Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

-

Upload

dominos021 -

Category

Documents

-

view

219 -

download

0

Transcript of Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

1/12

Journal o f Scientific Exploration, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 47-58, 1997 0892-3310/97 1997 Society for Scientific Exploration

Wishing for Good Weather:A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

R O G E R D . N E L S O NPrinceton E ngineering Anom alies Research, Princeton University, Princeton, N J 08540emai l [email protected]

Abst rac tMany hum an activities are affected by the w eather, an d there is along history of ritualsand cerem onial efforts aimed at controlling it. In mod -em societies,such efforts are largely vestigial and am oun t to inform al hopingor wishing for good weather for special occasions. Reunion and commence-ment activities at Princeton Un iversity, invo lving thousand s of alum ni, grad-uates, fam ily and others, are held ou tdoors, and it is often remarked that theyare almost always blessedwith good weather. A comparison of the recordedrainfall in Princeton vs. nearby comm unities shows tha t there is significantlyless rain, less often, in Princeton on those days with major outdoor activities.

IntroductionLarge gatherings of people with a common interest provide opportunities toassess a possible effect of their collective intentions or wishes on the environ-ment. Repeated gatherings may provide the essential components of a naturalexperiment allowing formal assessment of potential effects of group con-sciousness. For example, many of the year-end ceremonies at Princeton Uni-versity traditionally bring huge numbers of people together in planned out-door events. Of course everyone involved hopes the weather will be pleasantand dry for Reunions, the traditional P-Rade of alumni, and all the varied ac-tivities associated with Princeton's Commencement, and it seems remarkablyoften to be so. It is quite common to hear someone remark, "As usual, the rainstayed away, but no wonder, with all those people wishing for good weather."Indeed, it is likely that most Princetonians have heard this idea expressed, andm a n y will half-seriously have said something along these lines themselves.President Clinton was invited to give an address at the 1996 Commencement,making contingency plans considerably more difficult than usual. An article inthe local newspaper1 about the complex preparations included a description ofthe conditions that could require moving 10,000 people indoors:

The third scenario is the Monsoon scenario, where it rains hard and comm encementhas to be m oved to Jadw in Gym . Traditionally, this never ha ppens at a Princeton U ni-versity comm encem ent. Those few times in recent years w hen precipitation is not onlyforecast bu t seems imminent, th e rain has miraculously held off.'Barbara Johnson. Princeton Town Topics, Wednesday, May 22, 1996.

47

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

2/12

48 R. D. NelsonFor most people it feels natural to wish and hope for good weather for thespringtime a lum ni celebrations and the ceremonies of Commencemen t , but

it's something else again to expect any corresponding result. Nevertheless,whether there might indeed be som e effect of those hopes and wishes is an in-teresting question. By m ode rn , scientifically condit ioned standards, it seemsunlikely, but with a properly formulated analytical approach it is possible toobtain an objective answer to the question.The Archives

T he Seeley G . Mudd Library archives includes documents on Commence-m e n t and related activities going back 250 years. Autumn w as the season forgraduation during Princeton's first century, with nearly all ceremonies held inSeptember, but in 1844 th e University began celebrating Commencemen t inth e Spring, near ly a lw ays in June. Beginning in 1922 th e graduates receivedtheir degrees on the lawn outside Nassau Hall and, weather permitting, thishas been the venue since t ha t time.By tradition, the day of Commencement is a Tuesday, with Baccalaureateand Class Day on the preceding Sunday and Monday, respectively. The actualdate varies considerably, and in this century th e Tuesday chosen has graduallymoved from late and middle June to earlier dates until, as in 1995, Com-mencem en t was held in late May.

Tradit ionally, th e graduation festivities begin w ith the Reu nions of the largeand deeply interconnected Princeton a lumni family, a gathering that culmi-nates in the renowned A l u m n i P-Rade on the Saturday preceding commence-ment . Th us, there are actually four days packed with major even ts related toReunions and Commencement , and most of the activities are planned for theoutdoors, with large numbers of people sharing an interest in having goodweather. In recent times, as many as 15,000 alumni, their fam ilies and friends,a nd m a ny well-wishers from the town, crowd the campus for the P-Rade. Onth e day of Commencement , some 9000 tickets are provided to the 1100-oddgraduating seniors, 300 graduate students, their families and fr iends to attendthe ceremonies, planned for the green in front of Nassau Hall, w ith a contin-gency plan for relocation to Jadwin Gymnasium in the event of bad weather.

The Weather DatabaseGiven th e dates of gradua tion over th e years, the second part of our devel-oping analytical picture requires data from th e daily records of weather for

stations at Princeton and surrounding com m uni t ies . The m ost impor tan t ques-tion for the graduates, the a lum ni and the U niversi ty administration, concernsrain, since it definitely affects outdoor activities, and makes a rain cont in-gency plan necessary where possible. Although th e weather is notoriouslyfickle, because it is of abiding interest, our governm ent provides services thatmeasure and document practically anything one might want to know about

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

3/12

Wishing fo r Good Weather 49temperature , pressure, precipitation, e tc . , on a daily basis. A widely dispersedne twork o f stations records wea the r parameters in a standardized way, andsome have been doing so for mu ch of the present century. One of these stationsoperated in Pnnce ton from 1950 to 1986, and some stations in surroundingcommuni t ies , e. g. , N ew Brunswick, have daily records going back more than70 years.

An Analytical QuestionWith the history of P rinceton Commencements and the historical record oflocal weather in hand, we can ask whether there is any difference in rainfall onCommencemen t Tuesday in Princeton over th e years, compared with rainfallin nearby New Brunswick or Trenton on the same day. For a clearer picture, th e

survey can be extended to other communit ies surrounding Princeton, and thequestion formulated more specifically: Does the amount of precipitation onthe Tuesday of Princeton's Commencement tend to be less than the averageacross surrounding communit ies on the same day? Such a comparison can bemade for the P-R ade, Baccalaureate and Class Day as well , and the days withsignif icant outdoor activities can be combined to give a larger and more gener-al sample. The question needs ref inement, however, to address the possibilitythat Princeton might have a slightly different micro-climate relative to the sur-rounding area (many people apparently do think of Princeton as something ofan oasis). An a ppropriate check on this possibility is a repetition of the analy-sis on days that should be otherwise similar, but do not have a coherent groupmotivated to wish away th e rain. Presuming everyone's attention has turned toother things, the days immediately following Comm encement would seem toprovide a reasonably apt com parison standard for the ev entuali ty that Prince-ton's weather at this t im e of year is typically different from that of its neigh-bors.Because any analysis of already existing data must be considered pos t hoc , itis essential to consider the implications of the choices made in conductingsuch a "natural experiment". Given an explicit experimental hypothesis, e. g. ,th e weather is susceptible to influence from th e conscious or unconsciouswishes of a group, and a w ell-justified choice of venue made before any actualanalysis, th e results w ill c orrectly represent th e viability of the hypothesis. T hepresent case meets these criteria, in that the experim ental question w as raisedspecifically for the Princeton situation, with no prior examination of any rele-v a n t data, and the records chosen for analysis w ere specific an d appropriate toth e hypothesis. Replications of this natural experiment elsewhere will be re-quired to assess th e robustness and generality of its findings, and they canreadily be performed using the same approach. For example, the Rosebowlgame and parade in Pasadena are said nearly a lways to have good weather, de-spite that they occur on New Years day, during California's rainy season.Again there is a human expectation and desire for good w eather, and a simpleanalysis can compare th e rainfall in Pasadena on New Years day with sur-

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

4/12

50 R . D. Nelsonrounding locales and days to determine whether there is a difference in accor-dance with th e hypothesis.

The AnalysisThe daily records of precipitation at Princeton and six surrounding stationswere obtained from the Nat ional Climatic Data Center, in Asheville, NorthCarolina.2 The other communities used for comparison were Trenton,Moorestown, Indian Mills, New Brunswick, Boonton and Belvidere, and thedata, measured in 100ths of an inch, were obtained fo r each day in Ju ne for allyears with daily records. Figure 1 is a m ap of the area, with Princeton and thesix surrounding stations indicated; their distance from Princeton varies fromabout 10 to 40 miles.

For each station, an epoch of the nine days centered on the date of Prince-ton's Commencement was generated for each of the years the Princeton sta-tion w as operating, and the precipitation index for those days was retrievedfrom th e database. Most measurements were m a de at either 6:00 AM , or 6:00PM a nd , although the activities of interest are typically set closer to noon, th ereadings w ere used directly as the a m o u n t of rain for the day. Averaging eachday separately across th e 36-year period (1984 is missing from th e Princetondata) for Princeton and for all six of the other stations, a mean precipitationindex was obtained for each of the stations and days of interest. Figure 2 showsa comparison of Princeton's average precipitation during the four days fromReunions to Commencement with the corresponding composite for the sixother communities, and it does appear that the mean level of rain is low er forPrinceton on the days of the P-Rade , Baccalaureate and Class Day. However,th e average rainfall on Com m e nc e m e n t over this period is slightly higher atPrinceton, mainly attributable to a downpour of some 2.6 inches on June 12,1962. (The average for the surrounding stations on that day w as a mere 0.95inches.) Interestingly, m em bers of the class of 1962 report that the rain heldoff unti l after th e ceremony.

Although they look suggestive, th e variability of these data is too great tojustify a con clusion that any of the apparent differences are meaningful , and amore incisive approach is needed. The common statistical tests for differencesare not appropriate beca use the data are not normally distributed. Figure 3 dis-plays th e f requency with which various amounts of rain occur, and indicatesw hy a simple test of the m ean differences would be inappropriate. Both th emedian and the m odal precipitation levels are zero, and because of the enor-mously skewed distribution, th e m e a n is clearly not an ideal measure of cen-trality for the comparisons w e wish to make .

The figure clearly shows the large num be r of days with very little rain, andprogressively fewer days with larger amounts. About 72% of days in this t imeperiod have no rain at al l in Princeton, w hile the surrounding communit ies av-2More information may be found at http://www.ucar.edu/, or by contacting data support specialistWill Spangler, [email protected].

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

5/12

W ishing for Good Weather 51

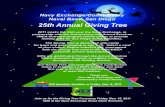

Fig. 1. Central New Jersey, with Princeton and the six comparison stations indicated. M ap gen-erated byTiger Mapping Service, http://tiger.census.gov.

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

6/12

52 R. D. Nelson

Fig. 2. Mean precipitation fo r Princeton compared with six surrounding towns on the four days:P-Rade, Baccalaureate, Class Day and Commencement . One s igm a error is indicated.

Fig. 3. A distribution o f daily precipitation amounts displays a rapid decrease in the proportionof larger accumulat ions.

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

7/12

Wishing for Good Weather 53erage about 67% dry da ys, again suggesting that Princeton's w eather tends tobe better than m ight be expected for the period of interest.Proceeding to a more formal assessment, a non-parametric analytical ap-proach that is designed to accommodate variables of this nature compares cu-mula t ive distributions of the daily precipitation totals. Figure 4 displays, foreach of the four days of interest, Princeton's cumula t ive rainfall against th ecomposite of the six surrounding stations.In this display, where th e extraordinary rainfall recorded in 1962 plays a lessweighty role, Comm encement day appears to be fair and dry somewha t moreoften in Princeton than in the neighboring communit ies (Fig. 4d). Such a trendtoward less rain, less often, is quite persuasive on Saturday, Monday and Tues-day, but on Su nday, the d ay of Baccalaureate (Fig. 4b), no clear tendency is ev-ident. T he amoun t of data available for these com parisons is too small to justi-fy m u c h interpretation, but it is notewor thy that this is the only day withoutmajor outdoor activities since the Baccalaureate ceremonies take place insideth e Universi ty Chapel, regardless of the weather. In the other cases, th ePrinceton data are shifted toward lower daily precipitation rates, but only onClass Day (Fig. 4c) does the difference approach conventional statistical sig-nif icance, based on a non-parametr ic Mann-Whi tney Ra nks test, yielding a Z -score of 1.607, with a corresponding proba bility of 0.054.When w e combine th e data from th e three days with major outdoor activi-ties, the distributions are sm oother, as can be seen in Figure 5, and the statisti-cal power to determine whethe r there is a consistent difference betweenPrinceton and i ts n eighbors is enhan ced.In this case it is necessary to consider any autocorrelation indicating no n-in-dependence among th e days , but this is negligible for the sample in hand , witha lag-one autocorrelation coefficient of 0.049. Pooling th e rainfall accumula-t ions for these three days in Princeton to compare with the correspondingpooled data from the surrounding stations, the Mann -W hitney test for a differ-ence in the predicted direction yields a Z-score of 1.656, jus t exceeding th econvent ional 5% threshold for statistical signif icance.

Thus, although the graphical displays are striking, and consistent with th ehypothesis, th e formal statistical assessment based on data from 1950 to 1986yields only nominal ly significant evidence that th e apparent difference be-tween Princeton and the surrounding com m unities is other than a chance f luc-tuation. Moreover, to evaluate th e situation fairly, w e still mus t considerwhe the r Princeton m ight have a micro-climate that is different from it s geo-graphical sur round. A similar comparison of the days following Commence-ment, using th e same cumulative distribution approach, is shown in Figure 6.Here, the curves are scarcely distingu ishable, and the Mann-Whi tney test forthe pooled data compar ing Princeton to the surrounding area yields a Z-scoreof 0.222, with a related probability of 0.412.While th e formal com parison appropriately uses data for the surroundingt ow ns only from the years 1950 to 1986, most of these stations have a longer

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

8/12

54 R. D. N e l s o n

(4a)CUMULATIVE RAINFALL SUNDAYBACCALAUREATE

(4b)Fig . 4. An ordered accumulat ion of dai ly precipitat ion totals shows less f requent , and smalleramounts of precipitat ion in Princeton fo r three of the four days.

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

9/12

Wishing for Good Weathe r 55

(4c)CUMULATIVE RAINFALL TUESDAY

COMMENCEMENT

(4d)Fig. 4. An ordered accumulat ion of daily precipitation totals shows less frequent, and smalleramounts of precipitation in Princeton fo r three of the four days .

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

10/12

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

11/12

Wishing for Good W eather 57record, and if all years are used, nearly twice as many days a re available to es-t imate the amount of precipitation accumulating in the surrounding areaa r ound the t ime of Princeton's Commencement. If Class Day is compared withthis more comprehensive estimate, the Z-score is 1.814, with p = 0.035. Whenthis estimate is used in the com parison of the three outdoor days com bined, theresult is Z = 1.996, and p = 0.023. Comparison of the three day s following com-m encem ent y ie lds a corresponding result of Z = 0.540, p = 0.295. Though con-sistent w ith the formal calculations, these "full database" values are vulnera-ble to any longer-term chang es in weather patterns. A direct comparison of thedata from th e 36-year period of the Princeton weather station against the re-maining data shows a m argina l ly s ignif icant Z-score of 1.610, suggesting t ha tthere m a y ha ve been a change, and that we should not place as mu ch weight onthese as on the statistically less powerful formal calculat ions.Finally, we may ask whethe r th e a m o u n t of precipitation is different overtime in Princeton itself, by comparing th e days of interest with immediatelysur rounding days, to see if this t ime period in Princeton differs from th e sea-sonal t rend. This temporal comparison has a pattern similar to that of the spa-tial differences. The composite Z- score ranges from 1.370 to 1.972(p = 0.085,0.024, respectively), depending on the num ber of surroun ding days chosen forthe comparison. No obvious criterion is available for a fully formal compar i -son of the temporal trends, but again the data suggest that a small decrease inthe probability of rain is correlated with this large gathering of people fo rshared enjoym ent of outdoor ceremonies and activities.

A Curious SituationAlthough m any of us wish fervently fo r nice weather fo r special occasions,and some are even m otivated to offer up a little prayer, it doesn ' t seem likelyt ha t ma n y of us believe it will do any good. A modern education (such asPrince ton delivers) tends to include a surfeit of implici t reasons and argumentsagainst such an eve ntuali ty, and i t certainly doesn't fit easily within our cur-

rent scientific models of the world. Yet, w e recognize tha t these models are in-complete, perhaps most glaringly because they have so little to say abouthum a n consciousness, including such hopes and wishes as might , possibly, af-fec t the weather.W e have recently learned to view weather patterns in terms of chaos theory,where infinitesimally small effects can expand into great changes; th e beat of aBrazilian butterfly wing m ay propagate through complex weather systems tocause a downpour in a small New Jersey town . Could th e effects of c o m m u n a linterest from a great concentration of Princetonians com pete with that butter-fly wing?A look at actual weather data seems to suggest that precipitation tends tostay away from Princeton for the P-Rade , and Class Day, and Commencemen t ,to a somew hat unl ike ly degree. These intriguing results certainly are n' t strongenough to compel belief, but the case presents a very chal lenging possibility,

-

8/3/2019 Roger D. Nelson- Wishing for Good Weather: A Natural Experiment in Group Consciousness

12/12

58 R. D. Nelsonbecause if the analysis is correct, th e only good candidate to explain th e appar-ent differences, other than chance, would seem to be an influence from an in-formal but powerful c o m m u n a l wish for dry weather . In any case, it surely isprem ature to conclude, as the graffito has it, that God w ent to Princeton, butw e m ay need to reconsider the old saw, "Everyon e talks about th e weather, butnobody does anything about it."

AcknowledgmentsThe Princeton Engineering Anomalies Research program is supported by anum be r of foundat ions and individ uals, including the John E . Fetzer Institute,th e Institut fr Grenzgebiete der Psychologie und Psychohygeine , th eLifebridge Foundat ion, the McDonnell Foundat ion, the Ohrstrom Founda-

t ion, Mr. Richard Adams, M r. Laurance S. Rockefeller, and Mr. Donald Web-ster.