Psoriatic arthropathy

-

Upload

arnab-ghosh -

Category

Health & Medicine

-

view

20 -

download

0

Transcript of Psoriatic arthropathy

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n e

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017 957

Review Article

Psoriasis is a common skin disease that is associated with multi-ple coexisting conditions. The most prevalent coexisting condition, psoriatic arthritis, develops in up to 30% of patients with psoriasis and is character-

ized by diverse clinical features, often resulting in delayed diagnosis and treat-ment. Initial reports emphasized a benign course in most patients, but it is now recognized that psoriatic arthritis often leads to impaired function and a reduced quality of life.1,2 Fortunately, improved knowledge about disease mechanisms has catalyzed rapid development of effective targeted therapies for this disease. To help the clinician recognize and appropriately treat psoriatic arthritis, this review focuses on epidemiologic and clinical features, pathophysiological characteristics, and treatment.

Psor i atic A rthr i tis a nd Spondy l oa rthr i tis

The classic description of the clinical features of psoriatic arthritis was published in 1973; however, skeletal remains unearthed in 1983 from a Byzantine monastery in the Judean Desert, dating to the fifth century a.d., showed visual and radiographic features consistent with psoriatic bone and joint disease.3,4 Psoriatic arthritis shares genetic and clinical features with other forms of spondyloarthritis and is grouped with these disorders.5,6 Diagnostic criteria for psoriatic arthritis have not been validated, but the Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR criteria), published in 2006, define psoriatic arthritis for the purpose of enrolling patients in clinical trials and provide guidance to clinicians (Table 1).7

Epidemiol o gy a nd Dise a se Bur den

The prevalence of psoriatic arthritis ranges from 6 to 25 cases per 10,000 people in the United States, depending on the case definition.8 Psoriatic arthritis was thought to be rare, but recent studies based on CASPAR criteria indicate that it occurs in up to 30% of patients with psoriasis.9,10 These data suggest that the prevalence of psoriatic arthritis is between 30 and 100 cases per 10,000, assuming that 3% of the U.S. population has psoriasis. About 15% of patients with psoriasis who are followed by dermatologists have undiagnosed psoriatic arthritis.9 The an-nual incidence of psoriatic arthritis was reported to be 2 to 3% in a prospective study of patients with psoriasis.11 The manifestation of psoriasis precedes that of arthritis by 10 years on average, although in 15% of cases, arthritis and psoriasis occur simultaneously or psoriatic arthritis precedes the skin disease. Psoriatic arthritis is uncommon in Asians and blacks, and the male-to-female ratio is 1:1.

Psoriatic arthritis can begin during childhood. There are two clinical subtypes; they are not mutually exclusive. Oligoarticular psoriatic arthritis (characterized by four or fewer affected joints) has a peak onset at 1 to 2 years of age and occurs

From the Allergy, Immunology, and Rheu-matology Division, University of Roches-ter Medical School, Rochester, NY (C.T.R.); the Pediatric Translational Research Branch, National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, Bethesda, MD (R.A.C.); and the Univer-sity Health Network (UHN) Krembil Re-search Institute, the Psoriatic Arthritis Program, and the Centre for Prognosis Studies in the Rheumatic Diseases — all at Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto (D.D.G.). Address reprint requests to Dr. Ritchlin at the Allergy, Immunology, and Rheumatology Division, University of Rochester Medical School, 601 Elmwood Ave., Box 695, Rochester, NY 14642, or at christopher_ritchlin@ urmc . rochester . edu.

N Engl J Med 2017;376:957-70.DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1505557Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society.

Dan L. Longo, M.D., Editor

Psoriatic ArthritisChristopher T. Ritchlin, M.D., M.P.H., Robert A. Colbert, M.D., Ph.D.,

and Dafna D. Gladman, M.D.

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017958

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n e

predominantly in girls. This form is associated with a positive test for antinuclear antibodies and chronic uveitis and is often characterized by dactylitis (diffuse swelling of a toe or finger).12 The second subtype (characterized by any num-ber of affected joints) develops between 6 years and 12 years of age and is associated with HLA-B27; antinuclear antibodies are usually absent. This form has a 1:1 sex ratio, with dactylitis, enthesitis (inflammation at tendon, ligament, or joint-capsule insertions), nail pitting, onycholysis, and axial involvement occurring more frequently than in the first subtype. According to the Inter-national League of Associations for Rheumatol-ogy classification system, psoriatic arthritis is distinct from other forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis and is defined by the coexistence of ar-thritis and psoriasis in the absence of features of other forms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis.13 A child with arthritis who does not have psoria-sis but who has two or more features of psori-atic arthritis, such as dactylitis, nail pitting,

onycholysis, or a family history of psoriasis (first-degree relative), meets the criteria for pso-riatic arthritis.

The psychological and functional burdens of the disease are considerable and similar in mag-nitude to those of axial spondyloarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.14,15 One study showed that psoriatic arthritis was significantly associated with rates of absenteeism from work and pro-ductivity at work and that these findings were correlated with measures of disease activity and physical functioning.16 Mortality rates among patients with psoriatic arthritis have fallen and are similar to those in the general population, although some centers report an increase in mortality related to cardiovascular disease.17,18

Clinic a l M a nifes tations

Moll and Wright described five clinical subtypes of psoriatic arthritis that highlight the heteroge-neity of the disease (Fig. 1).3 The oligoarticular

Figure 1 (facing page). Clinical Features of Psoriatic Arthritis.

Panel A shows the distal subtype of psoriatic arthritis, with adjacent onycholysis. Panel B shows the oligoarticular subtype. Panel C shows the polyarticular subtype. Panel D show arthritis mutilans, with telescoping of digits and asymmetric and differential involvement of adjacent digits. Panel E shows the spondylitis subtype. Panel F shows enthesitis of the Achilles’ tendon (arrow). Panel G shows dactylitis of the big toes.

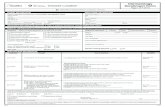

Criterion Explanation Points

Evidence of psoriasis

Current psoriasis Current psoriatic skin or scalp disease as judged by a dermatologist or rheu-matologist

2

Personal history of psoriasis History of psoriasis according to the patient or a family doctor, dermatologist, or rheumatologist

1

Family history of psoriasis History of psoriasis in a first- or second-degree relative according to the patient 1

Psoriatic nail dystrophy Typical psoriatic nail dystrophy (e.g., onycholysis, pitting, or hyperkeratosis) according to observation during current physical examination

1

Negative test for rheumatoid factor Based on reference range at local laboratory; any testing method except latex, with preference for ELISA or nephelometry

1

Dactylitis

Current dactylitis Swelling of an entire digit according to observation on current physical exam-ination

1

History of dactylitis According to a rheumatologist 1

Radiographic evidence of juxtaarticular new bone formation

Ill-defined ossification near joint margins (excluding osteophyte formation) on plain radiographs of hand or foot

1

* Psoriatic arthritis is considered to be present in patients with inflammatory musculoskeletal disease (disease involving the joint, spine, or enthe-sis) whose score on the five criteria listed in the table totals at least three points; the “evidence of psoriasis” criterion can account for either one point or two points. The criteria have a specificity of 98.7% and a sensitivity of 91.4%. ELISA denotes enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Table 1. Classification Criteria for Psoriatic Arthritis (CASPAR).*

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017 959

Psoriatic Arthritis

A B

DC

FE

G

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017960

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n e

subtype affects four or fewer joints and typically occurs in an asymmetric distribution. The poly-articular subtype affects five or more joints; the involvement may be symmetric and resemble rheumatoid arthritis. The distal subtype, which affects distal interphalangeal joints of the hands, feet, or both, usually occurs with other subtypes, occurring alone in only 5% of patients. Arthritis mutilans, a deforming and destructive subtype of arthritis that involves marked bone resorption or osteolysis, is characterized by telescoping and flail digits. The axial or spondyloarthritis sub-type primarily involves the spine and sacroiliac joints. These patterns may change over time.19

Enthesitis is observed in 30 to 50% of pa-tients and most commonly involves the plantar fascia and Achilles’ tendon, but it may cause pain around the patella, iliac crest, epicondyles, and supraspinatus insertions.20 Dactylitis is re-ported in 40 to 50% of patients and is most prevalent in the third and fourth toes but may also involve the fingers. Dactylitis can be either acute (swelling, redness of the skin, and pain) or chronic (swelling without inflammation).21 Dacty-litis is often associated with severe disease that is characterized by polyarthritis, bone erosion, and new bone formation.22

The diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis is based on the recognition of clinical and imaging fea-tures, since there are no specific biomarkers (Fig. 1).23 Involvement of at least five domains is possible; these include psoriasis, peripheral joint disease, axial disease, enthesitis, and dactylitis. Patients should be carefully assessed for these domains, with the understanding that various domain combinations may be present in an indi-

vidual patient.24 The personal history and family history of psoriasis are often positive. Inflam-matory arthritis, enthesitis, dactylitis, and joint distribution provide important clues, as do extra-articular features such as inflammatory bowel disease and uveitis. It is important to look for psoriatic skin lesions, particularly in the groin, umbilical area, hairline, ears, and natal (i.e., intergluteal) cleft. Nail lesions, including pits and onycholysis, as well as the presence of spinal disease, support the diagnosis.

It is important that dermatologists and pri-mary care physicians caring for patients with psoriasis identify psoriatic arthritis early. Patients with psoriasis should be questioned about joint pain, morning stiffness, and evidence of “sau-sage” digits (dactylitis). Screening questionnaires for dermatology or primary care offices have high sensitivity for the presence of musculoskel-etal disease but moderate specificity for psoriatic arthritis.25

Differ en ti a l Di agnosis

It is necessary to differentiate psoriatic arthritis from rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, gout, pseudogout, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other forms of spondyloarthritis (Tables 2 and 3). Rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by proxi-mal, symmetric involvement of the joints of the hands and feet, with sparing of the distal inter-phalangeal joints, whereas in more than 50% of patients with psoriatic arthritis, the distal joints are affected; the involvement tends to be charac-terized by a “ray” distribution, with all the joints of the same digit involved and other digits spared.

Variable Psoriatic Arthritis Rheumatoid Arthritis Gout Osteoarthritis

Joint distribution at onset Asymmetric Symmetric Asymmetric Asymmetric

No. of affected joints Oligoarticular Polyarticular Monoarticular or oligo-articular

Monoarticular or oligo-articular

Sites of hands or feet involved Distal Proximal Distal Distal

Areas involved All joints of a digit Same joint across digits Usually monoarticular Same joints across digits

Tenderness (kg on a dolorimeter) 7 4 NA NA

Purplish discoloration Yes No Yes No

Spinal involvement Common Uncommon Absent Noninflammatory

Sacroiliitis Common Absent Absent Absent

* NA denotes not assessed.

Table 2. Differentiation among Various Forms of Arthritis.*

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017 961

Psoriatic Arthritis

This is noticeable both clinically and radio-graphically. At its onset, psoriatic arthritis tends to be oligoarticular and less symmetric than rheumatoid arthritis, although with time, psori-atic arthritis may become polyarticular and sym-metric.26,27 The affected joints are less tender in psoriatic arthritis than in rheumatoid arthritis and may have a purplish discoloration.28 Spinal involvement (sacroiliac joints or the lumbar, thoracic, or cervical spine) occurs in more than 40% of patients with psoriatic arthritis but is uncommon in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Psoriatic monoarthritis, particularly involving the toes, or dactylitis may be misdiagnosed as gout or pseudogout. The uric acid level may be elevated in patients with psoriatic arthritis, as well as in those with gout, making the differential diagnosis difficult, particularly if crystal analysis of joint fluid is negative or cannot be performed. The distal-joint involvement that is characteristic of psoriatic arthritis is also observed in osteoar-thritis. In psoriatic arthritis, palpation of distal joints reveals soft swelling due to inflammation, whereas in osteoarthritis, swelling arises from a bony osteophyte and is solid. Moreover, involve-ment of distal interphalangeal joints and nail disease (pitting or onycholysis) occur frequently in psoriatic arthritis but not in osteoarthritis.

Ankylosing spondylitis typically begins late in the second decade of life or early in the third decade, whereas psoriatic spondyloarthritis is more likely to develop in the fourth decade of life. Psoriatic spondyloarthritis may be less severe than ankylosing spondylitis, with less pain and

infrequent sacroiliac-joint ankylosis; an asymmet-ric distribution of syndesmophytes (bony growths originating inside a ligament of the spine) is more common in cases of psoriatic arthritis.29 It may be difficult to distinguish between psori-atic arthritis and reactive arthritis. Both condi-tions may be associated with joint and skin le-sions, and the skin lesions can be difficult to ascribe pathologically to one condition or the other. The psoriasiform lesions of subacute cuta-neous lupus can mimic psoriasis vulgaris, but patients with cutaneous lupus do not have the other defining features of psoriatic arthritis.

L a bor at or y a nd Im aging Findings

Tests for rheumatoid factor, anti–cyclic citrulli-nated peptide antibodies, or both are negative in 95% of patients with psoriatic arthritis. When a test result is positive, clinical and imaging fea-tures must be used to differentiate psoriatic from rheumatoid arthritis. Approximately 25% of pa-tients with psoriatic arthritis are HLA-B27–posi-tive. Increases in the serum C-reactive protein level, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or both are seen in only 40% of patients.

The occurrence of bone and cartilage destruc-tion with pathologic new bone formation is one of the most distinctive aspects of psoriatic ar-thritis (Fig. 2). Radiographs of peripheral joints often show evidence of bone loss with eccentric erosions and joint-space narrowing, as well as new bone formation characterized by periostitis,

Feature Psoriatic ArthritisAnkylosing Spondylitis Reactive Arthritis

IBD-Associated Arthritis

Age at onset (yr) 36 20 30 30

Male:female ratio 1:1 3:1 3:1 2:1

Peripheral joints affected (% of cases)

96 30 90 30

Axial joints affected (% of cases) 50 100 100 30

Dactylitis Common Absent Uncommon Absent

Enthesitis Common Common Uncommon Uncommon

Psoriasis (% of cases) 100 10 10 10

Nail lesions 87% of cases Uncommon Uncommon Uncommon

HLA-B*27 (% of cases) 40–50 90 70 30

* IBD denotes inflammatory bowel disease.

Table 3. Clinical Features of Various Forms of Spondyloarthritis.*

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017962

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n e

bony ankylosis, and enthesophytes (abnormal bony projections at the attachment of a tendon or ligament).30 In the axial skeleton, changes associated with psoriatic arthritis include uni-lateral sacroiliitis and bulky paramarginal and vertical syndesmophytes. (In contrast, in anky-

losing spondylitis, sacroiliac involvement is typi-cally bilateral and paramarginal syndesmophytes are uncommon.) Magnetic resonance imaging studies may reveal focal erosions, synovitis, and bone marrow edema in the peripheral and axial structures, particularly at entheses. Bone marrow

Figure 2. Radiographic Features of Psoriatic Arthritis.

Panel A show arthritis mutilans, with pencil-in-cup deformities (arrow) and marked bone resorption (osteolysis) in phalanges of the right hand. The hand radiograph in Panel B shows joint resorption, ankylosis, and erosion in a single ray. Panel C shows enthesophytes at the plantar fascia and Achilles’ tendon insertions. Panel D shows syndesmophytes involving the cervical spine, with ankylosis of facet joints (arrow). Panel E shows bilateral grade 3 sacroiliitis. Panel F shows a paramarginal syndesmophyte bridging the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae. Panel G shows bone marrow edema in the second and third lumbar vertebrae in a patient with severe psoriasis and a new onset of back pain. The high-frequency (15-MHz) gray-scale ultrasound image in Panel H shows synovitis of the metacarpophalangeal joint. Dis-tention of the joint capsule is evident (arrows). The confluent red signals (box in the lower part of the image) with power Doppler ultra-sonography indicate synovial hyperemia. MC denotes metacarpal head, and PP proximal phalanx. The high-frequency (15-MHz) ultrasound image in Panel I shows enthesitis. The confluent red signals with power Doppler ultrasonography represent hyperemia at the tendon near its insertion into the calcaneus. Normally, the tendon is poorly vascularized.

A

D E F

H

MC PP

Achilles’ tendon

Joint resorption

Calcaneus

MC PP

I

G

B C

Ankylosis

Erosion

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017 963

Psoriatic Arthritis

edema is best observed on T2-weighted, fat-sup-pressed, short-tau inversion recovery (STIR) se-quences. Power Doppler ultrasound imaging can be used to identify synovitis, enhanced blood flow, tenosynovitis, enthesophytes, and early ero-sive disease.31

Ou t comes

Psoriatic arthritis is a severe form of arthritis in which deformities and joint damage develop in a large number of patients.1,2 Bone erosions are ob-served in 47% of patients within the first 2 years, despite the use of traditional disease-modifying medications in more than half the patients.32 Furthermore, severe disease at presentation and an elevated C-reactive protein level are risk fac-tors for radiographic progression.33,34 Spontane-ous remission of psoriatic arthritis is extremely rare. In an observational trial involving patients treated with anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, the rate of partial remission was 23%.35 However, relapse rates are high when biologic agents are discontinued.36,37

Coe x is ting Condi tions

Psoriatic arthritis is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, the metabolic syn-drome, fatty liver, and an increased risk of car-diovascular events.38 Uveitis affecting anterior and posterior poles of the eye occurs in 8% of patients with psoriatic arthritis; the prevalence of Crohn’s disease and subclinical colitis is increased in these patients.

C auses a nd Pathoph ysiol o gic a l Fe at ur es

Psoriatic arthritis is a highly heritable polygenic disease. The recurrence risk ratio (defined as the risk of disease manifestation in siblings vs. the risk in the general population) is greater than 27, which is substantially higher than the recur-rence risk ratio for psoriasis or rheumatoid arthri-tis.39 In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, which is associated with class II major histocompati-bility complex (MHC) alleles, psoriasis and pso-riatic arthritis are associated with class I MHC alleles. Most notably, HLA-C*06 is a major risk factor for psoriasis but not for psoriatic arthritis. In psoriatic arthritis, frequencies of HLA-B*08,

B*27, B*38, and B*39 have been observed, with specific subtypes of those alleles linked to sub-phenotypes, including symmetric or asymmetric axial disease, enthesitis, dactylitis, and synovitis.40 Genomewide association scans have shown that certain polymorphisms in the gene encoding interleukin-23 receptor (IL23R), along with vari-ants in nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) gene expression (TNIP1) and signaling (TNFAIP3), and TNF ex-pression are associated with psoriatic arthritis. A polymorphism at chromosome 5q31, rs715285, maps to an intergenic region flanked by the genes CSF2 and P4HA2.41 Association studies have identified additional risk alleles in patients with psoriasis and in those with psoriatic arthritis, including interleukin-12A (IL12A), interleukin-12B (IL12B), IL23R, and genes that regulate NF-κB.42,43

There are several environmental risk factors for psoriatic arthritis. These include obesity; se-vere psoriasis; scalp, genital, and inverse (or inter-triginous) psoriasis; nail disease; and trauma or deep lesions at sites of trauma (Koebner’s phe-nomenon).44,45

It has been shown consistently that T cells are important in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. A central role for CD8+ T cells in disease patho-genesis is supported by the association with HLA class I alleles, oligoclonal CD8+ T-cell expan-sion, and the association of psoriatic arthritis with human immunodeficiency virus disease.46 Type 17 cells, which include CD4+ type 17 helper T (Th17) cells, and type 3 innate lympho-cytes (cells that produce interleukin-17A and inter-leukin-22), in addition to CD4+CD8+ lympho-cytes, are increased in psoriatic synovial fluid as compared with rheumatoid synovial fluid.47,48

Recent studies highlight the importance of the interleukin-23–interleukin-17 and TNF path-ways in the pathogenesis of psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthropathies.47-49 In psoriasis, expression of interferon-α by plasma-cytoid dendritic cells activates dermal dendritic cells that trigger the differentiation of type 1 helper T (Th1) cells and Th17 cells in draining lymph nodes. These lymphocytes return to the dermis and orchestrate a complex immune-mediated inflammatory response (Fig. 3).50 Addi-tional genetic factors, environmental factors, or both are likely to trigger inflammatory arthritis.

In an alternative disease model, the enthesis is proposed to be the initial site of musculoskel-etal disease.51 In support of this view, enthesitis,

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017964

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n e

Figure 3. Pathogenic Pathways in Psoriatic Arthritis.

The events that potentially link inflammation in the psoriatic skin, bone marrow, and gut with enthesitis, synovitis, and altered bone phenotypes are shown. The interaction between genetic and environmental factors triggers an in-flammatory response at multiple sites. In the plaque that forms in the skin, DNA released by stressed keratinocytes binds to the antibacterial peptide LL-37 and stimulates interferon-α (IFN-α) release by plasmacytoid dendritic cells, activating dermal dendritic cells, which migrate to draining lymph nodes and trigger differentiation of type 1 helper T (Th1) and type 17 helper T (Th17) cells. The Th1 and Th17 cells home to the dermis, where they release interleukin-12, 17, and 22 (IL-12, IL-17, and IL-22, respectively) and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), along with a range of chemo-kines and other cytokines. Additional IL-17–secreting (i.e., type 17) cells in the dermis include innate lymphoid cells and CD8+ T cells. The cytokine release in the dermis promotes keratinocyte proliferation; these keratinocytes in turn release cytokines that act in a paracrine fashion on cells in the dermis. Expansion of Th1 and Th17 cells, along with other type 17 cells and osteoclast precursors (OCPs), may also take place in the bone marrow. In the gut, microbial dysbiosis may initiate inflammation in the ileocolon and trigger IL-23 release and type 17 cells. In the enthesis, IL-23 release in response to biomechanical stress or trauma at the tendon-insertion site activates type 17 cells and other cytokines, including IL-22 and TNF, with resultant inflammation, bone erosion, and pathologic bone formation. Mesenchymal cells differentiate into osteoblasts in response to IL-22 and other signaling pathways, forming enthe-sophytes in peripheral entheses and joints and syndesmophytes in the spine. Type 17 cells, OCPs, and dendritic cells reach the joint from adjacent entheses or the bloodstream. Increased expression of the receptor activator of NF-κB (RANK) ligand (RANKL) by synoviocytes in the lining, coupled with increased levels of TNF, IL-17, and RANKL expressed by infiltrating cells, drives the differentiation of OCPs into osteoclasts, with synovitis and bone resorption. Pathologic bone formation proceeds as outlined above in the enthesis.

Biomechanical stressor trauma

Enthesis

Joints

Achilles’tendon

Tendon

Muscle

IL-23IL-22 and other factors

Pathologic boneformation

IL-22TNFType 17

Osteoblast

Osteoclast

CD68+

Osteoprogenitor

MacrophageDendritic cell

Activatedlymphocyte

IL-23

IL-17, TNF

TNF

IL-17TNF-αRANKL

RANK+

Skin

Gut

LL-37IL-12IL-17IL-22

TNF-αChemokines

Cytokines

↑OCP↑Th1

↑Type 17

IFN-αIL-23

Bone marrow

Microbial dysbiosis

↑IL-23

Synoviocyte

OCP

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017 965

Psoriatic Arthritis

synovitis, and altered bone remodeling were ob-served in a murine model in which the adminis-tration of interleukin-23 led to an enthesis-centered inflammatory arthritis that was similar to spon-dyloarthritis, with bone erosion and new bone formation.52 Inflammation was linked to a novel population of innate lymphocytes residing in the entheses that produce interleukin-17.53 Inflam-mation and bone erosion were mediated by TNF and interleukin-17. Another murine model has shown that overexpression of interleukin-23 can also lead to an inflammatory, erosive arthritis phenotype, which may reflect differences in the dose or timing of interleukin-23 delivery, microbial heterogeneity, or differences in mouse strains.54 Several other murine models of spondyloarthri-tis with enthesitis, psoriasiform skin lesions, and arthritis have subsequently been reported, all of which have been linked to interleukin-23.55,56 Microbial infections are known triggers of cer-tain forms of spondyloarthritis, and reports of an elevated frequency of subclinical gut inflam-mation and dysbiosis (decreased microbial diver-sity) in patients with psoriatic arthritis, as com-pared with healthy controls, support a potential gut–joint axis in the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis.57,58

The synovial tissues in patients with psoriatic arthritis bear a closer resemblance to the synovi-um in patients with spondyloarthritis than to the synovium in those with rheumatoid arthritis, with more vascularity, a greater influx of neutro-phils, and the absence of antibodies to citrulli-nated peptides.59 As compared with rheumatoid synovial tissue, psoriatic synovial tissue has a lower number of infiltrating T lymphocytes and plasma cells, but the expression of TNF and inter-leukin-1, 6, and 18 is similar in the two diseases.60

Bone involvement in psoriatic arthritis is het-erogeneous both among patients and within the individual patient. Spinal involvement may be similar to that in ankylosing spondylitis, and de-structive peripheral-joint features may resemble those of rheumatoid arthritis. Pathologic new bone formation, including joint ankylosis and syndesmophyte formation, typically occurs at sites of soft-tissue inflammation surrounding the enthesis.61 In psoriatic synovium, marked up-regulation of the receptor activator of NF-κB

(RANK) ligand (RANKL) and low expression of its antagonist, osteoprotegerin, have been detect-ed in the adjacent synovial lining.62 The RANKL cytokine binds to RANK on the surface of osteo-clast precursors derived from circulating CD14+ monocytes. This ligand–receptor interaction trig-gers proliferation of the osteoclast precursors and their differentiation into multinucleated osteo-clasts, which resorb bone. Moreover, a study has shown that osteoclast precursors derived from circulating CD14+ monocytes are markedly ele-vated in the peripheral blood of patients with psoriatic arthritis, as compared with healthy con-trols, and that treatment with anti-TNF agents significantly reduces the level of circulating pre-cursors, a finding that supports a central effect of TNF in the generation of precursor forma-tion.63 Molecules and pathways associated with pathologic bone formation include interleukin-17A, bone morphogenetic protein, transforming growth factor β, prostaglandin E2, and mole-cules in the Wnt signaling pathway, although their roles in psoriatic arthritis are unknown.64,65

Ou t come Me a sur es for Psor i atic A rthr i tis

It is important to evaluate each of the musculo-skeletal domains, along with the severity and extent of psoriasis, in patients with suspected psoriatic arthritis. Assessments should include examination of 68 joints for tenderness and 66 joints for swelling; spinal range of motion and pain; enthesitis, assessed with the use of one of the enthesitis indexes, such as the Leeds Enthesi-tis Index (assessment of six entheses) or the Spondyloarthritis Research Consortium Canada (SPARCC) Enthesitis Index; and dactylitis, as-sessed with the use of either a dactylitis digit count or the Leeds Dactylitis Index.66 Psoriasis should be assessed on the basis of the involved body-surface area or the Psoriasis Area and Sever-ity Index (PASI),67 and nails should be examined for onycholysis or pitting. In clinical trials, out-come measures adapted from instruments used to assess outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis in-clude the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) 20, ACR 50, and ACR 70 response rates (indicating reductions in the number of both

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017966

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n e

tender and swollen joints of at least 20%, 50%, and 70%, respectively, with improvement in at least three of the following five additional mea-sures: patient and physician global assessments, pain, disability, and an acute-phase reactant) and the Disease Activity Score (DAS), which is used to assess peripheral arthritis. A number of com-posite measures have recently been developed specifically for psoriatic arthritis, including the Psoriatic Arthritis Disease Activity Score (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org), the Composite Psoriatic Disease Activity Index (Ta-ble S2 in the Supplementary Appendix), and the GRACE (Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis [GRAPPA] Com-posite Exercise) instrument (Table S3 in the Sup-plementary Appendix).66 In addition, minimal disease activity, defined by clinically significant improvement in five of seven response measures or domains is a validated instrument for assess-ing treatment response in psoriatic arthritis (Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).68

Ther a py

The treatment of psoriatic arthritis is compli-cated by heterogeneity in the presentation of the disease and its course, often resulting in a de-layed diagnosis. To address this complexity, it is important to identify disease activity in each of the domains. The domain with the highest level of activity drives the treatment choices, and it is very common for a patient to have involvement of several domains.

Evidence-based treatment recommendations have recently been published.69,70 Table 4 summa-rizes current therapies and treatment responses. For patients with a mild oligoarticular presenta-tion, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications combined with intraarticular injections, when appropriate, can be effective.71 For patients with more severe symptoms, disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are typically pre-scribed as an initial treatment. Unfortunately, data from randomized clinical trials of tradi-tional DMARDs for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis are limited. A trial of methotrexate as compared with placebo did not show a signifi-cant treatment effect, although the study may have been underpowered and the dose of oral methotrexate was lower than that typically pre-

scribed in practice.72 Leflunomide is effective for peripheral arthritis but not psoriasis.73 Compel-ling data show that anti-TNF agents (adalimu-mab, certolizumab, etanercept, and golimumab) suppress skin and joint inflammation and retard radiographic progression.74 These agents are ef-fective for enthesitis, dactylitis, and also for axial disease on the basis of data from trials involving patients with ankylosing spondylitis.6

Use of the anti-p40 antibody ustekinumab, directed against the shared subunit of interleu-kin-12 and interleukin-23, is effective for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, although results in the skin are more impressive than those in the joints.75 Secukinumab and brodalumab, agents that block interleukin-17 and the interleukin-17 receptor, respectively, are effective in psoriatic arthritis, with demonstrated improvement in both skin and musculoskeletal features. However, trials of brodalumab were suspended because of safety concerns that were not observed with secukinumab.76,77 Ixekizumab, another interleukin-17 blocker, showed efficacy in phase 3 trials involving patients with psoriatic arthritis and was recently approved for the treat-ment of psoriasis.78 Phosphodiesterase 4 inhibi-tion with apremilast has been approved for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Skin responses to treatment with apremilast are similar to those with methotrexate, but joint re-sponses are somewhat lower than those observed with biologic agents.79 Finally, abatacept, a T-cell activation blocker that targets CD80 and CD86 costimulatory molecules, is moderately effective in psoriatic arthritis for joint involvement but not for skin disease.80 Anti-TNF agents, the interleu-kin-12–interleukin-23 antagonist ustekinumab, and the interleukin-17 monoclonal antibodies secukinumab and ixekizumab inhibit radiograph-ic progression in patients with psoriatic arthritis who have peripheral-joint involvement. Apremi-last, brodalumab, and secukinumab are not ef-fective for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, whereas rituximab and abatacept are highly ef-fective. Collectively, these contrasting findings from clinical trials suggest that rheumatoid ar-thritis and psoriatic arthritis have different under-lying mechanisms. In contrast, the pathophysio-logical pathways that underlie psoriatic skin and joint disease overlap considerably. Nevertheless, cyclosporine and methotrexate are more effec-tive in psoriasis than is leflunomide in psoriatic

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017 967

Psoriatic Arthritis

Tabl

e 4.

Eff

icac

y an

d Si

de E

ffec

ts o

f Dru

gs fo

r th

e Tr

eatm

ent o

f Pso

riat

ic A

rthr

itis.

Dru

g (M

ode

of A

dmin

istr

atio

n)D

ose

Acc

ordi

ng t

o Si

teSi

gns

and

Sym

ptom

sSt

ruct

ural

Mod

ifica

tion

of Jo

ints

*C

omm

on S

ide

Effe

cts

Join

tsSk

inJo

ints

Skin

NSA

IDs

Mild

res

pons

e—

Not

ass

esse

d

Nap

roxe

n (o

ral)

750–

1000

mg/

day

Not

app

licab

leG

astr

oint

estin

al e

ffect

s

Dic

lofe

nac

(ora

l)10

0–15

0 m

g/da

yN

ot a

pplic

able

Car

diac

effe

cts

Indo

met

haci

n (o

ral)

100/

150

mg/

day

Not

app

licab

leR

enal

effe

cts

DM

AR

Ds

Met

hotr

exat

e (o

ral o

r SC

)15

–25

mg/

wk

15–2

5 m

g/w

kM

ild r

espo

nse

Mod

erat

e re

spon

seN

ot a

sses

sed

Hai

r lo

ss, n

ause

a,

hepa

tic e

ffect

s

Leflu

nom

ide

(ora

l)20

mg/

day

Not

app

licab

leM

ild r

espo

nse

Mild

res

pons

eN

ot a

sses

sed

Dia

rrhe

a, r

enal

effe

cts,

ha

ir lo

ss

Sulfa

sala

zine

(or

al)

2–3

g/da

yN

ot a

pplic

able

——

Not

ass

esse

dN

eutr

open

ia, d

iarr

hea

Ant

i-TN

F ag

ents

Ada

limum

ab (

SC)

40 m

g ev

ery

2 w

k80

mg

load

ing

dose

, 40

mg

1 w

k la

ter,

then

40

mg

ever

y 2

wk

Ver

y go

od

resp

onse

Mod

erat

e re

spon

seM

oder

ate

resp

onse

Inje

ctio

n-si

te r

eact

ions

, in

fect

ions

Cer

toliz

umab

(SC

)20

0 m

g ev

ery

2 w

k or

400

mg

ever

y 4

wk

Not

app

licab

leV

ery

good

re

spon

seN

ot a

sses

sed

Mod

erat

e re

spon

seIn

ject

ion-

site

rea

ctio

ns,

infe

ctio

ns

Etan

erce

pt (

SC)

50 m

g w

eekl

y50

mg

twic

e/w

kV

ery

good

re

spon

seM

ild r

espo

nse

Mod

erat

e re

spon

seIn

ject

ion-

site

rea

ctio

ns,

infe

ctio

ns

Gol

imum

ab (

SC, i

nfus

ion)

50 m

g m

onth

lyN

ot a

pplic

able

Ver

y go

od

resp

onse

Mild

res

pons

eM

oder

ate

resp

onse

Inje

ctio

n-si

te r

eact

ions

, in

fect

ions

Infli

xim

ab (

infu

sion

)5

mg/

kg o

f bod

y w

eigh

t at 0

, 2,

and

6 w

k, th

en e

very

8 w

k5–

10 m

g/kg

at 0

, 2, a

nd 6

wk,

th

en e

very

8 w

kV

ery

good

re

spon

seEx

celle

nt

resp

onse

Mod

erat

e re

spon

seIn

fusi

on r

eact

ions

, in-

fect

ions

Ant

i–in

terl

euki

n-17

age

nts

Ixek

izum

ab (

SC)

80 m

g ev

ery

2 w

k80

mg

ever

y 2

wk

Ver

y go

od

resp

onse

Exce

llent

re

spon

seM

ild r

espo

nse

Can

dida

infe

ctio

ns

Secu

kinu

mab

(SC

)15

0 m

g w

eekl

y fr

om 0

–4 w

k,

then

mon

thly

300

mg

wee

kly

from

0–4

wk,

then

m

onth

lyV

ery

good

re

spon

seEx

celle

nt

resp

onse

Mild

res

pons

eC

andi

da in

fect

ions

Ant

i–in

terl

euki

n-12

–int

erle

ukin

- 23

age

nt: u

stek

inum

ab

(SC

)

45 m

g/kg

(for

bod

y w

eigh

t of

<100

kg)

or 9

0 m

g/kg

(for

bo

dy w

eigh

t of ≥

100

kg) a

t 0,

4, a

nd 1

2 w

k, th

en e

very

12

wk

45 m

g/kg

(fo

r bod

y w

eigh

t of

<100

kg)

or 9

0 m

g/kg

(fo

r bo

dy w

eigh

t of ≥

100

kg)

at 0

, 4,

and

12

wk,

then

eve

ry 1

2 w

k

Ver

y go

od

resp

onse

Ver

y go

od

resp

onse

Mild

res

pons

eIn

ject

ion-

site

rea

ctio

ns,

infe

ctio

ns

PDE4

inhi

bito

r: a

prem

ilast

(or

al)

30 m

g tw

ice

daily

30 m

g tw

ice

daily

Mod

erat

e re

spon

seM

ild r

espo

nse

Not

ass

esse

dW

eigh

t los

s, d

iarr

hea

* R

ecen

t tria

ls o

f the

se a

gent

s in

volv

ed p

atie

nts

with

litt

le d

isea

se p

rogr

essi

on, r

esul

ting

in a

sm

alle

r ef

fect

on

stru

ctur

al m

odifi

catio

n as

com

pare

d w

ith e

arlie

r tr

ials

, whi

ch in

volv

ed p

atie

nts

with

mor

e se

vere

dis

ease

and

mor

e pr

ogre

ssio

n. F

or d

rugs

that

wer

e no

t ass

esse

d w

ith r

espe

ct to

str

uctu

ral m

odifi

catio

n of

join

ts, o

bser

vatio

nal d

ata

sugg

est n

o re

spon

se. D

ashe

s in

dica

te

that

ther

e w

as n

o ap

prec

iabl

e re

spon

se. D

MA

RD

s de

note

s di

seas

e-m

odify

ing

antir

heum

atic

dru

gs, N

SAID

s no

nste

roid

al a

ntiin

flam

mat

ory

drug

s, P

DE4

pho

spho

dies

tera

se 4

, SC

sub

cuta

ne-

ous

inje

ctio

n, a

nd T

NF

tum

or n

ecro

sis

fact

or.

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017968

T h e n e w e ngl a nd j o u r na l o f m e dic i n e

arthritis. These findings, coupled with the greater response to agents that target the interleukin-12–interleukin-23 axis in the skin as compared with the joints, underscore the divergent mecha-nisms of inflammation in psoriatic plaques and joints.

High-level evidence supporting specific treat-ment algorithms for juvenile psoriatic arthritis is not available. Current recommendations follow the guidelines for juvenile idiopathic arthritis and are based on measures of disease activity, including the number of active joints, inflamma-tory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein level), and global assessments by the physician and patient or parent.81,82 Indica-tors of a poor prognosis, including involvement of certain joints (e.g., the hip, wrist, ankle, joints in the cervical spine, and the sacroiliac joint) and evidence of radiographic damage are also taken into account in considering both initial therapy and escalation.

In addition to pharmacotherapy, patient edu-cation about the importance of controlling in-flammation is critical. Lifestyle modification, including smoking cessation, weight reduction, joint protection, physical activity, and exercise, as well as stress management, is also vital in the management of psoriatic arthritis.

Dr. Ritchlin reports receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries, and Pfizer and grant support from UCB Pharmaceuticals, Amgen, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and AbbVie; Dr. Colbert, being a prin-cipal investigator on a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) between his institute and Eli Lilly; and Dr. Gladman, receiving honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, UCB Phar-maceuticals, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, consulting fees from Eli Lilly, and grant support from Pfizer, AbbVie, Celgene, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and UCB Pharma-ceuticals. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

We thank Ralf Thiele, M.D., for the ultrasound images and Ananta Paine, Ph.D., for editorial review of an earlier version of the manuscript.

References1. Gladman DD, Stafford-Brady F, Chang CH, Lewandowski K, Russell ML. Longi-tudinal study of clinical and radiological progression in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheu-matol 1990; 17: 809-12.2. McHugh NJ, Balachrishnan C, Jones SM. Progression of peripheral joint dis-ease in psoriatic arthritis: a 5-yr prospec-tive study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003; 42: 778-83.3. Moll JM, Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1973; 3: 55-78.4. Zias J, Mitchell P. Psoriatic arthritis in a fifth-century Judean Desert monastery. Am J Phys Anthropol 1996; 101: 491-502.5. Moll JM, Haslock I, Macrae IF, Wright V. Associations between ankylosing spondy-litis, psoriatic arthritis, Reiter’s disease, the intestinal arthropathies, and Behcet’s syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 1974; 53: 343-64.6. Taurog JD, Chhabra A, Colbert RA. Ankylosing spondylitis and axial spondy-loarthritis. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 2563-74.7. Taylor W, Gladman D, Helliwell P, Marchesoni A, Mease P, Mielants H. Clas-sification criteria for psoriatic arthritis: development of new criteria from a large international study. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 2665-73.8. Ogdie A, Weiss P. The epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2015; 41: 545-68.9. Villani AP, Rouzaud M, Sevrain M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed psoriatic ar-thritis among psoriasis patients: system-atic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73: 242-8.

10. Dominguez-Rosado I, Moutinho V Jr, DeMatteo RP, Kingham TP, D’Angelica M, Brennan MF. Outcomes of the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center Interna-tional General Surgical Oncology Fellow-ship. J Am Coll Surg 2016; 222: 961-6.11. Eder L, Haddad A, Rosen CF, et al. The incidence and risk factors for psori-atic arthritis in patients with psoriasis: a prospective cohort study. Arthritis Rheu-matol 2016; 68: 915-23.12. Stoll ML, Zurakowski D, Nigrovic LE, Nichols DP, Sundel RP, Nigrovic PA. Pa-tients with juvenile psoriatic arthritis com-prise two distinct populations. Arthritis Rheum 2006; 54: 3564-72.13. Colbert RA. Classification of juvenile spondyloarthritis: enthesitis-related arthri-tis and beyond. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010; 6: 477-85.14. Michelsen B, Fiane R, Diamantopou-los AP, et al. A comparison of disease bur-den in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic ar-thritis and axial spondyloarthritis. PLoS One 2015; 10(4): e0123582.15. Kotsis K, Voulgari PV, Tsifetaki N, et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms and illness perceptions in psoriatic arthritis and associations with physical health-related quality of life. Arthritis Care Res (Hobo-ken) 2012; 64: 1593-601.16. Tillett W, Shaddick G, Askari A, et al. Factors inf luencing work disability in psoriatic arthritis: first results from a large UK multicentre study. Rheumatol-ogy (Oxford) 2015; 54: 157-62.17. Arumugam R, McHugh NJ. Mortality and causes of death in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl 2012; 89: 32-5.

18. Buckley C, Cavill C, Taylor G, et al. Mortality in psoriatic arthritis — a single-center study from the UK. J Rheumatol 2010; 37: 2141-4.19. Khan M, Schentag C, Gladman DD. Clinical and radiological changes during psoriatic arthritis disease progression. J Rheumatol 2003; 30: 1022-6.20. Kehl AS, Corr M, Weisman MH. Re-view: enthesitis: new insights into patho-genesis, diagnostic modalities, and treat-ment. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68: 312-22.21. Gladman DD, Ziouzina O, Thavane-swaran A, Chandran V. Dactylitis in pso-riatic arthritis: prevalence and response to therapy in the biologic era. J Rheuma-tol 2013; 40: 1357-9.22. Brockbank JE, Stein M, Schentag CT, Gladman DD. Dactylitis in psoriatic ar-thritis: a marker for disease severity? Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: 188-90.23. Anandarajah AP, Ritchlin CT. The di-agnosis and treatment of early psoriatic arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2009; 5: 634-41.24. Kavanaugh AF, Ritchlin CT. System-atic review of treatments for psoriatic ar-thritis: an evidence based approach and basis for treatment guidelines. J Rheuma-tol 2006; 33: 1417-21.25. Coates LC, Aslam T, Al Balushi F, et al. Comparison of three screening tools to detect psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis (CONTEST study). Br J Dermatol 2013; 168: 802-7.26. Gladman DD, Shuckett R, Russell ML, Thorne JC, Schachter RK. Psoriatic arthri-tis (PSA) — an analysis of 220 patients. Q J Med 1987; 62: 127-41.

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017 969

Psoriatic Arthritis

27. Wright V. Psoriatic arthritis: a com-parative radiographic study of rheuma-toid arthritis and arthritis associated with psoriasis. Ann Rheum Dis 1961; 20: 123-32.28. Buskila D, Langevitz P, Gladman DD, Urowitz S, Smythe HA. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis are more tender than those with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheuma-tol 1992; 19: 1115-9.29. Gladman DD, Brubacher B, Buskila D, Langevitz P, Farewell VT. Differences in the expression of spondyloarthropathy: a comparison between ankylosing spon-dylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Clin Invest Med 1993; 16: 1-7.30. Poggenborg RP, Østergaard M, Terslev L. Imaging in psoriatic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2015; 41: 593-613.31. Poggenborg RP, Terslev L, Pedersen SJ, Ostergaard M. Recent advances in imag-ing in psoriatic arthritis. Ther Adv Mus-culoskelet Dis 2011; 3: 43-53.32. Kane D, Stafford L, Bresnihan B, FitzGerald O. A prospective, clinical and radiological study of early psoriatic arthri-tis: an early synovitis clinic experience. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003; 42: 1460-8.33. Gladman DD, Farewell VT, Nadeau C. Clinical indicators of progression in pso-riatic arthritis: multivariate relative risk model. J Rheumatol 1995; 22: 675-9.34. Gladman DD, Mease PJ, Choy EH, Ritchlin CT, Perdok RJ, Sasso EH. Risk factors for radiographic progression in psoriatic arthritis: subanalysis of the ran-domized controlled trial ADEPT. Arthritis Res Ther 2010; 12: R113.35. Lubrano E, Massimo Perrotta F, Manara M, et al. Predictors of loss of re-mission and disease flares in patients with axial spondyloarthritis receiving antitu-mor necrosis factor treatment: a retrospec-tive study. J Rheumatol 2016; 43: 1541-6.36. Araujo EG, Finzel S, Englbrecht M, et al. High incidence of disease recurrence af-ter discontinuation of disease-modifying antirheumatic drug treatment in patients with psoriatic arthritis in remission. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74: 655-60.37. Gladman DD, Hing EN, Schentag CT, Cook RJ. Remission in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2001; 28: 1045-8.38. Ogdie A, Schwartzman S, Husni ME. Recognizing and managing comorbidities in psoriatic arthritis. Curr Opin Rheuma-tol 2015; 27: 118-26.39. Chandran V, Schentag CT, Brockbank JE, et al. Familial aggregation of psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009; 68: 664-7.40. FitzGerald O, Haroon M, Giles JT, Winchester R. Concepts of pathogenesis in psoriatic arthritis: genotype determines clinical phenotype. Arthritis Res Ther 2015; 17: 115.41. Bowes J, Budu-Aggrey A, Huffmeier U, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related susceptibility loci reveals new insights into the genetics of psoriatic arthritis. Nat Commun 2015; 6: 6046.42. Harden JL, Krueger JG, Bowcock AM.

The immunogenetics of psoriasis: a com-prehensive review. J Autoimmun 2015; 64: 66-73.43. Stuart PE, Nair RP, Tsoi LC, et al. Genome-wide association analysis of pso-riatic arthritis and cutaneous psoriasis reveals differences in their genetic archi-tecture. Am J Hum Genet 2015; 97: 816-36.44. Thorarensen SM, Lu N, Ogdie A, Gel-fand JM, Choi HK, Love TJ. Physical trau-ma recorded in primary care is associated with the onset of psoriatic arthritis among patients with psoriasis. Ann Rheum Dis 2016 July 25 (Epub ahead of print).45. Ogdie A, Gelfand JM. Identification of risk factors for psoriatic arthritis: scien-tific opportunity meets clinical need. Arch Dermatol 2010; 146: 785-8.46. Fitzgerald O, Winchester R. Editorial: emerging evidence for critical involvement of the interleukin-17 pathway in both pso-riasis and psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66: 1077-80.47. Leijten EF, van Kempen TS, Boes M, et al. Brief report: enrichment of activated group 3 innate lymphoid cells in psoriatic arthritis synovial fluid. Arthritis Rheuma-tol 2015; 67: 2673-8.48. Menon B, Gullick NJ, Walter GJ, et al. Interleukin-17+CD8+ T cells are enriched in the joints of patients with psoriatic ar-thritis and correlate with disease activity and joint damage progression. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66: 1272-81.49. Yeremenko N, Paramarta JE, Baeten D. The interleukin-23/interleukin-17 immune axis as a promising new target in the treatment of spondyloarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2014; 26: 361-70.50. Lowes MA, Suárez-Fariñas M, Krueger JG. Immunology of psoriasis. Annu Rev Immunol 2014; 32: 227-55.51. McGonagle D, Gibbon W, Emery P. Classification of inflammatory arthritis by enthesitis. Lancet 1998; 352: 1137-40.52. Sherlock JP, Joyce-Shaikh B, Turner SP, et al. IL-23 induces spondyloarthropa-thy by acting on ROR-γt+ CD3+CD4-CD8- entheseal resident T cells. Nat Med 2012; 18: 1069-76.53. Reinhardt A, Yevsa T, Worbs T, et al. Interleukin-23-dependent γ/δ T cells pro-duce interleukin-17 and accumulate in the enthesis, aortic valve, and ciliary body in mice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016; 68: 2476-86.54. Adamopoulos IE, Tessmer M, Chao CC, et al. IL-23 is critical for induction of arthritis, osteoclast formation, and main-tenance of bone mass. J Immunol 2011; 187: 951-9.55. Benham H, Rehaume LM, Hasnain SZ, et al. Interleukin-23 mediates the intesti-nal response to microbial β-1,3-glucan and the development of spondyloarthritis pathology in SKG mice. Arthritis Rheu-matol 2014; 66: 1755-67.56. Ruutu M, Thomas G, Steck R, et al. β-Glucan triggers spondylarthritis and

Crohn’s disease-like ileitis in SKG mice. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64: 2211-22.57. Scarpa R, Manguso F, D’Arienzo A, et al. Microscopic inflammatory changes in colon of patients with both active psoria-sis and psoriatic arthritis without bowel symptoms. J Rheumatol 2000; 27: 1241-6.58. Scher JU, Ubeda C, Artacho A, et al. Decreased bacterial diversity characteriz-es the altered gut microbiota in patients with psoriatic arthritis, resembling dys-biosis in inf lammatory bowel disease. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67: 128-39.59. Baeten D, Demetter P, Cuvelier C, et al. Comparative study of the synovial histol-ogy in rheumatoid arthritis, spondyloar-thropathy, and osteoarthritis: influence of disease duration and activity. Ann Rheum Dis 2000; 59: 945-53.60. Danning CL, Illei GG, Hitchon C, Greer MR, Boumpas DT, McInnes IB. Macrophage-derived cytokine and nuclear factor kappaB p65 expression in synovial membrane and skin of patients with pso-riatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43: 1244-56.61. Paine A, Ritchlin C. Bone remodeling in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: an up-date. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2016; 28: 66-75.62. Ritchlin CT, Haas-Smith SA, Li P, Hicks DG, Schwarz EM. Mechanisms of TNF-alpha- and RANKL-mediated osteo-clastogenesis and bone resorption in pso-riatic arthritis. J Clin Invest 2003; 111: 821-31.63. Anandarajah AP, Schwarz EM, Totter-man S, et al. The effect of etanercept on osteoclast precursor frequency and en-hancing bone marrow oedema in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 296-301.64. Lories RJ, Haroon N. Bone formation in axial spondyloarthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2014; 28: 765-77.65. Ono T, Okamoto K, Nakashima T, et al. IL-17-producing γδ T cells enhance bone regeneration. Nat Commun 2016; 7: 10928.66. Gladman DD, Inman RD, Cook RJ, et al. International spondyloarthritis interob-server reliability exercise — the INSPIRE study: II. Assessment of peripheral joints, enthesitis, and dactylitis. J Rheumatol 2007; 34: 1740-5.67. Coates L. Outcome measures in psori-atic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2015; 41: 699-710.68. Coates LC, Helliwell PS. Validation of minimal disease activity criteria for psori-atic arthritis using interventional trial data. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010; 62: 965-9.69. Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 2015 treat-ment recommendations for psoriatic arthri-tis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68: 1060-71.70. Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the man-agement of psoriatic arthritis with phar-

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

n engl j med 376;10 nejm.org March 9, 2017970

Psoriatic Arthritis

macological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75: 499-510.71. Nash P, Clegg DO. Psoriatic arthritistherapy: NSAIDs and traditional DMARDs. Ann Rheum Dis 2005; 64: Suppl 2: ii74-ii77.72. Kingsley GH, Kowalczyk A, Taylor H,et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of methotrexate in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2012; 51: 1368-77.73. Kaltwasser JP, Nash P, Gladman D,et al. Efficacy and safety of leflunomide in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: a multinational, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50: 1939-50.74. Mease PJ. Biologic therapy for psori-atic arthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2015; 41: 723-38.75. Weitz JE, Ritchlin CT. Ustekinumab:targeting the IL-17 pathway to improve outcomes in psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2014; 14: 515-26.76. McInnes IB, Sieper J, Braun J, et al.Efficacy and safety of secukinumab, a fully

human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriatic arthritis: a 24-week, ran-domised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II proof-of-concept trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 349-56.77. Mease PJ, Genovese MC, GreenwaldMW, et al. Brodalumab, an anti-IL17RA monoclonal antibody, in psoriatic arthri-tis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370: 2295-306.78. Mease PJ, van der Heijde D, RitchlinCT, et al. Ixekizumab, an interleukin-17A specific monoclonal antibody, for the treat-ment of biologic-naive patients with ac-tive psoriatic arthritis: results from the 24-week randomised, double-blind, pla-cebo-controlled and active (adalimumab)-controlled period of the phase III trial SPIRIT-P1. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 79-87.79. Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, Gomez-ReinoJJ, et al. Treatment of psoriatic arthritis in a phase 3 randomised, placebo-controlled trial with apremilast, an oral phosphodi-

esterase 4 inhibitor. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 1020-6.80. Mease P, Genovese MC, Gladstein G,et al. Abatacept in the treatment of pa-tients with psoriatic arthritis: results of a six-month, multicenter, randomized, dou-ble-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II trial. Arthritis Rheum 2011; 63: 939-48.81. Beukelman T, Patkar NM, Saag KG, etal. 2011 American College of Rheumatol-ogy recommendations for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: initiation and safety monitoring of therapeutic agents for the treatment of arthritis and systemic features. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011; 63: 465-82.82. Ringold S, Beukelman T, Nigrovic PA,Kimura Y, Investigators CRSP. Race, eth-nicity, and disease outcomes in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a cross-sectional analysis of the Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Registry. J Rheumatol 2013; 40: 936-42.Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society.

The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org by RAJIV KUMAR on March 9, 2017. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2017 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved.

![Inflammatory Bowel Disease Arthropathy[1]](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/577d21e21a28ab4e1e9619b3/inflammatory-bowel-disease-arthropathy1.jpg)