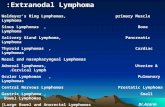

PET–CT of Extranodal Lymphoma

Transcript of PET–CT of Extranodal Lymphoma

AJR:182, June 2004

1579

ymphoma, mainly non-Hodgkin’slymphoma, may be extranodal inorigin in approximately 40% of

patients. Extranodal involvement may also bedue to regional spread of nodal disease or he-matogenous dissemination [1]. FDG positronemission tomography (PET) imaging hasbeen shown to be an important technique for

both staging and follow-up of nodal and ex-tranodal lymphoma [2]. PET–CT systems,which enable the performance of PET andCT data acquisition at the same setting with-out changing the patient’s positioning, havebeen recently introduced in clinical practice[3]. Lesions are characterized on the fusedPET–CT images by both their metabolic sta-

tus and their anatomic details. Such fusioncan also assist in the differentiation of physio-logic and tumoral sites of FDG uptake. Ouraim is to show the use of FDG PET–CT im-aging in extranodal lymphoma involving var-ious structures and organs. The relevant CT,PET, and fused PET–CT images of each il-lustrative case will be presented.

PET–CT of Extranodal Lymphoma

Ur Metser

1

, Odelia Goor

2

, Hedva Lerman

1

, Elizabeth Naparstek

2

, Einat Even-Sapir

1

Received July 18, 2003; accepted after revision October 21, 2003.

1

Department of Nuclear Medicine, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, 6 Weizman St., Tel-Aviv 64239, Israel. Address correspondence to U. Metser.

2

Department of Hematology, Tel-Aviv Sourasky Medical Center, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv 64239, Israel.

AJR

2004;182:1579–1586 0361–803X/04/1826–1579 © American Roentgen Ray Society

Pictorial Essay

L

A B

Fig. 1.—23-year-old man with extranodal chest and peritoneal involvement of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. PET–CT scan was obtained at presentation. Later findings resolved onfollow-up PET–CT after chemotherapy. A, Fusion PET–CT axial image shows consolidation due to lymphoma in both lungs (arrowhead), with chest wall extension (thick arrow) and pleural mass (thin arrow).B, Fusion PET–CT axial image obtained in upper abdomen shows subtle peritoneal mass (arrow) anterior to liver, indicating peritoneal involvement.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by G

azi U

nive

rsite

si o

n 08

/14/

14 f

rom

IP

addr

ess

194.

27.1

8.18

. Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

1580

AJR:182, June 2004

Metser et al.

A B

Fig. 2.—27-year-old woman with stage IV non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and presumed lymphomatous mass in breast. A, CT axial image shows soft-tissue attenuating mass in right breast (arrowhead). B, Corresponding FDG PET axial image shows presumed lymphomatous breast mass (arrowhead). Follow-up scan (not shown) obtained 4 months later, after chemotherapy,showed resolution of findings.

Fig. 3.—74-year-old man with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving liver and spleen.Coronal fused PET–CT image shows focal deposit in liver (arrowhead) and diffuseincreased FDG uptake in spleen (arrow), indicating splenic involvement. Findingswere confirmed on contrast-enhanced CT (not shown).

A B

Fig. 4.—52-year-old man with histologically proven non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving nodes above and below diaphragm, with infiltration of tumor along liver ligaments. A, Axial FDG PET image shows lymphomatous mass (arrowhead) in region of liver. Also note focal right pleural involvement. B, Axial fused PET–CT image shows tumor mass (arrowhead) extending along ligamentum venosum.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by G

azi U

nive

rsite

si o

n 08

/14/

14 f

rom

IP

addr

ess

194.

27.1

8.18

. Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

PET–CT of Extranodal Lymphoma

AJR:182, June 2004

1581

Thorax

Lung

Secondary involvement of the lungs is threetimes more frequent in Hodgkin’s disease thanin non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, usually because ofextension of disease from involved hilar and me-diastinal nodes. Peripheral subpleural masses orconsolidations without mediastinal adenopathycan occur in both Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [4].

Pleura and Pericardium

Pleural effusion is common but rarely indi-cates pleural involvement. Pleural-based lym-phomatous masses are less common [1] and

are frequently overlooked on conventional im-aging. Pericardial disease arises from lym-phatic or hematogenous spread or by directextension of mediastinal tumor [1].

Thymus

Although 30–50% of patients with Hodgkin’sdisease have thymic enlargement at presen-tation, actual involvement of the thymus withlymphoma is rare and difficult to assesson imaging.

Chest Wall

Anterior mediastinal adenopathy, especiallyin the internal mammary chain, may extend into

the chest wall (Fig. 1A). Thoracic spine involve-ment is often secondary to posterior extensionof posterior mediastinal adenopathy.

Breast

Primary breast lymphoma accounts for only0.1–0.5% of all breast tumors [5]. The diagnosisof primary breast lymphoma depends on the ab-sence of concurrent widespread lymphoma(with the exception of ipsilateral axillary nodes)and no previous diagnosis of extramammarylymphoma. Otherwise, it is considered second-ary involvement. No imaging criteria are avail-able to distinguish primary breast lymphomafrom other neoplasms of the breast (Fig. 2).

A B

Fig. 5.—55-year-old man with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma secondarily involving bowel. A, Axial CT image shows soft-tissue attenuating mass (arrows) encasing segment of small bowel in right lower quadrant of abdomen. B, Corresponding fusion PET–CT image shows abnormal uptake of FDG in soft-tissue mass (arrows), indicating lymphomatous involvement. Findings resolved on follow-up PET–CT (not shown) after chemotherapy.

Fig. 6.—44-year-old woman with recurrent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving retroperi-toneal lymph nodes. Axial fusion PET–CT image shows invasion of left kidney through leftrenal hilum (arrowhead), confirmed on contrast-enhanced CT (not shown).

Fig. 7.—77-year-old man with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Coronal PET–CT image showsFDG-avid soft-tissue attenuating left renal masses (arrows). Note abnormal FDG uptakein retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Renal findings resolved on follow-up scan (not shown)obtained after chemotherapy.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by G

azi U

nive

rsite

si o

n 08

/14/

14 f

rom

IP

addr

ess

194.

27.1

8.18

. Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

1582

AJR:182, June 2004

Metser et al.

Abdomen and Pelvis

Spleen

The spleen is frequently involved in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and in one third of pa-tients with Hodgkin’s disease [6]. It may be theonly site of abdominal disease in 10% of pa-tients with Hodgkin’s disease. Splenomegalyis not a reliable indicator of disease because

the organ’s size is normal in one third of pa-tients with splenic disease.

Liver

Only 5% of patients with Hodgkin’s diseasehave liver involvement, almost always withsplenic involvement, but up to 15% of patientswith non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma have liver dis-ease [7]. Hepatomegaly is suggestive of diffuse

liver infiltration, and focal liver disease may re-semble metastatic disease on imaging (Fig. 3).Occasionally, lymphomatous infiltration maybe seen extending from the porta hepatis alongthe margins of the portal veins (Fig. 4).

Pancreas

Lymphomatous involvement of the pancreasis unusual but is well documented in the

A B

Fig. 8.—76-year-old man with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving retro-peritoneal nodes, spermatic cord, and testis.A, Maximum-intensity-projection PET view shows retroperitoneal lym-phadenopathy and lymphomatous involvement of serpentine structure inright groin and scrotum, conforming to path of right spermatic cord, epi-didymis (arrows), and testis (arrowhead). B, Sagittal fused PET–CT image confirms location of abnormality in sper-matic cord, epididymis (arrows), and testis (arrowhead). Absence ofbowel in scrotal sac depicted on CT excludes hernia with loops of bowelin it as possible cause for abnormal FDG uptake. Findings were confirmedon sonography (not shown).

A B C

Fig. 9.—64-year-old man with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and extranodal involvement of skeleton (biopsy proven) and adrenal glands.A, Axial fused PET–CT image shows bilateral lymphomatous deposits (arrowheads) in adrenal glands. Adrenal masses resolved after therapy (not shown). Note involve-ment of L1 vertebral body (arrow).B, Coronal CT image shows no detectable abnormality.C, Coronal fused PET–CT image shows diffuse patchy bone marrow involvement in axial and peripheral skeleton (e.g., T11 vertebral body [arrow]). Note abnormally in-creased uptake of FDG (arrowhead) in center of pelvis shown to be in segment of normal-appearing bowel on CT. Therefore, this uptake was presumed to represent phys-iologic FDG uptake in bowel.

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by G

azi U

nive

rsite

si o

n 08

/14/

14 f

rom

IP

addr

ess

194.

27.1

8.18

. Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

PET–CT of Extranodal Lymphoma

AJR:182, June 2004

1583

A B

Fig. 10.—39-year-old man with histologically proven non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of bone. A, Axial CT image shows subtle increased attenuation (arrow) in left iliac bone. B, Corresponding PET image shows lymphomatous involvement of left iliac bone (arrow). Follow-up scan (not shown) obtained after chemotherapy 3 months later showedresolution of findings on PET and CT.

11 12

Fig. 11.—74-year-old woman with non-Hodgkin’slymphoma. Fused PET–CT axial image showslymphomatous deposit in right parotid gland (ar-rowhead) and in small right neck nodes (arrow).Findings resolved on follow-up PET–CT scan(not shown) obtained after chemotherapy.

Fig. 12.—66-year-old woman with histologicallyproven non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of brain. FusedPET–CT axial image shows right parasagittalmass (arrow).

Fig. 13.—60-year-old man with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and spinal cord compression.A, Axial CT image shows right paravertebral mass (arrowheads) extending through right thoracic intervertebral foramen to invade epidural space.B, Fused PET–CT image shows abnormal FDG uptake in right paraspinal and epidural mass (arrowheads), indicating tumor involvement.

A B

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by G

azi U

nive

rsite

si o

n 08

/14/

14 f

rom

IP

addr

ess

194.

27.1

8.18

. Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

1584

AJR:182, June 2004

Metser et al.

literature [1]. On imaging, a large mass maybe seen with extrapancreatic extension. Whenbelow the renal vessels, associated lymphade-nopathy is far more common in lymphoma thanin adenocarcinoma of the pancreas.

Gastrointestinal Tract

The gastrointestinal tract is the mostcommon site of primary extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, accounting for up to10% of extranodal disease at diagnosis [8]. Asingle segment of gut is involved without dis-

tant lymph node involvement, except forlymph nodes draining the involved segment.Secondary involvement of the gastrointestinaltract is common (Fig. 5), usually extendingfrom adjacent nodal masses. Multiple seg-ments may be involved.

Peritoneum and Omentum

Peritoneal or omental infiltration by lym-phoma is seen almost exclusively in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Peritoneal lymphomamimics peritoneal carcinomatosis with ascites,

peritoneal nodules, and occasionally omentalinfiltration (Fig. 1B).

Genitourinary Tract

Genitourinary tract involvement is unusualat presentation. The most common organs in-volved are the testes, followed by the kidneys.Although only 3% of patients have renal in-volvement at diagnosis, the incidence in recur-rent high-grade non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma ishigher. There are four CT imaging patterns, themost frequent of which is multiple hypodense

A B

Fig. 14.—81-year-old woman with biopsy-proven orbital non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. A, Axial CT image shows right orbital soft-tissue attenuating mass (asterisk). B, Corresponding PET image shows tumor mass (asterisk) in right orbit.

A B

Fig. 15.—32-year-old woman with history of uterine lymphoma 8 years earlier, who presented with progressive paraparesis (more on left) and progressing dysphagia, di-agnosed as biopsy-proven neurolymphomatosis. After chemotherapy, patient improved clinically, and findings resolved on subsequent PET–CT scan.A, Axial PET image of brain shows increased FDG uptake (arrow) in left cerebellopontine angle.B, Sagittal PET image shows increased FDG uptake (arrow) in upper neck on left.(Fig. 15 continues on next page)

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by G

azi U

nive

rsite

si o

n 08

/14/

14 f

rom

IP

addr

ess

194.

27.1

8.18

. Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

PET–CT of Extranodal Lymphoma

AJR:182, June 2004

1585

nodules (which may be hyperdense on unen-hanced CT) followed by extension from retro-peritoneal adenopathy (Fig. 6). A solitary massindistinguishable from renal cell carcinoma(Fig. 7) and diffuse infiltration are less com-monly seen [9].

Testicular lymphoma accounts for 5% oftesticular tumors and is the most common tes-ticular tumor in patients older than 60 years.The testes may be the only site of disease or asite of recurrence. Bilateral involvement maybe seen in up to 38% of cases. Concomitant in-volvement of the epididymis and spermaticcord (Fig. 8) and the skin and central nervoussystem is common [1].

Adrenal Gland

The adrenal gland is involved in 4% of pa-tients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Adre-nal lymphoma is bilateral in 50% of thesecases (Fig. 9A) and may cause adrenal insuf-ficiency [10]. Nonlymphomatous bilateraladrenal hyperplasia has been described in as-sociation with lymphoma and should be dif-ferentiated from tumoral involvement.

Musculoskeletal System

Bone and bone marrow involvement mayoccur in both Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The skeleton is a fre-

quent site of relapse. Bone marrow infiltrationmay be a site of a primary disease (stage IE) ormore often part of a disseminated disease(stage IV), found in up to 40% of patients withnon-Hodgkin’s lymphoma at presentation(Fig. 9B). Bone marrow involvement inHodgkin’s disease at presentation is rare butmay be seen in 5–34% of patients later duringthe course of disease.

Primary lymphoma of bone is almost exclu-sively due to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, usu-ally involving a single bone [1] (Fig. 10).Secondary involvement of bones, mostly theaxial skeleton, may be seen in both non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and Hodgkin’s disease.

C D

Fig. 15. (continued)—32-year-old woman with history of uterine lymphoma 8 years earlier, who presented with progressive paraparesis (more on left) and progressing dys-phagia, diagnosed as biopsy-proven neurolymphomatosis. After chemotherapy, patient improved clinically, and findings resolved on subsequent PET–CT scan.C, Fused PET–CT image shows extension of FDG uptake (arrow) through jugular foramen. MRI findings (not shown) were normal. Because of clinical history of dysphagiaand path of increased FDG uptake on fusion PET–CT images, this uptake was presumed to represent lymphomatous infiltration along left tenth cranial nerve.D, Coronal fused PET–CT image shows abnormal FDG uptake (arrow) along thoracolumbar spine and along origins of intervertebral nerves, representing lymphomatousinvolvement.E, Axial PET image (L3–L4) shows abnormal FDG uptake (arrows) in paravertebral location (more on left). This uptake was proven by fusion image (not shown) to be alongorigins of intervertebral nerves.F, Corresponding axial CT image shows relative thickening of left nerve root (arrow).

E F

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by G

azi U

nive

rsite

si o

n 08

/14/

14 f

rom

IP

addr

ess

194.

27.1

8.18

. Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved

1586

AJR:182, June 2004

Metser et al.

The use of PET obviates performing bonescintigraphy [11]. The disease may extend intothe adjacent soft tissue or present as a separateintramuscular mass.

Head and Neck

Unlike Hodgkin’s disease, extranodal lym-phoma of the head and neck region is relativelycommon in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, ac-counting for approximately 5% of head andneck tumors.

The most common site of involve-ment is Waldeyer’s ring: the lymphoid tissue inthe nasopharynx, oropharynx, and tonsils. Theparotid gland is the most commonly involvedsalivary gland (Fig. 11). Most cases of thyroidnon-Hodgkin’s lymphoma arise in a back-ground of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. It may bedifficult to distinguish between lymphoma andthyroiditis on the basis of fine-needle aspirates.Mediastinal and retrosternal extension is associ-ated with a worse prognosis [1].

Nervous System

Primary central nervous system lymphomaoccurs almost exclusively in the brain’s whitematter (Fig. 12). Increase in its incidence hasbeen coupled with the rise in frequency of im-munocompromised conditions. Secondary lym-phoma occurs in up to 15% of patients with

non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma but is rare inHodgkin’s disease. The extracerebral spacesand the epidural and subarachnoid spinal spacesmay be involved [1]. Compression of the spinalcord or cauda equina may be seen because ofextension of nodal disease through the interver-tebral foramina [12] (Fig. 13).

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the orbit isthe most common primary orbital malig-nancy in adults (Fig. 14). Retrobulbar lym-phoma is an infiltrative process, causingophthalmoplegia and proptosis [1]. Second-ary orbital lymphoma may be seen in up to5% of patients with lymphoma.

Infiltration of the peripheral or cranial nervesis a rare condition, termed “neurolymphomato-sis.” Clinically, patients may present with pe-ripheral or cranial neuropathy. CT or MRI mayshow nerve enlargement or enhancement be-yond the dural sleeve. Recently, a case of neuro-lymphomatosis was diagnosed using PET–CT[13] (Fig. 15).

References

1. Armitage JO, Mauch PM, Harris NL, Bierman P.Lymphomas: extranodal sites. In: DeVita VT, Hell-man S, Rosenberg SA, eds.

Cancer: principles andpractice of oncology

, 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lip-pincott Williams & Wilkins, 2001:2300–2316

2. Moog F, Bangerter M, Diederichs CG, et al. Extra-nodal malignant lymphoma: detection with FDG

PET versus CT.

Radiology

1998;206:475–481 3. Hany TF, Steinert HC, Goerres GW, Buck A, von

Schulthess GK. PET diagnostic accuracy: im-provement with in-line PET-CT system—initialresults.

Radiology

2002;225:575–5814. Filly R, Blank N, Castellino RA. Radiographic

distribution of intrathoracic disease in previouslyuntreated patients with Hodgkin’s disease andnon-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Radiology

1976;120:277–281

5. Giardini R, Piccolo C, Rilke F. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas of the female breast.

Can-cer

1992;69:725–7356. Kadin ME, Glaststein EJ, Dorfman RE. Clinico-

pathologic studies in 117 untreated patients sub-ject to laparotomy for the staging of Hodgkin’sdisease.

Cancer

1971;27:1277–12947. Sandrasegaran K, Robinson PJ, Selby P. Staging

of lymphomas in adults.

Clin Radiol

1994;49:149–161

8. Brady LW, Asbell SO. Malignant lymphoma of thegastrointestinal tract.

Radiology

1980;137:291–2989. Charnsangavej C. Lymphoma of the genitourinary

tract.

Radiol Clin North Am

1990;28:865–87710. Paling MR, Williamson BR. Adrenal involvement

in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

AJR

1983;141:303–305

11. Moog F, Kotzerke JK, Reske SN. FDG PET can re-place bone scintigraphy in primary staging of malig-nant lymphoma.

J Nucl Med

1999;40:1407–141312. Zimmerman RA. Central nervous system lym-

phoma.

Radiol Clin North Am

1990;28:697–72113. Trojan A, Jermann M, Taverna C, Hany TF. Fu-

sion PET-CT imaging of neurolymphomatosis.

Ann Oncol

2001;13:802–805

Dow

nloa

ded

from

ww

w.a

jron

line.

org

by G

azi U

nive

rsite

si o

n 08

/14/

14 f

rom

IP

addr

ess

194.

27.1

8.18

. Cop

yrig

ht A

RR

S. F

or p

erso

nal u

se o

nly;

all

righ

ts r

eser

ved