Organization

WRAIR Walter Reed Army Institute of Research,US Department of Defense

Glossary of abbreviations and acronyms

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 9

INTRODUCTION

Experiences during the last century have shownthat the returns from well-targeted healthresearch can be immense. Vaccines and diseasetreatments, for example, together with newknowledge to enable people to maintain theirown health, have averted disease, reduced suffer-ing and enabled greater productivity in manyregions. However, the research bases in mostdeveloping countries require significant strength-ening to enable effective responses to the chal-lenges of local health problems.

The Multilateral Initiative on Malaria(MIM) is a global initiative that is particularlyconcerned with building research capacity inAfrica to tackle the major and increasing prob-lem posed by malaria. This study was undertak-en by the Wellcome Trust as part of the activitiesof MIM. The purpose was to generate soundanalytical data that could inform discussions onstrategies for strengthening research bases inAfrica and enable future monitoring of progress.

The study included a unique survey of train-ing opportunities in health and biomedicalresearch offered by high-income countries to sci-entists in developing regions. It also examinedthe current status of malaria research capacityand training in Africa using a number ofapproaches. Research outputs, infrastructure,availability of trained personnel, training path-ways and funding sources were assessed, and theopinions of African scientists on training needsand solutions were sought.

The findings of the review represent aresource for funding organizations and govern-ments in both developed and developing countries to assist evidence-based approaches toresearch training activities. In addition, the reportis intended to raise awareness amongst Africanscientists of current research training opportuni-ties and the characteristics of leading malariaresearch centres across sub-Saharan Africa.Although the review has a particular focus onmalaria research in Africa, many of the conclu-sions are more broadly applicable to capacitydevelopment in other research areas and otherdeveloping regions.

MAIN ELEMENTS OF THE STUDY

The study comprised the following analyticalapproaches:1. A survey of training opportunities for devel-

oping-country scientists in biomedical sci-ences and health offered by funding organi-zations internationally (1995–98).

2. An assessment of research capacity and trainingactivities in African malaria research through:• analysis of malaria publication outputs in

MEDLINE and Science Citation Index(SCI) databases (1995–97) to identify themost productive countries and centres, col-laboration patterns, funding sources, sub-field specializations and citation impact;

• analysis of research literature cited inAfrican national malaria treatment guide-lines and policies;

• a questionnaire-based survey of 54 malariaresearch centres across Africa to assess facili-ties, expertise and training pathways, and togather opinions on research training needsand solutions.

MAIN FINDINGS

Broad indicators of malaria research capabilityAnalysis of malaria publications in the SCI data-base for 1995–97 showed that African scientistsand institutes make a major contribution tointernational malaria research: 17.2 per cent ofglobal publications included an address inAfrica. By comparison, the contribution ofAfrica to overall research in health and biomedi-cine, stands at just 1.2 per cent of the world’soutput. The highest contributing individualcountries in malaria research were the USA, UKand France which participated in 30.0, 17.8 and9.6 per cent of publications respectively in thethree-year period assessed.

Malaria research is a strong component of allresearch relevant to health or disease in develop-ing countries, representing an estimated 21 percent of worldwide publications in tropical medi-cine. However, the absolute level of malariaresearch activity is low relative to other areas ofbiomedical research and in relation to the globalburden of malaria disease: publications num-bered approximately 1000 a year and accounted

Executive summary

10 Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica

for just 0.3 per cent of all outputs in SCI annu-ally. By comparison, cardiology accounted for10.2 per cent, and arthritis and rheumatism 2.4per cent of world SCI publications in 1995.The low publishing activity in internationalmalaria research reflects the relatively smallglobal investment, which stood at aboutUS$100 million in 1998.

Kenya, Tanzania, Nigeria and The Gambiawere the highest publishing African countries inmalaria research in 1995–97, each producingmore than 50 papers. The most productive indi-vidual research programmes were located at theUK Medical Research Council Laboratories,Fajara, The Gambia; the KEMRI–WellcomeTrust collaborative programme in Kilifi andNairobi, Kenya; and the University of Ibadan,Nigeria. Seven centres published more than 20papers in the three-year period assessed.

Overall, African malaria research publica-tions show extensive international co-author-ship: 79 per cent of papers were found to involvecollaboration outside Africa, particularly withEurope and the USA, and few linkages acrossAfrica were observed. While this high degree ofcollaboration indicates productive links betweenlaboratory research in ‘Northern’ laboratories,and field and clinical studies in Africa, it alsoreflects dependence on foreign funding sourcesand on external expertise.

Direct survey of African malaria research lab-oratories provided a more detailed impression ofthe availability of human resources for researchand revealed the presence of a core of trained sci-entists currently engaged in malaria research. Atotal of 752 malaria researchers trained to atleast first degree level were identified in 54research centres across sub-Saharan Africa. Ahigh proportion (35 per cent) were trained toMaster’s level, while postdoctoral scientists andclinicians were also well represented (26 and 22per cent respectively). The majority of PhDgraduates held Master’s degrees and nearly halfof clinical researchers also held higher degrees.However, the 192 postdoctoral and 168 clinicalscientists identified were dispersed across 22countries so that the numbers of trainedresearchers per country were small. In addition,about one-third of research groups were led bynon-national scientists. Of the 313 individualquestionnaire respondents, 15 per cent werenon-African. The results, therefore, indicate a

strong need for additional African scientificleaders who are able to conduct innovative andindependent research, and play a key role incapacity-building efforts.

While numbers of trained personnel andpublications provide an indication of the level ofresearch activity, they are unable to measure theimpact and usefulness of that research. Citationindices of publications are commonly usedmeasures of research impact, which indicate theinfluence of published results on the scientificcommunity. African malaria research papers for1995–97 had a lower potential citation impactthan the international set of malaria papers forthe same period. However, the result primarilyreflects the highly clinical and applied nature ofAfrican research, as this type of research isknown to attract fewer citations than more fun-damental studies. Citations, therefore, do notprovide an accurate measure of the value of moreapplied research, and alternative methods arerequired.

Literature cited in national guidelines andpolicies for the treatment and control of malariafrom 11 African countries were examined toassess links between research and policies. Theresults indicated that it is clinical and in-countryresearch, often recorded in grey literature, thatinfluences policies rather than basic research.These observations would support investment inthe local research bases in developing countries,particularly in clinical and applied sciences.Analysis of national policies and guidelines is animportant potential method of demonstratingspecific outcomes from clinical and appliedresearch. However, there was a lack of a system-atic approach to citing scientific literature in thedocuments examined, and more widespread useof this approach would be dependent on coun-tries including full bibliographies in their policydocuments.

Investments in research and training indeveloping regionsA diverse set of funding organizations in indus-trialized countries support research and trainingin Africa, Asia and South America, as revealed bysurveys of funding agencies and of malariaresearch laboratories in Africa, and by analysis offunding acknowledgements on malaria publica-tions. These include governmental, non-govern-mental and commercial sources.

Executive summary

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 11

The most frequently acknowledged funderson African malaria research publications were theUNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programmefor Research and Training in Tropical Diseases(TDR), the Wellcome Trust, the Kenyan Med-ical Research Institute (KEMRI) and the UKMedical Research Council. Commercial fundingsources for African malaria research were notprominent: only Hoffman La Roche registeredmore than ten acknowledgements on publica-tions over a three-year period. Fourteen commer-cial companies were listed in the survey ofAfrican research centres as providing grants, butfunding was generally on a small scale.

Survey of funding organizations and ofAfrican malaria research laboratories indicatedthat training opportunities for developing-coun-try scientists are widely dispersed across manyorganizations from high-income countries.However, only a few funders provide substantiallevels of support, notably the Japan InternationalCooperation Agency (JICA), the EuropeanCommission (INCO-DC), the US NationalInstitutes of Health (NIH), and TDR. Otherrelatively prominent direct supporters of train-ing (excluding multilateral contributions)include Australian, Belgian, Danish, French,Swedish, Swiss Government agencies, theInternational Clinical Epidemiology Network(INCLEN) and the Wellcome Trust.

An aggregate expenditure by industrializedcountries of US$261 million for training devel-oping-country scientists in biomedical scienceand health was identified for the three-year peri-od 1995–97. This figure is low when comparedwith the figure of US$145 million invested in asingle year (1997) in developing biomedicalresearch expertise in the UK. Nevertheless, thereappears to be a growing international commit-ment to strengthening research capacity indeveloping countries: a 41 per cent increase inexpenditure by high-income countries wasobserved over the three-year period assessed.

Contributions to training by governments indeveloping regions were not broadly surveyed,but data were obtained from Brazil and SouthAfrica, which are by far the highest investors inresearch in their regions. The figures obtainedsuggest that expenditures by other countries inSouth America and sub-Saharan Africa are likelyto be very low.

The research base in Africa is stronglydependent on external investment: 88 per centof malaria research grants to African laboratoriesfor 1993–98 were from organizations outsideAfrica. For PhD training, 65 per cent of fundingacknowledgements were to agencies from devel-oped regions, and 17 per cent to African govern-mental or local sources. Many researchersreported funding their own degree studies.African governments contribute significantly tosupport for Bachelor’s degrees (over half in thegroup analysed), and to salaries of nationalresearchers (68 per cent of survey group). Localgovernment sources were also the highest indi-vidual category acknowledged for PhD andMaster’s training.

Career progression opportunities inbiomedical researchSurvey responses from 39 funding organzationsrevealed the broad range of training schemes inhealth and biomedical research offered by higher-income countries to scientists in developingcountries. However, these training opportunitiesare generally dispersed, with many funders pro-viding small numbers of awards annually.Training is often associated with specific pro-grammes and is not offered openly, thus limitingoptions for individuals seeking to identifysources of funding. Relatively small numbers oforganizations actively monitor the numbers andsuccess of training awards, illustrating the lack ofa coherent international approach to trainingscientists. Despite the large number of trainingschemes overall, there are few opportunities forscientists to develop their careers through thefunding schemes of a single organization, asmany funders target training at one level.

Most agencies focus their resources on partic-ular regions, and available data suggested thatAfrica and Asia are slightly favoured over SouthAmerica in terms of training opportunities.

The availability of international awards fordeveloping-country scientists at different stages ofcareer progression was assessed. It was found that:• Training attachments in overseas laboratories

and short courses are the most frequent typesof support provided by organizations in devel-oped countries, and accounted for a large pro-portion of overall identified expenditure.

• Very few organizations in high-income coun-tries provide support for Bachelor’s degrees.

Executive summary

12 Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica

• A large proportion (74 per cent) of organiza-tions surveyed provides support for Master’straining, although many provide only smallnumbers of awards annually. Over half of theidentified Master’s awards came fromINCLEN and the Belgian Agency forDevelopment Cooperation, and these awardswere focused in the areas of clinical epidemi-ology, public health and related disciplines,indicating that the availability of Master’straining in other disciplines is more limited.

• A smaller proportion of funders offers PhDtraining (just over half of those surveyed),but over 90 per cent of identified awardswere provided by the European Commission,TDR, US National Institutes of Health(NIH) and DANIDA. AusAID is an impor-tant supporter of training for Asian scientists,although available data were incomplete.Survey of African research centres also identi-fied L’Institut de Recherche pour leDéveloppement (IRD) and the FrenchMinistry of Cooperation as notable fundersof PhD training.

• Postdoctoral training is often provided inassociation with larger research programmesand few agencies provide opportunities forindividual postdoctoral scientists to apply forindependent research support. The US NIHand the Wellcome Trust were the mostprominent supporters of postdoctoral train-ing identified in the survey. African scientistscommented on the lack of availability ofresearch awards to develop the careers ofpostdoctoral scientists.

The survey of funders from high-incomecountries identified a total of 684 PhD awardsand 821 Master’s awards for 1995–98. By com-parison, in a single year (1997) there were an esti-mated 2101 PhD awards directed towards build-ing biomedical research expertise in the UK, acountry with a population of about one-seventy-fifth of the developing-country regions com-bined. This is equivalent to nearly 1000 timesmore PhD opportunities in the UK than in thedeveloping regions, relative to population size. Inview of the dependence of many developingcountries on external funding sources for post-graduate training, the overall conclusion is thatprovision of research training opportunities fordeveloping-country scientists is low relative to

opportunities in industrialized countries.These figures must of course be considered in

the light of the more limited availability of grad-uates to absorb training at higher-degree levelsin developing countries. However, comparativefigures for numbers of tertiary students and PhDawards per unit population in developing anddeveloped countries support the view that cur-rent PhD training in many developing countriesis restricted. In addition, three-quarters of scien-tists in Africa responding to the MIM surveyhighlighted the need for additional opportuni-ties at Master’s and PhD level.

Training mechanisms and infrastructureMost funding organizations link training tomajor research programmes that have receivedsupport through a competitive, peer-reviewedprocess, thus providing some assurance thattraining will take place in a strong intellectualenvironment. Funders also tend to focusresources on specific centres to develop facilitiesand a critical mass of people that will encouragehigh-quality science to flourish.

The survey of African malaria researchersrevealed that 90 per cent of Bachelor’s degreeshad been completed within Africa (81 per centlocally or self-funded), but just over half of post-graduate qualifications had been obtained whol-ly or partially outside the home country. Exter-nal training occurred most frequently in Europefollowed by the USA. The extent of overseastraining varied among countries, with moreresearchers receiving PhD training at home inNigeria, South Africa, Cameroon and Senegal.

Patterns of African scientific partnershipsand training sites are strongly moulded by fund-ing mechanisms, which reflect historical andlanguage associations and geographical proximi-ty. In many cases training is offered in the coun-try in which the donor organization is based.There are few funding mechanisms that supportlinkages between countries within developingregions. For example, France and the UK focustheir resources primarily on centres in Franc-ophone and Anglophone Africa respectively,contributing to a lack of interaction betweeninstitutes in these regions.

African survey respondents recognized thevalue of international partnerships as a mecha-nism for training and for technology transfer.They considered overseas training attachments to

Executive summary

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 13

be important in exposing developing-countryscientists to the scientific culture and facilities ofoverseas centres of excellence. However, they alsonoted that overseas training is not always relevantto the home research base, is expensive, and mayresult in researchers being attracted permanentlyaway from their home countries to locationswhere the facilities and career prospects areadvantageous. It was considered that local train-ing opportunities within Africa are not beingfully exploited, and further investment in Africantraining centres would be valuable to allowregional technology transfer and sharing ofresources. Funding agencies are increasingly rec-ognizing the benefits of using local and regionaltraining facilities, combined with shorter train-ing attachments in European or US laboratories,to develop sustainable and locally relevantresearch expertise.

Many of the most productive malariaresearch centres in Africa receive long-term sup-port from external funders and are relatively wellequipped, thus underscoring the importance ofa stable foundation from which to develop aneffective research programme. Over 90 per centof all African malaria laboratories surveyed hadcore laboratory facilities (freezers, centrifuges,incubators and microscopes). However, a highproportion of individual survey respondentscited lack of research funds or poor infrastruc-ture and laboratory facilities as major obstaclesto developing a research career in Africa. Africanresearchers also emphasized the critical impor-tance of good communication links in allowingthem to participate effectively in internationalresearch activities. The survey results indicatethat the communications revolution is success-fully reaching Africa as 90 per cent of laboratorieshad e-mail connections. The quality of electroniccommunications, however, was not assessed.

Adequate remuneration is a major factor insuccessfully retaining scientists in developingcountries. Nearly 70 per cent of African scien-tists surveyed received their salaries from localsources, but many commented that these salarieswere insufficient.

The present study identified the location andspecializations of a number of strong malaria

research centres across sub-Saharan Africa.Primary funding sources of these centres andinternational scientific partnerships have alsobeen analysed. This information should assistboth researchers and funders in identifying cen-tres which might be further developed for localand regional training, and for multicentre studies.

Research specializations: diseases and disciplinesResearch training schemes must aim to buildcapacity that is appropriate to national healthneeds and priorities. Many funding agencies tar-get resources on particular diseases or disciplines.For example, INCLEN focuses on developingexpertise in clinical epidemiology, and related dis-ciplines, while WHO/TDR focuses on eight tar-get tropical diseases. Training is also often linkedto larger research programmes, whose researchfocus will strongly influence the balance ofexpertise generated by training activities. There isa need for overarching mechanisms to matchcapacity development to research priorities.

The major focus of current malaria researchin Africa is on clinical studies, epidemiology,intervention trials and health services research.Only 3 per cent of African malaria publicationsin SCI and MEDLINE (1995–97) related tobasic science studies of the malarial parasite, and7 per cent to fundamental studies of mosquitovectors, or vector taxonomy, ecology or behav-iour. Eighty-one per cent of African publicationsreported studies involving human subjects, com-pared with 46 per cent for malaria papers inter-nationally. Direct survey of malaria research lab-oratories in Africa confirmed the strong presenceof expertise in clinical and field-based research:for example 132 scientists trained in publichealth and 88 in epidemiology were identified.The results also suggested that facilities andexpertise in molecular biology, biochemistry andimmunology are increasing (gel electrophoresisand PCR equipment was present in 76 and 58per cent of laboratories respectively). Thereappeared to be a lack of expertise in biostatistics,sociology and economics: 37, 36 and 12 individ-uals, respectively, were identified with trainingin these disciplines.

Executive summary

14 Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica

RECOMMENDATIONS FORTHE WAY FORWARD

This report has gathered information from dif-ferent perspectives on the availability of trainingopportunities for scientists in developing coun-tries, and on the current status of human andinfrastructural resources for malaria research inAfrica. In view of the enormity of the challengein strengthening research capacity in developingcountries, funding organizations and govern-ments face some difficult decisions on wherebest to direct their resources for maximal effect.The results of this review point to a number ofareas of weakness in current international researchtraining activities and to specific conclusionsrelating to malaria research in Africa. The keypoints are summarized here together with recom-mendations for consideration by the MultilateralInitiative on Malaria, by other coordinating bod-ies such as the Roll Back Malaria Project ofWHO, and by individual funding organizationsin the developed and developing worlds.

International investment and coordinationin research training➤ The research bases in many developing coun-tries are currently heavily dependent on foreigninvestment, but the success of any capacity-building activities is ultimately dependent onlocal commitment to scientific research. Fundingorganizations internationally and governments ofdeveloping countries must, therefore, worktogether to build sustainable research expertise toaddress clearly identified national health researchpriorities. Coordinated and long-term invest-ment by both national governments and externalfunders is needed to improve infrastructure andfacilities. More formalized, overt partnershipsmay be required for maximal effect.

➤ Current training offered by higher-incomecountries to developing-country scientists isgenerally fragmented and inadequately moni-tored. Greater efforts are required to coordinateactivities internationally and to monitor theeffectiveness of training programmes in order tomaximize the impact of resources in building acore of appropriately skilled scientists. Thiscoordination role is one that might be played bythe Multilateral Initiative on Malaria.

➤ Science is a global activity and the migrationof scientists to high-income countries is a prob-lem that must be addressed in order to build sus-tainable research bases in developing countries.National research institutes must be able com-pete successfully to retain scientists against bothoverseas institutes and the local private sector.Serious consideration must be given by localgovernments to the provision of adequate salarystructures to reward productive scientists. Moreexternal funders might also consider provision ofsalary supplements to scientists who competesuccessfully for research awards.

➤ The aggregate expenditure by industrializedcountries in training scientists in developingregions appears low relative to population inthese regions, and relative to expenditure ontraining scientists in industrialized countries.This is particularly significant in view of theobserved dependence of developing countries onforeign investment in research training. A smallincrease in the proportion of overall budgetscommitted by larger research and developmentorganizations to research training could poten-tially have a substantial overall impact.

➤ Accurate measures of the impact of clinical andapplied research are required to provide data tosupport investment in this type of research. Theanalysis of research cited in health policy docu-ments is a potentially effective method of assess-ing the influence of research in informing clinicalpractice or disease control strategies, but effectiveimplementation is dependent upon the inclusionof full bibliographies in policy documents.

Career progression opportunities inbiomedical research➤ The majority of African scientists completeBachelor’s degrees in their home countries.Universities in developing regions, therefore,have the responsibility of ensuring thatBachelor’s degree curricula are of high quality,reflect national scientific needs and generate aninterest in scientific research.

➤ Current availability of awards for PhD andMaster’s training in many developing countriesfrom both local and international sources is verylimited, even after taking into consideration thelower numbers of graduates in developing as

Executive summary

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 15

compared with developed countries. Greateropportunities are likely to be beneficial in devel-oping a critical mass of independent scientists.

➤ The wider availability of grants and fellowshipsto support the research projects of individual sci-entists would provide an incentive for scientists todevelop careers in research and may contribute tothe development of key scientific leaders.

➤ There is a relatively large overall investmentby high-income countries in providing shorttraining attachments in overseas countries,workshops and short courses. These trainingmechanisms are potentially important, but theymust be appropriately targeted and monitoredfor maximal effect. There is a need for a moredetailed analysis of the nature of current activi-ties of this type.

Training mechanisms and infrastructure➤ Training patterns are strongly influenced byrigid funding mechanisms that often involvecollaborations between specific high- and low-income countries. The establishment of morevaried funding formats would enable greaterdiversity in international scientific partnershipsfor more effective use of top-class training cen-tres, irrespective of their location. Mechanismsto support linkages within developing regionsare also required to allow sharing of regionalresources and expertise, perhaps through moreformalized research and training networks andmulticentre approaches.

➤ A high proportion of scientists from lower-income countries is currently trained overseas.Greater investment in developing countries isrequired to establish top-quality local andregional training centres, which can play a rolein building sustainable and relevant nationalresearch expertise. This approach would assist inbuilding productive collaborations betweenneighbouring countries and may also prove to bemore cost-effective in the long-term.

➤ The balance of expertise generated by trainingis determined primarily by funding policies ofindividual agencies that target particular diseasesor disciplines, and by the focus of large researchprogrammes with which training is associated.There is a need for mechanisms, at national andinternational levels, to assess the overall distribu-tion of training across different research areasand hence assist in mapping capacity develop-ment to national research priorities.

➤ Stronger links between the research and con-trol communities are required to facilitate orien-tation of research agendas to practical healthneeds, and to promote rapid uptake of researchresults into policy and practice.

Malaria research capacity in Africa➤ Malaria research is a particular strength ofsub-Saharan Africa and the current study hasidentified and characterized the most productiveresearch centres. These centres represent a strongbase for the development of a network of sitesfor training and for multicentre studies.

➤ A core of training African scientists engagedin malaria research has been established, but thenumbers of trained scientists are relatively smalloverall and there appears to be substantialdependence on external expertise from Europeand North America. Continuing efforts arerequired to train African scientific leaders forthe future.

➤ African centres appear to lack expertise inhealth economics, social sciences, and biostatis-tics, and these disciplines may require specificstrengthening in view of their importance inoptimizing the delivery of healthcare and diseasecontrol interventions.

➤ This review has provided baseline data onresearch activity, infrastructure and trained personnel which can be used to measureprogress in strengthening malaria research capa-bility in Africa.

Executive summary

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 17

1

1.1 APPROACHES TO THE STUDY

The MIM review includes the following analyti-cal approaches:1. A survey of training opportunities in health

and biomedical research offered by interna-tional funding organizations to scientists inAfrica, Asia and South America.

2. An assessment of current malaria researchcapacity and training in Africa including:• analysis of African malaria research

publications, in the context of globalpublications, to assess relative outputs ofcountries and institutes, collaborationlinks, subfield strengths and weaknesses,and funding sources;

• analysis of journal impact factors forAfrican malaria research publications toassess the potential influence of the report-ed research on the scientific community;

• analysis of literature cited in African nationalmalaria treatment policies to elucidate theresearch guiding policy formulation;

• a survey of African malaria research labora-tories to assess current research expertise,facilities and training pathways, and toobtain opinions on needs and solutions incapacity development in Africa.

Where possible, the study made use of pre-existing information contained within theDirectory of the African Malaria Vaccine TestingNetwork (AMVTN)1 and the ‘Inventory ofresources and activities’ produced for theInternational Conference on Malaria, held in

Dakar, Senegal, in 1997. However, the majorpart of the review presents novel bibliometricand survey information.

1.2 BACKGROUND

The quality and productivity of scientificresearch in the lower-income countries of theworld currently lags far behind that ofindustrialized nations, and the lack of localresearch capacity has seriously hindered progressagainst health problems in developing regions.Estimates from the United Nations Educat-ional, Scientific and Cultural Organization(UNESCO, 1996) suggest that Africa, LatinAmerica and the Middle East together accountfor only 13 per cent of the world’s scientists,with the majority being concentrated in theWestern industrialized nations. There is,however, growing awareness of the need tostrengthen indigenous research capacity toenable developing countries to respond to theirown health challenges in a more effective and sustainable way (e.g. COHRED, 1990).Scientific research has had a dramatic impact inimproving health this century in many regionsof the world, through the development of newtreatments and control interventions, andthrough providing knowledge to enable peopleto maintain their own health. Research has alsobrought economic benefits through avertingdisease and decreasing healthcare costs.

It has been estimated that about half of allfunds for research relevant to developing coun-tries comes from local governments, with the

This report has been prepared by the Wellcome Trust as part of the activities of theMultilateral Initiative on Malaria (MIM). A major objective of this initiative is tostrengthen and sustain malaria research in African countries through partnershipswith scientists internationally. However, it was recognized early in the establishmentof the initiative that very little information is available on current research capabilityin developing countries. Organizations involved in MIM agreed that such data werecrucial to inform discussions on potential options for strengthening long-termresearch capability. Hence, it was decided that a review of current research trainingschemes should be carried out, together with an assessment of human andinfrastructural resources for malaria research in Africa. The Wellcome Trust, as thecoordinator of MIM during 1998 and a major funder of malaria research, undertookto carry out this study, drawing on experience from a previous review of internationalmalaria research (Anderson et al., 1996).

Introduction

1 www.amvtn.org

18 Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica

remainder coming from external sources(Michaud and Murray, 1996). Successfulstrengthening of the science base in developingcountries is therefore heavily dependent uponexternal investment. In view of the enormity ofthe challenge and limitations in resources, it isevident that inputs from organizations interna-tionally need to be focused and coordinated inorder to achieve maximal effect.

On a broad level there has been a recentmove towards evidence-based approaches toresearch investments. Individual organizationsare placing greater emphasis on evaluating theirfunding policies and assessing how their contri-butions integrate into an international context.There are also ongoing activities to analyse glob-al resource flows into health research, that willfacilitate rational investment in relation to dis-ease burden estimates (e.g. the WHO Ad HocCommittee on Health Research, 1996; and theGlobal Forum for Health Research, Geneva). Inaddition, initiatives such as the MultilateralInitiative on Malaria are providing a structuralframework for coordinated international invest-ments by scientific funding organizations.

Analytical data to inform decision-makingon strengthening research in developing coun-tries are not readily available. Comparative fig-ures on human resources in different regions aredifficult to obtain and highly incomplete(UNESCO, 1998). Some data specifically relat-ing to malaria research capacity have been gath-ered previously, but these have not been subjectto detailed analysis (e.g. AMVTN Directory andan Inventory produced for the InternationalConference on Malaria, Dakar, Senegal, 1997).Reviews focusing on research training have beenlimited in scope and have tended to focus onspecific issues or schemes (e.g. Doumbo andKrogstad, 1998; TDR, 1999; INCLEN InternalReview, 1999). What is lacking is overviewinformation on the extent and nature of interna-tional training schemes for scientists in develop-ing countries, and the degree to which they pro-vide a coherent training framework.

This study aimed to complement existinganalytical efforts and to fill some of the gaps incurrently available information. A large body oforiginal data has been gathered and analysed, andthe main findings are being published in thisreport as a resource for funding agencies interna-tionally. While a major part of the report focuses

on malaria research in Africa, many of the con-clusions are of broader relevance to buildingresearch capacity in the poorer countries of theworld. The data on current malaria research pro-ductivity also provide indicators to enable futuremonitoring of the success of programmes to trainscientists in developing countries. Finally, andimportantly, the report is directed towards devel-oping country scientists themselves to raiseawareness of current training opportunities andof the location of centres of malaria researchexpertise across the African continent.

1.3 HEALTH RESEARCH IN DEVELOPINGCOUNTRIES

Health problems in Africa and in other low- andmedium-income regions remain a significantchallenge: with the persisting burden of avoid-able childhood and maternal diseases, a diverseand changing threat from infectious diseases,and a rapidly emerging epidemic from noncom-municable diseases and injury. Malaria is onedisease in particular that continues to be a majorproblem, despite previous eradication cam-paigns (see below).

Overall, it is estimated that more than 90 percent of the world’s burden of preventable mor-tality occurs in low- and middle-income coun-tries. Nevertheless, these health problems ofdeveloping countries receive relatively littleattention, with most global resources beingdirected towards diseases of higher-incomecountries. Of the global investment in healthresearch and development (about US$55 billionannually), only 5–10 per cent is thought to bedevoted to health problems in low- and middle-income countries, (Michaud and Murray,1996). There is a strong need, therefore, for arational, coordinated international response todiseases of lower-income countries, which willcontribute towards redressing this imbalance.

Within the context of international researchactivity, scientists working in developing coun-tries have a critical contribution to make. Astrong indigenous science base is required forcountries to define and address their own healthresearch priorities, thereby contributing towardsimproving health and towards social and eco-nomic development.

Introduction1

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 19

Investment in science in developing coun-tries over the last 50 years has been successful inbeginning to establish national scientific com-munities with internationally recognized scien-tific leaders. For example, financing of researchin sub-Saharan Africa increased sevenfold in1970–85 and the number of people engaged inresearch by a factor of ten (Gaillard and Waast,1993). Despite this progress, developing coun-tries still contribute only a small fraction of theworld scientific publications: an estimated 6.5per cent of the total (OST, 1997).

Across the developing nations there areregional and country-specific patterns andtrends in scientific research. Figures derivedfrom the Science Citation Index (SCI) andCompumath databases provide some indicatorsof scientific activity (UNESCO, 1998). LatinAmerica accounts for about 1.5 per cent of sci-entific outputs in all disciplines, while sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 0.8 per cent, China1.6 per cent, India and Central Asia 2.1 per centand South-East Asia just 0.1 per cent. The worldshare of publications outputs from sub-SaharanAfrica dropped by 19 per cent between 1990and 1995, while the outputs from China andLatin America increased substantially (+38 and+17 per cent respectively) and the outputs fromAsia remained relatively steady.

The different regions also have different dis-ciplinary specializations: sub-Saharan Africa isstrongest in applied biology/ecology and weak-est in basic biology, chemistry, physics and engi-neering. Conversely chemistry, physics and engi-neering are relative strengths of China, India andCentral Asia. Latin America is strongest inapplied biology and ecology. It should be noted,however, that the databases used for these analy-ses are biased towards English-language journalsand do not take into account local and regionaljournals that are particularly prominent inChina and Latin America, and which might pro-vide more accurate insight into locally relevantresearch capacity. The results, however, do give afair representation of the broad international sci-entific visibility of the different regions.

Public investment in research and develop-ment (R&D) by developing countries is the low-est in the world, illustrating the lack of localresources to sustain scientific activity. Similarly,the available figures for trained scientific person-nel in developing regions are also very low relative

to industrialized countries.The above data on scientific activity in devel-

oping countries are a strong indication that theseregions remain ill-equipped to respond to themajor challenges posed by local health problemssuch as malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS andupper respiratory tract infections.

1.4 PUBLIC HEALTHSIGNIFICANCE OFMALARIA

Malaria is a major and increasing cause of diseaseburden globally and is estimated to be responsi-ble for more than one million deaths and almost300 million clinical cases annually worldwide(See ‘Rolling Back Malaria’ in the WHO WorldHealth Report, 1999). The disease has its greatestimpact in sub-Saharan African where an estimat-ed 90 per cent of cases occur, often in young chil-dren. The economic impact of malaria in Africais substantial. Despite successes in controllingmalaria in the 1950s and 1960s, recent yearshave seen a resurgence due to a combination offactors. There is growing resistance to currentantimalarial drugs in many areas, includingmultidrug resistance. Increasing insecticideresistance, environmental changes and humanmigration, often the result of political instabilityand wars, are further contributory factors. Areduced commitment to control programmes insome regions has also had the serious conse-quence of exposing populations with decreasedimmunity to the threat of malaria.

Over the past few years there has been agrowing momentum to address the problem ofmalaria. Strong international commitment hasdeveloped, and action has taken place in a rangeof different sectors. For example in Amsterdamin 1992, a Revised Global Malaria Strategy wasapproved by the health ministers of severalmalarious countries (WHO, 1993). This wasfollowed in 1996 by discussions between theWHO Regional Office for Africa (AFRO) andthe World Bank, leading to plans for a malariacontrol programme to be targeted at malariousareas across the African continent. At the sametime, discussions were under way in the researcharena to develop a more cohesive and coordinat-ed international approach to scientific researchagainst malaria, leading to the establishment of

Introduction 1

20 Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica

the Multilateral Initiative on Malaria. Mostrecently, WHO, has recognized the impact ofescalating mortality from malaria andannounced a major new programme to ‘RollBack Malaria’ (Nabarro and Tayler, 1998),which is global and aims to add value to andcoordinate all efforts to control malaria.

1.5 THE MULTILATERALINITIATIVE ON MALARIA

Origins and objectivesThe Multilateral Initiative on Malaria (MIM) isan international alliance of organizations andindividuals that aims to maximize the impact ofscientific research against malaria. Enhancingcoordination and collaboration, mobilizingresources, promoting capacity building inAfrica, and encouraging research and controlcommunities to engage in fruitful dialogues aremajor emphases of MIM.

The origins of MIM go back to a meeting held in 1995 between a number oforganizations supporting scientific research inthe developing world. From these discussionsemerged a recognition that ongoing activitieswere fragmented with different organizationsindependently supporting research activities atvarious locations across the developing world.There was agreement that a mechanism wasrequired to orchestrate these individual activitiesinto a more coherent approach, which wouldhave a stronger and more sustainable impact.Malaria in Africa was selected as an importantfocus to develop a mechanism to promotegreater coordination amongst the range ofdifferent players; and so the concept of the Multilateral Initiative on Malaria (MIM)came into being. The original overarching goalwas defined as “to strengthen and sustainthrough collaborative research and training, thecapability of malaria-endemic countries inAfrica to carry out research required to developand improve tools for malaria control”.

A defining step in the evolution of MIM wasa congress convened in Dakar, Senegal, inJanuary 1997 where the scientific communitywas asked to identify the major research ques-tions that must be answered in order for theproblem of malaria to be addressed effectively(Butler, 1997a; Mons et al., 1998). The meeting

was successful in highlighting specific researchpriorities, as well as some broad recurring needsthat cut across different subject areas. The recommendations arising from this meetinghave played a crucial role in guiding the activities of MIM. Follow up meetings during1997 in The Hague (Butler, 1997b; Gallagher,1997) and London (Butler, 1997c; Williams,1997) then defined more clearly the areas forconcerted action and set out the strategies foraddressing priorities. At the London meeting,the Wellcome Trust accepted the nomination toact as a coordinator of the activities of MIM foran initial period of 12 months. One of the keypriorities set at this meeting was to carry out areview of malaria research capacity in Africa.This priority, amongst others, was actively pursued by the Wellcome Trust, leading to thepreparation of this report.

Key outcomes and future directionsMIM has been involved in a diverse range ofactivities since its establishment in 1997 (Davies,1999). Importantly, the Initiative has played asignificant role in drawing additional funds intomalaria research: overall funds committed tomalaria research increased from an estimatedUS$85 million in 1995 (Anderson et al., 1996)to a figure of well over US$100 million in 1999.

MIM is particularly concerned with promot-ing global coordination and collaboration in themalaria research community to address scientificneeds and opportunities. To this end, it has facil-itated links not only between scientists, but alsobetween the funding organizations supportingthem. MIM meetings, newsletters and websites2

have been important channels for enhancingcommunication amongst partners. Furthermore,the Malaria Foundation International has playeda prominent role in raising awareness of theimmense health and economic impacts of malaria.

There have also been unprecedented oppor-tunities for interactions between scientists acrossAfrica. The Dakar Conference in 1997 was a sig-nificant event in bringing together scientistsfrom all regions of sub-Saharan Africa and, fol-lowing the success of this meeting, MIM made acommitment to establish a regular forum of thiskind. The first MIM African MalariaConference took place in Durban, South Africa,in March 1999 and was attended by over 850delegates. It was made possible through the gen-

Introduction1

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 21

erous sponsorship of a broad range of fundingorganizations and commercial companies. TheConference was successful not only in facilitat-ing scientific collaborations across Africa andinternationally, but also in strengthening linksbetween the research and control communities.

MIM has also catalysed the establishment offormalized collaborations across Africa.Multicentre approaches can make a particularcontribution by linking fragmented and isolatedresources into networks which have the poten-tial for much greater impact on malaria.Furthermore, single sites are not sufficient toobtain definitive answers in certain types ofstudies where large sample sizes are required,necessitating instead that standardized reagentsand methodologies are applied at multiple sites.For example, a network linking five sites acrossAfrica has been established to study severemalaria in children and particularly to evaluatenovel treatments and develop new interventions.

To fulfil the need for standardized and well-characterized malaria research reagents identi-fied in Dakar, a Malaria Research and ReferenceReagent Repository has been established withfunding from NIAID. This facility will maintainand distribute reagents such as parasite strains,mosquitoes, genetic material (e.g. DNA probes)and antibodies.

The immense opportunities offered to Africanscientists by electronic communications technol-ogy and the Internet have been recognized byMIM, and the US National Library for Medicinewas nominated to lead an initiative in this area.Much improved connectivity has been achievedin Mali, and at two sites in Kenya, while plans forsites in Tanzania and Cameroon are advancing.

As part of its commitment towards buildingresearch expertise in Africa, MIM was responsi-ble for the establishment of the new Task Forcefor Malaria Research Capability Strengtheningin Africa, which is administered by theUNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programmefor Research and Training in Tropical Diseases(TDR) and is funded from several differentsources. This Task Force provides support forresearch training in association with large multi-centre studies across Africa.

Overall, MIM has helped to energize a newphase to improve approaches to internationalmalaria research through creating new partner-ships, and through providing a practical frame-

work and point of reference to guide the activi-ties of the international research community.The new working relationships establishedbetween the major funders are also having aninfluence in improving coordination in thebroader field of biomedical and health researchin the tropics. In the future MIM will continueto tackle key priorities, as well as bottlenecksimpeding progress. It is also committed to work-ing with the WHO Roll Back Malaria Project toensure smooth integration of malaria researchand control activities.

Introduction 1

2www.wellcome.ac.uk/mim

and www.malaria.org/mim

www.mimcom.net

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 23

2

2.1 METHODS

2.1.1 Survey of funding agenciesFunding agencies providing support for devel-oping-country scientists were identified throughliterature searches, Internet searches and directo-ries of grant-making organizations. The studyfocused primarily on funding organizationsbased in established market economies. Someinformation was obtained from governments oflower-income countries, although these sourcesof support were not broadly surveyed.

A questionnaire was sent to organizationsrequesting details of award schemes throughwhich individuals from developing countriesmight receive funding. Information for the peri-od 1995–98 was requested on:• numbers of awards to developing-

country scientists;• expenditure on awards;• training level of awards;• the regional breakdown of awards into

Africa, Asia and South America;• proportion of awards for malaria

research training.

As the questionnaire format was not neces-sarily compatible with the records kept, organi-zations were encouraged to submit as much rele-vant data as possible in a format convenient fortheir records. All organizations that contributeddata were given an opportunity to check theaccuracy of the presentation of their data in thereport prior to its publication.

The following points should be noted:• Although every effort was made to obtain

comparable data, it cannot be assumed thatall funding agencies classify their awards inthe same way.

• Accurate figures for expenditure on trainingwere sometimes difficult to identify wheretraining was provided as part of a larger

research or development programme.• The review focused on organizations that

administer training schemes and consequent-ly funding agencies that contribute funds tosecondary organizations for training may beless well represented in the review. Wherepossible, contributions from one organiza-tion to another are specifically stated anddouble counting of the funds avoided.

2.1.2 Data analysisExpenditure totals were converted to US dollarequivalents using annual average exchange rates1

for each of the years 1995 to 1997. Figures for1998 were converted according to the exchangerate for June 30 1998. Expenditure was classifiedaccording to the financial year of the particularorganization contacted. The specific time periodcovered in a financial year varies between organi-zations. Where the financial year spans morethan one calendar year, the year assigned wasthat containing the greater proportion of thefinancial year. For example, the financial year ofthe Wellcome Trust runs from 1 October to 30September, therefore FY 1995 refers to the peri-od from 1 October 1994 to 30 September 1995.

Awards were classified according to the fol-lowing categories:• Bachelor’s: undergraduate studies,• Master’s: postgraduate degree or studies,

including Diplôme d’Études Approfondies;• PhD: doctorate awarded for original research

in a subject;• postdoctoral: studies, research or professional

work above the level of doctorate;• training attachment: specific skills or techni-

cal training not necessarily leading to theaward of a formal certificate. Training isoften, but not always, provided at a researchinstitute in a developed country;

• diploma: courses and specializations where acertificate is awarded.

This chapter presents the results of a survey of international research trainingopportunities in biomedical sciences and health for researchers in developing countries.The aim was to obtain an analytical overview of existing training schemes in order toassess the availability of support at different levels of training, in various disciplines,and across different geographical regions. Such data are essential to guide futuredirections in strengthening research capability in developing countries. The informationshould also be a valuable resource for scientists seeking support for research training.

Training opportunities

1International Monetary Fund

(1997) International Financial

Statistics Yearbook,Vol. 50.

24 Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica

Training opportunities2

Awards were classified into three geographi-cal regions: Africa, Asia and South America.Although several organizations supportedresearch projects and training in Eastern Europeas part of their international programmes inhealth, these awards were excluded from theanalysis. The review focused on research trainingopportunities and career progression in biomed-icine and health. It should be noted, however,that in some instances it was difficult to separateresearch training from other more general typesof training in health. The term ‘developing-country scientist’ is used broadly in this report torefer to laboratory and field-based researchers,health professionals, clinicians, sociologists,economists etc.

2.2 RESULTS

A total of 54 funding organizations wereapproached in the MIM survey and 39 organiza-tions (74 per cent) responded with relevant infor-mation on research training activities for develop-ing-country scientists in biomedicine and health.Of the responding organizations, 13 provided fulldata, 16 provided partial data and ten providedqualitative information. Respondents includedgovernmental and non-governmental organiza-tions, private foundations and internationalorganizations (see Annex 2 for contact details).

The results are presented according to the geo-graphical location of the organizations surveyed:

2.2.1 USA and Canada2.2.2 Europe2.2.3 Asia and Australia2.2.4 International organizations2.2.5 Developing countries

Within each section, organizations are classi-fied as governmental or non-governmental. Asfar as possible, information is presented in astandardized format, although there is somevariation according to the type of informationprovided by individual organizations. The head-ers in brown indicate the direct expenditure ontraining developing-country scientists unlessotherwise stated.

2.2.1 USA and Canada

US Government

The Department of Health and Human Services(HHS) is the US Government’s principal agencyfor protecting the health of all Americans andproviding essential human services. There areeight Public Health Service Operating Divisionswithin the HHS. Two of the divisions, theNational Institutes of Health (NIH) and theCenters for Disease Control and Prevention(CDC), have schemes of support for developing-country scientists.

US National Institutes of Health (NIH)US$69.8 million in FYs 1995–98The National Institutes of Health is the world’spremier medical research organization whosemission is to uncover new knowledge that willlead to better health for everyone. The NIHbudget for 1999 was US$15.7 billion. WithinNIH, the Fogarty International Center (FIC)and the National Institute of Allergy andInfectious Diseases (NIAID) develop andadminister research training programmesfocused on developing countries. These pro-grammes support research and training in a widerange of subjects including infectious diseases(with emphasis on HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis andmalaria), environmental/occupational health,population-related issues, drug discovery andmedical informatics. Table 2.1 shows theschemes of support offered by the FIC andNIAID that are open to scientists in developingcountries and the expenditure per scheme in1995–98. As well as these targeted schemes,NIH offers open grant programs to US sndnon-US citizens.

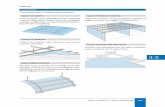

Expenditure by the FIC and NIAID ontraining developing-country scientists increasedby 80 per cent in FYs 1995–98 (Figure 1).Within these training programmes, US$1.4 mil-lion (2 per cent of total) was devoted to malaria.The FIC and NIAID support training at allstages of career progression, but particularly atPhD and postdoctoral levels, and via trainingattachments (Figure 2). In general, academic

FY1995 FY1996 FY1997 FY1998

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 25

Training opportunities 2

Table 2.1 The Fogarty International Center (FIC) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) award schemes forscientists in developing countries.

Award scheme Remit Expenditure in Year began1995–98 (US$ million)

1 AIDS International Training and Laboratory, clinical, epidemiological 37.6 1988Research Program (AITRP) and public health aspects of HIV/AIDS

2 International Cooperative Identification of novel therapeutics from 10.4 1993Biodiversity Groups indigenous flora and fauna;

preservation of biodiversity

3 International Training and Research Emerging infectious diseases 8.1 1997Program in Emerging Infectious (non-HIV/AIDS research)Diseases (ITREID)

4 International Training and Research Reproductive biology, and social and 4.9 1995Program in Population and Health demographic correlates of fertility

5 International Training and Research Pollution (air, land and water) 6.2 1995Program in Environmental and and occupational hazardsOccupational Health

6 Tuberculosis Training and TB training (supplement to the ITREID 1.1 1998Research Program and AITRP schemes) (1998 only)

7 International Training in Medical Computer-assisted information processing 0.6 1998Informatics and communications (focus on Africa) (1998 only)

8 Tropical Medicine Research Awards to institutions in disease-endemic 6 1990Centre (TMRC)* areas to support interdisciplinary research

programmes on parasitic and other tropical infectious diseases

9 International Collaborations Awards to support research partnerships 14 1979in Infectious Diseases between institutions in USA andResearch (ICIDR)* disease-endemic countries

10 Actions for Building Capacity Research training in the context of specific Awards to be 1999scientific themes made in 1999

11 Malaria research training Malaria training (supplements to ITREID, Awards to be 1999AITRP and NIAID grants) made in 1999

Fogarty International Center

NIAID

25

20

15

10

5

0

Figure 2.1 Fogarty International Center (FIC) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

(NIAID) expenditure on research training for developing-country scientists.

US$ million

* NIAID administered schemes that primarily focus on research programmes, but include a training component (approximately 20 per cent of the programme budget).Programmes 1, 3, 5 and 6 have some activities in Eastern European countries, including the former Soviet Union.

Total expenditure in FYs 1995–98 was US$69.8

million.These figures are restricted to training

costs and exclude expenditure on major

programmes of research through the ICIDR and

TMRC awards (see Table 2.1)

26 Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica

training is conducted in USA and field researchin disease-endemic areas. The FIC and NIAIDalso conduct training workshops in developingcountries. In FYs 1995–98 nearly 400 workshopswere organized, with over 28 000 participantsfrom Africa, Asia and South America (Table 2.2).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)CDC’s mission is to promote health and qualityof life by preventing and controlling disease,injury and disability. Its budget for 1999 wasUS$2.7 billion. CDC supports developing-country scientists in two ways:• The Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS). The

EIS is a two-year postgraduate fellowship pro-gramme run by CDC for health professionalsinterested in the practice of epidemiology.During 1996–98, 17 developing-country sci-entists participated in the programme (Africa5, Asia 5, South America 7).

• Training as part of CDC internationalresearch projects, principally at the field sta-

tions in Kenya (CDC/KEMRI) andGuatemala (MERTU/G). In Kenya, studentsmay receive training at Master’s and PhDlevel while working on CDC research proj-ects. In Guatemala, the field station is anintegral part of the Universidade del Valle deGuatemala. Undergraduates participate inresearch projects, and opportunities for train-ing at Master’s and PhD level exist. CDC hasno dedicated award schemes for developing-country scientists and consequently expendi-ture on training varies according to the avail-ability of research projects and the level offunding per project.

The US Agency for InternationalDevelopment (USAID)USAID is the foreign assistance arm of the USGovernment. USAID supports applied researchwhich includes biomedical, epidemiological,behavioural, economic and clinical research. Themajority of research (80–90 per cent) is conductedin developing countries by national researchers.

Training opportunities2

Postdoctoral 216 (21.8%)

PhD 174 (17.6%)

Master’s 33 (3.3%)

Bachelor’s 6 (0.6%)

Training attachment

560 (56.6%)

Figure 2.2 Fogarty International Center (FIC) and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

(NIAID): Classification of support in FYs 1995–98 by training level and region.

Number of individuals trained = 989 (data for FY 1998 is provisional)

Table 2.2 The Fogarty International Center (FIC) and National Institute of Allergy and InfectiousDiseases (NIAID) workshops in FYs 1995–98. (1998 data are provisional)

Region Number of Number of workshops participants

Africa 103 2735

Asia 50 1488

South America 244 23 838

Number of individuals supported

Africa 322 (32%)

Asia 284 (29%)

South America 383 (39%)

Strengthening Health Research in the Developing Wor ld Malar ia Research Capacity in Afr ica 27

USAID funds some developing-country institu-tions directly (e.g. the International Centre forDiarrhoeal Diseases Research, Bangladesh), butthe majority of research is managed by a granteeinstitution which is usually US based, or byWHO. These institutions in essence operatesmall grants programmes. The cost and durationof support varies according to the research pro-gramme. The US-based funder normally playsthe role of technical adviser and only participatesin the research in a limited number of cases.

Capacity building is an important componentof the research programmes with efforts focusedon proposal development, workshops, short-termtraining in new methodologies and technologies,training in data analysis, and on developing skillsfor translating research results into policy andprogrammes. Networking and effective commu-nication are also considered important compo-nents of the research. Both in-country and inter-national networks have been fostered, the lattermainly through multi-country/multi-site inter-vention trials. Almost all research training at thepostgraduate level is accomplished within thecontext of a research project. USAID expendi-ture on health research in total in 1995–98 wasapproximately US$158 million.

US Department of Defense – Walter ReedArmy Institute of Research (WRAIR)The WRAIR is the largest of six medical researchlaboratories under the US Army’s MedicalResearch and Material Command. It is the USDepartment of Defense’s lead agency for infectiousdisease research and a major source of researchsupport for medical product development.

Training of developing-country scientists byWRAIR has an emphasis on antimalarial drug

discovery and drug resistance, and vaccine devel-opment. Support is predominantly at postdoc-toral level, through the National ResearchCouncil Associateship awards (funded byWRAIR) and funds from NIAID/FIC andWHO. Short research training attachments inmalaria drug and vaccine development are alsosupported. In general, training is conducted atthe WRAIR unit in Washington DC, USA,although opportunities for local training alsoexist in the six overseas laboratories in Brazil,Peru, Thailand, Indonesia, Egypt and Kenya.Table 2.3 shows the number of developing-coun-try scientists trained by WRAIR in 1995–98.

US non-governmental organizations