SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING...SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING 4 1. SUMMARY This research...

Transcript of SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING...SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING 4 1. SUMMARY This research...

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

Report prepared for

The National Trust

by

Eleanor Ratcliffe

August 2015

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

2

CONTENTS Section Page List of terms and abbreviations .......................................................... 3

1. Summary ......................................................................................... 4

2. Introduction ..................................................................................... 2.1. The psychological benefits of nature .........................................

2.2. Benefits of blue nature ..............................................................

2.3. Benefits of the seaside ..............................................................

4

4

4

5

3. Aims ................................................................................................. 6

4. Method .............................................................................................

4.1. Research design and participants .............................................

4.2. Walking locations ......................................................................

4.3. Measures and dependent variables ..........................................

4.4. Procedure ..................................................................................

6

6

7

8

8

5. Results .............................................................................................

5.1. Data screening ..........................................................................

5.2. Change in self-reported sleep quality ........................................

5.3. Change in self-reported sleep quantity ......................................

5.4. Change in self-reported mood ...................................................

5.5. What do people associate with walking? ...................................

9

9

9

12

12

13

6. Discussion .......................................................................................

6.1. Summary of significant findings .................................................

6.2. Implications and potential explanations .....................................

6.3. Limitations of the data ...............................................................

17

17

18

19

7. Conclusions .................................................................................... 20

8. References ...................................................................................... 21

9. Acknowledgements ........................................................................ 23

10. About the author ............................................................................ 23

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

3

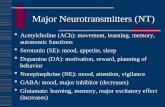

LIST OF TERMS AND ABBREVIATIONS A number of statistical terms and abbreviations are used in this report. For

clarity, they are defined here.

ANOVA Analysis of variance (tests for significant

differences between mean values)

Chi-squared test Tests likelihood that differences in frequencies

occurred by chance

Dependent variable Outcome measure (e.g. sleep quality, mood)

Independent variable Factor(s) being manipulated (e.g. walk location)

M Mean (average value)

Outlier An extreme score occurring at the very high or low

end of the distribution of scores

SD Standard deviation (spread of values from the

mean)

Significant In this report, a significance level of .05 has been

used. A statistically significant difference in values

has a less than 5% likelihood of occurring by

chance and, by extension, a 95% or higher

likelihood of occurring as a result of the

independent variable.

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

4

1. SUMMARY

This research explored effects of walking by the British coast on change in

mood and sleep. 54 participants undertook a coastal walk, and 55 an inland

walk. Both types of walkers experienced positive changes in happiness,

calmness, sleep quality, alertness, and sleep length following their walk.

However, coastal walkers showed a significantly greater increase in sleep

length than inland walkers, and were more likely to show increases in sleep

quality and alertness. Coastal walkers also reported place memory

associations relating to family, childhood, and holidays as well as

opportunities for introspection and reflective thought, which were less

apparent amongst inland walkers. Associations with holidays and escape to a

special destination could have offered coastal walkers greater scope to sleep

longer (and, to a certain extent, better).

2. INTRODUCTION

2.1. The psychological benefits of nature The psychological benefits of exposure to natural environments are well

known, from reductions in stress to improvements in mood, cognition, and

subjective wellbeing (cf. Berto, 2014, for a review). Such benefits are found

after exposure to media of nature, such as photographs (e.g. Berman,

Jonides, & Kaplan, 2008), videos (e.g. Ulrich et al., 1991), and sound

recordings (e.g. Alvarsson, Wiens, & Nilsson, 2010), but also direct

experience such as walking in nature (e.g. Hartig, Evans, Jamner, Davis, &

Gärling, 2003). Notably, individuals seem particularly fond of the multisensory

opportunities afforded by directly experiencing, rather than merely being

exposed to, nature – for example, hearing and smelling the natural world, and

interacting with flora and fauna (Kjellgren & Buhrkall, 2010).

2.2. Benefits of blue nature

Much of the research on the psychological benefits of nature has focused on

experience of green locations, but we now know that scenes containing water

– such as rivers, lakes, and seas – are particularly related to perceptions of

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

5

happiness, cognitive restoration, and stress recovery (White et al., 2010;

Völker & Kistemann, 2011; Wyles, Pahl, & Thompson, 2014). The sound of

water, along with other natural sounds, has also been implicated in stress

recovery (Alvarsson et al., 2010).

Ulrich (1983, p. 105) suggests that positive appraisals of water might stem

from its “biological” value as adaptive for human survival, as well as the ability

of water to add depth and a focal point to landscape. In setting out their theory

of attention restoration, Kaplan and Kaplan (1989) also comment on the ability

of certain dynamic aspects of nature, such as waterfalls, to attract attention

effortlessly and thereby facilitate cognitive recovery.

2.3. Benefits of the seaside

The presence of water is an important in positive experiences of nature, but

what of the sea specifically? For centuries, the coast – and particularly the

British coast – has been marketed as a way to “blow away the cobwebs”

(Beckerson & Walton, 2005, p. 56), and Depledge and Bird (2009) suggest

that there is an inherent desire for individuals to be the near the coast.

The body of evidence for therapeutic or beneficial effects of coastal visits has

grown in recent years. Living near the coast is related to increased health and

wellbeing (Wheeler, White, Stahl-Timmins, & Depledge, 2012; White, Alcock,

Wheeler, & Depledge, 2013), and psychological benefits of short-term

experiences such as a walk by the sea are related to happiness (Wyles et al.,

2014). Bell, Phoenix, Lovell, and Wheeler (in press) report perceptions of the

coast as calming and mentally restorative. These perceptions were related to

place attachment and memories of coastal places as well as the aesthetic

properties of the sea itself.

One understudied area of positive or restorative nature experiences is that of

sleep quality. Being by the sea is anecdotally related to health and sleep (e.g.

Mitchell, 2014, and Beckerson & Walton, 2005) but empirical evidence for this

claim is limited. However, the market prevalence of auditory sleep aids related

to seaside environments, such as CDs featuring ocean sounds, suggests links

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

6

between such environments and conditions suitable for sleep, such as

relaxation or reduced arousal. In addition, evidence showing greater energy

expenditure on coastal visits (Elliott, White, Taylor, & Herbert, 2015),

combined with known relationships between sleep length and energy

expenditure in the form of exercise (e.g. Kubitz, Landers, Petruzzello, & Han,

1996), suggests a hypothetical link between visiting the coast and improved

sleep quality and/or quantity.

3. AIMS

The research described in this report aimed to quantitatively examine whether

outdoor walking influenced self-reported sleep quality, quantity, and mood,

and specifically to examine whether there were differences in any such

changes between inland and coastal walkers.

In addition, the research included qualitative data collection and analysis

regarding associations with walking in inland and coastal locations, in order to

study potential differences in participant experiences in these locations.

4. METHOD

4.1. Research design and participants 109 participants (38 male, 69 female) were recruited for this study via social

media, contact with walking groups, and direct approach in the field. Ages

ranged from 21 to 82 years (M age = 58 years).

Participants undertook a questionnaire-based study in which measures of

mood and sleep quality were recorded before and after a coastal or inland

walk. The study utilised a mixed design, with location (coastal, inland) as the

between-participants independent variable and phase (pre-walk, post-

walk/morning-after) as the within-participants independent variable. 54

participants walked by the coast, and 55 inland. Participants were offered a

free day pass to a National Trust property in exchange for their participation.

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

7

No significant differences were observed between inland and coastal walkers

in terms of age, length of walk (time or distance), walks per month, or walk

difficulty, and no significant differences between men and women were found

on the dependent (outcome) variables. The average walk across conditions

was 7.24 miles long and lasted three hours and 40 minutes.

41 additional participants (13 male, 28 female, M age = 49 years) were

recruited online via social media in order to provide extra qualitative data.

These participants did not receive anything in exchange for their participation.

4.2. Walking locations Of the main sample of 109 participants, 54 walked by the coast. 25 of these

were recruited in the field at Bournemouth, Brighton, and Hove. A further 13

recruited online and 16 recruited via walking groups undertook walks at

coastal locations in Sussex, Devon, Kent, Dorset, the South West Coast Path,

and Wales. Of the 55 participants who walked inland, 22 were recruited in the

field in Winchester, Lewes, and Hampstead Heath. A further 12 recruited

online and 19 recruited via walking groups undertook walks at countryside,

nature reserve, and park locations in Kent, Sussex, Greater London, and

Yorkshire. Example photos of coastal and inland locations are provided in

Figures 1 and 2, below. Data were collected on weekends and weekdays

between June and August 2015, during a period of generally fair weather.

Figure 1. Example coastal location

(Brighton, Sussex)

Figure 2. Example inland location

(River Ouse, Lewes)

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

8

4.3. Measures and dependent variables Participants completed a three-page questionnaire comprising pre-walk (i.e.

baseline), post-walk, and morning-after phases. They were asked to indicate:

4.3.1. Sleep quality, captured pre-walk and the morning after the

walk. Sleep quality measures comprised:

• Overall sleep quality, measured from 1 (Very poor) to 5 (Very

good)

• Alertness on waking, from 1 (Very tired) to 5 (Very alert)

• Achieving and maintaining sleep; that is:

o Difficulty falling asleep, from 0 (No) to 1 (Yes)

o Time to sleep onset, in minutes

o Waking during the night, number of times

4.3.2. Sleep quantity, captured pre-walk and the morning after the

walk, in hours and minutes.

4.3.3. Mood, captured pre- and post-walk. Happiness and calmness

were measured on two rating scales from 1 (Very unhappy/Very

active) to 5 (Very happy/Very calm).

4.3.4. Qualitative associations and background information

Participants were also asked to indicate whether they had any particular

thoughts, feelings, memories, and associations during the walk, and if so to

write them in a free text box. Finally, participants completed a brief measure

of demographics and background information at the end of the questionnaire,

including gender, age, walk location and company, walk difficulty, and walking

frequency per month.

4.4. Procedure Participants recruited in the field were approached by the researcher and,

after providing verbal informed consent to take part, completed the pre-walk

phase of the questionnaire. They were then given the questionnaire, plus a

prepaid envelope and pen, and asked to complete the post-walk and morning-

after phases in their own time and to return the questionnaire in the post.

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

9

Participants recruited by the researcher online and via walking groups gave

verbal informed consent to participate prior to receiving a paper or online

version of the questionnaire. They completed the pre-walk, post-walk, and

morning-after phases in relation to a walk of their choosing. Paper

questionnaires were returned by participants using a prepaid envelope

addressed to a PO box, and online questionnaires were completed using

survey software.

No significant differences in dependent variables were found as a result of

method of recruitment (in the field versus online versus walking group), and

as such data from these sources were combined in the following analyses.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Data screening Four participants were missing data on at least one dependent variable, and

as such data from these participants were excluded from individual analyses

where relevant. These data were not missing in any systematic way and may

have been due to participants accidentally skipping over a question.

Subsequent screening showed three participants with outlier data points on

sleep quantity variables, so these participants were excluded from sleep

quantity analyses.

Analyses of variance (ANOVA) and, where appropriate, chi-squared tests

were used to examine whether any statistically significant differences in mean

values or frequencies on the dependent variables were due to the differences

in phase (pre-walk, post-walk) and/or location (inland, coastal).

5.2. Change in self-reported sleep quality

5.2.1. Sleep quality Across coastal and inland walkers combined, sleep quality significantly

improved the night after a walk (M = 3.83, SD = .98) in comparison to the

night before the walk (M = 3.49, SD = 1.04). This did not vary significantly

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

10

between coastal and inland route conditions, although there was a non-

significant trend towards a greater increase amongst coastal walkers.

Given this trend, an exploratory analysis of direction of change in sleep quality

was conducted. Coastal and inland walkers were categorised as showing a

sleep quality decrease, sleep quality increase, or no change.

Significantly fewer coastal walkers showed a decrease in sleep quality than

would be expected by chance; rather, most of these walkers either increased

or showed no change in sleep quality. In contrast, the numbers of inland

walkers who either increased, decreased, or showed no change in sleep

quality were more evenly spread. This is illustrated in Figure 3, below.

Figure 3. Number of participants who decreased, increased, or showed no

change in sleep quality after a coastal or inland walk.

5.2.2. Alertness on waking Across coastal and inland walkers combined, alertness on waking significantly

increased after a walk (M = 3.36, SD = .86) in comparison to before the walk

(M = 3.12, SD = .93). This change did not vary significantly between coastal

and inland walkers, but there was a non-significant trend towards a greater

increase in alertness amongst coastal walkers. As described in section 7.1.1,

0

5

10

15

20

25

Decrease No change Increase Decrease No change Increase

Coastal Inland

Num

ber o

f par

ticip

ants

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

11

exploratory analysis of the direction of change was conducted based on this

trend.

Significantly fewer coastal walkers showed decreases in alertness than would

be expected by chance; the majority of these walkers either showed an

increase or no change in alertness. By contrast, significantly more inland

walkers showed no change in alertness than would be expected by chance,

with fewer showing either decreases or increases as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Number of participants who decreased, increased, or showed no

change in alertness after a coastal or inland walk

5.2.3. Achieving and maintaining sleep Across coastal and inland walkers combined, the average time that it took

participants to get to sleep before a walk (M = 21 mins, SD = 24 mins) was

not significantly different to the time it took after a walk (M = 19 mins, SD = 18

mins). There were no significant differences in the frequency of sleep difficulty

occurrences before a walk (when 15% of the sample reported having difficulty

getting to sleep), or after (14%). These patterns of results did not vary

between coastal and inland walkers.

Across coastal and inland walkers, the average number of night-time wakings

was significantly lower after a walk (M = 1.20, SD = 1.16) than before (M =

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

Decrease No change Increase Decrease No change Increase

Coastal Inland

Num

ber o

f par

ticip

ants

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

12

1.58, SD = 1.53). However, this pattern of results also did not differ between

coastal and inland walkers.

5.3. Change in self-reported sleep quantity Across coastal and inland walkers combined, participants slept significantly

longer the night after a walk (M = 7 hours 25 mins, SD = 1 hour 1 min) than

they did the night before (M = 6 hours 55 mins, SD = 1 hour 17 mins); that is,

an average increase of 30 minutes.

This effect varied between inland and coastal walkers, as illustrated in Figure

5 below. Coastal walkers slept significantly longer post-walk than pre-walk,

while the increase for inland walkers was not significant. Coastal walkers slept

for 47 minutes longer after a walk, on average, versus only 12 minutes longer

for inland walkers.

Figure 5. Mean length of night-time sleep (± 1 standard deviation) pre- and

post-walk on coastal and inland routes.

5.4. Change in self-reported mood Walkers reported feeling significantly happier after a walk (M = 4.15, SD =

.57) than before (M = 3.78, SD = .70), and also significantly calmer after a

walk (M = 3.80, SD = 1.13) than before (M = 3.55, SD = 1.00). These effects

did not vary between coastal and inland walkers.

4

5

6

7

8

9

Pre-walk Post-walk Pre-walk Post-walk

Coastal Inland

Leng

th o

f sle

ep (h

ours

)

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

13

5.5. What do people associate with walking? Qualitative data regarding thoughts, feelings, associations and memories

relating to participant walks were analysed using thematic analysis (cf.

Ratcliffe, Gatersleben, & Sowden) in order to reveal five overarching themes

or categories. These were memories, mood, reflection, a sense of escape,

and attention. Data were analysed separately for coastal and inland walkers,

and are discussed and compared below. Analysis included data collected

online from the additional 41 participants described in section 4.1.

5.5.1. Memories in the past and for the future Past memory emerged as a particularly important theme amongst walkers.

Walking both inland and by the coast triggered memories of the past, as well

as awareness of forming memories that could be “recall[ed] at times of stress”

in the future as a form of self-soothing. Frequently the recall of memories was

positive or about happy life events, although some participants described

them as mixed in emotion or poignant:

The type of memory associated with the walk varied between coastal and

inland walkers. Walking by the sea triggered memories associated with

people close to the walker, such as parents, children, or other family

members, as well as the walker in their own childhood. These memories were

often reflective and described different times and stages of life. Walking inland

generated fewer memories of walking with family or loved ones; rather, these

memories more often related to previous experiences of the walking location

or of general, non-specific memories.

“The walk is in an area where I have holidayed many times over more than

25 years so is very rich with happy associations. In particular one spot has

very strong memories of taking a photograph of my son when he was about

11 year[s] old. He's now 21 and away at University so the memories are

quite poignant; happy but tinged with a little sadness about the passing of

time.” Male aged 54, walking by the coast.

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

14

5.5.2. Happy and calm mood Echoing quantitative findings described in section 5.2, both walking by the

coast and inland were related to qualitative perceptions of happiness and

calmness or relaxation. Emotional reactions to inland walks were almost

universally positive, while as noted in section 4.3.1, emotional responses to

the coast were sometimes bittersweet or nostalgic. Another participant

described “always looking forward to that first ‘glimpse’ of the sea”, suggesting

a tantalising or anticipatory quality about walking towards the coast. This

aligns with notions of the coast being a special destination, as discussed in

section 7.3.4.

5.5.3. Reflection Coastal and inland walkers both used their walk as an opportunity to think and

reflect. For some participants this reflection was on everyday matters such as

“daily life, recent pressures” and for others it was more profound, such as

“Thinking about [a] recent bereavement” (coastal walker) or planning for the

future: “What to do next with my life, what job? When will I move away?”

(inland walker).

Coastal and inland walkers displayed both everyday and deeper types of

reflection. However, some inland walkers also reported experiencing “too

much visual stimulation to allow mind to wander which is perfect”, suggesting

that reflection may not always be desirable (which relates to the notion of

escape discussed in section 4.3.4). Coastal walkers appeared more uniformly

“Just memories of being by the sea as a kid, and playing for hours in the

sand and the water, not needing any other entertaining.”

Female aged 53, walking by the coast

“I have a busy week coming up, I thought through each day as I was walking

which made me feel calmer and more organised.”

Female aged 43, walking by the coast

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

15

receptive to reflective thought processes as well as attending to their

surroundings, although one coastal walker did note that “the scenery was so

beautiful, I kept in the moment.”

5.5.4. Escape Despite using the walk as an opportunity to reflect on important matters,

walking was also associated with feelings of freedom and escape for many

participants. This may offer psychological refreshment due to a sense of

‘being away’ from everyday life (cf. Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989; Kaplan, 1995).

For coastal walkers, this was encapsulated in comments from walkers who

explicitly said that they were on holiday and/or had been on holiday there in

the past, including important events such as a honeymoon, and were

therefore likely to be taking a break from daily life.

The exoticism and remoteness of coastal locations was also related to

perceptions of being away:

Inland walkers did not refer to their walks as part of a holiday but rather

commented on the sense of freedom achieved through being in the

countryside, particularly through physical exertion. The comments suggest

that the coast still retains the associations and romance of a holiday

destination, while inland walking can be seen as an accessible way to escape

from daily stresses.

“Memories of our honeymoon, 29 years ago, when we stayed just along

the coast.” Female aged 56, walking by the coast

“It is like being in a jungle and feels very isolated. You can't hear any

cars or manmade noise, you rarely meet people, you get glimpses of the

sea but it feels like you could be in any place or time.”

Female aged 44, walking by the coast

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

16

5.5.5. Attention Both coastal and inland walkers commented on their attention to the

surroundings on their walks. They attended to the overall landscape or

seascape, as well as smaller details like animals, birds, flowers, and plants.

Views were often mentioned and described as beautiful by both coastal and

inland walkers. One coastal walker commented on other sensory experiences

such as sounds and smells:

Descriptions of attention to surroundings by inland walkers tended to be more

detailed and focused than coastal walkers; for example, many inland walkers

were engaged in wildlife spotting (e.g. “Joy and excitement at seeing some

rare flowers (burnt-tip orchid) and butterflies (marsh fritillary and adonis blue),

happiness while watching a fox”). While coastal walkers also engaged in

some of these activities, their attention appeared broader in terms of

appreciating the landscape as a whole.

This difference in specificity of attention may also be related to reflection; as

noted in section 4.3.3, inland walkers were less likely to want to focus on

internal thoughts, and indeed commented on social aspects of the walk such

as company and conversation far more than coastal walkers. Coastal walkers

may have engaged more in internal reflection, particularly in environments

where there was “not a lot else” besides the view of the sea, although some

coastal walkers did report “enjoying watching the world go by and feeling in

the moment”.

“There are wonderful smells of wild garlic and lots of birds singing and

not a lot else.” Female aged 44, walking by the coast

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

17

6. DISCUSSION

6.1. Summary of significant findings This study investigated the effects of outdoor walking on mood, sleep quality,

and sleep quantity, and in particular explored whether differences in these

effects might occur between coastal and inland walkers.

Mood (happiness and calmness) and self-reported sleep quality (as measured

through sleep quality, morning alertness, and night-time wakings) significantly

improved after a walk, but this occurred regardless of whether the walk took

place coastally or inland. However, on inspection of how many participants

reported improvements in sleep quality and morning alertness, coastal

walkers showed a significant advantage. They were more likely to either

improve or maintain their sleep quality and alertness than they were to report

a decrease, whereas the direction of change in inland walkers was more

evenly split (in the case of sleep quality) or tended towards maintenance (in

the case of alertness). Self-reported sleep length improved significantly after a

walk, and this difference was also significantly greater for coastal walkers than

it was for inland walkers. In plain terms, coastal walkers, but not inland

walkers, were more likely to show an improvement in sleep quality and

alertness, and they showed a much larger increase in how long they slept

following a walk.

Examination of qualitative data provided by participants indicated that

memories of coastal walks were more closely associated with family and

childhood self than inland walks, supporting findings from Bell et al. (in press).

The coast was also seen as a greater opportunity for introspection and

reflective thought, linking to concepts of a psychologically restorative or

beneficial environment (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989). Coastal walks were

associated with holidays, previous trips away, and heightened emotions in the

form of nostalgia and anticipation, while inland walks were more closely

associated with attention to flora and fauna.

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

18

Together, these findings provide evidence for promoting walks along British

coasts. Like inland walks, they can promote positive changes in mood and

sleep, but seaside walks are more strongly related to longer (and, to a lesser

extent, better) sleep. Place memory and place attachment are particularly

related to coastal walks, with emphasis on family and children, which speaks

strongly to the history of British coastlines as a place for family holidays.

6.2. Implications and potential explanations The findings above indicate a small, yet statistically significant, difference

between coastal and inland walkers in terms of how they experience sleep

after a walk, and a clear difference in terms of how long they sleep. Walking

by the coast is related to sleeping longer, and increases the chances of

sleeping better, relative to inland walking. This may be related to feelings of

escape, discussed below, but existing research regarding energy expenditure

is also relevant.

6.2.1. A sense of escape The qualitative findings relating to coastal and inland walks reflect the

quantitative findings that both groups experienced the walks as relaxing and

pleasant. However, coastal walkers were more likely to associate the walk

and/or the walking location with a holiday experience. Given relationships

between restorative environments and a sense of escape or ‘being away’ from

daily life (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989), it may be that coastal walkers felt more

able to relax and let go in these environments due to their associations with

holidays, with potential effects on sleep length. Notably, quantitative

measures of change in mood did not show significant differences between

coastal and inland environments, but qualitative data showed a greater

tendency for coastal walkers to reflect, closely related to psychological

restoration and, ultimately, relaxation (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989).

6.2.2. Energy expenditure Previous research has associated coastal visits with greater energy

expenditure than visits to other types of natural environments, which may be

due to their longer duration (Elliott et al., 2015). However, as noted in section

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

19

3.1, the coastal and inland groups in this study did not differ significantly in

terms of length of walk or how hard participants found them. This may

account for the finding of only small differences in self-reported sleep quality

and alertness between coastal and inland walkers.

It is also notable that coastal visitors beyond the present research engage in

other activities besides walking such as swimming, beach sports, and play

(Elliott et al., 2015; Bell et al., in press) which may impact on how tired they

feel and how well they sleep. This study concentrated only on coastal walkers,

but future studies might wish to study what it is that people do at the beach

besides walking and how this relates to sleep.

6.3. Limitations of the data

6.3.1. Quasi-experimental design The data in this study were collected in a quasi-experimental manner by

contact with participants who were already planning a walk in a coastal or

inland location. As such, participants may have chosen to walk in locations

that best suited their needs at that particular time; indeed, as shown through

the qualitative data, several coastal walkers had personal connections with

their walking locations. Random assignment of participants to walk in either a

coastal or an inland location would serve to counteract this issue, and might

reveal differences in walking experiences otherwise obscured by personal

choice over walking location.

6.3.2. Recall of sleep quality The study also asked participants to recall their previous night’s sleep at the

start of the walk; that is, after some time had elapsed since waking. As such,

participants may not have been able to answer questions about sleep quantity

or quality as accurately as they did the following morning. Issuing participants

with a longer-term sleep diary would enable the collection of data immediately

upon waking on the day of the walk, as well as the day after.

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

20

6.3.3. Need for restoration or recovery It is notable that, on average, participants in this study did not report

especially low mood or sleep quality prior to taking a walk. In this sense the

scope for differences in improvement in either mood or sleep between coastal

and inland locations may have been limited, by virtue of the fact that

participants generally felt positive and well-rested prior to the walk anyway.

Checks were conducted to see whether differences in improvement between

coastal and inland locations were apparent amongst participants who

displayed low mood or sleep quality prior to the walk, and no significant

differences were found, but sample sizes in this instance were relatively low

(approximately 25 participants) and as such may have limited the opportunity

to find significant differences1. Future research might wish to concentrate

specifically on the restorative effects of coastal versus inland walking amongst

participants who are stressed, in a negative mood, and/or displaying sleep

difficulties.

7. CONCLUSIONS

This study collected data from 109 participants walking in either a coastal or

an inland region of the United Kingdom. Coastal walkers were significantly

more likely to show an improvement, no matter how big or small, in sleep

quality or alertness. In addition, coastal walkers showed a significantly larger

improvement in sleep duration than inland walkers, increasing their night’s

sleep by an average of 47 minutes. Qualitative data indicate that the coast is

a place that prompts memories of family and childhood, as well as being

perceived as a holiday destination regarded with heightened emotion and

anticipation. This attachment to place may generate feelings of being away

that could lead to restorative or psychological beneficial experiences,

including longer sleep.

1 For brevity the results of these post-hoc analyses have not been reported here, but are available from the author on request.

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

21

8. REFERENCES

Alvarsson, J. J., Wiens, S., & Nilsson, M. E. (2010). Stress recovery during

exposure to nature sound and environmental noise. International Journal

of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7, 1036-1046.

Beckerson, J., & Walton, J. K. (2005). Selling air: Marketing the intangible at

British resorts. In J. K. Walton (Ed.), Histories of tourism: Representation,

identity and conflict. (p. 55-68). Clevedon: Channel View Publications.

Bell, S. L., Phoenix, C., Lovell, R., & Wheeler, B. W. (in press). Seeking

everyday wellbeing: the coast as a therapeutic landscape. Social Science

& Medicine.

Berman, M. G., Jonides, J., & Kaplan, S. (2008). The cognitive benefits of

interacting with nature. Psychological Science, 19, 1207-1212.

Berto, R. (2014). The role of nature in coping with psycho-physiological

stress: A literature review on restorativeness. Behavioral Sciences, 4,

394-409.

Depledge, M. H., & Bird, W. J. (2009). The Blue Gym: Health and wellbeing

from our coasts. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 58, 947-948.

Elliott, L. R., White, M. P., Taylor, A. H., & Herbert, S. (2015). Energy

expenditure on recreational visits to different natural environments. Social

Science & Medicine, 139, 53-60.

Hartig, T., Evans, G. W., Jamner, L. D., Davis, D. S., & Gärling, T. (2003).

Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. Journal of

Environmental Psychology, 23, 109-123.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological

perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kjellgren, A., & Buhrkall, H. (2010). A comparison of the restorative effect of a

natural environment with that of a simulated natural environment. Journal

of Environmental Psychology, 30, 464-472.

Kubitz, K. A., Landers, D. M., Petruzzello, S. J., & Han, M. (1996). The effects

of acute and chronic exercise on sleep. Sports Medicine, 21, 277-291.

Mitchell, H. (2014, August 11). Does the sea air have curative powers? Wall

Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/does-the-sea-

air-have-curative-powers-1407797285.

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

22

Ratcliffe, E., Gatersleben, B., & Sowden, P. T. (2013). Bird sounds and their

contributions to perceived attention restoration and stress recovery.

Journal of Environmental Psychology, 38, 221-228.

Ulrich, R. S. (1983). Aesthetic and affective response to natural environment.

In I. Altman & J. F. Wohlwill (Eds.), Human Behavior and Environment.

New York: Plenum Press, Vol. 6, Behavior and the Natural Environment,

85-125.

Ulrich, R. S., Simons, R. F., Losito, B. D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M. A., & Zelson, M.

(1991). Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban

environments. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 11, 201-230.

Völker, S., & Kistemann, T. (2011). The impact of blue space on human

health and well-being – Salutogenetic health effects of inland surface

waters: A review. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental

Health, 214, 449-460.

Wheeler, B. W., White, M., Stahl-Timmins, W., & Depledge, M. H. (2012).

Does living by the coast improve health and wellbeing? Health & Place,

18, 1198-1201.

White, M., Smith, A., Humphryes, K., Pahl, S., Snelling, D., & Depledge, M.

(2010). Blue space: the importance of water for preference, affect, and

restorativeness ratings of natural and built scenes. Journal of

Environmental Psychology, 30, 482-493.

White, M. P., Alcock, I., Wheeler, B. W., & Depledge, M. H. (2013). Coastal

proximity, health and well-being: Results from a longitudinal panel survey.

Health & Place, 23, 97-103.

Wyles, K. J., Pahl, S., & Thompson, R. C. (2014). Perceived risks and

benefits of recreational visits to the marine environment: Integrating

impacts on the environment and impacts on the visitor. Ocean and

Coastal Management, 88, 53-63.

SLEEP, MOOD, AND COASTAL WALKING

23

9. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to thank the participants who took part in this research

and the individuals who helped to advertise it online and by word of mouth –

in particular, Roger Bennett, Sue Ellenby, Christine de Groot, and David

Powell.

10. ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Eleanor Ratcliffe is an environmental psychologist, specialising in the

effects of natural and built environments on mood and attention. In 2015 she

completed her PhD at the University of Surrey on the psychological benefits of

listening to birdsong, and is conducting postdoctoral research on memories of

favourite places at the University of Tampere, Finland.

Eleanor conducted the research described in this report in an independent

capacity on behalf of the client, the National Trust. For further information,

please contact her at [email protected] or [email protected].