Sondheim piano sonata analysis

-

Upload

da-bomshiz -

Category

Documents

-

view

313 -

download

8

Transcript of Sondheim piano sonata analysis

Sondheim's Piano SonataAuthor(s): Steve SwayneSource: Journal of the Royal Musical Association, Vol. 127, No. 2 (2002), pp. 258-304Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. on behalf of the Royal Musical AssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3840465 .

Accessed: 03/11/2013 23:37

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

.

Royal Musical Association and Taylor & Francis, Ltd. are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve andextend access to Journal of the Royal Musical Association.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journai ofthe Royal Musical Association, 127 (2002) ? Royal Musical Association

Sondheim's Piano Sonata

STEVE SWAYNE

In the autumn of 1949, Stephen Sondheim enrolled in Music 103, the

first semester of the two-semester senior honours course in music at

Williams College (in northwestern Massachusetts). There were no

specific requirements for the course, according to the college prospec- tus for that year, other than regular consultation with the supervisor for music honours. In essence, Sondheim began a programme of inde?

pendent study with Robert Barrow, then the principal composition teacher at Williams who had been promoted to full professor that year.1 The 1956-7 college prospectus contains the first mention of the

requirements for the degree with Honors in Music. Barrow was chair

of the Music Department at the time.

In the senior year history candidates must submit a thesis; theory candi- dates a composition in one of the larger forms or a group of smaller works. In both cases the first semester of senior year is spent in preparation of the

writing of the thesis or composition, under supervision of one or more members of the department, meeting twice weekly. The work of the second semester consists largely of the actual writing of the thesis or composition.2

Seven years before these guidelines were issued, Sondheim elected to

write for Barrow a composition in three of the larger forms: a piano sonata that uses sonata, extended ternary and rondo forms in its com?

pleted movements.

The continuity between Sondheim's early musical vocabulary and his

mature musicals emerges more clearly in the light of the sonata.

Written when the winds of international musical fashion were begin?

ning to favour the Second Viennese School, the sonata generously

employs the vocabulary of Paul Hindemith, a composer whose influ?

ence on American composers has yet to be fully charted. What one

unexpectedly discovers from the sonata is not only how proficient Sondheim was in this vocabulary: one also discovers hitherto unsus-

pected concordances between the sonata, Sondheim's mature works, and the sound world and compositional aesthetics associated with Hindemith. Familiarity with Sondheim's sonata changes the way

I thank Stephen Sondheim for making his Williams College student reports available to me. I thank Linda Hall, archives assistant at Williams College, for her inestimable help in researching

1 Sondheim went on to enrol in Music 104 in spring semester 1950, completing Music 103, Music 104 and the Honors programme in Music successfully. Information about Robert Bar row in this article comes from papers and press releases contained in the Robert George Barrow file of the Williams College archives.

2 Williams College Bulletin (March 1956), 146.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sondheim's piano sonata 259

scholars and musicians, classical and popular alike, must talk about the

music of Sondheim's maturity and enriches our discussion of musical

America in the middle of the twentieth century.

THE HISTORY OF THE SONATA (AND MUSIC AT WILLIAMS)

The scope of Sondheim's accomplishment is best understood in the

context of the emergence of the Department of Music at Williams.

Before 1927, Williams offered no academic courses in music. That year, the Department of the History of Art and Civilization (renamed the

Department of Fine Arts in 1930) offered the sole music course in the

Williams curriculum, a two-semester 'History and Appreciation of

Music'. The prospectuses give the impression that this was a stolid work-

list approach to the Great Men of Music: Semester I went from Pal-

estrina to Bach, Semester II from Bach to 'the present day'. In fact, the

description of the Fine Arts major, with its one music course, seems to

go out of its way to exclude serious mention of music:

The primary objective is to provide a sequence of courses which will

acquaint the student with the culture of the East and the West as it is

expressed and as it may be evaluated in terms of the fine arts throughout the course of civilization. The introductory course emphasizes the prin? ciples which form the basis for design and expression in the arts. The major is planned as a further analysis of these principles and as an introduction to the fundamental problems of art history and criticism through the study of significant achievements in architecture, sculpture, and painting.3

In the autumn of 1939, the 28-year-old Barrow arrived at Williams. He

had earned three degrees from Yale - BA (1932), B.Mus. (1933), Mus.M. (1934) - and was the recipient of the Ditson Fellowship for

Foreign Study in 1934. The award enabled him to study conducting with Sir Henry Wood and composition with 'the distinguished com?

posers Ralph Vaughan Williams and Paul Hindemith'. After his return

to the USA, he worked for four years as organist and director of the

choir school ofthe National Cathedral (Episcopal) in Washington, DC, before moving to Williamstown. Barrow's hands-on experience with

choral and organ music and his exposure to continental culture would

be matched the following year when Joaquin Nin-Culmell, a concert

pianist who studied at the Paris Conservatoire, joined the faculty. Barrow rose rapidly from assistant to full professor

- he held the rank

of associate professor for four years - in part because of his ambition

and in part because of the college's needs. In 1940, the Fine Arts

department was renamed Fine Arts and Music. That same year, the

course offerings in music grew sevenfold to five regular two-semester

courses and two year-long honours courses for juniors and seniors

offered by permission of instructor. Seven years later, the department was renamed again, from Fine Arts and Music to Art and Music. Finally,

3 This description appeared in the Williams College Bulletin from 1937 to 1946, with the exception of 1943 and 1944.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

260 STEVE SWAYNE

TABLE1

MUSIC THESES AT WILLIAMS COLLEGE, 1943-60

year author/composer title/composition length

1943 Charles Gorham Phillips The Jazz-Age Isolationists' 108 pp. (text) 1946 Edwin Stube Slow Movement for Organ 4 pp. (112 bars)a 1950 Stephen Sondheim Piano Sonata in C major, 1st 13+16 pp. (176 + 171 bars);

and 3rd movements 2nd-movement sketch (2 pp., 32 bars) catalogued in 2001

1951 William Farrar Wynn A Movement in Sonata Form 13 pp. (222 bars)a 1952 John Phillips Seven Pieces for Piano 5 + 3 + 3 + 4 + 3 + 3 + 4 pp.

(84 + 34 + 72 + 73 + 44 + 52 + 67 bars)a

1953 Alexander C. Post Sonata for Organ, 1st 13 pp. (194 bars)a movement

1954 John T. Overbeck 'The Bagatelle and Beethoven' 89 pp. (text) 1955 Donald Robert Munroe Two Three-Part Inventions 3 + 3 pp. (24 +36 bars)a

Paterson for Piano 1957 Robert Kelton Goss Two Three-Part Inventions 3 + 4 pp. (30 + 62 bars)a

for Pianoforte 1957 David Gregg Niven Two Three-Part Inventions 3 + 4 pp. (35 + 57 bars)a

for Pianoforte 1958 Ridgway M. Banks Sonata Form Movement for 17 pp. (96 bars)

Clarinet and Piano 1960 J. Edward Brash *

Regina by Marc Blitzstein: 51 pp. (text) An Approach to American Opera'

1960 Robert J. Stern Rondo-Sonata for String 11 pp. (184 bars) Quartet

a The author wishes to thank Ben Isecke of Williams College for his help in determining the total bar counts of these works.

by 1950 - the year Sondheim graduated - the Music Department was

completely separate from the Art Department. (In comparison, Yale

University appointed its first music instructor in 1855 and had elevated

music to the level of an academic subject by 1890.)4 The faculty and administration might have had the Music Depart?

ment on an even faster track but for the intervention of World War II.

In the 1943-4 and 1944-5 prospectuses we read: There will be no Fine

Arts and Music majors for the duration because of the limited course

offerings under war conditions/5 As a result the senior theses in music

during the 1940s are small in number and scattered. Sondheim's

sonata, in fact, was only the third senior thesis in music produced at

Williams, so there were few established departmental guidelines and

fewer precedents for him to follow at the time.

How exceptional was Sondheim's decision to write a sonata becomes

somewhat clearer when we look at the theses that followed Sondheim's

(see Table 1). On either side ofthe 1956-7 departmental guidelines, as many honours students chose to write a

* composition in one of the

4 See Allen Forte, 'Paul Hindemith's Contribution to Music Theory in the United States', Hindemithjahrbuch, 27 (1998), 62-79 (pp. 69-70).

5 Williams College Bulletin (December 1943), 94; (December 1944), 51.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sondheim's piano sonata 261

larger forms' as opted to compose 'a group of smaller works'. But with

only one composition thesis preceding his own - Edwin Stube's rela-

tively short G minor organ voluntary - Sondheim's decision to write a

three-movement piano sonata was ambitious and idealistic. Perhaps his

struggle to complete the work is reflected in the more modest honours

compositions that were written after his own.

Beyond Sondheim's compositional difficulties lay practical ones as

well: he could not play the sonata. While his chosen instrument was the

piano, by the time he reached Williams he had abandoned whatever

aspirations he may have had to become a virtuoso.6 His preferred venue for performance at Williams was the theatre; he wrote shows for

the Adams Memorial Theatre and appeared in non-musical plays

during his years there.7 The technically demanding sonata lay beyond his considerable abilities.8 Certainly either Barrow or Nin-Culmell

could have premiered the sonata, had Sondheim set his sights on a

performance beyond whatever passable account he himself could give for anyone who would listen.

Sondheim, however, did not have performance in mind. Nor did he

seem to see beyond the narrow confines of the assignment at hand.

Unlike nearly all the other students whose composition theses are listed

in Table 1, he worked on music paper rather than reproducible vellum

and submitted his manuscript (presumably his only copy) to the

college. A piano sonata - a genre with two centuries of history and a

host of associations adhering to it - gave Sondheim an opportunity to

show his skill in controlling his musical language over a long expanse of time without the benefit of words. In many respects, and in contrast

to the musicals he composed and eagerly performed at Williams, the

sonata was more of an academic musical exercise than an expressive artistic pronouncement.

The mystery surrounding the sonata's second movement can also

lead to a cursory view of the entire work. Until November 2000, the

Williams College archives had only the first and third movements of

Sondheim's sonata in its collection. When in September 2000 I asked

Sondheim about the missing second movement, he responded by

sending a two-page sketch for it with instructions that it be shared with

the Williams archives. (That sketch, marked 'unfinished', is now on file

at the archives.) In a separate letter, Sondheim stated: T can't find the

6 Sondheim: 'I liked playing the piano part of the first movement of the Rachmaninoff C minor [concerto, op. 18], which I played in high school, toured, and gave recitals in Pennsyl? vania.' He also played Chopin's Polonaise-Fantasy and Ravel's Valses nobles et sentimentales, the latter 'entirely for my own pleasure'. Personal correspondence, 20 November 2001.

7 Not until the 1967-8 Bulletin did the following appear: 'It is expected that music majors will participate in at least one department sponsored performance group during their junior and senior years' (p. 153). New York Yankees owner George Steinbrenner may reminisce about singing with Sondheim in the Williams College Glee Club, but Sondheim declares that he never sang in the Glee Club, nor was he required to participate in any organized music ensemble while he was a music major at Williams.

8 Sondheim: 'As for the Piano Sonata ... it's never been performed. And of course I knew how difficult it was -1 was writing theoretically rather than practically.' Personal correspondence, 19 January 2001.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

262 STEVE SWAYNE

complete second movement, even though I'm almost certain I finished

it -1 doubt Bob Barrow would have let me get away with an incomplete thesis.' But Linda Hall, archives assistant at Williams College, assever-

ated that there is no record of the archives' having received the second

movement and that it is unlikely that it has been misfiled or lost.9

Even without a second movement, Sondheim's thesis dwarfs nearly all the others in its immediate vicinity in extent and scope. The other

theory students may have expanded their single movements into multi-

movement works at a later time; in their cases, one sonata movement

apparently satisfied Barrow. In contrast, Sondheim produced at least

two and maybe all three movements while he was a senior, with all the

pressures every graduand knows - and then some. (In his last year he

was composing what would have been his third Williams musical - High

Tor - but the project had to be abandoned when Maxwell Anderson

would not give Sondheim permission to adapt his play.) And where one

of the completed movements rather slavishly adheres to sonata form, another charts its course with almost reckless abandon.

The sonata continues to occupy a shadowy netherworld in Sond?

heim's biography and creative persona. It has never been performed in public. It is not scheduled for publication. It is never discussed as an

influential work. It may be close to being forgotten. However, with the

recent premiere of another early instrumental work - the Concertino

for Two Pianos, orchestrated for chamber orchestra with piano obbli-

gato by Jonathan Sheffer10 - it is time to reassess the sonata for what it

reveals about Sondheim's development as a composer.

THE MANUSCRIPT OF THE SONATA

The physical manuscript exhibits numerous fascinating features. For

example, the two outer movements are separately bound, a curious

decision that may be explained in part by the omission (and expec- tation?) of the second movement. The bindings themselves differ in a

number of small details that, when taken together, suggest that the two

movements may have been bound at different times and by different

individuals.

One can also see that Sondheim took greater care in planning and

writing the third movement than the first. The manuscript of the first

movement consists of five four-page folios, with each folio consisting of

a front page, interior verso and recto pages, and a rear page. One folio

serves as a wrapper; Sondheim used die front page as a tide page and

enclosed within this folio the remaining four folios. (He has continued

9 Personal correspondence with Sondheim, 19 January 2001, and with Linda Hall, 2 February 2001.

10 See my review of the composition and Sheffer's arrangement, 'The Concertino: When the Music Got Lost', Sondheim Review, 8/1 (summer 2001), 33. In his programme notes Sheffer mistak- enly identified the Concertino as Sondheim's senior thesis. More recently (12 April 2002), the presenter of a US National Public Radio broadcast introduced a recording of Sheffer's perform? ance with the statement that 'when [Sondheim] was in college, he wrote a sonata for two pianos as his senior thesis'.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sondheim's piano SONATA 263

to use the folio-as-wrapper method of organizing his manuscripts.) The

movement itself is written from folio to folio, giving the manuscript the

following layout:

folio 1 - wrapper: tide page on front page; empty interior verso page

folio 2-pp. 1-4 ofMS

folio 3-pp. 5-8ofMS

folio 4-pp. 9-12 ofMS

folio 5 - p. 13 of MS on front page; all other pages empty

folio 1 - wrapper: empty interior recto and rear pages

This arrangement of consecutive foliation results in six blank manu?

script pages, a relatively inefficient use of paper for a 13-page manu?

script with a title page. Another indication within the manuscript itself further suggests that

the transcription of the first movement from sketch to fair copy was not

completely plotted out in advance. On page 3 a piece of paper has been

pasted over the first system. The differences between the original

manuscript and the palimpsest are shown in Table 2.

Comparison of these features of the first-movement manuscript with

those found in the third movement reveals that in the latter, rather than using consecutive foliation, Sondheim interleaved his folios in the

following manner (page numbers correspond to front, interior verso, interior recto, and rear pages of each folio):

folio 1 - pp. 1, 2, 15 and 16 of MS

folio 2 - pp. 3, 4, 13 and 14 of MS

folio 3 - pp. 5, 6, 11 and 12 of MS

folio 4-pp. 7-10 ofMS

This manner of foliation allowed the binder to staple the folios

together at the centre (i.e. between pages 8 and 9), whereas the

arrangement of the folios in the first movement required that the

binder sew the folios together along the edges of the gathered folios. An unusual feature in the foliation of the third movement is found on

page 9 ofthe manuscript, where Sondheim used three staves to a system while maintaining an empty staff after each system, with the result that

there are only three systems on this page instead of the typical four.

Nowhere later in the manuscript does Sondheim appear to have tried

to make up for this lost system by squeezing in extra bars - in fact, the

final page has only three systems of regular grand staff writing on it.

Another interesting aspect of this movement is that Sondheim uses two

different types of manuscript paper. Folios 1 and 2 are from The Music

House (an establishment in the neighbouring town of North Adams); the paper for folios 3 and 4 was made for 'G. Schirmer' and is slighdy smaller and a litde more yellowed than the Music House paper. Where the first-movement manuscript is a model of waste, the third is a model of efficiency.

The two-page sketch of the second movement stands apart from the

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

264 STEVE SWAYNE

TABLE2

SONDHEIM, PIANO SONATA IN C MAJOR, FIRST MOVEMENT COMPARISON OF MANUSCRIPT AND PALIMPSEST

MSp. 3, first system (bar no.)

first bar (28) second bar (29)

third bar (palimpsest only) (30)

subsequent bar (31)

original manuscript

identical in both versions 3/4 bar: beat 1 identical in both versions; beats 2 and 3 identical with 2/4 bar in palimpsest

identical in both versions

palimpsest

3/4 bar: new material for beats 2 and 3

2/4 bar: identical with beats 2 and 3 of second bar in original

completed movements in a variety of ways.11 Although both pages are

written on the same Music House paper on which most of the sonata

appears, the layout is unusual. The folios from the Music House have

distinctive footers on the front page and the interior recto but not on

the interior verso or rear pages. The first page of the sketch has no

footer, thus making it either an interior verso or a rear page. It is also

clearly marked, like the companion first pages of the two completed movements, with a roman numeral indicating which movement this is.

The second page is written on the front page of a folio that is turned

upside down. Given that an opened and inverted folio would put the

front page on the left-hand side of a two-page layout, the two pages of

the sketch are written either on opposite sides of the same piece of

paper (i.e. interior verso and front) or on two different pieces of manu?

script paper. In either case, the sketch was provisional, as other factors

demonstrate.

The manuscript is written in pencil rather than pen, and the musical

and expressive details that fill the completed movements - dynamics,

phrase and pedal markings, time-signature changes - are almost non-

existent here. In a few instances, the absence of time-signature changes leads to confusion as to how to realize the sketch: did Sondheim mean

to move from 3/4 to 6/4, or are the notes supposed to be semiquavers rather than quavers? And the sketch breaks off mid-idea in this

predominandy 3/4 sketch with a hovering authentic cadence within an

unmarked 7/8 bar that has no closing barline - a fitting caesura for this

enigmatic movement (Example l).12

11 This description of the sketch is based on an observation ofa photocopy of the sketch and corroboration from Sondheim.

12 I acknowledge the cooperation of the copyright-holder in allowing me to quote, here and in Examples 3-6, 8, 10, 11, 13-18, 20-7, 29-31 and 33, from the piano sonata by Stephen Sondheim. Copyright ? (renewed) by Rilting Music, Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SONDHEIM S PIANO SONATA 265

Example 1. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, second movement, bar 32.

Example 2. Suspended dominant chords.

G7sus4 F/G Dmin7/G

THE MUSIC OF THE SONATA

The 7/8 bar also serves as a useful introduction to the musical language that Sondheim used in the sonata. While there are gestures to tradition

throughout - cadential motion, sequential patterns, primary and

secondary materials - Sondheim employed them within a decidedly

contemporary musical language. Unadorned triads are difficult to find

in the sonata, appearing most noticeably (and almost as non sequiturs) at the close of the completed movements. Ninth, eleventh and thir-

teenth chords abound. The dominant chord in particular often takes

on a specific colouration. In lead-sheet parlance and with C as tonic, Sondheim tended to use G7sus4, F/G and Dm7/G chords for the domi?

nant function in the sonata. Example 2 shows these three chords next

to one another, with a fourth chord showing how they can also be

derived from rearranging superimposed fourths, a device that will

become important in the third movement. The 7/8 bar also has a pre-

ponderance of flats, including a double flat; in this it is representative of the sonata as a whole, which has no double sharps but has an abun?

dance of flats and double flats along with naturals (cautionary and

necessary) to cancel them out.

Table 3 provides an overview of the first movement. A cursory glance at the number of bars in each main division of the movement shows that the development section is the largest of the three. The table does

not reveal another factor that makes the development still lengthier than the other sections. The base metre for the movement is 4/4. The

development has a greater proportion of bars that are metrically larger than 4/4, and the other sections have a greater proportion of bars that

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TABLE 3 g 0>

SONDHEIM, PIANO SONATA IN C MAJOR, FIRST MOVEMENT

(numbers are those of bars; * = in inversion; d = in diminution)

exposition (1-61) development (62-128) recapitulation and coda (129-76)

first-theme group (1-30) 1-11: 1st theme (= motif) in varied

guises (aand a1) 12-18: heraldic triplet idea (T) that

slackens

19-22: agitated transitional material derived from a; notable for

arpeggios at end of each bar 23-4: a6- in cadential 6-4 position 25-6: cascade of figuration derived

from a 27-30: furioso dissonant passage; a* in

accompaniment; slackens at end to lead to:

second-theme group (31-61) 31-8: 2nd theme (in A minor), 1st

statement (b)

39-48: 2nd theme, 2nd statement

(developed); leads to climax (47-8)

(47-8): ascending tetrachord

first-theme group (129-52) 129-39:: 1-11

140-3 (1st beat) :: 12-15 (1st beat); voicing of the final chord different between 2 versions

143-5: quieter reflection on material from 19-22

[no cognate for 23-4] 146-7:: 25-6

148-52: reiteration and transposition of

27-30; builds at end to lead to:

second-theme group (153-69) 153-60: similar to 31-8; at same pitch

level (i.e. no transposition), but now in C major (cf. 2nd-theme

recapitulation in 1st movement of Ravel's Quartet)

161-6: compression of ideas from 39-57; ?j much more agitated than jg exposition c?

167-9: tetrachord (from 47-8) thrice |

repeated in diminution ?

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

49-57: 2nd theme, 3rd statement, in

augmentation and piano 58-61: codetta built around T; music

comes to a near stop

TABLE 3 continued

section 1 (62-6): based on 1-11 section 2 (67-80): combination of a

(accompaniment and ostinato) and T

(melodic interest) section 3 (81-3): a'as dramatic

interruption section 4 (84-8): similar to 2nd half of

section 2 section 5 (89-94): extension of section 3 section 6 (95-101): agitato derived from

19-22 section 7 (102-13): short introduction

from ad, then contrapuntal combination of a and b, b becomes more prominent at section end

section 8 (114-24): impassioned statement pib fragments; metre

effectively switches to 12/8; ad in

accompaniment

section 9 (125-8): transition to

recapitulation built on ostinato use of ad

o z o

I

coda (170-6) ostinato built on a6, used extensively

along with tetrachord diminution; final dominant identical with dominant used to begin the

recapitulation

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

268 STEVE SWAYNE

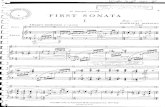

Example 3. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars

1-4.

Allegro moderato (J = 138)

a

are metrically smaller than 4/4. From the description of the discrete

sections within the development itself, one can further see that the

development section is far from trenchant. Indeed, because of the

nature of Sondheim's musical material, the concept of development becomes problematic, as the opening of the sonata demonstrates

(Example 3). The first phrase of the sonata encapsulates the procedures that Sond?

heim used throughout the sonata. The harmonic language makes a nod

to convention, with a bass line that clearly traces a I-IV-V-I progression. The chords, however, are all substitutes for the expected chords: the

opening tonic has an added ninth, is missing the third, and has an

accented fourth that may, in fact, redefine the function of the chord; the subdominant is a chromatically inflected ninth chord; the dominant

is a suspended chord. Only the closing tonic resembles a classic C major chord, and even it is bent by an appoggiatura in the alto voice. These

alternative harmonies arise from Sondheim's linear writing: no fewer than four voices make up the contrapuntal fabric. The phrase marks and

pedal marks leave litde to the whim of the performer, and in the outer

movements Sondheim was precise in his markings. The motivic aspects of the opening warrant separate discussion. The

three-note motif that opens the piece - the ascending perfect fifth fol-

lowed by the descending second - immediately folds back on itself and

is repeated a fourth higher. It is then answered by a modified inversion

of the same idea in the alto register. The rest of the sonata will give

ample evidence that Sondheim chose this three-note gesture for its

protean quality. In the first movement alone it will be used extensively as melody, figuration and accompaniment, in its original form, in inver? sion and in diminution. The motif will also provide the kernel from

which the principal melodies are derived for the other two movements. In other words, Sondheim chose his basic musical material so as to

develop it immediately and continuously. Such motivic concentration embodies Sondheim's beliefs of the

time, reflected in his contemporaneous senior analysis paper on

Copland, in which he cited as 'one of Copland's greatest virtues' the

manner in which the older composer thoroughly utilized his musical

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sondheim's piano sonata 269

Example 4. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars

9-13.

_Ji__ ,f___ -1?v \t*M i- _______jjm_u_.

__ 3 "

a m

=_

t

A a

r

#^##

3&. * r r

materials in his Music for the Theatre.13 Here, in the sonata, Sondheim

plotted out a piece almost as long as Copland's but one that uses a

smaller nucleus than did Music for the Theatre.1* By writing the sonata in

the way he did, Sondheim subjected his philosophy about the import? ance of effective motivic construction to an extreme test, i.e. how to

compose three distinct movements based on the same three-note motif

without succumbing to repetition or triviality. While he was not entirely successful in making the motif interesting

- the first movement in

particular has its longueurs - Sondheim here set out on a composi?

tional path to which he would return in Sweeney Todd (1979) and the

musicals that followed, works noted for their motivic construction.15

After this confident and assertive opening, the second phrase varies

the motif/first-group material rhythmically and directionally. Sond?

heim's repeated use of mirrored statements ofthe motif further under-

scores his interest in counterpoint at this juncture in his compositional

development. An awkward transition from a highly inflected F minor to

a stark E minor also brings in a new thematic idea, notable for the

heraldic repetition of the E and the triplets that follow (bar 12). These

two gestures, sometimes presented in tandem, sometimes separated, will

recur at pivotal moments throughout the movement (Example 4). The

motif temporarily recedes in the background as the new idea briefly

13 Stephen Sondheim, 'Notes and Comment on Aaron Copland with Special Reference to his Suite, Music for the Theatre' (unpublished paper, 1950), 5. This paper is now housed at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research at the University of Wisconsin (hereafter 'Wisconsin'). See also Steve Swayne, 'Music for the Theatre, the Young Copland, and the Younger Sondheim', American Music, 20/1 (spring 2002), 80-101.

14 For an analysis and history of Music for the Theatre, see Larry Starr, The Voice of Solitary Contemplation: Copland's Music for the Theatre Viewed as a Journey of Self-Discovery', American Music (forthcoming), and Howard Pollack, Aaron Copland: The Life and Work ofan Uncommon Man (Urbana and Chicago, 2000), 128-34.

15 The best and most widely available analysis of Sweeney Todd is found in Joseph P. Swain, The Broadway Musical: A Critical and Musical Survey (Oxford, 1990), 319-54. Sondheim had engaged in motivic writing prior to Sweeney Todd, as can be clearly seen in Anyone Can Whistle (1964). But when asked whether he was a 'motivic-oriented composer, one who builds a melody and an entire score out of small and motivic components', Sondheim responded: T started to put my toe in the water .. . with Pacific Overtures. Then, it sprang full flower in Sweeney.' See Steven Robert Swayne, 'Hearing Sondheim's Voices' (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California, Berkeley, 1999), 344; pp. 331-49 reproduce the author's 1998 interview with Stephen Sondheim.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

270 STEVE SWAYNE

Example 5. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars

22-5.

M rppjy

M Jp JjJS

_?

___4J /Nj y_ =____

a i s: t ip m

*r=rr

$fi>.

turns lyrical. The triplet gesture is used in a sequence, after which the

music becomes more agitated with the presence, for the first time, of

semiquavers. This transitional music is loosely derived from the motif -

especially as it appeared in the first bar - and itself will reappear later

with its distinctive auxiliary-note figure and the concluding arpeggio. The music is clearly building up tension on its way to the next signifi? cant structural signpost; even the motif definitely returns, but in diminu-

tion, in keeping with the rush towards the second thematic group. The

music erupts in a cascade of figuration both derived from the motif and

reminiscent ofthe heraldic/triplet idea, with its E-B bass (Example 5). Yet another transitional passage, this one marked/wnoso and with the

motif diminution now in the left hand as an accompaniment figure, leads to the second subject, in the relative minor (Example 6). Its

resemblance to the comparable theme in the first movement of the

Ravel Quartet is more than incidental (Example 7). Both themes

initially appear in the relative minor. Both prominendy feature the

9-8-7-6 tetrachord, first in descending motion and then in an ascend-

ing answer (bars 56 and 58 of the Ravel melody). Both themes share

the same rhythmic contour, with Sondheim's rhythm being an aug- mentation of Ravel's. These are all suggestive but not conclusive. Alook

at Sondheim's recapitulation, however, provides the telltale evidence

that he had the Ravel in mind when he was composing his sonata.

Ravel's theme is notable for the manner in which it is recapitulated in

the tonic major without a shift of the pitch classes; the tetrachord thus

becomes 7-6-5-4. Sondheim's theme reappears in precisely the same

way (Example 8). (One might further posit that Sondheim's three-note

motif is derived from the first three notes of the Ravel melody, though this would be far more difficult to prove.)

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SONDHEIM'S piano sonata 271

Example 6. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars

30-5.

Ravel is not the only modern musician lurking behind Sondheim's

second theme. The sinuous accompaniment of Example 6 resembles

the piano writing of Prokofiev. Sondheim not only knew but may have

also played some ofthe Visions fugitives, op. 22, prior to his matricula-

tion to Williams (see Example 9).16 Sondheim's texture is more

involved than that of the Visions fugitives and more closely resembles

passages from Prokofiev's piano sonatas, although Sondheim said he

was not familiar with Prokofiev's sonatas at the time he was writing his

own sonata.17 Despite this unfamiliarity, the third statement of Sond? heim's second theme, in augmentation and marked piano, looks and

sounds like a page lifted straight out of one of Prokofiev's nine piano sonatas (Example 10).

In addition, Sondheim used the term martellato at bars 199 and 125 in the development and a third time at bar 170 in the coda. (It also

appears in the coda ofthe third movement at bar 165.) One associates

16 Sondheim: T never studied Prokofiev's piano sonatas and I didn't become familiar with them until after college. The only Prokofiev pieces I might have been in contact with as part of my piano playing career [was] when I was 15-16 years old. I have a memory of the Visions Fugitives, but that [and] the Love for Three Oranges "March," which I played on the piano, are the only Prokofiev I think I ever came into immediate contact with.' Personal correspondence, 21 March 2001. In this context, 'study' suggests preparation for public performance. 17 See note 16. The similarities between Sondheim's second theme (first movement) and the second theme of Prokofiev's one-movement Sonata no. 3 in A minor, op. 28, are particularly suggestive. In the Prokofiev, the tenor line traces a descending-ascending tetrachord, 8-7-6-5 of the C major sonority in the first bar but 9-8-7-6 of the D minor sonority in the third bar. Like the Ravel and the Sondheim, the Prokofiev presents the second theme in the relative key (here, C major) and recapitulates it in the tonic key without shifting the pitch classes.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

272 STEVE SWAYNE

Example 7. Ravel, Quartet in F major, first movement, second theme.

pp tresexpr.

ri 55 I ? itl f~h fn _ ___

vlns | 1,2 &-T u U' U'

* __i

_c__ tresexpr. ^ m

f rrr rr

j. JI2

vlc

55

pizz.l *=T r r

l n? n i-?-rm

L-Jf L?J*

Jr -A-JJ2

*==f=f

Example 8. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars

152-7.

# %*. *$&.

/5ff ^?^jtg: a

fiEMM i___b

%b.

'hammered out' piano not with Ravel (or with Sondheim, for that

matter) but with Prokofiev and his percussive piano style. At this time

Sondheim was also playing the transcription of the March from The

Love for Three Oranges, whose opening, with its two bars of repeated

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sondheim's piano sonata 273

Example 9. Prokofiev, Visions fugitives, op. 22 no. 3 (Allegretto), bars

1-4.

|t*j j i I j h

fflp n

ffl^^

s rj^*^ r^*^

i i-Qb-Q

^^ r p

Example 10. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars 49-53.

52 i)

iglg 11 fl

rg

s s

^TO-^

notes, has a martellatoiike character to it. Prokofiev, however, never

used the term martellato in his piano music,18 so Sondheim evidendy encountered it elsewhere, as will be seen below.

Whereas Sondheim's indebtedness to Ravel has been and continues

to be explored, the connections between Sondheim and Prokofiev are

virtually uncharted. In his study Sondheim's Broadway Musicals, Stephen

18 Although Prokofiev did not use the term marteUato, there is percussive writing in the Visions fugitives, especially nos. 14 and 19. The term marteUato appears three times in Gyorgy Sandor's edition of Prokofiev's Third Sonata - twice in the development and once in the coda - but this edition did not appear until 1966, and earlier versions of the sonata do not use the term.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

274 STEVE SWAYNE

Example 11. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars 67-72.

"illin Wrigi

marcato

Banfield writes about the Trokofiev-like polytonality' of There's Some?

thing About a War' (cut from A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the

Forum) and the 'uncharacteristically discursive' harmonic scheme of

'Green Finch and Linnet Bird' from Sweeney Todd which 'could almost

have been written by Prokofiev or Berkeley'.19 But the links between

Sondheim and Prokofiev clearly run deeper than a harmonic similarity here and there. Prokofiev's linear writing and acerbic harmonies must

have delighted Sondheim, whose own work is suffused with involved

linear writing and non-conventional harmonizations. And Sondheim's

predilection for ostinati and vamps finds a cognate in Prokofiev's

motoric rhythms. The passage from the development of Sondheim's

sonata shown in Example 11 demonstrates his ability yet again to put his three-note motif through its paces, the result being a sound not far

removed from the mechanistic writing for which Prokofiev is famed

(note the presence of the heraldic/triplet idea). Motoric ostinati are to be found in nearly every mature Sondheim

show. To pickjust one from a score full of examples, Sunday in the Park

with George (1984) uses an ostinato which accompanies the painter

Georges Seurat when he is engaged in painting in his pointillistic manner and which recurs elsewhere in the musical (Example 12); this

particular example comes from 'Color and Light'.20 The similarity between this ostinato and a passage in the development of the sonata, written 34 years earlier, is striking (Example 13), and in each case the

sound world of Prokofiev is in the near distance. (Notice again the use

19 Stephen Banfield, Sondheim's Broadway Musicals (Ann Arbor, 1993) (hereafter SBM), 99 and 292.

20 'Color and Light', music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim ? 1984 Rilting Music, Inc. All rights administered by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved. Used by permission. Warner Bros. Publi? cations U.S. Inc, Miami, FL 33014.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SONDHEIM'S PIANO SONATA 275

Example 12. 'Color and Light' (Sunday in the Park with George), bars

172-5.

Example 13. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars 86-9.

of the motif in the left hand.) Considering Sondheim's penchant towards pastiche, other parallels between his music and the music of

Prokofiev are waiting to be drawn. The linearity of multiple voices, the

texture of the piano accompaniments, the dissonant tonal harmonies, and the deployment of motoric ostinati in the works of both composers

suggest that further exploration of the connections is warranted.

Two other passages from the first movement deserve mention. In his

musicals, Sondheim is noted for layering one melody on top of the

other, typically in ensemble numbers and often before a climactic

reprise of the main musical idea of the ensemble (e.g. Tt's a Hit!' in

Merrily We Roll Along, Tlease, Hello' in Pacific Overtures, the trio from

'Soon' in A Little Night Music, the 'Johanna' quartet in Sweeney Todd, and others). In the sonata we find an early example of this quodlibet- like aspect of Sondheim's style, as Sondheim in the development section cleverly interleaved the first and second themes (Example 14). Here again, the piano writing bears an uncanny resemblance to

Prokofiev's, although the marriage of first and second themes can be

found in the first movement of Hindemith's Third Piano Sonata in Bt

(1936), another sonata that Sondheim's sonata - especially the third

movement - brings to mind.

The second passage of note is found in the coda of this first move?

ment, where Sondheim recapitulated material that appears only in the

development section. The figuration from the final section of the

development, once again built from the three-note motif, winds down

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

276 STEVE SWAYNE

Example 14. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars 106-12.

uo

-i *? m i=a m

i Ltijt p T

=f cresc. poco a poco

U *f ?y \-rif dt

i 'frn'Tn ^

wm m T-^ Sfi>. * 5a. * %b.

Example 15. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars 125-9.

rit. molto 125

<t) H; ?J\rJ-J/ zi ?*? w7 z" ?*" ~w7 ~L ~*^w7 zr ? w7 z "?*" "J"/N JJDQt p

martellato mp

dim. poco a poco

njTTf 1^ ijjjJ JT^ $&. # 3a.

Jgju i^

ta^

tempo pnmo

IS

*/

to a dominant chord with a flattened fifth (Example 15).21 Sondheim

repeated the figuration and the altered dominant at the end of this

movement (Example 16). The third movement similarly contains

material from the central section of the movement that returns in the

21 Note how Sondheim demarcated the development and the recapitulation with a double barline; the same demarcation separates the exposition from the development.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SONDHEIM'S PIANO SONATA 277

Example 16. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, first movement, bars 168-70.

coda, giving us two examples in this sonata of a technique Sondheim

will use in his maturity: the delayed presentation of important and

recurring musical material.

In discussing the manuscripts of the completed movements, one

could summarize the differences between the two manuscripts as one

of excess (first movement) versus efficiency (third movement). Musi-

cally, the first movement contains a surfeit of material, not only in the

development but in the other sections as well. As Table 3 shows, tran?

sitional material from the exposition proves to be almost as significant in the development as do the two main themes. The second theme in

particular is fragmented in the development to the point of being

nearly unrecognizable. Some of the transitions are jarring, and some

of the passage-work sounds contrived. Given the numerous short-

comings in the first movement, one might sympathize with Sondheim's

decision to leave the sonata unrevised and unpublished. This is a far cry, however, from saying that the first movement is

atrocious. The music may be out of balance at certain points, but the

skill revealed in the sonata is considerable. In addition to the element

of craft, one gets from the first movement a sense of passion and

engagement, as ideas build to dramatic (and generally effective) musical climaxes. The music is both deeply heartfelt and calculated to

an almost unnatural degree. In Sondheim's case, at this early stage in

his career, these two aspects of composition are not as separable as they

might be with other composers at a comparable level of musical matur?

ity (Chopin springs to mind). Here in the first movement, the calcu-

lations are in general too close to the surface and thus make the

passions sound less mature. Sondheim would grow in his ability to

handle large-scale musico-dramatic structures;22 the third movement

already provides an illustration of how Sondheim learnt to hide some

of his calculations more skilfully. But before I turn to that completed movement, there is more to say about the second movement.

22 See Banfield's discussion of 'Someone in a Tree' (SBM, 267-71), where he speaks of Sondheim's 'additive' and 'permutationaT techniques in this song and, by implication, Sondheim's other extended songs (see p. 358 for other examples).

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

278 STEVE SWAYNE

The sketch of the second movement contains 32 bars of continuous

music before it breaks off inconclusively. There are, however, numer-

ous instances of erasures and second thoughts throughout the sketch.

No dynamic marks are provided, and there is only one expression mark

(a marc. at bar 27) as well as a few phrase marks and one ritard followed

by a Tempo Primo. The manuscripts of the other two movements, in

contrast, are full of dynamics, pedal markings and other expressive indications. In this sketch, Sondheim had not completely settled on

how this portion of the second movement should sound, let alone how

it might continue.

Marked 'Andante', the music has a key signature of five flats. This is

something ofa curiosity, as the opening bass line undulates between Et

and At and the first real cadence at bars 11 and 12 moves from a Dt

suspended chord to a Gt major ninth chord. The movement has a

texture akin to a Satie gymnopedie. a 3/4 time signature; a bass line of

one note per bar; a tenor-register chord that enters on beat 2; the four-

bar introduction before the sinuous melody line appears (Example 17). The combination of these musical details suggests that Et Dorian

could be the mode Sondheim has chosen. Before this mode is con?

firmed, however, the music begins to use sharps and flats in equal measure and in a decidedly un-gymnopedie fashion. The harmonic

rhythm here speeds up as Sondheim employed his standard suspended- chord substitution for the dominant chord in a cadential formula. In

fact, two cadences a semitone apart chime back and forth. The disso-

nant bell-like notes on beat 3 will later coalesce into the first three bars

of the opening melody, now in D Dorian and in the upper register of

the piano (Example 18). After this melodie fragment, die music grows more agitated with an eruption of semiquavers that incorporates the

suspended-chord cadential formula. A slackening of tempo, a return

to quaver motion, and a 4/4 bar lead to a third statement of the

melody, this time with its first four bars in the bass. The writing here is

contrapuntally conceived, with four independent voices, though the

impression is one of stasis. After a one-bar passage of ascending semi?

quavers, Example 1 occurs, and the sketch ends.

It is difficult to imagine in what direction the movement would have

gone from this point forward. A few months later, Sondheim encoun?

tered difficulties with another slow movement, that of his Concertino

for Two Pianos (c. autumn 1950). In preparing it for its premiere nearly 50 years later, Sondheim made a few small cuts in the first movement

and extensive cuts in the 'endless' second movement.23 One could

posit that the second movement of the earlier sonata is also (and

literally) endless because, at this time in his writing career, Sondheim

found it difficult to control his musical material when it unfolds at a

more languorous rate. Indeed, a cursory overview of his mature songs turns up scant few where the melody unwinds in a plaintive arioso (e.g. sections of 'There Is No Other Way' in Pacific Overtures, Anthony's

'Johanna' in Sweeney Todd). More frequently, his ballads incorporate

23 Personal correspondence, 19 January 2001.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SONDHEIM'S piano sonata 279

Example 17. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, second movement, bars 1-8.

Andante

Example 18. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, second movement, bars 13-18.

13

2P_=? fejg? ?*m ?_S

Sva,

i m m* ^^^a ^m^

rf

tU l LdX l **%

m E

S=S m ^m

r=rf ?

more active melody lines that come to rest on longer notes (e.g. 'Send

in the Clowns' in A Little Night Music, 'Good Thing Going' in Merrily We

Roll Along, 'No One is Alone' in Into the Woods, 'What Can you Lose?' in Dick Tracy, T Read' in Passion).

But the second movement does sound strikingly like another Sond?

heim song, one that was written for the musical-in-progress The Girls

Upstairs (begun in 1965), withdrawn, and then reincorporated in the

overture of the renamed Follies (1971). 'All Things Bright and Beauti?

ful' is also in 3/4, has a gymnopedie-like accompaniment and a long- breathed melody, and contains chains of suspended chords that slip from one to the other by semitone motion. The song is also noteworthy for the number of expression marks Sondheim employed here, includ?

ing the unusual designation colla voce, making the song look like the

outer movements ofthe sonata in its expressive exactitude. The resem?

blance between the two works is so extraordinary, in fact, that a rework-

ing of the song could easily serve as a central section for a slow

movement east in ternary form, even though a distance of 16 years sep- arates the sonata from the song (Example 19) ,24

24 For the USA and Canada: 'All Things Bright and Beautiful'. Words and music by Stephen Sondheim. Copyright ? 1971 by Range Road Music Inc, Quartet Music Inc. and Rilting Music, Inc. Copyright renewed. All rights administered by Herald Square Music Inc. International copyright secured. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

For the world excluding the USA and Canada: 'All Things Bright and Beautiful' - Stephen Sondheim. ? 1971 Range Road Music Inc, Quartet Music Inc, Rilting Music, Inc. and Burthen Music Company, Inc All rights administered by Herald Square Music Inc. Copyright renewed. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

280 STEVE SWAYNE

The third movement, like the first, shows Sondheim's concern for

traditional forms and architectural balance even as it gives greater evi?

dence of motivic and structural creativity. Cast in a large ternary form

(ABA'), the movement combines elements of sonata and rondo form

without being a Beethovenian sonata-rondo (as in the final movement

of the Second Symphony). Where the first A section is itself cast in

ternary form, suggesting a rondo for the whole movement, the second

A' section is binary in form, in keeping with the recapitulation of a

sonata. The central B section - more a respite from, rather than a result

of, the outer sections - gives free rein to Sondheim's contrapuntal skills

and culminates in a fugato. Table 4 provides a schematic overview of

the third movement.

The workmanlike three notes of the main motif once again serve as

the basis for a large proportion of the musical material in this move?

ment (see Example 20) ,25 As in the first movement, the music opens with the upward leap of a perfect fifth followed by the descent of a

major second; once again, the basic rhythm is short-short-long (marked a). But a number of alterations make the motif sound new. It

now begins on the fifth scale degree instead of the tonic, starts with a

quaver pickup to the first bar instead of on beat 2, and is accompanied

by independent voices instead of being anticipated by an emphatic chord. Together with the slighdy slower tempo, these changes provide a contrast to the declamatory nature of the first movement's opening and combine here to give the motif a yearning quality (for example, the melodic appoggiatura of the right hand resolves on the tonic after

the downbeat). Moreover, after the motif has been stated, the music continues with

variants of it. The bass voice immediately echoes the first two notes of

the soprano - a truncation ofthe motif-with its arpeggiated fifths. The

soprano presents no fewer than three variants ofthe motif in quick suc- cession: the original; a variant that features a downward fourth instead

of the upward fifth; a five-note elision of these first two (the centre of

which is marked r, compare b in Example 3); and a fragment that con?

tains only the upward fifth. At the same time, the alto contrarily answers

the soprano with inversions ofthe stepwise-moving section ofthe motif, sometimes following the soprano, sometimes coming in with the

soprano, and sometimes anticipating the activity of the soprano. Sond? heim could have added 'giocoso' to his tempo marking, as the voices

play with each other, taking turns as they expand their independent but related musical ideas. The counterpoint that opened the first move?

ment clearly established a hierarchy where the top voice reigned. Here, the clear three-voice writing of the first two bars provides a clue from the very beginning of the movement that the activity in the inner and lower voices will prove to be as important as what is occurring in the

soprano.

25 See Table 4, note a, for an explanation of the bar-numbering in this movement.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SONDHEIM S PIANO SONATA 281

Example 19. 'All Things Bright and Beautiful', bars 65-77.

65 a tempo, poco rubato poco rit

All

^ l=? ?

things

j?

Bright and beau - ti - ful,

*

H ^m colla voce f

mm ^^ i *=$ a fg %. f

5o5. ̂a/..

tfS a tempo =tbt t uTjf f j?

Ev- 'ry-thing for - ev - er, ask Ev-'ry-thing for-

H,n? ii. ?rf3 n W r ^=&g

fT

d&L ZKC5!

UP- d?F

4^r r

i

^ 4

ry day..

*=k S

ff^ *-Bf

*Wfr^ &m u ^M^

r

After a scalar gesture that will later figure prominently as a tran-

sitional figure (bar 3, right hand), the main idea returns (Example 21).

Only two bars separate the two statements of the main idea, but Sond?

heim ingeniously varied the pitches ofthe idea at its repeat. The return

is so emphatic, in fact, that the alteration could pass unnoticed. But this

is no slavish imitation. Where the leap of a perfect fifth opened the

motif before, now it is a major sixth, and the other intervals ofthe motif

now outline a C major pentatonic scale as the accompaniment begins

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TABLE 4 ?g

SONDHEIM, PIANO SONATA IN C MAJOR, THIRD MOVEMENT

(numbers are those of bars)a

A (1-73) B (74-118) A' (119-70)

ternary (ABAr) with codetta A (1-27): first-theme group

1-10:1st theme, repeat of 1st theme and extension

11-19: sequence of lst-theme rhythm; ostinato accompaniment; climax and relaxation at 18-19

20-7: transition theme B (28-51): second-theme group

28-38: introduction, 2nd theme and extension

39-42: sequence of 2nd-theme

fragments

43-8: transition built up of juxtaposed and combined elements from A and B

49-51: transition derived primarily from rhythm of 1 and melodie line of lst half of 2

binary (CD)

C (74-100): intermezzo 74-9: main idea derived from 1

80-4: development of 2nd half of 74 85-?: reiteration of main idea 89-95: lyrical expansion of main idea

fragment

binary (AB') with coda A (119-45): verbatim restatement of 1-27

119-28:: 1-10

129-37:: 11-19

138-45 :: 20-7 B' (146-60): second-theme group

146-56: 2nd theme and extension, but with different accompaniment from that in 28-38

157-60 :: 39-42

coda (161-70) 161-2: transition material similar to

43-4

163-4: recapitulation of 80-4

i I

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TABLE 4 continued ? o

96-100: augmentation, climax and ?? relaxation based on main idea g

D (101-18): fugato ?

101-2: subject derived from 74 g 103-6: answer, fifth below; countersubject ?

includes motif of upward leap followed co

by scalar descent; 2 bars free counterpoint 2 107-15: answer, tenth below; countersubject H

motif present; 7 bars free counterpoint; hint of Aat 115

116-18: subject, 2 octaves below; continuation of A; 1-bar transition

A' (52-67): recapitulation of first-theme

group 52-60: 1st theme, repeat of 1st theme

and extension; 52-6 :: 1-5; equivalent of 6 missing; 57-60 similar to 7-10, with different

accompaniment at 7/57 61-9: sequence of lst-theme rhythm;

ostinato accompaniment; 68-9 similar to 18?19

codetta (70-3) 70-1: development of material in 49-51 72: climactic augmentation and re-

harmonization of 1st half of 2 73: emphatic statement of upward-fifth

motif (2nd half of 2)

165-6: reharmonization of 70-1 167-8: augmentation of 72

169-70: thrice-repeated statement of

upward-fifth motif (73)

a The numbering used in this article treats the movement's first bar in the manuscript - a full 4/4 bar consisting entirely of rests save for a single quaver at the end - as a ?g null bar (as in Example 20, where the original bar 1 is reduced to a pick-up). oo

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

284 STEVE SWAYNE

Example 20. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 1-2.

Allegro (J = 126)

Example 21. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 3-6.

$&. *$a.

to take the music away from the tonic. The effect is both dramatic and

sure-footed. Notice also the inversion ofthe main motif in the left hand

in bar 3, as well as the descending fifths in bars 5 and 6, yet another instance of Sondheim's contrapuntal bent.

The scalar transitional figure blossoms into a true scale, taking us

into the tenor register of the piano. It is here that the music presents an ostinato figure in the right hand derived from the first theme (see c in Example 20) while the left hand provides both fundament and

melody. The movement may have started out sounding vaguely French, but the jagged and insistent rhythm of the ostinato hammers

home the sonata's American roots. Moreover, both the ostinato and the harmonies -

suspended chords and second-inversion major seventh or ninth chords - sound as though they were lifted wholesale

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

SONDHEIM'S PIANO SONATA 285

Example 22. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 11-13.

3fc. -*

a j

i n~Pl

JTBJ^BTCT

?e- %6.

out of 'Company' or The Miller's Son' (A Little Night Music), songs that, at the time of the sonata, were 20 years away. Sondheim's voice

here is unmistakable (Example 22). The ostinato and its harmonic components are first repeated and

then compressed, and the resulting tension finds release in 3,fortissimo whole-tone sonority that dissolves into the relative minor. The subse?

quent theme that emerges at bar 20 sounds peculiarly edgy; while set

within the framework of two 4/4 bars, the melody uses long and short

rhythms in an unpredictable, almost erratic manner. It is a finely crafted and distinct second theme in the classic sonata form, but in fact

it is only a transitional theme which soon gives way to a sequential

passage built around quartal harmonies (Example 23). Formally the

transition both fulfils and thwarts the expectations of sonata form; har-

monically, the passage employs some ofthe most Hindemithian sonori-

ties thus far encountered in this movement.

Whereas both the first theme and the transition are anchored in a

key - C major and A minor, respectively

- the actual second theme is

anchored on a pitch. A brief introduction (bars 28-9) adumbrates the

theme in the right hand while the left hand descends from E to A, the

central pitch of this episode. At this point (bars 30-1), the second

theme is presented in full: an undulating theme notable for its use of

large intervals with the longer notes (d) and scalar figures with the

semiquavers (e) (Example 24). The Hindemith ofthe Third Sonata -

particularly the scherzo, with its mixture of tertian and quartal writing - here gives way to Ravel. Notice the continued use of counterpoint in

the inner voices.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

286 STEVE SWAYNE

Example 23. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 20-3.

_HHM^_???-??_-=___I_?M-i_n_M_l---M- ... -_=_--1_ ._l| H | II nini || ?

%b. *%b. % sa>. *?, *

Sfo.

Example 24. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 28-31.

* $a.

Sondheim's skill in manipulating his musical motifs is on display

throughout this section. Two moments in particular deserve comment. In an elaboration of the second theme, Sondheim employed a diminu-

tion of d as accompaniment to the regular form of d in bar 39, which

is followed by a syncopated melisma derived from e in bar 40. Quartal harmonies and seventh chords vie for prominence (Example 25). Even

more artful is the way Sondheim juxtaposed the first and a diminution

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sondheim's piano sonata 287

Example 25. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 39-40.

Example 26. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 45-7.

of the second themes - in the left and right hands, respectively - in the

transition back to the music that opened the movement (Example 26). As Table 4 shows, the return to the first group, with its transposition

of material and minor rewriting of accompaniment figures, remains

fairly true to the opening of the movement. It is the four-bar codetta

to the larger, self-contained A section of the movement that stands out

for its stentorian delivery of the opening motif and its harmonic

sophistication in handling dissonant sonorities as pre-dominants and

dominants (Example 27). Notice yet again the use of a suspended dominant sonority for the penultimate chord. It will be this material, almost doubled in length, that will close the movement and the sonata.

This grand pause mid-movement signals a change not only of tempo but also of texture and mood. While inner voices earlier provided traces of contrapuntal lines, the central section of this movement is

saturated with counterpoint, so much so that, halfway through the

section, the music pauses yet again, this time to introduce an extended

fugal treatment of the thematic material. Each half of this central

section also has its particular harmonic east: a turgid intermezzo that

moves from the minor to a luminescent major to quartal harmony and

then back to the minor mode, followed by the fugato - so marked in

the score - that begins with the quartal harmony ofthe intermezzo and

heads towards free dissonance. Presented at a pace slightly slower than

what has come before, the two halves constitute a lengthy binary inter?

lude to the outer sections of the movement, an interlude too large for

a classic rondo and too distinct to be called a development section.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

288 STEVESWAYNE

Example 27. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 70-3.

f4#

ffg ii ?rrn-rrn m fff

__

pr; p r-

m W4 n ______ *RF^

^

__

'1 ?!?>-?- >^^t

Nevertheless, the basic musical material once again is derived from the

same three-note cell around which the entire sonata is organized, thus

making it developmental at the same time as it is original. The coun?

terpoint is awkward at times, especially in the fugato, but the sense of

formal balance and musical contrast is unerring and remarkable for

someone who had not written many extended compositions.

Example 28 tabulates the motivic relationships between the interlude

and the openings ofthe other three movements. For the first theme of

the first movement, the motif appears in its original form; all other

motifs have been transposed to this opening pitch for the sake of

comparison. An asterisk above a note signifies that it has been trans?

posed up from its original octave. This motivic economy over the

course of a composition more than 300 bars long clearly demonstrates

that Sondheim's interest in generating larger musical structures from

smaller motivic kernels pre-dates his postgraduate studies with Milton

Babbitt.26 If anything, here Sondheim appears to have been fixated on

squeezing as much musical juice out of his motif as possible. Of particu? lar note is how, for the second movement and the intermezzo, Sond?

heim manipulated the motif to appear in a minor mode, a feat made

manageable by leaving the third degree of the scale out of the 'Ur-

version' of the motif.

The use of the minor mode in the intermezzo is only one reason the

ubiquitous motif sounds fresh. In addition to the variations of rhythm and number of notes, Sondheim continually varied which notes of the

motif receive the main stress. The variation ofthe motif that opens this

third movement consists of two amphibrachs; in the intermezzo, the

motif opens with an iamb followed by an anapaest (Example 29, left

hand). Here the motif, marked marcato and appearing in the tenor

register, uses the upward leap of a fifth and then continues with a

second upward leap of a fourth (a). As the accompaniment figure shows, it is this secondary leap resolving stepwise in the opposite

26 See SBM, 22.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sondheim's piano sonata 289

Example 28. Motivic relationship in Sondheim's Piano Sonata in C

major.

lst movement, 1st theme

2nd movement

3rd movement, lst theme

| j J J J f

J

3rd movement, intermezzo and fugat< ? $ j^'

* * *

y j p n

^^

direction that receives the most thorough treatment. In the right hand, the motif in diminution continuously folds back upon itself (a). The

tenor melodie idea moves beyond the motif to incorporate an ascend-

ing scale that is reminiscent of the second theme of the third move? ment (e). The dramatic change of character from the opening section

to the intermezzo effectively obscures the derivative nature of most of

the musical material in this central section.27

The piano writing for this intermezzo finds Sondheim at his most

Ravelian. The sound world of the Sonatine and Jeux d'eau lies just

beyond Sondheim's harmonies, which continue to emulate Hinde-

mith's Third Piano Sonata. The texture, however, is vintage Ravel, down to the cascading demisemiquaver arpeggios that appear immedi?

ately before the return of the main intermezzo idea. After the melody turns to the major mode, the music puckishly dances around the key- board, almost in echo of 'Ondine' from Gaspard de la nuit (Example 30). The notation is unusual not only for its three staves but also for

the figuration in the right hand in bar 91, which, though marked stac?

cato, is phrased throughout. In the fastidiousness that marks most of

the manuscript - witness the superabundance of pedal markings

-

Sondheim wanted to make sure the reader would see the shape of the

line.

After a climax that sounds more forced than inevitable, the harmonic

rhythm slows down and the texture thins out to make way for a fugato built on the same melodie idea as the intermezzo (Example 31).

Throughout the sonata and especially in the intermezzo, Sondheim

had demonstrated his interest and skill in counterpoint, and this fugato serves as the capstone of his contrapuntal writing. It nevertheless feels like a miscalculation. It does little to develop the musical material

beyond what the intermezzo has already done. It also postpones the

27 While it is most likely a contrapuntal happenstance rather than a deliberate derivation, the alto voice in this figure could be construed as an augmentation of the d material in the second theme of this movement.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

290 STEVE SWAYNE

reprise of the opening and threatens the architectural balance of the

emerging sonata-rondo form. And pianistically it is one of the more

ungrateful moments in the sonata. Beyond its obvious technical value

as an exercise in fugal writing, what might have been Sondheim's (and

Barrow's) aesthetic aim in including a fugato in the third movement?

Given Sondheim's admission that a comparison between his sonata

and the music of Hindemith is 'on the nose',28 a counterpart of Sond?

heim's fugato can be found yet again in Hindemith's Third Piano

Sonata. There, the fourth movement is a boisterous double fugue whose

second subject is taken wholesale from a fugato section in the slow third

movement. In addition, the subject entries in the Hindemith exposi- tions do not follow the standard tonic-dominant-tonic exposition of a

Baroque fugue but enter as tonic-dominant-supertonic-tonic. Simi-

larly, Sondheim took his subject for the fugato from earlier in the sonata

(the intermezzo), and the fugal answers enter at the subdominant and

the mediant. Another telling feature about Sondheim's fugato is that it

is the only place in the outer movements that has a key signature -

G minor, presumably -

although Sondheim quickly goes far afield from

any tonal base. (The Hindemith uses no key signatures and is tonally

free-ranging but is in the key of Bk) Hindemith's Third Piano Sonata also employs quartal and quintal

harmonies within its basic triadic framework. The climactic passage from the third movement of the Hindemith shown in Example 32 is

clearly rooted in A, but triads yield to more complex chords, with some

that remain in a tertian universe and others that move into a quartal realm. One does not have to look far in the Hindemith to find other

similar passages. Hindemith's influence on Sondheim's sonata has been noted before.

Although he had not seen the sonata, Banfield presciendy remarked

that it showed an indebtedness to Hindemith, surmising that Barrow's

influence on Sondheim - and Hindemith's on Barrow - would echo

through the sonata.29 And although quartal harmony has also been

attributed to Barrow's other European teacher, Vaughan Williams, the

linear-contrapuntal writing in much of the Sondheim resembles 'the

linear-contrapuntal manner of the New Objectivity (neue Sach-

lichkeit)', to use David Neumeyer's description of Hindemith's musical

language.30 Elsewhere Neumeyer referred to 'Hindemithian counter?

point - with its arched tension curves, crisp formal contours, and

melodies and harmonies of seconds and fourths', features evident

28 Personal correspondence, 19 January 2001. 29 SBM, 19. Banfield refers to the piece as a three-movement sonata, giving the impression of

a completed work rather than a projected conception. 30 Alain Frogley, 'Vaughan Williams, Ralph', The New Grove Dictionary ofMusk and Musicians (2nd edn, online version), accessed 12 March 2001; David Neumeyer, The Music of Paul Hindemith (New Haven, CT, 1986), 4. Not everyone shared Hindemith's enthusiasm for Kurth's notion of linear counterpoint; Schoenberg dismissed it as 'nonsense' and 'imitation-imitation'. See Arnold Schoenberg, 'Linear Counterpoint' and 'Linear Counterpoint: Linear Polyphony', Style and Idea: Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg (Berkeley, 1975), 289-97.

This content downloaded from 130.102.42.98 on Sun, 3 Nov 2013 23:37:17 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

sondheim's piano sonata 291

Example 29. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 74-5.

Meno mosso (J = 104)

Example 30. Sondheim, Piano Sonata in C major, third movement, bars 90-1.

intrrtfyrTffrfPf tE

r-rf-?*-*?

w staccato

=F*

%e- =*t=* s

e *$fc. %%b.