Booklet.Policy Paper 1.Mindanao Energy and...

Transcript of Booklet.Policy Paper 1.Mindanao Energy and...

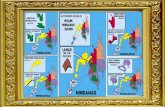

Mindanao Economic Policy Papers 1Energy and Power Situation in Mindanao:Policy Environment and Impactby Ella S. Antonio

Mindanao Economic Policy PapersENERGY and POWER SITUATION in MINDANAOPOLICY ENVIRONMENT and IMPACTS

By Ella S. Antonio President, Brain Trust: Knowledge and Options for Sustainable Development, Inc.

Copyright 2012 by Brain Trust: Knowledge and Options for Sustainable Development, Inc.. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro-duced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information and retrieval system, without permission from the publishers. Inquiries should be ad-dressed to the author c/o Brain Trust Inc., Unit 810 Medical Plaza Building, San Miguel Avenue, Ortigas Center, Pasig City 1605 (E-mail: [email protected]) .

This publication was made possible through the support of AusAID. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily refl ect the views of AusAID.

The Mindanao Economic Policy Papers were prepared as part of the work led by Dr. Cielito F. Habito, AusAID Adviser for Mindanao Economic Development to examine constraints to investment and economic development in Mindanao, especially in Muslim Mind-anao, and determine appropriate ways to address them. Conduct and preparation of the studies were administered by Brain Trust: Knowledge and Options for Sustainable Development Inc., and undertaken between August 2011 and July 2012. Hence, any recent developments and changes subsequent to that period would not be refl ected in the policy papers.

Mindanao Economic Policy Papers

ENERGY and POWER SITUATION in MINDANAOPOLICY ENVIRONMENT and IMPACTS

byElla S. Antonio

A publication of:

Australian Agency for International Development

Edited by Ma. Salve I. Duplito

iv

Table Of Contents

Introduction 1

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation II.1 Energy Sources 2 II.2 Power Capacity and Generation 2 Figure 1: Power Generation in Mindanao 3 Table 1: Mindanao Energy Capacity and Capability by Plant Type 4 Table 2: Comparative Systems Peak Demand, 2010 and 2009 4 Figure 2: Capacity and Gross Power Generation Shares by Source 5 II.3 Power and Energy Mix 5 II.4 Electricity Sales and Consumption 6 Table 3: Sales and Consumption of Electricity in Mindanao 6 II.5 System Loss 7 Figure 3: System Losses, 2005-2009 7 II.6 Power Rates 8 Table 4: Financial Overview of Mindanao Electric Cooperatives 9 Table 5: EC’s Unbundled Average Effective Residential Electricity Rates 11 Table 6: Average Effective Residential Electricity Rates of PDUs 12 Table 7: Items in Unbundled Residential Bill 12 II.7 Electric Cooperatives 13 Box 1: The LASURECO Turn-Around 15 II.8 Renewal Energy and Power Rates 16 Table 8: NREB Proposals on Feed-In Tariffs and Their Impacts 16 Table 9: Comparison of Some Benefits of RE Technologies 18

Energy and Power Sector Projects III.1 Supply and Demand Outlook 20 Figure 4: Mindanao Supply-Demand Outlook, 2010-2030 20 Table 10: List of Committed and Indicative Power Products 21 Table 11: Potential Renewable Energy Projects in Mindanao Regions 23 III.2 Privatization of Agus and Pulangi Facilities 25 III.3 Wholesale Electricity Spot Market 25 III.4 Energy Plan and Policy 25 Figure 5: Philippine Energy Policies 26

Recommendations 26

Chapter I

Chapter II

Chapter III

Chapter IV

1

I. Introduction

The energy and power sector is an important and potent driver for economic and social development. For Mindanao, it also promotes peace by equalizing access to opportunities that uplift people’s lives. Endowed with energy resources like geothermal, oil, natural gas, wind, ocean and water, Mindanao has the greatest potential for attaining self-sufficiency in energy and for becoming a low-carbon society.

If things are done right, Mindanao would be a big beneficiary of the Energy Reform Agenda that the Department of Energy (DOE) and other energy bodies have been implementing with the following objectives: energy security, optimal energy pricing, and a sustainable energy system. The legal, regulatory, policy, fiscal and institutional frameworks are already in place. The challenge is how these are enforced and adapted to Mindanao and in the Mindanawon way.

Energy and power plans, policies, programs and projects are largely prepared and decided upon by the central government in Manila. Mindanao’s roles have been largely confined within the provision and processing of energy resources, generation and distribution of power, and management of the demand and supply situation, all of which are heavily influenced by national policies. There is limited scope for local initiative and decision-making to influence Mindanao’s energy future and outlook.

This policy paper aims to raise important points and provide recommendations that may contribute to the Mindanao energy discourse and enrich the energy action agenda. It hopes to help expand the participation and strengthen the control and influence of Mindanawons in developing and pursuing their own energy agenda.

The energy sector is wide and complex. As stated above, its development frameworks are well in place so the elbowroom for further policy changes is narrow. For this reason, this paper shall focus on the biggest and most critical components of the sector, i.e., resource management, power generation and distribution; and on strengthening the enabling role of the sector to the growth and development of Mindanao. Important aspects of the other components will be touched upon especially as they relate to the focus components.

2 Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

II. Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

II.1 Energy Sources

Mindanao has a very rich and extensive river system that emanates from 256 watersheds, two of which (Agusan and Pulangi) are among the largest in the country. These river systems have provided cheap and renewable resources for power generation and will continue to play this role over the long term. Wind and ocean currents can be harnessed in many places while sunshine is everywhere. Geothermal resources are likewise abundant, making the country the second-largest user in the world. Mindanao produces substantial amounts of agricultural wastes that could feed biomass power plants. All these bode well for a low-carbon future for Mindanao.

Mindanao imports coal even if it is available in the country. It also imports oil products for its power plants and fuel requirements. A key objective is to minimize these importations and use of fossil fuels for energy security and environmental integrity.

In relation to energy self-sufficiency, oil and gas exploration activities in two of the largest oil and gas basins in the country, the Cotabato Basin in Southern Mindanao and the Agusan-Davao Basin in East Central Mindanao, are currently being pursued. The two basins are estimated to have a combined resource potential of 354 million barrels of oil equivalent1. Exxon is exploring two areas covering about 1.9 million hectares in the Sulu Sea while the South Sea Petroleum and Hellios Petroleum and Gas Corp. are exploring the Agusan-Davao Basin.

Meanwhile, the DOE has engaged Japan International Cooperation Agency in studying the feasibility of establishing a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal mainly for generating 300 MW of electric power. This is in line with promoting energy security by providing alternatives to hydropower.

Mindanao has most of the resources necessary for producing fuel and power, and has ready access to those that it does not have. All it needs is to properly manage its energy and power industry with support from the national government in terms of responsive and appropriate policies.

II.2 Power Capacity and Generation

Power generation in Mindanao steadily increased at an average annual growth rate of

1 Presentation of Director Jesus Tamang, 2nd Mindanao Mining Summit, August 11-12, 2011, Davao City.

4.4% from 2001-2010 (Figure 1). This is slightly lower than the 4.5% average growth rate of Mindanao’s gross domestic product from 2001-2009. Given current generating capacity, Mindanao would need more baseload plants2 to serve the needs of its growing economy and population.

In 2009, Mindanao’s total installed capacity was 1,929 MW (Table 1) and this generated 8,235 GWH of power. This capacity increased by 2.2% to 1,970 in 2010 due to the commissioning of the 42 MW Sibulan hydroelectric power plant (HEP) in Davao del Norte. Despite this, dependable capacity declined from 1,696 MW in 2009 to 1,658 MW in 2010 mainly because of the big drop in the use of diesel due to increased oil prices, and improvement in the capability of HEPs to produce power in the latter part of 2010.

Figure 1Power Generation in Mindanao

(in GWh)

Source: Department of Energy

More than half of Mindanao’s electricity requirement is produced by HEPs, and these have been operating below capacity (about 55%) due to massive siltation (Pulangi power plant) and lack of rehabilitation. It was of no surprise, therefore, that when the El Niño Phenomenon peaked and dried up lakes and rivers in summer of 2010, Mindanao experienced its worst power crisis. HEPs were operating far below capacity that their share to total power generation drastically dropped from 51.8% in 2009 to 12.3% in April 2010.

2 Facilities that generate the minimum amount of power necessary to meet minimum demand based on reasonable expectations of customer requirements (Energy Dictionary. www.energyvortex.com.).

Average Annual Growth Rate: 4.4%

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation 3

4.4% from 2001-2010 (Figure 1). This is slightly lower than the 4.5% average growth rate of Mindanao’s gross domestic product from 2001-2009. Given current generating capacity, Mindanao would need more baseload plants2 to serve the needs of its growing economy and population.

In 2009, Mindanao’s total installed capacity was 1,929 MW (Table 1) and this generated 8,235 GWH of power. This capacity increased by 2.2% to 1,970 in 2010 due to the commissioning of the 42 MW Sibulan hydroelectric power plant (HEP) in Davao del Norte. Despite this, dependable capacity declined from 1,696 MW in 2009 to 1,658 MW in 2010 mainly because of the big drop in the use of diesel due to increased oil prices, and improvement in the capability of HEPs to produce power in the latter part of 2010.

Figure 1Power Generation in Mindanao

(in GWh)

Source: Department of Energy

More than half of Mindanao’s electricity requirement is produced by HEPs, and these have been operating below capacity (about 55%) due to massive siltation (Pulangi power plant) and lack of rehabilitation. It was of no surprise, therefore, that when the El Niño Phenomenon peaked and dried up lakes and rivers in summer of 2010, Mindanao experienced its worst power crisis. HEPs were operating far below capacity that their share to total power generation drastically dropped from 51.8% in 2009 to 12.3% in April 2010.

2 Facilities that generate the minimum amount of power necessary to meet minimum demand based on reasonable expectations of customer requirements (Energy Dictionary. www.energyvortex.com.).

Average Annual Growth Rate: 4.4%

4 Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

The average capability then was down to 93 MW such that unserved system peak demand3 reached a record high of 320 MW for the Mindanao grid.

Table 1. Mindanao Energy Capacity and Capability by Plant Type

April 2010 2010 2009

Plant Type Ave. Capability Installed Capacity

Dependable Capacity

Installed Capacity

Dependable Capacity

MW % Share MW %

Share MW % Share MW %

Share MW % Share

Coal 95 12.3 232 11.8 212 12.8 232 12.0 210 12.4

Oil-Based 373 48.4 594 30.2 438 26.4 594 30.8 485 28.6

Geothermal 210 27.2 103 5.2 100 6.0 103 5.3 98 5.8

Hydro 93 12.1 1040 52.8 907 54.7 998 51.8 902 53.2

Solar 1 1 0.05 1 0.06 1 0.05 1 0.06

Total 771 1970 1658 1928 1696Sources: Department of Energy; National Grid Corporation of the Philippines

DOE noted that Mindanao’s electricity demand growth slowed down from an average of 4.4% in the 1990s to 3.3% in 2000-2008 due to the shift from industry-oriented to service-oriented economy; constrained supply; and peace and order problems4. The slow down caused system peak demand to drop 1.2% to 15 MW in 2010 from 2009 (Table 2), in stark contrast with double-digit rise in peak demands for Luzon and Visayas.

Table 2. Comparative System Peak Demand, 2010 and 2009MW %

Grid 2010 2009Change

MW %Luzon 7,656 6,928 728 10.5Visayas 1,431 1,241 190 15.3Mindanao 1,288 1,303 -15 -1.2

Source: DOE, 2010 Philippine Power Sector Situationer

Oil-based power covered the slack created by HEPs, substantially increasing its share to 48.4% in April 2010 (Table 1). As earlier mentioned, increased oil prices and improved rainfall and water level conditions have since brought back hydroelectric power to its preeminent role in Mindanao. Geothermal and coal power also increased their shares as high prices of crude oil led to lower oil-based power generation.

3 Peak demand is the highest demand of energy consumption during a time cycle. It represents the spike in the demand for energy at certain times of day.

4 Power Development Plan, 2009-2030, Department of Energy

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation 5

As of the first semester of 2011, the share of hydroelectric power (56%) has even exceeded those in the past years due to increased rainfall and full operation of Sibulan HEP (Figure 2). While this has normalized power supply for now, it does not address power security in Mindanao considering expectations of more dry spells to come resulting from climate change.

Figure 2Capacity and Gross Power Generation Shares By Source

as of 1st Semester 2011

Installed Capacity Gross Power Generation

II.3 Power and Energy Mix

There have been conscious efforts to diversify Mindanao’s energy sources but these have led to more intensified use of fossil fuels. Ten years ago, 83% of Mindanao power was generated from renewable energy sources, mainly hydro. There was no coal power plant and oil-based plants accounted for only 17% of generated power. Mindanao also did not have solar power-generating capability. The power generation structure changed when Cagayan Electric Power and Light Company (CEPALCO) operated a 1 MW photovoltaic power plant in Cagayan de Oro in 2005, and STEAG State Power, Inc. commissioned Mindanao Coal 1 and Mindanao Coal 11 in PHIVIDEC, Misamis Oriental in 2006. Since then, coal has become a significant contributor to the grid, accounting for 12.4% in 2009 and rising further to 18% in 2011. At the height of the power crisis, coal’s contribution became very significant at 27.2% as hydropower plants failed to reach their capacities. Oil’s share has remained within the 17%-18% level except during the 2010 power crisis.

Diversification is necessary to attain energy and power security but the optimum mix must be reached with due consideration of various risk factors related to each energy source. Hydropower is most vulnerable to climate change impacts and dependent on healthy watersheds. Oil/diesel prices are volatile and the demand-supply situation is deteriorating due to political events and the foreseen oil peak in the Middle East. Coal is challenged

6 Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

for environmental and supply reasons. Geothermal resources are not adequate to meet demand and also face environmental challenges. Renewable energy development in general is beset by technology and pricing issues.

Notwithstanding all these, diversification must veer towards increased use of clean, renewable and indigenous sources of power to attain energy security and promote a sustainable future. Mindanao’s reliance on coal and oil has risen in recent years, and plans are afoot to establish more of such plants in the near future because the efficiency of HEPs have gone down especially in summertime and economic feasibility and tariff issues have yet to be addressed on the use of renewable power such as biomass, wind and solar.

II.4 Electricity Sales and Consumption

Electricity sales grew at an average rate of 3.3% annually in the period 2003-2009 (Table 3). Of the 8,235 GWH generated in 2009, 6,699 GWH were sold and the rest (1,536) were lost in the systems and consumed by the service providers. From 2003-2009, the public consumed on average 27.4% of total generated power. Consumption of commercial establishments grew fastest at 6.4%. The industrial sector has always been the biggest consumer (39.2%) but its consumption (0.7% average annual growth) has been lackluster during the period. Composite consumption was growing at an average rate of 4.0%, which indicates some robustness in the Mindanao economy.

Table 3. Sales and Consumption of Electricity in Mindanao

Sector

Consumption(GWH)

Ave. Annual Distribution (%)

Ave. Annual Growth Rate (%)

2009 2003-2009 2003-2009

Residential 2,362 27.4 4.9

Commercial 1,143 12.5 6.4

Industrial 2,778 39.2 0.7

Others 417 4.5 10.7

Total Sales 6,699 83.6 3.3

Own-Use 293 2.7 21.3

System Loss 1,243 13.8 6.1

Total Consumption 8,235 100.0 4.0Source: Department of Energy

In its 2010 Power Sector Situationer, DOE indicated that residential sales for Mindanao increased by 3.5%. While a clear slow down from its average level of 4.9%, the growth is significant given the power crisis that seriously affected the population that year. DOE further said that electricity sales to the commercial sector in 2010 increased by 10.7% from

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation 7

2009. This is a clear sign that commercial business coped well, even expanded despite the crisis.

II.5 System Loss

Worth noting by the consuming public is system loss5 as this has been accounting for 13.8% of annual average consumption and increasing rapidly by an average 6.1% rate annually. In 2009, system loss dramatically increased 16.6% from that of 2008 (Figure 3). While the losses are still within the caps of 9.5% for private distribution utilities (PDU) and 14% for electric cooperatives (EC) set under the Anti-Pilferage of Electricity and Theft of Electric Transmission Lines/Materials Act of 1994 (RA 7832) for the period, these still translate to higher electricity bills .

Own-use electricity, also referred to as administrative loss, is sometimes lumped with systems loss. Its share in total consumption in 2009 reached 4.4% and has been growing at a rate of 18.3% annually. These are alarming trends considering that power has become an expensive and critical commodity in Mindanao. The costs of losses and own-use are automatically passed on to electricity consumers, contributing further to eroding business profi tability and increasing burdens to meager household budgets. The legal provision inadvertently allows systemic ineffi ciencies and complacency.

Figure 3System Losses, 2005-2009

Source: Department of Energy

5 Systems Losses consist of (a) electricity that escapes as heat from distribution lines and transformers (technical loss); and (b) electricity lost to theft or pilferage (non-technical loss).

8 Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

In 2008, the Energy Regulatory Commission (ERC)6 lowered the maximum rate of system loss (technical and non-technical) that may be charged to consumers, to 8.5% of total KWH purchased and generated for PDU and 13% for ECs effective 2010. It prescribed that administrative loss be treated as an operation and maintenance expense of utilities.

In 2010, the National Electrification Administration7 (NEA) reported that the national average system losses of ECs went below the 13% cap to 12.3% 8. It was the lowest level attained by the ECs since the passing of the Electricity Industry Reform Act (EPIRA) in 2001. NEA informed that the 0.7% difference between the cap and the actual system loss is equivalent to a savings of P561.6 million for EC consumers. Lowering system losses can substantially benefit power consumers in terms of lower electricity prices.

Within Mindanao, system losses of all ECs averaged 12.9%, a percentage point lower than the cap (Table 4). However, a closer look at individual system loss shows that 15 of 33 ECs breached the 13% cap in 2010; and that ARMM ECs have the highest and most significant system losses in the country. Maguindanao recorded the highest loss at 47% followed by Sulu (29.5%), Tawi-Tawi (24.3%), Basilan (24%), and Lanao Sur (18.3%).

All these made Mindanao the worst performer with 12.9% loss compared to Luzon (12.4%) and Visayas (11.5%). It should be noted that four Mindanao ECs had system losses equal to or lower than 6% and 14 more were able to go below the cap. These are indicators that there is ample room for lowering system losses and the cap is ripe for downward adjustment.

As ARMM provinces are the country’s poorest, the high systems losses, which translate to higher electricity prices and reduced supply, only serve to further worsen poverty. Also for reasons of poverty vis-à-vis high electricity costs, pilferage or illegal tapping is observed to be more rampant in these areas, thus further increasing systems losses. A deliberate and sustained effort to address the system loss problem is definitely worth undertaking.

II.6 Power Rates

The power crisis in 2010 increased the shares of power generated from imported fuel. Still, Mindanao’s electricity prices have remained lowest in the country (Tables 5 and 6). This is largely because Mindanao’s major source of energy is low-cost and indigenous. In addition, the government has been subsidizing power generation in Mindanao since EPIRA postponed the privatization of NPC plants (Agus and Pulangi) to 2011.

6 Through ERC Resolution No. 17, Series of 2008 adopting a new system loss cap for distribution utilities.

7 Mandated to strengthen the technical capability and financial viability of the rural ECs them to operate and compete in deregulated electricity market.

8 NEA Media Release, 20 April 2011

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation 9

In a recent speech, President Benigno Aquino III9 noted: “This produced a situation where we kept on selling electricity at about P3.00 when the actual charge of generation was P5.00. That, of course, is contributory to the debt that is now inherited by PSALM and the number is daunting. It is P1 trillion.”

Table 4. Financial Overview of Mindanao Electric CooperativesAs of December 31, 2010

No. Electric Cooperative

TotalOperating Revenue(PMillion)

Net Margin (Loss) after

Reinvestment (P Million)

Power Purchased/Generated

(GWH)

Own Use

(MWH)

System Loss(%)

CollectionEfficiency

(%)

Power Rate

(P/kwh)

Region IX

1 Zamboanga Norte 741 (82.3) 149 - 14.4 94 4.29

2 Zamboangal Sur I 866 24.0 154 - 12.0 101 4.23

3 Zamboanga Sur II 526 4.3 94 - 13.9 95 4.29

4 Zamboanga City 2,248 (89.1) 489 - 17.5 96 4.10

4 Total 4,381 (143.1) 886 15.6 4.17

Region X

5 Misamis Occ. I 272 (3.9) 43 233 12.3 96 4.33

6 Misamis Occ Ii 622 28.1 118 353 10.9 95 4.15

7 Misamis Or I 606 10.0 114 731 6.0 103 3.83

8 Misamis Or. II 478 0.5 88 - 11.8 98 4.15

9 Bukidnon I 723 (0.2) 128 641 10.5 96 4.38

10 Bukidnon II 575 10.1 106 140 12.8 95 4.17

11 Camiguin 108 (7.0) 16 83 13.8 101 5.04

12 Lanao Norte 383 13.3 62 462 9.8 106 4.36

8 Total 3,768 51.1 676 2,643 10.5 4.19

Region XI

13 Davao Oriental 486 23.0 86 215 10.6 95 4.11

14 Davao Del Norte 1,846 25.5 370 668 14.4 95 4.21

9 At the joint Philippine Economic Briefing and Regional Development Council meeting in Cagayan de Oro City on March 23, 2011; http://rtvm.gov.ph -(Speech) Philippine Economic Briefing

10 Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

No. Electric Cooperative

TotalOperating Revenue(PMillion)

Net Margin (Loss) after

Reinvestment (P Million)

Power Purchased/Generated

(GWH)

Own Use

(MWH)

System Loss(%)

CollectionEfficiency

(%)

Power Rate

(P/kwh)

15 Davao Del Sur 1,048 50.3 189 1,202 5.9 95 4.44

3 Total 3,380 98.7 646 2,085 11.4 4.26

Region XII

16 North Cotabato 764 (22.4) 149 491 14.0 94 4.06

17 South Cotabato I 829 0.3 162 - 11.6 99 4.09

18 South Cotabato II 2,733 48.6 598 - 13.1 98 4.08

19 Sultan Kudarat 663 25.5 120 - 13.3 95 4.34

4 Total 4,988 52.0 1,029 491 13.0 4.11

Region XIII

20 Agusan Del Norte 1,388 3.0 283 14.0 97 4.02

21 Agusan del Sur 527 (24.8) 94 13.3 96 4.54

22 Surigao del Norte 593 8.2 128 12.6 101 3.76

23 Siargao 85 4.5 11 17 5.8 100 4.53

24 Dinagat 57 1.9 8 56 5.2 99 4.60

25 Surigao del Sur 1 252 1.9 44 12.7 97 4.38

26 Surigao del Sur 2 323 (1.0) 55 113 11.1 98 4.05

7 Total 3,226 (6.2) 623 186 13.0 4.09

ARMM (Under Close Monitoring)

27 Tawi-Tawi 106 (65.2) 17 62 24.3 48 7.85

28 Siasi Island 15 (0.2) 2 14 8.9 84 5.54

29 Sulu 213 (104.7) 37 333 29.5 39 4.62

30 Basilan 175 (27.1) 32 - 24.0 66 4.98

31 Cagayan de Sulu - - - - - - -

32 Lanao Sur 684 (161.3) 137 176 18.3 19 4.66

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation 11

No. Electric Cooperative

TotalOperating Revenue(PMillion)

Net Margin (Loss) after

Reinvestment (P Million)

Power Purchased/Generated

(GWH)

Own Use

(MWH)

System Loss(%)

CollectionEfficiency

(%)

Power Rate

(P/kwh)

33 Maguindanao 151 (101.6) 43 291 47.0 51 5.09

7 Total 1,344 (460.2) 269 876

33 MINDANAO 19,745 52.4 3.859 5,404 12.9

31 VISAYAS 20,791 294.8 3,362 6,990 11.5 98 4.96

55 LUZON 37,370 115.9 5,710 12,575 12.4 94 5.41

(9) UNDER CLOSE MONITORING* 3,517 (1,351.7) 670 1,702 22.7 4.9

(10) UNDER CDA** 6,154 54.2 969 3,460 14.4

119 NATIONAL 87,576 (834.5) 14,569 30,132 13.0

*Seven of 9 ECs under close monitoring are in ARMM. Figures still include those of the 7 ECs even if these were presented sparately.

**These include 9 ECs from Luzon and 1 EC from Visayas. The data for these are included in this category, i.e. not reflected in Luzon and Visayas totals.

Source: National Electrification Administration website (http://www.nea.gov.ph/)

Table 5. EC’s Unbundled Average Effective Residential Electricity Rates, March 2011

Bill Sub-group

Luzon Visayas Mindanao National

P/Kwh % Share P/Kwh %

Share P/Kwh % Share P/Kwh %

ShareGeneration 4.7482 48.0 3.8955 45.3 2.5084 36.4 3.7174 43.9Transmission 1.2545 12.7 1.2149 14.1 1.5235 22.1 1.3310 15.7System Loss 0.8977 9.1 0.7017 8.2 0.5775 8.4 0.7256 8.6Distribution* 2.1758 22.0 2.2002 25.6 1.9052 27.6 2.0937 24.8Subsidies 0.0853 0.9 0.0940 1.1 0.0665 1.0 0.0819 1.0Taxes 0.7354 7.4 0.4845 5.6 0.3094 4.5 0.5098 6.0Total 9.8970 100.0 8.5908 100.0 6.8904 100.0 8.4595 100.0*Includes Distribution, Supply and Metering Charges

Source: 18th EPIRA Implementation Status report, DOE

Table 6 shows that the average effective electricity rates of CEPALCO are highest for residential users; of Cotabato Light and Power Company (COLIGHT) for commercial users; and for Iligan Light and Power, Inc. (ILPI) for industrial users. On average, however, CEPALCO has the highest rate and ILPI the lowest. Rates of Davao Light are fairly even. The

12 Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

variations in rates could be due to differences in energy mix (e.g. CEPALCO also generates solar power), efficiency levels, operation sizes, etc.

The electricity rate setting was designed by EPIRA and established by the ERC. It consists of costs/charges, contributions and taxes that are defined in Table 7. Many are contesting these items especially those of universal charge and system loss, particularly in Luzon where rates have surpassed those in the Asian region. A current raging issue in the area of rate setting is the impact of renewable energy use, which is discussed in Section II.7.

Table 6. Average Effective Residential Electricity Rates of PDUs, March 2011

End User CEPALCO COLIGHT ILPI DALIGHT*

Residential 7.1464 5.9505 5.5016 6.7587

Commercial 6.7454 6.4360 5.6989 6.6331

Industrial 5.5174 5.3907 7.3903 6.2008

Average 6.2686 5.7763 5.5778 6.4563

*June 2010 data hence not comparable with rates of other PDUs.Source: 17th and 18th EPIRA Implementation Status Reports, DOE

1. The basis for rate setting for both traditional and renewable energy is to provide the utilities the ability to recover just and reasonable costs and earn a reasonable return. What is just and reasonable to both the utilities and the consumers is determined solely by ERC, though in consultation with stakeholders. The determination process, however, is based on a set of data and parameters that the public does not have access to. While there are a few NGOs that try to guard and protect public interests, they do not have enough resources to do the work intensively and persistently. In contrast, utility companies have the capability to analyze data and defend their petitions to ERC on a sustained basis. This uneven playing field must be addressed through access to information, open deliberations (i.e. media coverage of public hearings), and assistance to the public’s representatives, like NGOs, to play the watchdog role.

Table 7. Items in Unbundled Residential Bill

Charges Definition

Generation Cost of power generated and sold to the DU by the NPC as well as the IPPs.

Transmission Regulated cost of building, operating and maintaining the distribution system

System Loss Recovery of cost of power lost due to technical and non- technical factors (currently 8.5% for PUs and 13% for Ecs, including company used power

Retail Customer

Metering System Cost of metering, its reading, operation and maintenance of power metering facilities.

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation 13

Supply Cost of service to customers, such as, billing, collection, customer assistance, etc.

Lifeline Rate Subsidy Subsidized rate given to marginalized/low-income captive market end-users who cannot afford to pay full cost

Interclass SubsidyReduction in the bill of subsidized customer classes, specifically residential, small industrial, government hospitals and streetlight services, and an upward adjustment in the bill of subsidizing customer class.

Power Act Reduction P0.30/kWh reduction in electric bill of residential customers as mandated under R.A. No. 9136.

Currency Exchange Rate Act Adjustments due to fluctuations in the Philippine peso-US dollar exchange rate.

Franchise Tax to national and local governments

Taxes paid by private utility companies: 2% of gross revenues goes to the national government, while a range of .05% up to .75% of gross revenues goes to local government units.

Universal Charge

A non-bypassable charge that is passed on to all end-users monthly for the recovery of stranded debts, stranded contract costs of NPC, and other mandated purposes. It also includes a) Missionary charge for the provision of basic electricity service in unviable areas; b) Environment Fund or the charge of P0.0025/kWh for the rehabilitation and management of watershed areas.

Source: Energy Regulatory Commission

There are sentiments that the government puts too much premium on attracting investments and protecting utilities. Apart from assured recovery of costs and reasonable returns, producers and distributors enjoy very generous incentive packages. As these incentives mean foregone revenues for government, the public is, in affect, hit again by constrained service from government.

II.7 Electric Cooperatives

Power distribution has its own set of issues that merit closer examination. This sub-sector consists of four PUs (CEPALCO, COLIGHT, DALIGHT and ILPI) and 33 ECs in Mindanao. The 33 ECs accounted for 3,859 GWh or about 46% of power sold in 2010 (Table 4). This section focuses on these ECs, particularly on ARMM ECs, since these face bigger issues and challenges that strongly impact on Mindanao’s poor.

Table 4 indicates that 14 ECs registered income losses in 2010. The biggest losses were incurred by all six operating ECs in ARMM (the seventh, Cagayan de Sulu has not been operating). NEA put all seven ECs “under close monitoring” category, along with Pampanga III and Albay. The losses of ARMM ECs reached P460.2 million in 2010, but overall, Mindanao’s net margin remained positive, albeit still the lowest among the three major island groups. Mindanao’s good performers led by Davao del Sur, Misamis Occidental II, Davao Oriental, and Zamboanga del Sur 1 evened out the losses of ARMM ECs.

14 Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

Income losses among ARMM ECs have been largely due to mismanagement as demonstrated by high systems losses and substantially low collection efficiency. The latter ranged from a very low 19% (Lanao Sur) to 84% (Siasi Island), which is high but still unacceptable when compared with collection efficiencies of 95-106% of most ECs. An Asian Development Bank Study10 attributed poor collection to low household income; remoteness of some households; and insufficient personnel to conduct house-to-house collection.

One half (16) of Mindanao ECs are small, i.e. selling less than 100GWh. Valderrama and Bautista11 indicated that the usual issues of small enterprises such as lack of access to financing; poor management; and susceptibility to local political pressures to expand in low-density areas can render them inefficient. They concluded that efficiency of ECs rises with size.

Valderrama and Baustista also see the “cash reimbursement basis” policy for ECs as the main factor for the poor financial situation of many ECs. Under this policy, ECs are given rates that are sufficient to cover operational costs and other requirements such that customers are only required to contribute token amounts as their “equity”. As such, they do not have adequate stake in the EC and enough profit incentive to help keep the EC financially and institutionally sound and robust.

ARMM ECs have more complex issues beyond those stated above. For instance, LASURECO (Lanao del Sur Electric Cooperative) was faced by a host of issues not the least of which is the outright refusal of consumers to pay, invoking their ownership of Lake Lanao and their right to the benefits from its water resources for free. While the financial and operational conditions of LASURECO have substantially improved (see Box), this issue of resource ownership needs to be recognized and addressed.

Policymakers must also look into the cultural aspect of governance. There is a basic inconsistency between the principle of “cooperativism” (joint ownership and democratically governed) as applied to electric cooperatives and the culture of “datuism” (one-man rule, ownership and control) in Muslim Mindanao culture. This inconsistency is an inherent factor that undermines the success of ECs in ARMM. For example, it is common for mayors in ARMM to assume responsibility for the power bills of their constituents and assure them of “free” electricity, but subsequently fail to settle their liabilities with the EC.

EPIRA provided the rehabilitation and recovery support mechanisms for ECs but these did not work for many ECs. The performance and situation of some, especially ARMM ECs, worsened. A more in-depth review of ARMM ECs and their experiences under the EPIRA regime would be instructive to determine how they may be assisted to enable them to

10 Philippines: Rural Electric Cooperatives Development, ADB Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report; May 2009

11 Helena Agnes S. Valderrama and Carlos C. Bautista, Efficiency Analysis of Electric Cooperatives in the Philippines, September 2009

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation 15

play their rightful role in ARMM’s development. The Asian Development Bank is providing a loan to NEA for the “Rural Electric Cooperative Development Project”, which is designed to reduce systems losses and cost of supply of electricity by ECs in the Philippines through a loan facility for selected ECs to undertake upgrading and rehabilitation of distribution lines; acquire the sub-transmission assets of the National Transmission Corporation (TRANSCO); and undertake capacity building of NEA and the ECs. Unfortunately, the project only involves 10 better-performing ECs, hence does not cover ARMM ECs.

Box 1. The LASURECO Turn-Around Barely four years ago, LASURECO had essentially collapsed. Its debt rose to P3.8 billion but its collection efficiency was virtually non-existent at 8%. Its systems loss was remarkably high at 63%. Release of power bills took four months and only Marawi City and one of 40 municipalities were billed. All funds, including those externally provided for special purposes (e.g. 34 barangay electrification projects), were unaccounted for. Employee salaries, benefits and retirement were not paid; the office, vehicles and equipment were all dilapidated; and its property was occupied by private houses of its officials. LASURECO was an epitome of gross mismanagement and systemic corruption. In November 28, 2007, NEA brought in Sultan Ashary Maongco to rehabilitate LASURECO. Since then, the turn around has been phenomenal, aptly described by NEA as 360 degrees. Collection efficiency jumped to 36% and system loss dropped to 18%. Electric services to those who do not pay were severed regardless of kinship or position in society. New and computerized systems were established. Sultan Maongco targets a collection efficiency of 80%-85% and a single digit system loss next year. The Maongco administration has already remitted over P102 million for LASURECO’s debts compared to the P1.1 million paid by the previous administration in the same number of years. Power supply has been stable with system capacity at 90.5 MVA, a three-fold increased from 30 MVA. Salaries and benefits are now paid on time and employee professionalism and morale have been high. Office standards, procedures and atmosphere were improved and professionalized; the property was rid of private houses; and the whole environment was made welcoming and pleasant. All these reforms were funded through internally generated funds and loans. Banks now readily grant loans to LASURECO, a clear recognition of its financial responsibility and trustworthiness. LASURECO has received numerous awards and citations that recognize its herculean efforts and outstanding accomplishments. LASURECO’s turn-around formula was simple: visionary and exemplary governance.

Source: LASURECO Accomplishment Report, 2008-2010 and Meeting with GM Maongco

It is likely that ARMM ECs have peculiar needs that past bailout and rehabilitation efforts failed to address. The cultural aspect of governance cited above appears to be a major factor that requires attention and a creative approach. Achieving self-sufficiency and self-sustainability for the ARMM ECs will require capacity building in areas of planning, management, financial programming, etc. But as the experience of LASURECO

16 Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

demonstrates, having the right kind of leadership for these firms is critical. Meanwhile, the sentiment among Lanao Sur residents that they own Lanao Lake and its waters, and are thus entitled to the benefits therefrom, will remain a basis for reluctance and even refusal to pay for electricity consumption. While the sentiment has basis, a creative approach to address this while keeping ECs financially viable must be found. As a natural resource from which wider society derives major benefits, use of water resources deserves some form of return for the community, similar to the royalty payments made in mining, that must accrue to its stewards and pay for its own protection and sustainability. Such is the basis of the plan of Bukidnon stakeholders to request NGCP to allocate 25% of Pulangi’s power output to the province as the source of water and host of the facility. There is need to develop a clear policy framework on payment for use of water resources, identifying legitimate recipients of payments, and establishing appropriate uses for said payments. This would form part of the recommended policy on payments for ecological services (PES) espoused in the Mindanao 2020 Peace and Development Framework Plan 2011-2030.

II.8 Renewable Energy and Power Rates

Developing renewable energy finds wide support as it will clearly benefit the country. However, the manner by which this would be pursued is under question in view of its possible adverse implications on the country’s energy architecture, especially on power rates. The biggest area of debate has been the feed-in tariffs (FIT)12 for the five RE technologies (solar, wind, ocean, run-of-river hydropower, biomass ). The FIT is expected to pull up power rates, which are already very high. There are numerous sub-issues to these, but this paper focuses on the two most related and contentious ones: tariff setting and pacing of RE projects.

As provided in the Renewable Energy Act of 2008 (RE-ACT), the National Renewable Energy Board (NREB) proposed feed-in tariffs (FIT) for the five technologies (Table 8) to the ERC for approval. NREB also proposed initial installation targets that each technology should achieve within three years as a parameter for the review and possible adjustment of FIT by ERC. The proposed differences in installation targets are meant to minimize the relative impact of investments in each technology on power rates.

Table 8. NREB Proposals on Feed-In Tariffs and Their Impacts

RE Technology FIT Rate(P/kwh)

Installation Target(MW)

Rate Impact(P/kwh)

Degression Rate(from effectivity of FIT)

Solar 17.95 100 0.0140 6% after year 1

Ocean 17.65 10 0.0050 Zero

Wind 10.37 200 0.0340 0.5% after year 2

Biomass 7.00 250 0.0412 0.5% after year 2

12 FIT is a guaranteed fixed rate payment for emerging renewable energy sources per kilowatt-hour to encourage investments in the emerging renewable energy technologies.

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation 17

River Hydro 6.15 250 0.0135 0.5% after year 2

Total 0.1050

*During the review period of three yearsSource: NREB Petition to the Energy Regulatory Commission

Solar has the highest FIT of P17.95/Kwh because of its high initial investment requirement but low capacity factor of 16%, hence installation capacity was limited to 100 MW. Ocean technology comes next at P17.65/Kwh because it also requires substantial initial investment (US$10,000/KW compared to US$2,000/KW for fossil fuel power plant of same size). The installation target is 10 MW for a sole facility in Subic, Zambales. The FITs of River hydro (P6.15/Kwh) and biomass (P7.00/Kwh) are quite low compared to others because they are the cheapest to establish, have high capacity factors and more widely applicable so installation capacities were set high at 250 MW each. Wind is also a very good alternative but its initial investment is made high by the need to import most of its equipment requirements.

Under the FIT scheme, producers are assured of priority access to the grid and reasonable margins over the long-term (minimum of 12 years). In essence, the consumers will subsidize RE producers and the further development of the technologies that they would use. This subsidy is on top of the Lifeline Rate and Inter-class subsidies, and User Charges (see definitions in Table 7) that consumers have been shouldering under EPIRA. In addition, RE-Act grants a very attractive fiscal and non-fiscal incentives package to RE investors.

Table 8 shows that at the proposed FIT rates and capacity levels, the overall impact on electricity rate could be 10.5 centavos per Kwh. Oppositors see this as high and unacceptable under current electricity rates as it would mean additional burden to the poor and would further compromise the already low competitiveness of the economy. Since FIT ensures returns for RE producers, the more vocal critic, the Foundation for Economic Freedom (FEF) opposes the scheme as it is tantamount to “subsidizing these rich solar and energy producers at the expense of Philippine industry and the Filipino consumer.” FEF argues that “It is the obligation of rich, developed countries which are major contributors to carbon emission to subsidize these renewable sources of energy, not of the Filipino consumers.”

On the other hand, government and supporters of RE believe that the price impact is reasonable considering costs (e.g. importation costs, extensive use of water in coal and geothermal plants, carbon emissions) that may be avoided by replacing imported fossil fuel (see Table 9), and a small amount to pay for ensuring the country’s energy security (world oil production was seen to have already peaked in 200513), attaining energy self-sufficiency, and reducing environmental degradation. It also believes that RE plants may also offset the price impact as it can generate substantial benefits in the form of fees and taxes (Table 9), employment, pioneering ancillary industries, built up highly demanded skills, etc. Nonetheless, the proponents of FIT would welcome downward adjustments in

13 Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas (ASPO); www.aspoireland.org.

18 Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation

the rates if these would not compromise the purposes for which these were drawn.

Table 9. Comparison of Some Benefits of RE Technologies

Technology (Installation

Target)

Genera-tion

CapacityFactor

Displaced Fossil Fuel

Avoided GHG

Emissions**

Nat’l & Local Government

Benefits**MW KWH % Barrels/yr US$M/yr* MT CO2 Pmillion

River Hydro (250) 1,073 43-90 659,000 65.9 590,000 520Biomass (250) 1,577 70-75 969,000 96.9 867,000 460Wind (220) 481 25 295,000 29.5 265,000 366Solar (100) 139.3 16 85,400 8.5 67,000 201Ocean (10) 85 52,000 5.2 47,000 120

Total 3,355 2,060,400 206 1,836,00 1,667* At US$100/barrel**Within the 3-year review period

Source: NREB Petition to the Energy Regulatory Commission

Timing or pacing of application of RE technologies is being examined in relation to subsidies guaranteed by RE-Act. Critics believe that with rapid technology development, the costs of RE technologies would soon come down. The cost of establishing a solar facility already fell by about 30% in the last couple of years and this may fall further in the near future. FEF argues that “it is more prudent to wait, given advances in technology, until the costs of solar and wind power drops to parity with conventional sources.”

The government asserts that timing has been mandated in the RE-Act. It believes, however, that timing and room for adjustments are factored into NREB’s FIT petition in the form of the 3-year review period for installation capacity, and “degression”; as well as in the fact that development and establishment of most (except solar) RE facilities would take three to four years.

It is generally expected that RE technologies would mature in a few years, leading towards lower initial investment and generation costs. The NREB petition, therefore, proposes the degression of the FIT until such time that generation costs approximate market prices. The petition includes a set of “degression rates” (Table 8), expressed as percentages of the FITs, that account for the diminishing premium that may be paid for electricity generated from each of the emerging renewable energy sources. The degression scheme (a) hopes to encourage investments at the initial stage and hasten deployment of power plants using renewable energy resources; (b) seeks to reflect differences in the costs of investments and production of various RE technologies; (c) assures that the FIT is reflective of the actual generation cost; and (d) avoids windfall revenues for developers and the passing on of unreasonable costs to consumers.

Public discussions have so far focused more on large investments that would provide electric power to the public, and less on the potentials for harnessing people’s own

Mindanao Energy and Power Industry Structure and Situation 19

initiatives to generate electric power for their own use, a possible alternative to addressing power supply problems while attaining the RE objectives. There are successful community initiatives, usually assisted by local governments and NGOs14, on the generation of RE for consumers’ benefit. Many of these only require some support to address inherent development constraints and to upscale for wider reach. A closer look at these initiatives would be warranted. These initiatives may provide useful lessons that could help in the formulation or fine-tuning of tariff setting and implementing other provisions of RE-Act.

Harnessing people power in the above manner is at the core of House Bill 5405 or the “One Million Solar Rooftops Act” that was recently filed by Party List Representative Teddy Casiño. The bill aims to promote the use of solar power systems in homes and business establishments by (a) mandating the government to provide financing packages and fiscal incentives; and (b) requiring distribution utilities to allow small solar power users to feed excess power into the system and get paid.15. Initiatives that tap the direct and voluntary participation of ordinary people who can afford it must be seriously considered.

What do all these imply for Mindanao, which has the thinnest power reserves and whose energy situation is most vulnerable to climate change impacts? Two imperatives are implied: raise power supply capacity quickly and moderate the dominant dependence on hydropower. On the first, the RE technology options are available but the FIT issue is delaying actual investments. Should the delay persist and a situation similar to what prevailed in the summer of 2010 becomes imminent, the quickest option would be solar power. The urgency of the situation could eventually warrant the relaxation of the cap on installed capacity for solar to meet the supply needs of Mindanao. This scenario would drastically increase electricity rates, which could lead to an indefinite postponement of the sale of Agus and Pulangi to avoid further exacerbating the rate increase. However, this would also maintain the debilitating subsidy to NPC plants by all consumers, including in Luzon and Visayas. Such scenario must not be allowed to happen and efforts to speed up the approval of the FIT mechanism and installation of new (preferably RE) capacities must be pursued.

On the second point, Mindanao must prioritize the establishment of a biomass power plant to maintain its low power cost but moderate the dependence on hydropower. With agriculture being its largest production sector, agriculture waste may be tapped to run a biomass power plant. The value chain for this plant needs to be analyzed and strengthened with the help and cooperation of big agricultural and industrial producers.

For Mindanao islands, solar or wind power facilities may prove to be cheaper or better alternatives to oil-based power facilities/barges, the cost of which reaches up to P25/kwh. ECs serving these areas must be assisted and enabled to establish and manage the necessary solar or wind power facilities. This must be done along with the revamp and

14 Alternative Indigenous Development Foundation Inc.; Sibat (Sibol ng Agham at Teknolohiya)

15 HB 5405 filed on October 11, 2011 and Sun Star (Manila); October 11, 2012; http://www.sunstar.com.ph/manila

20 Energy and Power Sector Prospects

rehabilitation of existing ECs, which are all in financial disarray. Where necessary, assistance may be provided in the establishment of another institutional mechanism (e.g., community association) to manage the facility. In addition to this and wherever technically feasible, small-scale biomass power facilities must also be encouraged.

III. Energy and Power Sector Prospects

III.1 Supply and Demand Outlook

DOE sees power peak demand increasing by an average of 4.6% annually to reach 2.2 GW in 2020 and 3.5 GW in 2030 (Figure 4). To meet and sustain this demand and avert another power crisis, at least 1,000 MW new capacities must be installed in the next 10 years and still another 1,500 MW from 2021-2030. So far, about 12 power projects with a combined capacity of 645 MW have been in the drawing board to meet the 450MW capacity requirement by 2014 (Table 10). Six of these are RE projects, hence these have been awaiting decisions on FITs and other attendant policies for their actual implementation.

Figure 4: Mindanao Supply-Demand Outlook, 2010-2030

Source: Power Development Plan, 2009-2030, DOE

All in all, about 60 projects that could add some 2,700 MW are being eyed for the next 20 years (Table 10). Except for indicated committed projects, the list is highly indicative and very fluid because these are dependent on the resolution of a number of issues, foremost of which is the FIT for RE. Should the RE issue be resolved soon, it is expected that RE share in Mindanao’s energy mix will substantially increase since majority of listed projects, are RE-based. DOE’s projections of 3.3% consumption and 4.6% peak demand annual average growth rates (AAGR) are being questioned. Some parties believe these are unnecessarily

Energy and Power Sector Prospects 21

high due to the flawed forecasting model of DOE, which relies heavily on historical data and projections of distribution utilities. There is fear that high projections could mean an overcapacity in the future.

This paper deems the projections rather modest; a 10%-20% upward adjustment (i.e. 3.6 - 3.9% AAGR for sales and 5.0 - 5.5% AAGR for peak demand) may be more tenable. First, Mindanao has attained much higher growth rates in sales (e.g. 8.8% in 2004 and 6.1% in 2007) and peak demand (9.7% in 2003 and 6.4% in 2007). The lower sales in recent years were due to constrained supply rather than lower consumption. The limited power supply brought in frequent and long hours of brown outs that cut electricity sales. Second, DOE has been relying on projections of DUs, which have almost always been short of projections. ECs also have the tendency to be conservative to minimize unnecessary purchases. Third, the Barangay Electrification Program and Transco’s transmission development efforts have been aggressively reaching unserved population.

Table 10. List of Committed and Indicative Power Projects

No. Comm Year Power Plant Project Capacity

(MW) Location

1 2012 Minergy Cabulig River HEP* 8 Plaridel, Misamis Oriental

22013

Hedcor Tamugan HEP 11.5 Davao City

3 Aboitiz Tudaya, River HEP 13.6 Davao City

4-5

2014

First Gen Hydro (23MW/30 MW) 53 Bubunawan, Bukidnon/Puyo, Agusan del

Norte6 Aboitiz Coal Fired Plant 150 Misamis Oriental

7-8 Aboitiz Coal Fired Plant (2x150)* 300 Davao Sur

9 Mindanao III Geothermal* 50 Mt. Apo Kidapawan. North Cotabato

10 Bukidnon Multi-Fuel Biomass 35 Maramag, Bukidnon

11 Davao Waste to Energy Project 1.8 Davao City

12 Oriental Odiongan River HEP 22 Gingoog, Misamis Oriental

13

2015

Conal Coal-Fired Plant (1&2) 200 Maasim, Sarangani (100)/Zamboanga City (100)

14 Aboitiz Sita (1,2,3) HEP 42.5 Davao City

15 First Gen River HEP 47 Cabadbaran, Agusan Norte; Tumalaong & Tagoloan, Bukidnon

17 Agus III Hydro 225 Lanao del Norte

18 Amacan Geothermal 20 Amacan, North Davao

19 Wind Power 5 Camiguin Island

20 Siguil (1,2,3)MHP 20 Maasim, Sarangani

22 Energy and Power Sector Prospects

21

2016

Lake Mainit HEP 25 Agusan del Norte

22 Hydropower 68 Tagoloan

23 Impasugong 20 Impasugong, Bukidnon

24 Mainit Geothermal 30 Mainit, Surigao del Norte

25 2017 Ampiro Geothermal 30 Misamis Occidental

26

2018

Balingasag Geothermal 20 Misamis Oriental

27 Mt. Zion Geothermal 20 Cotabato

28 Tamugan Hydropower 27.5 Tamugan

29 Bulanog Batang HEP 150 Talakag, Bukidnon

30 Nubenta Wind Power Project 15

31 Pulangi V 300 Bukidnon

32

2019

Tran River 30 Lebak, Maguindanao

33 Mt. Parker Geothermal 60 South Cotabato

34 Lakewood Geothermal 40 Lakewood, Zamboanga del Sur

35 Amacan Geothermal 40 Compostela Valley

36 2020 Sapad Salvador Geothermal 30 Lanao del Norte

37-44 2024 Tidal Power 24

Bongo Is (1MW); Dapa (5); Hinatuan (10MW); Buculus Is (1); Lugus-Tapul (2.5); Northern Sibulu (2.5); Sibulu Is (1); Simunul (1)

45 2025 Mt. Matutum Geothermal 20 Gen. Santos

46 2013-2030 LNG Terminal 300 Southern Mindanao

47-60

Not Firm 14 Solar Power Projects 280

Iligan City; CDO; Davao; Zamboanga; MisOr; Tawi-Tawi, Sulu; ZamboSur; Kalamansig, Sultan Kudarat; Darong, Hagonoy, and Digos City; Dinagat Island

Total 2,733.9Sources: Transmission Development Plan, 2010, NGCP; RE Plans & Program, DOE; Company websites; News Accounts

Finally, the situation in and around Mindanao has been rapidly changing. Mindanao has been growing and developing faster. Even so, its strong potentials for growth and excellence have yet to be optimized. The Mindanao Peace and Development Framework Plan, 2010-2030 (Mindanao 2020) recognizes these potentials and provides the strategies for harnessing them. Mindanao 2020 targets a GDP growth rate of 8-10% by 2020, assuming proposed strategies are followed, and choke points for growth are promptly addressed. Projections were based on historical averages of GDP, which in 2000-2009 was just 4.6%.

Energy and Power Sector Prospects 23

Recognizing Mindanao’s potentials for growth and keeping in mind that the installation of new capacities on a progressive basis is imperative, efforts to improve the investment environment for the energy sector need to be stepped up. Such efforts must be cognizant of the implications of climate change impacts; hence of the need to diversify energy sources and to promote low carbon investments.

About 100 sites in Mindanao have potentials for RE development (Table 11). Region X has the most number (42) of potential projects, 33 of which are hydropower. ARMM has the strongest potentials for ocean-based plants. All regions have good potential for water-based power projects.

Table 11. Potential Renewable Energy Projects in Mindanao Regions

Region Geothermal Hydro Biomass Wind Solar OceanIX 1 4 - - -X 3 33 1 - 5XI 1 15 1 - -XII 3 8 - - - 1XIII 1 7 - 1 1 2

ARMM - 4 - - - 5Total 9 71 2 1 6 8

Capacity 290 1216 4.8 15 22 24 Source: Department of Energy

III.2 Privatization of Agus and Pulangi Facilities

The 10-year grace period for the privatization of Agus (727MW) and the Pulangui (255MW) facilities has ended, so preparations for privatization have begun. However, the opposition to this has grown very strong. Petitions to government and Congressional bills have been filed and lobby movements were set up. The major arguments against this are:

(a) anticipated increases in electricity rates (i) to attract buyers for the facilities by making generation charge approach Luzon and Visayas levels; and (ii) to account for both the returns on investment and profits of new owners (government only accounts for return on investments);

(b) the resulting dominance and control of the power market by the new owner and eventual creation of private sector monopoly since the combined capacity of the facilities account for half of total installed capacity (inasmuch as the six plants of Agus must be sold and operated in tandem for economy and efficiency); and

(c) possible complication of the GRP-MILF Peace Process since the control of territory and natural resources, which cover the Agus-Pulangi hydro systems, is part of the negotiations agenda.

24 Energy and Power Sector Prospects

On the other hand, the arguments for privatization include:

(a) the urgency to cease government subsidy and check accumulation of debts since the facilities are operating at a loss (see statement of President Aquino in paragraph 28);

(b) mandate to implement the provisions of EPIRA and meet its objectives especially that of ensuring genuine industry competition, a precondition to a working open market trading; and

(c) immediate need to stabilize demand-supply situation and volatility of power rates through open competition and reflection of true costs.

A breakthrough on this impasse came in the form of a Resolution by the 2nd Bukidnon Mindanao Summit held on August 11, 2011 submitted to the Power Sector Assets and Liabilities Management Corporation (PSALM), the caretaker of NPC assets for privatization. The Bukidnon Power Commission reversed its position and indicated its support for the “immediate privatization and endorses the acquisition of Pulangi IV by registered distribution utilities in the Province of Bukidnon…”16 The Commission has planned to form the Bukidnon Power Corp. (BPC) and seek for a negotiated sale of Pulangi IV.

The Joint Congressional Power Commission (JCPC) continues to deliberate on the privatization issue and according to Deputy House Speaker Lorenzo Tañada III17, there has been an evolving idea that either (i) the facilities be run by electric cooperatives to keep the control with Mindanao stakeholders; or (ii) privatize only the planned additional capacity and keep the existing facilities in the hands of government. In line with option (i), Tañada supports the Commission’s plan to buy the Pulangi IV HEP complex.

Bukidnon stakeholders decided to acquire and rehabilitate Pulangi so that the province’s “demand requirement may be met as a matter of privilege, if not right, considering that Bukidnon is the host province of Pulangui.18”They want their two electric cooperatives, the First Bukidnon Electric Cooperative (FIBECO) and Bukidnon Second Electric Cooperative (BUSECO) be given the right of first refusal to acquire Pulangi and handle its rehabilitation.

Meanwhile, the DOE and NPC have prepared a rehabilitation plan for the facilities to improve generation capabilities and avert another supply shortage. The seven hydropower facilities have been de-rated to about 61% of total installed capacity due to their old age and impacts of siltation as follows: Agus 1 from 80 MW to 35 MW; Agus 2 from 180 MW to 80 MW; Agus 4 from 158 MW to 100 MW; Agus 5 from 55 MW to 30 MW; Agus 6 from 200 MW to 130 MW; Agus 7 from 54 MW to 25 MW; and Pulangi 4 from 255 MW to 200 MW. The

16 Minda News; http://www.mindanews.com/top-stories/2011/08/15/bukidnon-power-commission-“we’ll-buy-pulangui-iv”/; August 15, 2011

17 Bukidnon News; http://bukidnonews.wordpress.com/2011/09/10/tanada-privatization-of-agus-pulangi-“not-yet-inevitable”/; September 10, 2011.

18 Powerpoint presentation of Bukidnon Second Electric Cooperative

Energy and Power Sector Prospects 25

plan also involves the dredging of Pulangi and equipment rehabilitation of Agus plants in 2012 at the estimated cost of P3.65 billion. The rehabilitation is expected to increase the total capacity of the plants by 100-200MW.

III.2 Wholesale Electricity Spot Market

EPIRA provides for the establishment of the Mindanao Wholesale Electricity Spot Market (WESM) to address inefficiencies, encourage competition, attract investors and give consumers the right to choose the power they would consume. Based on the Visayas experience, WESM could also free up embedded19 capacities that can help meet demand.

There are two important preconditions for WESM to work well in Mindanao. The first is the privatization of Agus and Pulangi facilities to break the dominance of NPC and prevent a government-private sector competition. The assumption here is that the facilities would also be sold to a number of investors so that no one may dominate and control the market. The second is the strengthening of ECs so that these may have the capability to participate in open trading. The first precondition would take some time to happen. The second seems to be proceeding with some progress, but not quite for ARMM ECs.

Mindanawons are also divided on the Mindanao WESM issue. Those who oppose it, at least in the immediate future, cite that the government is still the biggest power generator. Others want its immediate establishment to free up embedded capacities and fill in the supply gap. On the other hand, DOE is proceeding cautiously and reviewing various options because of the precarious supply-demand situation. A slight shortage can jack up prices, which may be blamed on WESM. Reliance on hydropower in the face of thin reserves and climate change impacts is also a concern because of its implications on supply and prices.

The experience with the WESM in Luzon adds to these fears. Electricity rates have increased since WESM started in 2006 because only the more expensive power is traded. This is seen to have pushed Luzon electricity costs to among the highest in the world.

III.3 Energy Plan and Policy

Former Energy Secretary Vincent Perez has described the approach to Philippine RE policy-making as piecemeal, as illustrated in Figure 5. RE-Act attempted to harmonize the existing laws and policies and to complement the reforms put in place by EPIRA. Nonetheless, the energy sector has remained unsettled particularly in the area of pricing.

Business, labor and other civil society organizations recently called on President Benigno Aquino to have a clear national energy road map that would achieve electricity supply stability and bring down power rates. This is despite the existence of the National Energy Plan (NEP) and National RE Program (NREP), which serve as the road maps for both EPIRA

19 Embedded generation is usually a small scale production of power connected within the distribution network and not having direct access to the transmission network.

26 Energy and Power Sector Prospects

and RE-Act. The public clamor indicates the inability of the laws and the plans to achieve their objectives of stabilizing demand and supply and making electricity affordable. For this reason, many are now rejecting important provisions of EPIRA and RE-Act.

Figure 5Philippine Energy Policies

Source: Vincent S. Perez, Status of Renewable Energy Policy in the Philippines (a presentation)

Mindanao’s energy sector is in a precarious situation. While it is highly dependent on the resolution of prevailing national issues, the sector must focus on resolving its own issues and having a clear direction for its own security and sustainability. This calls for the preparation of a coherent Mindanao energy plan or road map that localizes and harmonizes the National Energy Plan (NEP) and National RE Program (NREP). DOE has already initiated the process and has begun coordination with the Mindanao Development Authority (MinDA). Active work has yet to commence, which may hopefully be triggered by the Mindanao Energy Forum held in November 2011 by DOE.

IV. Recommendations

Numerous issues were raised above, and yet cover only a fraction of the complex energy sector. A number of these issues are critical to Mindanao but decisions are made at the national level. The following recommendations, therefore, are classified into national and Mindanao-level actions, and areas for possible intervention by development institutions. In general, proposed actions must involve all stakeholders but lead actors are identified as necessary.

Recommendations 27

For national policy and decision-makers:

Establish a clear policy on payment (i.e., particularly as compensation for host communities) for use of water as a natural resource, akin to mining royalties, and on the forms and uses of such payment, with appropriate legislation as may be warranted. This must consider the stability and affordability of power costs for consumers. [National Government]

Review prevailing power pricing policies and structures with the end in view of improving efficiency of producers and distribution utilities, and minimizing the burden on the consumers. [ERC with stakeholders including generators, NGCP, DUs, public/consumers, etc.] In particular:

a. Review the various charges and fees in the power rate structure against respective objectives (e.g., fairness of charging system losses and stranded costs of utilities) and against other benefits accruing to utility companies (e.g. incentives). Since the User Charge is non-passable, ERC must carefully and transparently review (i.e. provide public access to company data and their analysis) the components of this charge to impel utilities to exercise greater prudence with their contracts.

b. Charge administrative losses (own-use power) to generators and distribution utilities rather than to consumers, to promote energy conservation and efficiency in management of operations on the part of the power utilities.

c. Charge non-technical losses (theft and pilferage) to distribution utilities, to discourage complacency and promote close monitoring and inspection of grid lines and electric meters.

d. Prescribe and enforce a phased reduction of the caps on technical losses over a period of time (3-5 years) rather than leave the determination of when and how much to ERC. This will provide the utilities impetus to develop a system-loss-reduction program and prepare for eventualities. This scheme may be further reinforced by an incentives-and-rewards mechanism to strengthen its effectiveness. The cap levels and adjustment schedule must be carefully studied based on local and international experiences and standards. Notwithstanding this, the minimum level should be less than 5% since many ECs have demonstrated that this level is attainable even at a time when the cap was set high.

e. Review the RE pricing policy and the FIT scheme with due attention to the following:

o Reconsider the mechanism for ensuring fair returns to RE technology

28 Recommendations

developers and investors, including allocation of the incidence of the costs among power consumers and general taxpayers, and proper timing of recovery of their investments. For example, frontloading of cost recoveries needs to be reconsidered in light of the long life spans of some RE technologies (e.g., up to 100 years for run-of-river HEP), implying that the recovery of development and investment costs may be spread over longer periods.

o Examine the FIT rates vis-a-vis the generous incentives package. The FIT is already an attractive investment incentive in itself. Providing an incentive package on top of FIT would mean that both government (taxpayers) and consumers are subsidizing the utility and that the consumers are hit twice (i.e., through their subsidy and constrained government services).

o Hasten the approval of fair and proper FIT rates and of installation capacities to accelerate decision-making on projects in the pipeline and unleash the potentials of RE.

f. Reflect the true costs of power generation in the pricing of power in Mindanao. It would be necessary to gradually phase out subsidy to power generation by NPC, facilitate the privatization of Agus and Pulangi plants, and consider payment for water use (see paragraph #76).

Exert deliberate and sincere efforts to provide transparency in the sector. This would include involving experts, media and civil society organizations in addition to the usual entities such as ERC, NEA, Utilities, and consumers in key functions such as rate-setting and other aspects of regulation. [ERC, DOE]

In particular:

a. Provide reasonable access to company data and records;b. Engage more involved participation of local experts (e.g., energy economists)

and NGOs in the analysis and rate computation in addition to participation in the usual public hearings;

c. Keep media proactively informed of developments in regulatory proceedings.

Further democratize and localize power generation, through measures such as:

a. Prioritize and provide the enabling environment for the development of small-scale and community-based generation facilities. Demonstrated successful experiences of NGOs and communities may be adopted and adapted, improved and up-scaled. There must be a deliberate effort to take stock of such good practices already in existence in various places and determine how to improve on them and adapt them to local circumstances.

Recommendations 29

b. Encourage and facilitate the adoption and adaptation of democratization schemes such as the “One Million Solar Rooftops” of Representative Casiño.

Strengthen and sustain public awareness on energy issues (e.g., pricing) and energy conservation through a public information and education program. Promoting wide awareness on energy sector issues and pricing is in line with paragraph #78 and the value of stronger public participation. Energy conservation awareness will help close the demand-supply gap, reduce prices and promote environmental protection. [DOE, Relevant NGOs]

For Mindanao stakeholders, investors and the general public

Formulate a Mindanao Energy Development and Sustainability Plan that sets forth clear policies and strategies, and puts in place coherent programs and projects that would lead to Mindanao’s long-term energy security and self-sufficiency at least cost. [MinDA and DOE]

Stabilize the power supply situation and moderate the reliance on hydropower [DOE, private sector, Mindanao stakeholders]

a. Establish more biomass power-generating facilities drawing on the region’s abundant agricultural wastes, to moderate dependence on hydropower and generate less expensive power. Analyze and strengthen the value chain with the help and cooperation of big agricultural and industrial producers.

b. Replace expensive diesel-run facilities with suitable RE technologies e.g. solar, wind and river hydro in off-grid areas or island municipalities. NPC and LGUs must try to encourage and assist these kinds of shifts. Build capacity of ECs to manage RE plants.

c. Urgently rehabilitate Agus and Pulangi facilities and their watershed and river systems.

Assist and support national government in rationalizing the energy sector, through particular Mindanao initiatives such as:

d. Enable and support initiatives by interested local parties to acquire and manage the Agus and Pulangi facilities. In particular, a current initiative by Bukidnon ECs and stakeholders to purchase Pulangi merits wide support, especially in effectively managing such a large and complex operation.

e. Lay the groundwork for the establishment of the Mindanao Wholesale Electricity Spot Market. This will entail promoting the privatization of Agus and Pulangi. Mindanao stakeholders need to actively participate and cooperate

30 Recommendations

in identifying privatization options and development of privatization plans. DOE must in turn provide the venue and mechanisms for such participation.

f. Hasten the strengthening and improvement of efficiencies of Electric Cooperatives through the following: [NEA]

o Review the “cash reimbursement basis” policy to strengthen the stake and profit incentive of EC members.

o Review experiences and assess performance of Mindanao ECs under the EPIRA regime to determine areas of weaknesses and needed interventions.

o Analyze factors for poor performance of ARMM ECs and design more appropriate rehabilitation and reinforcement schemes, drawing on useful lessons from the LASURECO turnaround. Related to this, explore alternatives to the cooperative as business model for electric power distribution in ARMM, in light of the observations made earlier on incompatibility with the culture of “Datuism” prevalent in the region.

o Drastically cut system and administrative losses as proposed above.o Strengthen capacities of ECs in planning, forecasting, management and

other areas of weaknesses that may be identified.o Build awareness and appreciation of benefits from and responsibilities to

ECs among member-consumers to promote prompt payment of electric bills and minimize theft and pilferage.

For development institutions

Finally, many of the recommendations above require technical (e.g., those for review and study) and financial assistance (e.g., acquisition of Pulangi). Some may be packaged as components of an assistance programme for Mindanao, such as the recommendations directed towards the lowering of prices in paragraph 77, and the strengthening of ECs.

In conclusion, the way out of Mindanao’s current power difficulties will be full of challenges and hurdles. Given the long gestation of power projects coupled with institutional rigidities that characterize the sector, it will take some time before Mindanao’s power situation would normalize to one marked by ample energy supplies at competitive cost. The challenge to government and all concerned stakeholders is to work together to achieve that desired situation at the shortest time possible.