PROVINCIAL RESPONSE PLAN KIRKUK GOVERNORATE · 2019-03-23 · Table 10 Main social support...

Transcript of PROVINCIAL RESPONSE PLAN KIRKUK GOVERNORATE · 2019-03-23 · Table 10 Main social support...

Local Area Development Programme in Iraq

Financed by the European Union

Implemented by UNDP

PROVINCIAL RESPONSE PLAN KIRKUK GOVERNORATE

February 2018

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

2

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

3

FOREWORD BY THE GOVERNOR

…

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

4

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

5

CONTENT

PRP Kirkuk Governorate

Foreword by the Governor ............................................................................................................................... 3

Content ............................................................................................................................................................ 5

List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................... 7

List of Tables .................................................................................................................................................... 8

Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................... 9

Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 11

1. Organisation of the PRP ............................................................................................................................... 11 2. Purpose of the PRP ...................................................................................................................................... 11 3. Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ 11 4. PRP development process ........................................................................................................................... 12

I. Context .................................................................................................................................................... 15

1. Location and administrative division .......................................................................................................... 15 2. Geography and natural resources .............................................................................................................. 17 3. Historical significance .................................................................................................................................. 20 4. Conflict ......................................................................................................................................................... 22

II. Social profile ............................................................................................................................................ 28

1. Population .................................................................................................................................................... 28 2. Living conditions .......................................................................................................................................... 31 3. IDP and Returnees ....................................................................................................................................... 36

3.1. Profile .............................................................................................................................................................. 36 3.2. Challenges facing IDPs and returnees ........................................................................................................... 37 3.3. Support to IDPs and returnees ...................................................................................................................... 41 3.4. Return process ............................................................................................................................................... 43

4. Disadvantaged host community groups ..................................................................................................... 44

4.1. Profile .............................................................................................................................................................. 44 4.2. Social protection and support for vulnerable groups through government bodies .................................. 46 4.3. Social support through international organisations and CSOs .................................................................... 48

5. Community peace-building and reconciliation .......................................................................................... 50

III. Economic profile ...................................................................................................................................... 53

1. Economic development ............................................................................................................................... 53 2. Industry ........................................................................................................................................................ 56 3. Agriculture .................................................................................................................................................... 60 4. Trade ............................................................................................................................................................. 62 5. Tourism ......................................................................................................................................................... 64 6. Private sector ............................................................................................................................................... 66 7. Investment ................................................................................................................................................... 67

IV. Public service delivery ............................................................................................................................. 71

1. Housing ......................................................................................................................................................... 71 2. Transport network ....................................................................................................................................... 72 3. Electricity service ......................................................................................................................................... 74 4. Water supply service ................................................................................................................................... 76 5. Wastewater management ........................................................................................................................... 79 6. Waste management .................................................................................................................................... 82 7. Communications .......................................................................................................................................... 83 8. Healthcare .................................................................................................................................................... 84 9. Education ..................................................................................................................................................... 89

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

6

V. Governance ............................................................................................................................................. 95

1. Local governance bodies ............................................................................................................................. 95 2. Decentralisation process ............................................................................................................................. 95 3. Departments of the Governorate Administration ..................................................................................... 96 4. Governorate budget .................................................................................................................................... 98 5. Toward effective local governance ............................................................................................................. 98

VI. SWOT analysis ....................................................................................................................................... 102

VII. Strategic objectives................................................................................................................................ 103

VIII. Programmes (priority sectors) ............................................................................................................... 104

1. Programme 1: Ensure reconciliation between communities .................................................................. 104 2. Programme 2: Ensure the return of IDPs ................................................................................................. 105 3. Programme 3: Provide support to vulnerable groups to help overcome social challenges .................. 107 4. Programme 4: Restore and develop the transport network ................................................................... 109 5. Programme 5: Restore and improve the electricity service .................................................................... 110 6. Programme 6: Restore and develop the water supply and wastewater management service ............ 112 7. Programme 7: Expand and develop waste management........................................................................ 114 8. Programme 8: Improve health services quality and access .................................................................... 115 9. Programme 9: Improve education quality and access............................................................................. 117 10. Programme 10: Encourage investment and economic development .................................................... 118 11. Programme 11: Improve public governance ............................................................................................ 121

IX. Implementation of the PRP.................................................................................................................... 124

1. Implementing structures ........................................................................................................................... 124 2. Monitoring and evaluation ........................................................................................................................ 124 3. Financial resources .................................................................................................................................... 124

Sources ........................................................................................................................................................ 125

Annex: Proposed projects per sector ............................................................................................................ 127

A.1 Transport sector projects ......................................................................................................................... 127 A.2 Electricity sector projects ......................................................................................................................... 128 A.3 Water supply sector projects ................................................................................................................... 130 A.4 Wastewater management sector projects .............................................................................................. 131 A.5 Waste management sector projects ....................................................................................................... 131 A.6 Health sector projects .............................................................................................................................. 132 A.7 Education sector projects ........................................................................................................................ 134

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

7

LIST OF FIGURES

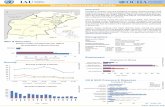

Figure 1 Kirkuk Governorate on Iraq’s administrative map 15

Figure 2 Administrative map of Kirkuk Governorate 16

Figure 3 Physical map of Kirkuk province, Iraq 17

Figure 4 Map of climate types, precipitation levels and surface water resources, Kirkuk province 17

Figure 5 Minerals and hydrocarbons in Kirkuk province 19

Figure 6 ISIL control (2014–2016) and IDP formal settlements (Dec 2017) in Kirkuk province 25

Figure 7 Population pyramid of Kirkuk Governorate, 2016 29

Figure 8 Distribution of main ethno-religious groups in Kirkuk province 30

Figure 9 Access to services indicators for Kirkuk province 32

Figure 10 Income and poverty indicators for Kirkuk province 32

Figure 11 Human development scores for Kirkuk province (range 0–1) 32

Figure 12 Spatial disparity in development in Kirkuk province in 2013 – poverty and illiteracy mapping by nahia 33

Figure 13 Education attainment levels and labour market outcomes, Kirkuk province 34

Figure 14 Most important needs of IDPs and returnees in Kirkuk province 39

Figure 15 Profile of locations where IDPs and returnees live in Kirkuk province 39

Figure 16 Structure of Kirkuk’s Administration 97

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

8

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Administrative division of Kirkuk Governorate 15

Table 2 Population indicators for Kirkuk Governorate compared to the national average, 2016 29

Table 3 Population of Kirkuk Governorate by administrative division, sex and urban/rural, 2016 29

Table 4 IOM IDP and returnee statistics for Kirkuk as of 31 Oct 2017 36

Table 5 Operational camps in Kirkuk Governorate as of end-2017 – population and needs 39

Table 6 Main organisations active in providing support to populations in Kirkuk 42

Table 7 Main IDP return push and pull factors for Kirkuk Governorate (in descending importance) 43

Table 8 Capacity for special needs care (under MoLSA) in Kirkuk province 47

Table 9 Youth Centres in Kirkuk Governorate 48

Table 10 Main social support programmes through international organisations 49

Table 11 Conference on Peaceful Coexistence Mechanisms in southwest Kirkuk province – conclusions (15 Jan 2017) 51

Table 12 Large and small industrial plants, Kirkuk province, 2013 (COSIT) 57

Table 13 Private industry indicators, Kirkuk province, 2016 57

Table 14 Arable land, cultivated land and productivity in plant agriculture in Kirkuk province for 2015 61

Table 15 Agriculture indicators for selected production, 2014 (COSIT) 61

Table 16 Tourism indicators for Kirkuk, 2013 (COSIT) 64

Table 17 Road infrastructure indicators, Kirkuk province – main, secondary and rural roads 73

Table 18 Electricity sector indicators, Kirkuk province, 2016 75

Table 19 Power transmission infrastructure affected in the context of ISIL 75

Table 20 Water supply indicators for Kirkuk Governorate 77

Table 21 Water supply service coverage in rural areas 78

Table 22 Kirkuk city sewer network 79

Table 23 Wastewater management service indicators for Kirkuk province 80

Table 24 Communications indicators for Kirkuk province, 2014 (COSIT) 84

Table 25 Public cummunications service infrastructure (telephone and optical fibre), Kirkuk province, 2017 84

Table 26 Healthcare indicators for Kirkuk province, 2014 (COSIT) 85

Table 27 Specialised medical clinics in Kirkuk province (2016) 86

Table 28 Health services provided to IDPs by health institutions in Kirkuk province in 01 July 2014–31 Oct 2015 87

Table 29 Education indicators (pre-school, primary, secondary), Kirkuk Directorate of Education, 2015/16 92

Table 30 Students enrolled in initial university studies, 2014/15, Kirkuk Governorate (COSIT) 93

Table 31 Achievements under DG Education in Kirkuk in responding to the IDP crisis in 2014/15 academic year 93

Table 32 Status of the governance decentralisation process per Law 21 95

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

9

ABBREVIATIONS

bpd Barrels of crude oil per day

COSIT Central Organisation for Statistics and Information Technology (Iraq)

CBSP Community Based Strategic Planning (process/methodology)

CSOs Civil Society Organisations

DG Directorate General

FFES Funding Facility for Extended Stabilisation (UNDP)

FFIS Funding Facility for Immediate Stabilisation (UNDP)

GoI Government of Iraq

GSP Governance Strengthening Programme, Iraq (USAID)

HE/HEI Higher education/ Higher Education Institution

IDPs Internally displaced persons

IED Improvised explosive device

IHSES Iraq Household and Socio-Economic Survey

IOM International Organisation for Migration

IRC International Rescue Committee

ISIL Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (aka ISIS)

KDP Kurdistan Democratic Party

KRG Kurdistan Regional Government

KRI Kurdistan Region of Iraq

LADP Local Area Development Programme (EU funded, UNDP implemented)

Law 21 Law of Governorates Not Incorporated into a Region – aka. Provincial Powers Act (2008)

MoCHPMW Ministry of Construction, Housing, Municipalities and Public Works (Iraq)

MoE Ministry of Education (Iraq)

MoHESR Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research (Iraq)

MoLSA Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (Iraq)

MoMD Ministry of Migration and Displacement (Iraq)

MoP Ministry of Planning (Iraq)

MoT Ministry of Trade (Iraq)

MoTC Ministry of Transport and Communications (Iraq)

MoWR Ministry of Water Resources (Iraq)

MoYS Ministry of Youth and Sports (Iraq)

MPs Members of Parliament (Iraq)

NFI Non-food items

OPF Operation Iraqi Freedom

Peshmerga Iraqi Kurdish militias of the KDP and PUK, both loyal to the KRG

PMFs Popular Mobilisation Force units

PPP Public-Private Partnership

PRP Provincial Response Plan

PUK Patriotic Union of Kurdistan

PwDs Persons with disability

QC Qadha Centre

TDS Total dissolved solids

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

UNHCR United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

UNICEF United Nations Children's Fund

UNOPS United Nations Office for Project Services

UNWTO World Tourism Organisation (United Nations agency)

USAID United States Agency for International Development

UXO Unexploded ordnance

WASH Water, sanitation and hygiene

WHO World Health Organisation

WWTP Wastewater treatment plant

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

10

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

11

INTRODUCTION

Kirkuk is one of Iraq's governorates worst affected by the 2013–2014 ISIL invasion. Heavy combat drove waves of displaced people from and into Kirkuk. Kirkuk hosted the second highest number of IDPs from other Iraqi provinces (after the KRI); IDPs in Kirkuk province numbered almost half a million at the height of displacement; while more than a fifth of Kirkuk’s population remain in displacement. The toll on infrastructures and the economy has been significant as well. Fighting in the province continued through Oct 2017. In the post-ISIL context, attention turns to (1) rebuilding of communities and (2) sound solutions to public service delivery – in order to set the basis for longer-term development of the governorate. In this regard, with support from LADP, the authorities of Kirkuk Governorate have set out to elaborate a Provincial Response Plan (PRP) for the period 2018–2022.

1. Organisation of the PRP

The Plan consists of two main integral parts – vulnerability assessment and strategic part:

The vulnerability assessment reviews the situation – prior to and following ISIL – in three strategic areas: (1) community development, (2) economic development, and (3) provision of public services.

1 For each

strategic area, a number of indicators have been researched in order to provide a full picture of the conditions in the governorate.

Based on the vulnerability assessment, the strategic part includes: SWOT analysis; a list of identified strategic objectives; and a list of identified priority areas for development (programmes). Several projects have been identified in series of workshops and consultations by the working groups with the support from the experts for each programme that will help return people in the governorate to normal life.

2. Purpose of the PRP

The Provincial Response Plan (PRP) sets a framework for actions to be taken by the governorate with support from the central authorities and international donors. It provides provincial authorities with an instrument to help them:

Better monitor the progress of the reconstruction, planning and prioritisation of development actions;

Coordinate the efforts of international donors – given the limited resources of the national and provincial budget;

Better recognise what additional technical support they need.

At the same time, the PRP aims to direct the efforts of the provincial authorities from immediate post-conflict stabilisation toward longer-term development. Currently, Kirkuk is mainly a recipient of international aid and central budged instalments. Through the Plan, the Governorate will become the leading partner in its development process and it will proactively pursue its objectives – including through implementation of public-private partnerships (PPPs) and cooperation with the international donors and investors and local community.

The PRP is a living document that will be periodically reviewed and updated as required. As Kirkuk Governorate moves forward in addressing pressing developmental issues, it will be more important than ever to ensure that the efforts of government and international agencies are synchronised and leveraged as part of a holistic and sustainable response.

3. Methodology

Traditionally in Iraq the planning process is highly centralised. Therefore, LADP supports the development of a participatory planning approach to formulate prioritised objectives and strategies to address the key security, governance, economic, and social challenges that the target governorates are facing (Anbar, Diyala, Nineveh, Salah al-Din and Kirkuk). Through the participatory approach several goals are achieved: help strengthen

1 Data collection toward Vulnerability Assessment was not possible in Al-Hawiga Qadha and Al-Rashad (Daquq Qadha) due to these areas still being under ISIL control at the time (they were liberated in Oct 2017).

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

12

democracy; reduce corruption; limit differences among various political and ethnic groups; and empower citizens by promoting greater interaction between stakeholders within communities. Participatory planning creates a fair process to prioritise development and implementation of projects and fosters a sense of ownership of development programmes.

Therefore, the development of PRPs under LADP has followed the Community Based Strategic Planning methodology (CBSP).

Strategic planning. Strategic planning was the selected approach because it differs from the traditional model of comprehensive planning in several important ways:

Strategic planning is pro-active. Through the strategic planning process, the community seeks to shape its future – not just prepare for it;

Strategic planning focuses only on the critical strategic issues and directs resources to the highest priority activities. Setting priorities is necessary because the resources available to the local government (governorate) are less than the demands on them. By contrast, comprehensive planning covers all activities that must be done without indicating which ones are the most important;

Strategic planning is led by those tasked to implement the resultant strategic plan; it entails ownership. By contrast, a comprehensive plan prescribes who should implement it but it does not require the inclusion of those entities in the strategic planning process.

Community-based planning. Community involvement strengthens strategic planning in several ways:

Transparency: While the strategic plan establishes priority areas for development, it has political as well as economic dimensions. Community involvement contributes to a transparent process.

Implementation/resource mobilisation. Community involvement promotes the plan implementation. Beyond government resources, it helps mobilise the resources of the community toward achieving the economic goals. Successful strategic planning involves the entities that will be tasked with the implementation of the plan.

Support and credibility: Participation of community leaders in plan development gives the resulting plan credibility in the community. Consensus among Project Steering Committee members promotes a community consensus in support of the Plan.

4. PRP development process

The development of PRP following CBSP methodology entails the process of (1) establishment of a coordination group, (2) collection of baseline information, and (3) identification of strategic areas of intervention by involving relevant stakeholders.

However, due to the specifics in the environment in the LAPD target cluster of governorates (i.e. post-war conditions of damaged infrastructure, security, fragility and large number of IDPs), the main priority areas were set at the beginning of the planning process – rather than identifying them based on detailed research on the current situation in the governorate. They are based on the initial meetings with the established Steering Committee and Technical Group for the preparation of the PRP in Sept 2016. The main priority areas identified are: community development, economic development, and provision of public services.

The Project SC in each province has had to weigh in many factors while integrating the summary action plans into a coherent strategic plan for development. In some cases, the availability of resources could only be assumed – e.g. financial allocations from the central budget, grants from international donors and (PPP-based) private investments.

Implementing the CBSP methodology for the development of the PRP has embedded two key concepts: on-the-job-training and learning-by-doing. E.g. Kirkuk Governorate staff and other stakeholders have benefited from trainings and support from the LADP experts; while people from the governorate involved in the preparation of the PRP have contributed information and findings. These two concepts have been streamlined throughout the process of PRP preparation – from the first meetings with the PSC until the completion of the PRP.

The thirteen-step approach to Community-Based Strategic Planning has been integrated into the main activities of the preparation of the response plan.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

13

13-step CBSP process

Initiate process and make decision on strategic planning activity; 1.

Organise the Public-Private Strategic Planning Task Force (Steering Committee); 2.

Develop vision of the economic and social future of the province in the next planning period; 3.

Identify stakeholders (stakeholders management); 4.

Develop and analyse baseline data – including, in parallel: 5.

Collect data on socio-economic trends;

Collect data on Key industries;

Collect data on economic development infrastructure; and

Conduct business survey;

Conduct SWOT Analysis; 6.

Identify strategic issues; 7.

Identify critical strategic issues; 8.

Establish Action Groups around critical strategic issues; 9.

Apply Logical Framework Approach (LFA): 10.

Develop a problem tree;

Develop an objective tree (and identify strategic objectives);

Build Log Frame Matrix for each activity;

Develop Action Plans to address critical strategic issues – incl. build an Action Planning Group around 11.each critical strategic issue;

Integrate Action Plans into PRP (this document); 12.

Prepare Plan for implementation, evaluation and updating the PRP. 13.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

14

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

15

I. CONTEXT

1. Location and administrative division

Located 255 km north of Baghdad, Kirkuk is an important economic centre, key to Iraq’s oil industry. The location of Kirkuk province is of particular importance for Iraq as a link between the northern mountainous areas and the southern plains; as such, it is strategic for security and trade. Highways Baghdad–Kirkuk-Erbil-Mosul-Turkey and Kirkuk-Suleimaniah-Tehran provide quick access to all Iraqi territories.

Kirkuk has undergone a number of administrative transfers, linked to economic priorities and demographic shifts, but also very much to struggles for political-economic control and power – particularly, the establishment and recognition of the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). Its borders with Kurdistan areas are still contested today.

Currently, Kirkuk Governorate covers an area of 8404.3 km2 (1.92% of Iraq).2 It has joint administrative borders

with Suleimaniah, Salah al-Din, Nineveh and Erbil governorates (see Figure 1). It is sub-divided into four qadhas – Kirkuk, Al-Hawiga, Daquq and Dibis – and 16 nahias (see Table 1, Figure 2). The main cities are Kirkuk (the capital) and Al-Hawiga.

Table 1 Administrative division of Kirkuk Governorate

N Qadhas (regions) Nahias (districts) Nahias (n) 1 Kirkuk Kirkuk Qadha Centre, Yaychi, Alton Kobry, Al-Multaka (Mula Abdullah), Taza Khormato,

Laylan, Shwan, Qara Hanjeer (Al-Rabee) 8

2 Al-Hawiga Al-Hawiga Qadha Centre, Al-Abbasi, Al-Riyadh, Al-Zab 4 3 Daquq Daquq Qadha Centre, Al-Rashad 2 4 Dibis Dibis Qadha Centre, Sarkran (Al-Qudis) 2

Figure 1 Kirkuk Governorate on Iraq’s administrative map

Legend: Yellow – Kirkuk; Beige – KRG-controlled areas; Stripes – contested areas.

2 The total area of Kirkuk province (8404.3 km2) is given as the sum of areas per nahia provided in Kirkuk Governorate (2016), Strategy of Kirkuk Governorate for Re-stabilization, Sheltering Displaced and Rebuilding of Liberated Areas. We note that this differs from the total governorate area provided by COSIT for 2015: 9679 km2 (or 2.2% of Iraq’s territory).

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

16

Figure 2 Administrative map of Kirkuk Governorate

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

17

2. Geography and natural resources

Landscape and geology

Kirkuk province is part of the foothills fold and thrust zone of the Taurus-Zagros Belt formed during the collision of the Arabian and Eurasian Plates, with the Zargos mountain rising toward the east (the border with Iran). This is a basin of molasse sediment accumulation, characterised by long folds and broad synclines. The area presents with folding and cycles of sedimentary rocks mainly from Neogene/Miocene (sandstone, gypsum). Faults are very significant in groundwater movements, while the sedimentary rocks hold high potential for groundwater storage. The depositional environment and tectonic history condition the formation and trapping of petroleum.

In terms of landscape, except in the very east of the province, this is a level plain (see Figure 3), interspersed with a series of long low mountains with SE–NW orientation as defining features, e.g. (E–>W): the Hamrin Mountains (410 m.a.s.l), which stretch along the Kirkuk–Salah al-Din border from Beygee in Salah al-Din to Adhaim in Diyala; Mount Twsaqali (360 m.a.s.l.) south of Kirkuk city, which marks the border between Kirkuk and Daquq qadhas; Mount Batiwa west of Kirkuk city (355 m.a.s.l.), which connects north to Qarachuq Mountain in Makhmoor (Nineveh); Qani Domlan Ridge (ca. 440 m.a.s.l.), which starts east of Kirkuk city, crosses Dibis Qadha and further north forms part of the Nineveh–Erbil border; and. The highest point of the Zagros mountain range in Kirkuk province is in Mount Sufa Pach on the border with Suleimaniah (ca. 1120 m.a.s.l.).

3

Figure 3 Physical map of Kirkuk province, Iraq4

Figure 4 Map of climate types, precipitation levels and surface water resources, Kirkuk province

Climate

The majority of Kirkuk qadha falls in the belt of warm semi-arid climate (BSh by Köppen–Geiger) (see Figure 4). This is positioned in ecological characteristics and agricultural potential between desert and humid climates, allowing relatively extensive rain-fed agriculture. The annual average temperature is ca. 20°C, and precipitation is overall minimal – ca. 300 mm. In Kirkuk city, the annual average temperature is 21.6°C; temperatures are highest in July (ca. 34.6°C average) and lowest in January (8.7°C average); the annual precipitation is 365mm (low), none in the summer, and peaking in March.

5 Toward the south-east of the province, the annual

precipitation is less (ca. 250mm), which requires irrigation to sustain crops growth.

In the very north-east of the province, near the border Salah al-Din–Erbil–Suleimaniah border, limited areas of cold semi-arid climate (BSk) present with temperate climate, bordering on Mediterranean: with hot summers, cold winters, major temperature swings between day and night (sometimes by as much as 20°C), annual average temperature of ca. 18°C, and moderately low precipitation (ca. 550mm), with wetter autumns and springs than elsewhere in the province.

3 To compare, Kirkuk city is located at ca. 340 m.a.s.l. 4 Adapted from Fatih, S. (May 2016 – in the frame of UNDP/LADP), Overview of Kirkuk Governorate (محة ظة عن عامة ل وك محاف رك .(ك5 https://en.climate-data.org/location/2920.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

18

Overall, in Kirkuk province, temperatures range between 5–8°C in the winter and 40–45°C in the summer. The wet season lasts from November to April; the dry season – from May to October. During the winter rains, rivers carry brief but torrential floods. The flooding season peaks in April and ends in May. Sand and dust storms rage for 20–50 days each summer. Precipitation is overall minimal. Except in the north-east, the actual precipitation is less than half the level of potential evapotranspiration,

6 and it is virtually none in the summer. Precipitation in

the BSk zone upstream of the Little Zab from Salah al-Din is key to securing the water flow and aquifer recharge in the province. At the same time, there has been significant decline in rainfall in recent years.

7

Water resources

Kirkuk province is strategically located with regard to surface water resources (see Figure 2). It is located in the east of the Tigris catchment area. The main perennial rivers are the Tigris and the Little Zab. The Khasa (which flows through Kirkuk city) and Daquq rivers are winterbourne; they tend to dry up in the summer, but can turn into raging rivers in late winter.

The governorate increasingly depends on groundwater for domestic and agricultural activities. However, with regard to groundwater resources, Kirkuk Governorate faces deficiency due to drought and pollution of surface and groundwater resources (from poor waste/wastewater management, including households, agriculture and industries), in addition to the irrational use of water. In the low folded zone, the aquifer consists of sedimentary formations and there is hydraulic continuity across the formation; groundwater movement is typically from north–northwest to south–southeast. Precipitation is the main form of groundwater recharge – while precipitation has been declining. Generally, the salinity of the groundwater increases from north to south, and from recharge sources in the high land areas toward discharge areas in the south and west of the province. Groundwater quality is mainly bicarbonate at recharge areas, and it becomes sulphuric at discharge areas. Due to effects of human, animal and agricultural activities, throughout the province, the Water Quality Index (WQI) values for wells decline from “good” to “poor” along the downstream of rivers. TDS

8 in drinking water originate

from natural sources, but particularly from sewage, urban run-off, agriculture, industrial wastewater, outdated water supply systems, etc. Therefore, groundwaters toward the south and west of the province have particularly high levels of TDS, especially organic contamination, as well as increase in the concentration of heavy metals.

Soils and vegetation

Two ecological regions present in the province: (1) Mesopotamian shrub desert in the south-west (dominant); and (2) Middle East steppe in the north-east.

The Mesopotamian shrub desert is characterised by deserts and xeric shrublands. Because biomass productivity is low, the litter layer is almost non-existent and the organic content of surface soil layers is very low. Also, evaporation tends to concentrate salts at the soil surface. Sensitivity to disturbance – from grazing, soil disturbance, burning, ploughing, and other cover alteration – is very high, and restoration and regeneration potential tend to be very low. The conversion of productive drylands to desert conditions (desertification) can occur from due to intensive agricultural tillage or overgrazing. A tendency to desertification becomes more pronounced with climate change.

The Middle East steppe is characterised by temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands. Soils are relatively fertile and richer in nutrients and minerals. Herbaceous and dwarf shrub communities tend to dominate in deeper, non-saline soils and often occur in association with short grasses where disturbed by grazing. The combination of arid steppe and riverine habitat allow this area to support a tremendous diversity of bird species that depend on both arid areas and wetlands. Extensive overgrazing by domestic livestock contributes to the alteration and degradation of vegetation communities.

Overall, the conditions are present for development of plant agriculture (especially in the north-east of Kirkuk province, as well pastures/animal herding. However, increasingly toward the south-west: (1) organic matter and nitrogen in soils decrease, and calcareous content and salt concentration increase; (2) the soil climate is extreme, surface soil horizons are very dry and hot, making chemical weathering and soil formation extremely slow (physical weathering predominates); (3) the potential productivity of soils depends on the supply of adequate water and nutrients; while (4) soils become more vulnerable, including to desertification.

6 The amount of water that would be evaporated and transpired if there were sufficient water available. 7 It is estimated that precipitation in the Middle East has dropped by 30% between 2005 and 2009 alone. See UN-ESCWA (Nov 2012), Groundwater and Water Management Issues in the Middle East – presentation: https://bit.ly/2KBH8E6. 8 Total dissolved solids (TDS) is a measure of the combined content of all inorganic and organic substances contained in a liquid in molecular, ionized or micro-granular suspended form. TDS refers to any minerals, salts, metals, cations or anions dissolved in water - including inorganic salts (salt, calcium, magnesium, sulphates, etc.) and organic matter.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

19

In Kirkuk province, the sustainability of water resources is at risk, with severe impact on the environment, economy and human health. Both water conservation and degradation of water quality need to be a concern.

With regard to water quantity, dams and water projects constructed upstream (KRI, Turkey) have significantly reduced river flow into Kirkuk province. Fluctuations in the Tigris water flow are caused by non-compliance with water quotas among the countries on the river; while recharge of the Little Zab and Khasa rivers and associated groundwaters has been increasingly limited by decline in precipitation. In this context, groundwater overuse and groundwater mining are further threats. In turn, reduced river flow factors in increased soil erosion and increased incidence of heat and dust storms, with impact on health, productivity, and soil and vegetation status.

With regard to water quality, the decreasing river flow and high temperatures increase the salinity level of water. Also, while the rivers are the main source of drinking water for people in Kirkuk, the lack of wastewater treatment plants in cities along the river poses a massive threat to the environment, public health, human and economic development in the governorate.

Soil degradation is another major problem in the province related to industrial pollution, water use and inappropriate agricultural practices. In irrigated areas, soil salinization results from accumulation of soluble salts in the upper parts of the soil profile – mainly linked to poor drainage systems. Both are exacerbated by the dry hot climate and high evaporation rates. It has impact on agricultural production, food security, environmental health, and economics. Desertification is also a concern, caused by a combination of natural (drought conditions, wind erosion) and human-driven factors (e.g. over-grazing, vegetation stripping).

All these threats are only going to increase in the context of climate change, the effects of which are already evident across Kirkuk province – including increased severity of droughts. E.g. by IOM data, in 2010, displacement due to drought in Kirkuk province was among the highest in Iraq (500+ families).

9

Measures to improve the management of soil and water resources are required. It is important that together the provincial and central authorities work to develop short- and long-term solutions to ensure sustainability of soil and water resources, e.g.: conserve freshwater ecosystems; expand wastewater treatment; limit pollution from agriculture and industry; develop rainwater collection; reuse all forms of water and (treated) wastewater; raise public awareness regarding water use; research and development in sustainable agriculture and irrigation methods; etc. Certain measures to address desertification are already underway by the Ministry of Agriculture – e.g. the establishment of desert oases.

Mineral and hydrocarbon resources

Figure 5 Minerals and hydrocarbons in Kirkuk province10

9 IOM infographic in UN-ESCWA (Nov 2012), Groundwater and Water Management Issues in the Middle East, p5: https://bit.ly/2KBH8E6. 10 Adapted from (1) Minerogenic map of Iraq, Geoserv-Iraq (available at: http://bit.ly/2BYxbLs), (2) EIA (2012), Major fields and infrastructure in Iraq – map available at: https://fanack.com/fanack-energy/Iraq; and (3) Platts.com (2014 data): https://bit.ly/2rkT8B4.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

20

Kirkuk has vast deposits of oil (see Figure 5). The giant Kirkuk oil field discovered 1927 has estimated reserves of 8.5 billion barrels of recoverable oil. Most of the oil deposits are associated with natural gas.

11 Due to the oil-rich

environment, abundant asphalt and bitumen deposits exists as well (for asphalt production/road construction). Hydrocarbons are used in the petrochemicals industry; natural gas can also serve for production of electricity. Oil and gas are strategic resources in the province, linked to conflict and border disputes.

Kirkuk province is relatively poor in the variety of mineral deposits additional to hydrocarbons. Nevertheless it does have substantial reserves of gravel and sand (for use in construction) and gypsum (for production of plaster for decoration and in the cement industry), which provide a basis for industrial activities.

Industrial pollution – including pollution of water resources, soils and air – is a major problem in the governorate, with impact on public health and the resources available for agriculture. E.g. in the case of oil and natural gas production, so-called “produced water” comprises the largest by-product stream; this may contain hundreds of individual chemicals, some known to be detrimental to public health and the environment. In the context of weak environmental regulation, most of this ends up in surface/groundwater resources and soils. Asphalt production in the province is particularly polluting.

Pollution from industry has been exacerbated in the context of conflict. E.g. in 2005, Kirkuk was covered with a thick pall of smoke after fighters attacked the oil and gas infrastructure. Post-ISIL, there is specifically concern regarding environmental and health hazards related to burning of oil fields, bombed refineries, and the destruction of sensitive industrial locations (such as chemical plants, etc.). E.g. destruction of Beygee oil refinery in Salah al-Din drove fumes of toxins and water resource pollution in Kirkuk province. Post ISIL., in many areas, residents return to extremely polluted air, poisoned soil, and waterways clogged with crude oil.

With additional effect on air quality, the dramatic increase in population (especially urban population) has led to huge increase in the number of vehicles and the rates of gasoline and fuel consumption, posing an additional threat to public health.

The Governorate Authorities need to recognise that the environment is a crucial part of people’s lives; and in rural areas, it is their livelihood. Measures to contain and reduce pollution – increased control, modern technology adoption for pollution reduction and beneficial reuse of industrial waste/wastewater, etc. – are central if the governorate is to achieve improved living conditions and sustainable growth across sectors. Air pollution from traffic can be targeted by e.g. introduction of green belts on urban areas, increase in park areas, and improvement of public transportation systems.

3. Historical significance

Kirkuk’s archaeological remains date back to the 7th c. BC. The site Qal'at Jarmo (dated ca. 6750 BC by latest estimates) is Iraq’s most important Neolithic site and site of the earliest agricultural community in West Asia. Thus, Kirkuk is the oldest site of continuous human occupation in modern-day Iraq. According to the Department of Antiquities, Kirkuk province contains 700 archaeological sites, of both historical and religious value.

Antiquity

The modern-day city of Kirkuk sits on the ruins of the ancient city of Arrapha (Arava) on Khasa River (first mentioned ca. 2400 BC). The area became a part of the Akkadian Empire (2335–2154 BC) which united all Akkadian- and Sumerian- speaking Mesopotamians under one rule. After the collapse of the empire, the area was successively ruled by Guti (Kurdish ancestors), Neo-Sumerians, Assyrians, Babylonians, and Hurri-Mitanni. In the 18th c. BC under Assyrian and Babylonian rule, Arrapha was an important commercial centre; it reached great prominence in the 11th and 10th c. BC as a part of Assyria and an important garrison town; and it was one of the last strongholds of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911 BC–609 BC). Thereafter, Arrapha fell successively to Persian, Macedonian and Seleucid rule. Under the Seleucid Empire (312–63 BC), the settlement was refounded under the Syriac name Karka. In ca. 150 BC–280 AD, Arrapha-Karka was the capital of a small Neo-Assyrian kingdom. This was subsumed under Sassanid-ruled Assuristan (Assyria) until the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 602–628 AD and the consequent Arab Islamic conquest, when Assuristan was dissolved and Arrapha-Karka eventually became Kirkuk.

11 Detailed information on the field – including oil quality, geology, production constraints, cf. e.g. Al-Rawi, Munim (2014), “Reservoir Management: Kirkuk – A Silent Giant Oilfield”: https://www.geoexpro.com/articles/2015/02/kirkuk-a-silent-giant-oilfield in GEO ExPro, Vol. 11, No. 6 (2014).

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

21

Ancient Arrapha has never been excavated. The Kirkuk Citadel dates in part to the Neo-Assyrian and Seleucid periods (see Box below). Yorgan Tepe near Kirkuk is the site of the ancient city Nuzi – a centre of provincial administration in the Hurri-Mitanni empire. Excavations have revealed a palace, decorated with mural paintings, elaborate provisions for drainage/sanitation, temple, and an archive of 20 000 cuneiform tablets in Akkadian.

Islamic period

In the 7–10h c. AD, the area of Kirkuk remained part of the Islamic Caliphate under the rule of Seljuk Turks. After the Mongol invasion of the 13th c, the area became a part of the Mongol Ilkhanate, which was in turn conquered by Kara Koyunlu Turkomen and Ak Koyunlu Turkomen. During the Umayyad (661–750 AD) and Abbasid (750–1258 AD) periods, Turkmen began migrating to Kirkuk, and they have comprised a significant ethnic minority since the 11 c. AD (further waves of Turkic migration followed in the Ottoman period). A minority of Arabs and Assyrians/Christians inhabited the region too, while Kurds formed the majority of the population.

Sites from this period include e.g. Sheikh Hammad and Imam Ismail b(in Hawiga) (Abbasid period); the domes and minarets of Nabi Daniel Mosque (13 c.); Khatoon Baghdi (Gok Kumbet) built around a Seljuk mausoleum (1361); the Green Dome Mosque (1362); the ruins of the Em Al Ahzan Chaldean Catholic Cathedral (known as the “Red Church” – 13 c.); etc. (see Box below). A number of Arabic scripts are also preserved.

Ottoman period

Kirkuk was assimilated into the Ottoman Empire in 1538, under Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent, Kirkuk was capital of the province of Shahrzur of the Ottoman Empire until the formation of Wilayat Mosul in 1879, which included Kirkuk. Ottoman authorities empowered the local elite (Kurdish and Turcoman families), who they perceived as key agents in maintaining a cohesive, unified empire. The majority of the elite families preserved Sunni orthodoxy; Shia populations were sometimes persecuted in the context of the Ottoman-Persian wars; but overall there was peaceful multi-cultural coexistence. In the early 1900s, Kirkuk city was inhabited mainly by Turkomen and the surrounding areas by Kurds.

Historical sites from this period are abundant (e.g. the gates of the Tash Kopru bridge across the Khasa in Kirkuk). Among the key ones, the Qishla of Kirkuk was built in 1863 to be the headquarters of the Ottoman army in Kirkuk. Al-Qaysareyah Market – the oldest market in Kirkuk – was built in ca. 1855; its layout symbolizes the hours, days, and months of the year.

The Kirkuk Citadel – the oldest structure in Kirkuk city – is a symbol of Kirkuk’s rich multi-cultural past. The Citadel holds great importance in Kirkuk province and city as a symbol of shared heritage, unity and peaceful coexistence of the different groups in the community – Kurds, Assyrians, Turkomen and Arabs.

The Citadel goes back to the dawn of the Sumerian dynasties. Its tell is believed to have been built by the Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal II (9 c. BC) as a military defence line of Arrapha. Under Seleucus I Nicator (3 c. BC), a strong rampart was built with 72 towers and 2 entries into the citadel. The modern walls go back to the Ottoman period.

The site occupies ca. 200 000 m2 in the heart of Kirkuk city. Until the 1990s, it was inhabited by Kurdish and Turkomen families, both groups in their own streets which had been inhabited for centuries; in the Hamam neighborhood, Muslims and Christians had lived together. In 1997–1998, the Regime carried out a "beautification" programme of the area; in result, inhabitants were expelled; structures within the Citadel walls were largely demolished; of more than 650 traditional houses, only 45 remain.

A jewel of the citadel is the “Red Church,” distinguished by pre-Muslim mosaic engravings. The citadel also houses the two principal religious sites in Kirkuk: Nabi Daniel Mosque and Green Dome Mosque (Islamic period). Nabi Daniel Mosque includes a tomb, attributed to the biblical Prophet Daniel. The site was a Jewish synagogue, then a Christian church, and finally a Muslim mosque.

Kirkuk Citadel and Al Qaysareyah Market, Kirkuk.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

22

Aftermath of WWI

During WWI, the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement divided Ottoman Arab provinces into areas of British or French influence, without regard to ethnic-religious characteristics; Kirkuk fell into British control. In the wake of WWI, the area became part of the British Mandate over Mesopotamia. The British attempted to create an autonomous Kurdish entity including Kirkuk.

12 Ultimately, the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne made no provision for a

Kurdish state, leaving large Kurdish populations as minorities in their respective countries. Kirkuk was not a part of the Kurdish uprisings of 1920-24; the province was however strongly disputed between the Turks and the British. Iraq's possession of Wilayat Mosul (including Kikruk) was brokered between Turkey and Great Britain in 1925, and in 1926 Kirkuk became part of the Kingdom of Iraq.

In 1927, drillers working for the British-led Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC) struck a huge oil gusher at Baba Gurgur near Kirkuk, and so the giant Kirkuk oilfield was discovered. The oilfield was brought into production by the IPC in 1934 when 12-inch pipelines from Kirkuk to Haifa and Tripoli (Lebanon) were completed. Thereafter, the political and economic importance of the region grew steadily, linked to the discovery of oil. Oil extraction and trade increasingly became the leading economic factor in the province.

The presence of the oil industry had a huge effect on Kirkuk's demographics. Population and urbanisation both quickly increased; many Kurds and Arabs moved to Kirkuk city; the share of Arabs in the province increased; while Kurdish populations from the mountains increasingly populated uninhabited but cultivatable parts of the province. In the 1940s and 1950s, the IPC played a central role in the urbanization of Kirkuk, initiating housing and development projects in collaboration with Iraqi authorities. According to the 1957 census, the population of Kirkuk province included 48.2% Kurds, 28.2% Arabs, 21.4% Turkomen, and 2.2% minorities (Assyrian/Chaldean Christians, Yazidis, Jews, etc.) (in total 97% Muslims); while Kirkuk city included 37.6% Turkomen, 33.3% Kurds, with Arabs and Assyrians making up less than 23% of its population.

4. Conflict

Kirkuk is particularly ethnically heterogeneous territory. Given Kirkuk’s history (above), it is understandable that Kurds, Turkomen and Arabs all ascribe great symbolic importance to Kirkuk city as a central element of each group’s history, culture and identity. Historically, the province has witnessed many periods of peaceful and tolerant living together of all the different ethno-religious groups. However, from the 1920s on, Kirkuk’s rich multi-ethnic culture has been overshadowed by oil-driven conflict.

Particularly since the 1970s, the oil riches of Kirkuk have been at the basis ethnopolicy, ethnic-based disputes and conflict in the region – all seeking to increase political control of and thereby economic gains from the Kirkuk region. These have politicised ethnic divisions. Thus, from the 1970s, Kirkuk has been an arena of internal displacements and (often violent) demographic shifts, which have weakened community ties in the province. In post-Baathist Iraq, Kirkuk is a microcosm of the most significant unresolved issues: territorial disputes, the allocation of budgets and division of hydrocarbon resources, and the power of the provinces vis-a-vis Baghdad.

In this context, tensions among Arabs, Kurds, and Turkomen have continued potential to escalate into intercommunal violence – especially as they have been fuelled in the context of ISIL.

Ba’athist regime (1968–2003), Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988) and Gulf War I (1990–1991)

Following the 17 July Revolution coup in Iraq (1968), Arabisation (Ta’rib) was pursued by the Ba’athist regime – systematic effort to instil national unity via collective Arab identity. The process included suppression of Kurdish nationalism and forced displacement of Kurds from Kirkuk and other (mainly oil-rich) parts of Iraq; Arabs were encouraged to relocate to vacated areas. Also, the lands of (Shi’a) Turkomen (e.g. in Taza and Daquq areas of Kirkuk) were seized and subsequently leased to Arab settlers. Also, “national correction” was initiated, whereby Kurds and Turkomen were forced to register as Arabs.

At the same time, amid regional power struggle, Iran and Iraq both encouraged separatist activities by Kurdish nationalists in the other state. Following the Iranian Revolution (1979), Iraq initiated a military campaign to take over Iran’s south-western oil fields, which quickly turned into the Iran-Iraq War (1980–1988).

12 The (abandoned) Treaty of Sevres from 1920 envisioned Kurdistan borders roughly corresponding to areas claimed by the KRG today. The rise of Atatürk in Turkey weakened Kurdish efforts for autonomy in the region.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

23

The war amplified tensions between Ba'athist Iraq and the Peshmerga and sparked large-scale uprising against the Regime. The Regime responded with a ‘purification’ campaign in Iraq that included systematic destruction of settlements, mass killings, mass deportations, concentration camps, executions, and chemical warfare against Kurds, but also heavily targeting Yazidis, Assyrians/Christians and Shabaks – culminating in the Anfal campaign (1986–1989). After the collapse of the uprising in March 1991, as Iraqi troops advanced into Kurdish areas, and a vast wave of 1.5 million Kurds abandoned their homes and fled to the Turkish and Iranian borders.

By 1988, falling oil prices and war debts contributed to a worsening economic crisis in Iraq, precipitating Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the Gulf War I (1990–1991). In the aftermath of the Gulf War, sanctions were imposed on Iraq (1991–2003). Iraq was banned from importing anything not expressly permitted by the UN; foreign companies were stopped from doing business with Iraq; oil production dropped by 85%; non-oil industry and agriculture severely contracted. GDP per capita – USD 2836 in 1989 -- fell to USD 174 by 1994. Public service delivery was made near impossible; public spending on e.g. roads, water supply, healthcare and education plummeted. The impact on human development was great. Poverty, infant/child mortality, and malnutrition soared; and enrolment rates and quality declined at all levels of the education system.

Because of its oil and strategic value to the government, as well as its ethic mix, Kirkuk was particularly affected by this entire process:

In March 1970, an Autonomy Agreement was signed, which recognised the legitimacy of Kurdish participation in government and Kurdish language teaching in schools, while it reserved judgment on the territorial extent of Kurdistan, pending a new census. In 1972, the Iraqi Government nationalised the Iraqi Petroleum Company (Kirkuk petroleum only). In 1974, the Iraqi Government unilaterally decreed a new statute, where the definition of Kurdish autonomous area excluded the oil-rich areas of Kirkuk, Khanaqin (Diyala) and Sinjar(Nineveh). Violence broke out;

At this time, the Regime also carried out a comprehensive administrative reform, whereby Kirkuk governorate border changes were enacted to support Ta’rib: the old Kirkuk province was split in half; Kurdish-dominated districts were added to Erbil and Suleimaniah provinces; Arab-dominated districts – to Kirkuk; and Turkomen villages – to Diyala and Salah la-Din. In 1976, Kirkuk Governorate was renamed to At-Ta'mim Governorate, which means “nationalisation” and refers to the importance of national ownership of the regional oil and natural gas reserves (Kirkuk retained this name till 2006);

In 1986, Kirkuk became a battleground as Iranian forces and Kurdish PUK guerrillas attacked several objectives in the area including oil refineries;

Persecution by the Regime of Kurds, Shi’ia Turkomen and minorities continued late into the 1990s. Estimations show that ca. 150 000 Kurds were forcibly evicted in 1991 alone;;

The overall impact on the population profile of Kirkuk has been profound change. The UN estimates that almost 500 000 Kurds in total were forced to flee Kirkuk during the Ba’athist regime. The share of minority groups decreased drastically – e.g. the share of Turkomen fell from 21.4% to 7%. At the same time, between 1957 and 1997 the share of Arab population of the province grew from 28.2% to 72% – with almost five-fold growth in absolute numbers (from 110 000 to 544 000).

All these events have a direct bearing on Kirkuk’s security today. The combination of warfare, displacement and sanctions politicised and aggravated ethnic divisions in the province, intensified the urban-rural development divide, and increased the share of urban poor – setting the stage for radicalisation in the following period.

Iraq War (2003–2011) and Iraqi insurgency (2003–2013)

The protracted Iraq War began with the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 which toppled the Ba’athist regime. Coalition forces captured Baghdad on 09 April 2003; Kirkuk surrendered to US control on 10 April 2003. In the power vacuum that ensued, Iraq’s internal divisions were exacerbated.

Following the invasion, the Kurdish Peshmerga forces briefly occupied Kirkuk; the coalition forces forcibly withdrew Kurdish forces from the governorate. In Jan 2010, the Coalition forces introduced in Kirkuk “Combined Security Force” units, comprised of Iraqi soldiers and police officers, US soldiers, and Kurdish soldiers from the Peshmerga militia. Still, anger and opposition grew fast in response to the occupation, especially among the Sunni population. Turkmen and Arab populations were particularly angered by visible display of authority by Kurdish authorities and security forces, while many Kurds opposed the presence of Iraqi Government forces.

In the first years of the invasion, Kirkuk remained relatively peaceful. growing insecurity was driven by escalating local tensions, as well as by political leaders and factions amid a growing stalemate between Baghdad and Erbil.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

24

Kurdish leaders had already made the status of Kirkuk city a high-profile political symbol of Kurdish autonomy -- opposed by Arab and Turkoman politicians aligned to Baghdad. In the new context, political rivalries between Turkomen and Arabs on one hand and Kurds on the other increased. Tensions escalated following the adoption of the new Iraqi constitution in 2005, which includes provision for Kirkuk and other disputed territories to hold referendums for independence.; in the course of the 2005 Provincial Council elections (in which KDP/PUK list collected 59% and absolute majority); and following the Dec 2005 parliamentary elections, following which Nuri al-Maliki (a Shiite) became Prime Minister. In Nov 2006, Arab

13 and Turkomen members of the Provincial Council withdrew, claiming that they were

excluded from decision-making and governance. At the same time, lingering animosities between the KDP and PUK (dominant) in Kirkuk’s governmental institutions led to poor governance and service delivery.

Starting in 2003 – through 2013 – the authorities in Kirkuk embarked on a policy to encourage Arabs (particularly those of recent arrival) to leave the province and to bring back Kurds (in line with the Takrid/Kurdicisation policy of the KRG). This was not always done with peaceful measures,

14 although

there were incentives offered for Arabs to leave. In 2003-2005, an estimated 100 000 Kurds settled in Kirkuk city, and once again, Kirkuk was fast becoming a Kurdish-majority city. While their original homes and villages were largely destroyed (or occupied), many Kurdish returnees squatted in Kirkuk city. These demographic changes brought with them also disputes over the ownership of land which is the second largest economy factor after the oil. Additionally, Kirkuk residents increasingly struggled with inadequate security, poor/unequal services, and other concerns that exacerbate ethnic tensions.

Insurgency groups formed to oppose the occupation, the local government and the new Iraqi government, and armed groups proliferated: the Peshmerga, Al-Qaida in Iraq (Sunni), Sahwa forces (Sunni), Al-Asayesh (Kurdish), groups allied to Muqtada al-Sadr (Shiite), etc. The situation was increasingly exploited by extremists; e.g. in 2005, Al-Qaida started targeting civilians in acts of terrorism, and periodic insurgent attacks targeted oil infrastructure, disrupting the flow of oil along the Kirkuk-Ceyhan export line. Jihadis from east and west of the province (e.g. Ansar al-Islam and Ansar al-Sunnah) were also targeting the city, supported by local Sunni groups.

Across Iraq, fierce Sunni vs. Shiite sectarian violence erupted in 2006–2007 following the bombing (22 Feb 2006) of the Al-Askari Shrine in Samarra (one of the holiest sites in Shia Islam). In Kirkuk, this translated as Arab/Turkoman (Shiite and Sunni) vs. Kurdish conflict and violence; open hostilities broke between Turkomen and Kurds. Between Dec 2005 and July 2006, violent incidents in Kirkuk city increased by 76%, ending the city's status as a relatively safe area. Attacks on KDP and PUK headquarters, sniping, improvised explosive devices, assassination attacks on local police and community leaders, and attacks on politicians proliferated. In Aug-Oct 2006 alone Kirkuk city was hit by 20 suicide bombs and 63 roadside bombs.

Violence, direct threats and generalised fear triggered a spike in internal displacement across Iraq. Military operations and fighting also contributed to displacement (especially as housing was destroyed), as did inter-tribal clashes. Insurgents and militia used religious affiliation as a justification to force hundreds of thousands of people from their homes. Criminals capitalised on an increased lack of security to abduct, loot, and attack individuals, further contributing to an environment of violence and displacement. In general, IDPs moved from religiously and ethnically mixed communities to homogeneous communities – within the same city, as well as across provincial borders. Kirkuk accepted scores of IDPs – mainly from Sunni-majority areas. At the same time, thousands of Arabs and Turkomen fled Kirkuk.

15

After the withdrawal of US troops from Iraq in Dec 2011, sectarian violence escalated again, as Sunni and anti-Kurdish groups stepped up attacks aimed to undermine confidence in the government. In 2012, along with Baghdad and Samarra, Kirkuk saw some of the worst violence in Iraq. At the same time, poverty increased significantly between 2007 and 2012,

16 feeding social unrest and radicalisation. Radicalisation was additionally

galvanised in the context of the Syrian Civil War, with which the insurgency eventually merged in 2014.

By 2014, Kirkuk was a tinderbox of sectarian conflict. The decade of growing violence, extremism and insecurity after 2003 was increasingly seen by parts of the population as counterpoint to ISIL’s promise of peace and order. Thus, it effectively paved the way for the take over of Kirkuk areas by ISIL in 2014.

13 Arab members returned to the council in Dec 2007 after a new power-sharing deal was agreed. 14 There are allegations of murder, kidnapping and physical intimidation used by Kurdish authorities to force minorities to leave the governorate. 15 IOM reports that in 2006, Kirkuk hosted 1002 IDP families (6012 people), and 580 families (2500 people) from Kirkuk displaced to other provinces. Cf. IOM, “Iraq Displacement 2006 Year in Review”: https://bit.ly/2wkINe0. Kirkuk Governorate (2016), Plan to Manage the IDP Crisis suggests that in 2006 Kirkuk province accepted at least 45 000 IDPs (as registered by MoMD), including a vast majority from Diyala. 16 GSDRC (28 Aug 2015), Poverty Eradication in Iraq (GSDRC Helpdesk Research Report 1259): https://bit.ly/2IjekBX.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

25

Occupation by ISIL 2014–2017

Kirkuk is one the most severely affected provinces of Iraq from the ISIL conflict.

ISIL unleashed a campaign of death and destruction in Iraq in Jan 2014, starting with Anbar governorate. On 10 June ISIL invaded Kirkuk province. On 12 June 2014, the Iraqi Army fled Kirkuk city; Peshmerga fighters moved in and prevented Kirkuk city from being taken by ISIL. The Peshmerga then moved deep into disputed territories, which they defended against the ISIL militants. By July 2014, ISIL controlled ca. 45% of Kirkuk province – mainly Sunni Arab areas – including the entire Hawiga Qadha (see Figure 6).

Thereafter, the Peshmerga increased their influence in Kirkuk province, taking control over the oil installations and supporting the provincial authorities. In March 2015, the Peshmerga started a campaign to take back from ISIL villages south of Kirkuk. Security levels in Kirkuk city and surrounding areas improved. Nevertheless, fighting continued across the province. In ISIL-free areas, ISIL attacks continued, even in the city centre of Kirkuk. E.g. in Dec 2015, Kurdish forces attacked ISIL positions around Kirkuk, backed by heavy air strikes from a US-led coalition; the Peshmerga also advanced on several fronts to the west of Kirkuk. The last large-scale attack on Kirkuk was on 21-24 Oct 2016, when more than 200 ISIL fighters attacked Kirkuk city and a suicide bomb exploded at Dibis power plant – to divert Iraqi military resources during the Battle of Mosul.

On 21 Sept 2017, the Iraqi army with the support from Iran-backed Shiite paramilitary groups (PMFs) and the international coalition launched the final Kirkuk liberation offensive. Following the victory in Hawiga, the governorate was officially declared liberated from ISIL on 10 Oct 2017. Disputed areas in Kirkuk saw additional military activity on 15–20 Oct 2017, linked to the Baghdad-Erbil standoff, whereby Kurdish forces withdrew from Kirkuk and federal authority was reasserted over disputed areas.

Figure 6 ISIL control (2014–2016) and IDP formal settlements (Dec 2017) in Kirkuk province

The context of ISIL had a major effect on economic life in the province. In captured areas, ISIL fighters looted and crushed enterprises; subjected business owners and farmers to excessive taxation; monopolised sales; took control of agricultural production and equipment; forced farmers to sell their products at lower rates; confiscated ready produce; etc. At the same time, food shares allocated for poor families stopped, while the cost of commodities and basic services soared. Across the province, the economy was disrupted. E.g. 2015-2016 saw a prolonged oil disruption, when a quarter of Kurdish oil was reinjected back into the ground for months – costing the region ca. USD 1 billion in lost revenues. Lack of electricity and major fuel stalled activity across sectors. Poverty and unemployment levels soared – exacerbated by food shortage and loss of livelihoods, especially in rural areas.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

26

Although complete damage of infrastructure is rarely reported, inefficient functioning/condition of roads, sewerage and tap water network affects between one fourth and one third of the population. Many properties (and infrastructures) were damaged by military campaigns and armed group activities. Buildings such as schools and hospitals became focus of attacks and heavy fighting. Additionally, on retreat, ISIL bombed anything supporting the local economy – including economic facilities, bridges, service projects, private shops, etc., as well as housing. Physical damage to the built environment prevents families and communities from recreating livelihoods, and it also impedes effective and inclusive service provision post-ISIL.

Also, ethnic divisions were exacerbated in the context of ISIL. In captured areas, ISIL’s violence systematically targeted religious and ethnic minorities. ISIL also rampaged through numerous historic, archaeological and religious sites, including Islamic mosques and shrines. In secured areas, there were allegations that Kurdish and Shi’a PFM (Turkoman) forces forcibly displaced resident Sunni Arabs in areas under their control. Arab expulsions were allegedly often accompanied by mass property destruction and the demolition of Arab villages. Attacks on Arab communities were also be motivated by revenge for attacks on the Peshmerga: e.g. the 21 Oct 2016 attack in Kirkuk city triggered widespread retaliation by the Kurdish forces against Arabs across the governorate.

17

Additionally, on 25 Sept 2017, a referendum was held to determine whether Kirkuk province would join the KRG or remain tied to Baghdad. The result of referendum (to join the KRG) was not recognised by Baghdad. Prior to the referendum, the ethnic composition of the province increasingly became a top sensitive issue. Among the Kurdish population, the sentiment increased that Arabs settled in the province in the last 50 years should be returned back to their original places and not given the right to vote (although in some cases they are third or fourth generation living in Kirkuk). Also, open hostilities broke between Turkomen (Sunni and Shi’ite) and Kurds – e.g. Tooz Khormato city became violently split between Kurds and Shi’ite Turkomen, with Kurdish Peshmerga forces controlling a Kurdish half, and Shi’ia PMFs controlling the Turkomen neighbourhoods.

Driven by violence and ethnic tensions, across Iraq, internal displacement increased in scale, severity and impact in 2014-2017. In early 2014, Kirkuk (mainly Kirkuk QC) saw an initial wave of ca. 85 000 IDPs (mainly from Anbar).

18 After ISIL captured Mosul and Tikrit on 10-11 June 2014, a new wave of 116 000 IDPs arrived (mainly to

Kirkuk and Hawiga). By end-2014, Kirkuk hosted more than 300 000 IDPs, including 14% from Kirkuk.19

Displacement from Hawiga increased following the beginning of the Mosul military operations in Oct 2016. By the liberation of the province in Oct 2017, IDPs in Kirkuk were ca. 260 000, including 50% from Kirkuk; in total, more than 20% of the population of the province were displaced, almost half of whom to other governorates.

20

Overall, since 2014, Kirkuk has hosted the second highest number of IDPs from other Iraqi provinces after the KRI. By IOM data, IDPs in Kirkuk reached ca. 410 000 IDPs at the height of displacement, and ca. 380 000 on average in 2015 and 2016.

21 By MoMD data, IDPs in Kirkuk reached in early 2016 more than 600 000 (ca.

121 200 families).22

The massive scale of displacement into Kirkuk has driven a major humanitarian crisis, and it has inter alia lead to increased strain on host communities; heightened competition for limited resources; deterioration in the sectors of health, education, water and sanitation; and an increase in vulnerability among women and children.

In the aftermath of its liberation from ISIL, a return process has started. But insecurity in Kirkuk province continues. Following 16 Oct 2017, there have been: reports of flight of Kurds; allegations of violence toward Kurds and forced displacement of Kurds by Shiite PFMs; reports of looting and destruction of property/housing, mainly in Kurdish neighbourhoods (vehemently so in Tooz Khormato); attacks on and assassinations of Turkoman politicians and community leaders (both who supported Kurdish independence and opposed it); etc. In late 2017, Kirkuk has witnessed an increase in acts of violence and armed conflict targeting civilians, security forces and officials. ISIL strikes continue, and there are suspicions of renewed ISIL cells in Hawiga. Distrust of government and officials is high among the Kurdish populations. Fears of retaliation are very high – among the Kurdish as well as the Sunni population. At the same time, guns are sold on the street corner, to whoever wans the, and the incidence of arming is wide-spread.

23

17 New York Times (22 Oct 2016), “ISIS Fighters in Iraq Attack Kirkuk, Diverting Attention from Mosul”: https://nyti.ms/2FSwKnQ. 18 IOM (June 2015), Kirkuk Governorate Profile. 19 http://iraqdtm.iom.int/DtmReports.aspx 20 IOM, Displacement Tracking Matrix data of 15 Oct 2017: http://iraqdtm.iom.int/IDPsML.aspx. 21 IOM, Displacement Tracking Matrix: http://iraqdtm.iom.int/IDPsML.aspx. 22 Displaced people registered with MoMD Kirkuk office (121 200 families). Kirkuk Governorate (2016), Plan to Manage the IDP Crisis (ظة خطة محافوك رك ين أزمة ادارةل ك نازح كومه – ال ح ية ال ل مح ي ال ظة ف وك محاف رك عاون ك ت ال شروع مع ب ف م كات .The Plan responds to IDP pressure of 125 000 families .(ت23 In 2014, the fleeing Iraqi Army left behind a stockpile of weapons that are now openly sold to civilians.

LADP in Iraq – Kirkuk PRP

27

The forced demographic shifts of the past half century, combined with the uncertainty of the status of the province have created a very unstable and volatile situation in Kirkuk province. Kirkuk’s diverse composition, coupled with entrenched presence of Sunni extremist groups, Kurdish-Turkomen violence and inter-Kurdish conflicts, has been a hotbed for ethnic and sectarian conflict. Conflict has escalated in the context of ISIL, while the referendum for independence has exposed divisions in the community that need to be addressed.

Post-ISIL, religious, ethnic and social divisions are exacerbated. Currently there are tensions between Kurds on one side, and Arabs and Turkomen (who govern the province) on the other side. Also, Kurdish–Turkomen and Sunni–Shiite tensions are very much felt: e.g. Hawiga Qadha (Sunni Arab majority) is divided over which tribes supported and which fought ISIL. Tensions could easily ignite retributive acts and further violence.