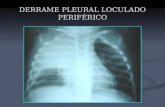

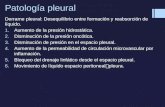

DERRAME PLEURAL LOCULADO PERIFÉRICO. DERRAME PLEURAL LOCULADO E LIVRE.

Pleural procedures

-

Upload

gary-davies -

Category

Documents

-

view

213 -

download

0

Transcript of Pleural procedures

Pleura

Pleural proceduresGary Davies

AbstractPleural disease and the need for sampling of or treatment of the pleural

space are common in hospital medical practice. It is important that all of

these procedures are undertaken in a safe and uniform way to aid good

clinical treatment and reduce the risk of complications. This chapter

contains guidance on simple aspiration, the insertion of chest drains

and pleurodesis. Though not exhaustive, it should provide you with the

necessary basis for understanding the procedures and the techniques

involved.

Keywords aspiration; chest drain; pleurodesis; pneumothorax; Seldinger

technique

Simple aspiration

Simple aspiration is used for both fluid and air, with small but important differences in procedure.

Pneumothorax – simple aspiration should be considered in all patients with spontaneous or iatrogenic (non-ventilated) pneu-mothorax. Intercostal tube drainage may be required in a small proportion of these patients and in these cases a Seldinger type drain is sufficient. Figure 1 shows an algorithm for the initial treatment of pneumothorax based on guidelines published by the British Thoracic Society.1

• After cleaning the skin, infiltrate the skin, subcutaneous tis-sues and pleura with 5–10 ml of 1% lignocaine. This can be administered in the fifth intercostal space in the mid-axillary line or in the mid-clavicular line in the second intercostal space. • After allowing time for the local anaesthetic to take effect, insert a grey or brown cannula (16 G or 14 G) into the pleural space through the anaesthetized tract. Remove the needle and attach a three-way tap, a 50 ml Luer-lock syringe and a cut-off drip set as shown in Figure 2. The end of the drip set should be placed in the jug under sterile water. • Aspiration continues until resistance is felt, 2.5 litres have been aspirated (50 x 50 ml) or the patient is coughing excessively. • If resistance is felt, wait 5 minutes then attempt to re-aspirate. If no air can be aspirated, obtain a chest radiograph after 1 hour. If more than 50 ml can be aspirated, a small leak persists. • If the check radiograph shows little or no pneumothorax, the patient can be sent home or observed overnight.

Gary Davies MRCP is Consultant in Respiratory and Acute Medicine

at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London, UK. Competing

interests: none declared.

MeDICINe 36:6 32

Pleural fluid can be aspirated as for pneumothorax, with the following variations. • Ultrasonography may be helpful in determining the position or loculation of fluid. • Aspiration is usually performed posteriorly at the level of dull-ness to percussion. • Any pleural biopsy (see below) should be performed before aspiration and drainage of the fluid.

Management of pneumothorax

Chronic lung disease

Aspiration

Successful

Intercostal chest drain

In extremis

Moderate/completelung collapse

Completelung collapse

Significant shortnessof breath

Significant shortnessof breath

In-patientobservation

Out-patient reviewin 10 days (or 2 weeks)

No

No

No

No

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes Yes

Yes Yes Yes No

No

No

Figure 1

Figure 2 equipment used for simple aspiration of pneumothorax.

8 © 2008 elsevier ltd. all rights reserved.

Pleura

• No water is required in the jug before commencing the pro-cedure, and the volume of aspirate should be measured. • Send the fluid for microscopy and culture, protein, glucose and cytology (if carcinoma is considered), noting its colour and consistency. • Only 1.5 litres should be removed at a time (discontinue before this if the patient feels faint or suffers excessive coughing or increased dyspnoea, or no further fluid can be obtained). • An early post-aspiration chest radiograph detects underlying lung masses and is a baseline for re-accumulation of fluid.

Pleural biopsy

Pleural biopsy can be important in the diagnosis of pleural ef-fusion. It should always be performed before aspiration. In the majority of cases pleural biopsies can now be performed with more accuracy under ultrasound guidance by a radiologist. In the event of this not being available, the following should be undertaken. • Use local anaesthetic as above. A greater amount may be required than for simple aspiration. • Make a small skin incision before inserting the Abram’s needle through the intercostal tissues into the pleural space. • Aspirate fluid through the Abram’s needle (open the port by twisting with a 20 ml syringe attached). • With the needle open, angle it to position the open port against the pleura as acutely as possible to one side, and retract until the pleura catches in the open port. • Close the port by twisting the inner part clockwise. • Two biopsies should be taken on each side and one from the downwards direction, avoiding the neurovascular bundle above, before withdrawing the needle completely. • Specimens are within the needle and can be removed by flush-ing and/or using a green needle.

Intercostal chest tube drainage

Intercostal chest tube drainage is required in the treatment of pneumothorax, for complete removal of pleural fluid (including before chemical pleurodesis) and for drainage of an empyema. When considering which type of drain to insert it is important to consider the substance to be drained. For air and most pleural effusions, a drain up to 20 G would be sufficient and, therefore, a Seldinger drain is the most appropriate. For haemothorax and empyemas a larger size of drain and a more traditional drain insertion are required. Insertion should be performed into the ‘safe triangle’ where possible. This imaginary triangle is bor-dered by the anterior border of the latissimus dorsi, the lateral border of the pectoralis major muscle, a line superior to the horizontal level of the nipple, and an apex below the axilla. By using the ‘safe triangle’ the potential risk of visceral perforation is significantly reduced. If an area outside of the safe triangle is to be used, help with positioning by ultrasound should be considered.

Intercostal drain insertionTraditional drain • Consider premedication with pethidine (50–75 mg depending on respiratory status) 30 minutes before the procedure.

MeDICINe 36:6 32

• Infiltrate the tissues in the fifth intercostal space in the mid-axillary line using generous quantities of local anaesthetic, particularly for the pleura. • Select the smallest drain appropriate for the substance to be drained. • Make a 2.5–5 cm incision in the skin and the immediate subcutaneous tissues. Using blunt dissection with long-nosed forceps, dissect down and through the muscle layer and pleura. • Using a partially retracted trocar (at least 2–3 cm) or long-nosed forceps through the side drainage holes, insert the drain through the dissection, directing it towards the apex. • Remove the trocar and attach the drain to an underwater seal, ensuring a secure union (this may require use of clear film). • Suture as shown in Figure 3. • Using two clear adhesive dressings secure the drain at the drain site. These should be used at right angles to the drain to sandwich the drain between them. This allows the site of inser-tion of the drain to be observed directly. • Secure the drain tubing to the skin with adhesive plaster.

Seldinger drainage kitLarge-bore chest drains can be difficult to insert and can lead to adverse complications. The Seldinger drain is a newer system for the insertion of pleural drains for air or fluid. Insertion is similar to that of a central venous catheter. • Consider premedication with pethidine (50–75 mg depending on respiratory status) 30 minutes before the procedure. Despite the less invasive nature of the procedure, analgesia may be required. • Local anaesthetic is applied to the skin as for standard chest drain insertion. • Make a small (1 cm) incision in the skin. • A 16 G introducer needle attached to a syringe is inserted into the pleural space. • Aspirate air or fluid with the syringe to confirm that the posi-tioning is correct. • A guide-wire is passed through the syringe and needle and into the pleural space until 10 cm of the wire end remains visible. • Remove the syringe and needle, holding the guide-wire. • Pass the dilator over the guide-wire to dilate the tract through the chest wall. The dilator should not be advanced more than 1 cm beyond the inner pleural surface to reduce the potential risk of visceral perforation. • Remove the dilator and pass the catheter, with a removable internal stiffener, over the guide-wire and into the pleural space. • Remove the internal stiffener and attach the three-way tap. • The three-way tap can then be attached to a drainage device or underwater seal. • Secure the catheter to the skin using sutures and the holed attachment collar (if present). • Suturing can be performed as shown in Figure 3. • Using two clear adhesive dressings secure the drain at the drain site. These should be used at right angles to the drain to sandwich the drain between them. This allows the site of inser-tion of the drain to be observed directly. • Secure the drain tubing to the skin with adhesive plaster.This method of insertion is easier for the operator and less trau-matic for the patient. Its disadvantage is the small bore of the drain, which cannot be used for viscous pleural fluid, empyemas or suction.

9 © 2008 elsevier ltd. all rights reserved.

Pleura

Chest drain placement

Appearance of the drain with anchoring suture and mattress suture in place

Mattress suture – to be tied when the drain is removed

Mattress suture – placement and after drain removal

Most drains are placed in the fifth intercostal space in the mid-axillary line, with an anchoring suture. For minimal scarring, a stitch is left in situ ready to close the wound on removal of the drain (mattress suture). One piece of foam dressing is placed over the drain site and secured with tape.

Anchoring suture – tied onto the skin above the mattress suture, and then wound around the drain and tied securely at 1 cm intervals; removed completely to remove the drain

Placement (side view)

After drain removal, only this stitch remains

Stitch in place

Stitch pulled tightand tied after drain removal

Figure 3

Chemical pleurodesis

Chemical pleurodesis is less effective than video-assisted thora-coscopic surgery, but remains useful because it is less invasive and therefore safer in patients with terminal disease or compro-mised lung function. • Using an intercostal drain inserted as above, the underwater seal is connected to suction at 10–20 cm H2O. • Pre-medication with pethidine (50–100 mg) is required. • When there is no further drainage, the drain is clamped. • 2% lignocaine (20 ml) is instilled into the pleural space. This is followed 5–10 minutes later by dissolved sclerosant. The drain

MeDICINe 36:6 330

remains clamped and is left in situ for 4 hours, before being connected to an underwater seal and unclamped. • If no further drainage occurs, the drain is removed. ◆

ReFeRenCe

1 Henry M, arnold T, Harvey J, On behalf of the British Thoracic

Society Pleural Disease Group. BTS guidelines for the management

of spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorax 2003; 58(suppl 2): ii39–52.

© 2008 elsevier ltd. all rights reserved.