Pimlott Picturing Territories

-

Upload

maria-celleri -

Category

Documents

-

view

44 -

download

0

description

Transcript of Pimlott Picturing Territories

-

-lililllil 3 1822 03454 7349

Mark Pimlott

Without and within essays on territory and the interior

-

Contents

Without and within: an introduction 9

Picturing fictions 15

Picturing territories 59

Territory and interior: United States 1880-1939 111

Territory and interior: United States after 1945 175

Prototypes for the continuous interior 243

Only within 271

-

The templum of the Earth. Herzog August Bibliothek WolfenbOttel: Cod. Guelf. 36.23 Aug. 22, Bl. 41v (Corpus agrimensorum Romanorum) from Joseph Rykwert The Idea of a Town: the Anthropology of Urban form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World (Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press 1976)

1. Joseph Rykwert, The Idea of a Town: the Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World (Pr inceton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1976)

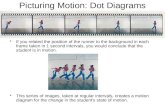

Picturing territories

It is difficult, sitting at a desk in a room in a house in a traditional European city, to imagine what the experience of a frontier might actually be: what it would be like to confront a place at the limit of what has been known, a place that is not a place, that is unknown. It would be quite unlike the experience one might have when finding oneself in an unfamiliar neighbourhood or some remote place having been dropped off by a coach. In this latter instance, the prospect of finding someone to provide guidance as to how to reach civilisation would be always available; there would be the road along which the bus continued its journey; there would be traces of human action, of urbanisation. At a frontier, there would be no such indexes, no roads, no signs, no cities, no places, no names. Such a situation offers two alternatives: retreat or appropriation. It is this last course that sees the imagining, naming, marking and making of territory.

It is difficult, too, to imagine that such a condition could ever have existed for the thoroughly urbanised European environment. Yet, this situation of beginning that pertains to each new settlement has marked the development of all civilisations, including this Western, urban civilisation of today. One understands the traditional European city as an accumulation of spaces.dedicated to habitation, collective activity, public life and civic values achieved over a long period of time. There is evidence of the efforts of previous periods in history and their affective ideas: accreted, effaced or enduring; there is evidence of character specific to each city, again, accumulated over time; there is evidence of the borrowing or adaptation of ideas from other places and other times, the imagery of other places, and fantasy. There is evidence of organisation, of hierarchies offunctional and social status; and representation, from the depiction of function (dwelling, depot) to the depiction of institutional elites in the monumental fabric of the city. There are the spaces of the city: the yards, streets, open spaces, squares, parks- the places within the city's confines that constitute its interior. From these spaces it is difficult to recognise the origin of the city, the moment of its inception. Most frequently, it exists in myth.

In his accounts of the origins of Rome and Roman settlements, Joseph Rykwert describes both the rites that accompanied their foundation and some explanation of the original or mythical events from which they sprang.1 The foundation rites of these settlements, very often at frontiers in Europe, Africa and Asia Minor, involved the reading of sites in relation to the world and the heavens, performed by an augur; the imagining and drawing of its territory, the templum; the derivation of its orientation, its quartering by the cardo and the decumanus; the surveying of the site

59

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

. I

~~~-{O L-'!~ I/~."!!.- - ' -

-- . 7 ,, '... ~.. ~; - __ ..

The Roman agrimensor at work, reconstruction drawing by P. Frigerio, after Frigerio 'Antichi lnstrumenti Technici' Como, 1933, from Joseph Rykwert, The Idea of a Town: the Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World (Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1976)

2. Leonardo Benevolo, transl. Judith Landry, The Architecture of the Renaissance volumes I, II (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978)

3. Rem Koolhaas, Delirious New York (New York, Oxford University Press, 1978)

and the locating of its important buildings, and the setting of its boundaries and gates. This last act in particular was invested with special significance. For the ploughing of the ground (ploughing itself invested with the sexual symbolism of the union between man and earth) with an ox and a cow-the ox adjacent to the area outside the settlement, the cow adjacent to the area set inside-defined the city protected within its boundary and the world without. The city was therefore founded in contradistinction to this world without, conceived and made as both an actual and symbolic territory claimed from the World.

The New World offered opportunities for European urban civilisation to expand, explore, exploit and colonise; to found new settlements in a vast, unknown domain, a truly new World. First, Portuguese and Spanish settlements, then Dutch, French, and British began as pragmatic arrangements of people and institutions. A new settlement established in a hinterland-at a frontier-could either re-enact the city as it was known at home, or create a city at its moment of origin.2 The early settlements in the Americas, such as those in Mexico, Rio de Janeiro, Sao Paolo and Lima, borrowed their forms from European models, with little regard to local circumstances or the appropriateness of their application. Early Dutch settlements such as New Amsterdam, later to become New York under the British, repeated practices of Dutch town-making, making canals (in solid rock) where none were necessary.3 The buildings reiterated the forms of those in the mother countries. Yet, with time and the freedom offered by both the completely new conditions of the New World and the apparent limitlessness of its frontier, the forms of these settlements were often conceived in the image of the ideal as set out by the Roman precedent (whose own praxis came from ideals more deeply ingrained), with their cardinal aspects, their quartered and gridded territories, their keenly felt limits set against the unknown (and possibly

60

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

4. Leonardo Benevolo, t ra nsl. Jud it h Landry, The Architecture of the Renaissance volumes I, II (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978)

5. Joseph Rykwert, The Idea of a Town: the Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World (Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1976)

Afbeelding van de Stadt Amsterdam in Nieuw Nederland. 'The Castello Plan' 1660, Museum of the City of New York, Gift of La Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana, 49.150

Picturing territories

hostile) without; from established military practice (not estranged from the Roman precedents); and from other ideal models, such as suggested by readings and interpretations of Thomas More's Utopia.4

Whether idealised or remembered, the form of America's first settlements realised an ancient and long-absent aspect of urban reality: that the outside that lay beyond the confines of the city was not necessarily the domain of competing or enemy cities, but the unknown. In other words, the real conditions of the American settlement were very close to those experienced in much earlier settlements, in time much closer to the origins of human civilisation. In addition, there was the compulsion to expand, to extend into the domain of the unknown. This remains the germ of American urban civilisation.

Devices The purpose of this essay is to describe devices used to territorialise and urbanise the frontier of the United States that have come to dominate the forms of its urban civilisation: their genesis, development and their effects on public spaces. One dominant pattern (of ancient origin), the grid,5 plays a central role in the very modern conception of American territory. The conquest of this territory as it was realised in the United States during the nineteenth century and its means have influenced the making of its cities and their spaces: they bear the marks of the territorialisation

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

6. Thomas Jefferson, 'Notes on the State of Virginia' in Albert Ellery Bergh [ed.], The Writings of Thomas Jefferson vol. 2 (1853) on www.etext.lib.virginia.edu

7. Leonardo Benevolo, transl. Judith Landry, The Architecture of the Renaissance volumes I, II (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978)

8. Dee Brown, The American West (London, Pocket Books/Simon & Schuster, 2004) 9. Rosalind E. Krauss, 'Photography's Discursive Spaces' in The Originality of the Avant-Garde, and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge MA, MIT Press, 1985)

10. Leonardo Benevolo, transl. Judith Landry, The Architecture of the Renaissance volumes I, II (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978)

11. Dee Brown, The American West (London, Pocket Books/Simon & Schuster, 2004)

12. Malcolm Bell III & Junior League of Savannah, Historic Savannah (Savannah GA, Historic Savannah Foundation, 1968) 3

13. Leonardo Benevolo, transl. Judith Landry, The Architecture of the Renaissance volumes I, II (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978)

and urbanisation of its vast frontier, an achievement effected over remarkably short period of time. It was an achievement enabled b ~h zeal for independence held by individual settlers; a sympathetic u~ge e felt by its political elite, forged in the heat of revolution, resulting in idealism about the State, its institutions and the means available to it 6 actualised conceptual models of territorial appropriation that reflect~d the last phase of Renaissance thinking; 1 the development of industrial civilisation and its demand for resources and the terrain wherein they were held; commercial interests and their need to speculate and generate capital; military interests and their demands for perpetual revolution and conquest; actual needs to connect disparate populations together that required infrastructure on a scale never previously achieved; the dispersal and near-annihilation of indigenous people living in this territory;8 and representations that galvanised a collective desire to occupy these territories by picturing its empty and emptied spaces, to make them imaginary. 9

Despite the various histories of European colonies in the Americas, and despite the various settlement plans that were proposed (and built, in great number, in a most rational manner between the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries, particularly by the Spanish in Peru, Colombia, Mexico and California),10 it is the United States where town planning, hitherto pragmatic and modestly symbolic, was conceptualised and projected on a territorial scale. The establishment of settlement changed from methods colonial in character, bearing the traces or hopes of far-away fatherlands, into a strategy of possession for a people at a continuously advancing frontier (although it is known that indigenous people lived 'on the other side', it was always assumed that they could be pushed back into an endless beyond).11 One notes the difference between these two modes of planning and action in the plan and view of a colonial settlement, Savannah, Georgia (1733), when contrasted with the abstract planning and territorial grid of a revolutionary nature, as proposed by Thomas Jefferson in his Land Ordinance of1784 (modified to become law in 1785, further modified for widespread implementation as the Northwest Ordinance in 1787).

The clearing: Savannah The plan for Savannah by James Oglethorpe, as authorised by George II as part of the urbanisation of the new colony of Georgia, provided specific areas ofland for town dwellers, suburb-dwellers and farmers, each with their characteristic plot size, organised in a grid of super-blocks with specific limits: 'In the assignment of land to the individual colonists, Oglethorpe granted each freeholder 50 acres (20.23 hectares) of land, which in addition to the 60 x 90 foot (roughly 20 x 30 metres) town-lots or "lotts for houses", included "garden lotts" of 5 acres (just over 2 hectares) each, and beyond such garden lotts hath set out farms of 44 acres ... ' (17.8 hectares).12 Each time the city grew, it would expand in units of super-blocks.13 In an image of the settlement made by townsman Peter Gordon (1734), the lots can be seen to be drawn out in a kind of clearing: the town is set against the wilderness. Among the houses are the monumental or public buildings: ' ... the guard house, the tabernacle,

62

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

Peter Gordon, View of Savannah as it stood the 29th March 1734, Library of Congress, Washington DC, Historic Urban Plans, from Malcolm Bell Ill & Junior League of Savannah, Historic Savannah

14. Malcolm Bell III & Junior League of Savannah, Historic Savannah (Savanna h GA, Historic Savannah Foundation, 1968) 5

15. Bell, ibid. 2

16. Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (London, Harper Perennial, 1995) 49

17. Schama, ibid. 192, 193

P1ctunng terntones

courthouse, public store, public mill, draw well, fort, and the parsonage house ... ' 14 Beyond the defined area of the township there is pictured a wooded wilderness. Some grazing of creatures happens there, but it was acknowledged to be potentially dangerous, and so a parcel of land was reserved within the system to accommodate those who would have to find space quickly in case of war. The whole plan was devised in consideration of easy defence. Indeed, 'Where the town lands end, the villages begin; four villages make a ward without, which depends on one of the wards within the town. The use of this is, in case war should happen, the villagers without may have places in the town, to bring their families and their cattle into for refuge, and to that purpose, there is a square left in every ward, big enough for the outwards to come in.' (Francis Moore (1736)).15

This land without held both a rational terror and an irrational anxiety more deeply felt, with its place in sylvan myth.16 The wood was outside the jurisdictive and psychological control of the settlement; it represented the terror of the wilderness, shelter to wild men and beasts, a shelter that had to be progressively cleared.17 Despite the super-block of Savannah's plan-a specifically American and modem innovation in planning consistent with practice throughout the Americas from the

63

..

MariaHighlight

-

The territorial grid established by Thomas Jefferson with the Land Ordinance of 1785, from Leonardo Benevolo, Architecture of the Renaissance, volume II (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978)

18. Frederick Jackson Turner, The Significance of the Frontier in American History(New York, 1920) on http://xroads.virginia.edu/

19. Thomas Jeffe rson, Constitution of the United States of America, (Library of Congress, 1776)

20. Joseph Rykwert, The Idea of a Town: the Anthropology of Urban Form in Rome, Italy and the Ancient World (Princeton NJ, Princeton University Press, 1976)

A SECTION OF LAND - 640 ACRES.

A "" is r6 ~ /ul. A c/u1in is 66 fut or I 1ods. A mile isp10 rods, 80 eltainsor 5,280/1 A Sf/Na rt rod is 272 :( Sf/uare /ed. An aete

-

21. Thomas Jefferson, Constitution of the United States of America, (Library ofCongress, 1776)

22. Thomas Jefferson, letter to Thaddeus Koschiusko (1810) ME12:369, University of Virginia

23. Jefferson, Thomas, 'Notes on the State of Virginia' in Albert Ellery Bergh [ed.], The Writings of Thomas Jefferson vol. 2 (1853) on www.etext.lib.virginia.edu, op. cit.

24. Dana Cuff 'Community Property: Enter the Architect or, the Politics of Form' in Michael Bell, Sze Tsung Leong [eds.]. Slow Space (New York, Monacelli Press, 1998)

25. Jefferson, Thomas, 'Notes on the State ofVirginia' in Albert Ellery Bergh [ed.], The Writings of Thomas Jefferson vol. 2 (1853) on www.etext.lib.virginia.edu, op. cit.

26. Hennepin County, Minnesota, 'History of the Public Land Survey & Hennepin County' on www.co.hennepin.mn.us/vgn/portal / internet/ hcdetailmaster/0,2300,12 73.83307 .115204042,00.html

27. Joseph M. Jonas, 'The Land Ordinance of May 20, 1785: Ohioville Borough's Main Connection to the American Revolution', Milestones, v.9, no.4 (1984) on www.bchistory. org/beavercounty /BeaverCountyCo mmunities/Ohioville/Ohioville/Ohio villLand0rdMF84.html

28. 'Ordinance of1787; Great Northwest Ordinance' on www.u-s-history.com/pages/h365.html

29. 'The Articles of Confederation Government: Ordinance of1784; Public Land Policy' on www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1158.html

30. 'Introduction to Ohio Land History' on www.users.rcn.com/deeds/ohio

t-'1ctunng terntones

'life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness'.21 'The freedom and happiness of man ... [are] the sole objects of all legitimate govemment.'22

In his experience of the (vast) State of Virginia, there were very few indigenous buildings of any consequence, and even fewer works of architecture. Overall, the building stock of wood and plaster, unhappy in appearance, was indicative of the waste that was common among a people with plenty of space but no hope or purpose.23 Self-determination was necessary; Jefferson had an idea of how this self-determination might be effected, not only in the terms of a constitution of a new State, but how that State set about guaranteeing equitable means for the realisation of happiness of the common man. This happiness would be connected to the right to pursue business; the right to own, live on the land and be sustained by the fruits of his labour (inspired by the ideas of Thomas Locke);24 the right to self-government; the birth-right of equality.25 Specific devices, instituted in the forms of Laws and Ordinances, would serve as the ground from which self-realisation could flourish.

The Land Ordinance of 1785 Soon after the conclusion of peace with Britain (1783), Jefferson devised a plan for the survey, partition and distribution of land which would become adopted as law, and serve as the model for all land distribution in the United States until the present day.26 This became necessary as it was clear that the land west of the Applachian Mountains stretching to the Mississippi River would be finally occupied by people from the coastal States in search ofland. Each of these States (Jefferson's Virginia among them) had overlapping claims to deep inland hinterlands, largely unpopulated by Americans. First, indigenous claims were surrendered through treaties and purchases, which were the subject of grave misgivings by the indigenous societies.27 It was decided furthermore that the coastal States should concede the Western, inland portion of their lands and all their contested claims for the creation of an inner layer ofTerritories-N orthwest and Southwest-to be populated and cultivated, each of which would be able to apply for Statehood when their populations reached a level of 60,000.28 The Land Ordinance devised by Jefferson in 1784 had the object of ensuring that these hinterlands remained part of the Union, and that when populated could contribute to the repayment of debt incurred by its War oflndependence with Britain. The guarantee of the areas' population was the rapidly growing immigration to the country from various parts of Europe. Jefferson established procedures for these areas to achieve Statehood, and furthermore attempted to institute the prohibition of slavery in them.29 This last component of his plan was rejected by Congress, leaving an anomaly which would be a central contributing factor much later in the Civil War between North and South.

The plan also had an instrumental component, namely a system for the division ofland. The Ordinance, which became law in 1785, proposed a grid of varying dimensions, suited to the making of both city plots and farms: 'The land was to be surveyed into 6 square mile townships, and those townships were to be divided into 1 mile square "lots". Half the land was to be held as townships and half as lots.' 30 After an initial survey within the Territory of Ohio, modifications to the Ordinance were

65

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

.. "

.. .. .. " "

..

.. .. .. .. ..

pt " " '

av " ' '

... " "

1 '

Township plat of Thirty-six sections (Mark Pim Iott)

31. 'Introduction to Ohio Land History'

32. 'Public Land Policy: Ordinance of1785' on www.u-s-history.com/ pages/h1150.html

33. www.u-s-history.com

34. Leonardo Benevolo, transl. Judith Landry, The Architecture of the Renaissance volumes 1, II (London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1978)

made, due to pressures brought to bear by the coastal or landless States and those southern States campaigning for the continuation of slavery. A new law, the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, met the various objections regarding the relation between the established States and the new Territories, which had been felt to have been given unfair advantage in the previous proposal. These States had already felt aggrieved to have conceded their claims for the potentially resource-rich hinterlands. The new Ordinance featured a revised specification for the division of land, further refined and finalised in 1796: 'It defined the surveying system to be used by all future public land surveys. In this system the townships are six miles or 9,6 kilometres square (Jefferson had originally proposed 10 mile square townships), composed of 36 one-mile (1,6 kilometres) square sections, each of which may be sub-divided into quarters or smaller. The numbering of the sections is serpentine, starting in the northeast comer of the township. Townships are identified as being north or south of a baseline and in a range east or west of a longitudinal meridian line ... ' 31 It was further specified that section numbered 16 of each township should be reserved for an institution of public education. All other sections would be auctioned to th e public. The minimum bidding price was to be one dollar per acre (0,4 hectares), or$ 640 per section. It was hoped that high demand for these lands would raise substantial funds.32 However, even the $640 was above the means of most, and the first sales yielded little in the way of funds for the Treasury. Furthermore, the 640-acre (259 hectares) sections offered in the first sales were too large for most farmers. Later, although the system would be retained, the minimum acreage offered would be reduced.33

The Land Ordinance determined the distribution and den sity of townships and their method of survey, which was to remain unaltered throughout the entire continental territory. Its methods were unaffected by topography: its ambition was to be egalitarian and democratic. The Ordinance could define individual parcels ofland in a township; it could define the boundaries between new States. Its universal applicability, tied to the meridians and parallels, distinguished it from every method that had preceded it, that took into account local circumstances and had tended to divide land along topographical boundaries and geological formations. This very quality made the identification, survey and acquisition of territory-the process ofterritorialisation- abstract and detached. This was representative of the universal, revolutionary means that Jefferson wished to place at the disposal of the American individual.

'Thus the Cartesian network, which guaranteed the measurability of visible forms in the traditional artistic and scientific system, was generalized so as to become applicable on any scale, well beyond the limits that could be embraced by the human eye. The measure of building plot or structure could be derived, with suitable subdivisions, from the geometrical co-ordinates which ringed the earthly globe; but with this generalization the boundaries of traditional culture were overstepped, for they had been linked precisely to the anthropomorphic scale of human sight and movements, and a completely new cultural universe was opened up.'34

66

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

35. Rosalind E. Krauss, 'Grids' in The Originality of the Avant-Garde, and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge MA, MIT Press, 1985) 18

36. Rosalind E. Krauss, 'The Originality of the Avant-garde' in The Originality of the Avant-Garde, and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge MA, MIT Press, 1985) 158

Patrick Gass, Captain Clark and his men shooting bears, from A Journal of the Voyages and Travels of a Corps of Discovery, Philadelphia (1810, Matthew Carey) Library of Congress 728

Picturing territories

Application of the Ordinance: the survey ' ... Logically speaking, the grid extends, in all directions, to infinity.' 35

' ... The absolute stasis of the grid, its lack of hierarchy, of center, of inflection, emphasizes not only its anti-referential character, but- more importantly, its hostility to narrative ... ' 36

Immediately the Northwest Ordinance of1787was made law, means were undertaken to implement the survey and division of land, proceeding from east to west. The possibilities of realising the survey at a truly continental scale came with Thomas Jefferson's Presidency and the purchase of the Louisiana Territory from France in 1803. It also marked a point when the wilderness, which had been until that time actual and local, was completely transformed. The surveys of new territories in the midst of the continent changed the perception of the wildnerness and of American space, particularly as it revealed a territory that was not endlessly wooded, as the east had been-and subjected to endless and brutal clearing- but vast, spacious and relatively barren. Jefferson commissioned an expedition to explore the Interior from Captain Meriwether Lewis and Captain William Clark. Lewis was Jefferson's private secretary, living with him in Washington and party to his decisions on policy. The expedition was one of discovery: the people involved in the expedition became known as the Corps of Discovery, making conceptual claims on a territory which had until then been, in Jefferson's mind at least, a fantastic place of volcanoes and strange beasts. The Lewis and Clark expedition of 1803-1806 was to document the landscape, its topographic and geological features, its flora and fauna, and its climate throughout different times of the year: in essence, the expedition was commissioned

MariaHighlight

-

37. Gerard Baker, 'What happened to the Indians in the years after Lewis and Clark?' on www.pbs.org/ Jewisandclark/living/idx..9.html

38. Stephen Ambrose, 'Why Did Jefferson Want to Explore the West?' on www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/ living/idx..1.html

39. Dee Brown, The American West (London, Pocket Books/Simon & Schu ster, 2004) 412

40. Brown, ibid. 34

41. National Park Service 'Government Surveys: the U.S. Army Corps of Tupographical Engineers' on www.nps. gov / jeff/lewisclark2/ circa1804/West wardExpansion/EarlyExplorers/Gov ernmentSurveys.htm; 'Railroad surveys' on www.nps.gov/jeff/ lewisclark2/circa1804/WestwardEx pansion/EarlyExplorers/Railroad.htm

to discover what its prospects were for human habitation and sustenance. Famously assisted by a young female Indian guide, the expedition survived through its negotiated relationships with, and strategic- in retrospect misplaced- assistance of the native population.37 Jefferson wanted la~d to occupy, populate and exploit: foremost to establish a peaceful and American territory, one that could sustain a people distributed over an area the size of a continent, as idealised in his plans for the Land Ordinance. Jefferson had an insatiable personal appetite for land and its products, and had substantial holdings himself.38 The Western territory was to be the homeland for Jefferson's democratic ideal. The expedition of Lewis and Clark tested the plausibility of his hypothesis; it was also the first manifestation of the American adventure, and set the Romantic tone for the imagining, picturing and occupation of the American West from then onwards.

The surveying of the Western territories proceeded at great speed to the Mississippi River. In the meantime, violent conflict continued with indigenous people at the periphery of populated areas in the east. From these conflicts, lands were ceded and numerous treaties were signed with the various Indian tribes and societies, imposing conditions upon them that were fashioned as guarantees: the consequence was their continual westward migration. Further purchases ofland were made from the Spanish in Florida; the lands were immediately occupied by people from the east. A series of military conflicts between the Indian nations and the U.S. Army continued from north to south of the territory. Defeated nations were forced behind a line west of the Mississippi River. Their lands were occupied by waves of settlers pushing westward, who continually demanded new territories. Various expeditions were undertaken to find routes between the populated areas of the East and the West Coast, where trade with Asia was possible.

The Oregon Trail, established by 1842 between Independence, Missouri and Fort Vancouver, Washington Territory (a distance of some two thousand miles, or 3,200 kilometres), became an extremely well-used route between the two.39 The secret expeditions ofJohn C Fremont, undertaken between 1842 and 1845, were intended to make this route more secure. Fremont was involved in further, clandestine searches for yet more passages through the Rockies and Coastal Mountains.40 ' ... the U.S. began the calculated use of expeditions of discovery as diplomatic weapons. According to Thomas Hart Benton, the Missouri senator, these expeditions were "conceived without {the government's] knowledge, and executed upon solicited orders, of which the design was unknown". These covert missions committed the government to positions on territorial expansion and "manifest destiny" far beyond any publicly announced policies. Their purpose was to dramatise the West for the American public.' 41 The missions were marked by widely publicised tragic incidents, which, in addition to the Gold Rush of 1849 in California, magnified the West's infamy and capital. With its population and wealth burgeoning overnight, California became a State in 1850. Its growth was accompanied by developments in the applications and distributions of photography, through which the West, and California in particular, acquired its imagery.

68

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

42. John L. O'Sullivan, excerpt from 'The Great Nation o f Futurity' in The United States Democratic Review, vol. 6, no. 23 (1839) 426- 430 on www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/in trel/ osulliva.htm

43. William Gilpin, Mission of the North American People. Geographical, Social and Political (Philadelphia, 1874) 30, quoting a letter of1846 from Henry Nash Smith, 'Virgin Land: the Ame rican West as Symbol and Myth' (1950,1978) on http:/ /xroads.virginia.edu/ -HYPER/HNS/home.htm

Picturing territories

The West Coast developed dramatically, but in effective isolation. The space between West and East was a territory occupied by indigenous and displaced populations that had been pushed westwards as a consequence of the conflicts, purchases and treaties of their lands in the east.

The Garden: Yosemite and Manifest Destiny 'The American people having derived their origin from many other nations, and the Declaration of National Independence being entirely based on the great principle of human equality, these facts demonstrate at once our disconnected position as regards any other nation; that we have, in reality, but little connection with the past history of any of them, and still less with all antiquity, its glories, or its crimes. On the contrary, our national birth was the beginning of a new history, the formation and progress of an untried political system, which separates us from the past and connects us with the future only; and so far as regards the entire development of the natural rights of man, in moral, political, and national life, we may confidently assume that our country is destined to be the great nation of futurity. [ ... ]'

'The far-reaching, the boundless future will be the era of American greatness. In its magnificent domain of space and time, the nation of many nations is destined to manifest to mankind the excellence of divine principles; to establish on earth the noblest temple ever dedicated to the worship of the Most High- the Sacred and the 'I'rue. Its floor shall be a hemisphere- its roof the firmament of the star-studded heavens, and its congregation an Union of many Republics, comprising hundreds of happy millions, calling, owning no master, but governed by God's natural and moral law of equality, the law of brotherhood-of "peace and good will amongst men ... "' 42

'The untransacted destiny of the American people is to subdue the continent-to rush over this vast field to the Pacific Ocean-to animate the many hundred millions of its people and to cheer them upward ... -to agitate those herculaean masses-to establish a new order in human affairs .. . -to regenerate superannuated nations ... - to stir the sleep of a hundred centuries-to teach old nations a new civilization-to confirm the destiny of the human race- to carry the career of mankind to its culminating point- to cause a stagnant people to be reborn-to perfect science-to emblazon history with the conquest of peace-to shed a new and resplendent glory on mankind-to unite the world in one social family- to dissolve the spell of tyranny and exalt charity-to absolve the curse that weighs down humanity, and to shed blessings round the world!'43

The West acted as a magnet for eastern attentions and westward expansion. Not only were there prospects of personal fortunes to be made; it was also believed that the West was the natural home-a Promised Land-for the American People. Encouraged by a combination ofreligious fervour and the flush of Romanticism, a cult of the West was generated and given form by the idea of Manifest Destiny, that posited that the West was the property of Americans by divine right, and that there was furthermore a moral obligation to appropriate and cultivate its territory. John O'Sullivan was editor of the United States Democratic

69

MariaHighlight

-

Carleton E. Watkins. First view of the Yosemite Valley from the Mariposa Trail, California, 1865-1866, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. 84.X0.199.3

70

-

44. Dee Brown, The American West (London, Pocket Books/Simon & Schuster, 2004) 411-415

45. Sandra S. Phillips, 'To Subdue the Continent: Photographs of the Developing West', in Sandra S. Philips [et al.), Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West from 1849 to the Present (San Francisco, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/Chronicle Books, 1996)

46. Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (London, Harper Perennial, 1995) 192, 193

Picturing terntones

Review, who first stated ideals in 1839 that would be called Manifest Destiny in 1845: it was the will of God that the United States should control North America in its entirety.44 This was a holy obligation, which was taken up by many advocates, including preachers, politicians, militarists and businessmen. Frequently, these were rolled into one, such as the politician and apostle of the transcontinental railway, Thomas Hart Benton, and the engineer, militarist, politician (the first Governor of Colorado) and self-styled philosopher Colonel William Gilpin, the author of The Central Gold Region (1860), later published as Mission of the North American People (1874). According to Sandra Phillips, the duty implicit in the proselytisers of Manifest Destiny was consistently evoked in sexual terms, a character resonant with the origin rites of Roman settlements.

'Attitudes toward the West were expressed in the language of control: We were to "conquer" Nature, or as Gilpin put it: "subdue" its geography. Nature was in need of"taming"; she was "wild", "virgin" and often "dark"; she needed to be "penetrated" and "controlled". John L. O'Sullivan, who first used the term Manifest Destiny in 1845, did so in terms of an almost inevitable sexual claim: " ... fit] is by the right of our manifest destiny to overspread and to possess the whole of the continent", he said. Likewise, the eloquent geologist Clarence King wanted to use his scientific learning to "propel and guide the great plowshare on through the virgin sod of the unknown".'

'[ .. .] The doctrine of Manifest Destiny, one of the great motivating forces that promoted rapid development of the West, held that the American land was providentially favoured and its potential wealth destined for fruitful use. (Thomas) Cole's sublime wilderness was thus enthusiastically transformed into a garden, and Jefferson's dream of a yeoman nation was fulfilled.'45

This idea could be said to act as justification for whatever occupation, conquest or exploitation ofland that was desired to be undertaken. Hitherto, the American wilderness had been habitually treated with contempt: the English-born Romantic painter Thomas Cole had mourned the treatment of the land and the spoliation of its natural beauty; James Madison had bemoaned the 'injurious and excessive destruction' of the landscape;46 the awesome expanse of the continental heartland was r egarded as an obstacle to be traversed as quickly as possible. Manifest Destiny gave the traversing and occupation of the American West a purpose, authorising the entire American democratic project as one of civilisation and investing its manifestation on theland with divine justification. The texts of Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman, in their venerations of the divine in Nature and the American man, followed Manifest Destiny's lead.

As though evidence of divine Providence, the West was held to be the Garden (Eden) through the discovery of the Yosemite Valley in California. This valley, pictured by photographers and painters, became Manifest Destiny's symbol. Its sublime beauty was a demonstration of the presence of God in the making of America: proof that Americans were a chosen people, that Manifest Destiny was not a theory but an evident fact.

71

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

47. Rosalind E. Krauss,'Photography's Discursive Spaces' in The Originality of the Avant-Garde, and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge MA, MIT Press, 1985

48. Sandra S. Phillips, 'To Subdue the Continent Photographs of the Developing West', in Sandra S. Philips [et al.), Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West from 1849 to the Present (San Francisco, San Francisco Museum of Modem Art/Chronicle Books, 1996) 18; National Gallery of Art, Washington, 'Carleton B. Watkins: the Art of Perception'onwww.nga. gov/exhibitions/watkinsbro

49. Sandra S. Phillips, 'To Subdue the Continent: Photographs of the Developing West', in Sandra S. Philips [et al.), Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West from 1849 to the Present (San Francisco, San Francisco Museum of Modem Art/Chronicle Books, 1996) 18

50. Weston Naef [ed.], In Focus: Carleton Watkins. Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997)

51. Phillips, Sandra S. Phillips, 'To Subdue the Continent: Photographs of the Developing West', in Sandra S. Philips [et al.), Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West from 1849 to the Present (San Francisco, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/Chronicle Books, 1996)19

52. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 'Carleton E. Watkins: the Art of Perception' on www.nga. gov /exhibitions/watkinsbro; Weston Naef[ed.J,In Focus: Carleton Watkins. Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997)

53. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 'Carleton E. Watkins: the Art of Perception' on www.nga. gov/exhibitions/watkinsbro

54. National Gallery of Art, ibid.

55. Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (London, Harper Perennial, 1995) 191

Though pictured by several photographers including Eadweard Muybridge, the photographic 'views'47 made by Carleton E. Watkins were perhaps the most widely known, advertised and distributed. Watkins had moved to California in 1851 as a young man like many others, attracted by the excitement raised by the Gold Rush.48 Through a series of cultivated connections (most notably to future railroad baron Collis Huntington) and fortuitous circumstances, he came to be a photographer, and was commissioned to photograph the mines of the Mariposa estate-close to Yosemite-by John C Fremont, who operated them. These photographs were intended both to document the mines and to attract the attention of potential investors in them.49 The Yosemite valley-an extraordinary landscape of huge, totemic rocky outcrops and waterfalls set around a meadow with mirror-lakes and a winding river- inspired Watkins to make photographs. Its beauty had to be represented to be believed. He had a camera specially made by a carpenter to accommodate extremely large glass negative plates,-mammoth plates-from which he made contact prints on site (there were no satisfactory enlargement processes available to photographers at the time).50 The first of his eight expeditions was made in 1861.51 He was further commissioned to make photographs of Yosemite in 1864 and 1865 by Josiah Whitney and William Brewer for the California State Geological Survey.52

In 1862, Watkins exhibited the first collection of Yosemite photographs in the windows of the Goupil Gallery in New York, where they were rapturously received: '.As specimens of the photographic art they are unequalled. The views are ... indescribably unique and beautiful. Nothing in the way of landscapes can be more impressive.' -exhibition review, The New York Times, 1862.53 The photographs tapped into the spirit of the country's leading literary lights and ideologues: 'Ralph Waldo Emerson declared that Watkins' images of the massive sequoia, "Grizzly Giant", "made the tree possible", for these photographs provided evidence of its existence. The photographs affected the East's most prominent artists: the landscape painter, Alfred Bierstadt saw Watkins' photographs ... and was inspired to visit the Yosemite Valley.' 54 Furthermore, the photographs were read as symbols of Manifest Destiny: 'Watkins' photographs ... were a phenomenal success ... Suddenly, Yosemite became a symbol of a landscape that was beyond the reach of sectional conflict, a primordial place of such transcendent beauty that it proclaimed the gift of the Creator to his new Chosen People.'55

Watkins's photographs made a mental, mythical image of the American space, reinforcing ideological arguments and inspiring new desires. The photographs documented Yosemite; they also acted as proof of the West's transcendence, ensuring the inevitability of its occupation. Fused with ideology, legislative and military agency and technological development, the reactions unleashed by the pictures galvanised the various processes of American territorialisation.

The pictures made a significant impact, partly due to their novel and spectacular subject matter, and partly due to their composition. A representative Watkins photograph of Yosemite (different from his documentary photography for mining and railroad interests that he was commissioned to make, and were sold to the public) placed a significant

72

-

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

Carleton E. Watkins, From the Best General View, Mariposa Trail, Yosemite Valley, California, 1865~86~TheJ. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.X0.199.4

73

-

Carleton E. Watkins, The Grizzly Giant, Mariposa Grove. 1865-1866, The J . Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.X0.199.64

56. Da niel Wolf[ed.], The American Space: Meaning in Nineteenth Century Landscape Photography (Middletown CT, Wesleyan University Press, 1983)

natural phenomenon in the centre of the view: the subject was an entity that confronted the viewer with its substance and immutability. Photographs of the Cathedral Rocks at Yosemite showed geological facts isolated as strange forms in composed spaces: they were pictured not merely as rocks, but as beings that could be identified with. The photographs of the giant sequoias seemed to reinforce this anthropomorphic investment: their huge trunks, figured by the detail of the ages, defiant ly filled their pictures' frames, inviolate. The photograph entitled Grizzly Giant (1866)56 showed an enormous sp ecimen-apparently a survivor of some natural calamity- filling the view with its gnarled ent irety, rendering a crew of men standing around its base as insignificant. Watkins pictured noble impossibilities that were utterly self-sufficient. His pictures of Yosemite, like the pictured landscape itself, were full: th eir scenes did not require human presen ce. Their plenitude invited the viewer to be enraptured by them, to vener at e them. Watkins's views of Yosemite came to constitute a call to the West, a paradise to be seen and experienced.

74

MariaHighlight

-

Carleton E. Watkins, Cape Horn, near Celilo, Columbia River, c. 1867, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XC.979.7348

57. Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (London, Har per Perennial, 1995) 196 58. National Gallery of Art , Washington, 'Carleton E. Watkins: the Art of Perception' on www.nga. gov/exhibitions/watkinsbro

59. Weston Naef [ed.],Jn Focus: Carleton Watkins. Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997)

60. National Gallery of Art, Washington, 'Carleton E. Watkins: the Art of Perception' on www.nga . gov/exhibitions/watkinsbro

61. Sandra S. Phillips, 'To Subdue theContinent: Photographs of t he Developing West', in Sandra S. Phillips [et al.], Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West from 1849 to the Present (San Francisco, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/Chronicle Books, 1997) 19

62. Dee Brown, The American West (London, Pocket Books/Simon & Schuster, 2004); Rosalind E. Krauss, 'Photography's Discursive Spaces' in The Originality of the Avant-Garde, and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge MA, MIT Press, 1985

Picturing terntones

The painter Alfred Bierstadt, inspired by the sight of Watkins' photographs in New York (and very probably a contemporary visit to Berlin to see the paintings of Caspar David Friedrich)57 responded by travelling with surveys and painting Yosemite with quasi-religious reverence, invoking the sublime. Watkins' photographs of Yosemite were presented as equivalents to the marvelous landscapes they pictured. Their 'mammoth' format prints (typically around 18 x 22 inches-450 x 550 mm)58 held all details of their pictured scenes in very fine focus. Watkins favoured presenting these monumental photographs in black walnut frames and large mattes, hung closely together to line the walls of his own Yosemite Art Gallery, which he opened in 1867.59 Watkins sent thirty of his Yosemite pictures to the Universal Exhibition in Paris, where they were awarded a m edal,60 and garnered an international viewing public. The views and their maker were made famous, and there was consequently much demand for prints and reproductions. Watkins, on his first expedition in 1861, had ensured that he made various stereo views of the Valley, altering the angles of view slightly for different effects, in addition to his mammoth plates.61 At the time, the stereograph was by far the most popular type of photograph with American consumers, for whom they constituted a form of home entertainment: Watkins consciously made work for a variety of audiences.62 Across society, then, Watkins's photographs profoundly affected contemporary interpretations of the Western space: '(Watkins' images) have become icons of the last vision of an uncorrupted world. Watkins was a keen observer of the transitions between wilderness and encroaching humanity, and many of his

75

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

Carleton E. Watkins, Cape Horn, Columbia River, 1867, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 96.XC.25.3

63. Richard Pare, Photography and Architecture 1839-1949, Montreal (1982) 22

photographs reflect this ... It is not so much a wistful record of the vanishing wilderness as an affirmation of the land of promise and the assumption of the American birthright. It is a vision of"past hopes and future longings" (John Coplans).' 63

Watkins' views of Yosemite both proselytised and sold Yosemite as a divine artefact and as American destiny manifest to the eastern, urban, American public; his views of railways and working settlements in nature legitimated the idea of occupation and inhabitation of a spectacular and apparently empty American landscape.

...............

The framing of Yosemite was representative of the conflicts that lay at the heart of American hopes for its territorialisation of the West: it was at once there for expansion and exploitation (since its spaces and resources were so impossibly abundant, there seemed no limit to the advantages to be had from them); and it was a space to be venerated, considered as symbolic of American idealism. It furthermore represented the idea of the democratic American Na ti on itself, in being the territory upon which its idealism, in the form of the Land Ordinance- that guarantee of individual autonomy and collective self-government-could be enacted.

The Homestead Act of 1862 There were additional incentives for occupying the West. The financial needs of the United States Treasury meant that the spaces claimed, surveyed and owned by the U.S. government as Territories-so-called Public Lands-were required to produce revenue. The great, State-

76

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

Carleton E. Watkins, 'Agassiz' Column, Yosemite. 1878, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 92.XM.99.8

77

r-1ccunng temtone

-

64. Richard Pence, The Homestead Act of 1862, www.users.rcn.com/deeds

65. Pence, ibid.

66. James Corner and Alistair S. MacLean, Taking Measures Across the American Landscape (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1996)

Manassah Cutler, Map of Ohio showing land divisions as mandated by Thomas Jefferson's Land Ordinance of 1785, c. 1788, From Michael Bell, Sze Tsung Leong [eds.], Slow Space (New York, Monacelli Press, 1998)

sponsored impulse forthe inhabitation of the vast spaces of the centre of the American West was provided by the Homestead Act of1862. The Act came into existence after an extremely long and contentious period of debate about how Public Lands should be distributed.64 This Act was devised so that the landscape, as foreseen by Jefferson in the Land Ordinance and achieved by the surveyors of the U.S. government, could be completely occupied and cultivated. This was effected by the legislation of a pattern of homesteads, each with a house and farm, and areas of land set aside for forestry, agriculture and animal husbandry within an area of pre-determined size. 'The Act ... allowed anyone to file for a quarter-section of free land (160 acres, or 64,75 hectares). The land was yours at the end of jive years if you had built a house on it, dug a well, broken (plowed) ten acres (just over 4 hectares), and actually lived there.' 65 This pattern is still visibly evident in the American landscape today, forming an image of the typical agrarian American West.66 There were incentives to encourage this occupation, in the form of the deferral of rent payments (the U.S. government owned the land) for the first five years of occupation. Applicants for land holdings had to live on the land and cultivate it, with a few conditions pertaining to the cultivated elements. If the land was properly cared for, the occupants

78

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

67. Jefferson, Thomas, 'Notes on the State of Virginia' in Albert Ellery Bergh [ed.], The Writings of Thomas Jefferson vol. 2 (1853) on www.etext.lib.virginia.edu, op. cit.

68. Richard Pence, The Homestead Act of 1862, www.users.rcn.com/deeds

The survey landscape of the West from the air ( Iowa), from Google Earth

Picturing territories

then had the opportunity to keep the property. With a whole territory full of productive land, an entire population could become landholders, kept in productive work, contributing to both their individual purses and both regional and national economies. It was a realisation of the ideal set out by Thomas Jefferson some seventy-five years before: the self-governing, land-working 'nation of yeomen'. 67 The realisation of the Act had mixed success: it operated by the assumption that all land was equally productive, when this was not the case. Many of the stipulations set by the government were impossible to achieve because of the local circumstances of the lands and their available natural resources. In most cases, the areas ofland assigned for rent were too large for family farmers to cultivate them with any degree of success. In others, these areas were far too small to be economically viable. Na tu rally, such properties, and successful ones as well, were prey to land speculation. 'The better lands soon came under the control of the railroads and speculators, forcing settlers to buy from them rather than accept the poorer government lands. Even so, by 1900, about 600,000 farmers had received clear title to lands covering about 80 million acres (32.37 million hectares).'68

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

69. Frederick Jackson Turner, 'The Significance of The Frontier in American History' (New York, 1920) on http://xroads.virginia.edu/

70. Turner, ibid.

71. Dee Brown, The American West (London, Pocket Books/Simon & Schuster, 2004)

72. Frederick Jackson Turner, 'The Significance of The Frontier in American History' (New York, 1920) on http://xroads.virginia.edu/ % 7EHYPER/TURNER/

73. Dee Brown, The American West (London, Pocket Books/Simon & Schuster, 2004).; Stephen Ambrose, Ambrose, The World at War: Special Presentation-Who Won World War '.lWo? (London, Thames Television, 1974)

The settlers were inevitably new immigrants and poorer Americans from the East.69 Soon after the end of the Civil War, many former Southern soldiers moved to the West to make a new start.

The new settlements of the West arose in real settings with a political aspect, free from slavery. The issue of slavery was so contentious that it contributed to the split of the Union. In the enactment of the Land Ordinance of1785, several states in the South had ensured its anti-slavery provisions were removed. The Civil War between North and South (1860-1865), however, allowed legislation to be enacted without resort to the South's consent: they had ceded from the Union. The Homestead Act of1862 was therefore free oflimitations that might have been imposed by these States. The movement to the West encouraged by the Homestead Act came mostly from the Middle region of the country, as opposed to North or South, and featured people not of English descent as in these areas but those of many other nationalities who had either recently emigrated from Europe or had been established for some time.70 The homesteaders were drawn from all over Europe, sometimes in entire communities and congregations. The railroad companies were particularly instrumental in the 're-settlement' of such communities on land they had acquired through speculation, offering the land and even 'ready-made' homes to buyers on favourable terms.71

The United States' financial resources had been extremely strained by the Civil War. When the Civil War was concluded, the U.S. Army could turn its attentions to securing the West for American territorial and economic interests. The land was seen as a kind of treasury: it was to be peopled and rendered productive in order to generate wealth. Natural resources were to be drawn from the land both to create wealth and sustain the burgeoning industry of Eastern and central cities. The development of the West was seen as absolutely necessary for the safe conduct of the country's economic and even social order.

Clearing the interior: Indian Wars The West, therefore, had to be secured: a long sequence oflndian Wars throughout the 1860s and 1870s were waged to claim Indian lands as territories of the United States, and clearthem forthe ever-advancing waves of settlers. The frontier was constantly being pushed westward and the Indians restricted to ever-smaller areas.72 Treaties between the Indians and the Americans were agreed, with the stated object of defining new boundaries for the limits of both Indian territory and American expansion; yet the inevitable consequence of these treaties was the displacement of many Nations to new reserves that bore no relations to the natural or traditional occupations of the people enclosed within them. The many agreements were broken as a matter of course by the Americans, and the Indians were forced either to vacate and retreat, or subjected to 'white man's ways' on reserves. Their alternative was also the only foreseeable outcome: annihilation.73 The U.S. Army were the agents of this forced removal, in response to the demands of settlers, speculators and government. The ideology of Manifest Destiny was its impetus, blinding most to the iniquity of its perpetration. Territories occupied by the Indians were seen to be necessary as grazing

80

MariaHighlight

-

Across the Continent; Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way, 1868, Drawn by F.F. Palmer, Published by Currier & Ives The Museum of the City of New York, Harry T. Peters Collection, 56.300.107

77. National Park Service, 'Railroad surveys' on www.nps.gov/jeff/ Iewisclark2/ circa1804/WestwardEx pansion/EarlyExplorers/ Railroad.htm

78. Sandra S. Phillips, 'To Subdue the Continent: Photographs of the Developing West', Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West from 1849 to the Present (San Francisco, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/Chronicle Books, 1997) 22, 23

Crossing the West the transcontinental railroad As part of the programme of possession and conquest, it was necessary that the West was explored and surveyed. A series of major surveys were undertaken during the 1840s and 1850s to study the topography of the Western landscape, with the objective of finding routes for transcontinental railroads. In 1848, Thomas Hart Benton instigated the exploration of a route between St. Louis and San Francisco: the expedition was led by John C Fremont (who was also Benton's son-in-law). In 1853, Congress approved a government-sponsored survey of principal railroad routes between the East and the Pacific.77 Political disputes, particularly over the issue of slavery, consistently delayed any kind of implementation of a transcontinental railroad until 1860, when its implementation had become a matter of economic urgency.

A consortia of businessmen (the so-called 'Big Four' of Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins, Collis Huntington and Charles Crocker, Californian merchants and bankers 78 ) formed the Central Pacific Railroad Company in 1861 and initiated a search for a route through the Sierra Mountains. They approached the U.S. government to secure the rights and means to build it. On the basis of the abundance of resources held in the Western territories, the government decided to financially support the railroad-building initiative; the project of building this route was enormously expensive and could not possibly be achieved by the consortium on its own.

82

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

90. Dana Cuff'COmmunity Property: Enter the Architect or, the Politics of Form' in Michael Bell, Sze Tsung Leong (eds.), Slow Space (New York, Monacelli Press, 1998) 126

91. Sandra S. Phillips, 'To Subdue the continent: Photographs of the Developing West', in Sandra S. Phillips [et al.), Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West from 1849 to the Present (San Francisco, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art/Chronicle Books, 1996) 27

92. Phillips, ibid. 25

93. Phillips, ibid.

94. Daniel Wolf[ed.J, The American Space: Meaning in Nineteenth Century Landscape Photography (Middletown CT, Wesleyan University Press, 1983) 119

interest in the land immediately adjacent to the railways that was owned by the railway companies. These lands had been acquired either through government land grants or the speculative-and frequently fraudulent-purchase of homestead properties. They were then rented or sold at prices much higher than they were acquired.9 Concentrated at regular intervals as a consequence of the mechanisms of the Land Ordinance of 1785-the Jeffersonian grid assisted in the easy survey, division, and speculation ofland-industry soon followed all along the track 'as it was laid, generating an enormous amount of wealth to Eastern investors ... '.91 The tourist industry grew in parallel with the push for land, spurred by the pictured evidence of Edenic idylls, and rapidly advancing industrialisation, urbanisation and its promise of wealth. People wanted to see the wonders of the West, both man-made and natural, for themselves. The famously plush Pullman railway coaches (whose interiors were also photographed by Watkins) were made for the comfort of both the transcontinental business traveller and the tourist, whose journey westward had become quickly notorious for its arduousness.

The work made for the railways by photographers such as Russell, Jackson, Alexander Gardner and others tended towards the dramatic and the romantic, in the tradition of painters such as Thomas Cole, Thomas Moran and Alfred Bierstadt. Their paintings shared, with the ideology of Manifest Destiny, a propagandic quality. Through the agency of commercial photography, the image of the American West was intrinsically linked to its bounty of resources and Capital. The railroad surveys of the 1850s and 1860s drew upon Manifest Destiny's ideology and its Imperial pretentions.92 The American landscape had been portrayed in the writing of John O'Sullivan and William Gilpin as an environment made by God, miraculously preserved for the American people. In a God-fearing view that held onto strictly biblical definitions of time and the origins of the World, factual evidence of very deep time was revelatory, if difficult to absorb. The Manifest Destiny view was the popular view. Many photographers, such as Jackson, pictured the West as magnificent and awesome, with the works of American enterprise-railway bridges and earthworks-glorified in their epic struggles with nature, and either natives or railway workers dwarfed, reduced to decorative figuration. Others, such as Andrew Joseph Russell, edited out those evident aspects of the landscape which did not fit with the idea of its fecundity. In the cropping of images he simply chose to delete those elements of the landscape that were too bleak and empty.93

Timothy O'Sullivan The photographs by Timothy O'Sullivan stand apart from the majority of works made for the surveys. In photographs made for the King and Wheeler surveys, the prominence of the pictured view's specific character is particularly evident. Predeterminations of character and atmosphere are absent. O'Sullivan had made perhaps the most famous pictures of the human waste of the Civil War battlefields with Alexander Gardner, which were compiled in Gardner's Photographic Sketch Book of the War.94 The horror of those scenes resulted from their plain, depicted facts and their avoidance of romantic predilections, despite

88

MariaHighlight

-

Carleton E. Watkins, Rooster Rock, Columbia River, c. 1883, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 92.XM.99.8

89

-

Timothy H. O'Sullivan. 'Sage brush desert, Ruby Valley, Nevada,' c. 1869, from Daniel Wolf [ed.], The American Space: Meaning in Nineteenth Century Landscape Photography (Middletown CT, Wesleyan University Press, 1983)

95. William H. Goetzmann, Desolation Thy Name is the Great Basin: Clarence King's Fortieth Parallel Survey on http://viking.som. yale.edu/will/west/dadess.htm

96. Rosalind E. Krauss, 'Photography's Discursive Spaces' in The Originality of the Avant-Garde, and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge MA, MIT Press, 1985) 134; Goetzmann, ibid.

97. Krauss, ibid. 136

98. Frederick Jackson Turner, 'The Significance of The Frontier in American History' (New York, 1920) on http://xroads.virginia.edu/

the inference of their captions. O'Sullivan's work for t he surveys was similarly appreciated for its uninflected picturing of geological and topographical informat ion.95

O'Sullivan's survey photographs were documentary pictures whose application was intended to be scientific.96 They were not photographs proposed as works of art (as in the case of Watkins), and not published in albums during O'Sullivan's lifetime (as pursued by Watkins, Russell and Jackson), though stereo views of his work with the King and Wheeler surveys were distributed and sold while the surveys proceeded.97 The character of O'Sullivan's pictures most faithfully represent that aspect of confrontation with that w hich is not known germane to the experience of the frontier, deeply imbedded in the making of the American settlement and by extension, the American city.98 He pictured the spaces he confronted in ways t hat are devoid of spectacle. His photographs present information to the viewer. (The composition of views in the case of all these landscape photographers was not just a matter of pointing the camera, but involved the manipulation of the camera's bellows and the relation of the lens to the photographic plate that affected focus, pictorial relations and ultimately the viewer's

90

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Desert Sand Hills near Sink of Carson, Nevada, 1867, The J . Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XM.484.42

99. Robert Adam s, 'Introd uction' in Daniel Wolf[ed.], The American Space: Meaning in Nineteenth Century Landscape Photography (Middletown CT, Wesleyan University Press, 1983) 7, 8

100. Weston Naef [ed.]. In Focus: Carleton Watkins. Photographs from the J. Paul Getty Museum, (Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 1997) 110

Picturing terr itories

apprehension of the pictures' 'spaces'.99 ) In O'Sullivan's views, evidence of American occupation of the space, used as props in Jackson's stereos or panoramas, is not used to dramatise the potential of settlement; rather, things are included in the photographs in order to establish measure and scale. The views appear to be fundamentally different from those of Watkins. If anything, O'Sullivan's pictures seem both to reflect and to affect discomfort and alienness: Amy Rule: 'What David (Robertson) was saying reminds me of something that the historian Martha Sandweiss has said about Watkins. To paraphrase her, she said that Watkins was an adventurer in his own land, whereas Timothy O'Sullivan photographed in the West, he was a traveler in an exotic land. She feels that with O'Sullivan there is a sense of awe and danger and suspense and drama, which of course is why we love his work, but with Watkins, and perhaps particularly in this picture, he is in his own element'.100

The views of O'Sullivan can be seen as direct registers of the experience of the frontier, as it was described by the historian Frederick Jackson Turner in 1920: 'The wilderness masters the colonist. It finds him a European in dress, industries, tools, modes of travel, and

91

-

Timothy H. O'Sullivan, Ancient Ruins in the Canon de Che/le, New Mexico, 1873, The J . Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, 84.XM.484.4

92

-

101. Frederick Jackson Turne r, 'The Significance of The Frontier in American History' (New York, 1920 ) on http://xroads.virginia.edu/

102. Hubert L. Dreyfus, 'Heidegger on Gaining a Free Relation to Technology' in Feenberg, Andrew and Alastair Hannay [eds.], Technology and the Politics of Knowledge (Bloomington, Indian a University Press, 1995) 275

Picturing terntorie

thought .... In short, at the frontier the environment is at first too strong for the man. He must accept the conditions which it furnishes, or perish ... Little by little he transforms the wilderness, but the outcome is not the Old Europe ... The fact is, that there is a new product that is American'.101

The experience of the frontier throws the colonist- or in this case, the photographer-back upon himself. In the case of O'Sullivan, something different may have occurred; he may have been subject to another kind of transformation. At the frontier, there is a confrontation between one who is and knows and the known and that which is unknown and potentially unknowable. This produces within the one who is confronting the space of the unknown described by Martin Heidegger as a kind of 'clearing': 'Beyond what is, not away from it, but before it, there is something else that happens. In the midst of beings as a whole an open space occurs. There is a clearing, a lighting ... This open center is ... not surrounded by what is; rather the lighting center itself encircle all that is ... Only this clearing grants and guarantees to human beings a passage to those entities that we ourselves are not; and access to the being that we ourselves are.' (from Martin Heidegger 'The Origin of the Work of Art' in Poetry, Language, Thought, New York, Harper & Row (1971) 116.102 )

Timothy O'Sullivan's pictures affect something quite different to those of Carleton Watkins or the proselytising photographs of William Henry Jackson, Andrew Joseph Russell and others: they acknowledge the strangeness, the otherness of the frontier and its potential danger; the otherness of the photographer, his effects and the world they represent; and the possibility of confrontation with the other. This confrontation is not measured in terms of absorption, appropriation or annihilation: rather, it is staged as an approach. There is movement toward the other, an attempted meeting with otherness.

In this context, it is instructive to see O'Sullivan's photographs of indigenous people and their settlements. He views them not as curiosities or specimens, but as different people in their world. They are not 'ennobled' in the manner ofJackson's portraits of defeated chiefs; the people he photographs stand, without exaggerated formality, in front of their own houses, or sit in front of bushes. Their settlements are documented as they exist; their walled gardens, organised in grids, modestly stretch out into the landscape, the walls rising and falling in sympathy with the undulations of the terrain. Pictures of ordinary realities of other ways of life were unusual in the context of the photography of the West, and O'Sullivan's photographs are documents of consciousness of both the West's and its peoples' specificity and difference; as artefacts made in a spirit contrary, ambivalent or sceptical with regard to the ideology of Manifest Destiny and its territorialising impulses.

Appropriation and transformation of the frontier The experience of the frontier had been with the United States before its War oflndependence. First, there was the colonial frontier, European in its outlook: Savannah's early development was emblematic.

93

-

103. Frederick Jackson Turner, 'The Significance of The Frontier in American History' (New York, 1920) on ht tp://xroads.virginia.edu/

104. Turner, ibid.

105.Jefferson, Thomas, 'Notes on the State of Virginia' in Albert Ellery Bergh [ed.], The Writings of Thomas Jefferson vol. 2 (1853) 241

106. Frederick Jackson Turner, 'The Significance of The Frontier in American History' (New York, 1920) on ht tp://xroads.virginia.edu/

107. Dee Brown, The American West (London, Pocket Books/Simon & Schuster, 2004) 35

108. Frederick Jackson Turner, 'The Significance of The Frontier in American History' (New York, 1920) on h tt p://xroads.virginia.edu/

109. 'Mormons saddle up for Bush's second coming but hope for humility', The Guardian (London, Wednesday, 19 January 2005); James Trainor, 'Don't Fence Me In', frieze, issue 90 (London, April 2005)

110. Dana Cuff, 'Community Property: Enter the Architect or, the Politics of Form' in Michael Bell, Sze Tsung Leong [eds.], Slow Space (New York, Monacelli Press, 1998) 124

111.Jefferson, Thomas, 'Notes on the State of Virginia' in Albert Ellery Bergh [ed.], The Writings of Thomas Jefferson vol. 2 (1853) on www.etext . lib.virginia.edu, op. cit., 207, 241

Growing, specifically American feeling changed both that outlook and the approaches towards exploring, claiming and settlin g the hinterland. A feeling for independence, individuality and a concomitant rejection of government was represented by a demand for land t hat pushed the actual frontier westward over major natural boundaries in increasingly rapid succession. The Allegheny mountains, the Mississippi River, the Missouri River, the Rocky Mountains, then the Great Plains w ere all natural boundaries that were so transcended, each secured by series of Indian Wars.103 According to Frederick Jackson Turner, the meeting of each new frontier was accompanied by an ever-increasing distance from Europe, both cultural and emotional; the corresponding establishment of a specifically American charact er-that of t he pioneer-and t he reinforcement of Jefferson-inspired attribute s of individuality, resourcefulness and militancy. These attributes developed as a result of contact, at every stage of movement westward, with primit ive conditions and new opportunities, fashioning a simple, primitive society.104

This was a society that was in constant movement, with an ever-present wish to find new space to occupy and exploit. The rush of new emigrants from Europe, looking for places to re-establish themselves, for med a heterogeneous culture bound by the individual desires to find space and fulfil what was natural in Americans-according to Thomas Jefferson-'the actual habits of our countrymen (that) attach them to commerce'.105

This group of many peoples came to comprise what is described by Turner as a 'composite nationality',106 democratic and tolerant in nature. Emigrants were often settled in whole communities directly from Europe, encouraged by incentives of the Railroad Companie s and their agents, including very cheap travel to the West and preferent ial house-purchasing deals in pre-built estates.107 Turner note s that the tendency of such groups, particularly when they encountered the frontier's primit ive conditions and relative absence of institutions, was toward familial rather than social organisation: ' .. . the most important effect of the frontier has been in the promotion of democracy here and in Europe. As has been indicated, the frontier is productive of individualism. Complex society is precipitated by the wilderness into a kind of primitive organization based on the family. The tendency is anti-social. It produces antipathy to control, and particularly to any direct control. The tax-gatherer is viewed as a representative of oppression.'108

Tendencies such as fierce independence, distrust of govern ment and resistence of administration and other forms of control were persist ent. They came to characterise the attitudes of pioneers, settlers and permanent (and current) residents of the West.109 Antipathy to control w as accompanied by the demand for self-determination. The Homestead Act, for example, arose from the petitions of the popular Free Soil Movement, which held that land ought to be free if people were going to work upon it. This idea had been prevalent since the time of the Revolution.110 Once th e ownership of the land from the effort of Labour was established individuals insisted , on being left alone. Jefferson had championed the idea of such yeomen, believing that workers of the land were honest and most fit to govern themselves.111 Consequent were the ideas of common suffrage and right s to individuality, privacy and self-realisation. For Turner, the frontier was

94

MariaHighlight

MariaHighlight

-

112. Dee Brown, The American West (London, Poc ke t Books/Simon & Schuster, 2004) 140

113. Frederick Jackson Turner, 'The Significance of The Frontier in American History' (New York, 1920) on http://xroads.virginia.edu/

114. Dana Cuff, 'Community Property: Enter the Architect or, the Politics of Form' in Michael Bell; Sze Tsung Leong [eds.]. Slow Space (New York, Monacelli Press, 1998) 123

115. Cuff, ibid. 126,127

Picturing territories

productive of individualism. This coincides perfectly with Jefferson's observations about his countrymen and his hopes for them, which he worked to enable lifelong through legislation.

Despite the raising of the individual and his rights, the production of the homestead and the possession of land through labour, the American territorialisation of the West produced a different kind of space, which was non-specific and antagonistic to place. This was partly due to the means of the West's cataloguing, measure, partition and occupation- to the many uses of the versatile grid. It was furthermore due to constant agitations for new space for living and the accompanying migrations westward by many diverse groups, each in search of places of their own, lands of opportunity and fresh starts. Movement came from people in the eastern States; from former Civil War soldiers, particularly from the South; and from European emigrants, primarily non-English.112 The image and reality of the Wild West reflected the unsettled nature of such settlement. Local or cultural specificity was impossible to achieve: 'Nothing works for nationalism like intercourse within the nation. Mobility of population is death to localism, and the western frontier worked irresistably in unsettling population. The effect reached back from the frontier and affected profoundly the Atlantic coast and even the Old World.' 113