Philanthrop i ind 201 - pcp.org.pkpcp.org.pk/uploads/Sindh.pdf · iii Philanthrop i ind 201 This...

Transcript of Philanthrop i ind 201 - pcp.org.pkpcp.org.pk/uploads/Sindh.pdf · iii Philanthrop i ind 201 This...

i

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

ii

Individual Indigenous

iii

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

This study is an important milestone in Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy’s (PCP) mission to enhance the volume and effectiveness of indigenous philan-thropy in the country. Undertaking sound research projects to provide au-thentic information on various aspects of philanthropy is an essential element in fulfilling the Centre’s mission. Since its establishment in 2001, PCP has been conducting annual surveys and various researches on philanthropy across Pakistan. The current study is a part of an ambitious endeavour to document the amount, trends and patterns of indigenous philanthropy in the country; information that might lead to effective utilisation, better channelisation and increased awareness.

This study on individual indigenous philanthropy in Sindh is one of the first re-searches carried out in the province to study the volume, trends and practices related to philanthropy by its inhabitants. The Centre visualises this research playing a key role in raising awareness about the nature and potential of giv-ing as a supplement to government resources towards social development.

The findings of this study are a testament to the generosity of the people of Sindh. The amount contributed in the year 2013 amounted to Rs. 67.9 billion; Rs. 42.2 billion in volunteering time Rs. 21 billion in cash and Rs. 4.7 billion in kind. It is heartening to see that despite the increased economic pressures, 97 percent of the households were involved in some sort of philanthropic activity.

In addition to highlighting the household giving trends through quantitative figures, the qualitative analysis has also identified important motivating fac-tors, challenges, patterns of giving and ways to cope up with these challenges which will further enlighten the readers and lead to informed policies.

PCP anticipates that policy makers, philanthropic organisations and individ-uals will find the results of this report to be useful, which will enable them in identifying correct ways to enhance and channelise philanthropy for social development. It is also hoped that the recommendations put forward by PCP on the basis of this study will be of value to all stakeholders, which will enable them to find ways for increasing and channelising philanthropic activities in Sindh. My colleagues on the Board and in the management welcome sugges-tions for improvement in future research endeavours.

Dr. Shamsh Kassim-Lakha, H.I., S.I. Chairman Board of Directors, PCP

Foreword

iv

Individual Indigenous

Foreword iii / List of Tables vi /

List of Figures vii / Acronyms viii /

Acknowledgements ix / Executive Summary xi /

Key Findings of the Study xii /Policy Actions xiii /

Introduction 1 / 1.1 Brief Profile of Sindh Province: 2 /

1.2 Objectives of the Study: 3 /

Literature Review 4 / 2.1. Philanthropy in Selected Countries 5 /

2.1.1 Philanthropy in the United Kingdom 6 / 2.1.2 Philanthropy in Sri Lanka 6 /

2.1.3 Philanthropy in India 6 / 2.1.4 Philanthropy in Pakistan 7 /

Conceptual Framework and Methodology 8 / 3.1 Conceptual Framework 8 /

3.2 Methodology 10 / 3.2.1 Sample Design 10 / 3.2.2 Research Tools 11 /

3.2.3 Data Collection and Processing 12 / 3.3 Method of Analysis 12 /

3.4 Data Limitations 13 /

Findings of the Study 14 / 4.1 Socio-demographic Characteristics of Respondents and Sampled Households 14 /

4.2 Magnitude and Patterns of Individual Giving 17 / 4.2.1 Prevalence 17 /

4.2.2 Magnitude of Individual Giving 18 / 4.2.3 Patterns of Individual Giving 19 /

4.2.4 Qurbani Hides 31 / 4.2.5 Donations to Shrines 32 /

Table of Content

v

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

Motivations for Individual Giving 33 / 5.1 Hypotheses Development 33 /

5.2 Measures of Motivation for Giving 33 / 5.3 General Motivations for Individual Giving 34 /

5.4 Motivations for Cash Donations 35 / 5.5 Motivations for Volunteering Time and In-Kind Gifts 36 /

5.6 Determinants of Individual Philanthropy: Multivariate Analyses 37 /

Individual Philanthropy and Safety Nets: Awareness, Constraints and Complementary Mechanism 40 /

6.1 Understanding the Relationship between Grant Seekers and Grant Givers 40 / 6.1.1 Awareness and Reputation of Organisations 40 /

6.1.2 Role of Trust and Reputation in Organisational Philanthropy: A Multivariate Analysis 42 / 6.2 Constraints and Barriers for Individual Philanthropy 44 /

6.2.1 Pooling of Philanthropic Resources 44 / 6.2.2 Gaps in Government System 45 /

6.2.3 Inefficiency of Zakat and Bait-ul-Mal Systems 46 / 6.3 Philanthropy as Complementary Mechanism for Safety Nets and Poverty Reduction 47 /

Policy Recommendations and The Way Forward 49 / 7.1 Policy Actions 49 /

References: 55 /

vi

Individual Indigenous

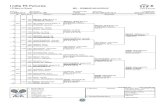

Table 3.1: Sampled PSUs and SSUs in total, urban and rural areas: IIPS Sindh 2013 11

Table 4.1: Percentage distribution of respondents by socio-demographic characteristics: Sindh 2013 14

Table 4.2: Proportion of respondents (%) by type of giving in total, rural and urban areas: Sindh 2013 18

Table 4.3: Estimated value of individual giving: Sindh 2013 19

Table 4.4: Percentage distribution of respondents for in-cash non-zakat donation by type of beneficiaries and socio-demographic characteristics: Sindh 2013 21

Table 4.5: Percentage distribution of respondents giving non-zakat money to individuals by socio demographic characteristics: Sindh 2013 23

Table 4.6: Average amount of Zakat paid and per-centage distribution of respondents by type of organisations and socio-demo-graphic characteristics: Sindh 2013 27

Table 4.7: Time volunteered to individuals and organisations by respondents during last 12 months by area and quintile: Sindh 2013 28

Table 4.8: Percentage distribution of respon-dents who volunteered time by type of beneficiaries and socio-demographic characteristics: Sindh 2013 29

Table 4.9: Proportion (%) of respondents who presented in-kind gifts to organisa-tions, average value (Rs.) of gifts and type of gifts by area and quintile: Sindh 2013 29

Table 5.1: Percentage distribution of respondents by motivation behind giving and so-cio-demographic characteristics: Sindh 2013 34

Table 5.2: Percentage distribution of respondents by motivation behind non-zakat giving to individuals and organisations by area and quintile: Sindh 2013 35

Table 5.3: Percentage distribution of respondents by motivation behind time volunteered to individuals and organisations by area and quintile: Sindh 2013 36

Table 5.4: Percentage distribution of respon-dents by motivation behind presenting in-kind gifts to individuals and organ-isations by area and quintile: Sindh 2013 37

Table 5.5: Determinants of individuals’ non-zakat giving: Sindh 2013 38

Table 5.6: Determinants of individual’s Time Vol-unteered in hours: Sindh 2013 39

Table 6.1: Percentage distribution of respondents who donated non-zakat and Zakat mon-ey by awareness of charitable organi-sations, and knowledge of prominent philanthropists: Sindh 2013 41

Table 6.2: Proportion (%) of the respondents who volunteered time and presented gifts to organisations by awareness of chari-table organisation and knowledge of prominent philanthropists: Sindh 201341

Table 6.3: Percentage distribution of respondents who donated in-kind gifts by type of or-ganisation and awareness of charitable organisations and knowledge of promi-nent philanthropists: Sindh 2013 42

Table 6.4: Determinants of individuals Time Volun-teered in hours: Sindh 2013 60

Table 6.5: Determinants of organisations Time Vol-unteered in hours: Sindh 2013 43

List of Tables

vii

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

Figure 3.1: Conceptual Framework 9

Figure 3.2: Percentage distribution of the sampled households by rural-urban areas: Sindh 2013 11

Figure 4.1: Percentage distribution of respondents by level of educational attainment: Sindh 2013 16

Figure 4.2: Percentage distribution of respondents by occupation: Sindh 2013 16

Figure 4.3: Social living standard index of the sam-pled households: Sindh 2013 16

Figure 4.4: Prevalence (%) of individual giving by rural / urban areas: Sindh 2013 17

Figure 4.5: Percentage of respondents (prevalence) by type and quintiles*: Sindh 2013 18

Figure 4.6: Percentage distribution of individual giving by type: Sindh 2013 19

Figure 4.7: Non-zakat amount donated per month on average by socio-demographic char-acteristics of respondents: Sindh 2013 20

Figure 4.8: Percentage distribution of non-zakat in-dividual beneficiaries: Sindh 2013 22

Figure 4.9: Percentage distribution of respondents giving non-zakat money to organisa-tions: Sindh 2013 24

Figure 4.10: Percentage distribution of respondents for Zakat giving by the type of benefi-ciaries and quintile: Sindh 2013 24

Figure 4.11: Zakat amount donated on average by socio demographic characteristics of respondents: Sindh 2013 25

Figure 4.12: Percentage distribution of respondents by type of beneficiaries of Zakat and socio-demographic characteris tics: Sindh 2013 26

Figure 4.13: Percentage distribution of respondents who volunteered time for organisations by type of organisations and socio-de-mographic characteristics: Sindh 2013 30

Figure 4.14: Percentage distribution of respondents by type of in-kind gifts donated to indi-viduals by area and quintile: Sindh 2013 31

Figure 4.15: Percentage of respondents who per-formed Qurbani by area, education and quintiles: Sindh 2013 32

Figure 4.16: Percentage of the respondents who donated to shrines by area: Sindh 2013 32

Figure 6.1: Percentage distribution of the respon-dents by intentions for future donations and socio-demographic charac teristics: Sindh 2013 48

Figure 6.2: Percentage distribution of respondents by preferred thematic areas for future donations in total, urban and rural areas: Sindh 2013 48

List of Figures

viii

Individual Indigenous

ADB Asian Development Bank

SPSS Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

AKDN Aga Khan Development Network

SRCs Self Representative Cities

APPC Asia Pacific Philanthropic Consortium

SSUs Secondary Sampling Units

APWA All Pakistan Women’s Association

SWD Social Welfare Department

BOS Bureau of Statistics

TCF The Citizens’ Foundation

CAF Charities Aid Foundation

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

CDP Community Development Programme

CSO Civil Society Organisation

FGDs Focus Group Discussions

FPAP Family Planning Association of Pakistan

GDP Gross Domestic Product

IDIs In Depth Interviews

IIPS Individual Indigenous Philanthropy Survey

LRBT Layton Rahmatullah Benevolent Trust

MDGs Millennium Development Goals

NGO Non Governmental Organisation

NPO Non-Profit Organisation

PBS Pakistan Bureau of Statistics

PCP Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy

PPS Probability Proportion to Size

PSUs Primary Sampling Units

SBS Sindh Bureau of Statistics

SES Socio-Economic Status

SKMCH Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital

SPDC Social Policy and Development Centre

Acronyms

ix

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

This research study is the outcome of the collective efforts of a number of people, whose contribution the Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy (PCP) would like to acknowledge. PCP acknowledges the invaluable support extended by the Community Development Programme (CDP), Planning and Development Department, Government of Sindh to sponsor the study. The Centre expresses its deep appreciation for the trust reposed in it by CDP. A special acknowledgement is due to Mr. Aijaz Ahmad Mahesar, Additional Secretary, Planning and Development Department, Government of Sindh and Programme Director, CDP and his team for their continuous support, cooperation and guidance during the course of completion of this research work. PCP would also like to record its thanks to the Bureau of Statistics, Government of Sindh for designing the household sample and Mr. Moazzam Khalil, Chief Executive Officer, Development Strategies for conducting the survey to make study possible.

First of all, PCP owes its gratitude to Dr. Shamsh Kassim-Lakha, former Chairman of the PCP Board for his vital role in the initiation of this work and his constant support and perceptive input during completion of the study and all the Board members for their able guidance and oversight for the entire process of this work. PCP would also like to especially, thank the Research Committee members, Dr. Attiya Inayatullah, Mr. Mueen Afzal, Mr. Ahsan M. Saleem, Dr. Sohail H. Naqvi, Dr. Sania Nishtar, and Mr. Firoz Rasul for their continuous support, professional guidance and input for the of completion of this study.

The Centre would like to acknowledge and appreciate the untiring and committed efforts of Dr. Jennifer Bennett and Ms. Kanwal Qayyum, the two consecutive Senior Programme Managers, in the initial phase of data collection and its preliminary analysis, and Dr. Naushin Mahmood, the successive Senior Programme Manager of PCP, for her technical input and commitment to improve the contents and final composition of the study. In addition, the Centre would like to acknowledge the dedicated efforts of its

Research Unit including previous researchers, Mr. Ali Shoaib, Ms. Rabia Hasan, Mr. Syed Hassan Sagheer and Ms. Sarah J. Nasir and the current research team Mr. Muhammad Ashraf, Mr. Muhammad Ali, Mr. Ali Jadoon and Ms. Naina Qayyum. They have worked hard and put in long hours to bring this study to a successful conclusion. Special thanks are also due to the field survey team for their hard work and dedication to gather data in the field work and the PCP support staff who put in their share of work towards the finalization of this study.

More importantly, we would like to sincerely acknowledge the contribution of Dr. G.M. Arif, Joint Director at the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE) and Dr. Nasir Iqbal, Research Economist at PIDE for their professional input in report writing. Our sincere thanks to both of them for critical analysis of the PCP survey data on individual philanthropy and for the final composition of the report.

We would like to especially, offer our gratitude to Mr. Tanwir Ali Agha, Former Executive Director of PCP for his constant support and guidance in the preparation and completion of this study during his tenure.

Finally, the Centre is especially indebted to Mr. Zaffar A. Khan, former chairperson of the Research Committee and presently, Chairman of the PCP Board of Directors for his constant support and professional guidance during completion of this study. We hope this study will be of use to researchers, development organisations, civil society and policy makers in understanding the issues and challenges related to philanthropy and improving its volume and effectiveness in Sindh province.

Acknowledgements

Shazia Maqsood AmjadExecutive Director,Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy

x

Individual Indigenous

TharparkarBaddin

T.M.K

Thatta

Hyderabad

Karachi

Jamshoro

T.A.Y

MirpurKhas

Umer Kot

SangharMatiari

Nawabshah

NoshehroFerozpur Khairpur

SukkurLarkana

Shikarpur

Jacobabad

Qambar

Shahdadkot Ghotki

Kashmore

Dadu

DISTRICTS OF SINDH

xi

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

Philanthropy or giving to the needy, is deeply embedded in the Pakistani ethos. It encompasses all segments of society that voluntarily give money, goods and time to others for their well being. Philanthropy has the potential to generate significant resources that can be tapped and channelled more effectively for social investment and poverty alleviation to reduce the social sector deficit in the country.

An essential first step is to understand the extent and patterns of philan-thropic activities, to get a better understanding of the underlying dynamics and determinants to be able to design knowledge-based policies, systems and practices in order to promote the effectiveness of philanthropy for Social Sector development in Sindh. To this end, the Community Development Programme (CDP) and Planning and Development Department of the Gov-ernment of Sindh commissioned Pakistan Centre for Philanthropy (PCP) to un-dertake a comprehensive study on Individual Philanthropy in Sindh Province. Sindh is the second largest province of Pakistan with an estimated population of 44.1 million people (reported in 2013). This quantifies 24 percent of Paki-stan’s total population with an urban population of 48 percent, compared to the country’s overall average of 34 percent in 2013. Its capital, Karachi, is the most populous metropolitan city and is the largest financial centre of the country. Rural Sindh, on the other hand, is less developed and is characterised by widespread poverty and poor levels of educational attainment.

This study, based on a household survey and qualitative research, documents the size, scope and patterns of individual indigenous philanthropy in Sindh and investigates the motivations behind giving as well as constraints that impede the optimal utilisation of this resource for social development. The findings provide useful information to all stakeholders including the govern-ment, civil society organisations, and donors that can serve as a basis for a policy dialogue aimed at improving the enabling environment for philanthro-py in social sector development and poverty alleviation in Sindh.

The methodology employed is a mix study design, using both, quantitative and qualitative techniques, to gather information on philanthropy in Sindh. Under the quantitative component, a representative survey of 3000 sampled households was undertaken in both rural and urban areas of Sindh in the year 2013; whereas, the qualitative survey consisted of Focus Group Discus-sions (FGDs) held with the community and in-depth interviews (IDIs) with key stakeholders, including government officials and Civil Society Organisations (CSOs), to seek answers to some questions on the effectiveness and con-straints of philanthropic activities in Sindh. It is important to reiterate that this study reports only on individual and indigenous philanthropy in Sindh. Total philanthropy would equate to much higher figure encompassing the different streams of philanthropy such as corporates, high net-worth individuals and family foundations etc.

Executive Summary

xii

Individual Indigenous

Key Findings of the Study

1 Individual philanthropy is universal in Sindh. Ninety-seven percent of the sampled households are in-volved in some form of giving.

2 Total individual giving in Sindh is estimated at Rs. 67.9 billion in the year 2013. This includes in-cash giv-ing (Zakat and non-zakat) as well as the monetary value of gifts in-kind and time volunteered.

3Of the total giving, Rs 21 billion (31 percent) is given in-cash, Rs. 42.2 billion in time volunteered (62 percent), and only Rs. 4.7 billion (7 percent) in the form of gifts in-kind, indicating that volunteering time is the major form of total giving.

4 Of the total cash giving of Rs. 21 billion, non-zakat money has the major share equating Rs. 17.4 billion (83 percent).

5

Giving to others in Sindh, on average, is less than Rs. 300 per month indicating small and unplanned donations. The variations among various socio-economic groups show that the average donation is higher amongst the respondents living in urban areas (Rs. 307) than in rural areas (Rs. 215). Respon-dents with graduation or higher level of education give about two and a half times more (Rs. 427) than the money given by illiterate donors (Rs. 185). The average donation of the richest group is three times (Rs. 459) the donation made by the poorest (Rs. 148).

6

Religious reasons and altruism are the main motivations behind giving according to more than 90 percent of the respondents. More than two-thirds of the respondents who volunteered time for organ-isations did so because of ‘human compassion’. In-kind gifts are motivated by Islamic belief, altruistic reasons (humanity) and faith-based attitudes.

7

Awareness and knowledge about the transparency, good reputation of organisations and prominent philanthropists motivated people for giving; Edhi Foundation is recognised as one of the most re-nowned organisations working for human welfare and social development. The thematic area or field of work of an organisation, especially in education and health, also influenced the selection of a charitable organisation for cash donations.

8

Seventy-eight percent of the total individual giving is directed towards individuals due to lack of trust in organisations. Amongst individuals, beggars and the disabled are the major beneficiaries of non-zakat donations (76 percent). Amongst organisations,

9 A religious entities such as Mosques and Madrassahs are the top beneficiaries of cash donations (79 percent).

10

Clothing, food and household items are the major types of in-kind goods given to individuals. Food, Qurbani hides and construction materials are donated as gifts in-kind to religious organisations. Volun-teering time is directed mostly towards individuals including a relative, neighbour or the needy, in the form of any kind of help as reported by 99 percent of participants.

11 Donations to shrines are very popular in Sindh, as reported by 78 percent of the respondents.

12

A majority of the respondents reported that in the future, they would still prefer giving to individuals (59 percent). However, about one-third of the respondents (32.5 percent) would consider donating to both individuals and organisations, especially for education and health, if transparency, accountability and positive impact are ensured.

xiii

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

Given the near universality of giving in Sindh, it is clear that philanthropy can play a key role in social sector de-velopment and poverty alleviation in Sindh. For this to materialise, it is essential that the concerns expressed by participants of the survey be addressed and pol-icy actions in some areas be initiated to improve the utilisation of philanthropic contributions in the province. Some key policy recommendations emanating from the study are summarised below. These are elaborated in Chapter 7 of the study.

The magnitude of the social sector deficit in Sindh (as in other Provinces) is such that the Government alone has not been able to bridge the gap. Philanthropy and civil society can provide significant additional resources to support social sector development and poverty allevi-ation, providing relief to the underserved and margin-alised. This has to be within a framework of partnership between Government, Business / philanthropists and civil society, embedded in knowledge and trust, within an enabling environment. This study aims to lay solid basis for a policy dialogue and to build effective part-nerships in the future.

As a practical step, it is suggested that a Taskforce be constituted to evaluate the enabling environment for philanthropy and civil society. This Taskforce should include representatives of stakeholders such as philan-thropists, Government, civil society and public officials to initiate a policy dialogue with stakeholders to im-prove effectiveness of philanthropy in Sindh province.

Policy Actions

1 Reducing the trust deficit among government, CSOs and individual givers through community involve-ment, public private partnerships and need-based activities.

2 Raising awareness about philanthropy and its positive outcomes through Public Service campaigns and better communication and advocacy in the community.

3 Mobilising and channelising philanthropy through Public-Private Partnerships in the social sector to provide an efficient mechanism to improve outreach to the public.

4 Formulating local social development plans at the Union Council level, in consultation with communities to attract local philanthropy.

5Adopting measures to ensure implementation of policies and laws enacted to eliminate beggary and vagrancy through the concerned departments in the province, and providing employment and skill development opportunities to that sub-group.

6

Streamlining existing social welfare and safety net activities of the Government of Sindh and make them more transparent in order to enhance effectiveness and impact. In this regard, improvement in disbursement of the Zakat / Ushr funds through town and local level committees is required to ensure better access to the needy and the poor.

7 Ensuring fully funded priority schemes to get them completed in a timely and productive manner rather than increasing the portfolio of inadequately funded projects / programmes.

8Improving effectiveness of institutional giving through better utilisation of immense donations made to mosques, Madrassahs, and shrines through the involvement of local government departments to main-stream funds in social development projects.

1

Individual Indigenous

Philanthropy – love of humanity – takes place every-where, in all cultures and religions. It includes the act of voluntary giving by individuals or groups to promote common good. Philanthropy is rooted in the ethical notions of giving and serving those beyond one’s family and is often driven by religious traditions and shaped by cultural behaviours and practices (Ilchman, Katz, & Queen, 1998). It deals with important social and moral issues affecting society as well as our individual lives. It also has a significant influence on social, political, religious, moral, and economic spheres of life; the spectrum extends from efforts to limit air pollution to actions that define the rights of children. Philanthropy has been influential in shaping the outcome of issues in religion, education, health, social welfare, commu-nity services, and international relief and development (Payton & Moody, 2008), thereby encompassing a large scope of activities in different spheres of life. Philan-thropy, as voluntary action for the public good, appears in every civilised society and is considered an essential defining characteristic of civilised society (Payton & Moody, 2008).

Pakistan is ranked 53rd according to the World Giving Index - 2013 which looks at charitable behaviour of more than 130 countries across the world (Charities Aid Foundation, 2013). Religious factor provides a strong basis and incentive for people to donate to cater the needs of the poor, sick and marginalised communities. Hence, the guiding force behind social development and community welfare initiatives is the deep-rooted impact of Islam and the national patriotic feeling amongst people providing a strong incentive for volunteerism (Seljuq, 2005). In addition, joint family system, professional guilds and community living have channelised philanthropic activities for centuries (Iqbal et al., 2004), that has well manifested after indepen-dence of the country in 1947. The government and the people showed fortitude and sympathy in rehabilitating millions of Muhajir (immigrants) from India, providing them with money, food, shelter, education and health-care facilities. In 1950s, various welfare organisations came into being, including All Pakistan Women’s Association (APWA), an NGO open for all women across Pakistan irrespective of cast and creed. Various non-profit organisations focusing on health and social welfare activities have been working successfully for several years, including Family Planning Association of Pakistan (FPAP), Edhi Foundation, Hamdard Founda-tion, The Citizen Foundation (TCF) and Mary Adelaide

Leprosy Centre (Seljuq, 2005) amongst others. Keeping in view the above history, a study by Ismail (2003) notes that the total number of active non-profit organisations engaged in philanthropic activities in Pakistan is about 45,000 (both registered and unregistered). The services offered by these organisations span the full range of services envisaged in the internationally defined list of philanthropic organisations (Salamon & Anheiher, 1996), and voluntary donations from individuals support the activities of these organisations. Edhi Foundation is one of the most active philanthropic organisations generating ninety percent of its donations from within Pakistan including contributions in-kind, in the form of food, clothing, medicines and animal hides etc. The value of the pure voluntary services is not quantified in the financial records, but it is a significant part of the organisation’s strength.

There is a vast body of literature available on the determinants and socio-economic consequences of philanthropy in the developed world which has shown that religion, altruism, awareness of need, reputation and efficacy determine the giving behaviour of individ-uals (Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). Donations are used for the development of communities, organisations and individuals by supporting projects that foster capac-ity-building and human dignity (Armand Bombardier Foundation, 2014).

In Pakistan, very few studies have quantified the indige-nous giving and their impact on socio-economic devel-opment. A study conducted by Aga Khan Development Network (2000) has estimated that the value of indi-vidual giving in Pakistan is Rs. 70 billion (2.2 percent of GNP), which includes in-cash donations (Rs. 30 billion), gifts-in-kind (Rs. 11 billion) and time-volunteered (Rs. 29 billion); 54 percent of all giving was given directly to individuals as opposed to 46 percent to organisa-tions. The study further reveals that giving behaviour is primarily determined by religion in Pakistan as more than 90 percent of the donations go to religious organ-isations citing religious faith as a motivation for a vast majority of the people. More recently, PCP (2010) con-ducted a study on philanthropy in Punjab which indi-cated that the total estimated individual giving was Rs. 103.7 billion in 2010. In addition, the role of corporate philanthropy is significant. Total donations by the Public Listed Companies (PLCs) in Pakistan increased eighteen folds from Rs. 228 million in 2000 to Rs. 4.8 billion in 2013 (PCP, 2013).

Introduction

2

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

Over the years, the role of CSOs has evolved from the limited sphere of charitable and philanthropic activities to the wider public welfare-oriented activities to com-plement the state’s efforts in development. CSOs have become more involved in community-based initiatives to improve the quality of life, to help alleviate poverty, and advocate for access to basic human rights. Based on the evidence, CSOs in Pakistan can be categorised into four categories: (i) internationally funded policy research and advocacy organisations; (ii) well-endowed umbrella organisations at the national level which are catalytic and leaders in nature; (iii) the Rural Support Programmes as contractors for government, international donors sup-porting poverty reduction, thrift and saving associations, community development and micro-enterprise develop-ment organisations; and (iv) the foot soldiers - the small community-based organisations which implement and operate projects and schemes (Ismail, 2003). In addition, a number of CSOs of different scale are operating at national level. Most of these organisations are supported by local donors, community contributions and govern-ment funds to promote philanthropic activities at local level.

1.1 Brief Profile of Sindh Province:

Sindh, being the largest province in terms of its popula-tion size comprising of approximately 44.1 million people in 2013 and representing 24 percent of Pakistan’s total population, has a great potential to mobilise philanthro-py to be used for social, economic and cultural growth. Its capital, Karachi, is the country’s largest metropolitan city, and is also the financial and business centre of the country. Sindh has the highest concentration of urban population at 48 percent, as compared to an overall country average of 34 percent in 2013, making it the most urbanised province in the country. Sindh is rich in natural resources; around 60 percent of the country’s oil fields and 44 percent gas fields are located here and it contributes 56 percent oil and 55 percent of Pakistan’s daily gas production. It has one of the largest coal re-serves in the world (185 billion tonnes) and has a seaport that has the potential to generate huge trade, commerce and employment opportunities in the region.

Given a large demographic and socio-economic base, Sindh is still struggling to achieved the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) by the year 2015. Only a few districts, with exceptional performance, are on track to achieving targets in education, in promoting gender equality, women’s empowerment, and increasing access

Key Indicators of Sindh Province*

• PopulationofSindhProvincehasincreasedtoanestimatednumberof44.1millionin2013from30.4millioninthe1998census.

• Theprovinceshares24percentofcountry’stotalpopulationwithanurbancomponentof48percent,andgeneratesabout33percentoftheNationalGDP.

• Theproportionofpopulationlivingbelowthepovertylineisestimatedat33percent.

• Averagehouseholdsizeisclosetothena-tionalaverageof6personsperhousehold.

• Morethanathirdofthechildrenintheprov-inceareunderweight.

• 54.7percentofmalepopulationaged15to19yearshaveenteredthelabourmarket,reflectinglowlevelsoftertiaryeducationalattainment.

• Employmentratevariessignificantlybygen-der,estimatedat51.5percentformalesand11.4percentforfemales.

• Literacyrateisestimatedat72percentformalesand47percentforfemalesintheyear2011-12withacompletionrateof63percentand41percentuptoprimarylevel,respec-tively.

• Primaryschoolsforgirlsconstituteabout30percentofthetotalnumberofnon-function-alschoolsinSindh.

*Source: (Planning Commission, 2013; Government of Sindh and UNDP Pa-kistan, 2012; Government of Sindh, Development Statistics, 2008, Table 2.9, p. 48).

3

Individual Indigenous

to safe drinking water. Poverty in Sindh has remained high with 33 percent of its population living below the poverty line. The proportion of underweight children below 5 years of age is large (40.5 % compared to Na-tional average of 31.5 %). The province also lags behind on other social indicators such as proportion of fully immunised children of 12-13 months (71 % compared to the national figure of 80 %). In fact, the achievements made so far, are already at risk of being undone due to the adverse economic and security situation in the country. Moreover, there are large inter-district varia-tions and gaps within indicators for all MDGs by urban / rural, standard of living index, and gender (Planning Commission, 2013).Given the magnitude of the social sector deficit and given the fiscal and institutional con-straints of the Government, there is a dire need to tap and channelise philanthropy to maximise its benefits for the poor and underprivileged subgroups of population.

This study, based on a household survey and qualita-tive research, aims to document the volume, patterns and motivations for individual indigenous philanthropy in Sindh estimated in the form of cash, in-kind, and time-volunteerism. This will help provide information and evidence for social development policy, especially in areas of social welfare and social safety nets for the poorer segments of society.

The rest of the report is structured as follows: A review of existing literature is presented in Chapter 2, followed by the presentation of conceptual framework and meth-odology in Chapter 3. The findings of both the quan-titative and qualitative research about the prevalence, magnitude and patterns of individual philanthropy in Sindh are reported in Chapter 4 as stated in objectives 1 and 4 of the study. Chapter 5 includes the motivations behind individual giving or why people give to others. Chapter 6 analyses individual giving and safety nets in the context of awareness, constraints, and complemen-tary mechanism, to address objectives 2, 3 and 8 of the study. The final Chapter 7, presents the policy recom-mendations and the way forward for further policy ac-tions to provide a base for future dialogue, and specific measures to boost philanthropy for social development in Sindh.

1.2 Objectives of the Study:

1. To document the extent, size, scope and contri-bution of individual indigenous philanthropy.

2. To examine the relationship between stakehold-ers (grant makers and grant seekers) and identify ways to facilitate productive equations.

3. To identify philanthropy as a complementary mechanism for social safety nets and poverty reduction in the province.

4. To improve and raise awareness of the concept of philanthropy for social investment.

5. To provide reliable and updated data and inform policy makers for designing appropriate policies.

6. To advance the efforts of citizen organisations to achieve and optimise the utilisation of the im-mense private indigenous resource pool for social development.

7. To provide a base for future dialogue, analysis and action for citizen led growth for social devel-opment.

8. To identify constraints and barriers to individual philanthropy and propose / recommend policy and action by the Government of Sindh to re-move such barriers.

4

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

Philanthropy has been a subject of keen interest amongst academia, government bodies, general public and in particular, philanthropic organisations them-selves. A better understanding of the philanthropic be-haviour enables various stakeholders to fulfil their goals and commitment to the charitable sector. This section briefly reviews the existing literature relevant to the ob-jectives of this report to better understand philanthropy in other countries.

Philanthropy is an ancient practice, which is rooted in religious traditions and is the true willingness of an individual to help others. The concept of philanthro-py is broad in scope but the literal meaning is “love for human kind” (Fulton & Blau, 2005). Many scholars have attempted to define the concept of philanthropy through social, demographic, economic and other argu-ments, but religious factors play a vital role in defining individual philanthropic behaviour (Hamdani, Ahmed, & Khalid, 2004). There are countless forms of helping others like charity, giving money to mosque, helping someone in need, saving somebody from a fire, donat-ing body organ to a relative and helping a stranger in an emergency (Schwartz and Howard, 1980). All such acts are likely to ultimately benefit the economy and the society, giving a psychological satisfaction to the giver (Griskevicius et al., 2007; Dunn, Aknin, & Norton, 2008).

Voluntary giving and serving others is the widely ac-cepted definition of philanthropy, and yet there is no universal acceptance of values which promote and drive philanthropy because cultural values vary across societ-ies. Philanthropy, in some organised form, appears in all the major cultural and religious traditions, and it might be argued that philanthropy is an essential defining characteristic of civilised society (Payton, 1988).

Philanthropy is often confused with the related concept of charity, as both involve giving. Charity is used for the relief of an immediate need or lack of something. Philanthropy, on the other hand, has a wider context “for the public benefit.” Historically speaking, the role of temples increased to include the care of the sick, feeding of the hungry and sustenance for the wea-ry, and much later as places of learning and healing (schools and hospitals) as well. These activities were funded through charitable donations thus creating the confusion between charity and philanthropy, both terms often being used synonymously. Yet, this overlap in the meaning and use misses a crucial distinction between

the two words. Charity is aimed at providing immedi-ate relief to someone in need; it does not address the cause of suffering. This commonly occurs in the form of welfare disbursements, where people ‘in need’ are typically provided with food, shelter or money. Philan-thropy has a broad and long-term connotation of ‘social investing’ – actions that move beyond charity towards building human and social capital (Qureshi, 2000). The term Indigenous philanthropy recognises that the primary investors in society – those who channel their human and capital resources towards efforts that will give meaningful social returns – must ultimately come from within. It must also acknowledge the central role of participatory, citizen-led initiatives in effective devel-opment and the strengthening of civil society. Finally, it must reflect the need to foster cooperation and mutual understanding between the three sectors of society –business, citizen and government– to achieve sustain-able social development (AKDN, 2000).

Indigenous needs span areas as diverse as conser-vation, health, youth, education, housing, economic development, poverty, world peace, human rights, arts, employment, sustainable development and social justice. Evidence shows that philanthropy – and increas-ingly indigenous philanthropy – plays a much more significant role in funding non-profit organisations and civil society in the developing world than it does in industrialised countries. In any society, the culture of charitable giving is influenced by moral, social and reli-gious underpinnings. It relates to material conditions of wealth and standards of living which enable people to give for specific causes or purposes. The Asian Devel-opment Bank in its series, Investing in Ourselves: Giving and Fund Raising in Asia, drew on studies on the tradi-tion of giving in India, Philippines, Thailand and Indo-nesia (Asian Development Bank (ADB) and Asia-Pacific Philanthropy Consortium (APPC), 2002). Based on these studies, various comparative statistics were compiled. Similarities between the four countries extended to uniformly high rates of giving to religious organisations. Socio-economic status of the samples only had a small effect on the giving rate. “Feeling of compassion” as a motive for giving had the greatest effect on the aver-age amount given. The study also indicates that despite substantial amounts of donation, formally organised civil society organisations were not significant recipients of household giving.

Literature Review

5

Individual Indigenous

Religion has received ample attention in philanthropic studies. There is rich literature in the sociology of reli-gion on the relationship between religious involvement and giving (Hodgkinson & Weitzman, 1996). Philanthro-py or charity is clearly defined and encouraged by all major religions of the world. Buddhism promotes the practice of Thambun, or giving for merit-making reli-gious purposes, and Thamtaan, or giving to those in need. These concepts are considered the cornerstones of Buddhist philanthropy, as adherence to religious precepts is still a motivating factor for philanthropy amongst Buddhists (ADB & APPC, 2002). Hindus also espouse concepts of social contribution: Datra Datrtva and Daanam Parmrarth. More than this, however, they are also encouraged to perform voluntary service, as Seva is another Hindu concept. Christians practise reli-gious giving through donating a tenth of one’s income which supports a vast array of faith-based charities (Newland, Terrazas, & Munster, 2010).

In Islam, concept of giving is in different forms: a) Zakat, a mandatory tax on wealth meant to be used for pro-viding relief to the indigent, the widow and the orphan; b) Ushr, a mandatory tax on the gross produce from agriculture; c) Fitrana, a mandatory contribution on the occasion of Eid-ul-Fitr (the festival immediately after Ramadan) as a contribution to ensure that the poor and indigent also enjoy the occasion; d) Khairat, the volun-tary giving for charity’s sake; e) Sadaqa, the voluntary giving of charity in expiation of sins or to ward off evil; and f) Qurbani, an in-kind type of giving on the occa-sion of performance of Hajj (Eid-ul-Azha), are all en-shrined in the Holy Quran. The rules governing giving differentiate between charity and philanthropy. Khairat and Sadaqa are charitable in nature as these are to be distributed for the relief of an immediate need. Zakat and Usher, on the other hand, have connotations of philanthropy. These are meant to be used to empower the recipient such that (s) he is able to earn a livelihood, and is, therefore, not listed amongst the needy. This would make the recipient a productive member of soci-ety, thereby contributing to the larger public wellbeing (Ismail, 2003).

2.1Philanthropy in Selected Countries

Evidence suggests that local, indigenous philanthropy in the form of social entrepreneurship, corporate giving, and community foundations reflects local priorities and local needs (Axelrad, 2011). Local businesses in emerg-ing countries are creating formal philanthropic initia-tives, both in their own countries and other developing

country markets. Fundacion Bradesco, for example, is Brazil’s largest foundation and has inspired a wave of corporate foundations in Brazil that has built 40 schools to provide education for some 700,000 children from rural areas and has trained over 6,000 teachers through-out Central and South America. In Pakistan, the Lay-ton Rahmatullah Benevolent Trust (LRBT) is providing corrective eye surgery services to low-income Pakistanis that can save their sight. In Colombia, Fundación Pies Descalzos is helping children and families displaced by violence to rebuild their lives and receive an education. These organisations and thousands others are the face of global philanthropy targeted, immediate, local, and lasting (Adelman, 2009). Despite an overall trend to-wards the increasing number and quality of these foun-dations, there are numerous challenges to further the development of indigenous philanthropy, and, ultimate-ly civil society, in the developing world. In addition to capital accumulation, a sustained level of philanthropy requires passage of time and confidence in one’s politi-cal and economic security. Thus, in countries subject to fluctuating economic performance, private philanthrop-ic giving and indigenous contributions may be subject to change in the long term and must be organised in a way to ultimately help sustain essential social work and strengthen civil society (Axelrad, 2011).

In Asia, societies have developed around small rural communities, which have instilled in the members a sense of kinship and willingness to help each other in times of need. In Indonesia, for instance, a large portion of the population still lives in rural areas, and practises Gotong Royong, the concept of mutual aid. Likewise, the Nepalese have adopted many socio-cultural con-cepts of giving and volunteering. Amongst these are the Muthi Daan, Guthi and Parma. Muthi Daan, liter-ally “giving a handful,” consists mainly of separating a handful of rice or other food grain from the amount taken out for cooking the family meal, and saving it until the quantity reaches a reasonably useful amount to be given to the needy in its original form or converted by the donor into money before handing over to the receiving person or organisation. Guthi, on the other hand, is the concept of extending support to members of the clan or community to which one belongs. Last-ly, Parma is the custom of labour exchange amongst people of mixed age-groups or families, similar to the Indonesian practice of Gotong Royong. The concepts presented above demonstrate how socio-religious culture has influenced the practice and development of philanthropy and volunteerism in the Asian region (ADB & APPC, 2002).

Some further evidence on philanthropy in various de-veloped and developing countries is presented below to highlight factors influencing philanthropy and the motivation behind giving by demographic, gender, and socio-economic status.

6

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

2.1.1

Philanthropy in the United KingdomThe Charities Aid Foundation (CAF, 2012b) survey findings reveal that the total amount donated to charity in 2011/12 was £9.3 billion, showing a decrease of £1.7 billion in cash terms and of £2.3 billion in real terms, after adjusting for inflation. Participation in charitable giving, nevertheless, remains relatively widespread with over half of adults giving in 2011/12, which is equivalent to 28.4 million adults.

Women continue to be more likely to give to charity than men (58 percent compared to 52 percent). In 2011/12, women in the older age brackets (45 years or more) were identified as the largest group of givers (62 percent). The percentage of people giving in manage-rial and professional groups has decreased (66 percent compared to 70 percent in the previous year), as has the amount they give (£17 compared to £20). Giving by cash is the most common method of giving, used by half of all donors in 2011/12. It has been the most common method of giving through all eight years of the survey. As in previous years, the typical amounts given by cheque / card were the largest (£20), and direct debit accounted for the largest share of total donations, representing almost a third (31 percent) of the overall amount given in 2011/12. ‘Medical research’, ‘hospitals and hospices’ and ‘chil-dren and young people’ continue to attract the highest proportions of donors. In 2011/12, medical research was supported by 33 percent of donors and was the most popular cause, as for all previous years of the survey. ‘Religious causes’ attracted the largest donations, on average, with a median amount of £20 per month, and received 17 percent of the overall amount donated.

2.1.2

Philanthropy in Sri LankaThe findings based on a survey commissioned by Asia Pacific Philanthropy Consortium (APPC) in Sri Lanka indicate that 99 percent of the respondents made cash donations and on average, about three to four times a month in the twelve months preceding the survey (APPC, 2007). The percentage of those making in-kind donations about twice a month in the year preceding the survey was also high (93 percent). The majority of respondents (54 percent) volunteered their time, although less frequently (once or twice every month). Across gender and age, both male and female re-

spondents aged between 30-44 years showed higher frequencies of volunteerism across socio-economic classes with a slightly more frequent prevalence of volunteerism amongst males (58 percent vs. 53 per-cent). The highest and lowest socio-economic classes in urban areas were the least inclined to volunteer their time. Beggars (97 percent) and religious organisations (91 percent) are the largest and most-preferred recipi-ents of philanthropy. Majority of rural respondents give to beggars, while younger respondents (25-40 years) are more likely to give to friends and relatives. Older respondents and respondents from urban areas are inclined to give to organisations. The respondents reported giving 2.2 percent of their monthly household income, on average, to organisa-tions as opposed to 1.8 percent of giving to individuals. The most important sources of awareness of philan-thropy amongst the respondents were family traditions (90 percent) and religious traditions (67 percent); the latter being especially true amongst the older groups (45 to 60 years). Younger respondents tended to learn more about philanthropy in schools and from television. The reasons for lack of participation in philanthropic activities as listed by the respondents were lack of time (especially for volunteer work), not being approached properly, lack of information about the causes and not enough appreciation for their participation in philan-thropic activities.

2.1.3

Philanthropy in IndiaIt has been argued that philanthropy in India has tended to be considered synonymous with funding of temples and schools in their villages of origin (Blake et al., 2009). The Indian voluntary sector is large, includ-ing over 1.2 million Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs). Records show that registered donations have increased by almost 150 percent between 2002/2003 and 2006/2007 from Rs. 50 billion to Rs. 123 billion (Bain & Co., 2013). Moreover, Trust activity in India has also increased and the recent financial boom has led to a new wave of family and corporate Trusts and Founda-tions. India still has a large number of people living under immense poverty, estimated at around 40 million below poverty line. With the recent global downturn, the chal-lenge of reducing poverty has become even more mon-umental, pushing an additional 25 million to 40 million below the poverty line. The massive challenge facing India ranges from providing primary education to chil-dren who often are homeless to widespread malnutri-tion and high mortality. The Bain and Co. report, 2013 shows that giving in India totalled close to $5 billion in

7

Individual Indigenous

the year 2006. The Indian philanthropy market when compared with the United States, the World’s leader in giving, shows that Americans make donations totalling more than $300 billion annually, - or about 2 percent of the US gross domestic product. Admittedly, the US is a far more developed economy and its comparison with India has its limits. India has a long way to go, especially as a growing economy with greater accumulation of wealth amongst individuals.

The number of wealthy individuals in India started increasing mostly after the economic reforms of the 1990s. Normally, it takes 50 to 100 years for philan-thropic markets to mature. Today in India, many of those with hard-earned new wealth are not eager to part with even a small amount of their money. As a society, charitable donations do not necessarily win social recognition. Instead, many of the newly wealthy individuals view increased material wealth as the key to improving their social standing. An analysis carried out of high net-worth individuals in India showed that,on average they contribute just around one-fourth of 1 percent of their net worth to social and charitable caus-es (Bain & Co., 2013; CAF, 2012).

Another factor impeding contributions is a belief by donors that support networks are not professionally managed, and as a result, their contributions would not be put to good use or are at the risk of being misappro-priated. Family-owned groups run much of corporate giving in India. Amongst the top 40 business groups, nearly 70 percent are family-owned or controlled enter-prises. It is likely that some families and individuals view corporate social responsibility initiatives as extensions of their own giving and that may curb their interest in making personal donations.

2.1.4

Philanthropy in PakistanPhilanthropy in Pakistan exists in multiple forms in-cluding Zakat, Sadqa, Fitrana, volunteering-time and in-kind gifts and is primarily determined by religion and faith-based giving. Various studies have documented evidence of philanthropic activities and its relation with socio-economic development in Pakistan indicating that giving practices of people generate an immense pool of resources that can be channelised for more pro-ductive purposes (AKDN, 2000;PCP, 2010;PCP, 2012). Moreover Non-profit organisations (NPOs) also play an important role in promoting philanthropic activities in Pakistan. A study conducted on NPOs in Pakistan shows that the annual cash revenue received by NPO sector is Rs. 16,400 million in cash and Rs. 135 million in-kind (Ghaus-Pasha, Jamal, & Iqbal, 2002). The indige-nous philanthropy component consists of 37 percent of

the total cash revenue, and the major contributors are private individuals with a share of 34 percent. The share of foreign private philanthropy is estimated at 6 percent of the cash revenue, while the public sector contributes only 4 percent of in-kind revenue. The major activi-ties carried out by these organisations are focused on education and research, health, housing, civil rights and advocacy.

Another notable feature of philanthropy in Pakistan is that a substantial amount of giving goes to individu-als as opposed to organisations. The Punjab study on individual philanthropy (2010) shows that 63 percent of all monetary giving in Punjab is directed to individ-uals and the remaining 37 percent to institutions. This preference for giving to individuals rather than organi-sations has certain implications for social development programmes which need to be studied further to better understand the barriers and constraints faced by the individuals in making philanthropic contributions. This study, therefore, aims to examine the patterns of indi-vidual giving in Pakistan and suggests ways to optimise the benefits of philanthropy through appropriate pro-grammes and policy actions.

8

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

3.1Conceptual Framework The conceptual framework used in this study is based on the philosophy that in Pakistan (Sindh as well), like in other parts of the world, charity and philanthropy are often used interchangeably. According to Bekkers and Wiepking (2011) philanthropy is “the donation of money to an organisation that benefits others beyond one’s own family”. Charity tends to be short-term, and emotional with an immediate response, focused primarily on rescue and relief, whereas philanthropy is long term, more strategic, and is focused on rebuilding

– the means by which individuals and non-profit organ-isations achieve their mission of social well-being and development of society, at large. For this study, philan-thropy is defined as the individuals donation of mon-ey, time and in-kind goods to help others directly or through organisations, thereby estimating the volume of philanthropy in three major forms of giving. Accord-ing to this definition, there are two ways to help others i.e. direct from individual to individual and indirect from individual to organisations.

Religion creates a specific ‘morality’ in its believers and this morality is visible in every act of the individual believer. Davidson and Pyle (1994) find that stronger religious beliefs are positively related to religious contributions, whereas Hamdani, Ahmad and Khalid (2004) argue that religious factor plays a vital role in determining the individuals philanthropic behaviour in Pakistan. Islam has placed considerable importance to promote the philanthropic behaviour - charity is one of the highest virtues and is considered a means of cleansing oneself spiritually and materially. Admonitions on charity and philanthropy in the Quran stress familiar virtues: “They will question you concerning what they should bestow voluntarily. Say: ‘Whatever good thing you bestow is for parents and kinsmen, orphans, the needy and strangers and whatever good you do, God has knowledge of it” (Quran 2:211). “You will not attain true piety until you voluntarily give of that which you

love and whatever you give, God knows of it” (Quran 3:86). The sayings and doings of the Prophet Muham-mad (peace be upon him) also stress the importance of giving to others in the form of Zakat, Sadaqat, Fitrana, Khairat, Qurbani and other charities.

Islam encourages the rich to spend for the benefits of the collective good that ultimately promotes philan-thropy. Religion leads to charitable behaviour not only because of communal monitoring, but also because of the sense of supernatural monitoring (Israel & Brown, 2013). Such satisfaction is received in kindness, broth-erhood, co-operation and caring for human beings in the society. This, according to the teachings of Islam, is ultimately the source of receiving the pleasure of Allah. Islam guides its followers to a binding commitment to help others. Commitment is an enduring desire to maintain a valued relationship (Sargeant, Ford, & West, 2006), and it always involves some degree of self-sac-rifice. Figure 3.1 shows that commitment driven by religion encourages people to have an attitude to help others through charity / philanthropy.

Individual behaviour to help others is also shaped by other socio-economic factors. Factors that influence direct help include altruism, and an individual’s (giver’s) characteristics, whereas indirect help includes aware-ness of the needs and the attitude of the charitable organisations (Webb, Green, & Brashear, 2000; Pilia-vin & Chang, 1990; Hoge, 1995; Moore, Bearden, & Teel, 1985; Bennett & Sargeant, 2005; Sargeant et al., 2006; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). It is further argued by Sargeant et al. (2006) that direct help is mediated by the level of commitment while indirect help by the level of trust, particularly on charitable organisations. Both the level of commitment and trust determine the individual’s philanthropic behaviour. Trust refers to the extent of belief that a charity will be utilised as expect-ed and would fulfil its obligations. Hence, trust, com-mitment and giving behaviour are related sequentially

- higher levels of trust and commitment improve the likelihood that an individual would help others. Individ-ual philanthropy behaviour is, thus, mediated by both

Conceptual Framework and Methodology This chapter outlines the conceptual framework of the study deriving its major components from review of liter-ature on philanthropy and describes how individual giving behaviour is shaped and determined by a set of so-cio-economic and religious factors. The methodology of the study including the sample design, data collection process and methods employed to analyse data are also presented in detail.

9

Individual Indigenous

IndividualPhilanthropy

AwarenessOf Need

OrganisationalReputation

Trust

Altruism

Commitment

GivingBehaviour

IndividualCharacteristics

Religion

Figure 3.1:Conceptual Framework

10

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

commitment and trust (Figure 3.1). Altruism plays a significant role in modelling philanthropy. Altruism is perceived as a cognitive activity, an attitude to help others (Brewer, 2003; Frydman et al., 1995) and a desire to improve another’s condi-tion (Karylowski, 1982). In essence, attitude towards helping others is called altruism. Altruism is driven by empathy, compassion, pity, sympa-thy and sentiment. These factors make you desire the good of other people because this augments your satisfaction. These also induce one to help the other person or to give something to him / her when the cost is compensated by the relief or sense of moral or social properness (Kolm, 2006). Altruism, influenced by religion and individual / house-hold characteristics determines the giving behaviour through commit-ment (Figure 3.1). Religious people are more tuned with compassion and sympathy. They are more likely to participate in welfare activities to enhance the collective welfare of the society (Chau et al., 1990). Hence, religion influences the giving behaviour of an individual directly as well as through altruism (Figure 3.1).

A variety of individual characteris-tics such as age, gender, socio-eco-nomic status, and education can also influence philanthropic be-haviour (Sargeant et al., 2006). Evi-dence shows that there is a positive relationship between the level of education and giving. Higher levels of education are also associated with giving a higher proportion of income (Schervish & Havens, 1997; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). Various mechanisms to explain the relation-ship between education and giving would include awareness of needs, socialisation, costs and values. Awareness of needs and the expo-sure to information about charitable causes and purposes are likely to be higher amongst the higher educat-ed. Brown (2005) found that higher education increases donations be-cause it draws people into member-ships, while Bekkers (2006) shows

that higher education is related to giving to a variety of specific causes through generalised social trust and enhanced confidence in charitable organisations. Thus, educated and well-off people are likely to be more committed to giving. The literature has shown that the relationship be-tween age and philanthropy is also positive, but the exact age at which the age gradient becomes weaker varied from study to study (Bekkers, 2006; Bekkers & Wiepking, 2011). These individual characteristics can influence philanthropy through commitment as portrayed in Figure 3.1. Educated and well-off people are likely to be more committed to giving.

Awareness of the need to support an individual or organisation is a prerequisite for philanthropy. A sur-vey study on intentions to donate to international relief organisations, reveals a positive effect of the awareness of need for philanthropic behaviour (Cheung & Chan, 2000). The relationship between individu-als and charitable organisations is mediated primarily by trust. People are more willing to donate to an organisation which they trust more. Figure 3.1 indicates awareness of the need either work through com-mitment for individual philanthropy or through trust for organisational philanthropy. The other important factor that influences the philanthro-py behaviour especially organisation at philanthropy is the reputation of the organisation. Charitable organ-isations with good reputation may attract more giving and vice versa. Figure 3.1 portrays that reputation generates the element of trust and confidence amongst the charitable organisations and the donors. If donors perceive that the donation is spent on the right cause, they are more willing to donate to organisa-tions.

In short, individual giving is influ-enced by Islamic belief (religion), mediated through altruism, trust and commitment. The Individual Indigenous Philanthropy Survey in

Sindh (IIPS), 2013 provides relevant information to examine the role of religion, socio-economic factors, altruism, trust and commitment on the giving behaviour of individuals.

3.2Methodology

To achieve the objectives of this study, a mix study design was employed using both quantita-tive and qualitative techniques to collect data on various dimensions of individual philanthropy in Sindh. Quantitative technique consisted of a cross-sectional household survey - named as the Individual Indigenous Philanthropy Survey in Sindh (IIPS) 2013. Information was collected at household level by a respondent aged 18 years and above in each household. Qualitative technique included Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with prominent community stakeholders and representatives of the CSOs along with In-depth Interviews (IDIs) with the relevant government officials.

3.2.1

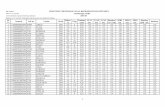

Sample DesignFor the household survey, PCP co-ordinated with the Sindh Bureau of Statistics (SBS), Karachi to prepare the study design and the sample frame of the Primary Sampling Units (PSUs). Based on the urban area frame updated through the eco-nomic census conducted in 2003, each city / town has been divided into mutually exclusive PSUs consist-ing of 200-250 households called Secondary Sampling Units (SSUs) which are identifiable through a sketch map. Each PSU in large cities (Karachi, Hyderabad and Sukkur) has been classified into three cat-egories of income groups i.e., low, middle and high, keeping in view

11

Individual Indigenous

the living standard of the majority of people. In rural areas, list of Goths / Dehs developed through the 1998 Population Census was used as sample frame, each one identifiable by its name.

A two-stage stratified sample design was adopted for the survey and stratification plan was divided into two domains described below: Karachi, Hyderabad and Sukkur were considered as large sized cities called Self Representative Cities (SRCs). Each of these cities constituted two strata, first, Karachi and, second, Sukkur and Hyderabad together. Both have further been sub-stratified according to low, mid-dle and high-income groups. After excluding population of large sized cities, the remaining urban popula-tion in each district in all the prov-ince has been grouped together to form a stratum called ‘other urban’. Each district of Sindh was treated as independent stratum.

To determine the sample size for this survey, analytical studies were used to calculate the sample size. Keeping in view the objectives of the survey, a sample size of 3,000 households comprising of 60 PSUs was estimated to provide reason-able and precise indicators of the survey. The allocation of the PSUs and the sampled households for urban and rural areas are shown below in Table 3.1. The PSUs were selected from strata / sub-strata with Probability Proportion to Size (PPS) method of sampling technique. Households within the sampled PSUs were taken as Secondary Sam-pling Units (SSUs). Latest household listing was prepared for this study in the selected PSUs. Fifty households

from each sampled PSU of rural and urban area were selected, using systematic sampling technique with a random start. In order to prevent bias and make the data representa-tive of the entire population, survey weights were applied to compen-sate for over- or under-sampling of specific areas or for disproportion-ate stratification. For this purpose, designed weights2 were used. The percentage distribution of sampled households is portrayed in Figure 3.2 for urban and rural areas in Sindh. The figure shows that 55 percent of households (1650) were interviewed from rural areas, and 45 percent from urban areas (1350).

3.2.2

Research ToolsA structured questionnaire was used after the pilot test, to gather information at the household level on: (i) socio demographic charac-teristics of the survey households, (ii) awareness about the religious / social organisations and institutions / personalities for philanthropy, (iii) preference / attitudes for various types of organisations / institutions, (iv) philanthropic practices includ-ing (a) involvement with religious / social organisations-volunteered or paid, (b) worked voluntarily himself / herself for the welfare of individuals, (c) Zakat and Ushr to organisations / institutions and to individuals in cash or kind and (d) donations other than Zakat made to organisations / institutions and to individuals in cash or kind.

Table 3.1: Sampled PSUs and SSUs in total, urban and rural areas: IIPS Sindh 2013

Unit of selection Urban Rural Total

Primary Sampling Units (PSUs) 27 33 60

Secondary Sampling Units (SSUs) households 1350 1650 3000

55%

45%

Rura

lU

rban

Figure 3.2: Percentage distribu-tion of the sampled households by rural-urban areas: Sindh 2013

2. ‘Designed Weight’ is the product of the inverse probabilities of selection of PSU within domain and selection of HH within listed HH in a particular block, finally this product is multiplied by the number of segment(s) generated.

12

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014

For the qualitative component, separate structured guidelines were prepared for FGDs and IDIs. In all, six FGDs were conducted in three major SRCs of Sindh namely, Kara-chi, Hyderabad and Sukkur with two FGDs in each city.

The target population of the FGDs was members of local communi-ty. The average size of a FGD was comprised of 10-20 participants. In addition, six IDIs with CSOs, and six with relevant government officials were carried out to seek answers to some questions relevant to the objectives of the study.

3.2.3

Data Collection and ProcessingFor the purpose of data collection from the 3000 sampled households, four teams were formed and each team consisted of 1 supervisor and 11-12 enumerators. Data collection was completed in a time period of 4 months (February to May 2013). For qualitative data collection, research team members from PCP carried out FGDs and IDIs. The field supervisors were deputed to monitor data collection. They were responsible for ascertaining timely completion of the survey question-naires, spot checking to ensure that each questionnaire was correctly filled and completed, and editing of the questionnaires at the end of the day. The team leader / senior programme officers were involved in monitoring and questionnaire editing. The project staff of PCP performed on-site monitoring and supervision.

The data collected was first edited and validated in the field by the enumerators themselves, and then by the field supervisor to rectify any misreporting or other errors. Cod-ing, editing and data cleaning by a qualified data processing profes-

sional in Islamabad followed the process. The data was entered in Statistical Package for Social Scienc-es (SPSS). Data was collected in the field using specific questionnaires by the research team and was checked regularly to ensure minimal data entry errors. Afterwards, data was analysed using SPSS, STATA and Microsoft Excel.

3.3Method ofAnalysisThe quantitative analysis was carried out in three steps. The first was the estimation of the size and volume of individual giving in Sindh consisting of cash donations (Zakat as well as non-zakat payments), time volun-teered and in-kind gifts. Besides cash donations (Zakat and non-zakat), volunteered time was re-ported in hours by the respondents in the sample households which was converted into monetary value

13

Individual Indigenous

using an average rate of Rs. 50 per hour based on account of the minimum daily wage of a worker. An approximate monetary value was given to in-kind donations to get the total magnitude of individual giving. Thus, the total individual giv-ing in Sindh is the sum of the above mentioned three components: cash donations (Zakat and non-zakat), value of time volunteered and value of in-kind gifts. Weights, based on urban and rural population of the province were applied to get the total volume of individual giving in Sindh.

In the second step, patterns of individual giving were examined by differentiating between giving to individuals and organisations, controlling for socio-demographic characteristics of the givers. Mo-tivation behind giving or why do people give to others was analysed in the third step using both the bivariate and multivariate tech-niques. In the bivariate analysis, five socio-demographic characteris-tics of the respondents and their households were used i.e gender, area or place of residence (rural / urban), age, educational attainment and expenditure quintile. Per capita expenditure was used to construct five expenditure quintiles repre-senting different socio-economic status. The first quintile represents the poorest household, while the fifth represents the richest house-holds in the sample. Pearson Chi Square test was used to find out any significant association between the socio-demographic characteristics of the household and preference or motivation for giving. The findings of the qualitative research were used extensively to support the information gathered through the questionnaires from the household survey.

Multivariate analyses were also carried out to quantify the de-terminants of individual giving to both individuals and organisations. Conceptual framework provides the basis for multivariate analysis.

The following empirical model was used for the analysis:Two types of giving - Non-zakat payment and time-volunteered to individuals and organisations were used in multivariate analyses as dependent variables. In this regard, commitment was represented by religion and altruism, while trust referred to awareness about charita-ble organisations and their reputa-tion.

For the qualitative data, thematic content analysis was applied to the FGDs and IDIs. This was done in a step-wise method. At first, the data was segmented according to the questions asked and was filtered out i.e., the information related to the research objectives was extract-ed from it. At the second stage, the responses of the people were put together and the data was coded. These codes were grouped together to develop sub-categories, major categories and finally the themes. At the final stage, the themes were interpreted and described accord-ing to the views given by the re-spondents. To ensure the quality of analysis, the codes were developed from the condensed meaning units followed by subcategories, catego-ries and the final themes.

3.4Data Limitations

No research can claim to be with-out limitations. Two types of errors affect the estimates from a sample survey: non-sampling errors and sampling errors. Non-sampling errors arise in compiling and pro-cessing the data, while the sampling errors are the result of shortcomings

in the sample selection of the study. Some limitations in the present study need to be kept in mind while interpreting the results; these are:First, in urban Sindh, particularly Karachi where about half of Sindh’s total population resides and has large potential of philanthropic contribution seems to be under-rep-resented in the sample. As reported earlier only three PSUs were includ-ed in the sample reflecting that the representation of Karachi in total urban sample of the study is low. It is likely that the response rate of high-income groups not only from Karachi but also from other major cities of Sindh was low, thereby un-derestimating the volume of philan-thropy in Sindh.

Second, the geographical coverage of the Sindh Study, which consists of only 33 rural and 27 urban PSUs seems to be low (Table 3.1). In each selected PSU of the survey, 50 households were interviewed, whereas in other nationally rep-resentative surveys, less than 20 households were generally inter-viewed in one PSU for better geo-graphical spread and coverage. The coverage of 27 PSU in urban Sindh with 50 households in each PSU has limited spread and heterogeneity in selected households.

Third, it is important to note that this study does not give a full picture of philanthropy in Sindh, because its scope is limited only to individual giving. Other sources of giving in Sindh, e.g. family foun-dations, corporate giving, Zakat disbursed by the Zakat department of Sindh Government are not part of the individual giving reported in this study.

Giving = f ( personal character-istics, education,

commitment, trust )

14

Philanthropy in Sindh 2014