Public Sphere

-

Upload

sreenathpnr -

Category

Documents

-

view

29 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Public Sphere

Public sphere 1

Public sphere

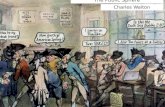

A coffeehouse discussion

The public sphere (German Öffentlichkeit, f) is an area in social lifewhere individuals can come together to freely discuss and identifysocietal problems, and through that discussion influence politicalaction. It is "a discursive space in which individuals and groupscongregate to discuss matters of mutual interest and, where possible, toreach a common judgment."[1] The public sphere can be seen as "atheater in modern societies in which political participation is enactedthrough the medium of talk"[2] and "a realm of social life in whichpublic opinion can be formed".

"The public sphere was coextensive with public authority". "Theprivate sphere comprised civil society in the narrower sense, that is tosay, the realm of commodity exchange and of social labor."[3] Whereasthe "Sphere of Public Authority" dealt with the State, or realm of the police, and the ruling class, the public spherecrossed over both these realms and "through the vehicle of public opinion it put the state in touch with the needs ofsociety."[4] "This area is conceptually distinct from the state: it [is] a site for the production and circulation ofdiscourses that can in principle be critical of the state." The public sphere 'is also distinct from the official economy;it is not an arena of market relations but rather one of discursive relations, a theater for debating and deliberatingrather than for buying and selling." These distinctions between "state apparatuses, economic markets, and democraticassociations...are essential to democratic theory." The people themselves came to see the public sphere as aregulatory institution against the authority of the state.[5] The study of the public sphere centers on the idea ofparticipatory democracy, and how public opinion becomes political action.

The basic ideal belief in public sphere theory is that the government's laws and policies should be steered by thepublic sphere, and that the only legitimate governments are those that listen to the public sphere. "Democraticgovernance rests on the capacity of and opportunity for citizens to engage in enlightened debate". Much of the debateover the public sphere involves what is the basic theoretical structure of the public sphere, how information isdeliberated in the public sphere, and what influence the public sphere has over society.

Definitions of the public sphereWhat does it mean that something is “public”? Jürgen Habermas says, “We call events and occasions ‘public’ whenthey are open to all, in contrast to closed or exclusive affairs”This notion of the public becomes evident in terms such as public health, public education, public opinion or publicownership. They are opposed to the notions of private health, private education, private opinion, and privateownership. The notion of the public is intrinsically connected to the notion of the private.Habermas stresses that the notion of the public is related to the notion of the common. For Hannah Arendt, the publicsphere is therefore “the common world” that “gathers us together and yet prevents our falling over each other”.Habermas defines the public sphere as a “society engaged in critical public debate”. Conditions of the public sphereare according to Habermas:•• The formation of public opinion•• All citizens have access.•• Conference in unrestricted fashion (based on the freedom of assembly, the freedom of association, the freedom to

expression and publication of opinions) about matters of general interest, which implies freedom from economicand political control.

Public sphere 2

•• Debate over the general rules governing relations.

Jürgen Habermas: bourgeois public sphereMain article: The Structural Transformation of the Public SphereMost contemporary conceptualizations of the public sphere are based on the ideas expressed in Jürgen Habermas'book The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere – An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society, whichis a translation of his Habilitationsschrift, Strukturwandel der Öffentlichkeit:Untersuchungen zu einer Kategorie derbürgerlichen Gesellschaft. The German term Öffentlichkeit (public sphere) encompasses a variety of meanings and itimplies a spatial concept, the social sites or arenas where meanings are articulated, distributed, and negotiated, aswell as the collective body constituted by, and in this process, "the public". The work is still considered thefoundation of contemporary public sphere theories, and most theorists cite it when discussing their own theories.

The bourgeois public sphere may be conceived above all as the sphere of private people come togetheras a public; they soon claimed the public sphere regulated from above against the public authoritiesthemselves, to engage them in a debate over the general rules governing relations in the basicallyprivatized but publicly relevant sphere of commodity exchange and social labor.[6]

Through this work, he gave a historical-sociological account of the creation, brief flourishing, and demise of a"bourgeois" public sphere based on rational-critical debate and discussion: Habermas stipulates that, due to specifichistorical circumstances, a new civic society emerged in the eighteenth century. Driven by a need for opencommercial arenas where news and matters of common concern could be freely exchanged anddiscussed—accompanied by growing rates of literacy, accessibility to literature, and a new kind of criticaljournalism—a separate domain from ruling authorities started to evolve across Europe. "In its clash with the arcaneand bureaucratic practices of the absolutist state, the emergent bourgeoisie gradually replaced a public sphere inwhich the ruler’s power was merely represented before the people with a sphere in which state authority was publiclymonitored through informed and critical discourse by the people".[7]

In his historical analysis, Habermas points out three so-called "institutional criteria" as preconditions for theemergence of the new public sphere. The discursive arenas, such as Britain’s coffee houses, France’s salons andGermany’s Tischgesellschaften "may have differed in the size and compositions of their publics, the style of theirproceedings, the climate of their debates, and their topical orientations", but "they all organized discussion amongpeople that tended to be ongoing; hence they had a number of institutional criteria in common":[8]

1. Disregard of status: Preservation of "a kind of social intercourse that, far from presupposing the equality ofstatus, disregarded status altogether. [...] Not that this idea of the public was actually realized in earnest in thecoffee houses, salons, and the societies; but as an idea it had become institutionalized and thereby stated as anobjective claim. If not realized, it was at least consequential." (loc.cit.)

2. Domain of common concern: "... discussion within such a public presupposed the problematization of areas thatuntil then had not been questioned. The domain of ‘common concern’ which was the object of public criticalattention remained a preserve in which church and state authorities had the monopoly of interpretation. [...] Theprivate people for whom the cultural product became available as a commodity profaned it inasmuch as they hadto determine its meaning on their own (by way of rational communication with one another), verbalize it, and thusstate explicitly what precisely in its implicitness for so long could assert its authority." (loc.cit.)

3. Inclusivity: However exclusive the public might be in any given instance, it could never close itself off entirely and become consolidated as a clique; for it always understood and found itself immersed within a more inclusive public of all private people, persons who – insofar as they were propertied and educated – as readers, listeners, and spectators could avail themselves via the market of the objects that were subject to discussion. The issues discussed became ‘general’ not merely in their significance, but also in their accessibility: everyone had to be able to participate. [...] Wherever the public established itself institutionally as a stable group of discussants, it did not equate itself with the public but at most claimed to act as its mouthpiece, in its name, perhaps even as its educator

Public sphere 3

– the new form of bourgeois representation" (loc.cit.).Habermas argued that the bourgeois society cultivated and upheld these criteria. The public sphere was wellestablished in various locations including coffee shops and salons, areas of society where various people couldgather and discuss matters that concerned them. The coffee houses in London society at this time became the centersof art and literary criticism, which gradually widened to include even the economic and the political disputes asmatters of discussion. In French salons, as Habermas says, "opinion became emancipated from the bonds ofeconomic dependence". Any new work, or a book or a musical composition had to get its legitimacy in these places.It not only paved a forum for self-expression, but in fact had become a platform for airing one’s opinions andagendas for public discussion.

Parliamentary action under Charles VII of France

The emergence of bourgeois public sphere was particularly supportedby the 18th century liberal democracy making resources available tothis new political class to establish a network of institutions likepublishing enterprises, newspapers and discussion forums, and thedemocratic press was a main tool to execute this. The key feature ofthis public sphere was its separation from the power of both the churchand the government due to its access to a variety of resources, botheconomic and social.As Habermas argues, in due course, this sphere of rational anduniversalistic politics, free from both the economy and the State, wasdestroyed by the same forces that initially established it. This collapsewas due to the consumeristic drive that infiltrated society, so citizensbecame more concerned about consumption than political actions.Furthermore, the growth of capitalistic economy led to an uneven

distribution of wealth, thus widening economic polarity. Suddenly the media became a tool of political forces and amedium for advertising rather than the medium from which the public got their information on political matters. Thisresulted in limiting access to the public sphere and the political control of the public sphere was inevitable for themodern capitalistic forces to operate and thrive in the competitive economy.

Therewith emerged a new sort of influence, i.e., media power, which, used for purposes ofmanipulation, once and for all took care of the innocence of the principle of publicity. The publicsphere, simultaneously prestructured and dominated by the mass media, developed into an arenainfiltrated by power in which, by means of topic selection and topical contributions, a battle is foughtnot only over influence but over the control of communication flows that affect behavior while theirstrategic intentions are kept hidden as much as possible.

Counterpublics, feminist critiques and expansionsAlthough Structural Transformation was (and is) one of the most influential works in contemporary Germanphilosophy and political science, it took 27 years until an English version appeared on the market in 1989. Based ona conference on the occasion of the English translation, at which Habermas himself attended, Craig Calhoun (1992)edited Habermas and the Public Sphere[9] – a thorough dissection of Habermas’ bourgeois public sphere by scholarsfrom various academic disciplines. The core criticism at the conference was directed towards the above stated"institutional criteria":1. Hegemonic dominance and exclusion: In Rethinking the Public Sphere, Nancy Fraser offers a feminist revision

of Habermas’ historical description of the public sphere, and confronts it with "recent revisionist historiography". She refers to other scholars, like Joan Landes, Mary P. Ryan and Geoff Eley, when she argues that the bourgeois public sphere was in fact constituted by a "number of significant exclusions." In contrast to Habermas’ assertions

Public sphere 4

on disregard of status and inclusivity, Fraser claims that the bourgeois public sphere discriminated against womenand other historically marginalized groups: "... this network of clubs and associations – philanthropic, civic,professional, and cultural – was anything but accessible to everyone. On the contrary, it was the arena, thetraining ground and eventually the power base of a stratum of bourgeois men who were coming to see themselvesas a “universal class” and preparing to assert their fitness to govern." Thus, she stipulates a hegemonic tendency ofthe male bourgeois public sphere, which dominated at the cost of alternative publics (for example by gender,social status, ethnicity and property ownership), thereby averting other groups from articulating their particularconcerns.

2. Bracketing of inequalities: Fraser makes us recall that "the bourgeois conception of the public sphere requiresbracketing inequalities of status". The "public sphere was to be an arena in which interlocutors would set asidesuch characteristics as difference in birth and fortune and speak to one another as if they were social andeconomic peers". Fraser refers to feminist research by Jane Mansbridge, which notes several relevant "ways inwhich deliberation can serve as a mask for domination". Consequently, she argues that "such bracketing usuallyworks to the advantage of dominant groups in society and to the disadvantage of subordinates." Thus, sheconcludes: "In most cases it would more appropriate to unbracket inequalities in the sense of explicitlythematizing them – a point that accords with the spirit of Habermas’ later communicative ethics".

3. The problematic definition of "common concern": Nancy Fraser points out that "there are no naturally given,a priori boundaries" between matters that are generally conceived as private, and ones we typically label as public(i.e. of "common concern"). As an example, she refers to the historic shift in the general conception of domesticviolence, from previously being a matter of primarily private concern, to now generally being accepted as acommon one: "Eventually, after sustained discursive contestation we succeeded in making it a common concern".

A Society of Patriotic Ladies at Edenton in NorthCarolina, satirical drawing of a women's counterpublic

in action in the 1775 tea boycott.

Nancy Fraser identified the fact that marginalized groups areexcluded from a universal public sphere, and thus it wasimpossible to claim that one group would in fact be inclusive.However, she claimed that marginalized groups formed their ownpublic spheres, and termed this concept a subaltern counterpublicor counterpublics.

Fraser worked from Habermas' basic theory because she saw it tobe "an indispensable resource" but questioned the actual structureand attempted to address her concerns. She made the observationthat "Habermas stops short of developing a new, post-bourgeoismodel of the public sphere". Fraser attempted to evaluateHabermas' bourgeois public sphere, discuss some assumptionswithin his model, and offer a modern conception of the publicsphere.In the historical reevaluation of the bourgeois public sphere, Fraserargues that rather than opening up the political realm to everyone,the bourgeois public sphere shifted political power from "arepressive mode of domination to a hegemonic one". Rather thanrule by power, there was now rule by the majority ideology. Todeal with this hegemonic domination, Fraser argues that repressedgroups form "Subaltern counterpublics" that are "parallel discursive arenas where members of subordinated socialgroups invent and circulate counterdiscourses to formulate oppositional interpretations of their identities, interests,and needs".

Benhabib notes that in Habermas' idea of the public sphere, the distinction between public and private issues separates issues that normally affect women (issues of "reproduction, nurture and care for the young, the sick, and

Public sphere 5

the elderly")[10] into the private realm and out of the discussion in the public sphere. She argues that if the publicsphere is to be open to any discussion that affects the population, there cannot be distinctions between "what is" and"what is not" discussed.[11] Benhabib argues for feminists to counter the popular public discourse in their owncounterpublic.The public sphere was long regarded as men's domain whereas women were supposed to inhabit the private domesticsphere. A distinct ideology that prescribed separate spheres for women and men emerged during the industrialrevolution.The concept of heteronormativity is used to describe the way in which those who fall outside of the basicmale/female dichotomy of gender or whose sexual orientations are other than heterosexual cannot meaningfullyclaim their identities, causing a disconnect between their public selves and their private selves. Michael Warnermade the observation that the idea of an inclusive public sphere makes the assumption that we are all the samewithout judgments about our fellows. He argues that we must achieve some sort of disembodied state in order toparticipate in a universal public sphere without being judged. His observations point to a homosexual counterpublic,and offers the idea that homosexuals must otherwise remain "closeted" in order to participate in the larger publicdiscourse.[12]

Rhetorical public sphere

Demonstration against French nuclear tests in1995 in Paris "This interaction can take the form

of ... basic "street rhetoric" that "open[s] adialogue between competing factions."

Gerard Hauser proposed a different direction for the public sphere thanprevious models. He foregrounds the rhetorical nature of publicspheres, suggesting that public spheres form around "the ongoingdialogue on public issues" rather than the identity of the group engagedin the discourse.[13]

Rather than arguing for an all inclusive public sphere, or the analysis oftension between public spheres, he suggested that publics were formedby active members of society around issues. They are a group ofinterested individuals who engage in vernacular discourse about aspecific issue. "Publics may be repressed, distorted, or responsible, butany evaluation of their actual state requires that we inspect therhetorical environment as well as the rhetorical act out of which theyevolved, for these are the conditions that constitute their individualcharacter". These people formed rhetorical public spheres that werebased in discourse, not necessarily orderly discourse but anyinteractions whereby the interested public engages each other. Thisinteraction can take the form of institutional actors as well as the basic "street rhetoric" that "open[s] a dialoguebetween competing factions." The spheres themselves formed around the issues that were being deliberated. Thediscussion itself would reproduce itself across the spectrum of interested publics "even though we lack personalacquaintance with all but a few of its participants and are seldom in contexts where we and they directly interact, wejoin these exchanges because they are discussing the same matters." In order to communicate within the publicsphere, "those who enter any given arena must share a reference world for their discourse to produce awareness forshared interests and public opinions about them". This world consists of common meanings and cultural norms fromwhich interaction can take place.

Public sphere 6

Political Graffiti on the South Bank of theThames in London 2005, "even though we lackpersonal acquaintance with all but a few of its

participants and are seldom in contexts where weand they directly interact, we join these

exchanges because they are discussing the samematters."

The rhetorical public sphere has several primary features:1. it is discourse-based, rather than class-based.2. the critical norms are derived from actual discursive practices.Taking a universal reasonableness out of the picture, argumentsare judged by how well they resonate with the population that isdiscussing the issue.3. intermediate bracketing of discursive exchanges. Rather than aconversation that goes on across a population as a whole, thepublic sphere is composed of many intermediate dialogs thatmerge later on in the discussion.

The rhetorical public sphere was characterized by five rhetorical normsfrom which it can be gauged and criticized. How well the public sphereadheres to these norms determine the effectiveness of the public sphereunder the rhetorical model. Those norms are:

1. permeable boundaries: Although a public sphere may have aspecific membership as with any social movement ordeliberative assembly, people outside the group can participatein the discussion.

2. activity: Publics are active rather than passive. They do notjust hear the issue and applaud, but rather they actively engage

the issue and the publics surrounding the issue.

3. contextualized language: They require that participants adhere to the rhetorical norm of contextualizedlanguage to render their respective experiences intelligible to one another.

4. believable appearance: The public sphere must appear to be believable to each other and the outside public.5. tolerance: In order to maintain a vibrant discourse, others opinions need to be allowed to enter within thearena.

In all this Hauser believes a public sphere is a "discursive space in which strangers discuss issues they perceive to beof consequence for them and their group. Its rhetorical exchanges are the bases for shared awareness of commonissues, shared interests, tendencies of extent and strength of difference and agreement, and self-constitution as apublic whose opinions bear on the organization of society."

The media and the public sphereHabermas argues that the public sphere requires “specific means for transmitting information and influencing thosewho receive it”Habermas’ argument shows that the media are of particular importance for constituting and maintaining a publicsphere. Discussions about the media have therefore been of particular importance in public sphere theory.

The media as actor in the political public sphereAccording to Jürgen Habermas, there are two types of actors without whom no political public sphere could be put towork: professionals in the media system and politicians. For Habermas, there are five types of actors who make theirappearance on the virtual stage of an established public sphere:

(a) Lobbyists who represent special interest groups;

Public sphere 7

(b) Advocates who either represent general interest groups or substitute for a lack of representation ofmarginalized groups that are unable to voice their interests effectively;(c) Experts who are credited with professional or scientific knowledge in some specialized area and are invitedto give advice;(d) Moral entrepreneurs who generate public attention for supposedly neglected issues;(e) Intellectuals who have gained, unlike advocates or moral entrepreneurs, a perceived personal reputation insome field (e.g., as writers or academics) and who engage, unlike experts and lobbyists, spontaneously inpublic discourse with the declared intention of promoting general interests.

Limitations of media and the internet as a public sphereSome, like Colin Sparks, note that a new global public sphere ought to be created in the wake of increasingglobalization and global institutions, which operate at the supranational level.[14] However, the key questions for himwere, whether any media exists in terms of size and access to fulfil this role. The traditional media, he notes, areclose to the public sphere in this true sense. Nevertheless, limitations are imposed by the market and concentration ofownership. At present, the global media fail to constitute the basis of a public sphere for at least three reasons.Similarly, he notes that the internet, for all its potential, does not meet the criteria for a public sphere and that unlessthese are ‘overcome, there will be no sign of a global public sphere’.

The public sphere and the information ageJürgen Habermas mentions in 'Further Reflections on the Public Sphere' about the information age:

"Many of the features of our ‘Information Age’ make us resemble the most primitive of social andpolitical forms: the hunting and gathering society. As nomadic peoples, hunters and gatherers have noloyal relationship to territory. They, too, have little “sense of place”; specific activities are not totallyfixed to a specific physical settings. The lack of boundaries both in hunting and gathering and inelectronic societies leads to many striking parallels. Of all known social types before our own, huntingand gathering societies have tended to be the most egalitarian in terms of the roles of males and females,children and others, and leaders and followers."

Mediated publicnessJohn Thompson criticises the traditional idea of public sphere by Habermas, as it is centred mainly in face-to-faceinteractions. On the contrary, Thompson argues that modern society is characterized by a new form of “mediatedpublicness”, which main characteristics are:•• Despatialized (there is a rupture of time/space. People can see more things, as they do not need to share the same

physical location, but this extended vision always has an angle, which people do not have control over).•• Non dialogical (unidirectional. For example, presenters on TV are not able to adapt their discourse to the

reactions of the audience, since they are visible to a wide audience but that audience is not directly visible tothem. However, internet allows a bigger interactivity).

•• Wider audiences (the mediated characteristic allows to reach a wider range of people in different contexts. Thesame message can reach people with different education, different social class, different values and beliefs, and soon).

This mediated publicness has altered the power relations in a way in which not only the many are visible to the fewbut the few can also now see the many:

"Whereas the Panopticon renders many people visible to a few and enables power to be exercised overthe many by subjecting them to a state of permanent visibility, the development of communicationmedia provides a means by which many people can gather information about a few and, at the same

Public sphere 8

time, a few can appear before many; thanks to the media, it is primarily those who exercise power,rather than those over whom power is exercised, who are subjected to a certain kind of visibility".

However, Thompson also acknowledges that “media and visibility is a doubled-edged sward” meaning that eventhough they can be used to show an improved image (by managing the visibility), individuals are not in full controlof their self-presentation. Mistakes, gaffes or scandals are now recorded therefore they are harder to deny, as theycan be replayed by the media.

The public service modelExamples of the public service model include BBC in Britain, and the ABC and SBS in Australia. The politicalfunction and effect of modes of public communication has traditionally continued with the dichotomy betweenHegelian State and civil society. The dominant theory of this mode include the liberal theory of the free press.However, the public service, state-regulated model, whether publicly or privately funded, has always been seen notas a positive good but as an unfortunate necessity imposed by the technical limitations of frequency scarcity.According to Habermas’s concept of the public sphere, the strength of this concept is that it identifies and stresses theimportance for democratic politics of a sphere distinct from the economy and the State. On the other hand, thisconcept challenges the liberal free press tradition form the grounds of its materiality, and it challenges the Marxistcritique of that tradition from the grounds of the specificity of politics as well.From Garnham’s critique, three great virtues of Habermas’s public sphere are mentioned. Firstly, it focuses on theindissoluble like between the institutions and practices of mass public communication and the institutions andpractices of democratic politics. The second virtue of Habermas’s approach concentrate on the necessary materialresource base for ant public. Its third virtue is to escape from the simple dichotomy of free market versus statecontrol that dominates so much thinking about media policy.

Non-liberal theories of the public sphereOskar Negt & Alexander Kluge took a non-liberal view of public spheres, and argued that Habermas' reflections onthe bourgeois public sphere should be supplemented with reflections on the proletarian public spheres and the publicspheres of production.

Proletarian public spheresThe distinction between bourgeois and proletarian public spheres is not mainly a distinction between classes. Theproletarian public sphere is rather to be conceived of as the "excluded", vague, unarticulated impulses of resistanceor resentment. The proletarian public sphere carries the subjective feelings, the egocentric malaise with the commonpublic narrative, interests that are not socially valorized

"As extraeconomic interests, they exist—precisely in the forbidden zones of fantasy beneath the surface oftaboos—as stereotypes of a proletarian context of living that is organized in a merely rudimentary form."

The bourgeois and proletarian public spheres are mutually defining: The proletarian public sphere carries the"left-overs" from the bourgeois public sphere, while the bourgeois public is based upon the productive forces of theunderlying resentment:

"In this respect, they " [i.e. the proletarian public spheres] " have two characteristics: in their defensive attitudetoward society, their conservatism, and their subcultural character, they are once again mere objects; but theyare, at the same time, the block of real life that goes against the valorization interest. As long as capital isdependent on living labor as a source of wealth, this element of the proletarian context of living cannot beextinguished through repression."

Public sphere 9

Public spheres of productionNegt and Kluge furthermore point out the necessity of considering a third dimension of the public spheres: Thepublic spheres of production. The public spheres of production collect the impulses of resentment andinstrumentalizes them in the productive spheres. The public spheres of production are wholly instrumental and haveno critical impulse (unlike the bourgeois and proletarian spheres). The interests that are incorporated in the publicsphere of production are given capitalist shape, and questions of their legitimity are thus neutralized.

Biopolitical publicBy the end of the 20th century the discussions about public spheres got a new biopolitical twist. Traditionally thepublic spheres had been contemplated as to how free agents transgress the private spheres. Michael Hardt andAntonio Negri have, drawing on the late Michel Foucault's writings on biopolitics, suggested that we reconsider thevery distinction between public and private spheres. They argue that the traditional distinction is founded on acertain (capitalist) account of property that presuppose clear-cut separations between interests. This account ofproperty is (according to Hardt and Negri) based upon a scarcity economy. The scarcity economy is characterized byan impossibility of sharing the goods. If "agent A" eats the bread, "agent B" cannot have it. The interests of agentsare thus, generally, clearly separated.However with the evolving shift in the economy towards an informational materiality, in which value is based uponthe informational significance, or the narratives surrounding the products, the clear-cut subjective separation is nolonger obvious. Hardt and Negri see the open source approaches as examples of new ways of co-operation thatillustrate how economic value is not founded upon exclusive possession, but rather upon collective potentialities.Informational materiality is characterized by gaining value only through being shared. Hardt and Negri thus suggestthat the commons become the focal point of analyses of public relations. The point being that with this shift itbecomes possible to analyse how the very distinctions between the private and public are evolving.[15]

References[1] , p. 86, See also: G. T. Goodnight (1982). "The Personal, Technical, and Public Spheres of Argument". Journal of the American Forensics

Association. 18:214-227.[2][2] Also published in 1992 in[3][3] Habermas 1989, p.30[4][4] Habermas 1989, p.31[5][5] Habermas 1989, p.27[6][6] Habermas 1989, 27[7][7] Habermas 1989:xi[8][8] Habermas 1989, pp.36[9][9] Berdal 2004, p. 24[10][10] Benhabib 1992 pp. 89-90[11][11] Benhabib 1992, p. 89[12] . Warner, Michael. 2002. Publics and Counterpublics. New York: Zone Books.[13][13] , pp. 46, 64[14][14] Sparks (2001), p 75[15][15] Hardt, Michael; Antonio Negri (2009), pp. vii-xiv

Public sphere 10

External links• Public Sphere Guide (http:/ / publicsphere. ssrc. org/ guide/ ), a research and teaching guide, and resource for the

renewal of the Public Sphere• Transformations of the Public Sphere (http:/ / publicsphere. ssrc. org/ ) Essay Forum• Jürgen Habermas, "The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article," New German Critique 3 (1974) (http:/ / www.

mtsu. edu/ ~dryfe/ SyllabusMaterials/ Classreadings/ habermas. pdf)Wikipedia:Link rot• Spark summary of Habermas' public sphere book (http:/ / www. sparknotes. com/ philosophy/ public/ )

Article Sources and Contributors 11

Article Sources and ContributorsPublic sphere Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?oldid=620198490 Contributors: ALpHatheONE, Al Lemos, AlexR, Alitehrani, Andy Smith, Anniika, BMF81, Ballofstring,Battocchia, Boeder, Bogey97, Burke4895, Byelf2007, Cayt723, Cliftoncoxellis, Cntras, Coffeepusher, CommonsDelinker, Cícero, Demoniccathandler, Ejvindh, ElKevbo, Em79, Ericbateson,Erik Carson, Everyme, Fences and windows, Fossa, Fuchschristian, Gavb, Gimmetrow, Grumpyyoungman01, JBirken, Jahsonic, Jamileh100, Jelsova, Jinshuang, Jjshapiro, Jrk3150, Jummai,JustAGal, KarlHeg, KathrynLybarger, Ken Gallager, Keurkoon, Lee M, LilHelpa, Lilorangecup, Lindsayt930, Lotje, Magioladitis, Manthone, Maurice Carbonaro, Mbc409, Mcdonnkm, Meclee,Michael Allan, Mike Rosoft, Mild Bill Hiccup, Mirv, Mjdieter, Mmdye, MrOllie, Nihil novi, Noodleki, Oatmeal batman, Omnipaedista, Ot, Owen, P. S. Burton, Palthrow, Patrick, Pethr, PhilSandifer, Pinar, Piotrus, Pochsad, Practice, Pragmatismo, PrivateEye1, Publicy, Quintus314, RedWolf, Rexroad2, Rjwilmsi, Rmashhadi, Ryanx7, Saddhiyama, Sae1962, Scarpy, Schreiberella,Sinn, Skyfaller, Smilo Don, Sonicyouth86, Staeiou, Stefanomione, SummerWithMorons, Sumtin fishy, Svlberg, Template namespace initialisation script, Tgeairn, The Vintage Feminist,Tomsega, Tomwsulcer, Tony Fox, Trumpkinius, Vetenskapsmannen, Wikid77, Wikielwikingo, Woohookitty, Yccara, YorkU Agent99, Zhao8910, Zzuuzz, ΙωάννηςΚαραμήτρος, 114 ,مانيanonymous edits

Image Sources, Licenses and ContributorsFile:Kahvihuone.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Kahvihuone.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: User:InfrogmationFile:Parlement-Paris-Charles7.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Parlement-Paris-Charles7.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: AnRo0002, Daigaz, Garitan,Louis le Grand, Mel22File:Edenton-North-Carolina-women-Tea-boycott-1775.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Edenton-North-Carolina-women-Tea-boycott-1775.jpg License: PublicDomain Contributors: Charles Matthews, Churchh, Ecummenic, Jacklee, Jarble, Ji-Elle, John Vandenberg, Lotje, Mu, Ranveig, TwoWingsFile:StopEssaisManif.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:StopEssaisManif.jpg License: Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 2.0 Contributors: Yann ForgetFile:Sblondon-elecgraffiti05.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Sblondon-elecgraffiti05.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Cathy Richards, Denniss,MichaelMaggs, MykReeve, Nard the Bard, Pomeranian

LicenseCreative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0//creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/