Saint Olaf/Sanctus Olavus

-

Upload

francesco-dangelo -

Category

Documents

-

view

62 -

download

1

description

Transcript of Saint Olaf/Sanctus Olavus

Sanctus Olavusby Lars Boje Mortensen (Legenda), Eyolf Østrem (Officium) and ÅslaugOmmundsen (Missa)

Sanctus Olavus, The Norwegian royal martyr saint, Olaf Haraldsson (d.1030), became the most renowned local saint in the Nordic countries, as isevident from the great number of church dedications, place names, piecesof art, and texts. Little is known of his cult in the eleventh century,but during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries his shrine in Trondheimwas turned into a major site of pilgrimage and celebration. The Nidaroscathedral was constructed and a series of liturgical, musical and literarymonuments were composed. His status as a national saint remaineduncontested, but his cult also diffused outside of Norway and assumedother functions.

Here the focus is on the Latin texts relating to Olaf. For recent surveysof the historical Olaf Haraldsson, the cult, art and musical history, andthe Old Norse texts see SVAHNSTRÖM (ed.) 1981, KRÖTZL 1994, KRAG 1995,RUMAR (ed.) 1997, LIDÉN 1999, EKREM, MORTENSEN & SKOVGAARD-PETERSEN (eds.)2000, ØSTREM 2001, MUNDAL & MORTENSEN 2003, RØTHE 2004.

The first critical edition of all the versions of Olav's Latin legend wasfinished (as a dissertation) by JIROUSKOVA in 2011 (see bibliography)after the present article had been written. It therefore reflects thestatus of research before her mapping and analysis of all textualwitnesses and her critical edition (about to be published).

Contents1 Legenda

1.1 Title♦ 1.2 Incipit/explicit♦ 1.3 Size♦ 1.4 Editions♦ 1.5 Translations♦ 1.6 Commentaries♦ 1.7 Date and place♦ 1.8 Summary of contents♦ 1.9 Composition and style♦ 1.10 Sources♦ 1.11 Purpose and audience♦ 1.12 Medieval reception andtransmission

♦

•

2 Officium2.1 Metre/rhythm♦ 2.2 Size♦ 2.3 Editions♦ 2.4 Date and place♦ 2.5 Summary of contents♦ 2.6 Literary and musical models♦ 2.7 Medieval reception andtransmission

♦

•

3 Missa3.1 Title♦ 3.2 Editions♦ 3.3 Date and place♦ 3.4 Summary of contents♦

•

3.5 Sources♦ 3.6 Purpose and audience♦ 3.7 Medieval reception andtransmission

♦

3.8 Sequentiae♦ 3.9 A. Lux illuxit

3.9.1 Incipit/explicit◊ 3.9.2 Size◊ 3.9.3 Editions◊ 3.9.4 Recordings◊ 3.9.5 Translations◊ 3.9.6 Date and place◊ 3.9.7 Summary of contents◊ 3.9.8 Composition and style◊ 3.9.9 Sources and literarymodels

◊

3.9.10 Purpose and audience◊ 3.9.11 Medieval receptionand transmission

◊

3.9.12 Printed books:◊

♦

3.10 B. Postquam calix Babylonis3.10.1 Incipit/explicit◊ 3.10.2 Size◊ 3.10.3 Editions◊ 3.10.4 Translations◊ 3.10.5 Date and place◊ 3.10.6 Summary of contents◊ 3.10.7 Composition and style◊ 3.10.8 Sources and literarymodels

◊

3.10.9 Purpose and audience◊ 3.10.10 Medieval receptionand transmission

◊

♦

3.11 C. Predicasti dei care3.11.1 Incipit/explicit◊ 3.11.2 Size◊ 3.11.3 Editions◊ 3.11.4 Recordings◊ 3.11.5 Translations◊ 3.11.6 Date and place◊ 3.11.7 Summary of contents◊ 3.11.8 Composition and style◊ 3.11.9 Sources and literarymodels

◊

3.11.10 Purpose and audience◊ 3.11.11 Medieval receptionand transmission

◊

♦

3.12 D. Veneremur sanctum istum3.12.1 Incipit/explicit◊ 3.12.2 Size◊ 3.12.3 Edition(s)◊ 3.12.4 Translations◊ 3.12.5 Date and place◊ 3.12.6 Summary of contents◊ 3.12.7 Composition and style◊ 3.12.8 Sources and literarymodels

◊

3.12.9 Purpose and audience◊

♦

4 Bibliography•

Legenda(BHL 6322-6326). For the present purpose the numerous versions of thelegend are grouped under five headings, A-E, each referring to the text ofthe most important extant manuscript (see more information under editionsand medieval transmission below). These letter codes will be used here aspreliminary signposts for describing the surviving versions, not as anattempt at an exhaustive classification (the text published by STORM 1880as Acta Sancti Olavi is not included here, because it is a secondaryconstruct on the basis of a surviving vernacular version). The texts areusually easy to divide into a passio (or uita) and a miracle part. Thedifferences between the versions are most conspicuous in the narrative ofthe first part, the passio. A gives the fullest passio account (ca. 5pp.), B a very short abbreviation (half a page), hence the reference inthe scholarly literature (and below) to a long and a short passio (orvita). In reality the ?short? versions represent different extracts fromwhat we suppose to be an original close to A. The second part, themiracles, is in general textually more stable between the versions, butthe selection of miracles differs widely. The miracles will be countedaccording to the longest series as they appear in the major earlymanuscript (version A, Oxford, Corpus Christi College 209, from FountainsAbbey), namely 1-49. Only one miracle has been transmitted in Latin in theHigh Middle Ages (A, B, C) which is not present in this manuscript, theMiles Britannicus miracle, for practical purposes numbered here as 50. Allthese 50 miracles are posthumous, except no. 1, Olaf?s vision before thebattle of Stiklestad, and no. 10, his trial for working on a Sunday. Theadditional late medieval miracles, performed by Olaf while still alive,are integrated into various late medieval versions of the Passio (D, E)and are not counted separately.

A Fountains Abbey (late twelfth cent.): long passio, miracles 1-49.• B Anchin (late twelfth cent.): short passio, miracles 1-9, 50, 10-21.• C Sweden (around 1200) rewritten passio (fragmentary transmission).• D Köln (ca. 1460) rewritten passio with more miracles.• E Ribe (ca. 1460-65) rewritten passio with more miracles.•

Title

The legend is traditionally referred to as Passio Olaui, but a morecorrect form authenticated by the Fountains abbey manuscript is Passio etmiracula beati Olaui reflecting the clear division into two parts. Inlater medieval manuscripts other versions are entitled Legenda sanctiOlaui, De sancto Olavo rege Norwegie and sim. or are left without a title.

Incipit/explicit

A Regnante illustrissimo rege Olauo apud Norwegiam ? libere quo uoluitsuis pedibus ambulauit. B Gloriosus rex Olauus ewangelice ueritatissinceritate in Anglia comperta ? Qui cum patre et spiritu sancto uiuit, etregnat Deus per omnia secula seculorum. amen. C [mutilated at thebeginning] ... Ecclesias et loca sancta oracionis ? et regnat in seculaseculorum. amen. D Gloriosus martir Olauus norwegie rex per aliquorumsanctorum uirorum predicationem conuersus ? multarum rerum ornatapreciositate: in qua ipse requiescit testatur ecclesia. E In Nederosmunitissimo castro tocius Norvegie regni ¬? cui est omnis honor et gloriain secula seculorum.

Size

A runs to ca. 40 pp., the others from around 5 to 15 pp. The variousextracts for liturgical readings make up ca. 1 to 3 pp.

Editions

Jacobus de Voragine, Legenda aurea [+ Historie plurimorum.... CHECK],Köln 1483, 307a-308d. [version D including miracles 2,5,4].

•

Breviarium Otthoniense (Odense), Lübeck 1483 & 1497 (repr. in STORM1880, 255-64) [short passio, miracle 1].

•

Historie plurimorum sanctorum nouiter et laboriose ex diuersis librisin unum collecte, Louvain 1485, 101-103v (repr. in STORM 1880,277-82) [version D including miracles 2,5,4].

•

Breviarium Lincopense (Linköping), Nürnberg 1493 (repr. in STORM1880, 247-51) [short passio, miracles 1,2,4].

•

Breviarium Strengnense, Stockholm 1495 (repr. in STORM 1880, 255-64)[short passio, miracle 1].

•

Breviarium Upsalense (Uppsala), Stockholm 1496 (repr. in STORM 1880,255-64) [short passio, miracle 1].

•

Breviarium Scarense (Skara), Nürnberg 1498, f. CCLVII verso. (repr.in STORM 1880, 251-54) [long passio, no miracles]

•

Breviarium Aberdonense (Aberdeen), Edinburgh 1509/1510 (repr. inMETCALFE 1881, 117-18) [short passio, miracles 1,2,4].

•

Breviarium Slesvicense (Sleswig), Paris 1512 (repr. in STORM 1880,265-66) [short passio, miracles 1,2,10,5].

•

Breviarium Arosiense (Århus), Basel 1513 (repr. in STORM 1880,255-64) [short passio, miracle 1].

•

Breviarium Roschildense (Roskilde), Paris 1517 (repr. in STORM 1880,255-64) [short passio, miracle 1].

•

Breviarium Lundense (Lund), Paris 1517 (repr. in STORM 1880, 255-64)[short passio, miracles 1-2].

•

Breviarium Nidrosiense (Nidaros), Paris 1519, fols. qq II-rr IIII(repr. in TORFÆUS 1711, LANGEBEK 1773 & STORM 1880, 229-45),[extended short passio, miracles 1-3, 6-10, 19, 15, 20, 23, 4, 12,14].

•

Breviarium Arhusiense, Århus 1519 (repr. in STORM 1880, 247-51)[short passio, miracles 1,2,4].

•

Officia propria ss. patronorum Regni Sueciæ, Antwerpen 1616 (andseveral reprints) [short passio, miracle 1].

•

TORFÆUS, T. 1711: Historia rerum Norvegicarum, Copenhagen, vol. 3,211-13 [reprint of the BN text].

•

Acta Sanctorum, Antwerpen 1731, Julii Tomus VII, 87-120: ?De S.Olavo, rege et martyre, Nidrosiæ in Norvegia CommentariusHistoricus?. [excerpts from medieval and early modern historiographywith discussions; also includes brief quotations from a lost Utrechtmanuscript. The pages 113-16 prints the text, subsequently lost, fromthe late medieval legendarium, Codex Bodecensis, under the title?Acta brevia auctore anonymo, ex passionali pergameno ms. c?nobiiBodecensis?, which includes an A version of the passio with miracles1,2,6,7,8,19,20,3,5. Additional material from BN is quoted viaTORFÆUS 1711, 117-20.]

•

LANGEBEK, J. 1773: SRD 2, Copenhagen, 529-52: ?Legendæ aliquot deSancto Olavo Rege Norvegiæ? [edition of various fragments andtranscriptions in Arne Magnusson?s collection, a reprint of the LowGerman translation and the BN text]

•

Officia propria ss. patronorum Regni Poloniæ et Sueciæ, Mechlen 1858(repr. in STORM 1880, 264-65) [short passio, miracle 1].

•

STORM, G. 1880: ?Acta sancti Olavi regis et martyris,? in MHN,Kristiania 1880, 125-44 [an eclectic A text based mainly on BN andActa sanctorum, but ordered with the Old Norse homily as structuralguideline].

•

? METCALFE, F. 1881: Passio et Miracula Beati Olaui, edited from atwelfth-century manuscript in the library of Corpus Christi College,Oxford, with an introduction and notes by F. M., Oxford [firstedition of the full A version, the Fountains abbey text].

•

? STORM, G. 1885: Om en Olavslegende fra Ribe, (ChristianiaVidensk.-Selsk. Forhandl. 3), Kristiania. [A partial first edition ofE, the ?Ribe?-legend, ca. 1460/65].

•

? MALIN 1920 [first edition of the Miles Britannicus-miracle from athirteenth-century fragment].

•

? ØSTREM 2000 [first edition of C, based on thirteenth-centurybreviary fragments, Stockholm, Riksarkivet, Fr. 596 & 614 (togetheralso called codex 97) ? see also ØSTREM 2001]

•

? ØSTREM 2001 [appendix 2, pp. 263-280, ?Lessons from Passio Olavi?:the long passio (A) based on Storm 1880, the short passio (B) andmiracles 1-11 based on the Anchin manuscript, all with copiousadditional readings from a number of liturgical manuscript fragments.Appendix 5, pp. 288-91 reprints the edition of the C version fromØstrem 2000].

•

Translations

For medieval translations see Medieval transmission and reception.

SKARD, E. 1930: Passio Olavi. Lidingssoga og undergjerningane åt denheilage Olaf, (Norrøne bokværk 46) Oslo (repr. 1970). [Norwegian,nynorsk, from STORM?s edition, with additions and transpositions].

•

LUDWIG 1994 ##-## [English, selections from METCALFE?s edition(version A)]

•

PHELPSTEAD, C. (ed.) 2001: A History of Norway and The Passion andMiracles of the Blessed Óláfr, translated by D. Kunin, ed. withintroduction and notes by C. Phelpstead (Viking Society for NorthernResearch Text Series, vol. 13), London [from METCALFE?s edition(version A)].

•

IVERSEN, G. (transl.) in LIDÉN 1999, 404-10 [Swedish, from STORM 1885(version E)].

•

EKREM, I. 2000, 145-46 [Norwegian, bokmål, the short Passio fromversion B].

•

ØSTREM 2000, 192-97 [Norwegian, bokmål, from his own edition ibid.(version C)].

•

ØSTREM 2001, ##-##. [English, from his own edition ibid. (versionC)].

•

Commentaries

METCALFE 1881 [literary and historical footnotes for the entiretext].

•

SKARD 1930.• KRAGGERUD 1993, 130-44.• PHELPSTEAD 2001, ##-##.•

Date and place

There can be no doubt that the legend of St. Olaf went through a formativephase shortly after the establishment of the archbishopric in Trondheim in1153, and in particular during the period when Eystein Erlendsson was inoffice (1161-1188). Our earliest extant manuscripts of both the legend andthe chants and lectiones derived from it, stem from the end of the twelfthcentury, and a number of miracles date and place themselves in Trondheimafter 1153 and some even explicitly during the reign of Eystein. This datealso tallies well with a number of significant textual and musicalcompositions for the liturgy of St. Olaf (see below), and with thecontemporary organisation of pilgrimage on a larger scale.

Furthermore the historian Theodoricus Monachus, who was a probably a canonat the cathedral in this very period and certainly a well-informed local

who dedicated his work to Eystein sometime between the years 1177 and1188, writes in ch. 20:

Quomodo vero mox omnipotens Deus merita martyris sui Olavi declaraveritcæcis visum reddendo et multa commoda ægris mortalibus impendendo, etqualiter episcopus Grimkel ? qui fuit filius fratris Sigwardi episcopi,quem Olavus filius Tryggva secum adduxerat de Anglia - post annum etquinque dies beatum corpus e terra levaverit et in loco decenter ornatoreposuerit in Nidrosiensi metropoli, quo statim peracta pugna transvectumfuerat, quia hæc omnia a nonnullis memoriæ tradita sunt, nos notisimmorari superfluum duximus.

(It has been related by several how almighty God soon made known themerits of his martyr Óláfr, by restoring sight to the blind and bestowingmanifold comforts on the infirm; and how, after a year and five days.Bishop Grímkell (who was the nephew of bishop Sigeweard, whom ÓláfrTryggvason had brought with him from England) had Óláfr?s body exhumed andlaid in a fitly adorned place in the metropolitan city of Nidaróss, whereit had been conveyed immediately after the battle was finished. Butbecause all these things have been recorded by several, I regard it asunnecessary to dwell on matters which are already known.) (transl.MCDOUGALL & MCDOUGALL 1998, 32-33).

Although this passage has given rise to a number of discussions (furtherreferences in MCDOUGALL & MCDOUGALL 1998, 32-33) it is safe to infer thatTheodoricus knew of writings (?memoriæ tradita sunt?) about some of Olaf?sposthumous miracles and about the translation of Olaf?s body to Trondheim? and that he expected his primary audience to know about such texts. Allother traces of a translation text has disappeared, but the miracles mustat least be some of those we know from the legend, or even simplyidentical to a certain group of them. ØSTREM 2001, 34-35, has questionedSTORM?s hypothesis (1880, XXXIV) that Theodoricus is here speaking of alost Translatio S. Olavi. Others have extended his doubts (e.g. CHASE2005, 12) with the resulting interpretation that Theodoricus?s testimonysimply shows that the events were known. But although ØSTREM is correct insaying that we cannot take for granted that Theodoricus is referring to aliturgical text, we have to acknowledge that he is referring to specificwritings existing at the cathedral in Trondheim. ?Memoriae tradere? isstandard classical and medieval Latin for putting into writing, and itwould need other indicators and a lot of good will to make it refer to,for instance, (unwritten) skaldic verse. That Theodoricus is not talkingvaguely of knowledge floating around in common memory is underlined by thephrase ?a nonnullis?, i.e. writings by certain people. He may or may nothave known who the authors were, but his entire point is to say that whatyou do not find in this book you will find in others (almost certainly,Latin books here at the cathedral). Leaving aside the question of theTranslatio, for the present purpose it is sufficient so far to establishthat Theodoricus presumed that it would be straightforward for hisreaders/listeners around 1180 to find one or more written accounts of anumber of Olaf?s posthumous healing miracles.

STORM 1880 and SKARD 1932 were convinced that Theodoricus also knew thePassio, i.e. the vita-part of the legend more or less as we have it in itslong version. Their textual arguments are not particularly strong andtheir view has since become muddled by a number of factors. First,METCALFE?s discovery of the fullest version (A) of the legend in 1881 withsome of its additional miracles penned by Eystein led to an assumptionthat the entire legend came from his hand (and, consequently, must havebeen at least contemporary with Theodoricus, if not later). The stylisticinvestigation by SKARD 1932 allegedly proved unitary authorship by thearchbishop ? a position that has been accepted by most leading scholars

since, for instance by HOLTSMARK 1937 and GUNNES 1996 although bothbelieved that some sort of written account did exist before 1153 and wasused by Eystein acting as redactor. The unitary style which SKARD hadsuggested, however, was difficult to uphold, both because what seemed tohim stylistic idiosyncrasies are now known to be standard medievalisms,and because a number of other traits in the text point to more to amultilayered composition than unitary composition or redaction (cf. EKREM2000 & MORTENSEN 2000a, MORTENSEN & MUNDAL 2003, and see Summary ofcontents below). A particularly intriguing passage in Theodoricuscomplicates matters further. He presents as his personal finding (andthere is no reason to doubt this) that Olaf was baptized in Rouen: thiscan be learnt from the Norman chronicler, William of Jumièges (ca. 1070,book 5, ch. 11-12). The Passio takes this information for granted and itwould therefore seem to postdate Theodoricus (for a full discussion ofthis see MORTENSEN 2000b). It has also been shown that the short vita(evidenced before ca. 1200 in the Douai manuscript, version B above) ? bysome scholars believed to have been a first version ? is in fact anabbreviation of the long vita (ØSTREM 2001, 45 ff., MORTENSEN & MUNDAL2003, 366). Finally ANTONSSON 2004a has pointed to a convincing motifparallel (see Sources below) with the legend of Thomas Becket which givesa terminus post quem of 1173. All this certainly point to the 1170s and1180s as the crucial period for the composition of the long vita. Insteadof focusing on Eystein alone, it is probably safer to talk of a teameffort by the senior clergy at the Trondheim cathedral (cf. Theodoricus?sshare in discovering evidence for Olaf?s baptism, see also Composition andstyle below).

While we can be certain that the Passio is a late twelfth-centuryTrondheim composition, and that the entire legend, including the miracles,must have been put together in a form like A at the same time and place,this does not preclude the possibility that a first series of miracleswere taken down at an earlier stage, before Eystein, and probably alsobefore 1153 (for the various groupings of miracles, see below Summary andComposition). There is a good amount of evidence for this. Theodoricus?sstatement quoted above implies that he knew written accounts of a numberof miracles (and of the translation), but not of a passio. At thebeginning of miracle 37 Archbishop Eystein writes:

Perlectis his, que de uita et miraculis beati Olaui nobis antiquitascommendauit, congruum estimamus a nobis quoque, qui eius presentialiternouis passim illustramur miraculis, que ipsi uidimus aut ueratium uirorumtestimoniis uirtuose ad eius gloriam adeo facta probauimus, futurisgenerationibus memoranda litteris assignari.

(Having read all those accounts which antiquity has entrusted to usconcerning the life and miracles of the blessed Óláfr, we deem it fittingthat we, who have been personally enlightened by his widespread miraclesin our own day, should also commit to the attention of future generations,in writing, those things which have been performed by miraculous powers,to his greater glory, as we have seen for ourselves or have learnt fromthe testimony of truthful men.)

Eystein?s reference to antiquitas here is somewhat puzzling because it wasclear to him that both the vita and most of the miracles were taken downafter 1153. But he may think of the oldest core of miracles (see belowSummary) at the beginning of the book which radiated ?antiquity? ? or hemay have known for a fact that the collection of miracle reports hadindeed been initiated before 1153.

The strongest indication that a written tradition of old miracles wasavailable before 1153 is the Old Norse stanzaic poem Geisli (Sunbeam)

composed on commission by the poet Einar Skúlason for the festivities atthe establishment of the archdiocese in 1153. In Geisli eight of the firstnine miracles of the Latin collections are describes in a poeticrephrasing (cf. HOLTSMARK 1937, PHELPSTEAD 2001, XXXII & CHASE 2005).Usually this is taken as evidence that the vernacular poet was drawing onLatin writing or stories told on the basis of a Latin text (EKREM 2000,PHELPSTEAD 2001, MORTENSEN & MUNDAL 2003). It is correctly pointed out byCHASE (2005, 13) that we cannot be certain that the influence does not runthe other way (as long as we do not possess a pre-1150 fragment containingLatin miracles), but probability, I think, speaks against it. It is awidely well-attested practice in the eleventh and twelfth centuries totake down miracle reports at the main shrine in Latin rather than in thevernacular, and in this case it is difficult to see how the Latin shouldhave been extracted from a highly specialized poetic discourse. Somedetails of authentication have also been left out by the poet, such as thepresence of votive gifts in the church stemming from miracle 4 and 5 (cf.Geisli, stanzas 51-56 & 35-36). As these miracle report seem to haveserved as an explanation of the votive gifts it would be more difficult tointerpret the authentication as an addition to the Latin text than assomething left out through poetic treatment. More analysis drawing on theentire miracle corpus in Latin and Old Norse is needed, but I am inclinedto agree with the widely held view that a small collection of Latinmiracle reports was already available in Trondheim before 1153 (cf.HOLTSMARK 1937, GUNNES 1996, 178-79, EKREM 2000, PHELPSTEAD 2001, XXXVIII)? although it is difficult to say when it was taken down. One possibilityis the active period of building and ?positioning? in the 1130s and 1140s,but at the present stage of research there is no clear indication that itcould not be as old as around 1100.

Apart from this possible group of pre-1153 core miracles (1-10) theremainder of the miracle collection as we know it in version A consists ofvarious layers composed between 1153 and 1188 (death of Eystein who pennedsome of the last miracles) or ca. 1200 (latest palaeographical date of theFountains Abbey manuscript.) The Summary below gives some additionalinternal evidence for this time frame.

Version B is contemporary with A and strongly related to it (see Summarybelow). Version C in all probability stems from Sweden, perhaps from thediocese of Linköping where it could have been composed around 1200 (ØSTREM2000 & 2001).

D and E are both late medieval texts (ca. 1460) composed outside ofNorway, D is known through the legendary put together by Herman Greven inKöln 1460 ? it is probably of German origin as it reflects the world ofHanseatic traders and was immediately translated into Low German. E isknown through the work of Petrus Mathie in Ribe in southern Denmark (ca.1460-1465), and is related to D in narrative and motifs.

Summary of contents

Version A: Passio: The long Passio begins by a lofty summary of the roleof Olaf as the ruler who converted the cold North. It includes a number ofbiblical quotations where this deed is foreshadowed, and Olaf is hinted at? he is for instance the ?boiling pot? (olla) mentioned by Jeremiah. Therest of the Passio is structured chronologically from the time he wasbaptized in Rouen. He was the perfect ruler, a rex justus, who spread theword of God, uprooted paganism, and kept justice by his own humble exampleand by restraining the proud. But his efforts was not welcomed by everyoneand due to rising pressure he went into exile in Russia to await a bettertime to carry through God?s plan. After a while he felt ready to return,also to suffer martyrdom if that was God?s will. His adversaries gathered

to meet him, partly bribed by his enemy ?a certain Canute? [the Great],partly through their own ambition and reluctance to accept Christianity.Olaf faced death bravely with his eyes fixed on eternal life and wasstruck down at Stiklestad [north of Trondheim] on Wednesday July 29, 1028[according to this version].

Miracles: In this version 49 miracles are collected which can be dividedin four major series: 1-10, 11-21, 22-36, 37-49. For discussion ofpossible divisions see HOLTSMARK 1937, GUNNES 1996, 178-88, EKREM 2000,JØRGENSEN 2000, MUNDAL & MORTENSEN 2003. The present division, and othersthat have been proposed, owes as much to the transmission of miracles inother versions as to an analysis of formalities, style and contents ? adistinction that has not yet been systematically applied. In terms ofcontent the first series stand out in several respects: it includes twomiracles which happened in Olaf?s lifetime (1 & 10, all other miracles areposthumous); three miracles (3-5) end with a reference to the votive giftwhich can be seen in the martyr?s church now (hec ecclesia). There are noreferences to archbishop or arch see. Number 10, which deals with Olaf?sself-inflicted punishment of his transgression against the rule of restingon a Sunday, is introduced by an editorial voice explaining that althoughthis miracle comes last, it should really have been put first in terms ofchronology. No. 2 narrates the ?protomiracle?, the first healing worked bythe saint on the day after his death. 3-5 and 9 report stories of miraclesoutside of Norway through prayers to Olaf, and 6-8 of healings of peoplewho attended the memoria of the saint, i.a. the feast of 29 July. Thesemiracles (with or without no. 10) are also usually grouped togetherbecause the Old Norse poem Geisli from 1153 (see above) reports all themiracles here except 8 and 10 and none from any subsequent series.

The beginning of the next series, 11-21, is marked by the reference to the?archbishop and the brothers? at the end of 11 (... archiepiscopo etfratribus exposuit) ? the brothers no doubt referring to the regularcanons of the Trondheim cahtedral. Miracle 19 is explicitly dated to theyear when Olaf?s church in Trondheim received the pallium. The majority ofthese miracles are healings, but two deal with escape from fire and onewith a boy lost and found (!). The feast and shrine in Trondheim againdominate, but there are two miracles reported from the Norwegian communityin Novgorod and two from the province of Telemark. No. 21 deals with thehealing of an unnamed Norwegian king at Olaf?s local church in Stiklestad,but there is no textual break between 21 and 22, in fact 22 begins bysaying ?in the same year...?. The reason that scholars have put a caesurahere is because the miracles 1-21 are transmitted together in a number ofother manuscripts and vernacular texts. With one small exception (part ofmiracle 23 in the Breviarium Nidrosiense from 1519), miracles 22-49 areonly known from version A ? the Fountains abbey manuscript. The Anchinmanuscript (see below version B) stops after miracle 21 and so does theOld Norse Homiliary version from ca. 1200. The vernacular Legendary sagaof Olaf from the beginning of the thirteenth century also confines itselfto the first 21 miracles, and a fragment from the thirteenth century withOld Norse adaptations of Olaf miracles contain pieces only within thisrange as well (cf. JØRGENSEN 2000).

The third series, 22-36, is equally dominated by healings at the shrine(mostly in connection with the celebrations on 29 July). Occasional?distance? miracles are also reported where the person(s) favoured througha vow to Olaf present themselves in Trondheim to pay homage to the saint.An authenticating voice is often present ? it is a ?we? who receives giftsfor the church or who have heard the story from so and so. In two miracles(26 & 30) the ?we? addresses themselves to a caritati uestre, probably thearchbishop. In no. 34 we are informed that a gift was sent ?to us while wewere in Bergen?; it is most natural to take this as pluralis maiestatis,

hence it is possible that the author here is archbishop Eystein, althoughit could be another senior official. Miracle 35 tells of an opening of theshrine (the miracle is the sweet fragrance) and is also interestingbecause it begins with a date ?some time during the reign of King Eystein...?; this means that this miracle must have been taken down after EysteinHaraldson?s death in 1157. Some miracles are dated relatively ?the sameyear? or ?next winter?. There is no explicit conclusion of this series,but the next one begins with a clear break.

The fourth and last series, 37-49, is opened by the title ?TractatusAugustini Norewagensis episcopi etc? (for Eystein?s opening words aboutadding to the miracles, see above Date and Place). In miracle 37 Eysteintells vividly of a miraculously healed injury he suffered duringinspection of the construction of the new basilica. It is not clearwhether ?tractatus? is the title for miracle 37 alone or for all theremaining ones, but as they have titles of their own the first alternativeis preferable. His voice is not as explicit in other miracles, but canprobably be discerned in 38, 39 (?we were held up by ecclesiasticalbusiness? ecclesiasticis detinebamur negociis) and 44, as well as in 47and 49 where the authorial voice suddenly addresses itself to fratresdilectissimi, the canons of the chapter. This might lead to the conclusionthat the entire last series is authored by Eystein, but in 42 we suddenlymeet the caritas again as addressee as in 26 and 30. Most of the miraclesare healings at the shrine ? as in the other series. In 49 we get aninteresting piece of information on the organisation of healings, namelythe mention of a hospital for pilgrims.

One preliminary conclusion to be drawn about version A is that neitherEystein or any other redactor were interested in smoothing over the seamsbetween miracles or groups of miracles in this version ? they were meantto stand with their pointers in different directions, perhaps also becausethey then kept an air of authenticity, but perhaps simply because theyreflect an accepted way of accumulating reports with different authorialvoices. These voices, in turn, all view things in a cathedral perspective,so the question of authorship can perhaps be resolved by pointing to acollective of senior officials at Olaf?s church.

Version B Passio: In this version the Passio has been telescoped into lessthan a page. Some scholars have viewed the A version as an elaborated Bversion whereas others think that B must be an abbreviation of A (see,with further references, EKREM 2000 & ØSTREM 2001). The present author isof the opinion that the issue can be settled by internal textual argumentsin favour of B being an abbreviation (argued in MORTENSEN & MUNDAL 2003,366).

Miracula: The B version includes, in that order, miracles 1-9, 50, 10-21 ?no. 50 being the only one not in the A version. It deals with an Englishknight who (successfully) seeks help in Trondheim on Olaf?s feast day.There are no specificities about time nor does the authorial voice giveitself away. Miracles 1,4,5,9 and 10 are missing some passages incomparison with version A, but in nos. 11-21 there are no editorialdifferences (cf. EKREM 2000, 124). After miracle 21 there is an epilogueformula which is similar to the one introducing miracle 26 in version A.

Version C This alternative Passio was first identified and edited byØSTREM 2000 & 2001 in a fragment from the National Archives of Sweden(cod. 97). It consists of 9 lessons, of which 1, 4, and most of 5 havebeen lost. It follows the same basic structure as version A with adepiction of Olaf?s piety, just rule and protection of the poor, hisconflict with his adversaries, his exile in Russia and his return tomartyrdom. But it is nevertheless a completely different text which does

not seem to draw directly on A. The plot and the rhetoric are similar, butother scriptural references and etymologies are employed (Stiklestad aslocus pugionum uel sicariorum). The most salient feature, in comparisonwith A and B, is the more important role allotted to King Canute as leaderof Olaf?s enemies and instigator of evil.

Version D This late medieval adaptation follows version A closely forabout the first half of the text, but then introduces completely newelements such as Olaf?s rivalry with a pagan brother and the popular storyof Olaf sailing through a mountain. Most striking is the description ofOlaf?s martyrdom during which he is crucified. On the cross Olaf prays formerchants who call for his help on the dangerous seas.

Version E The other late medieval legend adds a romantic novella aboutOlaf?s father Harald?s adventures during a pilgrimage to Santiago deCompostella and makes the theme about the pagan brother into a mainvehicle for the whole plot.

Composition and style

The only existing investigation of stylistic matters is that done by SKARD1932 (the A version). Many of his individual observations are stillvaluable, but his main conclusion ? that the A text has a unitary styleattributable to Eystein as the sole author/redactor ? has been challenged.OEHLER (1970, 63 n. 23) put his finger on the soft spots of SKARD?sprocedure: (1) the examples are not drawn systematically from all theparts of the text whose unity he wants to demonstrate. (2) Most of thestylistic idiosyncracies SKARD finds are ordinary medievalisms. In spiteof this ? and indeed in spite of Eystein?s explicit statement at thebeginning of miracle 37 that he wants to add to a text transmitted fromantiquity ? Eystein?s role as author of the whole legend (in version A)has remained uncontested in Norwegian scholarship until recently (e.g.SKARD 1930-1933, HOLTSMARK 1937, GUNNES 1996; the exception is BULL 1924).For fuller references to the debate and its present status see MORTENSEN2000, 101-3, EKREM 2000, 138-39, PHELPSTEAD 2001, XXXVI-XXXIX, MORTENSEN &MUNDAL 2003, 363-68.

What is still wanting is a modern stylistic analysis (including probingsinto the prose rhythm) which characterizes the various parts of the workirrespective of the author issue. This cannot be offered here, but just toillustrate the diversity within the A version, consider the followingthree passages. The first is about the success of Olaf?s mission from thepassio (ed. METCALFE 1881, 70), the next is from miracle 20 (ibid. 93) andthe third from miracle 37 (ibid. 104) ? one of the pieces certainlywritten by Eystein (in a few cases METCALFE?s text is adjusted; thetranslation is by P. Fisher [not yet published]):

Plurimum profecit in breui, et innumerabilem Domino multitudinemadquisiuit. Confluebant ad baptisma certatim populi, et numerus credentiumaugebatur in dies. Effringebantur statue, succidebantur luci, euertebanturdelubra, ordinabantur sacerdotes, et fabricabantur ecclesie. Offerebantdonaria populi cum deuocione et alacritate. Erubescebant ydolorumcultores, confundebantur qui confidebant in scultili, et in multis illiusregionis partibus infidelium depressa multitudine mutire non audens omnisiniquitas opilabat os suum.

(In a short time he made excellent progress, procuring a countless hostfor the Lord. In eager droves they flocked to be baptized, and the numberof believers swelled daily. The effigies were shattered, the groves hewndown and the shrines overthrown. Priests were ordained, churches built.The people brought votive offerings piously and promptly. Those who

worshipped idols blushed with shame, those who relied firmly on a gravenimage were thrown into confusion, and in many areas of that region thecrowd of unbelievers were quelled, with the result that, not daring tomutter a sound, all iniquity stopped her mouth.)

Waringus quidam in Ruscia seruum emerat, bone indolis iuuenem, set mutum.Qui cum nichil de se ipse profiteri posset, cuius gentis essetignorabatur. Ars tamen, qua erat instructus, inter waringos eumconuersatum fuisse prodebat: nam arma, quibus illi soli utuntur, fabricarenouerat. Hic, cum diu ex uenditione diuersa probasset dominia, admercatorem postmodum deuenit, qui ei pietatis intuitu iugum laxauitseruile.

(A certain Varangian had bought a slave in Russia, a young man of finenatural qualities, but dumb. Consequently he could make no declarationabout himself and therefore people were ignorant of his race. However, thecraftsmanship he was versed in showed that he had lived among theVarangians, for he knew how to forge the kind of armour that they alonewore. When he had passed by sale from one master to another, he eventuallycame into the hands of a merchant, who on compassionate grounds loosed himfrom the yoke of slavery).

Ego itaque Augustinus per uoluntatem dei in ecclesia beati martiris Olauiepiscopalem ad tempus sollicitudinem gerens, cum a magistro, qui operariisecclesie preest, pro quibusdam in opere disponendis super muri fastigiumeuocarer, pons, in quo lapides trahebantur, multitudinis, que nossequebatur, molem non ferens confractus cecidit. Peccatis autemexigentibus ut uite et iniuncte sollicitudinis cautior redderer, ceterisponti et machinis adherentibus solus in precipicium feror.

(And so, when I, Eystein, was at that time, by God?s wish, bearing theresponsibility of archbishop in the church of the blessed martyr Olaf, Iwas called out to the top of the wall by the foreman in charge of thoselabouring on the church, so that I might settle certain details of thework; but the gangplank along which the stone was being hauled could notbear the weight of all the people following us up, so that it shatteredand collapsed. With my sins demanding that I should make myself be rathercareful of my life and the responsibility imposed on me, while the restwere clinging to the gangplank and scaffolding I alone fell headlong.)

The first sample is effectively built by one perfect (profecit) followedby a number of emphatically foregrounded imperfects depicting the movementof conversion (confluebant, effringebantur etc.) which, in spite of thelack of concreteness, conjures up images of the process. The language issteeped in biblical phrases referring to conversion and paganism: numeruscredentium augebatur could echo Act. 5.14 magis autem augebatur credentiumin Domino multitudo virorum ac mulierum, the effigies and the groves nodoubt come out of Josias?s uprooting of idolatry in 4. Reg. 23.14 etcontrivit statuas et succidit lucos. The pun on confundo and confido isfrom Is. 42.17 confundantur confusione qui confidunt in sculptili, andfinally the recherché phrase about iniquity brought to silence is borrowedfrom Ps. 106.42: et omnis iniquitas oppilabat os suum.

The second example shows a straightforward novelistic miracle account,paratactic and without any biblical or poetic embellishment. The onlyexertion in that direction, it seems, is the modest hyperbaton at the endof the quotation, iugum laxauit seruile. This paratactic style is typicalof many of the shorter miracles ? a sort of reportatio or protocolmatter-of-fact style. The third example, in contrast, is extremelyhypotactic with a very substantial postponement of the main element pons.... cecidit. The opening absolute ablative of the second clause, peccatis

exigentibus, is a twelfth-century favourite in explaining setbacks for thegood cause, frequently used in crusading historiography whenever theChristian army loses to the infidel.

Sources

The literary and hagiographical background of the Legend ? and here thelong Passio (version A) is the most relevant object of study ? has notbeen investigated systematically. It is almost certain that one motif (ofthe cold North heated by the calor fidei) is borrowed from Ælnoth?s legendof Sanctus Kanutus rex (cf. SKÅNLAND 1956) and influences from Hugh of StVictor?s De sacramentis has also been traced in the way Olaf is describedas rex justus (GUNNES 1996, 213-14). In general it has been assumed thatthe author of Passio Olaui used English hagiographical models fordescribing a martyr king (cf. HOFFMANN 1975, PHELPSTEAD 2001, XLIII); mostpertinent here are probably the widespread Abbo?s Life of Edmund (d. 869,Passio written 985-987) and perhaps the anonymous Life of Edward Martyr(d. 978, Passio written ca. 1100), but no striking verbal parallels haveso far been demonstrated. The Legend(s) of Thomas Becket (d. 1170) hasalso been drawn into the picture on account of strong similarities in themotif of premeditated flight and exile as a necessary preparation ofmartyrdom (ANTONSSON 2004a).

Purpose and audience

The Passio (version A) was composed during the archbishopric of Eystein,probably around 1180, and should be seen as part of the textual andliturgical initiatives to which also Theodoricus? History and the Officeand Sequences of Olaf belong. The Passio provided the the textual backbonefor the new liturgy. Most of the miracles were also taken down at theshrine in this same period which was characterized by building activityand organization of pilgrimage on a larger scale. A miracle protocolserved a double purpose of divine and human bookkeeping ? Olaf?smiraculous deeds had to be inscribed into the book of God as well as todocument his powers for pilgrims. It would seem that a protocol hadexisted in an early version before 1153, but it is certain that it waskept assiduously during the reign of Eystein. After that it does not seemto have been updated anymore. Version B is an example of a contemporarycondensed text with basically the same purpose as A; many other suchextracts and condensations were made (see below transmission) mainly forliturgical purposes. In addition we possess in C an alternative vita,probably made for a specific Swedish liturgy; again many such variants mayhave existed.

The particular circumstances around versions D and E have not beenstudied, but they were hardly written for a Norwegian audience, but ratherfor Northern German and Danish merchant communities around 1460.

Medieval reception and transmission

As is already clear from the above the Legend of St Olaf became a verywide spread text in the Nordic Middle Ages. Many brief versions forliturgical readings surface in the early printed breviaria from Norway,Sweden, Denmark, and northern Germany and thus reflect a steady manuscripttransmission from the twelfth to fifteenth centuries. Of these liturgicalcodices a considerable number of pertinent fragments have been identified(see especially ØSTREM 2001) which corroborates a spread through theNordic dioceses already from the early thirteenth century. The Latin text? again in various versions ? were also translated into Old Norse (ca.1200, Gamal norsk homiliebok, ed. G. Indrebø, Oslo 1931), Old Swedish(fourteenth cent., ed. ##) and Low German (Lübeck 1492 (1499, 1505):

Passionael efte Dat Levent der Hyllighen) and it played an important rolefor part of the Saga literature on King Olaf in the thirteenth century. Itis thus a testimony to the dramatic library history of the NordicReformations that the important manuscript textual witnesses to the fulllegend ? as typically copied in legendaries ? survive only in foreigncodices, namely English (A) and French (B). A large number of similartexts must have been around locally, especially in Norway. The mainmanuscripts for versions A-E are:

(A) Oxford, Corpus Christi College 209, fols. 57r-90r; FountainsAbbey (Cistercian), Yorkshire, last quarter of the twelfth century.Version A: long passio, miracles 1-49, unique witness to miracles22-49.

•

Oxford, Bodleian Library, Rawlinson C 440, fols. 187v-194r; English,probably Cistercian from Yorkshire, second quarter of the thirteenthcentury. Version A: long passio, miracles 1-11, 50 (some now lost due tomutilation). Dresden, Sächsisches Landesbibliothek cod. A 182, fols.172-177; Liber Laurentii Odonis, Sweden (Linköping?), ca. 1400. Version A:long passio, miracles 1-5 #.

(B) Douai, Bibliothèque municipale, 295, fols. 94r-108v; Anchin(Benedictine), Northern France, last quarter of the twelfth century.Version B: short passio, miracles 1-9, 50, 10-21.

•

Wiener-Neustadt, Neukloster XII. D 21, ##; Bordesholm (Augustiniancanons), Holstein, 1512. Version B: short passio, miracles 1-10, 50, 13-14#].

(C) Stockholm, National Archives, Fr. 596/614 (cod. 97#); Swedish,second half of the thirteenth century. Unique (fragmentary) witnessto version C.

•

(D) Berlin, Staatsbibliothek - Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Theol. lat.fol. 706, ff. 168r-169v [Köln 1460, by Hermann Greven. Version D].

•

(E) Copenhagen, The Arnamagnæan Collection, AM #### [Ribe 1460-1465,by Petrus Mathe. Version E].

•

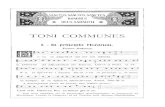

OfficiumThe most important part of a saint?s liturgy such as St. Olaf?s, inaddition to the legend, is the approximately 35 chants that were sungduring the canonical hours: Vespers, Matins and Lauds. As was customary,they are closely linked to the legend. The antiphons of Vespers aregeneral invocations, but most of the chants for Matins are taken straightfrom the legend text, with only slight adaptations. The antiphons forLauds are short summaries of some of the miracles.

The printed Breviarium Nidrosiense (1519) also contains a few chants thatstem from the oldest layer of liturgical celebration of St Olaf, theoffice in the Leofric Collectar from ca. 1060. This office was probablycompiled by Grimkell, Olaf?s own missionary bishop and the one whocanonized Olaf in 1031 (see BIRKELI 1980, JOHNSEN 1975, and ØSTREM 2001).The melodies of the chants consistently employ a small set of fixed,standardized formulae, and they have been described by one scholar as?rather dull and uninspired? (HUGHES 1993, 409).

Metre/rhythm

Most of the chant texts in the office of St. Olaf are in prose, and not inthe style of the rhymed office with metrical and rhymed texts, which wasthe dominating style for this kind of saint?s office from the eleventh

century onwards. Only the hymns, the antiphon for the Magnificat Adestdies letitie, and some of the early antiphons which go back to the Leofriccollectar are in verse. The hymns are all trochaic septenarii (3 x [8p +7pp]), except the asclepiadic O quam glorifica (4 x [6 + 5p]). Adest diesletitie is in iambic dimeters (8pp), and the early antiphons are inhexameters or elegiac couplets.

Size

A full liturgical office such as the feast of St. Olaf consists of sixantiphons, a responsory, and a hymn for Vespers; the same for Lauds; tenantiphons, nine responsories, and a hymn for Matins; and one antiphon forMagnificat at the second Vespers, a total of ca. 35 chants. In addition tothis come short chapter lessons, prayers, versicles, etc. at each of thehours.

Editions

Breviarium Nidrosiense, Paris 1519 (Facsimile edition by Børsumsforlag, Oslo 1964).

•

? STORM, G. 1880: Monumenta historica Norvegiae, 229?282, Christiania[Oslo].

•

REISS, G. 1912: Musiken ved den middelalderlige Olavsdyrkelse iNorden (Videnskabsselskabets skrifter, II. Hist.-Filos. Klasse, 1911no. 5), Christiania [Oslo].

•

DESWICK, E.S. & FRERE, W.H. 1914-1921: The Leofric Collectar, London.• ? ØSTREM, E. 2001: The Office of St Olaf. A Study in ChantTransmission, Uppsala.

•

Date and place

As with the Legend, which is the textual point of departure for theOffice, there is no reason to assume that the Office should have beenwritten anywhere but in Trondheim, and it is equally probable that itstems from the concerted effort of senior clerics during the reign ofEystein or shortly thereafter. The earliest manuscripts (or fragments)that contain the Office can be dated to the decades around 1200. Theterminus post quem is more difficult to determine. Several manuscriptshave been preserved which lack a proper St. Olaf?s office, but whereOlaf?s name is mentioned in the collect prayer for the saints who werepreviously celebrated on that day (e.g. ?Presta quesumus omnipotens deusut sicut populus christianus martyrum tuorum felicis simplicii faustinibeatricis atque olaui temporali sollemnitate congaudet?, from S-Skam Br250). All the sources of this type are from the middle or the end of thetwelfth century, and none of them is younger than the oldest source withthe complete Office. This may be taken as an indication that no officeexisted when these older books were produced, i.e. roughly the thirdquarter of the twelfth century. All in all this strengthens the hypothesisthat the Office was composed during Eystein Erlendsson?s episcopacy(1161-1188), either by him or under his supervision. If the above argumentabout Theodoricus is accepted (see Legend), this means that the Office inits known form can hardly have been in place before 1180.

Summary of contents

The antiphons of Vespers, which begin the Office, are all invocations ofthe kind: Sancte martyr domini Olave, pro nobis quesumus apud deumintercede (Holy martyr of the Lord, Olaf, we beg you to intercede for usbefore God) (first antiphon of Vespers).

The nine antiphons of Matins are all taken from the beginning of theLegend. The first two antiphons briefly summarize the first section of thePassio which can be described as the ?cosmic view? of the state of affairsat the time of Olaf ? how God looked upon the people of the North and inhis mercy ?founded his city in the eagle?s quarters? (in lateribusaquilonis fundavit civitatem suam) during Olaf?s reign. The rest of theantiphons together with the first responsory contain, sentence bysentence, the entire text of the following section of the Passio (from?Hic evangelice veritatis? to the passage ending ?ad agnitionem etreverentiam sui creatoris reduxit?, which in the last antiphon is changedto ?ad veri dei culturam revocabat?). In this text passage, theperspective is narrowed down, beginning with Olaf?s baptism, thenenumerating his deeds as a Christian ruler: although he was a pagan, hewas benign and honest at heart, always meditating on heavenly things, evenwhen he was involved in the affairs of the kingdom, and, not being contentwith his own salvation, he desired to convert his subjects also.

The purpose of responsories in the office was originally to function ascommentaries to the lessons that preceded them, often in such a way thattaken together they would tell the whole story of the saint. In the Officeof St. Olaf, however, this is hardly the case. The texts for theresponsories show no attempt to present a continuous narrative, as in theantiphons. Rather, they are compilations of passages from different placesin the Passio, in some cases combined with foreign material. Theselections seem to have been made so as to present a condensed version ofthe main contents of the Passio text, where each chant text presents aseparate theme. The first three responsories, which were sung during thefirst Nocturn, are a characterization of the king and his good nature ? apious ruler who despised all earthly glory (R1), who was filled withburning fervour in the face of resistance (R2), and who courageously faceddanger, even in the prospect of death (R3). The responsories of the secondNocturn recount his acts and the fruits they bore: how he wandered amongthe people like an apostle (R4), turning them away from their heathen godsand baptizing them (R5), until eventually the word took root and churcheswere built everywhere (R6). The third Nocturn presents Olaf?s passio inthree glimpses: how he met his enemies (R7), how he saw Jesus in a dream(R8), and how he could finally ?exchange his earthly kingdom for theheavenly? (R9).

The antiphons of Lauds are taken in their entirety from the legend; theyare very condensed summaries of five of the miracles. The antiphon for theMagnificat in the second Vespers again returns to the ?cosmic perspective?of the introduction: Hodie preciosus martyr olavus ab inimicis veritatisoccisus (Today Olaf was slain by enemies of truth).

The hymns (or hymn) that run(s) through the Office as it is preserved inthe Breviarium Nidrosiense follow(s) more or less the same pattern as theantiphons: a short version of the most important parts of the legend,followed by a few miracles.

Literary and musical models

A common way of compiling new offices was to adapt chants from alreadyexisting offices. This is the case also for the chants on the Office of StOlaf, where ca. half of the antiphons have known models of this kind(owing to the lack of a comprehensive reference material for Responsoriesin medieval offices, these have not been studied with any consistency).The gospel antiphons for Vespers, Lauds, and Second Vespers, and theantiphon for the Invitatory of Matins, are based upon correspondingantiphons in the early-twelfth-century Office of St. Augustine; the restof the chants for Vespers can be found in various offices for St. Martin

of Tours, which suggests that they all stem from a single St. Martin?sOffice, even though no such office is known today; and several of theremaining antiphons in the office have models in the office of St.Vincentius. R9 Rex inclytus is based upon a text found in the communesanctorum of York and Durham. The same text is used in offices for severalother martyrs, e.g. Dionysius (cf. BERGSAGEL 1976).

In most of these chants, the borrowing also extends to the chant texts,ranging from the Vespers antiphons, where the entire text except the nameof the saint have been taken over, through the incorporation of an incipitor a key-phrase, as in the chants taken from the Office of St. Augustine,to antiphons where only the melody has been used.

The sources from which the chants have been taken are not insignificant:the Augustine reform movement was a driving force in the early period ofthe Archbishopric of Nidaros; Eystein himself introduced the feast of St.Augustine in Nidaros and latinized his name ?Augustinus?. Likewise, St.Martin had attributes like ?apostle of France?, ?proto-bishop?, patronsaint of monasticism and of the Merovingian kingdom, all of which areclose to the position that Olaf had (or was attempted to be given) in theearly Norwegian church.

For the remaining chants, no direct sources have been found. These chantsare all written in a highly formulaic musical language, where each melodyconsists of a series of repetitions of small melodic cells, completely inconformance with the style of the late twelfth century. Some attentionseems to have been given to the syntactical structure of the texts in theordering of the melodic cells, which may be an indication that they wereindeed assembled in Nidaros, but there may also have been models whichhave not yet been disclosed.

Medieval reception and transmission

The Office of St. Olaf was used for the celebration of the feast of St.Olaf (29 July) in the Nordic countries and throughout the period from theearly thirteenth century up to the Reformation. St. Olaf was celebratedwith a feast of one of the highest ranks throughout most of the Nordiccountries (summum, totum duplex or duplex; the exception is Uppsala,where, mainly for ecclesio-political reasons, it only had the rank ofnovem lectiones). Every church in the region can therefore be assumed tohave had at least one copy of the Office in their liturgical books. Thisprobably makes it the most widely spread text in this handbook.

During the first decades of the sixteenth century the Scandinavianliturgies were revised and codified in printed breviaries. These containthe legend and the chant texts, but they are all without musical notation.Thus, for the music and for the transmission prior to 1500 we have to relyon parchment fragments, mainly from liturgical books, which were used aswrappers around account books in the growing administrations of thesixteenth century, and which have been collected in the National Archives.Due to differences in archival praxis, the extant collections from theDanish area (including Norway and Iceland) are rather small, whereas inthe National Archives of Sweden (Riksarkivet) there are ca. 20 000 suchfragments, mainly bifolia from liturgical books (see BRUNIUS 1993 & 2005(ed.), ABUKHANFUSA 2004, OMMUNDSEN 2006). This gives a total of a littlemore than 100 fragments from the Scandinavian countries that contain partsor all of the Office, with a great predominance of Swedish material.

The transmission is remarkably stable in this material as a whole. A fewvariants, probably connected to specific dioceses, are discernible, e.g. afew texts from the dioceses of Linköping in Sweden have a special

responsory for Vespers (Sancte Olave Christi martyr), and a proper hymn, Oquam glorifica lux hodierna, seems to have been used only in Västerås,also in Sweden. The extant material from Norway is too small to draw anyconclusions concerning local practices.

In addition to the office based on Passio Olavi, there is evidence of asecond office, based on a different legend (see ØSTREM 2000). Even thisoffice can be dated to ca. 1200 or earlier. Of the three textual witnessesto this legend, one has the different legend text, combined with chantsfrom the office based on Passio Olavi, one has the legend text from PassioOlavi combined with chants based on the different legend, and the thirdhas a legend that switches from Passio Olavi to the other legend after thesixth lesson.

MissaTitle

Missa in natalicio beati Olavi regis et martyris (constructed on the basisof the rubric of the Nidaros ordinal), or Missa in solennitate sanctiOlavi regis et martyris (on basis of the rubric of Missale Nidrosiense).The mass could also be referred to with the incipit from the Oratiocollecta in the first part of the mass; ?Deus regum corona? (the Red Bookof Darley, Cambridge, Corpus Christi College, 422), or ?Deus qui es regumomnium corona? (Missale Nidrosiense) (GJERLØW 1968, 124).

Editions

*REISS, G. 1912: Musiken ved den middelalderlige Olavsdyrkelse i Norden,Kristiania, 104-5 (reprint of the text in Missale Nidrosiense. No musicalnotation apart from Alleluia with verse printed on p. 67).

EGGEN, E. 1922: Nyfunnen Olavsmusikk, Serprent or Norsk aarbok(presentation of the liturgical elements with dubious musicalnotation for the chants).

•

GJERLØW, L 1968, Ordo Nidrosiensis Ecclesiae, Oslo, 372-73 (editionof the entries in the Nidaros ordinal. Incipits only).

•

Most of the chants for St. Olaf?s mass can be found in editions of theMissale or Graduale Romanum, like Graduale Romanum (Solesmes 1974) orGraduale Triplex (Solesmes 1979) in the liturgy for the commons (Communiasanctorum elementa).

Date and place

St. Olaf?s mass was probably celebrated already from the mid eleventhcentury, both in Norway and England. The earliest testimony is the RedBook of Darley, from the early 1060s. One may suspect that the personresponsible for putting these liturgical elements together in a mass wasOlaf?s English bishop Grimkell (d. 1047), who seems to have been active inpropagating the cult of Olaf immediately after his death in 1030 (see forinstance ØSTREM 2001, 28-33).

Summary of contents

The mass contains few elements proper to the saint. Still, it is carefullyassembled to fit the celebration of a martyr king. The text ?Posuistidomine super caput eius coronam de lapide pretioso? (Ps. 20, 4: thousettest a crown of pure gold on his head) is sung twice, first as the

gradual between the two readings, then as the offertory. The liturgicalelements are as follows:

Introitus: Gaudeamus omnes in Domino. Ps. Misericordias domini [Ps. 88].Coll. Deus qui es regnum omnium corona. Ep. Justum deduxit [Sap. 10,10-14]. Gr. Posuisti domine. V. Desiderium. Alleluia. Sancte Olave qui incelis vel Alleluia. Letabitur iustus. Seq. Lux illuxit. Ev. Si quis vultpost me venire [Matth. 16, 24-28]. Offert. Posuisti domine. Secr.Inscrutabilem secreti tui. Com. Magna est gloria. Postcom. Vitalis hostieverbi carofacti.

The Missale Nidrosiense gives an alternative to the psalm verse for theintroit (Domine in virtute, Ps. 20) and an alternative to thePostcommunion; Agni celestis.

Sources

The sources for St. Olaf?s mass are the common elements for the saints,mainly the martyrs. The introit Gaudeamus omnes is in the Graduale Romanumalso used for Agatha, Benedict, Mary (the Annunciation and the Assumption)and All saints. The gradual Posuisti with the verse Desiderium is from theCommune martyrum in the Graduale Romanum. So is the Alleluia with theverse Letabitur. The Alleluia with verse Sancte Olave qui in celis letarisis in Missale Nidrosiense found in the Commune unius confessoris (SancteN. qui in celis letaris). The offertorium Posuisti also belongs to theCommune martyrum, while the communion Magna est gloria is in the Communeapostolorum.

Purpose and audience

The rubric in Missale Nidrosiense reads In solennitate sancti Olavi Regiset martyris, referring to the feast celebrated on St. Olaf?s nativitas 29July. The mass was also celebrated at the date of the translatio, 3August. In addition there was a service every Wednesday, possibly limitedto Lent (omni quarta feria, see sequence Predicasti dei care below)(GJERLØW 1968, 127).

Medieval reception and transmission

St. Olaf?s mass was celebrated in the Nordic countries and, as it seems,parts of England, and possibly also in other places in Northern Europe.The mass remained virtually unchanged for five hundred years, from itsearliest transmitted appearence in the English service book from the early1060?s to the printed Missale Nidrosiense (1519). The most importanttextual witnesses are:

Cambridge, Corpus Christi College 422 [a Sherbourne service bookknown as ?The Red book of Darley?, penned in the early 1060s; Olaf ison fol. 162].

•

Copenhagen, The Arnamagnæan Collection, AM 241 b I.• Copenhagen, The Arnamagnæan Collection, AM 98 8º II.• Oslo, National Archives, Lat. fragm. 932 [thirteenth century;Alleluia with verse and a few lines of the sequence Lux illuxit].

•

Reykjavík, Thodminjasafn Íslands, No. 3411 v. [the introit withverse, Alleluia with verse and first part of the sequence Luxilluxit].

•

Printed books:

Graduale Suecanum, Lübeck ca. 1490.• Missale Lincopense, ##•

Missale Nidrosiense, Copenhagen 1519 (without notation).•

For a survey of the British material on St. Olaf, see DICKINS 1940; forthe early Swedish texts, see SCHMID 1945.

Sequentiae

Four sequences for St. Olaf are transmitted. The most important and theearliest sequence is Lux illuxit, from the late twelfth century. Theremaining sequences, Predicasti dei care, Postquam calix babylonis andVeneremur sanctum istum are later and were probably never as widelyspread. The latter is only known from Sweden and Finland.

A. Lux illuxitIncipit/explicit

Lux illuxit letabunda, lux illustris lux iocunda.../...tua salvet dextera.Amen.

Size

Eight strophes.

Editions

BYSTRØM, O. 1903: Ur medeltidens kyrkosång i Sverige, Norge ochFinland, II, Stockholm.

•

? REISS, G. 1912, 12-44. Ugivere: Analecta Hymnica 42, 302.• ? EGGEN, E. 1968, I, 213-21.•

Recordings

Sølvguttene (dir. T. Grythe): Kormusikk fra Norge i Middelalder ogRenessanse, samt fra vår tid. Choeur Gregorien de Paris, Lux illuxitlaetabunda, 1989. Schola Sanctae Sunnivae: Rex Olavus, 2000. Schola CantoGregoriano Sola: Aquas plenas, 2001.

Translations

(Norwegian, nynorsk) EGGEN, E. in undated newspaper article.• (Norwegian, nynorsk) STØYLEN, B. 1923, in Norsk Salmebok 1985, no.741 (adjusted to the melody of Predicasti dei care).

•

(Norwegian, nynorsk) FOSS, R. 1938, 95-98 & FOSS, R. 1949, 111-15.• (Norwegian, bokmål) REISS 1912, 14 (n. 4).• (English) LITTLEWOOD, A. 2001 (CD-leaflets, Scholae Sanctae Sunnivae,Schola Canto Gregoriano Sola) [English].

•

(Norwegian, bokmål) KRAGGERUD 2002, 106-8.•

Date and place

Lux illuxit was composed between ca. 1150 and 1215. The terminus ante quemapplied by REISS, namely the presence of the sequence?s incipit on amanuscript fragment in the National Archives dated ca. 1200, should bedisregarded since the fragment in the hand of the scribe generallyreferred to as the ?St. Olaf scribe?, should be dated closer to 1300 (seeGJERLØW 1968, 35-36). The earliest manuscript fragment with evidence ofLux illuxit is a sequentiary from the first half of the thirteenth century(Oslo, National Archives, Lat. fragm. 418).

Lux illuxit is a testimony to the ?transitional style? often connectedwith the period 1050-1150 (and beyond) and characterized by a variation inthe structure and metre of the verses combined with a certain use ofrhythm and rhyme. This transitional style, however, existed alongside therhymed sequence of the late style (KRUCKENBERG 1997, 145). A few passagesin the sequence seems to owe their wording to the Passio Olavi (or theoffice ?In regali fastigio? based on the Passio), which could indicate adate after ca. 1180 (see Legend above).

The sequence was in all probability composed by a Norwegian, as can beinferred by the reference to St. Olaf as ?our special protector? (tutornoster specialis) (REISS 1912, 17). REISS presents Eirik Ivarsson(archbishop 1188-1206) as a likely candidate for the composer. VANDVIKpoints out that there are four possible composers, who had their educationfrom St. Victor, namely the archbishops Eystein, Eirik and Tore(archbishop 1206-1214) or Tore, bishop of Hamar (1189-1196) (VANDVIK1941). Both Eystein and Eirik were committed to the moulding of a uniformNidaros rite. It would be natural to see the sequence in connection to theother activity in Nidaros during the second half of the twelfth century.

Summary of contents

The strophes 1-3 encourage the people to sing and celebrate on the feastday of St. Olaf. The strophes 4-7 tell of Olaf as a king who longs foreternal life, and is devoted to Christ, suffering many troubles to savehis people and accepting hatred, punishments and exile with an unwaveringmind. The night before the battle he had a vision, and got a foretaste ofwhat he loved, which he finally won through his illustrious martyrdom. Thefinal strophe is directed to Olaf, asking for his protection.

Composition and style

Lux illuxit has eight strophes. The melody changes from strophe to strophein the typical manner of the sequence, with the two versicles orhemi-strophes in each strophe sharing the same melodic line. The onlyexception is the first strophe, which has two different melodies for eachversicle. While the strophes 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 and 8 are predominantlytrochaic (although not equal in structure), the third and sixth strophesare dactylic. The structure is as follows (sung twice in each strophe):

1. 8p + 8p + 7pp

2. 7pp + 7pp + 7pp

3. 6pp + 6pp + 6pp + 6pp

4. 8p + 8p + 7pp

5. 8p + 8p + 8p + 8p + 7pp

6. 6pp + 6pp + 6pp + 6pp + 6pp

7. 8p + 8p + 8p + 7pp

8. 8p + 8p + 8p + 8p + 7pp

The sequence is rhymed in different patterns. For verse 1, 2 and 4 therhyme is aabccb, v. 3 has aaaa, v. 5, 6 and 8 have aaaabaaaab, and v. 7aaabcccb. The use of rhythm and rhyme gained increasing popularity in thehistory of the sequence, culminating in what is called the late style, or?second epoch? sequences, connected with the Abbey of St. Victor in Paris,

and its cantor Adam of St. Victor (d. 1146) (regarding the recentidentification of Adam of St. Victor as Adam Precentor, d. 1146, asopposed to another twelfth century figure d. 1192, see, for instance,FASSLER 1993, 206-7). In the case of Lux illuxit, however, given the lackof uniformity of structure between the strophes, one may see it as asequence of the transitional style rather than the late style (for thetransitional style, see KRUCKENBERG 1997).

The composer is fond of alliteration, anaphor, and other repetitions: ?luxilluxit letabunda, lux illustris, lux iocunda, lux digna preconio.? Str.3a: ?Insignis martiris insignis gloria, dulcis est gaudii dulcis materia.?The repetition in versicle 3a is with seemingly similar words, but as theyare different cases, they actually form the rhetorical figure polyptoton,with insignis first in the genitive case, then in nominative. Dulcis comesfirst in nominative, then in the genitive case. At the same time the wordsmartiris/materia and gloria/gaudii form chiastic alliterations. Otherexamples of polyptoton are found in the following versicles: Str. 3b:?celesti iubilo tange celestia,? Str. 6b: ?felix felicia migrans adgaudia,? Str. 7b: ?Quod amabat pregustavit, pregustatum plus optavit, plusoptatum vendicavit illustri martirio.? The composer evidently strove forrepetition more than variation. A similar joy in word-repetion is found inthe sequence Lux iocunda (most likely by Adam of St. Victor, FASSLER 1993,272), a sequence which was possibly an inspiration for our composer: Str.1a: ?Lux iocunda, lux insignis.? Str. 1b:?Corda replet linquas didat adconcordes nos invitat cordis lingue modulos.? Str. 8b: ?Nil iocundum nilamenum nil salubre nil serenum nichil dulce nichil plenum?. It is alsotempting to compare with the last part of the final verse of the nightoffice in St. Olaf?s office ?In regali fastigio?, where a similar fondnessfor repetition and polyptoton is evident: ?regem rex videt in decore suoet in salutari regis magna gloria regis.?

The melody builds a climax towards the centre of the sequence, as so oftenin the sequences. As in the text there are also melodic quotations ofParisian/Victorine sequences, see below.

Sources and literary models

Even though Lux illuxit is not a late style sequence, the text seemsinspired by sequences by Adam of St Victor, particularly the Eastersequence Lux illuxit dominica (?Lux illuxit Dominica, lux insignis luxunica, lux lucis et laetitiae, lux immortalis gloriae?), the sequence forPentecost Lux iocunda, lux insignis, and possibly also the sequence forSt. Vincentius: Triumphalis lux illuxit. The rhymes ?triumphalis,specialis, malis? as used in v. 8 in Lux illuxit letabunda is found inAdam of St. Victor?s sequence for the relics of St. Victor, Ex radicecaritatis, and similarly ?spiritalis, specialis, malis? in Adam?s sequenceVirgo mater Salvatoris (REISS 1912, 16). The link to the sequence forThomas Becket Gaude Sion et letare also mentioned by REISS suggested onthe basis of the expression felicio commercio seems less important, as Luxilluxit here follows more closely the final verse of the night office inSt. Olaf?s office ?In regali fastigio'?: Felici commercio pro celestiregnum commutans terrenum; As we compare with our sequence v. 2b, we seethat also the choice of the verb is the same as in the night office: Proeternis brevia commutavit gaudia felici commercio. It is therefore morelikely that the Passio or the Office is the source of this particularchoice of words. Also in verse 4a ? rex Olavus constitutus in regnifastigio ? we can sense a link to the Passio and the Office: In regalifastigio constitutus spiritu pauper erat rex Olavus (from the firstresponsory of the night office). The regali fastigio is altered to regnifastigio, presumably to fit the verse better.

The melody of the first strophe of Lux illuxit appears to be a quotationof the transitional sequence Letabundus exultet (EGGEN 1968, 219). Thesecond strophe goes on to quote what is regarded as the melodiccornerstone of the Victorine sequences, namely Laudes crucis. The strophesfive and eight are also founded on melodic lines from Laudes crucis, aswell as the first part of strophe four. These quotations may very well bean expansion of the textual associations to Lux iocunda (see above), sinceLux iocunda was set to the melody of Laudes crucis, at least in the Abbeyof St. Victor (FASSLER 1993, 179).

Purpose and audience

Lux illuxit was made to be sung in St. Olaf?s mass on 29 July. It was alsosung for the octave, and for the translation (3 Aug).

Medieval reception and transmission

The sequence Lux illuxit was probably quite widely spread. In Norway andthe other areas belonging to the Trondheim archsee it would have been?everywhere?, and it also spread to Sweden and Finland, and probablyDenmark, and perhaps other areas in the Northern parts of Europe. In theNorwegian National Archives four fragments are found with the sequence Luxilluxit. In the Swedish National Archives as many as 38 fragments existcontaining the sequence (according to information from G. Björkvall).Apart from these the sequence or parts of it is transmitted in thefollowing manuscripts:

Copenhagen, The Arnamagnæan Collection, AM 98 8° II, fols. 5-8.• Oslo, National Archives, Lat. fragm. 418 [str. 8], thirteenthcentury.

•

Oslo, National Archives, Lat. fragm. 932 [str. 4-5], thirteenthcentury.

•

Oslo, National Archives, Lat. fragm. 1030 [incipit only], thirteenthcentury.

•

Oslo, National Archives, Lat. fragm. 986 [str. 1-6], fifteenthcentury.

•

Reykjavik, Thodminjasafn Íslands, No. 3411 [str. 1-2],fourteenth-fifteenth century

•

Skara, Stifts- och Landsbibliotek, musik handskrift 1; paper codexwritten in Sweden ca. 1550 (Lux illuxit on fol. 245)]

•

Stockholm, Royal Library, Brocm. 196; ?Brocman?s Antiphonarium?,paper codex, sixteenth century (Lux illuxit on fols. 18-19).

•

Uppsala, University Library, C 513; paper codex written in Sweden(Vesterås) ca. 1500 (Lux illuxit on fol. 74-76).

•

Printed books:

Graduale Suecanum, Lübeck ca. 1490, only copy, in Stockholm, RoyalLibrary.

Missale Nidrosiense, Copenhagen 1519 (without musical notation).

Missale Uppsalense ##

Missale Hafniense ##

Missale Aboense ##

B. Postquam calix BabylonisIncipit/explicit

Postquam calix Babylonis.../...cunctis et a sordibus. Amen.

Size

Five strophes

Editions

? REISS, G. 1912, 57-66. [REISS interpreted Predicasti dei care asthe last part of Postquam calix Babylonis in a more original versionof the sequence, preceding the one in Missale Nidrosiense].

•

Analecta Hymnica 55, 272.• ? EGGEN, E. 1968, 222-27. [EGGEN saw Postquam calix Babylonis as alater rewriting of Predicasti, where the first verse has beenreplaced by three new verses. They are edited as two sequences, onecomposed on the basis of the other].

•

Translations

(Norwegian, bokmål) DAAE 1879, 115.• (Norwegian, nynorsk) EGGEN, E. in undated newspaper article.• (Norwegian, nynorsk) FOSS 1949, 115-17.• (Norwegian, bokmål) KRAGGERUD 2002, 110-15.•

Date and place

REISS (1912, 64) suggests that the first three verses of Postquam calixBabylonis are the product of a fourteenth century composer, while theversicle Predicasti dei care and the two last verses are from the latetwelfth or the thirteenth century.

Summary of contents

The first strophe contrasts the chalice of Babylon spewing out snake?spoison with the pot (olla) of the North boiling with the oil (oleo) ofdevotion thanks to Olaf. The second strophe compares the rescue of Noahand his ark to Olaf and that of the Norwegian people: ?The bird brings theflower of the olive (olive), and Noah finds rest on the mountains ofArmania. With Olaf comes a weak breeze of wonderful scent and the key toheaven finds the shores of Norway.? The third strophe elaborates on thename of Olaf resembling the name of ointment (oleum), and his name as theoil effused from the sting of his passion. The two last strophes are thesame as those of the sequence Predicasti dei care (see below).

Composition and style

The sequence Postquam calix Babylonis has five verses as transmitted inthe Missale Nidrosiense, the two final verses corresponding to those ofPredicasti dei care. The three first verses share the same stylisticapproach, and was probably written at the same time, while the two lastverses are of an earlier date. Postquam calix begins with the image ofBabylon without the usual introduction encouraging people to sing andcelebrate a particular feast, which is so common in sequences.

The metre is trochaic, of the kind characteristic of the late style (8p +8p +7pp). The third verse line of the third strophe, however, endssomewhat abruptly (8p + 8p + 4p) in both versicles. The rhyme of the three

first strophes is consistently following a pattern of aabaab, while thetwo last strophes have aabccb.

The theme of the sequence is spinning around the name of Olaf, playingwith similar sounding words like olla, the boiling pot, oleum, the oil ofdevotion, oliva, the ?flower? bringing the news of salvation. In this wayit further unfolds the ?likeness?-approach to Olaf?s name alreadymentioned in the Passio (olla, see above) and known from a number of othersaints? lives (e.g. Sanctus Kanutus rex). According to the third stropheKing Olaf bears the name of ointment, and his name is the oil effusedthrough the sting of his passion. The style of this sequence has notimpressed many modern scholars. According to REISS ?the bombasticexpressions and somewhat far-fetched metaphors in the first three versesappear a little strange? (REISS 1912, 59, here quoted in Englishtranslation from EGGEN), a view supported by EGGEN (1968 I, 225). ByGJERLØW the first three verses are described as a ?turgid effort with atiresome wordplay? (GJERLØW 1988, 10). KRAGGERUD has spoken out in defenceof the sequence, claiming that it displays a rather refined use ofbiblical references: Babylon is presented as the golden chalice inJeremiah (51, 7) leading the world astray with its poison (Apoc. 18, 23),here described as the snake?s poison (fel draconis) of the enemies of Godreferred to in the Deuteronomy (32,33). The vision of the boiling pot fromJeremiah (1, 13) is also found in the initial parts of the Legend, alongwith the references to the North, also from Jeremiah (50, 3). Olaf is thenidentified with Noah from the Old Testament in strophe 2, and with Christ(?the anointed?) from the New Testament in strophe 3, who effused bloodand water through the wound from the spear at his passion (John. 19, 34)(KRAGGERUD 2002, 108-115).

Sources and literary models

The composition is charged with biblical allusions. It also seems tocontinue along the path of Passio Olavi in its reference to Jeremiah andthe vision of the boiling pot, along with the new role of the North. Thesource for the two final verses seems to be an older sequence, nowbeginning imperfectly Predicasti dei care (see below).

Purpose and audience