Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities in ‘attrition through...

Transcript of Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities in ‘attrition through...

This article was downloaded by: [North Dakota State University]On: 16 November 2014, At: 19:59Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH,UK

Ethnic and Racial StudiesPublication details, including instructions for authorsand subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rers20

Return to sender? A comparativeanalysis of immigrantcommunities in ‘attritionthrough enforcement’destinationsAngela S. GarcíaPublished online: 18 Jun 2012.

To cite this article: Angela S. García (2013) Return to sender? A comparative analysisof immigrant communities in ‘attrition through enforcement’ destinations, Ethnic andRacial Studies, 36:11, 1849-1870, DOI: 10.1080/01419870.2012.692801

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.692801

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all theinformation (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform.However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make norepresentations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, orsuitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressedin this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not theviews of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content shouldnot be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sourcesof information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions,claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilitieswhatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connectionwith, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes.Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly

forbidden. Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

Return to sender? A comparative analysis

of immigrant communities in ‘attrition

through enforcement’ destinations

Angela S. Garcıa

(First submission September 2011; First published June 2012)

AbstractDrawing on surveys from two Mexican immigrant sending communities,this paper comparatively examines the link between subnational policystructures in US destinations and immigrants’ settlement and residencybehaviour. It focuses in particular on attrition through enforcement policyat the local and state level that is formed to trigger the voluntary exit ofundesirable immigrants. With a twofold comparison of immigrants inthree cities and two states, the analysis indicates that immigrants do notalter the duration of time they spend in receiving locales or change theirstate of residence due to restrictive subnational policies. Rather, economicand social factors more prominently shape immigrants’ settlement andresidency patterns. The implications of this analysis are discussed withparticular attention to the incorporation process for immigrants whoremain in destinations with attrition through enforcement policy.

Keywords: unauthorized immigration; attrition through enforcement;

subnational immigration policy; receiving communities; settlement; incorporation.

Introduction

States and cities across the USA have long responded to undesirableimmigrants with restrictive policies to induce them to leave. FromCalifornia’s 1862 Chinese Police Tax (State of California 1862, p. 1) thataimed to ‘discourage the immigration of the Chinese’ to Arizona’s 2010Senate Bill 1070 (State of Arizona 2010, p. 2) that sought to ‘discourageand deter the unlawful entry and presence of aliens’, laws of this typelitter public records past and present. Scholars and policy makers applythe term ‘attrition through enforcement’ to contemporary legislation

Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2013Vol. 36, No. 11, 1849�1870, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2012.692801

# 2013 Taylor & Francis

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

that seeks unauthorized immigrants’ voluntary exit rather than theirforced removal (Vaughan 2006). These policies attempt to detersettlement and encourage mass self-deportation by making life inreceiving locales exceedingly difficult. Common strategies includecurtailing access to key institutions and services � such as education,employment, housing, and public benefits � criminalizing acts ofassistance to unauthorized immigrants, and including local police infederal immigration enforcement.

Since the end of the twentieth century, subnational attrition throughenforcement policy has multiplied.1 While normative analysis of theselaws is increasing (Spiro 1994; Skerry 1995; Olivas 2007), very fewstudies focus on the empirical effects of such restrictions for immigrantcommunities (Coleman 2007; Ramakrishnan and Wong 2010;Varsanyi 2010).2 The fundamental question of whether this type oflegislation influences immigrants’ decisions about where to liveremains unclear. This article presents one of the first comparativestudies of the empirical outcomes of attrition through enforcementlaw, demonstrating that immigrants � both legal and unauthorized �do not settle for shorter durations or change their place of residencedue to these state- or local-level policies.

The literature on national immigration control, which indicates theinefficacy of states’ attempts to prevent irregular migration in the USAand Europe, serves as an impetus for this research (Massey et al. 1998;Cornelius et al. 2004; Bloch and Schuster 2005). This scholarshipmaintains that regardless of increased immigration control andsurveillance, unauthorized entry remains inevitable. Departing fromthis conclusion, my research focuses specifically on state and localenforcement. Despite legal threats and hostile reception, this analysisindicates that settlement and residency behaviours are driven byeconomic and social processes rather than restrictive subnationallegislation. I argue that exclusionary policies in receiving locales, whilelikely mediating incorporation, fail to garner attrition.

To evaluate whether unauthorized immigrants react to restrictivesubnational policies by voting with their feet, I avoid speculativeanecdotal and media reports as well as estimates of the unauthorizedpopulation extrapolated from government data. Rather, I root myanalysis in theories of settlement and utilize bi-national surveys ofimmigrants from two Mexican sending communities that includedirect measures of authorization status. With the data sets, I constructa twofold comparison of immigrants’ settlement and residency indestinations that represent contrasting approaches to immigrationpolicy making: three cities in Southern California (Anaheim, Ingle-wood, and Los Angeles) and two states (Oklahoma and California).

The article proceeds by reviewing the recent history of state andlocal involvement in immigration policy. Next, I outline the principal

1850 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

debates in the literature, noting that scholarly discussion has revolvedaround consideration of legal norms and policy motivations. Adescription of case selection and methodology precedes the study’sfindings. To conclude, I discuss the implications of this analysis withparticular attention to the incorporation process for immigrants who,despite being targeted by attrition through enforcement policies,remain in restrictive destinations. This question is critical to anemerging research agenda on subnational immigration law.

Subnational immigration policy

For approximately the first 100 years of American history, states andlocalities largely formulated their own immigration policy. These lawswere often ethnically selective by design, intended to recruit preferredimmigrants, such as north-western Europeans. At the same time, theyalso functioned with the logic of attrition through enforcement,seeking to keep less desirable immigrants � like Asians � outside ofstate and local jurisdictions (Zolberg 2006). Control of immigrationpolicy making did not shift from the subnational level to the federalgovernment until a series of Supreme Court rulings in the latenineteenth century articulated the plenary power doctrine, declaringthe regulation of immigration a federal competency (Motamura 1990).

A jurisdictional division of competence rules immigration policytoday. The federal government exercises its plenary power to developnational immigration policy that regulates entry and exit and the termsunder which immigrants stay. Also falling under federal control is theenforcement of civil aspects of immigration law, such as entry withoutinspection and deportation (Fix and Passel 1994, pp. 3�4). Federalplenary power does not entirely exclude states and localities, however.Subnational jurisdictions can form immigrant policy, or efforts aimedat incorporation within receiving communities. In terms of enforce-ment, state and local authorities may also control some criminalviolations of federal immigration law. For example, if state lawpermits, a charge of human smuggling is within the subnationalenforcement domain (Seghetti, Ester and Garcia 2009).

Although the distribution of immigration-related tasks betweenfederal and subnational jurisdictions appears tidy, it has never beenstatic (Filindra 2009), and three recent developments have blurred itfurther. The first revolves around the federal government’s partialdevolution of its immigration enforcement authority. Section 287(g) ofthe 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant ResponsibilityAct authorizes select state and local officers to perform the functionsof federal immigration agents, allowing them to actively enforcefederal civil immigration law (ICE 2011a). A second shift centers onSecure Communities, a federal programme formed in 2008 to detect

Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities 1851

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

unauthorized immigrants in state and local jails. Rather thandevolution, it represents a powerful administrative mechanism basedon automated data sharing that extends the reach of federalimmigration authority. Under Secure Communities, the FederalBureau of Investigation (FBI) is an intermediary: it sends fingerprintsreceived from jails for criminal record checks to Immigration andCustoms Enforcement (ICE) officials, who use their databases toidentify deportable immigrants (ICE 2011b).

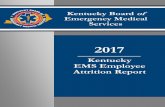

This paper focuses especially on the third development affecting thedivision of immigration responsibilities � state and local immigrationpolicies. California’s Proposition 187 of 1994, which curtailed un-authorized immigrants’ access to public benefits and services, set thetone for many laws that followed (Varsanyi 2010, pp. 1�2). Althoughalmost none of it was enacted, the proposition’s influence stems fromits deflection of voter attention away from post-Fordist economictransformations and towards government spending and budgetdeficits, which directed hostility to immigrants portrayed as undeser-ving and costly (Calavita 1996). After Proposition 187, an increasingnumber of subnational governments began to develop immigrationpolicies (see Figure 1).3

Attrition through enforcement is a prevalent trend within this body oflaw (NCSL 2011). By applying pressure from the inside, this legislationaims to make life for unauthorized immigrants as difficult as possible,with the expectation that they will relocate to more accommodatinglocales or return to their countries of origin (Krikorian 2005). To thisend, such polices enact a range of restrictions, from limiting criticalaccess to housing and employment to reducing rights to education,

Figure 1. Number and outcome of state-level immigration policiesSource: National Conference of State Legislaturesa2011 data for first quarter of the year only

1852 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

official identification and public benefits. Some laws carve out a role forpolice officers to act as federal immigration agents, while otherscriminalize acts of assistance to the unauthorized. Implicitly targetingtoday’s despised immigrant groups � Latinos generally, and Mexican-origin migrants specifically � attrition through enforcement policies arefacially neutral yet intended for immigrants of particular ethnicity andnational origins (Martos 2010).

Explaining attrition through enforcement

Legal debates and policy motivations

Academic analyses of subnational immigration law have coalescedaround two concerns. The first considers the normative question ofwhether states and localities should be involved in immigration policymaking. In this regard, the overarching objection to subnationalattrition through enforcement legislation is that it violates the federalplenary power doctrine (Wishnie 2001; Pham 2004). Other scholarscounter that state and local jurisdictions have the ‘inherent authority’to enforce federal immigration laws (Skerry 1995; Kobach 2004).

The second issue focuses on why particular states and localities formimmigration policy. Scholars argue that ineffective or absent federalimmigration legislation motivates subnational authorities to developtheir own (Spiro 1994). However, this account cannot explain whycertain areas pass restrictive rather than accommodating legislation �or none at all. Analysts note that foreign-born demographic growth iscommon in many restrictionist destinations (Furuseth and Smith2010), as is Republican partisanship (Ramakrishnan and Wong 2010).Policy entrepreneurs, who blame immigrants for social problems, arealso influential (Doty 2003).

Effects on immigrant communities

Despite these contributions, we know little about the practical effects ofattrition through enforcement policies, like whether they influencewhere immigrants choose to live and how long they stay. The few studiesthat do discuss outcomes suffer from two serious flaws. First, many relyon anecdotal evidence and media reports rather than empirical data andrigorous analysis. For example, in 2006, the city of Hazelton, Pennsyl-vania passed the Illegal Immigration Relief Act to curtail unauthorizedimmigrants’ employment and housing. Promptly afterwards, the mediareported an exodus of immigrants from the municipality. Scholars haveproblematically cited these accounts and claims from Hazelton’srestrictionist mayor as evidence of the policy’s attrition effect(Doty 2003, p. 89; Fleury-Steiner and Longazel 2010, p. 160).

Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities 1853

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

Similarly, Allegro (2010, pp. 180�1) relies on media reports to argue thatexclusionary legislation in Oklahoma resulted in mass immigrantexpulsion.

Other studies draw from Census Bureau data. Some argue thatunauthorized immigrants in restrictive destinations return home ormove to more accommodating locales (Camarota and Jensenius 2008;Lofstrom, Bonn and Raphael 2011). Scholars that adopt a moresophisticated methodology, including analysis of other governmentdata like public school enrollment, come to inconsistent conclusionsabout whether exclusionary policy leads to attrition (Koralek, Pedrozaand Capps 2010; Capps et al. 2011; Pedroza 2011). Regardless, theseanalyses are critically limited because no governmental statisticalsource identifies unauthorized immigrants precisely as an identifiablecategory of persons, and thus estimations of this population arenecessarily uncertain.

Theoretical approaches

Reliance on anecdotal reports and government data may explainscholars’ conflicting findings regarding the effects of subnationalattrition through enforcement policy. However, these studies also failto engage the literature on immigrant settlement. As an alternative,this paper takes into account theories that explain the drivers ofsettlement behaviour, particularly labour markets and social networks.This scholarship emphasizes the economic and social processes ofsettlement, variables that caution against uncertain declarations ofimmigrant attrition in restrictive cities and states.

Piore’s (1979) theory of dual labour markets argues that bothimmigration and settlement stem from advanced industrial societies’structurally embedded demand for labour in dirty, difficult anddangerous jobs. Mexican settlement in California, for example, issignificantly influenced by regional labour market demand (Cornelius1998). As far as subnational restrictions are concerned, the logicalcorollary is that as long as demand continues to drive immigration,employment should shape settlement and residency behaviours.

Piore (1979, pp. 52�68) also explains the transition from immigrantsojourner, or target earner, to settler, or one who intends to stay in thedestination country. While the distinction is neither static nor absolute,settlement typically occurs as a stable migrant community forms in thedestination. This argument is taken up by network theorists whoconceptualize migration as an additive process in which expandingnetworks bind immigrants more closely to settled life in the destina-tion over time (Massey 1986; Massey et al. 1987). Immigrantexperiences in restrictive locales should follow this same logic. Indeed,

1854 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

the very threat of exclusionary policy may push migrants to rely evenmore on their web of social contacts, furthering their settlement.

Methodology and cases

To assess the effects of restrictive subnational policy, I employ acomparative methodology that draws on surveys collected by theMexican Migration Field Research Program (MMFRP) in 2009 and2010 (Cornelius et al. 2010; FitzGerald, Alarcon Acosta and Muse-Orlinoff 2011).4 Table 1 contains a summary of my cases. The data setsare composed of surveys of adult migrants (aged fifteen to sixty-five)from different sending communities. While both are rural, theirmigration histories contrast sharply. The 2009 data set contains 151migrant surveys from Tunkas, an ethnically Mayan village in the stateof Yucatan. With 2,800 inhabitants, Tunkas is a new sendingcommunity within its first generation of northward migration. The2010 data set consists of 263 migrant surveys from Tlacuitapa, Jalisco.The out-migration of this traditional sending locale of 1,200 mestizoinhabitants dates back over seventy years (INEGI 2005).

From Tunkas to Anaheim, Inglewood and Los Angeles

Tunkaseno migrants are ideal subjects through which to observe theoutcomes of subnational policy because their characteristics makethem particularly vulnerable to restrictions. As recent arrivals, over 85per cent lack authorization status (Table 2). In comparison to migrantsfrom more established sending communities like Tlacuitapa, the

Table 1. Selected cases

Sendingcommunity

Emigrationhistory

Destinationpolicy

Analysislevel

Dependentvariable

Tunkas,Yucatann�151

Short Restrictive:Anaheim, CA

City policy Length of settlement

Neutral:Inglewood, CAAccomodating:Los Angeles, CA

State of residencyTlacuitapa,

Jaliscon�263

Long Restrictive:Oklahoma

State policy

Accommodating:California

Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities 1855

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

networks of Tunkasenos are also relatively small, with an average ofthree family members (spouse, children, siblings, parents and grand-parents) in the USA. In addition, these migrants remain rooted intheir sending community, with less than 30 per cent perceiving thatmigration is necessary for economic progress. Taken together, thesefactors would likely contribute to the self-deportation thrust ofexclusionary legislation. If the attrition through enforcement approachworks to push immigrants out of certain communities, then itsinfluence should be apparent in the case of Tunkasenos.

With the Tunkas data set, I compare immigrants’ settlementbehaviour in their major destinations: the Southern Californian citiesof Anaheim (in Orange County), Inglewood (in Los Angeles County)and Los Angeles proper. These locales’ policies range from restrictiveto accommodating, with Anaheim most representative of attritionthrough enforcement. The city has long demanded the presence offederal immigration officers in its jail to identify unauthorizeddetainees, for example. Following the shooting of a police officer byan unauthorized immigrant, in 1995 the city council unanimouslyapproved a resolution calling for the Immigration and NaturalizationService (INS) agents.5 The INS began a pilot programme in the jail toscreen for immigration status a year later (Everly 1996). Anaheimcouncilmen lobbied for additional federal support, and SenatorDianne Feinstein (D-CA) and Representative Christopher Cox(R-CA) sponsored successful amendments to the 1996 federalimmigration reform requiring the INS jail presence.6 In 1997,Anaheim made its way into federal law again when President Clinton

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for Tunkasenos, by city of residency

Anaheim Inglewood Los AngelesVariable (n�57) (n�57) (n�37)

Unauthorized 82% 91% 86%Male 53% 67% 68%Need migration 25% 30% 30%US debt 1 loan: 11% 1 loan: 7% 1 loan: 8%

2 loans: 5% 2 loans: 5% 2 loans: 3%

M

Age (years) 37 36 37Education (years) 8 8 8No. of family in 4 3 2USA 286Wage ($/week) 294 291 4Duration last trip (years) 6 6

N�151

Source: MMFRP

1856 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

signed HR 1493, which solidified funding for the city’s INS agents andexpanded the programme to other jails.7 As of March 2011, immigra-tion officers continue to check the status of detainees in Anaheim.8

The city’s attrition through enforcement toolbox grew as theAnaheim Union High School District (AUHSD) embraced restric-tions. In 1995, the board considered a resolution to identifyunauthorized Mexican students and charge Mexico for the cost oftheir education. Despite broad support, the policy was voted down(Delson and Mehta 2007), although in 1999 the board passed a similarresolution seeking reimbursement from the federal government andcalling on the INS to check all pupils’ immigration status.9 Anotherproposal introduced in 2001 to require students to produce proof ofUS citizenship ultimately failed (Sacchetti 2001).

For Tunkasenos in Inglewood, just a thirty-minute drive away, thecity’s marked neutrality in matters of immigration stands in sharpcontrast to Anaheim’s activism. The Inglewood City Council has notwaded into the contemporary waters of local immigration restrictionor accommodation. Inglewood’s Police Department (IPD) has fol-lowed the city council’s lead.10 For example, in its 2008 request that thecouncil authorize a detective to an ICE money laundering collabora-tion, IPD emphasized:

the task force targets narcotics offenders and organizations, and isNOT involved in the enforcement of immigration related matters.The Police Department is acutely aware of the sensitive nature ofimmigration issues and is committed to only participating in thistask force. (IPD 2008, p. 3, original emphasis)

Members of the Inglewood Unified School District Board have alsoavoided a strong stance on immigration. The board’s most politicalposition in this regard is a statement responding to Proposition 187 of1994: ‘We do not report the legal status of any student or families togovernment agencies’ (Richardson 1994). While geographically close,in terms of immigration policy, Inglewood’s neutrality contrasts withAnaheim’s restrictions.

The city of Los Angeles offers the most accommodating policyclimate for Tunkasenos. The Board of Education quickly voted to joinlegal action against Proposition 187, for example, as did the citycouncil (Feldman and Connell 1994; Feldman 1995). In 2000, thecouncil also asked the Board of Police Commissioners to bar INS andBorder Patrol agents from Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD)facilities (Keller 2000). One year later, members ordered a tougheningof procedures to protect the rights of unauthorized immigrant crimevictims and, in 2008, the body unanimously approved an ordinance

Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities 1857

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

requiring home improvement stores to develop plans for day labourers(Gorman 2008).

LAPD has also enacted accommodating policies for immigrants.Special Order 40, in place since 1979, prohibits police officers from‘initiat[ing] police action with the objective of discovering the alienstatus of a person’ (OLACP 1979). Under the order, officers are notpermitted to ask about immigration status in the course of interview-ing victims, witnesses or suspects of crimes, and they are banned fromarresting individuals for being in the country illegally. Adopted as away to encourage immigrants to cooperate with LAPD, the policy hasreceived enduring support from Los Angeles’s police chiefs, mayorsand city council, and has successfully weathered several legalchallenges.11At the opposite end of the spectrum from restrictiveAnaheim, Los Angeles’s policies are overwhelmingly inclusive.

From Tlacuitapa to Oklahoma and California

While with the Tunkas data set I compare the local-level settlementbehaviour of immigrants from a new sending community, I use theTlacuitapa data set to analyse the state-level residency of immigrantsfrom a traditional sending village. Four generations of northwardmigration have allowed many Tlacuitapenses to regularize theirimmigration status. Only 9 per cent of the sample is unauthorized(Table 3). In comparison to migrants from Tunkas, Tlacuitapensesalso have more extensive networks attaching them to destinations, withan average of eight family members in the USA. In addition, mostTlacuitapenses (over 75 per cent) view migration as an economicnecessity, a perception that distances them from their community oforigin. With the characteristics of an established immigrant flow

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for Tlacuitapenses, by state of residency

Oklahoma California Other stateVariable (n�114) (n�100) (n�49)

Unauthorized 19% 7% 2%Male 53% 52% 63%Need migration 82% 76% 69%

M

Age (years) 36 40 39Education 12 10 10(years) 9No. of family in USA 8 9 235Wage ($/week) 294 326

N�263

Source: MMFRP

1858 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

working against legislative restrictions, Tlacuitapenses should be lesslikely to be influenced by state-level subnational attrition throughenforcement policy.

Tlacuitapenses cluster primarily in Oklahoma (Oklahoma City) andCalifornia (the Bay Area) � states that have passed contrastingimmigration legislation. In Oklahoma, a series of local restrictionspreTabled a statewide shift towards attrition through enforcement thatculminated in the 2007 Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act, or HouseBill (HB) 1804.12 In order to ‘discourage illegal immigration’, thislegislation’s stated objective, the act limited access to higher education,government identification, public benefits and employment. It pro-hibited in-state tuition for unauthorized students, for example,restricted state identification to legal residents, and included provi-sions against hiring unauthorized workers.13 In addition to declaringthe harbouring, transporting, concealing or sheltering of unauthorizedimmigrants a felony, HB 1804 required jails to determine theimmigration status of suspects charged with felonies and intoxicateddriving, and encouraged Oklahoma’s attorney general to pursue astate-wide 287(g) agreement.14

In California, the other Tlacuitapense destination, several high-profile bills in the 1990s were restrictionist.15 More recently, however,legislation has firmly shifted towards accommodation, providingservices to immigrants regardless of authorization status and expand-ing their legal rights. In 2001, for instance, Assembly Bill 540 allowedunauthorized students to qualify for in-state college tuition. SenateBill 1534 of 2006 extended health care services to non-citizensineligible for federal public assistance, and Assembly Bill 976 of2007 prohibited local governments from inquiring into renters’immigration status. Offering Tlacuitapenses far more inclusive immi-gration policy than Oklahoma, California serves as a contrast case.

Analysis and findings

Tunkaseno settlement in Southern California

Anaheim’s attrition through enforcement-style policies attempt topush immigrants out of the locale. However, because theories ofsettlement emphasize economic and social variables, I hypothesize thatTunkaseno migrants in Anaheim will not demonstrate shortenedsettlement behaviour in comparison to their counterparts in theneutral Inglewood or accommodating Los Angeles. I performstandard multivariate regression, controlling throughout for restrictivedestination, to test this hypothesis. A finding that indicates that theduration of Tunkasenos’ stay in restrictive Anaheim is no longer thanthat of their counterparts in the other two primary destinations will

Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities 1859

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

support the hypothesis, suggesting that settlement is constitutive ofprocesses that have little to do with local attrition through enforcementefforts.

The descriptive statistics for this sample in Table 2 indicate thatTunkasenos across the three receiving locales are quite similar.16 Thedependent variable of this analysis is settlement, measured by theduration of immigrants’ last trip north. The independent variable ofinterest is US destination. I construct a linear scale for this variable,with restrictive Anaheim coded as 2, neutral Inglewood as 1, andaccommodating Los Angeles as 0. Of course, linear measures implysome sort of continuum, such as age or weight, with clearlyfunctioning distances between ordered categories. By applying thisform of measurement to restrictive receiving locales, I force qualitativevariations into a linear scale (see Thurstone and Chave 1929).Nevertheless, the requirements for objective measurement in the socialsciences are predicated on the identification of qualitative differencesbetween individuals � or, in this analysis, immigrant receivingcommunities � and evaluating how to best quantify these differences(Cavanagh 2007). I demonstrate above that the variations of formalrestriction are distinct and unambiguous across destinations and areindeed ordered in terms of the level of restrictive legislation present inthese locales.

In addition to standard demographic measures and documentationstatus, labour market and economic considerations are included in theanalysis with wage and US debt variables. The former reflectsTunkasenos’ weekly wages in dollars, while the latter captures theextent to which migrants owe formal debt in the USA, such as amortgage on a home, car financing or credit card debt. The debtvariable is measured linearly: its absence is scored as 0, whereas oneloan is scored as 1 and two loans are scored as 2. The analysis alsocontrols for networks with a variable that captures the number ofrelatives Tunkasenos have in the USA. Finally, the ‘migration need’variable reflects perceptions of the necessity to migrate north in orderto progress economically. It tests whether positive perceptions of theeconomic advantage of the USA influence settlement. Responses thatmigration is needed are coded as 1.

As expected, in each of the five regression models (Table 4), therestrictive destination variable is not significantly related to length ofresidence for Tunkasenos, indicating that local attrition throughenforcement policy does not drive the duration of immigrant settle-ment.17 Models 2�5 demonstrate that living in a restrictive localeremains an insignificant predictor of settlement when controlling forstandard demographic variables (gender, age, education). Immigrationstatus also fails to predict the duration of time Tunkasenos’ spend intheir US destinations, indicating that unauthorized immigrants do not

1860 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

Table 4. Coefficients for regression of the length of Tunkaseno settlement

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5

Restrictive 9.292 7.725 5.496 5.453 6.461(5.921) (5.735) (5.724) (5.623) (5.413)

Unauthorized �6.360 1.179 2.472 �0.690(13.978) (14.126) (13.968) (13.458)

Female �2.986 �2.891 �2.082 �2.046(9.182) (9.040) (8.885) (8.542)

Age 0.485 0.365 0.347 0.447(0.380) (0.378) (0.372) (0.359)

Years of education 3.891*** 3.413*** 3.450*** 3.527***(0.975) (0.981) (0.966) (0.929)

No. of family in USA 2.901 2.376* 2.628*(1.227) (1.259) (1.213)

Wage ($/week) �0.035* �0.040*(0.018) (0.18)

US debt 16.782 18.874**(9.401) (9.056)

Migration need 32.425***(9.116)

Constant 54.186*** 14.086 8.774 16.616 4.266(8.134) (26.235) (25.926) (25.929) (25.167)

Adjusted R2 0.010 0.092 0.120 0.151 0.215F 2.463 4.045** 4.409*** 4.334*** 5.575***

* pB.05, ** pB.01, *** pB.001

SE shown in parentheses

N�151

Source: MMFRP

Retu

rnto

send

er?A

com

pa

rative

an

aly

siso

fim

mig

ran

tco

mm

un

ities1

86

1

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

settle for shorter periods than their documented counterparts. Thisfinding is supported by the assessment that tough border enforcementpolicies have ironically bottled up unauthorized migrants in the USAdue to the physical risks and increasing cost of illegal crossing(Cornelius 2005).

Model 3 introduces the number of family members in the USA � thenetwork variable � into the regression. While it is not significantpaired with demographic variables, when controlling for economicmeasures (wage and debt) as in Model 4, the variable has a significantand positive relationship with settlement. It remains significant inModel 5, which includes a control for the necessity of migration. Themore family members Tunkaseno migrants have in the USA, then, thelonger the settlement. In this sense, it is possible that the greater levelof whole-family settlement in Anaheim (shown in Table 3 in the sexratio and number of family in the USA) offsets the potential attritioneffect of an exclusionary political environment. The theoreticalliterature on networks reviewed above reinforces this finding of thesocial variables inherent in settlement.

Models 4 and 5 explore the economic drivers of settlement. Here,weekly wages have a negative relationship with settlement. In otherwords, lower income is significantly related to longer trips. This is notaltogether surprising: as members of a relatively new migration flow,many Tunkaseno migrants may see themselves as ‘target earners’ whochoose not to return home without a certain amount of savings. Giventhe high cost of living in Southern California, reaching these goalstakes time. Piore (1979, p. 61) additionally argues that the effect ofrising incomes for target earners is an increase in return migration.The positive significance of the education variable can also beunderstood through employment. Although Tunkasenos, like manynew Mexican migrants, have relatively low levels of education,proficiency in basic skills helps them find work (Wortham, Murilloand Hamann 2002). Finally, settlement is significantly related to debtand the perception that migration is necessary to advance economic-ally, two variables that indicate rootedness in the receiving community.Overall, these findings demonstrate that local attrition throughenforcement policy does not curtail the settlement processes ofTunkaseno migrants.

Tlacuitapense residency in Oklahoma and California

Turning to the state-level comparison between Oklahoma’s restrictiveimmigration policy and California’s more accommodating approach, Ianalyse the experiences of Tlacuitapense migrants. The descriptivestatistics reported in Table 3 demonstrate migrants’ similarity acrossdestination states. The exception is the higher rate of unauthorized

1862 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

Tlacuitapense residence in Oklahoma, although this suits the purposesof the analysis. The key dependent variable here is the state ofimmigrant residence. Due to changes in the survey instrument, this isslightly different than the dependent variable used for the Tunkasenodata set. Nevertheless, it provides a reliable measure of whetherattrition through enforcement policy affects immigrants’ residencybehaviour.

I do not directly test theories of settlement with this data set,although given their emphasis on economic and social processesI hypothesize that restrictive state-level policy will not driveTlacuitapense residency. Migrants’ residency in Oklahoma will showno significant drop after the passage of HB 1804, the state’s attritionthrough enforcement bill. Likewise, residency in accommodatingCalifornia and/or other states will not increase. To evaluate thesehypotheses, I comparatively measure Tlacuitapenses’ state of residencefrom the beginning of 2007, the year Oklahoma’s legislation went intoeffect, through to the end of 2009, when the surveys were conducted.A finding of a similar (or larger) number of Tlacuitapenses inOklahoma post-HB 1804 in comparison to California and other stateswill support these hypotheses, indicating that Oklahoma’s state-levelattrition through enforcement policy had little effect on migrants’residency.

The analysis presented in Figure 2 below demonstrates that, in theyears immediately after HB 1804 went into effect, the Tlacuitapensepopulation in Oklahoma � both legal and unauthorized � actuallyexperienced growth, rather than reduction. This is precisely the oppositefinding that would be expected if attrition though enforcement worked

Figure 2. Number of Tlacuitapenses, by state and immigration status, 2007�9Source: MMFRP

Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities 1863

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

to push immigrants out. The increase in the Oklahoma-basedimmigrant community was slight: in 2007, seventeen unauthorizedTlacuitapenses lived in Oklahoma, whereas in 2008 this number roseto twenty and in 2009 to twenty-two. For immigrants with legal status,eighty-four resided in Oklahoma in 2007, while in 2009 the count rose toninety and in 2009 to ninety-two. During the same time period, however,the overall number of Tlacuitapense inhabitants in California, theaccommodating comparison destination, held constant. In 2007 justeight unauthorized Tlacuitapenses lived on the west coast and in 2008and 2009 there were seven. Documented California-based Tlacuitapensesnumbered ninety-two in 2007 and ninety-three in both 2008 and 2009.

This analysis strongly indicates that Oklahoma’s heavy-handedlegislation did not influence the choices Tlacuitapenses made abouttheir places of residence, nor did it push them towards California, astate with more permissive immigration laws and a large Tlacuitapensecommunity. The economic crisis starting in 2007 hit Californiaparticularly hard, however, and immigrants in the state alreadysuffered from saturated labour markets and a high cost of living(Passel and Zimmermann 2001, pp. 16�20). Given these factors, ifthere were a push effect out of Oklahoma, Tlacuitapenses would likelyavoid the west coast. It is particularly notable, therefore, that they alsodid not move to other states. From 2007 to 2009, only oneunauthorized respondent lived outside of Oklahoma and California.While there was a total of fifty-one Tlacuitapenses living in otherstates in 2007, this population dropped slightly to forty-seven in 2008and forty-nine in 2009.

This finding of an overall lack of immigrant attrition fromOklahoma is reinforced by a report that the Latino student populationin public schools in Oklahoma City and Tulsa rose from 2005 to 2009(Koralek et al. 2010). A study of Oklahoma’s population based oncensus data also supports my analysis, indicating that most Latinosand immigrants have remained in the state despite restrictions(Pedroza 2011). In accordance with labour market and networktheories of settlement, continued immigrant residence in Oklahomais likely driven by employment and social ties.

Without disregarding accounts of fear in Oklahoma’s immigrantcommunities due to HB 1804, the state’s restrictive policy ultimatelydid not persuade Tlacuitapenses to reside elsewhere. Anaheim’s localattrition through enforcement legislation also likely caused alarmamong immigrants, although it failed to curtail the settlement rates ofTunkasenos. These state-level findings, coupled with the local-levelresults, indicate that such subnational policy does not achieve massimmigrant expulsion. Certainly, it is doubtful that these laws areinnocuous. While qualitative methods are better suited to an in-depthexamination of how the policy restrictions of receiving communities

1864 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

affect immigrants’ daily lives, this paper demonstrates a profounddisconnect between the manifest functions, or ‘conscious motivations’,of attrition through enforcement policy and actual immigrantbehaviour (Merton 1949, p. 60�69).

Conclusion

Scholarship on state and local immigration policy revolves around anexploration of the normative tension between different levels ofgovernment that emerges as some subnational authorities move toformulate their own immigration legislation. This literature alsoaddresses why some states and localities become involved in regulatingimmigration. Taken as a collective whole, these analyses point to acomplex structuring of society along the lines of exclusion (Doty 2003).

This paper takes a different but complementary approach bystudying subnational immigration policy from the perspective ofimmigrant communities on the ground. It contributes to the emergingliterature on this topic by comparatively evaluating immigrants’settlement and residency behaviour in destination cities and stateswith contrasting immigration law. In doing so, this study indicates thateconomic forces and social networks root immigrants in particularcommunities despite policy constraints in restrictive destinations.

Some limitations apply to the analysis. First, the data sets are fromrelatively small samples that are not statistically representative oflarger universes of Mexican migrants within the USA. However, ifattrition through enforcement policies have no effect on Tunkasenos’settlement, those highly susceptible to subnational restriction, it isunlikely that other Mexican immigrant groups would register thisresult. Likewise, if exclusionary policy is found to affect Tlacuitapenseresidency, immigrants who are less vulnerable to restriction, a similaroutcome would be expected for Mexican immigrant groups generally.The data sets also consist of immigrants from rural sending commu-nities. It is possible that these migrants are more tied to the specificdestinations where their relationships are concentrated, whereas thebroader, weaker networks of urban migrants could facilitate mobilityin difficult policy conditions (see Hernandez-Leon 2008). Futureresearch could fruitfully compare rural and urban migrants in thisregard, as well as explore factors found in receiving locales, such asimmigrant advocacy organizations and strong co-ethnic communities,which may serve as significant countervailing pressures againstattrition. Finally, the findings may not necessarily pertain to allcontexts, as particular attrition through enforcement policies may bemore successful in influencing immigrants to leave than others.

This study ultimately points to a larger research agenda for scholarsof state and local immigration policy: the question of immigrant

Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities 1865

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

incorporation within restrictive receiving locales. What are the broaderimplications of subnational laws that seek immigrant attrition,particularly if they do not have policy makers’ intended effect onimmigrant settlement and residency? It is possible that these policiessimply have very little impact within immigrant communities, servingas symbolic reminders of a state or locality’s inclination towards theimmigration issue. Alternatively, restrictive policies may cut offmechanisms of incorporation, leaving immigrants isolated within theirdestinations. Moving forward with this line of inquiry requiresethnographically inspired approaches that elaborate the link betweensubnational policy structures and immigrants’ everyday lives.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the helpful comments of DavidFitzGerald, April Linton, Jeff Haydu, John Skrentny and twoanonymous reviewers.

Notes

1. Subnational immigration policies are not limited to the USA. See Penninx et al. (2004),

Alexander (2007) and Garcıa (2007) for European cases and Tsuda (2006) for Japan.

2. For notable exceptions, see Koopmans (2004), Alexander (2007) and Filindra, Garcia

Coll and Blanding (2011).

3. No exhaustive compilation of contemporary local immigration policy exists, although

growth likely parallels or exceeds that at the state level.

4. The MMFRP is a programme of the University of California San Diego’s Center for

Comparative Immigration Studies. Surveying occurred during the sending communities’

annual festivities, when many migrants return home. Researchers also identified respondents

in US destinations through snowball sampling with multiple points of entry (see Cornelius

1982). This data collection approach captures the immigration experiences of entire sending

communities. There is no sampling and no sampling error.

5. Anaheim Council minutes (19 September 1995).

6. Anaheim Council minutes (3 October 1995, 7 November 1995). Congressional Record

142-H2378 (Daily edition 19 March 1996), Congressional Record 142-S4017 (Daily edition

24 April 1996).

7. House of Representatives’ House Report 105�338 (23 October 1997).

8. Officers in Anaheim’s jail are with ICE, which replaced the INS in 2003. They are

present on a part-time basis (Anaheim Public Information Officer, personal interview, 21

March 2011).

9. Anaheim Union High School District Resolution No. 1999/2000-BOT-01.

10. Inglewood Public Information Officer, personal interview, 9 February 2011.

11. Los Angeles Council Resolution 12 June 2007; Sturgeon v. Bratton (2009) 174

Cal.App.4th 1407.

12. In 2006, the town of Oologah passed an ordinance restricting unauthorized immigrant

employment and Tulsa enacted a resolution condemning city contractors’ hiring of

unauthorized migrants (Oklahoma Political News Service 2006; Lassek 2010).

13. The three employment provisions came under preliminary injunction in 2008; two were

overturned in 2010 (Boczkiewicz 2010).

1866 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

14. Nevertheless, only Tulsa has a 287(g) partnership in Oklahoma (ICE 2011a).

15. In addition to Proposition 187 of 1994, in 1996 Proposition 209 eliminated affirmative

action in the admission processes of public institutions, and Proposition 227 of 1998 banned

bilingual education programmes in public schools.

16. The sample is time restricted to reflect only respondents whose last trip north was in

1995 (when Anaheim’s restrictions began) or later. To capture settlement in Anaheim,

Inglewood or Los Angeles, it also reflects immigrants who remained in these destinations

during their last trip.

17. A regression with two dichotomous variables representing Anaheim and Inglewood

that leaves Los Angeles as the reference category yields results similar to those reported in

Table 4: across all models, neither the Anaheim nor the Inglewood variable is significant,

indicating that restrictive policies do not curtail immigrant settlement.

References

ALEXANDER, MICHAEL 2007 Cities and Labour Immigration: Comparing Policy

Responses in Amsterdam, Paris, Rome and Tel Aviv, Aldershot: Ashgate

ALLEGRO, LINDA 2010 ‘Latino migrations to the U.S. heartland: illegality, state

controls, and implications for transborder rights’, Latin American Perspectives, vol. 37, no. 1,

pp. 172�84

BLOCH, ALICE and SCHUSTER, LIZA 2005 ‘At the extremes of exclusion: deportation,

detention and dispersal’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 491�512

BOCZKIEWICZ, ROBERT 2010 ‘HB 1804 appeal denied in part’, Tulsa World, 3 February

CALAVITA, KITTY 1996 ‘The new politics of immigration: ‘‘balanced-budget conserva-

tism’’ and the symbolism of Proposition 187’, Social Problems, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 284�305

CAMAROTA, STEVEN and JENSENIUS, KAREN 2008 Homeward Bound: Recent

Immigrant Enforcement and the Decline in the Illegal Alien Population, Washington, DC:

Center for Immigration Studies

CAPPS, RANDY, et al. 2011 Delegation and Divergence: A Study of 287(g) State and Local

Immigration Enforcement, Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute

CAVANAGH, ROBERT 2007 ‘Measurement issues in the use of rating scale instruments in

learning environment research’, Australian Association for Research in Education, vol. 15, no. 6,

pp. 1�9

COLEMAN, MATTHEW 2007 ‘Immigration geopolitics beyond the Mexico�U.S. border’,

Antipode, vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 54�76

CORNELIUS, WAYNE 1982 ‘Interviewing undocumented immigrants: methodological

reflections’, International Migration Review, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 378�411

*** 1998 ‘The structural embeddedness of demand for Mexican immigrant labor: new

evidence from California’, in Marcelo Suarez-Orozco (ed.) Crossings: Mexican Immigration

in Interdisciplinary Perspectives, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, pp. 113�44

*** 2005 ‘Controlling ‘‘unwanted’’ immigration: lessons from the United States, 1993�2004’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 775�94CORNELIUS, WAYNE et al. (eds) 2004 Controlling Immigration: A Global Perspective,

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press

CORNELIUS, WAYNE et al. (eds) 2010 Mexican migration and the U.S. economic crisis,

La Jolla, CA: CCIS

DELSON, JENNIFER and MEHTA, SEEMA 2007 ‘Anaheim schools trustee is a target of

left and right’, The Los Angeles Times, 3 August

DOTY, ROXANNE 2003 Anti-Immigrantism in Western Democracies � Statecraft, Desire,

and the Politics of Exclusion, New York: Routledge

EVERLY, ALAN 1996 ‘Jail project targets illegal immigrants’, The Los Angeles Times,

26 March

Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities 1867

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

FELDMAN, PAUL 1995 ‘Judge urged to bar public funds from Prop. 187 fight’, The Los

Angeles Times, 17 February

FELDMAN, PAUL and CONNELL, RICH 1994 ‘Wilson acts to enforce parts of

Prop. 187’, The Los Angeles Times, 10 November

FILINDRA, ALEXANDRA 2009 ‘E pluribus unum? Federalism, immigration and the role

of states’, PhD dissertation, Department of Political Science, Rutgers University,

New Brunswick, NJ, USA

FILINDRA, ALEXANDRA, GARCIA COLL, CYNTHIA and BLANDING, DAVID 2011

‘The power of context: state-level immigration policy and differences in the

educational performance of the children of immigrants’, Harvard Educational Review, vol. 81,

no. 3, pp. 407�38

FITZGERALD, DAVID, ALARCON ACOSTA, RAFAEL and MUSE-ORLINOFF,

LEAH (eds) 2011 Recession without Borders: Mexican Migrants Confront the Economic

Downturn, La Jolla, CA: CCIS

FIX, MICHAEL and PASSEL, JEFFREY 1994 Immigration and Immigrants: Setting the

Record Straight, Washington, DC: The Urban Institute

FLEURY-STEINER, BENJAMIN and LONGAZEL, JAMIE 2010 ‘Neoliberalism, com-

munity development, and anti-immigrant backlash in Hazleton, Pennsylvania’, in Monica

Varsanyi (ed.), Taking Local Control: Immigration Policy Activism in U.S. Cities and States,

Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 157�72

FURUSETH, OWEN and SMITH, HEATHER 2010 ‘Localized immigration policy: the

view from Charlotte, North Carolina, a new immigrant gateway’, in Monica Varsanyi (ed.),

Taking Local Control: Immigration Policy Activism in U.S. Cities and States, Stanford, CA:

Stanford University Press, pp. 173�92

GARCIA, ANGELA S. 2007 ‘Internalizing immigration policy within the nation-state: the

local initiative of Aguaviva Spain’, Working Paper 151, San Diego, CA: Center for

Comparative Immigration Studies

GORMAN, ANNA 2008 ‘Day labor laws OKd’, The Los Angeles Times, 14 August

HERNANDEZ-LEON, RUBEN 2008 Metropolitan Migrants: The Migration of Urban

Mexicans to the United States, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

ICE (IMMIGRATION AND CUSTOMS ENFORCEMENT) 2011a Fact Sheet: Delega-

tion of Immigration Authority Section 287(g) Immigration and Nationality Act. Available

from: http://www.ice.gov/news/library/factsheets/287g.htm [Accessed 25 May 2012]

*** 2011b Activated Jurisdictions. Available from: http://www.ice.gov/doclib/secure-

communities/pdf/sc-activated.pdf [Accessed 25 May 2012]

IPD (INGLEWOOD POLICE DEPARTMENT) 2008 Approval of Agreement with the

United States Department of Homeland Security Immigration and Customs Enforcement

Agency for Reimbursement of Police Overtime Expenses. Available from: http://www.

cityofinglewood.org/AgendaStaffReports/01-15-08/4.pdf [Accessed 25 May 2012]

INEGI (INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ESTADISTICA Y GEOGRAFIA) 2005 Censo

General de Poblacion y Vivienda

KELLER, LOREN 2000 ‘New Coalition calls for repeal of Special Order 40’, City News

Service, 19 April

KOBACH, KRIS 2004 State and Local Authority to Enforce Immigration Law: A Unified

Approach for Stopping Terrorists, Washington, DC: Center for Immigration Studies

KOOPMANS, RUUD 2004 ‘Migrant mobilisation and political opportunities: variation

among German cities and a comparison with the United Kingdom and the Netherlands’,

Journal of Ethnic Migration Studies, vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 449�70

KORALEK, ROBIN, PEDROZA, JUAN and CAPPS, RANDY 2010 Untangling the

Oklahoma Taxpayer and Citizen Protection Act: Consequences for Children and Families,

Washington, DC: Urban Institute

KRIKORIAN, MARK 2005 Downsizing Illegal Immigration: A Strategy of Attrition through

Enforcement, Washington, DC: Center for Immigration Studies

LASSEK, P. J. 2010 ‘Tulsa councilor proposes immigration ordinance’, Tulsa World, 23 May

1868 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

LOFSTROM, MAGNUS, BONN, SARAH and RAPHAEL, STEVEN 2011 ‘‘Lessons from

the 2007 Arizona Workers Act’’, San Francisco, CA: Public Policy Institute of California

MARTOS, SOFIA 2010 ‘Coded codes: discriminatory intent, modern political mobilization,

and local immigration ordinances’, New York University Law Review, vol. 85, no. 6, pp.

2099�137

MASSEY, DOUGLAS 1986 ‘The settlement process among Mexican migrants to the United

States’, American Sociological Review, vol. 51, no. 5, pp. 670�84

MASSEY, DOUGLAS, et al. 1987 Return to Aztlan: The Social Process of Migration from

Western Mexico, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press

MASSEY, DOUGLAS, et al. 1998 Worlds in Motion: Understanding International Migration

at the End of the Millennium, Oxford: Oxford University Press

MERTON, ROBERT 1949 Social Theory and Social Structure, Chicago, IL: Free Press

MOTAMURA, HIROSHI 1990 ‘Immigration law after a century of plenary power’, Yale

Law Journal, vol. 100, no. 3, pp. 545�613

NCSL (NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF STATE LEGISLATURES) 2011 State Laws

Related to Immigration and Immigrants. Available from: http://www.ncsl.org [Accessed 25

May 2012]

OKLAHOMA POLITICAL NEWS SERVICE 2006 ‘Oolagah passes tough immigration

ordinance’, Oklahoma Political News Service, 3 October. Available from: http://www.okpns.

com/2006/10/03/oologah-passes-tough-immigration-ordinance/ [Accessed 14 June 2012]

OLACP (OFFICE OF THE LOS ANGELES CHIEF OF POLICE) 1979 Special Order 40.

Los Angeles, CA: OLACP

OLIVAS, MICHAEL 2007 ‘Immigration-related state and local ordinances: preemption,

prejudice and the proper role for enforcement’, University of Chicago Legal Forum, pp. 27�56

PASSEL, JEFFREY and ZIMMERMANN, WENDY 2001 ‘Are immigrants leaving

California? Settlement patterns of immigrants in the late 1990s’, Washington, DC: The

Urban Institute

PEDROZA, JUAN 2011 ‘Mass exodus from Oklahoma? Immigrants and Latinos stay and

weather a state of capture’, Journal of Latino-Latin American Studies, vol. 4, no. 1, pp. 1�15

PENNINX et al. (eds) 2004 Citizenship in European Cities: Immigrants, Local Politics and

Integration Policies, Aldershot: Ashgate

PHAM, HUYEN 2004 ‘The inherent flaws in the inherent authority position: why inviting

local enforcement of immigration laws violates the Constitution’, Florida State University

Law Review, vol. 31, no. 4, pp. 965�1003

PIORE, MICHAEL 1979 Birds of Passage: Migrant Labor and Industrial Societies,

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

RAMAKRISHNAN, KARTHIC and WONG, TOM 2010 ‘Partisanship, not Spanish:

explaining municipal ordinances affecting undocumented immigrants’, in Monica Varsanyi

(ed.), Taking Local Control: Immigration Policy Activism in U.S. Cities and States, Stanford,

CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 73�96

RICHARDSON, LISA 1994 ‘Prop. 187 battle has spurred teenagers to activism’, The Los

Angeles Times, 24 November

SACCHETTI, MARIA 2001 ‘Trustee wants to tell INS on students’, The Orange County

Register, 24 October

SEGHETTI, LISA, ESTER, KARMA and GARCIA, MICHAEL JOHN 2009 Enforcing

Immigration Law: The Role of State and Local Law Enforcement, Washington, DC:

Congressional Research Service Report for Congress

SKERRY, PETER 1995 ‘Many borders to cross: is immigration the exclusive responsibility

of the federal government?’, Publius, vol. 25, no. 3, pp. 71�85

SPIRO, PETER 1994 ‘The states and immigration in an era of demi-sovereignties’, Virginia

Journal of International Law, vol. 35, pp. 121�78

STATE OF ARIZONA 2010 Senate Bill 1070

STATE OF CALIFORNIA 1862 Chinese Police Tax

Return to sender? A comparative analysis of immigrant communities 1869

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14

THURSTONE, LOUIS and CHAVE, ERNEST 1929 The Measurement of Attitude,

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

TSUDA, TAKEYUKI (ed.) 2006 Local Citizenship in Recent Countries of Immigration:

Japan in Comparative Perspective, Lanham, MD: Lexington Books

VARSANYI, MONICA 2010 ‘Immigration policy activism in U.S. states and cities:

interdisciplinary perspectives’, in Monica Varsanyi (ed.), Taking Local Control: Immigration

Policy Activism in U.S. Cities and States, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 1�11

VAUGHAN, JESSICA 2006 Attrition through Enforcement: A Cost-Effective Strategy to

Shrink the Illegal Population, Washington, DC: Center for Immigration Studies

WISHNIE, MICHAEL 2001 ‘Laboratories of bigotry?: Devolution of the immigration power,

equal protection, and federalism’, New York University Law Review, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 493�569

WORTHAM, STANTON, MURILLO, ENRIQUE, JR, and HAMANN, EDMUND (eds)

2002 Education in the New Latino Diaspora: Policy and the Politics of Identity, Westport, CT:

Ablex Publishing

ZOLBERG, ARISTIDE 2006 A Nation by Design: Immigration Policy in the Fashioning of

America, New York: Russell Sage Foundation

ANGELA S. GARCIA is a PhD candidate in the Department ofSociology at the University of California, San Diego.ADDRESS: Department of Sociology, UCSD, 9500 Gilman Drive,La Jolla CA 92093-0533, USA.Email: [email protected]

1870 Angela S. Garcıa

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Nor

th D

akot

a St

ate

Uni

vers

ity]

at 2

0:00

16

Nov

embe

r 20

14