Rainfall as an instrument of production in late nineteenth‐century Nanchilnadu, India

Click here to load reader

Transcript of Rainfall as an instrument of production in late nineteenth‐century Nanchilnadu, India

This article was downloaded by: [University of Leeds]On: 01 November 2014, At: 21:03Publisher: RoutledgeInforma Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number:1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street,London W1T 3JH, UK

The Journal of PeasantStudiesPublication details, including instructions forauthors and subscription information:http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fjps20

Rainfall as an instrumentof production in latenineteenth‐centuryNanchilnadu, IndiaM.S.S. Pandian aa Centre for Studies in Social Sciences , 10 LakeTerrace, Calcutta, 700 029, IndiaPublished online: 05 Feb 2008.

To cite this article: M.S.S. Pandian (1987) Rainfall as an instrument of productionin late nineteenth‐century Nanchilnadu, India, The Journal of Peasant Studies,15:1, 61-82, DOI: 10.1080/03066158708438352

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03066158708438352

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of allthe information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on ourplatform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensorsmake no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy,completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinionsand views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views ofthe authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis.The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should beindependently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor andFrancis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings,

demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoeveror howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, inrelation to or arising out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private studypurposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution,reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in anyform to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms & Conditions of accessand use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument ofProduction in late Nineteenth-Century

Nanchilnadu, India

M.S.S. Pandian*

In studies on Indian agriculture, conducted within the framework ofMarxian political economy, concrete analysis of productive forces isalmost absent. Given this deficiency in the existing literature, thepresent article analyses rainfall (a natural instrument of production)as a productive force in the agrarian system of Nanchilnadu duringthe late nineteenth century. Since productive forces cannot be analysedindependently of the production system as a whole, we have placedour analysis of rainfall as a productive force in the context of theagrarian system's overall capacity for reproduction.

Productive forces as they are found in concrete situations are one of the leastanalysed aspects of the Indian agrarian structure. For a proof of this short-coming in the existing literature one need not look beyond the set of paperson Indian agriculture which constitutes the now famous mode of productiondebate. In the debate, which was conducted within the framework of Marxianpolitical economy, productive forces were cursorily treated under the coverof unanalysed aggregative expressions like 'methods of cultivation', 'primitivetechnical level', 'reinvestment of surplus', 'labour displacing mechanisation'[Patnaik, 1972: A-146,147,149], 'capital accumulation', 'positive growth ofcapital' [Chattopadhyay, 1972: A-191] and 'value of the modern capitalequipment per acre of farm size' [Rudra, 1970: A-85]. When disaggregatedevidence is given, it is in terms of the number of power tillers, tractors,tubewells, etc., without locating their place in the labour process (throughwhich productive forces evolve of which they are part) and without indicatingtheir interconnectedness with, and their impact on, the production relation.

The inadequate interest in analysing the productive forces is further evidentfrom the fact that even while these authors discussed at length the impositionof bourgeois private property on Indian agriculture during the colonial period,seldom do we come across any reference to the impact of colonial intervention

* Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, 10 Lake Terrace, Calcutta-700 029 India. The ideas expressedin this article owe a great deal to my discussions with C. T. Kurien. A number of collegues atthe CSSSC, in particular A. K. Bagchi, Partha Chatterjee and Anjan Ghosh, helped me with theiruseful comments on an earlier draft. Terry Byres, Henry Bernstein and a referee of The Journalof Peasant Studies helped me in reworking a certain theoretical proposition which is central tothe arguments in the article. I am grateful to all of them.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

62 The Journal of Peasant Studies

on the productive forces extant in the country. Although there is considerableevidence available on this aspect of the colonial rule in the works of scholarslike Voelckar [1893] and Willcocks [1930], this was not treated as facts by theparticipants in the debate.

Any inadequate analysis of the productive forces has, at least, two seriousmethodological consequences. First, if productive forces are not analysedadequately, it will be impossible to establish the degree of contradiction/correspondence between the forces and the relations of production. Unlessone establishes the proximate level of contradiction/correspondence betweenthe forces and the relations, it is extremely difficult to arrive at an under-standing of the ability of the system to reproduce over time. Second, in certainconcrete situations, the production relation itself cannot be usefully exploredwithout analysing the productive forces, for the distinction between them insuch a situation is thin [Sayer, 1977: 83-7]. One may cite the often quotedexample of co-operation. Different forms of co-operation are a productiveforce so far as they help in exercising control over nature in the productionprocess, but at the same time they are part of production relations as well.

The above discussion is, however, not to deny the importance of the analysisdone by scholars like Whitcombe [1971] and Amin [1982] of productive forces.We do, however, emphasise that such studies are few and far between, andmore concrete studies on productive forces are essential.

Given this context, the present article has a modest aim: to add one moreconcrete study to the existing limited literature on productive forces. Thespecific objectives of the study are to analyse (i) rainfall as a productive forcein the late nineteenth-century agrarian system of Nanchilnadu, which wasdominated by small peasants; (ii) the degree of contradiction/correspondencebetween the productive force (that is, in this case rainfall in the labour process)and the existing production relations in the region; and (iii) the mechanismswithin the system which kept the contradictions between the forces and therelations of production under check so as to facilitate the reproduction of thesystem under 'normal' circumstances. Objectives (ii) and (iii) are based on ourunderstanding that productive forces cannot be analysed independently of theproduction system in its totality.

We have chosen rainfall as the main focus of our study for a specific reason.Rainfall is a natural instrument of production, so that 'individuals aresubservient to Nature' [Marx and Engels, 1976: 71], ' that is, people's extentof freedom over the nature-imposed conditions of necessity in the process ofproduction is limited. As this extreme lack of freedom over nature will bringinto sharp focus the systemic contradictions flowing from the nature of theproductive force, we have deliberately chosen rainfall as the subject of ourenquiry.

Our analysis in the article is essentially synchronie. Let us specify thereasons why we are adopting such a methodological course. As societiesalways exist in their making with change being the only thing of permanence,the level of contradiction/correspondence between the forces and the relationsof production keeps changing over time. Under this circumstance, the only

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 63

procedural possibility available to allow a treatment of the level of corre-spondence/contradiction between the forces and the relations is to chose ahistorical moment and to analyse the structure under scrutiny at that moment.The notion of a historical moment is used here not in the sense of stoppingtime but in the sense of specifying the time period within which the systemreproduces itself.

The article is divided into four sections. The first section introducesthe region of study, Nanchilnadu, and provides a brief description of thedistribution of the social product across the different agrarian classes in theregion during the late nineteenth century. In this section, I almost solelyemphasise the conditions of the peasantry for that is sufficient to explicatethe nature and consequences of rainfall as a productive force (which is thecore concern of the article). The second section analyses rainfall as found inthe labour process in Nanchilnadu agriculture and locates the contradictionsit has with the existing relations of production in the region. The third sectiondeals with the institutions found in the agrarian system of late nineteenth-century Nanchilnadu which helped to keep these contradictions in a state ofsuspended animation and helped the system to reproduce. The final sectionbrings together the conclusions of the article.

I. DISTRIBUTION OF THE SOCIAL PRODUCT

The study area, Nanchilnadu, is a sub-region in Southern Tamil Nadu coveringthe two taluks of Tovalai and Agastiswaram in the present-day Kanyakumaridistrict. During the historical period which the present article is concerned with,it formed part of the erstwhile princely state of Travancore. With the language-based reorganisation of the states in 1956, Kanyakumari district along withNanchilnadu was ceded to Madras state, the present Tamil Nadu.

The region has a rich tradition of irrigated paddy cultivation. The ety-mology of the word 'Nanchilnadu' itself bears evidence to the long historyof paddy cultivation in the region. 'Nanchil' in Tamil means plough andhence 'Nanchilnadu' means the country of ploughs. Again, 'Nanchai' inTamil means wet-land cultivation. Thus 'Nanchilnadu' could also meanthe country of wet land cultivation. A local proverb in the region confirmsthis. The proverb claims that the total paddy harvested in Kuttanad, thepaddy region in central Travancore, would be just sufficient as seed forcultivation in Nanchilnadu [Hatch, 1939: 210]. The coastal fringe of theregion was punctuated with coconut gardens, though never as extensively asin the rest of Travancore. The focus of the study is essentially the paddy tractswithin Nanchilnadu.

In Nanchilnadu there was a hierarchy of claims on the social product inagriculture. The theocratic state in Travancore along with the temples had theownership right over most of the land within the boundaries of the state(including Nanchilnadu). The state and temples collected rent in the form ofland revenue from those who possessed these lands.2 Below thestate/temples, there was a small rural elite who possessed substantial but

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

64 The Journal of Peasant Studies

not massive areas of the state/temple lands. These 'local landlords' primarilyleased out their land to tenants known in the region as pattakaran. Someportion of the lands of 'local landlords' was self-cultivated and on itagricultural labourers were employed. Then within the hierarchy come the mostnumerous section in Nanchilnadu's agrarian structure, the peasants. Theyeither possessed sufficient areas of state/temple land to sustain themselvesthrough self-cultivation, employing family labour, or supplemented thestate/temple land in their possession by renting in land from the 'locallandlords'. A section of the peasantry who could not secure sufficient landeither directly from the state/temples or from the 'local landlords', hiredthemselves out as agricultural labourers. At the bottom of the hierarchy, therewas a small class of agricultural labourers and artisans.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, 82.32 per cent of the total23,148.85 acres of registered or tax-paying land in Tovalai taluk and 73.36per cent of the total 43525.89 acres in Agasteeswaram taluk were owned bythe Travancore state [Aiyar, 1913: Appendix, clxxii-clxxiii]. These lands wereknown in the revenue records as Pandaravaka lands. In addition to this, theSri Padmanabhaswami temple in Trivandrum, which was considered to be themost important of the temples in Travancore state, owned about 4,800 acres ofland in Nanchilnadu.3 These lands were designated as Sri Pandaravaka lands.Further, there were 55 temples in Nanchilnadu managed by the Travancorestate, incurring Rs. 181,000 in maintenance cost per year [Travancore,1949: 51]. This set of temples included the famous Suchindram temple,which was a big landowner [Pillai, 1953: 292-8]. The lands owned by thesetemples were known as SircarDevaswomvaka lands. The rent on these landswas fixed and revised during the general revenue settlement arid collectedby the Revenue Department officials, as in the case of Pandaravaka lands.The same rules of revenue recovery, land acquisition and revenue remissionwere applied to all the three categories of land [Travancore, 1949: xviii-xix;and Travancore, 1952]. Thus, for all practical purposes, the Travancore stateowned Pandaravaka, Sri Pandaravaka and Sircar Devaswomvaka lands,though juridically they formed separate entities.

This land monopoly enabled the state to appropriate a substantial portionof the social product of agriculture in the form of land revenue, which leftthe peasants, operating state and temple lands, at the margins of subsistence.

In 1883, the best quality land in Nanchilnadu, which produced a gross outputof 18 kottas (approximately 1,350 kgs.)4 of paddy per acre per year, was tobear a land revenue assessment of ten kottas of paddy.5 Thus, about 56 percent of the gross output from land was extracted as land revenue from thepeasants. However, the proportion of the output that formed the land revenuedid not remain fixed over time. Since a part of the land revenue was to bepaid in the form of a fixed amount in cash, the proportion of the output thatwent as land revenue varied inversely with the price of paddy. But, whateverthe exact proportion of land revenue in the social product, its impact on thepeasantry in Nanchilnadu was harsh. Its consequences were vividly describedby the Dewan of Travancore as follows:

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 65

Notably in Thovalay and Agasteeswaram, the burden [of land revenue]is both onerous and unequal, the average rate of assessment being 18and 16 rupees per acre. The result is that notwithstanding a good systemof irrigation and annually recurring expenditure for its upkeep andnotwithstanding that the ryots are industrious and thrifty, complaintsof overassessment and the unequal incidence of Government demandare frequent; the margin of profit is said to be small; there is noaccumulation of capital; the bulk of the agricultural population are ableto derive but a bare subsistence from the land, and the first bad seasonreduces the bulk of the people to a struggle for existence.6

The fact of oppressive land revenue extraction and their resultant povertywas repeatedly raised by the peasants and often admitted by the revenueofficials, especially after the failure of the Revenue Settlement of 1883 -1911to alter the situation. And this was a matter for persistent complaints by theNanchilnadu peasantry during the first decade of the present century.7

Land revenue being the realisation of the land monopoly of not only thestate, but the temples also, the state shared the land revenue with the temples.Before 1922, the state met the actual expenditure needed to maintain the SriPadmanabhaswami as well as the Sircar temples. In 1922, the state resolvedto credit annually a sum equivalent to 40 per cent of the state's recurring landrevenue in favour of the sircar temples, apart from meeting the expenditureinvolved in maintaining the Sri Padmanabhaswami temple [Travancore, 1939].Thus, whatever the exact quantum of surplus appropriated by the state fromthe peasants in Nanchilnadu and shared with the temples, its impact on thepeasantry was very clear - it left them, in general, at the margin ofsubsistence.8

We have already mentioned the 'local landlords'. Unlike the northern partof Travancore, Nanchilnadu did not have a class of Jenmies, the indigenouslanded barons who paid a very light tax to the state only as a notion ofrecognising its authority. Out of the 15 important jenmies in Travancore in1873, none was from Nanchilnadu [Travancore, 1915: IV, 414]. There was onlya meagre 48.35 acres of Jenmon land in Nanchilnadu [Parameswaranpillai,1946: 60]. Instead, Nanchilnadu had the class of 'local landlords' each ofwhom held Pandaravaka and/or Sri Pandaravaka lands, normally rangingfrom ten to 30 acres. In rare instances, such households were in possessionof a hundred-odd acres of land. However, such families were, invariably, largematrilineal joint families of the vellala caste, each having 40 to 60 membersunder its fold.9

The condition of the peasants who operated the lands of the 'local landlords'was worse than that of the peasants who operated the state-owned landsdirectly by paying land revenue. This group of peasants were paying 12 kottasof paddy as rent on each acre of land leased in, for both the seasons in a year.The rent was paid in two instalments [Aiya, 1906: III, 151]. As the averageyield per acre for both the crops of paddy in a year was 18 kottas, the rentformed two-thirds of the gross output from land. Further, the landlords did

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

66 The Journal of Peasant Studies

not share any part of the cultivation cost. Thus, the share of the social productwhich was paid as rent by the peasants to the 'local landlords' was higher thanthe land revenue paid by the peasants who cultivated the state/temple landdirectly.10 This is not surprising, given that the whole of the rent did not goto enrich the 'local landlords'. A sizeable portion was paid to the state as landrevenue by the landlords.

Thus, the state, the temples and the 'local landlords' appropriated thelargest share of the total social product in Nanchilnadu agriculture during thelate nineteenth century, leaving the majority of the cultivating peasantry atthe risk-prone margins of subsistence.11

II. RAINFALL AS PRODUCTIVE FORCE

During the late nineteenth century, there were about 23,800 acres of paddyland in Nanchilnadu, of which about 26 per cent was classified as purely rain-fed [Aiyar, 1913: lxx]. I do not have precise information about the extent towhich different sources of irrigation-like tanks and canals accounted for theirrigated paddy area in the region. But the available limited data indicate that33.16 per cent of the total irrigated area in Nanchilnadu was supplied bygovernment canals, 66.0 per cent by tanks and the rest by wells and othersources.12

But the irrigation tanks and canals in Nanchilnadu were in such an un-maintained state that the failure or the success of the crops in the irrigatedtracts was decided to a great degree by rainfall. The condition of the tanksin Nanchilnadu was deplorable. During the beginning of each monsoon, muchwater went to waste given the extremely poor water-holding capacity of thetanks. Due to lack of water in the tanks during the later part of the crop cycle,often the paddy crop perished in the fields of Nanchilnadu [Travancore, 1908:I, 131]. Describing the extremely leaky and silted state of the canal systemin the region, a government report concluded, '... it is impossible that thepresent irrigation works can usefully sub-serve the purpose for which they areintended' [Ibid.: 41]. In fact, despite the irrigation works, crops in the irrigatedtracts of Nanchilnadu perished due to frequent droughts. Rainfall, therefore,had a prominent role in the paddy cultivation of Nanchilnadu during the latenineteenth century despite the fact that there were irrigation works in theregion.

Nanchilnadu received three-fourths of its annual rainfall during the South-West and the North-East monsoons [India, 1982: 78]. While the period of theSouth-West monsoon was from June to September, the North-East monsooncovered the period from the beginning of October to December. Of the twopaddy crops raised annually in the region, the first crop, known as the Kannicrop, was grown from mid-April to mid-September by utilising the South-Westmonsoon. The second paddy crop, which was known as the Kumbhom, grewfrom late September to mid-February and was cultivated by utilising the North-East monsoon.

In the context of utilising the monsoon cycle as an instrument of production

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 67

in crop husbandry, two important characteristics of the rainfall pattern inNanchilnadu need to be taken into account. First, the rainfall pattern in theregion was susceptible to wide variations across seasons, making stability ofagricultural production in the peasants' holdings impossible. Second, giventhe need to synchronise the production cycle with the fairly long monsooncycle, paddy cultivation evolved so as to create for peasants a long waitingtime for the realisation of their labour, so providing an entry point for usuryinto peasant households. These we explore in detail below.13

Instability of Rainfall Regime

First, let us take up the instability of the rainfall regime in Nanchilnadu foranalysis. In the absence of data for the period, statistics relating to the firsthalf of the twentieth century are used to a considerable extent. But rainfallbeing a geographical reality which is not amenable to dramatic changes ofpermanent nature in short periods, the inference, we suggest, is relevant tothe late nineteenth century.

Referring to the climatic insecurity of Nanchilnadu, Nagam Aiya [ 1906:III, 132-3] observed:

The vagaries of the seaons affect the South [Nanchilnadu] the easiest,earliest and most intensely. Though there is a well devised system ofirrigation, yet actual experience during the last two decades [August 1884to August 1904] has abundantly shown that much yet remains to be doneto ensure to those parts of the country protection against deficient orirregular rainfall.

The same view was expressed in the Settlement Final Report:

The vicissitudes of season and precariousness of the local rainfall aremore marked and failure of crops more frequent here [in Nanchilnadu]than in most other parts [of Travancore]. Even an average season affordsno adequate protection generally. Once a failure occurs, the depressionis great and not easily got over. The ryots have nothing to fall backupon.14

An index one can depend upon to understand the climatic insecurity is thenumber of times in a given period rainfall was less than normal in consecutiveyears. Even one year's lack of production due to deficient rainfall candestabilise the peasant's normal scheme of things by posing a threat to hislivelihood. Given this fact, the emphasis on the consecutive years of deficiencyin the normal rainfall will bring out the gravity of the situation sharply.

In Agastiswaram taluk, during the 1910s for three consecutive years andduring the 1930s for five consecutive years, the rainfall was less than normal.InTovalai taluk, during the 1910s for three consecutive years, during the 1920sfor three consecutive years, and during the 1930s for six consecutive years,the rainfall was less than normal {India, 1982: 92-3].

Further, the extent of rainfall across months, of great importance from

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

68 The Journal of Peasant Studies

the point of view of the water requirement of paddy crop, was also subjectto great variation in Nanchilnadu. Examination of data of monthly rainfallfor Agastiswaram taluk from 1901 to 1977, showed that the '... monthlycoefficient of variation is more than 50 per cent for all the months thusindicating the erratic nature of rainfall in all the months in the year' [Ibid.:97]. The same conclusion was arrived at for the Tovalai taluk, after a studyof the monthly rainfall data from 1916 to 1977. In Tovalai taluk, however,the month of October was found to be an exception [Ibid.: 98].

As a consequence of the fluctuation in the rainfall season after season,droughts were frequent in the region. Data on the number of drought yearsand the intensity of droughts are given in Tables 1 and 2. The data werearrived at by using the 'water balance method' which takes into accountimportant factors like moisture availability in the soil and evapo-transpirationlosses.15

Between 1901 and 1940, Agastiswaram taluk experienced drought for 20years, that is, on an average, every second year was a drought year. In 11 yearsthe drought was severe. During the period 1916 to 1945, Tovalai talukexperienced drought for 12 years, with severe or disastrous drought in fouryears.16

TABLE 1DROUGHT YEARS IN AGASTISWARAM TALUK, 1901-40

Decade Years of droughtModerate Large Severe

1901-10 - - 19041905

1911-20

1921-30

1931-40

—-

1909-

_19141916-

_-

1931___

—__

1910_

1913-—-__

1930_—___

19061908_-

1911—-—

1917

19211928-_

1934193519371938

1940

Source: India [1982: 3821.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 69

TABLE 2

DROUGHT YEARS IN TOVALAI TALUK

Decade Years of droughtModerate Large Severe Disastrous

1916-25 - 19161917 -

1921

1926-35 1928 - -1931 - -

19341935

1936-45 - - 19371938 - -1939 -1942 -

- 1945

Source: India [1982: 384].

The fluctuations in annual rainfall necessarily meant that access to wateras a productive force or as a natural instrument of production in agriculturewas not stable. Consequently, neither was the total social product resultingfrom crop husbandry. This variability in the total social product could be ofserious adverse consequence to the peasantry, if, even during times of normalproduction, they did not have a comfortable margin over subsistence. Thus,such a configuration held out the threat of usury and land alienation for thepeasants in Nanchilnadu. To restate, the described process was a threat to thereproduction of the system over time.

Monsoon Cycle and Crop Cycle

Given the time structure of the monsoons, the peasants in Nanchilnadu hadchosen different varieties of paddy for each of the monsoon periods. This wasthe only way by which the peasants could use the monsoons in an effectivemanner as a natural instrument of production in raising the paddy crop.

Ploughing and raking operations for the Kanni crop were usually begunin Nanchilnadu by the middle of April.17 By the end of April, seeds weresown which sprouted five days later. All these operations were done withoutmuch water. One may note here that none of the 20 varieties of seeds generallyused for the kanni crop in Nanchilnadu was transplanted. All of them weresowing varieties [ Velupillai, 1940, III, 303 -7] . While transplanting is a water-consuming technique, sowing is not.18 Once the seeds are sprouted, the fieldwas left to the sun to be scorched without any water for a period of about25 days. This dry period corresponded with the almost rainless month of May.Interestingly, 'it is a matter of great importance to the rice plant that its dryingperiod should not be disturbed by falling rain during the twenty-five or thirty

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

70 The Journal of Peasant Studies

days after its sprouting, as the yield will suffer materially if rain falls duringthis interval' [Aiya, 1906: HI, 28]. The watering of the plants was begun atthe beginning of June when the South-West monsoon usually breaks. Theharvesting of the crop was done after mid-September just before the North-East monsoon set in, for harvesting cannot be carried out effectively duringrains. The kanni crop occupied the field, thus, for five months.

For the kumbhom crop - the second paddy crop in Nanchilnadu whichoccupied the field from late September to mid-Februrary — the ploughingand transplanting operations were begun immediately after harvesting thekanni crop, with the onset of the North-East monsoon. As at the beginningof the crop cycle itself sufficient water was brought in by the monsoon, thevarieties of paddy chosen by the peasants were generally transplanting ones.Out of the 63 varieties of paddy used for the kumbhom crop in Nanchilnadu,31 varieties were transplanting varieties [Ibid.]. The crop normally requiredwater up to the middle or end of January, while the cycle of the North-Eastmonsoon terminates in December. Thus, there was a rough correspondencebetween the crop and monsoon cycles. In the case of the kumbhom crop, thefield should be drained of water and dried for about 15 days before the harvest.This drying period fell in January or February, the two driest months in theyear. The harvesting of the crop was done in the beginning or middle ofFebruary. Thus, the Kumbhom crop normally occupied the field for aboutfive months.

Thus, the time structure of the paddy varieties chosen in Nanchilnaduhad effectively operationalised the monsoon cycles as an instrument ofproduction.19 However, this dependence on nature had its other conse-quences: it was capable of generating weaker moments in the structure of thesystem. To understand this aspect of the concrete, let me briefly digress intocertain necessary concepts.

The starting point in this regard is the concepts of working period andproduction time, developed by Marx.20 Marx developed these concepts withrespect to capitalist forms of production, but their relevance here, in thecontext of pre-capital forms, will be obvious.

Marx stressed that in most branches of industry, production time, that is,the time taken to produce a finished product from the start to end, is equalto the working period, that is, the time during which the object of labour isunder the labour process. But in most branches of agriculture, production timeconsists of two sub-periods: (a) as in industry, a working period, in which'capital is engaged in the labour process', and (b) 'a second period in whichits [capital's] form of existence - that of an unfinished product - is handedover to the sway of natural processes without being involved in the labourprocess' [Marx, 1974:243]. For instance, in the case of cereal crops 'betweenthe time of sowing and harvesting the labour process is almost entirelysuspended' [Ibid.: 242] and what holds sway during this period is nature. Asin capitalist agriculture, so in a pre-capitalist context such as peasant pro-duction in late nineteenth-century Nanchilnadu, these consideration hold. Wemust, of course, distinguish the two cases.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 71

In the capitalist case, the 'second period', or non-working componentof production time, extends the time during which capital is tied to pro-duction. This extended period for which capital is locked in the productionprocess does not add to the total product, since the labour power expendedduring this period is zero. An important implication is that the non-labourtime component depresses the relative rate of return from agriculture comparedto industry. So, 'agriculture can never be the sphere in which capital starts'[Marx, 1981: 669] that is, capitalist relations of production emerge in agri-culture later than in industry.21 For peasants, however, unlike capital, thecentral issue is the need to wait for harvest time in order to realise theirlabour, in the form of means of consumption.22 They are prone, therefore,to borrow to meet their consumption needs. Thus the non-working periodcomponent of production time can lead the peasantry into usury.23

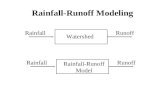

Let us now return to the specifics of paddy crops in Nanchilnadu interms of production time and working period so as to understand its impli-cations for the peasants. Our description of the time structure shows thatboth the kanni and kumbhom crops were long-duration ones, togetheroccupying the field for about 300 days in a year.24 During this substantiallylong production period, the time during which labour was applied for differentoperations (that is, the working period) was only a fraction. We have triedto present the working period and non-working period components of theproduction time as found in Nanchilnadu in Figure 1. The shaded portionof the figure gives the time period when the land was chiefly under thelabour process, and the unshaded, the period when the field was left pre-dominantly to the sway of natural processes. The figure shows that thelong production time in Nanchilnadu agriculture was basically due to longstretches of non-working period within the production time. Only for about30 to 40 per cent of the total length of the crop cycle was the land underthe labour process.

The implication of this difference between production time and workingperiod in a small peasant agrarian system like Nanchilnadu is evident.We see the pressures which drove peasants towards borrowing even forconsumption purposes and which thus pave the way for usury.

The arguments of the present section may be brought together. Theavailability of water for irrigation varied with the seasons in Nanchilnadudue to variations in rainfall, resulting in the fluctuation of total socialproduct and the portion of it retained by the peasantry from season toseason. Further, the time structure of the crop, as it evolved in consonancewith the monsoons, was such that there was a considerable difference betweenthe production and the working periods. These conditions which arosefrom utilising rainfall as a natural instrument of production in crop husbandry,in conjunction with the poor economic condition of the bulk of the peasantryin the region, provided the basis for usury, and ultimately land alienationand class differentiation in Nanchilnadu agriculture.

The logical derivative of this configuration was the limited ability ofthe peasantry to reproduce its means of subsistence over time within the

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

72 The Journal of Peasant Studies

existing mode of production. This means, in other words, that the probabilityof the system failing to reproduce over time was very high.

FIGURE 1PERIODS WITHIN THE PRODUCTION TIME OF KANNI AND KUMBHOMCROPS IN NANCHILANDU WHEN LAND IS UNDER LABOUR PROCESS

Kann/ Crop

APRIL

MAY

JUNE

JULY

AUGUST

SEPTEMBER

Ploughing,raking andbroadcastingseeds

Weeding

Harvestingand

threshing

Kumbhotn Crop

Ploughingtransplantinand weeding

Weeding

Harvestingand

threshing

SEPTEMBER

OCTOBER

NOVEMBER

DECEMBER

JANUARY

FEBRUARY

Source: Aiya, 1906: III, 27-29

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 73

III. REPRODUCTION OF THE SYSTEM

However, the history of socio-economic formations shows that every for-mation evolves its own internal mechanisms so as to avoid up to a pointthe total breakdown of the system under 'normal circumstances'. Onecan cite several instances. In clan-based socio-economic formations, theperiodic redistribution of land, both in terms of quality and extent, wasdone in such a way that it kept in check the possibilities of inequality emergingwithin the system [Baden-Powell, 1972: 259, 275, 280]. In early class societies,the distribution of the product within the village was regulated to checkthe emerging inequality within the village [Neale, 1957: 226]. Again, therewas ritual inversion of roles performed in different parts of India in whichthe exploited took the role of the exploiter in festivals with calendric intervals.This acted as an ideological safety valve negating temporarily the possibilitiesof open class struggle [Guha, 1983: 30-36].

In the context of the two possible bases for the instability of the peasantryin reproducing itself in Nanchilnadu, one can locate two internal stabilisingmechanisms in the agrarian structure. These were: (i) the provision forremission of land revenue/rent during times of crisis; and (ii) commonproperty resources or free access to nature. In elaborating these stabilisingmechanisms, one can see how the incompatibilities between the productiveforces arid the distribution of the social product were narrowed to someextent in the agrarian system of Nanchilnadu.

Remission of Land Revenue/Rent

By the provision for remission of land revenue/rent during unfavourableseasons, the state shared with the peasants the risk arising out of climaticinstability. In other words, the state/local landlords altered the distributionof the social product in favour of the peasantry by remitting a portionof the land revenue/rent due.

Traditionally, three types of seasonal remissions were allowed for thewet lands in Nanchilnadu. They were: (i) Karivu or remission on accountof total failure of the crop; (ii) Tharisu or remission on account of landsleft fallow owing to deficiency of water for cultivation; and (ûï) Nanjamelpunjaor partial remission on account of wet land being cultivated with a drycrop owing to insufficient supply of water. An analysis of the data from1886-87 to 1905-6 shows that, on an average, Kodayar command areain Nanchilnadu was given an annual remission of Rs.40095 (Table 3).This amount was about 13 per cent of the annual land revenue demandon Nanchilnadu.25 Although there are no data on how much of this remittedamount was due to Tharisu, one can say that it should have been considerableduring seasons of severe drought.

Apart from the seasonal remissions, the state used the provision forremission to wipe out the land revenue arrears of the peasants from timeto time. During the years 1812, 1823, 1865, 1880, 1885 and 1899, the stateremitted the land revenue arrears of the previous years [Travancore, 1915:

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

74 The Journal of Peasant Studies

TABLE 3EXTENT OF REMISSION IN NANCHILNADU: 1886-87 TO 1905-6

Years Remission (in Rs)

1886-87 25,8361887-88 29,6631888-89 11,6241889-90 30,7171890-91 73,0711891-92 23,4961892-93 64,4051893-94 56,6321894-95 139,5611895-96 67,5041896-97 29,6471897-98 22,8451898-99 24,4811899-1900 37,1691900-1901 24,0651901-2 22,4571902-3 37,1721903-4 21,3711904-5 32,3061905-6 27,892

Total 801,912Average per year 40,096

Source: Travancore [1908: III, Appendix xxxii].

IV, 213, 269, 379, 437, 471 and 565]. Referring to one such remission madesometime in the mid-nineteenth century, Menon [1984; II, 461] observed

The first magnificent act of this Maha Rajah [Vanji Pala MarthandaVurmah] after his installation was to remit all the accumulated arrearsand other dues to the Government by the ryots, during a series of yearsand amounting to upward of a lac of Rupees. If the realisation of thesedues was insisted upon, many families would have been ruined, and forthis reason alone these items of arrears were allowed to remain un-collected... (emphasis added).

Thus, the provision for remission helped the peasants withstand a debt trapduring periods of bad harvest.

However, it would be wrong to think that the remission compensated fullythe loss incurred by the peasants during periods of unfavourable climate. Atthe beginning of the twentieth century, referring to tharisu remission theUnder-Secretary to government noted; 'the... actual amount of remission [InNanchilnadu] cannot really represent the loss to the ryots in past years bydeficient water supply... remission is refused when there is any grain on thestalk'.26 However, even the partial compensation provided by the remission

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 75

of land revenue diffused the subsistence crisis of the peasants during timesof inadequate harvest.

There are at least two reasons why the Travancore state remitted the landrevenue in Nanchilnadu during crop failures. First, Nanchilnadu had a longtradition of indigenous organisation which mobilised the people of the regionfor agitational politics when the tax demands of the state were felt to beexcessive. We may cite one instance of such agitation from the early eighteenthcentury as an example of a tradition which continued to be used by theNanchilnadu peasantry in struggles against the state at least up until the 1950s.During the early eighteenth century, the invading troops of the Nayak kingsravaged the crops in Nanchilnadu; the state not only failed to remit the landrevenue, but imposed new taxes to finance the war. The agitation by thepeasantry of the region, in this oppressive situation, was described thus:

The spirit of lawless defiance to the king's authority... reached its climaxwhen the people openly met and resolved to take the life of any manwho acted against the interest of the public therein assembled. Such aperson was to be treated as a common enemy and dealt with accordingly.The people also more than once abandoned their houses and took tothe neighbouring hills refusing to return to their villages unless the kingpromised redress to their grievances [Travancore, 1915: IV, 84].

Although more than 150 years separate this incident and the period of ourenquiry, the tradition of local assemblies and defiance continued well into thetwentieth century: collective refusal to pay tax when it was heavy, to participatein government auctioning of land to realise revenue arrears and to complywith new state regulations which eroded the relative freedom of the villagesfrom state jurisdiction. Given this political milieu remission stands as amechanism won by the peasants and at the same time employed by the stateto avert political defiance by the peasants.

Second, remission helped the rulers to articulate their paternalism towardsthe ruled. Remitting the arrears land revenue was often the first act of the rulerfollowing his/her accession to the throne [Ibid.: 379, 471]. This reinforcedthe legitimacy of the new ruler in the minds of the ruled. In 1824, the thenqueen of Travancore described her act of remitting revenue arrears as a '...special mark of favour and grace, which will remain as a lasting record of thepaternal sentiments of affection, regard and interest for the welfare of Hersubjects ...' [Ibid.: 271]. More interesting is what the queen expected fromthe people in return for the remission: 'For such extensive and substantialbenefits Her Highness has a right to expect a return; all Her Highness requiresis respect for law, orderly conduct, obedience to the public authority of theSirkar and a faithful discharge of all public demands' [Ibid.: 270].

Let us now turn to the tenants who cultivated the lands of the locallandlords. In the case of such tenants, there was no contractual agreementto the effect that the landlord would reduce the rent during bad seasons ortimes of natural calamities. But by custom the rent paid by the peasants inNanchilnadu was 'subjected to reduction in bad seasons'.27 Aiya [1906: III,

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

76 The Journal of Peasant Studies

151] noted, 'When the crop is not a fairly full one, owing to heavy flood ordeficient rainfall or late cultivation, the Kattu kuttagai tenant breaks downand calls upon his land-owner to supervise the harvesting, and make a fairreduction in thepattom amount [rent] agreed upon, for a deficient crop'. Theprocess was known as Kanganam. Usually, half the gross output was takenby the local landlords as rent while the tenants got the rest of the output andthe total hay.28

Kanganam, apart from its function of diffusing the subsistence crisis ofthe peasantry, reproduced the political power structure of personal dominanceand deference between local landlords and their tenants. The fact that thetenant had to break down before the landlord to get the rent remitted is anadmission of the powerlessness of the tenant in his relation to the landlordduring time of crisis. And the fact that the landlord remitted the rent reinforcedhis power over and paternalism towards the tenants. Here it may be noted thatthe relationship between the local landlords and their tenants in Nanchilnadu,during normal times, was one of personal domination and deference. Apartfrom paying the contracted rent, the tenants had to give bunches of bananasto the landlord during festivals in the local temple or in the landlords' familytemple, and supply wage-free labour during marriages and deaths in thelandlord's house.

Common Property Resources

Although the Travancore state intensified the commercial exploitation of theforests during the second half of the nineteenth century, the rights of thepeasants over the forest resources were basically left unaltered. During the1860s when the state was debating the issue of reserving the forests, it tookspecial note of the requirements of the peasants. In 1868, the Dewan noted:'The forests may be divided into two classes; first those which are close tovillage and secondly those which are far from them ... / would not interferewith such forests [first type]'.29 This position was reflected in the otheracts of the government also. During 1856-7, in the context of restrictinghill cultivation in Shencottah taluk, the state acted in such a fashion that'the privilege which the ryots had enjoyed of freely obtaining agriculturalimplements from the forests was continued to them' [Travancore, 1915: IV,349].

The state's non-intervention in the customary rights of the peasants overforest resources was pronounced in South Travancore. Although Travancorehad a Forest Department as early as 1817, for every practical purpose it wasabsent in South Travancore/Nanchilnadu till 1876 when the governmentprohibited felling of forest trees in Tovalai taluk [Bourdillon, 1893 : xxxvi]. Onlyin 1888 did the Forest Department start exercising control over the forests inSouth Travancore. Till then, 'the forests in South Travancore were in chargeof the Revenue Department and the Forest Department had no control overthem'.30 Writing in 1892 (that is, after the take-over of the forest in the regionby the department), Bourdillon, the Conservator of Forests, noted that in

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 11

Magendragiri hills, fuel-gatherers and cattle were allowed [Ibid.: 24]. Thus,the customary rights of the peasants over forests were still largely left un-touched during the late nineteenth century. This provided the peasants inNanchilnadu with free grazing fields,31 green manure, timber for implementsand fuel. Further, before the arrival of the Kodayar dam in the region in 1907,the irrigation management within the villages in Nanchilnadu had an autonomyof its own, independent of the state, and was done by communally organisedirrigation organisations. As a concomitant of this arrangement, the tank bedsand bunds were communally operated. Grazing facilities and green manurefound on them were accessible to the village as a whole. The green manureavailable on the tank bunds was generally used by the small peasants who didnot otherwise have access to dry land.32 Again, although the aboundingstretches of dry lands in Nanchilnadu were in the possession of individuals,the tenants of the 'local landlords' were allowed by custom to remove greenmanure from the dry lands of the landlords. In some cases, tenants werepermitted to graze their cattle in the landlords' dry lands.33

Thus, there was a set of institutional arrangements which made it feasibleto utilise the existing balance between crop and non-crop lands in reproducingcertain elements of the productive forces in Nanchilnadu. As an element ofthe existing property rights, the peasants had the freedom to claim fodder,green manure, small timber and other resources from these communalproperties. In appropriating these resources, the peasants did not expend anyportion of their social product.

These institutional arrangements had great relevance in the context ofpeasants' synchronising crop and monsoon cycles in their use of the latter asa natural instrument of production. The difference between production timeand working period entailed the peasants waiting an unduly long period torealise the labour invested in the production process and thus held out thepossibility of their being forced into the hands of usurers. Since, however,common property resources made a number of inputs used in the productionprocess of paddy - fodder, green manure, timber - accessible to peasantsfree of cost, conditions conducive to usury were moderated somewhat. Onlyin such a context could the peasantry, as they did in Nanchilnadu, arguepassionately in favour of long-duration crops.

IV. CONCLUSIONS

The essence of any enquiry into the productive forces is to disclose the inter-relationship (interaction) between people and nature in the process of pro-duction as specifically as possible. Proceeding thus, we have tried to analyse oneof the productive forces in Nanchilnadu agriculture, namely rainfall. Again,given our understanding that a meaningful analysis of the productive forces isnot possible unless it takes into account the production system in its totality, wehave related our analysis of the productive force to the existing productionrelations in Nanchilnadu. This has helped us to locate the contradictions in thesystem and to understand how it was reproduced despite these contradictions.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

78 The Journal of Peasant Studies

The most important means of production required for paddy cultivationin Nanchilnadu, next to land, was water. The peasants in the region utilisedthe monsoon cycles as a natural instrument of production in irrigating theirpaddy plots. But the rainfall regime in the region was sufficiently unstableto render crop production extremely risk-prone. Hence, the amount of grainharvested across seasons fluctuated violently. Further, in utilising the monsooncycle as a natural instrument of production, the cultivators in Nanchilnaduevolved crop cycles in consonance with the monsoon cycles. This resulted ina longer production time, so compelling the peasants to wait for long periodsto realise the 'capital' and labour ploughed into the production process. Thusthe peasants in Nanchilnadu were subservient to the dictates of nature in theprocess of crop husbandry.34

These findings, when related to extant production relations, help in arrivingat the contradictions in the system and the 'suspension' of the contradictionsduring 'normal' periods. Locating the systematic contradictions is one of theprime concerns of political econony.

Given the adverse consequences of using rainfall as a natural instrumentof production in Nanchilnadu agriculture, ideally, unless all the farminghouseholds had sufficient surplus during the normal seasons, it would not bepossible for them to sustain deficits due to crop failures or to wait for a longperiod to realise the 'capital* and labour put into the production process.Turning to the actual distribution of the social product in Nanchilnadu, wefound that the state, the temples and the local landlords appropriated thelargest share of the total social product, given their superior rights over land.This left the peasants, who formed the majority of the working populationin Nanchilnadu countryside, with so little that they were kept at the marginsof subsistence even during the best of times. Thus, the actual distribution ofthe social product in Nanchilnadu did not correspond to the ideal patternoutlined. Given the actual pattern of distribution of the social product, thepeasants could not have survived bad harvests or the long waiting periodwithout borrowing, which would eventually lead them to alienate land. Thusthe prevalent distribution of the social product and the natural instrumentsof production were in tension.

However, the existence of such a contradictory correlation between theproductive forces and the production relations does not mean that the systemalways fails to reproduce itself. Each system has its own internal mechanismsor arrangements which keep the contradictions - within a stretch of historicaltime — in a state of dormancy or suspended animation.

In Nanchilnadu there were different mechanisms facilitating reproduction,despite the contradictions arising out of using rainfall as a productive force.First, the revenue/rent was remitted by the State/local landlords during timesof bad harvests due to adverse weather. This altered the distribution of thesocial product during crises in favour of the peasants and thus assured theirsurvival during such periods to some degree. Second, the land utilisationpattern in the region left large tracts of land untouched by crop husbandry,in the form of forests, uncultivated dry lands, and tank beds where inputs

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 79

required for paddy cultivation such as green manure, small timber and grazingfacilities were available in ample quantities. The prevailing institutionalarrangements, such as free access to forests, the local communities' rights overthe use of tank beds, and the customary claim of the peasants on the inputsavailable on the dry lands of the local landlords, provided these inputs freeof cost to the peasants. This, in turn, reduced the adverse impact of the longwaiting period on the peasantry. These mechanisms kept the contradictionsbetween the productive forces and the production relations in Nanchilnaduagriculture in a state of suspended animation to some degree.

In fact, during the first three decades of the twentieth century the state restric-ted the provision for remission and privatised the common property resources.This activated the latent contradictions in the agrarian system of Nanchilnadu,and resulted in marked agrarian change. That, however, is another story.

NOTES

1. In contrast to the natural instruments of production such as rivers and monsoon cycles, natureis the source of necessary material which, on being filtered through human labour formsinstruments of production, provides people with control over nature in the process ofproduction. Marx and Engels [1976: 71] differentiated these instruments of production asthose 'created by civilisation'.

2. Those who possessed the state/temple lands had 'heritable, saleable and otherwise transferablerights' over the lands in their possession, provided they paid the land revenue regularly anddid not allow the state to auction away the land for revenue recovery.

3. Calculated from the files of the South Travancore Maniamkaram Kandana Congress ActionCommittee, Kadukkarai, Tovalai Taluk.

4. One Kottai is approximately equal to 75 kgs.5. Settlement Final Report, Appendix No.II, Vol. III, Trivandrum, 1912, p. 550.6. Address Delivered by the Dewan of Travancore to the Leading Landholders on 24 March

1883, in Travancore Administration Report, 1882-83 (emphasis added).7. Diary of the Under-Secretary to the Government on Special Duty - Kodayar Assessment,

June-July 1907, in Public Works/1660/1907.8. In addition to the land revenue, the peasants were paying tax on necessities of life such as

salt, tobacco, toddy and arrack.9. Interview with Sivanpillai, Theroor, 19 Sept. 1984. To elaborate the point he cited the case

of his own family. The family in which his father was the karnavar (the eldest male memberwho managed the properties of the joint family), owned about 130 acres of land. But thefamily had more than 50 members in its fold. And when the lands were partitioned in 1926,his father and five brothers got a share of not more than 15 acres.

Vellalas are a land owning caste found throughout Tamil Nadu and are cultivators byprofession. But for in Nanchilnadu, they always followed patrilineal inheritance system. Duringthe 1920s the Vellalas of Nanchilnadu switched over from matrilineal inheritance system topatrilineal inheritance system.

10. Taking into account the extent of the social product in Nanchilnadu agriculture which wentto constitute the land revenue and rent, one can argue, 'rent here is the normal, all-absorbing,so to say the legitimate form of surplus labour...' and 'should any profit actually arise alongwith this rent, then this profit does not constitute the limit of rent, but rather conversely,the rent is the limit of the profit' [Marx, 1977; 793, 798).

An essential line of demarcation between the capitalist and pre-capitalist socio-economicformations is the position of profit and rent in the process of surplus extraction. While incapitalism profit sets the limit for rent, the converse is true in pre-capitalist societies.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

80 The Journal of Peasant Studies

11. In the course of the analysis, I have not dealt with agricultural labourers and artisans forthe reason that this would contribute little towards understanding rainfall as an instrumentof production.

12. Land Revenue/1000/1920.13. Here what is useful is the concepts of production time and working period developed by Marx

in respect of his treatment of capitalist industry and capitalist agriculture, but illuminating,too, in the context of peasant agriculture.

14. Final Settlement Report, Appendix No.II, Vol.III, Trivandrum, 1912, p. 549 (emphasisadded).

15. For details of the 'water balance method', see India [1982: 365-8].16. The frequent droughts in the region have given rise to certain popular cultural forms. During

droughts, the peasants make an effigy representing their accumulated sins, drag it along thestreets of the village and burn it at the end of the procession. Along the procession, theysing the usual funeral folk songs with two additional lines at the beginning, kodumbāvi san-dalai/ort ma Rai peyyādhō (Great sinner, great sinner, won't there be rain?) [Sivasubramanian,1981: 223].

17. All the information in the present and the next paragraphs are taken from Aiya [1906: III,27-9] unless indicated otherwise.

18. The choice of seeds to comply with the local conditions of nature is not rare. In the bird-infested Kolleru region in Andhra Pradesh, 'the grain of the local varieties develop what iscalled an awn or a mini thorn. The pick of the thorn acts as a deterrent against birds whichtry to prey on the grain' [Reporter, 1983].

19. In Nanchilnadu, by custom, any redemption of mortgage had to be done before the beginningof the agricultural year in the Tamil month of Chittirai which begins in mid-April. This customwas accepted by the Judiciary as well in its many decisions. For example see Travancore LawReport, Vol. XII, Trivandrum, 1926, pp. 111-13 (reprinted). Note that the operations forthe cultivation of the Kanni crop were begun in mid-April. Thus, the custom implies theinflexible crop rhythm of the region, the limits of which were obviously set by the monsoons.

20. The ideas in this paragraph and the next are from Marx [1974: Chs. 12 and 13] and Marx[1981: 668-70].

21. For a lucid presentation of this idea, see Mann and Dickinson [1978].22. One might employ the expression 'capital' loosely with respect to peasant production but

not in the sense of the notion integral to capitalism. Since commercialisation of agriculturecan antedate capitalism, even in pre-capitalist economies the assets in production need tobe expended and realised through the exchange sphere. For some of the empirical studiesin this regard in the context of India, see: Patnaik [1981] and Rastyannikov [1981]. This aspectof functioning through the exchange sphere, makes the assets in production even in pre-capitalist formations 'tied-up'. Thus, the notion of 'capital' might be employed in the senseof any asset in production in any socio-economic formation characterised by exchange relationsand not with respect to capitalism alone.

23. For a concrete study of the process in Eastern Uttar Pradesh during the colonial period, seeAmin [1982].

24. We have already elaborated that the crop cycle in Nanchilnadu followed the dictates of themonsoon cycle. However, for about 2.5 months during the production period of both thecrops, the cultivation operations were carried on outside the monsoon cycles. This naturallylengthened the duration of the production time beyond the limits set by the monsoons.

In this context, it may be noted that there was a positive relationship between the durationof the crop and the yield of paddy [ Vellupillai, 1940: III, 301]. Interestingly, this fact figuredprominently in the debates on the Public Works Department's proposal to substitute shorter-duration paddy in the place of long-duration ones, so as to minimise the demand for waterfrom the Kodayar dam. In the debate, it was noted: 'The varieties of paddy commonlycultivated are of long duration, but they have been found to be good yielders against shortduration varieties which give poor yield', and it was suggested that the proposals of the PWDcould not be entertained 'unless the agricultural and irrigation officers put their heads togetherand produce new varieties of paddy of short duration and of heavy yielding capacity'.(See Minutes of the Economic Development Board of Travancore, 24 April 1923, in

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

Rainfall as an Instrument of Production 81

Industries/D Dis 148/1923.) Further, in areas where the PWD was providing water for a singlecrop in a year, the peasants chose the paddy variety of the longest possible duration, and thiswas resented by the PWD (Chief Engineer to Chief Secretary, 21 Sept. 1929, in Revenue/D Dis2017/1940; and Division Officer, Nagercoil to Chief Engineer, 19 July 1926 in Revenue/D Dis2017/1940).

Thus, the long-duration paddy cultivated by the peasants of Nanchilnadu, apart from beingdictated by the monsoon rhythm, maximised output, which was an essential subsistencerequirement for the peasants.

25. The percentage figure would be an underestimate, since the figure of remission was for Kodayarcommand area in Nanchilnadu, which was a sub-set of Nanchilnadu. But the figure of annualland revenue demand used in the calculation was for Nanchilnadu as a whole.

26. Public Works/1658/1907.27. Settlement Final Report, Appendix No.II, Vol. III, Trivandrum, 1912.28. Interview with Sivathanupillai, Nagercoil, 14 Sept. 1984.29. Extracts from Dewan's Memo on Forests, 1868, in Section Book of Revenue Letters — 19

March 1868 to 22 August 1868 (emphasis added).30. Land Revenue/651/1904.31. In paddy cultivation, since the working period is considerably shorter than the production

time, cattle cannot be employed in production for a considerable period. Again, even withinthe working period, cattle can be employed only for a part of it as its employment is operation-specific. But the peasants have to maintain the cattle even when they are not employed inproduction. In this context, free access to grazing facilities is of great importance.

It may be noted here that, according to Boserup [1981:49], the mechanical energy suppliedby draft animals is only some five to six per cent of the energy contained in the fodder theyconsume. This low rate of conversion of energy will be of advantage to peasants, only ifthey can feed their animals on fallow and natural pastures free of cost.

32. Interview with S.I. Pandian Nadar, Agastiswaram, 17 Sept. 1984.33. Ibid.34. In the present-day context, we may note that ill-conceived irrigation works lead to water-logging,

salinity and drainage problems; the increased use of pesticides results in the death of thousandsof workers in Third World countries year after year and poisons the food-chain; threshers maimpeople; fertiliser use destroys the organic process in the earth which recurrently add to thefertility of the soil; increased use of high-yielding-variety seeds lead to the genetic degradationof the indigenous varieties of seed without which further research on seeds cannot be done. Allthese problems are directly relevant in understanding the meaning of people's domain offreedom over nature. However, these issues did not find a place in the analysis of productiveforces in the mode of production debate which dealt precisely with a period when these processeswere operative. The processes cannot be understood by simply listing the instruments of pro-duction as productive forces, but only by analysing them in the relationship of people andnature in production.

REFERENCES

Aiya, V. Nagam, 1906, The Travancore State Manual, Vols. I, II and III, Trivandrum: Governmentof Travancore.

Aiyar, S. Padmanabha, 1913, Revenue Settlement of Travancore 1886-1911 AD - Final Report,Trivandrum: Government of Travancore.

Amin, Shahid, 1982, 'Small Peasant Commodity Production and Rural Indebtedness: The Cultureof Sugarcane in Eastern U.P., c. 1880-1920' in Guha, Ranajit (ed.), Subaltern Studies I:Writings on South Asian History and Society, New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Baden-Powell, B.H., 1972, The Indian Village Community, Delhi: Cosmo Publications.Boserup, Ester, 1981, Population and Technology, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.Bourdillon, T.F., 1893, Report on the Forests of Travancore, Trivandrum: Government of

Travancore.Chattopadhyay, Paresh, 1972, 'Mode of Production in Indian Agriculture: An Anti-Kritik',

Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. VII, No. 53, 30 Dec.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014

82 The Journal of Peasant Studies

Guha, Ranajit, 1983, Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency in Colonial India, Delhi: OxfordUniversity Press.

Hatch, E.G., 1939, Travancore, Bombay, Calcutta and Madras: Oxford University Press.India, Government of, 1982, Report on Identification of Drought Prone Areas in District

Kanyakumari. Tamil Nadu, Hyderabad.Mann, Susan A. and James M. Dickinson, 1978, 'Obstacles to the Development of a Capitalist

Agriculture', Journal of Peasant Studies, Vol.5, No. 4, July.Marx, Karl, 1978, Capital, Vol.I, Moscow: Progress Publishers.Marx, Karl, 1974, Capital, Vol. II, Moscow: Progress Publishers.Marx, Karl, 1977, Capital, Vol. III, Moscow: Progress Publishers.Marx, Karl, 1981, Grundrisse, Middlesex: Penguin Books.Marx, Karl and Frederick Engels, 1976, The German Ideology, Moscow: Progress Publishers.Menon, P. Shungoonny, 1984, A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times, Vols.I and

II, New Delhi: Cosmo Publications.Neale, Walter G., 1957, 'Reciprocity and Redistribution in the Indian Village: Sequel to Some

Notable Discussions', in Karl Polyani, Conard M. Arensberg, and Harry W. Pearson (eds.),Trade and Market in Early Empires, New York: The Free Press.

Parameswaranpillai, P., 1946, Report on the Scheme for the Introduction of Basic Land Taxand the Revision of Agricultural Income Tax, Trivandrum: Government of Travancore.

Patnaik, Utsa, 1972, 'On the Mode of Production in Indian Agriculture', Economic andPolitical Weekly, Vol. VII, No.40, 30 Sept.

Patnaik, Utsa, 1981, Process of Commercialisation Under Colonial Conditions, Trivandrum,Centre for Development Studies, Nov. (mimeo).

Pillai, K.K., 1953, The Sucindram Temple, Madras.Rastyannikov, V.G., 1981, Agrarian Evolution in a Multiform Structure Society — Experience

of Independent India, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.Reporter, Vijayawada Staff, 1983, 'Falling Yields - A Paradox', The Hindu, 31 May.Rudra, Ashok, 1970, 'In Search of the Capitalist Farmer', Economic and Political Weekly,

Vol.V, No.26, 27 June.Sayer, Derek, 1977, Marx's Method, Brighton, Sussex: Harvester Press.Sivasubramanian, A., 1981, 'Mazhayum Nattar Vazhakiallum', in D. Loordu (ed.), Nattar

Vazhakattuyial Aivukkal, Vol.1, Tirunelveli: Parivezhl Publishers, (in Tamil).Travancore, Government of, 1908, Important Papers Relating to the Kodayar Project, Vols.I,

II and III, Trivandrum.Travancore, Government of, 1915, Travancore Land Revenue Manual, Vols.I, II, III and IV.

Trivandrum.Travancore, Government of, 1939, Travancore Devaswom Manual, Vol. II, Trivandrum.Travancore, Government of, 1949, Devaswoms in Travancore, Trivandrum.Travancore, Government of, 1952, Report of the Maniamkaram Committee of Travancore,

Trivandrum.Velupillai, T.K., 1940, The Travancore State Manual, Vols.I, II, III and IV, Trivandrum.Voelckar, J. A., 1893, Report on the Improvement of Indian Agriculture, London.Whitcombe, Elizabeth, 1971, Agrarian Conditions in Northern India: The United Provinces

Under British Rule 1860-1900. Vol.I, New Delhi: Thompson Press (India) Ltd.Willcocks, Sir William, 1930, 'Lectures on the Ancient System of Irrigation in Bengal and Its

Application to Modern Problems', University of Calcutta.

Dow

nloa

ded

by [

Uni

vers

ity o

f L

eeds

] at

21:

03 0

1 N

ovem

ber

2014