PRoBIotIcs – HeALtH BeNeFIts, cLAssIFIcAtIoN, QUALItY...

Transcript of PRoBIotIcs – HeALtH BeNeFIts, cLAssIFIcAtIoN, QUALItY...

22

IntroductionWith the growing interest in self-care and inte-

grative medicine coupled with our health-embracing increasing population, recognition of the link be-tween diet and health has never been stronger. As a result, the market for functional foods, or foods that promote health beyond providing basic nutrition, is flourishing. Within the functional foods movement is the small but rapidly expanding arena of probiotics [1]. That’s why in the last years an increased interest is observed not only within the consumers and and the food industry, but also within the scientific com-munity. The scientists aim to understand the interac-tions between the gut and intestinal microbiota and between resident and transient microbiota that define a new arena in physiology, which would shed light on the „cross-talk“ between humans and microbes [2]. The increased interest and usage of probiotic prod-ucts prompted us to summarize the information about their health benefits, classification, quality assurance criteria and methods of analysis and quality control.

Definition of probiotic and related terms

ProbioticThe term probiotic, meaning “for life,” is derived

from the Greek language. It was first used by Lilly and Stillwell [3] in 1965 to describe “substances se-creted by one microorganism which stimulates the

growth of another” and thus was contrasted with the term antibiotic. It may be because of this posi-tive and general claim of definition that the term probiotic was subsequently applied to other subjects and gained a more general meaning. In 1971 Sper-ti [4] applied the term to tissue extracts that stimu-late microbial growth. Parker [5] was the first to use the term probiotic in the sense that it is used today. He defined probiotics as “organisms and substances which contribute to intestinal microbial balance.” In our days we accepted the definition of World Health Organization (WHO). According to WHO, probiotics are “live micro-organisms which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host” [6].

PrebioticThe term prebiotic was introduced by Gibson

and Roberfroid [7] who exchanged “pro” for “pre,” which means “before” or “for.” They defined prebi-otics as “a non-digestible food ingredient that bene-ficially affects the host by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of one or a limited number of bacteria in the colon”. Modification by prebiotics of the composition of the colonic microflora leads to the predominance of a few of the potentially health-pro-moting bacteria, especially, but not exclusively, lac-tobacilli and bifidobacteria [7]. The prebiotics most commonly used are oligosaccharides whose degree

Review Articles

PRoBIotIcs – HeALtH BeNeFIts, cLAssIFIcAtIoN, QUALItY AssURANce AND QUALItY coNtRoL – ReVIeW

M. Georgieva, L. Andonova, L. Peikova, Al. Zlatkov

Department of Pharmaceutical chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University – Sofia, Bulgaria

Abstract. Unlike antibiotics which mean “to destroy life,” probiotics literally means “life giv-ing”. Probiotics are friendly bacteria. When consumed, probiotics confer beneficial effects to the host. It influences the homeostasis and controls various gastrointestinal disorders. Probiotic ingestion can be a preventive approach for maintaining the balance of the intestinal microbial flora. Currently, probiotic foods, dietary supplements and beverages are accepted globally due to development in the relationship between nutrition and health, their promising health benefits and negligible side effects. Therefore, the need has arisen for more effective quality control methods aiming at detecting adulteration. Deciding which supplements you should buy is a tricky business. There are thousands of options to choose from, but very little reliable information to help you weed out the best from the rest.

Key words: probiotics, nutritional supplement, quality control

PHARMACIA, vol. 61, No. 4/2014 23Probiotics – health benefits, classification, quality assurance...

of polymerization varies between 2 and 20 mono-mers e.g., fructo- oligosaccharides (FOSs), inulin, galacto-oligosaccharides (GOSs) and xylo-oligosac-charides (XOSs) [8].

SynbioticThe term synbiotic is used when a product con-

tains both probiotics and prebiotics. Because the word alludes to synergism, this term should be re-served for products in which the prebiotic compound selectively favors the probiotic compound. The ex-pectation is that the prebiotics will enhance the sur-vival and growth of the probiotics [9, 10].

taxonomy of probioticsThe taxonomy of probiotic lactic acid bacteria

was formed according to morphological, biochem-ical and physiological characteristics with molecu-lar-based phenotypic and genomic techniques. The most studied are genera Lactobacillus, Bifidobacte-rium and Enterococcus (table 1). In the genus Lac-tobacillus the following species of importance as probiotics were investigated: L. acidophilus group, L. casei group and L. reuteri/L. fermentum group. Bifidobacterium spp. (B. animalis) strains have been reported to be used for production of fermented dairy and recently of probiotic products. From the genus Enterococcus, probiotic Ec. faecium strains were investigated with regard to the vanA-mediated resis-tance against glycopeptides [11-13].

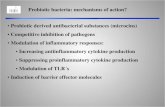

Health benefits of probiotics Microbiota balance is the oldest proposed probi-

otic benefit. Metchnikoff defined it as ‘seeding’ of the intestinal tract with harmless lactic acid bacteria (LAB) that suppress the growth of harmful proteolyt-ic bacteria. Nowadays such a benefit is usually inter-preted as an increase in lactobacilli and/or bifidobac-teria and a decrease in potentially pathogenic bacteria

Lactobacillus species Bifidobacterium species othersL. acidophilus B. bifidum Bacillus cereus

L. casei (rhamnosus) B. longum Escherichia coliL. reuteri B. breve Saccharomyces cerevisiae

L. bulgaricus B. infantis Enterococcus faecalisL. plantarum B. lactis Streptococcus thermophilusL. johnsonii B. adolescentis

L. lactis

[15]. One of the best studied examples of how mi-crobiota dysbiosis affects health is seen in Crohn’s disease (CD) [16].

Since the early studies of mucosal immunity in the 1970s, a lot of progress has been made in un-derstanding the mode of interaction between the gut microbiota and the immune system. The ability of exogenous probiotics to improve clinical outcomes through modulation of the immune response has been demonstrated in subjects with chronic and acute dis-eases [17-21] Immune stimulatory effects have been established in generally healthy population as well [22-28]. A few studies have shown a link between activated immune markers and improved resistance to infections [15].

The gastro-intestinal discomfort, including diar-rhea in children and adults, antibiotic-associated diar-rhea, constipation and irritable bowel syndrome, can be influenced using probiotic products [29-39]. Some studies report successful treatment of colicky symp-toms, frequent in newborn infants, was achieved us-ing probiotic [40].

Candida species is the most common cause of vag-inal infection, with frequent recurrence and chronic infection, so probiotics may be useful for treatment [41-44]. Studies conducted by Hilton et al. showed a significant reduction in vaginal colonization with Candida species after the oral administration and a 7-day course of vaginal suppositories [45, 46].

Other examples of health benefits attributed to probiotics range are prevention of tumours in mice [47, 48], treatment of food allergy including atopic eczema [49], delaying the effects of aging in humans [50] and modulating blood lipid levels [51].

To exert health benefits probiotics must be able to survive transition through the low pH in the stomach and colonize the colon apart from the high concentra-tions of bile acids [52].

Table 1. Microorganisms used as probiotic agents [14]

24 PHARMACIA, vol. 61, No. 4/2014 M. Georgieva, L. Andonova, L. Peikova, Al. Zlatkov

safety of probioticsThe application of probiotic microorganisms in

foodstuffs requires a thorough safety assessment [53]. The safety assessment is available in some guide-lines [54-57]. Data requirements to assess the safe-ty of probiotics can vary depending on the bacterial species of interest, the intended application/use and/or the target populations. Parameters such as taxon-omy and identification, phenotypic characterization, history of food use, and human exposure, and so on, are generally considered important. If no history of safe use can be demonstrated, extensive preclinical studies, including standard 90-day toxicity studies as defined in OECD Testing Guideline 408, should also be considered. Clinical studies should include param-eters to demonstrate safety in use or tolerability in the target population(s) [53].

criteria for functional quality assurance and an-alytical approaches for characterization and vali-dation of probiotic products

The criteria currently used to select probiot-ics define the optimal quality control of probiotic strains in industrial practice. Important quality-con-trol properties that must be constantly controlled and optimized are the following: adhesive proper-ties; bile and acid stability; viability and survival throughout the manufacturing process; effects on carbohydrate, protein, and fat utilization; and, espe-cially, colonization properties and immunogenicity. Most of these properties are related to the physio-logic properties of the strain, but long-term industri-al processing and storage conditions may influence probiotic properties. Thus, in addition to technolog-ic properties, functional properties should be con-sidered in quality-control measures [58].

The methods available for detection, enumeration and identification of microorganisms could be also applied to probiotic microorganisms.

Molecular methodsIdentification of probiotic species, including their

differentiation in different strains by culture-depen-dent or culture-independent techniques, the study of microbial community composition, and assess-ment of its different populations and interactions in food products are some of the main achievements of molecular techniques. With the use of molecular methods, the ability to detect and to identify food microbes, including probiotic bacteria, has made tremendous advances in recent years, especially af-ter the introduction of PCR (polymerase chain reac-

tion) in the 1980s. Several detection techniques have been developed based on PCR, namely denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE), real-time PCR (qPCR), terminal restriction fragment length poly-morphism (T-RFLP), random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) [8, 59].

In Figure 1 is presented the approach of the mo-lecular analysis.

To rapidly detect multiple microorganisms in a single reaction, simultaneous amplification of more than one locus is required; a methodology referred to as multiplex PCR (MPCR) in which several specific primer sets are combined into a single PCR assay. Hence, MPCR is undoubtedly useful to rapidly iden-tify several isolates and, with respect to DGGE, it en-ables the selection of various species and represents the fastest culture-independent approach for strain-specific detection in complex matrices. At a certain level, MPCR might be considered a quantitative (or better yet, a semi-quantitative) technique, since, once it has been established, the detection limit can be re-trieved and used as the minimal microbial concentra-tion detectable [60].

Non-molecular methodsThe non-molecular approach to detect, to enu-

merate and to identify probiotic strains includes those methods considered conventional, based on the growth of the microorganism in culture media, and those not requiring this step (Fig. 1). The basis of the conventional methods relies on standard procedures encompassing isolation, counting and identification of the probiotic strains at the genus and species levels based on cell ability to reproduce and to form colo-nies on selective/differential agar media plates [61].

Alternative methodologies have been applied to quantify probiotic bacteria in a more accurate way able to reduce the underestimation of viable bacte-ria obtained by plate-count methods. Fluorescence methods have been applied in bacterial viability stud-ies [62]; Fluorescence methods are able to detect and to differentiate between viable, injured, stressed and dead bacterial cells through fluorescent dyes, which, in turn, can be detected by fluorescence microscopy, fluorometry, flow cytometry, or fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

An alternative method is Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy that has been applied for detec-tion, discrimination, identification and classification of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) and probiotics and also pro-vides information about cell metabolism from cultures and foods. FT-IR is able to discriminate viable, injured

PHARMACIA, vol. 61, No. 4/2014 25Probiotics – health benefits, classification, quality assurance...

and dead bacteria and is used in the analysis of struc-tural components of bacteria. FT-IR is a relatively fast, simple, sensitive technique, requiring very little sam-ple, and the biological cell remains intact during anal-ysis. It is possible to make qualitative and quantitative analysis and the sample can be in the form of liquid, gas, powder, solid, or film. If the sample is complex, then it can produce overlapping spectra, and so previ-ous separation or purification steps may be needed or may require standardization, rigorous data collection, and expertise in the chemometric analyses of spectra [63, 64]. In Figure 2 is presented the approach of the non molecular analysis.

Applications & Dosage FormsAs discussed above the most common species of

probiotics used in foods are Lactobacilli and Bifido-bacteria. The same Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria

are used in both foods and food supplements. In ad-dition some Enterococcus species, Bacillus species, Escherichia coli, Saccharomyces boulardii (a yeast), and other species are used in food supplements [65].

A wider variety of probiotic strains, either sin-gly or in combination, is used in supplements rath-er than in foods. Several product formulations ex-ist, like: hard gelatin or vegetable capsules, tablets with or without enterocoating (e.g., those that dis-solve in neutral conditions), chewable tablets, and sachets. Supplement formulations may also con-tain other active components, including vitamins and prebiotics. Probiotics are also found as sold in oil suspensions, which makes them easy to admin-ister to infants. Furthermore, probiotics are com-bined with oral rehydration salts for the treatment of acute diarrhea, whereas some of these products are registered as drugs [65].

Fig. 1. Molecular approach for identification of probiotic species.

26 PHARMACIA, vol. 61, No. 4/2014 M. Georgieva, L. Andonova, L. Peikova, Al. Zlatkov

Probiotics are worldwide available, as supple-ments consisting of freeze-dried bacteria, second-ly in fermented foods such as yoghurts, and thirdly in products aimed at enhancing specific aspects of ‚health‘, such as bowel cleansers. In some countries probiotics are also sold as remedies for specific med-ical conditions such as diarrhea [66].

Not surprisingly, in some late experiments of pro-biotic products have been found that about 70 to 80 percent of the samples tested do not measure up to their label claims. In these experiments is also es-tablished, that about half of the tested samples did not have even 10 percent of the claimed number of live microorganisms as listed on their labels. In some products tested have even been determined a pres-ence of undesirable microorganisms not listed on the label [67]. Keeping this in mind, in order to obtain well produced product is essential to follow the fol-lowing steps, when producing: eliminating oxygen from and including nitrogen in probiotic supplement bottles to enhance the stability of probiotics; probi-otic supplements should be refrigerated to maintain their potency and viability; any new bacterial culture

that has no history of prior safe use in humans should be subject to toxicological studies prior to incorpora-tion in any probiotic supplement and also selecting acid resistant strains of is the key to the success of the probiotic supplement [67].

In order to assure the qualities of the probiotic product, it is important to know that the supplement is tested for viable microorganisms at the time of manufacturing and at the expiration date. This quality control procedure is important to the manufacturer as well as the consumer. The viable cells are guaranteed as CFU (colony forming units) per gram at the time of probiotic supplement packaging. If the supplement does not list viable cells, or does not list the amount in CFU form, it may not be a quality supplement. Consumption of probiotic supplements with two to five billion CFU per day is necessary to have any chance of offering significant beneficial effects [67].

In conclusion in order for a consumer to be sure of the quality and safety of the probiotic product, the following tips should be considered:

• All probiotic supplements lose their potency when they exposed to oxygen, moisture, and

Fig. 2. Non molecular analysis approach for identification of probiotic species

PHARMACIA, vol. 61, No. 4/2014 27Probiotics – health benefits, classification, quality assurance...

heat. The probiotic strain must also be prov-en to survive stomach acids in live human subjects. The bacteria strain should be able to adhere to the intestinal walls and proliferate.

• Many probiotic combinations lack research. No studies exist showing their compatiblity and experts agree too many different bacteria may be antagonistic to each other.

• The selection of bacteria for incorporation in probiotic supplements that are on the federal GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) list is imperative for the products safety.

• Fortification of probiotics with prebiotic fructooligosaccharides (FOS) enhances the value of the probiotic supplement by provid-ing a nutrient that selectively enhances the growth of friendly cultures [68].

Regulations and quality control of probiotic con-taining dietary supplements

Regulations in only a few countries have made it possible to get an official approval of health claims—for example, in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and The Netherlands. With the acceptance of the new regulation from the European Union, the use of un-authorized claims and promises will be impossible. This may also lead to a swift move from general claims about health benefits and intestinal health to more-precise claims and products targeted to more specific areas of health [65].

When manufacturing probiotic products, high quality standards and processes are imperative. This ensures that the product is manufactured to the high-est standard to result in a product that not only meets label specification but is also effective and safe to use. In addition to this, the product should be tested by an independent, fully accredited laboratory (lab) which has the expertise to enumerate (count) the pro-biotic strains. Quality assurance should rank highly on the priority list for each company and full trace-ability should be as standard [68].

In absence of any rigid or well-defined regulatory norms, manufacturers, consumers as well as the regula-tory authorities are facing problems. It is obvious, that due to discrepancies in the health claims of probiotics and adoption of different regulations and methods of analysis by different countries around the world, estab-lishment and enforcement of a globally accepted regu-lation and a quality assurance program for probiotics is essential to obtain consistent product [69].

Regulatory and labeling issues related to probi-otics are complicated because they differ for each

country [70] and status of probiotics as a compo-nent in food is currently not established on an inter-national basis [71]. Problem of labeling still exists due to adoption of different regulations and meth-ods of analysis by different countries around the world [72]. Probiotic foods have not been properly identified, documented, manufactured under Good Manufacturing Practices or proven clinically, which lead consumers in difficulties to decide and confirm whether they are adopting the reliable product [73]. Worldwide regulations related to probiotic foods are incoherent and assay methods are inconsistent, which resulted in existence of following problems related to labeling [72].

So to be practically useful to consumers, labels should have the following information: (a) notifica-tion of the presence of live bacteria; (b) the precise nature of the bacteria; (c) numbers of each species, in units comprehensible to consumers and microbi-ologically accurate; (d) the minimum amount neces-sary to bring about any claimed health effect, either in terms of numbers of bacteria or of servings; and (e) the accurate content at the time of purchase, not just at some stage during manufacture [66].

conclusionFrom the discussion presented in this review is

clear, that a full traceability programme should be run and all raw material and finished product batches should be a subject to quality control analysis to en-sure the best possible quality throughout the produc-tion cycle and for the whole shelf life of the product. It is also obvious, that the manufacturing of probiotic products of high quality standards and processes is imperative and adoption of different regulations and methods of analysis by different countries around the world is essential to obtain consistent safe products with high quality.

References:1. K h a n SH, Ansari FA. Probiotics-the friendly

bacteria with market potential in global market. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2007; 20(1): 76-82.

2. R i j k e r s GT, Bengmark S, Enck P, Haller D, Herz U, Kalliomaki M, Kudo S, Lenoir-Wi-jnkoop I, Mercenier A, Myllyluoma E, Rabot S, Rafter J, Szajewska H, Watzl B, Wells J, Wolv-ers D, Antoine JM. Guidance for substantiating the evidence for beneficial effects of probiotics: current status and recommendations for future research. J Nutr. 2010; 140(3): 671-6.

28 PHARMACIA, vol. 61, No. 4/2014 M. Georgieva, L. Andonova, L. Peikova, Al. Zlatkov

3. L i l l y DM, Stillwell RH. Probiotics. Growth promoting factors produced by micro-organisms. Science 1965; 147: 747–8.

4. S p e r t i GS. Probiotics. West Po int, CT: Avi Publishing Co, 1971.

5. P a r k e r RB. Probiotics, the other half of the an-tibiotic story. Anim Nutr Health 1974; 29: 4–8.

6. J o i n t FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Eval-uation of Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food Including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria. Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food including Pow-der Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria. 2001 Ref Type: Report.

7. G i b s o n GR, Roberfroid MB. Dietary modula-tion of the human colonic microbiota. Introduc-ing the concept of prebiotics. J Nutr 1995; 125: 1401–12.

8. R o d r i g u e s D, Rocha-Santos TAP, Freitas AC, Gomes AMP, Duarte AC. Analytical strate-gies for characterization and validation of func-tional dairy foods. Trends in Analytical Chemis-try 2012; 41: 27-45.

9. S c h r e z e n m e i r J, de Vrese M. Probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics-approaching a defini-tion. Am J Clin Nutr 2001; 73(suppl): 361S–4S.

10. A d e b o l a OO, Corcoran O, Morgan WA. Syn-biotics: the impact of potential prebiotics inulin, lactulose and lactobionic acid on the survival and growth of lactobacilli probiotics. Journal of func-tional foods 2014; 10: 75 –84.

11. K l e i n G, Pack A, Bonaparte C, Reuter G. Tax-onomy and physiology of probiotic lactic acid bacteria. International Journal of Food Microbi-ology 1998; 26: 103–125.

12. N a i d u AS, Bidlack WR, Clemens RA. Probi-otic spectra of lactic acid bacteria (LAB). Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 1999; 39: 13–126.

13. K l a e n h a m m e r TR, Kullen MJ. Selection and design of probiotics. Int J Food Microbiol 1999; 50: 45–57.

14. A l v a r e z - O l m o s MI, Oberhelman RA. Pro-biotic Agents and Infectious Diseases: A Modern Perspective on a Traditional Therapy. Clinical In-fectious Diseases 2001; 32: 1567–76.

15. D e V r e s e M, Winkler P, Rautenberg P, Harder T, Noah C, Laue C, Ott S, Hampe J, Schreiber S, Heller K, Schrezenmeir J. Probiotic bacteria re-duced duration and severity but not the incidence

of common cold episodes in a double blind, randomized, controlled trial. Vaccine 2006; 24: 6670-6674.

16. M a n i c h a n h C, Rigottier-Gois L, Bonnaud E, Gloux K, Pelletier E, Frangeul L, Nalin R, Jar-rin C, Chardon P, Marteau P, Roca J, Dore J. Re-duced diversity of faecal microbiota in Crohn’s disease revealed by a metagenomic approach. Gut 2006; 55: 205-211.

17. D u e r k o p BA, Vaishnava S, Hooper LV: Im-mune responses to the microbiota at the intestinal mucosal surface. Immunity 2009; 31: 368-376.

18. G i o n c h e t t i P, Rizzello F, Helwig U, Venturi A, Lammers KM, Brigidi P, Vitali B, Poggioli G, Miglioli M, Campieri M. Prophylaxis of pouch-itis onset with probiotic therapy: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2003; 124: 1202-1209.

19. G i o n c h e t t i P, Rizzello F, Morselli C, Poggi-oli G, Tambasco R, Calabrese C, Brigidi P, Vitali B, Straforini G, Campieri M: High-dose probiot-ics for the treatment of active pouchitis. Dis Co-lon Rectum 2007; 50: 2075-2082.

20. M i e l e E, Pascarella F, Giannetti E, Quaglietta L, Baldassano RN, Staiano A: Effect of a probi-otic preparation (VSL#3) on induction and main-tenance of remission in children with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 437-443.

21. P r o n i o A, Montesani C, Butteroni C, Vecchi-one S, Mumolo G, Vestri A, Vitolo D, Boirivant M. Probiotic administration in patients with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis is associated with expansion of mucosal regulatory cells. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2008; 14: 662-668.

22. L i n k - A m s t e r H, Rochat F, Saudan KY, Mi-gnot O, Aeschlimann JM: Modulation of a spe-cific humoral immune response and changes in intestinal flora mediated through fermented milk intake. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 1994; 10: 55-63.

23. O l i v a r e s M, Diaz-Ropero MP, Sierra S, Lara-Villoslada F, Fonolla J, Navas M, Rodri-guez JM, Xaus J: Oral intake of Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 enhances the effects of influenza vaccination. Nutrition 2007; 23: 254-260.

24. A r u n a c h a l a m K, Gill HS, Chandra RK: En-hancement of natural immune function by dietary consumption of Bifidobacterium lactis (HN019). Eur J Clin Nutr 2000; 54: 263-267.

PHARMACIA, vol. 61, No. 4/2014 29Probiotics – health benefits, classification, quality assurance...

25. D o n n e t - H u g h e s A, Rochat F, Serrant P, Aeschlimann JM, Schiffrin EJ: Modulation of nonspecific mechanisms of defense by lactic acid bacteria: effective dose. J Dairy Sci 1999; 82: 863-869.

26. S c h i f f r i n EJ, Brassart D, Servin AL, Rochat F, Donnet-Hughes A: Immune modulation of blood leukocytes in humans by lactic acid bac-teria: criteria for strain selection. Am J Clin Nutr 1997; 66: 515S-520S.

27. S p i e g e l BM: The burden of IBS: looking at metrics. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2009; 11: 265-269.

28. O ’ M a h o n y L, McCarthy J, Kelly P, Hurley G, Luo F, Chen K, O’Sullivan GC, Kiely B, Col-lins JK, Shanahan F, Quigley EM: Lactobacillus and bifidobacterium in irritable bowel syndrome: symptom responses and relationship to cytokine profiles. Gastroenterology 2005; 128: 541-551.

29. S h o r n i k o v a AV, Casas IA, Isolauri E, Myk-känen H, Vesikari T. Lactobacillus reuteri as a therapeutic agent in acute diarrhea in young children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1997; 24: 399–404.

30. I s o l a u r i E, Juntunen M, Rautanen T, Sil-lanaukee P, Koivula T. A human Lactobacillus strain (Lactobacillus casei sp strain GG) pro-motes recovery from acute diarrhea in children. Pediatrics 1991; 88: 90–7.

31. G u a r i n o A, Canani RB, Spagnuolo MI. Oral bacteria therapy reduces duration of symptoms and of viral excretion in children with mild Di-arrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1997; 25: 516–9.

32. S a a v e d r a J. Probiotics and infectious diar-rhea. Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95(Suppl 1): S16–S18.

33. G u a n d a l i n i S, Pensabene L, Zikri MA, Dias JA, Casali LG, Hoekstra H, Kolacek S, Massar K, Micetic-Turk D, Papadopoulou A, de Sousa JS, Sandhu B, Szajewska H, Weizman Z. Lac-tobacillus GG administered in oral rehydration solution to children with acute diarrhea: a mul-ticenter European study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000; 30: 54–60.

34. P e a r c e JL, Hamilton JR. Controlled trial of orally administered lactobacilli in acute infantile diarrhea. J Pediatr 1974; 84: 261–2.

35. M c F a r l a n d L, Surawicz C, Greenberg R, et al. Prevention of beta-lactam–associated diarrhea

by Saccharomyces boulardii compared with pla-cebo. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90: 439–48.

36. C o l o m b e l JF, Cortot A, Newt C, Romond C. Yogurt with Bifidobacterium longum reduces erythromycin-induced gastrointestinal effects. Lancet 1987; 2(8549): 43.

37. G o r b a c h SL, Chang T-W, Goldin B. Suc-cessful treatment of relapsing Clostridium diffi-cile colitis with Lactobacillus GG. Lancet 1987; 2(8574): 1519.

38. B i l l e r JA, Katz AJ, Florez AF, et al. Treatment of recurrent Clostridium difficile colitis with Lactobacillus GG. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1995; 21: 224–6.

39. H a m i l t o n - M i l l e r JMT. Probiotics and prebiotics in the elderly. Postgrad Med J 2004; 80: 447–451.

40. I n d r i o F, Riezzo G, Raimondi F, Bisceglia M, Cavallo L, Francavilla R. The effects of pro-biotics on feeding tolerance, bowel habits, and gastrointestinal motility in preterm newborns. J Pediatr 2008; 152: 801-806.

41. N o m o t o K, Miake S, Hashimoto S, et al. Aug-mentation of host resistance to Listeria monocy-togenes infection by Lactobacillus casei. J Clin Lab Immunol 1985; 17: 91–7.

42. K a b i r AM, Aiba Y, Takagi A, Kamiya S, Miwa T, Koga Y. Prevention of Helicobacter pylori in-fection by lactobacilli in a gnotobiotic murine model. Gut 1997; 41: 49–55.

43. E l m e r GW, Surawiz CM, McFarland LV. Bio-therapeutic agents: a neglected modality for the treatment of selected intestinal and vaginal infec-tions. JAMA 1996; 275: 870–6.

44. R e i d G, Bruce AW, McGroarty JA, Cheng K-J, Costerton W. Is there a role for Lactobacilli in prevention of urogenital and intestinal infec-tions? Clin Microbiol Rev 1990; 3: 335–44.

45. H i l t o n E, Isenberg HD, Alperstein P, France K, Borenstein MT. Ingestion of yogurt contain-ing Lactobacillus acidophilus as prophylaxis for candidal vaginitis. Ann Intern Med 1992; 116: 353–7.

46. H i l t o n E, Rindos P, Esenberg HD. Lactobacil-lus GG vaginal suppositories and vaginitis. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33: 1433.

47. P i e r r e F, Perrin P, Champ M, Bornet, F., Me-flah K, Menanteau J. Short-chain fructo-oligosac-charides reduce the occurrence of colon tumours

30 PHARMACIA, vol. 61, No. 4/2014 M. Georgieva, L. Andonova, L. Peikova, Al. Zlatkov

and develop gut associated lymphoid tissue in Min mice. Cancer Research 1997; 57: 225–228.

48. R u s s e l l WR, Duncan SH, Flint HJ. The gut microbial metabolome: Modulation of cancer risk in obese individuals. The Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 2013; 72: 177–188.

49. I s o l a u r i E, Salminen S, Mattila-Sandholm T. New functional foods in the treatment of food allergy. Annals of Medicine 1999; 31: 299–302.

50. D u n c a n SH, Flint HJ. Probiotics and prebiot-ics and health in ageing populations. Maturitas 2013; 75(1): 44–50.

51. O m a r JM, Chan Y, Jones ML, Prakash S, Jones PJH. Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus amylovorus as probiotics alter body adiposity and gut microflora in healthy persons. Journal of Functional Foods 2013; 5: 116–123.

52. B e g l e y M, Sleator RD, Gahan CGM, Hill C. The contribution of three bile-associated loci (bsh, pva, and btlB) to gastrointestinal persistence and bile tolerance of Listeria monocytogenes. In-fection and Immunity 2005; 73: 894–904.

53. J a n k o v i c I, Sybesma W, Phothirath P, Ananta E, Mercenier A. Application of probiotics in food products-challenges and new approaches. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2010; 21: 175–181.

54. F A O / W H O. Guidelines for the evaluation of probiotics in food. 2002. Ontario, Canada, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Na-tions and World Health Organization. 11-27-2009. Ref Type: Report.

55. A g e n c e Francaise de Securite Sanitaire des Aliments (AFSSA). Alimentation infantile et modification de la flore intestinale. 2003. Ref Type: Report.

56. A g e n c e Francaise de Securite Sanitaire des Aliments (AFSSA). Effets des probiotiques et prebiotiques sur la flore et l’immunite´ de l’hom-me adulte. 2005. Ref Type: Report.

57. B g V V - Bundesinstitut fur gesundheitlichen Verbraucherschutz und Veterinar medizin. Final Report Working Group: Probiotic Microorgan-isms in Food. 1999. Ref Type: Report.

58. T u o m o l a E, Crittenden R, Playne M, Isolauri E, Salminen S. Quality assurance criteria for pro-biotic bacteria. Am J Clin Nutr 2001; 73(suppl): 393S–8S.

59. M a s c o L, Huys G, De Brandt E, Temmerman R, Swings J. Culture-dependent and culture-in-

dependent qualitative analysis of probiotic prod-ucts claimed to contain bifidobacteria. Interna-tional Journal of Food Microbiology 2005; 102: 221–230.

60. S e t t a n n i L, Corsetti A. The use of multiplex PCR to detect and differentiate food- and bever-age-associated microorganisms: A review. Jour-nal of Microbiological Methods 2007; 69: 1–22.

61. G o m e s AP, Pintado ME, Malcata FX. Hand-book of Dairy Food Analysis, CRC Press –Taylor & Francis, New York, USA, 2009.

62. M a u k o n e n J, Alakomi HL, Nohynek L, Hallamaa K, Leppämäki S, Mättö J, Saarela M. Suitability of the fluorescent techniques for the enumeration of probiotic bacteria in commercial non-dairy drinks and in pharmaceutical products. Food Res. Int. 2006; 39: 22–32.

63. Vo d n a r DC, Paucean A, Dulf FV, Socaciu C. HPLC Characterization of Lactic Acid Forma-tion and FTIR Fingerprint of Probiotic Bacteria during Fermentation Processes. Not. Bot. Hort. Agrobot. Cluj 2010; 38 (1): 109-113.

64. D a v i s R, Mauer LJ. Fourier tansform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy: A rapid tool for detection and analysis of foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Curr Res Technol Educ Topics, Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 2010; 2: 1582.

65. S a x e l i n M. Probiotic Formulations and Ap-plications, the Current Probiotics Market, and Changes in the Marketplace: A European Per-spective. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2008; 46: S76–9.

66. H a m i l t o n - M i l l e r JMT, Shah S, Winkler JT. Public health issues arising from microbi-ological and labelling quality of foods and sup-plements containing probiotic microorganisms, Public Health Nutrition 1999; 2(2): 223-229.

67. D a s h SK. All Probiotics Are Not The Same. Natural Health, The Doctors’ Prescription for Healthy Living 2003; 6(9): 30-31.

68. G r e e n A. How do you choose a Good Probi-otic?. The Clinical Use of Probiotics. Ed Barlow J. Probiotics International Ltd, United Kingdom., 2010.

69. S a r k a r S. Emergence of a Quality Assurance Program for Probiotic Supplemented Foods. In-ternational Journal of Food Science, Nutrition and Dietetics 2013; 2 (6): 1-7.

70. S a n d e r s ME. Huis in’t Veld J. Bringing a pro-bioticcontaining functional food to the market:

PHARMACIA, vol. 61, No. 4/2014 31Probiotics – health benefits, classification, quality assurance...

corresponding author:Maya GeorgievaDepartment of Pharmaceutical chemistry, Faculty of Pharmacy, Medical University – Sofia,1000, 2 Dunav str., Sofia, BulgariaTel: +359 2 9236515e-mail: [email protected]

microbiological, product, regulatory and label-ing issues. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 1999; 76: 293-315.

71. F A O / W H O [2001] Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food including Pow-der Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria”, Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Evaluation of Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food Including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria Amerian Cordo-ba Park Hotel, Cordoba, Argentina 1-4 October

2001, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations World Health Organization.

72. I S A P P [2004] Establishing Standards for Pro-biotic Products: ISAPP’s Role. As discussed at the 2004 ISAPP IAC meeting Copper Mountain, Colorado.

73. R e i d G, Jass J, Sebulsky MT, McCormick JK. Potential uses of probiotics in clinical practice. Clin Microbiol Rev 2003; 16: 658-672.