Scientific Light ISSN 0548-7110 · Equisetophyta 1 2,85 1 2,38 1 0,89 1 0,65 Equisetopsida 1 2,85 1...

Transcript of Scientific Light ISSN 0548-7110 · Equisetophyta 1 2,85 1 2,38 1 0,89 1 0,65 Equisetopsida 1 2,85 1...

VOL 1, No 22 (2018)

Scientific Light (Wroclaw, Poland)

ISSN 0548-7110

The journal is registered and published in Poland.

The journal publishes scientific studies,

reports and reports about achievements in different scientific fields.

Journal is published in English, Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, German and French.

Frequency: 12 issues per year.

Format - A4

All articles are reviewed

Free access to the electronic version of journal.

Edition of journal does not carry responsibility for the materials published in a journal.

Sending the article to the editorial the author confirms it’s uniqueness and takes full responsibility for

possible consequences for breaking copyright laws

Chief editor: Zbigniew Urbański

Managing editor: Feliks Mróz

Julian Wilczyński — Uniwersytet Warszawski

Krzysztof Leśniak — Politechnika Warszawska

Antoni Kujawa — Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie

Stanisław Walczak — Politechnika Krakowska im. Tadeusza Kościuszki

Eugeniusz Kwiatkowski — Uniwersytet Pedagogiczny im. Komisji Edukacji Narodowej w Krakowie

Marcin Sawicki — Uniwersytet Wrocławski

Janusz Olszewski — Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu

Karol Marek — Uniwersytet Medyczny im. Karola Marcinkowskiego w Poznaniu

Witold Stankiewicz — Uniwersytet Opolski

Jan Paluch — Uniwersytet Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej w Lublinie

Jerzy Cieślik — Uniwersytet Gdański

Artur Zalewski — Uniwersytet Śląski w Katowicach

Andrzej Skrzypczak — Uniwersytet Łódzki

«Scientific Light»

Editorial board address: Ul. Sw, Elżbiety 4, 50-111 Wroclaw

E-mail: [email protected]

Web: www.slg-journal.com

CONTENT

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES

Nasirova A. THE TAXONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS AND USAGE

DIVERSITY OF WILD VEGETABLE PLANTS SPREAD

IN BATABAT MASSIVE OF NAKHCHIVAN

AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC .......................................... 3

PEDAGOGICAL SCIENCES

Kurchatova A. USE OF MULTIMEDIA IN FORMATION OF INTEREST IN LEARNING OF PRESCHOOL AGE CHILDREN ... 10

PHILOLOGY

Kuznetsova L. THE PREDICATES REPRESENTING CONCEPT

"LOVE" IN THE RUSSIAN AND ENGLISH

LANGUAGES (lexico-semantic aspect) ......................... 14

Shamansurov Sh. THE SEMANTIC ANALYSIS OF QUANTIFIERS IN UZBEK LANGUAGE .....................................................18

PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCES

Akinshina S. FACTORS AFFECTING THE FORMATION OF

PROFESSIONAL COMPETENCE OF STUDENTS – PSYCHOLOGISTS ......................................................... 21

TECHNICAL SCIENCES

Коvalev А.V. INFLUENCE INTENSITY ADMISSION WARMTH ON

THERMOPHYSICAL DESCRIPTIONS TEST AND BREAD ........................................................................... 23

Scientific Light No 22, 2018 3

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES

THE TAXONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS AND USAGE DIVERSITY OF WILD VEGETABLE PLANTS SPREAD IN BATABAT MASSIVE OF NAKHCHIVAN AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC

Nasirova A.

Doctor of Philosophy in Biology, Senior scientific worker in Bioresources Institute

of Nakhchivan branch of Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences

Abstract:

This article deals with the systematic composition, taxonomic characteristics and usage diversity of wild

vegetable plants disseminated in the Batabat massive of the Shahbuz region of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.

A systematic review of the wild vegetable plants of the Batabat massive was identified for the first time by the fact

that they consisted of 3 class, 12 subclass, 25 superodo, 35 ordo, 42 family, 112 genera and 154 species. By

comparative analyzing of the distribution of genus and species of wild vegetable plants spread in the area according

to the families was carried out: Asteraceae Bercht et Presl family by 22 genera, 29 species ; Apiaceae Lindl. by 15

genera, 23 species ; Brassicaceae Burnett by 11 genera, 12 species ; Lamiaceae Martinov by 7 genera, 9 species ;

Polygonaceae Juss. by 6 genera, 14 species ; Fabaceae Lindl. by 5 genera, 6 species have been dominated. While

characterizing the main genera of wild vegetable plants in the flora spread in Batabat massive it has been found

that Allium L. is predominantly represented by 8 species, Rumex L. – 7 species, Heracleum L. – 4 species,

Scorzonera L. – 4 species, Tragopogon L. – 3 species. The life forms of wild vegetable plants have been analyzed

according to the Serebryakov system and predominance of 113 species of perennial herbs, 21 species of annual

herbs and 13 species of biennial herbs was discovered. Analyzing the different usage categories of wild vegetable

plants in the area in 6 groups it have been revealed that, most of species are cooked as vegetable and are eaten in

raw [51 species; 33.64%]. The classification of wild vegetable plants according to their usage parts was given,

thus, 45 species were those only their young shoots and leaves are used and 30 species were only leaves are used.

Key words: Nakhchivan, Shahbuz, Batabat, wild vegetable plants, systematic analysis, family, genus,

species, life forms, usage categories, used parts

Introduction

Rich biodiversity is crucial in ensuring a number

of essential and important human needs. Since ancient

times, people have accumulated various plant resources

to meet a number of daily needs. In the majority of

developing countries, millions of people get their

livelihoods and their income at the expense of wild

vegetable crops. Wild vegetable plants also provide

essential nutrients for local people as well as additional

food and alternative sources of income. Wild

vegetables are important nutrients and vitamin

supplements for indigenous people. That's why wild

food resources are a source in the period of food

shortages, reducing the sensitivity of food security of

the local population. Furthermore, wild vegetable

plants have significant potential for the development of

new products through own farms and provide genetic

resources for hybridization and selection [14; 17; 18;

19; 20; 21].

The importance of wild vegetable species is still

not considered in economic development, in the

conservation of biodiversity, in the planning and

implementation of land usage [21]. Taking these into

consideration, this research was carried out in the

Batabat massive, one of the most rich floristic zones of

the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic, to collect

information on the diversity of wild vegetable plants,

their traditional knowledge, economic potential and

conservation value.

Research area

The initial inquiries for this study were conducted

in the villages of Shahbuz district of Nakhchivan

Autonomous Republic, in particular in Bichanek

village. Shahbuz State Nature Reserve was created by

the 1249 numbered, 16 June, 2003 dated Order of the

President of Azerbaijan Republic for purpose of the

collection, study, protection, rational and sustainable

use of biological diversity of genetic fund, conservation

and delivering of future generations and environmental

monitoring in the administrative territory of the

Shahbuz district of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.

The reserve is located in the middle and highland part

of the Shahbuz region - alongside the source of

Nakhchivanchay. Reserve is divided into two areas:

Gotursu and Batabat. Batabat area is 2714,21 hectares

and covers Amalig-Batabat zone. The study of

literature and collected herbariums revealed that the

flora of Shahbuz State Reserve consists of 1575 species

of 504 genera belonging to the 116 families. This is

21,00 % of the Caucasian flora, 35,00 % of the flora of

Azerbaijan and 55,56 % of the flora of the Nakhchivan

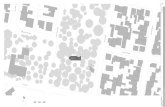

Autonomous Republic [5], [Figure 1].

4 Scientific Light No 22, 2018

Fig. 1. Map scheme of the Shahbuz State Nature Reserve [5].

The investigation of the area, materials and

methods

The research objects were wild vegetable plants

coolected from the territory of Batabat massive of

Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic and since April,

2018 the territory expeditions were carried out at

various stages. The researches were carried out

according to the plan and 11 expeditions were

organized in the first 6 months.

The description of species, in the clarification of

their names and nomenclature changes were carried out

by the using of works of “Флора Азербайджана” [14],

“Флора Кавказа” [7], “Определитель растений

Кавказа” [8], “Флора СССР” [15], Б.С. Новинков

[12], “Международный кодекс ботанической

номенклатуры” [11], С.К. Черепанов “Сосудистые

Растения России и Сопредельных Государств (в

пределах бывшего СССР)” [16], A.M. Asgarov's

“The conspectus of the flora of Azerbaijan” from 3

volumes [1; 2; 3], “Конспект флоры Кавказа” [9; 10],

“Taxonomic spectrum of the flora of Nakhchivan AR”

[6], “The flora and vegetation of Shahbuz State Nature

Reserve” [5], “Wild vegetable plants of the Nakhchivan

Autonomous Republic” [4] and internet resources of

www.theplant.list [22], www.catalogueoflife.org [23],

eol.org [24]. Серебрйаков [13] system was used in the

determining the life forms of species.

The results and discussion

The flora of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

has rich plant resources. The wild vegetable crops take

a special place in this richness. For the first time on the

basis of our research and investigated literature, a

systematic review of the wild vegetable plants spread

in the Batabat massive of Nakhchivan Autonomous

Republic has been compiled. According to the literature

materials [4; 5] and the plant samples collected during

our field research, for the first time systematic analysis

of wild vegetable plants spread in the Batabat massive

of the flora of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic was

carried out and analyzes were reflected in the tables.

The wild vegetable plants spread in the Batabat massive

are combined in three classes: Magnoliopsida,

Liliopsida, Equisetophyta. Magnoliopsida have spread:

8 subclass (66,67 %), 18 superordo (72 %), 21 ordo (60

%), 26 family (61,9 %), 93 genera (83,04 %) and 128

species (83,1 %); Liliopsida were divided into: 4

subclass (33,3 %), 7 superordo (28 %), 13 ordo (37,1

%), 15 family (35, 71 %), 18 genera (16,1 %) and 25

species (16, 2 %); Equisetophyta was spread in 1 ordo

(2,85 %), 1 family (2,38 %), 1 genus (0,89 %) and one

species (0,65 %) [Table 1; Table 2; Table 3].

Scientific Light No 22, 2018 5

Table 1. The systematic structure of wild vegetable plants spread in Batabat massive of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

Phylum and class

Subclass Superordo Ordo Family Genus Species

Nu

mb

er

By

%

Nu

mb

er

By

%

Nu

mb

er

By

%

Nu

mb

er

By

%

Nu

mb

er

By

%

Nu

mb

er

By

%

Magnoliophyta 12 100 25 100 34 97,1 41 97,61 111 99,12 153 99,35

Magnoliopsida 8 66,67 18 72 21 60 26 61,9 93 83,04 128 83,1

Liliopsida 4 33,3 7 28 13 37,1 15 35,71 18 16,1 25 16,2

Equisetophyta 1 2,85 1 2,38 1 0,89 1 0,65

Equisetopsida 1 2,85 1 2,38 1 0,89 1 0,65

Sum 12 100 25 100 35 100 42 100 112 100 154 100

Table 2. Spreading of species and genera of wild vegetable plants spread in the

Batabat massive of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic according to the family

№ Family Genera Species

Number By % Number By %

Dicotyledonae

1. Amaranthaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

2. Apiaceae Lindl. 15 13,39 23 14,94

3. Asteraceae Bercht et Presl 22 19,64 29 18,83

4. Brassicaceae Burnett 11 9,82 12 7,79

5. Caryphyllaceae Juss. 2 1,79 2 1,3

6. Chenopodiaceae Vent 1 0,89 2 1,3

7. Convolvulaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

8. Geraniaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

9. Fabaceae Lindl. 5 4,46 6 3,9

10. Lamiaceae Martinov 7 6,25 9 5,84

11. Malvaceae Small 1 0,89 2 1,3

12. Plantaginaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

13. Polygonaceae Juss. 6 5,36 14 9,09

14. Portulacaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

15. Ranunculaceae Juss. 2 1,79 3 1,95

16. Rosaceae Juss. 3 2,68 5 3,25

17. Scrophulariaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

18. Urticaceae Juss. 1 0,89 2 1,3

19. Onaqraceae Juss. 1 0,89 2 1,3

20. Campanulaceae Juss. 2 1,79 3 1,95

21. Boraginaceae Adans. 2 1,79 2 1,3

22. Primulaceae Vent. 1 0,89 1 0,65

23. Cannabaceae Martinov 1 0,89 1 0,65

24. Solanacaea Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

25. Crassulacea DC. 2 1,79 2 1,3

26. Dipsacaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

Monocotyledonae

27. Alliaceae J. Agardh 1 0,89 8 5,19

28. Araceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

29. Asparagaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

30. Asphodelaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

31. Hyacinthaceae Batsch ex Borkh 3 2,68 3 1,95

32. Iridaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

33. Colchicaceae DC. 2 0,89 2 1,3

34. Convallariaceae Horan 1 0,89 1 0,65

35. Alismataceae Vent. 1 0,89 1 0,65

36. Butomaceae Mirb. 1 0,89 1 0,65

37. Poaceae Barnhart 1 0,89 1 0,65

38. Typhaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

39. Orchidaceae Juss. 1 0,89 1 0,65

40. Juncaginaceae Rich. 1 0,89 1 0,65

41. Lemnaceae S.F. Gray 1 0,89 1 0,65

Equisetineae

42. Eguisetaceae Mich. ex DC. 1 0,89 1 0,65

Sum: 112 100 154 100

6 Scientific Light No 22, 2018

As is known from the table by comparative

analyzing of the distribution of genus and species of

wild vegetable plants according to families spread in

the area was carried out: Asteraceae Bercht et Presl

family by 22 genera, 29 species ; Apiaceae Lindl. by 15

genera, 23 species ; Brassicaceae Burnett by 11 genera,

12 species ; Lamiaceae Martinov by 7 genera, 9

species ; Polygonaceae Juss. by 6 genera, 14 species ;

Fabaceae Lindl. by 5 genera, 6 species were

dominated. The other 36 families were found to be 1, 2,

3, 5, 8 species, respectively, with 1, 2 or 3 genera.

Table 3.

The main genera of wild vegetable plants in the

flora of Batabat massive of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

№ Genera Species

Number By % to the total number

1. Allium L. 8 5,19

2. Rumex L. 7 4,55

3. Heracleum L . 4 2,6

4. Scorzonera L. 4 2,6

5. Tragopogon L. 3 1,95

6. The remaining 109 genera are represented by 1-2 species. 128 83,12

Sum: 154 100

As you can see from the table above,

characterizing the main genera of wild vegetable plants

in the flora spread in Batabat massive it has been found

that Allium L. is predominantly represented by 8

species, Rumex L. – 7 species, Heracleum L. – 4

species, Scorzonera L. – 4 species, Tragopogon L. – 3

species.

Since, the Rumex euxinus Klok species of Rumex

L. genus of Polygonaceae Juss. family as shown by

previous authors, is a synonym for the Rumex tuberosus

L. species, we have recorded R. tuberosus L. in the

taxonomic composition. Polygonum alpestre C.A.

Mey. species of Polygonum L. genus was found to be

synonymous with Polygonum cognatum Meis species.

Since the Bistorta Hill genus is associated with the

Persicaria Hill genus, the mentioned Bistorta carnea

(C. Koch) Kom species is crossed Persicaria bistorta

(L.) Samp taxonomic rank. Amoria repens (L.C.) Presl

species of Amoria L. genus of Fabaceae Lindl family

is crossed Trifolium repens L. taxonomic rank.

Chamaenerion Hill. genus has been classified as the

genus of Epilobium L., and the Chamaenerion

angustifolium (L.) Scop. species of this genus has been

confirmed as Epilobium angustifolium L. The Cachrys

microcarpa Bieb. species of Cachrys L. genus

belonging to the Apiaceae Lindl. family is included

Bilacunaria M. Piman. & V. Tichomirov

Hippomarathrum Hoffm. & Link as the Bilacunaria

microcarpa (Bieb.) M. Pimen & V. Tichomirov name.

It was discovered that, Carduus thoermeri Weinm

species of Carduus L. genus of Asteraceae Bercht et

Presl family is the synonym of Carduus nutans subsp.

leiophyllus (Petrovic) Stoj & Stef.. The Cirsium elodes

Bieb. species of the Cirsium Hill. genus were

determined to be synonymous with the species of

Cirsium alatum (S.G. Gmel.) Bobrov. The Primula

macroalyx Bunge species of Primulaceae Vent. is a

synonym for the Primula veris subsp. macrocalyx

(Bunge) Ludi subspecies. Merendera trigyna (Stev. ex

Adams) Starf species of Colchicaceae DC. family is a

synonym for Merendera trigyna Woronow species.

Merendera raddeana Regel species of the family was

classified as the synonym Colchium raddeanum

(Regel) K. Press species [22; 23; 24].

Analysis of the basic life forms of wild vegetable

plants spread in the Batabat massive of the Nakhchivan

Autonomous Republic was carried out on the basis of

I.G. Serebryakov's classification system. From the

analysis of the life forms of wild vegetable plants

spread across the area, it seems that these plants are

mostly herbaceous plants. Table 4 shows the basic life

forms of wild vegetable plants spread in the Batabat

massive of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.

Table 4.

Classification of wild vegetable plants spread in the Batabat massive

of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic according to their life forms

№ Life forms Number of species By % to the total number

According to the Serebryakov system

1. Annual herb 21 13,64

2. Biennial herb 13 8,44

3. Perennial herb 113 73,38

4. Annual or biennial herb 6 3,90

5. Biennial or perennial herb 1 0,65

Sum: 154 100

It is clear that from the table, perennial herbs are

dominated by 113 species (73,38 %), 21 species of

annual herbs (13,64 %) and 13 species of biennial herbs

(8,44%). Annual or biennial herbs have the least

number of 6 species (3,9 %), and biennial or perennial

herbs one species (0,65 %). Among these plants there

was not found semi-shrub, shrub or tree plants.

Scientific Light No 22, 2018 7

As a result of literature materials, collected

materials and surveys conducted on our territory by us,

a list of usage categories of wild vegetable plants

(example, fruits, vegetables, pickles) spread in the

Batabat massive of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

were prepared and revealed that, which species were

used for which purposes. During the investigations, it

was also studied additional purposes usage of the

species. The results of these researches are shown in

Table 5, Table 6, Table 7 and Table 8.

Table 5.

Various usage categories of wild vegetable plants spread in the

Batabat massive of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

№ Usage categories Species

1 2 3

1. Cooked as

vegetables

Thalictrum minus, Amaranthus retroflexus, Falcaria vulgaris, Echium russicum,

Polygonatum orientale, Orchis mascula, Eremurus spectabilis, Puschkinia

scilloides, Scilla mischtschenkoana, Arum rupicola

2. Eaten as raw

Crambe orientalis, Conringia orientalis, Lepidium sativum, Nasturtium officinale,

Sinapsis arvensis, Bunias orientalis, Cardamine uligunosa, Thlaspi arvense, Malva

neglecta, Trifolium pratense, Melilotus officinalis, Trifolium repens, Epilobium

angustifolium, Eryngium campestre, Eryngium billardieri, Cymbocarpum

anethoides, Laser trilobum, Echinophora orientalis, Tanacetum canescens,

Echinops shaerosephalus, Arctium lappa, Arctium tomentosum, Onopordum

acanthium, Taraxacum оfficinale, Sonchus oleraceus, Chondrilla juncea, Cousinia

macrocephala, Lactuca serriola, Lapsana communis, Picris hieracioides,

Cichorium intybus, İnula helenium, Centaurea Behen, Michauxia laevigata,

Campanula rapunculoides, Campanula latifolia, Asperugo procumbens, Veronica

anagallis-aquatica, Stachys officinalis, Humulus lupulus, Sempervivum

caucasicum, Alisma plantago-aguatica, Butomus umbellatus, Hordeum bulbosum,

Typha angustifolia, Triglochin polustre, Lemna minor

3. Used as spices

Persicaria hydropiper, Lepidium campestre, Descurainia sophia, Geum rivale,

Geum urbanum, Filipendula vulgaris, Filipendula ulmaria, Lathyrus miniatus,

Pimpinella saxifraqa, Pimpinella aromatica, Carum carvi, Achillea millefolium,

Artemisia vulgaris, Satureja macrantha, Satureja hortensis, Lamium album,

Origanum vulgare, Salvia sclarea, Thymus collinus, Cephalaria syriaca, Crocus

speciosus

4.

Both cooked as

vegetables and

eaten raw

Stellaria media, Silene italic, Chenopodium album, Chenopodium foliosum, Rheum

ribes, Oxyria digyna, Rumex crispus, Rumex alpinus, Rumex tuberosus, Rumex

acetosa, Rumex acetosella, Rumex scutatus, Rumex patientia, Polygonum

aviculare, Polygonum cognatum, Aconogonon alpinum, Persicaria birtorta,

Capsella bursa–pastoris, Barbarea vulgaris, Malva sylvestris, Urtica dioica,

Urtica urens, Potentilla recta, Vicia nissoliana, Cicer anatolicum, Geranium

tuberosum, Epilobium angustifolium, Chaerophyllum aureum, Anthriscus

cerefolium, Anthriscus sylvestris, Daucus corota, Gundelia tournefortii, Carduus

nutans, Scorzonera leptophylla, Scorzonera latifolia, Scorzonera cana, Scorzonera

laciniata,Tragopogon marginatus, Tragopogon latifolius, Tragopogon

sosnowskyi, Tussilago farfara, Convolvulus arvensis, Plantago major, Mentha

aquatica, Mentha longifolia, Primula veris subsp. macrocalyx, Solanum nigrum,

Merendera trigyna, Colchium raddeanum, Asparagus verticillatus, Equisetum

arvense

5. Both eaten as raw

and used as pickles

Caltha polypetala, Caltha palustris, Chaerophyllum bulbosum, Prangos acaulis,

Prangos uloptera, Bilacunaria microcarpa, Turgenia latifolia, Steotaenia

macrocarpa, Echinophora orientalis, Hylotelephium caucasicum, Ornithogalum

ponticum, Allium woronovii

6.

Both cooked as

vegetable and eaten

as raw, as well as

used as pickles

Portulaca oleracea, Heracleum pastinasifolium, Heracleum antasiaticum,

Heracleum trachyloma, Heracleum grandiflorm, Achillea tenuifolia, Allium

schoenoprasum, Allium rotundum, Allium atroviolaceum, Allium fuscoviolaceum,

Allium rubellum, Allium pseudoflavum, Allium akaka

8 Scientific Light No 22, 2018

Table 6.

Different usage categories of wild vegetable plants spread in Batabat massive

of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

№ Usage categories Number of

Taxons Number of

taxons by %

1. Cooked as vegetables 10 6,49

2. Eaten as raw 47 30,52

3. Used as spices 21 13,64

4. Both cooked as vegetables and eaten raw 51 33,12

5. Both eaten as raw and used as pickles 12 7,79

6. Both cooked as vegetable and eaten as raw, as well as used as pickles 13 8,44

Sum: 154 100

The usage categories of wild vegetable plants

spread in the Batabat massive of Shabuz district of

Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic was analyzed in six

groups, most of which are both cooked as vegetables

and are eaten in raw [51 species, 33,64 %], and the

second place is in the category is only eaten as raw [47

species, 30,52 %]. Other categories, used as spices: 21

species, 13,64 %; both cooked as vegetable and eaten

as raw, as well as used as pickles: 13 species, 8,44 %;

both eaten as raw and used as pickles: 12 species, 7,79

%; and only 10 species, 6,49 % were cooked as

vegetables [Table 6].

Table 7.

Classification of wild vegetable plants according to their usage parts spread

in the Batabat massive of the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

№ Usage parts of wild

vegetable plants Species

1. Young shoots and flowery stems

Thalictrum minus, Caltha polypetala, Rheum ribes, Aconogonon alpinum, Cardamine uligunosa, Chaerophyllum aureum, Prangos acaulis, Prangos uloptera, Bilacunaria microcarpa, Heracleum pastinasifolium, Heracleum antasiaticum, Heracleum trachyloma, Heracleum grandiflorm, Laser trilobum, Echinophora orientalis, Gundelia tournefortii, Tanacetum canescens, Artemisia vulgaris, Centaurea Behen, Michauxia laevigata, Convolvulus arvensis, Polygonatum orientale, Hordeum bulbosum, Asparagus verticillatus, Equisetum arvense

2. Young shoots and leaves

Portulaca oleracea, Stellaria media, Silene italica, Chenopodium album, Oxyria digyna, Rumex crispus, Rumex acetosella, Rumex patientia, Polygonum aviculare, Polygonum cognatum, Capsella bursa–pastoris, Conringia orientalis, Nasturtium officinale, Sinapsis arvensis, Bunias orientalis, Urtica dioica, Urtica urens, Potentilla recta, Vicia nissoliana, Lathyrus miniatus, Turgenia latifolia, Falcaria vulgaris, Scorzonera latifolia, Achillea millefolium, Sonchus oleraceus, Chondrilla juncea, Cousinia macrocephala, Lactuca serriola, Lapsana communis, Picris hieracioides, Cichorium intybus, Cirsium alatum, Campanula latifolia, Asperugo procumbens, Plantago major, Satureja macrantha, Satureja hortensis, Mentha aquatica, Mentha longifolia, Lamium album, Humulus lupulus, Hylotelephium caucasicum, Cephalaria syriaca, Triglochin polustre, Lemna minor

3. Leaves

Rumex alpinus, Rumex tuberosus, Rumex acetosa, Rumex scutatus, Persicaria hydropiper, Barbarea vulgaris, Lepidium campestre, Lepidium sativum, Thlaspi arvense, Filipendula ulmaria, Melilotus officinalis, Epilobium montanum, Cymbocarpum anethoides, Veronica anagallis-aquatica, Origanum vulgare, Salvia sclarea, Thymus collinus, Primula veris subsp. macrocalyx, Sempervivum caucasicum, Eremurus spectabilis, Puschkinia scilloides, Scilla mischtschenkoana, Allium schoenoprasum, Allium rotundum, Allium atroviolaceum, Allium fuscoviolaceum, Allium rubellum, Allium pseudoflavum, Allium akaka, Allium woronovii

4. Rhizomatous and roots

Caltha palustris, Persicaria birtorta, Geum rivale, Daucus corota, Echium russicum, Merendera trigyna, Colchium raddeanum, Alisma plantago-aguatica, Butomus umbellatus, Typha angustifolia, Crocus speciosus, Ornithogalum ponticum, Arum rupicola

5. Young shoots, leaves and fruits

Chenopodium foliosum, Descurania sophia, Malva neglecta, Malva sylvestris, Cicer anatolicum, Pimpinella aromatica, Solanum nigrum,

6. Leaves and flowers

Geum urbanum, Filipendula vulgaris, Trifolium pratense, Trifolium repens, Geranium tuberosum, Echinops shaerosephalus, Onopordum acanthium, Carduus nutans, Tussilago farfara, Taraxacum оfficinale, Achillea tenuifolia, Stachys officinalis, Orchis mascula

7. Young shoots, leaves and seeds

Amaranthus retroflexus, Pimpinella saxifraqa, Carum carvi, Stenotaenia macrocarpa

8. Young leaves, shoots and roots

Crambe orientalis, Epilobium angustifolium, Chaerophyllum bulbosum, Eryngium campestre, Eryngium billardieri, Anthriscus cerefolium, Anthriscus sylvestris, Arctium lappa, Arctium tomentosum, Scorzonera leptophylla, Scorzonera cana, Scorzonera laciniata, Tragopogon marginatus, Tragopogon latifolius, Tragopogon sosnowskyi, İnula helenium, Campanula rapunculoides

Scientific Light No 22, 2018 9

Table 8.

Frequency of wild vegetable vegetable plants according to usage parts

spread in Batabat massive of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic

№ Usage parts of wild vegetable plants Number of taxons Number of taxons by %

1. Young shoots and flowery stems 25 16,23

2. Young shoots and leaves 45 29,22

3. Leaves 30 19,48

4. Rhizomatous and roots 13 8,44

5. Young shoots, leaves and fruits 7 4,55

6. Leaves and flowers 13 8,44

7. Young shoots, leaves and seeds 4 2,60

8. Young leaves, shoots and roots 17 11,04

Sum: 154 100

As can be seen from the table [Table 8], the most

commonly used parts of wild vegetable plants among

the population were young shoots and leaves (45

species; 29,22 %) in first place, and only leaves (30

species; 19,48 %) in second place. Other categories, in

turn: young leaves, shoots and roots were 17 species,

11,04 %; leaves and flowers 13 species, 8,44 %; young

shoots, leaves and fruits 7 species, 4,55 %; young

shoots, leaves and seeds representing by 4 species,

2,60 %.

REFERENCES

1. Asgarov A.M. The Higher Plants of

Azerbaijan (The conspectus of the flora of Azerbaijan):

3 volumes, I v., Baku: Science, 2005, 248 pp. (in

azerbaijani language)

2. Asgarov A.M. The Higher Plants of

Azerbaijan (The conspectus of the flora of Azerbaijan):

3 volumes, II v., Baku: Science, 2006, 284 pp. (in

azerbaijani language)

3. Asgarov A.M. The Higher Plants of

Azerbaijan (The conspectus of the flora of Azerbaijan):

3 volumes, III v., Baku: Science, 2008, 244 pp. (in

azerbaijani language)

4. Gasimov Hilal, Ibadullayeva Sayyara,

Seyidov Mursel, Shiralieva Gulnara. Wild vegetable

plants of Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.

Nakhchivan: Ajami, 2018, 400 pp. (in azerbaijani

language)

5. Seyidov Mursal, Ibadullayeva Sayyara,

Gasimov Hilal, Salayeva Zulfiyya. The flora and

vegetation of Shahbuz State Nature Reserve.

Nakhchivan: Ajami, 2014, 523 pp. (in azerbaijani

language)

6. Talibov T.H., Ibragimov A.Sh. Taxonomic

spectrum of the flora of Nakhchivan Autonomous

Republic. Nakhchivan: Ajami, 2008, 364 pp. (in

azerbaijani language)

7. Гроссгейм А.А. Флора Кавказа: Т. 1-7, М.-

Л.: Из-во АН СССР, 1936-1967

8. Гроссгейм А.А. Определитель растений

Кавказа. М.: Сов. Наука, 1949, 747 с.

9. Конспект флоры Кавказа: Т. 1 / Под ред.

Ю.Л.Меницкий, Т.Н.Попова. СПб.: С-Петерб. ун-

та, 2003, 204 с.

10. Конспект флоры Кавказа: Т. 2 / Под ред.

Ю.Л.Меницкий, Т.Н.Попова. СПб.: С-Петерб. ун-

та, 2006, 467 с.

11. Международный кодекс ботанической но-

менклатуры (Сент-Луисский кодекс) // Принятый

шестнадцатым Международным ботаническим

конгрессом, Сент-Луис, Миссури, июль-август

1999 г. Перевод с английского. СПб.: Изд-во

СПХФА, 2001. 210 с.

12. Новинков Б.С., Губанов И.А. Школный ат-

лас-определитель высщих растений. М.: Просвеще-

ние, 1991, 240 с.

13. Серебряков И.Г. Жизненные формы выс-

ших растений и их изучение. В кн.: Полевая геобо-

таника. М.: АН СССР, 1964, т. 3, 530 с.

14. Флора Азербайджана: Т. 2-8, Баку: Из-во

АН Азерб. ССР, 1952-1961

15. Флора СССР: Т. 1-30, М.: Из-во АН СССР,

1934-1967

16. Черепанов С.К. Сосудистые растения Ро-

сии и сопредельных государств. СПб.: Мир и семя,

1995, 992 с.

17. Ehrlich PR, Ehrlich AH. The value of biodi-

versity. AMBIO. 1992;21:219–226

18. Ali-Shtayeh MS, Jamous RM, Al-Shafie JH,

Elgharabah WA, Kherfan FA, Qarariah KH, Khdair IS,

Soos IM, Musleh AA, Isa BA, Herzallah HM, Khlaif

RB, Aiash SM, Swaiti GM, Abuzahra MA, Haj-Ali

MM, Saifi NA, Azem HK, Nasrallah HA. Traditional

knowledge of wild edible plants used in Palestine

(Northern West Bank): a comparative study. J Ethno-

biol Ethnomed. 2008;4:13. doi: 10.1186/1746-4269-4-

13

19. Ndanikou S, Achigan-Dako EG, Wong JLG.

Eliciting local values of wild edible plants in Southern

Bénin to identify priority species for conservation. Eco

Bot. 2011;65(4):381–395. doi: 10.1007/s12231-011-

9178-8

20. Haddad L, Oshaug A. How does the human

rights perspective help to shape the food and nutrition

policy research agenda Food Pol. 1999;23:329–345

21. Yan Ju, Jingxian Zhuo, Bo Liu and, Chun-

lin Long. Eating from the wild: diversity of wild edible

plants used by Tibetans in Shangri-la region, Yunnan,

China. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine,

2013, pp. 9-28

22. http://www.theplantlist.org/

23. http://www.catalogueoflife.org/

24. http://media.eol.org/

This work was supported by the Science Develop-

ment Foundation under the President of the Republic of

Azerbaijan –

Grant № EİF/GAM-4-BGM-GİN-2017-3(29)-

19/12/4

10 Scientific Light No 22, 2018

PEDAGOGICAL SCIENCES

УДК373.2.091.33

ВИКОРИСТАННЯ МУЛЬТИМЕДІЙНИХ ЗАСОБІВ У ФОРМУВАННІ ІНТЕРЕСУ ДО

НАВЧАННЯ В ДІТЕЙ ДОШКІЛЬНОГО ВІКУ

Курчатова А. В.

кандидат педагогічних наук, старший викладач кафедри дошкільної освіти

Миколаївський національний університет ім. В. О. Сухомлинського

USE OF MULTIMEDIA IN FORMATION OF INTEREST IN LEARNING OF PRESCHOOL AGE CHILDREN

Kurchatova A.

PhD, Senior Lecturer of Preschool Education Department

Mykolaiv V.O.Sukhomlynskyi National University

Abstract:

The problem of forming interest in learning in preschool children through the use of multimedia tools is

considered in this article. The results of theoretical analysis accumulated in preschool pedagogy, the experience

of using multimedia facilities in the educational process of the preschool education institution are presented. The

features and advantages of using multimedia means of teaching in the educational process of the institution of

preschool education are determined. Examples of multimedia learning tools that can be used in preschool estab-

lishments to form interest in learning in preschool children are given.

Key words: multimedia, multimedia teaching aids, interest in learning, children of preschool age.

The Problem. Modern education meets a com-

plex task such as the formation of a fully developed per-

sonality, capable of creative processing of the acquired

knowledge, to self-education, independent search for

non-standard solutions and new ways of obtaining

knowledge. The processes of informatization and com-

puterization, which are in all spheres of society, cause

changes in the approaches to the organization of cogni-

tive activity of children, starting from preschool age. To

achieve the best results in education and upbringing, it

is necessary to develop cognitive activity, to form in-

terest in preschool children to new information. Thus,

there is a need to use new learning tools, as the pre-

school age is considered the most desirable for the de-

velopment of child’s cognitive activity and creative po-

tential.

The specifics of the training of preschoolers is the

visualization of educational material, and one of the

most effective ways of providing it today is a graphic-

minded approach with the help of multimedia. Accord-

ing to researchers (G. Vorobyov, E. Golubeva,

T. Gurleva, V. Korobeynikov, K. Krutiy, S. Sterdenko,

V. Schmidt), it is possible to combine different kinds of

information representation (text, static and dynamic

graphics, video and audio) into a single complex with

the help of modern multimedia means, which makes the

child participate in the educational process. The study

of foreign and domestic scientists (A. Birukovich,

Yu. Horwitz, S. Dyachenko, I. Mardarova, V. Motor-

ina, S. Novoselova, etc.) suggests that the use of multi-

media facilities in educational process of preschool ed-

ucation institution is possible and necessary, it in-

creases interest in learning, its effectiveness, develops

the child comprehensively. As practice shows, the use

of multimedia in the institution of preschool education

is still limited and weakly related to the educational

process.

The Purpose of the article is to substantiate the

use of multimedia in the educational process of the in-

stitution of preschool education, to reveal the possibil-

ity of using multimedia means in the process of for-

mation the interest in teaching children of preschool

age. The multimedia teaching tools allow deeper devel-

opment of the child's reserves, allow the educator to

work creatively, initially, with greater professional

skills.

The concept of "multimedia" in this context is key

and can be interpreted as "... the interaction of visual

and audio effects under the control of interactive soft-

ware using modern technical and software tools, they

combine text, sound, graphics, photos, videos in a sin-

gle digital representation. [1, p.27]. For our study, it is

important to define the concepts of "multimedia tech-

nologies", "multimedia learning tools". O. Buynitskaya

and S. Goncharenko [2; 3] define the term "multimedia

technologies" as technologies that enable the computer

to integrate, process and simultaneously reproduce var-

ious types of signals, different environments, means of

information exchange [2]; "Multimedia learning tools"

is a set of hardware and software that allows the user to

work with a computer using a variety of environments:

graphics, hypertexts, sound, animation, video [3,

p.298]. The use of multimedia learning tools ensures

the individualization and differentiation of learning,

taking into account the peculiarities of children, their

inclinations.

Application of multimedia tools in the pedagogy

was studied by B. Bespalko, L. Morska, N. Rotmystrov,

G. Schetzer. For example, N. Rotmystrov believes that

multimedia computer software allows us to approach

Scientific Light No 22, 2018 11

the transformation of a computer into a powerful means

of education in which all aspects of the learning process

are modeled from methodical to presentation [7, p.89].

The research of the possibilities of introduction and use

of multimedia means for the teaching of preschool chil-

dren is devoted to the work of such researchers:

Zh. Matyukh (introduction of multimedia technologies

in inclusive preschool education) [5]; Y. Nosenko (use

of information and communication technologies in in-

clusive pre-school education) [6]; M. Kovalchuk (mul-

timedia means in the system of professional activity of

future educators of the preschool education institution

(PEI)) [4]; L. Zimnukhova (use of ICT in educational

process in PEI); S. Frolova (mediadactic and technical

means at the service of a teacher) [8]; S. Semchuk

(computer technologies of education and upbringing of

preschool age children).

Using multimedia means of teaching children of

preschool age becomes more attractive and exciting.

Multimedia media greatly expands the possibilities of

presenting educational information, designed to inspire

and encourage children to acquire new knowledge.

L. Zimnukhova believes that multimedia means of

teaching can create comfortable conditions for display-

ing the content of classes, increase informativity, stim-

ulate learning motivation, attract interest, use visuality

in teaching, perform repetitions and short episodes,

provide accessibility of visual and auditory information

perception.

The main technical multimedia means is a com-

puter equipped with the necessary software and a mul-

timedia projector. Curiosity is one of the sources of mo-

tivation for performing creative tasks in preschool chil-

dren. With the help of a computer, you can significantly

change the methods of teaching management, immers-

ing preschoolers in a certain game situation, which is

based on the creation of an imaginary situation and the

adoption of children or the teacher of any role. So, for

example, in the lesson "A Journey to Space", the heroes

voices from the screen puzzle children and invite them

to a great journey through space. Children are curiously

taking the image of the astronauts and, "while in outer

space," create an application of what they see in space,

applying creative abilities in the image of planets, com-

ets, and stars.

With animated images in the presentation, you can

display different image variants of any objects or their

individual parts, add design elements, change the size,

color and shape. And children, through selection and

experimentation, determine what non-traditional mate-

rial it can be depicted with. For example, in work on the

theme "House of my dreams" you can show in the

presentation houses of different sizes, colors, designs,

etc. Preschoolers, seeing a variety of options, inde-

pendently devise the image of their house of the

dreams.

It is advisable to use the projector, when teacher

introduces children to the works of fine arts and the cre-

ativity of artists. Introducing children with works by

K. Bilokur, O. Shovkunenka, M. Glushchenka,

I. Shishkina, toys and utensils of Opishniansky paint-

ing, the teacher can create a game situation and, taking

on the role of a guide, invite senior preschool children

to one of the halls of the art gallery. Children who look

at the screen and listen to the educator, use both audi-

tory and visual memory at the same time, which in-

creases their quality of perceiving information. With

the help of a large format, preschoolers can look at the

pictures in more detail, group them and return to any

picture.

The Microsoft Power Point multimedia presenta-

tion is one of the most effective means of presenting

educational material for classes in all fields of study.

Sometimes didactic and illustrative material in pre-

school establishments practically does not meet modern

requirements. And it is at this stage that multimedia and

online resources will help, as they combine sound, im-

age and dynamics, which are factors that instantly in-

terest and keep the child's attention much longer. The

use of multimedia presentations at classes with children

makes it possible to optimize the pedagogical process,

to individualize the education of children with different

levels of cognitive development and significantly in-

crease the efficiency of pedagogical activity. The con-

tent of the presentation is determined by the content of

the form of organization of the educational process

(classes, various events), where it is used.

For example, in classes on fine art during the ac-

quaintance of preschoolers with the subjects of folk ap-

plied art on the theme "Petrykivsky painting", it is ad-

visable to make a presentation "History of the Petrykiv

painting". Looking at it, preschoolers are fully ac-

quainted with the variety of subjects with petrykiv

painting, the stages of their creation, the elements of

painting, which serves as an incentive for creative ac-

tivity.

During the study of the topic "Wild Animals" for

children, the video recording "The fascinating world of

African animals", a presentation "Secrets of the Zoo-

logical Park of Pretoria" is organized. Multimedia tools

help children to become more interested in and learn,

because with their help they simultaneously perceive

the agreed stream of sound and visual images.

Educators use two types of multimedia presenta-

tions in working with children: linear and interactive. A

linear presentation represents a consistent slide change.

And interactive can consist of one or several slides, de-

pending on the given didactic task. Interactive multi-

media presentations allow you to conveniently and ef-

fectively present information. They combine the factors

that keep the attention of the preschool age child:

sound, dynamics, images (for example, interactive mul-

timedia presentations "What a cat feeds", "Trees and

bushes"). Similar multimedia presentations allow the

instructor to simulate different situations of the sur-

rounding world, while developing the creative and cog-

nitive abilities of preschool children, causing interest in

the subject under study.

Presentation materials are introduced into tradi-

tional lessons and are an additional means of teaching

children. The use of color, graphics, animation, and

sound at classes enhances motivation, allows you to

quickly and easily portray phenomena that the teacher

cannot translate into words, causes enormous interest in

children to acquire new knowledge, and helps to more

effectively master the learning material.

12 Scientific Light No 22, 2018

For educators who organize educational activities

using multimedia, it is important to clearly understand

how appropriate is the use of presentation in this lesson;

for what purpose and for solving of what tasks, the

given visual means is directed; if the content of the

presentation correspond to the age-specific characteris-

tics of children.

For the formation of interest in education of pre-

school age children it is expedient to use the multime-

dia educational system EduPlay in order to develop

communicative, social and cognitive competences.

Various didactic materials (cubes, blocks, figures, puz-

zles) included in the system allow preschoolers to per-

form various tasks:

- speech development (the expansion and enrich-

ment of the vocabulary, the development of coherent

speech, the formation of grammatically correct speech,

training for reading and writing);

- social and communicative development (the for-

mation of positive self-esteem, the assimilation of

norms of behavior in society, the formation of respect

for work and creativity);

- sensory-cognitive development (the develop-

ment of elementary mathematical notions of quantity,

size, form, acquaintance with colors, acquaintance with

the number and date, the development of spatial per-

ception and orientation, the formation of the ability to

recognize, call geometric figures, create a variety of

models, pictures of these figures, compare the number

of items).

EduPlay multimedia education system consists of

12 thematic modules. The mentor/ educator orally ex-

plains the training information. Kids initially deal with

didactic materials, and then consolidate their

knowledge with the help of computer. Basic topics

taught are colors, vocabulary, alphabet, orientation in

space, the world of nature, whole and parts, numbers.

In work with preschoolers of different ages the follow-

ing blocks are used: "Getting to know the directions",

"Our world in words", "Butterflies", "Colors and spatial

orientation", "Geometric figures", "Whole and parts",

"Nature in puzzles" , "Mathematical notions", "Intro-

duction to the letters of the English alphabet".

It is advisable to use didactic games to form sen-

sory standards in junior preschoolers using the EduPlay

system: "Pick a house for a triangle (square)", "Find a

figure", "Find a figure and paint it", "Creative model-

ing". In the game "Find a figure" children need to re-

member the geometric figure that appears for a short

time on the screen and find it among the figures on the

table. In the game "Find a figure and paint it" there is a

partially colored picture on the screen. Children are in-

vited to find similar shapes and paint them. In the game

"Creative modeling" children are suggested first to in-

vent and create a picture on a plastic mat using the di-

dactic materials, and then play this image on the screen.

An interactive whiteboard is a convenient multi-

media tool for forming the interest in teaching pre-

school children in a preschool education institution.

The use of this equipment allows the teacher to quickly

engage the learner with learning information and keep

their attention longer. Children, using vivid large im-

ages, operating geometric shapes, various objects with

their fingers, become interactive participants in "live"

learning. Throughout the class there is a steady cogni-

tive interest, as the educational material offered to chil-

dren is distinguished by the visibility, brightness of ob-

jects and dynamism.

With the help of multimedia way of presenting in-

formation, children of preschool age easier learn the

concept of form and color; deeper understand the con-

cept of number and set; the ability to navigate, to ori-

etate in space is formed more quickly; attention and

memory are trained; vocabulary is actively replenished.

Work with the interactive whiteboard includes di-

dactic games and exercises, communicative games,

problem situations, creative tasks, mastering of sym-

bols, models, mnemotechnology. It is advisable to use

such games as "Be careful", "Find fairy-tale heroes",

"Vegetable and vegetable seeds", "Find the same pic-

tures", "Let's think", "Continue the row", "Find extra"

in the work with the children of preschool age. For ex-

ample, in the game "Multi-colored buckets" on a slide

with colorful buckets children are asked to fill them

with geometric shapes in color, shape or size. Children

with enthusiasm and interest, performed the proposed

tasks near the board, were more responsible for the

quality of the task.

The use of an interactive whiteboard in the com-

mon and independent activity of the child is one of the

effective ways of motivating and individualizing the

learning, developing creative abilities and creating a fa-

vorable emotional background.

Conclusions. Multimedia education in the educa-

tional process of preschool education is not a tribute to

the fashion. The widespread use of multimedia means

of learning is due to the specifics of the modern infor-

mation space and its interaction with children of pre-

school children. Multimedia education is a promising

and highly effective tool that allows information to be

provided to a greater extent than traditional sources of

information and in a sequence consistent with the logic

of cognition and the level of perception of a particular

contingent of children. The use of multimedia means

transforms classes into live action, which causes sin-

cere interest in children of preschool age and captures

them with investigative information. Children see, per-

ceive, act, and experience. Once the things that inter-

ested children and caused them emotional feedback,

they become their own knowledge, serve as an impetus

for further discoveries and contribute to a more creative

approach to the tasks.

REFERENCES

1. Bazovi ponyattya i terminy veb-tekhnologij

[Basic concepts and terms of web technologies] /

[A.V. Kilchenko, O.I. Popovsky, O.V. Tebenko, O.V.

Tebenko, N.M. Matrosov]; Uporyadnyk

[Administrator]: Kilchenko A.V. - K.: IITZN NAP

Ukraine, 2014 - 49 p.

2. Buynitskaya O.P. Informatsijni tekhnologiyi

ta tekhnichni zasoby navchannya [Information technol-

ogies and technical means of training] / О.P. Buynitsky

// Navch. Posib. [Teaching manual] - K.: Center for Ed-

ucational Literature, 2012. - 240 p.

Scientific Light No 22, 2018 13

3. Goncharenko S.U. Ukrayinskyj pedagogich-

nyj entsyklopedychnyj slovnyk [Ukrainian Pedagogi-

cal Encyclopedic Dictionary] / S.U. Goncharenko -

Rivne: Volyn Amber, 2011. - 552 p.

4. Kovalchuk M.O. Multymedijni tekhnologiyi v

systemi profesijnoyi diyalnosti majbutnikh vyhovateliv

DNZ ta vchyteliv pochatkovoyi shkoly: [navchalno-

metodychnyj posibnyk] Multimedia technologies in the

system of professional activity of future schoolchildren

and primary school teachers: [instructional manual] /

M.O.Kovalchuk. - Zhytomyr: View at ZHDU them. I.

Franko, 2016. - 94 p.

5. Matyukh Zh.V. Problemy ta perspektyvy

vprovadzhennya multymedijnyh tehnologij v

inklyuzyvnu doshkilnu osvitu / Zh.V. Matyukh // Novi

texnologiyi navchannya: nauk.-metod. zb. / Instytut in-

novacijnyh tekhnologij i zmistu osvity MON Ukrayiny

[Problems and prospects of introduction of multimedia

technologies in inclusive pre-school education / Zh.V.

Matyuk // New technologies of teaching: science-

method. save / Institute of Innovative Technologies and

Educational Content of the Ministry of Education and

Science of Ukraine]. - K., 2016. - Vip. 88. - Ch.1 -

2016. - P. 65-69.

6. Nosenko Yu.G. Stan vykorystannya multy

medijnyh tekhnologij vyhovatelyamy vitchyznyanyh

doshkilnyh navchalnyh zakladiv u roboti z inklyuzyv-

noyu grupoyu [Elektronnyj resurs] [The state of the use

of multimedia technologies by educators of domestic

preschool educational institutions in work with the in-

clusive group [Electronic resource] / Yu.G. Nosenko,

Zh.V. Matyukh // Informatsijni tekhnologiyi i zasoby

navchannya [Information technologies and means of

training]. - 2017. - No. 1 (57). – Rezym dostupu [Ac-

cess mode]: https://journal.iitta.gov.ua/in-

dex.php/itlt/article/ view / 1523/1131

7. Rotmystrov N.D. Multymedya v obrazovanyy

[Multimedia in Education] / N.D. Rotmystrov // Yn-

formatyka y obrazovanye. [Computer science and

education]. - 1994. - № 4. - C. 89-96.

8. Frolova S. Mediady`dakty`chni ta texnichni

zasoby` na sluzhbi v pedagoga [Meddidactic and tech-

nical means at the service of the teacher] / Svetlana

Frolova // Doshkilne vyhovannya [Preschool educa-

tion]. - 2018. - No. 5. - P. 9-11.

14 Scientific Light No 22, 2018

PHILOLOGY

ГЛАГОЛЫ, ОПИСЫВАЮЩИЕ КОНЦЕПТ «ЛЮБОВЬ»

В РУССКОМ ЯЗЫКЕ И АНГЛИЙСКОМ ЯЗЫКАХ

(лексико-семантический аспект)

Кузнецова Л. Э.

кандидат филологических наук,

доцент кафедры иностранных языков и методики их преподавания,

Армавирский государственный педагогический университет, г. Армавир

THE PREDICATES REPRESENTING CONCEPT "LOVE" IN THE RUSSIAN AND ENGLISH LANGUAGES

(lexico-semantic aspect)

Kuznetsova L.

PhD (Philology), Associate Professor,

Foreign Languages and Teaching Methods Department,

Armavir State Pedagogical University, Armavir

Аннотация:

Цель исследования заключается в том, чтобы на основе анализа словарных статей в русских и англий-

ских толковых словарях и примеров, взятых из художественной литературы ХХ века, установить мини-

мальное инвариантное лексико-семантическое содержание, присущее глаголам-предикатам, описываю-

щих концепт «любовь». Анализ показывает, что словарные значения предикатов любви в русском и ан-

глийском языках осуществляются при помощи лексико-грамматического контекста на уровне

словосочетания. В ряде основных лексико-семантических вариантов предиката «любить/to love» присут-

ствуют прежде всего переживание центральности объекта любви, а также романтическая любовь (на пер-

вом месте), родственная любовь к другу, любовь к ближнему, любовь к Богу.

Abstract:

The aim of the research is to analyse the dictionary entries оf Russian and English dictionaries as well as the

examples taken from the fiction of the twentieth century and to find out the minimum invariant lexical-semantic

content inherent in each of the predicates representing the concept "love". The analysis shows that the dictionary

meanings of the love predicates in Russian and English are implemented using the lexico-grammatical context at

the level of the word combination. In a number of basic lexical and semantic variants of the predicate «любить/to

love» there are first of all an experience of the centrality of the object of love, as well as romantic love (rank 1), a

kinship with one another, love of one's neighbor, love of God.

Ключевые слова: концепт; любовь; предикат; лексико-семантический анализ; семантический при-

знак; синонимический ряд.

Keywords: concept; love; predicate; lexico-semantic analysis; semantic sign; synonymic line.

Привлекательность концепта «любовь» в кон-

кретном языке для сопоставительного анализа

определяется его компонентным богатством и

связностью с культурно-социологическим аспек-

том языка. При этом, «грамматика любви – это

прежде всего грамматика глагола-предиката

по/воз/любить» [1, C.79].

Задача данной статьи сводится к тому, чтобы

на основе анализа словарных статей в русских и ан-

глийских толковых словарях и примеров, взятых из

художественной литературы ХХ века, установить

минимальное инвариантное лексико-семантиче-

ское содержание, присущее каждому из глаголов-

предикатов, описывающих концепт «любовь», а

также проанализировать языковой механизм про-

исхождения разных переменных смыслов, возника-

ющих в процессе их функционирования в языках.

«Предикаты любви» занимают важное место в

системе английского языка, так как они описывают

«самую естественную для человека страсть» (Б.

Паскаль), при этом «to love» принадлежит к наибо-

лее употребительной языковой лексике, его частот-

ность приближается к рангу служебных слов. По

данным компьютерного анализа издательства

Longman глаголы to love и to like входят в первую

тысячу слов разговорной и письменной речи как в

британском, так и в американском вариантах ан-

глийского языка.

В семантической структуре глагола «любить»

в русском языке принято выделять два режима

функционирования. В первом режиме глагол «лю-

бить» указывает на чувство, которое субъект испы-

тывает по отношению к объекту любви (любить

жену, мать, брата, сестру); во втором режиме – на

свойство субъекта, состоящее в том, что субъект

обычно испытывает удовольствие от реализации

некоторой ситуации (любить прогулки по лесу, лю-

бить покушать и т.д.).

Таким образом, любить 1 относится к сфере

«высокого», а любить 2 – к сфере «низкого» [2,

C.427]. Объектом нашего исследования является

Scientific Light No 22, 2018 15

глагол любить 1, так как мы исследуем любовь как

межличностное чувство (материнская любовь,

братская любовь, отцовская любовь и т.д.).

А. Д. Шмелев отмечает, что «в рамках любить

1 можно было бы различать «чувственную» лю-

бовь, в которой на первом плане желание быть вме-

сте с объектом любви (прототипической для такой

любви является любовь к человеку противополож-

ного пола, связанная со стремлением к физической

близости), и «альтруистическую» любовь, в кото-

рой на первом плане желание делать объекту любви

добро. Впрочем, вероятно, речь может идти о более

или менее детальной классификации чувств, кон-

цептуализуемых как любовь, – так, Владимир Со-

ловьев различал альтруистическую любовь (к

ближнему), основанную на жалости, и благоговей-

ную любовь (к Богу)» [2, C.428].

Так, Ю. Д. Апресян различает значения лю-

бить 1.1 (любить жену, полюбить циркачку) и лю-

бить 1.2. (любить Родину, любить своих детей).

Именно с любить 1.1., по Ю. Д. Апресяну, соотно-

сится один из самых фундаментальных концептов

языковой картины мира – «идеальная любовь», ко-

торая мыслится в русском языке как исключи-

тельно сильное и глубокое чувство, испытываемое

однажды в жизни по отношению к единственному

человеку другого пола, связанное с наличием физи-

ческой близости или стремлением к ней, поднятое

над бытом и способное дать человеку ощущение

счастья. Ю. Д. Апресян указывает на ряд языковых

свойств, отличающих любить 1.1. от других значе-

ний глагола любить и, в частности, от любить 1.2.:

возможность употребляться в «длительном» значе-

нии (находиться в состоянии влюбленности), упо-

требительность определенных причастных форм

(например, формы любящие), соотнесенность с суб-

стантивированными прилагательными (любимый),

способность употребляться в абсолютивной кон-

струкции (Они умеют любить) и т.д.

При некоторых различиях в подходе к глаголу

любить, в целом именно чувство, обозначаемое

глаголом любить 1 (в обеих разновидностях: лю-

бить 1.1. и любить 1.2.), является в культуре выс-

шей духовной ценностью, приобщающей человека

к миру «высокого».

На настоящем этапе развития лингвистической

науки, глаголы, отражающие концепт «любовь»,

принято относить к глаголам «эмоциональной

связи» (по семантической классификации О. Н. Се-

ливерстовой). Однако ряд лингвистов включает та-

кие глаголы в класс глаголов-состояний или стати-

вов). «Стативами (stative verbs) считаются только те

предикаты, которые обозначают свойства, не про-

являющиеся по воле носителя. Глаголы с таким

лексическим значением не выражают ни действия,

ни процесса» [3, C.110].

Наши исследования показывают, что глаголы,

описывающие концепт «любовь», не могут быть от-

несены к классу предикатов состояния в полном

смысле, поскольку, например, предикат «любить»

может сочетаться с добавочными средствами авто-

ризации «сильно/очень/страшно/сильнее…». В то

же время предикат «to love» сравнительно свободно

сочетается с наречными усилителями типа

«deeply/wholly/awfully/terribly/really» т. д.: «Well» –

he said, holding himself hard together, – «don’t forget

I love you awfully» (J. Galsworthy); I loved once abso-

lutely. Then there was Clement, eternal wonderful un-

classifiable Clement. And I have been madly infatuated

(I. Murdoch).

Эта сочетаемость позволяет судить о том, что

денотат глаголов «любить/to love» представлен в

языковом сознании как протекающий неравно-

мерно и неравнозначно во времени. Таким образом,

эти глаголы представляются не статичными, а ди-

намичными. Чувство любви течет во времени, хотя

время часто бывает абстрактно, т. е. предикаты

любви можно рассматривать как «не имеющие ак-

туального времени или имеющие значение вневре-

менности» [3, C.113].

Примеры осмысления любви в терминах кау-

зативного движения встречаем на страницах ан-

глийской и русской художественной прозы: How

far has it gone? – There you go! – said Soames. – Not

any way so far as I know (J. Galsworthy); We are stuck.

(Lakoff); «Это их любовь приняла обратное разви-

тие и, не дозрев до конца, стала деградировать,

пока не умерла» (В. Токарева); «Лора почувство-

вала, как будто кто-то взял ее за плечи руками в

мягких варежках и тихо толкнул к этим глазам. Го-

ворят, есть выражение: потянуло» (В. Токарева).

Описание семантики глаголов в английском

языке отличается не только количественными раз-

личиями, но также толкованием и последователь-

ностью значений у разных авторов. Например,

Longman Dictionary в первом значении глагола to

love дает: Romantic attraction – to have a strong feel-

ing of caring for and liking someone, combined with

sexual attraction: I love you, really.

В остальных английских толковых словарях

сема «сексуальная привлекательность субъекта»

отсутствует вовсе. Например, Wordsworth Diction-

ary дает следующее значение: to be (very) fond of:

She loves her children; Oxford Advanced Learner’s

Dictionary: have strong affection or deep tender feel-

ings for … (one’s parents, one’s country); Active Study

Dictionary of English: 1. worship (God); love deeply

and respect highly.

Среди предикатов синонимического ряда кон-

цепта «love» можно обнаружить предикаты, обо-

значающие эмоциональное отношение (to love, to

like, to adore), а также предикаты типа «to cherish»,

«to bewitch», «to wither», которые описывают эмо-

циональное поведение. При этом предикаты эмоци-

онального поведения имеют активный субъект,

направленный на объект либо на описание поведе-

ния другого объекта, несут либо отрицательную,

либо положительную оценку, описывают опреде-

ленный способ манифестации действия (поступки,

жесты, слова), имеют причину и цель – вызвать от-

рицательное/положительное состояние (отноше-

ние) у того, кому такая информация адресована. В

связи с этим предикаты любви трудно поддаются

семному анализу из-за одновременного присут-

ствия в них двух структурно-семантических аспек-

тов – аспекта субъекта и аспекта объекта.

16 Scientific Light No 22, 2018

Граница между предикатами, обозначающими

эмоциональное отношение и предикатами, описы-

вающими эмоциональное поведение, довольно про-

зрачна. Причина этого кроется, вероятно, в разно-

образии и неустойчивости семантических призна-

ков предикатов концепта любви: I felt an agony of

protective possessive love, and such a deep pain to

think how I had failed defend her from a lifetime of un-

happiness. How would cherish her, how console her

and perfectly love her now if only… (I. Murdoch).

Предикаты, описывающие манифестируемые

проявления определенной эмоции, как правило,

обозначают действия, вызванные эмоциональным

отношением. Так, если «любить» и «обожать» обо-

значают эмоциональное отношение, то глаголы

типа «очаровывать», «лелеять», «путаться», «дон-

жуанствовать» описывают эмоциональное поведе-

ние. Анализ предикатов, описывающих концепт

«любовь», показывает, что как выразители эмоций

глаголы «любить/to love» можно отнести к неточ-

ным и неясным. Толковые словари обоих языков

указывают, что данные единицы имеют основное и

ряд не основных значений. Так, «любить» – это

двухместный предикат, т. е. речевая реализация его

значения зависит от синтаксической формы и се-

мантического разряда единиц, заполняющих места

объекта и субъекта.

Чувства любви могут испытывать существа с

высокоорганизованной психикой, если же место

субъекта глагола «любить» занимают названия рас-

тений, животных, различных предметов, то «лю-

бить» будет означать «нуждаться в каких-нибудь

условиях»: Цветы любят свет. В английском

языке в этом значении требуется другой предикат:

need, require.

Двусмысленность единиц «любить» и «to love»

состоит в том, что обычно они выражают положи-

тельную эмоцию (как принято считать); однако, их

значение может измениться через изменение описа-

ния эмоционального состояния или через ситуа-

цию, в которой проявляются противоположные (т.

е. отрицательные) эмоции или чувства такие, как

отчаяние, гнев, раздражение, ненависть.

При сопоставлении словарных статей предика-

тов любви в английском языке была выделена до-

минанта синонимического ряда – глагол «to love».

«To love» в то же время является гиперонимом си-

нонимического ряда, так как денотативные семы в

нем носят самый абстрактный характер, остальные

глаголы, в семантическом составе которых значе-

ние гиперонима подвергается некоторой модифи-

кации, являются гипонимами (to like, to adore, to

worship, to dote on, etc.). Сравним значения ряда

предикатов:

to dote on – to love blindly;

to adore – to love deeply and respect devotedly;

to idolize – to love or to admire to excess;

to worship – to love someone and show this by

your attractions;

to cherish – to love someone very much.

Ряд предикатов любви может управлять че-

тырьмя формами синтаксического дополнения: ну-

левой (т.е. употребляться абсолютно), инфинитив-

ной, придаточного предложения, именной.

При нулевой форме дополнения с местоиме-

нием на месте субъекта мы сталкиваемся с выраже-

нием любви в чистом виде, «любви к существу дру-

гого пола»: «Поразительное свойство человека ХХ

века. Сейчас любил, весь звенел от страсти. Потом

разлюбил, развернулся и ушел» (В. Токарева); «Он

один из тех людей, … которые, если уж влюбля-

ются, то не просто любят, а боготворят» (В. Н.

Набоков).

Наибольшее число значений предикатов

любви передается в употреблении с именным до-

полнением со значением объекта чувства: «Don’t

you care for me any more? – Of course, darling. I dote

on you» (W. S. Maugham); «I will love you and cherish

you and do my most devoted best to make you happy at

last» (I. Murdoch); «Так знайте же, что я люблю вас,

глупо, безумно» (И. С. Тургенев).

Предикаты «любить» и «to love» в таком упо-

треблении свободно сочетаются с наречными уси-

лителями типа «безумно/страстно/сердечно» и т. д.,

в английском языке – «deeply/awfully/absolutely/re-

ally/» etc.: «I took trouble with Lizzie because, in a way

I loved her. I say «in a way» not only because I have

only really loved once. She loved me far more in-

tensely» (I. Murdoch).

Очевидно, что добавочные средства авториза-

ции не могут быть употреблены с большинством

гипонимов синонимического ряда глаголов «лю-

бить/to love». В языковом сознании с трудом согла-

суются сочетания «to adore very much/absolutely/aw-

fully» или «to worship really/enough/in a way». Оче-

видно, это вытекает из самих значений глаголов, в

которых уже заложена определенная семантиче-

ская окраска. Появление обстоятельств подобного

рода «зависит от того, в выражении каких своих

признаков нуждается глагол для полноты своего

выступления в предложении» [4, C.25].

В английском языке высока частотность упо-

требления интенсификаторов с синонимической

конструкцией to be madly/deeply/awfully/wholly in

love: «And Jon could not help knowing, too, that she

was still deeply in love with him» (J. Galsworthy);

«Soames and my father were firsts cousins. And their

children were awfully in love» (J. Galsworthy).

Ю. Д. Апресян отмечает, что «в разговорной

речи в сочетании с наречиями just/simply предикат

to love утрачивает способность обозначать глубо-

кое чувство: «All those darling old spirituals – oh, I

just love them!» (D. Parker) – «Эти милые старые

негритянские духовные песенки. О, я просто без

ума от них!» [5, C.267].

Предикаты «to love/любить», «to

like/нравиться», «to care for/заботиться» могут

управлять инфинитивом, при этом, например, гла-

гол to love утрачивает значение «сильного, глубо-

кого чувства» и передает смысл «нравиться; полу-

чать удовольствие; испытывать склонность к чему-

либо»: «He loved to kneel down on the cold marble

Scientific Light No 22, 2018 17

pavement, and watch the priest» (O. Wilde); «Он лю-

бит ходить в бассейн, на ипподром, в Большой те-

атр на дневные представления» (В. Токарева).

Н. Д. Арутюнова отмечает, что «появляясь с

инфинитивом глаголов, обозначающих удовлетво-

рение физической потребности, предикат «любить»

указывает на отсутствие у субъекта чувства меры.

«Он любит поесть, поспать, выпить и пр.» [6, C.91].

В повелительном наклонении глагол «любить»

компенсирует отсутствие у глагола «нравиться»

форм императива: «Не люби спать, чтобы тебе не

обеднеть».

Предикаты «нравиться» и «to like», «любить»

и «to love» способны управлять придаточными до-

полнительными предложениями при помощи сою-

зов: Mother likes when it’s warm; «Я люблю, когда

шумят березы, / Когда листья падают с берез» (Н.

Рубцов). То же встречаем в отрицательной форме:

«Я не люблю, когда чужой читает мои письма, / За-

глядывая мне через плечо» (В. Высоцкий).

Синонимы «to love/to like/to fancy» могут

управлять герундием в значении объекта чувства,

передавая гедонистическое значение «нравиться»:

«Нe didn’t fancy nurses fussing about him, and the

dreary cleanliness of the hospital» (W. S. Maugham);

«Max found that he really loved teaching».

Группу гипонимов, характеризующих состоя-

ние влюбленности условно можно разделить на две

подгруппы с качественными оценками +/− (одобре-

ние/неодобрение). Такие предикаты как «болеть»,

«жалеть», «сохнуть», «сгорать», в русском языко-

вом сознании связаны с пониманием, сочувствием,

с точки зрения говорящего (т.е. имеют знак +): «Эле

стало его жалко. Она его любила. Правда, любовь

постепенно принимала крен ненависти, но все же

это была любовь» (В. Токарева). Предикаты «втю-

риться», «помешаться», «вешаться» имеют отрица-

тельную коннотацию: русским менталитетом осуж-

дается проявление во взаимоотношениях мужчины

и женщины назойливости, легкомыслия, нескром-

ности.

Анализ лексико-семантического анализа пре-

дикатов, отражающих концепт «любовь» в русском

и английском языках, показал, что:

1. Словарные значения предикатов любви в

русском и английском языках осуществляются при

помощи лексико-грамматического контекста на

уровне словосочетания, где реализуются основные

денотативные семы: «интимность» и «эмоциональ-

ность»; в английском языке при употреблении с ге-

рундием и инфинитивом наблюдается исчезнове-

ние семы «интимность», в этом случае предикаты

передают гедонистическое значение «нравиться».

2. В ряде основных лексико-семантических

вариантов предиката «любить/to love», вербализу-

ющего чувство любви, присутствуют прежде всего

переживание центральности объекта любви; а

также романтическая любовь, родственная любовь

к другу, любовь к ближнему, любовь к Богу, из ко-

торых на первом месте в большинстве словарей

стоит любовь романтическая.

3. Предикаты любви можно рассматривать

как динамичные, имеющие значение вневременно-

сти. Семантический анализ предикатов любви за-

трудняется из-за одновременного присутствия в

них двух структурно-семантических аспектов – ас-

пекта субъекта и аспекта объекта.

Список литературы 1. Воркачев С. Г. «Семантические прими-

тивы» в естественном языке: «желание»–«безраз-

личие» и сопряженные с ними смыслы. Моногра-

фия. – Краснодар, 1992. – 190 с. Деп. в ИНИОН

РАН № 47042.

2. Шмелев А. Д. Русский язык и внеязыковая

действительность. – М.: Языки славянской куль-

туры, 2002. – 496 с.

3. Васильев Л. М. Семантика русского гла-

гола (учебное пособие для слушателей). – М.: Выс-

шая школа, 1981. – 184 с.

4. Денисенко Л. Г. Лексические значения гла-

гола и его сочетаемость с модификаторами // Про-

блемы лексической и словообразовательной семан-

тики в современном английском языке: Сб. науч.

трудов. – ПГПИИЯ, 1986. – С. 25–30.

5. Апресян Ю. Д. Лексическая семантика. Си-

нонимические средства языка // Апресян Ю. Д. Из-

бранные труды. Т.1. Школа «Языки рус. культуры»

– М., 1995. – 472 с.

6. Арутюнова Н. Д. Типы языковых значений:

Оценка. Событие. Факт. – М.: Наука, 1988. – 341с.

18 Scientific Light No 22, 2018

THE SEMANTIC ANALYSIS OF QUANTIFIERS IN UZBEK LANGUAGE

Shamansurov Sh.

Zhejiang University

Abstract: Many researchers have been done on quantifiers between Chinese and other languages from the aspects of

meaning and grammar, but so far, there are only few studies between Chinese and Uzbek language. The function

of Quantifiers in Chinese and Uzbek language is to express the number of units at things or actions. The quantifiers

in Uzbek language can be classified into four forms: "Numeral + quantifier + noun", "Numeral + quantifier + noun

+ plural", "Numeral + noun", "Numeral + quantifier + verb (plural)". In this report, we will discuss about the

positions of quantifiers and ascertain whether quantifiers can be shared with plural markers or not in Uzbek lan-

guage.

Keywords: language, generally classified, quantifiers, qualitative functions

In Uzbek language, quantifiers are classified into

two forms: Mesnural quantifiers and Sortal quantifiers.

For example:

(1)a.Uncountable nouns

uch piyola sut.(uzbek)

San bei niunai (chinese)

“san bei shui(three glasses of milk)”

b.Countable nouns

bir juft kiyim(uzbek)

yi shuang yifu(chinese)

“yi shuang yifu(1(CL)Dress )”

In (1a), "SUT" is an uncountable noun, and it can

not be used directly with numerals. It needs to add

mesnural quantifier in the middle. In (1b), "kiyim" is

countable noun, and using quantifier is optional. Add-

ing or without quantifiers has no effect on the whole

meaning.