Parry -the_evolution_of_the_art_of_music

-

Upload

edgar-arruda -

Category

Entertainment & Humor

-

view

266 -

download

0

Transcript of Parry -the_evolution_of_the_art_of_music

MusicThe systematic academic study of music gave rise to works of description, analysis and criticism, by composers and performers, philosophers and anthropologists, historians and teachers, and by a new kind of scholar - the musicologist. This series makes available a range of significant works encompassing all aspects of the developing discipline.

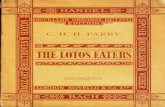

The Evolution of the Art of MusicC. Hubert H. Parry (1848–1918), knighted in 1902 for his services to music, was a distinguished composer, conductor and musicologist. In the first of these roles he is best known for his settings of Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’ and the coronation anthem ‘I was glad’. He was an enthusiastic teacher and proselytiser of music, believing strongly in its ability to widen and deepen the experience of Man, and this book, published in 1896 as a revised version of his 1893 The Art of Music, appeared in a series called ‘The International Scientific Series’. Parry’s intention is to trace the origins of music in ‘the music of savages, folk music, and medieval music’ and to show ‘the continuous process of the development of the Musical Art in actuality’.

C A M B R I D G E L I B R A R Y C O L L E C T I O NBooks of enduring scholarly value

Cambridge University Press has long been a pioneer in the reissuing of out-of-print titles from its own backlist, producing digital reprints of books that are still sought after by scholars and students but could not be reprinted economically using traditional technology. The Cambridge Library Collection extends this activity to a wider range of books which are still of importance to researchers and professionals, either for the source material they contain, or as landmarks in the history of their academic discipline.

Drawing from the world-renowned collections in the Cambridge University Library, and guided by the advice of experts in each subject area, Cambridge University Press is using state-of-the-art scanning machines in its own Printing House to capture the content of each book selected for inclusion. The files are processed to give a consistently clear, crisp image, and the books finished to the high quality standard for which the Press is recognised around the world. The latest print-on-demand technology ensures that the books will remain available indefinitely, and that orders for single or multiple copies can quickly be supplied.

The Cambridge Library Collection will bring back to life books of enduring scholarly value across a wide range of disciplines in the humanities and social sciences and in science and technology.

The Evolution of the Art of Music

C. Hubert H. Parry

CAMBRID GE UNIVERSIT Y PRESS

Cambridge New York Melbourne Madrid Cape Town Singapore São Paolo Delhi

Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York

www.cambridge.orgInformation on this title: www.cambridge.org/9781108001793

© in this compilation Cambridge University Press 2009

This edition first published 1896This digitally printed version 2009

ISBN 978-1-108-00179-3

This book reproduces the text of the original edition. The content and language reflect the beliefs, practices and terminology of their time, and have not been updated.

T H E

INTERNATIONAL SCIENTIFIC SERIES,

VOL. LXXX.

THE EVOLUTION OF

THE ART OF MUSIC

BY

C. HUBERT H. PARRYD.C.L. DURHAM, M.A. OXON.

MUS. DOC. OXON., CANTAB., AND DUBLIN; HON. FELLOW

OF EXETE1! COLLEGE, OXFOED

LONDON

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER, & CO. L™PATERNOSTER HOUSE, CHARING CROSS ROAD

1896

The rights of translation and of reproduction are reserved.

PEEFACE

THE following outline of the Evolution of Musical Art wasundertaken, at the invitation of Mr. Kegan Paul, somewhereabout the year 1884. Its appearance was delayed by theconstantly increasing mass of data and evidence about themusic of savages, folk music, and mediaeval music; and bythe necessity of exploring some of the obscure and neglectedcorners of the wide-spread story of the Art. And though thesubject was almost constantly under consideration, with afew inevitable interruptions, the book was not completed till

1893.Obligations in many directions should be acknowledged—

especially to Mr. Edward Dannreuther, for copious advice,suggestions, and criticisms during the whole time the workwas in hand; to Miss Emily Daymond, of Holloway College,for reading the proofs; to Mr. W. Barclay Squire, for untiringreadiness to make the resources of the Musical Library of theBritish Museum available; to Mr. A. J. Hipkins, for advis-ing about the chapter on Scales; and to Mr. Herbert Spencer,Mr. H. H. Johnston, and many others for communicationsabout the dancing and music of savage races.

The title, under which the book was first published in 1893,was evidently misleading, and has therefore been slightlyamplified, with the view of suggesting the intention of the work

vi PREFACE

more effectually. It is hoped that the drawback under whichit labours, through the impossibility of introducing manymusical illustrations in such a narrow space, may before longbe remedied by the publication of a parallel volume, consistingalmost entirely of musical excerpts and works which are noteasily accessible to the general public, so arranged as to showthe continuous process of the development of the Musical Artin actuality.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

PRELIMINARIESPA<;E

The artistic disposition—Susceptibility and impulse towards ex-pression—Music in the rough, in animals, in savages—Designessential—Expressive cries and expressive gestures leading tosong and dancing—Melody and rhythm—The art based uponcontrasts—Nervous exhaustion and its influence on the art—Tension and relaxation—Organisation . . i

CHAPTER II

SCALES

Definite relations of pitch indispensabl"—Slow development of scales—Slender beginnings—Practicable intervals—Scales variable inaccordance with the purposes for which they are wanted—Melodic scales—Heptatonic and pentatonic—Ancient Greeksystem—Modes—Persian system—Subtle organisation—Indiansystem—Modes and ragas—Chinese system—Japanese—Javese—Siamese—Bagpipe scale—Beginnings of modern Europeansystem—Classification of notes of scale—Temperament . 15

CHAPTER III

FOLK-MUSIC

Music of savages—First efforts in the direction of design—Ele-mentary types—Reiteration of phrases—Sequences—Tonality—Ornament—Pattern tunes—Universality of certain types ofdesign—Racial characteristics—Expression and design—Highestforms—Decline of genuine folk-music . . . . 47

viii CONTENTS

CHAPTER IV

INCIPIENT HARMONYPAGE

Music and religion—Music of early Christian Church—Doublingmelodies—Organutn or diaphony—Counterpoint or descant—Singing several tunes at once—Motets—Influence of diaphony—Canons—Cadences—Indefiniteness of early artistic music—Influence of the Church . . . . . . . . 82

CHAPTER V

THE ERA OF PURE CHORAL MUSIC

Universality of choral music—Aiming at beauty of choral effect—Contrapuntal effect—Harmonic effect—Secular forms of choralmusic—Madrigals — Influence of modes—Accidentals—Earlyexperiments in instrumental music—Imitations of choral forms—Viols — Lutes — Harpsichords — Organ — Methods — Homo-geneity . . . . . . . . . . . 1 0 3

CHAPTER VI

THE RISE OF SECULAR MUSIC

Reforming idealists—First experiments in opera, oratorio, and can-tata — Recitative — Beginnings indefinite—Expression — Ten-dency towards definition—Melody—Arias—Realism—Tendencyof instrumental music towards independence . . . . 1 2 5

CHAPTER VII

COMBINATION OF OLD METHODS AND NEWPRINCIPLES

Renewed cultivation of contrapuntal methods—Influence of Italiantaste and style upon Handel—His operas—His oratorios—J. S.Bach—Influences which formed his musical character—Differ-

CONTENTS ix

PAGE

ence of Italian and Teutonic attitudes towards music—Instru-mentation—Choral effect—Italian oratorio—Passion music—Public career of Handel—Bach's isolation—Ultimate influenceof their work . 157

CHAPTER VIII

CLIMAX OF EARLY INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC

Early instrumental music contrapuntal—Fugue—Organ music—Orchestral music—Harpsichord and clavichord—Suites andpartitas?—" Das wohltemperirte Clavier "—Unique position ofJ. S. Bach in instrumental music . . . . 175

CHAPTER IX

BEGINNINGS OF MODERN INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC

Systematisation of harmony—The early Italian violinists—Distribu-tion of contrasted types of movements in groups—Violinsonatas — Harpsichord sonatas — Operatic influence — Overtureand sinfonia . . . . . . . . . . 193

CHAPTER X

THE MIDDLE STAGE OF MODERN OPERA

Formality of the opera serin—Intermezzos—Comic features—Style—Gluck arid expression—Piccini—Mozart—Italian influence—Idomeneo — Instrumentation — Teutonic aspiration — Artisticachievement 213

CHAPTER XI

THE MIDDLE STAGE OF "SONATA" FORM

Self-dependent music and design—Successive stages of development—Subject and form—Influences which formed the musicalcharacters of Haydn and Mozart—Symphonies—Orchestration—Quartetts—Increase of variety of types—High organisationin a formal sense . . . . . . . 233

x CONTENTS

CHAPTER XII

BALANCE OF EXPRESSION AND DESIGNPAGE

Development of resources—Importance of Mozart's work at theparticular moment—Beethoven's impulse towards expression—His keen feeling for design—Preponderance of sonatas in hisworks—His three periods—Richness of sound—The pianoforte—The orchestra—Use of characteristic qualities of tone—Expansion of design—Expression—The scherzo—Close textureof Beethoven's work—His devices—Programme . . . 249

CHAPTER XIII

MODERN TENDENCIES

Characterisation—Increase of impulse towards the embodiment ofdefinite ideas external to music—Spohr—Weber—MendelssohnBerlioz—Instrumentation—Resuscitation of oratorio—Its peculi-arities—Change in the aspect of choral writing—Secular choralworks—Declamation—Solo song—Treatment of words—Expres-sion and design —Pianoforte music—Obviousness and obscurity—Realism—Great variety of traits and forms . . . - 2 7 3

CHAPTER XIV

MODERN PHASES OF OPERA

Italian disposition and its fruits—French opera—German ideals—Wagner—Early influences—Instinct and theory—Exile andreflection—Maturity—Methods and principles—Leit motive—Tonality—Instrumental effect—Design and expression again—Declamation and singing—Profusion of resources . . 306

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION 333

INDEX 3 3 9

THE ART OF MUSIC

CHAPTER I

PRELIMINARIES

THERE are probably but few people in the world so morose asto find no pleasure either in the exercise or the receipt ofsympathy, and it is to be hoped there are very few so blindor perverse as to regard it as an undesirable and useless factorin the human psychological outfit. Whether it is the higherdevelopment of an original instinct which enabled mankindto rise above the rest of the animal world by co-operation andmutual helpfulness, or whether it is the outcome of the stateof mutual dependence which is the lot of human beings, it isobviously a quality without which society could hardly continueto exist in the complicated state of organisation at which it hasarrived. The jarring interests of hurrying, striving millionsrequire something more than mere cold-blooded utilitarianmotives to keep them properly balanced; and in matters ofeveryday life the impulses which tend to mutual helpfulness andforbearance are fed by the ordinary phases of this omnipresentinstinct. But there are many kinds and infinitely variabledegrees of sympathy, and some people love best to bestow it,and some there are who much prefer to receive it. Andapart from the ordinary sympathetic consideration of every-day life on the one hand, and of the devoted sympatheticheroism which often rises to the pitch of entire sacrifice ofself on the other, most people have some special lines andsubjects which excite their sympathetic instincts, and make

2 THE ART OF MUSIC

them specially conscious of the delight of fellowship in tastesand interests, whether it be politics, science, literature, art, orsport; and in such circumstances the instinct, without passingthe bounds of normal healthiness of tone, may rise to a degreeof refined responsive sensitiveness, which is productive of a veryhigh quality of happiness.

But of all types of humanity, those who are possessed withartistic dispositions are notoriously most liable to an absorb-ing thirst for sympathy, which is sometimes interpreted bythose who are not artistic as a love of approbation or noto-riety ; and though a morbid development of the instinct maysometimes degenerate into that unhappy weakness, the almostuniversal prevalence of the characteristic cannot be summarilyaccounted for on such superficial grounds, but deserves morediscriminating consideration. The reason that artistic andpoetic human beings are generally characterised by such a con-spicuous development of their sympathetic instincts appearsto lie in the fact that they are peculiarly susceptible to beautyof some kind, whether it be the obvious external kind ofbeauty, or the beauty of thought and human circumstance;and that the keenness of their pleasure makes them long toenhance their own enjoyments by bringing their fellow-mensympathetically into touch with them. From this point ofview the various arts of painting, sculpture, music, literature,and the rest, are the outcome of the instinctive desire toconvey impressions and enjoyments to others, and to re-present in the most attractive and permanent forms theideas, thoughts, circumstances, scenes, or emotions whichhave powerfully stirred the artists' own natures. It is theintensity of the pleasure or interest the artist feels in whatis actually seen or present to his imagination that drives himto utterance. The instinct of utterance makes it a necessityto find terms which will be understood by other beings inwhom his appeal can strike a sympathetic chord; and thestronger the delight in the thought or feeling, the greater isthe desire to make the form in which it is conveyed un-mistakably clear and intelligible. But intelligibility dependsto a great extent in all things upon principles of structure,

PRELIMINARIES 3

and structure implies design; hence the instinctive desire tomake a thought or artistic conception unmistakably intelligibleis a great incentive to the development of design.

Design has different aspects in different arts; but in all itis the equivalent of organisation in the ordinary affairs oflife. It is the putting of the various factors of effect in theright places to make them tell. In some arts design seemsthe very essence and first necessity of existence, and thoughin music it is less easily understood by the uninitiated thanin other arts, it is in reality of vital importance. Music indeedcannot exist till the definiteness of some kind of design ispresent in the succession of the sounds. The impressionproduced by vague sounds is vague, and soon passes awayaltogether. They take no permanent hold on the mind tillthey are made definite in relation to one another, and aredisposed in some sort of order by the distribution of theirup and down motion or by the regularity of their rhythmicrecurrence. Then the impression becomes distinct, and itsdefiniteness makes it permanent. In most arts it is thepermanence of the enjoyment rather than that of the artisticobject itself which is dependent on design. In sculpture, forinstance, the very materials seem to ensure permanence; butundoubtedly a piece of sculpture which is seriously imperfectin design soon becomes intolerable, and is willingly abandonedby its possessor to the disintegrating powers of rain and frost,or to some corner where it can be conveniently forgotten.Painting does not seem, at first sight, to require so much skillin designing, because the subjects which move the artist toexpress himself are so obvious to all men; but neverthelessthe most permanent works of the painting art are not thosewhich are mere skilful imitations of nature, but those intowhich some fine scheme of design is introduced to enhance thebeauty or inherent interest of the artist's thought.

In music, form and design are most obviously necessary, notonly because without them the impression conveyed is indefiniteand fugitive, but also because the very source and origin of itsinfluence on human beings is so obscure. To some people beautyof form in melody or structure seems the chief excuse for the

4 THE ART OF MUSIC

art's existence; and even to more patient observers it seems tobe on a different footing from all the other arts in respect of itsmeaning and intention. Even the most unsophisticated dullardcan see what inspired the painter or the sculptor to express him-self, but he cannot understand what music means, nor what itis intended to express; and many practical people look upon itas altogether inferior to other arts, because it seems to have noobviously useful application. Painting naturally appears to theaverage mind to be an imitative art; and, drawing a conclusionfrom two premises which are both equally false, some peoplehave gone on to suppose that the only possible basis of allarts, including music, is imitation, and to invent the childishtheory that the latter began by imitating birds' songs. There isno objection to such a theory if considered as a pretty poeticalmyth, and instances of people imitating birds in music can ofcourse be substantiated; but as a serious explanation of theorigin of music it is both too trivial and too incompatiblewith fact to be worth discussing. In reality, both arts aremuch on the same footing, for painting is no more a purelyimitative art than music. People deliberately copy naturechiefly to develop the technique which is necessary to enablethem in higher flights to idealise it, and to present their imagin-ings in the terms of design which are their highest sanction.It is just when a painter deliberately sets himself to imitatewhat he sees that he least deserves the name of an artist.The devices for imitating nature and throwing the unsophisti-cated into ecstasies, because the results are so like what theythemselves have seen, are the tricks of the trade, and, till theyare put to their proper uses, are on no other footing than thework of a good joiner or a good ploughman. It is only whenthey are used to convey the concentrated ideals of the mindof the artist in terms of beautiful or characteristic design thatthey become worthy of the name of art. Music is really muchon the same footing, for the history of both arts is equallythat of the development of mastery of design and of thetechnique of expression. The only real difference is that theartist formulates impressions received through the eyes, andthe musician formulates the direct expression of man's inner-

PRELIMINARIES 5

most feelings and sensibilities. In fact, the arts of paintingand sculpture and their kindred are the expression of theouter surroundings of man, and music of what is within him;and consequently the former began with imitation, and thelatter with direct expression.

The story of music has been that of a slow building upand extension of artistic means of formulating in terms of de-sign utterances and counterparts of utterances which in theirraw state are direct expressions of feeling and sensibility.Utterances and actions which illustrate the raw material ofmusic are common to all sentient beings, even to those which thecomplacency of man describes as dumb. A clog reiterating shortbarks of joy on a single note at the sight of a beloved friendor master is as near making music as the small human babyvigorously banging a rattle or drum and crowing with exuberanthappiness. The impulse to make a noise as an expression offeeling is universally admitted, and it may also be noticed that ithas a tendency to arouse sympathy in an auditor of any kind,and an excitement analogous to that felt by the maker of thenoise. A hound that has picked up the scent soon starts theresponsive sympathy of the chorus of the pack; a cow wailingthe loss of her calf often attracts the attention and response ofher sisters in neighbouring fields; and the uproarious meetingsof cats at night afford familiar instances of the effect suchincipient music is capable of exerting upon the feline dis-position.

Human beings are quite equally sensitive to all forms ofexpression. Even tricks of manner, and nervous gestures,and facial distortions are infectious; and very sensitive andsympathetic people are particularly liable to imitate uninten-tional grimaces and fidgets. But sounds which are utteredwith genuine feeling are particularly exciting to humancreatures. The excitement of a mob grows under the influenceof the shouts its members utter; and takes up with equalreadiness the tone of joy, rage, and defiance. Boys in thestreet drive one another to extravagances by like means; and,as Cicero long ago observed, the power of a great speaker oftendepends not so much on what he says, as upon the skill with

6 THE ART OF MUSIC

which he uses the expressive tones of his voice. All suchutterances are music in the rough, and out of such elementsthe art of music has grown, just as the elaborate arts ofhuman speech must have grown out of the grunts and whin-ings of primeval savages. But neither art nor speech beginstill something definite appears in the texture of its material.Some intellectual process must be brought to bear upon bothto make them capable of being retained in the mind; and theearly steps of both are very similar. Just as among the earlyancestors of our species, speech would begin when the in-definite noises which they first used to communicate with oneanother, like animals, passed into some definite sound whichconveyed to the savage ear some definite and constant mean-ing ; so the indefinite cries and shouts which expressed theirfeelings began to pass into music when a few definite noteswere made to take the place of vague, irregular shouting.And as speech grows more copious in resources when thedelicate muscles of the mouth and throat are trained toobedience in the utterance of more and more varied inflections,and the ear is trained to distinguish niceties which have dis-tinct varieties of meaning; so the resources of music increasedas the relations of more and more definite notes were estab-lished, in obedience to the development of musical instinct,and as the ear learnt to appreciate the intervals and the mindto retain the simple fragments of tune which resulted.

The examination of the music of savages shows that theyhardly ever succeed in making orderly and well-balancedtunes, but either express themselves in a kind of vague wail orhowl, which is on the borderland between music and informalexpression of feeling, or else contrive little fragmentary figuresof two or three notes which they reiterate incessantly over andover again. Sometimes a single figure suffices. When theyare clever enough to devise two, they alternate them, butwithout much sense of orderliness; and it takes a long periodof human development before the irregular haphazard alter-nation of a few figures becomes systematic enough to havethe aspect of any sort of artistic unity. Through such crudeattempts at music, scales began to grow; but they developed

PRELIMINARIES 7

extremely slowly, and it was not till special races had arrivedat an advanced state of intellectuality that men began to payany attention to the relations of notes to one another, or tonotice that such abstractions could exist apart from the music.And it has even sometimes happened that races who have de-veloped up to an advanced standard of intellectuality have notsucceeded in systematising more than a very limited range ofsounds.

But complete musical art has to be made definite in otherrespects besides mere melodic up and down motion. Thesuccessive moments had to be regulated as well as merechanges of pitch, and this was first made possible by theelement of rhythm.

All musical expression may be broadly distributed into twogreat orders. On the one hand, there is the rhythmic part,which represents action of the nature of dance motions; andon the other, all that melodic part which represents somekind of singing or vocal utterance. Rhythm and vocal ex-pression are by nature distinct, and in very primitive statesof music are often found independent of one another. Therhythmic music is then defined only by the pulses, and has nochange of pitch j while purely melodic music has change ofpitch, but no definition or regularity of impulse. The latteris frequently met with among savage races, and even as nearthe homes of highest art as the out-of-the-way corners of theBritish Isles. Pure, unalloyed rhythmic music is found inmost parts of the uncivilised globe; and the degree of excite-ment to which it can give rise, when the mere beating of adrum or tom-tom is accompanied by dancing, is well knownto all the world. It is also a familiar fact that dancingoriginates under almost the same conditions as song or anyother kind of vocal utterance; and therefore the rhythmicelements and the melodic elements are only different formsin which the same class of feelings and emotions are expressed.

All dancing is ultimately derived from expressive gestureswhich have become rhythmic through the balanced arrange-ment of the human body, which makes it difficult for similaractions to be frequently repeated irregularly. The evidence

8 THE ART OF MUSIC

of careful observers from all parts of the globe agrees indescribing barbarous dances as being obvious in their inten-tion in proportion to the low standard of intelligence of thedancers. Savages of the lowest class almost always expressclearly in their dance gestures the states of mind or thecircumstances of their lives which rouse them to excitement.The exact gestures of fighting and love-making are reproduced,not only so as to make clear to the spectator what is meantby the rhythmic pantomime, but even in certain cases so asto produce a frenzy in the mind of both spectators andperformers, which drives them to deeds of wildness andferocity fully on a par with what they would do in the realcircumstances of which the dancing is merely an expressivereminiscence.

In these respects, dancing, in its earlier stages, is an exactcounterpart of song. Both express emotions in their respectiveways, and both convey the excitement of the performers tosympathetic listeners; and both lose the obvious traces oftheir origin in the development of artistic devices. As theruder kinds of rhythmic dancing advance and take more ofthe forms of an art, the significance of the gestures ceasesto be so obvious, and the excitement accompanying the per-formance tones down. An acute observer still can trace thegestures and actions to their sources when the conventionsthat have grown up have obscured their expressivp meaning,and when the performers have often lost sight of them ; andthe tendency of more refined dancing is obviously to disguisethe original meaning of the performance more and more, andmerely to indulge in the pleasure of various forms of rhythmicmotion and graceful gesture. But even in modern timesoccasional reversions to animalism in depraved states of societyrevive the grosser forms of dancing, and forcibly recall theprimitive source of the art.

In melodic or vocal music the process has been exactlyanalogous. The expressive cries soon began to lose theirdirect significance when they were formalised into distinctmusical intervals. It is still possible to find among lowtyorganised savages examples of a kind of music which is so

PRELIMINARIES 9

little defined in detail that the impulsive cry or howl ofexpression is hardly disguised at all by anything which couldbe described as a definite interval. But the establishment of adefinite interval of any sort puts the performer under restric-tions, and every step that is made in advance hides theoriginal meaning of the utterance more and more away underthe necessities of artistic convention. And when little frag-ments of melody become stereotyped, as they do in everysavage community sufficiently advanced to perceive and re-member, attempts are made to alternate and contrast themin some way; and the excitement of sympathy with anexpressive cry is merged in a crudely artistic pleasure derivedfrom the contemplation of something of the nature of apattern.

It is obvious that the rhythmic principle and the melodicprinciple begin very early to react upon one another. Savagesall over the world combine their singing and their dancing;and they not only sing rhythmically when regular set dancesare going on, but when they are walking, reaping, sowing,rowing, or doing any other of their daily labours and exerciseswhich admit of such accompaniment. By such means therhythmic and the melodic were combined, and it is no recklessinference that from some such form of combination sprungthe original rhythmic organisation of poetry.

But the tendency to revert to primitive conditions is fre-quently to be met with even in the most advanced stages ofart; and an antagonism, which it is one of the problems ofthe art to overcome, is persistent throughout its history. Invery quick music the rhythmic principle has an inevitabletendency to predominate, and in very slow music the melodicprinciple most frequently becomes prominent. But it mustbe remembered that the principle which represents vocal ex-pression applies equally to instrumental and to vocal music,and that rhythmic dance music can be sung. The differenceof principle between melodic quality and rhythmic qualityruns through the whole art from polka to symphony; and,paradoxical as it may seem, the fascination which some modernsensuous dance-tunes exercise is derived from a distinctly canta-

10 THE ART OF MUSIC

bile treatment of the tune, which appeals to the dance instinctthrough the languorous, sensuous, and self-indulgent side ofpeople's natures.

The antagonism shows itself as much in men as in the artitself. Dreamers and sentimentalists tend to lose their holdupon rhythmic energy; while men of energetic and vigoroushabits of mind set little store by expressive cantabile. Com-posers of a reflective and romantic turn of mind like Schumannexcel most in music which demands cantabile expression; andmen like Scarlatti, in rhythmic effect. This rule applies evento nations. Certain branches of the Latin race have had avery exceptional ability for singing, and have often shownthemselves very negligent of rhythmic definiteness; while theHungarians manifest a truly marvellous instinct for what isrhythmic; and the French, being a nation particularly givento expressing themselves by gesticulation, have shown a mostsingular predilection for dance rhythm in all branches of art.In the very highest natures the mastery of both forms ofexpression is equally combined ; and it is under such conditions,with musicians who have both methods of expression wellunder command, that music rises to its highest perfection; asthe use of the two principles supplies the basis of the widestcontrast of which the art is capable.

In this respect the two contrasting principles of expressionare types of a system of contrasts which is the basis of allmature musical design; and when the ultimate origin of allmusic, as direct expression of feeling and an appeal to sympa-thetic feeling in others, is considered, it is easy to see thatthe nature of the human creature makes contrast universallyinevitable. Fatigue and lassitude are just as certain to followfrom the exercise of mental and emotional faculties as fromthe exercise of the muscles ; and fatigue puts an end to thefull enjoyment of the thing which causes it. It is absolutelyindispensable in art to provide against it, and it is the instinctof the artist who gauges human sensibilities most justly insuch respects that enables him to reach the highest artistic per-fection in subtlety as well as scope of design. The mind firstwearies and then suffers pain from over-much reiteration of a

PRELIMINARIES I I

single chord, or of an identical rhythm, or of a special colour,or of a special fragment of melody; and even of a thing soabstract as a principle. In some of these respects the reasonis easily found in some obvious physiological fact, such as ex-haustion of nervous force or waste of tissue; but it appearscertain that the only reason why a similar explanation cannot beenunciated in connection with the more intangible departmentsof human phenomena is that the more refined and subtleproperties of organised matter are not yet perfectly understood.But it holds good, as a mere matter of observation, that the lawswhich apply in cases where the physiological reasons are clearapply also in less obviously physical cases. It is perfectly obviousthat when any part of the organism is exhausted, its energycan only be renewed by rest. But rest does not necessarily implycomplete lassitude of all the faculties. It is a very familiarexperience of hard-worked men that the best way to recoverfrom the exhaustion of a prolonged strain is to change entirelythe character of their work. Many of the phenomena of art areexplicable on this principle. Up to a certain point the humancreature is capable of being more and more excited by aparticular sound or a particular colour; but the excitementmust be succeeded by exhaustion, and exhaustion by pain,if the exciting cause is continued. If the general excitementof the whole being is to be maintained, it must be by rousingthe excitable faculties of other parts or centres of the organism;and it is while these other faculties or nerve-centres are beingworked upon that the faculties which have been exhaustedcan recover their tone. From this point of view a perfectlybalanced musical work of art may be described as one inwhich the faculties or sensibilities are brought up to a certainpitch of excitation by one method of procedure, and whenexhaustion is in danger of supervening, the general excitationof the organism is maintained by adopting a different method,which gives opportunity to the faculties which were gettingjaded to recover; and when that has been effected, thenatural instinct is to revert to that which first gave pleasure;and the renewal of the first form of excitation is enhancedby the consciousness of memory, together with that sense of

I 2 THE ART OF MUSIC

renewal of a power to feel and enjoy which is of itself a pecu-liar and a very natural satisfaction to a sentient being.

In the earlier stages of the art the struggle to arrive at asolution of the problem this proposes is dimly seen. As manhad only instinct to find his way with, it is not surprisingthat he was long in finding out means of managing and dis-tributing such contrasts. In the middle period of musicalhistory, when musical mankind had learnt its lesson, andtook a complacent view of its achievement, the method anduse of such contrasts became offensively obvious; but in themodern period they are disguised by infinite variety of musicaland sesthetical devices, and are necessarily made to recur withextraordinary frequency in proportion to the exhausting kindsof excitation employed by modern composers. In mature artthe systematisation of such contrasts is vital, and in immatureart it is incipient; and this fact is the most essential differ-ence between the two.

Of such types of contrast that of principle between therhythmic and the melodic on one hand, and of emotional andintellectual on the other, are the widest. The manner inwhich they are applied in the highest works of absolutemusic, such as symphonies and sonatas, will hereafter comeunder consideration.

In the earliest stage of musical evolution these respectiveprinciples show themselves especially in the manner in whichdefinition is obtained, since, as has been pointed out, definite-ness is the first necessity of art. From melodic utterancecame the development of the scale, from dancing the distribu-tion of pulses. The former is the result of man's instinct toexpress by vocal sounds, the latter of his instinct to expressby gestures and actions; and in the gradual evolution of theart the former supplies the element of sensibility, and thelatter that of energy; and when the nature of both is con-sidered it will be felt that these characteristics are in accord-ance with the nature of their sources.

To sum up. The raw material of music is found in theexpressive noises and cries which human beings as well asanimals give vent to under excitement of any kind; and

PRELIMINARIES 13

their contagious power is shown, even in the incipient stage,by the sympathy which they evoke in other sentient beings.Such cries pass within the range of art when they take anydefinite form, just as speech begins when vague signals ofsound give place to words; and scales begin to be formedwhen musical figures become definite enough to be remem-bered. In the necessary process of making the materialintelligible by definition, the rhythmic gestures of dancingplayed an important part, for by their means the successionof impulses was regulated. Both vocal music and dancingactually originate in the same sources; as they are differentways of manifesting similar types of feeling. But they are intheir nature contrasted, for in the one case it is the soundwhich forms the means of expression, and in the other it is amuscular action ; and the music which springs from these twosources is marked by a contrast of character in conformitywith their inherent differences. This contrast presents itselfas the widest example of that law of contrasts which runsthrough the whole art, and forms, next to the definition ofmaterial, its most essential feature.

The law of contrasts forms the basis of all the importantforms of the art, for a most obvious and natural reason. Theprinciple of sympathetic excitement upon which the art restsnecessarily induces exhaustion; and if there was no means ofsustaining the interest in some way which allowed repose tothe faculties that had been brought into exhausting activity,the work of art could go no further than the point at whichexhaustion began. It is therefore a part of the business ofthe art to maintain interest when one group of faculties is indanger of becoming wearied, by calling into play fresh powersof sensibility or thought, and giving the first centres time torecover tone. And as there would be no point in such adevice if the first group of faculties were not called intoexercise again when they had revived, the balance and rationaleof the process is shown in mature periods of art by a returnto the first principle of excitation or source of interest afterthe establishment of the first distinct departure from it,which embodied this inevitable principle of contrast.

14 THE ART OF MUSIC

Taking the most comprehensive view of the story of musicalevolution, it may be said that in the earlier stages, while theactual resources were being developed and principles of designwere being organised, the art passed more and more awayfrom the direct expression of human feeling. But after avery important crisis in modern art, when abstract beautywas specially emphasised and cultivated to the highest degreeof perfection, the balance swung over in the direction ofexpression again; and in recent times music has aimed atcharacteristic illustration of things which are interesting andattractive on other grounds than mere beauty of design or oftexture.

CHAPTER II

SCALES

THE first indispensable requirement of music is a series ofnotes which stand in some recognisable relation to one anotherin respect of pitch; for there is nothing which the mind canlay hold of and retain in a succession of sounds if the rela-tions in which they stand to one another are not appreciablydefinite. People who live in countries where an establishedscale is perpetually being instilled into every one's ears fromthe cradle till the grave, can hardly bring themselves to realisethe state of things which prevailed before any scales wereinvented at all. And the familiar habit of average humanityof thinking that what they are accustomed to is the only thingthat can be right, has commonly led people to think that whatis called the modern European scale is the only proper andnatural one. But it is quite certain that human creaturesdid exist for a very long time without the advantage of ascale of any sort; and that they did have to begin buildingup the first indispensable necessity of musical art, by decid-ing on a couple of notes or so which seemed satisfactory orattractive when heard one after the other; and that they didhave to be satisfied with a scale of the most limited descriptionfor a very long period.

What interval the primitive savage chose at the outset wasprobably very much a matter of accident; and inasmuch asscales used for melody are much less exact and stable thanthose which are used for harmony, it is quite certain that thereiteration of any interval whatever which men first took afancy for was only approximate, and that only in course ofages did instinctive consensus of opinion, possibly with thehelp of some primitive instrument, fasten definitely upon a

I 6 THE ART OF MUSTC

succession of sounds which to modern musicians would beclearly recognisable as a fourth or a fifth, or any otheracoustically explicable pair of notes.

It is advisable to guard at the outset against the familiarmisconception that scales are made first and music afterwards.Scales are made in the process of endeavouring to make music,and continue to be altered and modified, generation aftergeneration, even till the art has arrived at a high degree ofmaturity. The scale of modern harmonic music, whichEuropean peoples use, only arrived at its present conditionin the last century, after having been under a gradual processof modification from an accepted nucleus for nearly a thousandyears. Primeval savages were even worse off than mediaevalEuropeans. They did not know that they wanted a scale;and if they had known it they would have had neither acous-tical theory nor practical experience to guide them, nor evenexamples to show them how things ought not to be done.But it is very probable that in the end they selected aninterval which would approve itself to the acoustical theoristas well as to the unsophisticated ear of a modern lover of art.What that interval would be it is difficult to guess, and puretheoretic speculation is almost certain to be at fault in anydecision it comes to on the subject; but examination of thenumerous varieties of scales existent in the world, and ofsuch as are recorded approximately by ancient wind instru-ments, with the help of theory, may ultimately come verynear to solving the problem.

With reference to this point, it may be as well to recognisethat in the great number of scales which have developed up toa fair state of maturity, there are no two notes whatever thatinvariably stand in exactly the same relation to one anotherthroughout all systems. It might well be thought that theoctave could be excluded from consideration, as if it were notpart of a scale, but only the beginning of a new series. Buteven the octave is said to be a little out of tune in accordancewith the authorised theory of Chinese music. However, thisis clearly only a characteristic instance of the relation betweentheory and art, for no Chinese singer would be able consistently

SCALES I 7

to hit an exact interval which was just not a true octave,even if he was perverse enough to try. Of other familiarintervals the varieties are infinite. In our own system thefifth is less in tune than in many other systems, and in theSiamese scale there is nothing like a perfect fifth at all. Thefourth is an interval which is curiously universal in its appear-ance; but that, again, does not appear in the true Siamesescale, or in one of the Javese systems. An agreement in suchintervals as thirds and sixths is not to be expected. They areknown to be difficult intervals to learn, and difficult to placeexactly in theoretic schemes; and the result is that they areinfinitely variable in different scales. Some systems havemajor thirds, and some minor; and some have thirds that arebetween the two. Sixths are proportionately variable, and areoften curiously dependent upon the fifth for any status at all;and of such intervals as the second and seventh, and moreextreme ones, it must be confessed that they are so obviouslyartificial, that even in everyday practice in countries habitu-ated to one scale they are inclined to vary in accordance withindividual taste, and the lack of it.

Of all these intervals there are two which to a musicianseem obviously certain to have been the alternatives in thechoice of a nucleus. As has been pointed out, sixths, thirds,sevenths, and seconds are all almost inconceivable. They areall difficult to make sure of without education, and are un-stable and variable in their qualities. There remain only theintervals of the fourth and the fifth; and evidence as well astheory proves almost conclusively that one of these two formedthe nucleus upon which almost all scales were based; and oneof the two was probably the interval which primitive savagesendeavoured to hit in their first attempts at music.

But at the outset there comes in a very curious considera-tion which must of necessity be discussed before going further.If a modern musician, saturated in the habits of harmonicmusic, was asked for an opinion, he would say instantlythat it was impossible that any beings could have chosenthe fourth as their first interval; for that seems as hardto hit as thirds and sixths, and is even more inconclusive

I 8 THE ART OF MUSIC

and unsatisfying to our ears. But nevertheless the factremains that it is more often met with than the fifth inbarbarous scales, and if modern habits of musical thought canbe put aside the reason becomes obvious. Our modern har-monic system is an elaborately artificial product which has sofar inverted the aspect of things, that in order to get backto the understanding of ancient and barbarous systems wehave almost to set our usual preconceptions upside down.The modern European system is the only one in which har-mony distinctly plays a vital part in the scheme of artisticdesign. Our scale has had to be transformed entirely fromthe ancient modes in order to make the harmonic scheme ofmusical art possible; and in this process the attitude of thecultivators of other systems towards their scales has been lostsight of, and their perception of them has become almost alost sense. All other systems in the world are purely melodic.They present a single part as the whole material of music, andtheir scheme of aesthetics is totally alien from such a highly arti-ficial and intellectual development as that of modern Europeanmusic. In melodic systems the influence of vocal music isinfinitely paramount; in modern European art the instru-mental element is strongest. The sum of these considerationsis, that whereas in modern music people count their intervalsfrom the bass, and habitually think of scales as if they werebuilt upwards, in melodic systems it is in most cases thereverse. The most intelligent observers of Oriental systemsnotice that those who use them think of these scales astending downwards; and in certain particulars it is un-doubtedly provable that the practice of the ancients was inlike manner exactly contrary to ours. To take one con-sideration out of many as an illustration. The leading note ofmodern music always tends upwards; in other words, thenote which lies nearest to the most essential note of thescale, which is always heard in the final cadence, and is itsmost characteristic melodic feature, is below the final andrises to it. But this is exactly the reverse of the naturalinstinct in vocal matters, and contrary to the meaning ofthe word cadence.

SCALES 19

Most of the natural cadences of the voice in speaking tenddownwards. When a man raises his voice at the end of asentence he is either asking a question or expressing astonish-ment, and these are expressions of feeling which are in aminority. Pure vocal art follows the rule of the inflectionsin speaking; and in melodic systems, which are so much in-fluenced by the voice, cadences which rise to the final soundare almost inconceivable. They might be possible as ex-pressing great exaltation of feeling and power; but in mostcases a cadence means, artistically, a point of repose, and it isonly in very exceptional cases that a point of repose can beimagined on a high note; for the sustainment of a high noteimplies tension of vocal chords and effort, and such sustainedeffort can scarcely be regarded as a point of repose. Inmodern music the cadence is a harmonic process, and not amelodic one; and the upward motion from the leading noteto the tonic in cadences becomes intelligible as successivepositions of upper portions of the essential harmonies whichhappen to coincide with aesthetic requirements of melody whensupported by the chords which supply the other requisites ofa cadence simultaneously.

In melodic systems the majority of cadences are, as theword implies, made downwards; and undoubtedly in a majorityof cases the scale was developed downwards. In such circum-stances the difficulty of accounting for the more frequentappearance of the fourth than the fifth in scales used onlyfor melodic purposes disappears, for, going downwards, it isperfectly natural and easy to hit the interval of the fourth.Moreover, a notable peculiarity in the construction of manyand various scales increases the likelihood of the fourth havingbeen first chosen downwards, while it also explains the earlyappearance of the interval of a third. It is an indubitablefact that scales are developed by adding ornamental notes tothe more essential notes which have been first established;that is, notes which lie close to the essential notes, and to whichthe voice can waver indefinitely to and fro. A note of thiskind would not at first be very exact in its relative position.Mere uncertainty of voice would both suggest it and make it

20 THE ART OF MUSIC

variable; but undoubtedly it became a conspicuous feature ofthe cadences very early. If the fourth below was chosen bya musical people in developing the melodic scale downwards,it is likely to be verified by the frequent appearance of a notea semitone above it, as this would be the first addition madeto the scale, and would serve as the downward-tending leadingnote of the sjrstem.

There are many facts which justify this theory of thedevelopment of the scale, notably the construction of ancientGreek scale, and of the modern Japanese and the aboriginalAustralian scale, such as it is, and even of the scale indicatedby the phonographed tunes of some of the Red Indians ofNorth America. The first scale which history records ashaving been used by the Greeks is indeed absolutely nothingmore than a group of three notes, of which those which arefurthest apart make the interval of the fourth, and the re-maining note is a semitone above the lower note. This isprecisely the group of notes which analogy and argumentalike lead us to expect in the second stage of scale-makingunder melodic influences, and it affords an almost decisiveproof that the first interval chosen was the downward fourth.The Japanese system had no possible direct connection withthe Greek system, but the same group of notes is prominentlycharacteristic, and is undoubtedly used with persistent reitera-tion in their music. A modern European can get the effectfor himself by playing (J, and the A1? and G below it oneafter another, and reiterating them in any order he pleases,so long as he makes Ab" the last note but one, and G the final.The result is a curious reversal of our theories of musicalaesthetics, for G seems to become the tonic, and C the note ofsecondary importance—a state of things which is only con-ceivable if we think of the scale as tending downwards insteadof upwards.

But it is not to be denied that some races seem to havochosen a rising fifth as the nucleus of the scale, though it ismuch less common. The voice has to rise in singing as wellas to fall, and it is conceivable that some races should havethought more of the rise, which comes early in the musical

SCALES 2 I

phrase, than of the fall, which naturally comes at the end.One of the most astute and ingenious analysts of musicalscales, Mr. Ellis, thought that early experimenters in musicfound out the fifth as the corresponding note to the fourth onthe other side of the note from which the fourth was firstcalculated. The proof of the fifth's being recognised early—beyond its inherent likelihood—lies in the fact that some bar-barous scales comprise the interval of an augmented fourth,such as C to Fit, which is only intelligible in a melodic systemon the ground of the FIf being an ornamental note appendedto the G next above it. The original choice of a fifth or afourth as the basis or starting-point may have had somethingto do with the fact that nearly all known scales which havearrived at any degree of completeness can be grouped undertwo well-contrasted heads. The scales of China, Japan, Java,and the Pacific Islands are all pentatonic in their recognisedstructure. That is, they theoretically comprise only five noteswithin the limits of the octave, which are at various distancesfrom one another. But in this group the fifth above thelowest note is a prominent and almost invariable item. Therest of the most notable scales of the world are structurallyheptatonic, and comprise seven essential notes in the octave.Such are the scales of India, Persia, Arabia, probably Egypt,certainly ancient Greece and modern Europe. And in thesethe fourth was the interval which seems to have been firstrecognised. To avoid misconception, it is necessary to pointout that all these scales have been subjected to modificationsin practice, and their true nature has thereby been obscured.But the situation becomes intelligible by the analogy of ourown use of the modern scales. Ours are undoubtedly seven-note scales, as even children who practise them are painfullyaware; but in actual use a number of other notes, calledaccidentals, are admitted, both as modifications and as orna-ments. The key of 0 is clearly represented to every one bythe white keys of a pianoforte, but there is not a single blacknote which every composer cannot use either as an ornamentor as a modification without leaving the key of C. Similarly,nearly all the pentatonic scales have been filled in, and the

2 2 THE ART OF MUSIC

natives who use them are familiar with other notes besidesthe curious and characteristic formula of five ; but in the back-ground of their musical feelings the original foundation oftheir system remains distinct, just as the scheme of the keyof C remains distinct in the mind of an intelligent musicalperson even when a player sounds all the black notes in acouple of bars which are nominally in that key.

It undoubtedly made a great difference whether the fifth orfourth was chosen, for it is noticeable that small intervals likesemitones are rare in five-note systems and common in seven-note systems; and this peculiarity has a very marked effectin the music, for those which lend themselves readily to theaddition of semitones have proved the most capable of higherdevelopment. It is unnecessary to speculate on the way inwhich savages gradually built their scales by adding note tonote, as the historical records of Greek music go so far backinto primitive conditions that the actual process of enlarge-ment can be followed up to the state which for ancient daysmust be considered mature. It is tolerably clear that theartistic standard of the music of the Greeks was very farbehind their standard of observation and general intelligencein other matters. They spent much ingenious thought uponthe analysis of their scales, and theorised a good deal uponthe nature of combinations which they did not use; but theiraccount of their music itself is so vague that it is difficult toget any clear idea of what it was really like. And it stillseems possible that a large portion of what has passedinto the domain of " well-authenticated fact" is completemisapprehension, as Greek scholars have not time for athorough study of music up to the standard required to judgesecurely of the matters in question, and musicians as a ruleare not very intimate with Greek. But certain things mayfairly be accepted as trustworthy. Among them is, of course,the enthusiasm with which the Greeks speak of music, andtheir belief in the marvellous power of its effects. The storiesof Orpheus and Amphion and others testify to this beliefstrongly, and mislead modern people into supposing thattheir music was a great art lost, when the very details and

SCALES 23

style of their evidence tend to prove the contrary. It is notin times when art is mature that people are likely to tellstories of overturning town walls or taming savage animalswith i t ; but rather when it is in the elementary stages,in which the personal character of the performer adds somuch to the effect. It is a sufficiently familiar fact that inour own times a performer of genius can move people moreand make more genuine effect upon them with an extremelysimple piece than a brilliant virtuoso of the highest technicalpowers can produce with the utmost elaboration of moderningenuity. A crowd of people of moderate intelligence goalmost out of their minds with delight when a famous singerflatters them with songs which to musicians appear the baldest,emptiest, and most inartistic triviality. The moderns whoare under such a spell cannot tell what it is that moves them,and neither could the Greeks. They would both confess tothe power of music, and the manner of their confession wouldseem to imply that they were very impressionable, but hadnot arrived at any high degree of artistic intelligence orperception. The Greeks, moreover, were much nearer thebeginning of musical things, and may be naturally expectedto have been more under the spell of the individual sympa-thetic magnetism of the performer than even uneducatedmodern people; and the accounts we have of their systemtend to confirm these views. Its limitations are such as donot encourage a belief in high artistic development, for at notime did the scheme extend much beyond what could bereproduced upon the white keys of the pianoforte and anoccasional V>? and Cjf; and all the notes used were comprisedwithin the limits of the low A in the bass stave and the Eat the top of the treble stave. The first records indicate thetime when the relations of three notes only were understood,which stood in much the same relation to one another thatA F E do in our modern system. This clearly does not

g z z ^ n represent the interval of a third with a semi-R tone below it, but the interval of a fourth

looking downwards with F as a downward leading note to E.This was called the tetrachord of Olympos. In time the note

24 THE ART OF MUSIC

between A and F was added, which gave a natural flow downfrom .V to E, This was well recognisedas the first nucleus of the Greek system,

and was called the Doric tetrachord. It was enlarged by thesimple process of adding another group of notes which corre-sponded exactly to the first, such as E, D, C, B, below orabove, thereby making a balance to the other tetrachord. Itis possible that their musical sense developed sufficiently tomake use of the artistic effects which such a balance suggests \and it is even likely that the desire for such effects was theimmediate cause of the enlargement of the scale. In courseof time similar groups of notes, called tetrachords, were addedone after another, till the whole range of sounds which theGreeks considered suitable for use by the human voice wasmapped out. The whole extent of this scale being only fromA in the lower part of the bass stave to A in the treble, indi-cates that the Greeks preferred only to hear the middle portionof the voice, and disliked both the high and low extremes, whichcould only be produced with effort; and it proves also thattheir music could not have been of a passionate or excitablecast, because the use of notes which imply any degree of agita-tion are excluded. The last note which is said to have beenadded in the matter of range was the A below the lowest B,which was attributed to a lyre-player of the name of Phrynisin 456 B.C. But this note was considered to stand outside theset of tetrachords, and was not used in singing, but only toenable the harp-player to execute certain modulations.

The Greek musical system being a purely melodic one, itwas natural that in course of time a characteristic feature ofhigher melodic systems should make its appearance. For thepurposes of harmony but few arrangements of notes are neces-sary ; but for the development of effect in melodic systems itis very important to have scales in which the order of arrange-ment of differing intervals varies. In the earliest Greeknucleus of a scale, the Doric, there was a semitone betweenthe bottom note and the next above it in each tetrachord asbetween B and C, or E and F. In course of time the posi-tions of the semitones were altered to make different scales,

SCALES 2 5

and then the tetrachord stood as B, Cj£, D, E, or, as in ourmodern minor scale, D, E, F, G. This was called the Phrygian,and was considered the second oldest. Another arrangementwith the semitone again shifted, as B, 0$, D$, E, resemblesthe lower part of our modern major scale, and was known asthe " Lydian." When the tetrachords were linked togetherat first they overlapped ; as in the Doric form, if the lowertetrachord was B, C, D, E, the one added above it would beE, F, G, A, the E being common to both tetrachords. Thiswas ultimately found unsatisfactory, and a scheme of tetra-chords which did not overlap was adopted about the time of

Pythagoras. Thus the Doric mode stood a s E F G A B C D E ,the semitones coming between first and second and fifth andsixth ; the Phrygian mode became like a scale played on thewhite notes of the pianoforte beginning on D ; and theLydian like our ordinary major scale; and more were added,such as the ^Eolic, which is like a scale of white notes begin-ning on A ; the Hypolydian, like one beginning on F, andso forth.

The restrictions of melodies to these modes secured a well-marked variety of character, to which the Greeks were keenlyalive \ and they expressed their views of these diversities bothin writing and in practice. The Spartan bo}Ts were exclu-sively taught the Doric mode, because it was considered tobreathe dignity, manliness, and self-dependence ; the Phrygianmode was considered to have been nobly inspiring also, but indifferent ways; and the Lydian, which corresponded to ourmodern major mode, to be voluptuous and orgiastic, probablyfrom the fact that the semitones lay in the upper part ofthe tetrachords, which in" melodic music with a downwardtendency would have a very different aspect from that of ourfamiliar major mode under the influence of harmony. Butthis mode was not in great favour either in ancient times orin mediaeval times, when attempts were made to revive theGreek system.

In this manner a series of the notes which were supposedto be fit for human beings to sing were mapped out into dis-

26 THE ART OF MUSIC

tinct and well-defined positions. But one of the most impor-tant developments of the scale still remained to be made. Inmodern times the scale has become so highly organised thatthe function of each note and the particular office each fulfilsin the design of compositions is fairly well understood evenby people of moderate musical intelligence. What is calledthe tonic, which is the note by which any key is named, isthe most essential note in the scale, and the one on whichevery one instinctively expects a melody or a piece of musicin that key to conclude; for if it stops elsewhere every onefeels that the work is incomplete. To the tonic all othernotes are related in different degrees—the semitone below, asleading to it; the dominant, as the note most strongly con-trasted with it, and so forth. But to judge from the absenceof comment upon such functions of various notes of the scaleby Greek writers, and the obscurity of Aristotle's remarks onthe subject, it must be assumed that the ideas of the Greekson such a head were not clearly developed. In the beginning,when there were only three notes to work with, it seems asif their musical reason for existence necessarily defined theirfunctions. But it is probable, as frequently happens in similarcases outside the range of music, that composers speculatedin arrangements of the notes which ignored the purposeswhich brought them into existence ; and that, as the scalegrew larger and larger, people ceased to recognise that anyparticular note was more important than another. It is truethey had distinct names for every note in a mode, and twoare specially singled out as important, namely, the "middle "note and the "highest," which all modern writers agree waswhat we should call the lowest. If anything can be gatheredfrom the ancient writings on the subject at all, it would seemto be that the middle note, the " mese," was something like ourdominant, and the "hypate," which we should call the lowest,was the note to close upon. If this was so, the original func-tions described on page 20 were still recognised in theory;but the wisest writers on the subject in modern times thinkthat matters got so confused that a Greek musician would endupon any note that suited his humour. This vagueness coin-

SCALES 27

cides with the state of the scales of all other melodic systems;and though the Greeks were more intelligent than any otherpeople that have used a melodic system, it is very likely thatwithout the help of harmony it was almost impossible forthem to organise their scale completely.

The Greeks subjected their scales to various modificationsin the course of history. It was very natural that suchintellectualists as they were should try experiments to enhancethe opportunities of the composer for effect. One experimentwas made very early, which was to add a note like CJJ!, butless than a semitone above the C, which stood next above thelowest note of the old Doric tetrachord; and this was calledthe chromatic genus. Other experiments were tried in sub-dividing into yet smaller intervals; but the various writerswho describe these systems indicate that they were notaltogether successful, as the chromatic genus was regardedas mawkish and insipid, and the enharmonic genus as tooartificial.

The Greek system may therefore be considered to havearrived at its complete maturity in the state in which a rangeof sounds extending only for two octaves was mapped out intoa series of seven modes, which can be fairly imitated on amodern pianoforte by playing the several scales which beginrespectively on E, F, G, A, B, 0, D, without using any ofthe black keys. The difference between one and anotherobviously lies in the way in which the tones and semitonesare grouped, and the device affords a considerable opportunityfor melodic variety. But it appears improbable that theGreeks arrived at any clear perception of the functions of thenotes of the scale after the manner in which we regard ourtonic and dominant: the full development of this phase ofscale-making had to wait till after the attempt to systematiseecclesiastical music on what was supposed to be the ancientGreek basis in the early middle ages; when the newawakening of the sense of harmony soon caused scales to takeentirely new aspects. But this being the highest artificialdevelopment of the scale element of music in connection withharmony must be considered later, as there are many other

2 8 THE ART OF MUSIC

melodic systems like that of the ancient Greeks in principlebut different in their order of arrangement.

In the many and various melodic systems of the world,scales are found of various structure, but the building of all ofthem has evidently been achieved by similar processes. Racesshow their average characteristics in their scales as much asthey do in other departments of human energy and contriv-ance. Such as are gifted with any degree of intellectualactivity have always expended a singular amount of it ontheir scales; and the result has been pedantically minute,or theoretic, or extravagantly fanciful in proportion to theirinclinations in these respects. The Chinese, as might beexpected, have been at once minutely exact in theory andbombastically complacent in fancy. The races of the greatIndian peninsula have been wildly fanciful in their imagery,and equally extravagant in ingenious grouping of notes intomodes; while the Persians and Arabs have been remarkablefor their high development of instinct in threading the difficultand thorny ways of acoustical theory in such a manner as toobtain a very perfect system of intonation. The Persiansystem is probably the most elaborate scale system in theworld. Nothing appears to be known of early Persian music,though the earliest records give examples of scales which arealready very complete, implying a very long period of ante-cedent cultivation of the art. In the tenth century they hadalready developed a scale which has the appearance of beingsingularly complete, as it comprised all the intervals which arecharacteristic of both our major and minor modes, except themajor seventh, which is our upward-tending leading note.That is, it appears as the scale of C with both E flat and Enatural, and both A flat and A natural, but B flat only insteadof our familiar leading note B. This shows that they certainlydid not at that time attempt cadences of the kind so familiarin modern harmonic music, but kept to the forms which weresuitable to a melodic system. They did not, however, longrest satisfied with a scale of such simplicity. By the time ofTamerlane and Bajazet the series of notes had been enlargedby the addition of several more semitones, and had been

SCALES 29

systematised into twelve modes, on the same principle and forthe same purposes of melodic variety as had been the case withthe Greeks. In fact, the first three agree exactly with theancient Ionic, Phrygian, and Mixolydian modes of the Greeks,but go by the very different names of Octrag, Nawa, andBousilik. But even this did not go far enough for the subtleminds of the Persians and Arabians. A famous lute-playeradopted a system of tuning which gave intervals that arequite unknown to our ears; as, for instance, one note whichwould lie between E^ and E, and another between At?- and A,in the scale of C. The former is described as a neutralthird, neither distinctly major nor minor, which probablyhad a pleasant effect in melodic music ; and the latter, as aneutral sixth.

Going still further, they applied mathematical treatment ofa high theoretical kind to the further development of thescale. They evidently discovered the curiously paradoxicalfacts of acoustics which make an ideally perfect scale im-possible, and, to obviate the difficulties which every acousticaltheory of tuning presents, they subdivided the octave into noless than seventeen notes. Their object was not to have sucha large number of notes to make melodies with, or to employquarter tones, but to have a copious variety to select from asalternatives. The arrangement of these notes was quitesystematic, and gave two notes instead of the one familiarsemitone between each degree of the scale and the one nextto it. That is to say, between D and C there would be twonotes, one a shade less than a semitone (making the intervalknown as the Pythagorean limma 243 : 256), and anothera little less than a quarter tone from D (making the intervalknown as the comma of Pythagoras (524288 : 531441). Andsimilar intervals came between D and E, and so on throughthe scale. By this ingenious arrangement they securedabsolutely true fifths and fourths, a major third and a majorsixth that were only about a fiftieth of a semitone (that is,a skisma) short of true third and sixth, and a true minorseventh. Theoretically this is" the most perfect scale everdevised. Whether it really was used exactly in practice is

3O THE ART OF MUSIC

another matter. Even under harmonic conditions, when notesare sounded together, it is impossible for the most experttuners to make absolutely sure of intervals within suchnarrow limits as the fiftieth of a semitone; while it is wellknown that in melodic systems the successions of notes usedby the performers are only approximately true; for the finestear in the world can hardly make sure of a true third or atrue sixth when the notes are only sounded one after theother. In modern times this remarkable system of thePersians has been changed still further, by the adoption oftwenty-four equal quarter tones in the octave. But this planreally lessens the delicate perfection of the adaptability of thesystem; for though it looks a larger choice of notes, it will notgive such absolutely true intervals as the earlier scheme.With all this wonderful ingenuity in dividing off the rangeof sounds for use and defining the units exactly, it appearsthat the Persians and Arabians had but an uncertain senseof what we call a tonic, and, as far as can be gathered, stoppedshort of classifying the notes in accordance with their artisticfunctions, just as the Greeks seem to have done.

In strong contrast to the Persians the inhabitants of thegreat Indian peninsula appear to have sedulously avoidedapplying mathematics to their scales; and though the Indianscales are even more complicated and numerous than thePersian, they have been handed down from generation togeneration for ages, purely by aural tradition. Unfortunatelythis avoidance of mathematics has caused the subject ofIndian scales to be extremely obscure, and the extraordinarilyhigh-flown imagery which is used in Indian treatises on musicrenders the unravelling of their system the more difficult.The method used for arriving at the actual scales used bymusicians is to ascertain the exact length of the subdivisionsof the strings which are indicated by the positions of the fretsupon the lute-like instrument called the vina, which has beenin universal use for many hundreds of years, and to test andcompare the notes which are produced by sounding the stringswhen u stopped " at such points. The frets are supposed tomark the points at which the string should be stopped with

SCALES 31

the finger to get the different notes of the scale ; but inpractice a native player can always modify the pitch bymaking his finger overlap the fret more or less, and therebyregulate the fret to get the interval which tradition taught himto be the right one. In fact the frets on different instrumentsvary to a considerable degree—even the octave is sometimestoo low and sometimes too high; but through examining anumber of specimens a rude average has been obtained, whichseems to indicate a system curiously like the modern Europeansystem of twelve semitones. But it is clear that this can beonly a rough approximate scheme upon which more delicatevariations of relative pitch are to be grafted, for the actualsystem of Indian scales is far too complicated to be providedfor by a mere arrangement of twelve equal semitones.

As in the case of the Persian and Arabic system, theIndian scale does not come within the range of intelligiblerecord till it is tolerably mature and complete from octaveto octave. In order to get a variety of major and minortones and semitones, the scale was in ancient times dividedinto twenty-two small intervals called s'rutis, which were alittle larger than quarter tones. A whole tone containedfour s'rutis, a three-quarter tone three, and a semitone two.By this system a very fair scale was obtained, in which thefourth and fifth were very nearly true, and the sixth high(Pythagorean). In what order the tones and semitones werearranged seems to be doubtful ; and in modern music thesystem of twenty-two s'rutis has disappeared, and a, systemof the most extraordinary complexity has taken its place.The actual series of notes approximates as nearly as possibleto the European arrangement of twelve semitones; and thepeculiarity of the system lies in the way in which it has beendeveloped into modes. The virtue of the system of modeshas already been pointed out, as has the adoption of a fewdiverse ones by the Greeks. The Indians went so far asto devise seventy-two, by grouping the various degrees of thescale differently in respect of their flats and sharps. Thesystem can be made intelligible by a few examples out ofthis enormous number. Our familiar major mode forms

3 2 THE ART OF MUSIC

one of them, and goes by the name of Dehrasan-karabh&rna.Our harmonic minor scale also appears under the name ofKyravani, the Greek modes also make their appearance, andevery other combination which it is possible to get out of thesemitones, but always so that each degree is represented insome way or another. The extremes to which the processleads may be illustrated by the following. Tanarupi corre-sponds to the following succession—

C, T>\>, EW< F , G, A#, B, C.

Gavambodi to

C\ Db, W, Ffc G, At>, Ttob, C

This obviously carries the modal system as far as it can goin the way of variety.

But besides these modes the Indians have developed a furtherprinciple of restriction in the " ragas," which are a numberof formulas regulating the order in which the notes are tosucceed each other. The rule appears to be that when aperformer sings or plays a particular raga he must conformto a particular melodic outline both in ascending and descend-ing. He may play fast or slow, or stop on any note andrepeat it, or vary the rhythm at his pleasure; it even appearsfrom the illustrations given that he may put in ornamentalnotes and little scale passages, and interpolate here and therenotes that do not belong to the system, so long as theessential notes of the tune conform to the rule of progression.—Just as in modern harmonic music certain discords mustbe resolved in a particular way, but several subordinate notesmay be interpolated between the discord and the resolution.—An example may make the system clearer. The formula givenfor the raga called Nada-namakrya is C, Dj?, F, G, A >, C inascending, and C, B, Ab, G, F, E3 Dt?, C in descending. Inpractice it is evident that the performers are not restrictedto the whole plan at once. G may go either to F descendingor to At? ascending, and At? may either go to C or back to G,and so on; but the movement from any given note must bein accordance with the laws of the raga, up or down. The

SCALES 33example of this raga given in Captain Day's Music of SouthernIndia helps to make the system clear.

In the mode of Maya-malavagaula, and the raga Nada-namakr£a.

et cet.