Spontaneous Return of Function Following Surgical Section of ...

Transcript of Spontaneous Return of Function Following Surgical Section of ...

ANNALS OF SURGERY

Vol. 146 November 1957 No. 5

Spontaneous Return of Function Following Surgical Sectionor Excision of the Seventh Cranial Nerve in the

Surgery of Parotid Tumors *

HAYES MARTIN, M.D.,** JAMES T. HELSPER, M.D.jNew York, New York

From the Head and Neck Service of Memorial Hospital

THE PURPOSE of this report is to presentclinical evidence that following surgicalsection and sacrifice of a considerable seg-ment of the seventh cranial nerve (includ-ing a portion of its main trunk and theperipheral plexus) there can be spontane-ous recovery of function in a fair percent-age of cases without resort to nerve graft-ing or any other form of neurorrhaphy.The clinical basis for the report is an

analysis of a consecutive series of 150 op-erative cases of malignant tumors of theparotid from the Head and Neck Serviceof the Memorial Hospital during the period1949 to 1953 inclusive. Incident to the sur-gical removal of the tumors, 40 (27 percent) of these patients had a deliberate sec-tion of the seventh cranial nerve and anexcision of a segment of between 2.5 and5 cm. of the main trunk of the nerve and itsperipherally extending branches (plexus).Of the 40 patients with such sacrifice of

* Submitted for publication April 22, 1957.** Attending Surgeon, Memorial Hospital.+ Resident Surgeon, Memorial Hospital.

the nerve, 28 were considered to be de-terminate (statistically significant). The re-maining 12 indeterminate patients (all withcancer of the parotid) either had rapid andmassive local recurrences with gross inva-sion of the facial musculature, or sufferedgeneralized dissemination of cancer. Noneof the latter 12 patients lived long enoughso that it could be established whetherthere would otherwise have been any re-turn of function eventually, this being thereason for classifying them as indeterminate.The noteworthy observation which we

wish to place on record in this report is thatof the 28 determinate cases at least eightpatients (28.5 per cent) had a fair degreeof return of function in the paralyzed facialmusculature without resort to nerve graft-ing or any other reparative operation.

Review of the Literature on SeventhCranial Nerve Neurorrhaphy

We have been unable to find any previ-ous report of recognized spontaneous re-covery of function following segmental op-

715

716 MARTIN AND HELSPER

erative defects of the seventh cranial nervein adults. Conley 5 mentions having ob-served it in two children, but apparentlyhas not recognized its possibility in adults,for he reports elaborate combinations ofnerve grafting and muscle and/or fascialtransplants to relieve the sequelae of suchsegmental defects. As we shall later dis-cuss in more detail, we strongly suspectthat spontaneous recovery has actually beenobserved by others (though not recognizedas such), especially in most of the reportedcases where a return of function has beenascribed to some form of neurorrhaphy.

In any event, a search of the literaturefor documentary evidence of functional re-covery following neurorrhaphy in specificcases is disappointing, especially as regardsnerve injuries incident to parotid surgery.In most reports on the treatment of facialnerve paralysis, the discussion is concernedmainly with the sequelae of mastoid sur-gery and skull fracture or with the reliefof Bell's palsy. In the present report, we areconcerned only with actual segmental op-erative defects (2.5 to 5 cm. in length) ofthe seventh nerve and its plexus incident toparotid surgery, and, therefore, henceforthfor purposes of brevity and clarity, we shallnarrow our discussion to that aspect of theproblem.For the repair of peripheral segmental

defects of the seventh nerve, three generalmethods have been used: 1) single orbranched, fresh or degenerated auto graftshave been sutured and anastomosed, end-to-end, to bridge the defect; 2) nerve graftshave been anastomosed to the proximalstump only of the seventh nerve with theirbranched distal ends laid loosely in tunnelsin the facial musculature; 3) the distal por-tion of the seventh nerve has been trans-planted and anastomosed with the centralstump of a sectioned 11th cranial nerve.The published reports of results of all

these forms of nerve grafting are ratherscanty and, in most instances, either nega-tive or so vague as to be unconvincing. In

Annals of SurgeryNovember 1957

1932, Ballance and Duel 2 reported twocases of unbranched nerve grafts suturedend-to-end to bridge defects in the maintrunk of a seventh nerve in parotid tumorcases. No end results are given, and theauthors' only comment in this regard isthat "good" or "perfect recovery is ex-pected." In any case, so far as we are con-cerned, segmental defects of the seventhnerve incident to parotid surgery are char-acteristically rather extensive (2.5 to 5 cm.or even more) and, therefore, must includenot only a portion of the main trunk butalso a part of the plexus. And for this rea-son, we cannot see any practical applicationin parotid surgery of unbranched graftssuch as those used by Ballance and Duel.While several other authors, Fursten-

berg,8 Lathrop,9' 10 Bunnell,3 and Ballance,'discuss the placement of unbranched graftsin the bony facial canal, there is little or nofollow up, or at least no documentary evi-dence of recovery. Ballance simply statesthat in one such case recovery was "wonder-fully satisfactory."A fairly clear and well-documented in-

stance of functional recovery is that pub-lished by Cardwell,4 who in 1938 reporteda staged nerve graft following a radical ex-cision of the parotid in which several seg-ments of the external femoral (a sensorynerve) were sutured to the proximal stumpof the facial nerve and the distal ends ofthe grafts laid in tunnels in the facial mus-culature. He states that after one year therewas "voluntary and emotional response inthe lower two-thirds of the face and goodclosure of the eye." We find it difficult toaccept unquestionably this single and iso-lated case of functional recovery as beingthe specific result of neurorrhaphy. It seemshardly likely to us that in the period of ayear there could have been such accuratere-establishment of neural pathways be-tween the facial nerve nucleus and the mo-tor end plates in each of its several appro-priate groups of facial muscles by way ofthese multiple grafts, the distal ends of

Volume 146 SURGERY OF PNumber 5

which had been laid "loosely in tunnels inthe facial musculature" so as to permit of"voluntary and emotional response" and"good closure of the eye."

Maxwell,13 in 1954, reports one case offacial nerve grafting (branched) in a seg-mental defect following parotid surgery. Areturn of function was first noted 19 monthsafter the original sacrifice (ten months afterthe graft). Is it not reasonable to conjecturethat the results in both of these precedingcases actually were due to spontaneousrecovery?Conley 5 reports seven instances of facial

nerve neurorrhaphy combined with mas-seter muscle rotation and/or fascia lata sus-pension after parotid surgery. He usedbranched grafts from the great auricularnerve (sensory), the anastomoses (aboutfour in number) with the terminal compo-nents of the seventh nerve plexus being se-cured by plastic tube cylinders. He reportssatisfactory results (65 to 95 per cent) inthree cases. From the standpoint of criticalevaluation, however, it is not possible tojudge the merits of neurorrhaphy alonefrom the latter cases, since a combined pro-cedure (neurorrhaphy and muscle or fasciatransplant) was used in all. The pattern ofrecovery, including the time interval inboth Maxwell's and Conley's, however, issimilar to our spontaneous cases.According to the literature, the trans-

plantation of the distal portion of theseventh nerve into the sectioned stump ofthe eleventh cranial has proved completelyunsuccessful.* Duel and Ballance,7 Sul-livan,14 and Lathrop 9 all deprecate its use-fulness. Love and Cannon 11 mention its

'AlROTID TUMORS 717

use only after removal of tumors of theacoustic nerve. They give no follow up. Inany case, this maneuver could only be ap-plied in cases where the peripheral portionof the seventh nerve (and plexus) con-sisted of the main trunk of the facial nerve,a condition not present after radical resec-tion of the parotid.

In brief, although nerve grafting for fa-cial nerve defects distal to the bony canalhas been employed for over 25 years, fewclear-cut successful results have been re-ported, and even in these the phenomenonof spontaneous recovery would be a fairlyreasonable explanation. As recently as 1953,Lathrop,9 reporting the experiences at theLahey Clinic, pessimistically concludes that"under such circumstances (i.e., defects in-cident to parotid surgery) the facial paraly-sis must be alleviated by other means"(than neurorrhaphy).We think it significant that in a single

clinic we have observed more instances ofspontaneous recovery (eight) in a seriesof 28 determinate cases of wide segmentaldefects of the peripheral portion of theseventh cranial nerve than the total of alldocumented cases reported in the literaturefollowing neurorrhaphy. Since the attemptat neurorrhaphy would in no way hinderspontaneous recovery, we strongly suspectthat most (if not all from reported cases)are actually of spontaneous character.

Anatomic and Clinical Considerationsof Surgical Trauma to the Seventh

Cranial Nerve

The surgical anatomy of the seventh cra-nial nerve, after it emerges from the stylo-

* One of us (H. M.) has observed 2 cases inwhich the 11th nerve had been anastomosed withthe terminal 7th. In one (a mastoid case) the fail-ure of functional return was obvious and had beenaccepted as such by the patient. In the second (theresult of a gunshot accident), the patient had beenassured by his neurosurgeon that recovery had be-gun. Eight years later the patient appeared tohave perfect confidence that such was the case,and (following the directions of the neurosurgeon)

he would attempt to demonstrate this by a com-bined convulsive elevation of the shoulder withan exaggerated and bizarre grimace of the wholeface, an act which he fondly believed to provethat there was recovery in the paralyzed side ofthe face. While the grotesque gesture was surelyarresting to the casual observer, it was, neverthe-less, completely useless, for so far as could be seenthere was no active motion whatever on the par-alyzed side of the face.

MARTIN AND HELSPER Annals of SurgeryNovember 1957

Stump of

F&~ci I N.

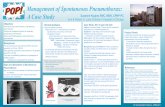

FIG. 1. The dotted lines represent the average portion of the 7th nerve (main trunk and plexus)which was removed in the cases reported in this paper.

mastoid foramen to enter the substance ofthe parotid gland and then to divide andsubdivide after a variegated pattern (Fig.1), renders any deep surgical explorationof this region somewhat hazardous fromthe standpoint of serious accidental trauma(crushing, over-stretching, or complete sec-

tion) to the seventh nerve and its plexus.Only by an intimate knowledge of its localsurgical anatomy, and by preliminary ex-

posure of the main trunk of the nerve, can

the likelihood of these accidental hazardsbe eliminated.The parotid has a rather indistinct cap-

sule, and in this highly vascular field it issometimes troublesome to distinguish pa-

rotid tissue from subcutaneous fat. Exceptby first directly exposing the main trunk ofthe nerve,'2 it is difficult or even impossiblesubsequently to expose, identify, and pre-serve all portions of the plexus. Parotid

tumors often appear deceptively superficialto the surgeon who lacks experience in thisparticular area, and as the result of the sev-

eral foregoing considerations many ill-con-ceived, incomplete, or unnecessarily trau-matic operations are performed in cases ofparotid tumors. When such operations are

performed (that is, without preliminary ex-

posure of the main branch of the nerve),many seventh nerve disabilities of uncer-

tain character occur. Under such circum-stances with partial or complete postop-erative paralysis the discomfitted surgeoncannot know whether he has completelysectioned the main trunk of the nerve, or

one of its branches, crushed the nerve, or

whether he has simply over-stretched it.Since the disability is unsightly and mighteven have medico-legal significance, it isunderstandably of considerable concern tothe surgeon.

718

Volume 146Number 5

SURGERY OF PAROTID TUMORS 719

TABLE I. Patients Showing Return of Function Following Resection of a Segment of the7th Nerve for Parotid Tumor

MinimumLength of FirstResected Return of

Case Segment FunctionNo. Patient Age Sex (cm.) Diagnosis (Mo.)

1 N. W. 28 F 3 Mucoepidermoid 8carcinoma

2 L. R. 16 F 4 Adenocarcinoma 63 R. F. 63 M 5 Epidermoid 6

carcinoma4 J. A. 37 M 3 Recurrent mixed 10

tumor5 M. P. 26 F 2.5 Mucoepidermoid 8

carcinoma6 J. K. 48 M 2.5 Mucoepidermoid 21

carcinoma7 J. W. 61 F 2.5 Fibrosarcoma 138 J. S. 60 M 4 Alveolar 35

carcinoma

If then after a few weeks or severalmonths there is a substantial degree of re-covery from the paralysis, the surgeongratefully breathes a sigh of relief and notunreasonably concludes that the degree ofsurgical trauma was less than complete sec-tion. While under such circumstances therecovery is most likely to be due to a re-establishment of the neural pathway througha physically intact though traumatized nervethat has been over-stretched or crushed,nevertheless, according to our observations,such a recovery could also take place afterseveral months following complete sectionof the nerve (or the removal of a segment)and not necessarily by a regrowth throughold channels.

In brief, should there be a functional dis-ability of the seventh cranial nerve (eitherpartial or complete) after a parotid opera-tion, the actual physical status (section orlesser trauma) of the nerve cannot beknown unless during the operation themain trunk and part of the plexus has beenclearly exposed and identified, and theneither deliberately sacrificed or its continu-ity carefully preserved. It is for this reason

that we limit our observation to those casesin which there has been a clear exposureand identification of the main trunk of thenerve and then its deliberate section andthe removal of a wide segment (2.5 to 5cm.) of the main trunk and its peripheralplexus.

Report of Cases and ClinicalObservations

In Table 1 there is given a brief resumeof the eight cases of spontaneous recoveryforming the basis of this report. The pa-tients, ranging in age from 16 to 63 years,were all operated upon during a five-yearperiod, 1949 to 1953 inclusive. As is theroutine in our clinic, the main trunk of theseventh nerve had been exposed as a pre-liminary step of the operation. In all in-stances the decision to section the maintrunk and to sacrifice the nerve was thenmade only after it had been clearly demon-strated that the tumor was not resectablewithout such sacrifice. Accordingly, a seg-ment of the main trunk of the nerve andof its adjacent plexus was removed with the

720 MARTIN A

tumor and a portion of the parotid gland.The lengths of the resected segmentsranged from 2.5 to 5 cm. No attempt wasmade in any of these (nor in any of thegrand total of 40 cases) to resuture or tograft. To relieve the more serious aspectsof the resultant orbicularis oculi paralysis,a fusion of the eyelids was routinely madeon the affected side at the completion ofthe main operation. There was immediateand complete postoperative paralysis of thecorresponding facial musculature in all ofthe cases, and, since the surgeon had nohope of a return of function, no physio-therapy (Faradic stimulation) was given.

Spontaneous Recovery of Function. Inthe eight cases of spontaneous recovery, thepatients themselves were invariably the firstto discover and announce to their respec-tive surgeons that some active motion hadreturned.

N. W., aged 28, the first case observed by us,was a singer by profession (Case 1, see Table).At her operation in June, 1950, for a twice-recur-rent parotid tumor, the main trunk of the nervewas found to be completely encompassed by thegrowth and for this reason was deliberately sec-tioned and about 3.0 cm. of the nerve and a por-tion of its distal plexus were resected along withthe tumor. A fusion of the homolateral eyelids wasmade. Postoperatively there was complete paralysisof the corresponding side of the face.

At one of her regular follow up visits about8 months later, the patient announced to her sur-geon (H. M.) that she could move slightly theparalyzed side of her face. As she sat in the ex-amining chair, her efforts to demonstrate this mo-tion were thought to be inconclusive, the disbeliefbeing based in large part on the examiner's rea-sonable even though erroneous conviction thatsuch return of motion was impossible from theanatomic standpoint. On her next visit a monthlater, she again insisted that active motion waspresent and that it had increased. At that time hersurgeon and one of his associates were forced toconcede that some active motion was actually pres-ent in the form of a slight voluntary retraction ofthe right commisure of the mouth. From that timeonward there was a slow but steady improvementduring a period of 21,2 years, and at the presentwriting, over 5 years later, there is active motionin all parts of the once completely paralyzed facial

LND HELSPER Annals of SurgeryNovember 1957

_Mmp- V...:T. -----

FIG. 2A (Above). FIG 3A (Below). See oppositepage for legend.

musculature, including a definite wrinkling of theright forehead (frontalis), so that she can raisethe eyebrow several millimeters. There is a definiteactivity of the orbicularis and wrinkling of the sideof the cheek and nose. She can now draw back theright commisure of the mouth for a distance ofover 2 cm. All these different motions are as highlyselective as in the normal side of the face (Figs.2 and 3).

As is common with complete (unilateral) facialparalysis, this patient had trained herself to main-

SURGERY OF PAROTID TUMORS

FIGs. 2 and 3. Fig. 2B (Above). Fig. 3B(Below). (Case 1, N. W.) Letters A refer to theposition of the labial commissures and eyebrowswith the face in repose. Letters B refer to the partsof the face on purposeful active motion. Thephotographs are aouble exposures and the dia-grams are self explanatory.

tain the normal side of the face in relatively com-

plete repose and to avoid as much as possibleany movement which might tend to emphasize thedisparity between the 2 sides of the face. Toachieve the effect of a "dead pan" countenance,considerable practice in front of a mirror is re-

quired. From the beginning this patient had re-

fused to take her surgeon's word that no recoverywas possible. She was unimpressed by what we

considered anatomic and surgical "facts," and shenever lost faith and the determination that some-

how she could achieve voluntary motion, an exam-

ple of the power of faith sometimes to accomplishthe seemingly impossible. The degree of recovery

in this case has been progressive. She is active andconfident in her social contacts.

The sequences of events in subsequentcases have been similar. The first evidenceof motion in all has been the ability to pull

back voluntarily the angle of the mouth, a

motion which can result from the action ofsome or all the following facial muscles:risorius, buccinator, quadratus labii supe-

riorus and inferiorus, canine, and triangu-laris. Once initiated, there is invariably a

steady improvement in the degree of re-

covery, the voluntary motion becomingmore pronounced and extending selectivelyto the muscles of the lower lip, cheek, and,finally, to the orbicularis oculi and frontalis.Once voluntary motion returns to any partof the face it is almost as selective in thelocal area as on the normal side of the face.The droop of the angle of the mouth, so

characteristic of seventh nerve paralysis,completely disappears. On forcible or ex-

aggerated motion there remains some dis-parity between the two sides of the face,but in repose and with ordinary facial mo-

tion the difference is so slight as to be un-

objectionable. We have reason to believethat such recovery of motion is favored andhastened if the patient actively and con-

sistently (daily) practices in front of themirror.

The interval between the operation andthe first sign of recovery was six and eightmonths (two cases each) and, in each ofthe others, 10, 13, 21, and 35 months. Oneof the deterrents and handicaps in the de-tection and observations of this phenom-enon is, at first, the natural disbelief of thesurgeon who, having resected a segment ofthe facial nerve, cannot bring himself atfirst to accept the patient's claim of volun-tary motion. In brief, since such recoveryis thought to be impossible, there may seem

Volume 146Number 5 721

722 MARTIN A

to be little point in making careful observa-tions. During the early years of our ob-servations we noted such an attitude ofamused and tolerant disbelief on the part

of most of our colleagues and of visitorswhen we first reported and discussed thisphenomenon at the Head and Neck Con-ferences at Memorial Hospital.

Explanations of the Phenomenon

From the purely theoretical standpointthere might seem to be several possible ex-

planations for a return of function follow-ing complete section with a loss of sub-stance of the seventh cranial nerve. Afterconsideration of these, it is our opinion thatthe most reasonable explanation is that newmotor pathways are established throughthe fifth cranial nerve. We shall elaborateon this theory in a subsequent section afterfirst discussing other explanations whichwe consider less tenable.

Spontaneous Regrowth of Seventh Cra-nial Motor Nerve Fibers Across a Defectof Several Centimeters. In our cases therewas an unbridged defect of between 2.5and 5 cm., and if one postulated that a

regrowth of nerve fibers took place across

this defect, one would also have to concedethat in some manner the advancing nerve

fibers must have sought out and joined upwith a number (at least four or five) ofwidely separated stumps of the distal plexusand, in addition, that this complex re-anas-

tomosis was effected in such an exact man-

ner as to permit of selective action in thevarious facial muscles.

If regrowth across the operative field andre-anastomosis were responsible for the re-

turn of function (through the remainingseventh cranial nerve structures) then a re-

excision of the parotid area for recurrence

would obviously interrupt such neural path-ways, and whatever active motion had beenre-established would immediately be lost.On the contrary, in two of our cases inwhich considerable function had returned,

LND HELSPER Annals of SurgeryNovember 1957

a second excision of the local area only tem-porarily interfered with such function ashad been re-established following the firstoperation. These facts are briefly stated inthe following paragraphs.

M. P., aged 26 (Case 5, see Table 1), was firstseen in our clinic in 1947 with a postoperative re-current tumor in the right parotid area. A diagno-sis of "mucoepidermoid carcinoma" had been madeon a submitted slide. When first seen in our clinicthere was no seventh nerve disability. She wasoperated upon for the second time in 1947, atwhich time the main trunk of the nerve was ex-posed, preserved intact, and the recurrent tumorexcised. Following this operation there was onlytemporary disability of the seventh nerve. Thegrowth recurred 3 years later, and a 3rd operationwas performed in June, 1950, at which time themain trunk of the nerve was again exposed, butwas found so intimately associated with the growththat a segment consisting of the main trunk of thenerve and 2.5 cm. of its peripheral plexus was re-sected along with the tumor. Postoperatively therewas complete paralysis of the corresponding sideof the face. Eight months later (February, 1951),a definite beginning return of voluntary motionwas first noted (spontaneous recovery). Improve-ment continued steadily, so that about a year laterthere was practically a complete return of func-tion. She was then followed free of disease forabout 4 years (until January, 1955), when a 3rdrecurrence was noted. In January 1955, a 4th op-eration was made, at which time a wide local exci-sion was again made which included an area ofskin between 4 and 5 cm. in diameter, and allof the underlying tissue in the parotid area, in-cluding the masseter muscle and posterior belly ofthe digastric. A skin graft was applied, a portionof which lay on the periosteum of the mandible.For the first few days there appeared to be ap-parent complete paralysis, although there was somedifference of opinion among the surgeons who ob-served her. The patient, herself, however, thoughtshe could move the face slightly. A month laterthere was definite motion about the mouth andcheek, and within 2 months the function had re-turned to the same degree which was present be-fore the 4th operation.

L. R., aged 16 (Case 2, see Table 1), had beenoperated upon elsewhere for a parotid tumor inOctober 1951, following which there was tem-porary paralysis of the nerve and subsequent com-plete recovery. A year later there was a recurrencewhich had been locally excised.

SURGERY OF PAROTID TUMORS

She was first seen in our clinic in April 1953,at which time there was a bulky recurrence underthe scar in the left parotid area. In April 1953, oneof us (H. M.) made a radical resection of the re-currence, including a total excision of the parotid.At that time the main trunk of the 7th nerve wasexposed and a section made just at its emergencefrom the stylomastoid foramen. Following this op-eration, there was complete loss of active motionin the corresponding side of the face. In October(6 months later) there was a beginning return offunction that continued to improve in degree un-

til February 1954.The patient lived at a distance and did not

return for observation until July 1954, at whichtime a 3rd recurrence was noted in the parotidarea, apparently lying mainly in the retromandibu-lar area. She was again operated upon, and at thistime the retromandibular area was entered througha surgical exposure of at least 6 cm. in its verticalextent and the recurrent tumor widely removed.Briefly, whatever regrowth or anastomosis mighthave occurred in the defect of the 7th nerve, thelatter operation must have completely interrupted it.

Within a period of 2 weeks postoperatively,however, it was noted that the same degree ofactive motion (present before the last operation)was again noted in the left side of the face. The

patient returned to her home some distance fromNew York and was not again observed. We sub-sequently learned that local recurrence and generaldissemination of the disease took place and thepatient died several months later.

In two of our cases of spontaneous re-

covery (Cases 2 and 5, see Table 1), thepatients with a fair degree of spontaneousrecovery of function after segmental de-fects of the seventh nerve were again op-

erated upon for recurrence and a wide anddeep portion of tissue removed from theparotid area, which obviously must haveincluded any possible regrowth and directbridging of the defect of the seventh nerve.

The latter operations did not disturb thefunctional recovery. In our opinion theseobservations clearly negate the theory thatthe spontaneous recovery of function was

due to regrowth of seventh nerve fibersacross the defect.

Decussation and/or Anastomosis Acrossthe Midline of the Face. The existence of

neural motor pathways crossing the midlineof the face from the opposite side has beenpostulated from observations on the slightmotions of the frontales and the orbicularisoris muscles on the paralyzed side in casesof unilateral seventh nerve paralysis. Amore reasonable explanation for the latterphenomenon is that the motion of one sidewould naturally tend to cross to the op-posite side due to the interlacement ofmuscle fibers of the muscles in the mid-line. In any case, if such a cross innervationwere responsible for the recovery in ourcases, the action could hardly be volun-tarily selective to a localized group of mus-cles without activating both sides.

Establishment of New Motor PathwaysThrough the Fifth Cranial Nerve

According to standard anatomical texts,the main trunk of the fifth cranial nerve ismade up of two components: a motor anda sensory division respectively. The motorcomponent is usually alleged to be separateand to pass entirely into the third division(mandibular nerve) and then into threemain branches: 1) the masticator nerve(motor and sensory), 2) the lingual nerve(sensory), 3) the inferior alveolar nerve(sensory). The other two branches of thefifth cranial nerve (the ophthalmic and themaxillary nerves) are thought to be whollysensory.

Communications or Anastomoses of theTerminal Branches of the Fifth CranialNerve with the Terminal Branches of theSeventh Cranial Nerve. A reference to thedetailed anatomy of the fifth and seventhcranial nerves reveals what, in our opinion,is a highly significant fact, namely, thatthere are elaborate anastomoses (plexuses)between the terminal branches of the fifthand seventh cranial nerves in all parts ofthe facial musculature from the foreheadto the lower lip (Fig. 4). Beginning fromabove, they are briefly outlined as follows:

Volume 146Number 5 723

MARTIN AND HELSPER Annals of SurgeryNovember 1957

FiG. 4. Anastomoses (plexuses) of the terminal branches of the5th and 7th cranial nerves.

1. The auriculo-temporal branch (V Cr.)communicates within the parotid glandwith branches of the facial nerve (VII Cr.).

2. The infratrochlear branch of the oph-thalmic nerve (V Cr.) communicates withthe zygomatic branches of the facial nerve

(VII Cr.).3. The zygomatico-facial branches of the

maxillary nerve (V Cr.) communicate withthe zygomatico-facial branches of the facialnerve (VII Cr.).

4. The zygomatico-temporal branches ofthe maxillary nerve (V Cr.) communicate

with the temporal branches of the facialnerve (VII Cr.).

5. The infraorbital branch of the maxil-lary nerve (V Cr.) communicates with thezygomatic branches of the facial nerve

(VII Cr.) and then rises to form the infra-orbital plexus.

6. The masticator branch of the man-

dibular nerve (V Cr.) communicates at theangle of the mouth with the plexus of thefacial nerve (VII Cr.).

From the afore-mentioned (possibly in-complete) listing, it will be seen that there

724

SURGERY OF PAROTID TUMORS

are at least six plexuses made up of com-

munications of terminal branches of thefifth and seventh cranial nerves which are

definite enough to be recorded by anatom-ists. So far as we know, the function ofthese plexuses has never been definitelyestablished, but it is reasonable to suppose

that they could hardly be present withoutsome purpose or potential function possiblyhaving to do with emotional expressionshared by both nerves. Such terminal com-

munications must obviously include, or atleast be closely associated with the motorend plates, and to us it seems reasonableto conjecture that following complete andpermanent interruption of the motor path-way through the seventh cranial nerve,

voluntary motor impulses by re-educationmay find their way from the cortex throughthe fifth cranial nerve to the respectivemuscles.What at first may seem to be merely an

additional minor anatomical detail may ac-

tually also have considerable significance.The masticator nerve (fifth cranial) isknown to contain both motor and sensoryfibers. Its buccinator branch (which accord-ing to Cunningham 6 iS only sensory) per-forates the buccinator muscle before sup-plying sensation to the skin and mucous

membranes of the cheek. The significantquestion is whether or not the latter sup-

posedly only sensory nerve might also carrysome dormant motor fibers which are givenoff as the nerve pierces the buccinator mus-

cle. If such were the case, there would bea reasonable explanation for the fact thatin our eight cases a voluntary drawing backof the angle of the mouth (by buccinatorcontraction?) has invariably been the firstsign of recovery.*

* A similar uncertainty as to the possibility ofan associated motor function in a predominantlysensory nerve existed for many years as regardsthe superior laryngeal nerve whose actual functionin the complicated act of swallowing has not as

yet been clearly established.

Resume and Conclusions

Although at first there may be some re-

luctance to accept the theory that the newmotor pathways may be established by wayof the fifth cranial nerve, it seems to us,

nevertheless, to be one of the most reason-

able explanations for the uncontestable factthat functional recovery has actually beenobserved by us in eight cases despite seg-mental defects of several centimeters ofthe main trunk and plexus of the seventhcranial nerve, and that such recovery is notdisturbed by complete re-excision of theparotid area through which all theoreticalregrowth from the resected seventh nerve

must have passed.The pattern in all of our cases has been

rather uniform; that is, in general begin-ning about six to 14 months after sacrificeof a segment of the seventh cranial nerve,

there has occurred a slight voluntary re-

traction of the angle of the mouth, pro-

gressively increasing in extent, the motionfinally extending to all parts of the facewith a selective action in the various por-

tions of the facial musculature at the willof the patient finally permitting an inter-play of action of these muscles so as to pro-

duce a variety of emotional responses char-acteristic of normal movement.As the result of our observation on the

frequency of spontaneous recovery (what-ever its actual explanation), we questionthe justification for any form of neuror-

rhaphy or extensive plastic repair (excepteyelid fusion) for seventh cranial nerve

paralysis due to operative defects until atleast a year or more has passed. We submit,furthermore, that in view of the fact thatspontaneous recovery has taken place inover one-fourth of our cases, there is con-

siderable doubt that any of the few re-

coveries, as reported in the literature, fol-lowing neurorrhaphy, are actually due tothat cause.

Volume 146Number 5 725

726 MARTIN AND HELSPER Annals of Surgery

SummaryEight cases of spontaneous recovery of

seventh nerve function following segmentaloperative defects of the seventh cranialnerve are reported. These cases make up28.5 per cent of 28 determinate cases oc-curring in the five-year period 1949 to 1951.Various explanations for this phenomenonare discussed, and the opinion given thatthe motor pathways to the facial muscula-ture are re-established by way of the fifthcranial nerve.

Addendum

Since the completion of the statistical analysisin August 1956, we have noted beginning recoveryof function in 2 additional cases. But to includethese 2 patients in the body of the main textwould require a reworking and analysis of thestatistical accounting of 3 additional years of pa-rotid surgery, which would delay the publication.Actually we have noted a return of function in atotal of 10 cases to date.

References1. Ballance, C.: The Operative Treatment of

Facial Palsy with Observations on the Pre-pared Nerve-graft and on Facial Spasm.Proc. Roy. Soc. Med., 27:1367, 1934.

2. Ballance, C. and A. B. Duel: The OperativeTreatment of Facial Palsy by the Introduc-tion of Nerve Grafts into the Fallopian Canaland by Other Intratemporal Methods. Arch.Otolaryng., 15:1, 1932.

3. Bunnell, S.: Suture of the Facial Nerve withinthe Temporal Bone with a Report of theFirst Successful Case. Surg., Gynec. & Obst.,45:7, 1927.

4. Cardwell, E. P.: Direct Implantation of FreeNerve Grafts Between Facial Musculatureand Facial Trunk; First Case to be Reported.Arch. Otolaryng., 27:469, 1938.

5. Conley, J. J.: Facial Nerve Grafting in Treat-ment of Parotid Gland Tumors. A. M. A.Arch. Surg., 70:359, 1955.

6. Cunningham's Text-Book of Anatomy. FifthEdition. William Wood and Company, NewYork, 1921.

7. Duel, A. B.: Clinical Experience and SurgicalTreatment of Facial Palsy by AutoplasticNerve Grafts: The Ballance-Duel Method.Arch. Otolaryng., 16:767, 1932.

8. Furstenberg, A. C.: Reconstruction of theFacial Nerve. Arch. Otolaryng., 41:42, 1945.

9. Lathrop, F. D.: Management of TraumaticLesions of the Facial Nerve. A. M. A. Arch.Otolaryng., 55:410, 1952.

10. Lathrop, F. D.: The Facial Nerve: Techniqueof Exposure and Repair. Surg. Clin. of NorthAmerica, 33:909, 1953.

11. Love, J. G. and B. W. Cannon: Nerve Anasto-mosis in the Treatment of Facial Paralysis:Special Consideration of the Etiologic Roleof Total Removal of Tumors of the AcousticNerve. A. M. A. Arch. Surg., 62:379, 1951.

12. Martin, H.: The Operative Removal of Tu-mors of the Parotid Salivary Gland. Surgery,31:670, 1952.

13. Maxwell, J. H.: Repair of the Facial Nerveafter Facial Lacerations. Tr. Am. Acad.Ophth. & Otolaryng., 58:733, 1954.

14. Sullivan, J. A.: Recent Advances in the Sur-gical Treatment of Facial Paralysis and Bell'sPalsy. Laryngoscope, 62:449, 1952.

Additional References

The authors are surgeons, not neuroanatomistsnor neurophysiologists, but they submit the bib-liography below, which includes considerable back-ground for this article.

1. Beahrs, 0. H. and B. F. L'Esperance: TheFacial Nerve in Parotid Surgery. J. A. M. A.,162:261, 1956.

2. Berry, Charles: Personal communications.3. Bunnell, S.: Surgical Repair of the Facial

Nerve. Arch. Otolaryng., 25:235, 1937.4. Collier, J.: Facial Paralysis and Its Operative

Treatment. Lancet, 2:91, 1940.5. Duel, A. B.: History and Development of the

Surgical Treatment of Facial Palsy. Surg.,Gynec. & Obst., 56:382, 1933.

6. Foote, F. W., Jr. and E. L. Frazell: Tumors ofthe Major Salivary Glands. Cancer, 6:1065,1953.

7. Frazell, E. L.: Clinical Aspects of Tumors ofthe Major Salivary Glands. Cancer, 7:637,1954.

8. Haymaker, W. and B. Woodhall: PeripheralNerve Injuries. W. B. Saunders Company,Philadelphia, 1945.

9. Lyons, W. R. and B. Woodhall: Atlas ofPeripheral Nerve Injuries. W. B. SaundersCompany, Philadelphia, 1949.

10. Mackay, R. P., S. B. Wortis, P. Bailey and 0.Sugar, Editors: The Year Book of Neurology,Psychiatry and Neurosurgery (1955-1956Year Book Series). The Year Book Publish-ers, Inc., Chicago, 1956.

Volume 146 SURGERY OF PAROTID TUMORS 727Number 5

11. Maxwell, J. H.: Extra-temporal Repair of theFacial Nerve; Case Reports. Ann. Otol.,Rhin. & Laryng., 60:1114, 1951.

12. Myers, D.: War Injuries to the Mastoid andthe Facial Nerve. Arch. Otolaryng., 44:392,1946.

13. Platt, H.: On the Results of Bridging Gaps inInjured Nerve Trunks by Autogenous FascialTubilization and Autogenous Nerve Grafts.Brit. J. Surg., 7:384, 1920.

14. Pollock, L. J. and L. Davis: Peripheral NerveInjuries. Paul B. Hoeber, Inc., New York,1933.

15. Pollock, L. J., J. G. Goldseth, F. Mayfield, A.J. Arieff, E. Liebert and Y. T. Oester: Spon-taneous Regeneration of Severed Nerves.J. A. M. A., 134:330, 1947.

16. Ramon y Cajal, S.: Degeneration and Re-generation of the Nervous System. OxfordUniversity Press, London, 1928.

17. Sperry, R. W.: The Problem of Central Nerv-ous Reorganization after Nerve Regenerationand Muscle Transposition. The Quarterly Re-view of Biology, 4:311, 1945.

18. Weiss, Paul: Personal communications.

5k