State TANF Spending

-

Upload

thalia-sanders -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of State TANF Spending

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

1/16

745

State TANF Spending: Predictors of State Tax Effort toSupport Welfare Reform

Harrell R. Rodgers, Jr. and Kent L. TedinUniversity of Houston

Abstract

State spending on Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) greatly varies. Combined federaland state spending by the states per TANF family or recipient reflects the historic level of state generos-ity for Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), the failure of the federal government to setany minimum spending standard for the states, and the failure of the federal government to adjustfederal grants for huge changes in state TANF caseloads. Our multivariate analysis shows that statespending for TANF is greatly influenced by the percentage of the state population that is black, the per-centage of the state population that is on TANF (especially if a significant percentage of the rolls consistof black recipients), and the economic conditions within the state. Some states spend as much as theireconomies will allow, while other states spend far below capacity. Despite the very different goals of

TANF, state spending is still heavily influenced by their historic approach to AFDC.

In 1996 Congress created a new welfare system by passing the Personal Responsi-bility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA). One provision of thisact repealed Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) and replaced it withthe Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. Under TANF states

receive block grants based on their combined federal and state expenditures forAFDC and related programs in either fiscal year 1994, or the average of fiscal years

19921994, whichever was higher. States are required to continue to financiallycontribute to the overall cost of TANF by spending at least 75% as much as theywere spending for AFDC and related programs. Figure 1 shows actual expendi-tures under AFDC and TANF from 1990 to 2002. Spending peaked at $30.1 billion

in 1995, and then tapered off over the next several years. In fiscal year 2002 com-bined state and federal expenditures for TANF programs was $25.4 billion. Thestate share of total expenditures between 1990 and 2002 averaged about 45%.

In recognition that the poverty problems, economic viability, and demograph-ics of states significantly vary, TANF allows the states to exercise considerablediscretion in designing their welfare programs. Two major differences among the

states are in the size of their poverty populations and the percentage of their popu-lations that is poor. In 2003, for example, the number of poor by state ranged from4.3 million in California to 42,000 in Wyoming. Similarly, the poverty rate ranged

from a low of 5.8% in New Hampshire to a high of 18.1% in New Mexico. Thepercent of state populations receiving TANF varied from a miniscule 0.17% inWyoming to 7.38% in the District of Columbia. Clearly the poverty problems the

states are dealing with differ by a wide margin.The budget that each state has to fund TANF more accurately reflects the states

historic expenditures on their poor than the size and needs of their contemporary

poverty populations. States have never been required to meet any minimumexpenditure standards. State generosity varied a great deal under AFDC and thosepatterns persist under TANF. As noted, the federal grant a state receives for TANF

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

2/16

746 Harrell R. Rodgers, Jr. and Kent L. Tedin

Figure

1.

FederalandStateExpendituresforT

ANFandPredecessorPrograms,FiscalYears19902002

Source:

HouseCommitteeonWaysandMeans,GreenBook,Table759,Government

PrintingOffice,2004.

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

3/16

states with a more generous spending history under AFDC receive higher fundingfor TANF than states with a history of low spending. States with high poverty ratesand unemployment above the national average qualify for supplemental grants,

but since most of these states are low spenders they remain below the nationalaverage in per capita TANF funding per poor person (Green Book, 2004, Table 7-

2).In recent years spending patterns have become even more disconnected from

need because the historic base of funding has not been altered in response to recentmajor changes in state TANF caseloads. In 1993 and 1994 5.5% of the national

population was receiving AFDC. The passage of reform in 1996 was the beginningof significant declines in the welfare rolls. By 2000 the rolls had shrunk to 2.1% ofthe national population. Declines continued and by 2002 had shrunk to 1.8% of

the national population (DHHS, 2004; Blank, 2001). While welfare rolls havedeclined in all the states and territories, the rate has been very different. Figure 2

shows the drop between 1996 and 2001 in welfare rolls for each of the states andthe District of Columbia. Two states, Wyoming and Idaho, saw declines of over 90%.Another six states have had declines of over 70%. In 33 states the rolls dropped byhalf or more.

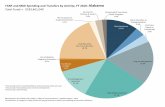

The failure to adjust federal grants for declines in caseloads, compounded bythe historical base of federal funding, has resulted in a very wide variation in theamount of dollars states have available to spend on each of their TANF recipients.

Figure 3 shows the per capita federal/state TANF expenditures per recipient bystate in 2002. These data were calculated by dividing all 2002 TANF spending ineach state by the total number of TANF recipients in the state. The result is a per

capita expenditure per TANF recipient, but this does not mean that each recipi-ent received this amount. The majority of the money in most states is spent onsupport programs for poor and low-income populations that may be above the

poverty line, not on cash grants (DHHS, 2004, II, Figure A). The data in Figure3 show that 9 states spent less than $3,000 a year per TANF recipient (less than$250 a month), while 13 states spent more than $6,000 (at least $500 a month). At

the extreme, Wisconsin spent $10,820 per recipient, while Idaho and Wyomingwith their tiny TANF populations spent $16,583 and $26,604, respectively.

Much of the variation in TANF spending reflects state spending of their funds

for TANF. Figure 4 shows state per capita spending per TANF recipient in 2002.

At the low end 21 states spent less than $1,500 a year per TANF recipient. At thehigh end, nine states spent in excess of $3,000, with Wisconsin, New York, Idaho,

and Wyoming being particularly high spenders.Figure 5 shows that the states also vary greatly in the percentage of combined

federal/state TANF costs they fund. Again, the difference among the states is dra-

matic. While California pays 53% of total costs, Mississippi pays only 15%. Twenty-two states pay over 40% of all costs, while 11 states pay less than 30%.

Explaining State Spending Differences

The analysis above shows that the differences in state TANF expenditures signifi-

cantly reflect a federal grant formula based on historic spending in each state,

State TANF Spending 747

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

4/16

748 Harrell R. Rodgers, Jr. and Kent L. Tedin

re

2.Fis

calNeed:PercentageofStatePopulationonTANF:2002

ce:DHH

S.2004TANFAnnualReporttoCongress,Table1:10B.GovernmentPrintingOffice.Washington,D.C.

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

5/16

State TANF Spending 749

re

3.Co

mbinedState&FederalPerCapitaTAN

FPerRecipient2002*

rce:DHHS.2004TANFAnnualReporttoCong

ress,Table2-1.GovernmentPrintingO

ffice.Washington,D.C.

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

6/16

750 Harrell R. Rodgers, Jr. and Kent L. Tedin

re

4.

Sta

tePerCapitaTANFperRecipient:2002*

alstateT

ANFspendingdividedbynumberofre

cipients.

ce:DHH

S.2004TANFAnnualReporttoCongress,Table28.GovernmentPrintingOffice.Washington,D.C.

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

7/16

State TANF Spending 751

re

5.

Sta

tePercentageofTotalFederal/StateTANFSpending:2002

ce:Gree

nBook.2004.HouseCommitteeonWaysandMeans.Table7-19,Table7-65-66.GovernmentPrintingOffice.Washing

ton,D.C.

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

8/16

government, and the fact that since reform federal grants have not been adjustedfor differences in changes in state TANF caseloads. The part of the equation thatwe focus on here is state support of TANF. The specific question is how can the

considerable differences in state funding of TANF be explained? The dependentvariable is a measure of how much tax effort each state puts forward to support

the TANF program. The most widely accepted approach to measuring tax efforton behalf of specific public policies is to compute the ratio of per capita spendingon the policy (in this instance on TANF) to per capita personal income (Alexander,1997; Halstead, 1994). Personal income is an approximate indicator of the ability

of state residents to pay for TANF. This ratio, based on 2002 data, is then stan-dardized so that 100 is the national base. Numbers below 100 mean the state TANFeffort, based on the per capita income of its citizens, is below the national norm.

We see from Figure 6 that the states making the least TANF effort tend to be inthe South and those making the greatest effort tend to be in the Midwest and East.

We begin by examining seven hypotheses regarding the tax effort made bystates to fund TANF. With just 50 cases, we shall usep < 0.10 to test our hypothe-ses. As indicated earlier, our dependent variable is the ratio of state per capitaincome to state per capita TANF spending, normed so the national average equals

100. We shall sometimes use the shorthand TTE to refer to this ratio (TANF taxeffort).

Our first hypothesis is that the wealthier and more economically viable a state,

the greater will be the TANF tax effort. Past research suggests that states andnations with greater financial resources spend more on welfare (Fritzell &Ritakallio, 2004; Rodgers, 2005; Smeeding, 2004, 2005). We suggest that state

wealth also translates into a willingness among the wealthier states to make agreater tax effort to fund TANF. Although we have several indicators of state eco-nomics, conceptually the most attractive indicator is total taxable resources per

capita (Office of Economic Policy, 2003; Tannenwald, 1999). This is an indicator ofthe wealth of a state, and the resources available for taxation. Consistent with thehypothesis, it has a product-moment correlation of 0.29 (p < 0.05) with TTE.

Perhaps the flip slide of state wealth is state unemploymentalthough statewealth is more or less constant through time, unemployment can vary significantlyover short periods of time and in different parts of the country. We coded the

unemployment rate for 1997 and for 2003. We use the change in the rate of unem-

ployment as our second independent variable. Our hypothesis is that states withgreater increases in unemployment will make a lower tax effort to support TANF.

The direction of the coefficient supports the hypothesis, but the bivariate correla-tion is a modest 0.13, failing to meet our standard for statistical significance.

Another important issue identified in the literature is race. Numerous studies

have found that states spend less on welfare if a significant percentage of their pop-ulation is black, and when a larger percentage of welfare users in the state areminorities (Brown, 1999; Fording, 2003, p. 74; Gilens, 1999; Handler, 1995; Hero,

1998; Howard, 1999; Noble, 1997; Orr, 1976; Plotnick & Winters, 1985). We havedata on the percentage of each states population that is black, the percentage ofall TANF users in each state that are black, and the percentage of state legislators

that are black. These variables are intercorrelated at 0.90 or greater, suggesting

752 Harrell R. Rodgers, Jr. and Kent L. Tedin

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

9/16

State TANF Spending 753

re

6.Sta

teFANFSpendingEffort:2002*

epercapitaTANFdividedbypercapitaperson

alincome.IndexedtoU.S.

ce:DHH

S.2004TANFAnnualReporttoCong

ress.GovernmentPrintingOffice.Wash

ington,D.C.

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

10/16

indicator of race. Our hypothesis is that the larger the black population, the lowerthe tax effort made by a state to support TANF. Race correlates with TANF taxeffort at 0.21, supporting our hypothesis, but falling short of the level we set for

statistical significance.Given the results for the black population, we expect a similar relationship for

the Hispanic populationat least if the coefficient above has its foundation in ratio-nal economics. That is, states with large minority populations have larger propor-tions of their populations eligible for TANF. However, the hypothesis is notsupported. The relationship between percent Hispanic population and TTE is

0.00. Of course, there are many possible reasons why percent black and percentHispanics have different effects on TANF tax effort. States currently with large

black populations have had them for a long time, and poor TANF tax effort may

be based on history. Hispanics, of course, are a more recent minority.A third possible dimension is state ideology (Berry, Ringquist, Fording, &

Hanson, 1998). A number of studies of state policy outputs have found this itemto be predictive (Berry & Berry, 1990; Erikson, McKuen, & Stimson, 2002; Fording,1997; Plotnick & Winters, 1985; Rom, 1999; Soss, Schram, Vartanian, & OBrien,2001; Stimson, MacKuen, & Erikson, 1995). Our hypothesis is the greater the per-

centage of liberals in the population, the greater TANF tax effort a state will make.The logic is straightforward. A more liberal electorate is more likely to chooseliberal representatives who would be inclined to make a greater tax effort to fund

TANF. Despite a good deal of evidence that state citizen ideology matters, thehypothesis is not supported in this case. The relationship between the percentliberal in the population and the TANF tax effort is only 0.02. 1

Additionally, each state was coded on the percentage of the population identi-fying themselves as Democrats (Voter News Service Exit Poll, 2004). Our hypoth-esis is that those states with the highest percentage of Democrats in the population

will make a greater tax effort to support TANF. However, the relationship is exactlythe opposite of that hypothesized. In fact, states with the highest percentage ofRepublicans in the electorate that score highest on TTE. The coefficient for percent

Democratic is 0.27 (p < 0.10), while for percent Republicans is 0.17 (n.s.). Thereason is that there is a high correlation between the percent black in a states elec-torate and the percent Democrat (r = 0.64). Thus we have conflicting theoretical

explanations, but it appears that the percent black in the electorate overrides the

percent Democratic to the point we are left with the counterintuitive finding thatstates with a higher percentage of Republicans are likely to make the greatest tax

effort to support TANF.Our fourth set of variables is TANF policies adopted by some of the states that

are considered to be tough policy options (Soss et al., 2001). These are policies

adopted by some of the states that: (a) require recipients to go to work after lessthan 24 months on the rolls, (b) set the lifetime limit for federal assistance at lessthan 60 months, (c) impose very strong sanctions on uncooperative clients, and (d)

deny added assistance to women who have additional children while on welfare.We used factor analysis to determine if these four variables would load on a singledimension. The requirement that recipients go to work after less than 24 months

did not load cleanly with the other three items, and so our factor score scale will

754 Harrell R. Rodgers, Jr. and Kent L. Tedin

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

11/16

(labeled tough) was created for each of the states. Our hypothesis is that thosestates with the toughest welfare policies would be those with the lowest TANFexpenditures. The simple correlation is 0.23, opposite our hypothesis. The coeffi-

cient does not quite meet the level we set for statistical significance (p < 0.11), butthe coefficient is not trivial. It means the states that have the tough TANF poli-

cies also are often willing to make the greatest tax effort to support TANF. In oneway, the relationship makes sense, as those states making the largest tax effort tosupport TANF may have the most carefully crafted, goal-oriented programs. Aninteresting elaboration on the tough score variable is found when controlling for

percent black in the population. This control substantially increases the effect ofthe tough policies with beta increasing from 0.22 to 0.34 (p < 0.05). Our inter-pretation is that percent black works as a suppressor variable, reducing the posi-

tive effect of tough policies on TANF tax effort. Were it not for the unevendistribution of blacks in the population, tough policies would significantly

increase the TTE. On the other hand, the significant coefficient under controlledconditions indicates theoretically that tough policies make a difference.Last, we examine the impact of caseload density on the generosity of a state in

taxing itself to fund TANF. States where a large proportion of the population is on

welfare will likely be less generous in funding TANF. On the other hand, if thereare few people on TANF, then it is not expensive to fund in absolute dollars. Thusour hypothesis is that as the percentage of a states population on TANF goes up,

states will make less of a tax effort to fund the program. This hypothesis receivesstrong support, with the percent on TANF correlated at 0.40 (p < 0.01) with theTANF tax effort.

To get a better sense of which indicators are most predictive of TANF tax effortwe employ a multivariate model. There are at least two constraints that merit dis-cussion. First, we have just 50 cases. That means at most we can consider five vari-

ables at a time before compromising the analysis with reduced degrees of freedom.Second, several of the independent variables are strongly intercorrelated. As wenoted above, percent black and percent Democrat are correlated at 0.64. Entering

both these items in a regression equation will inflate the standard errors, makingit unlikely either variable is statistically significanteven though both may well besubstantively significant.

Our strategy is to test a variety of model specifications using ordinary least

squares (OLS), and attempt to arrive at a solution that combines parsimony withthe strongest theoretical expectation. Once that model is specified in a satisfactory

manner, we elaborate on it by either adding or replacing other variables discussedabove.

The literature on welfare spending tends to focus on three dimensions: (1) state

economic factors, (2) the cost each state faces as measured by the percentage of thestate population receiving assistance, and (3) race. Our initial model focuses onindicators of these three dimensions.

We looked first at cost versus resources, with cost measured as the percent ofthe state population on TANF and the resources measured as total taxableresources per capita. In this simple two variable model, shown as model 1 in Table

1, both items are significant at p < 0.05. However, the coefficient (beta) for the

State TANF Spending 755

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

12/16

the economic resource base a state has to pay for TANF. Still, the two variable modelaccounts for 22% of the total variance, and fits well with other approaches toexplaining welfare spending.

The next variable entered is the change in unemployment between 1997 and2003. We would expect a downward trend in a states economic fortunes to leadto a shift in priorities away from politically unpopular programs. As shown in model

2 in Table 1, the coefficient reaches statistical significance (p < 0.05), and the hypoth-esis is supported. In fact, the coefficient for changing economic conditions is almostas large as that for total taxable resources. The explained variance for model 3

increases to 27 compared to model 2. As unemployment increases, TTE decreases

or is stagnant. Notice that entering the unemployment variable has no effect onthe coefficient for total taxable resources. It does, however,increaseby 15% the coef-

ficient for percent of the population on TANF.3 In other words, as economic con-ditions in a state deteriorate the percent of the population on TANF becomes moreimportant as a predictor of the tax effort a state will make to fund TANF. Perhaps

this is nothing more than a general trend in state tax effort toward all programsin times of economic difficultly. It would, however, be interesting to determine ifthe same pattern held across other state spending programs. Or is it unique to a

politically unpopular welfare program with a large percentage of black recipients,as scholars like Gilens (1999) imply.

Next, we enter the percent of the state population that is African American. In

theory (at least utopian theory) this item should have no effect. We have accounted

756 Harrell R. Rodgers, Jr. and Kent L. Tedin

Table 1. Regression of Independent Variables on TANF Tax Effort

Model 1

B(s.e.) Beta

Total Taxable Resources 134.5 (58.6)** 0.290Percent on TANF 43.9 (14.5)*** 0.405

R2 = 0.22

Model 2B(s.e.) Beta

Total Taxable Resources 137.1 (56.7)** 0.296Percent on TANF 55.5 (14.7)*** 0.479Unemployment change 0.83 (0.040)** 0.265

R2 = 0.27Model 3

B(s.e.) Beta

Total Taxable Resources 134.6 (53.7)** 0.290Percent on TANF 61.2 (14.1)*** 0.529Unemployment change 0.92 (0.038)** 0.293Percent Black 2.54 (1.0)** 0.296

R2 = 0.34Model 4

B(s.e.) BetaTotal Taxable Resources 115.6 (61.0)* 0.290Tough Policies 26.2 (11.6)** 0.317Unemployment change 0.50 (0.041) 0.160Percent Black 2.78 (1.2)* 0.324

R2 = 0.23

Not significant*p < 0.10**p < 0.05***p < 0.01

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

13/16

wealth of the state, and changes in economic conditions. Entering the percent blackshould not have a significant effect. However, controlling for key economic factors,the percent black turns out to be a major predictor of the willingness of a state to

make a tax effort to support TANF (model 3). The explained variance in the modelincreases to 34%. We see in model 3 of Table 1 that the coefficient for percent black

is (slightly) higher than any other coefficient save the percent of the state popula-tion receiving TANF. Note also the effect of entering the percent black has onpercent receiving TANF. Comparing the coefficient for this variable in model 3 tothe same coefficient in model 2, we find that it increases by 11%. 4 Quite obviously,

it is not simply the percent of the state population on TANF that matters for statetax effort; it is racial composition of those receiving the state benefit. Not only isthe race variable itself significant, but entering the race variable increases the effect

of the percent receiving TANF.Finally, we ask if there is anything to be learned by adding additional variables

to the model. Adding the percent Hispanic yields a coefficient of near zeroevenif this variable is substituted for percent black. Adding percent Democrat in thepopulation is not significant, and renders the percent black insignificant as well(due to multicolinarity). We can substitute percent Democrat for percent black. The

beta coefficient for percent Democrat is significant (0.257,p < 0.05), but is smallerthan for percent black, and in our judgment not as theoretically meaningful.

Adding percent liberal to the equation shown in model 3 does not yield a signifi-

cant coefficient.Finally, we added the tough policies score. Recall, in the bivariate case, those

states that had adopted the tough policies made a greater tax effort to fund TANF

(although the bivariate relationship was not statistically significant). Entering thisscore into the fifth variable in the model 3 equation had virtually no effect, and isnot close to statistical significance.

Earlier we noted that with percent black in the state population controlled,tough policies have a significant positive effect on TTE. It is insightful to discoverwhy the variable is not significant when added to the variables included in model

3 of Table 1. The answer is the tough policies score is highly intercorrelated withthe percent of the state population on TANF (r = 0.48). States that have adoptedthe tough policies have the lowest levels of TANF use. In model 4 of Table 1 we

substitute the tough variable for the percent on TANF. The coefficient is 0.317,

and significant atp < 0.05. But, as we see in model 3, it is significantly smaller thanthe coefficient for percent on TANF. Thus the model 3 specification is preferred

in that it is a better fit to the data and yields more predictive regression coefficients.Still, it is important to understand that tough policies might explain why somestates have smaller TANF populations, which in turn is the best predictor of the

tax effort make by states to fund TANF.

Conclusions

State spending on TANF is not the result of thoughtful public policy. Instead, indi-vidual state spending levels reflect a combination of longstanding state decisions

about how much to spend per capita on AFDC/TANF, the lack of any federally

State TANF Spending 757

-

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

14/16

failure of the federal government to adjust federal grants to the states in responseto huge changes in welfare caseloads. The result is that differences in state spend-ing per TANF family or recipient are massive and basically unrelated to the size or

needs of their poverty populations.State tax efforts to support AFDC/TANF, the base of current spending, are the

product of several factors. As other studies have shown, our analysis reveals thatstates with larger black populations tend to keep spending low. The longstandingpolicy of states with larger black populations trying to discourage welfare use byminorities continues to influence their spending for TANF, a program with very

different goals than AFDC. Similarly, states with the highest percentages of theirpopulations on TANF hold their spending for cash and support services downdespite the potential of TANF to move poor and low-income families into the job

market and help them become established there. This is particularly true when asignificant percentage of TANF recipients are black.

State spending for TANF does reflect economic conditions within a state, buthardly perfectly. As the data in Figure 6 show, some states spend as much as theireconomies will allow, while others spend far below their capacity (Rodgers, 2005).

A rational funding policy for TANF would adjust federal grants for recent changes

in caseloads, require states spending to correspond to their economic capacity, andsubsidize states doing their share but still falling short because of weaker economiesor large caseloads. This more rational approach would give states a much better

chance of effectively implementing TANF and realizing its goals.

Notes

1 Taken from the 2000 Voter News Service Exit Poll. Edison Media Research and Mitofsky Interna-

tional. National Election Pool. Retrieved November 7, 2004, from http://www.exit-poll.net.

2 The work requirement had a loading of 0.45, while the other three items all loaded at more than

0.68.

3 From 0.405 to 0.479.

4 From 479 to 0.529.

About the Authors

Harrell Rodgers is Professor and Chair of the Department of Political Science at the Uni-

versity of Houston. His area of research is American poverty. The second edition of his analy-sis of recent welfare reform, American Poverty in an Era of Reform, was published in 2005.

Kent Tedin is Professor of Political Science at the University of Houston. His book, Ameri-can Public Opinion, 7th edition, coauthored with Robert S. Erikson, was published in 2005.He is currently working on public opinion and educational reform.

References

Alexander, F. K. (1997).Disparities in state tax effort for financing higher education. Paper presented at the Cornell

Higher Education Research Institute (CHERI) Higher Education Policy Research Conference, Cornell,

New York.

Berry, F. S., & Berry, W. D. (1990). State lottery adoptions as policy innovations: An event history analysis.

American Political Science Review, 84, 395415.

Berry W D Ringquist E J Fording R C & Hanson R L (1998) Measuring citizen and government ide

758 Harrell R. Rodgers, Jr. and Kent L. Tedin

http://www.exit-poll.net/http://www.exit-poll.net/ -

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

15/16

Blank, R. M. (2001). Declining caseloads, increased work: What can we conclude about the effects of welfare

reform?Economics Policies Review, 7(2), 2536.

Brown, M. K. (1999).Race, money, and the American welfare state. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Erikson, R., MacKuen, M., & Stimson, J. (2002). The macro polity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press.

Fording, R. C. (1997). The conditional effects of violence as a political tactic: Mass insurgency, welfare gen-

erosity, and electoral context in the American states.American Journal of Political Science, 41(1), 129.Fording, R. C. (2003). Laboratories of democracy or symbolic politics? The racial origins of welfare reform.

In S. F. Schram, J. Soss, & R. C. Fording (Eds.), Race and the politics of welfare reform.Ann Arbor: Uni-

versity of Michigan Press.

Fritzell, J., & Ritakallio, V. M. (2004). Societal shifts and changed patterns of poverty. Luxembourg Income Study

Working Paper No. 393. Syracuse, NY: Center for Policy Research, Syracuse University.

Gilens, M. (1999). Why Americans hate welfare: Race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. Chicago: Univer-

sity of Chicago Press.

Green Book. (2004). House Committee on Way and Means. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Halstead, K. (1994). State profiles: Financing public higher education 1978 to 1994 . Washington, DC: Research

Associates of Washington.

Handler, J. F. (1995). The poverty of welfare reform. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Hero, R. E. (1998).Faces of inequality: Social diversity in American politics. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Howard, C. (1999). Field essay: American welfare state or states?Political Research Quarterly,52, 421442.Nobel, C. (1997). Welfare as we knew it: A political history of the American welfare state. Oxford, UK: Oxford Uni-

versity Press.

Office of Economic Policy. (2003). United States Department of Treasury. Retrieved from http://www.treas.gov/

offices/economic-policy/resources/indez.html

Orr, L. L. (1976). Income transfers as a public good: An application of AFDC.American Economic Review, 66(3),

359371.

Plotnick, R. D., & Winters, R. F. (1985). A politico-economic theory of income distribution. American Political

Science Review, 79, 458473.

Rodgers, H. R. (2005, November). Saints, stalwarts, and slackers: State financial contributions to welfare

reform.Policy Studies Journal,33(4), 497508.

Rom, M. (1999). Transforming state health and welfare programs. In V. Gray & H. Jacobs (Eds.),Politics in the

American states (pp. 117131). Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Smeeding, T. M. (2004, February 20).Public policy, economic inequality, and poverty: The United States in compara-

tive perspective. Inequality and American Politics Conference, Maxwell School, Syracuse University,

Syracuse, New York.

Smeeding, T. M. (2005). Public policy, economic inequality, and poverty: United States in comparative per-

spective. Social Science Quarterly, 86, 955983.

Soss, J., Schram, S. F., Vartanian, T. P., & OBrien, E. (2001). Setting the terms of relief: Explaining state policy

choices in the devolution revolution.American Journal of Political Science, 45(2), 378395.

Stimson, J., MacKuen, M., & Erikson, R. (1995). Dynamic representation. American Political Science Review,

89(3), 543565.

Tannenwald, R. (1999, July/August). Fiscal disparity among the states revisited.New England Economic Review,

3, 325.

United States Department of Health and Human Services. (2004). Temporary assistance for needy families. 6th

Annual Report to Congress, chap. 2, p. 7. Washington, DC.Voter News Service Exit Poll. (2004). Edison Media Research and Mitofsky International. National Election

Pool. Retreived November 7, 2004, from http://www.exit-poll.net

State TANF Spending 759

http://www.treas.gov/http://www.exit-poll.net/http://www.exit-poll.net/http://www.treas.gov/ -

7/29/2019 State TANF Spending

16/16