Prevalence and comorbidity of affective disorders in persons making suicide attempts in Hungary:...

-

Upload

judit-balazs -

Category

Documents

-

view

216 -

download

1

Transcript of Prevalence and comorbidity of affective disorders in persons making suicide attempts in Hungary:...

Journal of Affective Disorders 76 (2003) 113–119www.elsevier.com/ locate/ jad

Research report

P revalence and comorbidity of affective disorders in personsmaking suicide attempts in Hungary: importance of the first

depressive episodes and of bipolar II diagnoses

a , b c c a*´ ´ ´ ´ ´ ´Judit Balazs , Yves Lecrubier , Nora Csiszer , Janos Kosztak , lstvan BitteraDepartment of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Semmelweis University, Balassa Str. 6, 1083Budapest, Hungary

b ˆ ˆ `Inserm U 302, Hopital de la Salpetriere, Paris, FrancecElisabeth Hospital and Outpatient Clinic, Budapest, Hungary

Received 3 April 2000; received in revised form 25 February 2002; accepted 1 March 2002

Abstract

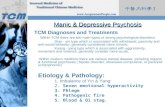

Background: The purpose of this study was to investigate the prevalence and comorbidity of affective disorders,especially current major depressive episode and bipolar disorder among suicide attempters in Hungary.Methods: Using astructured interview (Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview) determining 16 Axis I psychiatric diagnoses defined bythe DSM-IV and a semistructured interview collecting background information, the authors examined 100 consecutivesuicide attempters, aged 18–65.Results: Eighty-eight percent of the attempters had one or more current diagnoses on Axis I.In 69% it was major depressive episode and 60% of them were suffering their first episode. Thirty-five percent of thepatients with current major depressive episode had had hypomanic (n 5 19) or manic (n 55) episodes in the past. Seventypercent of the individuals received two or more current diagnoses on Axis I. Eighty-six percent of all current Axis I disorders(except major depressive episode) were diagnosed together with a current major depressive episode. The diagnosis of currentmajor depressive episode and the number of current psychiatric disorders was significantly and positively related to thenumber of suicide attempts, but the diagnosis of past major depressive episode was not.Limitations: This study includedsuicide attempters who had presented selfpoisoning, but not individuals with very high risk of fatality.Conclusions: Insuicide attempters there is a very high prevalence of affective disorders, especially major depression, first episode of majordepression and bipolar II disorder. This study underlines the importance of early detection and treatment of psychiatricdisorders for the prevention of suicidal behavior. 2003 Published by Elsevier B.V.

Keywords: Suicide attempt; Major depressive disorder; Bipolar disorder; Comorbidity; MINI

1 . Introduction ters or completers have a high rate of mentaldisorders (Barraclough et al., 1974; Beskow, 1979;

Numerous studies have shown that suicide attemp- Rich et al., 1986; Arato et al., 1988; Runeson, 1989;¨Henriksson et al., 1993; Isometsa et al., 1994;

*Corresponding author. Cheng, 1995; Beautrais et al., 1996; Conwell et al.,

0165-0327/03/$ – see front matter 2003 Published by Elsevier B.V.doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00084-8

´114 J. Balazs et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 76 (2003) 113–119

1996; Suominen et al., 1996). The most common absence of suicide intent was made by the admittingAxis I diagnoses preceding suicide or suicide at- physician and confirmed by an independent psychiat-tempts have consistently been found to be affective ric assessment.disorders (present in 30–90% of cases), followed by In total, 182 individuals were admitted due to asubstance-related disorders (19–60%) and schizo- suicide attempt during the study period. One hundredphrenia (2–14%). and twenty-four of them met the criteria for inclu-

Comorbidity of mental disorders (mainly depres- sion, 43 (23.5%) patients were older than 65, and 15sion with comorbid anxiety disorders) is also fre- (8.2%) patients were under the age of 18. Onequently reported in individuals who have made hundred of the 124 patients participated in this studysuicide attempts or died by suicide (Henriksson et (response rate, 80.7%). Three subjects refused par-al., 1993; Rudd et al., 1993; Beautrais et al., 1996; ticipation, 21 were not interviewed because of theSuominen et al., 1996). severity of their medical condition, one because of

In international comparisons of suicide rates Hun- his actual mental state and one patient did notgary was for many years in first place, but in the complete the interview due to akathisia.recent years it has moved to fifth place after Russiaand the Baltic countries (World Health Organization, 2 .2. Data collection1999). On the other hand, Hungary is the onlyformer communist country where the suicide rates Individuals who met the criteria for inclusion indecreased after the political changes of 1989/90 the study were interviewed in the hospital within 24(Sartorius, 1995; World Health Organization, 1999). hours of their suicide attempts. This minimized the

The aim of this study was to investigate the possible influence of factors, such as contact withprevalence of affective disorders among individuals family or friends and/or psychiatric treatment.who had recently attempted suicide in Hungary. The A structured interview according to DSM-IV, theemphasis was on current major depressive episodes Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interviewand their comorbidity with other Axis I mental (MINI) was administered to determine 16 Axis Idisorders according to DSM-IV (American Psychiat- psychiatric diagnoses including current diagnoses forric Association, 1994). dysthymic disorder, all major anxiety disorders,

substance-related dependence/abuse, eating disor-ders and both current and lifetime diagnoses for

2 . Methods major depressive episode, hypo/manic episode andpsychotic disorders (Lecrubier et al., 1997; Sheehan

´2 .1. Subjects et al., 1997, 1998; Balazs et al., 1998). The reliabili-ty of the diagnoses is described in Table 1.

The study population was a consecutive series of A semistructured interview was administered to100 individuals aged between 18 years and 65 years evaluate information on the following.who were admitted to the central ‘suicide-emergency

1unit’ of Budapest from June 6, 1999, to July 21, 1. The method used in the current suicide attempt.1999. This is an internal medical unit treating 2. Family history of psychiatric disorders andpatients with drug overdosing and poisoning. Each suicide.subject included into this investigation provided 3. Previous psychiatric treatment.written informed consent after being fully informed 4. Psychotropic drug treatment prior to the currentof the nature of study. admission.

Suicide attempters were defined as subjects admit- 5. The last time when the patient visited any medicalted because of deliberate acts of self-injury with facility.intention to die. The decision about the presence or 6. The number of previous suicide attempts.

7. History of general medical disorders.1 ´ ´ ´ ´ ¨ ´Erzsebet Korhaz es Rendelo Intezet (Elisabeth Hospital andOutpatient Clinic). We included general medical disorders with cur-

´J. Balazs et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 76 (2003) 113–119 115

Table 1 suicide was drug overdose (96%). Other methodsValidity of the MINI included fungicide and synthetic liquid solvent

Paris Florida Budapest poisoning (4%).

Subjects 346 330 200‘Gold standard’ CIDI SCID DIS 3 .3. Family historyConcordance k .0.63 k . 0.65 k . 0.60(for all diagnoses) A positive family history of psychiatric illnessMajor depressive disorder k 50.73 k 5 0.84 K 5 0.64

(psychiatric hospitalization or treatment) was re-currentported by 28% of the study population. More thanManic episode current k 50.65 k 5 0.67 N.A.

Manic episode lifetime k 50.63 k 5 0.73 Y 50.82 one-third (37%) of the suicide attempters had at leastHypomanic episode n.a. n.a. n.a. one family member with a history of attemptedcurrent suicide.Hypomanic episode n.a. n.a. Y 50.60lifetime

3 .4. General medical disordersCIDI, Composite International Diagnostic Interview; SCID,

Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis; DIS, DiagnosticThe lifetime prevalence of physical disordersInterview Schedule;Y, Yule’s colligation coefficient.

among the study population was 47%. Thirty percenthad a general medical disorder at the time of their

rent signs and symptoms and/or with impact on the suicide attempts.quality of life of the patients (e.g., migraine anddiabetes mellitus). Minor disorders, such as myopia 3 .5. Psychiatric treatmentwere not included.

The interviews were performed by two trained Altogether, 60% of the current suicide attempterspsychiatrists. had a history of psychiatric treatment, 29% had had a

psychiatric contact during the previous year and 59%of the subjects were receiving one or more psycho-2 .3. Statistical analysistropic drugs at the time of their suicide attempts.Twenty-four percent of the subjects were receivingDescriptive statistical methods were used and firstantidepressant treatments. Nine percent of the suicidesuicide attempters were compared to repeaters by

2 attempters were taking prophylactic treatment, whichusing thex -test. A probability level of, 0.05 waswas carbamazepine in all cases. Other frequentlyconsidered significant.prescribed psychotropic drugs included anxiolytics(40%), antipsychotics (20%) and hypnotics (12%).

Within the week prior to their suicide attempts3 . Resultsalmost a quarter (n 5 24) of the attempters hadvisited a health professional, two-thirds of them (n 53 .1. Gender, age16) being psychiatrists. Within the month before theirsuicide attempts, 66% of the subjects (n 5 66) hadSince 100 patients were included into the studycontacted health care facilities with exactly two-numbers and percents are equivalent. Out of 100thirds of them (n 5 44) being psychiatrists. We foundsuicide attempters who completed the interview,the same ratio for patients with affective disorders:31% were men and 69% were women. The mean agetwo-thirds of the 69 subjects with current majorof the subjects was 36.5 years (S.D.5 12.1) (males:depressive episode (n 546) and two out of the fivemean5 37.2 years, S.D.513.3; females: mean5 36patients with bipolar disorder without current majoryears, S.D.5 11.7).depressive episode visited a psychiatrist within themonth before their suicide attempts. Within the 33 .2. Method of attempted suicidemonths before their suicide attempts 79% of thesubjects had visited a health professional with nearlyThe most frequently used method of attempted

´116 J. Balazs et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 76 (2003) 113–119

Table 2The number of current DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses of 100 suicide attempters (total number; with and without current major depressiveepisode)

Current diagnosis Total With Without(n 5100) current currentn /% major depr. major depr.

episode episodea an (% ) N (%)

Major depressive episode 69 – –Generalized anxiety disorder 62 51 (82.3) 11 (17.7)Substance-related disorders(Alcohol dep. 30/abuse 3; 53 44 (83) 9 (17)non-alcohol dep. 19/abuse 1)Dysthymic disorder 20 18 (90) 2 (10)Panic disorder(without agoraphobia 12; 19 18 (94.7) 1 (5.3)with agoraphobia 7)Social phobia 14 13 (92.9) 1 (7.1)Psychotic disorder 13 11 (84.6) 2 (15.4)Eating disorders(Anorexia nervosa 2; 4 3 (75) 1 (25)bulimia nervosa 2)Post-traumatic stress disorder 3 3(100) 0Agoraphobia without history 1 1 (100) 0of panic disorderObsessive–compulsive disorder 0 0 0Hypomanic episode 0 0 0Manic episode 0 0 0No Axis I diagnosis 12 – –

a Percents are related to the disorder in the same row.

two-thirds of them (n 5 65) being psychiatrists. nosis of current major depressive episode, 60% ofMore than one-fifth (21%) had visited no health them were having their first major depressive episodeprofessional within 3 months before their suicide and 40% of them had had one or more previousattempts. major depressive episode(s).

Twenty-four percent of the subjects had hadhypomanic episodes in the past, and 5% had had

3 .6. DSM-IV diagnoses manic episodes. More than one-third (35%) of the

Eighty-eight percent of the suicide attemptersreceived at least one current diagnosis on Axis I(Table 2) and 92% of them had at least one lifetime Table 3

Lifetime, but not current DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses of 100 suicideAxis I diagnosis (Table 3).attemptersThe most frequent current diagnosis was major

depressive episode (69%), followed by generalized Past diagnosis total (n 5 100)n /%anxiety disorder (62%), substance dependence and

abuse (53%) (alcohol dependence/abuse5 33%, Major depressive episode 41Hypomanic episode 24non-alcohol dependence/abuse5 20%), socialPsychotic disorder 16phobia (14%) and psychotic disorder (13%).Manic episode 5Among suicide attempters who received a diag-

´J. Balazs et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 76 (2003) 113–119 117

Table 4Comparison of current major depressive episode of first attempters and repeaters

Attempt Current No currentMajor depressive episode Major depressive episode

a aWith past Without past % With past Without past %maj. depr. maj. depr. maj. depr. maj. depr.n n n n

1 10 13 53.5 5 15 46.52 9 9 75 5 1 253 3 8 84.6 2 0 15.4More 6 11 85 1 2 15.8than 3

a 2Percents are related to the number of subjects in the same row:x 5 9.271, df5 3, P , 0.05.

patients with current major depressive episode had this diagnosis. The rate of current major depressivehad hypomanic (n 5 19) or manic (n 55) episodes in episode was significantly higher among the personsthe past. Four out of the five subjects with past with previous suicide attempts than among the first

2hypomanic episode and without current major depre- attempters (46/57580.7 vs. 23/435 53.6%, x 5

ssive episode had had a past major depressive 8.5, df5 1, P , 0.02). The diagnosis of currentepisode. Altogether these 28 subjects were consid- major depression was significantly associated withered as patients with bipolar I or bipolar II disorders. the number of suicide attempts (Table 4). In firstMore than three-quarters (82.1%) of the bipolar attempters 33.9% had a past major depression andpatients belonged to the bipolar II group. 45.6% of the persons with repeated attempts had

We could not detect any current psychiatric disor- major depression in the past. The diagnosis of pastder in 12% of the study population. However, among major depression was not significantly related to the

2them one subject had a history of past psychotic number of suicide attempts (x 5 3.978, df5 3; P 5

episode and one a history of a past major depressive ns).episode and a past hypomanic episode (bipolar IIdisorder). One individual had psychosomatic andthree somatic disorders including one patient with 4 . Discussionbipolar II disorder with no current episode.

The results of this study confirm those of previous3 .7. Comorbidity of mental disorders findings showing high rates of mental disorders

among suicide attempters (Rich et al., 1986; Beaut-Seventy percent of the subjects received two or rais et al., 1996; Suominen et al., 1996). As ex-

more current diagnoses on Axis I. Among patients pected, the most frequent diagnosis was majorwith comorbid diagnoses, 30% had two, 26% three depressive episode. We found that 60% of suicideand 44% more than three diagnoses. attempters with major depressive episode had had no

Eighty-six percent of all current Axis I disorders previous episode. Therefore they attempted suicide(except major depressive episode) were diagnosed during the first major depressive episode of their life.together with a current major depressive episode To our knowledge, this is the first study in which the(Table 2). rate of first major depressive episode among suicide

attempters has been examined.3 .8. Comparison of first attempters and repeaters Several studies have confirmed the importance of

bipolar disorder as a risk factor for suicide. InFifty-seven percent of the current attempters were comparison to previous studies, which have iden-

repeaters. Of these, 80.7% had current major depres- tified bipolar disorder in 10–15% of suicide victimssion, while only 53.5% of the first attempters had or suicide attempters (Beautrais et al., 1996; Arato et

´118 J. Balazs et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 76 (2003) 113–119

al., 1988; Rihmer et al., 1995), in the present study contrast, the study by Beautrais et al. (1996) in-the prevalence of bipolar disorder was somewhat cluded an approximately equal number of men andhigher, at 28%. More than one-third (35%) of women, which the authors thought was due to thepatients with current major depressive episode fact that those attempts were at the more serious endbelonged to the bipolar group. This is somewhat of the spectrum. Our study population were at thelower than Rihmer et al. (1990) found when examin- less dangerous end of the spectrum of suicideing 100 suicide victims in Hungary with primary attempt behavior, because individuals who attemptedmajor depression at the time of suicide, where 47% suicide by methods with very high risk of fatality,of the cases had had bipolar disorder (Rihmer et al., such as hanging or gunshot were not included into1990). But taking into account that in our study 60% this study. In addition, the design of the study wasof attempters with major depressive disorder only that subjects had to be interviewed within 24 h of thehad their first episode, the rate of bipolar disorder hospital admission. This factor excluded all patientsamong our subjects may have been underestimated. whose medical condition did not allow them to beAmong the bipolar patients, 85.7% belonged to the interviewed within this time.bipolar II group. This result is in agreement with Although 69% of the subjects had a current majorprevious reports suggesting that suicide behavior is depressive episode, only 37.3% (n 522) of themmore frequent in bipolar II than in bipolar I disorder were receiving antidepressant treatment (altogether(Dunner et al., 1976; Endicott et al., 1985; Rihmer et 24 out of the 100 subjects were receiving antidepres-al., 1990; Rihmer and Pestality, 1999). Our findings sant treatment). Nine subjects were prescribedsupport previous studies which have demonstrated prophylactic treatment (carbamazepine), includingthat suicide attempts are more common in bipolar only two out of the 28 bipolar patients; these twopatients than those with unipolar depression (Dunner patients belonged to the bipolar I group and noet al., 1976; Endicott et al., 1985; Bulik et al., 1990; patient in the bipolar II group was receivingRihmer et al., 1990; Rihmer and Pestality, 1999) and prophylactic treatment.that bipolar (particularly bipolar II) patients are over According to our data, the number of suiciderepresented among suicide victims (Rihmer et al., attempts was not related to the history of past major

´ ´1995). Szadoczky et al. (1998) found high lifetime depression episode, but positively and significantlyprevalence (5.1) for bipolar disorder in Hungary. related to the presence of current major depressiveFuture studies have to address whether the high episode and to the number of current psychiatricproportion of patients with bipolar disorder is some- disorders.thing special about the Hungarian population includ- There were 12 cases in which no current psychiat-ing suicide attempters. However the rate of bipolar II ric disorder could be detected. Five of these patientspatients was similar to ours in a French sample of had some psychiatric or somatic diseases in the pastpatients with current major depressive episode (40%) which could be related to their suicide attempt; seven(Allilaire et al., 2001). cases of attempted suicide may be related to unde-

Our findings are similar to previous studies that tected life events or disorders, such as brief recurrenthave shown high rates of comorbid mental disorders depression, which could not be explored by theamong individuals making suicide attempts (Beaut- MINI. Another limitation of the study is that therais et al., 1996; Henriksson et al., 1993; Rudd et al., findings are restricted to subjects with less dangerous1993; Suominen et al., 1996). More than two-thirds suicide attempts.(70%) of the subjects enrolled in our study met the In conclusion, this study underlines the importanceDSM-IV criteria for two or more disorders and only of early detection and treatment of psychiatric dis-14% of all current Axis I disorders were diagnosed orders for the prevention of suicidal behavior. Cur-without current major depressive episode. rent depressive episode was the most important

In this study the female-to-male ratio for attempt- variable. In the study population the treatment ofed suicide was 2.25:1. This finding is within the affective disorders was insufficient: two-thirds of therange of female-to-male ratios for attempted suicide patients visited a psychiatrist within the monthof 1.4:1 to 4.0:1 published by Diekstra (1993). In before their suicide attempts, but only one-third of

´J. Balazs et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 76 (2003) 113–119 119

factors in the severity of affective illness. Biol. Psychiatry 11,the patients with major depressive episode were31–42.receiving antidepressant treatment and only 7% of

Endicott, J., Nee, J., Andreasen, N., Clayton, P., Keller, M.,the patients with bipolar disorder were receivingCoryell, W., 1985. Bipolar II: combine or keep separate? J.

prophylactic treatment. The most striking findings of Affect. Disord. 8, 17–28.this study were the very high prevalence of first Henriksson, M.M., Aro, H.M., Martutunen, M.J., Heikkinen,

¨ ¨M.E., lsometsa, E.T., Kuoppasalmi, K.l., Lonnqvist, J.K., 1993.episodes of depression and of bipolar II disordersMental disorders and comorbidity in suicide. Am. J. Psychiatryamong suicide attempters.150, 935–940.

¨Isometsa, E.T., Henriksson, M.M., Aro, H.M., Heikkinen, M.E.,¨Kuoppasalmi, K.I., Lonnqvist, J.K., 1994. Suicide in major

depression. Am. J. Psychiatry 151, 530–536.A cknowledgementsLecrubier, Y., Sheehan, D.V., Weiller, E., Amorim, P., Bonora, I.,

Sheehan, H.K., Janavs, J., Dunbar, G.C., 1997. The MINI´We wish to thank Zoltan Rihmer for his valuable International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) a short

help. diagnostic structured interview: reliability and validity accord-ing to the CIDI. Eur. Psychiatry 12, 224–231.

Rich, C.L., Young, D., Fowler, R.C., 1986. San Diego suicidestudy, I: young vs. old subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 43,

R eferences 577–582.´Rihmer, Z., Barsi, J., Arato, M., Demeter, E., 1990. Suicide in

subtypes of primary depression. J. Affect. Disord. 18, 221–Allilaire, J.F., Hantouche, E.G., Sechter, D., Bourgeois, M.L.,225.Azorin, J.M., Lancrenon, S., Chatenet-Duchene, L., Akiskal,

Rihmer, Z., Pestality, P., 1999. Bipolar II disorder and suicidalH.S., 2001. Frequency and clinical aspects of bipolar IIbehavior. Psychiatr. Clin. North. Am. 22, 667–673.disorder in a French multicenter study: EPIDEP. Encephale 27

Rihmer, Z., Rutz, W., Pihlgren, H., 1995. Depression and suicide(2), 149–158.on Gotland. An intensive study of all suicides before and afterAmerican Psychiatric Association, 1994. In: Diagnostic anda depression training programme for general practitioners. J.Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition. AmericanAffect. Disord. 35, 147–152.Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC.

Rudd, M.D., Dahm, P.F., Rajab, M.H., 1993. Diagnostic comor-Arato, M., Demeter, E., Rihmer, Z., Somogyi, E., 1988. Re-bidity in persons with suicide ideation and behaviour. Am. J.trospective psychiatric assessment of 200 suicides in Budapest.Psychiatry 150, 928–934.Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 77, 454–456.

Runeson, B., 1989. Mental disorders in youth suicide: DSM-III-R´ ´Balazs, J., Bitter, I., Hideg, K., Vitrai, J., 1998. A M.I.N.I. es aAxes I and II. Acta Pscychiatr. Scand. 79, 490–497.´ ¨´ ¨ ´ ´M.I.N.I. Plusz kerdoıv magyar nyelvu valtozatanak kidolgoz-

Sartorius, N., 1995. Recent changes in suicide rates in selectedasa (The Hungarian version of the M.I.N.I. and the M.I.N.I.Eastern European and other European countries. Int. Psycho-Plus). Psychiatr. Hung. 13 (2), 160–168.geriatr. 7, 301–308.Barraclough, B., Bunch, J., Nelson, B., Sainsbury, P., 1974. A

Sheehan, D.V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, H.K., Amorim, P., Janavs,hundred cases of suicide: clinical aspects. Br. J. Psychiatry 125,J., Weiller, E., Hergueta, T., Baker, R., Dunbar, G.C., 1998.355–373.The MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.):Beautrais, A.L., Joyce, P.R., Mulder, R.T., Fergusson, D.M.,The development and validation of a structured diagnosticDeavoll, B.J., Nightingale, S.K., 1996. Prevalence and comor-psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J. Clin. Psychi-bidity of mental disorders in persons making serious suicideatry 59 (Suppl. 20), 22–33.attempts: a case-control study. Am. J. Psychiatry 153, 1009–

Sheehan, D.V., Lecrubier, Y., Sheehan, H.K., Janavs, J., Weiller, E.,1014.Keskiner, A., Schinka, J., Knapp, E., Sheehan, M.F., Dunbar,Beskow, J., 1979. Suicide and mental disorders in Swedish men.G.C., 1997. Reliability and validity of the MINI InternationalActa Pscychiatr. Scand. 277 (Suppl.), 1–138.Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P.Bulik, C.M., Carpenter, L.L., Kupfer, D.J., Frank, E., 1990.Eur. Psychiatry 12, 232–241.Features associated with suicide attempts in recurrent major

¨Suominen, K., Henriksson, M., Suokas, J., Isometsa, E., Ostamo,depression. J. Affect. Disord. 18, 29–37.¨A., Lonnqvist, J., 1996. Mental disorders and comorbidity inCheng, A.T.A., 1995. Mental illness and suicide. Arch. Gen.

attempted suicide. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 94, 234–240.Psychiatry 52, 594–603.´ ´ ´ ¨Szadoczky, E., Papp, Zs., Vitrai, J., Rıhmer, Z., Furedi, J., 1998.Conwell, Y., Duberstein, P.R., Cox, C., Herrmann, J.H., Forbes,The prevalence of major depressive and bipolar disorders inN.T., Caine, E.D., 1996. Relationships of age and Axis IHungary. Results from a national epidemiologic survey. J.diagnoses in victims of completed suicide: a psychologicalAffect. Disord. 50, 153–162.autopsy study. Am. J. Psychiatry 153, 1001–1008.

World Health Organization, 1999. Suicide Rates. Most recent yearDiekstra, R.F.W., 1993. The epidemiology of suicide behaviour: aavailable, as of November 1999. Internet.http: / /www.who.int /review of three continents. World Health Stat. Q. 46, 52–68.mental health /pages/suicide.htmlDunner, D.L., Gershon, E.S., Goodwin, F.K., 1976. Heritable

]