Stern Business Spring / Summer 2004

description

Transcript of Stern Business Spring / Summer 2004

STERNbusinessS P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 0 0 4

T h e L a t e s t M o d e l s

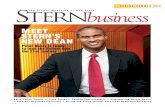

Robert NardelliRemodels Home Depot

Arthur Levitt Calls for New Role Models

Stern’s Nobel Laureate Debating Europe’s Financial Future

Unlocking Corporate BoardsSuper Models: Inner-city

Entrepreneurship Social Responsibility

Organizational Silence

a l e t t e r f r o m t h e deanBusiness schools

straddle the realms oftheory and practice.Any sound businesseducation provides stu-dents with an under-standing of the basicprinciples – of every-thing from accounting

to macroeconomics – and an appreciation of howissues play out in the world. An excellent businesseducation affords students the opportunity to dealwith both theory and practice at the highest level.

In our fields, we frequently construct models thatdescribe how things are supposed to work, or how wethink they should work. But we constantly test themby examining data, by working with and talking topractitioners, and by incorporating observations andexperience into our thinking.

At NYU Stern, the boundaries between the cam-pus and the business world are porous. And we havethe great geographic fortune to be located in NewYork, which is home to an unrivaled concentration ofbusinesses. As a result, our faculty and students havethe opportunities to validate their theories and mod-els with industry counterparts who are at the tops oftheir respective fields.

For example, NYU Stern’s proximity to WallStreet – and the prospect for collaboration it affords– was one of the factors that attracted Robert Engleto Stern in 2000. Professor Engle, was named aNobel Prize winner in economics last fall for hiswork in developing and applying models to analyzeand forecast volatility. Every day, on trading floors afew miles to the south of our campus, investors andanalysts put his models to work.

New York is home to a stunning array of non-profit organizations – symphonies and operacompanies, giant foundations and hospitals, andsmall neighborhood economic development groups.

All these organizations can benefit from the adapta-tion of management best practices, and our studentscan benefit from learning more about how theseorganizations work – and about the work they do.That’s why we developed the Stern Consulting Corps(SCC) program.

Under this innovative consulting internship pro-gram, which involves about 50 students each semes-ter, NYU Stern MBA students put into practice theskills and knowledge they gain in the classroom tohelp revitalize small and minority-owned businessesin New York City. SCC serves as the umbrella for aunique partnership among NYU Stern, non-profitorganizations such as the Harlem Small BusinessInitiative, the Robin Hood Foundation and SEED-CO; and management consulting firms such as BoozAllen Hamilton and A.T. Kearney. Working in part-nership, the non-profit organizations provide SternMBA students with their assignments, and volun-teers from the consulting firms serve as mentors onthe projects. In turn, businesses and non-profits ben-efit from the Stern MBA students’ expertise in every-thing from strategic and financial analysis to mar-keting and operations.

We take seriously our responsibility to be activeand productive members of a larger community. Andwe believe that these initiatives – and our ongoingefforts to attract the highest quality faculty and stu-dents – are among the many factors that make NYUStern a model for other business schools.

This issue of STERNbusiness features a greatdeal of innovative thinking on the part of NYU Sternfaculty members, and on the part of the many busi-ness and government leaders who participated inevents at Stern last fall. I invite you to explore it.

Thomas F. CooleyDean

STERNbusinessA publication of the Stern School of Business, New York University

President, New York University � John E. SextonDean, Stern School of Business � Thomas F. CooleyChairman, Board of Overseers � William R. BerkleyChairman Emeritus, Board of Overseers � Henry KaufmanAssociate Dean, Marketing

and External Relations � Joanne HvalaEditor, STERNbusiness � Daniel GrossProject Manager � Lisette ZarnowskiDesign � Esposite Graphics

Letters to the Editor may be sent to:NYU Stern School of BusinessOffice of Public Affairs44 West Fourth Street, Suite 10-160New York, NY 10012http://www.stern.nyu.edu

contents S P R I N G / S U M M E R 2 0 0 4

36Pocket ProtectorFormer SEC Head Arthur Levitt, Jr.,Discusses Reform

40Currency EventAn NYU Stern Panel Debates Europe’s Economic Future

44 Endpaper by Daniel GrossFord’s Most Enduring Model

Illustrations by:Dave CutlerGeorge AbeTimothy CookMichael GibbsBryan LeisterKen OrvidasTheo RudnakGlenn MitsuiMichael CaswellRobert O’Hair

T h e L a t e s t M o d e l s

SternChiefExecutiveSeries

InterviewRobert Nardelli, The Home Depot, Inc.Page 2

6 Model Behaviorby Daniel Gross

8 Ties That BindThe Problems Of Interlocked Boardsby Eliezer M. Fich and Lawrence J. White

14Going For Brokers

How Entrepreneurs NegotiateThe Inner-City Landscape

by Gregory B. Fairchildand Jeffrey A. Robinson

20Nobel PursuitInterview with NYU Stern’s Robert Engle,2003 Nobel Laureate in Economics

26 Responsible PartiesRoundtable Discussion on Corporate Responsibility

30 Sounds Of SilenceWhy Employees Don’t Speak Upby Elizabeth Wolfe Morrisonand Frances J. Milliken

CH: What did you find when

you got to Home Depot?

RN: It was a very rapid transi-

tion from General Electric to

Home Depot. It took place in

about a week. It was the first

time in the history of this com-

pany that an outsider was

CEO. Home Depot is a very

young company. We're the

youngest retailer to reach $30

billion, $40 billion, $50 billion.

And this year we’ll reach $60

billion. It is a company that had

grown up with its co-founders.

But, my assessment was that

what got us here wouldn't get

us where we wanted to go in

the future. We had a very

decentralized business model.

What I found was that the fun-

damental infrastructure needed

for sustainability in a variety of

economic cycles was missing.

The decentralization that had

served the company well was

a disadvantage going forward.

CH: At that point, you had

about 1,000 stores, each oper-

ating as a separate entity?

RN: By design. The co-

founders would go on a road

trip and say "If you've got a fax

from corporate, tear it up. If

you get a voice mail, dump it.

You're out here running the

business.” This was a company

in start-up mode for 22 years.

What I found was a need for

some very strong infrastructure

to put some pilings underneath

this house called The Home

Depot.

When I was transitioning in,

there was a tremendous

amount of anxiety. If there is

one message I can leave you

here tonight, it is think about

succession planning. I was an

outsider. This is a company

Robert Nardelli is Chairman, President and ChiefExecutive Officer of The Home Depot, Inc. With morethan 1,600 stores in North America and 2002 salesof $58.2 billion, Home Depot is the world's largesthome improvement retailer and the second largestretailer in the U.S.

Prior to joining Home Depot in December 2000, Mr.

Nardelli was President and Chief Executive Officer at

General Electric's power systems unit, where he trans-

formed the division into a $20 billion worldwide leader

in the energy industry. He began his career at GE in

1971. Mr. Nardelli received his B.S. in business from

Western Illinois University and earned an MBA from

the University of Louisville. Since Mr. Nardelli took the

helm at Home Depot in 2000, the company has seen a

28 percent increase in annual sales, and a 42 percent

increase in annual net earnings.

sternChiefExecutiveseries

Robert Nardellichairman, president and chief executive officer

The Home Depot, Inc.

2 Sternbusiness

that prided itself on internal

promotions, a family.

CH: How did you handle it?

RN: I have moved 11 times in

my career. I had gone through

it before. About 75 percent of

what you learn is portable. The

rest is something you have to

immerse yourself in. This was

like taking a dry sponge and

immersing it in a bucket of

water. You just have to absorb

a plethora of things. While at

the same time you're learning,

you have to continually calm

the waters that this new guy is

not going to wreck the culture

and bring order and discipline

to a very entrepreneurial envi-

ronment. When I came in

December of 2000, I could not

send an e-mail to every store

manager. We have fixed that,

of course.

CH: While you were going

through this transition did you

hit some snags?

RN: When I stepped in, this

was a company that had had

eight consecutive quarters of

downward spiraling compara-

tive sales. I visited nine differ-

ent buying offices and I found

different pricing, different terms

and conditions. So we put in

vendor buying agreements.

We went from negative $800

million in cash when I got there

in December, to $5 billion in

cash today. That's after a $2

billion stock buy-back last year.

And we will achieve another

billion-dollar stock buy-back

this year. We increased divi-

dends last year over 20 per-

cent. We've increased divi-

dends this year over 20 per-

cent and a quarter early. It's

working, but it wasn't without a

lot of skepticism. We've had to

make a lot of changes. We

changed merchandising. We

changed operations. We

changed systems. You are

either going to be e-literate or

you'll be illiterate. We're plan-

ning for the long term but we're

delivering on the short term

with some tremendous tech-

nology. We are reinvesting 100

percent of every hour of

increased productivity. We'll

spend about $400 million this

year in technology, and we'll

do that for the next two to

three years to get caught up.

CH: You've also made a lot of

people changes.

RN: I think you have to identi-

fy your strategy and then

organize to support it. The real

differentiator is resource allo-

cation, both human capital and

physical capital. At the leader-

ship level we are going

through a major transforma-

tion. But one of my strongest

division presidents is a 20-year

associate. He started as a lot

attendant. I think we're getting

a wonderful blend of experi-

ence and culture to form this

new team.

CH: What competitors worry

you and what competitors do

you learn from?

RN: I have a great deal of

respect for Wal-Mart. A couple

of months ago Tom Coughlin,

the head of Wal-Mart’s U.S.

stores, invited me down to the

Saturday meeting at

Bentonville and introduced me

as “the enemy.” I admire them

because I think they have

great logistics, they've got

great operating systems, they

have tremendous commitment

and passion on the part of

their associates. I think Target

does a wonderful job in pres-

entation. I think one of the

things that has happened to

Home Depot is success breeds

complacency. Complacency

breeds arrogance. Arrogance

causes failure. Consumers

today are stressed. We want to

provide them with what I'll call

the orange experience. When a

customer walks into Home

Depot, it's aesthetically pleas-

ing. It's well lit. It's shoppable.

It's navigable. We have to have

a restlessness towards improv-

ing upon everything we do.

CH: Can you talk a little bit

about your own background?

RN: I had a wonderful set of

parents who are first-genera-

tion Americans. They instilled

in me a tremendous work

ethic. I had one older brother.

As a younger sibling, you're

always in competition. I felt a

need to compete both in high

school and in college. I had

great experiences in those

academic environments, and I

learned a lot about myself in

athletics. I played high school

football, got a scholarship and

played college ball. I enjoyed

the fact that you had to do

your job as an individual, and

you had to make sure the

team was coordinated. So it's

all about you, and it's about us.

It gave me a great advantage

from a leadership standpoint.

Never ask anybody to do

something you wouldn't do.

I've always believed in horizon-

tal promotions to make your

base as strong as it can be.

For the trauma that it created,

the wonderful thing about

being new to Home Depot was

that I wasn't tied to the past. I

had a respect for the past. The

toughest thing to change is

what you put in place.

CH: You spent a great many

years at GE, but at one point,

you left GE for a while and

went to a smaller company.

Tell us about that.

RN: It was a gut-wrenching

decision. I'm a second genera-

tion GE-er. Between my Dad

and me, we've got over 50

years with General Electric.

Leaving was emotional for me.

And, I never left with the notion

that I would come back. Then I

got a call a couple of years

later to come back to GE,

which was one of the best

days of my life. In typical Jack

Carol Hymowitz, senior editor at The Wall Street Journal, interviewed Mr. Nardelli.

Sternbusiness 3

“ We had a very decentralized business model . . .

The decentralization that had servedthe company well was a

disadvantage going forward.”

tremendous amount of corpo-

rate governance to start with.

Before it became the vogue or

mandatory, we required every

director to walk our stores so

they had a sense about what

was going on out there. Every

board meeting had an outside

director's meeting without me

there. Every director has to

stand for re-election every year.

Those are some of the things

we already had in place and

we're continuing to do it. In the

last two and a half years I

have personally set up teams

of directors to visit our division

presidents without me. Every

quarter we're rotating our

directors so that they have

unfiltered access to our leader-

ship team. We have put in a

whole new compliance review

process. We set up an entire

new corporate compliance

process where employees can

go straight to the head of our

audit committee if they have

concerns about corporate gov-

ernance. And, we have com-

Welch fashion, of course, I

was exiled. I went up to

Toronto and ran the Canadian

appliance manufacturing com-

pany for a year. He could not

bring me back and put me in a

position that might reinforce

that that is the way you get

promoted. So I went up and

did my penance in Toronto. I

did that for nine months and

then came back and took over

GE transportation in Erie, and

then a couple of years later

took over GE power systems

in Schenectady.

CH: What was it like to be in

the succession race at GE for

several years and then not get

the top job?

RN: It's the Super Bowl, the

last two minutes for two years.

It's very tough. The pressure,

the environment. You know

that you're being looked at

through a magnifying glass

every day. For me it was about

"How do I take a $5 billion

business and broaden it?" We

grew the business from $5 bil-

lion to $20 billion. We were the

strongest cash generator in the

company. We were the most

profitable segment in the com-

pany. We had a phenomenal

time during that three-and-a-

half-year period.

CH: You have said that being

a leader, you're judged on your

accomplishments, not on the

4 Sternbusiness

a few days because of busi-

ness demands? You have to

make tradeoffs. You've got to

set priorities.

CH: What are the global

opportunities for Home Depot?

RN: Let's talk about North

America. We'll open our 100th

store in Canada this month. In

Mexico we went from zero to

number one in 18 months.

That's a $12.5 billion market. If

we look to Europe, I don't think

it's any surprise real estate is

pretty well taken. If we go to

Europe, it would be an oppor-

tunistic acquisition of someone

that is in the market over

there. If you look to Asia,

you're going to go to China. It

is where the population and

the economy are booming.

The investments that U.S.

companies have made in

China are creating a tremen-

dous financial base over there.

I think when it's done, there

will be three trading blocs.

There will be the European

trading bloc. There will be the

Americas. There will be Asia.

Somehow we've got to be able

to coexist. We've got to create

the globalism that allows three

major trading blocs to get

along. China is where we were

at in the Industrial Revolution,

head down, working hard.

They are aspiring to be where

we are today.

CH: What are you trying to do

at Home Depot to assure good

governance?

RN: I'm very fortunate. I have

a great board. We had a

time you put in. But you do put

in an awful lot of time? What is

your schedule like?

RN: To use a sports analogy,

at the end of 60 minutes, it's

not about how hard you

played, it's about whether you

won or not. For me, having

moved a number of times, I

always felt that I was in a

learning curve. You have to

continually challenge yourself.

My goal is not to meddle, but

to understand. The more I

understand, the more process-

es and systems I can put in

place so that we have a con-

tinuum of performance

improvement. Retail is very

demanding. In the industrial

sector on Friday nights, you

kind of wind down. In retail,

you build to a crescendo. The

transactions happen Friday,

Saturday and Sunday.

I met my wife while we were at

school, in 1971. We've been

together since then. She has

been unbelievably supportive.

I've got a great family. I've got

one daughter and three sons.

They have been supportive. I

think it's a cop-out for you to

look back and say, "could

have, should have, would

have." You know exactly what

you're doing. Are you going to

take four, five hours for a

round of golf, or are you going

to spend time with one of the

children you haven't seen for

"For the trauma that it created, thewonderful thing about being new

to Home Depot was that I wasn't tied to the past."

municated it so that every

associate, every leader has

the comfort that they can get

to the board.

CH: What do you look for in

young managers when you're

hiring?

RN: What we're looking for is

someone that has demonstrat-

ed a tremendous amount of

energy, who has an ability to

energize, who has demon-

strated the ability to balance

academic and social. In this

business, you've got to love

people. We're looking for

people who want to continue

to learn, who understand the

importance of individual

accountability, but with the

ability to think laterally.

Student questions

Q: Will Home Depot be

expanding into Manhattan?

RN: We are going to put two

stores in Manhattan. There are

three customers that we're

looking to serve here. First are

the residential customers, peo-

ple that live in this area. The

second customer that we are

excited about is the building

superintendent. It's going to be

very important to provide mer-

chandise and service to that

building superintendent. The

third customer that we're excit-

ed about is the commuter. The

commuter shops in the morn-

ing, shops at noon, shops at

night, and then has it deliv-

ered. We may elect to deliver

out of one of our local stores.

Q: What sort of macroeco-

nomic trends are you seeing

now from your seat at Home

Depot?

RN: One of the first things I

did when I got there was put

together my own economic

model. We look at about 50

different indices. So what are

we seeing? We are seeing

sequential improvement in the

economy today. One, because

of the low interest rates we

see tremendous family forma-

tion relative to housing. It is

the American dream. People

want to own a home. We're

more excited about housing

turnover than we are new

housing at this point. We're

seeing consumer confidence.

What we saw post-9/11 was

people were staying home.

They were doing projects, but

not big projects. But we're see-

ing bigger projects come back

now. We have seen, since the

fourth quarter through the sec-

ond quarter of this year, a sig-

nificant improvement in overall

same-store sales. We saw

sequential improvement May

to June, June to July, July to

Sternbusiness 5

August, August to September.

We'll be reporting our earn-

ings in a couple of weeks, and

we're feeling good about the

momentum and the direction,

not only of our business, but

the sector that we serve.

Q: How do you retain a quali-

ty workforce?

RN: What are we doing to

make sure that our associates

don't feel the need for third-

party representation? One, we

pay above industry average,

at least 15 percent against

market wages in those com-

munities. Two, we offer one of

the best benefits packages.

We’ve implemented benefits

for part-time associates for

the first time in the history of

the company. We accelerated

tuition reimbursement. We put

in what I'll call success shar-

ing. That means if you hit the

sales plan and other metrics

within your store, you'll get a

financial reward. Sixteen mil-

lion dollars went to associates

through that program. I firmly

believe that when you invest

in an associate, that skill is

portable. We hope they stay

with us and use it but it's

something they can take

wherever they go. We have a

real passion, a real commit-

ment about attracting, moti-

vating and retaining a high-

performance workforce. �

“Before it became the vogue ormandatory, we required every directorto walk our stores so they had a sense

about what was going on out there.”

hich comes first, theory or practice?Theory – whether it was Charles

Darwin’s Galapagos-inspired writings onevolution, or Sir Isaac Newton’s apple-

induced discovery of gravity – is informed by practice andobservation. And yet practices frequently follow from the-ory. Think, for example, of how management models likeTotal Quality Management or Six Sigma have altered thestrategy, actions, and bottom lines of massive companies.

In fact, innovation is the product of a constant cyclewhereby theory and practice are continually informed byone another. As a result, bridging the gap between theo-reticians and practitioners is crucial. And one of the bestways for doing so is by constructing, using, and revisingmodels. Models represent the marriage of real-worldobservation to imaginative thinking. And they provide aframework for teaching, for discussion, for inquiry, forunderstanding, and, ultimately, forenacting change.

Each year, Sweden’s Nobel PrizeCommittee recognizes researcherswhose theoretical work finds appli-cations in the real world. And lastyear, NYU Stern finance professorRobert Engle received a share of the2003 Nobel Prize in Economics fordeveloping an innovative and highlyuseful economic model called “Autoregressive ConditionalHeteroskedasticity.” In English? “It’s a way of trying tomodel and describe and forecast this thing we call volatil-ity,” Engle said in a town hall meeting held in his honorlast fall. (“Nobel Pursuit,” pg. 20)

Currencies have been among the more volatile assetclasses in the past year. After years of strength, the dollarhas weakened substantially against currencies such as theBritish pound and the euro. The advent of the euro in 2000was the latest step in a continuing effort to build a newmodel for European political, social and economic reloca-tions. But last fall, the future of Europe’s united fiscal andmonetary policy seemed in doubt as countries faced a con-flict between meeting Europe-wide financial mandates and

internal policy goals. Amid the crisis atmosphere, apanel sponsored by NYU Stern and BlackwellPublishing, Inc. gathered to discuss present andfuture prospects for Europe and the Euro. (“CurrencyEvent,” pg. 40) While the panel’s members, whoincluded NYU Stern Dean Thomas Cooley, largelyagreed on the diagnosis of Europe’s ills, they offered

different – and provocative– cures.

When something breaksdown – a monetary system,a car, or a system of corpo-rate governance – it’s timeto go back to the drawingboard. And in the past fewyears, a series of board-room scandals and failings

have exposed the flaws in the ways publicly held com-panies are governed. In their article, (“Ties ThatBind,” pg. 8) Lawrence White and Eliezer Fich dissectthe current model and analyze how the make-up ofcorporate boards, and chief executive officers’ rela-tionships with corporate directors, influence crucialoutcomes such as compensation.

As Chairman of the Securities and ExchangeCommission from 1993 to 2001, Arthur Levitt, Jr.implemented a series of reforms aimed at alteringsuch relationships. In remarks prepared for theCitigroup Leadership and Ethics Program at Stern,(“Pocket Protector,” pg. 36) Levitt called for a“cultural change” in the way directors and CEOs

6 Sternbusiness

“Models represent the marriage of real-world observation to

imaginative thinking. And theyprovide a framework for

teaching, for discussion, forinquiry, for understanding, and,

ultimately, for enacting change.”

W

M O D E L B

ILLUSTRATION BY GEORGE ABE

approach their jobs. “We need private sector leaders at alllevels to dedicate themselves to creating a culture ofaccountability and foster an ethic of service,” he said.“We need to change who our role models are.”

Whistle-blowers – employees within organizationsthat see unethical behavior and alert associates, regula-tors, or law enforcement agencies – are frequently cru-cial to creating accountability. But in corporations today,forces discourage employees from speaking out. “Inmany organizations, employees know the truth aboutcertain issues and problems facing the organization yetthey do not dare to speak that truth to their superiors,”as Elizabeth Wolfe Morrison and Frances J. Milliken note.In their article, (“Sounds of Silence,” pg. 30) drawing onsociological and psychological insights, they propose amodel for understanding the phenomenon of organiza-tional silence and suggest means through which man-agers can turn up the volume.

Whether you own a house or run a company, you’recontinually in a state of remodeling. Robert Nardelli, thechief executive officer of The Home Depot since 2000, issimultaneously trying to remodel the home improvementchain’s massive store base while figuring out how best tohelp Americans remodel their homes. “We had a verydecentralized business model,” said Nardelli, who spokeas part of the Stern CEO Series. (Interview, pg. 2). “WhatI found was that the fundamental infrastructure neededfor sustainability in a variety of economic cycles wasmissing. The decentralization that had served the com-pany well was a disadvantage going forward.”

Part of Home Depot’s current growth strategy is to

push into more heavily populated urban areas like NewYork. Indeed, the company plans to build a large storein East Harlem. In so doing, Home Depot is joining along list of companies that are investing in whatGregory Fairchild and Jeffrey A. Robinson call“America’s emerging markets.” (“Going for Brokers,”pg. 14). Fairchild and Robinson examine the phenome-non of white entrepreneurs and business owners operat-ing in central city locations. Their suggestion: socialbrokers – institutions and individuals that can bridgethe gaps between minority neighborhoods and non-minority business people – can help facilitate growth,profits, and development.

y opening stores in areas that have beenhistorically underserved, companies likeHome Depot can both do good and do well.Indeed, there’s growing evidence that thereputed conflict between companies’ social

responsibilities and their responsibilities to shareholdersto maximize profits may not be so great after all. Apanel discussion jointly sponsored by NYU Stern andResources for the Future brought together environmen-tal activists and executives to discuss the ways in whichbeing green can translate into more green in the corpo-rate coffers. (“Responsible Parties,” pg. 26) Pursuing agoal of zero waste and emissions has “saved us abouttwo billion dollars in energy costs,” said Paul Tebo, vicepresident of health, safety, and environment at DuPont.“Working on energy and keeping it flat while you growis a terrifically good strategy.”

Understanding business models – and creating newmodels for understanding business – is an importantcomponent of the work done at NYU Stern by students,by faculty, by administrators, and by the practitionerswho are part of the larger Stern community. In chal-lenging conventional wisdom, in bringing newinsights to bear on longstanding issues, this issue ofSTERNbusiness should stand as, well, a model for otherperiodicals.

D A N I E L G R O S S is editor of STERNbusiness.

Sternbusiness 7

B

E H A V I O R

8 Sternbusiness

Ties That

n the recent wave of corpo-rate scandals, from Enron toTyco, poor corporate gover-nance structures have clearlybeen a contributing factor.The tales of excess compensa-tion, poor capital allocation,

and, occasionally, outright theft,have shone a harsh spotlight on therelationships between chief execu-tive officers and the boards of direc-tors. Too frequently, directors – whoare supposed to represent the share-holders – have acted in ways thatenrich CEOs and other favoredexecutives while impoverishingcommon shareholders.

On many boards, two (or more)directors serve together on a differ-ent company’s board. For example,General Motors Corp.’s April 2002proxy revealed that the GM boardhad two mutual interlocks: CEOJohn F. Smith, Jr., and DirectorGeorge M.C. Fisher were also direc-tors on the board of Delta Air Lines,Inc.; and Smith and Director AlanG. Lafley were also on the board ofthe Proctor & Gamble Co. (whereLafley is the CEO). We dub these

I

Sternbusiness 9

ILLU

STR

ATIO

N B

Y M

ICH

AE

L G

IBB

S

When corporate directors serve together on multiple boards, the chief executive offi-

cers tend to earn more money and enjoy longer tenures. Such mutual interlocks are

plainly good for the bosses. But are they good for shareholders? Not necessarily.

By Eliezer M. Fich and Lawrence J. White

locks for several decades. And atfirst it appeared that interlocks werea sign of weakness. In one of the ear-liest such U.S. studies, economistPeter Dooley in 1969 found thatless-solvent firms were likely to bedirector-interlocked with banks.Later studies also reported thatfirms with high debt-to-equityratios, or that had an increaseddemand for capital were likely tohave interlocks. The reason:Financially stressed firms may seekto add bank officers to their boardsto receive more favorable considera-tion. Or banks may demand boardseats so they can monitor firms moreclosely.

Organizational behavior expertshave examined the extent to which aboard is an instrument of manage-ment interests. Some have arguedthat companies use board interlocksas a mechanism to improve con-tracting relationships, or to reducethe information uncertainties cre-ated by resource dependenciesbetween firms. This stream ofresearch suggests that the composi-tion of boards, including interlocks,

associations “mutual interlocks.”And in a sample of 366 large com-panies, 87 percent had at least onemutual interlock in 1991.

Director interlocks have clearconsequences for shareholders. Ourempirical analyses show that CEOcompensation tends to increase andCEO turnover tends to decreasewhen the CEO’s board has one ormore pairs of board members whoare mutually interlocked withanother company’s board. Why? Onthe one hand, mutual interlockscould be an indication of and a con-tributor to CEO entrenchment, fromwhich higher compensation andlower turnover naturally follow. Onthe other hand, mutual interlocksmay indicate the strengthening ofimportant and valuable strategicalliances. And the higher CEO com-pensation and lower turnover maybe a just reward for orchestratingsuch alliances. We believe that thefirst interpretation is more accurate.

Director InterlocksResearchers from several disci-

plines have been looking into inter-

Bind

TIES THAT BIND

is largely determined by the effortsof CEOs to influence the selection ofnew directors so that they areresponsive to that particular CEO’sinterests.

Financial economists have exam-ined interlocks as well. KevinHallock of the University of Illinoisfound that CEOs serving in employ-ee-interlocked firms earn highersalaries than they otherwise would.Nevertheless, existing researchhas not documented a connectionbetween director interlocks and totalCEO compensation. And in our sur-vey of previous studies, we did notfind any associations between inter-locks of various kinds and firm per-formance. That leads us to believethat interlocks aren’t designed toserve a firm’s strategic goals, anddon’t serve them in practice.

Compensation and TurnoverSeveral recent studies have

examined the relation between topexecutive compensation and boardcomposition. And they report mixedresults. For example, some authorshave found a positive associationbetween CEO compensation and thepercentage of outside directors onthe board. Other studies have foundno relation between a board majori-ty of outside directors and top man-agement compensation. The level ofincentive-based executive compen-sation appears to be positivelyconnected with firm performance,and incentive-based compensationappears to be used more extensivelyby outsider-dominated boards.

Other scholars have found aninverse relation between the proba-bility of a top management changeand prior stock price performance.After poor firm performance, CEOsare more likely to be dismissed if theboard of directors has a majority ofoutsiders. Empirical analyses indi-cate that the probability of top man-agement turnover is reduced if thetop executives are members of thefounding family or if they own high-

er levels of stock.Executive turnoveris also negativelyrelated to the own-ership stake of offi-cers and directors inthe firm and positively related to thepresence of an outside blockholder.Other studies have found that thelikelihood of CEO departure isinversely associated with both thedollar value of stock option compen-sation in relation to cash pay andthe amount by which a CEO’s com-pensation is higher than would beexpected from comparisons with thecompensation of other CEOs. Butthus far, no study has considered thepossible effects that boards withmutual director interlocks have onCEOs’ total compensation andturnover.

The DataWe looked at CEO compensation

and CEO turnover for 452 industri-al firms, first compiled by NYUStern professor David Yermack.These firms were drawn fromForbes magazine’s lists of the largest500 U.S. companies in categoriessuch as total assets, market capital-ization, sales, or net income. Thedata set includes all companiesmeeting this criterion at least fourtimes during the 1984-1991 period.Compensation data were collectedfrom the corporation’s SEC filings.Directors who were full-time com-pany employees were designated as“inside” directors. Individuals close-ly associated with the firm – forexample, relatives of corporate offi-cers, or former employees, lawyers,or consultants, or people with sub-stantial business relationships withthe company – were designated as“gray” directors. All the rest weredesignated “outside” directors. Wealso drew on the data assembled byKevin Hallock, who analyzed 9,804director seats held by 7,519 individ-uals in 1992. We took as our finaldata set the 366 industrial firms

for the 1991 proxy season thatappeared in both the Yermack andthe Hallock data sets. (Utility andfinancial firms were excluded fromthe study because government regu-lation may lead to a different role fordirectors.)

In order to examine how directorinterlocks may affect CEO compen-sation, we used a measure of totalremuneration that included salaryand bonus, other compensation, andthe value of option awards whengranted. We believe that this sum isa more accurate measure of whatboards intended to pay, which couldbe different from what CEOs earn,since CEOs often exercise optionsearly, thereby sacrificing a signifi-cant portion of the award’s value.

As an estimate for CEO turnover,we used a dependent variable thatwas set equal to one if a CEO leavesoffice during the last six months ofthe current fiscal year or the first sixmonths of the subsequent period. Inorder to control for retirement-relat-ed voluntary departures, we includ-ed in the analysis the CEO’s age.Turnover events occurred in 9.0 per-cent of the sample (thirty-threefirms).

Considering InterlocksThe key explanatory variable of

this study was the number of mutu-al interlocks on the firm’s board.While two boards can be interlockedif they share one director, they aremutually interlocked if they share atleast two directors. For any givenboard, a director could be part ofmore than one pair of mutual inter-locks, so it is quite possible that aboard may have a greater number ofmutual interlocks than directors. Inour sample of industrial firms,board sizes ranged from four to 26,

10 Sternbusiness

“After poor firm performance,CEOs are more likely to be dis-missed if the board of directors

has a majority of outsiders.”

with an average of 12.18. The num-ber of mutual interlocks rangedfrom zero to 42, with an average of12.15.

Other independent variables usedin the study were based on theirlikely relevance and effects on CEOcompensation and CEO turnover, asestablished by other authors. As innumerous other studies, Tobin’s Q(the market value of assets dividedby the replacement cost of assets)was used as a proxy for the growthopportunities of the firm.

Table 1 presents descriptive sta-tistics of the key variables in thisstudy and their correlation with thenumber of board director interlocks.As seen, the mean number of direc-tors who are CEOs of other firms is1.94. This result is similar to thatreported by James Booth and DanielDeli, who found the mean to be 1.87

for 1989-90 data. The mean num-ber of outside directors serving onthe board was 6.94, which is alsoconsistent with the previous litera-ture.

Two HypothesesIf the CEO dominates the selec-

tion process of directors to theboard, and if the CEO is in fact fill-ing the director positions with sym-pathetic members, then we wouldexpect a positive associationbetween the fraction of these favor-able board members and the com-pensation of the CEO. In otherwords, our first hypothesis stipulatesthat boards with a larger number ofmutual director interlocks will pay ahigher compensation package to theCEO. Our second hypothesis statesthat there is an inverse associationbetween the presence of mutual

interlocks and the likelihood of CEOdeparture.

What do the results show? Thecorrelations reported in Table 1suggest the existence of a relation-ship between the number of mutualdirector interlocks and the compen-sation of the CEO. It is not surpris-ing that larger boards have moreinterlocks and that a preponderanceof interlocks appears to be positive-ly connected with outside directorsand with directors who are CEOs ofother organizations. Mutual directorinterlocks appear to be curtailed byclose ownership and governancestructures. Our results show a nega-tive and significant correlationbetween this variable and the indi-cators for CEO-as-founder and fornon-CEO chairman.

Since director interlocks couldjust be indicators of strategic powerrelationships between firms at thehighest level, it cannot be automati-cally concluded that CEOs andinterlocked directors exploit net-works of board memberships fortheir personal gain simply becausethese multiple board affiliationsexist. In fact, CEOs could berewarded with additional compensa-tion and long job durations for suc-cessfully establishing mutual inter-locks that serve the strategic goals ofthe firm.

But the data show a significantnegative relationship between thenumber of mutual interlocks and thenumber of “gray” directors, many ofwhom could represent companiesthat have supplier or customer rela-tionships with the company. Thisnegative relationship reinforces ourskepticism as to the likelihood thatthe mutual interlocks serve thestrategic goals of the firm.

Extra CompensationTo test our first hypothesis, we

ran an ordinary least square regres-sion to estimate the effect that mutu-ally interlocking boards have on thetotal compensation of the CEO.

Sternbusiness 11

TABLE 1: DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS FOR KEY VARIABLES

CEO Characteristics and Compensation

Board Composition

*** Significant at the 1% level. s

Mean

12.152

12.177

3.943

6.940

1.294

1.943

58.269

0.023

1099.000

388.354

775.313

9.103

26.000

Variable

Number of mutually paireddirector interlocks

Board size

Inside directors

Outside directors

Gray directors

Directors who are CEOsof other firms

CEO’s age

CEO’s percentage of stockowned

CEO’s salary + bonus(in thousands of dollars)

CEO’s other compensation(in thousands of dollars)

Value of options when granted(thousands of dollars)

Tenure as CEO (in years)

Tenure in the firm (in years)

Standarddeviation

8.852

3.075

1.989

3.012

1.501

1.667

6.612

0.063

662.323

803.518

1739.000

8.533

12.027

Correlation withnumber of interlocks

1.00

0.537***

-0.039

0.660***

-0.175***

0.565***

0.016

-0.296***

0.156***

0.193***

0.197***

-0.187***

0.134***

These calculations took into accountfactors such as interlocks, firm size,tenure of the CEO, firm perform-ance, and stock ownership of theCEO. The results of this estimationare presented in Table 2. As expect-ed, the number of mutual directorinterlocks is found to be significantand positively associated with totalcompensation. This finding suggeststhat the links created by themutual interlocking relationsbetween boards actively benefit theCEO. In other words, with the aidof mutual interlocks, CEOs are ableto extract significantly larger com-pensation packages from their firms.The robustness of this result isupheld through further investiga-tions of the components of theCEO’s pay package.

When we repeated the analysisusing the natural log of only the sumof the CEO’s salary and bonus as thedependent variable, the coefficientfor mutual directors was positiveand significant. That suggests thateven just the sum of the CEO’s basicsalary and bonus tends to increaseas a consequence of the mutualdirector interlocks. In fact, we foundthat a mutual interlock adds anaverage of $143,000 (approximate-ly 13 percent) to the average CEOsalary and bonus.

The evidence presented in Table2 is in line with the view thatmutual interlocks may indeedassist the CEO in extracting lucra-tive remuneration packages fromthe firm. The networks and trafficof influences created by mutualinterlocking directorships haveprobably been utilized by CEOs inexerting control over the majority ofboard members. This finding sug-gests that directors may not be mak-ing decisions that benefit the firm’sshareholders the most. Mutuallyinterlocking directorships could beweakening the control mechanismsput in place to ensure that directorsfulfill their fiduciary duty and act inthe best interest of the shareholders.

When we ran other regressionswith these data we found that stockoption compensation appears not tobe judiciously used by boards incompensating their CEOs in thepresence of mutual interlocks. Webelieve this reflects cronyism andweakens the board’s monitoringfunction. This interpretation is con-sistent with the view of academicsand corporate governance activistswho perceive interlocks generally ascorrupt. Thus, although other studiesfind that markets react favorably tothe adoption of stock option plans tocompensate top executives, we find

that stock options can be misused ifthe board’s monitoring activities areweakened by interlocks.

Other results in these regressionsare consistent with the previous lit-erature. We found that CEO pay isinversely related to the fraction ofequity held by the CEO. And aseconomists Sherwin Rosen, CliffordW. Smith, Jr., and Ross L. Wattshave found in other studies, we findthat large companies and firms withgreater growth opportunities paymore to their CEOs. A company’snet-of-market stock return wasfound to have a positive and signifi-cant association with total CEOcompensation, consistent with pre-vious studies.

CEO TurnoverTo test our second hypothesis, we

investigated whether the presence ofmutual interlocking directorshipsdecreases the board’s ability to mon-itor the CEO, thereby decreasing thelikelihood that the CEO will depart.We analyzed the data, includingCEO and company characteristicsthat should be associated with theprobability of turnover. MichaelJensen and Kevin Murphy have sug-gested that one obvious CEO featurelikely to affect the turnover processis age. To control for this influencewe included the CEO’s age in theestimation. And to control for firmperformance, we included the firm’scurrent and previous year stockreturns net-of-market as well as thecurrent period return on assets.Further control variables includedproxies for growth opportunities(the ratio of research and develop-ment {R&D} over sales), the ratio oflong-term debt to total assets, com-pany size, and the fraction of com-mon stock held by the CEO or hisimmediate family.

Table 3 presents coefficient esti-mates for the CEO turnover model.And the results are as hypothesized:The coefficient on the mutual inter-lock variable is negative and signifi-

12 Sternbusiness

TIES THAT BIND

TABLE 2: EFFECT OF INTERLOCKS ON CEO COMPENSATION

Estimate

4.956

0.010

0.288

0.019

-0.012

0.428

-3.000

0.170

Variable

INTERCEPT

Director interlocks

Natural log of total assets

CEO tenure as CEO

CEO tenure in firm

1991 stock return

Stock ownership by CEOor family

Tobin’s Q

Std. Error

0.304

0.005

0.038

0.005

0.003

0.107

0.641

0.047

p-value

0.0001

0.0371

0.0001

0.0001

0.0001

0.0001

0.0001

0.003

cant as predicted, implying that thepresence of mutual board interlocksis inversely associated with the prob-ability of CEO turnover. We inter-pret this result to indicate thatmutually interlocking directorshipsweaken the monitoring power thatthe board has over the chief execu-tive. Further, mutual interlocks con-tribute to the possible entrenchmentobjectives of the CEO. This result isin agreement with the notion thatboards are ineffective in controllingthe CEO, who is likely to control thenomination and selection process ofthe directors.

These results are consistent withother theories and research on CEOturnover. As previous studies havenoted, we found that CEOs are less

likely to leave officeif they own a largefraction of equity inthe firm or if com-pany performance is

strong. And we found that age ispositively associated with the proba-bility of CEO turnover. Firm size, asproxied by the natural log of thefirm assets, does not appear to playa role in the likelihood that the CEOleaves office.

ConclusionAcademics and the popular press

have suggested that corporateboards are ineffective in monitoringCEOs, since CEOs frequently domi-nate the director selection process.Boards filled with CEO-sympatheticdirector appointees are likely toovercompensate and undermonitorthe chief executive. Our view is thatthe mutually interlocking director-

ships that are prevalent among firmsare responsible for the production ofsympathetic directors. These direc-tors have the opportunity to pay andre-pay each other favors because oftheir multiple board membershipsand may well be doing so in leaguewith the CEOs who nominatedthem.

Our results indicate that thepower alliances created by directorswith multiple memberships are usedby self-serving CEOs to extracthandsome remuneration packagesfrom firms and to strengthen theirentrenchment. Boards that overcom-pensate and undermonitor the CEOare not fulfilling their fiduciaryduties to the shareholders. As aresult, board mutual interlocksweaken the firm’s governance struc-ture, promote cronyism, and exacer-bate the firm’s agency problems.

The results reported here indicatethat it is at least plausible thatmutual director interlocking rela-tionships between different corpo-rate boards might affect the votingpatterns and decisions that theseboards make on other mattersbesides CEO compensation andturnover.

Overall, our research suggeststhat inter-board relationshipsshould be more closely scrutinized todetermine whether these relation-ships encourage decisions thatenhance shareholder wealth orinstead facilitate empire building byself-serving CEOs. If, as we suspect,the latter is the case, then closermonitoring – private and/or public –of boards is needed.

ELIEZER M. FICH, Stern Ph.D. 2000, isvisiting assistant professor of finance atthe Kenan-Flager Business School at theUniversity of North Carolina.LAWRENCE J . WHITE is Arthur E.Imperatore professor of economics atNYU Stern.

This article is adapted from an articlethat appeared in the Fall 2003 WakeForest Law Review.

Sternbusiness 13

TABLE 3: PROBIT COEFFICIENT ESTIMATES: CEO TURNOVER

Estimate

-6.83

-0.98

0.72

0.09

0.01

-0.60

-0.30

3.35

0.04

-47.49

0.01

0.39

1.52

0.06

VariableEstimate

INTERCEPT

Mutual directorinterlock indicator

% of board directors whoare CEOs of other firms

CEO’s age (in years)

Option compensation/(salary + bonus)

Stock return net-of-market

Stock return net-of-market(lagged one year)

R&D expense/sales

Firm size (natural logof total assets)

% of equity held by CEOthrough direct stock ownership

Tenure as CEO (years)

Leverage (long termdebt/total assets)

Return on assets (ROA)

CEO is member of foundingfamily

Std. Error

1.531

0.512

0.891

0.024

0.054

0.364

0.351

2.374

0.102

26.806

0.016

0.705

1.788

0.498

p-value

0.0001

0.0548

0.4191

0.0001

0.8344

0.1000

0.3937

0.1587

0.6819

0.0764

0.3516

0.5824

0.3951

0.8972

“Interlocking directorships weakenthe monitoring power that the board

has over the chief executive.”

14 Sternbusiness

Entrepreneurs operat ing in America’s emerging markets — once-abandoned central c i t ies —

early 40 years after thepassage of the CivilRights Act, residentialand commercial segre-gation remain a fact of

life in America. Due to prevailinginstitutional, residential andsocial segregation, demographicgroups that are generally in theminority – African-Americans,Asian-Americans, Hispanics andimmigrants – predominate withinurban central cities. And yet inmany of those same areas, a major-ity of business owners are white.

White entrepreneurs in centralcities face the novel experience ofworking in a social context in whichthey are racial minorities, while atthe same time they are a part of thedominant coalition of firm ownersand are members of the majoritywithin the larger society.

Entrepreneurs in urban contextsfind that they must build relation-ships across racial and ethnic bound-aries. But “tokens” – numerical

sonally, they may also establish rela-tionships with other institutions orindividuals – “social brokers” – thatcan provide links to immigrant andethnic groups. Government agencies,non-profit and service organizations,religious institutions, and even cur-rent customers or employees canserve as social brokers, yet not beexplicitly dedicated to this practice.We set out to determine the role andsignificance of social brokers in help-ing white entrepreneurs in central-city locations forge cross-racial andcross-ethnic links with employeesand customers.

Then and NowIn his classic 1973 study of dis-

crimination in hiring, sociologistHoward Aldrich examined patternsof firm ownership in the pre-dominantly black neighborhoodsof Roxbury (Boston), Fillmore(Chicago) and Northern Washington,DC. The majority of the employers(55 percent) in these areas were

N

Sternbusiness 15

ILLU

STR

ATIO

NS

BY

TIM

OTH

Y C

OO

K

By Gregory B. Fairchild and Jeffrey A. Robinson

f ind that socia l brokers can bridge ethnic and racia l gaps. They can a lso help bui ld prof i ts .

minorities in organizations or con-texts dominated by the majority –face considerable challenges in doingso. That’s because cross-race rela-tionships, within and outside oforganizations, remain relativelyunusual. In his 1987 study of corediscussion networks, Harvard soci-ologist Peter Marsden found thatonly eight percent of Americansreported any racial or ethnic diversi-ty in their networks, with whiteAmericans having the greatesthomogeneity.

In the inner-city context, then,those with the least experience inforging cross-racial relationshipshave the greatest need to do so.White entrepreneurs in central citiesusually cannot leverage their per-sonal knowledge of co-ethnic cus-tomer tastes and appeal to boundedsolidarity to build protected mar-kets.

While these firm owners maychoose to focus on building cross-race, central city relationships per-

GOING FORBROKERS

white, and whites were minorities inthe residential population (rangingfrom 10 percent of the population inFillmore to 28 percent in Roxbury).Aldrich also found that 80 percentof the white firm owners were“absentee owners.” White firm own-ers were more likely to hire peoplewho lived outside of the neighbor-hood and were more likely to hirewhite employees than non-whitecentral city firm owners. Other stud-ies at the time found similar owner-ship patterns in other cities.

Do these conditions still persist?In 1970, when Aldrich’s data wascollected, each of the neighborhoodsstudied had only a decade earlierbeen predominantly white. Aldrichtied the pattern of white firm owner-ship to an inability of white firmowners to leave as rapidly as whiteresidents.

But the “white flight” context ofthe early 1970’s no longer exists incentral cities. White residents havelong been gone from these neighbor-hoods, and the absolute number ofbusinesses has declined significantly.So today’s central city firm ownersare more likely to be located thereby choice. A second difference is theconsiderable influx of non-whiteimmigrants from Asia, CentralAmerica and the Caribbean.Previous studies have shown thesegroups to have high incidence ofentrepreneurship.

To update Aldrich’s study, weanalyzed a subsection of employerrespondents from the Multi-CityStudy of Urban Inequality (MCSUI).This data was collected by

researchers in Atlanta, Boston,Detroit and Los Angeles between1992 and 1995 to examine labormarket dynamics, with a particularfocus on jobs requiring no more thana high school education. Table 1presents the incidence of white firmownership by metropolitan areasubsection, based on 510 respon-dents.

As found in studies from the1970s, the dominant coalition offirm owners are white (84.9 per-cent), and seven of every 10 firmowners in predominantly non-whitecentral city areas are white. The per-centage of white firm ownership incentral city areas is even greaterthan in studies from the early1970’s. Why? It has long beenargued that whites have greateraccess to critical capital stocks,making them better able to startfirms and to weather economichardships than their black andHispanic counterparts. Second,black central city neighborhoodshave been especially hard hit by theexit of the middle class, who hadoptions to move after segregationdeclined in the 1970’s.

We then analyzed responses offirm owners regarding the incidenceof white customers and employeesby city subsection. In central cityareas, where the majority of the res-idents are non-white, the white/non-white composition of the customerbase and employee base is evenlysplit (50.1 and 47.5 percent, respec-tively). However, there is consider-able variation across firms in termsof their customer and employee

demography. The standard devia-tion was 35.1 percent for white cus-tomers, and 40.5 percent for whiteemployees.

Hiring PatternsNext, we set out to determine the

influence of owner race on racialcomposition of the employmentbase. Because Aldrich found thatdifferences in firm type (e.g., retail,service or manufacturing) account-ed for some of the differences in hir-ing patterns, we controlled for sectorof employment in our analysis.

In line with the findings of stud-ies from a generation ago, we foundthat the race of the firm owner influ-ences hiring patterns, even whenadjusted for firm location andindustrial sector. White firm owner-ship increased the percentage ofwhite employees by an average of 40percent.

Aldrich generated four hypothe-ses regarding the possible role of dis-crimination in hiring patterns. First,white employers may simply preferassociating with whites over blacks.Second, white employers mightpractice statistical discrimination, inwhich negative beliefs about thework fitness of blacks cause employ-ers to prefer not to hire blackemployees. Third, white employersmight avoid hiring blacks because ofnegative reactions of other employ-ees or the firm’s customers. Fourth,white employees might be over-rep-resented because whites who workedin the firms prior to the wholesalewhite exodus from the neighborhoodhung on to their jobs in these neigh-borhoods. Aldrich was ultimatelyunable to determine whether dis-crimination accounted for the over-representation of white employees inwhite-owned firms located in blackneighborhoods.

Today, two of these hypothesesare less useful. The customers offirms in today’s central city areas are

16 Sternbusiness

GOING FOR BROKERS

Table 1: PERCENTAGE OF WHITE OWNERS BY FIRM LOCATION IN CITY SUBSECTION

All locations Central City Suburban Univariate F-locations and Other Statistic

locations

Mean % white owners 84.9 68.8 89.8 31.23**

** statistically significant at the .001 level

as likely to be white as non-white.And because white flight is nolonger a recent phenomenon – as itwas in the 1970s – there is a lowpotential that the current set ofwhite employees were unable to findwork elsewhere. The second hypoth-esis, that white employers havedeveloped a “distaste” for non-whitelabor, has been examined by otherresearchers. In interviews with whiteemployers in central city areas,employers expressed their tendencyto practice statistical discriminationwith black applicants because ofpast experiences with negativeworkplace attitudes and behaviors.Sociologist William Julius Wilson in1996 examined blackemployers from thesame neighborhood,and found that theyexpressed similarviews of the attitudesand work ethic ofcentral city blackemployees.

But employer distaste probablydoesn’t explain the differences inhiring patterns by race of ownerobserved above. Perhaps whiteemployers, like other tokens, facebarriers in establishing cross-racerelationships that might assist themin locating the most qualifiedemployees from the local pool oflabor. Given the generally low opin-ion employers appear to have ofcentral city labor, reference-basedhiring may be one of the primemeans of ensuring labor quality.

Weak TiesIn his classic 1973 study of per-

sonal contacts in job-seeking, sociol-ogist Mark Granovetter found thatthe overwhelming majority (83 per-cent) of managerial and professionaljob seekers found their jobs throughacquaintances with whom theyspoke occasionally or rarely. Thisfinding of the “strength of weak

ties” is one of the more influentialideas in the social sciences.

But Granovetter’s reanalysis ofStanley Milgram’s data on interra-cial acquaintance chains has beenless discussed. Granovetter reana-lyzed the success rate of whitesenders who attempted to deliver abooklet to black targets throughacquaintance chains, if the first con-nection between a white sender anda black recipient described the blackperson as a “friend” or an “acquain-tance.” Granovetter found that theweak tie instances – those where thefirst black connection was describedas an acquaintance – were twice aslikely to result in a successful com-

pletion to the eventual target. Weakacquaintance ties were more suc-cessful than strong friendship ties inreaching cross-race targets.

Given this, we hypothesize thatcross-race weak ties might alsoassist in the recruitment of employ-ees. And institutions or individualsthat bridge socially segregatedgroups are a form of weak tie rela-tionship that employers can use tomediate their token status.Connections through communityservice organizations, religious insti-tutions, civic leaders, and currentemployees might assist employers inlocating qualified minority employ-ees and result in larger numbers ofminority employees.

Using Social BrokersHiring proper employees is a crit-

ically important task for a firmowner. But when the employer iswhite and the employees are gener-

ally non-white, the hiring challengemay be especially difficult. A racial“outsider” may find it tough toaccurately screen an applicant dur-ing the hiring process and revealpotential behavioral or attitudinalmis-hires. Once employees arehired, white employers may worrythat negative on-the-job feedbackwill result in accusations of racialprejudice. Given the distrust, doubtand accusations that can sometimesaccompany cross-race interactionsin central cities, some entrepreneursmay choose to avoid central citylocations or minority employeesaltogether.

The MCSUI contained a series ofquestions regard-ing the methodsused by employersin hiring for theirlast employmentvacancy. The posi-tions were thosetha t d id no trequire the appli-

cant to hold a college degree. Weinvestigated the influence of hiringmethods that involved social brokerson minority hiring rates in centralcities. Table 2 presents the results ofthree linear regression analysesusing dummy variables to determinethe influence of the race of owner,city subsector, industry sector andhiring methods on the percentage ofnon-white employees in the firm.

The analysis of the full set offirms shows that manufacturingfirms are more likely to hire non-white employees. This is likely dueto the greater need for unskilledlabor in these firms. The first evi-dence of social brokerage is found inthe strong influence of employeerecommendations on the percentageof non-white employees. Both themagnitude of this coefficient and itshigh level of significance is persua-sive evidence of the use of this prac-tice among entrepreneurs. The use

Sternbusiness 17

“Given the distrust, doubt and accusations that can sometimes accompany cross-race

interactions in central cities, some entrepreneurs may choose to avoid central city

locations or minority employees altogether.”

of help wanted signs was also shownto increase the percentage of non-white employees. Help wanted signsare a strategy for employers seekingto attract employees that happen topass the firm location, and may be ameans to hire from the local com-munity without aid of brokerage.

Private-service temporary agen-cies appear to serve as brokers forfirms seeking to hire white employ-ees, while community agencies servefirms seeking non-white employees.These differences are likely generat-ed by the divergent customer needsthat each agency serves.

Even after controlling for citysubsection, industry and hiringmethod, the strongest influence onpercentage of non-white employeesis still the race of firm owner. Thissuggests that our analysis has failedto account for other factors influenc-ing the hiring choices of white own-ers, and that these results do notrule out preferences for homophily.

Help WantedSplitting the files by city subsec-

tion allowed us to compare the inci-dence of brokerage strategies byfirm location. We found that outsidecentral city areas, manufacturingfirms have a greater tendency to hirenon-white employees, and helpwanted signs increase the percent-age of non-white employees. Analternative perspective is thatemployers located in suburban areasare familiar with available locallabor (predominantly white), anduse help wanted signs as an “affir-mative action” strategy, designed toattract potential employees that arenot in their current social network.

Employers may find that non-white applicants that learn of theiropenings by passing their locationare more likely to be “acculturated”or familiar with the workplacebehaviors necessary to work in sub-urban contexts. The positive findingfor all firms appears to be driven by

the use of this brokerage strategy incentral cities. Outside of centralcities, employers utilize currentemployees as brokers for non-whiteemployees, though to a lesserdegree. Private-service temporaryagencies play a strong role in bring-ing white employees into firms.Finally, referrals from educationalinstitutions enhance non-white hir-ing outside central cities. It appearsthat for firm owners in these areas,educational institutions play a bro-kerage role in assisting in the hire ofnon-white employees.

Customer RelationsEntrepreneurs must also manage

another critical constituent groupon the demand-side of the equation:customers. Customers are not only afirm’s source of revenue, they are aprime means of attracting new cus-tomers through word-of-mouth. Butfor white entrepreneurs operating incentral city areas, building relation-ships with customers from the localcommunity may present many ofthe same challenges found in locat-ing employees. White firm ownersare less likely to be personallyfamiliar with community membersand are less likely to be personallyaware of emerging customer tastesand needs. Non-white customersmay resent the presence of whitefirm owners, and customer dissatis-factions may take on an accusatorytone generally not experienced incontexts where the customers arepredominantly white. There is a his-torical legacy of mistreatment ofminority customers in businessesowned by white proprietors. Whitecentral city entrepreneurs maytherefore attempt to use employeesas brokers to manage potentiallyfractious relations with a substan-tial base of non-white customers.

We set out to determine the influ-ence of customer demography on themakeup of a firm’s labor pool. Ifincreasing percentages of non-white

18 Sternbusiness

GOING FOR BROKERS

Table 2: MODEL RESULTS

Dependent Variable: mean % nonwhite employeesFull Sample Central City Suburbs

& Other(n=474) (n=164) (n=310)

Adj. R2 .250 .205 .224Std. Error of estimate .3286 .3496 .3169F 10.990 3.961 7.039Independent Variables:Constant .519 *** .638 *** .543 ***Central city location .093 **White firm owner -.435 *** -.380 *** -.490 ***Manufacturing firm a .082 * -.006 .124 *Service firm -.060 -.091 .045Used help wanted signs .082 + .019 .120 *Used newspaper ads -.031 -.127 * .023Accepted walk-in applicants .008 .016 .014Used employee referrals .152 *** .162 * .126 **Used state employment agencies .007 .067 -.024Used private-service temp agencies -.115 * -.096 -.135 *Used community agency referrals .115 * .162 + .046Used union referrals .109 .009 .023Used school referrals .021 .003 .370 *a dummy variables for manufacturing and service firms, retail firms are the base

+ p<.10 * p<.05 ** p<.01 *** p<.001

customers positively influences thepercentage of non-white employees,it would suggest that employers useemployees as social brokers to man-age relationships with customers. Toinvestigate, we ran a linear regres-sion analysis of race of firm owner,industry sector, firm location, andpercentage of non-white customerson the mean percentage of non-white employees.

The results of this analysis areconsistent with the hypothesis thatcustomer demography explainssome of the variance in employeedemography even after controllingfor race of firm owner. Subsequentanalyses of these influences by firmlocation showed the same pattern ofresults throughout. However, themagnitude changes of coefficientsprovided some interesting findings.First, when compared with the prioranalysis of employer race influenceon employee demography, the coef-ficient for white firm ownersdecreased when the predictor vari-able for customer demography wasentered. Some of the varianceexplained by employer race in theearlier analysis is now shown toresult from customer demography.Second, white customers have a pos-itive influence on the number ofwhite employees in all locations,although the relationship becamestronger in suburban areas. Third,white firm owners have an evengreater positive influence on the per-centage of white employees in cen-tral city areas. This suggests one oftwo alternative hypotheses: a) whitefirm owners in central city locationshave an even greater preference forwhite employees than in suburbanareas; b) white firm owners faceeven greater challenges in locatingnon-white labor in central cityareas. Given our theoretical framingof white firm owners as tokens wesuspect the latter.

Emerging MarketsTaken together, our findings sug-

gest that relationships play a criticalrole in job seeking, especially whenoperating cross-racially. And under-standing this dynamic is becomingmore important. For over the pastseveral decades, patterns of socialand racial segregation have createdstructural holes, which in turn havecreated economic opportunities incentral cities – America’s emergingdomestic markets.

Entrepreneurs of all races andethnicities are figuring out how tobuild wealth while providing jobsand leadership that diminish manyof the social problems we’ve come toassociate with inner city communi-ties. In May 2003, Inc. magazinereleased its annual list of the mostrapidly growing inner-city firms.The characteristics of the membersof the Inner City 100 may seem sur-prising: average sales of over $25million, and five-year growth ratesover 600 percent.

Social brokers will play animportant role in developing thesemarkets further. America’s inner-city neighborhoods will increas-ingly show promise as sites forinvestment, and many of theentrepreneurs pursuing theseopportunities will not be ethnicand racial minorities. On Inc.’slist, 62 percent of the firm ownerswere white. Locating high qualityemployees in a cross race situationrequires the recognition that rela-tionships matter and that relation-ships tend to stay within the samerace. Without building social bro-kerage relationships, employers runthe risk of missing the most quali-fied members of the labor pool.

GREGORY B. FAIRCHILD is assistantprofessor of management at DardenGraduate School of BusinessAdministration at the University ofVirginiaJEFFREY A. ROBINSON is assistantprofessor of management at NYU Stern.

Sternbusiness 19

20 Sternbusiness

On October 8, it was announced that Robert Engle, Michael Armellino

Professor of Finance at NYU Stern, was awarded the Nobel Prize in

Economics along with Clive Granger, his longtime colleague at the

University of California at San Diego. Engle, 60, a Stern professor since

2000 and a pioneer in the field of econometrics, was cited for the develop-

ment of Autoregressive Conditional Heteroskedasticity (ARCH), a method

that allows researchers and analysts to measure volatil ity over time. On

November 4, Stern faculty, staff, and students, led by Dean Thomas Cooley

and William Greene, former chairman of the department of economics,

gathered at the Henry Kaufman Management Center for a town hall meet-

ing to honor Professor Engle and discuss his work.

Sternbusiness 21

Dean Thomas Cooley: It's a good thing when good things

happen to deserving people, and when your friends and col-

leagues get recognized for their accomplishments. We are just

overjoyed at the great news that we all got this fall.

Bill Greene: I'm going to throw Rob some easy questions and

then I'll turn this over to the audience to follow up. So let me begin

with the easiest ones of all. Can you tell us a bit about yourself and

where you come from?

Robert Engle: I grew up in

Philadelphia. And I was an East Coaster

for many, many years. My Ph.D. is from

Cornell, where I went to study physics

and then changed my mind. I actually

taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology when Tom

[Cooley] and I knew each other. And then in the mid-1970s, I went

to the University of California at San Diego, and spent 25 years

there. I came back east to Stern in 2000.

Greene: Why economics and not physics?

Engle: Well, when I got to graduate school, I joined the laborato-

ry studying superconductivity. It was in the basement of the

physics building, and the only people you ever saw were a few

other graduate students. I just decided I wanted to do something

that had a little wider relevance. And I wanted to switch into a field

that used some of the same ways of thinking that physics does.

That's one of the reasons I switched to economics – and particu-

larly why I became an econometrician. The best physics, of

course, has both empirical work and theory. And I think econo-

metrics provides exactly that intersection for economics.

Greene: So where were you when you got the call?

Engle: Well, you probably noticed that I haven't been here this

fall. That's because I’ve been on sabbatical in France, in a town

called Annecy in the French Alps. I had just been out to lunch with

my wife, when I went out to do an errand and she came back to

the apartment and got the phone call. The woman on the other end

said, "Tell him that this is a very important call from Stockholm."

And when the phone call came in again, the connection was not

clear. The head of the Nobel committee has a relatively thick

Swedish accent. Eventually I came up with the inference that yes,

it was indeed that I had won the Nobel Prize. And I won it with my

long-time colleague, Clive Granger from San Diego.

The head of the committee said, "Your life will not be the same

again; the press will be all over you." So when we hung up, we

looked at each other. And here we are in this little medieval town

in France. First of all, how did anybody ever find that phone num-

ber? But second of all, is the press really going to find us? Some

of the press found us, but not too much. But mostly it was phones

ringing in our home, in my office, and a lot of e-mails. I must have

received hundreds of e-mails that day.

Greene: The New York Times had an article a few days ago, in

which they described econometrics as a

rarefied field. But seven Nobel Prizes

have been given to econometrics. Why

do you think they have such an interest

in this field?

Engle: Econometrics is the tool. And in

some ways, at its best, it is really what economics is about. I think

it is a way of trying to make sense out of the world around us. The

world around us is the data. And an econometrician is a person

that looks at the data.

Greene: Well, let's turn to your work. What is the contribution that

you made that got the prize committee's attention?

Engle: The prize citation says it is for “models of time varying

volatility, parentheses ARCH.” Now they didn't tell you what ARCH

stands for. I will, but only if you promise not to be put off by what

it really stands for. It stands for Autoregressive Conditional

Heteroskedasticity. If you take my class, I'll teach you how to say

that, but other than that, it's just ARCH. It’s a way of trying to

model, describe and forecast this thing we call volatility. In finan-

cial markets, we're so interested in the volatility of asset prices.

Because when stock prices wiggle around, your portfolio can go

up or down. And volatility is an important consideration as to what