Research | Berkeley Social Welfare

Transcript of Research | Berkeley Social Welfare

Cultural Attitudesand Caregiver Service Use

Lessons from Focus Groups with Raciallyand Ethnically Diverse Family Caregivers

Andrew E Scharlach PhDRoxanne Kellam MSNatasha Ong MSWAeran Baskin BA

Cara Goldstein MSWPatrick J Fox PhD

ABSTRACT Focus groups were conducted with caregivers from eightracial-specific or ethnic-specific populations (African Americans Chi-nese Filipinos Hispanics Koreans Native Americans Russians andVietnamese) to examine cultural variations in caregiving experiences

Andrew E Scharlach Roxanne Kellam Natasha Ong Aeran Baskin and CaraGoldstein are affiliated with the Center for the Advanced Study of Aging ServicesSchool of Social Welfare University of California-Berkeley Patrick J Fox is affiliatedwith the Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences University of California-SanFrancisco

Address correspondence to Andrew E Scharlach School of Social Welfare Univer-sity of California Berkeley 120 Haviland Hall Berkeley CA 94720-7400 (E-mailScharlachberkeleyedu)

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Steven Williams who assistedwith data coding Barbara Sirotnick Sheldon Bockman and Max Neiman of the InlandEmpire Resource Consortium the students faculty and staff who facilitated the focusgroups and the 76 family caregivers who shared their personal experiences and per-spectives

This research was supported by the California Department of Aging and the KleinerFamily Foundation

Journal of Gerontological Social Work Vol 47(12) 2006Available online at httpwwwhaworthpresscomwebJGSW

copy 2006 by The Haworth Press Inc All rights reserveddoi101300J083v47n01_09 133

care-related values and beliefs care practices and factors contributingto decisions about the use of caregiver support services Analysis of fo-cus group transcripts revealed three cross-cutting constructs familismgroup identity and attitudinal and structural barriers to service use Wediscuss these findings in terms of their implications for existing knowl-edge regarding family responsibility resource utilization and programdevelopment for racially and ethnically diverse family caregivers [Arti-cle copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service1-800-HAWORTH E-mail address ltdocdeliveryhaworthpresscomgt WebsitelthttpwwwHaworthPresscomgt copy 2006 by The Haworth Press Inc All rightsreserved]

KEYWORDS Family caregiving focus groups cultural diversity ser-vice use

Despite demanding care situations (Aranda amp Knight 1997 NACAARP 2004 Navaie-Waliser et al 2001) and related caregiver strain(Adams et al 2002 Aranda et al 2003 Cox amp Monk 1990 HarwoodBaker Cantillon Lowenstein Ownby amp Duara 1998 Markides et al1997 Connell amp Gibson 1997 NACAARP 2004 Adams et al 2002Lee amp Sung 1998) minority caregivers tend to use formal support ser-vices substantially less than their non-Hispanic White counterparts(Dilworth-Anderson et al 2002 Dunlop et al 2002 Mausbach et al2004 Tennstedt amp Chang 1998 White-Means amp Thornton 1996)

Low service use among minority ethnic caregivers is of particularconcern because it has been associated with unmet needs for assistanceand support Caregivers from African American Latino Asian and Pa-cific Island populations consistently express a greater need for formalsupport services and higher levels of unmet social and mental healthneeds than do non-Hispanic White caregivers (Cox 1999 Hinrichsen ampRamirez 1992 NACAARP 2004 Wallace amp Lew-Ting 1992 Ho etal 2000)

The reasons for the apparent underutilization of caregiver servicesamong non-White and Hispanic populations are not well understoodEfforts to explain restricted service use among caregivers from racialand ethnic minority groups have typically relied on correlational datamost often from African American caregivers (Ajrouch Antonucci ampJanevic 2001 Connell amp Gibson 1997 Dilworth-Anderson et al

134 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

2002) who apparently are substantially more likely to use support ser-vices than are other racial and ethnic groups

Culturally-defined values norms and roles have been identified asmajor determinants of the caregiving experience and are likely to affectservice utilization Familism a primary value of Latino cultures is of-ten cited as a motivating factor for providing care (Becker BeyeneNewsom amp Mayen 2003) including the expectation that extended familywill assist with the care of older relatives (Cox amp Monk 1993 Clark ampHuttlinger 1998) Closely linked to familism are the concepts of mutualsupport reciprocity (giving back love and support to family memberswho have given the same) filial obligation and respect shown for anolder relativersquos worthiness and authority (Nkongo amp Archbold 1995Giunta et al in press Ishii-Kuntz 1997 Connell amp Gibson 1997)

Several studies have linked the availability of informal support to re-duced use of formal services (Strain amp Blandford 2002 KosloskiMontgomery amp Youngbauer 2001 Horowitz 1998) The majority ofexisting research suggests that ethnic minority caregivers have wider andstronger informal support networks than White caregivers (Aranda ampKnight 1997 Connell amp Gibson 1997 Dilworth-Anderson et al2002 Mui Choi amp Monk 1998 Smerglia Deimling amp Barresi 1998Giunta et al in press) Other evidence suggests that informal supportmay not always be so available for Hispanic and non-White caregiversPhillips and colleagues (2000) found that Mexican American caregivershad smaller social support networks and received significantly less sup-port than did non-Hispanic White caregivers Youn and colleagues(1999) found that Korean American caregivers primarily daughters re-ported having less social support than White caregivers

Caregivers from racial and ethnic minority groups also may be espe-cially likely to experience structural barriers to service utilization in-cluding inadequate transportation insufficient knowledge aboutservices cost of services language barriers negative prior experienceswith services and lack of culturally-sensitive services (Damskey 2000Mui et al 1998 Toseland McCallion Gerber and Banks 2002 GillHin- richsen amp DiGiuseppe 1998 Williams and Dilworth-Anderson2002 Dilworth-Anderson et al 2002 Levkoff Levy amp Weitzman1999 Giunta et al in press)

As the ethnic and cultural diversity of the United Statesrsquo populationincreases so does the need to understand the reasons for the underutili-zation of formal services by ethnic minority caregivers Hypotheses toexplain observed patterns of low formal service use have included fam-

Scharlach et al 135

ily-centered cultural norms greater informal support and structuralbarriers to service use However studies to date have been based pri-marily on information from individuals already receiving services andhave provided only limited guidance regarding the perspectives of care-givers from a wide range of racial and ethnic minority groups Little isknown about caregiversrsquo own experiences and attitudes about serviceuse from their own cultural perspectives and in their own languagesEspecially lacking is information from Asian and Pacific Island care-givers the groups least likely to use formal support services

This study examines reasons for restricted service use among care-givers from eight racial and ethnic minority groups Particular attentionis given to commonalities in the experiences of caregivers from diversegroups regarding their family care responsibilities the role of currentinformal and formal supports and the potential utility of desired sup-ports

METHODS

Racial-specific and ethnic-specific caregiver focus groups wereheld to examine cultural variations in the family caregiving experi-ence and to identify factors contributing to decisions about the use ofcaregiver support services among each of the eight non-White popu-lations with the greatest representation in California (US Census2000) African-Americans Chinese Filipinos Korean Native Ameri-cans Hispanics Russian and Vietnamese Focus groups are in-depthopen-ended facilitator-moderated group discussions of one to twohours duration that explore a specific set of issues on a predefined andlimited topic (Robinson 1999) Focus groups have been found to bean effective way to ldquoobtain data about feelings and opinions from asmall group of participants about a given problem experience serviceor other phenomenonrdquo (Leung Wu Lue amp Tang 2004) especially inorder to provide insight from socially marginalized groups regardingspecific phenomena that have emerged in existing data (Hudson ampMcMurray 2002 Kidd amp Parshall 2000)

Focus Group Recruitment

Focus group participants were recruited through community organi-zations serving each of the eight racial or ethnic populations (AfricanAmerican Chinese Filipino Korean Native American Hispanic Rus-

136 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

sian and Vietnamese) three in the San Francisco Bay Area one in Sac-ramento one in Los Angeles and three in outlying areas of SouthernCalifornia These organizations included community centers (eg theAsian Community Center the Filipino American Council First NationsTribal Family Center) churches health clinics senior services agen-cies and local Area Agencies on Aging (AAA) Most of the organiza-tions chosen did not already have programs explicitly targeted tocaregivers and efforts were made to recruit individuals who were notnecessarily already utilizing caregiver support programs Focus groupparticipants were recruited through posted fliers and personal contactwith organization members or consumers and received $5000 for theirparticipation

Participant Characteristics

A total of 76 individuals participated in the eight focus groups fromsix participants in the Hispanic group to 12 in the African-American andVietnamese groups (see Table 1) Participants ranged in age from theirearly 20s to their early 70s approximately two-thirds were women Themajority of participants were providing care to an elderly parent withsmaller numbers caring for spouses other family members neighborsor friends

Procedure

Focus groups lasted approximately two hours and were conducted inthe preferred language of the participants The focus groups were facili-tated by graduate students staff and faculty members from the Universityof California at Berkeley and California State University San BernardinoThe facilitators were matched to the language ethnicity and culturalbackgrounds of each group and received training in conducting focusgroups from experienced practitioners Focus group moderators followeda semi-structured discussion guide translated as necessary which in-cluded the following primary prompts

bull For whom do participants provide carebull How do participants view their role as a care providerbull What has the experience of providing care been like for them and

(how) is that affected by their race or ethnicitybull Where do participants turn for support and assistancebull What would they ideally like from a caregiver support agency

Scharlach et al 137

These questions were used to promote open discussion among theparticipants regarding their experiences as care providers and were ac-companied by specific follow-up prompts as needed The focus groupswere audiotaped and at least one note taker was present at each session

Analysis

Following each group meeting the moderator and note taker brieflydiscussed the group process and then each separately prepared aone-page summary of their impressions All materials from the eightgroups including tapes transcripts notes and summaries were sub-mitted to the research team for analysis

Based on the structure of the discussion guide and a preliminary re-view of focus group materials nine general categories were identified

138 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

TABLE 1 Focus Group Participants

Focus Group ofparticipants

Agerange

Gender Care recipient

African-Americans 12 20-70 10 female2 male

Parent-8Aunt-2Grandmother-1Daughter-1

Chinese 8 30-70 4 female4 male

Spouse-1Parent-4Aunt-1Multiple persons-1Unknown-1

Filipino 9 30-60 7 female2 male

Spouse-3Parent-1Aunt -1Friend-3Overlaps-1

Korean 9 25-65 4 female5 male

Parent-8Brother-1

Native American 11 30-60 6 female5 male

Parent-4Grandmother-2Unknown-5

Hispanic 6 20-25 3 female3 male

Parent-1Grandparent-3Neighbor-2

Russian 9 40-60 7 female2 male

Spouse-1Parent-7Son-1

Vietnamese 12 28-61 9 female3 male

Parent-11Friend-1

for organizing the data positive aspects of the caregiving experiencenegative aspects of the caregiving experience racialethnic group mem-bership informal support formal support suggestions for improvingformal support characteristics of ideal agencies policy recommenda-tions and other points important to participants Two coders independ-ently reviewed all raw data and identified key issues from each focusgroup corresponding to each of these nine categories Where differ-ences in issues were found the coders discussed and resolved any dis-crepancies

Research analysts then prepared summaries of data from each focusgroup contextualizing the categorized issues with additional informa-tion regarding group location and logistics descriptions of participantsand their care recipients caregiving experiences sources of supportand recommendations for programs services and policies The PI andthree research analysts then reviewed the summaries and other availableinformation and independently identified major themes that appearedthroughout the eight focus groups in each of three general areas experi-ences providing care attitudes and experiences with informal supportnetworks and attitudes and experiences with formal support servicesThe identified themes and examples illustrating each of them were dis-cussed among the four analysts until there was agreement on a commonset of nine cross-cutting themes These nine themes which are de-scribed in the following section were then grouped into three overarch-ing constructs (1) familism (2) group identity (3) service barriers

FINDINGS

Familism

Family-oriented themes emerged consistently throughout the eightfocus groups contextualizing the caregiving experience within fam-ily-centered cultural traditions and interpersonal impacts of providingcare Two primary themes related to the overarching construct offamilism emerged (1) cultural norms and traditions underlying the de-cision to provide care (2) personal and interpersonal fulfillment associ-ated with fulfilling those norms and traditions

Cultural Determinants of Caregiving Responsibilities

In describing their motivations for providing care focus group par-ticipants consistently identified longstanding cultural traditions that de-fined their family obligations Caring for ill or disabled family members

Scharlach et al 139

was seen as a responsibility that fulfilled cultural norms maintainedcultural continuity and strengthened family ties Caregiving was de-scribed as something that just needed to be donendashnot merely the ldquocor-rectrdquo thing to do but the ldquoonlyrdquo thing to do

The cultural context of caregiving was articulated especially clearlyby one African-American focus group participant ldquoMinority groupshave more cultural emphasis on caring for their own people It providesstronger family ties and thatrsquos what allows me to do it as part of thecommunity part of the culturerdquo Many other participants in the Afri-can-American group also expressed the view that family members areexpected to provide whatever care is necessary no matter what the carerecipientrsquos needs or circumstances A Chinese participant said ldquothere isa sense of tradition to take care of your parents the Chinese usuallytake care of their ownrdquo Vietnamese participants described caregivingas a family affair with everyone sharing in the care responsibilities

The benefits of maintaining continuity with onersquos cultural traditionswere cited by participants in a number of focus groups One Russiancaregiver commented ldquoWe did it in Russia and we continue doing ithere I had wonderful parents and I do what they didndashtaking carerdquoMany of the Native American participants said that caregiving served asan example to other family members and allowed the caregiver to passdown their Native American traditions and values from one generationto the next

Caregiving as a Source of Fulfillment

Rather than being seen as a burden caregiving was described mostoften as a source of personal satisfaction and emotional fulfillment as aresult of helping family members in their time of need fulfilling cul-tural norms and bringing family members closer together

Many of the Russian-speaking participants for example shared pos-itive emotions about providing care They expressed feelings of happi-ness and joy saying that they were very thankful for the opportunity tohelp family members something that they considered a positive role inthe Russian culture Many of the Chinese caregivers also talked abouthow fulfilling it was to provide help One of the Chinese caregiverscommented that being able to help the care recipient provided ldquoa happi-ness that money canrsquot buyrdquo Making the care recipient happy was a par-ticular source of satisfaction and fulfillment in spite of the workinvolved

140 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

African-American focus group participants voiced similar positiveviews of caregiving referring to the good feelings associated with help-ing someone in need and the opportunity to become closer to relativesOne participant who had been providing care for five years summarizedher feelings by saying simply ldquocaregiving is a blessingrdquo Another par-ticipant described the challenges of providing care to family memberswho are dying but focused on the fulfillment that comes when ldquoyouknow that you were there [and] you know that you did your partrdquo

Group Identity

Cultural variations in the caregiving experience associated withmembership in a particular racial or ethnic group were another major fo-cus of discussion among focus group participants Three primarythemes related to the construct of group identity emerged (1) group-re-lated experiences of adversity and discrimination which affected thecaregiving experience (2) caregiving behaviors and norms which dif-ferentiated onersquos own group from the majority culture (3) transitions inonersquos group identity and cultural context which impacted the availabil-ity of natural support networks

Group Experiences with Adversity

Many participants indicated that their experience as a caregiver wasimpacted by adversity experienced currently or historically by their cul-tural group including discrimination prejudice dislocation or othertypes of hardship the group had faced collectively For example partici-pants in the Native American group discussed at length the hardshipsthat Native Americans have endured including a history of discrimina-tion poverty isolation and displacement they indicated that these ex-periences have resulted in an aggregate distrust of government and thedominant culture and a reluctance to utilize caregiver support servicesAfrican-American participants described how racism and low socio-economic status have hindered their ability to obtain needed servicesand also made it difficult for them to have sufficient resources to pro-vide adequate support to their care recipients

Group experiences with adversity were perceived as impactingcaregiving in some positive ways as well Many participants describedhow their personal and historical experiences of adversity had broughtthem closer together as a family or as a community In addition someparticipants indicated that dislocation and other hardships had made

Scharlach et al 141

them more sensitive to the needs of others and more committed to pro-viding care to persons who needed help Group experiences with adver-sity also affected service utilization as will be discussed under theconstruct of service barriers

Us versus Them

One issue that emerged consistently among all caregiver groups wasa sense that onersquos own cultural community differed from the majorityculture in the United States with regard to the ways in which they pro-vide care or treat their elderly members For example Hispanic care-givers clearly differentiated themselves from Anglos who were per-ceived as abandoning the care and protection of their loved ones into thehands of strangers in order to rid themselves of the burden of care ldquoImean hey you take care of your parents they live with you the wholehuge family is living together It seems like Anglo families want to getgrandma off into the nursing home where [they] donrsquot have to be both-ered with herrdquo Another participant said ldquoWe canrsquot just put them some-where else thatrsquos the way we were brought uprdquo

Vietnamese participants believed that providing care for familymembers was more important in their culture than in the Caucasian cul-ture reflecting strong family values not shared by the majority cultureRegarding the importance of caregiving in the African-American cul-ture one Africa- American participant had this to say ldquoWe shouldnrsquot belike white people where the job is more important than our relativesrdquo

Cultural Norms in Transition

Another issue raised in many of the focus groups was the sense thatchanges were taking place in their cultural communities that impactedthe availability of support for older adults and their caregivers Partici-pants in the Chinese and Korean groups cited changes in cultural normsthat they attributed to the acculturation of later-born cohorts In the Chi-nese group participants worried that American-born Chinese would nothave a sense of filial piety in caring for their elders and not fulfill tradi-tional family obligations One participant said ldquoThere is a sense of tra-dition to take care of your parents but it is uncertain whether yourchildren would do the same for yourdquo Participants of the Korean groupalso voiced similar concerns about whether or not the younger genera-tion would take care of them Older participants expressed the concernthat younger Koreans might have a different conception of caregiving

142 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

responsibilities especially with regard to living arrangements Youngerparticipants did not view living with the care recipient as necessarywhile the older participants perceived this to be an important part of thecaregiving role

African-Americans and Native-Americans perceived their groups asones undergoing significant changes as well Participants in the Afri-can-American group indicated that drugs and violence have contributedto a lack of unity in the African-American community affecting familycohesiveness and the availability of support for caregivers from withinthe African-American family and outside of it The Native Americanparticipants also described how traditional Native American family val-ues have changed as the tribes have become more and more decentral-ized

Service Barriers

Focus group participants reported very limited use of existing formalsupport services Themes that emerged regarding the limited use of out-side services included the following (1) reliance on informal supportnetworks rather than formal services (2) lack of knowledge of availableservices (3) mistrust of formal service providers (4) unavailability ofculturally appropriate services

Utilization of Informal vs Formal Supports

When caregivers needed help they turned primarily to family andfriends with limited reliance on secondary informal support networksand minimal use of formal support services For example participantsin the Chinese Filipino and Vietnamese groups relied primarily onfamily members for assistance seldom mentioning other informal net-works or their cultural community as a source of support with caregiv-ing One Vietnamese participant was part of a seven-member familywith each person appointed a certain service in caring for their motherParticipants in the African-American group also emphasized the impor-tance of family when caring for loved ones but extended it to includekinship networks and non-blood relations They indicated that it wasimportant that families maintain the primary responsibility of caring forill family members instead of employing outside services

Hispanic caregivers preferred to keep caregiving within the familyhowever because these caregivers in a rural area they often relied onneighbors simply because there was no one else around As a result

Scharlach et al 143

neighbors sometimes became as close as family members As one par-ticipant said ldquoWell in my neighborhood we are all pretty close and weare all pretty much like family They will come by and visit They pro-vide a good lift I mean we donrsquot really ask them to but they provide agood liftrdquo

Social cultural and religious organizations were identified assources of informal support for caregivers in a few of the focus groupsSome of the Hispanic Filipino and African-American caregivers iden-tified the church as a major source of emotional or spiritual support Na-tive American caregivers frequently turned to tribal organizationsMany of the Filipino caregivers described attending social clubs fordancing recreation and companionship Some of the Korean partici-pants turned to Korean community organizations such as the KoreanHealth Information Center for services designed to assist the care re-cipient

Overall the ethnic minority caregivers were low users of formal sup-port services Other than a few participants in the African-Americangroup who reported using caregiver information and respite programsthe only services mentioned by focus group participants were directedat the elderly care recipients rather than the caregivers themselves Al-though Chinese caregivers reported relying mostly on their children andother family members as their primarily source of support in helping totake care of the care recipient a few had used formal services such asIHSS Meals-on-Wheels Paratransit or Adult Day Care Some African-American caregivers had used Meals-on-Wheels or the statersquos In-HomeSupportive Services program (IHSS) Some of the Russian caregiversreported that their care recipients attended an Adult Day Health Care(ADHC) or a Regional Center program for persons with developmentaldisabilities Some Vietnamese participants reported using IHSS but noother services Some Hispanic participants had looked into gettingIn-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) but had become discouraged as aresult of burdensome paperwork and no assurance of eligibility

In describing the kinds of services they might find helpful (ie ldquotomake it easier for you to provide care alleviate strain or otherwise im-prove your caregiving situationrdquo) participants typically described ser-vices to alleviate the needs of the care recipient seldom mentioningtheir own concerns and needs Even when asked for recommendationsfor an ideal support program for caregivers most of the recommenda-tions concerned services for the care recipient rather than the caregiverThe lack of a clear differentiation of care recipient and caregiver needs

144 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

was especially apparent in the focus groups with Filipino Chinese Na-tive American and Korean participants

Lack of Knowledge

Focus group participants indicated that lack of knowledge aboutavailable services contributed to their limited use of formal support ser-vices The Chinese caregivers were the only participants who wereaware of an extensive range of formal services designed to help olderpersons such as the statersquos In-Home Supportive Services programMeals-on-Wheels Lifeline Adult Day Care and Paratransit and theyalso seemed the most up-to-date regarding relevant state budget andpolicy issues program funding sources and service criteria The Afri-can-American and Korean participants were aware of a limited numberof services and used these services only when necessary as notedabove In addition a number of African-American participants knewhow to obtain additional information and referrals from their local AreaAgency on Aging (AAA) if needed

Participants in the remaining five focus groups reported not beingaware of many formal services None of the Native American Filipinoor Russian participants were aware of what services existed for them-selves or for the care recipient nor did they know how to access this in-formation Participants in the Vietnamese group did not know about anyservices other than IHSS for their care recipients The Hispanic care-givers seemed to know that information about needed support serviceswas ldquoout there somewhererdquo but did not know how to access it Somedid not even know how to apply for Medi-Cal for themselves or theircare recipients

Mistrust

One reason given for low service use was mistrust of formal serviceproviders Many focus group participants felt that they could not trustnon-family members to care for their care recipients Many of the Fili-pino participants for example did not want to employ outside help be-cause they felt that it was ldquotoo dangerousrdquo As one participant in theKorean group said ldquoI want to take care of my mother and mother-in-lawmyself particularly if they become ill because I couldnrsquot trust them inother peoplersquos hands Nursersquos aides donrsquot even understand Korean anddonrsquot really carerdquo

Scharlach et al 145

For Native American participants avoidance of formal services wasrooted primarily in a mistrust of government agencies As one NativeAmerican participant explained ldquoA hundred years ago they (Americansof European origin) were the conquerors and slaughtered us Eachone of us can tell of somebody that has been attacked by this dominantculture so it says something about not wanting to trustrdquo

Services Unavailable or Inappropriate

Another reason frequently given for not using services was that ser-vices were either not available or not culturally appropriate For manyof the ethnic minority groups available services were considered inap-propriate or inaccessible because of problems such as language barrierslack of culturally-specific services or economic barriers Services espe-cially desired included care training and respite

Language barriers were identified frequently as an obstacle to serviceutilization Participants in the Chinese group for example complainedof substantial difficulty finding local community organizations wherestaff members spoke Cantonese consequently many of these care-givers felt discouraged to even apply for services Participants in theRussian and Vietnamese also expressed frustration about the lack of in-formation and services in their native languages

Many participants said that the lack of culturally-specific serviceswas another barrier to service use Hispanic caregivers were especiallyvocal in describing the need for care systems based on Mexican culturaltraditions of family care rather than apparent Anglo patterns of formalcare provision Participants in the Native American African-Americanand Vietnamese groups also expressed the notion that their issues andconcerns were different from those of the dominant culture and thatcommunity agencies needed to reflect the special needs of their groupNative American participants for example felt that existing serviceproviders did not and could not understand their special needs and theywanted to see the services provided by people like themselves Chineseparticipants also indicated that services would be more useful if theywere more tailored to care recipientsrsquo cultural traditions such as havingan option of getting Chinese food with Meals-on-Wheels instead of thetypical American dishes usually provided by the program

Economic factors were another barrier to service use Financial bur-dens associated with caregiving were a recurrent theme in all of the fo-cus groups and mentioned by every participant in the Hispanic groupAfrican-American caregivers emphasized that services should be more

146 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

affordable and that more monetary support should be provided to care-givers to ease the financial strain placed on these families Filipino care-givers desired financial aid from service providers as well as monetarysupport from the government Reimbursement for home care includingsalary and health benefits for family caregivers was seen as particularlyimportant by participants in the Hispanic and Vietnamese groups

Focus group participants also noted the need for training in order tobetter fulfill their care responsibilities African-American caregiversfor example indicated that training could enable them to provide bettercare and be less reliant on outside assistance Chinese and Vietnameseparticipants identified the need for training classes as well as counselingregarding how to provide better care Russian participants indicated thata 1-3 day training course for caregivers would be ideal Korean partici-pants indicated that training for service providers also would be helpfulparticularly with regard to eligibility program availability and Koreanlanguage and culture

Participants in a number of groups mentioned the need for respitecare Hispanic caregivers while adamant about not wanting to rely onformal services said that they would welcome having someone for acouple of hours per day to help the care recipient with basic necessitiessuch as cleaning cooking helping with bathing and dressing or trans-

Scharlach et al 147

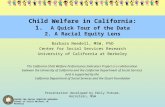

Cultural Norms andTraditionsPersonal andInterpersonal Fulfillment

Familism

TheCaregiver

GroupIdentity

ServiceBarriers

Group Experiencesof Adversity andDiscriminationldquoUs vs ThemrdquoPerspective

Cultural Norms inTransition

Reliance on InformalSupport NetworksLack of Knowledge ofAvailable ServicesMistrust of FormalService ProvidersLack of Culturally-Appropriate Services

FIGURE 1 Themes Identified by Family Caregivers

portation so that the caregiver could have a break Russian and Viet-namese caregivers also said that they would benefit from a break for afew hours or a few days a week For the Chinese participants an idealservice would include a private day care provider in the care recipientrsquosneighborhood so that caregivers could take a break and a backup sys-tem for the care recipient if the caregiver became ill

DISCUSSION

Our findings like those of numerous other studies provide evidencethat caregiving experiences care-related values and beliefs and carepractices differ across racial and ethnic groups (Aranda amp Knight1997 Connell amp Gibson 1997 Dilworth-Andersen 2002 Janevic ampConnell 2001) Our findings also reveal a number of striking consisten-cies across the eight racial and ethnic groups in our study as reflected inthe cross-cutting constructs of familism group identity and service bar-riers These findings are discussed below in terms of their implicationsfor existing knowledge regarding family responsibility resource utili-zation and program and service implications for caregivers from racialand ethnic minority populations

Family Responsibility

Family responsibility emerged as a central theme with caregivingseen as an enactment of cultural traditions regarding family care rolesand activities Help-giving to the care recipient was described as a natu-ral extension of onersquos responsibility to the family as a whole and to an-cestral traditions often handed down from generation to generationIndividual caregivers pictured themselves as a link in an historictrans-generational chain providing continuity with ancestors and fam-ily members yet to come From this perspective caring for a disabledfamily member was experienced not so much as a choice but as a dutyFamily responsibility was manifested in norms of familism mutualsupport reciprocity and filial obligation (Becker Beyene Newsom ampMayen 2003) which pervaded the focus group participantsrsquo discussionof their care experiences Moreover these norms were perceived asdifferentiating these non-White and Hispanic caregivers from the ma-jority culture which ldquodoesnrsquot carerdquo Levkoff and colleagues (1999) alsofound that non-White caregivers believed that their way of taking careof elders ldquois much better than the American wayrdquo (p 350) and saw their

148 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

ethnicity as a major reason for not admitting a relative into a nursinghome

Family-centered cultural norms also provided a context for positiveperceptions of the caregiving experience Indeed focus group partici-pants seldom mentioned strain or burden most often describing care-giving as a source of personal satisfaction and emotional fulfillmentSatisfaction was found in carrying out expected roles in honoring andbeing honored in relationships with family members and in connec-tions with the past and the anticipated future The well-being of the carerecipient and of the family as a whole transcended the personal de-mands experienced by the individual This emphasis on traditionalnorms and family well-being suggests that for some non-White andHispanic caregivers measures of individual emotional and physicalstrain typically used with White caregivers may not adequately reflectthe most salient dimensions of the caregiving experience perhaps con-tributing to the relatively low levels of caregiver strain sometimes foundamong non-White caregivers (Farran et al 1997 Miller et al 1995 Mui1992) African-American caregivers for example have been found toappraise their caregiving roles more positively and report greater satis-faction than do White caregivers (Roff et al 2004 Lawton et al 1992)Rather for some racial and ethnic groups satisfaction and distress incaregiving roles may be rooted more deeply in onersquos self-perceived as-sessment of the extent to which one is fulfilling culturally-mediatedfamily care expectations More research is needed to assess this hypoth-esis more fully

Existing cultural norms regarding family responsibility were notseen as static however Focus group participants consistently expressedconcern that cultural norms were weakening Younger cohorts wereseen as having less cultural identification and commitment coupledwith the breakdown of traditional community support structures andvalues prompting concerns regarding the availability and commitmentof family members to provide care when the caregivers themselvesneeded help Indeed a number of writers have suggested that a shiftfrom ldquofilial pietyrdquo to ldquofilial autonomyrdquo may be underway among immi-grant families (Pang et al 2003 Silverstein 2000) with relatively fewmiddle-aged children able to enact the traditional practices associatedwith filial piety (Sung 1998) Mausbach and colleagues for examplefound that more-acculturated Latinas are less likely to identify positiveaspects of caregiving than are their less-acculturated counterparts(Mausbach et al 2004) Contextual factors such as decreasing neigh-

Scharlach et al 149

borhood cohesiveness and geographic decentralization may also becontributing to changing cultural norms among some non-immigrantgroups

Resource Utilization

Focus group participants seldom used formal services and displayedmarkedly little knowledge of outside sources of support Mistrust of po-tential service providers rooted in experiences of discrimination andactual or perceived vulnerability was a recurrent theme in each of thefocus groups A common history of adversity prejudice and dislocationcontributed to a sense of group identity but also vulnerability While priorand contemporaneous hardships experienced by members of minoritygroups may decrease the likelihood that caregiving demands will beperceived as unusually difficult or stressful (Knight amp McCallum1998) discrimination and dislocation can also serve to isolate care-givers from potential sources of outside support Investigations of dis-parities in health care service use among racial and ethnic minoritypopulations have cited the reluctance to obtain help from outsiders as apotentially important barrier to seeking needed services (Dunlop et al2002) Latino families for example frequently have been found to bewary of professionals whom they do not already know (Ruiz-Beltran ampKamau 2001)

Low rates of service utilization by non-White and Hispanic care-givers also may reflect deficits with regard to the actual availability ofneeded resources Services for non-White and Hispanic caregivers maybe limited with regard to their accessibility affordability and appropri-ateness For example Latino caregivers have been found to be espe-cially likely to experience difficulties due to language barriers and alack of culturally-competent services (Levkoff et al 1999) Financialbarriers to service use also are likely to be important (Wallace et al1994) although several studies have found that the cost of services andgeographic access to services are not necessarily predictive of formalservice use (Strain amp Blandford 2002 Fortney Chumbler Cody ampBeck 2002 Toseland McCallion Dawson Gieryic amp Guilamo-Ramos1999) Even when services are available immigrants may find eligibilityand service information confusing or intimidating (Pang et al 2003)Moreover even highly-acculturated middle-class well-educated im-migrants often prefer to speak their native language when discussingpersonal matters such as family care (Echeverry 1997)

150 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

Low rates of service utilization sometimes have been seen as a reflec-tion of cultural ldquostrengthrdquo and solidarity (Bengtson et al 1996) For ex-ample Latina caregivers have been found to delay institutionalizationsignificantly longer than do Caucasian caregivers (Mausbach et al2004) However in maintaining care for a longer period of time thesecaregivers may be experiencing service needs that are not being met ad-equately Indeed non-White and Hispanic caregivers have consistentlybeen found to experience higher levels of unmet service needs than doWhite caregivers (Ho et al 2000 Hinrichsen amp Ramirez 1992Naivaie-Waliser et al 2001)

In this study service gaps apparently were not filled by ethnic-spe-cific communal organizations and resources Indeed focus group par-ticipants made little mention of church social and cultural organiza-tions or other potential community resources Instead these non-Whiteand Hispanic caregivers relied mainly on family members and friendsfor support and assistance Indeed families have been found to be notonly the first but in many cases the only place that non-White and His-panic individuals turn to for help with personal problems (Phillips et al2000 Sotomayor amp Randolph 1988) This may be especially true inimmigrant families where family members and friends typically arecalled upon to assist with providing transportation and overcoming lan-guage barriers (Pang et al 2003) prerequisites to formal service use

Program and Service Implications

When asked to identify services that would assist them in their care-giving roles most focus group participants talked primarily about ser-vices for the care recipient rather than for themselves This was consis-tent with participantsrsquo general pattern of discussing the care recipientand the care situation rather than their personal reactions to it To someextent this could have resulted from a concern that acknowledging dis-satisfaction in the caregiving role could be seen as culturally dystonicand bring disapproval from cultural peers (Gallagher-Thompson et al2003) However the tendency to focus on the care recipient and theirneeds also reflected the participantsrsquo general family-centered approachwhereby family well-being took precedence over personal consider-ations It is not surprising therefore that programs and services tar-geted ldquoto best meet the needs of the individual caregiverrdquo [emphasisadded] (NFCSP 2001) rather than the family system are underutilizedby Hispanic and non-White caregivers

Scharlach et al 151

Our findings point to the importance of a family-centered approachto meeting the needs of Hispanic and non-White caregivers in terms ofwhat services are offered and how they are presented Focus group par-ticipants indicated that they would use caregiver support services ifthose services were seen primarily as benefiting the care recipient ratherthan themselves Training and counseling regarding care provision forexample were seen as potentially useful to the extent that they couldhelp caregivers to provide better care and be less reliant on outside as-sistance Similarly many caregivers mentioned the need for in-homerespite care primarily as a mechanism for enabling them to providebetter care over a longer period of time rather than for alleviating theirown caregiver strain It also was seen as very important that service pro-viders be as similar as possible to the care recipient in order to over-come mistrust of ldquooutsidersrdquo and other linguistic and cultural barriers(Levkoff et al 1999) Finally a family-centered approach to caregiversupport involves strengthening the capabilities and resources that fami-lies bring to the provision of care This includes reimbursement forhome care and health benefits in order to overcome the financial hard-ships experienced by more economically challenged Hispanic andnon-White care providers (NACAARP 2004)

Given the lack of trust in majority cultural institutions expressed bythese focus group participants stemming from histories of adversityand discrimination strengthening the capacity of their existing commu-nal organizations and institutions would appear to be an essential com-ponent of any effort to provide needed support to these caregivers andtheir families For example a central tenet of culturally-competent ser-vice provision is that services need not only to be culturally appropriatebut also need to be provided and organized in collaboration with mem-bers of the particular cultural community (AoA 2001)

Community partnerships between the aging network and acceptedethnic-specific community-based entities which already are trusted byand familiar to Hispanic and non-White caregivers can also help toovercome recruitment barriers and enhance service participation by mi-nority caregivers as has been shown for Chinese American caregiversand Hispanic caregivers (Gallagher-Thompson et al 2003 Arean et al2003 Levkoff et al 1999) Community partnerships also enhance thesocial capital of the communities in which services are providedthereby potentially improving the long-term ability of those communi-ties and their institutions for meeting the needs of disabled persons andtheir families

152 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

Study Limitations

While these findings generally are consistent with those of otherstudies of individual ethnic groups and their service needs theirgeneralizability may be somewhat limited by the nature of the focusgroup methodology utilized in this study Focus group participants wereselected using local publicity and snowball techniques and their viewsare not necessarily representative of the entire population of caregiversfrom each racial or ethnic group Moreover each racial and ethnicgroup is highly heterogeneous including many diverse subgroupsCaregiving-related attitudes values and behaviors undoubtedly willvary based on caregiversrsquo country of origin number of years or genera-tions in the United States acculturation generational status in the fam-ily and other individual characteristics Ultimately these findings pointto the need for additional research to better understand the ways inwhich cultural norms and racially- and ethnically-mediated experiences(eg discrimination and adversity) affect the care experiences atti-tudes and support needs of family caregivers

CONCLUSION

The findings presented here add to existing knowledge regarding theexperiences and perspectives of diverse groups of family caregiversData from the eight different racial-specific and ethnic-specific groupsin this study revealed three common cross-cutting constructs (familismgroup identity service barriers) reflecting nine underlying themesThese findings have implications for understanding family responsibil-ity and caregiver supports among racially and ethnically diverse familycaregivers and for developing culturally-relevant family- and commu-nity-centered caregiver support services

REFERENCES

Adams B Aranda M Kemp B amp Takagi K (2002) Ethnic and gender differencesin distress among Anglo American African American Japanese American andMexican American spousal caregivers of persons with dementia Journal of ClinicalGeropsychology 8 279-301

Ajrouch K Antonucci T amp Janevic M (2001) Social Networks Among Blacks andWhites The Interaction Between Race and Age The Journals of Gerontology Se-ries B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 56 S112-S118

Scharlach et al 153

Aranda MP amp Knight BG (1997) The influences of ethnicity and culture on thecaregiver stress and coping process A sociocultural review and analysis The Ger-ontologist 37 342-357

Aranda MP Villa VM Trejo L et al (2003) El Portal Latino Alzheimerrsquos projectmodel program for Latino caregivers of Alzheimerrsquos disease-affected people So-cial Work 48(2) 259-272

Beker G Beyene Y Newsom E amp Mayen N (2003) Creating continuity throughmutual assistance Intergenerational reciprocity in four ethnic groups Journal ofGerontology Social Sciences 58B(3) S151-S159

Bengtson V Rosenthal C amp Burton L (1996) Paradoxes of families and aging InR Binstock and L George (Eds) Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences (4thed pp 254-282) New York Academic Press

Clark M amp Huttlinger K (1998) Elder care among Mexican American familiesClinical Nursing Research 7(1) 64-81

Connell C amp Gibson G (1997) Racial ethnic and cultural differences in dementiacaregiving Review and analysis The Gerontologist 37(3) 355-364

Cox C amp Monk A (1993) Hispanic culture and family care of Alzheimerrsquos patientsHealth and Social Work 18(2) 92-100

Damskey M (2000) Views and visions Moving toward culturally competent prac-tice In S Alemaacuten T Fitzpatrick TV Tran and EW Gonzalez (Eds) TherapeuticInterventions with Ethnic Elders Health and Social Issues (pp 195-208) New YorkThe Haworth Press Inc

Dilworth-Anderson P Williams I amp Gibson B (2002) Issues of race ethnicity andculture in caregiving research A 20-year review (1980-2000) The Gerontologist42(2) 237-272

Dunlop D Manheim L Song J amp Chang R (2002) Gender and ethnicracial dis-parities in health care utilization among older adults Journal of Gerontology SocialSciences 57B(3) S221-S233

Echeverry J (1997) Treatment barriers Accessing and accepting professional helpIn J Garcia amp M Zea (Eds) Psychological interventions and research with Latinopopulations (pp 94-107) Boston Allyn amp Bacon

Fortney J Chumbler N Cody M amp Beck C (2002) Geographic access and ser-vice use in a community-based sample of cognitively impaired elders Journal ofApplied Gerontology 21(3) 352-367

Gallagher-Thompson D Hargrave R Hinton L Aacuterean P Iwamasa G amp Zeiss LM (2003) Interventions for a multicultural society In D Coon amp D Gallagher-Thompson amp L W Thompson (Eds) Innovative Interventions to Reduce DementiaCaregiver Distress (pp 50-73) New York Springer

Gallagher-Thompson D Solano N Coon D amp Arean P (2003) Recruitment andretention of Latino dementia family caregivers in intervention research Issues toface lessons to learn The Gerontologist 43(1) 45-51

Gill C Hinrichsen G amp DiGiuseppe R (1998) Factors associated with formal ser-vice use by family members of patients with dementia Journal of Applied Gerontol-ogy 17(1) 38-53

Giunta N Chow J Scharlach A amp Dal Santo T (in press) Ethnic differences in fam-ily caregiving in California Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment

Harwood D Baker W Cantillon M Lowenstein D Ownby R amp Duara R(1998) Depressive symptomatology in the first degree family caregivers of Alzhei-

154 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

mer disease patients A cross-ethnic comparison Alzheimer Disease and AssociatedDisorders 12 340-346

Ho C Weitzman P Cui X amp Levkoff S (2000) Stress and service use among mi-nority caregivers to elders with dementia Journal of Gerontological Social Work33(1) 67-88

Horowitz CR (1998) The role of the family and the community in the clinical settingIn S Loue (Ed) Handbook of immigrant health (pp 163-182) New York PlenumPress

Hudson P amp McMurray N (2002) Intervention development for enhanced lay pal-liative caregiver supportndashthe use of focus groups European Journal of Cancer Care11 262-270

Ishii-Kuntz M (1997) Intergenerational relationships among Chinese Japanese andKorean Americans Family Relations 46 23-32

Kidd PS amp Parshall MB (2000) Getting the focus and the group Enhancing ana-lytical rigor in focus group research Qualitative Health Research 10 293-308

Knight B amp McCallum T (1998) Heart rate reactivity and depression in AfricanAmerican and White dementia caregivers Reporting bias or positive coping Agingand Mental Health 2(3) 212-221

Kosloski K Montgomery R amp Youngbauer J (2001) Utilization of respite ser-vices A comparison of users seekers and nonseekers The Journal of Applied Ger-ontology 20(1) 111-132

Lawton M Rajagopal D Brody E amp Kleban M (1992) The dynamics ofcaregiving for a demented elder among Black and White families Journal of Geron-tology Social Sciences 47 S156-S164

Leung KK Wu EC Lue BH amp Tang LY (2004) The use of focus groups inevaluating quality of life components among elderly Chinese people Quality of LifeResearch 13 179-190

Levkoff S Levy B amp Weitzman P (1999) The role of religion and ethnicity in thehelp seeking of family caregivers of elders with Alzheimerrsquos disease and relateddisorders Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 14 335-356

Liu K Manton KG amp Aragon C (2000) Changes in Home Care Use by Older Peo-ple with Disabilities 1982-1994 Washington DC AARP Public Policy Institute

Markides KS Rudkin L Angel RJ et al (1997) Health status of Hispanic elderly inthe United States in racial and ethnic differences in late life in the health of older Amer-icans Edited by LG Martin BJ Soldo and KA Foote Washington DC NationalAcademy of Sciences pp 285-300

Mui AC Choi NG amp Monk A (1998) Long-term care and ethnicity Westport CTAuburn House

Navaie-Waliser M Feldman P Gould D Levine C Kuerbis A amp Donelan K(2001) The experiences and challenges of informal caregivers Common themesand differences among Whites Blacks and Hispanics The Gerontologist 41(6)733-741

Nkongo N amp Archbold P (1995) Reasons for caregiving in African American fami-lies Journal of Cultural Diversity 2(4) 116-123

Pang EC Jordan-Marsh M Silverstein M amp Cody M (2003) Health-seeking be-haviors of elderly Chinese Americans Shifts in expectations The Gerontologist43(6) 864-874

Scharlach et al 155

Phillips L de Ardon E Komnenich P Killeen M amp Rusinak R (2000) The Mex-ican American caregiving experience Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences22(3) 296-305

Robinson N (1999) The use of focus group methodologyndashwith selected examplesfrom sexual health research Journal of Advanced Nursing 29(4) 905-913

Ruiz-Beltran M amp Kamau JK (2001) The socio-economic and cultural impedi-ments to well-being along the US-Mexico border Journal of Community Health26(2) 123-133

Schulz R and Beach SR (December 1999) Caregiving as a Risk Factor for Mortal-ity The Caregiver Health Effects Study Journal of the American Medical Associa-tion 282(23) 2215-2219

Silverstein M (2000) Support for the elderly in China the United States and Sweden Across-cultural perspective Paper presented at the University of Southern California In-ternational Seminar Harmonizing Social Welfare for the Aged Through Socioeco-nomic Development in China Japan South Korea Israel and the United States LosAngeles CA

Smerglia V Deimling G amp Barresi C (1998) BlackWhite family comparisons inhelping and decision-making networks of impaired elderly Family Relations 37305-309

Sotomayor M amp Randolph S (1988) A preliminary review of caregiving issues andthe Hispanic family In M Sotomayor amp H Curiel (Eds) Hispanic elderly A cul-tural signature (pp 137-160) Edinburg TX Pan American University Press

Strain L amp Blandford A (2002) Community-based services for the taking but fewtakers Reasons for nonuse The Journal of Applied Gerontology 21(2) 220-235

Sung KT (1998) Filial piety in modern time Timely adaptation and practicing pat-terns Paper presented at the Aging and Beyond 2000 One World One FuturendashThe-matic Keynote Highlights The 16th World Congress of Gerontology AdelaideAustralia

Tennstedt S amp Chang BH (1998) The relative contribution of ethnicity versus so-cioeconomic status in explaining differences in disability and receipt of informalcare Journal of Gerontology Social Sciences 53B(2) S61-S70

Toseland R McCallion P Dawson C Gieryic S amp Guilamo-Ramos V (1999)Use of health and human services by community-residing people with dementiaJournal of the National Association of Social Workers 44(6) 505-600

Toseland R McCallion P Gerber T amp Banks S (2002) Predictors of health andhuman services use by persons with dementia and their family caregivers SocialSciences and Medicine 55 1255-1266

White-Means SI amp Thornton MC (1996) Well-being among caregivers of indi-gent Black elderly Journal of Comparative Family Studies 27(1) 109-128

Williams S amp Dilworth-Anderson P (2002) Systems of social support in familieswho care for dependent African American elders The Gerontologist 42 224-236

Youn G Knight B Jeong H amp Benton D (1999) Differences in familism valuesand caregiving outcomes among Korean Korean American and White Americancaregivers Psychology and Aging 14 355-364

MANUSCRIPT RECEIVED 020205MANUSCRIPT REVISED 041105

MANUSCRIPT ACCEPTED 053105

156 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

care-related values and beliefs care practices and factors contributingto decisions about the use of caregiver support services Analysis of fo-cus group transcripts revealed three cross-cutting constructs familismgroup identity and attitudinal and structural barriers to service use Wediscuss these findings in terms of their implications for existing knowl-edge regarding family responsibility resource utilization and programdevelopment for racially and ethnically diverse family caregivers [Arti-cle copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service1-800-HAWORTH E-mail address ltdocdeliveryhaworthpresscomgt WebsitelthttpwwwHaworthPresscomgt copy 2006 by The Haworth Press Inc All rightsreserved]

KEYWORDS Family caregiving focus groups cultural diversity ser-vice use

Despite demanding care situations (Aranda amp Knight 1997 NACAARP 2004 Navaie-Waliser et al 2001) and related caregiver strain(Adams et al 2002 Aranda et al 2003 Cox amp Monk 1990 HarwoodBaker Cantillon Lowenstein Ownby amp Duara 1998 Markides et al1997 Connell amp Gibson 1997 NACAARP 2004 Adams et al 2002Lee amp Sung 1998) minority caregivers tend to use formal support ser-vices substantially less than their non-Hispanic White counterparts(Dilworth-Anderson et al 2002 Dunlop et al 2002 Mausbach et al2004 Tennstedt amp Chang 1998 White-Means amp Thornton 1996)

Low service use among minority ethnic caregivers is of particularconcern because it has been associated with unmet needs for assistanceand support Caregivers from African American Latino Asian and Pa-cific Island populations consistently express a greater need for formalsupport services and higher levels of unmet social and mental healthneeds than do non-Hispanic White caregivers (Cox 1999 Hinrichsen ampRamirez 1992 NACAARP 2004 Wallace amp Lew-Ting 1992 Ho etal 2000)

The reasons for the apparent underutilization of caregiver servicesamong non-White and Hispanic populations are not well understoodEfforts to explain restricted service use among caregivers from racialand ethnic minority groups have typically relied on correlational datamost often from African American caregivers (Ajrouch Antonucci ampJanevic 2001 Connell amp Gibson 1997 Dilworth-Anderson et al

134 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

2002) who apparently are substantially more likely to use support ser-vices than are other racial and ethnic groups

Culturally-defined values norms and roles have been identified asmajor determinants of the caregiving experience and are likely to affectservice utilization Familism a primary value of Latino cultures is of-ten cited as a motivating factor for providing care (Becker BeyeneNewsom amp Mayen 2003) including the expectation that extended familywill assist with the care of older relatives (Cox amp Monk 1993 Clark ampHuttlinger 1998) Closely linked to familism are the concepts of mutualsupport reciprocity (giving back love and support to family memberswho have given the same) filial obligation and respect shown for anolder relativersquos worthiness and authority (Nkongo amp Archbold 1995Giunta et al in press Ishii-Kuntz 1997 Connell amp Gibson 1997)

Several studies have linked the availability of informal support to re-duced use of formal services (Strain amp Blandford 2002 KosloskiMontgomery amp Youngbauer 2001 Horowitz 1998) The majority ofexisting research suggests that ethnic minority caregivers have wider andstronger informal support networks than White caregivers (Aranda ampKnight 1997 Connell amp Gibson 1997 Dilworth-Anderson et al2002 Mui Choi amp Monk 1998 Smerglia Deimling amp Barresi 1998Giunta et al in press) Other evidence suggests that informal supportmay not always be so available for Hispanic and non-White caregiversPhillips and colleagues (2000) found that Mexican American caregivershad smaller social support networks and received significantly less sup-port than did non-Hispanic White caregivers Youn and colleagues(1999) found that Korean American caregivers primarily daughters re-ported having less social support than White caregivers

Caregivers from racial and ethnic minority groups also may be espe-cially likely to experience structural barriers to service utilization in-cluding inadequate transportation insufficient knowledge aboutservices cost of services language barriers negative prior experienceswith services and lack of culturally-sensitive services (Damskey 2000Mui et al 1998 Toseland McCallion Gerber and Banks 2002 GillHin- richsen amp DiGiuseppe 1998 Williams and Dilworth-Anderson2002 Dilworth-Anderson et al 2002 Levkoff Levy amp Weitzman1999 Giunta et al in press)

As the ethnic and cultural diversity of the United Statesrsquo populationincreases so does the need to understand the reasons for the underutili-zation of formal services by ethnic minority caregivers Hypotheses toexplain observed patterns of low formal service use have included fam-

Scharlach et al 135

ily-centered cultural norms greater informal support and structuralbarriers to service use However studies to date have been based pri-marily on information from individuals already receiving services andhave provided only limited guidance regarding the perspectives of care-givers from a wide range of racial and ethnic minority groups Little isknown about caregiversrsquo own experiences and attitudes about serviceuse from their own cultural perspectives and in their own languagesEspecially lacking is information from Asian and Pacific Island care-givers the groups least likely to use formal support services

This study examines reasons for restricted service use among care-givers from eight racial and ethnic minority groups Particular attentionis given to commonalities in the experiences of caregivers from diversegroups regarding their family care responsibilities the role of currentinformal and formal supports and the potential utility of desired sup-ports

METHODS

Racial-specific and ethnic-specific caregiver focus groups wereheld to examine cultural variations in the family caregiving experi-ence and to identify factors contributing to decisions about the use ofcaregiver support services among each of the eight non-White popu-lations with the greatest representation in California (US Census2000) African-Americans Chinese Filipinos Korean Native Ameri-cans Hispanics Russian and Vietnamese Focus groups are in-depthopen-ended facilitator-moderated group discussions of one to twohours duration that explore a specific set of issues on a predefined andlimited topic (Robinson 1999) Focus groups have been found to bean effective way to ldquoobtain data about feelings and opinions from asmall group of participants about a given problem experience serviceor other phenomenonrdquo (Leung Wu Lue amp Tang 2004) especially inorder to provide insight from socially marginalized groups regardingspecific phenomena that have emerged in existing data (Hudson ampMcMurray 2002 Kidd amp Parshall 2000)

Focus Group Recruitment

Focus group participants were recruited through community organi-zations serving each of the eight racial or ethnic populations (AfricanAmerican Chinese Filipino Korean Native American Hispanic Rus-

136 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

sian and Vietnamese) three in the San Francisco Bay Area one in Sac-ramento one in Los Angeles and three in outlying areas of SouthernCalifornia These organizations included community centers (eg theAsian Community Center the Filipino American Council First NationsTribal Family Center) churches health clinics senior services agen-cies and local Area Agencies on Aging (AAA) Most of the organiza-tions chosen did not already have programs explicitly targeted tocaregivers and efforts were made to recruit individuals who were notnecessarily already utilizing caregiver support programs Focus groupparticipants were recruited through posted fliers and personal contactwith organization members or consumers and received $5000 for theirparticipation

Participant Characteristics

A total of 76 individuals participated in the eight focus groups fromsix participants in the Hispanic group to 12 in the African-American andVietnamese groups (see Table 1) Participants ranged in age from theirearly 20s to their early 70s approximately two-thirds were women Themajority of participants were providing care to an elderly parent withsmaller numbers caring for spouses other family members neighborsor friends

Procedure

Focus groups lasted approximately two hours and were conducted inthe preferred language of the participants The focus groups were facili-tated by graduate students staff and faculty members from the Universityof California at Berkeley and California State University San BernardinoThe facilitators were matched to the language ethnicity and culturalbackgrounds of each group and received training in conducting focusgroups from experienced practitioners Focus group moderators followeda semi-structured discussion guide translated as necessary which in-cluded the following primary prompts

bull For whom do participants provide carebull How do participants view their role as a care providerbull What has the experience of providing care been like for them and

(how) is that affected by their race or ethnicitybull Where do participants turn for support and assistancebull What would they ideally like from a caregiver support agency

Scharlach et al 137

These questions were used to promote open discussion among theparticipants regarding their experiences as care providers and were ac-companied by specific follow-up prompts as needed The focus groupswere audiotaped and at least one note taker was present at each session

Analysis

Following each group meeting the moderator and note taker brieflydiscussed the group process and then each separately prepared aone-page summary of their impressions All materials from the eightgroups including tapes transcripts notes and summaries were sub-mitted to the research team for analysis

Based on the structure of the discussion guide and a preliminary re-view of focus group materials nine general categories were identified

138 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

TABLE 1 Focus Group Participants

Focus Group ofparticipants

Agerange

Gender Care recipient

African-Americans 12 20-70 10 female2 male

Parent-8Aunt-2Grandmother-1Daughter-1

Chinese 8 30-70 4 female4 male

Spouse-1Parent-4Aunt-1Multiple persons-1Unknown-1

Filipino 9 30-60 7 female2 male

Spouse-3Parent-1Aunt -1Friend-3Overlaps-1

Korean 9 25-65 4 female5 male

Parent-8Brother-1

Native American 11 30-60 6 female5 male

Parent-4Grandmother-2Unknown-5

Hispanic 6 20-25 3 female3 male

Parent-1Grandparent-3Neighbor-2

Russian 9 40-60 7 female2 male

Spouse-1Parent-7Son-1

Vietnamese 12 28-61 9 female3 male

Parent-11Friend-1

for organizing the data positive aspects of the caregiving experiencenegative aspects of the caregiving experience racialethnic group mem-bership informal support formal support suggestions for improvingformal support characteristics of ideal agencies policy recommenda-tions and other points important to participants Two coders independ-ently reviewed all raw data and identified key issues from each focusgroup corresponding to each of these nine categories Where differ-ences in issues were found the coders discussed and resolved any dis-crepancies

Research analysts then prepared summaries of data from each focusgroup contextualizing the categorized issues with additional informa-tion regarding group location and logistics descriptions of participantsand their care recipients caregiving experiences sources of supportand recommendations for programs services and policies The PI andthree research analysts then reviewed the summaries and other availableinformation and independently identified major themes that appearedthroughout the eight focus groups in each of three general areas experi-ences providing care attitudes and experiences with informal supportnetworks and attitudes and experiences with formal support servicesThe identified themes and examples illustrating each of them were dis-cussed among the four analysts until there was agreement on a commonset of nine cross-cutting themes These nine themes which are de-scribed in the following section were then grouped into three overarch-ing constructs (1) familism (2) group identity (3) service barriers

FINDINGS

Familism

Family-oriented themes emerged consistently throughout the eightfocus groups contextualizing the caregiving experience within fam-ily-centered cultural traditions and interpersonal impacts of providingcare Two primary themes related to the overarching construct offamilism emerged (1) cultural norms and traditions underlying the de-cision to provide care (2) personal and interpersonal fulfillment associ-ated with fulfilling those norms and traditions

Cultural Determinants of Caregiving Responsibilities

In describing their motivations for providing care focus group par-ticipants consistently identified longstanding cultural traditions that de-fined their family obligations Caring for ill or disabled family members

Scharlach et al 139

was seen as a responsibility that fulfilled cultural norms maintainedcultural continuity and strengthened family ties Caregiving was de-scribed as something that just needed to be donendashnot merely the ldquocor-rectrdquo thing to do but the ldquoonlyrdquo thing to do

The cultural context of caregiving was articulated especially clearlyby one African-American focus group participant ldquoMinority groupshave more cultural emphasis on caring for their own people It providesstronger family ties and thatrsquos what allows me to do it as part of thecommunity part of the culturerdquo Many other participants in the Afri-can-American group also expressed the view that family members areexpected to provide whatever care is necessary no matter what the carerecipientrsquos needs or circumstances A Chinese participant said ldquothere isa sense of tradition to take care of your parents the Chinese usuallytake care of their ownrdquo Vietnamese participants described caregivingas a family affair with everyone sharing in the care responsibilities

The benefits of maintaining continuity with onersquos cultural traditionswere cited by participants in a number of focus groups One Russiancaregiver commented ldquoWe did it in Russia and we continue doing ithere I had wonderful parents and I do what they didndashtaking carerdquoMany of the Native American participants said that caregiving served asan example to other family members and allowed the caregiver to passdown their Native American traditions and values from one generationto the next

Caregiving as a Source of Fulfillment

Rather than being seen as a burden caregiving was described mostoften as a source of personal satisfaction and emotional fulfillment as aresult of helping family members in their time of need fulfilling cul-tural norms and bringing family members closer together

Many of the Russian-speaking participants for example shared pos-itive emotions about providing care They expressed feelings of happi-ness and joy saying that they were very thankful for the opportunity tohelp family members something that they considered a positive role inthe Russian culture Many of the Chinese caregivers also talked abouthow fulfilling it was to provide help One of the Chinese caregiverscommented that being able to help the care recipient provided ldquoa happi-ness that money canrsquot buyrdquo Making the care recipient happy was a par-ticular source of satisfaction and fulfillment in spite of the workinvolved

140 JOURNAL OF GERONTOLOGICAL SOCIAL WORK

African-American focus group participants voiced similar positiveviews of caregiving referring to the good feelings associated with help-ing someone in need and the opportunity to become closer to relativesOne participant who had been providing care for five years summarizedher feelings by saying simply ldquocaregiving is a blessingrdquo Another par-ticipant described the challenges of providing care to family memberswho are dying but focused on the fulfillment that comes when ldquoyouknow that you were there [and] you know that you did your partrdquo

Group Identity

Cultural variations in the caregiving experience associated withmembership in a particular racial or ethnic group were another major fo-cus of discussion among focus group participants Three primarythemes related to the construct of group identity emerged (1) group-re-lated experiences of adversity and discrimination which affected thecaregiving experience (2) caregiving behaviors and norms which dif-ferentiated onersquos own group from the majority culture (3) transitions inonersquos group identity and cultural context which impacted the availabil-ity of natural support networks

Group Experiences with Adversity

Many participants indicated that their experience as a caregiver wasimpacted by adversity experienced currently or historically by their cul-tural group including discrimination prejudice dislocation or othertypes of hardship the group had faced collectively For example partici-pants in the Native American group discussed at length the hardshipsthat Native Americans have endured including a history of discrimina-tion poverty isolation and displacement they indicated that these ex-periences have resulted in an aggregate distrust of government and thedominant culture and a reluctance to utilize caregiver support servicesAfrican-American participants described how racism and low socio-economic status have hindered their ability to obtain needed servicesand also made it difficult for them to have sufficient resources to pro-vide adequate support to their care recipients

Group experiences with adversity were perceived as impactingcaregiving in some positive ways as well Many participants describedhow their personal and historical experiences of adversity had broughtthem closer together as a family or as a community In addition someparticipants indicated that dislocation and other hardships had made

Scharlach et al 141

them more sensitive to the needs of others and more committed to pro-viding care to persons who needed help Group experiences with adver-sity also affected service utilization as will be discussed under theconstruct of service barriers

Us versus Them

One issue that emerged consistently among all caregiver groups wasa sense that onersquos own cultural community differed from the majorityculture in the United States with regard to the ways in which they pro-vide care or treat their elderly members For example Hispanic care-givers clearly differentiated themselves from Anglos who were per-ceived as abandoning the care and protection of their loved ones into thehands of strangers in order to rid themselves of the burden of care ldquoImean hey you take care of your parents they live with you the wholehuge family is living together It seems like Anglo families want to getgrandma off into the nursing home where [they] donrsquot have to be both-ered with herrdquo Another participant said ldquoWe canrsquot just put them some-where else thatrsquos the way we were brought uprdquo

Vietnamese participants believed that providing care for familymembers was more important in their culture than in the Caucasian cul-ture reflecting strong family values not shared by the majority cultureRegarding the importance of caregiving in the African-American cul-ture one Africa- American participant had this to say ldquoWe shouldnrsquot belike white people where the job is more important than our relativesrdquo

Cultural Norms in Transition