ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC 2011 US Tour · ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC 2011 US Tour ... Why this...

Transcript of ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC 2011 US Tour · ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC 2011 US Tour ... Why this...

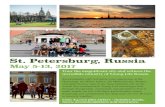

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC

2011 US Tour

Critical acclaim for artist

“This isn't a figure of speech, just a fact: My jaw dropped.”

“The gospel hymn of "Let God Arise" and the ecclesiastical theme "An angel wailed" permeated the hall with

a grand, gorgeous sound, with secure brass soaring atop magical and velvety strings — 50 of them — in

perfect unison. It was lush and brilliant, as a basketful of the most elaborate Fabergé eggs. The whole piece: a

new "best of" for Temirkanov.”

“It may seem strange to place so much emphasis on the opening overture, but it was truly unforgettable, a

musical bliss, whose surprise kept it sharply etched in memory even as the major portion of the evening was

thoroughly enjoyable.”

-San Francisco Classical Voice

“The Rachmaninoff and Rimsky were remarkable in many other ways as well. The orchestra addressed the

work‟s tidal pulls and deep currents with dark velvet sound; Lugansky‟s round tone was its perfect pianistic

match; a slowish first-movement tempo only accentuated the rolling waves.”

“As great as it was to watch Lugansky (and hear him), it was equally fun to watch the Maestro. Is there a

conductor with more eloquent hands than Maestro Temirkanov? He says so much with every gesture, and

even better — the orchestra responds in sound — curling a phrase to a gentle close, evaporating another into

thin air.”

“The colors were glorious, as they should be, and the pacing was, well, as spellbinding as Scheherazade‟s

stories had to be to keep the Sultan rooting for more tomorrow. A thousand and two nights of playing like

this would not be too much.”

-AnnArbor.com

“The sound of the murmuring low brass chords that began this performance seemed not to be coming from the stage

but seeping up through the floorboards under the seats. After an atmospheric episode, the piece broke into a spiraling

dance, sometimes crazed, sometimes delicate with gossamer textures. Why this 1909 tone poem is not as popular as

Dukas‟s “Sorcerer‟s Apprentice” I cannot imagine.”

“The major works on Wednesday‟s program were Rachmaninoff‟s Second Piano Concerto and Rimsky-Korsakov‟s

“Scheherazade.” By offering these two repertory staples, Mr. Temirkanov raised the stakes here: a real Russian orchestra was going to show us all how this music should be played. And show us they did.”

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC 2011 US TOUR QUOTES

Page 2

“In this performance, rather than striving to capture the exotic qualities of the music or summoning veiled sounds and

hazy textures, Mr. Temirkanov and his players told stories in music. Everything was direct, vivid and full of character. The rocking orchestral figure that fortifies the opening theme of “The Sea and Sinbad‟s Ship” evoked not lapping

waves but oceanic turbulence.”

-The New York Times

“This was a muscular, forward-moving, astutely proportioned reading, but one that was also deeply felt and beautiful as

sheer sound.”

“And, crucially, Temirkanov knows how to build climactic moments for maximum punch. Aided by his searing,

robustly satisfying brass section, this was a performance of the Brahms that concluded with thrilling exuberance.”

“As if this program weren‟t bounty enough, an encore of the “Nimrod” movement from Elgar‟s Enigma Variations

topped the rest with a welling-up of gorgeous string tone and burnished brass that Temirkanov sculpted into a

performance as heartfelt and moving as any I‟ve ever heard.”

-The Washington Post

“Tuesday's concert found Temirkanov in typically high-voltage form. He turned the curtain-raiser, Rimsky-

Korsakov's "Russian Easter" Overture into a real barn-burner, a one-act drama of terrific intensity and color.

The orchestra gave him thunderous fortissimos that never turned vulgar and handled the fastest passages with

remarkable finesse.”

“She offered fierce intensity in the outer movements. In the heart of the concerto, the pensive Moderato and

extended Cadenza, Weilerstein achieved richly eloquent results, burrowing far beneath the black and white of

the score. It was an absorbing performance.

The Philharmonic's contributions, including vivid horn solos, likewise proved stellar.”

-The Baltimore Sun

“The orchestra‟s blueprint is a sound so deep that bold dashes of individual expression — of which the

“Russian Easter Overture‟‟ offered plenty, none of it shy — seemed to grow out of the ensemble, rather than

glance off it. A big, burnished foundation from the cellos and basses ran like a spine through the orchestra;

the woodwinds layered in wide-bandwidth, organ-like tones. Yuri Temirkanov, the group‟s longtime

conductor, marked architecturally elegant outlines with a kind of nonchalant grace, the players filling in his

frames with rich finish.”

-Boston Globe

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC 2011 US TOUR QUOTES

Page 3

“Temirkanov brought out an uncommon refinement in this music that neatly balanced the fireworks with

notable individual contributions including an eloquent solo by first trombone Maxim Ignatyev and the sweet-

toned violin of concertmaster Lev Klychkov. Yet the orchestra opened up with all due fire and corporate

brilliance in the boisterous final section with some dazzling violin playing by the entire section at a very fleet

tempo.”

-Chicago Classical Review

“The performance crackled with electricity and the audience leapt to its feet in one of those rare standing

ovations that was fully deserved.”

-Palm Beach Daily News

“The single encore was Edward Elgar's "Salut d'Amour," given such fine-toned tenderness that listeners

responded with a satisfied, „Ahh.‟”

-Chicago Tribune

“Temirkanov is a micromanaging conductor but also one with a flair for sweeping dramatic gestures that

seemed here designed to tell stories.”

“At intermission I heard what seemed like half the audience humming the opening march motif, so

effectively did she [Alisa Weilerstein] drill it into our heads (I‟m still humming as I type).”

“Brahms‟ Fourth Symphony after intermission was extraordinary. Temirkanov sought out a Russian soul that

the German composer could not have known he had. The phrasing was flexible, with strings in the first

movement sighing Slavic sighs. Reedy, ripe woodwinds in the Andante might well have been playing

saturnine Tchaikovsky, with the horns and brass snarling in the background. A flute solo in the Finale was an

Onegin in the ravages of self-pity, as the movement, based on a Baroque chaconne structure, inexorably

brandished fate‟s will.”

-Los Angeles Times

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

Critical acclaim

“Russia‟s oldest symphony orchestra surpassed all expectations...the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra spilled forth

music in the purest form possible - straight from each score‟s soul and into the hearts of listeners.”

- The Washington Post

“Something alchemic occurred Thursday night at Meyerhoff Symphony Hall. Yuri Temirkanov took standard works of

the Russian repertoire, poured them into his St. Petersburg Philharmonic, stirred them with his unselfconscious ideas

about the nature of music making, and created sonic gold...As a demonstration of pure orchestral mettle, the performance would have been striking enough. As an expression of music‟s visceral power, it was simply profound.”

- The Baltimore Sun

“No acoustical properties in any hall can account for the string sound this orchestra makes, which seems to emanate out of

the stage floorboards and throb with a dark, slightly opaque glow...Voluptuous, seductive, almost bursting out of its

clothes, this Russian musical institution offers a nice alternative to the rail-thin, runway model elegance of western

symphony orchestras. Indeed, the St. Petersburg Philharmonic is quite a beauty...” - The New York Times

“[Temirkanov] knows that the podium is the last refuge on earth for the gods, and when you‟re a god you don‟t have to prove it to anyone.”

- The Philadelphia Inquirer

“These splendid players share their musical DNA with this [all-Russian] repertory and they enjoy a close rapport with

Yuri Temirkanov, their music director for the past 16 years. His courtly podium manner belies the Slavic intensity of

feeling that flows like an electric current through his elegant hands to the musicians, and, through them, to the rapt

audience.” - The Chicago Tribune

“Temirkanov doesn‟t beat time; he shapes and sculpts, encouraging here, nudging there, always alert to the smallest nuances of the score. As for the orchestra, it seems a thing alive..the orchestral rubato in the Symphony‟s first movement

was astonishing. Phrases swelled forth, accelerating minutely, then ebbing again within seconds, always in strict time.

This is truly a „breathing‟ orchestra. The St. Petersburg Orchestra‟s string sound is rich, full and singing; the woodwind sound is sparkling and bright; and the brass...is powerful and incisive.”

- The Kansas City Star

“The program began and ended with shimmer and radiance...the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra under the direction of Yuri Temirkanov provided drama, brilliance, lyricism and a bracing antidote of steeliness.”

- Ann Arbor News

“...never short of breathtaking...Temirkanov and the orchestra made one hear just how masterfully he deployed the

instruments of the orchestra, combining them in piquant blends of sonorities and balancing their temperaments in new and

exotic ways.”

- The San Francisco Chronicle

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC

Page 2

“The strings pulsed with an almost unnatural plushness, the brass and woodwinds supported the tune with gracious

subdued harmonies. It was breathtaking.”

The San Francisco Chronicle

“The St. Petersburg strings (nearly 70) are utterly unified in sound, deep but not fat, focused. They are staggeringly exact

in temperament and technique. They can go from the silkiest of double pianos to most majestic double fortes in the space of a single breath. The double basses and cellos possess a lovely richness, powerful and dark, but frequently mellow,

while the violins and violas are brilliant and authoritative. Rarely will one hear a more vivid, more organic, more

individual reading. Every phrase seemed freshly minted, vigorously alive.”

- The Seattle Post–Intelligencer

“There was no mistaking the distinctive Slavic timbral edge, innate passion and unified fervor of the St. Petersburgers.”

The Los Angeles Times

“Two metaphors came to mind Sunday while listening to the St. Petersburg Philharmonic at the Van Wezel Performing

Arts Hall: a well-oiled machine and a thoroughbred racehorse. Upon reflection, the equine image is the more compelling,

for this is an extraordinary orchestra, one that displayed both its distinguished heritage as Russian‟s oldest symphony and

its enormous resources of opulent tone and fierce energy.” Sarasota Herald-Tribune

“…the string playing was lush and full, the woodwinds had much character and clarity to the sound, and the brass solos

were downright heroic….the music making itself has an uninhibited, gloriously flowing character to it.”

Newark Star-Ledger Reviews of Verdi’s Requiem Recording 2010

“This is a full-blooded performance of Verdi‟s late work… Full marks for passion.”

The Daily Telegraph, January 2010

“The playing is finely articulated, strong and fiery in the „Dies irae‟, the brass expert and thrilling at the „Tuba mirum‟,

and with many other instrumental highlights throughout.

“The tone of the Mikhailovsky Theatre Chorus, founded on the legendary quality of sepulchral Russian basses is

impressive…Carmen Giannattasio has a rich soprano voice and shows a clear understanding of her part‟s expressive range. She is well matched by mezzo Veronica Simeoni, and their dueting in the „Recordare is outstanding. Bass Carlo

Colombara matches his Russian choral colleagues in singing that combines grandeur with nobility. The only Russian

soloist, tenor Alexander Timchenko shows exceptional delicacy and technical aplomb.

“Conductor Yuri Temirkanov‟s measured approach…possesses an honesty and integrity of its own.”

BBC Music Magazine, March 2010

“In a world hardly short of recordings of this most stirring and human of liturgical works, a new Verdi Requiem really

needs to be special to make any impact in the established discography. I suppose that I must be familiar with dozens of versions and as such am in danger of being hard to please. However, I was immediately impressed by Temirkanov‟s

expert pacing of the tentative, descending string figure which opens the work, and the tension generated by his careful

phrasing in the choir‟s increasingly assertive interpolations. My expectations were further raised by the firm vigour of the soloists‟”

MusicWeb, March 2010

“Yuri Temirkanov‟s mature and considered performance wears its own character with pride… The superb St Petersburg

Phil add to the potency of the mix.”

The Sunday Times, London, February 2010

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC Washington Post • February 13, 2014

Temirkanov, St. Petersburg Philharmonic show sonic opulence at Strathmore BY ANNE MIDGETTE Some of the season’s most anticipated concerts have run into conflicts with the weather this winter. A couple of weeks ago, the Takacs Quartet played through a snowstorm to a diminished audience in the Terrace Theater. On Wednesday night, the Washington Performing Arts Society brought the St. Petersburg Philharmonic to Strathmore, and there were so many weather advisories and state-of-emergency announcements that it seemed impossible that anyone would come. No fear. The orchestra is a Russian national treasure, conductor Yuri Temirkanov one of the best in the world, and one could even assume that the Russian contingent of the audience — which was considerable — knows how to deal with a little snow. The hall was, if not packed, at least respectably filled. The orchestra didn’t disappoint. The conditions, true, were a little unusual: The orchestra dropped the “Barber of Seville” overture from its scheduled program and played the two other pieces, Prokofiev’s second violin concerto and Rachmaninoff’s second symphony, without intermission as a concession to the audience’s need to get on the roads before the snow got too bad. You could argue that this detracted slightly from the sense of occasion and pacing of the evening. But it took nothing from the sound of the orchestra: lush velvety clouds of it, pillowing out from the stage. Temirkanov is a brilliant conductor and a gentle one, leading with urbane understatement, coaxing the music out of the orchestra rather than trying to force himself upon it. The ear luxuriated in tactile, even simple aural pleasures: the chuff of a double-bass, the liquidy burble of the winds, or the spinning wonder of a well-balanced chord, dozens of voices enmeshed in a kind of spinning, suspended globe of sound hovering over the stage. Sayaka Shoji, the soloist in the Prokofiev, was new to me. She was scheduled to perform the same work with Temirkanov in 2006, when he was music director of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, but he had to withdraw from that performance, so this was a kind of make-up date. Her sound was light as a wire and a little steely, growing in authority and intensity as the piece progressed. It was a fine performance without quite being a dazzling one — something unfortunately spotlighted by the contrast with the sonic opulence of the ensemble behind her. Temirkanov also played the Rachmaninoff second symphony in Baltimore. (How could he not? It’s a repertory staple.) On Wednesday, his dry urbanity tamed the score’s sprawl. This is a big and very pretty symphony, and Temirkanov and the orchestra did full justice to its beauty while making it sound downright elegant, not quite milking the bathos of the slow movement and bringing elasticity and verve to the final one. It may not have been a profound evening, but it was an enjoyable one. Despite the implicit need to hurry home, the audience drew two encores from the orchestra: a little and understated but pretty piece from Schubert’s Moments Musicaux, and delightfully raucous trombone solos, juxtaposed with the double bass, in the Vivo from Stravinsky’s

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Washington Post • February 13, 2014 page 2 of 2 “Pulcinella.” The two soloists came forward, at the conductor’s insistence, for solo bows, something he forced on them all the more by literally pushing them down, without himself turning on the podium: a stamp on an evening that very effectively highlighted the playing of a wonderful orchestra and was a reminder of why we in this region miss the regular presence of Temirkanov.

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC Russia Beyond the Headlines • February 4, 2014

St. Petersburg Philharmonic on U.S. tour Starting from February 12, the St. Petersburg Philharmonic will be touring the United States. BY AMY BALLARD During February and March, the St. Petersburg Philharmonic will be touring the United States with Maestro Yuri Temirkanov to present what it plays best: a repertoire of Russian music with works by Prokofiev, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, Rimsky-Korsakov, and contemporary composer Gya Kancheli. The group is a singular one. As Boston Globe critic Matthew Guerrieri remarked on its 2011 tour, “The St. Petersburg Philharmonic is a magnificent musical machine, one in which the engineering is of such precision that it becomes expressive in and of itself.” Or, as concertmaster Lev Klychkov said, “We play with our hearts.” While the orchestra may not be well know to U.S. audiences, Temirkanov is familiar to concertgoers throughout the world from his affiliations with London’s Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the Danish National Symphony, and the Teatro Regio di Parma in Italy, among others. In the United States, particularly in the Baltimore and Washington, D.C., areas, he is remembered fondly for his tenure as music director of the Baltimore Symphony from 2000 to 2006. In St. Petersburg, Temirkanov oversees the International Arts Square Winter Festival, held every December. Many artists have made their Russian debut at this festival, including Leif Ove Andsnes, Lang Lang, and Julia Fisher. Each June and July, Temirkanov directs the “Musical Collection International Festival” with such luminaries as Thomas Hampson, and Helene Grimaud. This festival was actually my introduction to the St. Petersburg Philharmonic, which I first heard in 2001. Although I’d been traveling to Russia since 1973, I had never been in the winter. An American friend was organizing the 2001 festival. The first time I walked into the Philharmonic Hall, it was clear this was a very special place, and that the orchestra and the audience revealed a deep respect for each other. The orchestra’s home is the D.D. Shostakovich Philharmonic Hall. Under the auspices of Carlo Rossi, architect Paul Jacob designed the hall in the early 19th century as an assembly hall for the nobility with special emphasis on acoustics. The hall, subtly altered since its construction, has been witness to much history, from Tsar Nicholas I addressing the nobility, to a distraught Rachmaninoff after the premiere of his first symphony, which failed not because of the power of the piece, but under rehearsal. Under happier circumstances, the first ball of Grand Duchess Olga, the eldest daughter of Tsar Nicholas II, was held in the hall shortly before the beginning of World War I. Perhaps the most famous event held there was the performance by a skeletal group of musicians of Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony during the horrific 900-day siege of the city during World War II. Although the hall was

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Russia Beyond the Headlines • February 4, 2014 page 2 of 2 renovated in 2007 to install much-needed air conditioning, the acoustics are still among the finest in the world. Today, the hall is also home to the St. Petersburg Academic Symphony Orchestra and also hosts a variety of musical events. On December 14, 2013, Temirkanov celebrated his 75th birthday at Philharmonic Hall, with a gala concert in his honor. Conductor Mariss Jansons led the St. Petersburg Philharmonic with soloists Vadim Repin, Denis Matsuev, Yuri Bashmet, Natalia Gutman, Sayaka Soji and others. It is a fitting tribute to the esteemed conductor who through his orchestra and the Maestro Temirkanov Foundation for Cultural Initiatives does so much to ensure that music is brought to people of all ages. The orchestra is famous for its resplendent strings. Concertmaster Lev Klychkov, an award-winning graduate of the Leningrad Conservatory, was selected by Conducter Yevgeny Mravinsky to join the orchestra in 1982. His first tour to the United States was in 1990. “I was only 29 years old. My wife had just given birth to our son while I was away. I remember going to the A&P store in New York City and buying boxes of Pampers to take back. No one in Russia had seen these. It was a difficult time for my country, and meeting Americans was like an injection of energy for me. I have been to America more than 15 times, and I love the American people and their open hearts.” These warm sentiments are felt by many of the orchestra’s musicians including Pavel Popov, the associate concertmaster, who joined the orchestra in 2004. “I feel wonderful about the countryside of America, the small cities and nature which is so different. I love Carnegie Hall and to perform in that great place.” What makes the St. Petersburg Philharmonic special? The musicianship for one. Many of the musicians attended the School for Gifted Children and later the St. Petersburg Conservatory, so they learned from the best. They rehearse almost daily and often in sections before and after rehearsals or at a special time, to prepare for their concerts. On their off hours, most teach at the Conservatory and participate in chamber groups, adding much to the rich musical life of the city. Tour Dates: Feb, 12 - North Bethesda, MD Feb, 13 - New York, NY Feb, 14 - Greenvale, NY Feb, 15 - New York, NY Feb, 16 - Newark, NJ Feb, 18 - Ft. Lauderdale, FL Feb, 19 - Sarasota, FL Feb, 21- West Lafayette, IN Feb, 22 - Ann Arbor, MI Feb, 23 - Chicago, IL Feb, 24 -East Lansing, MI Feb, 27- Palm Desert, CA Feb, 28 - San Diego, CA Mar, 1 - Las Vegas, NV Mar, 2-3 - San Francisco, CA Mar, 4 - Davis, CA Mar, 8-9 - Mexico City, Mexico

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra

New York Times • April 15, 2011

Finding the Soul of Russia Everywhere

BY ANTHONY TOMMASINI

Did you know that the sighing first theme of Brahms’s Fourth Symphony is actually a Russian folk song? Or that the

mellow chorale played by the woodwinds at the beginning of the slow second movement is obviously inspired by a

Russian Orthodox male choir?

None of this is true, of course. But on Thursday night at Carnegie Hall, in the second of two programs, Yuri

Temirkanov conducted the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra in a fresh, intriguing performance of Brahms’s

Fourth Symphony that had this Germanic music sounding somehow Russian. We are supposedly living in an era in which the world is getting smaller, and distinctive national characteristics of orchestras are becoming homogenized into

an international style. But Russian orchestras have clung more strongly to their roots, and to the characteristic Russian

sound that favors dark colorings, mellow brass, reedy woodwinds and weighty textures; particularly this Russian orchestra, founded in 1882.

This impression was reinforced by the programs chosen by Mr. Temirkanov, the artistic director and principal

conductor of the St. Petersburg Philharmonic for 23 years. Of six pieces on the two programs, the Brahms was the only

non-Russian work.

Wednesday’s concert began with “Kikimora,” a seven-minute tone poem by Anatoli Liadov, a student of Rimsky-

Korsakov. In the bizarre Russian fairy tale depicted here, Kikimora is a witch raised from infancy by a magician, who

regales her with stories while rocking her in a crystal cradle. At 7, the witch is still the size of a thimble, yet already plotting evil for the world.

The sound of the murmuring low brass chords that began this performance seemed not to be coming from the stage but

seeping up through the floorboards under the seats. After an atmospheric episode, the piece broke into a spiraling

dance, sometimes crazed, sometimes delicate with gossamer textures. Why this 1909 tone poem is not as popular as Dukas’s “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” I cannot imagine.

The major works on Wednesday’s program were Rachmaninoff’s Second Piano Concerto and Rimsky-Korsakov’s

“Scheherazade.” By offering these two repertory staples, Mr. Temirkanov raised the stakes here: a real Russian orchestra was going to show us all how this music should be played. And show us they did.

The virtuoso Russian pianist Nikolai Lugansky was the impressive soloist in the Rachmaninoff. Mr. Lugansky, true to

the Russian Romantic heritage, plays with a plush sound and plenty of impetuosity. But, born to two scientists, he is also an analytic musician. In the opening of the concerto, which begins with a series of ominous chords that grow in

sound and intensity, Mr. Lugansky voiced each one to highlight harmonic intricacies. And when the surging main

theme broke out in the orchestra, he brought penetrating sound and sweep to the rippling piano arpeggios that

accompany the melody.

Throughout this piece, with Mr. Temirkanov drawing elemental sound from the ensemble, Mr. Lugansky brought

clarity, power and flair to his playing. But it was in the most subdued passages that his performance especially touched

me, like the opening of the slow movement, when he shaped the simple pattern of notes that accompany a mournful solo clarinet into an undulant harmonic ripple.

“Scheherazade” depicts some of the nightly stories that the alluring Scheherazade tells her husband, an avenging sultan

who considers each of his wives false. In this performance, rather than striving to capture the exotic qualities of the music or summoning veiled sounds and hazy textures, Mr. Temirkanov and his players told stories in music.

Everything was direct, vivid and full of character. The rocking orchestral figure that fortifies the opening theme of “The

Sea and Sinbad’s Ship” evoked not lapping waves but oceanic turbulence. When the ship is wrecked in the final

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra

New York Times • April 15, 2011 page 2 of 2

movement, the playing was visceral, breathless and cinematic, despite some scrappy moments. The concertmaster Lev

Klychkov played the prominent violin solos with rich sound and fine-spun lyricism.

Thursday’s program began with a gorgeous account of the Prelude to Rimsky-Korsakov’s great opera “The Legend of

the Invisible City of Kitezh.” After the murky opening measures of the music, when a chorale theme emerged, the

chords were shrouded in magical mists of strings and orchestral sonorities.

The brilliant young American cellist Alisa Weilerstein, whom I had not heard since 2009 when she took part in

Classical Music Day at the White House, was the compelling soloist in a first-rate performance of Shostakovich’s Cello

Concerto No. 1. Again, playing with incisive rhythm and crisp articulation is not this orchestra’s strong suit. But between Ms. Weilerstein’s impassioned, intelligent playing and the richness and color of the ensemble, this was an

organic and arresting account of a great work, one of dozens of major 20th-century scores written for Mstislav

Rostropovich.

After all this, how could the bold, vibrant performance of the Brahms symphony not come across as sort of Russian? For an encore, Mr. Temirkanov played the “Nimrod” portrait from Elgar’s “Enigma” Variations, drawing lush, dark,

cresting sound from his orchestra. No surprise, this landmark British work sounded Russian too.

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra

Washington Post • April 13, 2011

Temirkanov’s appearance at Strathmore reminds Washington of

what it’s missing BY JOE BANNO

Yuri Temirkanov is sorely missed. The veteran maestro, who still ranks as one of the world’s most insightful and

compelling podium presences, used to be a regular visitor to the Washington area when he helmed the Baltimore

Symphony. His Strathmore Hall appearance Tuesday with the St. Petersburg Philharmonic reminded us how cherishable his now-rarer appearances have become.

Temirkanov has been artistic director and chief conductor of the Philharmonic since 1988 (and had been conducting

them since 1967, when the legendary Yevgeny Mravinsky was his mentor). That long familiarity with his players was

evident throughout Tuesday’s program — not least in the way that Temirkanov could be physically still for stretches of time, letting the orchestra do their work, and then conduct them (without a baton) using gestures that swept or carved

the air, or teased minute bits of affectionate phrasing from them. But it’s what he was able to bring to a set of warhorse

scores that made the music-making truly special. Right from the opening measures of Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Russian Easter Overture,” his refusal to hurry the music along, his way of subtly blending wind and stringlines, his use of the

rests to create evocative silences that hung in the air, all contributed to an interpretation that made the music sound

richer and more meaningful than perhaps it is.

Likewise, he approached the great, if over-familiar, Brahms Fourth Symphony in a way that made us hear it afresh. This was a muscular, forward-moving, astutely proportioned reading, but one that was also deeply felt and beautiful as

sheer sound. There were echoes of Otto Klemperer’s classic performances of the piece in the way that the music

sounded as if it had been hewn from a slab of granite. But I was reminded, too, of Herbert von Karajan, in the plush, seamless legato Temirkanov drew from the strings: The violins still display some of that keen edge they possessed in

the Soviet era, when this ensemble was known as the Leningrad Philharmonic, but they are also significantly sweeter

and rounder of tone these days. There were countless felicities of phrasing along the way, not least from an eloquent group of windplayers. And, crucially, Temirkanov knows how to build climactic moments for maximum punch. Aided

by his searing, robustly satisfying brass section, this was a performance of the Brahms that concluded with thrilling

exuberance.

Shostakovich’s alternately wry, acerbic, sorrowful Cello Concerto No. 1 — premiered by this orchestra in 1959 — delivered its requisite punch in a keen orchestral reading, crowned by a magisterial performance by cellist Alisa

Weilerstein. This score sounded as natural a fit for Weilerstein’s temperament as it did for an orchestra that has

Shostakovich’s music in its DNA. She offered trenchancy and atmospherically gritty playing when called for but, just as tellingly, was able to delve probingly into the solo part’s deep and troubled vein of introspection. Indeed, like

Temirkanov, this is a musician who understands the value of fraught silence.

As if this program weren’t bounty enough, an encore of the “Nimrod” movement from Elgar’s Enigma Variations topped the rest with a welling-up of gorgeous string tone and burnished brass that Temirkanov sculpted into a

performance as heartfelt and moving as any I’ve ever heard.

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra

The Baltimore Sun • April 13, 2011

Termirkanov leads St. Petersburg Philharmonic in high-powered

concert at Strathmore BY TIM SMITH

It was one of those deja-vu-all-over-again moments when Yuri Temirkanov

walked onstage at Strathmore Tuesday night.

Just seeing that aristocratic bearing and thin smile brought back memories of

those few, downright glorious seasons filled with intensely involving music-

making when he was at the helm of the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra.

For Tuesday's event, presented by the Washington Performing Arts Society,

Temirkanov was appearing with the St. Petersburg Philharmonic, his main

artistic focus since 1988.

I still remember when he brought that orchestra to the BSO's home turf for a

performance a Meyerhoff Hall fairly early into his Baltimore tenure. A lot of

BSO players attended and, on the way out afterward, I bumped into one of

them, who, looking almost shell-shocked, turned and said: "So that's how he

wants us to play."

Temirkanov didn't really try fashioning the BSO into a copy of the St. Petersburg ensemble, but he did want

to summon the richest possible tone and the deepest, most soulful phrasing he could. That he succeeded on

many occasions is why a lot of us will always retain such fond recollections of his time here.

But enough of the sentiment. On with the review.

Tuesday's concert found Temirkanov in typically high-voltage form. He turned the curtain-raiser, Rimsky-

Korsakov's "Russian Easter" Overture into a real barn-burner, a one-act drama of terrific intensity and color.

The orchestra gave him thunderous fortissimos that never turned vulgar and handled the fastest passages with

remarkable finesse.

The Russian mood continued with ...

Shostakovich's eventful Cello Concerto No. 1, the sort of

music Temirkanov knows intimately from the inside. His

guiding hand on the podium ensured that each orchestral

detail was carefully molded as he provided ever-supple

partnering for the soloist, Ailsa Weilerstein.

She offered fierce intensity in the outer movements. In the

heart of the concerto, the pensive Moderato and extended

Cadenza, Weilerstein achieved richly eloquent results,

burrowing far beneath the black and white of the score. It was an absorbing performance.

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra

The Baltimore Sun • April 13, 2011 page 2 of 2

The Philharmonic's contributions, including vivid horn solos, likewise proved stellar.

The evening's second half was devoted to Brahms' Fourth. Temirkanov has a particular affinity for the

muscular side of the composer's romanticism. He likes to rev up the engine and pump up the volume, as he

did here in the last two movements to riveting effect.

Earlier, Temirkanov's distinctive way of adding a tiny pause between the first and second plaintive notes of

the opening movement paid poetic dividends (it subtly accentuated the sighing quality of the main theme),

while his ability to draw an extra layer of sonic darkness from the orchestra emphasized the dark clouds

behind the Andante.

If you tried hard, you could detect a premature entrance from a string player here, a brass player there; maybe

even a slightly smudgy patch of articulation within one section of the orchestra or another. But that would

require some fierce nit-picking in light of so much technically polished, expressively vibrant playing from a

clearly inspired Philharmonic.

I noticed several new faces, many of then young, in the ensemble since the last time I heard it. That may

account for some of the vitality emanating from the stage, but the power source was clearly Temirkanov,

whose baton-less hands continue to communicate in inimitable ways and whose ability to get musicians to

deliver edge-of-their-seat music-making remains wonderful to behold.

The whole evening was vintage Temirkanov,right down to the sublime encore -- "Nimrod" from Elgar's

"Enigma Variations," which he used on BSO tours, too. This conductor may not surprise you often with

repertoire choices, but, it seems, he is as capable as ever of shaking you up by giving familiar fare fresh

impact.

Incidentally, in case you missed it, I did an interview with Temirkanov for last Sunday's Sun. He had some

interesting things to say, I think. Prior to press time, I was not successful in getting anyone in the BSO to

respond to a question about the chances of the orchestra's music director emeritus returning for a guest slot in

the future. But I heard that a BSO official was at Tuesday's concert, so maybe the subject was raised

backstage.

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra

Boston Globe • April 11, 2011

St. Petersburg Philharmonic brings precision to Symphony Hall BY MATTHEW GUERRIERI

Yuri Temirkanov, artistic director

With Alisa Weilerstein, cello

Presented by Celebrity Series of Boston

At: Symphony Hall, Sunday

“Machine-like’’ is not normally a musical compliment, but the St. Petersburg Philharmonic is a magnificent

musical machine, one in which the engineering is of such precision that it becomes expressive in and of itself.

Their Sunday concert at Symphony Hall opened with Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Russian Easter

Overture,’’ a dazzling test lap: the unison woodwind chant at the outset polished to a high gloss; shifts of

color and tempo automatic-transmission smooth; the rhythmic energy so effortlessly sure-footed that the

power and speed went almost unnoticed amid the comfort of the ride.

And yet the machine never was merely efficient. The orchestra’s blueprint is a sound so deep that bold dashes

of individual expression — of which the “Russian Easter Overture’’ offered plenty, none of it shy — seemed

to grow out of the ensemble, rather than glance off it. A big, burnished foundation from the cellos and basses

ran like a spine through the orchestra; the woodwinds layered in wide-bandwidth, organ-like tones. Yuri

Temirkanov, the group’s longtime conductor, marked architecturally elegant outlines with a kind of

nonchalant grace, the players filling in his frames with rich finish.

Dmitri Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1, a work the orchestra premiered back in 1959, put a menacing

spin on the ensemble’s confidence. The soloist was the American cellist Alisa Weilerstein; while the

orchestra cultivated an illusion of ease, Weilerstein’s expression was often purposefully effortful, with

flamboyantly percussive bowing and wiry sounds. But the contrast worked. In the grim marches of

Shostakovich’s outer movements, her intensity chafed against the orchestra’s crisp, implacable accents. It

made the inner movements all the more affecting, their restrained lyricism like the sun behind a haze of

clouds, Weilerstein drawing out long, limpid threads of spun glass.

The Symphony No. 4 of Johannes Brahms started in slightly blatant form, a little more edge and less rigor

than the playing in the concert’s first half, but the performance settled in by the end of the second movement,

with waves of resigned grandeur. The Allegro giocoso was both plush and unpredictable, a roller coaster with

deep cushions, transformed into a keen, dark cortège for the finale. But the luxury of the sound was balanced

by Temirkanov’s disciplined, classical phrasing. That combination of restraint and splendor was perfectly

suited to the encore, the “Nimrod’’ movement from Elgar’s “Enigma’’ Variations, rendered as one great,

noble, volcanic sigh.

N E W Y O R K • L O S A N G E L E S

St. Petersburg Philharmonic

Palm Beach Daily News • April 7, 2011

St. Petersburg Philharmonic, Nikolai Lugansky give lush

reading of Rachmaninoff concerto at Kravis

BY KEN KEATON

The St. Petersburg Philharmonic, under conductor Nikolai Alexeev, performed at the Kravis Wednesday

night in the first of two programs. Pianist Nikolai Lugansky was the soloist in the finest Rachmaninoff 2nd

this reviewer has ever heard.

No, not that St. Petersburg, the one next to Tampa; this is the one in Russia, more properly known as

Petrograd (or Leningrad during the Soviet era). The orchestra was founded in 1882. For a half-century, it was

led by Evgeny Mravinsky, whose white-hot performances of Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich are legendary.

Alexeev has been the conductor since 2000, and led the orchestra in this evening’s concert. It presented two

works: the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2 in C Minor and Rimsky-Korsakoff’s Scheherazade.

The orchestra is essential in a Rachmaninoff concerto — it must provide a lush bed of sound, waves of rich,

intense sonorities and expressive soloists to surround the piano. A more idiomatic performance can hardly be

imagined. But the soloist is the one who makes or breaks the performance, and Lugansky delivered.

He is young and charismatic — so young looking that it is surprising to realize that his career has been in

high gear for a decade. He has a performance and recording legacy that includes what one would expect of a

Russian virtuoso: Tchaikovsky, Chopin and, of course, Rachmaninoff. The story of the second concerto is

well-known. After disastrous reviews of his first symphony, the composer fell into a deep depression; he was

unable to compose a note. He had lost confidence.

He worked with a psychotherapist and hypnotist, Dr. Nikolai Dahl, who implanted the idea that his next work

would be a masterpiece. That next work was this evening’s concerto. It was, and is, a masterpiece.

Lugansky is a virtuoso, to be sure, but what was evident in his opening chords was his magnificent tone and

dynamic control. Every sound was perfectly controlled. His piano playing sweeps without the indulgence that

mars so many performances. His range is broad, yet for all his power he never bangs. In the huge climax of

the first movement he seemed to make his piano stand out over the waves of orchestral sound by being not

louder, but more beautiful. The second movement flowed beautifully — his pacing throughout was perfection

— leading without pause into the wild finale. This reviewer has heard faster performances, but none with

such a perfection of sonority and drive. The performance crackled with electricity and the audience leapt to

its feet in one of those rare standing ovations that was fully deserved.

Scheherazade is a wonderful work, with some of the sexiest music ever composed. A great performance is a

rarity — Stokowski’s London Symphony recording has just the right sense of sensuality and Dionysian

frenzy. Alexeev presented a lovely performance, but one that had perhaps too much Apollo, not enough

Dionysus.

St. Petersburg Philharmonic

Palm Beach Daily News • April 7, 2011 page 2 of 2

The performance had the needed great waves of orchestral sound and magnificent orchestral soloists. In

particular, concertmaster Lev Klychkoff, the voice of Scheherazade, was superb — sweet, sensual, seductive,

with enough power to soar over any other sounds, and rock-solid intonation. Bassoon, oboe and flute soloists

were equally fine (though the horn was annoyingly sharp). Their best work was in the third movement, The

Young Prince and the Young Princess, where tenderness was more important than raw passion.

Still, it was wonderful to hear this work in a live performance, even with a few quibbles. The encore, the

Trepak from The Nutcracker, could not have been more perfectly chosen, or executed.

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra

AnnArbor.com • April 3, 2011

Concert Review: St. Petersburg Philharmonic shines at Hill

Auditorium with Rachmaninoff, Rimsky-Korsakov

From the grand Russian school of piano playing, Lugansky managed to be shapely and expressive as well as

dark and regretful. BY SUSAN ISAACS NISBETT

Concerts that keep on giving all the way to the end are a rarity. It’s often downhill after the concerto, or at

least anticlimactic.

But Saturday evening’s Hill Auditorium concert by the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, directed by

Yuri Temirkanov, was good to the very last encore — which, for the record, was the zippy “Trepak” from

Tchaikovsky’s “Nutcracker,” preceded by Elgar’s lovely, singing “Salut d’Amour.”

In fact, this last orchestral concert of the University Musical Society season was everything you could have

hoped for from a Russian-Romantic double bill that included both the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto No. 2,

with the stellar soloist Nikolai Lugansky, and Rimsky-Korsakov’s “Scheherazade.” Throughout the evening

the playing was warm and generous; it touched the heart; but it was never overblown.

The Rachmaninoff and Rimsky were remarkable in many other ways as well. The orchestra addressed the

work’s tidal pulls and deep currents with dark velvet sound; Lugansky’s round tone was its perfect pianistic

match; a slowish first-movement tempo only accentuated the rolling waves.

Throughout the concerto, Lugansky played with tremendous ease. He was equally at home in its virtuosic

passages and in its soulful moments; delicacy suited him as well as hand-blurring bravura. Color abounded in

his sound, and so did rhythmic acuity — the interplay with the orchestra in the final movement was dazzling.

As great as it was to watch Lugansky (and hear him), it was equally fun to watch the Maestro. Is there a

conductor with more eloquent hands than Maestro Temirkanov? He says so much with every gesture, and

even better — the orchestra responds in sound — curling a phrase to a gentle close, evaporating another into

thin air.

In “Scheherazade,” Temirkanov seemed happy breathing the exotic atmosphere of the “Arabian Nights” tales,

a man in love with silks and scimitars and stories and night air scented with roses. The vocal quality of the

playing — especially from concertmaster Lev Klychkov, principal cello Dmitry Khrychev and all the wind

soloists — made the storytelling all the more affecting. The colors were glorious, as they should be, and the

pacing was, well, as spellbinding as Scheherazade’s stories had to be to keep the Sultan rooting for more

tomorrow. A thousand and two nights of playing like this would not be too much.

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra

Chicago Tribune • April 1, 2011

St. Petersburg Orchestra easily scales the peaks BY ALAN G. ARTNER

Visits by the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra and its artistic director, Yuri Temirkanov, long have

brought performances gleaming with color, and so it was again Wednesday night at Orchestra Hall.

Contemporary Russian music was missing from the program, but accounts of standard repertory by Nikolai

Rimsky-Korsakov and Antonin Dvorak were marked by winning freshness, and the modern masterpiece from

Dmitri Shostakovich conveyed a good deal more.

Mstislav Rostropovich was the dedicatee of Shostakovich's First Cello Concerto, and his performances

usually outdistanced those of anyone else. Not on Wednesday. The young American Alisa Weilerstein

showed a deep, dark intensity united to biting drama. If she did not have the master's range of tone and

volume, her sense of repose gave access to a new level of self-communing.

Completely assured in the quiet high writing, Weilerstein shone especially in the long cadenza, with which

she took her time, achieving singular poetry. Twenty years ago, Temirkanov accompanied Natalia Gutman on

one of the work's finest recordings. But that was with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, which the

Petersburg surpassed in atmosphere. On Wednesday the first horn and tympani showed particular command

in creating the thrust also essential to the composer's vision.

The program opened with Rimsky-Korsakov's "Russian Easter" Overture, played luminously but not as a

mere showpiece.

Temirkanov's loving traversal did not smooth over seams in the work's construction. Instead, liturgical

solemnity and celebration both received their due, being wedded only in the last few pages, where the whole

caught fire memorably.

The restraint of Temirkanov's Dvorak Ninth Symphony was a surprise. Everything had measure.

Nobility and rusticity came across with fairly simple directness. Brass playing was not without blemish,

though one relished how the loudest passages blended with the rest of the orchestra, never overpowering.

The single encore was Edward Elgar's "Salut d'Amour," given such fine-toned tenderness that listeners

responded with a satisfied, "Ahh."

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

Chicago Classical Review March 31, 2011

St. Petersburg Phil shows brawny strength and refinement

By LAWRENCE A. JOHNSON

Yuri Temirkanov led the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra Wednesday night at Orchestra Hall.

Few Russian orchestras can boast the kind of storied history and tradition of the St. Petersburg

Philharmonic. Founded in 1882 as the court orchestra to Czar Alexander III, the ensemble premiered

Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique symphony under the composer’s baton, and debuted Prokofiev’s Classical

Symphony as well as many of Shostakovich’s symphonies under his dedicated advocate Evgeny

Mravinsky.

The St. Petersburg Philharmonic came to Chicago Wednesday night as part of its current 19-city U.S

tour under music director Yuri Temirkanov.

If the greater luster and tonal sheen of the Russian National Orchestra has usurped the St. Petersburg

Philharmonic’s long-held place as Russia’s top symphonic ensemble, the Philharmonic can certainly still

hold its own. On Wednesday night, the group gave a fine account of itself displaying the classic

attributes associated with Russian orchestras: a forceful, brawny sonority, imposing, febrile brass and

turn-on-a-dime strings. Woodwinds proved more variable with fitfully wiry oboes, serviceable flutes and

decidedly bland clarinets.

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC

Chicago Classical Voice March 31, 2011

page 2 of 2

The once-popular Russian Easter Overture has fallen out of favor on American programs—not entirely

without reason since this flashy early showpiece by Rimsky-Korsakov has its vulgar moments amid the

heady, incense-laden mix of sacred and profane Russia Orthodoxy.

Temirkanov brought out an uncommon refinement in this music that neatly balanced the fireworks with

notable individual contributions including an eloquent solo by first trombone Maxim Ignatyev and the

sweet-toned violin of concertmaster Lev Klychkov. Yet the orchestra opened up with all due fire and

corporate brilliance in the boisterous final section with some dazzling violin playing by the entire

section at a very fleet tempo.

Alisa Weilerstein made an impressive downtown CSO debut two

years ago at the orchestra’s Dvorak Festival. The American cellist is

clearly a gifted and sensitive musician but I found her account of

Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1 something of a mixed bag.

Weilerstein brought delicacy and a tender, searching quality to the

inward sections of this gaunt and brooding music, notably so in the

ruminative Moderato and the opening pages of the long cadenza. The

cellist rightly sees that extended third-movement solo as the heart of

the concerto, and Weilerstein took it at a very spacious pace. And

while her playing was striking for the degree of dynamic nuance and

confiding expression, at times the soloist’s measured approach flirted

with stasis.

Also in the outer sections, Weilerstein brought all due intensity but didn’t always seem like she had her

fingers completely around the music. There was a fractional hesitation before some big chords in the

opening Allegretto and intonation was not always clean in the heat of the moment. More problematic, in

the straight-ahead bravura of the galumphing finale some of the most virtuosic sections were

underprojected and emerged rather garbled Wednesday night.

Overall Weilerstein’s performance had inspired moments but seems like something of a work in

progress. No complaints about the richly textured accompaniment of Temirkanov and the orchestra with

especially fine contrbutions from first horn Igor Karzov.

It’s good to have a Russian orchestra perform a symphony on tour that isn’t by Tchaikovsky or

Shostakovich. Still, one wishes they had chosen something more daring than Dvorak’s New World

symphony.

That said, Temirkanov led a strongly projected performance that proved somewhat middle-of the road

interpretively. The center of gravity was clearly north and east of Prague wih a notably fleet Scherzo and

a hard-driven finale, thundering timpani to the fore. The Czech composer’s rustic charm was less in

evidence but there were several worthy moments along the way, not least Mikhail Dymsky’s mellifluous

Engish horn solo in the Largo.

The extended ovations by a largely packed hall brought Temirkanov back out for a light and lilting

encore of Elgar’s Salut d’amor.

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

SF Classical Voice March 27, 2011

Temirkanov, Philharmonic at Their Jaw-Dropping Best By JANOS GEREBEN

Judge a lens by the best photo you get. The sharpest, richest picture is what the lens produces; whatever

is inferior is the responsibility of circumstances and, mostly, of "operator error."

Just as I treasure the first picture I ever shot with a Rollei-35, of a 3D-looking water surface beneath a

Hong Kong ferry (the quality of which has never since been duplicated and the little camera lost long

ago) for me the essence of Yuri Temirkanov will always be his conducting and stage direction of the San

Francisco Opera Onegin performances in 1997.

Even after an Onegin-saturated youth in Budapest, those experiences in the War Memorial — six of the

eight performances — were seminal in their authenticity, mastery, combined discipline, and freedom.

How does that "best of" Temirkanov compare with the conductor on the podium at Davies Symphony

Hall Sunday, leading the St. Petersburg Philharmonic?

Mirabile dictu, the moment of truth arrived at the very beginning of the concert, with the downbeat on

Rimsky-Korsakov's Russian Easter Overture. This isn't a figure of speech, just a fact: My jaw dropped.

The gospel hymn of "Let God Arise" and the ecclesiastical theme "An angel wailed" permeated the hall

with a grand, gorgeous sound, with secure brass soaring atop magical and velvety strings — 50 of them

— in perfect unison. It was lush and brilliant, as a basketful of the most elaborate Fabergé eggs. The

whole piece: a new "best of" for Temirkanov.

That's what the Rimsky sounded like

Besides the absolute high value, this calling card also amazed in comparison. Neither at their numerous

San Francisco appearances nor elsewhere when I heard the St. Petersburg live have I had anything like

this experience.

...

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC

SF Classical Voice March 27, 2011

page 2 of 3

It may seem strange to place so much emphasis on the opening overture, but it was truly unforgettable, a

musical bliss, whose surprise kept it sharply etched in memory even as the major portion of the evening

was thoroughly enjoyable.

And major it was, with Shostakovich's Cello Concerto No. 1 and the Brahms Symphony No. 4, both

played exceptionally well. Alisa Weilerstein was the outstanding soloist in the concerto, bravely tackling

a work so completely identified with Mstislav Rostropovich, for whom it was written, and who alone

performed this bravura piece for years after the 1959 premiere.

The orchestra was big and brassy, completely caught up in the obsessive ostinato of the opening march,

which then becomes a leitmotif of the work and a permanent resident in the brain. As in the Rimsky,

strings were wonderful, and the woodwinds and brass were spectacular. And then came the essence of

the concerto, probably the longest and certainly the most dramatic and personal cadenza in all music.

"Obsessive" this time applied to the young cellist, who was so deeply involved in the music, it took her a

few seconds to realize that while she lasted through the cadenza, the instrument didn't — a string broke.

Weilerstein stopped playing, looked around in confusion, then stood up and walked off the stage. All of

five minutes before the end of the piece. The audience laughed and applauded, unable — naturally, but

unfortunately enough — to sustain the deeply sad and desperately passionate atmosphere created by the

music (or what could be heard of it through a persistent storm of coughs, mostly reserved for the quietest

passages). After a few minutes of waiting, Temirkanov too left the stage, and eventually the two

returned, and finished the concerto, to tremendous applause.

Were this to happen in a violin concerto (and with a more experienced soloist), the concertmaster would

have passed over his or her own instrument, and the music would have continued. But no matter: Soloist

and orchestra performed a great, difficult work splendidly.

What is the oldest Russian orchestra doing playing Brahms? Unlike the snafu with Mahler, Temirkanov

and the Philharmonic performed the work superbly. No Germanic precision here, but heartwarming

Russian romanticism — a perfectly acceptable, even welcome, substitution.

The opening Allegro non troppo was big and just a bit noisy, the Andante moderato sang passionately

(more Tchaikovsky than Brahms proper), and then the Allegro giocoso really brought it all home, big,

pleasantly raucous, and altogether joyful. The orchestra raced through powerfully the virtual

afterthought of the fourth movement.

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC

SF Classical Voice March 27, 2011

page 3 of 3

Through it all, Temirkanov conducted in his usual unshowy, simple and effective manner, focusing on

the music and the players, not dancing for the audience. (Not that there is anything wrong with Gustavo

Dudamel, and the like — it's just a matter of style and personality.)

The encore was the "Nimrod" episode from Elgar's Enigma Variations, played the same way the concert

began: thrilling, overwhelming.

This orchestra, not so incidentally, is truly and historically part of Temirkanov's life and career. From

1938 until his death in 1988, the legendary Russian conductor Evgeny Mravinsky headed what was then

the Leningrad Philharmonic, Temirkanov serving as his assistant and also the head of the Kirov, for

which the Philharmonic has always served as the court, later house, orchestra.

At the Kirov, Temirkanov hired a 24-year-old assistant by the name of Valery Gergiev. Somehow —

and that's a long, complex story — in 1988, Gergiev became music director of the Kirov, and

Temirkanov took over the Philharmonic after Mravinsky's death.

Through thick and thin, a great deal of both in the post-Soviet country, Temirkanov stayed with the

orchestra, although in recent years, Gergiev — both at the Kirov and in concerts — often headed it.

Temirkanov's association with the musicians for more than three decades is really paying off these days.

If you missed the Sunday concert, there is still one to come Monday night — be sure to look it up here.

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

Los Angeles Times March 23, 2011

Music review: St. Petersburg Philharmonic begins U.S. tour with

Alisa Weilerstein

By MARK SWED

The St. Petersburg Philharmonic was founded in 1882 and proudly identifies itself as the oldest Russian

orchestra. It is also no doubt the most Russian orchestra. On Tuesday night it launched a 26-day U.S.

tour at Walt Disney Concert Hall with an all-Russian Rimsky-Korsakov, Shostakovich and Brahms

program. No, I didn’t know Brahms was Russian either. More about that later.

When the St. Petersburg Philharmonic last performed at Disney in 2007 under artistic director Yuri

Temirkanov, the group stood out for being somewhat older on average than is typical these days and for

the relatively few women players. Not much has changed. But, then, the orchestra knows a thing or two

about tradition.

From 1938 until his death in 1988, the legendary Russian conductor Evgeny Mravinsky headed the

orchestra, then called the Leningrad Philharmonic. Temirkanov, once an assistant conductor to

Mravinsky, succeeded him. That’s two music directors in almost three-quarters of a century!

Perhaps it is that kind of collective memory that provides these St. Petersburgers with the confidence

for individual expression. Concertmaster Lev Klychkov has a lion’s mane of long, graying hair and has a

soloist’s commanding tone. As if possessed, a percussionist in Rimsky’s “Russian Easter Festival”

crashed together his cymbals with enough force to crush a skull. An oboist waved his instrument in the

air as he played like a jazz musician in search of a spotlight.

The overall character of the performance was that of a hybernating orchestra awakening after a cold,

dark winter, one musician at a time. Rimsky provides many rosy solos and they were all blushingly

singular, be they mellow or crude. Temirkanov is a micromanaging conductor but also one with a flair

for sweeping dramatic gestures that seemed here designed to tell stories.

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC

LA Times March 23, 2011

page 2 of 2

Under Mravinsky, the St. Petersburg was practically Shostakovich’s house band. It premiered several of

his symphonies as it did his First Cello Concerto in 1960 with Mstislav Rostropovich as soloist. Alisa

Weilerstein was on hand to play the concerto Tuesday.

As an American, young and a woman, she might have been expected to have had three strikes against

her facing this team of heavyweights in heavyweight music that they own. Moreover, this is an orchestra

that can get a little surly with outsiders, as it did on its last visit to Disney when the Brazilian pianist

Nelson Freire was soloist.

But in the intense Weilerstein, the players met their match. She tore into the concerto with a ferocity

that all but left the orchestra stunned. She is not undisciplined. She projected a rich lyrical tone when she

wanted to or when Shostakovich wanted her to, and she played as if lost in reverie. But she was most in

her element when on the percussive attack.

Temirkanov conducted with detached bemusement. He let her rip. To make the supposedly expressive,

mellow cello shine, Shostakovich left out all the brass except for a single horn. Temirkanov let the horn

rip too, as if to see what would happen. Neither the hard-bearing horn nor the orchestra scrambling to

keep up with Weilerstein could withstand her impressive assaults on her cello.

At intermission I heard what seemed like half the audience humming the opening march motif, so

effectively did she drill it into our heads (I’m still humming as I type).

Brahms’ Fourth Symphony after intermission was extraordinary. Temirkanov sought out a Russian soul

that the German composer could not have known he had. The phrasing was flexible, with strings in the

first movement sighing Slavic sighs. Reedy, ripe woodwinds in the Andante might well have been

playing saturnine Tchaikovsky, with the horns and brass snarling in the background. A flute solo in the

Finale was an Onegin in the ravages of self-pity, as the movement, based on a Baroque chaconne

structure, inexorably brandished fate’s will.

The encore was the “Nimrod” movement, opaque and expansive, from Elgar’s very British “Enigma”

Variations. This time it was “Nimrodsky,” someone joked.

Summer 2007

For Immediate Release

St.Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra Announces U.S. Tour for Fall 2007

Temirkanov to Lead Concerts in Over a Dozen Cities from Coast to Coast

Guest Artists to Include Julia Fischer and Nelson Freire

The St.Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra, one of the world’s greatest exponents of the Russian symphonic

tradition, will conduct a month-long tour of 20 cities throughout the United States in the fall of 2007. In repertoire

ranging fromMozart and BeethoventoProkofievandMussorgsky,the superb 110-member ensemble will perform seven

different programs to be distributed throughout the tour in 23 concerts, starting at the Kennedy Center in Washington,D.C. on October 23

rd, and concluding with Benaroya Hall in Seattle on November 20

th. The St.Petersburg

Philharmonic’s U.S. tour is sponsored by Opus 3 Artists (formerly ICM Artists). Of the 23 concerts on the tour,

seventeen will be led by the Orchestra’s Artistic Director and Principal Conductor, Yuri Temirkanov, and six will be under the direction of Nikolai Alexeev, the Orchestra’s Associate Conductor. All but three of the programs on the tour

will feature a guest artist: German violinist Julia Fischer will join the Orchestra in performances of the Beethoven

Violin Concerto in D Major, Op.61, and on other evenings Brazilian pianist Nelson Freire will befeatured in

Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor, Op.54. The Orchestra will also present a rare performance of Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky, Op.78 in New York at Carnegie Hall, where the ensemble will be joined by the Dessoff Choirs, the

Russian Chamber Chorus of New York, and dazzling mezzo-soprano Larissa Diadkova. For a complete listing of

all concert programs see St.Petersburg Philharmonic Programs, attached.

Other highlights of the St.Petersburg Philharmonic’s 2007-08 season include the prestigious ArtsSquare Festival in

St.Petersburg in December, a tour of the European Union in Spring 2008 and a tour of Latin America in Summer 2008.

In recent seasons the Orchestra has conducted substantial tours throughout Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Spain, the United Kingdom, the U.S., South America, and Japan. In the summer of 2006, the Orchestra performed at Peterhof

Palace for the Summit of the Group of Eight. The St.Petersburg Philharmonic makes regular appearances at the most

prominent summer festivals - the Salzburg, Lucerne, BBC Proms, Helsinki, MDR, Rheingau, and Edinburgh Festivals

among them. The ensemble’s Royal Gala performance in London in 2002 prompted The Guardian to call the Philharmonic “probably the greatest orchestra in the world.” The group’s performances in the U.S. under the direction

of Yuri Temirkanov (a tour every 3 years, on average) consistently generate a torrent of accolades. On the occasion of

the Orchestra’s last U.S. visit in 2004, the ensemble’s playing was characterized as “Voluptuous, seductive” (New York Times), “breathtaking” (San Francisco Chronicle), and “simply profound” (Baltimore Sun).

For more information about the U.S. tour dates, the St.Petersburg Philharmonic, Yuri Temirkanov, Nikolai Alexeev

and guest artists, see attached document and call 831-620-1332.

St.Petersburg Philharmonic U.S. Dates in Fall 2007

23 Oct 07 Washington, D.C. Temirkanov/Fischer Mozart; Beethoven; Prokofiev

25 Oct 07 Newport, VA Temirkanov/Fischer Mozart; Beethoven; Prokofiev

26 Oct 07 Chapel Hill, NC Temirkanov/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra

Press Release

page 2 of 2

28 Oct 07 Newark, NJ Temirkanov/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

30 Oct 07 New York, NY Temirkanov/Fischer Mozart; Beethoven; Prokofiev

31 Oct 07 New York, NY Temirkanov/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

01 Nov 07 New York, NY Temirkanov/DiadkovaSviridov; Mussorgsky; Prokofiev

02 Nov 07 Purchase, NY Alexeev/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

03 Nov 07 Greenvale, NY Temirkanov/Fischer Mozart; Beethoven; Prokofiev

04 Nov 07 Ann Arbor, MI Temirkanov/Fischer Mozart; Beethoven; Prokofiev

06 Nov 07 Chicago, IL Temirkanov/Fischer Mozart; Beethoven; Prokofiev

07 Nov 07 Urbana, IL Temirkanov/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

08 Nov 07 Iowa City, IA Alexeev/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

09 Nov 07 Lincoln, NE Alexeev/Fischer Mozart; Beethoven; Prokofiev

10 Nov 07 Overland Park, KS Alexeev Prokofiev

12 Nov 07 La Jolla, CA Temirkanov/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

13 Nov 07 Santa Barbara, CA Alexeev/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

14 Nov 07 Costa Mesa, CA Temirkanov Prokofiev

15 Nov 07 Los Angeles, CA Temirkanov/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

17 Nov 07 Davis, CA Alexeev Prokofiev

18 Nov 07 San Francisco, CA Temirkanov/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

19 Nov 07 San Francisco, CA Temirkanov/Fischer Mozart; Beethoven; Prokofiev

20 Nov 07 Seattle, WA Temirkanov/Freire Schubert; Schumann; Prokofiev

N E W Y O R K • L O S A N G E L E S • L O N D O N

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

Chicago Sun-Times November 12, 2004

Russians put special stamp on favorites

By WYNNE DELACOMA

There's an odd sense of homecoming whenever the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra stops by

Symphony Center, as it did Wednesday night during a current U.S. tour.

The venerable orchestra isn't an especially frequent visitor; the most recent call was paid two seasons

ago. But Chicago is home to a large Russian community filled with music lovers who turn out to hear

performers or ensembles from their native country. Comfortable with the rituals of classical concerts,

they fill Symphony Center's lobbies with animated Russian conversation at intermission.

Some of that feeling of homecoming, however, resides purely in the music. Russian composers

including Prokofiev, Shostakovich and Tchaikovsky, whose music the orchestra performed on

Wednesday, belong to classical music's pantheon. Their life stories and music are as familiar as those of

Brahms or Beethoven. A distinctly Russian stamp pervades their music, however. Hearing it played by

an orchestra that was the premiere ensemble in Russia's most important city during their own lifetimes is

like returning to some mystical, inspirational source.

Yuri Temirkanov, the ensemble's music director and principal conductor since 1988, and his players

wore their mystical connections with appropriate lightness in Prokofiev's Symphony No. 1 ("Classical''),

Shostakovich's Cello Concerto No. 1 with soloist Lynn Harrell and Tchaikovsky's Symphony No 6

("Pathetique'').

Prokofiev's effervescent little symphony, only 15 minutes long, functioned like an hors d'oeuvre to the

heavier fare to come, a musical morsel bursting with flavor and playfully elegant.

With Shostakovich's cello concerto, written in 1959 for the composer's close friend, Mstislav

Rostropovich, the evening shifted to much darker emotional territory. In this work, along with

Tchaikovsky's introspective "Pathetique,'' the musicians' affinity for their compatriots' music was

evident in the restraint they brought to it.

Neither orchestra nor conductor saw any need to exaggerate Shostakovich's grimly jaunty marches or the

concerto's stretches of heart-breaking loneliness. The composer's world was in their bones, and it

surfaced naturally like a disorienting fog or a glaringly bright light. With Harrell's raw, singing line

always in their sights, they were equal partners in a gripping performance. At times hysterically driven,

at others wandering slowly across a vast, icy vista, soloist and orchestra took us to the far edges of

Shostakovich's frightening world.

As an encore, the orchestra gave a nobly tender performance of the Nimrod variation from Elgar's

"Enigma'' Variations

N E W Y O R K • L O S A N G E L E S • L O N D O N

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

Palm Beach Post November 07, 2004

Russians display clean, light touch

By SHARON MCDANIEL

Playing to its considerable strengths, the St. Petersburg (formerly the Leningrad) Philharmonic

Orchestra opened the Regional Arts series Friday afternoon with the first of two all-Russian programs at

the Kravis Center. And in his return to South Florida, Yuri Temirkanov, the Russians' music director of

16 years, again proved to be one of the most inspiring and eloquent conductors in the field.

Friday's program featured renowned American cellist Lynn Harrell in Shostakovich's Cello Concerto

No. 1 in E-flat, sandwiched between two orchestral standards: Prokofiev's Symphony No. 1 ("Classical")

and Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 6 ("Pathtique"). But little was standard about the program's

performances or the two encores.

Harrell comes closest to highlighting the cello's human vocal quality. He even phrases the melodies as if

imitating a singer's breath patterns. And like a vocalist, he changes timbre and color to best express the

music's sentiments.

He engaged the music - and the listener - so intensely that the Shostakovich emerged as more of a play

about the drama and constancy of human striving than an instance of simply gorgeous, incisive playing.

Whether Harrell's soliloquies waxed soulful and sorrowful, distraught or defiant, restive or reflective,

Temirkanov backed him up with brilliant effects and beautifully finished lines. The combination was

electric, building one of the best conceptualizations of the work.

Harrell treated the enthusiastic audience to the first encore: a solo transcription of Chopin's Nocturne in

E-flat, Op. 9, No. 2. With remarkable subtlety and freshness, he replicated the feathery filigree originally

written for piano, but with a lightness of touch, yet depth of feeling, that few pianists achieve in the

familiar slow waltz melody.

Temirkanov, with the same rhythmic drive that powered the Shostakovich, heightened the aerodynamics

in Prokofiev's Classical and the urgency in Tchaikovsky's Pathtique. Although Tchaikovsky's off-beat

"waltz" (second movement) drifted and sank into redundancy, the explosive first and exultant third

movements let the celebrated Russian brass players reign triumphant.

French hornist Andrei Gloukhov, among other wind soloists, cradled the listener in the melancholy and

yearning.

The Prokofiev, like the Shostakovich concerto, stuttered a bit when players weren't unanimous about the

rhythms. But mostly, the Classical symphony was exuberance in flight and a rare model of a large

orchestra playing delicately, cleanly and with far more clarity than it mustered in its 2002 Kravis

concert.

Mostly, the praise belongs to Temirkanov, so perceptive in his attention to fleeting nuances and details

as well as the overall picture.

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC

Palm Beach Post November 7, 2004

page 2 of 2

After the fifth curtain call, he led as an encore the type of music he definitely excels in: the emotive,

expansive "Nimrod" from Elgar's Enigma Variations. Conducting as usual without a baton, he molded,

stroked and caressed the sound with his hands for a transcendent, powerful musical experience.

N E W Y O R K • L O S A N G E L E S • L O N D O N

ST. PETERSBURG PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

South Florida Sun-Sentinel November 4, 2004

A truly memorable night with Repin

and famed Russian orchestra

By LAWRENCE A. JOHNSON

With the Jackie Gleason Theater in Miami Beach festooned with American and Russian flags on

election eve, conductor Yuri Temirkanov and the St. Petersburg Philharmonic Orchestra opened the

Concert Association of Florida's season with rich and majestic performances of both countries' national

anthems. It made for a serendipitous ode to democracy at a time of national political ferment.

No other Russian ensemble and few orchestras in the world boast the storied history and distinguished

musical traditions of the St. Petersburg Philharmonic. Created in 1882 by a decree of Czar Alexander,

the Philharmonic was honed to a sharp ensemble edge and gleaming muscle under the 50-year tenure of

legendary conductor Evgeny Mravinsky.

Under its current artistic director and principal conductor Temirkanov, the orchestra remains an

instrument of remarkable firepower, virtuosity and polished precision. The corporate sound is largely

consistent: dark burnished strings that turn on a dime, heaven-storming brass and athletic woodwinds. A

single horn blooper almost came as a relief: The Russian musicians were human after all.

Prokofiev's Classical Symphony was listed as Monday's curtain raiser, but was replaced without

comment by four excerpts from the composer's anarchic opera The Love for Three Oranges.

Temirkanov drew a full-metal performance that underlined the clangorous brass riffs and biting sarcasm.

The popular March was punched across with a weight and aggressive impact that made the subversive

element unmistakable.

The fact that Vadim Repin opted to perform Prokofiev's Violin Concerto No. 1 rather than the flashier

Second Concerto is testament to the Siberian violinist's artistic integrity. Though not without its

virtuosic moments, the First Concerto is a more subdued interior piece, with a dreamlike introspection

alternating with bursts of bravura.

From the pastel pianissimos of the opening statement, Repin conveyed the withdrawn romantic essence