Redistricting Resources for Legislators and ... - Denver, Colorado · Redistricting Resources for...

Transcript of Redistricting Resources for Legislators and ... - Denver, Colorado · Redistricting Resources for...

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 1

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff

Julia Jackson

University of Colorado Denver

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 2

Contents Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 3

Tables ........................................................................................................................................ 3

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 4

Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 6

Literature Review ....................................................................................................................... 7

Major Legal Requirements ...................................................................................................... 9

Redistricting Mechanisms ......................................................................................................14

Redistricting Staff ..................................................................................................................19

Redistricting Technology and Data ........................................................................................21

Research Questions .................................................................................................................22

Methodology .............................................................................................................................23

Results ......................................................................................................................................24

Process .................................................................................................................................24

Staff .......................................................................................................................................26

Technology ............................................................................................................................31

Resources .............................................................................................................................34

Discussion and Conclusion .......................................................................................................37

References ...............................................................................................................................40

Appendices ...............................................................................................................................43

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 3

Figures

Figure 1: Map of Congressional Redistricting Institutions ..........................................................16 Figure 2: Map of State Legislative Redistricting Institutions .......................................................17 Figure 3: State Deadlines for Completing U.S. Congressional Redistricting ..............................26 Figure 4: State Deadlines for Completing State Legislative Redistricting...................................26 Figure 5: Redistricting Staff Relative to Number of U.S. Congressional Districts .......................27 Figure 6: Average Time Staff Spent Working on Redistricting ...................................................30 Figure 7: When Preparations for the 2020 Redistricting Cycle Begin ........................................31 Figure 8: Usefulness of and Familiarity with NCSL Resources ..................................................35

Tables Table 1: Active Redistricting Litigation in 2015 ..........................................................................10 Table 2: Mechanisms for State Legislative Redistricting ............................................................15 Table 3: Official Formats of State Legislative Redistricting Plans ..............................................25 Table 4: Change in Redistricting Staff Levels 1990-2010 ..........................................................28 Table 5: Redistricting Expertise For Which States Hired Additional Staff ..................................30 Table 6: Redistricting/GIS Software Used in 1990, 2000, and 2010 ..........................................32 Table 7: Public Input to the Redistricting Process .....................................................................34 Table 8: Redistricting Resources ..............................................................................................36

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 4

Executive Summary

This project is designed to help the National Conference of State Legislators (NCSL)

prepare legislators and legislative staff for the 2020 redistricting cycle. We conducted a survey

of state redistricting staff, contacting all 50 states and receiving at least partial responses from

47 states (94 percent). The survey data answer critical questions about how the redistricting

process is staffed and managed in each state. They also assess the quality of NCSL’s existing

redistricting materials and help NCSL determine what other materials might be valuable to its

member states. Using prior surveys, we were also able to compare staff levels and technology

choices with the 1990 and 2000 redistricting cycles.

The survey covered the following areas:

• Overview questions, providing information about the person completing the survey;

• Redistricting process questions, covering legal requirements, records retention, and pending legislation and initiatives;

• Redistricting staff questions, covering the quantity and type of staff assistance used in the 2010 redistricting cycle;

• Redistricting technology questions, covering geographic information system (GIS) vendors and public map submission; and

• Redistricting resource questions, reviewing NCSL’s available resources and offering the opportunity to recommend others.

Survey respondents were primarily nonpartisan legislative staff, the vast majority of whom do

not work exclusively on redistricting issues. Most respondents worked on the 2010 redistricting

cycle.

We found that most states either have redistricting commissions or have considered

them, that most states spend 6 months to 2 years working on redistricting, and that about half of

the states hired additional staff specifically for redistricting. Staffing levels correspond loosely to

the number of congressional districts a state has, but there is a good deal of variation. And

even though the redistricting technology field has largely consolidated to two vendors, at least

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 5

half the states will consider switching to a different vendor for the 2020 cycle. Finally,

respondents were overall familiar with NCSL’s existing redistricting resources and find them

useful.

Survey findings provide justification for NCSL support in the redistricting process, even

though most respondents were confident in their states’ ability to manage the redistricting

process. They suggest a continued interest in the creation of redistricting commissions and an

increased interest in online mapping options, both for staff and the public. Respondents

expressed a desire for training sessions focused specifically on redistricting staff, with a

particular interest in GIS training. They also asked that many of NCSL’s existing resources be

updated for 2020.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 6

Introduction

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) "provides research, technical

assistance and opportunities for policymakers to exchange ideas on the most pressing state

issues and is an effective and respected advocate for the interests of the states in the American

federal system" (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2009). NCSL serves as a resource

for legislators and legislative staff on a variety of issues, including elections and redistricting.

NCSL’s redistricting and elections program has a staff of three, limiting its ability to research any

one topic in depth, and in between redistricting cycles, their focus is generally on other issues.

The program manager, Wendy Underhill, welcomed the opportunity to work with a student

specifically on redistricting.

Redistricting comes after reapportionment. The basic law of reapportionment is found in

Article I, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, as modified by the 14th Amendment, and it is short:

“Representatives […] shall be apportioned among the several states […] according to their

respective numbers[.] The actual Enumeration shall be made […] within every subsequent term

of ten Years, in such manner as they shall by law direct” (U.S. Const. art. I, § 2). Census Day is

April 1, 2020. After the Census has completed its survey, each state is granted Representatives

based on its share of the population. This is the reapportionment, and the Census Bureau must

provide reapportionment data by December 31, 2020. It is then up to the states to draw

districts for those Representatives. State legislative maps and local jurisdictional maps are also

usually drawn at this time. Additional redistricting data must be released by April 1, 2021

(McCully, 2014), after which the states begin redistricting in earnest. This project focuses on

redistricting as it relates to the U.S. Congress and state legislatures. Both functions are usually

conducted by state legislatures, though some states use a commission process for one or both

(National Conference of State Legislatures, 2009).

While much has been written about redistricting, there has been very little focus on its

administration. As the professional organization for state legislators and legislative staff, NCSL

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 7

is the ideal organization to report on this. It is also relevant to the field of public administration.

Since redistricting generally only occurs every ten years, the legislators and staff involved are

often starting from scratch. Term limits and normal staff turnover mean that many people who

drew redistricting maps in the 2010 cycle will not be doing so in 2020. For example, Legislative

Council Staff in Colorado has found that since 1990 when term limits were implemented in the

state, state representatives serve, on average, 4.8 years, and state senators serve, on average,

5.4 years (Jackson, 2015).

NCSL expects other aspects of redistricting administration to change as well. For one,

the available technology is constantly evolving. For another, with the U.S. Supreme Court

reaffirming the constitutionality of redistricting commissions (“Arizona State Legislature v.

Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission,” 2015), additional states will likely consider their

adoption. Since 2015 is the midpoint between redistricting rounds, it is an appropriate time to

evaluate the 2010 redistricting cycle and the resources that can be prepared for the next.

This project seeks to help NCSL prepare legislators and legislative staff for the 2020

redistricting cycle. It uses survey data to answer critical questions about how the redistricting

process is staffed and managed in each state. It also assesses the quality of NCSL’s existing

redistricting materials and makes recommendations for materials to prepare.

I begin this report by reviewing the redistricting literature, with a particular focus on three

areas: major case law, commissions, and technology and data. I then detail my research

questions and methodology and present the results of my research. Finally, I discuss the

results and offer a conclusion and recommendations for NCSL.

Literature Review There are two common themes in the redistricting literature that are by necessity beyond

the scope of this review: the justiciability of political questions and the role of race. I make this

distinction because NCSL, along with much of the legislative staff it represents, is a nonpartisan

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 8

organization. Making a political judgement about redistricting is not a goal of this research.

However, a basic understanding of these two themes is necessary to understand the scope of

redistricting literature, so I begin by addressing them briefly before moving into my areas of

focus.

“Gerrymandering” is a term that comes up frequently when discussing redistricting. The

term was first coined in 1812, and it can be defined as “the process of redrawing district lines to

increase unduly a group’s political power” (Levitt, 2010, p6). Researchers have identified a

number of problems with gerrymandering (“An interstate process perspective on political

gerrymandering,” 2006). These problems stem from the idea that voters are not being properly

represented by their elected representatives, which can occur when a party obtains more seats

in a legislative body than its share of the overall vote would otherwise provide (Polsby & Popper,

1991). It is often the result of agency, or “entrenchment” (Klarman, 1997) problems, where

legislators draw lines to protect their own chances of election (McConnell, 2000). This further

leads to noncompetitive districts, which can result in a Congress beset with polarization and

negative policy outcomes (Cox, 2004).

Justiciability. Once the harms of gerrymandering are identified, many scholars turn

their attention to the role of the courts in the redistricting process; whether certain questions are

“justiciable.” The articles cited in the above paragraph advocate a robust role of the courts in

policing against gerrymandering. On the other side are those who believe that the redistricting

process is inherently political. Fuentes-Rohwer (2003) argues that constituents are actually

represented well in the American system of two parties and single-member districts. Others

conclude, based on statistical analysis of state legislatures before and after redistricting, that

redistricting increases a legislature’s responsiveness and reduces partisan bias (Gelman &

King, 1994). Fuentes-Rohwer notes that when viewed from the district level, rather than the

state or national level, a majority of any district will always elect the candidate of their choice.

More importantly, “when courts intervene, they simply take sides in highly politicized debates”

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 9

(Fuentes-Rohwer, 2003, p538). Rather than policing political problems, deciding redistricting

cases makes the courts more political themselves. If the courts are not the appropriate outlet

for reducing the harms of redistricting, what is? Scholars frequently suggest changing who does

the redistricting. For example, “a strategy of reinforcing political competition by taking the

process of redistricting out of the hands of partisan officials offers the prospect of realizing our

constitutional values” (Issacharoff, 2002, p647). I review this possibility in more detail below in

my discussion of redistricting commissions.

Race and redistricting. One of the primary ways to challenge a redistricting plan in

court is over whether it meets the standards of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, discussed in more

detail below. A major debate in the literature is over the effects of racial redistricting on minority

representation. For example, Cameron, Epstein, & O’Halloran (1996) argue that increasing the

number of majority-minority districts does not actually improve minority representation in the

legislative process. They analyze the relationship between black voting age population in a

district and legislators’ support for “minority issues” and then simulate different districts and

conduct the same analysis. Lublin (1999) rebuts these findings with a point-by-point critique,

concluding that “racial redistricting remains vital to the election of African Americans” (p186).

Major Legal Requirements

As it stands, both state and federal courts are heavily involved in the redistricting

process. Professor Levitt at the Loyola Law School Los Angeles until very recently maintained a

website (Levitt, 2015) listing all the congressional and state legislative redistricting cases for the

2010, 2000, 1990, and 1980, which gives an idea of the volume of court involvement. For the

2010 cycle, Levitt identifies 224 total cases filed, 32 of which are still active as of September

2015. In only 9 states were there no cases filed, and 4 of those are states with a single

congressional representative, meaning no congressional redistricting occurred. Courts actually

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 10

drew the congressional maps in 9 states and the legislative maps in 6 states. The states still

involved in active litigation over redistricting are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Active Redistricting Litigation in 2015

State U.S. Congressional

Map in Litigation State Legislative Map

in Litigation AL X AZ X X FL X X MD X NC X X TX X X VA X WY X

Source: (Levitt, 2015)

A surprising number of redistricting cases are heard at the U.S. Supreme Court. One

reason for this is the peculiar way in which constitutional challenges to redistricting plans are

handled. Federal law requires redistricting cases to be heard by a three-judge district court

panel when they involve the constitutionality of apportionment (Manheim, 2013). These cases

can then be appealed directly to the Supreme Court, ensuring the high court will take on a

number of redistricting cases.

Manheim (2013) describes the reasons courts would review a redistricting case as

follows:

The Fourteenth Amendment requires that each plan (1) comply with the equal representation principle; (2) not purposefully discriminate against racial minorities; (3) not “subordinate” what the Supreme Court has called “traditional race-neutral districting principles” to racial considerations unless that subordination can survive strict scrutiny; and (4) in theory, at least, avoid excessive political gerrymandering. Federal statutory law in turn requires that a plan (5) not result in a dilution of minority voting strength (a “section 2” claim); (6) in certain jurisdictions, not reduce minority voting strength as compared to prior levels (a “section 5” claim); and (7) in congressional races, not use multi-member districts. Depending on the jurisdiction, there also may be restrictions set forth in state law (p579-580).

The major Supreme Court cases on each of these issues have become essential to the

redistricting process.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 11

Equal population cases. The Supreme Court for decades refused to intervene in

redistricting, calling it a “political thicket” (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2009). This

changed in 1962, when the court held in Baker v. Carr that redistricting plans could be

challenged over their constitutionality. This led to a series of decisions in the 1960s known as

the redistricting cases, culminating with Reynolds v. Sims (1964). The key finding in this case

was that districts must be drawn, “so that the vote of any citizen is approximately equal in weight

to that of any other citizen in the State.” This is the principle now familiar in redistricting law of

one person, one vote. This standard has been interpreted strictly in the years to follow, with the

court ordering states to draw their congressional districts so that they are as close to equal in

population as possible, unless the state can justify variation on other grounds (such as

respecting municipal boundaries). For congressional districts, the standard is derived from the

Constitution’s apportionment clause, but the standard for legislative districts is derived from the

equal protection clause (U.S. Const., amend. XIV, § 1). Consequently, the court has allowed

greater deviation among state legislative districts, generally up to a 10 percent difference

between the largest and the smallest absent another compelling state interest (National

Conference of State Legislatures, 2009).

Voting Rights Act cases. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) has been very

influential in redistricting jurisprudence. The two principal sections of the VRA are Section 2 and

Section 5:

Section 2 was originally a restatement of the 15th Amendment and applies to all jurisdictions. It prohibits any state or political subdivision from imposing a “voting qualification or prerequisite to voting or standard, practice or procedure ... in a manner which results in the denial or abridgement of the right to vote on account of race or color.” Section 5, on the other hand, applies only to certain jurisdictions covered under the act. A jurisdiction covered under Section 5 is required to preclear any changes in its electoral laws, practices or procedures with either the U.S. Department of Justice or the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

The two sections work independently of each other. A change that has been precleared under Section 5 still can be challenged under Section 2 (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2009, p51-52).

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 12

Thornberg v. Gingles (1986) laid out the most specific standards for assessing violations of

Section 2. If a minority group wanted to challenge a redistricting plan as diluting their vote, the

court in Gingles required them to prove:

1. The group is large enough and located in a sufficiently compact area to allow them to constitute a majority in a district;

2. The group is cohesive in its politics (racially polarized voting); and

3. The white majority usually votes in such a way as to prevail over the minority group’s preferred candidate.

The decision also stated that the court must review the “totality of the circumstances” in deciding

whether discrimination occurred. The Supreme Court later limited racial redistricting in Shaw v.

Reno (1993). It found that such claims require strict scrutiny, and it identified circumstances

under which racial redistricting could be found unconstitutional:

When majority-minority districts comply with traditional districting principles, and are drawn to redress racially polarized voting, the Court treats them as constitutionally appropriate because [they are] necessary to secure evenhanded treatment. When race-conscious districting goes further, by abandoning the principles typically used to draw other districts, the Court treats race as having been singled out for exceptionally preferential treatment (Pildes, 1997, p2511).

Both Shaw and Gingles address Section 2 claims. Shelby County v. Holder (2013), by

contrast, indirectly addresses Section 5 preclearance. What the Supreme Court actually did in

Shelby County was to declare Section 4 of the VRA unconstitutional. While Section 5 requires

preclearance for certain jurisdictions, Section 4 spells out the formula that identified which states

and local governments were subject to Section 5 preclearance. In practice, this means that

there are no longer any jurisdictions subject to preclearance, unless Congress enacts a new

formula (Howe, 2013) or jurisdictions are “bailed in” based on discriminatory actions, under

Section 3. How this will impact the next round of redistricting remains to be seen.

Partisan gerrymandering cases. Federal courts have been reluctant to review claims

of partisan gerrymandering, but they have at times waded into this arena. In Davis v. Bandemer

(1986), the court found that partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable, and it suggested that

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 13

the minority party would need to prove discrimination both in intent and effect. It did not,

however, establish an effective way to evaluate such claims. In Vieth v. Jubelirer (2004), a

fractured court found that there are “no judicially discernible and manageable standards for

adjudicating” partisan gerrymandering claims. In addition to the plurality opinion, the justices

issued a concurring opinion and three separate dissents. This suggests that “the Bandemer

standard had proved unworkable” (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2009, p122), but

the fragmented opinions left open the possibility of further attempts to adjudicate partisan

gerrymandering.

In sum, these Supreme Court rulings require states to draw districts with equal

populations that allow minority groups to elect representatives of their choice (within reason).

They may also prohibit purely partisan mapmaking, but this is less clear. Further, VRA

preclearance will likely not exist in the 2020 redistricting cycle. The court will also hear two

redistricting cases in 2016, and I briefly preview these cases below.

Harris v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission (2016) concerns Arizona’s state

legislative districts. This case came through the process described above – heard by a three-

judge panel and appealed directly to the Supreme Court. The court agreed to review whether

deviations in district size are justified on the basis of partisan advantage, and also whether the

deviations are justified by an attempt to obtain VRA preclearance, especially in light of the

Shelby County decision (Denniston, 2015). Denniston speculates that this decision is likely to

be narrowly tailored to the facts at hand, rather than creating any broad precedent.

Evenwel v. Abbott (2016), meanwhile, has the potential to significantly change the

redistricting process. Since setting the equal population standard, the Supreme Court has

declined to define “population,” leaving that up to the states. Most states use total population,

namely, the census headcount. In Evenwel, though, the Texas legislative redistricting plan was

challenged on the grounds that the total population standard results in districts with an uneven

distribution of actual voters. This is because total population necessarily includes people who

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 14

cannot or do not vote: children, convicted felons, non-citizens, and eligible but unregistered

voters. The challengers want Texas redistricters to count only voters. There are examples

where “alternative population bases” have been upheld, but no state has ever been required to

use a standard other than total population (National Conference of State Legislatures, 2009,

p10). If the Supreme Court sides with the challengers, this case would force a big change in

how states conduct their redistricting (Denniston, 2015).

Redistricting Mechanisms

Though federal law governs much of redistricting, it is up to each state to decide how its

district lines are drawn. In the 43 states with more than one U.S. congressional district, there

are two separate processes – one for congressional districts, and one for state legislative

districts. In most states, the legislature is responsible for both.

Levitt (2015) classifies redistricting institutions in five ways:

1. the legislature alone draws the lines;

2. the legislature draws the lines with the help of an advisory commission;

3. the legislature draws the lines, but a backup commission is available if the legislature fails to pass a plan;

4. a “politician commission” draws the lines, meaning elected officials may serve as commission members; or

5. an “independent commission” that excludes elected officials draws the lines.

Commissions vary significantly in their composition from state to state. For example, Levitt

classifies Oregon as having a backup commission, but in fact the backup is the Secretary of

State alone. Iowa is classified as having an advisory commission, but the staff role in Iowa is

unique. The advisory body is actually the nonpartisan Legislative Services Agency, which uses

statutory criteria to draft redistricting plans, and which can seek guidance from an independent

commission. The Iowa legislature then has three chances to accept or reject proposed plans

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 15

without modification. After three rejections, the legislature can provide its own plan, but this has

not occurred since this system began in 1980 (Levitt, 2015).

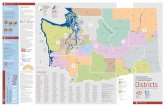

Table 2 provides more detail about the mechanisms used for state legislative

redistricting, where there is greater variation in the processes. Figure 1 and Figure 2 are Levitt’s

maps, applying the above categories to congressional and state legislative redistricting,

respectively.

Table 2: Mechanisms for State Legislative Redistricting

State

Legislature with

Gubernatorial Approval

(Veto Power)

Legislature as Sole

Authority

Legislative Process with

Backup Commission

Legislative Process with

Advisory Commission

Partisan or Bipartisan

Commission Independent Commission

AL X AK X AZ X AR X CA X CO X CT X DE X FL X GA X HI X ID X IL X IN X IA X KS X KY X LA X ME X MD X MA X MI X MN X MS X MO X MT X NE X NV X NH X NJ X NM X NY X NC X ND X OH X OK X

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 16

Table 2: Mechanisms for State Legislative Redistricting

State

Legislature with

Gubernatorial Approval

(Veto Power)

Legislature as Sole

Authority

Legislative Process with

Backup Commission

Legislative Process with

Advisory Commission

Partisan or Bipartisan

Commission Independent Commission

OR X PA X RI X SC X SD X TN X TX X UT X VT X VA X WA X WV X WI X WY X

Total 20 2 11 4 11 2 Source: Mooney, 2011

Figure 1: Map of Congressional Redistricting Institutions

Source: (Levitt, 2015)

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 17

Figure 2: Map of State Legislative Redistricting Institutions

Source: (Levitt, 2015)

The use of commissions is much discussed in redistricting literature, mostly for their

potential to reduce partisanship in the process. The commissions in Arizona and California are

seen as the most independent, and as such have generated the most interest. “[C]ollectively

they embody elements of almost every redistricting reform idea ever proposed” (Cain, 2012,

p1812).

Arizona’s commission was adopted in 2000 and used for the 2000 and 2010 redistricting

cycles (Levitt, 2015). Legislative leaders selected members of the Arizona Independent

Redistricting Commission from a pool of 25 individuals chosen by a judicial selection

commission. The five final commission members included two from each major political party

and one independent. The commission was also given criteria for drawing its maps and was

required not to base its plans on prior maps or consider incumbents.

California’s commission was adopted in 2008 (for state legislative maps) and 2010 (for

congressional maps) and used for the first time in the 2010 cycle (Levitt, 2015). The Citizens

Redistricting Commission is notable for its unique selection process (Cain, 2012). Prospective

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 18

commissioners had to meet a number of requirements aimed at keeping politics out of the pool.

Applicants (36,000 expressed initial interest in 2010) were screened by the California Bureau of

Audits, and those who qualified were invited to complete a supplemental application. This

group was then whittled down, complete with “strikes” from legislative leadership, to 36 each of

Democrats, Republicans, and independents. Three Democrats, three Republicans, and two

independents were chosen by lottery. The 8 then chose the remaining 6. Cain (2012) reports

that the commission was “diverse with respect to race, gender, and ethnicity, but not with

respect to education and class” (p1825). In addition to this novel selection process, California’s

commission was also given specific criteria to be followed and a specific order in which they

were to be applied, was subject to extensive public input processes, and was required to have

the support of members from each political party and independents to adopt a plan.

Cain offers an early analysis of the California and Arizona commissions, finding that they

“have not eliminated political controversy and partisan suspicions” (Cain, 2012, p1812) and

therefore, their plans were just as likely to be challenged in court. He notes that in California,

the commission’s maps were more compact and more competitive than the plans they replaced,

but these improvements were modest, and the plans drew criticism from many directions. Cain

also points out that by prescribing the numbers of Democrats, Republicans, and independents,

the system inherently skews away from proportional representation, as 44 percent of California

voters were registered as Democrats and 31 percent Republicans at the time. An in-depth

ProPublica report on the California Citizens Redistricting Commission (Pierce & Larson, 2011)

concluded that the national Democratic Party and California’s Democratic congressional

delegation stealthily and successfully manipulated the process in their favor.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 19

Redistricting Staff

The two articles about the California commission above also cover the role of

commission staff, but in general, this is an area to which the literature pays scant attention. The

ProPublica report notes that the commission was “overwhelmed by the task at hand” (Pierce &

Larson, 2011, np), with its expert staff overworked and underpaid. Cain also raises concerns

about the process of staffing independent commissions. Because staff require certain expertise

that the commissioners lack – geographic information systems (GIS), statistics, voting rights law

– they could, in theory, “steer commission decisions in a given direction by skewing the advice

and options” they give the commissioners (Cain, 2012, p1833). Further, “most redistricting

consultants have worked for one or the other party” (Cain, 2012, p1835), which raises

suspicions. Cain notes that Arizona’s commission in 2011 was dogged by controversy over its

staffing decisions.

Colorado’s state legislative redistricting commission, inaptly named the Colorado

Reapportionment Commission, is made up of commissioners appointed by legislative

leadership, the Governor, and the chief justice of the Colorado Supreme Court. In reflecting on

his commission service, one law professor expresses skepticism of the commission’s staff

(Nichol, Jr., 2001). He suggests that the commission’s staff, currently borrowed from the state’s

legislative service agencies, should instead be independent from the legislature, writing:

Staff members who report the rest of the year to the Speaker of the House or the Majority Leader of the Senate would be idiots to treat all commission members as equals. And our staff members clearly were not idiots. In a process in which commission members are immensely and correctly skeptical of their colleagues' motives, and in which no commission member fully understands the studies, gadgetry, jargon and software that the redistricting process requires, it is a mistake to have a staff beholden to the legislature (p1031).

Another professor who served on the Colorado Reapportionment Commission wrote an ebook

on his experience, and his comments on staff are limited to two paragraphs, one of which

misspells the name of commission’s staff director. “The staff,” he writes, “became skilled at

getting the right map up on the screen at the right time” (Loevy, 2011, p46). In his conclusions,

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 20

Loevy recommends the commission staff remain “under the administrative direction of the Office

of Legislative Legal Services” (their current configuration), though he suggests highly trained

computer experts be hired instead of existing legislative staff (p106). He found that even under

the commission structure, the political parties employed computer experts to draw maps that

were then submitted by commissioners as their own.

It appears that the role of redistricting staff, and the outside perception of that role, is not

well understood. Are staff neutral players, mostly responsible for projecting maps on screens?

Or do they wield influence on the process as behind-the-scenes experts? The literature does

not answer this question. A limited amount of research is available on the role of legislative staff

generally, however, and this may or may not be comparable.

Recent research on state legislatures has focused on their professionalization

(Grossback & Peterson, 2004), and the role of legislative staff is an area of study within this.

Some researchers have linked the size and skill level of legislative staff to the effectiveness of

legislative leadership (Jewell & Whicker, 1994). Others find that legislators identify staff as a

key source of policy information (Gray, 1999; Hammond, 1996). However, DeGregorio (cited in

Hammond, 1996, p545) found that U.S. Congressional staff “work within the parameters set by

committee norms, issue jurisdiction, and leaders’ expectations and styles.” This research

suggests that staff role is limited in actually influencing policy outcomes. Hammond (1996)

further describes research concluding that state legislative staff influence depends on the

technical nature of the issue, how much attention it receives, and whether it is “new and

unrelated to ongoing legislative concerns” (p562). Following this framework, redistricting is

certainly technical and new to most of the legislators involved, but it also receives plenty of

attention and is an issue of concern to those legislators. Applying these findings to redistricting

staff appears to be inconclusive.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 21

Redistricting Technology and Data

Conventional wisdom about redistricting suggests that improved computing has made

gerrymandering easier and more effective. For example, “incumbent entrenchment has gotten

worse as the computer technology for more exquisite gerrymandering has improved”

(Issacharoff, 2002, p624), and “data collection and computer technology […] improvements

have enhanced the capacity to gerrymander effectively” (Pildes, 1997, p2553). A

comprehensive analysis of district compactness, however, found that districts have consistently

become “more gerrymandered” (less compact) over time, and the trend increased significantly

beginning in the 1970s (Ansolabehere & Palmer, 2015). This research suggests that the one-

person, one-vote standard and the Voting Rights Act had more to do with reduced compactness

than technology.

Additionally, an in-depth analysis of the role of technology in the 2000 redistricting cycle

concluded that, “if redistricting has become more sophisticated in this round over the last,

computing technology seems unlikely to have been the primary cause” (Altman, MacDonald, &

McDonald, 2005, p343). The researchers surveyed states about the computer programs, data,

and consultants they used in the 2000 cycle. They note that from 1990 to 2000, computers

became cheaper and faster, but the software capabilities did not differ significantly. Like

Ansolabehere and Palmer, they found that trends away from compact districts began in the

1960s and 1970s, when computer technology was extremely limited. This particular study is

also useful in that its surveys produced results for the 2000 and 1990 cycles that should be

comparable to my information about the 2010 cycle. In another analysis, Altman and McDonald

note that technological advances have had a notable impact on transparency and public

participation in the redistricting process (Altman & McDonald, 2014). This is also an aspect of

redistricting technology addressed in my survey.

Issacharoff (2002) and Pildes (1997) further assert that improved data has led to more

sophisticated gerrymandering. It is also true, though, that census data is limited. The decennial

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 22

census is based on an actual headcount, but the Census also conducts an ongoing American

Community Survey (ACS), which began in 1996 and replaced the “long form” questionnaire

after the 2000 census (US Census Bureau, 2013). The actual headcount data must, by law, be

used in reapportionment. In practice, it is also used in redistricting. The ACS measures many

more variables than the headcount, but it relies on statistical sampling. Race and ethnicity

questions appear on the full census questionnaire, but other questions of interest to

redistricters, such as citizenship, are only found on the ACS. This means that the citizenship

data is not “on par” with population data (Persily, 2011, p774); in particular, it cannot accurately

estimate citizenship at the census block level, meaning it cannot be relied upon for redistricting.

This is something the Supreme Court will have to consider in the Evenwel v. Abbott case.

Additionally, Persily points out that, “voting rights law in some circuits […] demands more

information than the census can give” (p779). More broadly, there are distinct groups whose

allocation into districts raises political questions no matter how they are counted. This includes

U.S. citizens residing abroad, college students, military members, and prisoners.

Research Questions

While the literature paints a good picture of how redistricting is conducted, many

questions remain about specific procedures, especially from the perspective of NCSL’s

members – legislators and legislative staff. This project addresses some of these questions.

My broad research questions are:

• How are the congressional and legislative redistricting processes administered in each state?

• What resources can NCSL provide to help legislators and legislative staff with this process?

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 23

Methodology

To better understand the redistricting process, I surveyed staff members who have

worked for their legislatures on redistricting. The survey was sent to NCSL’s list of redistricting

contacts, drawn from the membership of its Standing Committee on Redistricting and Elections,

on September 22, 2015. The survey reached all 50 states but in some cases went to elections

staff rather than legislative staff.

Survey questions were requested by Wendy Underhill at NCSL, and then evaluated to

determine whether the desired information could be obtained elsewhere. For example, a series

of proposed questions about whether state redistricting plans were challenged in court was left

off the survey because Levitt’s website provides thorough information about this issue. Many of

the survey questions, such as a question about records retention, represent information

requested from NCSL by state legislative staff.

I prepared the survey and had it reviewed by Professor Ely and Wendy Underhill. Two

people with experience staffing redistricting also graciously agreed to review early drafts of the

survey. Michelle Davis, an employee of the Maryland Department of Legislative Services and

staff co-chair of NCSL’s Standing Committee on Redistricting and Elections, and Kate Watkins,

an employee of Colorado Legislative Council Staff and staff on the 2011 Colorado

Reapportionment Commission, provided valuable feedback. Wendy Underhill did a test run of

the survey to make sure the form worked.

The survey was prepared in Google Forms, which allows for a variety of question types

and free distribution. We also had a Word version available, but only two states used this to

actually complete the survey. The areas covered in the survey are:

• Overview questions, providing information about the person completing the survey;

• Redistricting process questions, covering legal requirements, records retention, and pending legislation and initiatives;

• Redistricting staff questions, covering the quantity and type of staff assistance used in the 2010 redistricting cycle;

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 24

• Redistricting technology questions, covering geographic information system (GIS)

vendors and public map submission; and

• Redistricting resource questions, reviewing NCSL’s available resources and offering the opportunity to recommend others.

A copy of the survey as it appeared to recipients is provided as Appendix A. We received 22

responses within a week of sending the survey, including 12 in the first 24 hours. In the end we

collected at least partial responses from 47 states.

Results The people responding to the survey were primarily nonpartisan legislative staff (33),

which is not surprising since these make up the bulk of standing committee participants. Seven

respondents were partisan legislative staff, three work for a state elections office, and four were

hired by commissions specifically for redistricting. 37 respondents, or 78.7 percent, staffed the

2010 redistricting cycle. Seven work exclusively on redistricting issues at this time, but only

three of those are legislative staff (two nonpartisan, one partisan). Survey results are presented

in four categories: process, staffing, technology, and NCSL resources. The survey form did not

require responses to any questions, so there are times when some states did not respond to a

particular question. In these cases, the non-responses are not tabulated in the results.

Process

Our process questions included whether states have proposals to create a redistricting

commission, requirements for the type of bill adopting a redistricting plan, procedures for

correcting technical errors, records retention requirements, and deadlines for completion of the

redistricting process.

22 states identified current proposals to adopt some form of redistricting commission. Of

the 24 states that did not, 16 already have commissions in place. The remaining eight were

Alabama, Delaware, Kansas, Nevada, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Utah, and Wyoming.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 25

Delaware, Nevada, and North Dakota noted that they have had proposals in prior years.

Therefore, nearly all responding states either have redistricting commissions or have considered

them.

The official formats of state redistricting plans are summarized in Table 3. The majority

of states present their redistricting plans as block assignment files, which are created by GIS

software. “Metes and bounds” bills describe physical features of the local geography, along with

direction and distances. Other types identified by respondents tended to use other geographic

descriptions – all relied on some combination of counties, townships, voting tabulation districts,

precincts, tracts, or blocks.

Table 3: Official Formats of State Legislative Redistricting Plans

Type of Bill Number of

States Block Assignment File 25 Metes and Bounds 5 Map 3 Combination of Above Types 3 Other Formats 9

In all but three states (Illinois, Ohio, and Utah), the bill types were the same for legislative and

congressional plans. Eleven states said that the bill format is specified in law, and these

statutory citations are provided in Appendix B.

Thirteen states have an official procedure for correcting technical errors, and statutory

citations for these procedures are also provided in Appendix B.

A quarter of respondents did not answer the question about their state’s redistricting

records retention policies, suggesting that they did not know the answer, or said they did not

know. Another eight states said they had no specific policy. 15 respondents said that

redistricting records fall under their state’s general records retention policies, either for state

records generally or for legislation specifically. Twelve states identified specific policies for

redistricting records, but they generally described these vaguely. No state identified a specific

statutory requirement.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 26

Figures 3 and 4 graphically represent the deadlines for states to complete their

congressional and legislative redistricting, respectively. Many of these deadlines are tied to

either legislative session lengths or filing deadlines for 2022 primary elections, but as the figures

show, there is a good deal of variation. Almost a year and half separates the first and last

congressional deadlines, and the gap is wider for legislative redistricting because the Montana

legislature only meets in odd-numbered years, pushing the state’s deadline back to 2023.

Figure 3: State Deadlines for Completing U.S. Congressional Redistricting

AR IL IN NE

ME MT

CA CT ID

NM PA

HI NJ VA WA

MN NC OH UT WY

AL KS MD OK TN WI LA

MA NY

April-May

June-July

August-

September

October-

November

December-

January

February-

March

April- May

June-July

August-

September 2021

2022

Figure 4: State Deadlines for Completing State Legislative Redistricting

IL IN NE

DE ME OR

AR CA CT ID IA

NM OH TX

CO HI LA NJ ND PA SD VA WA

MD MN NC UT WY

AL KS OK TN VT WI

AK MA NY MT

April-May

June-July

August-

September

October-

November

December-

January

February-

March

April-May

June-July

August-

September

October-

November

December-

January 2021

2022

2023

Staff

Staffing questions on the survey addressed the number and type of support staff for the

redistricting process, the average time they spent on redistricting, and whether and how

additional staff were hired. We also asked when staff preparations for the 2020 redistricting

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 27

cycle will begin, how much of the state’s redistricting staff are expected to be new to the process

in 2020, and a confidence rating for each state’s ability to manage the redistricting process.

Staff levels. Survey respondents were asked to estimate the number of full-time

equivalents (FTE) working on redistricting in the 2010 cycle and to identify the type of staff they

included in their count. Where a range was provided, I used the middle of the range for

analysis. Additionally, many staff had other responsibilities, and many respondents noted that

their numbers were inexact, so these numbers are not presented as definitive. The mean FTEs

across respondents was 9.9, with Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and California

reporting over 30. Excluding those four states, Figure 5 compares staffing levels with each

state’s U.S. congressional districts. The correlation coefficient between these two variables (as

calculated in Excel) is 0.63, indicating a slight positive correlation.

Figure 5: Redistricting Staff Relative to Number of U.S. Congressional Districts

Additional source: Burnett, 2011

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 28

NCSL also collected staffing data for the 1990 redistricting cycle, and Table 4 compares

our 2010 data to the 1990 data where available.

Table 4: Change in Redistricting Staff Levels 1990-2010

State 1990 2010 Percent change Alabama 5 5 0% Alaska - 4 - Arizona 10 9 -10% Arkansas - 8.5 - California 20 30 50% Colorado 7 13 86% Connecticut 6 - - Delaware 10 9 -10% Florida 25 - - Georgia 8 8 0% Hawaii 25 14 -44% Idaho 1 8 700% Illinois - 10 - Indiana 5 6 20% Iowa 7 3.5 -50% Kansas 6 11 83% Kentucky 11 17.5 59% Louisiana 14 7 -50% Maine - 4 - Maryland 1 6 500% Massachusetts 4 3 -25% Michigan - - - Minnesota 10 13 30% Mississippi 9 2 -78% Missouri 5 6 20% Montana 2 4 100% Nebraska 4 3 -25% Nevada 2 8 300% New Hampshire 9 7 -22% New Jersey 7 30 329% New Mexico 10 14 40% New York 14 30 114% North Carolina 5 12 140% North Dakota 2 2 0% Ohio - - - Oklahoma 8 7 -13% Oregon 5 3 -40% Pennsylvania 12 40 233%

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 29

Table 4: Change in Redistricting Staff Levels 1990-2010

State 1990 2010 Percent change Rhode Island 4 - - South Carolina - - - South Dakota 8 4 -50% Tennessee - 9 - Texas 43 13 -70% Utah 4 5 25% Vermont 3 6 100% Virginia 10 7 -30% Washington 10 15 50% West Virginia 3 4 33% Wisconsin 11 12 9% Wyoming 4 3 -25% Mean 8.8 10.3 15% Additional source: Prior NCSL research (found in NCSL files; additional information unavailable)

Consistent with what we know about our survey respondents, 35 states said their

staffing totals included nonpartisan legislative staff. 17 states included partisan legislative staff,

10 used contract consultants, and 8 included elections or other executive branch staff. Alaska,

Arizona, California, Hawaii, Pennsylvania, and Washington mentioned staff hired specifically for

a redistricting commission. By contrast, Colorado’s commission is staffed exclusively by

existing nonpartisan legislative staff. Most states reported spending between six months and

two years on redistricting. Only New York, which maintains a permanent redistricting office, and

Texas, where litigation is ongoing, reported more than four years. This data is presented

graphically in Figure 6.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 30

Figure 6: Average Time Staff Spent Working on Redistricting

Additional hiring. 28 states said they hired additional staff specifically for redistricting.

In 11 of those states, hiring decisions were made by a legislative staff agency. Political parties,

leadership, or caucuses made the hiring decisions in nine states. In six states, commissioners

or their staff made hiring decisions, and in Wyoming, additional hiring was done by the

executive branch. The expertise sought when hiring additional redistricting staff is presented in

Table 5.

Table 5: Redistricting Expertise For Which States Hired Additional Staff

Type States Seeking Number of

States

GIS/Mapping AK, AZ CA, HI, ID, IL, IA, KS, MS, NE, NV, NM, OH, OK, OR, WY, WA

17

Legal LA, MS, MO, NH, NM, PA 6 Political/Legislative AK, ME, NJ, OK, TX, WA 6 Administrative/Organizational/ Clerical/Communications HI, IL, KS, PA 4

Data Analysis CA, MA 2

When asked to speculate as to how many of the people staffing redistricting in 2020

would be doing so for the first time, states were fairly evenly split. Eight thought less than a

quarter of their staff would be new, eleven predicted 26 to 50 percent, thirteen predicted 51 to

75 percent, and twelve thought 76 to 100 percent would be new. Despite this expected

turnover, states were overall confident that they have the resources and expertise necessary to

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 31

manage the 2020 redistricting cycle. On a scale of 1 to 5, with 5 being very confident, the mean

response was 4.27. 36 states picked 4 or 5, and only Tennessee selected a score below the

midpoint.

Preparations. Figure 7 shows when states began or plan to begin preparing for the

2020 redistricting cycle. Where a range was given, this chart shows the earliest point in the

range. Again, New York has a permanent redistricting office, and so it is excluded from this

chart. Though more than half the states do not plan to begin preparing until 2018 or later, 13

states have either already begun to prepare or will do so in the next year, suggesting that some

may be seeking new NCSL resources already.

Figure 7: When Preparations for the 2020 Redistricting Cycle Begin

OR

ID KS KY MS NV VA WA

AL MN MT PA TX

IN TN

CA GA IL IA LA MD NE NC UT WY

CO DE MA ND OH WI

AK HI ME MO NH NJ NM SD

AZ VT

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Technology

States were surveyed on the mapping technology they used for redistricting, whether

they were considering a new vendor for 2020, and if so, what improvements they would be

looking for. We also asked about how states gather public input during the redistricting process.

Redistricting software. We identified three primary software programs used to draw

redistricting maps in 2010 – AutoBound (Citygate), Districting for ArcGIS (Esri), and Maptitude

for Redistricting (Caliper) – and asked states which vendor they used. 24 states (more than half

of respondents) used Maptitude, 15 used AutoBound, and 3 used Districting for ArcGIS.

Louisiana reported using a customized ArcGIS application as well as Maptitude, New

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 32

Hampshire and Texas used in-house programs, and three states were unable to identify the

mapping vendor they used. (These three are not included in the total when calculating

percentages.) Table 6 compares our data with surveys conducted in 1990 and 2000 (Altman et

al., 2005). Note that Altman’s surveys only covered congressional redistricting, so states with a

single congressional district at the time were excluded from his reports.

Table 6: Redistricting/GIS Software Used in 1990, 2000, and 2010

1990 2000 2010

Software/Vendor Number of States

Percentage of Survey

Respondents Number of States

Percentage of Survey

Respondents Number of States

Percentage of Survey

Respondents AutoBound - - 19 45.2% 15 33.3% Districting for ArcGIS/other Esri 8 21.1% - - 3 6.7%

Geodist 9 23.7% - - - - Mapinfo 1 2.6% - - - - Maptitude/Maptitude for Redistricting - - 15 35.7% 24 53.3%

Plan 90/Plan 2000 9 23.7% 2 4.7% REAPS 2 5.3% - - - - Custom 7 18.4% 6 14.3% 3 6.7% None 2 5.3% - - - - Additional source: Altman et al., 2005, p337 Particularly notable in this comparison is the decline in the number of states using custom

applications, which Altman attributes to the decreasing cost of off-the-shelf GIS software. This

chart also shows the decline in the number of vendors participating in this market, from five in

1990 to three in 2000 to three (but practically two) in 2010.

We also asked whether states were considering switching to a different mapping vendor

for the 2020 redistricting cycle, and if so, what improvements they were looking for. Several

respondents were unsure of their plans at this time, but 19 said they were considering switching,

and 23 said they were not. The “yes” responses represented 9 of 15 AutoBound users and 10

of 24 Maptitude users, a fairly even split. The most requested improvement (five responses)

was for better web-based or online mapping options. Four states reported that they would like

improved stability, and three states each said they would seek greater ease of use and more

customization options. Other improvements states would like were:

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 33

• More options for designing and publishing maps;

• More reporting options;

• Lower cost;

• Public submission capabilities;

• Open source technology

• Automation; and

• Better customer service.

Public input. The survey asked whether states accepted public map submissions. This

is another question Altman et al (2005) asked regarding the 1990 and 2000 redistricting cycle.

39 respondents (86.7 percent) accepted public submissions in 2010. This compares to 81

percent of states in 2000 and 61.5 percent of states in 1990 (Altman et al, 2005, p339). Most of

our respondents did not know how many submissions they received from the public. Three

states said they received none. 15 states received between 1 and 10 submissions, and 6 states

received between 10 and 90. Seven states reported receiving more than 90 public

submissions. Four of those – California, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas – were among the

five most populous states to respond to the survey. The other three are Arizona, Idaho, and

Utah. Arizona’s new redistricting commission generated a good deal of public attention, which

may have led to the high number of submissions, and both Idaho and Utah offered online tools

through which members of the public could easily submit maps. Idaho noted that they used

Mapitude Online to provide this service, and Utah developed its site with Esri (Hesterman,

2011). Three states (Delaware, Hawaii, and Kansas) said staff reviewed the public maps for

technical and legal compliance before distributing them to legislators or commissioners. Most

states that received maps from members of the public submitted them directly to legislators or

commissioners for their consideration. A few also posted them publicly. Though we did not ask

whether the public submissions influenced decisions, as nonpartisan staff are often unable to

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 34

answer this kind of question, when asked what was done with the publicly generated maps, only

Montana mentioned using them to develop commission proposals.

Other methods states used to solicit public input on the redistricting process are detailed

in Table 7. Most states conduct public hearings, a process familiar to legislative bodies, and 12

states said public hearings were the only method they used to gather public input.

Table 7: Public Input to the Redistricting Process

Method of Input

Number of States Offering

This Option Percent of

Respondents Public Hearings 42 93.3%

Dedicated Email Box or Phone Line 23 51.1%

Comment Form on a Website 15 33.3%

Additionally, seven states reported that they provided public work stations with mapping

software where members of the public could create redistricting maps. We did not ask about

this specifically, so it is possible more states provided this option. Altman et al (2005) reported

that 15 states in 1990 and 18 states in 2000 provided public terminals, web sites, or software for

public map creation.

Resources

NCSL was interested in evaluating its existing redistricting resources and seeking

suggestions for future projects. Respondents were asked to rate six existing NCSL redistricting

resources:

1. Redistricting Law 2010, also known as the Red Book, is NCSL’s “comprehensive treatise on redistricting law” (p vii). It is updated every ten years by members of NCSL’s Redistricting and Elections Standing Committee, as well as NCSL and U.S. Census Bureau staff, and it is available online and in hard copy.

2. The 2010 Redistricting Cases web page (http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting/2010-redistricting-cases.aspx) compiled cases from the 2010 redistricting cycle. It was last updated at the beginning of 2012. NCSL maintained similar pages for the 2000 and 1990 cycles.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 35

3. NCSL’s main redistricting web page (http://www.ncsl.org/research/redistricting.aspx) includes information on several specific topics and is updated as new NCSL research is completed.

4. Redistricting sessions are offered annually at the Legislative Summit, NCSL’s major annual membership convention.

5. Redistricting sessions are also offered at the Capitol Forum, NCSL’s annual policy

and lobbying meeting. 6. Stand-alone redistricting meetings have been offered in the past specifically for

legislative staff working on redistricting.

The rating options were: very useful, somewhat useful, not very useful, or not useful at all.

Respondents could also indicate that they were unfamiliar with the resource. I coded the ratings

on a scale of 1-4, with 1 being not useful at all and 4 being very useful, and then found the

mean. The results, along with a tally of those unfamiliar with each resource, are summarized in

Figure 8. This shows that respondents overall find all the NCSL resources useful, and nearly all

of them are familiar with the resources. The only resource with which more than a quarter of

respondents were unfamiliar is the Capitol Forum, which is the smaller of NCSL’s two annual

meetings.

Figure 8: Usefulness of and Familiarity with NCSL Resources

3.76 3.71

3.41 3.39 3.383.18

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

1.00

1.50

2.00

2.50

3.00

3.50

4.00

Red Book StandaloneMeetings

Summit CapitolForum

Cases Page Website

Num

ber U

nfam

iliar

Aver

age

Ratin

g

Average Rating Number Unfamiliar

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 36

The resource respondents singled out most frequently in open-ended comments as

being especially useful was the standalone redistricting meetings, particularly sessions involving

hands-on practice drawing maps and participation from the U.S. Census Bureau. Several

respondents mentioned the Red Book as well. The complete responses to this question are

compiled in Appendix C.

We also asked states what other resources they used to stay informed about

redistricting. Half the respondents said they used their software vendors, consistent with our

other responses indicating that states want additional GIS expertise and training. These

responses are summarized in Table 8.

Table 8: Redistricting Resources

Resource Number of States

Using This Resource Software Vendors 21 Academic or Think Tank Websites 16 Professional Consultants 14 Other: Elected Officials and Former Elected Officials 3

Other: Political Parties 3 Other: Lawyers and Professors 2

Finally, we asked for suggestions of additional resources NCSL could provide for the

2020 cycle. In general, these suggestions were that existing resources be updated and

continued, including email updates and standalone redistricting meetings. Two respondents

specifically requested additional GIS training opportunities. Other suggestions included a

summary of legal changes over the last decade, timetable of Census product availability, and

additional information about redistricting commissions. Complete responses to this question are

compiled in Appendix C.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 37

Discussion and Conclusion Our findings address a number of areas of the redistricting process that should be useful

as NCSL fields questions from its members. Many results can now be provided to state

legislative staff who have asked for specific information. State legislators are often interested in

comparing what their state does with what other states do. Personally, as a legislative staff

person often asked to provide this information to legislators, I love when NCSL has collected

data on a question I am researching, and my hope is that this survey will help NCSL have some

answers at the ready.

The survey shows that most states that do not already use a redistricting commission

have seen proposals to move to one. This indicates that there is significant interest in

redistricting commissions, and their creation will likely be a topic for NCSL to continue to

research. It also shows that not a lot is known about how states apply their open records laws

to redistricting records, which may be worthy of further study.

Survey findings provide justification for NCSL support in the redistricting process.

Almost none of our respondents work exclusively on redistricting issues. And while they are

overall confident in their states’ ability to manage the redistricting process, 82 percent think at

least a quarter of their redistricting staff in 2020 will be new to redistricting, and 27 percent think

almost all their staff will be. With an average of 10 people staffing redistricting in each state,

that is a large number of new staff. NCSL’s unique nonpartisan role puts it in a place to reach

these staff and provide resources they can use. Since 30 percent of respondents have already

begun preparing for the next redistricting cycle or will begin within the next year, it is not too

early to begin thinking about what those resources will look like.

With that in mind, our survey found that states find NCSL’s existing resources to be

useful overall. The resources respondents found most useful are the Red Book and standalone

redistricting meetings, so this gives NCSL some areas on which to focus. While we asked

about resources that stood out to our respondents and sought suggestions for other resources,

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 38

these questions did not generate a lot of new information. However, looking at responses to

other questions can help guide the preparation of future resources.

More than half the survey respondents reported using their mapping software vendor as

a resource, and of the states that hired additional staff expressly for redistricting, 61 percent

said they were hiring for GIS expertise. This suggests an interest in continued education on GIS

technology. We can also tell from the comparison to technology used in 1990 and 2000 that a

lot can change over a decade. Since most states now use one of two vendors, NCSL may be

able to facilitate early interaction with the vendors to meet states’ needs. 45 percent of

respondents are considering a new technology vendor for 2020, and if options remain limited,

the competition between the two vendors may be fierce. Additionally, several states expressed

an interest in pursuing additional online mapping offerings. Since Utah and Idaho reported

using this kind of tool in 2010, it would make sense to tap these staff to present on their work.

It is important to note the limitations of this survey. Responders were asked to recall

information, often from three or four years ago. Relying on their memory rather than recorded

information means that we cannot expect complete accuracy. Additionally, we were unable to

secure complete responses from all 50 states. The states not represented on the survey are:

Florida, Michigan, and South Carolina. By not capturing responses from Florida and Michigan,

we miss the third and tenth most populous states in the U.S. A few states provided only

minimal responses, and a few said their responses included, for example, only one chamber of

the legislature. Another limitation is the way different states responded to the survey. This is

particularly notable in the question about staff numbers. Some states gave exact numbers and

some provided ranges. Some included all agencies and staff types, some only included their

own. Better wording of the question, such as, “How many people were paid by the legislature to

work on redistricting?” may have yielded more definitive answers.

In conclusion, this survey provides valuable information about how the redistricting

process is conducted at the state level, including who staffs, the role of technology, and the

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 39

timeline for the 2020 redistricting cycle. It also offers insight to NCSL as to the redistricting

resources it can provide. The results should show a definite need for NCSL in the process, and

they suggest areas of interest to NCSL’s member states. By answering a number of discrete

questions, the survey helps prepare NCSL to answer member questions as they arise. My

compilation and analysis of the responses answer my research questions by explaining how the

process is administered and noting resources NCSL can provide.

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 40

References Altman, M., MacDonald, K., & McDonald, M. (2005). From Crayons to Computers The Evolution

of Computer Use in Redistricting. Social Science Computer Review, 23(3), 334–346. http://doi.org/10.1177/0894439305275855

Altman, M., & McDonald, M. P. (2014). Public Participation GIS: The Case of Redistricting. In Proceedings of the 47th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. Waikoloa, HI: Computer Society Press. Retrieved from http://www.computer.org/csdl/proceedings/hicss/2014/2504/00/index.html

An interstate process perspective on political gerrymandering. (2006, March). Harvard Law Review, 119(5), 1576+.

Ansolabehere, S., & Palmer, M. (2015). A Two Hundred-Year Statistical History of the Gerrymander. Presented at the Congress & History Conference, Vanderbilt University. Retrieved from http://www.vanderbilt.edu/csdi/events/ansolabehere_palmer_gerrymander.pdf

Arizona State Legislature v. Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. (2015, July). Retrieved September 12, 2015, from http://www.scotusblog.com/case-files/cases/arizona-state-legislature-v-arizona-independent-redistricting-commission/

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962). Burnett, K. D. (2011). Congressional Apportionment (2010 Census Briefs No. C2010BR-08) (p.

7). Washington, DC: US Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-08.pdf

Cain, B. E. (2012). Redistricting commissions: a better political buffer? Yale Law Journal, 121(7), 1808+.

Cameron, C., Epstein, D., & O’Halloran, S. (1996). Do Majority-Minority Districts Maximize Substantive Black Representation in Congress? The American Political Science Review, 90(4), 794–812. http://doi.org/10.2307/2945843

Cox, A. B. (2004). Partisan Gerrymandering and Disaggregated Redistricting. The Supreme Court Review, 2004, 409–451.

Davis v. Bandemer, 478 U.S. 109 (1986). Denniston, L. (2015, July 27). The new look at “one person, one vote,” made simple. Retrieved

September 23, 2015, from http://www.scotusblog.com/2015/07/the-new-look-at-one-person-one-vote-made-simple/

Fuentes-Rohwer, L. (2003). Doing Our Politics in Court: Gerrymandering, Fair Representation and an Exegesis into the Judicial Role. Notre Dame Law Review, 78(2), 527.

Gelman, A., & King, G. (1994). Enhancing Democracy Through Legislative Redistricting. American Political Science Review, 88(03), 541–559. http://doi.org/10.2307/2944794

Gray, V. (1999). Where do policy ideas come from in Minnesota? CURA Reporter, 29(2), 1–6. Grossback, L. J., & Peterson, D. A. M. (2004). Understanding Institutional Change Legislative

Staff Development and the State Policymaking Environment. American Politics Research, 32(1), 26–51. http://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X03256782

Hammond, S. W. (1996). Recent Research on Legislative Staffs. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 21(4), 543–576. http://doi.org/10.2307/440461

Hesterman, B. (2011, June 9). Redistricting committee launches site for public-drawn maps. Daily Herald. Provo, Utah. Retrieved from http://www.heraldextra.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/elections/redistricting-committee-launches-site-for-public-drawn-maps/article_e60e7524-aae4-576d-a256-39422f3d1b63.html

Howe, A. (2013, June 25). We gave you a chance: Today’s Shelby County decision in Plain English. Retrieved September 23, 2015, from http://www.scotusblog.com/2013/06/we-gave-you-a-chance-todays-shelby-county-decision-in-plain-english/

Redistricting Resources for Legislators and Legislative Staff 41

Issacharoff, S. (2002). Gerrymandering and Political Cartels. Harvard Law Review, 116(2), 593–648. http://doi.org/10.2307/1342611

Jackson, J. (2015, September 1). Response to Research Request: Average Legislator Length of Stay.

Jewell, M. E., & Whicker, M. L. (1994). Legislative Leadership in the American States. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.