Pitch Organization Scriabin

-

Upload

maria-cueva-mendez -

Category

Documents

-

view

246 -

download

2

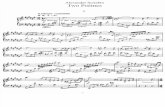

Transcript of Pitch Organization Scriabin

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 1/13

Volume 14, Number 3, September 2008Copyright © 2008 Society for Music Theory

Vasilis Kallis*

Principles of Pitch Organization in Scriabin’s Early Post-tonal Period: ThePiano Miniatures

KEYWORDS: Scriabin, piano miniatures, octatonic scale, acoustic scale, whole-tone scale, pitch substitution, genus transformation

ABSTRACT: Scriabin’s post-tonal period, which begins around 1909 with Feuillet d’album, Op. 58, is defined by the subtle and sophisticated

exploitation of some special non-diatonic sets and their pitch universes: (i) the acoustic scale: 0, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, t (member of set-class 7-34), the parent

scale of the Mystic Chord; (ii) the octatonic scale, Model Α: 0, 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, t (member of set-class 8-28); and (iii) 9-10: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, t (the

nine-note superset that arises from the union of the acoustic and the octatonic scales). Close examination of the post-Op. 58 works allows us topartition the late style into two periods: early, from Op. 58 to Op. 69 inclusive; and late, from Op. 70 to the final creation, Op. 74. During his early

post-tonal period, Scriabin developed a pitch organization method based on the interaction between the acoustic and octatonic scales within the

constraints of their nonachordal common superset 9-10. This essay examines the specifics and the application of the acoustic-octatonic interaction in

the composer’s miniature pieces written in his early post-tonal period.

Received June 2008

Dedicated to the memory of Anthony Pople

[1.1] Scriabin’s post-tonal period, which begins around 1909 with Feuillet d’album, Op. 58, is defined by the subtle and sophisticated exploitation of

some special non-diatonic sets and their pitch universes: (i) the acoustic scale: 0, 2, 4, 6, 7, 9, t (member of set-class 7-34), the parent scale of the

Mystic Chord;(1) (ii) the octatonic scale, Model Α: 0, 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, t (member of set-class 8-28); and (iii) 9-10: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, t (the nine-note

superset that arises from the union of the acoustic and the octatonic scales). (2) See Example 1. Close examination of the post-Op. 58 works allows us

to partition the late style into two periods: early, from Op. 58 to Op. 69 inclusive; and late, from Op. 70 to the final creation, Op. 74. During his early

post-tonal period, Scriabin developed a pitch organization method based on the interaction between the acoustic and octatonic scales within the

constraints of their nonachordal common superset 9-10. Other pitch entities appear as well, but their functional role is supplementary until they are

integrated into a coherent style in the Tenth Sonata, Op. 70, which marks the beginning of the composer’s final period.

Example 1. Scriabin’s primary pitch material

(click to enlarge)

[1.2] This essay considers Scriabin’s method of pitch syntax in his early post-tonal period (1909–12) through the examination of miniature piano

pieces. Since the composer was writing these to master his craft, they constitute valuable source material for the study of his pitch organization.(3)

[1.3] Scriabin’s method of pitch organization centers on the chromatic

possibilities available through the pitch relationship between the acoustic

(labeled as such for its similitude to the overtone series) and the octatonic

scales.(4) These closely related scales share a common hexachordal subset

(6-Z23), which allows the remaining pitches—one, D ( ), exclusively

acoustic, the other two, D ( ) and E ( ), exclusively octatonic—to dictate

the play of identity. Example 2 exemplifies the central motto in the

Example 2. Model of pitch organization in Scriabin

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 2/13

composer’s method of pitch organization. As can be seen, the acoustic and

octatonic scales are connected efficiently through a variable second scale

degree— in the acoustic and in the octatonic. The chromatic interplay

occurs within two distinct harmonic structures, the Mystic Chord (set-class

6-34) and its octatonic version, labeled Mystic Chord B (set-class 6-Z49), in

which and are realized as the ninth and the lowered ninth respectively.

Since and can be used to determine whether a segment of music is

acoustic or octatonic, they are classified henceforth as the acoustic and

octatonic indicators, respectively.

[1.4] Although there is more than one way to define the relationship between

9-10 and the acoustic and octatonic scales, Scriabin’s compositional practice

(which unequivocally treats the heptachord and the octachord as gestalts)

allows us to view 9-10 as the union of the pitch content of its two subsets

(Example 3).(5) In fact, 9-10 is the only nine-note superset of the octatonic

scale and the smallest common superset of the latter and the acoustic scale. It

constitutes the superset under the auspices of which the acoustic scale and the

octatonic scale, Model Α interpenetrate one another, and, additionally, its pitch

constraints form the chromatic pitch gamut of the phrase units that shape the

musical surface.

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. Generation of 9-10 from the union of

the acoustic and the octatonic scales

(click to enlarge)

[1.5] The pitch entities in Example 1 and all their subsets are treated not as abstract set-classes, but as specific ordered non-diatonic scales.“Ordered” means that a specific pitch center is imposed on which specific harmonies ( Mystic Chord, Mystic Chord B, and their variants) are built. In

Scriabin’s early post-tonal period, both the acoustic and the octatonic scales have their pitch center on the pitch on which the Mystic Chord and

Mystic Chord B, respectively, are built. This approach restricts the octatonic scale to one of its two rotations, semitone-tone, Van den Toorn’s Model

Α. The correlation with the specific pitch centricity refers not only to the acoustic and the octatonic scales, but also to their subsets employed in the

composer’s early post-tonal œuvre.

[1.6] Scriabin’s principles of pitch organization have preoccupied scholars from the first moment that his post-tonal works earned a place in the

twentieth-century repertory. It is particularly in the work of M. Kelkel, Anthony Pople, and Fred Lerdahl that we find apt analytical descriptions of

Scriabin’s octatonic/acoustic (and thus 9-10) ventures.(6)

[1.7] Kelkel realizes the structural significance of the composer’s

chromatic schemes in formalizing a language based on the exploitation of

different harmonic/modal types. The most significant of his observations isthe proposed distinction between two harmonic and modal types. The

Mystic Chord and Mystic Chord B correspond to the acoustic scale and the

octatonic heptachord 7-31 respectively (Example 4).

[1.8] Pople’s study of the Prelude, Op. 67, No. 1 presents a well-buttressed

effort to decode Scriabin’s peculiar octatonic practices, especially in

conjunction with 9-10, which Pople treats as a new normative set “regarded

as being composed-out against the normative background of the octatonic

set [0,1,3,4,6,7,9,10].”(7) Similarly to Pople, Lerdahl also correlates the

octatonic scale with 9-10, but in addition he brings the acoustic scale to the

fore. His analysis of Op. 67, No. 1 offers a precise description of the

relationship between the three scales and their role in Scriabin’s method of

pitch-organization.(8)

Example 4. Scriabin’s octatonic/acoustic transformations

(click to enlarge)

[1.9] The most significant aspect with regard to the history of the acoustic scale and 9-10 is not so much the lack of acknowledgment, but the failure

to realize the specifics of the dialectic between the acoustic and the octatonic scales, not least of the chromatic interplay between / .(9) This is a

result of widespread misconceptions that have their roots in essentially two factors: (i) the excessive weight placed on the whole-tone scale as pitch

material in Scriabin’s post-tonal period, and (ii) the failure to associate the Mystic Chord with the acoustic scale itself. Perhaps the overabundance of

whole-tone dominants in late nineteenth-century music brought about such misconceptions; certainly, Scriabin’s œuvre in 1903–9 abounds in

dominants with lowered or raised fifths. Nevertheless, the whole-tone scale’s prominent appearance in the composer’s transitional period does not

justify regarding it as a determinant of pitch organization in the post-tonal style. More to the point, the acoustic scale appears no less prominently in

the transitional period.

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 3/13

[1.10] This structure, for example, saturates the musical surface in the outer sections

of the Scherzo, Op. 46, a work well into the composer’s transitional period. Example

5 shows measures 1–4, which articulate two T 7 related phrases. Apart from the

downbeat of measures 2 and 4, the music unfolds a succession of a single type of

dominant harmony, a dominant seventh with a raised eleventh (set class 5-28), a

structure prophetic of the Mystic Chord (the E at the last eighth-note of the

incomplete introductory measure and the B at the last eighth-note of measure 2 are

non-harmonic notes). The particular excerpt is an early example of Scriabin’s later

practice of articulating dominant-type chords where the root is also tonic. Vital to

our present considerations is the full appearance of the scale exactly at the downbeatof measures 2 and 4: C acoustic and G acoustic respectively. These are points of

structural significance, because they constitute the boundaries of the first two

phrases, a momentary goal of what precedes them. The presence of C and G

acoustics as the pitch source of these structurally significant harmonies is surely not

accidental; it corroborates the emerging prominence of the acoustic scale in the

composer’s music.

Example 5. Scriabin’s primary pitch material

(click to enlarge)

Issues of pitch organization

The octatonic scale

[2.1] The octatonic scale is invariant at four distinct transpositional levels:

T 0, T 3, T 6, and T 9 will keep the pitch content of the scale intact. The

symmetrical properties of the scale are transferred within 9-10 as well: it

remains the symmetrical component of its superset, which is itself an

asymmetrical entity. In fact, the cyclical application of T 3 to 9-10 yields

quite interesting results that merit attention. It keeps the octatonic

component within 9-10 invariant. However, it brings forth a new pitch, the

second scale degree of the acoustic component, which is an extremely

important technical detail in Scriabin’s compositional approach. See

Example 6. This means that while the cyclical transposition of any 9-10 by

interval-class 3 will keep a single form of the octatonic scale intact, at the

same time it will yield four distinct 9-10s and four distinct acoustic scales.

These provide a “new” pitch at each transposition, which is none other than

the acoustic indicator. In addition, the three acoustic indicators found in theT 3, T 6, and T 9 forms of the original T 0 of 9-10 are the three pitches that,

when added to 9-10, bring about the complete chromatic aggregate.

[2.2] Scriabin’s method of pitch organization makes exclusive use of the

octatonic scale, Model Α, the rotation of 8-28 able to provide major and

minor triads (as well as other tertian harmonies) built on the first note of the

scale, which also lines up as closely as possible with the canonical ordering

of the acoustic scale. Of the many harmonic structures built on the tonic of

the octatonic scale, Model Α, Scriabin favors specific dominant-type, yet

tonally non-functional, extended and altered harmonies: more specifically,

Mystic Chord B, its variants, and some pentachordal subsets. See Example

7.(10)

Example 6. 9-10, T 3 operation

(click to enlarge)

Example 7. Octatonic scale, array of harmonies

in Scriabin’s post-tonal oeuvre

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

The acoustic scale

[2.3] The acoustic scale is a transpositionally asymmetrical entity; it is not invariant under any transposition. Its value in Scriabin’s pitch-syntactic

routines lies in its close pitch relationship with the octatonic scale, and in that it contributes the only non-octatonic pitch within 9-10, the acoustic

indicator.

[2.4] In addition to the variety of harmonic structures available within its

harmonic depository, the acoustic scale exhibits an explicit functional

distinction among its seven scale degrees. Scriabin, nevertheless, focuses on

a single scale degree, the tonic, and, similar to what he does with the

octatonic scale, utilizes only specific dominant-type extended and altered

structures, namely, the Mystic Chord and specific variants. See Example 8.

Example 8. Acoustic scale, array of harmonies in

Scriabin’s post-tonal oeuvre

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 4/13

The role of the Mystic Chord is essential, not only because of its special

status in the composer’s method of pitch organization, but also because the

acoustic and octatonic (especially Mystic Chord B) structures featured in

Scriabin’s post-tonal œuvre are directly related to it. The correspondence

between the voicing of the acoustic and the octatonic structures is probably

a result of the special emphasis given to the Mystic Chord as the emerging

harmonic foundation in the composer’s routines for pitch organization.(11)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.5] The acoustic and octatonic scales interact with one another by way of common subsets, a vital technical attribute in Scriabin’s method of pitch

organization. This approach promotes parsimonious voice-leading, which (i) ensures the smooth transformation from one scale to the other and (ii)permits the direct conflict between the members of the chromatic dyad formed by the acoustic and the octatonic indicators ( and , respectively).

However, it ought to be said that the interaction between the acoustic scale and the octatonic scale, Model Α is not limited to the interpenetration of a

heptachord and an octachord that share a common hexachordal subset. It is rather an interaction between two pitch genera that involves the specific

subsets referred to above and some specific common tetrachordal subsets (displayed in Figure 1 below) under the auspices of the common superset

9-10.

Figure 1.

(click to enlarge)

[2.6] How, then, do the peculiar interrelationships in the octatonic/acoustic universe make themselves available in Scriabin’s model of pitch

organization? The inspection of Scriabin’s approach to harmony places the Mystic Chord (6-34) and its octatonic version (6-Z49) at center stage.

Both of these harmonies remain basic to the composer’s harmonic palette and constitute the central point of harmonic reference in the early

post-tonal style. All the other harmonic structures deployed are directly related to this harmonic core. Several hexachordal variants are encountered:

two related to the Mystic Chord (6-34, 6-33), two related to Mystic Chord B (6-30, 6-Z50), and one common to both (6-Z23). Specific pentachordal

substructures are also articulated when the several forms of the Mystic Chord appear as incomplete sonorities. Harmonic structures with fewer than

five pitch members are deployed sparingly, if at all. These structures may appear, usually in the left hand, before other chord members enter

melodically in the right hand to form (by integrating the vertical with the horizontal) one or another of the composer’s trademark harmonies.

[2.7] The two pitch genera, as mentioned above, interact primarily through common structures. Figure 1 shows the specific details of this procedure.

Column 1 lists the acoustic structures. The column next to it displays the corresponding octatonic structures. The last column shows the common

acoustic/octatonic subsets that act as mediators in the specific interaction process. All the harmonic structures in columns 1 and 2 include the

acoustic/octatonic indicator ( / ), which is missing from the common acoustic/octatonic subset. Scriabin handles the / dialectic very subtly. His

harmonic structures unfold via the integration of the vertical with the horizontal, which constitutes a stylistic norm. However, the left hand deploys,

more often than not, a harmonic skeleton that rotates the root ( ), third ( ), seventh ( ), and raised eleventh ( ). This allows one of the upper

voices to conduct the chromatic interplay between the acoustic and octatonic indicators.

[2.8] Scriabin’s treatment of these pitch phenomena in relation to pitch organization prompts the following general observations:

The phrase structure is organized in chunks of music that constitute self-contained “blocks” in which the acoustic/octatonic structural

associations are articulated on a single pitch center. (These “blocks” form motivic segments or entire phrase units.) Motivic and thematic

designs, as well as the contrapuntal network that assures their interconnection, tend to emphasize the melodic argument between the two

members of the / chromatic dyad.

i.

There are four fixed scale degrees that are almost always present: , , , and . There are two other fixed scale degrees whose presence isii.

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 5/13

more irregular: and . There is one variable scale degree: or . In addition, if is used, can be used simultaneously with .

These “blocks” are usually transposed by either one of the two fundamental intervals (or their multiples) within the acoustic and the octatonic

genus: ic-2 and ic-3 respectively. Ultimately, a work’s transposition structure is used as a means to promote the presence of the acoustic scale,

the octatonic scale, and 9-10, at the deepest levels of structure. Scriabin’s transpositional levels tend to avoid the three pitches not present in

the pitch content of 9-10 (and, by convention, in the pitch content of the acoustic and octatonic collection as well), i.e. scale degrees , and

. The first two, in particular, are avoided because they have the potential to erode the peculiar aural characteristics of the composer’s

harmonic structures: the lowered seventh and the raised fourth. Scale degree is something of a special case. It bears no threat to Scriabin’s

peculiar sound quality; in fact, the raised fifth may enrich dominant-type harmonies in fruitful ways. It can be seen appearing at deeper levels

of structure, if not as a means to corroborate the surface articulation of the whole-tone scale, then as a source of a deeper-structure chromatic

conflict. For example, Op. 67, No. 1 and Op. 59, No. 2 present a transposition structure that promotes the presence of

G –G –A –A –B –C–E (member of the 9-10 subset 7-10) and C–C –E –F –G–A (member of the octatonic subset 6-30), respectively at

deeper levels of structure.(12) Op. 69, No. 1 promotes C–C –E –E –F –G–G –B (member of 8-27), which may be partitioned into the

octatonic heptachord (7-31) plus G ( ). Here, the presence of corroborates the surface articulation of the whole-tone pentachord (5-33).

(More on the articulation of 5-33 in Op. 69, No. 1, below.)

iii.

The persistence with which the specific dialectic between the acoustic and the octatonic scales appears in the composer’s early post-tonal

period suggests a remarkable syntactic unity. Moreover, the acoustic scale, the octatonic scale, Model Α, and 9-10, as well as the Mystic Chord

and Mystic Chord B, become conventionalized in the composer’s early post-tonal period through continual usage.

iv.

[2.9] Let us see how this approach works in practice. The opening phrase (mm. 1–3) of the Poème-Nocturne, Op. 61 immediately introduces a subtle

dialectic between the acoustic and the octatonic genera within the pitch constraints of superset 9-10. See Example 9. (Henceforth, we assign 0 to the

pitch center of the original phrase unit.) Scriabin introduces chromaticism in terms of the chromatic dyad formed by the acoustic and octatonic

indicators, E and E , respectively. Both substitute for each other above a recurrently arpeggiated D Mystic Chord variant (5-28:

D –F–G–B –C ). Since Scriabin keeps an incomplete D Mystic Chord as a common octatonic/acoustic subset in the left hand, the introduction of

E in measure 1 yields Mystic Chord B on D whereas E (m. 2) yields the Mystic Chord on the same pitch center.

[2.10] Identical acoustic/octatonic interpenetrations occur in the subsequent

phrase at measures 4–7, a modified T 2 transposition of the original phrase

unit (see Example 9). However, this time the incomplete introductory

measure of the T 0 unit becomes a full measure with the addition of a Mystic

Chord B variant whose pitches, despite the orthographical inconsistency, are

drawn exclusively from E octatonic, Model Α: E –F –F –A–B –C (

6-Z50). The raised ninth (F ) of this formation gives way to the lowered

ninth (F ) at measure 5 to begin the / conflict in terms of F/F . As in the

opening phrase unit, and even more intensified because of the distinct

octatonic harmony of measure 4, the music promotes the perpetual

alternation of the acoustic and octatonic “blocks.” The chromatic interplay

between the acoustic/octatonic indicators emerges gradually as a structural

issue; notice the melodic punctuation that emphasizes these two tones. The

initial E comes with a fermata, as does the F at measure 5, the analogous

pitch in the T 2 transposition of the opening phrase (mm. 4–7).

Example 9. Scriabin, Poème-Nocturne, Op. 61, mm. 1–7

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Voice-leading parsimony: a model of interaction

[3.1] The treatment of the acoustic and octatonic scales in Scriabin’s

method of pitch organization conforms to a broader network of set

interaction based on voice-leading parsimony between closely related

set-pairs of equal and unequal rank. This procedure promotes genustransformations by way of pitch substitution, pitch addition/omission,

and pitch splitting. The abstract relationships between Scriabin’s

preferred scales discussed below are presented in Clifton Callender’s

study of the composer’s voice-leading routines.(13) Consider Figure 2

(Callender’s Figure 11), which epitomizes the technical specifics of this

relational network in terms of the composer’s primary scales and three

important subsets: 7-31, 6-34 ( Mystic Chord), and 6-Z49 ( Mystic Chord

B). Horizontal connections involve set-pairs of equal cardinality, which

form the P1 relation with one another. As we see from the three

P1-related pairs (6-35/6-34, 6-34/6-Z49, 7-34/7-31), transformations

between them require nothing more than a single chromatic alteration (or

Figure 2. Substitution-based interaction: network of set

interrelationships, from Callender (1998, Fig. 11, p. 227)(14)

(click to enlarge)

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 6/13

pitch substitution). See Figures 2 and 3. A single pc is subjected to

alteration by ± 1 semitone to yield its substitute and effect the scalar

transformation.

Figure 3. Voice-leading between P1-related sets

(click to enlarge)

[3.2] The first two measures of Poème-Nocturne, Op. 61 (Example 9

above) are a paradigm of this kind of interaction; they exhibit a

transformation from 6-Z49 ( Mystic Chord B on D ) to 6-34 ( Mystic

Chord on D ) through the substitution of E by E . A similar

interaction between 6-34 and 6-Z49 occurs in Op. 69, No. 1 as well.

See Example 10a. Measures 1–2 juxtapose the Mystic Chord and its

octatonic version on C via the melodic conflict between / in terms

of D and D respectively: C– D –E–F –A–B → C– D –E–F –A–B .

T 4 (mm. 5–6) juxtaposes the Mystic Chord and Mystic Chord B on E.

There also exist transformations between 6-34 and the second set with

which it forms the P1-relation, 6-35 (Example 10a and 10b). The 6-35on A (A –B – C –D–E–G )—actually a whole-tone version of the

Mystic Chord —of measure 3 is replaced, via the substitution of C

with C , by 6-34 ( Mystic Chord) on E (E–F –G –A – C –D).(15)

Another such transformation occurs between the C Mystic Chord of

measure 2 and the 6-35 of the following measure, but the octatonic

indicator D obscures the clarity of the particular association.

[3.3] Vertical set connections in Figure 2 involve sets related by

inclusion. This means that their interconnections do not require any

pitch inflections, but are carried out by pitch addition or pitch

omission. Sets connected vertically are representatives of the same

pitch genus, be it octatonic or acoustic. The decision as to which set

(the inaugural set or specific subsets) is used at the musical surfacerelies on contextual requirements. The octatonic heptachord of the

first two measures of Etrangeté , for example, is succeeded by 6-Z49,

which eliminates (E ), to render the upcoming acoustic/octatonic

interaction possible (Example 11).

[3.4] Sets connected diagonally (from the upper left to the lower right

corner) form the S-relation, which involves sets with a cardinality

difference of ±1 (see Figure 2 above). S splits a pc to yield its upper

and lower chromatic neighbors and vice versa. Three pairs

(6-35/7-34, 6-34/7-31, and 7-34/8-28) are S-related to one another.

Figure 4 demonstrates the abstract manifestation of this type of

interpenetration. However, due to his approach to pitch organization,

Scriabin does not particularly exploit the S-relation in the miniaturesof his early post-tonal period. As seen in Figure 4, the S-relation

involving the pairs 6-34/7-31 and 7-34/8-28 requires the presence of

and in the octatonic structures. Given the fact that the

articulation of prevents the construction of common

acoustic/octatonic subsets, the simultaneous appearance of and

(instead of and ) becomes a much less viable option.(16)

Example 10a. Scriabin, Poème, Op. 69, No. 1, mm. 1–6

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 10b.Scriabin, Poème, Op. 69, No. 1, mm. 1–5,acoustic/whole-tone interaction

(click to enlarge)

Example 11.Scriabin, Etrangeté, Op. 63, No. 2

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Figure 4. Voice-leading between S-related sets

(click to enlarge)

[3.5] What Scriabin promotes instead is the combination of vertical (inclusion) and horizontal (P1) motion shown in Figure 2. This operation

involves sets with a ±1 difference in cardinality and incorporates the / interaction, but instead of the S-relation, we observe the combination of

pitch substitution and pitch addition/omission. Pitch substitution and omission may be seen at measure 3 in Etrangeté , Op. 63, No. 2 (Example 11

above). Here, the octatonic heptachord (7-31) of the first two measures prepares the ground for the upcoming interaction with the acoustic genus.

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 7/13

Measures 1–2 unfold 7-31 on C (C Mystic Chord B + pitch D ) and its T 9 form (A Mystic Chord B + pitch C), respectively. The first beat of measure

3 restores the original T 0 form but without E , which is the only pitch whose exclusively octatonic orientation could jeopardize the upcoming

interpenetration—it is certainly not accidental that the reduction from 7-31 to 6-Z49 occurs immediately before the octatonic/acoustic dialectic

begins. Scriabin, then, promotes the brief oscillation between octatonic and acoustic structures. Mystic Chord B (6-Z49: C–D –E–F –A–B )

interacts with the acoustic pentachord 5-33 (C–D –E–F –B ), enforcing pitch substitution (D replaces D ) and pitch omission (the A from 6-Z49 is

removed in 5-33).(17)

[3.6] An important issue as to the nature of the pitch interrelationships within 9-10 emerges at this point. Does the music effect the juxtaposition of

the acoustic and the octatonic scales by means that promote pitch substitution in terms of and or does it suggest combination (the deployment

of 9-10 as a gestalt and not as the mere sum of the union of the acoustic and the octatonic scales)? Scriabin’s persistent use of chromatic dyads as themeans to achieve scalar transformation places the principle of pitch substitution at center stage. The interaction between the acoustic and the

octatonic scales is conducted primarily through the / chromatic dyad as it emerges within the framework of specific harmonic formations.

Reference to harmonic membership implies that the specific interactive process is fundamentally a contrapuntal phenomenon in which the 9 ( ) of

Mystic Chord B and of any Mystic Chord B variant substitutes for the 9 ( ) of the Mystic Chord and of any Mystic Chord variant and vice versa.

Thus, this chromaticism is structural.(18) Remarkably, Scriabin uses / chromaticism exclusively. Decorative “non-diatonic” chromatic tones

(pitches that fall outside the domain of 9-10) are deployed sparingly; one such instance occurs in Op. 59, No. 2, where the passing tone B at the

downbeat of measure 2 resolves to B , a member of the governing 9-10 on C.

[3.7] Two technical details show that pitch substitution constitutes a fundamental feature of Scriabin’s method of pitch organization: (i) in his

approach to voice-leading, the acoustic and octatonic indicators are always treated as adjacencies in the same voice; and (ii) certain pitches are

selectively and systematically omitted from the pitch content of adjacent, transpositionally related, phrase units . Let us see how this is practiced in

Op. 61 (Example 9 above). The sum of the pitches of T 0 yields the 9-10 octachord 8-27: D –E –E –( )–F–G–A –B –C . E ( ) is missing, a fact

which serves the composer’s intentions in two ways. First, it clears the path for the desired cross-collectional interaction. E is a pitch that woulderode any acoustic/octatonic interpenetration. Had it been present, it would not have been possible to articulate an acoustic “block.” Secondly, its

absence in one transposition (T 0) only serves to emphasize its prominence as a member of the structural chromatic dyad in the following one. As

shown in Example 9 above, the E missing from T 0 emerges as the octatonic indicator in the chromatic dyad F–F of T 2 (mm. 4–7):

E – F – F –F –G–A–B –C–D (T 2 adds a harmonic structure at the downbeat of measure 4 that features the missing pitch of the localized

transposition of 9-10, F ). Furthermore, observe Scriabin’s enharmonic spellings. The octatonic indicator asserts itself as the indisputable inflection

of its acoustic counterpart: E to E in T 0, F to F in T 2 and G to G in T 4.

[3.8] The emphasis on the conflict between the two modal indicators

emerges as a crucial compositional device. In fact, inspection reveals that,

in his effort to allow at least one of the two modal indicators to appear as a

“new” pitch, Scriabin enforces a plan that promotes the correlation between

pitch content and transposition interval. See Table 1. In the T 3, T 6, and T 9

operations, the acoustic indicator ( ) is not present in the original (T 0) formof 9-10; it always articulates itself as a “new” pitch, as does the octatonic

indicator ( ) in T 4. (The acoustic indicator is, in fact, the only new pitch,

which is why ic-3 transpositions have a privileged status in Scriabin’s

post-tonal period.) However, in the case of T 2, both the acoustic and

octatonic indicators are present in the T 0 form and one or both need to be

removed in order to achieve the specific melodic emphasis. Given that ,

as noted above, is the only pitch that could jeopardize the acoustic/octatonic

(via / ) interaction, its omission is preferred over the omission of the

acoustic indicator (in T 2), which stands for the third of the Mystic Chord in

the original T 0 form.

[3.9] Poème-Nocturne, Op. 61, Op. 63, No. 2, the prelude from Op. 59, and

Op. 69, No. 1 exemplify this approach. Poème-Nocturne begins with the9-10 octachord 8-27 on D : D –E –E –(F )–F–G–A –B –C . This T 0

phrase unit is replaced by 9-10 on E , T 2: E – F –F –G –G –A–B –C–D .

See Example 9 above. The octatonic indicator in T 2, F , is missing from T 0.

It would have been possible to exclude F ( ), the acoustic indicator,

instead of F . However, Scriabin would then erode the ground on which

these subtle interrelationships are built, i.e. the Mystic Chord, which, in the

absence of its third (F in T 0), loses identity and meaning.

[3.10] However, in Op. 63, No. 1 the change to a different transposition

interval (ic-3) dictates a different approach. See Example 12. The acoustic

indicator in T 3 is, by convention, a “new” pitch (it is the only pitch in T 3

Table 1. Scriabin, Poème, Op. 69, No. 1, mm. 1–6

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 12. Scriabin, Masque, Op. 63, No. 1, mm. 1–4

(click to enlarge)

Example 13. Scriabin, Prelude, Op. 59, No. 2, mm. 1–5

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 8/13

missing from T 0). Hence, in order to find common harmonic ground

between the acoustic and the octatonic scales, Scriabin simply removes the

other exclusively octatonic pitch E ( ) from T 0. The melodic emphasis on

the / chromatic dyad would have been more salient had E, , been

missing from T 0. However, as in the case of Poème-Nocturne, that would

have eroded the harmonic quality of the Mystic Chord.

[3.11] In contrast, in the Prelude, Op. 59, No. 2, in T 0 is missing

(Example 13). Yet that particular work is something of a special case. It is

Scriabin’s first work to incorporate the octatonic scale; hence, it is not fullyin line with later works with respect to harmony and transpositional

structure. For one thing, the harmonic structures do not conform to the

interactive specifics displayed in Figure 1 above. The emergence of the

exclusively octatonic (E in T 0), combined with the absence of (E in

T 0), deprives the articulated harmonies of their dominant quality. This

creates an aural atmosphere that is peculiar to the piece. In addition, the

transpositional structure is more rigid than that of subsequent works. The A

section of the rondo design (ABABA) is governed by the transposition of

the initial phrase unit through the minor-third cycle, promoting the

systematic unfolding of the acoustic indicator: D in T 0, F in T 3, G in T 6,

and B in T 9:

(click to enlarge)

T 0: C–D – D –E –F –G–A–B T 3: E –F – F –G –A–B –C–D

T 6: F –G– G –A –B –C –D –E

T 9: A–A – B –C–D –E–F –G

T 12: C–D – D –E –F –G–A–B

[3.12] Now consider T 4. Opus 69, No. 1 (Example 10a above) provides a paradigmatic example of how this particular operation lays emphasis on

the / chromatic dyad. Measures 1–8 involve two T 4-related four-measure phrases. What interests us here is the first half of each phrase, which

unfolds the acoustic/octatonic interplay on pitch centers C and E, respectively. T 0 (mm. 1–2) carries the 9-10 heptachord 7-26

(C–D –D –E–F –A–B ) formed by the common acoustic/octatonic pentachord 5-28 and the acoustic/octatonic indicators D/D , respectively. The

T 4 of measures 5–6 unfolds as E– F –F –G –A –C –D (7-26 formed similarly to T 0). Missing from T 0 by convention ( represents one of the three

pitches absent from 9-10), the octatonic indicator F articulates itself as a “new” pitch, and although the two T 4-related phrases are not adjacent

(mm. 3–4 carry the interpolation of the whole-tone pentachord 5-33), the effect is still audible.

[3.13] The concluding stages of Poème-Nocturne, Op. 61 provide further

evidence of the compositional value of the / chromaticism; measures

159–72 bring about a perpetual oscillation of acoustic and octatonic

“blocks.” The Mystic Chord on D of measure 159 initiates the dialectic

with a Mystic Chord B variant (6-Z50: D –E –F–G–A –B ), the latter

configured so as to maintain focus (through voice-leading) on the E /E

structural chromatic dyad (Example 14).

[3.14] To further intensify the effect, Scriabin deprives the octatonic

indicator of its harmonic clothing: in the last six measures, E alone

interacts with the acoustic “block.” This particular tone, which is the

lowered ninth of a chord with a very strong octatonic orientation, maintains

enough harmonic weight from its membership in the Mystic Chord Bvariant of measures 160–62 and 164–66 to effect a change of genus. The

closure manifests the structural role of the present chromaticism.

[3.15] In contrast, the Prelude, Op. 67, No. 1 features segments that resort

to combination. Pople demonstrates that the vast majority of the proposed

segments are governed by superset 9-10 or by specific 9-10 subsets. (19)

Our concern here is with the pitch content and pitch interrelationships in

terms of the acoustic and octatonic scales within each segment. Measures

1–6 and 15–16, taken as samples (every measure constitutes a segment

here), present the following set successions (Example 15):

Example 14. Scriabin, Poème-Nocturne, Op. 61, mm. 159–72

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Figure 5.

(click to enlarge)

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 9/13

Example 15a. Scriabin, Prelude, Op. 67, No. 1, mm. 1–6. Based on

Pople(20)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 15b. Scriabin, Prelude, Op. 67, No. 1, mm. 15–16

(click to enlarge)

[3.16] The first six segments (mm. 1–6) are governed by the T 0 form of 9-10: G –G –A –A – B –C–D –E –F . Note that, in Op. 67, No. 1, the

acoustic indicator (A in T 0) is the pitch that initiates every transposition of 9-10 (“each statement of this extra pc, at whatever transposition of 9-10,

initiates melodic motion”).(21) Measures 1 and 2, which are identical, are governed by 9-10 itself, and measures 3–6 are governed by 9-10 subsets:

measures 3 and 5 by 8-12, measure 4 by 6-Z50, and measure 6 by 7-31, all at T 0.(22) Measures 15 and 16 are governed by 8-27 and 7-31 at T 10

(Example 15b). Two of the eight units (mm. 1 and 2) seem to conform to the principle of pitch substitution: they juxtapose 6-34 with 7-31, two

distinct acoustic and octatonic subsets. The acoustic/octatonic indicators may not be adjacent, but Scriabin’s voice-leading keeps them in the same

voice. Three segments feature either a single octatonic subset (6-Z50 at m. 4), or successions of octatonic subsets: 5-19 → 7-31, 7-31 → 6-30 at

measures 6 and 16, respectively. However, the remaining segments present something worthy of special attention: acoustic/octatonic hybrids,

set-types 6-21 and 8-27, especially the latter, which articulates (F) and (F ) in the same harmonic structure simultaneously. These segments

feature structures that are subsets of 9-10 but not of 7-34 or 8-28. Here, the organization of pitch structure points to combination. Note that the

presence of these hybrids is not exhausted in measures 3, 5, and 15. 6-21 and 8-27 appear twelve and four times, respectively, throughout the

score.(23)

[3.17] A similar approach is encountered in Op. 59, No. 2. See Example 13 above. T 0 (the opening phrase unit at mm. 1–5), utilizes the 9-10

octachord 8-18: C–C –D–E –F –G–A–B (the B is a non-harmonic tone). The acoustic indicator, D in the opening (T 0) phrase unit, unfolds

within a harmonic framework that includes (E ) instead of the octatonic indicator D : C–D–E –G–B .(24) The latter appears in the following beat

surrounded by C, the pitch center of the initial T 0 phrase unit. This scheme repeats itself in the subsequent transpositions of the primary phrase unit.

The presence of the exclusively octatonic pitch E , along with the registral separation of the acoustic and octatonic indicators, rules out pitch

substitution in favor of combination.

[3.18] We may draw the following conclusions regarding Scriabin’s approach to pitch organization. Pitch substitution, and thus structural

chromaticism in terms of the chromatic dyad / , plays the leading role in Scriabin’s pitch-syntactic routines. However, combination also has a

significant role to play. In addition, one sees phrase units formed by unadulterated octatonic or acoustic structures.

[3.19] Pitch substitution involves either “blocks” that bear the distinctive aura of their parent scale (i.e., Op. 61, mm. 159–72) or structures that are

subsets of both 7-34 and 8-28, which leave the play of identities to the acoustic/octatonic indicators (i.e., Op. 61, mm. 1–7, Op. 69, No. 1, mm. 2 and

6). This invites a welcome dialectic that produces a well-controlled, subtle, perpetual change or mixture of “color.” In that sense, chromaticism,

subtle as it is, acts not only as an agent of modal mutation, but above all as a primary compositional determinant with respect to the idea of

development, the idea of “change” and “progress.”

Pitch material and form

[4.1] With the exception of Op. 61, all of the piano miniatures that Scriabin wrote in the early post-tonal period are cast in part forms: binary, ternary,

and rondo. With regard to large structure, these forms exhibit two primary formal functions: (i) development (embedded within the motion away

from and back to the primary “tonality”), which includes motivic and thematic development to varying extents, and (ii) contrast, which dependslargely on harmonic and tonal/modal “change.” In the tonal era, “change” was principally accommodated by the modulation from one tonal center to

another, subject to context. In twentieth-century music, composers also relied on cross-collectional interaction, which usually involves more than

two scales and, more importantly, provides an effective means to emphasize the individual “color” imposed by each scale’s unique interval content.

The correlation between genus and formal unit is an important form-determining device, as exemplified in Richard Park’s analytical work on

Debussy.(25) In the piano prelude Feuilles mortes, for example, “each formal unit is associated with one or another genus.”(26) However, in contrast

to composers such as Debussy, Stravinsky, Bartók, and Ravel, Scriabin does not shift between scales at the beginnings of new sections. His

“modulations” rarely pursue the distinction of character between formal boundaries that are found so often in early twentieth-century repertories.

Instead, he largely relies on a subtle cross-collectional dialectic on a single pitch center within the phrase unit that is accommodated by pitch

invariance and intensified by / chromaticism.

[4.2] In addition, at the local level, decorative chromatic tones appear very sparingly. One of these is the B (mm. 2 and 4) in the Prelude, Op. 59, No.

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 10/13

2 (see Example 13 above), which is an accented passing tone that falls out of the pitch domain of the local reference scale. The insertion of

chromatic tones within principal melodic statements, not to mention modulatory passages of any kind, has for centuries been an extremely

resourceful means of elaboration in modal, tonal, or post-tonal contexts. On several occasions, if not in several styles, it has also been a structural

arbiter of such basic musical parameters as harmony, phrase structure and form.(27) Thus, constraining the pitch content of each phrase to a

maximum of nine pitches has a radical effect on musical meaning. In one sense, Scriabin not only employs limited pitch resources (single-type

harmonies on a single scale degree), he also appears to deprive his music of the widely applicable techniques of pitch elaboration that would

compensate for any loss of interest.

[4.3] Why then does Scriabin refrain from such a powerful compositional resource? In fact, he does not. The lack of a correlation between genus and

formal unit and the absence of the chromatic aggregate within the local phrases are balanced by a subtly articulated transpositional modus operandithat exploits pitch content and transposition interval to ensure the presence of either the acoustic or the octatonic indicator as “new” pitches at the

various transpositions of the original phrase unit. At the same time, the / melodic argument is imbedded very carefully within a sophisticated

motivic network in ways that perpetually maintain melodic emphasis.

[4.4] In addition, while the pitch total of phrase transpositions very rarely exceeds the pitch gamut of 9-10, Scriabin’s approach allows the music

ultimately to unfold the chromatic aggregate in a procedure that operates beneath the musical surface. The whole operation spans longer chunks of

musical time, in which the acoustic indicator provides the three missing pitches at T 3, T 6, and T 9; occasionally, such chunks govern an entire

composition, as in the case of Op. 59, No. 2. Structural chromaticism, both local and far-reaching, along with the gradual unfolding of the chromatic

aggregate, offers an effective means to overcome the constraining aspects of Scriabin’s pitch resources. To continue with the same line of thought,

the occasional interpolation of whole-tone “blocks” invites a welcome change of “harmonic color.”

[5.1] The present article proposes an analytical model as a means to decode the methods of pitch syntax practiced by Scriabin in his early post-tonal

period. It aims to present an ample and coherent exegesis of the many peculiarities that characterize Scriabin’s musical idiom. The development of

this particular analytical model has been based on its consistent manifestation in the miniature piano pieces between Opp. 59 and 69, inclusive.

Inspection reveals that Scriabin persistently insists on the specifics of the acoustic/octatonic argument. One can observe it saturating the musical

surface in Op. 59, Nos. 1 and 2, Opus 61, Op. 63, Nos. 1 and 2, Op. 65, No. 2, Op. 67, No. 1, and Op. 69, Nos. 1 and 2. The acoustic/octatonic

argument is also a principal feature in Op. 65, Nos. 1 and 3 and Op. 67, No. 2.(28) Nevertheless, it is integrated within the broader syntactic scheme

that appears fully developed in the Tenth Sonata, the first work of Scriabin’s final post-tonal period.

[5.2] The persistent use of the acoustic/octatonic argument suggests more than just the integrity of the proposed analytical model. Acting as an

arbiter of cohesion in the composer’s early post-tonal period, it reveals a remarkable unity of style, a style that is unique because of the ingenuity

with which its primary ingredients are intermingled. Scriabin is not alone in deploying stock-of-the-day pitch material. The Russians and other

Eastern Europeans, as well as the French, had been using the octatonic, the whole-tone, and the acoustic scales well before their initial appearance in

Scriabin’s œuvre. What distinguishes Scriabin from his contemporaries is the method he devises to exploit his primary pitch resource, in particular

the / chromaticism that remains at the core of the acoustic/octatonic argument.

[5.3] The use of chromaticism, either in terms of and its inflection or of other chromatic counterparts, which remains conspicuous in every stage of

the composer’s stylistic evolution, constitutes a vital technical attribute. This kind of pitch-syntactic consistency raises the possibility that the

analytical model that was intended to cope with the pitch issues within the early post-tonal miniatures could also be applicable to the composer’s

entire post-tonal œuvre.

Return to beginning of article

Vasilis KallisUniversity of Nicosia46, Makedonitissas Ave.P.O. Box 240051700 Nicosia - CYPRUS

Return to beginning of article

References

1. The Mystic Chord, as such, was first introduced in Prometheus, Op. 60. It constitutes Scriabin’s harmonic trademark and its presence spans the

composer’s entire post-tonal period.

Return to text

2. Since all the pitch entities in Scriabin’s pitch organization method appear in canonical ordering, the term “scale” is employed in preference to

“collection” or “set” or any other term of similar meaning that may be found in the set-theoretic literature.

Return to text

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

e 13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 11/13

3. Most of Scriabin’s miniature works explore the potential of new pitch material and/or deal with particular issues of pitch organization. See James

Baker, The Music of Alexander Scriabin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), ix. Many of the miniatures, in fact, are directly related to his

larger works. For example, Feuillet d’album, Op. 58, is a harmonic and “tonal” microcosm of Prometheus, Op. 60. See Fabion Bowers, The New

Scriabin: Enigmas and Answers (Norton Abbot: David and Charles, 1974): 78, and James Baker, “Scriabin’s Implicit Tonality,” Music Theory

Spectrum 2 (1980): 2. Poème, Op. 32, No. 2 and Poème Tragique, Op. 34 were to be included as arias in an opera that was never completed (see

Bowers, The New Scriabin, 47), while the two miniatures of Op. 73 were studies for Scriabin’s unfinished large work, the Mysterium. See Fabion

Bowers, Scriabin: A Biography of the Russian Composer, 1871–1915, 2 vols. (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1969), 2:264.

Return to text

4. The term “acoustic scale” refers to a scale whose pitch content resembles the first 14 partials above a given fundamental in the overtone series.

Since the specific scale appears as primary pitch material in the music of several important twentieth-century composers, a nickname seems more

convenient than simply referring to it as a numbered rotation of 7-34.

Return to text

5. Another way to perceive 9-10 is to see it as the extension of the octatonic scale by a single pitch, the only one that allows the acoustic scale to

resist full octatonic assimilation: 9-10 = C–D –E –E –F –G–A–B + D .

Return to text

6. M. Kelkel, Alexandre Scriabine: Sa vie, l’esotérisme et le langage musical dans son œuvre (Paris: Honoré Champion, 1978); Anthony Pople,

“Skryabin’s Prelude Opus 67, No. 1: Sets and Structure,” Music Analysis 2/2 (1983): 151–73; Fred Lerdahl, Tonal Pitch Space (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2004). The following three authors argue for a predominantly octatonic construction, combining it with the whole-tone, rather than

the acoustic scale: Jay Reise, “Late Scriabin: Some Principles behind the Style,” 19th-Century Music 6/3 (Spring 1983): 220–31; George Perle,

“Scriabin’s Self-Analysis,” Music Analysis 3/2 (1984): 101–22; James M. Baker (The Music of Alexander Scriabin). The octatonic scale features

centrally in Cheong Wai-Ling as well: “Orthography in Scriabin’s Late Works,” Music Analysis 12/1 (1993): 47–69; and “Scriabin’s Octatonic

Sonata,” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 121/2 (1996): 206–28. Wai-Ling not only refers to the scalar structure from which the Mystic

Chord derives its pitches (6-34, probably the best-known subset of the acoustic scale), but goes on to realize the significance of the dialectic between

the Mystic Chord and Mystic Chord B (6-Z49) in the composer’s pitch-organization method. 6-34 is also referred to in relation to Scriabin by Jim

Samson in Music in Transition (London: J. M. Dent, 1979): 207–10, and Baker in The Music of Alexander Scriabin.

Return to text

7. Pople, “Scryabin’s Prelude,” 151–73.

Return to text

8. Lerdahl, Tonal Pitch Space, 321–33. Lerdahl sees the acoustic and octatonic scales as subsets of 9-10, and the latter as the governing pitch entity

of the work.

Return to text

9. We should note that such associations are not exclusive to Scriabin. Some ten years before the composition of Op. 59, Debussy was able to adopt

and exploit these octatonic/acoustic modalities as part of his array of compositional resources in Nuages. For a detailed discussion of the dialectic

between 7-34 and 8-28 within the constraints of superset 9-10, see Vasilis Kallis, “Modes of Cross-Collectional Interaction: A Study of Four Scales

in Music by Debussy, Ravel and Scriabin” (Ph.D. diss., University of Nottingham, 2003): 397–98 and 442–45.

Return to text

10. The pitches in the harmonic structures in Examples 7 and 8 are spaced in a manner that reflects their usage by Scriabin, who, more often than

not, positions the raised fourth and the lowered seventh directly above the root.

Return to text

11. Wai Ling correctly observes that “Scriabin’s exploration of octatonicism probably took the ‘mystic chord’ as its point of departure.” See

“Orthography in Scriabin’s Late Works,” 63.

Return to text

12. The saturation of deeper levels of structure by pitch entities that monopolize the musical surface in Scriabin’s late œuvre is discussed by Pople in

his analysis of Op. 67, No. 1, in which he demonstrates that the transpositional route of the 9–10 units yields 7–10, a subset of the T 0 form of the

governing superset 9–10: “the transpositions of 9–10 found in the piece as a whole are, in order: t=0, 9, 7, 10, 8, 6, 9, 3, 0. These transposition

numbers — representing in each case a referential pc in the set — themselves form the the unordered set [0, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10], which is a subset (!) of

the t0 form of the normative set. The interpretation thus proposes that the normative set governs its own transpositions.” See Pople, “Skryabin’s

Prelude, Op. 67, No. 1,” 171.

Return to text

13. Clifton Callender, “Voice-Leading Parsimony in the Music of Alexander Scriabin,” JMT 42/2 (Fall 1998): 219–33.

Return to text

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

e 13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 12/13

14. Ibid., p. 227

Return to text

15. Reise advocates a whole-tone interpretation of Op. 69, No. 1: “Throughout the opening eight measures of the piece, one is struck by the

whole-tone sound of the music (C/D/E/F /G /A : abbreviated WT1), despite the fact that most of the remaining tones (A, D , E , F) are to be found

in mm. 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 8. With the presence of so many foreign tones it might seem unlikely that a whole-tone analysis would produce a

satisfactory description of the sound, but if we examine the situation a bit more closely, we see that Scriabin treats these foreign tones as ‘chromatic’

to the whole-tone scale, and almost always ‘resolves’ them in the traditional fashion—by half step.” See Reise, “Late Scriabin: Some Principles

Behind the Style,” 223. In advocating a whole-tone interpretation, Reise demotes the essential functional role of the Mystic Chord: “the mystic chord

then is a characteristic vertical sonority derived from the French Sixth, but, as we shall see, it is not the principal element in the process of pitch

generation.” Ibid, p. 223. Owing to its systematic usage, the Mystic Chord, which is unequivocally Scriabin’s most essential harmonic structure,

achieves conventional status in his post-tonal œuvre. Each and every one of this hexachord’s pitches, then, acquires normative status by convention.

Hence, to question the status of any of these six pitches means to question the conventional status of the Mystic Chord itself. An exclusively

whole-tone interpretation would be feasible only if there were whole-tone saturation not only of the musical surface, but also of deeper levels of

structure. In Op. 69, No. 1, one finds instances (e.g., mm. 3–4) where the musical surface is indeed saturated with the “whole-tone sound,” but they

function as temporary relief from the sound of the governing pitch entity. (However, with respect to saturation, observe the substitution of

F with E at measure 4, which converts the A whole-tone scale into the Mystic Chord on the same pitch, inserting another structural chromatic

dyad, / , which is exploited in the post-Op. 69 works.) Besides, the acoustic/octatonic exegesis takes care of most of Reise’s “foreign” pitches at

once. In the Poème, the Mystic Chord and its octatonic version accommodate not only the issues of the principal C centricity but of the majority of

the pitch centricities visited as well.

Return to text

16. Additionally, the presence of , in the absence of , would jeopardize the dominant quality of Mystic Chord B (the harmonic foundation of the

octatonic genus in Scriabin’s pitch-organization method) and its variants.

Return to text

17. The alternation between 5-33 and the octatonic pentachord 5-32 (C–D –E–F –A) in measure 3 is a variation of the P1-relation: D substitutes

for D , but at the same time A (in 5-32) replaces B .

Return to text

18. In the context of Scriabin’s method of pitch organization, the term “structural” is intended to reflect two things: (i) that the members of the /

chromatic dyad (or any other chromatic dyad which dictates any potential play of modal identities) are essential rather than decorative, and (ii) that

the particular dyad plays a fundamental role in the direct juxtaposition of two distinct pitch entities and their respective pitch genera.

Return to text

19. Pople, “Skryabin’s Prelude,” Example 13, p. 169.Return to text

20. Example 15 is based on Examples 2 and 6 from Pople (“Skryabin’s Prelude,” Example 2, p. 156 and Example 6, p. 162).

Return to text

21. Pople, “Skryabin’s Prelude,” 171.

Return to text

22. For more on the transpositional structure of Op. 67, No. 1, see Pople (“Skryabin’s Prelude”) and Lerdahl ( Tonal Pitch Space, particularly pp.

324–25).

Return to text

23. See Pople, “Skryabin’s Prelude,” 166.

Return to text

24. It is possible that this may be attributed to the “irregularities” surrounding Op. 59, No. 2 mentioned before. Yet, that particular presumption

aside, the passage displayed in Example 13 unequivocally resorts to combination.

Return to text

25. Richard Parks, The Music of Claude Debussy (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983).

Return to text

26. Ibid., p. 79.

Return to text

27. See, for example, J. Lester, “Robert Schumann and Sonata Forms,” 19th-Century Music 18/3 (Spring 1995): 189–210; Henry Burnett, “Linear

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14

e 13 31/10/1

8/14/2019 Pitch Organization Scriabin

http://slidepdf.com/reader/full/pitch-organization-scriabin 13/13

Ordering of the Chromatic aggregate in Classical Symphonic Music,” Music Theory Spectrum 18/1 (Spring 1996): 22–50; and James Baker,

“Chromaticism in Classical Music”, in Music Theory and the Exploration of the Past , ed. Christopher Hatch and David W. Bernstein (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1993): 233–307.

Return to text

28. Excepting measure 9, the remaining miniature of the early post-tonal period, Op. 58, is governed by 6-34. See chapter 3 in Anthony Pople,

Studies in Theory and Analysis: Skryabin and Stravinsky 1908–1914 (New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1989).

Return to text

Return to beginning of article

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2008 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online ( MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and

stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be

republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the

items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME,

EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee

is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of

the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or

distributed for research purposes only.

Return to beginning of article

Prepared by William Guerin, Editorial Assistant and Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Updated 19 September 2008

Number of visits: 4,188

O 14.3: Kallis, Principles of Pitch Organization in Scri... http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.3/mto.08.14