Solar PV Solutions for Academic Campuses

Transcript of Solar PV Solutions for Academic Campuses

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic

Campuses in IndiaA white paper

Chetan S. Solanki Department of Energy Science and Engineering

Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IIT Bombay)

October 2010

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 2

Contents

1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 4

2. Solar Radiation Map of India ........................................................................................................... 5

2.1 Peak hours of solar radiation ................................................................................................. 6

2.2 Horizontal surface and tilted surface .................................................................................... 7

3. Solar PV technologies: Converting light to electricity ....................................................................... 7

3.1 Efficiency of PV modules of different technologies ............................................................ 10

3.2 Rated power of PV modules ................................................................................................ 10

3.3 Cost of PV modules of different technologies ..................................................................... 11

4. Per unit area PV Electricity Generation Potential .......................................................................... 11

4.1 Efficiency of PV module ........................................................................................................ 12

4.2 Per unit area electricity generation from PV modules ........................................................ 13

4.3 Daily solar radiation data ..................................................................................................... 13

4.4 Optimum tilt of PV modules – permanently fixed............................................................... 14

4.5 Optimum tilt of PV modules – seasonally fixed ................................................................... 15

4.6 Example calculations: PV electricity for three story academic building .............................. 16

5. PV system configurations .............................................................................................................. 17

5.1 Possible PV system configuration for academic campuses ................................................. 18

5.2 Commonly used PV system configurations ......................................................................... 19

5.3 Designing a PV system ......................................................................................................... 20

5.4 Example calculations for standalone PV system design ........................................................ 21

5.5 Typical Cost of PV system components ............................................................................... 23

6. Spaces for PV installations in academic campus ............................................................................ 23

6.1 Installation on building roof tops & sun shades .................................................................. 24

6.2 Solar PV Installation on parking lots/path ways .................................................................. 25

6.3 Solar PV installations on ground .......................................................................................... 25

7. Cost of solar PV electricity ............................................................................................................. 26

7.1 Calculating Life Cycle Cost ................................................................................................... 26

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 3

7.2 Comparison of LCC of Solar, Diesel and Grid electricity ...................................................... 28

8. Energy efficiency is recommended ................................................................................................ 29

8.1 Energy efficiency of buildings ............................................................................................... 29

8.2 Energy efficiency of electrical loads ..................................................................................... 30

8.3 Energy efficiency of users ..................................................................................................... 30

9. Subsidies for installing solar PV systems ....................................................................................... 30

9.1 Subsidy for rooftop PV systems ........................................................................................... 31

9.2 Interest rate subsidies ......................................................................................................... 32

10. Recommendations for use of Solar PV electricity .......................................................................... 33

Appendix: Monthly average daily solar radiation data of various cities of India; Global (on horizontal

surface), diffused (on horizontal surface) and Global (on surface tilted to latitude of location)

represented in kWh/m2‐day………………………………………………………………………………………………………………35

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 4

Solar PV Energy for Academic Campuses in India A White Paper

Chetan S. Solanki

Department of Energy Science and Engineering

IIT Bombay

1. Introduction Electricity from renewable energy (RE) sources is increasingly been seen as the viable solution for energy

deficiency, energy security and for social development. Among the many RE technologies and sources,

electricity produced directly from the sun using solar photovoltaic (SPV) technology is gaining interest

from government and investments from private enterprises.

Historically, it has been about 50 years since the first operational silicon solar cell was demonstrated.

However, the last 15 years have seen large improvements in the technology, with the best confirmed

cell efficiency being over 24%. The main drivers have improved electrical and optical design of the cells.

Improvements in the first area include improved passivation of contact and surface regions of the cells

and a reduction in the volume of heavily doped material within the cell. Optically, reduced reflection

and improved trapping of the light within the cell have had a large impact. These features have

increased silicon cell efficiency to a confirmed value of 24.7%. Together with technical progress there is

support from the government for solar PV technologies around the world. Overall effect is significant

growth of the PV technology. Currently the world annual production is over 10,000 MW. The solar PV

technologies are now increasingly seen as major electricity source for Indian scenario. The

announcement of Jawaharlal Nehru National Solar Mission confirms this, which target to install about

10,000 MW of solar PV modules in India by 2022.

On a practical level, the peak of solar electricity generation correlates with the consumption almost

perfectly. The main reason for not having to look at SPV technology so seriously earlier was because of

its high initial cost of installation. The cost is still formidable, but the alternative is to use diesel based

electricity to cover for the peak shortages. With rising diesel costs, worrisome suppliers and dwindling

global supplies, solar electricity from SPV has just turned competitive to diesel. The next target in

making solar PV widely acceptable is making electricity from it as cheap as that from coal. Though there

is still a long way to go, the trend is unmistakable. SPV is here to stay and the faster we accept its utility,

the easier it will be to solve much of our current concerns.

Overall considering the concerns about rising electricity cost, increased concern for climate change and

need to find alternative energy solutions, and with considerable government support, solar PV

technology is increasingly seen as viable option for our current and future energy supply.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 5

Academic campuses are ideal places for use of solar PV modules for the following reasons:

1. Most of the operation of academic campuses takes place in the day time, which is in

synchronous with the availability of sun light. With this condition the expensive battery storage

is minimized.

2. Academic campuses do not have significant heavy loads like ACs, meaning that the required

power density is low. It is easier to generate smaller power density with solar PV solutions.

3. Use of solar PV modules in campus will sensitize young minds on importance of renewable

energy technologies who would become future scientist, academicians or policy makers.

This document describes the solar PV potential, particularly for academic institutions in India. The

Section 2 describes the available solar radiation at various parts of the country, followed by Section 3

giving the commercially available solar PV technologies for electricity generation. Available surface area

in academic campuses may be a limitation. Therefore Section 4 describes the per unit area electricity

generation potential of PV technologies. Configuration of PV systems and system design is explained in

Section 5. Several spaces can be used to install solar PV modules in academic environment; the

possibilities are described in Section 6. The cost of electricity generated using solar PV modules is

described in section 7 while Section 8 looks at possibility of minimizing energy consumption in order to

reduce the overall cost of PV systems. At the end various subsidy scheme of government for promoting

use of solar PV technology is described and recommendations were made for using solar PV electricity in

academic campuses in India.

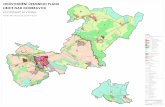

2. Solar Radiation Map of India

Electricity from the SPV is dependent on the amount of sunlight falling on the solar panels. The longer

the hours of sunlight falling on them and the greater the amount of sunlight falling on them the better it

is for electricity generation. Solar insolation in a given location is given by the unit kWh/m2‐day. In India,

the average solar insolation varies between 4 – 7 kWh/m2‐day. This solar radiation referred as global

solar radiation and it consist of direct and diffuse solar radiation (due to cloud cover, dust, etc) reaching

at a point on earth. What it means is that every day the amount of solar energy falling on 1 m2 area in

India is about 4 – 7 units. Given India’s location in the equatorial belt, it is abundant sunshine. Also the

fact that we have between 250 and 300 days of clear sunny days, gives the location year round reliable

source of energy. Given the above figures the annual solar radiation falling on 1 m2 area in a given year

is between 1600 and 2200 kWh. (To give a perspective, the solar industry leader, Germany’s annual

global solar radiation is between 950 and 1350 kWh/m2‐day.) For India that translates to about 6000

million GWh. That’s a huge potential to tap.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 6

Fig: Solar radiation map of India

It can be observed from the solar radiation map of India that although the highest annual global

radiation is received in Rajasthan and northern Gujarat, other regions also receive fairly large amounts

of radiation as compared to many parts of the world including Japan, Europe and the US where

development and deployment of solar technologies is maximum.

2.1 Peak hours of solar radiation

The solar cell efficiency and module output power is specified for W/m2 of radiation intensity and at 25

degree centigrade of cell temperature. This condition is known as standard test condition (STC).

Normally the solar radiation intensity varies from morning to afternoon to sunset. A typical variation of

solar radiation intensity as a function of time in hours is given in Fig. below. One can notice from the

figure that the intensity of global radiation varies from 0 W/m2 at the sunrise and sunset to about 0.9

kW/m2 at the noon time. The integration of the solar intensity curve, gives solar insolation falling at a

unit area over a day and therefore the unit of solar insolation (loosely also referred as solar radiation) is

Watt‐hour/m2‐time, for instance Wh/m2‐day or kWh/m2‐day. It is mentioned in the previous paragraph

that the annual solar insolation in India varies between 4 – 7 kWh/m2‐day or 1460 to 2555 kWh/m2‐year.

Since the solar cells and modules are characterized for 1000 W/m2 or 1kW/m2 of solar radiation

intensity, it is useful to represent the daily or annual solar radiation data in terms of ‘number of hours’

of 1000 W/m2. For instance, a 5 kWh/m2‐day of global solar insolation is equivalent of 5 hours of 1000

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 7

W/m2 of solar intensity. This concept is demonstrated in Fig. below and very useful in estimating the

amount of energy generated from a given PV module. In the Fig. below the area of the global radiation

curve and the dotted rectangle should be equal.

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

6 8 10 12 14 16 18Hours

Rad

iatio

n (k

W/m

2)

Fig: Daily variation in global and diffuse radiation intensity at a given location and equivalent ‘number of

hours’ of 1000 W/m2 (for which solar cells and modules are characterized). Typically diffuse radiation is

about 10 to 20% of global radiation in India for a clear sky. During monsoon or cloudy sky conditions

diffuse radiation is about 50 to 80% of the global radiation.

2.2 Horizontal surface and tilted surface

The global solar radiation data are typically represented as amount of solar radiation received on a

horizontal surface at a given location. In order to intercept more solar radiation, the solar PV modules

are mounted at an angle to horizontal plane. Therefore, sometimes, it is useful to know the global solar

radiation data on a tilted surface. This is discussed in detail in later sections.

3. Solar PV technologies: Converting light to electricity Solar PV is a semiconductor device which converts sunlight directly into electricity. The operation of light

to electricity conversion requires a built‐in electric field, normally obtained by making P‐N junction or P‐

i‐N junction structures. A solar PV panel or a solar PV module when exposed to sunlight generates

voltage and current at its output terminal. This voltage and current can be used for our electricity

requirements. The amount of electricity a solar PV module can generate depends on the amount of

sunlight falling on it. The higher is the intensity of the sunlight the more will be the electricity generated

from it. When no sunlight falls on a solar PV module, no electricity is generated.

The development of solar PV technologies has been taking place since 1950s. The solar cell development

was being done mainly for space applications till 1970s. After the first oil shock of 1973 the solar cell

technology has been seriously considered for terrestrial power generation applications. Since then lot of

development has occurred in cell design and cell material with an objective to increase in efficiency and

decrease in cost per Watt. There are many technologies which are still under research and some of them

5 hours

Diffuse radiation

Global

radiation

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 8

have come to a commercial stage. Among the commercial SPV technologies, wafer crystalline Si

technologies are most commonly fabricated and used.

The commercial SPV technologies can be divided in two categories:

1. Crystalline Silicon (c‐Si) wafer‐based cell technologies

2. Thin film substrate‐based cell technologies

The c‐Si wafer based technologies are divided in to mono‐crystalline, multi‐crystalline, electronic grade

Si, solar grade Si and ribbon Si. The overall scenario c‐Si wafer based technologies is shown in Figure

below.

Fig: Overview of Si based technologies. It also shows the route of thin film Si cell technologies1.

Overall thin film technologies can be divided in two categories: Si based and non‐Si based, which can

further be divided in flexible and rigid substrates. Categorizations of thin film technologies and leading

companies in various categories are given in the figure below.

1 C.S. Solanki, Solar Photovoltaics: Fundamentals, Technologies and Applications, Prentice Hall of India, 2009.

Wafer or

Raw Si in the form of SiO2

Metallurgical grade Si

High purity chlorosilanes gases

High purity electronic grade Si

Ingot pulling Block casting

Wire sawing Wire sawing

Solar cell Solar cell

Mono‐crystalline

wafer

Multi‐crystalline

wafer

Thin film

deposition

Solar cell

Sheet pulling

Laser cutting

Solar cell

Si sheets

Solar grade Si

Block casting

or sheet

pulling

Purification

Solar cell

Wafer dicing

Route‐I Route‐II Route‐III Route‐IV Route‐V

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 9

Fig: Tree of thin film technologies and leading companies.

Both Crystalline Si wafer (c‐Si) based technology and amorphous Si (a‐Si) thin film solar cell technology

makes use of Si but they are fundamentally quite different technologies. C‐Si wafers have ordered

arrangement of Si atoms while in a‐Si it is completely disordered (amorphous), which is the main reason

for different (a) solar cell structure, (b) different way of making contacts and finally (c) different

performance of the devices. C‐Si is based on p‐n junction while a‐Si is based on p‐i‐n junction. Other thin

film technologies like CdTe and CIGS have poly‐crystalline material and cells are based on p‐n junction.

Today solar PV modules of following technologies are commercially available:

Mono‐crystalline wafer‐based modules

Multi‐crystalline wafer‐based modules

Cadmium Teluride (CdTe) thin film modules

Copper Indian Gallium Selenide (CIGS) thin film modules

Amorphous Si (a‐Si) thin film modules

, Nex Power

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 10

3.1 Efficiency of PV modules of different technologies

PV modules from different technologies vary in terms of efficiency and cost per Watt. The efficiency of

cells and modules of different technologies are listed in Table below.

Technology Highest Cell Lab

Efficiency*(%)

Highest module

Efficiency*(%)

Typical commercial

module efficiency(%)

Mono c‐Si 25 22.9 14 to 16

Multi c‐Si 20.4 15.5 14 to 16

a‐Si (single junction) 9.5 8.2 5.5 to 6.5

a‐Si (double‐junction)

a‐Si/micro c‐Si

(double junction)

10.6

~14.2(unstabilized)

‐

‐

‐

8 to 10

a‐Si (triple‐junction) 13.0 10.4 ‐

CdTe 16.7 10.9 8 to 9

CIGS 19.9 13.5 10 to 12.5

*Ref: Martin A. Green, Keith Emery, Yoshihiro Hishikawa and Wilhelm Warta, Solar cell efficiency table

(version 34), Prog. In Photovoltaic: Res. Appl. 2009; 17:320–326. Efficiency measured under the global

AM1_5 spectrum (1000W/m2) at 258C (IEC 60904‐3: 2008, ASTM G‐173‐03 global) stable efficiencies.

3.2 Rated power of PV modules

The efficiency and power output of a solar cell and modules are given for light condition corresponding

to 1000 W/m2 and at 25oC temperature, known as standard test condition (STC). The rated power of a

cell and module is referred as peak power or Wp. The peak power of PV module changes with change in

falling solar radiation and temperature of the cell under real life conditions. Typically one does not get

the condition corresponding to STC. Solar radiation is normally lower than the STC condition and cell

temperature is normally higher than the STC condition, both of these have effect of decreasing power

output from the PV module.

The conditions specified in the STC does not occur for most of the time and locations. This happens

because of two reasons; the real solar irradiation is normally less than 1000 W/m2 and the module

temperature under real operation is more than the STC specified temperature of 25oC. Both of these

reasons result in lower module power output than the expected under the STC condition. Thus, in order

to have more realistic figure for the possible power output from a PV module, the performance of the

modules is described in two other test conditions; standard operating conditions (SOC) and nominal

operating conditions (NOC). Both of these use a different concept of temperature, called as nominal

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 11

operating cell temperature (NOCT). The NOCT is defined as the temperature reached by a cell in open

circuited module under following conditions:

‐ Irradiation: 800 W/m2,

‐ Ambient temperature: 20oC

‐ Wind speed: 1 m/s

‐ Mounting: open back side

The NOCT can be used to give more realistic cell temperature of the module under operating conditions.

The NOCT lies usually between 42 to 50oC. Under different ambient temperature and solar radiation the

NOCT will change. In India, since ambient temperature is always quite higher than 20oC considered in

NOC, therefore actual cell temperature lies between 55 to 70oC.

Table: Comparison of test condition under which PV module characteristics are described.

Conditions STC

(Standard test

condition)

SOC

(Standard operating

condition)

NOC

(Nominal operating

condition)

Irradiation (W/m2) 1000 1000 800

Temperature (oC) 25 NOCT (42 to 50oC) NOCT (42 to 50oC)

Rated power (Wp) 100 (reference) 91 to 94 72 to 75

Since the NOC conditions are more common in real life situations, therefore for PV module power rating

under NOC conditions (or prevailing conditions) should be considered. And the rated power under NOC

conditions is smaller than rated power under STC conditions. But note that in most designs the STC

rated power of PV modules is considered, which is then discounted in terms of efficiency to consider

losses for higher operating cell temperature.

3.3 Cost of PV modules of different technologies

The cost of solar PV technologies is stated in terms of Rs per Wp. The cost of PV modules varies between

75 Rs/Wp to 125 Rs/Wp. This variation is due to the technology and also due to the volume of purchase.

Normally for higher volume purchase, like several 100 kWp or few MWp, the cost of c‐Si based PV

modules was between 90 to 110 Rs/Wp in Sep. 2010.

4. Per unit area PV Electricity Generation Potential

In the last section it is mentioned that the average solar radiation in India is quite high. But the question

how much of that radiation can be extracted into electricity from SPV module covering certain area. The

calculation is very simply dependent on the efficiency of the SPV used and available solar insolation at a

given location. If high efficiency modules are used, more of the solar energy can be converted to

electricity. Lesser efficiency would mean less electricity conversion.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 12

Depending on the kind of technology, efficiencies vary between 8% for thin film SPV and 16% for mono‐

crystalline SPV. It should be, however, noted that higher efficiencies mean greater generation of

electricity for a given unit area. A 100 watt solar module will generate the same amount of electricity in

a given locality no matter how efficient or inefficient it is. The only thing that may differ is the size of the

100 Wp module. A less efficient module will be bigger than a high efficiency module. A PV module of 1

meter square area with efficiency of 14% and 8 % would generate 140 Watt and 80 Watt respectively

under standard test condition (1000 W/m2 and at 25oC).

4.1 Efficiency of PV module

Efficiency of PV modules is calculated as follows:

A commercially available module has the following given parameters:

The peak power rating of the module (Wp)

The area of the module (m2)

Dividing the peak power rating by t he area of the module, we get Wp/m2. Since the modules are rated

at STC of 1000 W/m2, the efficiency of the module can be written as:

%100*/1000

/2

2

mW

mWEfficiency p

For instance a 200 Wp and a 230 Wp Moser Baer crystalline silicon solar module has the L x W of 1661

mm x 991 mm. Similarly a 340 Wp and 380 Wp thin film solar module has the dimension of 2600 mm x

2200 mm. The estimated solar PV module efficiencies are given in Table below.

Table: Estimated efficiencies of PV module

Parameters 200 Wp c‐Si 230 Wp c‐Si 340 Wp thin film 380 Wp thin film

Type of Module Crystalline Silicon Thin Film

Power Rating 200 230 340 380

Area (m2) 1.64 5.72

Wp/m2 121.2 139.4 59.4 66.4

Efficiency 12.1% 13.9% 5.9% 6.6%

As can be seen from the above example, the crystalline modules have higher efficiency than thin film

ones. The information about efficiency of PV modules is useful in determining the total area of PV

modules required to generate given amount of energy.

Alternatively a 13.9% efficient SPV of 200 Wp will have the area of 1.43 m2. This is calculated by dividing

200 Wp by the efficiency. In this instance the area of the module can be calculated as follows:

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 13

22

/)(

mW

WmArea

p

p

4.2 Per unit area electricity generation from PV modules

From the efficiency of the modules one can then calculate how much electricity can be generated in a

given area. Suppose the location has an average daily solar radiation of 5.5 kWh/m2‐day, then using the

various efficiencies one can determine the electricity generated from the modules.

Electricity generated from individual panel of a given power rating is the product of the efficiency of PV

module and average daily solar radiation.

)//(.*.mod.)//( 22 daymkWhradiationdailyAveofEffdaymkWhGeneratedyElectricit

Table: Estimated electricity generation on per unit area basis from PV modules of different efficiencies.

Parameters c‐Si Low c‐Si High Thin Low Thin High

Efficiency 12.1% 13.9% 5.9% 6.6%

Average Daily Solar Radiation

(kWh/m2‐day) 5.5 ( or 5.5 hours of 1000 W/m2)

Electricity generated

(kWh/m2‐day) 0.66 0.76 0.32 0.36

Thus from a PV module data sheet its efficiency can be estimated and from a given global solar radiation

data, per unit area electricity (on daily, monthly or yearly basis) can be estimated.

4.3 Daily solar radiation data

Global solar radiation data are normally available for main locations in the form of daily average.

Multiplying the number of days in a month to daily average global solar radiation data one will get

monthly global solar radiation data. As an example monthly averaged daily global solar radiation for

Hyderabad is given in Table below. For many other locations across India the monthly averaged daily

global radiation data are given in Appendix.

Table: Monthly averaged daily global solar radiation on horizontal surface and at surface tilted at latitude angle for

Hyderabad.

Month Average Daily Global Solar

Radiation (Horizontal)

Average Daily Global Solar

Radiation (Latitude)

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 14

January 5.5 6.7

February 6.2 7.1

March 6.5 6.8

April 6.9 6.7

May 6.9 6.4

June 5.8 5.3

July 4.9 4.6

August 5.2 5.0

September 5.2 5.2

October 5.8 6.3

November 5.4 6.4

December 5.1 6.3

AVERAGE 5.78 6.06

The figures here represent the energy falling on the surface during the day or the number of hours when

the radiation is 1000 W/m2. Note in the above Table that that during the summer the radiation on

horizontal surface is greater than that of the radiation on the latitudinal tilted surface.

4.4 Optimum tilt of PV modules – permanently fixed

In order to maximize the interception of solar radiation, and hence maximize the generation of solar

radiation, the solar PV modules should be kept perpendicular to the sun rays. Since the position of the

sun is changing throughout the day, the position of the PV modules should also be changing throughout

the day, i.e. sun tracking is required. The precise tracking of the sun, in most cases, is not possible due to

the additional cost of infrastructure required for tracking. Also, it requires maintenance. Therefore fixed

mounting of solar PV modules, over certain period, months or even year, is advised and preferred

option.

The question is how the collector should be optimally oriented for capturing maximum possible

sunlight? For a clear day, the intensity of solar radiation at a given location is symmetrical around the

solar noon time of the location. Also the radiation intensity is maximum at noon time. Therefore the

solar PV modules are oriented to maximize solar radiation interception at noon time. It can be shown

that if the PV modules are to be fixed throughout the year, at a fixed angle, the optimum tilt of solar PV

modules should be equivalent to the latitude angle of the location. Also, if the modules installation is

done in the Northern hemisphere the orientation should be South facing and if the PV modules are

being installed in Southern hemisphere then the PV modules should be installed North facing.

Thus, if PV modules are integrated as part of roof of a building in academic campus, the roof should

have a tilt angle, equivalent to latitude angle of the location and in India the roof should be south facing.

The latitude angle of Hyderabad is 17.37o North and hence the buildings on which solar PV modules are

to be mounted should have 17.37o tilt, and the roof should be facing South.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 15

4.5 Optimum tilt of PV modules – seasonally fixed

It can be noted from the Table of daily global solar radiation for Hyderabad that during the summer the

radiation on horizontal surface is greater than that of the radiation on the latitudinal tilted surface. Thus,

tilt of PV modules in a given season can affect the energy generated from it. This knowledge can be used

to optimize the electricity generation for a given season.

In the previous section it has been discussed that a fixed solar collector installed in the Northern

hemisphere should be facing South and should be inclined to an angle equal to the latitude of the

location. But adjustment of solar PV modules inclination few times a year can enhance the energy

collection over the year, by enhancing the intercepted radiation. The PV module inclination adjustment

can also improve the system performance for a given season. For instance, an academic building will

require larger energy for running fan in summer. Or if solar PV modules are installed for a ski resort, it

would be desirable that the collector perform better in winter.

The optimized tilt angle of solar PV modules in winter season should be equal to latitude angle+15o and

for the summer it should be latitude angle‐15o. The relative gain in the electricity production of a PV

module when it is mounted to latitude15o as compared to its performance when it is mounted at the

latitude angle is shown in Fig. below. Note that the graph is only an indicative relative gain. Different

locations will have different relative gain as it will depend on the local weather, percentage of diffuse

radiation and seasonal change of the weather.

Fig.: Relative collector performance as a function of collector tilt angle

Periodically changing the tilt of the PV modules requires additional structural arrangement that allows

change in tilt, manually or automatic. This can add to the cost but results in additional energy

generation. In general, 15 to 25% additional energy (as compared to permanently fixed mounted PV

panels) can be generated with 5 to 10% higher life cycle cost.

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

1.2

1.4

Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun July Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec

Rel

ativ

e en

ergy

pro

duct

ion

Latitude

Latitude + 15o

Latitude ‐ 15o

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 16

4.6 Example calculations: PV electricity for three story academic building

Based on the information discussed so far in this section, it is now possible to estimate whether there is

enough space or not in a building to supply all its electricity requirement using solar PV modules. Other

than the cost of PV system, there is limitation of availability of open area, like terrace, to install solar PV

modules. The calculations given in Table below are based on certain assumption for the electricity

requirement of a building and terrace area availability. First order calculations suggests that academic

buildings, tall up to three floors, have sufficient space at the terrace to fulfill most if not all of its

electricity requirement, provided there is no AC load.

Table: Examples calculations for satisfying electricity needs of a academic building using PV modules

Total floor area of building

Description Quantity Units

No of floors in building 3

Area per floor (this is taken as example, calculations for any other area would be valid as well) 1000 Sq ft

Total floor area 3000 Sq ft

Estimation of load

Estimated Load per unit area of the building 100 Sq ft

Item No. Wattage Hour of usage per day

Lights (assuming efficient lights) 2 50 9 900 Wh

Fans (assuming efficient fan) 1 50 9 450 Wh

Computers (assuming one computer in every 200 sq ft) 1 50 4 200 Wh

Total daily electricity required 1550 Wh

Total daily energy required for whole building (all three floors) 46500 Wh

46.5 kWh

Available space of PV installation on roof 70% of total floor area

Total available space for PV module installations 700 Sq ft

63.6 Sq meter

Total possible installation of PV modules (in terms of Watts)

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 17

Solar radiation intensity (Standard Test Condition) 1000 W/m2

PV module efficiency 15%

Wattage of PV modules per sq meter 150

Total wattage of PV modules that can be installed on roof 9545 Watt

Daily generation of electricity from PV modules

daily available solar radiation 5 kWh

5 Hours of 1000 W/m2

Energy that can be generated per day using PV modules 47727.3 Wh

47.7 kWh

Comments: One can see from the above calculations that even for three story building there is

sufficient generation of electricity from PV modules to full fill all the electricity requirements of the

building. Please note that no PV system losses are taken in calculations, which invariably are there

up to 15 to 20%. In summary, one to three story buildings always have sufficient roof area to full fill

most of its electricity requirements.

This is only example calculations, proper calculations should be done for each building. The steps for

designing solar PV systems for a given electricity requirement is given in section 5.

However one should note that several assumptions, which are very reasonable, are made in this

calculation. The actual electricity requirement can be higher or lower, the actual roof area available

for PV module installations could be higher or lower, the actual amount of solar radiation available

at a given location could be higher or lower.

5. PV system configurations

The PV systems are designed to supply power to electrical loads. The load may be of DC or AC type and

depending upon the application, the load may require power during the day time only or during the

night time only or even for 24 hours a day. Since a PV panel generates power only during sunshine

hours, some energy storage arrangement is required to power the load during the non‐sunshine hours.

The load can be a DC or an AC load. This energy storage is usually accomplished through batteries.

During the non‐sunshine hours, the load may also be powered by auxiliary power sources such as diesel

generator, wind generator or by connecting the PV system to the grid or some combination of these

auxiliary sources.

PV systems can be broadly divided into the following three categories:

1. Standalone PV systems

2. Grid connected PV systems and

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 18

3. Hybrid PV systems

A standalone system is the one which is not connected to the power grid. In contrast, the PV systems

connected to the grid are called grid connected PV systems. Hybrid PV systems could be standalone or

grid connected type, but have at least one more source other than the PV.

The primary difference between the standalone and grid connected systems comes from the energy

storage feature, which is a direct consequence of their connection (or absence of connection) with the

grid. While the standalone PV systems usually have a provision for energy storage, the grid connected

PV systems have none or rather they don’t need one. The excess or deficit energy produced by the PV

source in grid connected systems (difference of energy produced by the PV source and the energy

required by the load) is supplied to the grid or drawn from the grid. As a standalone PV system is not

connected to the grid, it must have battery support or an auxiliary source to supplement the load

requirements during the night hours or otherwise.

Be it the standalone system or the grid connected system, other sources of power (other than the PV as

the main source) may also be connected to them for auxiliary support and better reliability. For

instance, a standalone PV system can also have a wind generator connected to it or it can have two

power sources, a wind generator and/or a diesel generator, connected to it. The same is true for the grid

connected systems. Whenever there is more than one type of power sources connected in a system, the

configuration is known as hybrid system. A hybrid system with PV as the main source, is called a hybrid

PV system. Factors such as resource (solar, wind, grid) availability, initial cost of the system, criticality of

the load, etc. influence the decision as to whether or not to have a hybrid system and if yes, what

configuration? For instance, a PV‐wind hybrid configuration can be installed when both solar and wind

resources, at a given location, are abundantly available. Similarly, when the amount of PV power

installed is not adequate to meet the load demand (say due to cost factor), a diesel generator or another

renewable energy (RE) generator can be installed along with the PV source.

5.1 Possible PV system configuration for academic campuses

A possible PV system configuration, incorporating various sources of electricity like PV modules, grid,

and diesel/Wind generator is shown in the Fig. below. It should be noted that it is optional to connect

one or more sources of electricity in the system. The system can only run on Solar PV electricity or it can

also be coupled with grid electricity. Many times, when grid electricity connected is not available or not

reliable, then it is advisable to have solar PV with diesel generator, wherein diesel generator may be

used for emergency conditions when there is not enough sun light, like in rainy season.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 19

Fig: Possible configuration of solar PV system with option of connecting the system with grid or diesel or

wind generator.

5.2 Commonly used PV system configurations

The current trend in usage of PV systems is in providing day time electricity needs and supplying

electricity to the grid. This usually reduces the cost of storage for night time application and manages to

solve the peak time energy shortage. These are grid connected systems without any battery storage. As

per the prevailing policies, the gird connection in India is possible for power plants of 1MW and larger

capacities. For connecting PV systems of smaller sizes, less than MW, institution are required to have

arrangement with state electricity board, regulatory boards.

In a number of industrial and commercial locations SPV is replacing diesel as the preferred source of

electricity generation. While in industrial locations the quantum of power and therefore energy

requirement is very high, the size of PV systems tends to be large as well. So most of the time the PV

plant is setup in roof‐top as well as over land dedicated for SPV power plant. These systems are almost

always grid connected to switch seamlessly between SPV electricity when it is available and grid

electricity when the sun is unavailable, such as during monsoons.

In academic locations the need for electricity is usually to power office equipments and basic needs such

as lighting and ventilation. This is an example of captive power plants where PV plants are installed to

satisfy the electricity needs of campus only. In most instances the SPV is installed over building roof‐

tops. In absence power source, other than PV, battery storage is required.

Electronic

Controller

AC

Load DC‐AC

Converter

DC

Load

PV

Panel

Grid

Diesel /wind Generator

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 20

5.3 Designing a PV system

Design of grid connected system:

A grid connected system will not have any battery back up as the grid itself acts as medium to store

energy. Therefore one need to put enough solar PV modules to fulfill daily energy requirements. Since

the PV systems are connected to grid, one can install less than the required PV modules or more than

the required PV modules. The amount of PV modules to install may then be govern by the availability of

money, availability of roof top area, upper limit set by policies, etc.

For instance, if you install 2 kWp of PV modules (normally would take about 15 square meter of roof

area) on your roof and you daily solar insolation in your area is 5 kWh/m2‐day, then PV modules would

be generating 10 kWh or 10 units of electricity every day. In order to connect a PV system to the grid,

one requires electronic components like Maximum Power Point Tracker, DC to DC converter and an

Inverter. All these components may come as single unit, as an inverter for grid connection. Efficiency of

such electronics is over 80% at small power level (few kW) inverter, but the large power (several

hundred kW) grid connected inverter would have efficiency above 92%. One must consider the electrical

losses in electronics required for grid connection to estimate what is the actual energy fed in to the grid.

Design standalone PV system

A standalone PV systems are designed to full fill all the electrical energy requirement of a premises,

wherein the load can run during day time or night time. In such systems, a battery bank is used to store

the electricity. A PV system design requires the estimation of load (in terms of daily energy), estimation

of battery in a PV system and estimation of size of PV modules, etc.

The design of PV system is normally done in three steps:

Step 1: estimation of daily electrical energy required

Step 2: Estimation of battery requirement

Step 3‐ Estimation of PV module requirements

In order to estimate the electrical load, one must know the power ratings of various appliances used in

institute and the number of hours of daily usage of each appliances. Table below provides the

appliances along with their power rating and the approximate hours they are used.

Table: Power ratings of various appliances used in academic institutions

Appliance Power Rating (Watt)

Tubelights 40

CFLs 8 – 28

Ceiling Fans 55 – 85

Wall Fans 65 – 100

Air‐Condition Systems 1000 – 5000

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 21

Appliance Power Rating (Watt)

Laptops 80 – 100

PCs 250 – 300

TV 150 – 250

Printers 300 – 500

Projectors 1000 – 3000

Water Pumps 350 – 3500

5.4 Example calculations for standalone PV system design

Let us design a PV system to power a typical academic establishment with the following loads. They are

to operate between 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM.

Table: Estimation of daily electrical energy requirements

Load Power Rating

(Watt)

Usage in hours per

day

No. of Units Electricity

(Wh)

Tubelights 40 9 6 2160

Fans 80 9 6 4320

CRT PCs 300 8 6 14400

Printer 500 2 1 1000

920 Watt

Total daily electricity demanded (Wh) 21880

Total daily electricity demanded (kWh) 21.88

Solution: Daily energy required is 21.88 units or 21.88 kWh. The location is in Hyderabad. The average

annual global solar radiation is 5.78 kWh/m2‐day.

Simplistically, the panels required can be found by:

)(

)()(

hoursequivalentRadiationSolarGlobal

kWhNeededyElectricitkWSPV

In this case, 21.88 kWh divided by 5.78 hours = 3.78 kW

However, there are other additional components that are needed. Batteries to provide for non‐peak

solar hours or when there is no sunlight. Usage of inverters, batteries and other electronics bring their

own inefficiencies. An SPV system has to be designed keeping these factors in the picture. Table below

indicates the steps to design an SPV system.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 22

Table: Design steps for estimating the required size of batteries and PV modules for given daily electrical

energy needs

Steps Description Values

Calculating the

electricity needed

21.88 kWh

Inverter Rating Slightly greater than the

total load rating

1 kW

Inverter Efficiency 85%

Energy to the load and

inverter

25.74

Sizing of batteries

Estimating the energy

that needs to be stored

33% This is an assumption, if

loads run in the night

hours then battery

storage capacity may be

much higher (in worst

case 100%).

Battery Efficiency 85%

Energy that needs to be

stored

10 kWh

Battery Voltage 12V

Battery Ampere‐Hr

capacity

840 Ah

Battery Depth of

Discharge

60%

Actual Battery capacity 1400 Ah

Sizing of PV modules

Energy needed during

the day

25.74 kWh

Total system efficiency 80%

PV Panel operating

performance

85%

Average global solar

radiation

5.78 hours

Actual PV size 6.54 kW

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 23

Thus PV modules of 6.54 kWp are required to provide the daily electricity of about 21.88 kWh in an

standalone PV system.

The battery acts as a storage when the office functions during the non‐peak sunshine hours such as early

morning and late in the evening. The excess electricity generated during noon time is stored in the

battery which is used when the intensity is less. The figure of 33% is arbitrary figure taken here. Ideally it

should be arrived after having analyzed the load pattern during the day. Battery size would double if 2

days of autonomy is needed. Autonomy means when the system can provide reliable electricity when

the sun is down, such as during monsoon.

5.5 Typical Cost of PV system components

The Table below gives the typical cost of various PV components that are used in PV system, both for

grid and off‐grid systems.

Table: Typical cost of PV systems

Component Specified in terms of

“unit”

Available in range of

“units”

Typical cost

Solar PV modules Peak wattage, Wp 40 Wp to 300 Wp 90 to110 Rs per Wp

Battery Ah capacity and terminal

Voltage

20 Ah to several

hundred Ah, 12 V

60 to 80 Rs / Ah @ 12 V

Inverter (off‐grid) kW 1 to 25 kW 16000 to 2000 Rs per 5

kW

MPPT (off‐grid) Input DC voltage, current

handling capacity

12 to 72 Volt, 10 A to

50 A

16000 to 20000 Rs for 24

V, 30 A

Inverter (grid‐

connected),

kW 1 to 10 kW

100 kW

250 kW

30,000 Rs Per kW

15000 Rs per kW

10000 Rs per kW

Charge controller (off‐

grid)

Input DC voltage, current

handling capacity

12 to 72 Volt, 10 A to

50 A

10000 to 12000 Rs for 24

V, 30 A

Fabrication cost of PV

system (supporting

frames, wires, etc.)

Rs per Watt of system

capacity

10 Rs per Watt

6. Spaces for PV installations in academic campus

There are several locations in the academic campus that can be utilized for installation of solar PV

modules. Since most of the buildings in a given campus are of same height, building terraces offer

excellent locations for SPV installations. Parking roof‐tops, PV shelters for open restaurants with

campus, unused land parcels can all be possible locations for PV installation.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 24

Thus the possible spaces for installation of PV modules could include:

‐ Roof tops of buildings, both academic and residential

‐ Roof tops of canteen

‐ Roofs of parking area and path ways

‐ Any other open area

If the planning for use of solar PV modules is done in advance the solar PV modules themselves can be

used as roof material. Use of solar PV modules as roof material has potential of saving the cost by saving

the construction materials for roof tops. This is particularly suitable for spaces like roof tops of parking

areas, roof top of sports complex, canteen etc.

Some of the examples of use of Solar PV modules for various applications are discussed here.

6.1 Installation on building roof tops & sun shades

Roof tops of buildings are good places to install PV modules. Normally the roof tops are not used for

useful purposes and available for use. Installing PV modules at the rooftop will have additional

advantage of reducing the heat gain of the building from the top, which would reduce the cooling

requirement or increase the comfort level.

For one to three story buildings (e.g. department buildings, households etc.) there is always enough roof

top space to generate electricity for supplying the complete load of the building, if air conditioning load

is not there (refer to section 4).

Fig: Solar PV modules on roof tops

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 25

Fig: Solar PV modules as Sun shades

6.2 Solar PV Installation on parking lots/path ways

Parking lots are one of the ideal spaces for installation of PV modules, specially when PV modules

themselves are used as roofing material. Image below depicts the use of solar PV modules on a very

large size parking lot.

6.3 Solar PV installations on ground

If there is not sufficient space available on the roof tops and parking lots, then solar PV modules can be

installed on ground. It requires dedicated space for installation of PV modules. Image below depicts the

installation of PV modules on ground.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 26

Since India is in the northern hemisphere, only south facing panels can have maximum solar radiation.

The most important factor for SPV location selection is shadow‐free eastern, southern and western

sides. Trees shades and building shadows should be accounted for ideal SPV placement.

7. Cost of solar PV electricity The cost of installation of SPV is formidable because of the fact that all the future expenses are incurred

at the beginning of the project. Since all future expenses mainly involve only nominal operation and

maintenance and fractional replacement expenses. In most cases the investor is discouraged by the

possibility of spending so much before the solar PV project is implemented.

In this section basic calculations are given in order to find out the cost of electricity generated from PV

modules and other resources like diesel generator so that the comparison between solar PV electricity

and other sources can be made.

7.1 Calculating Life Cycle Cost

While calculating the cost of generating per unit of solar electricity, we use the concept of Lifecycle Cost

of Electricity (LCOE). LCOE is the ratio of Total Lifecycle Cost (TLCC) and the Total Lifetime Energy

Production (TLEP). TLCC calculates the present worth of all the expenses incurred by the system during

its lifetime. It includes costs such as initial cost of installment, recurring expenses such as operation and

maintenance and replacement expenses for battery, inverter and balance of systems. TLEP sums the

total electricity generated during the life of the plant. The present worth of all the electricity generated

in 25 years of the life of the system is calculated discounted at some prevailing rate. It should be noted

that the amount of electricity generated falls steadily during the life of the system. And as the value of

investment changes as time changes, so does the value of electricity generated.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 27

N

n

nradationSystemkWhInitial

TLCCelecricityofLCC

1

])deg1(*[

Where is N is life of system in years.

TLCC can be calculated as follows:

TLCC = LCC (Initial investments + Recurring Cost + Replacement cost)

Thus in order to find out the TLCC one needs to know (i) initial investments, (ii) recurring cost (the cost

of maintenance) and (iii) replacement cost incurred for the operation of system during its lifetime.

(i) Initial investments mean the cost of system is estimated at the time of installation. This is nothing but

the sum of all costs of the PV system components.

(ii) The recurring costs are given as:

N

RateDiscount

Inflation

InlationrateDiscount

InflationOMCostcurringLCC

1

1*

1*Re

Here the OM is nothing but Operation and Maintenance cost of the system at today’s rate.

(iii) LCC Replacement Costs are given as:

yR

RateDiscont

InflationCostItemCostplacementLCC

1

11*Re

Where Ry = Replacement year

Generally discount rate is greater than the inflation rate. Complex formula can be formed around tax,

depreciation and debt components.

For calculating the LCC of Diesel based system, one must calculate the LCC of diesel annual expense,

diesel generator replacement, its respective O&M and initial expenses if any.

N

teDiscountRa

EscFuel

EscalFuelRateDiscount

EscalationFuelCostDieselAnnDieselofLCC

1

.11*

.

1*.

Here N is life of system during which the operation is considered.

Diesel based systems will face replacement expenses in generator and parts replacements and recurring

expenses in operation and maintenance. Environmental costs are difficult to calculate but a very

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 28

conspicuous component of costs; they are not included. Adding them will give the LCC of diesel based

system.

Similarly, the LCC of grid electricity can be calculated, only the annual diesel expense would be replaced

by annual electricity expenses. Since there are no other additional expenses in terms of recurring or

replacement costs, the LCC of grid electricity will be the lowest.

7.2 Comparison of LCC of Solar, Diesel and Grid electricity

We shall now compare the cost of generating one unit of electricity from these various options. Table

below describes the assumptions and the LCC.

Table: Comparison of Life Cycle Cost of Solar, diesel and grid electricity for the load of about 3 kW.

Parameter Solar Diesel Grid Electricity

Interest Rate 14.29% 14.29% ‐

Discount Rate 16.6% 16.6% ‐

General Inflation 5% ‐ ‐

Fuel Inflation ‐ 10% ‐

Electricity Inflation ‐ ‐ 10%

Unit Price Rs. 100/W Rs. 38/litre Rs. 5/kWh

No. of Years 25 25 25

Units generated in a

year

1,80,161 1,99,655 1,99,655

Cost of Electricity

(Rs/kWh)

Rs. 13.94/kWh Rs. 18.77/kWh Rs. 3 to 5 / kWh (domestic)

Rs. 6 to 8 / kWh (commercial)

Rs. 8 to 15 / kWh (industrial)

Rs. 14 to 15 / kWh for grid+diesel combined option

From the Table it is obvious that the grid electricity when available will have to be utilized. But between

solar and diesel, solar has already proved competitive. Going forward, assuming a 10% drop in SPV

prices and 10% increase in diesel, the difference between the two would increase to Rs. 6.29 per kWh

from the current Rs. 4.83 per kWh.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 29

One can note from the above table that solar PV electricity is competitive with diesel+grid option, even

in today cost terms. For the diesel based system other than cost, the factors like availability, cost

uncertainty, maintenance, and storage of diesel also does not favor the use of diesel generator.

The above table gives an estimation of cost of electricity for solar, diesel and grid electricity. However,

the final cost of electricity depends on many parameters related to site where the electricity is

generated and used. Therefore there will always be some variation in the cost of electricity from one

location to other location. The Table below gives an indication of range of prices of electricity on per

kWh basis for various electricity sources. These prices are indicative prices of prevailing condition as in

year 2009‐10 and can change with the time. As noted earlier, the cost of diesel based electricity is

expected to rise further while the cost of PV based electricity is expected to decrease further with time.

Table: Typical values of cost of electricity for various sources

Source LCOE (Rs per kWh)

Grid electricity Rs. 3 to 5 (domestic)

Rs. 6 to 8 (commercial)

Rs. 8 to 15 (industrial)

Diesel based electricity 17 to 21

Solar PV electricity (grid connected) 10 to 15

Solar PV electricity (off‐grid) 12 to 17

Wind based electricity 4 to 6

8. Energy efficiency is recommended As can be seen from the calculations shown in the previous section that the cost of electricity generated

from PV modules is much more expensive as compared to grid electricity. Therefore all efforts should be

made to decrease the electricity requirement of a given building, before planning to use solar PV for

electricity generation. Reduced energy consumption without affecting the operations can greatly reduce

the amount of PV modules and battery required and, therefore, it can reduce the cost of PV system.

Decrease in electricity requirement, without decreasing the usage of loads or functionality, invariably

requires increase in energy efficiency. The increase in energy efficiency for an academic building and

appliances can be obtained in several ways. It includes the way building is constructed and used, the

way electrical loads are selected and the way the users of electricity treat it. These are listed here:

8.1 Energy efficiency of buildings

If PV electricity generation is planned before construction of building, then design the building using

what is known as “solar passive architecture”. In such design the heat intercepted by building wall and

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 30

roof is minimized, use of day light for illumination is increased, arrangements are made for proper

ventilation of spaces. Thus by incorporating the principles of solar passive architecture, one can reduce

the energy consumption for cooling, light and ventilation.

If building is already in place for which PV modules are to be installed, make efforts to decrease the heat

gain of the building. This can be done in several ways; make the outer surfaces (walls and roofs) white

(or light in color) so that some of the energy is reflected, make arrangements for sunshades particularly

for south facing walls. A roof can be covered with white shiny tiles (may be broken tiles available at low

cost) or in best case mirrors can be installed on the roof top to reflect most of incoming radiations.

8.2 Energy efficiency of electrical loads

Electrical loads as efficient as possible should be used. Investment in more efficient load pays back

within few months to few years time. Light source can be replaced with more efficient florescent lamps,

or LED based lighting. Also an electronic choke should be used with tube lights. More efficient fans are

available now a days. Star rating system is being used to mark the efficiency of air conditioner and

refrigerator. These systems with higher star rating should be used. Laptops consume much less power as

compared to desktops PCs (about 70 Watt as against 250 Watt), therefore as long as possible lap tops

should be promoted for computing.

Following are some of options that are available and can be used for electrical loads:

People detector based on IR signal

Timer based load switching

Light dimmers

Solid state lighting (LED)

Solid state fan regulators

8.3 Energy efficiency of users Users of electrical energy play very important role in determining the effectiveness of energy used.

Efforts should be made to make all users aware about the negative environmental effects of use of fossil

fuel based energy. In case of PV system usage, users should be made be aware to saving of electricity

whenever possible, they should be made aware of high cost of solar PV electricity. Well designed

posters, awareness generation workshops and e‐mail reminders can play important role in promoting

efficient use of electricity.

9. Subsidies for installing solar PV systems Various kinds of subsidies are provided by both central and state government for installation of solar PV

systems. These subsidies can be divided in following categories:

Subsidy for SPV rooftop systems for replacing diesel generators

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 31

Subsidy for off‐grid PV systems

Subsidy for rural electrification

Interest rate subsidy

Details of available subsidies are given in following sections. The details of subsidies can also be

obtained from Ministry of New and Renewable Energy Webpage, http://www.mnre.gov.in/

It must be noted that these subsidies are policy matters of the MNRE and may change time to time.

9.1 Subsidy for rooftop PV systems

Rooftop solar photovoltaic systems (with or without grid interaction) will be supported for installation in

industrial and commercial establishments/ complexes (excluding manufacturers of SPV cells/modules),

housing complexes, institutions and others which face electricity shortages and are using diesel

generators for backup power.

Central Financial Assistance (CFA) for SPV rooftop Systems (with or without grid interaction) will be

limited to 100 kWp capacity. Minimum capacity of installation will be 25 kWp. In special cases, smaller

capacity systems, not less than 10 kWp, could be considered for financial support from the Ministry.

Beneficiaries will exclude manufacturers of SPV cells/modules. Maximum system capacity for sanction of

CFA will be linked to the capacity of the existing diesel sets installed by the beneficiary entity. An entity

seeking CFA for a particular kWp SPV system must have a DG set of at least that capacity installed in its

premises.

The Central Financial Assistance is mentioned in Table below. The Government’s intent is to phase out

the CFA scheme and emphasis on the Interest rate subsidy scheme mentioned in Table below.

Table – Central Financial Assistance for decentralized Solar PV Applications

System Capacity Central Finance Assistance

Stand‐alone SPV Power Plants

>1 kWp Rs. 225/Wp Rs. 125/Wp

>10 kWp with distribution line Rs. 270/Wp Rs. 150/Wp

SPV Traffic Lights Rs.150/Wp for systems with battery bank of 6

hrs/Rs.115/Wp without battery bank for organizations

not availing accelerated depreciation.

Rs.100/Wp for systems with battery bank of 6 hrs /

SPV Blinkers

SPV Power Packs < 1kWp

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 32

Solar Billboards <= 1 kWp Rs.75/Wp without battery bank for organizations availing

accelerated depreciation. Other systems for Commercial and Urban

areas

SPV Rooftop Systems in Urban Areas –

from 10 kW to 100 kW

Rs. 75/ Wp, limited to 30% of the cost of systems to profit

making bodies availing depreciation benefits Rs. 100/ Wp,

limited to 40% of the cost of systems to non‐ profit

making bodies

9.2 Interest rate subsidies

There is also scheme for providing subsidy in the form of soft loan or low interest loans. Almost all

interested people can avail this type of subsidies. The details of interest rate subsidy program is given

below in Table.

Table– Interest Rate subsidies available through IREDA and Banks

Features Implementation through

IREDA (Indian Renewable Energy Development

Agency)

Banks

Eligible Categories All categories of users including intermediaries

and commercial organizations. Manufacturers

of PV systems are not available.

Individuals and organizations

which do not claim any

depreciation benefits on the

investment

Rate of Interest 7% (commercial borrowers, who can claim

depreciation benefits)

5% (individuals and other organizations which

undertake not to claim depreciation benefits).

Financial intermediaries who borrow funds

from IREDA for on‐lending at 5% or 7% rate of

interest, will be charged an interest rate of

2.5% or 4.5% respectively by IREDA. Such

intermediaries will not be able to claim

depreciation benefit and the on‐lending

arrangement will not be treated as a lease

arrangement.

5%

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 33

Loan Period 5 years 5 years

Moratorium 1 year No moratorium

Amount of Loan Upto 80% of the cost of the

Project

Upto 85% of the cost of the

systems

Upper limits for a

loan

No limit Rs. 5 lakhs

Service Charge 1% of the loan disbursed Rs.300 per loan disbursed

Systems covered All types of SPV systems are covered under this

scheme. Loans will not be provided at

subsidized rates for systems that are available

with capital subsidy, with the exception of solar

generators and solar pumps for which both

subsidies and soft loans will be available during

2005‐06.

All types of SPV systems are

covered under this scheme.

Loans will not be provided at

subsidized rates for systems that

are available with capital

subsidy, with the exception of

solar generators and solar

pumps for which both subsidies

and soft loans will be available

during 2005‐06. For solar home

systems installed as part of the

MNRE programme for

electrification of remote villages,

banks may provide soft loans for

the unsubsidized portion of the

cost of the systems.

Note those users can either available subsidy in capitol cost or interest rate subsidy (soft loan) but not

both.

10. Recommendations for use of Solar PV electricity The report has described how PV modules can be used to generate electricity for academic campuses in

India. The emphasis is given to academic campuses for the report can be used to design and implement

solar PV system for other applications as well.

The report has brought out the points, particularly from technology perspective to demonstrate how it

is possible to use solar PV power for electricity generation. It is feasible to install solar PV power for

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 34

fulfilling electricity needs of academic campuses in India. It is feasible both from technology as well as

economic perspective. Therefore it is recommended to install PV modules.

There are some other points, which are important considering the long term perspective on the growth

of the country, mentioned here which support the recommendations for installing PV modules for

electricity generation in academic campuses. These points are:

There are power shortages in many areas of the country where there is grid. But there are large

number of areas where grid has not yet reached. Supplying power to all requires use of

alternative sources.

India is blessed with good amount of sun shine. The sunshine is available bright enough is most

of the areas of the country for generation of electrical energy.

There are favorable government policies exist in the country for promotion of solar PV

technologies for power generation.

Use of PV power is useful in reducing the pollution.

Installation and use of PV modules would result in public awareness. Increased public awareness

can be useful in setting appropriate policies for long term sustainable development.

Installation of PV modules for power generation would results in creation of employment for

hundreds of thousands of people across the country over coming decade.

Use of solar PV power in the campus would sensitize young people about the climate change,

availability and use of alternative energy sources. These young students in future would become

researchers and policy makers of future. Skilled researchers and knowledgeable policy makers

are desirable for the country’s growth.

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 35

Appendix‐A

Monthly averaged daily global (G), monthly averaged daily diffused (D) and monthly averaged daily global radiation on the horizontal surface and on the surface tilted at latitude of the location (GL). G, D and GL are in kWh/m2‐day (kilo‐Watt‐hour/ m2‐day).

January to April

Jan Feb Mar Apr

G D GL G D GL G D GL G D GL

City

Ahmedabad 5 1.2 6.8 5.9 1.3 7.3 6.6 1.6 7.2 7.3 1.8 7.2

Bangalore 5.6 1.6 6.4 6.4 1.6 7.0 6.8 1.9 7.0 6.8 2.2 6.6

Bhubaneshwar 5.2 1.4 6.7 5.9 1.4 7.0 6.3 2 6.8 6.5 2.4 6.4

Bhopal 4.8 1 6.6 5.9 1 7.4 6.3 1.6 6.9 7 1.8 6.9

Chandigarh 3.6 1.6 5.4 4.7 2 6.2 5.6 2.4 6.4 6.6 2.6 6.6

Chennai 5.4 1.8 7.5 6.3 1.7 6.9 6.6 2 6.8 6.8 2.2 6.6

Delhi 4.3 1.3 6.3 5 1.4 6.6 6 2 6.8 6.8 2.4 6.8

Gwalior 4.5 1 6.5 5.5 1 7.1 6.2 1.6 7.0 7.5 1.8 7.4

Goa 5.6 1.4 6.7 6.3 1.4 7.1 6.6 1.8 6.9 6.8 2.4 6.6

Guwahati 3.8 1.6 5.2 4.8 2 6.0 5.4 2.4 5.9 5.8 2.8 5.7

Hyderabad 5.5 1.4 6.7 6.2 1.5 7.1 6.5 2 6.8 6.9 2.4 6.7

Indore 5.1 1.1 6.9 5.9 1.3 7.3 6.4 1.6 6.9 7.4 2 7.3

Jabalpur 4.9 1.1 6.6 5.7 1 7.1 6.2 1.6 6.8 6.9 1.8 6.8

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 36

Jamnagar 4.9 1 6.5 5.8 1.2 7.1 6.2 1.8 6.8 7 2.2 6.9

Jodhpur 4.6 1 6.7 5.6 1.1 7.3 6.6 1.7 7.4 7.3 1.8 7.2

Kolkatta 4.7 1.4 6.1 5.6 1 6.7 6.2 1.6 6.7 6.6 1.7 6.5

Lucknow 4.3 1.4 6.2 5.2 1.2 6.7 5.9 2 6.6 6.8 2.4 6.7

Mumbai 5.2 1.4 6.6 5.9 1.4 6.9 6.5 1.8 6.9 6.9 2.2 6.7

Nagpur 5 1.2 6.6 5.9 1.2 7.1 6.3 1.8 6.8 6.8 2.2 6.7

Patna 4.4 1.6 6.0 5.3 1.7 6.6 6.1 2.2 6.7 6.7 2.5 6.6

Pune 5.3 1.4 6.6 6 1.4 7.0 6.6 1.8 7.0 6.8 2.2 6.6

Ranchi 4.7 1.2 6.4 5.6 1.0 7.0 6.4 1.8 7.0 7 2.2 6.9

Solapur 5.6 1.4 6.9 6.3 1.4 7.3 6.6 2.0 7.0 6.8 2.4 6.6

Trivendrum 6 1.8 6.5 6.6 1.8 7.0 6.8 2.0 6.9 6.5 2.4 6.4

Visakhapatnam 5.3 1.5 6.5 6 1.6 6.9 6.5 2.0 6.9 6.5 2.5 6.3

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 37

Appendix‐A (continued)

Monthly averaged daily global (G), monthly averaged daily diffused (D) and monthly averaged daily global radiation on the horizontal surface and on the surface tilted at latitude of the location (GL). G, D and GL are in kWh/m2‐day (kilo‐Watt‐hour/ m2‐day).

May to August

May Jun Jul Aug

G D GL G D GL G D GL G D GL

City

Ahmedabad 7.6 2 6.9 6.6 3 5.9 5 3.4 4.6 4.6 3.3 4.4

Bangalore 6.4 2.6 6.0 6 3 5.6 4.6 2.9 4.4 4.8 3 4.7

Bhubaneshwar 6.4 2.6 5.8 5.3 3 4.8 4.6 3 4.3 4.8 3 4.6

Bhopal 7.2 2 6.5 6.2 2.9 5.5 4.7 3.2 4.4 4.4 3.1 4.2

Chandigarh 7.3 2.8 6.7 7 3.2 6.2 6.2 3.2 5.6 5.8 3 5.5

Chennai 6.3 2.4 5.9 5.5 2.8 5.1 5.2 2.9 4.9 5.6 2.8 5.4

Delhi 7.2 2.8 6.6 6 3.1 5.3 5.7 3 5.1 5.6 2.9 5.3

Gwalior 7.1 2 6.4 6.5 2.8 5.7 5.2 3 4.7 5 3 4.8

Goa 6.6 2.6 6.1 4.9 3 4.6 3.8 3.1 3.6 4.4 3 4.2

Guwahati 5.6 3 5.1 4.6 3.2 4.2 4.8 3.2 4.4 5 3 4.8

Hyderabad 6.9 2.5 6.4 5.8 3.2 5.3 4.9 3.3 4.6 5.2 3.2 5.0

Solar PV Electricity Solutions for Academic Campuses in India

© C.S. Solanki, Dept. of Energy Science and Engineering, IIT Bombay 38

Indore 7.4 2.1 6.7 6.4 3 5.8 4.9 3.4 4.6 4.4 3.2 4.2

Jabalpur 6.6 2.2 6.0 5.8 2.8 5.2 4.8 3 4.5 4.4 3 4.2

Jamnagar 7.4 2.1 6.7 6.2 3.1 5.6 5 3.4 4.7 4.8 3.2 4.6

Jodhpur 7.8 2.2 7.1 7.4 3 6.5 6.2 3 5.6 6 3 5.7

Kolkatta 6.4 2 5.9 5.2 2.8 4.7 4.8 3.1 4.4 4.8 3.1 4.6