Scholarships to Recruit the Best and Brightest Into ...

Transcript of Scholarships to Recruit the Best and Brightest Into ...

Sage Publications, Inc. and American Educational Research Association are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Educational Researcher.

http://www.jstor.org

Scholarships to Recruit the "Best and Brightest" Into Teaching: Who Is Recruited, Where Do They Teach, How Effective Are They, and How Long Do They Stay? Author(s): Gary T. Henry, Kevin C. Bastian and Adrienne A. Smith Source: Educational Researcher, Vol. 41, No. 3 (APRIL 2012), pp. 83-92Published by: American Educational Research AssociationStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/41477768Accessed: 12-01-2016 17:30 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected].

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Feature Articles i ц

Scholarships to Recruit the "Best and Brightest"

Into Teaching: Who Is Recruited, Where Do

They Teach, How Effective Are They, and

How Long Do They Stay?

GaryT. Henry1, Kevin C. Bastian1, and Adrienne A. Smith2

Is a popular innovation for increasing human capital in the teaching profession - competitive college scholarships for teachers -

effective? The authors show that one large and long-standing merit- based scholarship program (a) attracts teacher candidates who have

high academic qualifications; (b) yields graduates who teach lower

performing students, although not as challenging as the students of other beginning teachers; (c) produces teachers who raise high school and third- through eighth-grade mathematics test scores more than other traditionally prepared teachers do; and (d) produces teachers who stay in public school classrooms for 5 years or more at

higher rates than alternative entry or other traditionally prepared teachers.

Keywords: economics of education; educational policy; evaluation; longitudinal studies; teacher education/development

The innovations. to improve

past 20 teacher years

More

could quality

employment

be through cast as

teacher a

opportunities

grand labor experiment

market for

to improve teacher quality through teacher labor market innovations. More employment opportunities for

women along with a glut of teacher retirements and rising demand from reduced class sizes and increased student populations have led policy makers to open many new pathways into teaching and intervene in the labor market in other ways to increase the supply and quality of the educator workforce (Bacolod, 2007; Corcoran, 2009; Hirsch, Koppich, & Knapp, 201 1). For instance, a recent National Research Council (2010) report documented 130 dis- tinct paths or portals through which individuals have entered the profession. Across these innovations, a consensus exists that increasing the human capital of the educator workforce would benefit students and the teaching profession; however, we have little evidence about whether many of the individual teacher labor market interventions have succeeded or failed.

Currently, much attention has been focused on a few highly visible and unique innovations. One such example is Teach For America (TFA), a selective program that rapidly prepares graduates from top universities for teaching in high-poverty

Educational Researcher, Vol. 4 1 , No. 3, pp. 83-92 DOI: 1 0.3 1 02/00 1 3 1 89X 1 2437202 © 20 1 2 AERA, http://er.aera.net

classrooms. Research indicates that TFA corps members are effective; however, most exit the profession after just 2 or 3 years of teaching (Boyd, Grossman, Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2006; Decker, Mayer, & Glazerman, 2006; Heilig & Jez, 2010; Henry et al., 2011; Raymond, Fletcher, & Luque, 2001; Xu, Hannaway, & Taylor, 2011). Other innovative approaches designed to increase the human capital of the educator work- force, such as college scholarships for selectively chosen appli- cants to earn traditional teacher preparation degrees and teach in public schools, have not been rigorously evaluated. In this article, then, we report on one such program, the North Carolina Teaching Fellows, which annually recruits and provides scholar- ships to 500 students who enroll in traditional teacher prepara- tion programs at in-state public and private universities. Similar programs exist in other states, but in contrast to TFA, where a body of research is building, little evidence exists about the effec- tiveness of these competitive college scholarships beyond anec- dotes and individual testimonies (Winerip, 201 1).

Therefore, in this article we report findings from a compre- hensive, systematic evaluation of the merit-based, competitive teacher scholarships provided through the North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program. We address four key questions:

1 . What are the academic qualifications of those who receive the competitive scholarships?

2. What are the characteristics of the classrooms and schools in which the scholarship recipients teach?

3. How effective are the scholarship recipients as classroom teachers?

4. How long do the scholarship recipients remain teaching in public schools?

We believe that the answers to these questions provide com- prehensive evidence about the effects of competitive college scholarships for prospective teachers and identify some refine- ments that could make programs more effective. Before reporting our answers to these questions, we provide some background on

•University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Department of Public Policy and Carolina Institute for Public Policy, Chapel Hill, NC 2Horizon Research, Chapel Hill, NC

APRIL 2012 |[5i~

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

teacher scholarship programs, including the program on which we focus, the North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program, in the next section. In subsequent sections, we describe the data and sample and then the method, or analytical plan, used to answer our research questions. Finally, we sequentially address each research question listed above before concluding with policy implications and areas for making improvements in competitive scholarship programs.

Background To attract individuals into the teaching profession, a number of states have initiated college scholarship or loan forgiveness programs for prospective teachers. According to Hirsch and colleagues (2011), 27 states offer such programs, with 11 states having established merit-based programs that specifically target funds and recruitment efforts at academically high- performing candidates. Examples of these programs include Florida's Teacher Scholarship and Forgivable Loan Program, Illinois's Golden Apple Scholar Program, Massachusetts's Tomorrows Teachers Scholarship Program, and South Carolina's Teaching Fellows Program. Understandably, the characteristics of such programs differ by state; however, there are a number of common elements. Each program (a) recruits rising college fresh- man or those already enrolled in college; (b) sets academic require- ments based on grade point average (GPA) or SAT/ACT scores; (c) leads to scholarship recipients earning an education degree and/ or license to teach; and (d) requires that awardees pay back the scholarship through teaching service in state (often 1 year of teaching for each year that the scholarship was received), some- times in specific school settings such as rural schools or schools with high populations of economically disadvantaged students.

As a leader in these teacher scholarship efforts, in 1986 North Carolina initiated the Teaching Fellows Program to provide scholarships for teacher candidates to attend in-state public or private universities. The mission of the Teaching Fellows Program is "to recruit talented high school graduates into the teaching profession and to help them develop leadership qualities, such as visionary thinking and risk taking" (Public School Forum of North Carolina, n.d.). The North Carolina General Assembly annually funds a new cohort of 500 Teaching Fellows and pro- vides them with scholarships of $6,500 per year for 4 years to attend a North Carolina university and earn their teaching cre- dentials. The scholarships require 4 years of teaching in North Carolina public schools (NCPS); if the 4-year teaching commit- ment is not fulfilled, the scholarship recipient is required to repay the loan with 1 0% interest. High school seniors are selected into the Teaching Fellows Program based on a multistep process, which includes a detailed application, short essays, nominations by their high school guidance counselors, and a series of local and regional interviews. As part of this application process, the Teaching Fellows selection committee focuses on applicants' aca- demic performance (a minimum SAT score of 950 and high school GPA of 2.5) and diversity (approximately 20% of scholar- ship recipients are minorities; 30% are men). In total, approxi- mately 20% of applicants are accepted into the Teaching Fellows Program (Public School Forum of North Carolina, n.d.).

After acceptance into the Teaching Fellows Program, recipients rank order the North Carolina universities they wish to attend (12

~84ll EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER"

public and 5 private universities participate) and are granted a scholarship for a specific institution based on availability and acceptance by the university. Once on campus, the Teaching Fellows receive the same teacher education curriculum that other teacher candidates receive, as well as unique preparation experi- ences exclusive to the Teaching Fellows Program. These opportu- nities begin in the Teaching Fellows' freshman year, with tutoring and field experiences in public schools; cultural events, summer retreats, and service opportunities; and regular seminars to discuss pedagogy and reflect on their development. Overall, these addi- tional preparation experiences are designed to encourage the development of leaders, provide a greater understanding of educa- tion's place in society, and instill a sense of mission, service, and professionalism (Public School Forum of North Carolina, n.d.).

Prior to this study, the North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program had not been thoroughly evaluated. However, past research suggests several reasons why scholarship recipients such as Teaching Fellows may be more effective than teachers with other forms of preparation. First, the program selects individuals with high levels of academic achievement, which positively cor- relates with student achievement gains (Clotfelter, Ladd, & Vigdor, 2007, 2010; Greenwald, Hedges, & Laine, 1996). Second, the Teaching Fellows Program offers extensive fieldwork opportunities, such as classroom observations, one-on-one tutor- ing, and delivery of instruction, which, as recent research sug- gests, leads to more effective early career teaching (Boyd, Grossman, Lankford, Loeb, &c Wyckoff, 2009). Finally, the Teaching Fellows Program introduces preservice teachers to many multicultural and diversity experiences. This element makes the Teaching Fellows Program distinctive in comparison with traditional preparation programs (Fuller, 1992), and because many teachers entering the workforce lack cross-cultural knowl- edge, yet teach in multicultural classrooms, these experiences may enhance their effectiveness.

At a time when providing students greater access to highly effective teachers is increasingly important, our study makes a unique contribution to the understanding of teacher labor mar- kets and teacher quality by evaluating whether competitive schol- arship programs for prospective teachers are an effective mechanism to improve the human capital, effectiveness, and retention of the teacher workforce. The following sections detail our data and sample, methods for identifying effects, and results for each research question.

Data and Sample

Overall, the data set for this study includes all NCPS teachers in the 2005-2006 through 2009-2010 school years with less than 5 years of teaching experience. We limited our sample in this way because prior research indicates that teachers are most likely to exhibit measurable and relevant preparation influences early in their careers (Boyd et al., 2006). As detailed below, however, based on data availability and the research objective, we employ a unique sample of teachers and/or variables of interest to address each study question.

Academic credentials. For Question 1 , we examined variables rep- resenting the academic credentials of scholarship recipients - SAT scores, high school GPA, and high school percentile class

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Table 1 Covaríates Used in Teacher Effectiveness Analyses

Student Covariates Classroom and Teacher Covaríates School Covariates 1 . Prior test scores (reading and math) 1 . Class size 1 . School size and school size squared 2. Classmates' prior test scores (peer 2. Heterogeneity of prior achievement 2. Suspension rate

ability measure) within the classroom 3. Violent acts per 1 ,000 students 3. Days absent 3. Advanced curriculum (middle and high 4. Total per-pupil expenditures 4. Structural mobility school) 5. District teacher supplements 5. Other between-year mobility 4. Remedial curriculum (middle and high 6. Racial/ethnic composition 6. Within-year mobility school) 7. Concentration of poverty 7. Race/ethnicity 5. Single-year teacher experience indicators 8. Gender 6. Teaching out of field 9. Poverty 7. Teacher portals or preparation categories

10. Giftedness 1 1 . Disability 12. Currently limited English proficiency 13. Previously limited English proficiency 1 4. Overage for grade 1 5. Underage for grade 1 6. Indicators for high school courses

rank - prior to their enrollment in a teacher education program. Administrative data sets with precollege academic measures are not available for all teachers in North Carolina; however, the University of North Carolina General Administration records this information for all graduates of the public institutions of higher education in the state. The data set for this first research question, then, includes all NCPS teachers with less than 5 years of experience who graduated from an in-state public university.1

Classroom and school characteristics. For Question 2, we present descriptive statistics for the types of classrooms and schools in which scholarship recipients work. To examine these characteris- tics, we assessed two measures of student achievement, prior test scores averaged for the students in each teacher s classroom (stan- dardized with a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1) and each teachers schools performance composite (the number of tests passed at the school divided by the number of tests taken); two measures of student poverty, classroom and school free and reduced-price lunch percentages; and one measure of teacher pay, average teacher salary supplements. To assess whether the scholar- ship recipients were able to immediately translate their academic records or credentials into more or less challenging environments in the teacher labor market, we limited our sample to first-year, tested-subject teachers in elementary, middle, and high school.2 We compared the values for the scholarship recipients with those of teachers who entered teaching with different types of qualifica- tions and credentials, including other in-state prepared, out-of- state prepared, alternative entry, TFA, and Visiting International Faculty (VIF) teachers. Overall, this analysis assesses whether scholarship recipients serve more at-risk student populations or if they use their credentials and accomplishments to find posi- tions in schools and classrooms with larger proportions of higher achieving and lower poverty students or to receive higher pay.

Teacher effectiveness. To estimate teacher effectiveness, as measured by adjusted average student test score gains, the data set includes all tested-subject teachers in elementary, middle, and high school

with less than 5 years of experience. Here, the key data feature is our use of classroom rosters supplied by the North Carolina Department of Public Instruction (NCDPI), which allowed us to match teachers to approximately 93% of students in their classes, construct classroom-level covariates, and account for multiple teachers within a subject year for a student. For third- through eighth-grade students, prior and current test score performance is based on the North Carolina Grade 3 pretest and end-of-grade math and reading exams (standardized within year, grade, and subject), whereas in high school, students' prior performance is based on the eighth-grade math and reading end-of-grade exams, with all high school end-of-course exams serving as the dependent variable (standardized within year and subject). The focal vari- ables for this analysis are a set of teacher preparation indicators comparing in-state prepared teachers (reference group) to scholar- ship recipients, out-of-state prepared, alternative entry, TFA, and VIF teachers. To adjust for factors influencing teacher effective- ness outside the control of teachers in the different preparation categories, models also include a rich set of student, classroom, teacher, and school covariates, as listed in Table 1 .

Teacher retention. Finally, because these merit-based scholarships for prospective teachers often require the recipients to teach for a set period of time, assessing whether they return to the classroom after fulfilling the required service period provides an indication of their intention to persist as teachers. It would be desirable to investigate how long scholarship recipients stay, but due to data limitations, we were able to assess only whether the scholarship recipients stayed for a fifth year, 1 year longer than required to repay the college scholarship. To address Question 4, we follow three cohorts of first-year teachers (2004-2005, 2005-2006, and 2006-2007) for 5 years, which allows us to avoid right-censored data issues (which occur when the opportunity to observe teach- ers for their fifth year is not available for some of the sample), and use certified salary files supplied by the NCDPI to construct a dichotomous variable indicating whether a teacher remains in

APRIL 20 1 2 |[5Г"

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Table 2 Who Is Recruited ?

Elementary School Middle School High School Recruitment Scholarship Non-Teaching Scholarship Non-Teaching Scholarship Non-Teaching Variables Recipients Fellows Recipients Fellows Recipients Fellows SAT score 1,154* 987 1,161* 1,015 1,186* 1,073 High school GPA 4.09* 3.32 4.09* 3.32 4.13* 3.53 High school class 93.09* 71.45 92.70* 71.01 93.86* 76.36

rank (%) Teacher count 418 3,335 343 1^701 547 1,438 Note. This table presents descriptive academic information for Teaching Fellows (scholarship recipients) at in-state public universities (University of North Carolina) and traditionally prepared teachers (non-Teaching Fellows) at in-state public universities. Using a correction for false discovery rate, asterisks in the scholarship recipients' columns indicate that their values are significantly different at the p < .05 level from the non-Teaching Fellows' values.

NCPS for at least 5 years. We compare the persistence of the scholarship recipients with that of other teachers who have no specific requirement or incentive to persist as classroom teachers for 5 years or more, including in-state prepared, out-of-state pre- pared, alternative entry, TFA, and VIF teachers.

Analytical Plan

The analytical methods employed to address the study questions vary. The following sections describe our analytical approaches to address the questions.

Academic credentials and classroom and school characteristics. The goal for Questions 1 and 2 is to determine whether scholarship recipients have significantly different academic credentials or classroom and school characteristics than teachers with other forms of preparation. To empirically test this, we employ stan- dard independent sample t tests, which have been adjusted for the use of the same sample, to conduct multiple hypothesis tests using false discovery rate corrections beginning at a p value cutoff of .05; we use asterisks in Tables 2 and 3 to indicate statistically significantly differences. We conduct separate analyses for high school, middle school, and elementary teachers.

Teacher effectiveness. In assessing the effectiveness of competi- tive scholarships for prospective teachers, the question arises about the other teachers with whom the scholarship recipients should be compared. Since teachers who have prepared in the state hold common credentials, attended the same colleges and universities as the recipients of the teacher scholarships, and include the "traditionally prepared" teachers, we selected these teachers as the reference group. In addition, we included teach- ers with other types of credentials and qualifications, including out-of-state prepared, alternative entry, TFA, and VIF teachers in order to enable comparisons with other groups that have become teachers through teacher labor market innovations. For this analysis, our preferred estimation strategy is a multi- level model, specified at the student, classroom, and school level, which adjusts for the nested, dependent nature of stu- dent test score data and includes a rich set of covariates to identify the effect of the competitive scholarship program. The equation used to estimate teacher effectiveness is as follows:

"вб] ["educational researcher"

Yijst = ßo + + ß2 7" eaching Fellow + . . .

ß6 WF + yxXijs + Y Л + УМ + Ъ + 8; + еь

Where is the test score for student ¿ in classroom j, in school s, at time t ; Yit.n represents test scores for student i in a prior time period; ß2. . .ßö estimate the average effect of the teacher preparation categories, particularly Teaching Fellows, in relation to in-state prepared teachers; TeachingFellow. . . VIF are indicator variables that equal 1 if the teacher entered the teaching profession through that category and 0 if not; ^represents a set of student covariates; yx is the estimate of the average effect of student covariate x; ZjS represents a set of classroom covariates; yz is the estimate of the average effect of classroom covariate z; Ws represents a set of school covariates; yw is the estimate of the average effect of school covariate w; and |i;, 8y, and 05 are disturbance terms representing unex- plained variation at the individual, classroom, and school lev- els, respectively.

Although we use a rich set of student, classroom, and school covariates in our preferred specification, some may question how well the covariates control for unobservable or unmeasured fac- tors that may influence teacher effectiveness and confound esti- mates of effectiveness. These factors include the sorting of teachers and students into schools, the quality of school leader- ship and school working conditions, and the selectivity of specific in-state colleges and universities that prepare the scholarship recipients to teach (Kennedy, 2010; Lankford, Loeb, & WyckofF, 2002). Therefore, to account for these threats to estimate validity, we employ school fixed effects and university fixed effects as alter- nate identification and estimation strategies. The school fixed effects limit effectiveness comparisons to teachers within the same public schools, thereby controlling for unmeasured sorting or school factors that may influence estimates of effectiveness. In addition, the university fixed effects limit effectiveness com- parisons to other teachers who graduated from the same in- state (public or private) institutions and did not receive the

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Table 3 Where Do They Teach ?

Classroom Free School Free Prior Classroom School Performance or Reduced-Price or Reduced-Price Average Teacher

Teacher Category Average Test Score Composite (%) Lunch (%) Lunch (%) Supplement (dollars)

Elementary School, Tested Subjects Scholarship -0.175(0.482) 60.61(16.19) 46.85(30.62) 59.87(23.41) 3,298(1,682)

recipients In-state prepared -0.173(0.480) 59.51 (15.79) 46.00(32.11) 58.78(23.61) 3,033* (1,530) Out-of-state prepared -0.199(0.491) 58.39(16.12) 46.70(29.94) 57.83(24.86) 3,71 7* (1,566) Alternative entry -0.532* (0.696) 53.04* (1 6.21 ) 42.94* (33.24) 65.84* (24.81) 3,033(1,359) Teach For America -0.500* (0.308) 47.39* (10.96) 66.63* (23.93) 83.73* (16.11) 4,314* (1,782) Visiting International -0.355* (0.529) 55.16* (16.98) 51.23(32.79) 68.57* (25.33) 3,550(1,474)

Faculty Middle School, Tested Subjects

Scholarship -0.071(0.689) 64.48(14.79) 37.75(27.06) 46.79(19.14) 3,240(1,613) recipients

In-state prepared -0.245* (0.700) 60.87* (1 6.09) 43.93* (28.1 5) 53.1 7* (19.87) 3,115 (1,630) Out-of-state prepared -0.191* (0.719) 60.47* (1 6.49) 40.93* (27.86) 49.63(21.65) 3,593* (1,657) Alternative entry -0.456* (0.724) 50.79* (1 7.20) 49.75* (28.95) 61 .69* (20.88) 3,132(1,506) Teach For America -0.652* (0.561) 46.34* (13.47) 66.92* (23.83) 77.36* (14.86) 4,498* (1,785) Visiting International -0.379* (0.718) 48.89* (16.57) 46.63* (31 .62) 66.49* (22.93) 3,366(1,553)

Faculty

High School, All Tested Subjects

Scholarship -0.060(0.570) 70.76(12.89) 36.92 (23.66) 39.26(19.25) 3,231 (1,668) recipients

In-state prepared -0.100* (0.606) 70.12(13.72) 35.78(24.94) 38.62 (19.26) 3,289(1,691) Out-of-state prepared -0.1 1 8* (0.61 1 ) 67.99* (1 5.54) 38.1 9 (24.48) 40.70 (20.81 ) 3,475 (1 ,641 ) Alternative entry -0.269* (0.61 6) 62.22* (1 5.76) 41 .79* (27.1 1 ) 46.22* (21 .78) 2,998 (1 ,481 ) Teach For America -0.532* (0.51 7) 58.30* (1 9.1 9) 61 .89* (21 .43) 60.1 9* (28.27) 3,534 (2,1 63) Visiting International -0.497* (0.611) 59.06* (14.85) 46.86* (27.85) 52.51 * (24.68) 2,849 (1,628)

Faculty

Note . This table displays descriptive information for first-year tested-subject teachers only; means are shown with standard deviations in parentheses. Using a correction for false discovery rate, asterisks indicate that the scholarship recipients' values are significantly different at the p < .05 level from the values for the teachers in the other preparation categories.

scholarship. When comparing these fixed effects estimates to those from the multilevel model, we become more confident in the estimates if they are similar in direction, magnitude, and sta- tistical significance.

Teacher retention. The goal for Question 4 is to determine whether scholarship recipients are significantly more likely than other teachers to remain as public school teachers for at least 5 years. To test this for the three cohorts of beginning teachers in our sample that we can observe for 5 years, we employ logistic regression where remaining as a teacher in public schools for 5 years is the dependent variable, the recipients of competitive scholarships and the other groups of teachers are included as focal indicator variables, and each of these groups compared to in-state prepared teachers (reference group). Because odds ratios generated by logistic regression are not easily interpretable, we also estimated relative risk ratios, which express the probability of staying for 5 years relative to in-state prepared teachers. Finally, to

supplement this analysis, we include a figure for the same three cohorts of beginning teachers that depicts the percentages of teachers, by group, persisting as public school teachers for 3 and 5 years, respectively. What Are the Academic Qualifications of Those Who Receive the Competitive Scholarships?

With increasing the human capital of the educator workforce as a goal of competitive teacher scholarship programs, we first examine the extent to which teachers who were selected to receive the competitive scholarship had higher academic qualifications upon college entry than other teachers prepared at the same in- state public institutions. To address this question, we compare three measures - SAT scores, high school GPA, and high school percentile class rank - for 1,308 scholarship recipients and 6,474 other novice teachers. Here, Table 2 shows that, across grade lev- els, scholarship recipients had significantly higher SAT scores, high school GPAs, and high school percentile class ranks than

APRIL 201 2 IP#""

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

their peers graduating from the same University of North Carolina institutions. For example, high school teachers who received the competitive scholarship averaged SAT scores of 1 , 1 86, which was 113 points higher than those of traditionally prepared teachers from the same in-state public institutions. In elementary and middle schools, the SAT gap was even larger - 1 67 and 146 points, respectively. Overall, the scholarship recipients' academic qualifications clearly exceeded those of their peers pre- pared to teach at the same institutions because, on average, the scholarship recipients posted SAT scores above 1,150 and high school GPAs greater than 4.0 and ranked in the top 10% of their high school graduating classes. However, in comparison to all other novice teachers from 2005-2006 through 2009-2010, the incentive of the scholarship was not sufficient to attract larger percentages of minorities or men into the teaching profession. In total, 16.17% and 18.45% of the scholarship recipients who entered public school classrooms were classified as minority or male, compared with 20.59% and 21.11% for all other teachers in the sample, respectively.

This analysis shows that the offer of competitive, merit-based scholarships was sufficient to recruit rising college freshman with top academic qualifications into the teaching profession. Although some research indicates that individuals with better academic credentials are more effective teachers (Clotfelter et al., 2007, 2010; Greenwald et al., 1996) and that they tend to leave teaching at higher rates (Borman & Dowling, 2008), we will directly test the effectiveness and persistence of these scholarship recipients in later sections. But first we present our analysis of the types of classrooms and schools in which these scholarship recip- ients work and compare these environments to those of teachers who enter the profession with different qualifications. What Are the Characteristics of the Classrooms and Schools in Which the Scholarship Recipients Teach?

To better understand how those individuals who received one of the competitive scholarships interacted with opportunities in the teacher labor market, we compare the distribution of scholarship recipients into different types of classrooms and schools with that of first-year teachers with different qualifications and credentials. The types of classrooms that the scholarship recipients teach in reflect both their preferences and the opportunities that are avail- able for them to choose, specifically, whether they end up in envi- ronments with lower performing or higher performing students or with more or fewer students living in poverty than other teach- ers do. Table 3 displays the group averages and tests of signifi- cance comparing the scholarship recipients with teachers in each of the other preparation categories. In 12 out of 15 comparisons, results show that scholarship recipients teach in schools with sig- nificantly higher percentages of students passing state tests com- pared to teachers in other preparation categories. Furthermore, in 10 out of 15 comparisons, scholarship recipients are found in schools with a significantly smaller percentage of the student body qualifying for free or reduced-price lunch.

Besides sorting at the school level, it is possible that the teacher scholarship recipients are assigned different types of students at the classroom level. To pinpoint the mean classroom achievement level, we averaged individual student standardized test scores from the prior year across all students in a classroom. Examining

ев] I EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER"

the results in Table 3, all teacher groups have a negative class aver- age, which is in line with other research that shows that inexperi- enced teachers are often assigned to students with poorer prior academic performance (Clotfelter, Ladd, & Vigdor, 2005; Lankford, Loeb, & Wyckoff, 2002). Similar to results at the school level, however, Table 3 shows that in 13 out of 15 com- parisons competitive scholarship recipients teach in classrooms with students who had performed significantly higher on their prior year's exams; in 9 out of 1 5 comparisons scholarship recip- ients teach in classrooms with significantly fewer students who are eligible for free or reduced-price lunches.

Finally, another possible indicator of the advantage of the competitive scholarship recipients in the labor market could be monetary. School districts in North Carolina are allowed to offer supplements to the salaries set by the state to attract and retain teachers. To investigate whether scholarship recipients teach in districts offering higher teacher salary supplements, we compare the average teacher supplement for first-year teachers who received the competitive scholarship with the average supple- ments in districts where the other first-year teachers were employed. Shown in the last column of Table 3, it is clear that scholarship recipients are not receiving significantly greater salary supplements than other first-year teachers. In fact, in 4 out of 1 5 comparisons scholarship recipients receive significantly less. Overall, the evidence in Table 3 suggests that Teaching Fellows decide to teach in more advantaged schools and classrooms but not in districts offering higher salaries.3

How Effective Are the Scholarship Recipients as Classroom Teachers?

To determine whether recruitment and college scholarships for prospective teachers can improve student achievement, we com- pared the effectiveness of the competitive scholarship recipients, as measured by adjusted average student test score gains, relative to other teachers who were prepared to teach at the same institu- tions of higher education (in-state prepared teachers).4 Table 4 shows that regardless of model specification (multilevel model or limiting comparisons to teachers within schools or universities), students taught by scholarship recipients posted significantly larger test score gains in elementary and middle school math and in all 10 high school courses that have end-of-course exams (Algebra 1, Algebra 2, geometry, biology, physical science, chem- istry, physics, economics and civics, and U.S. history) than stu- dents taught by scholarship recipients' in-state prepared peers. To make these standard deviation estimates easier to interpret, we converted the elementary and middle school math coefficients in Table 4 into equivalent days of student instruction, assuming that learning occurs equally throughout the school year. Here, in comparison to in-state prepared teachers, scholarship recipients add the equivalent of approximately 9 and 14 days of student learning to a 1 80-day school calendar for elementary and middle school math, respectively (see Henry, Thompson, Former, Bastian, & Marcus, 20 1 1 , for a description of the conversion process). These differences are also found when comparing schol- arship recipients with other novice teachers within the same schools and those who graduated from the same university, indi- cating that the students of scholarship recipients post higher test score gains than the students of their coworkers and those who

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ч* О £

I </) S сл .§

.2

1 о Чм

¡ $ íS € § £ *С £ ü 4> 7 -Р .QJ Ü h* rç Ч* ̂ ^ 0 ^ ^

t а "8 « с с 3 ■§ g. (2 а 4 vi а.

fe Ä

S «ç сл Д. šs сл

tí «e сл .5 <3 £ 8 С/> сл £ ч«*

1 I 0

i С íü

1

^ "о я * - 5< сл О 00 £ S "J £! 2 £ о и 9; и- О О <т> Lo , и ', •¡od

и- vo Lo гч lü ,

_ ^ 13 O "D 2 7 inNOKvD^difNl-K с с ■S 2 CN O CN О ▼- О 't M О (N _ л с VJ £ * Ош LL ООООООг-От-О • • • ••••...

▼- M (N CSI g _

г-- 40 л CN £¡ г- <Ъ ГО £ О !Г 13 s VJ * LL • • • ••••... CSI г-- CN г- ГО О s Xü

* LL OOOOOOOOOO • - • •

- ••••... К г-- Гх ГЧ CN <У) г- г- ГО ¡=- О Ž s

M <Л - I - I ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ~ ■£

. 1 ^

. LOÎS(NK(TiKO^r-î-CO 11 «^CNOCNOOOVOCSIKCN О LO 00 О О К. У ¿ qq qqqor-qoo гм lo cn го r- ro _i 5 òò òoòòòòòò ^ ^ ^ ^ 5

0 t/i ~ ^ £ *35 cn ̂ о -5 JÏÏ o§ g 2 i •i od - » s.

g> Э 1 .E S5 Ш £ á Õ X CN ÏÏooSon^^ O O O O O CN *~" CN *> rr' ^ fN гч 00 - QJ X CN O O O O O CN *~" CN о rr' гч i in г- lo V Oqqqqoooooo

X CN O O O O O CN *~" CN S о

rr' S 3 гч i

in ^ г- lo ^

Ï5 и oooooooooo ^ ' ^ ^ ^ ~ ' g -g «ü c-r» i ^ ' i ^ ^ ^ ~ - ' £ с •J ев аз •J S * ^ ^ ^ ^ E ^ >ç fO^NttN^r-CNKCN *J3 ■£ •«CNOOOOOCN^-r-T- ,<ft ш v£> К 00 чО <- СГ> ¿OOOOOOOOOO ш О 00 г- 00 г- m > ^ ОО ОООООООО сл ^ R ^ Ч. ^ ^ С ^ ^ 2¿ г- ^ >

i > - <У> jj* ^ > <У> *35 ^ т - 'fi v *ГшГч'г~ щ ^ t 03 £ E О О щ «Л •- о О ш *- Ьч С 5

О •£ О -Si

JC •£ О .у tí ш W) S= tí fg ш £ * ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ с g S _ cor-^KOKcofnKvû •,= R -, _ 15 ГО г- OOr-OttNr-r- 3<- O hv Ln CO co X Jž -, o oooooor-ooo ja co m lo t- гч >; 3 -с ОО ОООООООО 'E ^ ^ О •- ьл С 0J 5 ,9 аз U и

^ vûP^Kt-000?KVÛ «2 g < CN^OOr-OI-CNCNr- Ст~ ^ ^ <т> ^ с ¿OOOOOOr-OOO □ со о Т- 00 CN ф 5 ОО ОООООООО О ^ ^ jü а;

s ^ Я - "fi "£ *(Л hs 1' s си îr, LU о О 2 ГО ГЧ i= îr, SE LU ОО ÄLOrx W5 •= о о а> ^ ^ 0 4 5- i-

а> J

Hb KnOON^KCNÍN - ' D "ÕOOOOOOCNr-Tfr- LO (T, rf r- Tt о -О С 0 OOOOOOOOOO V£> CN <0 v£) ro l' 2

5 ^OOOOOOOOOO rtLO^ro^CN DO r- T- T: 0) C/5 1 r- T- с

E я QJ ^ lOKCOrOlOK^OCOCN ^ ^ ^OOOOOOCNr-fOT- LO rf ^ LO 00 r-

¿oooooooooo ^ ^ ^ ГО ^ О ro 041 ^ 5 oó ̂ ОООООООО ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 041 Db ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ro q3 "O >. с я * - 3 «л ^ <T> Ä ^ ìr ш ro О CN 0^ Ä ^ ^ S ш U- О о 3; v •1

U- od ^ « -5

f Э ^ S 4? ... "о

^ Ol r-'tr-OiO^rOOO^ 03 h "ö roo r-OOOhvCNLOx- ^ ч£> 0^> ro ^ Q. <2 0 OOOOOOOOOO LO Гх T- ro О cu С -с ОО ОООООООО ^^rro^CN О. Oí W I 1 1 I ^ - ' T- T- <y Oí E on W I 1 I 1 - T- T-

g <y

QJ on 1 1 I * , - - * , - v с ^ oo^otroairor-coLo _ ^ ^гоОт-OOOrxcN^r- VD ^ О _ LO T- 1/Г - 1 ОО ОООООООО LO О О О О го с 5 ОО ОООООООО ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ 9, ^ ' ' ^ ro -Z ПЗ CL ^ 15 о

г*» í/) QJ О о (Л i QJ о ^

"1 "S S S

-1 о .у í S û. S

-1 о .У '■§ ̂ "2 > je !е- ̂ S. g s ^ § "5 jõ ;Q-Ä "S ̂ S. g fe g* § "5 £ ¿ g

£ s !$^Ë.s!jjj!:siië ti X P 2Ï.a ^|v £ ti О < & > X £ О < P > 2Ï.a

APRIL 20 12 |fÌ9~

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

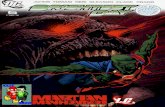

FIGURE 1 . How long do they stay ? This figure depicts the percentage of teachers who return for a third and fifth year of teaching in North Carolina public schools for three cohorts of first- year teachers , regardless of subject taught, 2004-2005 > 2005- 2006 ; and 2006-2007.

participated in the same teacher preparation curriculum. In con- trast, the students of scholarship recipients average lower test score gains than the students of other in-state prepared teachers in middle school reading by approximately 12 days of learning. This difference holds when comparing teachers within the same school but is smaller in magnitude and not statistically significant for those who graduated from the same teacher preparation pro- gram, which may indicate that the curriculum in the programs that prepare middle school reading teachers may warrant more investigation.

In comparison to teachers with other credentials, the students of scholarship recipients posted larger test score gains than stu- dents of out-of-state prepared and alternative entry teachers in elementary math, middle school math, and high school. Further, students of scholarship recipients posted larger gains than stu- dents of VIF teachers in high school. Only in comparisons with the students of TFA corps members in middle school and high school do the students taught by scholarship recipients exhibit lower gains. Generally, but with a few exceptions, it appears that the scholarship recipients are effective teachers.

How Long Do the Scholarship Recipients Remain Teaching in Public Schools?

To examine whether scholarship recipients are likely to persist in teaching for a longer period than required to fulfill the obliga- tions of the scholarship, we longitudinally tracked three cohorts of beginning teachers to see if the scholarship recipients persist into a fifth year of teaching. This analysis may signal a greater commitment to teaching on the part of those who received the merit-based scholarship. Examining Figure 1, it is clear that scholarship recipients are much more likely to remain teaching in public schools. More than 90% of scholarship recipients return for a third year of teaching, with 75% continuing into a fifth year. These percentages are higher than those for in-state prepared teachers (80% and 68%, respectively) and substantially higher than those for all other teacher groups. To empirically test the significance of these findings, we estimated odds ratios and

~90|l EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER

Table 5 How Long Do They Stayi

Odds Ratio Relative Risk Teacher Category and z Score Ratio and z Score

Scholarship 1 .447* (4.71 ) 1 .1 1 6* (5.1 9) recipients

Out-of-state 0.456* (-19.31) 0.713* (-18.24) prepared

Alternative entry 0.326* (-27.46) 0.588* (-25.29) Teach For America 0.048* (-1 5.22) 0.1 30* (-1 1 .28) Visiting 0.009* (-18.40) 0.027* (-14.52)

International Faculty

Note. Includes all first-year teachers in 2004-2005, 2005-2006, and 2006-2007. The dependent variable is whether teachers stay at least 5 years in North Carolina public schools. Odds ratios and relative risk ratios are in reference to in-state prepared teachers. *p < .05.

relative risk ratios from models with persisting for 5 years as the dependent variable in relation to in-state prepared teachers.5 Here, Table 5 shows that the teachers who received the competi- tive scholarship were 1 . 1 times more likely to remain teaching in public schools than their in-state prepared peers. Furthermore, because teachers in all the other preparation categories are sig- nificantly less likely to stay for 5 years than in-state prepared teachers, it is clear that the teachers who received the scholarship demonstrate the greatest commitment to continuing to teach in the states public schools.

Conclusion

In light of the research consensus regarding the importance of teachers in student achievement, states and school districts are seeking ways to improve teacher quality through interventions in teacher labor markets (Aaronson, Barrow, & Sander, 2007; Nye, Konstantopoulos, & Hedges, 2004). One promising reform, competitive college scholarships to earn teacher educa- tion degrees and teach in public schools, has been implemented by several states; however, little evidence existed concerning the impacts of this type of innovation prior to the study reported here. To summarize our study, we found that (a) the competitive scholarships attract individuals with significantly higher aca- demic credentials into the teaching profession; (b) recipients of the scholarships teach in schools and classrooms with more high-achieving and low-poverty students; (c) students of the scholarship recipients have significantly larger student test score gains in elementary school math, middle school math, and high school than do students of in-state prepared, out-of-state pre- pared, and alternative entry teachers, but the middle school stu- dents taught by teachers who received the scholarships perform more poorly in terms of reading test score gains than those of other teachers; and (d) teachers who received the merit-based scholarships remained teaching in public schools for 5 years or longer at significantly higher rates than other teachers.

Because the scholarship recipients were not randomly assigned to receive the scholarship from a group of eligible recipients, to consider the differences presented in the findings as causal, the

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

covariates (and/or fixed effects) in the models must be assumed to have been adequately adjusted for any confo unders, which can be defined as omitted variables that are related both to selection to receive the scholarship and the outcome variable. Therefore, interpreting these findings should be done with care. One spe- cific limitation of our findings, however, is that they do not dis- entangle the effects of selection to receive the scholarship from the unique program experiences that were provided to the schol- arship recipients. To begin to sort this out, we performed a pro- pensity score analysis comparing scholarship recipients to a matched, more selective group of teachers prepared at in-state public institutions who had similar high school academic creden- tials and were similar in terms of the information on eligibility for need-based financial aid submitted during the college application process. These results showed that the students of the teachers who received the scholarships posted test score gains no higher or lower than those of the students of teachers in this matched sam- ple. This appears to indicate that the differences attributed to being taught by the scholarship recipients were more likely driven by the increased human capital that the scholarship recipients brought with them into the teacher preparation program rather than by the provision of additional, unique programmatic experi- ences. Therefore, we believe that the scholarship, including its

eligibility requirements along with the interviews and essays that are used in the selection process, its size ($6,500 per year per student), and its visibility to high school counselors and rising high school seniors, is likely to be the key programmatic ingredi- ent in producing the positive findings.

In addition, we believe the findings warrant drawing three

specific conclusions about other aspects of merit-based scholar-

ship programs for teachers. First, results from this study provide compelling evidence that competitive college scholarships for

prospective teachers can recruit individuals with higher levels of human capital into teaching. However, the presence of other, similarly well-qualified teachers whom we identified as matches to the scholarship recipients raises a question about how many of the scholarship recipients might have been attracted into teach-

ing without the scholarship. Simply put, we do not know how

many of the teachers who received the competitive scholarship would have entered the teaching profession without the scholar-

ship as an incentive. Nonetheless, those who earn the award

appear to go on to become effective educators who stick with

teaching, underscoring the desirability of using competitive scholarships to attract those with higher human capital into

teaching. Moving forward, rigorous, quantitative evaluation research using random assignment or a regression discontinuity design would allow researchers to quantify the extent to which the scholarship increases the supply of teachers with high levels of human capital and would provide additional tests of the

hypothesis that merit-based aid for prospective teachers yields effective, persistent teachers.

Second, the evidence shows that those who receive the schol-

arship do not tend to teach lower performing or higher poverty students, who, other research shows, are less likely to have high- quality teachers. Some merit scholarship programs require recip- ients to teach in more challenging environments, and other innovative programs, such as TFA, assign teachers to only high- poverty, high-minority schools. However, mandating that the

scholarship recipients work in more challenging, hard-to-staff schools and classrooms might deter some of the potential appli- cants from pursuing the scholarship. This unintended conse- quence could undermine the factor that apparently drives its success - recruiting and placing trained teachers with high aca- demic qualifications. We believe that consideration should be given to providing incentives for this type of socially desirable behavior rather than mandating it. Since the scholarship recipi- ents already seem to react to financial incentives, offering higher salaries or a faster payoff rate for their scholarships (e.g., 1.33 years of credit for each year of teaching in a persistently low- achieving school) to teach in high-need environments could increase the number of scholarship recipients willing to teach in these environments, without the negative side effects. If sufficient numbers of scholarship recipients respond, this could signifi- cantly improve the access to more effective teachers for students most in need.

Finally, we argue that our findings should not fuel a competi- tion between labor market reforms, such as TFA, and competitive college scholarship programs, such as the North Carolina Teaching Fellows. On average, TFA corps members are more effective but tend to exit after 2 or 3 years, whereas scholarship recipients are both effective and substantially more committed to staying in the teaching profession. Therefore, our evidence sug- gests that states need more teachers from both TFA and com-

petitive college scholarship programs and as many other teachers with top academic qualifications as possible. Innovations to raise the human capital of the teacher workforce, including financial incentives such as merit-based scholarships for prospective teach- ers, should be developed, piloted, and rigorously evaluated and, when found effective, strongly supported to benefit student out- comes and the teaching profession.

NOTES

We would like to thank the Public School Forum of North Carolina; the 15 deans of education at the University of North Carolina system institutions; Alisa Chapman, Alan Mabe, and Erskine Bowles of the University of North Carolina General Administration; Charles L. Thompson of East Carolina University; and fellow researchers, includ- ing Brooke Maxfield and Nicole Hensel, at the Carolina Institute for Public Policy. We also wish to recognize the ongoing financial support for this research from the Teacher Quality Research initiative provided by the University of North Carolina General Administration.

Approximately 84% of the Teaching Fellows population graduated from an in-state public university. The remaining 16% graduated from an in-state private university and are not included in this analysis due to limitations on data availability.

2Descriptive statistics for all tested-subject teachers with fewer than 5 years of experience are available on request from the authors.

3Results for the teacher salary supplement are not surprising given other analyses that show that (a) North Carolina spends more money, per pupil, in high-need schools and (b) teacher salary supplements are greater in certain districts (Charlotte-Mecklenburg, Wake, and Durham counties) with larger proportions of out-of-state prepared teachers and Teach For America corps members (Bastian, Henry, & Thompson, 2011).

4Teacher effectiveness estimates, with Teaching Fellows as the refer- ence category, are available upon request from the authors.

5Teacher retention estimates, with Teaching Fellows as the reference category, are available upon request from the authors.

APRIL 20 1 2 |[?Г"

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

REFERENCES

Aaronson, D., Barrow, L., & Sander, W. (2007). Teachers and student achievement in the Chicago public high schools. Journal of Labor Economics, 25, 95-135.

Bacolod, M. (2007). Do alternative opportunities matter? The role of female labor markets in the decline of teacher quality. Review of Economics and Statistics, 89, 707-751 .

Bastian, К. С., Henry, G. T., & Thompson, С. L. (201 1). The distribu- tion of educational resources in Wayne County Public Schools (CIPP working paper). Chapel Hill: Carolina Institute for Public Policy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Borman, G., & Dowling, N. (2008). Teacher attrition and retention: A meta-analytic and narrative review of the research. Review of Educational Research , 78, 367-409.

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2006). How changes in entry requirements alter the teacher workforce and affect student achievement. Education Finance and Policy, 1, 176-216.

Boyd, D., Grossman, P., Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2009). Teacher preparation and student achievement. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31, 41 6-440 .

Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H., & Vigdor, J. (2005). Who teaches whom? Race and the distribution of novice teachers. Economics of Education Review, 24, 377-392.

Clotfelter, C., Ladd, H., & Vigdor, J. (2007). Teacher credentials and student achievement: Longitudinal analysis with student fixed effects. Economics of Education Review, 26, 673-682.

Clotfelter, С., Ladd, H., & Vigdor, J. (2010). Teacher credentials and student achievement in high school: A cross-subject analysis with stu- dent fixed effects .Journal of Human Resources, 45, 655-681.

Corcoran, S. (2009). Human capital policy and the quality of the teacher workforce. In D. Goldhaber & J. Hannaway (Eds.), Creating a new teaching profession (pp. 29-52). Washington, DC: Urban Institute Press.

Decker, P., Mayer, D., & Glazerman, S. (2006). Alternative routes to teaching: The impacts of Teach for America on student achievement and other outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 25, 75-96.

Fuller, M. (1992). Teacher education programs and increasing minority school populations: An educational mismatch? In C. A. Grant (Ed.), Research and multicultural education : From the margins to the main- stream (pp. 184-200). London: Falmer.

Greenwald, R., Hedges, L., & Laine, R. (1996). The effect of school resources on student achievement. Review of Educational Research, 66, 361-396.

Heilig, J. V., & Jez, S. J. (2010). Teach For America: A review of the evi- dence. East Lansing, MI: Great Lakes Center for Education Research and Practice.

Henry, G. T., Thompson, C. L., Bastian, К. С., Former, С. К., Kershaw, D. С., Purtell, К. M., et al. (201 1). Which qualifications matter? Effects of teacher entry portals on student achievement. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Henry, G. T., Thompson, C. L., Former, C. K. Bastian, К. С., & Marcus, J. V. (201 1). Technical report: UNC teacher preparation pro- gram effectiveness report (CIPP working paper). Chapel Hill: Carolina

92] I EDUCATIONAL RESEARCHER

Institute for Public Policy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Hirsch, E., Koppich, J., & Knapp, M. (201 1). Revisiting what states are doing to improve the quality of teaching: An update on patterns and trends (Working Paper W-01-1). Seattle: Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy, University of Washington.

Kennedy, M. (2010). Attribution error and the quest for teacher quality. Educational Researcher, 39, 591-598.

Lankford, H., Loeb, S., & Wyckoff, J. (2002). Teacher sorting and the plight of urban schools: A descriptive analysis. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 24, 37-62.

National Research Council. (2010). Preparing teachers: Building evidence for sound policy. Washington, DC: National Academies Press.

Nye, В., Konstantopoulos, S., & Hedges, L. (2004). How large are teacher effects? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 26, 237-257.

Public School Forum of North Carolina, (n.d.). Teaching Fellows Program. Retrieved from http://www.ncforum.org/

Raymond, M., Fletcher, S., & Luque, J. (2001). Teach For America: An evaluation of teacher differences and student outcomes in Houston, Texas. Stanford, CA: CREDO, Hoover Institution, Stanford University. Retrieved from http://credo.stanford.edu/downloads/tfa.pdf

Winerip, M. (201 1, October 3). A state grooms its best students to be good teachers. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes .com/ 2011/1 0/03/education/03winerip.html?_r= 1 &scp= 1 &sq= Teaching%20Fellows&st=cse

Xu, Z., Hannaway, J., & Taylor, C. (2011). Making a difference? The effects of Teach For America in high school. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 30, 447-469.

AUTHORS

GARY T. HENRY is the MacRae Professor of Public Policy in the Department of Public Policy and directs the Education Policy Initiative at Carolina in the Carolina Institute for Public Policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 120 Abernethy Hall, Campus Box 3435, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; [email protected]. His research interests include education policy, teacher effectiveness, educational evaluation, and causal inference.

KEVIN C. BASTIAN is a graduate research fellow in the Department of Public Policy and the Carolina Institute for Public Policy, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Abernethy Hall, Campus Box 3279, Chapel Hill, NC 27599; [email protected]. His research focuses on teacher effectiveness, teacher preparation, teacher labor markets, and educational evaluation.

ADRIENNE A. SMITH is a research associate at Horizon Research Inc., 326 Cloister Court, Chapel Hill, NC 27514; adrienne.ann.smith@ gmail.com. Her research focuses on educational policy, program evalua- tion, and research methods.

Manuscript received November 23,201 1 Revision received January 5, 20 1 2

Accepted January 6, 20 1 2

This content downloaded from 152.2.176.242 on Tue, 12 Jan 2016 17:30:14 UTCAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions