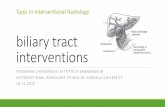

Percutaneous biliary interventions through the …...Pictorial Review Percutaneous biliary...

Transcript of Percutaneous biliary interventions through the …...Pictorial Review Percutaneous biliary...

lable at ScienceDirect

Clinical Radiology 69 (2014) 1304e1311

Contents lists avai

Clinical Radiology

journal homepage: www.cl in icalradiologyonl ine.net

Pictorial Review

Percutaneous biliary interventions through thegallbladder and the cystic duct: What radiologistsneed to knowA. Hatzidakis a, P. Venetucci b, M. Krokidis c,*, V. Iaccarino b

aDepartment of Medical Imaging, University Hospital of Heraklion, Heraklion, GreecebDepartment of Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology, University Hospital “Federico II”, Naples, ItalycDepartment of Radiology, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Cambridge, UK

article information

Article history:Received 13 May 2014Received in revised form24 July 2014Accepted 28 July 2014

* Guarantor and correspondent: M.E. Krokidis,Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Trust, HillsUK. Tel.: þ44 1223 348920; fax: þ44 1223 21784

E-mail address: [email protected] (M. K

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2014.07.0160009-9260/� 2014 The Royal College of Radiologists.

Percutaneous cholecystostomy is an established drainage procedure for the management ofhigh-risk patients with acute cholecystitis. However, percutaneous image-guided access to thegallbladder may not be limited to the simple placement of a drain, but may also be used as analternative approach to the biliary tree through the catheterization of the cystic duct, for avariety of other more complicated conditions. Percutaneous transcholecystic interventionsmay be performed in both malignant and benign disease. In the case of malignant jaundice, thetranscholecystic route may be used when the liver parenchyma is occupied by metastaticlesions and transhepatic access is not possible. In benign conditions, access through thegallbladder may offer a solution if the biliary tree is not dilated. The transcholecystic accessmay then be route of insertion of large sheaths, internal drainage catheters, lithotripsy devices,stone retrieval baskets, and stents. The purpose of this review is to illustrate the techniquesand to discuss the indications, complications, and technical difficulties of this alternativeaccess to the biliary tree.

� 2014 The Royal College of Radiologists. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

Image-guided percutaneous gallbladder drainage wasintroduced into clinical practice in the early 1980s,1e3

however, it was not until the 1990s that the majority ofradiologists became more familiar with the technique andthe first case reports were published.4e10 Since then, themethod has been widely used and offers a valid solution inselected patients with an acutely inflamed and obstructedgallbladder.11e17

Department of Radiology,Road, Cambridge CB2 0QQ,7.rokidis).

Published by Elsevier Ltd. All righ

Percutaneous transcholecystic access to the biliary treemay be performed after image-guided puncture of thegallbladder and subsequent catheterization of the cysticduct and the common bile duct (CBD), with a guidewire.12,17e19 The procedure may be used in a variety ofmalignant and benign conditions.20e22 The purpose ofthis review is to illustrate the main percutaneous trans-cholecystic access techniques and to discuss the indications,complications, and technical difficulties of this alternativeaccess to the biliary tree.

Indications

Indications for percutaneous transcholecystic access tothe biliary tree are mainly conditions of obstruction of the

ts reserved.

A. Hatzidakis et al. / Clinical Radiology 69 (2014) 1304e1311 1305

CBD (benign or malignant) that are either not associatedwith dilated ducts or where the transhepatic approach isnot feasible due to diffuse liver disease (cysts or metasta-ses). Further indications may be the necessity of stentplacement in the cystic duct and failed endoscopicsphincterotomy or stone removal in patients with acutepancreatitis.4,5,11,12,22 Several reports have been publisheddescribing catheterization through the cystic duct and theplacement of an external biliary drain or alternativelycatheterization of the obstruction of the CBD and theplacement an internal drain.16,17,23e25 Yasumoto et al.18

described lack of intrahepatic duct dilatation and historyof gastrectomy as the main indications for transcholecysticaccess and stent deployment in the CBD. The indications forinterventions through the gallbladder and the cystic ductare listed in Table 1.12,16,17,21e25

Techniques

Two access routes are described for percutaneous chol-ecystostomy: the transhepatic and the transperitoneal.26 Nosignificant difference in complication rates is reported be-tween the two access routes.14,15 Themain reported benefitsof the transhepatic route are reduction in the risk of bileleakage, greater catheter support, and quicker maturationof the tract.15,19,27 Disadvantages, such as higher rate ofbleeding, pneumothorax, and fistula formation, have alsobeen reported.28 The transperitoneal route is preferred forpatients with bleeding disorders or those with diffuse liverdisease.

Premedication and sedation may be used. Most of theauthors use 1e2 mg midazolam and 50e100 mg fentanylintravenously. Fasting for 6 h is required if sedation isadministered.

Ultrasound-guided puncture and the Seldinger tech-nique are used by the majority of operators. There might bea risk of minor bile leakage with the Seldinger techniqueduring the needleedilatorecatheter exchange manoeu-vres.11,19,27 The kit that is most commonly used has a 22 Gaccess needle, through which a 0.01800 wire is introduced.When the wire is within the gallbladder the system is

Table 1Indications for interventions through the gallbladder and the cysticduct.11,15e20

1. Benign or malignant CBD disease in a patient with an already existingcholecystostomy

2. Benign or malignant CBD disease in a patient with contraindication fortranshepatic puncture

3. Benign or malignant CBD disease in a patient after failed orcontraindicated endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography/percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography, including acutepancreatitis

4. Malignant jaundice due to obstruction of the distal CBD, presenting asacute cholecystitis

5. Acute cholecystitis due to cystic duct malignant infiltration, fordecompression and cystic duct stenting

6. Acute cholecystitis due to cystic duct obstruction, caused by anoccluded metallic stent of the CBD, for decompression and cystic ductstenting

CBD, common bile duct.

upsized to 0.03500 with the use of a coaxial introducer(Fig 1). Another approach may be with the use of CT guid-ance, which reduces the risk of pneumothorax, and with aCT cholangiogram the precise anatomy of the cystic ductmay be delineated. Once access to the gallbladder is ob-tained, an 8.5 F drainage locking pigtail catheter is advancedover the 0.03500 wire and left in situ for a few days. In thisway, the gallbladder is decompressed and wire manipula-tion and catheterization of the cystic duct is more feasible.In the series of Yasumoto et al.,18 stent deployment in theCBD was performed after a mean time of 10.4 days (range5e21 days). Tract maturation is also important to avoid bileleak. If the transhepatic route is used, the tract is maturedwithin 2 weeks of the initial access. For access via thetransperitoneal route, at least 3 weeks are required; tractfistulographymay be performed prior to anymanoeuvres toconfirm the presence of a mature and stable fistula.15

To access the cystic duct, fluoroscopy and real-timefluoroscopic imaging are required. A cholangiogram isinitially performed preferably with diluted contrast me-dium, in order to confirm the CT findings. The drainagecatheter is then exchanged over a stiff wire to a 6 or 7 Fsheath, preferably with a Britetip. The use of a second safetyguide wire as a “buddy wire” outside the sheath is recom-mended in case access is lost due to the lack of support fromthe gallbladder, which may occur even with a mature tract.The “buddy-wire” technique requires that two wires areinserted through the sheath and the sheath is then retractedand re-inserted over one of the twowires so that the secondwire remains within the gallbladder as a separate access.The sheath may also be secured with a stitch to the skin toincrease support during catheterewire manipulations.

A short 4 or 5 F angled catheter (Fig 1) may be introducedthrough the sheath, and a stiff hydrophilic wire may be usedto navigate the tortuous cystic duct. After crossing the cysticduct, the catheter is advanced to the CBD. Depending on theunderlying disease, the CBD may also be crossed with the

Figure 1 Access kit for transcholecystic interventions: (a) 22 G nee-dle, (b) 0.01800 wire, (c) coaxial access system, (d) 0.03500 stiff wire, (e)6 F brite tip sheath, (f) 4 F biliary manipulation catheter.

Figure 2 (a) A 68-year-old male high-surgical risk patient due to a recent aorto-coronary bypass was admitted in septic status with a gallbladderabscess with pericholecystic expansion. The abscess was drained with a 12 F pigtail catheter. Follow-up 2 days later with MR cholangiographyshows the catheter in a peri-cholecystic location. The presence of stones and evidence of inflammation of the papilla was also revealed. (b) Threeweeks later, the patient was stable and a 10 F introducer sheath was positioned in the peri-cholecystic cavity. Guide wire introduction within thegallbladder was possible. The CBD was catheterized via the transcystic route and the presence of a distal CBD stone that was obstructing thepapilla was confirmed (arrow). (c) The sphincter was dilated with a 10 mm balloon and the stone is then pushed easily towards the duodenum.Finally, a biliary transcholecystic drain was left in situ. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed at a later stage.

A. Hatzidakis et al. / Clinical Radiology 69 (2014) 1304e13111306

same guide wireecatheter combination and access to theduodenum may be obtained. In cases of a tight CBD occlu-sion, further guide wire support may be required and alarger and stiffer catheter may be used.17,18

After crossing the papilla of Vater, the hydrophilic guidewire needs to be exchanged with a super-stiff one, whichstraightens the tortuous cystic duct and provides thenecessary support for insertion of a longer sheath.18

Through the longer sheath or over the super-stiff wire,metallic stents or special lithotripsy baskets can then beadvanced easily in most cases (Figs 2e9).

Figure 3 (a) A 70-year-old male high-surgical risk diabetic haemodialysicholecystostomy was performed with excellent clinical outcome. Cholangiof the intrahepatic bile ducts due to external compression on the distalcholecystostomy catheter reveals the presence of a large pancreatic headhistory of pancreatitis. (c) Percutaneous CT-guided drainage of the pseudoof an internal biliary draining catheter was performed in order to decomfully drained without re-filling through the pancreatic ducts and no CBDsimple cholecystostomy pigtail catheter, which remained closed for 1 wecatheters were retrieved.

Procedure limitations

The main limitations of percutaneous transcholecysticaccess to the biliary tree are due to anatomical reasons thatmay decrease the technical success of interventionsthrough the gallbladder and the cystic duct. These are ma-lignant infiltration or occlusion from a stone of the cysticduct/CBD junction; very tortuous cystic duct; cystic duct ofsmall calibre (<2 mm), which would increase the difficultyof advancing a metallic stent or a balloon catheter; thepresence of Heister valves, which may be challenging to

s patient presented with acute acalculous cholecystitis. Percutaneousography 2 days later reveals gallbladder sludge and marked dilatationCBD. (b) CT with injection of diluted contrast medium through thepseudocyst responsible for the CBD obstruction. The patient denied

cyst was performed during the same session. Subsequently, placementpress the dilated biliary tree. Three months later the pseudocyst wascompression was noticed. The biliary catheter was replaced with a

ek. During that period the patient remained symptom free and both

A. Hatzidakis et al. / Clinical Radiology 69 (2014) 1304e1311 1307

cross with a guide wire; and finally, elevated mobility of thegallbladder due to lack of support from the surroundingorgans.18,21 Catheterization of the cystic duct can be tech-nically difficult as it is tortuous and the spiral valves ofHeister are present. In the early years van Sonnenberget al.,5 successfully catheterized the cystic duct in only twoof the five patients in whom the procedure was attempted.In a more recent study, Miyayama et al.,16 failed to pass

Figure 4 (a) A 30-year-old male patient with a body mass index >30,was admitted after a car accident with stable liver trauma and mul-tiple bilomas. Several surgical draining catheters were placed.Through the cholecystostomy catheter, a diagnostic catheter wasadvanced in the cystic duct and cholangiography revealed contrastmedium extravasation in the right liver lobe. The left bile duct systemwas not adequately opacified. (b) After percutaneous transhepaticbiliary drainage, an 8 F biliary catheter was placed. Cholangiographydetected complete transection of the left main bile duct (arrow).Cholecystostomy catheter was retrieved 2 weeks later after tractmaturation.

through a cystic duct that was infiltrated with tumour, andtherefore, cholecysto-choledochostomy was the onlypossible way to the CBD.16 After this experience, the samegroup used amicrocatheter in the three subsequent cases inorder to pass through the infiltrated cystic duct via trans-cholecystic access.12 Krokidis et al.,17 advanced a hydro-philic wire through the spiral valves and towards the CBD inthe first attempt assuming that the cystic duct was not

Figure 5 (a) A 75-year-old male patient, in poor general condition,with jaundice and coagulopathy. MR cholangiography shows distalocclusion of the distal CBD, dilatation of the entire biliary tree andenlarged hydropic gallbladder in anterior deflection. The findingssuggested pancreatic head tumour. (b) An operable pancreatic masswas confirmed and biliary drainage was requested before pancrea-tectomy and biliodigestive anastomosis. Due to patient’s coagulop-athy percutaneous cholecystostomy with subsequent transcystic CBDdrainage was performed. The patient was then operated withoutpostoperative complication.

A. Hatzidakis et al. / Clinical Radiology 69 (2014) 1304e13111308

infiltrated with tumour.17 They experienced some difficultyin passing through the malignant stricture in the infiltratedpapilla.

A highly mobile gallbladder is usually the result of a verylow transperitoneal puncture,27 a rather long and tortuoustransperitoneal tract, or an immature cholecystostomytract.15 In order to avoid a highly mobile gallbladder,percutaneous placement of anchors can be introduced priorto initial drainage.29,30

Technical problems

Technical problems are usually related to long, non-mature, or tortuous cholecystostomy tracts; thin ortortuous cystic ducts with tight valves of Heister; poorsupport of the introduced catheter and wire; and difficultanatomical configuration. Solutions to these problems varyand include allowing a longer period to enable tractmaturation,15 use of special anchoring devices of the gall-bladder,27,29,30 and repeated sessions in case of failure. Newaccess from a different angle may be used if no other so-lution is feasible.

Figure 6 (a) An 83-year-old woman with severe ischaemic heart diseaseupper abdominal pain and a cholecysto-cutaneous fistula. The fistula was cfor acute cholecystitis. CT revealed inflammation of the gallbladder and thadvanced through the cutaneous fistula and another subhepatic drainagegallbladder catheter was slightly displaced. Cholangiography revealed fre(arrow). (c) Transcholecystic 10 mm � 2 cm balloon insertion; the papilla oThe final result was considered successful and all the drainage catheters

In cases of significant wire bulking due to acute angula-tion or tight stenosis of the CBD or of periampullary diver-ticula, the “rendezvous” procedure may be considered, aspreviously described.31 Stents may be difficult to advancethrough cystic ducts. This issue needs to be taken intoconsideration when the type of stent is selected and stentswith a low-profile (6 F) carrying a catheter need to be thefirst-line approach, unless a covered stent needs to bedeployed in the distal CBD.17 Other technical issues may berelated to the proximal margin of the stent. The landingzone needs to be in a healthy segment of the CBD; therefore,only low strictures may be stented via the cystic duct.

Technical success and complications

The technical success rate of percutaneous chol-ecystostomy for acute cholecystitis is very high, and wasreported to be >85% in a recent review article comprising53 published studies including 1918 patients.32

The largest series in the literature for metallic stentdeployment through the cystic duct provides informationon 15 patients with malignant obstruction of the distal

and recurrent episodes of septicaemia was admitted with acute rightaused 1 year earlier due to a surgical cholecystostomy catheter placede surrounding area. (b) A percutaneous cholecystostomy catheter wascatheter was placed, with good clinical outcome. One week later, thee passage of the cystic duct and presence of a stone in the distal CBDf Vater was dilated and the stone was pushed into the duodenum. (d)were removed.

Figure 7 An 85-year-old male patient with dementia, in poor generalcondition, was admitted with symptoms of acute cholecystitis, chol-angitis, and jaundice. Ultrasonography revealed biliary tree dilatationwith signs of gallbladder inflammation and distal CBD stones.Percutaneous cholecystostomy was performed with good clinicalresult. Cholangiography showed a patent cystic duct and confirmedthe CBD stones. Internalization of the drain without external bag wasdecided, in order to avoid catheter displacement. Two weeks laterpatient underwent successful endoscopic stone removal and thedrainage catheter was removed.

A. Hatzidakis et al. / Clinical Radiology 69 (2014) 1304e1311 1309

CBD.18 A 100% technical success rate was reported with aclinical success rate of 93% (14/15). Stent patency is nodifferent than that of any other biliary stent series and isreported as 297 days (range 7e982 days). Early stent

Figure 8 (a) An 80-year-old female patient with severe respiratory insufficholecystitis. Ultrasonography revealed biliary tree dilatation with signsseveral distal CBD stones. Percutaneous cholecystostomy was performedgallbladder stone, a patent cystic duct, one large and one small CBD stoperformed with help of an endoscopic basket. Subsequently, internalizatioSurgical or endoscopic treatment was not feasible is this case. Also percutTwo weeks later, the patient underwent placement of a metallic stent thdenum; the stones were pushed away from the papilla of Vater. Subsequyear later from another cause.

occlusionwas due to sludge formation andwas treatedwiththe deployment of a second stent.

Complications after percutaneous cholecystostomyoccur in 3e13% of cases and are usually minor.27 The maincomplaint from patients during the procedure is pain,which can be controlled by intravenous administration ofanalgesics.18 A common minor complication is cathetermigration, which occurs in approximately 8.6% of thecases.28 Major complications, such as bile peritonitis, sig-nificant haemorrhage, and haemo- or pneumothorax affect<5% of patients.27,28 In high surgical risk patients with acutecholecystitis, a high (15e25%) rate of mortality is reported,due to the extensive co-morbidities, the poor general con-dition of the patient, and advanced underlying disease.27,32

Procedure-related mortality is very low at <0.4%.32 Thereare no reported complications caused by the catheterizationof the cystic duct. Nevertheless, perforation of the cysticduct and haemobilia are possible adverse effects. Thesecomplications are usually self-limiting and need no furtheraction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the transcholecystic approach of thebiliary tree is safe and technically feasible. After negotiationof the cystic duct, various interventional techniques, such asbiliary stenting and lithotripsy are possible with high suc-cess and low complication rates. These procedures can beadded to the percutaneous image-guided armamentariumand can be considered as valid alternative treatment op-tions for patients with advancedmalignant or benign biliarydisease.

ciency and Alzheimer’s disease was admitted with symptoms of acuteof gallbladder inflammation and presence of gallbladder lithiasis andwith good clinical result. Cholangiography showed one relative smallne (arrows). (b) Percutaneous removal of the gallbladder stone wasn of the drain was decided, in order to avoid catheter displacement. (c)aneous lithotripsy of the large CBD stone was considered challenging.rough the cystic duct and the CBD with the distal end into the duo-ently, the cholecystostomy catheter was removed. The patient died 1

Figure 9 (a) A 62-year-old male patient in poor clinical condition wasadmitted with jaundice. A very large pancreatic head tumour wasdetected at CT with obstruction of the intra- and extrahepatic biliaryducts. Due to coagulopathy, percutaneous drainage of the hydropicgallbladder was decided. (b) Two weeks after the initial drainage,the catheter was exchanged with a long internal biliary drain thatwas advanced through the cystic duct, and because the duodenumwas compressed by the mass the catheter was further advancedwithin the proximal jejunum. The patient underwent surgery2 weeks later.

A. Hatzidakis et al. / Clinical Radiology 69 (2014) 1304e13111310

References

1. Elyaderani M, Gabriele OF. Percutaneous cholecystostomy and cholan-giography in patients with obstructive jaundice. Radiology 1979;130:601e2.

2. Shaver RW, Hawkins IF, Soong J. Percutaneous cholecystostomy. AJR Am JRoentgenol 1982;138:1133e6.

3. Radder RW. Ultrasonically guided percutaneous catheter drainage forgallbladder empyema. Diagn Imaging 1980;49:330e3.

4. Picus D. Percutaneous gallbladder intervention. Radiology 1990;176:5e6.5. Van Sonnenberg E, D’Agostino HB, Casola G, et al. The benefits of

percutaneous cholecystostomy for decompression of selected cases ofobstructive jaundice. Radiology 1990;176:15e8.

6. Vingan HL, Wohlgemuth SD, Bell III JS. Percutaneous cholecystostomydrainage for the treatment of acute emphysematous cholecystitis. AJRAm J Roentgenol 1990;155:1013e4.

7. Van Sonnenberg E, D’Agostino HB, Casola G, et al. Gallbladder perfora-tion and bile leakage: percutaneous treatment. Radiology 1991;178:687e9.

8. Vogelzang RL, Nemcek AA. Percutaneous cholecystostomy: diagnosticand therapeutic efficacy. Radiology 1988;168:29e34.

9. McGahan JP, Lindfors KK. Percutaneous cholecystostomy: an alternativeto surgical cholecystostomy for acute cholecystitis? Radiology1989;173:481e5.

10. vanSonnenberg E, Casola G, Varney RR, et al. Interventional radiology inthe gallbladder. RadioGraphics 1989;9:39e49.

11. Hatzidakis AA, Prassopoulos P, Petinarakis I, et al. Acute cholecystitis inhigh-risk patients: percutaneous cholecystostomy vs conservativetreatment. Eur Radiol 2002;12:1778e84.

12. Miyayama S, Yamashiro M, Takeda T, et al. Acute cholecystitiscaused by malignant cystic duct obstruction: treatment withmetallic stent placement. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2008;31(Suppl.2):S221e6.

13. Garber SJ, Mathleson JR, Cooperberg PL, et al. Percutaneous chol-ecystostomy: safety of the transperitoneal route. J Vasc Interv Radiol1994;5:295e8.

14. Van Overhagen H, Meyers H, Tilanus HW, et al. Percutaneous chole-cystectomy for patients with acute cholecystitis and an increased sur-gical risk. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1996;19:72e6.

15. Hatjidakis AA, Karampekios S, Prassopoulos P, et al. Maturation of thetract after percutaneous cholecystostomy with regard to the accessroute. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1998;21:36e40..

16. Miyayama S, Matsui O, Akakura Y, et al. Percutaneous chol-ecystocholedochostomy for cholecystitis and cystic duct obstruction ingallbladder carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2003;14:261e4.

17. Krokidis ME, Hatzidakis AA. Percutaneous transcholecystic placement ofan ePTFE/FEP-covered stent in the common bile duct. Cardiovasc Inter-vent Radiol 2010;33:639e42. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00270-009-9585-8.

18. Yasumoto T, Yokoyama S, Nagaike K. Percutaneous transcholecysticmetallic stent placement for malignant obstruction of the common bileduct: preliminary clinical evaluation. Vasc Interv Radiol 2010;21:252e8.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvir.2009.10.010.

19. Sheiman RG, Stuart K. Percutaneous cystic duct stent placement for thetreatment of acute cholecystitis resulting from common bile duct stentplacement for malignant obstruction. J Vasc Interv Radiol2004;15:999e1001.

20. Dawson SL, Girard MJ, Saini S, et al. Placement of a metallic biliaryendoprosthesis via cholecystostomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1991;157:491e3.

21. Harding J, Mortimer A, Kelly M, et al. Interval biliary stent placement viapercutaneous ultrasound guided cholecystostomy: another approach topalliative treatment in malignant biliary tract obstruction. CardiovascIntervent Radiol 2010;33:1262e5.

22. K€uhn JP, Busemann A, Lerch MM, et al. Percutaneous biliary drainage inpatients with nondilated intrahepatic bile ducts compared with patientswith dilated intrahepatic bile ducts. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:851e7.

23. Hickey NA, Kiely P, Farrell TA, et al. Biliary stent placement via percu-taneous non-surgical cholecystostomy. Clin Radiol 1998;53:915e6.

24. Ramsey D, Newland C. Biliary stent placement via percutaneous non-surgical cholecystostomy. Clin Radiol 1999;54:628.

25. Ramsay DW, Newland CJ, Townson GA, et al. Cholecystostomy: an un-usual approach to stenting of a distal common bile duct stricture. Eur JGastroenterol Hepatol 1999;11:1429e30.

26. Iaccarino V, Niola R, Porta E. Percutaneous cholecystectomy in thehuman: a technical note. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 1988;11:357e9.

27. Ginat D, Saad WE. Cholecystostomy and transcholecystic biliary access.Tech Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;11:2e13.

A. Hatzidakis et al. / Clinical Radiology 69 (2014) 1304e1311 1311

28. VanSonnenberg E, D’Agostino HB, Goodacre BW, et al. Percutaneousgallbladder puncture and cholecystostomy: results, complications, andcaveats for safety. Radiology 1992;183:167e70.

29. Cope C. Percutaneous subhepatic cholecystostomy with removable an-chor. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1988;151:1129e32.

30. Lopera JE, Kirsch D, Qian Z, et al. Percutaneous transcholecystic biliaryinterventions using gallbladder anchors: feasibility study in the swine.Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2005;28:467e71.

31. Benerjee B, Harshfield DL, Teplick SK. Percutaneous transcholecysticapproach to the rendevouz procedure when transhepatic access fails. JVasc Interv Radiol 1994;5:895e8.

32. Winbladh A, Gullstrand P, Svanvik J, et al. Systematic review of chol-ecystostomy as a treatment option in acute cholecystitis. HPB (Oxford)2009;11:183e93.