PLATELET DISORDERS. Bleeding due to thrombocytopenia or abnormal platelet function is characterized...

-

Upload

myra-stanley -

Category

Documents

-

view

227 -

download

3

Transcript of PLATELET DISORDERS. Bleeding due to thrombocytopenia or abnormal platelet function is characterized...

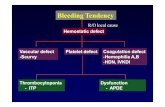

Bleeding due to thrombocytopenia or abnormal plateletfunction is characterized by purpura and bleeding frommucous membranes. Bleeding is uncommon with plateletcounts above 50 × 109/L, and severe spontaneous bleedingis unusual with platelet counts above 20 × 109/L

ThrombocytopeniaThis is caused by reduced platelet production in the bonemarrow, excessive peripheral destruction of platelets orsequestration in an enlarged spleen .The underlyingcause may be revealed by history and examination buta bone marrow examination will show whether the numbersof megakaryocytes are reduced, normal or increased, andwill provide essential information on morphology. Specificlaboratory tests may be useful to confirm the presence ofsuch conditions as paroxysmal nocturnal haemoglobinuria(PNH) or systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).In patients with thrombocytopenia due to failure of production,no specific treatment may be necessary but theunderlying condition should be treated if possible. Where theplatelet count is very low or the risk of bleeding is very high,then platelet transfusion is indicated

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)Thrombocytopenia is due to immune destruction of platelets.The antibody-coated platelets are removed following bindingto Fc receptors on macrophages.

ITP in childrenThis occurs most commonly in children (age 2–6 years). Ithas an acute onset with mucocutaneous bleeding and theremay be a history of a recent viral infection, including varicellazoster or measles. Although bleeding may be severe, lifethreatening hemorrhage is rare (~ 1%). Bone marrow examinationis not usually performed unless treatment becomesnecessary on clinical grounds

ITP in adultsThe presentation is usually less acute than in children. AdultITP is characteristically seen in women and may be associatedwith other autoimmune disorders such as SLE, thyroiddisease and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia (Evans’ syndrome),

in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia andsolid tumours, and after infections with viruses such as HIV.

Platelet autoantibodies are detected in about 60–70% ofpatients, and are presumed to be present, although notdetectable, in the remaining patients; the antibodies oftenhave specificity for platelet membrane glycoproteins IIb/IIIaand/or Ib.

Clinical featuresMajor haemorrhage is rare and is seen only in patients withsevere thrombocytopenia. Easy bruising, purpura, epistaxisand menorrhagia are common. Physical examination isnormal except for evidence of bleeding. Splenomegaly israre.

InvestigationThe only blood count abnormality is thrombocytopenia.Normal or increased numbers of megakaryocytes are foundin the bone marrow (if examination is performed), which isotherwise normal. The detection of platelet autoantibodies isnot essential for confirmation of the diagnosis, which often depends on

exclusion of other causes of excessive destructionof platelets.

TreatmentChildrenChildren do not usually require treatment. Where this is necessaryon clinical grounds, high-dose prednisolone is effective,

given for a very short course. Intravenous immunoglobulin)i.v. IgG (should be reserved for very serious bleeding or

urgent surgery. Chronic ITP is rare and requires specialistmanagement

AdultsPatients with platelet counts greater than 30 × 109/L requireno urgent treatment unless they are about to undergo a surgicalprocedure.First-line therapy consists of oral corticosteroids 1 mg/kgbody weight. Approximately 66% will respond to prednisolonebut relapse is common when the dose is reduced. Only

33% of patients can expect a long-term response and long termremission is seen in only 10–20% of patients followingstopping prednisolone. Patients who fail to respond to corticosteroidsor require high doses to maintain a safe plateletcount should be considered for splenectomy.Intravenous immunoglobulin (i.v. IgG) is effective. It raisesplatelet count in 75% and in 50% the platelet count will normalize.Responses are only transient (3–4 weeks) with littleevidence of any lasting effect. However, it is very usefulwhere a rapid rise in platelet count is desired, especiallybefore surgery. There are also advocates for high dose corticosteroidsfor additional therapy

Second-line therapy involves splenectomy, to which themajority of patients respond – two-thirds will achieve anormal platelet count. Patients who do not have a completeresponse can still expect some improvement

Third-line therapy. For those that fail splenectomy, a widerange of other therapies are available. These include highdosecorticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, Rh0(D)immune globulin (anti-D), vinca alkaloids, danazol, immunosuppressiveagents such as azathioprine, ciclosporin anddapsone, combination chemotherapy, mycophenolatemofetil. Major difficulties with many third-line therapies aremodest response rates and slow onset of action. Consequentlythere is also interest in the use of specific monoclonalantibodies such as rituximab, as well as recombinant thrombopoietin.

However, clinical trials of thrombopoietin werestopped because of thrombocytopenia but eltrombopag, athrombopoietin receptor agonist (which binds to anotherpoint of the thrombopoietin receptor), has been shown toincrease platelets in ITP. Romiplostim, a novel thrombopoiesisprotein given weekly subcutaneously, has also beenshown to significantly increase platelet count in ITP on along-term basis; there were no major adverse effects in thistrial. Platelet transfusions are reserved for intracranial orother extreme haemorrhage, where emergency splenectomymay be justified.

Thrombotic thrombocytopenicpurpura (TTP))TTP is a rare, but very serious condition, in which plateletconsumption leads to profound thrombocytopenia. There isa characteristic symptom complex of florid purpura, fever,fluctuating cerebral dysfunction and haemolytic anaemiawith red cell fragmentation, often accompanied by renalfailure. The coagulation screen is usually normal but lacticdehydrogenase (LDH) levels are markedly raised as a resultof haemolysis. TTP arises due to endothelial damage andmicrovascular thrombosis. This occurs due to a reduction inADAMTS 13 (A Disintegrin-like and Metalloproteinase domainwith Thrombospondin-type motifs), a protease which is normallyresponsible for VWF degradation. ADAMTS 13 isneeded to break down ultra large von Willebrand factormultimers (UL VWFMs) into smaller haemostatically activefragments that interact with platelets. Reduction in ADAMTS13 results in the adhesion and aggregation of platelets to ULVWFMs and multiorgan microthrombi. In most sporadiccases there is a true deficiency of the ADAMTS 13, associatedwith antibodies to ADAMTS 13. In some congenitalcases the deficiency is due to mutations in the ADAMTS 13gene. Secondary causes of acute TTP include pregnancy,oral contraceptives, SLE, infection and drug treatment,including the use of ticlopidine and clopidogrel. Such casesmay have a variable ADAMTS 13 activity at presentationand may or may not have associated antibodies toADAMTS 13.Treatment consists of plasma exchange as the mainstay

INHERITED COAGULATION DISORDERSCoagulation disorders may be inherited or acquired. Theinherited disorders are uncommon and usually involve

deficiencyof one factor only. The acquired disorders occur morefrequently and almost always involve several coagulationfactors; they are considered in the next subsection.In inherited coagulation disorders, deficiencies of allfactors have been described. Those leading to abnormalbleeding are rare, apart from haemophilia A (factor VIIIdeficiency), haemophilia B (factor IX deficiency) and vonWillebrand disease.

Haemophilia AThis is due to a lack of factor VIII. VWF is normal in haemophilia. The prevalence of haemophilia A is about 1in 5000 of the male population. It is inherited as an X-linkeddisorder. If a female carrier has a son, he has a 50% chanceof having haemophilia, and a daughter has a 50% chance ofbeing a carrier. All daughters of men with haemophilia arecarriers and the sons are normal.

The human factor VIII gene is large, constituting about0.1% of the X chromosome, encompassing 186 kilobases of

DNA. Various genetic defects have been found, includingdeletions, duplications, frameshift mutations and insertions.In approximately 50% of families with severe disease, thedefect is an inversion. There is a high mutation rate, withone-third of cases being apparently sporadic with no familyhistory of haemophilia

Clinical and laboratory featuresThe clinical features depend on the level of factor VIII. Thenormal level of factor VIII is 50–150 iu/dL.

■Levels of less than 1 iu/dL (severe haemophilia) areassociated with frequent spontaneous bleeding fromearly life. Haemarthroses are common and recurrentbleeding into joints leads to joint deformity and cripplingif adequate treatment is not given. Bleeding intomuscles is also common, and intramuscular injectionsshould be avoided.

■Levels of 1–5 iu/dL (moderate haemophilia) areassociated with severe bleeding following injury andoccasional spontaneous bleeds.

■Levels above 5 iu/dL (mild haemophilia) are associatedusually with bleeding only after injury or surgery. Itshould be noted that patients with mild haemophilia canstill bleed badly once haemostasis has failed. Diagnosisin this group is often delayed until quite late in life

The most common causes of death in people with haemophiliaare cancer and heart disease, as for the generalpopulation. Cerebral haemorrhage is much more frequent. Inrecent years, HIV infection and liver disease (due to hepatitisC) have become a more common cause of death. Theseinfections were acquired from blood transfusion by manypatients that were treated with factor concentrates prior to

1986 .Since 1986 such plasma derived products are all virallyinactivated with heat or chemicals.

The main laboratory features are .The abnormal findings are a prolonged APTT

and a reduced level of factor VIII. The PT, bleeding time andVWF level are normal.

TreatmentBleeding is treated by administration of factor VIII concentrateby intravenous infusion.■ Minor bleeding: the factor VIII level should be raised to20–30 iu/dL.■ Severe bleeding: the factor VIII should be raised to atleast 50 iu/dL.■ Major surgery: the factor VIII should be raised to 100 iu/dL preoperatively and maintained above 50 iu/dL untilhealing has occurred

Factor VIII has a half-life of 12 hours and therefore must beadministered at least twice daily to maintain the requiredtherapeutic level. Continuous infusion is sometimes used tocover surgery. Factor VIII concentrate is freeze-dried and canbe stored in domestic refrigerators at 4°C. This allows it tobe administered by the patient immediately after bleedinghas started, reducing the likelihood of chronic damage tojoints and the need for inpatient care.Recombinant factor VIII concentrate is well establishedas the treatment of choice for people with haemophilia, buteconomic constraints and limited production capacity forrecombinant factors have resulted in many patients still beingoffered treatment with plasma derived concentrates, particularlyin developing countries.To prevent recurrent bleeding into joints and subsequentjoint damage, patients with severe haemophilia are givenfactor VIII infusions regularly three times per week. Such

‘prophylaxis’ treatment is usually started in early childhood)around 2 years of age(

Synthetic vasopressin (desmopressin – an analogue ofvasopressin) – intravenous, subcutaneous or intranasal–

produces a 3–5 fold rise in factor VIII and is very useful inpatients with a baseline level of factor VIII > 10 iu/dL. Itavoids the complications associated with blood productsand is useful for treating bleeding episodes in mild haemophiliaand as prophylaxis before minor surgery. It is ineffectivein severe haemophilia.

People with haemophilia should be registered at comprehensivecare centres (CCC), which take responsibility for theirfull medical care, including social and psychological support.

Each person with haemophilia carries a special medical cardgiving details of the disorder and its treatment

ComplicationsUp to 30% of people with severe haemophilia will, duringtheir lifetime, develop antibodies to factor VIII that inhibit itsaction. Such inhibitors usually develop after the first fewtreatment doses of factor VIII. The prevalence of inhibitors is, however, only 5–10% because inhibitory antibodies developonly rarely in moderate and mild haemophilia and often disappearspontaneously or with continued treatment.Management of such patients may be very difficult, aseven extremely high doses of factor VIII may not producea rise in the plasma factor VIII level. Recombinant factorVIIa at very high ‘pharmacological’ levels can bypass factorIX/VIII activity in the coagulation pathway and is an effectivetreatment in more than 80% of bleeding episodes in patientswith high factor VIII inhibitor levels. Some factor IX concentratesare also deliberately activated to produce factors,which also may ‘bypass’ the inhibitor and stop thebleeding.

![Significance of Simultaneous Splenic Artery Resection in ... · portal hypertension (LPH), causing variceal bleeding and thrombocytopenia by hypersplenism [3, 4]. Variceal bleeding](https://static.fdocuments.net/doc/165x107/5f08c2047e708231d42393cb/significance-of-simultaneous-splenic-artery-resection-in-portal-hypertension.jpg)