Pentavalent Antimonials Combined with Other Therapeutic...

Transcript of Pentavalent Antimonials Combined with Other Therapeutic...

Review ArticlePentavalent Antimonials Combined with OtherTherapeutic Alternatives for the Treatment of Cutaneous andMucocutaneous Leishmaniasis: A Systematic Review

Taisa Rocha Navasconi Berbert,1 Tatiane França Perles de Mello,2

Priscila Wolf Nassif,1 Camila Alves Mota,1 Aline Verzignassi Silveira,3

Giovana Chiqueto Duarte,4 Izabel Galhardo Demarchi ,5

SandraMara Alessi Aristides,5 Maria Valdrinez Campana Lonardoni ,5

Jorge Juarez Vieira Teixeira,5 and Tha-s Gomes Verziganassi Silveira 5

1Graduate Program in Health Sciences, State University Maringa, Avenida Colombo, 5790 Jardim Universitario, 87020-900,Maringa, PR, Brazil

2Graduate Program in Bioscience and Physiopathology, State University Maringa, Avenida Colombo, 5790 Jardim Universitario,87020-900Maringa, PR, Brazil

3Medical Residency, Santa Casa de Sao Paulo, R. Dr. Cesario Mota Junior, 112 Vila Buarque,01221-900 Sao Paulo, SP, Brazil

4Undergraduation Course in Medicine, State University Maringa, Avenida Colombo, 5790 Jardim Universitario,87020-900Maringa, PR, Brazil

5Department of Clinical Analysis and Biomedicine, State University Maringa, Avenida Colombo, 5790 Jardim Universitario,87020-900Maringa, PR, Brazil

Correspondence should be addressed toThaıs Gomes Verziganassi Silveira; [email protected]

Received 31 August 2018; Revised 19 November 2018; Accepted 5 December 2018; Published 24 December 2018

Academic Editor: Markus Stucker

Copyright © 2018 Taisa Rocha Navasconi Berbert et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative CommonsAttribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work isproperly cited.

The first choice drugs for the treatment of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis are pentavalent antimonials, sodiumstibogluconate, or meglumine antimoniate.However, the treatment with these drugs is expensive, can cause serious adverse effects,and is not always effective. The combination of two drugs by different routes or the combination of an alternative therapy withsystemic therapy can increase the efficacy and decrease the collateral effects caused by the reference drugs. In this systematic reviewwe investigated publications that described a combination of nonconventional treatment for cutaneous and mucocutaneous withpentavalent antimonials. A literature review was performed in the databases Web of Knowledge and PubMed in the period from01st of December 2004 to 01st of June 2017, according to Prisma statement.Only clinical trials involving the treatment for cutaneousor mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, in English, and with available abstract were added. Other types of publications, such as reviews,case reports, comments to the editor, letters, interviews, guidelines, and errata, were excluded. Sixteen articles were selected andthe pentavalent antimonials were administered in combination with pentoxifylline, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulatingfactor, imiquimod, intralesional sodium stibogluconate, ketoconazole, silver-containing polyester dressing, lyophilized LEISH-F1protein, cryotherapy, topical honey, and omeprazole. In general, the combined therapy resulted in high rates of clinical cure andwhen relapse or recurrence was reported, it was higher in the groups treated with pentavalent antimonials alone. The majorityof the articles included in this review showed that cure rate ranged from 70 to 100% in patients treated with the combinations.Serious adverse effects were not observed in patients treated with drugs combination.The combination of other drugs or treatmentmodalities with pentavalent antimonials has proved to be effective for cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and for mostseemed to be safe. However, new randomized, controlled, and multicentric clinical trials with more robust samples should beperformed, especially the combination with immunomodulators.

HindawiDermatology Research and PracticeVolume 2018, Article ID 9014726, 21 pageshttps://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9014726

2 Dermatology Research and Practice

1. Introduction

Leishmaniasis is an important zoonosis around the world,being reported that about 20,000 to 30,000 deaths occurannually as a consequence of the disease [1]. The mostfrequent form is cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), which ispresent in several countries, mainly in the Americas, theMediterranean basin, the Middle East, and Central Asia. Anannual occurrence of 0.6 to 1.0 million new cases is estimated[2] and around 399 million of people are at risk of infectionin 11 high-burden countries [1].

The pentavalent antimonials, sodium stibogluconate ormeglumine antimoniate, are drugs commonly used to treatcutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. However, thetreatment with these drugs is expensive and can cause seriousadverse effects, such as cardiac toxicity and elevation inthe levels of hepatic enzymes [3–5], and, sometimes, it isineffective or presents low cure rates [6, 7]. AmphotericinB, pentamidine, fluconazole, and miltefosine can be used assecond choice drugs, but they also exhibit toxicity. Moreover,the efficacy of the treatment also depends on the Leishmaniaspecies involved in the infection, since some species are moreresistant to some drugs [6].

Local therapies, such as cryotherapy, CO2laser, ther-

motherapy, and photodynamic therapy, are alternatives toconventional drugs, since they are less toxic to the patientand the main adverse effects are restricted to the site ofapplication [8–13]. However, the exclusive use of local therapyis controversial, since some New World species can lead tomucosal leishmaniasis after primarily cutaneous lesions [3].

The combination of two drugs or the combination of alocal therapy with systemic therapy can be an alternative toincrease the efficacy of local therapy and may decrease thecollateral effects caused by the reference drugs. Some studieshave evaluated the efficacy of this type of combination [14–17], being necessary prospective and multicenter studies forsafer evidence. Our central question was evaluated if thecombination of an alternative therapy with meglumine anti-moniate presents more efficiency that only meglumine anti-moniate in the treatment of cutaneous and mucocutaneousleishmaniasis. In this sense, we investigated published articlesthat used the combination of an alternative therapy withpentavalent antimonials in the treatment of cutaneous andmucocutaneous leishmaniasis through systematic review.

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Search. A literature review was performed inthe databases Web of Knowledge and PubMed, consideringthe period from 01st December 2004 to 01st June 2017according to Prisma statement [18].The screening of the titlesand abstracts was performed by researchers (TRNB, CAM,PWN, TFPM, GCD and AVS). The MeSH (Medical SubjectHeadings) terms, strategy used for the search on PubMed,were also selected by these researchers based on publicationson the topic at PubMed. Any disagreements were decided byconsensus. The MeSH terms were validated by two experts(JVT and TGVS) and were divided into two groups: Group1 “Antiprotozoal Agents” OR “Combined Modality Therapy”

OR “DrugTherapy, Combination” OR “Treatment Outcome”OR “Amphotericin B” OR “Meglumine” OR “ProtozoanVaccines” OR “Organometallic Compounds” OR “AntimonySodium Gluconate” OR “Antimony” OR “Pentamidine” OR“Anti-Infective Agents” OR “Medication Therapy Manage-ment” OR “Complementary Therapies”; AND Group 2“Leishmaniasis”OR “Leishmania”.The research in theWeb ofKnowledge database was carried out by topic, which ensuresgood sensitivity.

2.2. Inclusion, Exclusion Criteria, and Studies Selection. Arti-cles that describe a combination of therapeutic alternativeswith pentavalent antimonials for cutaneous or mucocuta-neous leishmaniasis were included in this review. Only origi-nal clinical trials, in English and with abstract available, wereadded. Other types of publications (reviews, case reports,comments to the editor, letters, interviews, guidelines, anderrata) were excluded. After the search the papers initiallyselected were analyzed by the researchers of group 1 (TRNB,CAM, PWN, TFPM, GCD, and AVS) and disagreementsabout inclusion or exclusion of articles were decided byconsensus. To increase the search sensitivity, the researchersin group 1 checked all references from the selected publica-tions to retrieve other unidentified publications in the otherphases of the search. The validation of selected articles wasperformed by four independent evaluators of group 2 (TGVS,MVCL, SMAA, and IGD).

2.3. Data Extraction. The structure of the topics to composethe tables was organized by researchers from group 1 with thesupport of two experts (TGVS and JVT): Table 1 (study, areacountry, study design, period of study, age range or mean inyears, gender, clinical forms, patients enrolled, leishmaniasisdiagnosis, and statistics); Table 2 (study, Leishmania species,treatment, patients at the end, percentage of clinically healedpatients or lesions, percentage of therapy failure, and percent-age of relapse or recurrence); Table 3 (treatment, side effectspercentage, and study source); and Table 4 (treatment, dose,route of administration, time efficacy, safety, practice/clinicalimplications, and study source).The tables were completed byresearchers in group 1 and then checked by researchers fromgroup 2.

3. Results

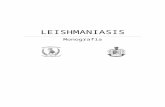

Based on the inclusion criteria defined by consensus, 16articles were selected, being from Iran (6), Peru (4), Brazil(4), Yemen (1), and Afghanistan (1) (see Figure 1). In all,1,302 patients aged between 1 and 87 years were involved inthe studies, with cutaneous or mucocutaneous leishmaniasis,being predominant the cutaneous form of the disease. Themost reported species of Leishmania were L. braziliensis, L.tropica, and L. major (Table 1).

In the selected articles, pentavalent antimonials were ad-ministered in combination with different drugs or treatmentmodalities, which were pentoxifylline; granulocyte macro-phage colony-stimulating factor; imiquimod; intralesionalsodium stibogluconate; ketoconazole; nonsilver-containing

Dermatology Research and Practice 3

Table1:Ba

selin

echaracteristicso

fclin

icaltrialsinclu

dedin

thea

nalysis

ofcombinatio

nsforthe

treatmento

ftegum

entary

leish

maniasis.

Stud

ysource

Area,

Cou

ntry

Stud

ydesign

Period

ofstud

yAge

rang

e,mean(years)

Gen

der

Clin

ical

form

Patie

nts

enrolle

dLe

ishm

aniasisd

iagn

osis

Statistic

s

Alm

eida

etal.,2005

Bahia,Brazil

Open-label

clinicaltrial

NR

14-25,18

Male6

0%Female4

0%Cu

taneou

s5

ClinicalandLabo

ratory

(skintest,

andiso

latio

nin

cultu

re)

No

Arevaloetal.,2007

Lima,Peru

Com

parativ

estudy;

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

8/2005–10/2005

18-87,34.9

Male5

5%Female4

5%Cu

taneou

s20

ClinicalandLabo

ratory

(microscop

y,cultu

re,

and/or

PCR,

and

Mon

tenegroskin

test)

Yes

Brito

etal.,2017

Bahia,Brazil

Rand

omized

-con

trolledtrial

12/2010–

10/2013

18-62

Predom

inance

ofmale

Cutaneou

s162

Clinicalandlabo

ratoria

l(Leishmaniaskin

test,

and/or

histo

patholog

y,cultu

reandPC

R)

Yes

El-Sayed

&Anw

ar,

2010

Sanaa,Yemen

Com

parativ

estudy;

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

6/2006

–6/200

712-50,23.5

Male5

3.3%

Female4

6.7%

Cutaneou

s30

ClinicalandLabo

ratory

(smearfor

amastig

otea

ndtissuec

ulture)

Yes

Farajza

fehetal.,2

015

Iran

Rand

omized

clinical

trial

2011-2012

2-60

,18.52

Male3

4Female3

6NR10

Cutaneou

s80

Labo

ratory

(smear

microscop

y)Yes

Firooz

etal.,2006

Razavi,Iran

Multic

enterS

tudy;

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

8/2004

-/2005

12-60,27.0

Male4

4.5%

Female5

5.5%

Cutaneou

s119

Labo

ratory

(smearo

rcultu

re)

Yes

Khatamietal.,2013

Kashan,Iran

Rand

omized

Con

trolledClinical

Trial

9/200–

4/2010

12-60,28.8

Male4

7%Female5

3%Cu

taneou

s83

Labo

ratory

(smearo

rcultu

re)

Yes

Llanos

Cuentasetal.,

2010

Cusco,Peru

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

8/2004

–6/2005

18-59

Male9

6%Female4

%Mucosal

48Labo

ratory

(microscop

y,PC

Ror

invitro

cultu

re)

Yes

Machado

etal.,2007

Bahia,Brazil

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

NR

18-65

Male8

3%Female17%

Mucosal

23

Labo

ratory

(Intradermal

skin

test,

parasiteisolatio

nby

cultu

re,and

/or

histo

pathological)

Yes

Meymandi

etal.,2

011Ke

rman,Iran

Com

parativ

eStudy;

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

11/2007-8/200

97-60

Male4

6.6%

Female5

3.4%

Cutaneou

s191

Labo

ratory

(smearo

rskin

biop

sy)

Yes

Mira

nda-Ve

raste

guiet

al.,2

005

Lima,Peru

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

2/2001

–8/2002

1-78

Male5

7.5%

Female4

2.5%

Cutaneou

s40

Labo

ratory

(aspira

tion,

smear,biop

sy,culture,

and/or

PCR)

Yes

4 Dermatology Research and Practice

Table1:Con

tinued.

Stud

ysource

Area,

Cou

ntry

Stud

ydesign

Period

ofstud

yAge

rang

e,mean(years)

Gen

der

Clin

ical

form

Patie

nts

enrolle

dLe

ishm

aniasisd

iagn

osis

Statistic

s

Mira

nda-Ve

raste

guiet

al.,2

009

Limaa

ndCu

sco,Peru

Com

parativ

eStudy;

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

12/200

5-6/2006

4-52

Male7

7.5%

Female2

2.5%

Cutaneou

s80

Labo

ratory

(smear

microscop

y,cultu

reor

PCR)

Yes

Nascimento

etal.,

2010

Minas

Gerais,

Brazil

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

10/200

4–10/200

618-59,26.4

Male6

3.6%

Female3

6.4%

Cutaneou

s44

Labo

ratory

(microscop

yidentifi

catio

nin

biop

sied

tissue)

Yes

Nilforou

shzadehet

al.,2

007

Isfahan,Iran

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

NR

7-70

Male6

7.7%

Female3

2.3%

Cutaneou

s90

Labo

ratory

(smear

microscop

y)Yes

Nilforou

shzadehet

al.,2

008

Tehran,Iran

Com

parativ

eStudy;

Rand

omized

Con

trolledTrial

NR

7-70

Male7

1.0%

Female2

9.0%

Cutaneou

s124

Labo

ratory

(smear

microscop

y)Yes

VanTh

ieletal.,2010

Northern

Afghanista

n,ClinicalTrial

6/2005-11/2

005

NR

Dutch

Troo

psCu

taneou

s163

Labo

ratory

(smear

microscop

y,cultu

re,and

PCR)

Yes

NR,

notreported;PC

R,po

lymerasec

hain

reactio

n.

Dermatology Research and Practice 5

Table2:Clinic,therapeutic,and

epidem

iologicalcharacteristicso

fclin

icaltrialsinclu

dedin

thes

tudy.

Stud

ysource

Leish

man

iaspecies

Treatm

ent

Patie

ntsa

tthee

ndPrevious

treatm

ent

Clin

icallyhe

aled

Therap

yfailed

Relapseo

rRe

curren

ce

Alm

eida

etal.,2005

L.braziliensis

G1(MA+GM-C

SF)

5Yes

100%

(before120

days

AS)

Follo

w-up:12

mon

thsA

H0%

(12mon

thsA

H)

0%(12mon

thsA

H)

Arevaloetal.,2007

Leish

man

iaspp.

G1(IM

)6

No

0%Fo

llow-up:3mon

thsA

S67%(20days

AS)

33%(3

mon

thsA

S)

G2(M

A)

7No

57%(3

mon

thsA

S)Fo

llow-up:3mon

thsA

S43%(3

mon

thsA

S)0%

(3mon

thsA

S)

G3(M

A+IM

)7

No

100%

(3mon

thsA

S)Fo

llow-up:3mon

thsA

S0%

(3mon

thsA

S)0%

(3mon

thsA

S)

Brito

etal.,2017

L.braziliensis

(62%

ofcases)

G1(MA+PE

)82

NR

45%(6

mon

thsA

E)55%(6

mon

thsA

E)NR

G2(M

A+placebo)

8243%(6

mon

thsA

E)57%(6

mon

thsA

E)NR

El-Sayed

&Anw

ar,2010

NR

G1(ilSSG)

10(12lesio

ns)

No

50%/58.3%

(12we

eksA

S;patie

nts/lesio

ns)

Follo

w-up:6mon

thsA

E

50%/41.7

%(12we

eksA

S;patie

nts/lesio

ns)

NR

G2(il

SSG+im

SSG)

10(15lesio

ns)

No

90%/93.3%

(12we

eksA

S;patie

nts/lesio

ns)

Follo

w-up:6mon

thsA

E

10%/6.7%(12we

eksA

S;patie

nts/lesio

ns)

NR

G3(il

SSG+KE

)10

(13lesio

ns)

No

90%/92.3%

(12we

eksA

S;patie

nts/lesio

ns)

Follo

w-up:6mon

thsA

E

10%/7.7%

(12we

eksA

S;patie

nts/lesio

ns)

NR

Farajza

dehetal.,2

015

NR

G1(Terbinafine

+cryotherapy)

40No(w

ithin

thep

ast9

0days)

37.5%complete(28

days

AS)

10partialcure#

15(28days

AS)

NR

G2(M

A+

cryotherapy)

40No

52.5%(21d

aysA

S)7partialcure#

12(21d

aysA

S)NR

Firooz

etal.,2006∗∗

L.tro

pica

G1(MA+IM

)42

No

18.6%(4

weeksA

S)44

.1%(8

weeksA

S)50.8%(20we

eksA

S)Fo

llow-up:16

weeksA

E

49.2%(20we

eksA

S)3.1%

(16we

eksA

S)

G2(M

A+placebo)

47No

30.0%(4

weeksA

S)48.3%(8

weeksA

S)53.3%(20we

eksA

S)Fo

llow-up:16

weeksA

E

46.7%(20we

eksA

S)8.1%

(16we

eksA

S)

Khatamietal.,2013

L.major

G1(ilMA)

23(40

lesio

ns)

No

12.5%(6

weeksA

S)lesio

ns40

.0%(10we

eksA

S)lesio

nsFo

llow-up:5mon

thsA

E

65.0%(6

weeksA

S)42.5%(10we

eksA

S)0%

(5mon

thsA

E)

G2(il

MA+

non-silverP

D)

21(46

lesio

ns)

No

6.5%

(6we

eksA

S)lesio

ns42.2%(10we

eksA

S)lesio

nsFo

llow-up:5mon

thsA

E

80.4%(6

weeksA

S)55.6%(10we

eksA

S)0%

(5mon

thsA

E)

G3(il

MA+silver

PD)

29(55

lesio

ns)

No

12.7(6

weeksA

S)lesio

ns36.4(10we

eksA

S)lesio

nsFo

llow-up:5mon

thsA

E

74.6%(6

weeksA

S)49.1%

(10we

eksA

S)3.4%

(5mon

thsA

E)

6 Dermatology Research and Practice

Table2:Con

tinued.

Stud

ysource

Leish

man

iaspecies

Treatm

ent

Patie

ntsa

tthee

ndPrevious

treatm

ent

Clin

icallyhe

aled

Therap

yfailed

Relapseo

rRe

curren

ce

Llanos

Cuentasetal.,2010

L.braziliensis

G1(SSG+placebo)

12No(w

ithin

thep

ast3

0days);

22.0%had

received

previously

50%(84days

AS)

100%

(336

days

AS)

Follo

w-up:336days

AS

25%(168

days

AS)

0%(336

days

AS)

8%(336

days

AS)

G2(SSG

+(LEISH

-F1

+MPL

-SE))

LEISH-F1

5𝜇g=11

59%(84days

AS)

94%(336

days

AS)

Follo

w-up:336days

AS

13%(168

days

AS)

6%(336

days

AS)

0%(336

days

AS)

LEISH-F1

10𝜇g=12

LEISH-F1

20𝜇g=11

Machado

etal.,2007

L.braziliensis

G1(MA+placebo)

12No∗

41.6%(90days

AS)

Follo

w-up:150days

AS

42%(150

days

AS)

0%(2

yearsA

E

G2(M

A+PE

)11

No∗

82%(90days

AS)

Follo

w-up:150days

AS

0%(150

days

AS)

0%(2

yearsA

E)

Meymandi

etal.,2

011

L.tro

pica

G1(C02laser)

80No

56.8%(2

weeksA

S)67.6%(6

weeksA

S)44

.4%(12we

eksA

S)93.7%(89/95

lesio

ns)

Follo

w-up:16

weeksA

S

NR

NR

G2(il

MA+

cryotherapy)

80No

15.8%(2

week

AS)

57.5%(6

week

AS)

38.2%(12we

ekAS)

78%(74/95)lesions)

Follo

w-up:16

weeksA

S

NR

NR

Mira

nda-Ve

raste

guietal.,

2005

L.peruvian

aL.braziliensis

G1(MA+IM

)18

(35lesions)

Yes

6%(20days

AE)

50%(1mon

thAE)

61%(2

mon

thsA

E)72%(3

mon

thsA

E)72%(6

mon

thsA

E)72%(12mon

thsA

E)Fo

llow-up:12

mon

thsA

E

27.8%(12mon

thsA

E)NR

G2(M

A+Ve

hicle)

20(40

lesio

ns)

Yes

5%(20days

AE)

15%(1mon

thAE)

25%(2

mon

thsA

E)35%(3

mon

thsA

E)50%(6

mon

thsA

E)75%(12mon

thsA

E)Fo

llow-up:12

mon

thsA

E

25%(12mon

thsA

E)NR

Dermatology Research and Practice 7Ta

ble2:Con

tinued.

Stud

ysource

Leish

man

iaspecies

Treatm

ent

Patie

ntsa

tthee

ndPrevious

treatm

ent

Clin

icallyhe

aled

Therap

yfailed

Relapseo

rRe

curren

ce

Mira

nda-Ve

raste

guietal.,

2009

L.peruvian

aL.

guyanensis

L.braziliensis

G1(SSG+vehicle

cream)

36No

17.5%

(20days

AS)

33%(1mon

thAS)

30%(2

mon

thsA

S)60

%(3

mon

thsA

S)63%(6

mon

thsA

S)58%

(9mon

thsA

S)53%(12mon

thsA

S)Fo

llow-up:12

mon

thsA

S

41.7%(12mon

thsA

S)NR

G2(SSG

+IM

)39

No

5%(20days

AS)

43%(1mon

thAS)

60%(2

mon

thsA

S)78%(3

mon

thsA

S)75%(6

mon

thsA

S)75%(9

mon

thsA

S)75%(12mon

thsA

S)Fo

llow-up:12

mon

thsA

S

23.1%

(12mon

thsA

S)NR

Nascimento

etal.,2010

Leish

man

iaspp.

G1(MA+(LEISH

-F1

+MPL

-SE))

LEISH-F1

5𝜇g=9

No

80%(84days

AS)

Follo

w-up:336days

AS

24%(84days

AS)

4%(84days

AS)

LEISH-F1

10𝜇g=8

LEISH-F1

20𝜇g=8

G2(M

A+M

PL-SE)

8No

50%(84days

AS)

Follo

w-up:336days

AS

50%(84days

AS)

NR

G3(M

A+S

aline)

8No

38%(84days

AS)

Follo

w-up:336days

AS

62%(84days

AS)

38%(84days

AS)

Nilforou

shzadehetal.,2

007

Leish

man

iaspp.

G1(ilMA+topical

honey)

33No

51.1%

(6we

eksA

S)Fo

llow-up:4mon

thsA

S48.9%

(6we

eksA

S)NR

G2(il

MA)

35No

71.1%

(6we

eksA

S)Fo

llow-up:4mon

thsA

S28.9%

(6we

eksA

S)NR

Nilforou

shzadehetal.,2

008

L.tro

pica

L.major

G1(MA60

mg/kg/day

+placebo)

43No

93%(12we

eksA

S)Fo

llow-up:12

weeksA

S7%

(12we

eksA

S)NR

G2(M

A30

mg/kg/day

+OM)

36No

89%

(12we

eksA

S)Fo

llow-up:12

weeksA

S11%

(12we

eksA

S)NR

G3(M

A30

mg/kg/day

+placebo)

45No

80%(12we

eksA

S)Fo

llow-up:12

weeksA

S20%(12we

eksA

S)NR

VanTh

ieletal.,2010

L.major

G1(ilSSG)

118No

55.1%

(6mon

thsA

E)Fo

llow-up:6mon

thsA

E20.3%(6

mon

thsA

E)15.3%(6

mon

thsA

E)

G2(il

SSG+

cryotherapy)

45No

66.7%(6

mon

thsA

E)Fo

llow-up:6mon

thsA

E13.3%(6

mon

thsA

E)11.1%

(6mon

thsA

E)

NR,

notreported;G1,Group

1;G2,Group

2;G3,Group

3.MA,m

eglumineantim

oniate;P

E,pentoxify

lline;G

M-C

SF,g

ranu

locyte

macroph

agecolony-stim

ulatingfactor;IM,imiquimod

;ilS

SG,intralesio

nals

odium

stibo

glucon

ate;

imSSG,intramuscularsodium

stibo

glucon

ate;KE,ketoconazole;ilM

A(in

tralesionalm

egluminea

ntim

oniate);no

n-silverP

D,non

-silvercontaining

polyesterd

ressing;silverP

D,silvercontaining

polyesterd

ressing;SSG,sod

ium

stibo

glucon

ate;

LEISH-F1,lyop

hilized

LEISH-F1p

rotein;M

PL-SE,

adjuvant;O

M,omeprazole.

AS:aft

erthes

tartof

treatment,AE:

after

thee

ndof

treatment,andAH:afte

rthe

healingof

thelesion.

∗Noprevious

treatmento

fmucosalleish

maniasis.Som

epatientsh

adprevious

cutaneou

sleishmaniasis,but

therea

reno

references

toprevious

treatmento

rnot.

∗∗Clinicalcure

rate,therapy

failu

re,and

relapseo

rrecurrencegivenby

Firooz

etal.,2006

,based

ontheinitia

lnum

bero

fpatientsa

llocatedin

each

grou

p.# Partia

lcureF

arajzadeh:decrease

inindu

ratio

nsiz

ebetwe

en25

and75%.

8 Dermatology Research and Practice

Table 3: Description of adverse effects of combinations for the treatment of tegumentary leishmaniasis.

Treatment Side effects Study source

MA + IM

Localized pruritus, erythema and edema (77%); arthralgia, myalgia, flu-likesymptoms (86%); and elevated liver enzyme levels (64%). Arevalo et al., 2007

Moderate pruritus and burning sensation (7.1%). Firooz et al., 2006

Edema (35%); itching (10%); burning (15%); pain (5%); erythema (55%). Miranda-Verastegui et al.,2005

MA + PE

Nausea (27.3%); arthralgias (9.1%); dizziness, abdominal pain, and diarrhea(9.1%). Machado et al., 2007

Vomiting (2.4%); Diarrhea (1.2%); Nausea (8.6%); Headache (11%); Asthenia(3.7%); Anorexia (3.7%); Epigastralgia (3.7%); Pain (2.4%); Dizziness (2.4%);Fever (7.4%); Arthralgia (8.6%); Myalgia (13.5%)

Brito et al., 2017

MA + cryotherapy No adverse effects were observed Farajzadeh et al., 2015

MA + (LEISH-F1 +MPL-SE)

Local: induration (44.4 – 77.8%); erythema (11.1 – 100%); tenderness(33.3-44.4%).Systemic: headache (0-22.2%); pyrexia (0-22.2%).MA-related AEs (22.2 – 88.9%).

Nascimento et al., 2010

MA + GM-CSF No adverse effects were observed Almeida et al., 2005MA + OM NR Nilforoushzadeh et al., 2008il MA + silver PD Itching and burning (35.3%); edema (33.3%). Khatami et al., 2013il MA + topical honey Dermatitis to honey (3%). Nilforoushzadeh et al., 2007

il MA + cryotherapy Hyper pigmentation+trivial scar (18.7%); atrophic scar (7.5%); hypopigmentation+trivial scar (18.8%). Meymandi et al., 2011

SSG + (LEISH-F1 +MPL-SE)

Local: induration (41.7 – 75.0%); erythema (50.0 – 100.0%); tenderness (66.7 –91.7%).Systemic: anorexia (0 – 8.3%); fatigue (0 – 8.3%); malaise (25.0%); myalgia (0– 8.3%); headache (33.3 – 50.0%).SSG-related (100%).

Llanos Cuentas et al., 2010

SSG + IM Swelling (30%); itching (25%); pain (12.5%); erythema (32.5%). Miranda-Verastegui et al.,2009

il SSG + im SSG im SSG: Pain at the injection site (100%).il SSG: Pain and swelling at the intralesional injection site (100%). El-Sayed & Anwar, 2010

il SSG + KE KE: No.il SSG: Pain and swelling at the intralesional injection site (100%). El-Sayed & Anwar, 2010

il SSG + cryotherapy Secondary infection (31%); lymphatic involvement (48.8%); pain at theinjection site VanThiel et al., 2010

NR, not reported; G1, Group 1; G2, Group 2; G3, Group 3. MA, meglumine antimoniate; PE, pentoxifylline; GM-CSF, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IM, imiquimod; il SSG, intralesional sodium stibugluconate; im SSG, intramuscular sodium stibugluconate; KE, ketoconazole; il MA(intralesional meglumine antimoniate); non-silver PD, non-silver containing polyester dressing; silver PD, silver containing polyester dressing; SSG, sodiumstibugluconate; LEISH-F1, lyophilized LEISH-F1 protein; MPL-SE, adjuvant; OM, omeprazole; AEs, adverse events.

polyester dressing; silver-containing polyester dressing;lyophilized LEISH-F1 protein; cryotherapy, topical honey,and omeprazole.

Among the patients involved in the studies, 92.0%(1199/1302) ended the treatment, of which 48.0% (575/1199)underwent a combination treatment (antimonial pentavalentplus other treatment) and the remaining 52.0% (624/1199)were treated only with pentavalent antimonials or other treat-ment modalities (Table 2). Most of them had not undergoneprevious treatments.

The combination of drugs revealed high rates of clinicalcure among the groups treated with drug combination.Two papers reported a cure rate of 100% in these groups(Almeida et al. 2005 [19]; Arevalo et al. 2007 [20]), while8 authors reported 70-94% cure in the groups treated with

combinations (El-Sayed and Anwar 2010 [21]; Llanos Cuentaset al. 2010 [22]; Machado et al. 2007 [15]; Meymand et al. 2011[10]; Miranda-Verastegui et al. 2005 [23]; Miranda-Verasteguiet al. 2009 [24]; Nascimento et al. 2010 [25]; Nilforoushzadehet al. 2008 [26]). The other authors reported cure rates below70% and ranged from 36.4% to 66.7%. The lowest curerate was (36.4%) in the combination of IL-MA+ silver PD(Khatami et al. 2013 [27]) (Table 2).

Among the combinations, those with 100% of curerate were meglumine antimoniate (MA) plus granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Almeidaet al. 2010) and meglumine antimoniate plus imiquimod(Arevalo et al. 2007). The other combinations that resultedin 70-94% of cure were the combinations of sodium sti-bogluconate (SSG) plus LEISH-F1 + MPL-SE (94%) (Llanos

Dermatology Research and Practice 9

Table4:Con

clusio

non

combinatio

ntre

atmentasa

newtre

atmento

ftegum

entary

leish

maniasis

inthes

ystematicreview

.

Treatm

ent

Dose

Routeo

fAdm

inistration/Time

Time

Efficacy

Safety

Practic

e/clinical

implications

Stud

ysource

MA+IM

IM:L

esion≤3c

m:1

dose

of7.5

%cream.

Lesio

n>3cm

:2do

seso

f7.5

%cream.

Each

dose

=125mg.

IM:top

ical-d

aily

20days

Efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gInvestigatio

nal

Arevaloetal.,2

007

MA:20mg/kg/day.

MA:IV-d

aily

IM:5%cream.

IM:top

ical-3

times

perd

ayIM

:28days

Likely

efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gInvestigatio

nal

Firooz

etal.,2006

MA:20m

gSb5+/kg/day.

MA:IM

daily

MA:14days

IM:5%cream.

IM:Top

ical-d

aily.

IM:20days.

Efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

out

specialized

mon

itorin

gClinicallyuseful

Mira

nda-

Veraste

gui

etal.,2005

MA:20m

g/kg/day.

MA:IM

daily

inchild

ren,

andIV

infusio

nin

older

subjects.

MA:20days.

MA+PE

MA:20m

g5+/kg/day

MA:daily

MA:30days

Efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gClinicallyuseful

Machado

etal.,2

007

PE:400

mg

PE:oral–

3tim

esdaily

PE:30days

MA:20m

gsbv/K

g/day

MA:IV-

daily

MA:20days

Not

efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gNot

useful

Brito

etal.,2017

PE:400

mPE

:oral-3tim

esdaily

PE:20days

MA+

cryotherapy

Cryotherapy:fre

ezetim

e(10-25

s)

Cryotherapy:on

thelesion

until

1-2mm

ofsurrou

ndingno

rmaltissue

appeared

frozen

Everytwowe

eks

Likely

efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

out

specialized

mon

itorin

gPo

ssiblyuseful

Farajza

dehetal.,

2015

MA:15mg/kg/day

Intram

uscular

Everydayfor3

weeks

MA+

(LEISH

-F1+

MPL

-SE)

LEISH-F1:5,10

or20𝜇g+

25𝜇gMPL

-SE.

LEISH-F1:SU

B–3tim

es.

LEISH-F1:Onday0,28

and56.

Likely

efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gPo

ssiblyuseful

Nascimento

etal.,

2010

MA:10mg/

Sb5+kg/day.

MA:IV–10-daysc

ycles

follo

wedby

11days

ofrest.

MA:Th

efirst10-days

cycleo

nDay

0.Ad

ditio

nalcycleso

ndays

21,42,and63

MA+GM-C

SFGM-C

SF:1-2

mL(10

𝜇g/mL).

GM-C

SF:top

ical–3tim

esperw

eek.

GM-C

SF:3

weeks

Efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

out

specialized

mon

itorin

gInvestigatio

nal

Alm

eida

etal.,2005

MA:20mgSb5+/kg/day.

MA:IV–daily.

MA:20days

10 Dermatology Research and Practice

Table4:Con

tinued.

Treatm

ent

Dose

Routeo

fAdm

inistration/Time

Time

Efficacy

Safety

Practic

e/clinical

implications

Stud

ysource

MA+OM

MA:30m

g/kg/day

MA:IM-d

aily

MA:3

weeks

Likely

efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gClinicallyuseful

Nilforou

shzadehet

al.,2008

OM:40m

gOM:oral-

daily

OM:3

weeks

ilMA+silver

PD

MA:il

MA:Intraderm

allyin

each

onec

entim

eter

square

ofa

lesio

nun

tilblanching

occurred

intralesional,on

cewe

ekly.

42days

Not

efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gInvestigatio

nal

Khatamietal.,2013

Silver

PD:onthelesion

Silver

dressin

g:topical–

once

daily

ilMA+topical

honey

MA:il

MA:ileno

ughto

blanch

thelesionand1m

mrim

ofthes

urroun

ding

norm

alskin,oncew

eekly.

Untilcompleteh

ealin

gor

form

axim

um6we

eksNot

efficaciou

sInsufficientevidence

Investigatio

nal

Nilforou

shzadehet

al.,2007

Hon

ey:soakedgauze

Hon

ey:top

ical–twiced

aily

ilMA+

cryotherapy

Cryotherapy:fre

ezetim

e(10-2

5s)

Cryotherapy:on

thelesion

until

2-3m

mhaloform

sarou

nd,w

eekly,before

ILMA.

Untilcompletec

ureo

rforu

pto

12we

eks

Likely

efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

out

specialized

mon

itorin

gPo

ssiblyuseful

Meymandi

etal.,

2011

MA:(0.5–

2ml)

MA:intraderm

ally,

all

directions,untilthelesion

hadcompletely

blanched,

weekly.

SSG+

(LEISH

-F1+

MPL

-SE)

LEISH-F

1:5,10

or20𝜇g+

25𝜇gMPL

-SE.

LEISH-F1:SU

B–3tim

es.

LEISH-F1:Onday0,28

and56.

Efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gInvestigatio

nal

Llanos

Cuentase

tal.,2010

SSG:20m

g/kg/day

SSG:IV–daily

SSG:day

0to

27

SSG+IM

IM:5%cream.

IM:Top

ical-3

times

per

week.

IM:20days

Efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

out

specialized

mon

itorin

gClinicallyuseful

Mira

nda-

Veraste

gui

etal.,2009

SSG:20mg/kg/day

SSG:IV–daily.

SSG:20days

ilSSG+im

SSG

ilSSG(100

mg/mL),the

dose

varie

dbetween0.3-3.0

mL.Maxim

umdo

se20mg/Kg

/day.

il:Infiltrated

inmultip

lesites

until

complete

blanchinganda1-m

mwide

ringof

thes

urroun

ding

norm

alskin.

ilSSGon

days

1,3,5in

ones

essio

n-u

pto

3cycles.

Efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gPo

ssiblyuseful

El-Sayed

&Anw

ar,

2010

imSSG(a

partof

thed

ose

20mg/Kg/dayalreadygiven

provided

toIL

SSGin

the

samed

ays).

im:one

injectionon

days

1,3,5-u

pto

3cycles

with

4we

eksinterval.

Dermatology Research and Practice 11

Table4:Con

tinued.

Treatm

ent

Dose

Routeo

fAdm

inistration/Time

Time

Efficacy

Safety

Practic

e/clinical

implications

Stud

ysource

ilSSG+KE

ilSSG(100

mg/mL),the

dose

varie

dbetween0.3-3.0

mL,maxim

umdo

se20mg/Kg

/day.

il:Infiltrated

inmultip

lesites

until

complete

blanchinganda1-m

mwide

ringof

thes

urroun

ding

norm

alskin.

il:on

days

1,3,5in

one

session-u

pto

3cycles.

Efficaciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

specialized

mon

itorin

gPo

ssiblyuseful

El-Sayed

&Anw

ar,

2010

KE:200

mg.

KE:3

times

daily.

KE:4

weeks.

ilSSG+

cryotherapy

ilSSG:1-2ml.

ilSSG:intomarginof

each

lesio

n,allaroun

d,un

tilblanchingwith

cryotherapy

precedingthefi

rst

injection.

ilSSG:3

injections

SSG

with

intervalso

f1-3

days.Effi

caciou

sAc

ceptableris

kwith

out

specialized

mon

itorin

gClinicallyuseful

vanTh

ieletal.,2010

Cryotherapy:localw

itha

doub

lefre

eze-thaw

cycle.

20second

sfor

freezing

cyclea

ndthaw

ingtim

ebetweencycles

of45-90

second

s.

Cryotherapy:tre

atment

was

repeated

until

clinicalim

provem

ent

(range

1-163

days).

MA,m

eglumineantim

oniate;P

E,pentoxify

lline;G

M-C

SF,g

ranu

locyte

macroph

agecolony-stim

ulatingfactor;IM,imiquimod

;ilS

SG,intralesio

nals

odium

stibo

glucon

ate;

imSSG,intramuscularsodium

stibo

glucon

ate;KE,

ketoconazole;ilM

A(in

tralesionalm

eglumineantim

oniate);no

nsilver

PD,n

onsilverc

ontainingpo

lyesterd

ressing;silverP

D,silver

containing

polyesterd

ressing;SSG,sod

ium

stibo

glucon

ate;

LEISH-F1,lyop

hilized

LEISH-F1p

rotein;M

PL-SE,

adjuvant;O

M,omeprazole;IV,

intravenou

s;IM

,intramuscular;SU

B,subcutaneously.

12 Dermatology Research and Practice

Articles identified through databasesearching(n= 4,725)

Publications recovered in the referencesof the selected articles

(n = 0)

Records identified a�er applying filters(Abstract; Humans; English; Clinical

(n= 363)Trial)

Records a�er removal of duplicates(n= 311)

Articles assessed in full text for

(n= 90)eligibility

Full text articles included in the

(n=16)systematic review

Full text articles excluded for not

(n= 74)meeting the goals of the study

Excluded articles (n= 221)- Visceral leishmaniasis/Kala-azar (n= 91)

- Did notmeet the goals of the study (n= 90)(n= 20)

(n= 9)- No human subjects

- Case report ( n= 1)

- Related the Leishmania species to the response totreatment (n= 1)

- Review articles (n= 9)-- In vitro studies

Iden

tifica

tion

Scre

enin

gEl

igib

ility

Inclu

sion

Figure 1: Flow diagram of study selection for the systematic review.

Dermatology Research and Practice 13

Cuentas et al. 2010); intralesional sodium stibogluconate plusketoconazole (90%) (El-Sayed and Anwar 2010); meglumineantimoniate plus omeprazole (89%) (Nilforoushzadeh et al.2008); MA and pentoxifylline (82%) (Machado et al. 2007);meglumine antimoniate plus LEISH-F1 + MPL-SE (80%)(Nascimento et al. 2010); intralesional sodium stibogluconateplus cryotherapy (78%) (Meymand et al. 2011); sodiumstibogluconate plus imiquimod (75%) (Miranda-Verasteguiet al., 2009); and meglumine antimoniate plus imiquimod(72%) (Miranda-Verastegui et al. 2005). It is important tonote that most combinations that showed high cure rates(70-100%)were combinations of pentavalent antimonial withsome immunomodulators.

Relapse or recurrence, when reported, was higher in thegroups treated with pentavalent antimonial alone and variedfrom 0 to 38% (Llanos Cuentas et al., 2010; Nascimentoet al., 2010 [22, 25]). For the associated groups, only fourassociations presented relapse or recurrence, and these ratesranged from0 to 11.1% (Firooz et al. 2006;Van-Thiel et al. 2010[28, 29]) (Table 2).

No serious adverse effects were observed in patientstreated with the drugs combination. For the combination ofimiquimod andmeglumine antimoniate, adverse effects werelocally limited, being the most reported pruritus/itching,erythema, and edema. For the combination of imiquimodwith sodium stibogluconate, the same was observed. OnlyMiranda-Verastegui et al. (2005) [23] reported elevated liverenzyme levels.

In relation to granulocyte macrophage-stimulating fac-tor, there were no reports of side effects. With lyophilizedLEISH-F1 protein in association to meglumine antimoniate,the observed side effects were induration, erythema, andtenderness; in combination with sodium stibogluconate, thepresence of induration, erythema, and tenderness sites wasreported, in addition to headache pyrexia and systemicmalaise.The common adverse effects of the use ofmeglumineantimoniate and sodium stibogluconate were also observed.

To the combination of meglumine antimoniate and pen-toxifylline, the common adverse effects, described in twostudies, were nausea, arthralgia, dizziness, pain, and diarrhea.

In the use of intralesional sodium stibogluconate, aloneor in association with other medicinal products, secondaryinfection, pain and swelling at injection site, and lymphaticinvolvement were observed. The pentavalent intralesionalantimonials also showed adverse effects related to the appli-cation site, such as pain, pruritus/itching, and edema.

Intralesional sodium stibogluconate, when associatedwith cryotherapy, resulted in secondary infection and lym-phatic involvement, in addition to the inherent symptomsof intralesional application of stibogluconate already men-tioned. Meglumine antimoniate combined with silver PDpresented only itching, burning, and edema, in contrast towhen combined with topical honey, in which only dermatitis,caused by honey, was reported. Cryotherapy combined withmeglumine antimoniate had only local adverse effects suchas hyperpigmentation plus trivial scar, atrophic scar, andhypopigmentation plus trivial scar (Table 3).

Each of the combinations was classified according totheir efficacy (efficacious/likely efficacious/not efficacious)

and the clinical implications (investigational/clinically use-ful/possibly useful) [30].

In this context, imiquimod associated with meglumineantimoniate (Miranda-Verastegui et al. 2005 [23]) and sti-bogluconate (Miranda-Verastegui et al. 2009 [24]) andcryotherapy-associated stibogluconate (Van-Thiel et al. 2010[29]) were classified as clinically useful and with acceptablerisk without specialized monitoring. Themeglumine antimo-niate associated with pentoxifylline (Machado et al. 2007)were classified as clinically useful and with acceptable riskwith specialized monitoring (Machado et al. 2007 [15]). Onthe other hand the combination of meglumine antimoniateassociated with pentoxifylline performed by Brito et al. 2017[31] to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmaniabraziliensis was classified as not efficacious and not useful.Meglumine antimoniate associated with omeprazole (Nil-foroushzadeh et al. 2008 [26]) was classified as clinicallyuseful and with acceptable risk with specialized monitoring.

Some combinations have been classified as possibly usefulwith acceptable risks without specialized monitoring, such ascryotherapy combined with meglumine antimoniate (Fara-jzadeh et al. 2015 [32]) and the intralesional meglumineantimoniate with cryotherapy (Meymandi et al. 2011 [10]).The combination LEISH-F1 + MPL-SE plus meglumine anti-moniate (Nascimento et al. 2010 [25]) and sodium stiboglu-conate with ketoconazole (EL-Sayed and Anwar 2010 [21])was classified as possibly useful and with an acceptable riskwith specialized monitoring.

GM-CSF plus meglumine antimoniate (Almeida etal. 2005 [19]) was still classified as investigational andwith acceptable risk without specialized monitoring, whileother combinations were classified as investigational, butwith acceptable risk with specialized monitoring, such as:imiquimod plus meglumine antimoniate (Arevalo et al.,2007 [20]), Leish-F1+ MPLE-SE plus sodium stibogluconate(Llanos Cuentas et al. 2010 [22]), meglumine antimoniatecombined with silver PD (Khatami et al. 2013 [27]), andimiquimod plus meglumine antimoniate (Firooz et al. 2006[28]). The evidence provided by the study with the combi-nation of intralesional meglumine antimoniate and topicalhoney was insufficient to classify this combination in relationto safety (Table 4).

Regarding effectiveness, only three combinations wereclassified as noneffective: intralesional meglumine antimo-niate associated with topical honey performed by Nil-foroushzadeh et al. (2007) [33], intralesional meglumineantimoniate associated with silver PD tested by Khatami et al.(2013) [27], and pentoxifylline plus meglumine antimoniateperformed by Brito et al. (2017).The other combinations wereclassified as “efficacious” or “likely efficacious”.

4. Discussion

In this review, we saw that the majority of the combinationsresulted in an elevated cure rate. Relapse or recurrence,when reported, were higher in the groups treated with theisolated drugs than in the ones treated with the drugs com-bination. These findings indicate that the combinations with

14 Dermatology Research and Practice

pentavalent antimonials were more efficacious to preventrelapse or recurrence. Several authors have demonstrated thatthe combination of some drugs with pentavalent antimonialshowed a higher percentage of cure.

4.1. Pentavalent Antimonials. Pentavalent antimonials areconsidered the first line drugs to treat CL, but they havecollateral effects and, in some cases, low cure rate. Accordingto a systematic review by Tuon et al. (2008) [34], meg-lumine antimoniate (MA), in the recommended dose (20mg/kg/day), presents an average cure of 76.5%. However,among the studies evaluated by Tuon et al. (2008) [34] andother studies, meglumine antimoniate (20 mg/kg/day) curerates are quite variable: 40.4% [7, 16], 56.9% [35], 69.4% [7],79% [36], 84% [5], 85% [37], and 100% [38, 39].

For sodium stibogluconate (SSG), the cure rate shown byTuon et al. (2008) [34] was of 75.5% in different dosages, witha maximum dose of 20 mg/kg/day. However, the efficacy forthis pentavalent antimonial is also variable, being reportedrates of 53% [24], 56% [40], 70% [41], and 100% [22, 42].

It is known that the use of systemic meglumine antimo-niate can be lead to serious adverse effects, so the applicationin the lesion site showed to be an efficacious and more securealternative to treat CL. Some authors have demonstrated thatthe intralesional MA is as effective as the systemic MA andhad few adverse effects [43–45]. It is important to note that,unlike in the articles included in this study, Vasconcellos et al.(2014) [46] reported that one patient presented eczema afterthe treatment with intralesional meglumine antimoniate.After use of oral dexchlorpheniramine, eczema and ulcerreceded. Thus, the administration of intralesional MA mustbe carefully conducted, especially due to the possibility ofoccurring hypersensitivity.

For the SSG, the intralesional application has also showngood results [47, 48]. The application twice a week is welltolerated and the lesions healed faster than only once a week[49].

4.2. GranulocyteMacrophageColony-Stimulating Factor (GM-CSF). The granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating fac-tor (GM-CSF) acts in the recruitment of monocytes andneutrophils. It is produced by a wide range of cellssuch as macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, T cells,eosinophils, fibroblasts and endothelial cells. It is alsobelieved that it promotes the differentiation of the macro-phages to a proinflammatory phenotype [50].

In view of its role in the recruitment of different types ofcells, GM-CSF has been investigated for the CL treatment. Intheir study, Almeida et al. (2005) [19] evaluated the topical useof GM-CSF (10 𝜇g/mL) in combination with the meglumineantimoniate (20 mg/kg/day) and showed that 60% of thepatients were clinically healed 50 days after the treatmentstart, and the remaining 40% were cured 120 days after thebeginning of the treatment. Similar results were found bySantos et al. (2004) [51], when they use this combination.On the other hand, among the patients treated only withmeglumine antimoniate, just 20% were clinically healed at 45days after the start of treatment, and 100%of the patients werecured after 256 days.

In a previous study, Almeida et al. (1999) [52] showedthat clinical cure in patients treated with the combination ofpentavalent antimonial and GM-CSF was faster than in thecontrol group that was treated with pentavalent antimonialalone. Possibly the factor that contributed for the quickcure associated by GM-CSF was the modulation of theimmunologic balance, by inducing differentiation for theTh1 subtype [52–54] and activation of macrophages to killLeishmania [55].

GM-CSF combined with pentavalent antimonial can bean alternative to treat CL, since the risk inherent to thiscombination is acceptable and its use deserves to be greatlyinvestigated.

4.3. Imiquimod. Imiquimod is an immunomodulator thatwas first approved to treat genital and perianal warts and thento treat actinic keratosis.

Imiquimod stimulates the immune system in differentways. It is believed that imiquimod is an agonist of thetool like receptors 7 and 8, so the stimulation of thesereceptors leads to the synthesis of different inflammatorymediators, such as INF-𝛼, TNF-𝛼, interleukins 1, 6, 8, 10 and12, granulocyte colony -stimulating factor and granulocytemacrophage colony-stimulating factor [56–58]. In addition,the use of imiquimod also indirectly contributes to theimmune response acquired, through the induction of Th1type cytokines, such as INF-Υ [58, 59].The induction of INF-Υ an IL-12 production induces toTh1 differentiation and it isimportant in the control of CL.

Imiquimod has been investigated in the treatment of CLand its efficacy is controversial. Arevalo et al. (2007) [20]and Seeberger et al. (2003) [60] showed no efficacy in theuse of imiquimod alone. In combination with pentavalentantimonials, imiquimod can be an adjuvant; moreover, thesuccess in treatment with imiquimod is directly related tothe concentration used. Only at the concentration of 7.5%imiquimod combined with meglumine antimoniate appearsto be more effective than the antimonate alone [20]. Authorsthat administered imiquimod at 5% in combination withmeglumine antimoniate observed that the efficacy was sim-ilar to that of patients treated with meglumine antimoniatealone [23, 28].

However, when Miranda-Verastegui et al. (2009) [24]used imiquimod 5% combined with sodium stibogluconate,the combination was more effective than sodium stiboglu-conate alone.

Meymandi et al. (2011) [61] showed the combinationof intralesional meglumine antimoniate and imiquimod asbeneficial its resulted in a decrease in parasitic load, anincrease in lymphocyte numbers, and a decrease in histiocyteaggregation in the lesion site. In addition, they observed thatimiquimod alone was also ineffective.

Imiquimod appears to be a good adjuvant for pentavalentantimonial when used in the appropriate concentration. Therisk involved in its use is acceptable. More evidence is neededto strengthen its application in clinical practice.

4.4. Silver-Containing Polyester Dressing. The silver-contain-ing polyester dressing (silver PD) is composed of hydropho-bic polyamide netting with silver-coated fibers. Silver PD

Dermatology Research and Practice 15

differs from each other by the way silver is incorporated andhow it is liberated in the lesion. It is known that silver hasantimicrobial activity in solutions, but it does not differentiateat pathogens from the other cells, such as fibroblast andkeratinocytes [62, 63].

Clinical trials using silver PD to treat CL are scarce. Inthis review, only one study used silver PD with this aim. Noefficacy in silver PD was shown, not even combined withintralesional meglumine in the treatment of CL [27]. In thisstudy, silver PD Atrauman Ag� by Hartmann was used.

Asmentioned before, silver can cause the death of humancells [63]. However, according to the manufacturer of theAtrauman Ag�, a higher concentration of silver is needed tolead to the death of human cells and, specifically in the caseof Atrauman Ag�, the release of silver is small. Moreover thisdressing released silver only when in contact with bacteriaand no negative influence of the silver ions was exercised inhuman cells [64]. Since amastigote forms are phagocytosedby macrophages, they remaining and multiplying. The silverreleased by the dressing, for being in small quantities, maynot be able to reach the amastigotes phagocytosed.

There are some inherent characteristics of polyester dress-ing that influence in their activity, such as their capacity in therelease of silver [65]. Besides that, the compounds binding tosilver can contribute to this activity.

The use of silver PD isolated or in combination withpentavalent antimonial needs to be further investigated dueto the scarcity of studies that used silver PD to treat CL andthe several factors that can influence its efficacy.

4.5. LEISH-F1+MPL-SE. LEISH-F1+MPL-SE was the firstcandidate vaccine for entry in clinical trials. It was composedby recombinant fusion protein Leish-111f and an adjuvantin an oil-water emulsion (monophosphoryl lipid A - MPL).MPL is a TLR4 agonist, safely used in other vaccines, such ashepatitis [66].

Authors demonstrated that LEISH-F1+MPL-SE was safe,immunogenic, and effective in inducing the production ofIgG antibodies, INF-Υ, and other cytokines in humans andmice [67–69].

In the two articles included in this review, LEISH-F1+MPL-SE was tested in combination with SSG or meglu-mine antimoniate in the treatment of CL. One of these LlanosCuentas et al. (2010) [22] observed similar clinically curein both groups; however in addition, relapse or recurrencedid not occur in the combination groups. The stimulation ofthe immune response was greater in the LEISH-F1+MPL-SEgroup than in the SSG group, a fact that may have contributedto the absence of recurrences.

Nascimento et al. (2010) [25], on the other hand, observeda greater clinical cure rate (80%) in the group treated with thecombination of LEISH-F1+MPL-SE and meglumine antimo-niate than in the groups treated with meglumine antimoniatealone (38%) or the adjuvant MPL-SE alone (50%).

LEISH-F1+MPL-SE in combination with pentavalentantimonials can be useful to treat CL, mainly because thiscombination appears to decrease recurrences observed with

pentavalent antimony alone. The risks related to its use areacceptable therefore its use should be better explored.

4.6. Topical Honey. Honey was used, many years ago to treatseveral types of lesions, but there is no consensus on itseffectiveness in lesion healing. In relation to CL, there are fewdata on the use of honey for its treatment.

It is well established that honey has an antimicrobialaction, which can act on tissues, contributing to their repair[70], and also on the immune system, having both proinflam-matory and anti-inflammatory action [71].

FDA has already approved some honey-based productswith different clinical indications, but some authors remaincautious regarding its clinical use for lesion healing. Jull etal. (2013) [72], in a review about the use of topical honey inthe treatment of wounds, concluded that honeymay delay thetime of wound healing in some types of wounds, such as CLand deep burns, but it is good for moderate burns. Still, intheir opinion, more clinical studies are needed to guide theuse of honey in clinical practice in other types of wounds thanmoderate burns.

In the same line Saikaly and Khachemoune (2017) [73]concluded in their study that the use of honey seems to bebeneficial to wound healing in some types of lesions and thatnew technologies have contributed to the understanding ofthe action mechanisms of honey. However, more evidence isstill needed to elucidate precisely the results obtainedwith theuse of honey.

The combination of topical honey with IL-MA to treatCL was tested by Nilforoushzadeh et al. (2007) [33] and didnot show efficacy. In this study, gauze soaked in honey wasused, not beingmentioned the type of honey used. It is knownthat there are different types of honey of different constitutionand that, therefore, they may have different properties [71].The choice of dressing must also be taken into consideration,as one should choose the dressing most appropriate for thewound to be treated [70].

There are several factors related to honey that should betaken into account, such as honey type and composition, aswell as the best form of application, and it deserves to bebetter evaluated in order to be combined with pentavalentantimonials in the treatment of CL.

4.7. Omeprazole. Omeprazole is a drug used to treat pepticulcer disease, due to its interference with the stomach pH.Omeprazole acts by inhibiting the human gastric K+, H+-ATPase enzyme, resulting in the disruption of acid secretion[74].

In the intracellular environment, omeprazole accumu-lates in the lysosomes, in the same place that the amastigotesin the macrophages. Jiang et al. (2002) [75] showed thatomeprazole inhibits the K+, H+-ATPase enzyme located onthemembrane surface of Leishmania, and this drug had leish-manicidal activity against Leishmania donovani intracellularamastigotes in a dose-dependent manner.

In their study, Nilforoushzadeh et al. 2008 [26] reportedthat omeprazole (40 mg) plus intramuscular meglumineantimoniate (30 mg/kg/day) showed similar clinical cure

16 Dermatology Research and Practice

presented by meglumine antimoniate (60 mg/kg/day), beingit of 89% and 93%, respectively. Moreover, omeprazole(40 mg) plus intramuscular meglumine antimoniate (30mg/kg/day) showed greater clinical cure rate thanmeglumineantimoniate (30 mg/kg/day), being the cure rates of 89% and80%, respectively.

The combination omeprazole plus meglumine antimoni-ate was well tolerated and the authors reported no side effects,thus it may be a clinically useful alternative likely efficaciousfor CL treatment.

4.8. Cryotherapy. Cryotherapy is a therapeutic modality rec-ommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) forthe treatment of CL. According toWHO, it is a recommendedtreatment regimen for Old World CL, combined or not withintralesional antimonial [4].

Above all, some studies showed that the combinationof cryotherapy with intralesional pentavalent antimonial ismore effective than the antimonial alone [11, 76].

The three articles included in this review, conducted byVan-Thiel et al. (2010) [29], Meymandi et al. (2011) [10] andFarajzadeh et al. (2015) [32], presented a lower cure rate forthe combination of cryotherapy and intralesional sodiumstibogluconate or for the combination with meglumine anti-moniate.

Some variables should be taken into consideration for theperformance of cryotherapy, whichmay directly influence theefficacy of the treatment, such as the size of the lesion and thefrequency of the cryotherapy sessions. Papules smaller thanor equal to 1 cm, respondedmore quickly to cryotherapy thanlesions larger than 1 cm. According to Ranawaka et al. (2011)[77], for smaller papules the cure rate was 90.5% and for theones larger than 1 cm, it was 64.28%.

The frequency of sessions also seems to play an importantrole in the effectiveness of cryotherapy. When performedweekly, cure rates were high (equal or greater than 90%),either alone or in combination with pentavalent antimonials[8, 77]. Application at longer time intervals may result inlower cure rates. Soto et al. (2013) [78] performed only twosessions of cryotherapy at intervals greater than 1 week andobtained a low cure rate (20%).

Another important fact to consider before the applicationof cryotherapy is the phototype of skin. In patients withphototype V, for example, depigmentation may occur. It isalso necessary to investigate the tendency of keloid formation[77].

Cryotherapy is a clinically useful alternative and has few,but not serious, adverse effects. It has a high cure rate whenconsidering the size of the lesion and the frequency of thesessions.

4.9. Ketoconazole. Ketoconazole is an antifungal that inter-feres with the biosynthesis of ergosterol, an important cellmembrane constituent, essential for the viability and survivalof fungi and trypanosomatids. The target of Ketoconazoleis the C14𝛼-demethylase and, thus, it interferes with thedimethylation of the sterol and, consequently, inhibits thesynthesis of ergosterol [79].

Oral ketoconazole alone has been tested for the treatmentof CL for several years and has shown different cure rates[80–83]. In this review, we included the study of El-Sayedand Anwar (2010) [21], which tested the combination ofintralesional sodium stibogluconate and oral ketoconazole(600 mg/day). This combination was more effective than theketoconazole and sodium stibogluconate alone.

Saenz et al. (1990) [80], using ketoconazole alone (600mg/day), obtained a cure rate of 73% and Salamanpour et al.(2001) [82] found a cure rate of 89% in the treatment withketoconazole (600 mg/day) alone.

Possibly the species is a determinant factor in the effi-cacy of ketoconazole. WHO recommends ketoconazole (600mg/day) as the treatment regimen for CL in the New World,specifically when the etiologic agent is Leishmania mexicana,although there are reports of its efficacy in other species [4].El-Sayed and Anwar (2010) [21] did not identify the speciesin their study. Saenz et al. (1990) [80] also did not identifyit, but their study was conducted in Panama. Salmanpouret al. (2001) [82] cited that the patients had Old World CL.Ramanathan et al. (2011) [83] demonstrated efficacy in thetreatment of CL by Leishmania panamensis. With respectto ketoconazole resistance, Andrade-Neto et al. (2012) [84]demonstrated that Leishmania amazonensis can up-regulatetheC-14 demethylase in response to ketoconazole, whichmaycontribute to its resistance to this drug.

Oral administration of ketoconazole combined withintralesional sodium stibogluconate for the treatment of CLis shown acceptable risk with specialized monitoring and noserious adverse effects and in administration are reported.

4.10. Pentoxifylline. Pentoxifylline is a derivative of dimethyl-xanthine classified as a vasodilator agent. It exerts effects ondifferent cell types, such as reduction of the expression ofadhesion molecules with ICAM- 1 in keratinocytes and E-selectin in endothelial cells, inhibition of TNF-𝛼 synthesis,IL-1 and IL-6 and antifibrinolytic effects [14, 85].

In particular, pentoxifylline may potentiate the actionof pentavalent antimonials primarily by two mechanisms:increase in the expression of the inducible nitric oxide syn-thase (iNOS) and, consequently, increase in the production ofnitric oxide, and anti-TNF-𝛼 action [86, 87]. Brito et al. (2014)[88] observed that patients treated with pentoxifylline (400mg - 3 times per day) combined withmeglumine antimoniate(20 mg5+/kg/day) had greater TNF-𝛼 suppression than thosetreated withmeglumine antimoniate alone (20mg5+/kg/day),and cure rates were higher in the combined group than in thesecond group.

Machado et al. (2007) [15] demonstrated in theirstudy that the combination of meglumine antimoniate (20mg5+/kg/day) and pentoxifylline (400 mg - 3 times per day)potentiated the effect of the meglumine antimoniate, sincethe combination resulted in 82% of cure in patients withmucosal leishmaniasis, while meglumine antimoniate (20mg5+/kg/day) alone had a cure rate of 41.6%. Sadeghian andNilforoushzadeh (2006) [17], in which this same combinationwas tested to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis (in endemic areaforLeishmaniamajor) and resulted in 81.3% cure versus 51.6%for meglumine antimoniate alone. In contrast, at the same

Dermatology Research and Practice 17

conditions in the cited studies, Brito et al. (2017) [31] reporteda cure rate of 43% for a combination of pentoxifylline andmeglumine antimoniate to treat cutaneous leishmaniasiscaused by Leishmania braziliensis, as divergences in cure ratesmay be related to intrinsic characteristics of each patient topentoxifylline, and the specie of Leishmania.

The anti-TNF-𝛼 action of pentoxifylline makes its useinteresting, mainly in cases of mucosal and/or treatment-refractory leishmaniasis, since this cytokine is the mainresponsible for mucosal damage. There have been reports ofsuccess in the combination of pentoxifylline and meglumineantimoniate in the treatment of treatment-refractory cases[14] and with high production of TNF-𝛼 [89] or recurrentcases [90].

For Lessa et al. (2001) [14], the efficacy of the combinationpentoxifylline and meglumine antimoniate should make itthe second choice in the treatment, since the administrationis oral and has fewer adverse effects than amphotericin B.

The efficacy of pentoxifylline in combination with meg-lumine antimoniate in the treatment of mucocutaneousleishmaniasis, even in cases refractory to conventional and/orrecurrent treatment, added to few and not severe effects,makes this combination a good therapeutic alternative clin-ically useful for treatment of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis.However to treat cutaneous leishmaniasis with this com-bination it is necessary to take into account the speciesinvolved, since in cases caused by Leishmania braziliensis thiscombination showed not efficacious and not useful.

4.11. Clinical Implications. The first choice drugs for thetreatment of cutaneous or mucocutaneous leishmaniasis donot always show the expected result, so the association ofthese conventional drugs with others drugs or modalities oftherapy, such as local therapies have good cure rates, oftenhigher than those of the drugs of choice, and few adverseeffects. Above all, the combination with immunomodulatorsseems to be promising, even with limited numbers studyand patient it was surprisingly effective, revealing higherefficacy and few adverse effects. In the case of combinationwith local application therapies, the diameter of the lesionappears to be an important factor for successful treatment.In addition to efficacy, many combinations are easy toadminister by the patient andwithout the need for specializedmonitoring, what represents an advantage for use in moreisolated communities.

4.12. Strengths and Limitations of the Study. This system-atic review has gone through many steps in its develop-ment. The precision in publications’ search was guaranteedby two databases. Publications’ identification criteria weremonitored and discussed in many steps of the research toguarantee robustness and rigor of the findings. Special carewas also taken for the identification of the MeSH terms,which were decided by many researchers and by consensus,providing good sensitivity and specificity. The publications’findings were organized and detailed in four tables for betterclarity and quality of data. Concerning the limitations, weidentified that only four of the 16 articles included in the

review highlighted the limitations topic (Llanos Cuentas etal. 2010; Khatami et al. 2013; Farajzadeh et al. 2015; Brito etal. 2017). Other limitations were the inclusion of only twodatabases, with publications merely in English comprisingthe period from 12/2004 to 6/2017. The considerable het-erogeneity between the articles included, mainly due to thesignificant variation of both the substances used and theresearch regions, made it impossible to analyze the data moreprecisely, for example through meta-analysis. Despite theselimitations, we believe the results can contribute positively forthe treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis andmucocutaneousleishmaniasis.

5. Conclusion

The combination of pentavalent antimonial drugs with otherdrugs seems to be a good alternative to conventional treat-ment, since they presented good cure rates, often higher thanthose of the drugs of choice, and few adverse effects. There-fore, this type of combination deserves to be investigated inmore detail by clinical trials and prospective studies withmore robust population sample to reinforce the effectivenessand safety that this alternative treatment provides to thepatient.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Conselho Nacionalde Desenvolvimento Cientıfico e Tecnologico and theCoordenacao de Aperfeicoamento de Pessoal de Nıvel Supe-rior for the financial support. A summary version of thiswork, with the same title, was presented orally at the VInternational Congress of the CCS held in Maringa, Brazil,in 2018.Therefore, the authors thank the congress organizingcommittee for this.

References

[1] WHO,Neglected tropical diseases, 2016, http://www.who.int/ne-glected diseases/news/WHO implement epidemiological sur-veillance leishmaniasis/en/.

[2] WHO, Leishmaniasis, 2017, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs375/en/.

[3] J. Blum, D. N. Lockwood, L. Visser et al., “Local or sys-temic treatment for New World cutaneous leishmaniasis? Re-evaluating the evidence for the risk of mucosal leishmaniasis,”International Health, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 153–163, 2012.

[4] World Health Organization, Control of the leishmaniases,World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser, 2010, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44412/1/WHO TRS 949 eng.pdf.

[5] E. M. Andersen, M. Cruz-Saldarriaga, A. Llanos-Cuentas etal., “Comparison of meglumine antimoniate and pentamidinefor Peruvian cutaneous leishmaniasis,”The American Journal ofTropical Medicine and Hygiene, vol. 72, pp. 133–137, 2005.

18 Dermatology Research and Practice

[6] I. Kevric, M. A. Cappel, and J. H. Keeling, “New world and oldworld leishmania infections: a practical review,” DermatologicClinics, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 579–593, 2015.

[7] G. A. S. Romero, M. V. De Farias Guerra, M. G. Paes, and V.De Oliveira Macedo, “Comparison of cutaneous leishmaniasisdue to Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis and L. (V.) guyanensisin Brazil: therapeutic response to meglumine antimoniate,”TheAmerican Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, vol. 65, no.5, pp. 456–465, 2001.

[8] E. Negera, E. Gadisa, J. Hussein et al., “Treatment responseof cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania aethiopica tocryotherapy and generic sodium stibogluconate from patientsin Silti, Ethiopia,” Transactions of the Royal Society of TropicalMedicine and Hygiene, vol. 106, no. 8, pp. 496–503, 2012.

[9] N. Safi, G. D. Davis, M. Nadir, H. Hamid, L. L. Robert, andA. J. Case, “Evaluation of Thermotherapy for the Treatment ofCutaneous Leishmaniasis in Kabul, Afghanistan: A Random-ized Controlled Trial,”MilitaryMedicine, vol. 177, no. 3, pp. 345–351, 2012.

[10] S. Shamsi Meymandi, S. Zandi, H. Aghaie, and A. Hesh-matkhah, “Efficacy of CO

2laser for treatment of anthro-

ponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis, compared with combinationof cryotherapy and intralesional meglumine antimoniate,” Jour-nal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology,vol. 25, no. 5, pp. 587–591, 2011.

[11] A. Asilian, A. Sadeghinia, G. Faghihi, and A. Momeni,“Comparative study of the efficacy of combined cryotherapyand intralesional meglumine antimoniate (Glucantime�) vs.cryotherapy and intralesional meglumine antimoniate (Glu-cantime�) alone for the treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis,”International Journal of Dermatology, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 281–283,2004.

[12] A. Asilian and M. Davami, “Comparison between the efficacyof photodynamic therapy and topical paromomycin in thetreatment of Old World cutaneous leishmaniasis: A placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial,”Clinical and ExperimentalDermatology, vol. 31, no. 5, pp. 634–637, 2006.

[13] R. Reithinger, M. Mohsen, M. Wahid et al., “Efficacy ofThermotherapy to Treat Cutaneous Leishmaniasis Caused byLeishmania tropica in Kabul, Afghanistan: A Randomized,Controlled Trial,” Clinical Infectious Diseases, vol. 40, pp. 1148–1155, 2005.