Sarah Boyd - Final Thesis (1)

-

Upload

sarah-boyd -

Category

Documents

-

view

26 -

download

0

Transcript of Sarah Boyd - Final Thesis (1)

Women Building Peace

Locating agency and empowerment in rights-based approaches to women’s community peacebuilding in Nepal

Sarah Boyd B.Com

Under the supervision of Dr Violeta Schubert

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts (Development Studies)

School of Social and Environmental Enquiry, Faculty of Arts

The University of Melbourne, November 2007

Figure 3: Women campaigning for their representation in Nepal’s peace process at a Mass Rally in Gorkha District headquarters, April 2007.

‘The opportunity created by conflict by merging women’s private and public

spheres, has not only raised women’s consciousness, self-esteem and

involvement in securing livelihoods, conflict resolution and peace building

processes, but has also opened up previously closed spaces and domains for

women. The challenge remains in capturing these opportunities, spaces,

experiences and knowledge at the local level and linking them to the broader

national level efforts for peacebuilding’ (Sharma and Neupane 2007: 23). Front page: Figure 1: Women for Peace (Shanti Malika) office headquarters in Kathmandu;

Figure 2: Women gathered at Mass Meeting on women’s representation in the peace process, Gorkha District headquarters, Nepal, April 2007.

Declaration

This thesis is a presentation of my original research work. Wherever contributions of

others are involved, every effort is made to indicate this clearly, with due reference to the

literature, and acknowledgement of collaborative research and discussions. The work

was completed under the guidance of Dr. Violeta Schubert, at the School of Social and

Environmental Enquiry, University of Melbourne.

Date:

i

Table of Contents Signed Declaration i Table of Contents ii List of Acronyms / List of Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Abstract v Introduction: “We want to see a ‘New Nepal’!” 1 Aims and objectives 6

Conceptual Framework: Responding to the call for a discourse 8 of women and peacebuilding The emergence of rights in the discourse of women and peacebuilding 9

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal 12

The People’s War and the peace process 12 Emergence of rights as a discourse of peacebuilding 13 Nepalese women: Navigating through conflict and closed spaces 15 International actors in Nepal 19

Chapter Two: Methodological approach 22 Selecting a case study in Nepal 22

Negotiating the field 23 Analytical and methodological scope of research 26

Chapter Three: Constructing a Nepalese discourse of peacebuilding 32 No peace if ‘Mother still weeps’: Defining peace and peacebuilding 32 External visions of a peaceful New Nepal 39 Chapter Four: Nepalese women: agents of their own empowerment 42 Narratives of empowerment: Recognising ‘power within’ 43 Women’s Peace Groups: Exercising ‘power with’ 45 From grassroots to the public sphere: Gaining ‘power to’ act as agents 46 Chapter Five: Negotiating mahnib adhikar and universal human rights 49 Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women, Peace and Security 50

Rights awareness: Turning on a light bulb! 53 Negotiating a Nepali language of human rights 56

Concluding Remarks: Agency to build peace 58 References 61 Appendices 71 Appendix 1: Literature Review: Gender and Peacebuilding: A Review of 72 Emerging literature in Development Appendix 2: UN Security Council Resolution 1325-Women, Peace and Security 104 Appendix 3: Map: Report of Bandhs/Blockades - 1 January - 30 September 2007 109 Appendix 4: Map: Topography (Study areas) 111 Appendix 5: Training Program on ‘Constituent Assembly, Human Rights, Good 113 Governance and News Reporting’, Gorkha District - Schedule.

Appendix 6: Training Program on ‘Gender Monitoring around Cantonment’, 115 Sindhuli District - Schedule.

ii

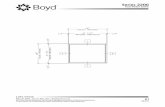

List of Acronyms ADB Asian Development Bank CA Constituent Assembly CBO Community Based Organisations CCO Canadian Cooperation Office CECI Canadian Centre for International Studies and Cooperation-Nepal CEDAW Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination Against Women CIDA Canadian International Development Agency CPA Comprehensive Peace Accord CPN-M Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) CPN-UML Communist Party of Nepal (United Marxist-Leninist) CPV Community Peace Volunteer DFID Department for International Development (UK) GTZ German Technical Cooperation HDI Human Development Index HMGN His Majesty's Government of Nepal IA International Alert ICG International Crisis Group IDP Internally Displaced Person IDRC International Development Research Centre IHRICON Institute of Human Rights Communication Nepal ILO International Labour Organisation INGO International Non-Governmental Organization INSEC Informal Sector Service Centre NGO Non-Governmental Organization NGOWG Non-Governmental Organization Working Group NHRC National Human Rights Commission OHCHR Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights PLA People’s Liberation Army (Maoist) RBA Rights Based Approach SPA Seven-Party Alliance UN United Nations USAID United States Agency for International Development UNDP United Nations Development Programme UNFPA United Nations Population Fund for Women UNMIN United Nations Mission In Nepal VDC Village Development Committee List of Figures Figure 1: Shanti Malika (Women for Peace) Office Figure 2: Women campaigning in Mass Rally, Gorkha District Headquarters Figure 3: Women gathered at Mass Meeting, Gorkha District Headquarters Figure 4: Highway Roadblock in Sindhuli District (Page 14) Figure 5: Visioning exercise for a New Nepal (Page 37) Figure 6: The Human Rights ‘Training Room’ (Gorkha District) (Page 49) Figure 7: Training session on CEDAW (Gorkha Training) (Page 50)

iii

Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Violeta Schubert - for so generously giving of her time, expertise, advice and wisdom. By imparting the mantra to ‘critically examine’, you have instilled so many valuable lessons. Indeed, many of these lessons are life-long and I will hear your voice in years to come urging me to think critically and to act with integrity. My sincere thanks are extended to Shobha Gautam for providing both insight and inspiration, who works tirelessly for women’s rights in Nepal. Without the support of IHRICON I could not have gained access, nor had the privilege, to meet the women of Kailali, Dang, Gorkha and Sindhuli. Further, to Meena Sharma and Anita Bista for their endless support, guidance and particularly translations, without which I would have missed so much. And to Kapil Kafle and Debika Timilsina for sharing your insights, time and knowledge, as well as John Macaulay and the rest of IHRICON in Kathmandu. My thanks are also extended to Ramesh Adhikari, for challenging my thinking on our every meeting. Dheri dheri dhunyabad, saathi haru. I owe particular gratitude to Jaya ji for her invaluable sharing of field-based knowledge, providing advice, facilitating key contacts and being an inspiration for this thesis. To Sunil dai, for your humour, advice, chats, translations and continuing insights into the Nepali psyche. The support, advice and guidance from mero Aama (my Mum) throughout my journeys to Nepal, and what has followed, has been precious. I am also grateful for the continual and abundant support from mero Didi (by big Sister) on the opposite side of the globe, whose determination in following dreams provides continual inspiration. Further, the support, friendship and constructive criticism provided by another sister, saathi Siv, has been invaluable. I cannot thank you enough for everything that has followed since Cussonia Court. And finally, to the Peace Volunteers from Gorkha, Sindhuli, Kailali and Dang, who shared so much, directly or indirectly, with me during my fieldwork. Your enthusiasm, determination and activism have given me inspiration. Thank you for providing me with an opportunity to listen to your stories, which I aim to bring to light in this thesis.

iv

Abstract The end of armed conflict and the project to create a ‘New Nepal’ has paved the way for new spaces in which women can be recognised as active agents in building peace. This thesis explores the nature of Nepalese women’s engagement in peacebuilding, the relationships between women’s participation and their empowerment, and the influence of international actors in this process. The narrative in this thesis is informed by four months of fieldwork in early 2007 with a Nepalese human rights organisation, the Institute of Human Rights Communication in Nepal (IHRICON). The key argument presented in this thesis is that prescriptive international approaches to peacebuilding overlook the local realities of gender roles and identities and the cultural context that inform women’s understandings of peace. This results in an unnecessary dichotomy between local and international meanings and approaches to women’s peacebuilding. This dichotomy is further accentuated by the assumption that raising women’s awareness of human rights constitutes their empowerment. This assumption neglects women’s own understandings of empowerment and their agency in that process. However, rather than passively adopting external meanings, Nepalese women strategically appropriate and reinterpret human rights language according to their own needs, values and aspirations. In short, Nepalese women construct meanings as part of an ongoing process of engagement in peacebuilding and human rights activities and it is through this process that empowerment can be located. It is difficult, therefore, to consider notions such as ‘peace’, ‘peacebuilding’, ‘human rights’ and ‘empowerment’ as anything but fluid and difficult to categorically define or situate entirely within the confines of template international programs that are transported into the local context. That is, there is an unexpected and positive outcome in this process of engagement which has enabled Nepalese women to assert their agency and negotiate an ‘opening of space’ for themselves in the New Nepal at both formal and informal levels of society.

v

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

1

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

One April afternoon during a human rights training program for women peacebuilders in

the remote headquarters of Gorkha District at the foothills of the Himalayas, our session

was interrupted by the chanting of a large crowd which could be heard drawing closer

and closer. The excitement amongst the women in the training program became clear as

we hastily abandoned our session and hurried outside to join the rally on the main street

below. There was a hive of activity and energy as hundreds of women marched along

chanting and shouting slogans such as “inclusion in the elections” and “women’s

representation in the New Nepal”. One man actively led the chanting, but most men

watched on from the sidelines and looked a little bemused as they peered out of their

shops and tea houses. One male shopkeeper even said to me, “this is new”. Because,

even though women had been involved in protests against the King’s absolute rule in

2006, gathering together as women on women’s issues, was indeed new. Even after

returning to our original location and continuing with the training program, excitement

over the day’s events continued to affect the mood of participants. Indeed, we concluded

our program by enthusiastically singing the chorus of “We want to see a New Nepal’- a

contemporary folk song emanating from teahouses around the country in the lead up to

the Constituent Assembly elections.

The above incident is only one of many which are indicative of a new form of activism

currently being constructed by Nepalese women. Since the cessation of armed conflict in

2006, women’s activism is being reoriented towards, and becoming incorporative of, new

elements and ideas relating to human rights and empowerment. Further, the growing

aspirations of women to not only voice their concerns about their ‘rights’, but also to

challenge and refashion their broader societal and familial roles and identities, has meant

that they have formed groups and associations comprised entirely of women. These

associations reveal an increasing vigour that reflects both continuities and discontinuities

with previous activism by Nepalese women. As Sharma and Neupane noted at a

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

2

Conference in Kathmandu earlier in 20071, the conflict has ‘opened spaces’ and domains

previously closed for women and an ‘opportunity’ for transformation through a merging

of the private and public spheres in Nepalese society. Yet as they emphasised in their

paper, despite this emergent activism, especially through women’s Peace Groups, the

grassroots community peacebuilding work of women remains largely invisible and often

overlooked in studies of peacebuilding. The knowledge and experiences of women

peacebuilders, as well as the so-called ‘opened spaces’, need to be better understood in

order to strengthen and support women’s roles in shaping a ‘New Nepal’ (c/f Sharma and

Neupane 2007). Feminist scholar Rita Manchanda also asserts that the involvement of

international development agencies in today’s conflicts (with particular reference to

South Asia) provides a further ‘opportunity for consolidating the empowering spaces that

may open up for women in the midst of loss’ (2005: 4744).

That is, the current social and political context of Nepal is not solely viewed in terms of

the processes, challenges and limits of post-conflict reconstruction, but also one in which

there is an enabling process for the empowerment of women. This may be facilitated

through women’s engagement not only with reconstructing their own society, but also

through developing an awareness of the broader international context within which

discourses relating to rights and peacebuilding abound. Indeed, the end of armed conflict

and the emergence of a ‘post-conflict peacebuilding agenda’ have seen a vast array of

international actors entering Nepal. Each of these external actors bring their own notions

of contributing, supporting or ‘educating’ the local people on how they can be

empowered to reshape their roles and assert their rights in a New Nepal. At a conceptual

level, a focus on women’s rights seems to assume a ‘neat fit’ between raising their

awareness of rights and empowerment. In the Nepalese context, this natural or easy ‘fit’

of rights and peacebuilding also seems intuitive given that the broader conflict and peace

process is centered on issues of rights. In this way, there is a notion that international

1 Jaya Sharma and Ramji Neupane. Women in Peace Building: A Community Approach to Peace Building in Nepal. Paper presented at the International Conference on Sustainable Development in Conflict Environments: Challenges and Opportunities, 16-18th January 2007. Kathmandu, Nepal. Conference organised by the Canadian Centre for International Studies and Cooperation (CECI).

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

3

support itself has an ‘opportunity’ to consolidate the ‘empowering spaces’ (c/f

Manchanda 2005: 4744) that the conflict may have opened up for women.

From another perspective, Denskus’ (2007) puts into question the ability of the

internationally driven peacebuilding agenda in Nepal to support the empowerment of

Nepalese people. In fact, Denskus (2007) warns that the ‘concept of peacebuilding’

provides a comforting notion for donors that peace can be built and measured without

challenging Western understandings of governance or social aspirations of people. This

inherent discord between the notions of ‘post-conflict peacebuilding’ and social

aspirations of local people is particularly evident when international approaches are

contrasted with the interests, needs and desires of local women in building peace. Whilst

there is no concise or ‘neat’ process for achieving peace, through the course of

conducting fieldwork for this thesis one thing became quite clear - the conceptualisations

of Nepalese women on how to build peace, and what peacebuilding constitutes, is

remarkably different from that of international actors. The approaches of Nepalese

women are grounded in meeting everyday needs of survival and addressing social

conflicts in their own communities. At the same time, they are also influenced by the

formal reform processes promoted by foreign peacebuilding actors that are introducing

‘enlightened’ discourses of democracy, participation and ‘rights’ into institutions and

societal structures. Yet, women and local women’s organisations were not observed to

wholeheartedly or passively adopt external approaches and discourses of peacebuilding.

Rather, they seem to strategically translate these into concepts and language that are

relevant to building peace at the local level. This process of negotiation between the

‘local’ and ‘external’ is indicative of an ongoing process of constructing meanings of

peace and rights by women at the grassroots and is a key theme addressed in this thesis.

The ability of internationally funded women’s peacebuilding initiatives to empower

women has also been questioned in a recent study in Africa: the study concluding that

such initiatives were ‘designed less to empower women than as a sop to donors,

international observers and, all too frequently, local women themselves’ (ICG 2006: 16).

Indeed, while there has been greater attention in recent years to engaging women in the

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

4

peacebuilding process, often women’s meaningful participation in internationally

designed programs has been questioned (Cockburn 2001; Mertus 2004; Pankhurst 2005).

Not the least of which because of the exorbitant attention awarded, such as in the use of

UN Security Council Resolution 1325 on Women Peace and Security (UN 2000), to

increase women’s participation in peacebuilding and empower them through raising their

awareness of their rights. At a conceptual level, the introduction of rights-based

instruments2 to empower women in peacebuilding remains largely unproblematic for

most organisations and scholars. In particular, the relationship between ‘raising

awareness’ and actual empowerment has not been critically examined and most often

assumed to be one and the same thing. That is, linkages between ‘rights-based

approaches’ and peacebuilding are often taken for granted which results in no

consideration beyond women’s ‘participation’ in activities that ‘raise awareness’ about

their rights.

In Nepal, this is a particularly salient issue in the context of a merging of development

practice by international, government and civil society actors to incorporate rights

alongside a ‘gender perspective’ in the broader peacebuilding project. Stemming largely

from the general accord that human rights are a central issue underlying both the conflict

(i.e., lack of rights or violation of rights) and the peace process (i.e., instigating or

consolidating rights to assure democracy and equity), the discourse of rights is

hegemonic – from the parties to the conflict, the United Nations (UN), international

actors and civil society organisations (Hannum 2006; Pant 2007). This growing

convergence of activities on rights in Nepal with the peacebuilding project, argues

Green3, requires a vigilance of sorts by development agencies and practitioners, as well

as academics. Indeed, the use of a ‘rights-based approach’ has influenced many aspects

of project design and implementation within development practice in Nepal, including in

peacebuilding initiatives. Yet the rights-based approach as an evolving and emerging 2 ‘Rights-based instruments’ are here defined as human rights conventions, declarations, resolutions and other documents created by the United Nations. These define particular sets of rights enshrined in international law, or particular commitments on rights which parties to an instrument must fulfill. 3 Paula Green, 2007. Fostering the Ties that Bind: Practicing Peacebuilding and Development in Conflict Sensitive Environments. Keynote address at the International Conference on Sustainable Development in Conflict Environments: Challenges and Opportunities, 16-18th January 2007, Kathmandu, Nepal. Available at: http://www.karunacenter.org/documents/Nepalkeynote.doc

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

5

technique of development is in its infancy and yet to be scrutinised in depth, particularly

in relation to the universal sets of women’s rights promoted through human rights

instruments (Bracke 2004; Bradshaw 2006; Dzodzi 2004). At the same time, an

emergent consciousness of Nepalese women and women’s organisations that is becoming

evident also reveals a strategic borrowing and ‘appropriation’ of ideas, approaches and

values on rights which are being introduced by international actors. The constructions of

meanings attached to rights as promoted by international development actors, and the

way these are being reinterpreted and appropriated by local women and women’s

organisations, differ in significant ways and is one of the key themes explored in this

thesis.

Within the seemingly ‘neat fit’ assumed between rights, women and peacebuilding, the

assumption that women are lacking empowerment and require their consciousness to be

raised also needs to be more critically examined. In particular, what ‘empowerment’

actually constitutes, and how its meaning is constructed for women and those actors who

aim to empower them, is rarely understood and typically, taken for granted. In short, the

implicit denial of women’s own agency within this assumption remains largely ignored in

the discourses and practices of development agencies. This continues in many countries

despite a significant body of feminist literature addressing issues of women’s agency in

conflict and post-conflict as activists and peacebuilders (Afshar 2003; Jacobs et al 2001;

Karam 2001; Manchanda 2001; 2005). Indeed, development projects and academic

discourses in Nepal most often focus on the lack of empowerment of women who are

constructed as ‘agency-less subjects in need of assistance in order to fulfill their

potential’ (Tamang 2002: 166). However, during the course of fieldwork for this thesis,

it was clear that these assumptions and beliefs may indeed be unfounded.

Nonetheless, Nepalese women are observed to be emerging as agents of change in the so-

called ‘New Nepal’. An emergent consciousness about their roles and rights was evident

in a range of activities in which women participated. The increasing engagement and

participation by women in activities aimed at bringing about fundamental societal

changes thus suggests a significant rupture with their past roles and identities. Indeed,

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

6

the current reshaping of women’s roles and identities mirrors the broader process of

reform being touted by political leaders and civil society activists in the visioning of a

New Nepal. While it is difficult to identify the longer term impacts of the Maoist

‘People’s War’ on gender roles and relationships, there is evidence to suggest that a

number of private and public spaces are merging in the ‘aftermath’ that is allowing new

spaces to be occupied by women (Manchanda 2006; Sharma and Neupane 2007). This

supports the notion that there is indeed a rupture with the past taking place. As the

participants in the human rights training program revealed when they passionately sang

the chorus to close the day’s program, dynamic changes are taking place that appear to

have brought with them a sense of hopefulness and enthusiasm about their roles in a

peaceful society. That is, the end of the conflict and the project to create a New Nepal

has paved the way for new spaces in which the marginalised and socially excluded,

particularly women, can be recognised as active agents in building peace.

Aims and objectives

This thesis aims to better understand the forms of engagement by Nepalese women in the

broader peacebuilding project in order to explore the relationship between participation

and empowerment. It will contribute to the emergent body of knowledge on women and

peacebuilding as called for recently by a number of scholars (Manchanda 2005;

Pankhurst 2005; Sharma 2007; Strickland and Duvvury 2003)4. It especially seeks to

better understand the influence of international actors in supporting or promoting the use

of rights-based approaches by focusing on presenting the case of Nepalese women’s

engagement in peace activism. In this way, the relationship between external and internal

processes of engagement will be drawn out. One of the primary objectives of the thesis is

therefore to present the case of everyday practices of Nepalese women involved in peace

and human rights activities in order to highlight the ongoing construction of meanings

that occur through the process of engagement itself. It will also provide an understanding

of the broader practices in relation to peacebuilding in Nepal and the role that human

rights discourses and instruments are playing in this process.

4 A comprehensive account of the current literature on gender, peacebuilding and development is included in Appendix 1: Gender and Peacebuilding: A Review of emerging literature in Development.

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

7

The main research question in this thesis is, ‘Do international peacebuilding initiatives

and instruments ‘empower’ local women?’

In order to answer this question, a number of secondary questions posed are as follows:

1. What are the forms of engagement by Nepalese women in peacebuilding processes?

2. How do women define ‘peace’, ‘peacebuilding’ and ‘empowerment’? How are these

concepts defined and understood by international actors and collaborators involved

with local women?

3. What influence do international rights-based instruments such as Resolution 1325 and

‘rights-based approaches’ have on the peacebuilding activities of women?

4. What factors hinder or support women’s empowerment?

One of the key arguments in this thesis is that prescriptive international approaches to

peacebuilding overlook the local realities of gender roles and identities and the cultural

context within which women’s empowerment is facilitated or hindered. This often

results in an unnecessary dichotomy between local and international meanings and

approaches to women’s peacebuilding, precisely because local women’s perceptions and

meanings of empowerment are omitted from consideration. In particular, the assumption

held by international actors and donors that raising women’s awareness of human rights

is a means to empower them is limited and in fact denies the agency of women

themselves in their own empowerment. This leads to the second key argument, that

Nepalese women construct meaning as part of an ongoing process of engagement in

peacebuilding and human rights activities and it is through this process that

empowerment can be located. It is difficult, therefore, to consider notions such as

‘peace’, ‘peacebuilding’, ‘human rights’ and ‘empowerment’ as anything but fluid and

difficult to categorically define or situate entirely within the confines of template

international programs that are transported into the local context. Indeed, local women

and women’s organisations do not passively adopt the peacebuilding and human rights

concepts being imposed in society. Rather, they strategically appropriate and reinterpret

them according to their own needs, values and aspirations. By participating in

peacebuilding in their own unique ways, and translating rights into their own ‘language’

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

8

at the community level, women have created a platform on which to collectively voice

their concerns and thus foster collective strategies for empowerment. In short, there is an

unexpected and positive outcome in this process of engagement which has enabled

Nepalese women to assert their agency and negotiate an opening of space for themselves

at both formal and informal levels of society.

Conceptual Framework: Responding to the call for a discourse of women and

peacebuilding

The need to critically examine the meanings and understandings of peacebuilding is

based on the findings of a number of scholars who argue that these may differ

significantly between various actors (Cutter 2005; Llamazares 2005). In particular, the

need to explore how women’s understandings of peacebuilding are mediated by gender

and their cultural context is well documented (Mazurana and McKay 1999; De la Rey

and McKay 2006). In contrast to ‘peacebuilding’, the concepts of ‘participation’,

‘empowerment’ and ‘gender’ have attracted much scholarly critique within development

studies over the last decade5. As a concept, ‘participation’ in development is ideally

aimed at ‘giving voice’ to those otherwise excluded from decision-making and thus

empower them by placing them at the centre of the development process (Chambers

1997; Rowlands 1997). In this participatory approach, development scholars and

anthropologists have questioned ‘whose voices’ are actually heard and ‘whose reality

counts’ as being significant issues (Chambers 1997; Cornwall 2003). Likewise,

alongside ‘participation’, the term ‘empowerment’ is a highly contested concept as is

often assumes power needs to be ‘granted’ from the ‘outside’ (Batliwala 2007; Kabeer

2001; Rowlands 1997). Further, within development studies there remains much critique

of the widening use of ‘empowerment’ and the limits on addressing issues of gender and

5 For instance, ‘participatory development’ has been critiqued for focusing on the ‘local’ as a means to empower individuals, as if there were no inequalities of power, particularly in relation to gender (Mohan, G., and K. Stokke, 2000. Participatory development and empowerment: the dangers of localism. Third World Quarterly, 21 (2): 247 – 268). For further critiques of the use of ‘participation, ‘empowerment’ and ‘gender’ see Batliwala, S., 2007. Taking the power out of empowerment – an experiential account. Development in Practice, 17 (4-5): 577-565; Cornwall, A., 2003. Whose voices? Whose choices? Reflections in gender and participatory development. World Development, 31(8): 1325-1342);

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

9

power6. Despite such detailed critiques within development studies, however, only a few

scholars (Mullholland 2001; Pankhurst 2000) address the difficulty of assuming that

women’s participation in peacebuilding will lead to their empowerment - this is a key

theme explored in this thesis.

The emergence of rights in the discourse of women and peacebuilding

From a different perspective, the surge of rights-based development has also significantly

reshaped the landscape. For instance, empowerment is now almost synonymous with

human rights and human rights education at the grassroots level (Brouwer et al 2005;

Ensor 2005; Mertus 2004). This has meant that the connection between women’s

participation in peacebuilding and their empowerment with respect to rights has

infiltrated project design and implementation. In this approach, women’s empowerment

is often assumed to be constituted not only through their participation, but through raising

their awareness on issues of rights. Unpacking such assumptions and exploring how

rights ‘instruments’ impact upon women’s empowerment in Nepal in fact suggests that

this assumption cannot be taken for granted.

Indeed, human rights has assumed a central position in the discourse surrounding

international development evidenced in the emergence of ‘Rights-Based Approaches’

(RBAs) (Eyben 2003; Gready and Ensor 2005; Sengupta 2000; Uvin 2007) 7. This

approach aims to empower ‘rights-holders’ to exercise their rights as active agents to

demand justice by assigning roles and responsibilities for ‘duty-bearers’ (Gready and

Ensor 2005b: 44)8. In this process, International Non-Government Organisations

(INGOs) are increasingly identifying their organisations as ‘duty-bearers’ of rights and

thus practitioners serve and are accountable to them (Gready and Ensor 2005b). From

6 For instance, Cornwall argues that empowerment is one of ‘the most corrupted terms’ (2007: 581) in development, which Batliwala (2007) argues the wide use of the term serves to overlook power relations. 7 Rights discourses have entered development within a framework defined by the UN. For a study on the movement of rights into development see Nguyen, F., 2002. Emerging Features of a Rights-Based Development Policy of UN, Development Cooperation and NGO Agencies. Bangkok, OHCHR. 8 At the core of the discussion on the utility of rights-based approaches are the duties and accountabilities which it raises. See Gready, P., and Ensor, J., 2005. Introduction. In P. Gready and J. Ensor (eds.), Reinventing Development: Translating Rights-Based Approaches from theory into practice. London and New York, Zed Books: 1-44.

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

10

one perspective, rights-based approaches have been embraced by organisations in the

field of women’s rights given the potential of this approach to address gender inequalities

and enhance women’s agency (Cornwall and Molyneux 2006: 1178; Strickland and

Duvvury 2003: 20; WÖlte 2002). Yet from another perspective, a more critical

evaluation of rights-based approaches suggests these have not improved outcomes for

women’s rights or empowerment (Dzodzi 2004; Jonsson 2005). A number of scholars

argue that this is due in large part to restrictive UN frameworks that neutralise women’s

rights into ‘a basic set of universal needs’ (Bracke 2004; Bradshaw 2006: 1334). One

such framework is UN Resolution 13259, which has promoted scholarly analysis of

women’s participation in formal peace processes (Anderlini 2007; Porter 2007), as well

as informal or community peacebuilding (Pankhurst 2005; Cockburn 2007)10. In Nepal,

this Resolution is also used by development actors to empower women engaged in

community peacebuilding (Sharma 2007). Yet as Strickland and Duvvury (2003)

highlight, the potential for human rights instruments such as Resolution 1325 to empower

women in peacebuilding requires further examination.

As a result of these analytical and methodological imperatives, I undertook research in

Nepal in early 2007. The fortuity of being able to conduct research in Nepal at this time

meant I was a participant observer to the processes of women engaging in the peace

process and Nepalese citizens demanding their rights in a society undergoing rapid post-

conflict transformation. A case study of the ‘Women's Empowerment for Sustainable

Peace and Human Rights’ program implemented by the Institute of Human Rights

Communication in Nepal (IHRICON), which aims to empower women as ‘Community

Peace Volunteers’(CPVs), was undertaken. This provided a particularly useful starting

point from which to explore the main research question. My observations and analysis of

this program allows for a discussion of findings on the broader issues of women’s rights,

empowerment and agency in peacebuilding.

9 Resolution 1325 does not grant rights of itself, but it reaffirms ‘the need to implement fully international and humanitarian and human rights law that protects the rights of women and girls during and after conflicts’ (UN, 2000: Paragraph 9), and calls on parties to fulfill obligations under various UN Conventions such as CEDAW. The full text is in Appendix 2. 10 Three books released in October 2007 by Sanam Anderlini (2007) Cynthia Cockburn (2007) and Lis Porter (2007) on women’s roles in peacebuilding are testament to increasing scholarly engagement.

Introduction: “We Want to See a New Nepal!”

11

Thesis Overview

This thesis is divided into seven Chapters including the Introduction and the Concluding

remarks. The Introduction provides a broad context within which to situate the key

literature, outlines the aims and objectives of the study and introduces the conceptual

framework governing the thesis. This framework informs the choice and interpretation of

data. Chapter One then provides a context of the current social and political changes

taking place in Nepal during transition from armed conflict. It provides an overview of

rights and social inclusion in the peace process, explores women’s roles in post-conflict

transition and the engagement of international actors in Nepal. The second Chapter

describes the methodological approach taken in field research which is of critical

importance in understanding how the research findings evolved and were derived. The

findings and analysis of the research have been divided into three discussion Chapters.

The first of these is Chapter Three which explores how the meanings of peace and

peacebuilding are constructed and defined by women in contrast to international actors.

In Chapter Four, the understandings of empowerment held by women and local and

international organisations are explored. Women’s engagement in Peace Groups is also

discussed as a means of enabling women’s collective empowerment. Chapter Five

explores the process of disseminating and raising awareness on human rights information

through Resolution 1325. Further, it examines the relationship between rights awareness

and empowerment, and the process of universal human rights language being

appropriated and reinterpreted by local actors. The Concluding Chapter brings together

the findings of the thesis and summarises that women’s active agency in the process of

their own empowerment is a central element currently missing in the discourses

surrounding women, peacebuilding and human rights. Finally, I pose some questions

about the broader implications of the thesis for understanding the roles and

responsibilities of international actors engaging with women in peacebuilding.

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

12

Chapter One The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal The ‘People’s War’ and the Peace Process

The civil armed conflict in Nepal, often termed the ‘People’s War’, came to an official

end on 21 November 2006 when the Government of Nepal and the Communist Party of

Nepal - Maoist (CPN-Maoist or ‘Maoists’), signed the Comprehensive Peace Accord

(CPA). The Maoists launched the People’s War in 1996 which aimed to overthrow the

constitutional monarchy and establish a socialist republic. There have been numerous

analyses of the causes and history of the conflict (Hutt 2004; Karki and Seddon 2003;

Onesto 2005; Uprety 2005)1. In summary, causes of the conflict have been identified as

stemming from underdevelopment that is reinforced by various inequalities, that an abject

government has been unable to effectively address. The conflict claimed the lives of over

13,000 Nepalese (INSEC 2006b), forced displacement of over 150,000 people (Terre Des

Hommes 2006), and led to widespread human rights violations. Such violations have

been committed by both government security forces and the Maoists - including unlawful

killings, ‘disappearances’ and abductions, all forms of sexual violence, arbitrary arrests

and torture (ICG 2007a; INSEC 2007). Despite State commitments on human rights

made in the Peace Accord, such as ending impunity through a truth and reconciliation

commission, there remains little progress2. Further, it led to the deterioration of the

already low levels of human development3.

The Peace Accord resulted in the Maoist leadership returning into the political

mainstream by entering the Interim Parliament, and agreeing for their Maoist Army - the

People’s Liberation Army (PLA) - to be held in seven main cantonment camps around

the country under the supervision of UNMIN4. The Peace Accord also provided for the

1 For further list of studies see Simkhaka et al, 2005. The Maoist Insurgency in Nepal: A Comprehensive Annotated Bibliography. Geneva/Kathmandu: Program for the Study of International Organisations (PSIO). 2 For instance, a draft parliamentary bill to establish a Truth and Reconciliation Commission is argued to serve political leaders’ interests by offering general amnesties has been widely condemned (ICG 2007b). 3 Nepal is ranked at a very low UN Human Development Indicator Index of 140 out of 177 countries. See http://hdr.undp.org/statistics/data/cty/cty_f_NPL.html (Accessed 12 October 2007). 4 Prior to launching the People’s War in 1996, the CPN-M (Maoists) were a mainstream political party before breaking away. Tensions between the CPN-Maoist, the Seven Party Alliance and UNMIN continue

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

13

election of a Constituent Assembly (CA) which is to be held in April 2008 following two

postponed dates in June and November of 2007. The new governance structure of a

Constituent Assembly aims to build a more ‘inclusive’ democratic system able to address

the persistent problems of exclusion by promoting ‘social inclusion’5. It is hoped that by

being inclusive of gender, caste, class, ethnic, linguistic and regional differences, the

election of a Constituent Assembly will enable greater social, economic, political

participation (International Alert 2007).

Emergence of ‘rights’ as a central discourse of peacebuilding

The vision of a more socially inclusive society - that recognises the rights of all groups -

lies at the heart of the demands being made by various groups around the country in the

post-conflict period. Indeed, Nepal is a multiethnic and multi-linguistic country with

over sixty ethnic and caste groups6. Further, discrimination based caste, class, ethnicity,

geography and other divisions remain deeply embedded in social institutions and

traditions in Nepal (World Bank 2006)7. The assertion of long-standing grievances and

demanding of rights by various discriminated and traditionally marginalised groups is

mounting, which is being witnessed in both peaceful, and increasingly violent, protests

and demonstrations (see Appendix 3)8. In particular, agitating Madhesi groups in the

Terai have emerged and their violent protests have intensified following the end of armed

conflict. This has been a major factor in worsening the security situation, de-stabilising

the peace process and thus the postponement of elections9.

over the conditions inside the cantonment camps. UNMIN has led the disarming and registering of Maoists and their weapons, and their fate of the PLA remains in question until after the elections. 5 ‘Social inclusion’ refers to the removal of institutional barriers and the enhancement of incentives to increase the access of diverse individuals and groups to development opportunities (World Bank 2006). 6 A comprehensive account of gender, caste and ethnic exclusion, see World Bank, 2006. Unequal Citizens - Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal. Kathmandu: World Bank. 7 The presence of Dalit , Madhesi and Janajati in state apparatus is negligible. Only three Caste groups - Brahmin, Chhetri, Newar (Kathmandu) are economically and politically dominant (McGrew 2006: 1). 8 See Appendix 3 – Map of Bandhs/Blockades 1 Jan 2007 - 30 September 2007. Bandh is Nepalese for ‘strike’. This map identifies 31 ‘categories’ of agitating groups or organisations. 9. The Terai is the southern plain region of Nepal adjacent to India. The Madhesi people who inhabit the Terai are often discriminated by the Nepali State yet comprise over 30 per cent of the population. For a full report of issues surrounding the demands and context of the Madhesi groups and Terai region, see International Crisis Group (ICG), 2007. Nepal's Troubled Tarai Region. Kathmandu, ICG.

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

14

Without discounting the human rights violations committed during the conflict and the

fragile peace process, the Maoist movement has served to bring the rights of marginalised

and minority groups to the foreground. As one human right activist explained,

“many problems were under the surface which are now over the surface, like janajati, dalit, Madhesi, women…the issue has come up because of the Maoists. I do not believe in armed conflict …but I cannot ignore this fact.” 10 (Personal communication, Gorkha District, 19 April 2007).

Following participation of many of these marginalised groups in the Jana Andolaan II

(People’s Movement) in April 200611, there are high expectations of ‘peace dividends’

(International Alert 2007: 8). In Nepal, the notion of a ‘peace dividend’ is being used to

describe the benefits that peace and democracy will bring to people (Sharma 2007)12. As

Raj (2007) asserts, the nation and identity-building project of ‘New Nepal’ is seeing

many marginalised groups active in calling for their inclusion. That is, the momentum

from the Maoist movement and end of the People’s War has seen the underlying root

causes of the conflict becoming the centerpiece of the demands by various groups to end

discrimination and to claim their rights. This was demonstrated during fieldwork when

encountering one disenfranchised group who were using this new ‘space’ in the post-

conflict period to demand rights (Figure 4).

10 Janajati is the Nepali term for ‘Indigenous’ and denotes denotes being part of an ethnic group. Dalit is the term preferred term in Nepal for “Untouchables”, the lowest groups in the traditional Caste hierarchy. 11 The Jana Andolaan II (People’s Movement) saw hundreds of thousands of Nepalese taking to the streets for weeks in nationwide demonstrations against the Monarchy during April 2006. The movement brought brought an end to the previous period of the King’s autocratic rule and was historic in spurring peace negotiations. Jana Andolaan I took place in 1990 when people demonstrated to end the Panchayat (party-less system) era and brought the multi-party democracy. 12 This notion of a peace dividend differs from the post-Cold War international relations discourse of the ‘peace dividend’ that describe economic benefits of decreased defence spending.

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

15

Figure 4: Highway roadblock in Sindhuli District13

Nepalese women: Navigating through conflict and closed ‘spaces’

"Women are weaker in our society. They are not weaker, but the society and culture has bounded them, their hands and legs." (Personal correspondence with human rights activist, Gorkha District, 20th April 2007).

Impacts of the armed conflict on women

During the armed conflict, women were often ‘caught in the middle’ of Maoist insurgents

and security forces and faced increasing insecurity and deepening poverty (Bennett 2003:

2; Thapa 2004). The emergence of female-headed households and widows has been

significant as a result of many men joining, or fleeing, security forces and the Maoists or

migrating in search of work (Adhikari 2005; Gautam 2001). Further, women’s care 13 On completion of a human rights training program in Sindhuli, our group encountered the Chure Bhawan Ekar Sames, a protesting group blockading the Highway to Kathmandu. This group was demanding their rights to autonomy and identity in their region. Despite carrying a ‘Human Rights Defenders’ banner (a common practice that grants amnesty through strikes), our passage had to be negotiated. This was undertaken by the female Director of IHRICON, following numerous attempts by any of the men present. The group became irate, arguing that Nepalese human rights workers funded by international agencies were “corrupt” and not working for the interests of Nepalese people. Their strike lasted 7 days, crippling life in region.

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

16

giving roles often limited their mobility and discriminatory property laws often left many

women without land or a source of income - producing the phenomenon of the ‘internally

stuck’ (Gautam et al 2001; Martinez 2002). Protection issues also worsened in terms of

increased sexual violence and exploitation, including torture, rape and trafficking

(Gautam 2003; IHRICON 2007b). Impacts of the conflict have also varied depending on

the various other ‘groups’ which women identify with or belong (so-called ‘cross cutting

divides’), such as class, caste, ethnicity and religion that generally serve as further forms

of exclusion (Bennett 2003; World Bank 2006)14. Whilst women have indeed endured

great suffering during the armed conflict15, moving beyond a ‘victim lens’ also provides

an opportunity to recognise women’s agency in taking on diverse roles. For instance,

with expertise in grassroots activism, investigative journalism, human rights law and

local peace activism, women have maintained social stability and reduced violence in

community peacebuilding processes (McGrew 2006; Sharma 2007).

Women in the peace process

As a result of negative impacts of conflict on women, and perhaps the greater recognition

by international agencies, the national peace process has more recently given greater

recognition to ‘women’s issues’ (ICG 2007a). For instance, the Interim Constitution of

2007 recognises the existing problems of class, caste, region and gender and separately

lists a number ‘women’s rights’16. However, given that women’s involvement in the

Constitution drafting process was negligible17, doubts remains over how women’s rights

will be prioritised (Sharma 2007). Further, women were virtually absent during the

14 ‘Cross-cutting divides’ are often described as the ‘double burden of caste and gender discrimination’ for Dalit women (Sob 2004), or the ‘multiple barriers’ for women of Madhesi origin (Sharma 2007: 5). 15 Despite the recognition of the overwhelming impact of conflict on women in reports of international development agencies, only a few in depth-studies of the impacts on women in rural Nepal are available (Gautam et al 2001; Gautam 2003; Manchanda 2004). Further research on this issue is most timely. 16 The Interim Constitution reads: “20. Right of Woman: (1) No one shall be discriminated in any form merely for being a woman; (2) Every woman shall have the right to reproductive health and other reproductive matters; (3) No physical, mental or any other form of violence shall be inflicted to any woman, and such an act shall be punishable by law; (4) Son and daughter shall have equal rights to their ancestral property”. His Majesty’s Government of Nepal (HMGN) , 2007. Interim Constitution 2063. Kathmandu, HMGN. 17 The all-male Interim Constitution Drafting Committee was expanded to include four women and a Dalit representative only after widespread protests (McGrew 2006).

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

17

formal peace negotiations in 2006 (Sharma 2007)18. Indeed, the ‘Agreement on

Monitoring of the Management of Arms and Armies’ (AMA)19 that followed the Peace

Accord contained no provisions for women or gender despite a significant proportion (up

to 30 per cent) of the Maoists being female (Manchanda 2004; Pettigrew and

Schneiderman 2004)20. While amended electoral laws now guarantee increased women’s

candidacies and quotas in the Constituent Assembly polls, significant challenges remain

for greater representation of women’s issues (Sharma 2007)21. Indeed, political

participation of women, and women’s representation, are two separate issues as the

presence of women in decision-making roles cannot be assumed to promote women’s

rights or gender equality (Nelson and Chaudhary 1994).

Opening previously closed spaces

Sharma and Neupane (2007) argue that conflict has created an ‘opportunity’ by initiating

some ‘merging’ of the private and public spheres and opening up previously closed

spaces for women22. At the community level, there are also reports of a change in the

perceptions of gender roles and social structures (ICG 2007b; Manchanda 2006). For

instance, the absence of men was reported to have opened new opportunities for women

in Rolpa District to step into public life (Gautam et al 2001). Further, in the absence of

men, women ‘have crossed the gendered divisions of labour to take on taboo areas -

ploughing and thatching of roofs’ (Manchanda 2005: 4739). On a collective or national

level, women are becoming more actively engaged in rallies and peaceful protests on

18 There were no women in peace negotiation teams of the SPA government or the CPN (Maoist), neither in the 32-member peace committee (McGrew 2006). Despite the Maoists ‘seeing itself as the vanguard on women’s issues’ women were not included in the peace teams in 2004 and 2006 (ICG 2007a: 3), 19 The CPA-related Agreement on Monitoring of the Management of Arms and Armies (AMA) was signed by the UN and Government in November 2006 and outlined the process whereby Maoist combatants and an equivalent number of Nepal Army troops were to be confined to cantonments and barracks. UNMIN has demobilised over 30,000 of their militia and handed in over 2,500 weapons. 20 A detailed account of women’s involvement in the Maoist insurgency see Yami, H. (2007). People's War and Women's Liberation in Nepal. Kathmandu: Janadhwani Publications. 21 The Constituent Assembly Members’ Election Act (2007) provides for women to have 50 per cent of the 240 seats from the proportional representation system and to make up 33 per cent of total candidates. In practice, this in effect means that final representation could be as low as 22 per cent (ICG 2007a). 22 A description of the public and private spheres, and gender roles and relations within these, in Yuval-Davis, N., 1997. Gender and Nation. London: Sage.

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

18

issues of women’s and human rights, such as trafficking and domestic violence23. In the

public sphere, national Non Government Organisation (NGO) coalitions and alliances,

such as Shanti Malika (Women for Peace), and the All Nepal Women’s Association

(ANWA), are more actively pressuring the government on women’s issues. Sharma and

Neupane (2007) assert that these opening spaces and ‘unexpected gains’ from the conflict

need to be consolidated24. While these changes may be challenging the disempowering

construction of Nepalese women as uniformly ‘backward, illiterate, and tradition-bound’

(World Bank 2006: 50), it may also be too early to assert whether these examples are

indeed ‘gains’.

Apart from the conflict itself, the significant participation of women as Maoist insurgents

has been identified as a key impetus for raising the prominence of ‘women’s issues’

(Sharma 2007). Indeed, women have accounted for up to 30 percent of the Maoist Army

(Yami 2007). From one perspective, women’s participation is also argued to have

challenged gender relations at the local level in many rural areas (Manchanda, 2001;

2005; Pettigrew and Schneiderman, 2004). For instance, in terms of gender roles, Thapa

quotes a Maoist women saying “you see, there used to be only sickles and grass in the

hands of girls like us. Now there are automatic rifles’ (2005: 2). From another

perspective, whether taking up arms is a demonstration of women’s agency is a complex

issue that warrants further research25. This issue was also raised during the research, as

one participant in IHRICON’s program had been part of the Maoist movement during the

conflict and had now taken up peace activism.26 Nevertheless, it is important to observe

Manchanda’s assertion that ‘the massive presence of women has produced a social

23 During the April 2006 People’s movement, many women’s groups or organisations not previously in the public arena protested for the first time against the King’s absolute rule. 24 The notion of ‘unexpected gains’ from conflict is addressed by a number of scholars (Manchanda, 2001; Utas, 2005), yet is also problematic, as gains in the immediate post-conflict period are often not sustained when women must take on greater responsibilities (Manchanda, 2001: 4739; Rehn and Sirleaf, 2002.) 25 A lack of detailed research means the question of whether women joining the Maoists is a demonstration of their own agency is as yet unanswered and is grounds for further research. A growing number of scholars are exploring women’s experience as combatants in attempting to answer this question (Manchanda 2001; Moser and Clark 2001; Utas 2005). 26 This was a particularly interesting finding, however I am unable to explore it further in this thesis. The identification by informants and NGO workers interviewed that women continue to join the Maoist movement, even after the signing of the Peace Accord, warrants further investigation. Indeed, exploring the motivations behind women’s continued involvement in the Maoist movement is salient (Yami 2007).

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

19

radicalisation as evinced in ground level actions’ (2005: 4742). According to Yami

(2007), many women in rural areas have had their ‘consciousness raised’ by Maoist

ideology to assert their agency and demand their rights.

State commitments to Women

At an international level, Nepal is signatory to eight different conventions, protocols and

agreements related to the rights of women and children27. Yet these instruments have

been limited in promoting or protecting women’s rights (INSEC 2006a). While Nepal

ratified the Convention on the Elimination of all forms of Discrimination against Women

(CEDAW) in 199128, the subsequent requirement to change 85 discriminatory laws (such

as family and property laws) remains incomplete (ADB 1999; World Bank 2006: 52).

This weak enforcement of legislation and policies continues in the context of a lack of

political will, patriarchal structures resistant to change and deficient government capacity

(Banerjee 2005: 280)29.

International actors in Nepal

In the absence of a well-functioning State to uphold its obligations as a ‘duty-bearer’ of

rights, international actors such as The United Nations Mission in Nepal (UNMIN),

various UN agencies (particularly OHCHR), donors (including country governments),

financial institutions, INGOs, NGOs and other civil society organisations are playing

greater roles to fill this void (Sharma 2007)30. International presence significantly

increased following the restoration of peace and the entry UNMIN in January 2007 (Lal

2007). The subsequent ‘post-conflict reconstruction31’ donor funding has seen the

27 For a list of these, see INSEC (2006) at http://www.inseconline.org/download/Nepal_treaties.pdf. 28 The country has however only signed, but not ratified, the CEDAW Optional Protocol or the two Optional Protocols on Children. 29 For instance, the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare lacks adequate financial and human resources and the National Women’s Commission (NWC) formed in 2002 lacks a legal basis, and has been accused of its membership being dominated by High Caste women and thus not ‘representative’. 30 The National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) has limited capacity to uphold rights (ICG 2007b). 31 The World Bank (1998) define post-conflict reconstruction as encompassing not only short-term rebuilding of physical infrastructure, but also the creation of peace through rebuilding economic and political institutions and promoting social reintegration. Peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction are

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

20

number of INGOs increase from 149 to 185 during the 12 months to June 2007, and the

number of local NGOs (26,670 in July 2007) continues to rise in response32. In addition

to providing support to the Peace Trust Fund33, one major donor priority is the funding of

awareness raising campaigns on human rights.

UNMIN is a special political mission which began operation in January 2007 in Nepal to

help oversee the peace process to lead into the Constituent Assembly (CA) elections34. In

addition to arms monitoring, ceasefire monitoring and electoral assistance, UNMIN is

involved in mine action, child protection, social inclusion, gender and human rights

activities35. On rights issues, parties to the Peace Accord expressly requested the Office

of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) to take responsibility for

monitoring human rights during the peace process. The strong rights focus of

international engagement is having a significant influence on how human rights issues are

being presented and disseminated.

‘Speaking on behalf of women’: Relationships between women and peacebuilding

actors

It is often through local NGOs and other women’s civil society organisations that women

participate in community peacebuilding initiatives in Nepal (CCO 2006). These

organisations often act as the implementing partners for INGOs and other funding bodies

and are thus often bound in terms of the funds they can apply for or projects they can

implement (UNIFEM 2006). Women’s peacebuilding in Nepal is also promoted through

the donor coordination mechanism of the Peace Support Working Group (PSWG) on

thus often considered analogous. However, in this thesis peacebuilding is considered one component of a longer term process of post-conflict reconstruction (Barakat 2004). 32 ‘Foreign aid to INGOs increased to Rs 12 billion’. The Rising Nepal, 19 June 2007, p4. 33 The Peace Trust Fund is managed by the UNDP and mainly supports the management of camps and reintegration of former combatants; rehabilitation of Internally Displaced People (IDPs); preparation for elections and strengthening law and order (UNDP 2005). 34 UNMIN was established by UN Security Council Resolution 1740 at the request of the Nepalese government (UN 2007). It is a political mission without prior military, policing or peacekeeping functions. 35 UNMIN’s mandate includes monitoring arms and armed personnel of the Royal Nepalese Army (RNA) and Maoist Army, assisting parties to implement the AMA, providing technical assistance to the Election committee to conduct the elections in a free and fair atmosphere.

Chapter One: The social and political context of post-conflict Nepal

21

Resolution 132536. This is mainly used to inform policy whilst also engaging in various

advocacy and dissemination activities37. Resolution 1325 is being promoted by many

INGOs and increasingly being utilised as a training tool in women’s peacebuilding

initiatives (UNIFEM 2006).

To conclude, this discussion has demonstrated that in the current social and political

context of post-conflict Nepal, a significant ‘space’ has been opened for women to

actively engage and participate in constructing new roles and identities. These

opportunities are due on one level to the greater prominence of ‘women’s issues’ in the

post-conflict environment and the spaces this has created to be more active. On another

level, this is also a result of the national and international focus on the peacebuilding

project that encompasses human rights and women’s empowerment. That is, since the

end of the armed conflict in late 2006, increasing numbers of women have become

engaged in peace activism and in asserting their rights in various ways. Documenting the

experiences and perceptions of women activists forms the key approach assumed in this

research.

36 The Resolution 1325 Peace Support Working Group (PSWG) was set up in early 2007. It is co-chaired by UNFPA and the Norwegian Embassy, and one of the most active of the four working groups – the other three forums are on Transitional Justice, Reintegration and Constitutional Reform and the Elections. 37 These activities include a workshop on Resolution 1325 for UN agencies, donors and NGOs, conducting advocacy with decision making bodies and publishing and disseminating 1325 materials at both grassroots and national levels.

Chapter Two: Methodological approach

Chapter Two Methodological approach This Chapter aims to provide an insight into the social and research processes involved in

producing this thesis. The broader narrative of this thesis is informed by four months of

fieldwork in Nepal from February to June 2007. Most time was spent with a Nepalese

human rights NGO, the Institute of Human Rights Communication in Nepal (IHRICON).

Amongst other organisational activities in IHRICON’s Kathmandu headquarters, I was a

participant observer in two human rights trainings workshops in the Districts of Gorkha

and Sindhuli (See Appendix 4 for Districts of Nepal and Study Areas). These human

rights trainings were attended by women from Four Districts (Gorkha, Sindhuli, Kailali

and Dang) as part of IHRICON’s Community Peace Volunteer (CPV) initiative. During

this time, a number of semi-structured interviews were conducted with the Peace

Volunteers, NGO staff and trainers. As such, the research sites varied from participation

in formal or semi-formal institutional processes, to informal discussions with individuals.

In order to explore shared understandings of meanings of ‘peace’, ‘rights’ and

‘empowerment’, I also conducted a focus group consisting of 12 participants from the

Sindhuli District Peace Group.

Selecting a case study in Nepal

The selection of Nepal as a focus of study was influenced by a number of considerations.

First and foremost, scholarly and policy debates on women, peace and security are rarely

applied to Nepal. Secondly, previous volunteer work by the author with various

Nepalese NGOs has enabled an ongoing interest and exposure to women’s roles and

identities in Nepalese society1. Furthermore, during previous work and travel, the author

strongly associated with Pigg’s ‘inability to escape involvement in the discourse of

development wherever I went in Nepal’ (1992: 493).

1 Such exposure has included observation of Mothers Groups (Aama Samuha) providing community support in the absence of men during the conflict, observing many social impacts of the conflict at the local level, and being a participant observer to the process of local NGOs engaging women at the same time as those organisations being engaged by the international community.

22

Chapter Two: Methodological approach

An in-depth case study of a program enables the collection of extensive data on the

individuals and the program itself, including observations, interviews, documents and

audiovisual materials, while interacting regularly with the people being studied (Leedy

1997). Whilst the efficacy of case studies often lies in their ability to help others draw

conclusions on whether the findings may be applied to other situations or practices

(Leedy 1997: 136), the ability to draw conclusions and apply findings over a wide range

of situations can also be a weakness. The intention in this thesis, therefore, is not to

suggest that the findings are necessarily generalisable to other women’s peacebuilding

programmes in Nepal or elsewhere, nor that one case study could be representative. My

choice of case study was based on one which would fulfill the criteria of a ‘telling’ rather

than a ‘typical’ case (Mitchell 1984: 203). Further, although my theoretical stance on

women’s peacebuilding and rights-based approaches influenced the choice of

methodology, practical issues also shaped my approach. In particular, the security

situation in Nepal limited access to certain areas which precluded extensive ethnographic

research with Peace Groups at the village level. A multi-sited case study thus presented

the most appropriate and realistic means to undertake an in-depth exploration of women’s

participation in community peacebuilding initiatives2.

Negotiating the field

Following arrival in Nepal I gained an overall sense of the current social and political

post-conflict context for women and peacebuilding programs by means of a ‘big net

approach’ (Fetterman 1989). Working from an initial network of key informants in

Kathmandu (most of whom I knew previously), I employed a ‘holistic’ snowballing

technique, using word of mouth and drawing on people’s individual networks. Key

informants provided information that facilitated further contacts. In a similar way to

2 A number of studies of women’s peace initiatives in other countries produced by feminist scholars have also used multi-sited in-depth case studies of organisational initiatives as starting points from which to explore issues of women’s participation and their engagement by international actors. Some examples drawn from are: Cockburn, C., 1998. The Space Between Us: Negotiating Gender and National Identities in Conflict. London and New York, Zed Books; De la Rey, C., and McKay, S., 2006. Peacebuilding as a Gendered process. Journal of Social Issues, 62 (1):141-153; and Moghadam, V., 2005. Peacebuilding and Reconstruction with Women: Reflections of Afghanistan, Iraq and Palestine. Development, 48 (3): 63-72.

23

Chapter Two: Methodological approach

conducting ethnographic fieldwork, I needed to gain access to an organisation on which

to base a case study in order to answer the general research problem. This usually

involves going through a ‘gatekeeper’ - a ‘person who can provide smooth entrance into

the site’ (Leedy 1997: 137). Discussions with key informants and organisations led to

finding a suitable host organsiation. This arrangement took place by means of

negotiating and entering an ‘exchange relationship’ with the Institute of Human Rights

Communication in Nepal (‘IHRICON’), who’s Director became my ‘gatekeeper’.

Contribution to a research publication on sexual violence (IHRICON 2007b) was the

primary component of my exchange, in return for which I was granted access to

organisational resources events and trainings in Kathmandu, and enabled safe passage,

access and support to undertake research at two separate field sites in Gorkha and

Sindhuli.

Host organisation: The Institute of Human Rights Communication in Nepal

(IHRICON)

IHRICON is a non-profit, non-political human rights and communication NGO

established in 2001 by a group of human rights, peace and media professionals. It

receives funding from a wide range of donors including the Canadian Cooperation Office

(CCO) 3, the British Embassy, Save the Children-Norway, UNDP, UNIFEM and USAID.

It has a permanent project staff of four in Kathmandu, a VSO4 volunteer, three office

staff, a pool of training consultants and Peace Volunteers in four Districts. IHRICON

serves as the Secretariat of Shanti Malika (Women for Peace) Network and is an active

member of numerous others5.

3 The CCO is the implementing office for the Canadian Agency for International Development (CIDA) in Nepal. 4 The Voluntary Service Organisation (VSO) is a volunteer sending scheme coordinated by the British government. In most cases, the role of skilled/professional VSO volunteers is to build the capacity of the local organisation. 5 These networks include the Federation of Nepali Journalists (FNJ), the Beyond Beijing Committee, South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Women for Peace (Shanti Malika), IANSA, the Collective Campaign for Peace (COCAP), amongst others. IHRICON is a also a networking and advisory member of Human Rights Treaty Monitoring Coordinating Committee (HRTMCC).

24

Chapter Two: Methodological approach

IHRICON has implemented the ‘Women's Empowerment for Sustainable Peace and

Human Rights’ program from 2003 to 2006 with funding from the CCO. This program

aimed to ‘increase women’s visibility and meaningful participation in peacebuilding and

community decision-making processes’, that focuses on ‘the empowerment of women,

reducing existing conflict prevailing in the society and forming women’s groups for

income generation’(CCO 2006: 13). The central component of the program is the

training of ‘Community Peace Volunteers’ (CPVs). Twenty five to thirty Peace

Volunteers have been trained in each of the four target Districts. Each Volunteer

manages a Women’s Peace Group (Mahila Shanti Samuha) which has anywhere from 15-

40 women, in their respective communities at the Village District Committee (VDC),

ward and village level6. Women were selected and encouraged to participate in the

program from urban and rural backgrounds, from Dalit and other caste groups, various

ethnic groups, from Hindu and Buddhist religions, various political backgrounds and

range from around 17 to 50 years of age7.

Despite official program funding ending in 2006, the Peace Volunteers continue their

community work and two recent initiatives have been funded by international donors to

further their work. The first of these, funded by the British Embassy, was a ‘Training

program on human rights, good governance, constituent assembly and community

journalism for community rights activists of Kailali, Dang, Gorkha and Sindhuli’

conducted in Gorkha District headquarters from 6-13 April 2007 for eight days8. The

second program on ‘Gender monitoring around cantonment camps’, was initiated by a

training held in Sindhuli District headquarters from 17-23 April 20079. This training was

attended by 12 Peace Volunteers from Sindhuli District to become ‘human rights

6 Nepal has 75 Districts, each divided into many Village District Committees (VDC’s). The VDC is the lowest level of government administration in Nepal, which are further divided into wards then villages (Pigg 1992). Also See Appendix 4 for Districts. 7 All major political parties, including CPN (Maoist), were ‘represented’ amongst the 48 participants in Gorkha. The ‘selection criteria’ for the women to participate was the completion of their Senior Leaving Certificate (SLC), equivalent to Year 10 in Australian Standards, to ensure minimum literacy levels. 8 This training was attended by 48 Peace Volunteers, 12 from each District. (See Appendix 5). 9 This program was conducted in two Districts of Kailali and Sindhuli. The initial training sessions were conducted simultaneously and the security situation in Southern Nepal limited my access to that site and upon recommendation from informants and IHRICON I accompanied staff to the training in Sindhuli District. The program for the Sindhuli training is attached in Appendix 7.

25

Chapter Two: Methodological approach

defenders’ as part of a six month program to monitor and report on the human rights

situation around cantonments in Sindhuli District. One day of this period in Sindhuli

District was also spent at the main Sindhuli cantonment site. The rights-based approach

of the organisation, and trainings that aim to empower women as peacebuilders, meant

this case study was a particularly useful starting point to explore the research question

and thus address a number of gaps identified in the literature.

Analytical and methodological scope of research

The analytical and methodological approach taken in this thesis is eclectic and draws on

various disciplines and fields of study - from development studies, peace studies, conflict

resolution, peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction, human rights and

anthropology. Further, it is strongly influenced by a number of conceptual and

methodological approaches from feminist studies. Firstly, feminist anti-essentialist

critiques which argue against the portrayal of ‘women as victims’ in post-conflict and

promote an approach which focuses on women’s agency informed the methodological

approach10. Secondly, employing methods informed by both scholarly and practitioner-

based experience and research was also one means of ensuring the research could bridge

gaps between wide-ranging theory and practice11. For instance, the action research of a

number of scholar-practitioners such as Cynthia Cockburn (1998; 2007) and Donna

Pankhurst (2000; 2005), amongst women’s organisations in conflict and post-conflict