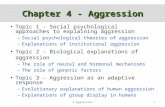

Overt and Relational Aggression in Adolescents.Social–Psychological Adjustment of Aggressors and...

-

Upload

cristina-miutu -

Category

Documents

-

view

27 -

download

2

description

Transcript of Overt and Relational Aggression in Adolescents.Social–Psychological Adjustment of Aggressors and...

Overt and Relational Aggression in Adolescents: Social–PsychologicalAdjustment of Aggressors and Victims

Mitchell J. PrinsteinDepartment of Psychology, Yale University

Julie BoergersBrown Medical School

Eric M. VernbergUniversity of Kansas

Examined the relative and combined associations among relational and overt forms ofaggression and victimization and adolescents’concurrent depression symptoms, lone-liness, self-esteem, and externalizing behavior. An ethnically diverse sample of 566adolescents (55% girls) in Grades 9 to 12 participated. Results replicated prior workon relational aggression and victimization as distinct forms of peer behavior that areuniquely associated with concurrent social–psychological adjustment. Victimizationwas associated most closely with internalizing symptoms, and peer aggression was re-lated to symptoms of disruptive behavior disorder. Findings also supported the hy-pothesis that victims of multiple forms of aggression are at greater risk for adjustmentdifficulties than victims of one or no form of aggression. Social support from closefriends appeared to buffer the effects of victimization on adjustment.

Until recently, research on childhood aggression to-ward peers focused almost exclusively on children’sphysicalorovert actsofaggressivebehavior, suchashit-ting, pushing, or threatening to beat up a peer. Findingsfrom this work have indicated that overt aggression ismore prevalent for boys compared with girls, and thisform of aggression is a stable and potent predictor ofschool-age children’s social–psychological adjustment(for reviews, see Coie, Dodge, & Kupersmidt, 1990;Parker & Asher, 1987). Contributing substantially tothis prior work, recent research has provided compel-ling evidence for a relational form of aggressive behav-ior. In contrast to overt aggression, which includes actsmeant to harm a peer physically, relational aggressionuses a child’s relationship with another teen, or theirfriendship status, as a way of inflicting social harm (e.g.,purposefully excluding a peer from social activities,threatening towithdrawone’s friendship, telling rumorsor gossip; Crick, 1995, 1997; Galen & Underwood,1997). Recent findings indicate that relational aggres-sion is as prevalent among girls as boys and appears to

uniquely contribute to children’s concurrent and futuresocial–psychological maladjustment for both sexes(Crick, 1996; Crick & Grotpeter, 1995; Galen & Under-wood,1997).AsnotedbyCrick(1995), thisworkhasdi-rected needed attention to the study of aggression ingirls and to alternate forms of aggressive behavior thatare strongly associated with maladjustment.

In contrast to research on aggressive children, rela-tively few studies have examined the victims of aggres-sion,particularlyvictimsof relationalaggression(Crick& Grotpeter, 1996). However, extant work on peer vic-timization indicates that like peer aggressors, victims ofpeer aggression also experience significant levels ofpsychological distress. For instance, studies on victimsof overt aggression have revealed that this form of vic-timization concurrently and prospectively predicts de-pression, loneliness, and externalizing problems(Boivin, Hymel, & Bukowski, 1995; Hodges, Boivin,Vitaro, & Bukowski, 1999; Olweus, 1992; Vernberg,1990).This isconsistentwith theorysuggesting thatvic-timizedchildreneithermay interpret thesenegativepeerexperiences as critical appraisals of the self leading tointernalized distress (e.g., depression, loneliness, lowself-worth) or may develop pejorative attitudes towardtheir peers, subsequently leading to self-control prob-lems, anger, and perhaps impulsive or oppositional be-havior to retaliate against peers (Crick & Bigbee, 1998;Crick, Grotpeter, & Rockhill, 1999). In the few studiesthat examined social–psychological correlates of rela-tionalvictimization, findings suggested that this formofvictimization also is associated with depression, loneli-

479

Journal of Clinical Child Psychology Copyright © 2001 by2001, Vol. 30, No. 4, 479–491 Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

We thank Dana Damiani and Beth Vellis for their assistance indata collection and the members of the New England Social Develop-ment Consortium for comments on an earlier draft of this article.

This work was supported in part by National Institute of MentalHealth National Research Service Award No. F32–MH11770awarded to Mitchell J. Prinstein.

Requests for reprints should be sent to Mitchell J. Prinstein, YaleUniversity, Department of Psychology, P.O. Box 208205, New Ha-ven, CT 06520–8205. E-mail: [email protected]

ness, and self-restraint difficulties and appears to con-tribute uniquely to school-age children’s distress evenafter the effects of overt victimization (Crick &Grotpeter, 1996) and overt and relational aggression(Crick & Bigbee, 1998) are controlled.

To date, relational aggression and victimizationrarely have been studied among adolescents, althoughthese ideas seem particularly relevant during this devel-opmental stage for several reasons. First, the increasedamount of time adolescents spend with their peers andthe increased importance placed on peer support duringthis developmental period suggest that relational formsof aggression and victimization may be more salient(Parker, Rubin, Price, & DeRosier, 1995). Cliques alsobecome more prominent features of adolescent peer re-lationships, and these typically have more sharplydrawn boundaries than the less selective chumships ofmiddle childhood (Brown, 1989). These boundariesmay be drawn and maintained through relational ag-gression, including ostracism, exclusion, or characterassassination. Second, with increases in physicalstrength and access to weapons during adolescence,overt physical aggression carries greater risk of seriousinjury or legal sanctions (Cairns, Cairns, Neckerman,Ferguson, & Gariépy, 1989). Relational aggressionmay partially replace physical aggression as a safermeans of expressing disdain, displeasure, or anger.Also, cognitive advances in adolescence, such as in-creased capacity for planning and greater understand-ing of sarcasm and innuendo, may allow the morerefined and hurtful use of relational aggression(Creusere, 1999; Winner, 1988). Finally, self-disclo-sure in friendships increases during adolescence, per-haps increasing opportunities to use private, personalinformation as a weapon when friendships fail (Parkeret al., 1995).

Therefore, an initial goal of this research was to rep-licate and extend prior work on relational aggression byexamining whether this form of aggressive behaviorwould emerge as a distinct construct from overt aggres-sion for adolescents. Similarly, the delineation of twoforms of victimization—relational and overt—also wasexamined. As demonstrated in prior work with elemen-tary school age children, it was hypothesized that rela-tional forms of aggression and victimization would berevealed as distinct factors from overt aggression andvictimization. We further hypothesized that adoles-cents would report higher frequencies of relationalcompared with overt aggression and victimization, in-dicating that this form of aggression is relatively morecommon in this age group. Additionally, in accordancewith research on younger children, adolescent boyswere expected to report more frequent experiences withovert forms of aggression and victimization; however,relational aggression and victimization were expectedto be reported at comparable levels by adolescent boysand girls (Crick & Grotpeter, 1996).

To address these hypotheses, an existing measurewith established psychometric properties was adaptedto appropriately capture forms of overt and relationalaggression and victimization in adolescence (Vernberg,Jacobs, & Hershberger, 1999). Consistent with past re-search on peer victimization, a self-report assessmentwas used in this study. As noted in prior work also usingthis approach (e.g., Boulton & Underwood, 1992;Crick & Grotpeter, 1996), the use of self-report allowedus to examine whether adolescents could perceive twodistinct forms of peer aggression and victimization andalso allowed adolescents to report victimization experi-ences that may occur outside of the school setting or co-vertly in school and therefore may not be fully reportedby other informants (Crick & Bigbee, 1998). This latterpoint was particularly important given the more subtleor covert forms of peer aggression and victimizationlikely exhibited by adolescents compared with youngerchildren. Recent research has revealed no evidence ofbias for self- versus peer-reported frequencies of overtor relational victimization among distressed childrenand good support for the correspondence between self-reported victimization and the identification of victimsby external reporters (Crick & Bigbee).

A second and main goal of this research was to ex-amine the unique contributions of relational aggressionand victimization in predicting adolescents’concurrentsocial–psychological adjustment. Two sets of hypothe-ses were proposed. First, we anticipated that relationalaggression would be uniquely associated with concur-rent adolescent depression symptoms, loneliness, self-esteem, and externalizing behavior after we controlledfor overt aggression. Similarly, relational victimizationwould be significantly associated with these areas ofsocial–psychological adjustment after we controlledfor overt victimization, thus supporting the importanceof relational forms of aggression and victimization inadolescence. A second hypothesis, rarely examined inprior work, was the relative contribution of aggressionand victimization given that each has been linked withsimilar deleterious consequences. We hypothesizedthat when forms of aggression and victimization wereconsidered together, aggressive behavior, particularlyadolescents’ overt aggression, would be associatedmost closely with concurrent externalizing difficulties(i.e., symptoms of oppositional defiant disorder or con-duct disorder), whereas indicators of internalizing dis-tress (i.e., depression, loneliness, and global self-worth) would be linked most closely to both forms ofpeer victimization and relational forms of peer aggres-sion. We further predicted gender differences in theseassociations. Specifically, we hypothesized that forgirls, both relational and overt aggression toward otherswould be associated with concurrent adjustment diffi-culties, whereas only overt aggression toward otherswould be related to adjustment difficulties for boys, ashas been demonstrated in past work (Crick &

480

PRINSTEIN, BOERGERS, VERNBERG

Grotpeter, 1995). For victimization, it was hypothe-sized that both relational and overt forms of victimiza-tion would contribute to social–psychologicaladjustment for both boys and girls (Crick & Grotpeter,1996). Such a finding would extend prior work on rela-tional aggression and girls’adjustment in younger chil-dren (e.g., Crick & Bigbee, 1998) and would extendfindings for victimization by examining the adjustmentof adolescents who are relationally victimized.

A third goal of this investigation was to examine theco-occurrence of multiple forms of aggression or multi-ple forms of victimization. In other words, are adoles-cents who are overtly and relationally aggressivetoward peers at more serious risk compared with ado-lescents who use only one form of aggression? Simi-larly, are adolescents who are victimized by peers bothrelationally and overtly more psychologically malad-justed than those victimized through one form of ag-gression alone? We examined these intuitive but rarelyexamined hypotheses in this investigation, as well asgender differences in these relationships.

A fourth goal was to examine close friend social sup-port as a potential buffer from the negative psychologicalconsequences of peer victimization (Hodges et al., 1999;Vernberg, 1990). This is consistent with theory regardingthe importance of close interpersonal relationships withpeers as a crucial factor for adolescents’ psychologicaldevelopment (e.g., Hartup, 1996; Sullivan, 1953) and afactor that can reduce the negative effects of stressful ex-periences, such as peer victimization (Cohen & Willis,1985). Vernberg (1990) found that early adolescents witha close friend were able to maintain an adequate sense ofsocial acceptance despite overt victimization, whereasvictimization predicted declines in perceived social ac-ceptance over time for isolated adolescents. More recentwork with school-age children has revealed a significantassociation between overt peer victimization andexternalizing behavior only among friendless children(Hodges et al., 1999). This effect was attenuated by thepresence of a close friend, presumably due to the in-creased emotional support available to victimized chil-dren who have a close friend (Hodges et al.). This studymore specifically investigates this hypothesis by examin-ing close friend social support as a potential buffer in thecontext of relational victimization; this has not been ex-amined previously for adolescents.

Method

Participants

Participants included 566 adolescents (253 boys,44.7%; 313 girls, 55.3%) in Grades 9 (27.2%), 10(25.4%), 11 (23.8%), and 12 (23.4%) from a highschool in a small city in southern New England. Ado-lescents came from ethnically diverse backgrounds

(21.8% Caucasian, 60.3% Hispanic, 10.6% AfricanAmerican, 7.3% other or mixed ethnicity) within a cityof fairly homogeneous socioeconomic status (medianfamily income = $33,679; Census of Population andHousing, 1990). According to school records, approxi-mately 54% of students were eligible for free or re-duced lunch; approximately 21% of students’ parentsdid not finish high school, and 16% of parents gradu-ated from college.

Procedures

Data were collected as part of this school district’shealth screening curriculum to serve as a baseline for aschool district intervention program. All data were col-lected anonymously; no identifying information wasobtained with the exception of adolescents’ sex, grade,and ethnicity. Parents of all schoolchildren (n = 706)were notified of the school data collection 3 weeks be-fore the administration of questionnaires so that theycould decline their adolescents’ participation, if de-sired. Less than 1% of parents (n = 5) declined their ad-olescents’ participation. Additionally, adolescentswere assured of the confidentiality of their responsesand of their voluntary participation (96% of adoles-cents agreed to participate; n = 26 refusals). With thesefew exceptions, all students present on the 4 days oftesting (n = 32 absent) completed the packet of ques-tionnaires (n = 643; 91.1% of total school population).

Measures were completed through group adminis-tration with an adult-to-adolescent ratio between 1:5and 1:10, and all adolescents were able to complete thepacket of questionnaires in the allotted time (approxi-mately 1 hr). Nevertheless, we were cautious about thevalidity of these data, and each protocol was checkedthoroughly and discarded for inconsistencies or miss-ing responses. Data were excluded for 12% of partici-pants (n = 77) who were missing data on one of theprimary measures in this study; these participants’ re-sponses on related measures did not indicate any signif-icant differences from the full sample. A final sample of566 adolescents with complete data was included insubsequent analyses.

Measures

Overt and relational aggression/victimization. Arevised version of the Peer Experiences Questionnaire(Vernberg et al., 1999) was used in this study to assessadolescents’ aggression and victimization. Five itemswere revised, created, or added from prior instruments(Lopez, 1998) to reflect developmentally appropriateforms of relational aggression and victimization in ado-lescents. The final questionnaire included nine items,each presented in two versions. For the aggressor ver-

481

OVERT AND RELATIONAL AGGRESSION

sion of each item, adolescents were asked to indicatehow often (1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = a few times,4 = about once a week, 5 = a few times a week) they en-gaged in each behavior toward another teen (e.g., “Ichased a teen like I was really trying to hurt him orher”). The victim version of each item asked how ofteneach behavior had been directed toward the informant(e.g., “A teen chased me like he or she was really tryingto hurt me”). The order of presentation of the victim andaggressor versions was counterbalanced.

Psychometric support for this measure, including astable factor structure and adequate internal consis-tency, is presented subsequently. The initial version ofthe Peer Experiences Questionnaire has demonstratedgoodvalidity inrelatedstudieswithchildrenandadoles-cents. Significant correlations between self-reportedvictimization and parent-reported victimization (rs be-tween .36 and .39, p < .001) have been observed in twoseparate samples (Champion, 1997; Vernberg, Fonagy,& Twemlow, 2000). This level of parent–adolescentagreement is comparable to that typically found in thisage range (Achenbach,McConaughy,&Howell, 1987).In addition, self-reported aggression and victimizationon the Peer Experiences Questionnaire was signifi-cantly correlated with peer reports of the same con-structs (rs between .34 and .40, p < .001). Test–retestreliability over a 6-month interval has ranged between.48 and .52.

Depression symptoms. The Center for Epidemi-ological Studies–Depression (CES–D) is a widely used20-item measure for the assessment of depressionsymptoms in both normative and clinical samples of ad-olescents (Hogue & Steinberg, 1995; Roberts, An-drews, Lewinsohn, & Hops, 1990). Adolescentsrespond to items by using a 4-point Likert-type scaleranging from 1 (never) to 4 (most of the time) to indicatehow often they have experienced each depressivesymptom. A mean across all items, with appropriate re-verse coding, was computed to produce a total score ofdepressive symptoms. Good psychometric data existfor use of the CES–D with adolescents, including highinternal consistency (>.87) and a stable factor structurewhen readministered 1 month later (Roberts et al.,1990). Cronbach’s alpha in our sample was .92.

Loneliness. TheUCLALonelinessScale(Russell,Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980) is a reliable, 20-item instru-mentwidelyused toassess loneliness inadolescence.Re-sponses are on a 4-point Likert-type scale, with someitems positively worded and reverse coded, and a meanscore across all items is computed. Internal consistency(α = .94), test–retest reliability, and concurrent anddiscriminantvalidity supportwereprovidedbyRussell etal. (1980).Thismeasuredemonstratedgoodinternalcon-sistency in our sample as well (α = .86).

Self-esteem. Harter’s (1988) Self-PerceptionProfile for Adolescents (SPPA) assesses adolescents’self-perceptions in six domains (e.g., romantic appeal,friendship competence, etc.). In this study, the GlobalSelf-Worth subscale was included as a measure of self-esteem. This subscale contains six items; each item iscoded with a score of 1 through 4, and a mean across allsix items was computed with higher scores reflectinggreater self-esteem. Harter (1988) reported good inter-nal consistency for the SPPA (Cronbach’s α = .74–.93),as well as considerable support for the validity of thesesubscales. In our sample, this subscale also demon-strated good internal consistency (α = .81).

Externalizing symptoms. The Diagnostic Inter-view Schedule for Children (DISC) Predictive Scales(DPS; Lucas et al., 1999) are statistically derivedchecklist versions of the National Institute of MentalHealth (NIMH)–DISC semistructured diagnostic inter-view (Shaffer et al., 1996). Each screener scale of theDPS includes 3 to 10 items from the original NIMH–DISC that have demonstrated the highest item–totalcorrelation with the full NIMH–DISC administrationand maximized sensitivity and specificity using re-ceiver operating characteristic curves. The DPS wasderived from a nationwide sample of more than 1,200children and adolescents and was cross-validated ontwo additional samples. In this study, DPS questionsfrom the Oppositional Defiant Disorder and ConductDisorder modules (16 questions total, each using a 3-point scale) were combined to form a composite meanscore of externalizing behavior. Internal consistency(α) in this sample for these items was .88.

Close friend social support. The Close Friendsubscale of the Social Support Scale for Children andAdolescents (Harter, 1989) was used to assess adoles-cent perceptions of social support from close friends(six items). Each question is scored on a 4-point scale,and a mean is computed across all six items, with higherscores reflecting greater perceived support. Harter(1989) provided extensive data to support the reliabilityand validity of this instrument. Internal consistency inthis sample was .83.

Results

Factor Analyses of the Revised PeerExperiences Questionnaire (RPEQ)

A principal components factor analysis usingvarimax rotation was conducted for the nine items ofthe RPEQ. Separate factor analyses were conducted forthe victim and aggressor versions of this questionnaire,which provided an opportunity to examine the stabilityof this factor structure for peer victimization and peer

482

PRINSTEIN, BOERGERS, VERNBERG

aggression. As indicated in Table 1, this analysisyielded a two-factor solution (eigenvalues > 1) for bothversions, with expected items loading onto factors ofovert and relational forms of aggression or victimiza-tion and no significant cross-loadings. These factoranalyses were repeated for each sex; there were nomeaningful differences in the factor structure on eitherversion of this measure. Subscales were computed asmeans of the items that loaded onto each factor, yield-ing four subscales: Overt Aggression (four items,Cronbach’s α = .80), Relational Aggression (five items,α = .77), Overt Victimization (four items, α = .79), andRelational Victimization (five items, α = .76). Signifi-cant correlations were revealed between overt and rela-tional aggression (r = .52, p < 001) and between overtand relational victimization (r = .51, p < 001), replicat-ing prior work (Crick & Grotpeter, 1996).

Frequencies of Overt and RelationalAggression and Victimization—Overalland Gender Differences

To examine the hypotheses that relational forms ofaggression and victimization would be more prevalentthan overt aggression and victimization for adoles-cents, and that boys would report greater levels of overtaggression and victimization than girls, a repeatedmeasures factorial multivariate analysis of variance(MANOVA) was conducted. Within-subjects factorsincluded two forms of aggression (i.e., relational andovert) and two forms of victimization, and sex was in-cluded as a between-subject factor, thus producing a 2 ×2 × 2 design. Significant main effects for relational ver-sus overt aggression, Wilks’s Λ (1, 564) = 4.26, p < .05,

relational versus overt victimization, Wilks’s Λ (1, 564)= 93.63, p < .001, and all two-way interactions with sex,Wilks’s Λ (1, 564) 4.46–24.14, all p < .05, were quali-fied by a significant three-way interaction, Wilks’s Λ(1, 564) = 8.18, p < .01. In sum, significant findings re-vealed that boys reported significantly higher levels ofovert aggression and overt victimization than did girls;however, boys and girls reported comparable levels ofrelational aggression and relational victimization (seeTable 2 for means). In addition, for both boys and girls,relational forms of victimization were reported withgreater frequency than overt forms of victimization.Boys reported the use of overt and relational forms ofaggression at a comparable frequency, whereas girls re-ported the use of relational aggression significantlymore than overt forms of aggression. Yet, the absolutemagnitude of these statistically significant differenceswas relatively small (η2 = .07–.14), suggesting thatthese gender differences may not be substantial.

Because this was an ethnically diverse sample, eth-nic differences in the frequencies of overt and relationalaggression and victimization also were examined.MANOVA and regression analyses revealed no signifi-cant multivariate or univariate differences for any of thefour subscales by ethnicity, and no significant sex byethnicity interactions were revealed.

Unique Associations Among RelationalAggression and Victimization and Adolescents’Social–Psychological Adjustment

Hierarchical linear regressions were conducted toexamine whether relational aggression added signifi-cant explained variance in adolescents’ concurrent de-

483

OVERT AND RELATIONAL AGGRESSION

Table 1. Factor Analyses of the Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire—Victim and Aggressor Versions

Victim Version Aggressor Version

Subscale and Itema Factor I Factor II Factor I Factor II

% Variance explained 28.60 28.39 29.37 28.32Overt

A teen hit, kicked, or pushed me in a mean way. .79 (.19) .85 (.12)A teen threatened to hurt or beat me up. .77 (.25) .78 (.20)A teen chased me like he or she was really trying to hurt me. .75 (.21) .77 (.21)A teen grabbed, held, or touched me in a way I didn’t like. .73 (.14) .65 (.25)

RelationalA teen left me out of what he or she was doing. (.20) .80 (.22) .74A teen left me out of an activity or conversation that I really

wanted to be included in.(.16) .75 (.29) .67

A teen did not invite me to a party or other social event eventhough he or she knew that I wanted to go.

(.21) .73 (.12) .72

A teen I wanted to be with would not sit near me at lunch orin class.

(.15) .65 (.09) .77

A teen gave me the silent treatment (did not talk to me onpurpose).

(.36) .47 (.38) .54

Note: Factor loadings greater than .40 are shown.aWording for the victim version is listed in this table. For the aggressor version, pronouns were reversed (e.g., “I hit, kicked, or pushed another teenin a mean way,” “I threatened to hurt or beat up another teen,” etc.).

pression symptoms, loneliness, self-esteem, andexternalizing behavior above and beyond the contribu-tion of overt aggression. Similarly, we examined therole of relational victimization after controlling forovert victimization. For both sets of analyses, overtforms of aggression (or victimization) were entered onan initial step, followed by relational aggression (orvictimization) on a second step to reveal incrementalexplained variance. R2 and r2∆ are listed in Table 3 foreach dependent measure of social–psychological ad-justment, analyzed separately for boys and girls (fol-lowing Crick & Bigbee, 1998). A conservativeexperiment-wise Bonferonni correction (.05/24 regres-sion analyses) of p < .002 was applied.

As shown in Table 3, relational aggression explained asignificant portion of variance associated withexternalizing symptoms for girls, after we controlled forovert aggression. This finding was even more pronouncedwhen we examined the unique contribution of relationalforms of victimization after controlling for overt victim-ization. For boys, relational victimization added signifi-cantly to the prediction of all three areas of internalizingadjustment, most notably for boys’ concurrent self-es-teem, for which relational victimization explained nearlyas much unique variance as overt aggression. Consistentwithpriorwork, relationalvictimizationappeared tobees-pecially associated with girls’ concurrent adjustment. Forall outcomes measures, with the exception of girls’externalizing behavior, relational victimization explainedasignificantportionofuniquevariance,afterwecontrolledfor overt victimization. Indeed, compared with overt vic-timization, relational victimization explained more thantwice as much variability in girls’ concurrent lonelinessand self-esteem (see Table 3).

Relative Contributions of Overt andRelational Aggression andVictimization to Adolescents’ Social–Psychological Adjustment

By examining the relative contribution of both overtand relational forms of aggression and victimization in

multiple regressions, it was possible to determinewhich of these variables was most strongly associatedwith each domain of social–psychological adjustmentafter we controlled for their shared variability. Theseresults are summarized in Table 4, which lists thesemipartial correlation coefficients and the standard-ized regression coefficients (β) for all four subscales ofthe RPEQ when entered together as a block in one stepof the multiple regression. By squaring and summingthe semi-partial correlations for each of the four predic-tors, it was also possible to calculate the shared vari-ability among predictors that was associated with eachmeasure of social–psychological adjustment and theunique variance that was added by each predictor be-yond the shared variability. As shown in the table, sepa-rate regressions were conducted for each outcomevariable (i.e., depression, self-esteem, loneliness, andexternalizing behavior). Initially, regression equationsincluded interaction terms to test for sex differences inthese associations, which were followed by regressionsconducted separately by sex. Because many of these in-teractions were significant, only these latter results arepresented in Table 3, and significant sex interactionsare noted subsequently.

Several consistent findings across sex were re-vealed. First, the models accounted for a sizable portionof the variance in each measure of social–psychologi-cal adjustment. As a block, the forms of aggression andvictimization accounted for 9% to 23% of the variancein boys’ social–psychological adjustment and 3% to17% in girls’adjustment. In addition to this shared vari-ability among the predictors, several significant associ-ations for each individual predictor emerged,explaining additional variability in adolescent adjust-ment. Indeed, the combination of unique and sharedvariability (i.e., total R2; see Table 4) accounted for11% to 34% of the variance in adolescent adjustment,which increased to 14% to 42% explained variance af-ter we controlled for unreliability by using LISREL.1

484

PRINSTEIN, BOERGERS, VERNBERG

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, and Observed Ranges for Primary Variables

Boys Girls Total

M SD M SD M SD Range

Overt aggression 1.63 .78 1.27 .52 1.43 .67 1.00–5.00Relational aggression 1.64 .72 1.57 .57 1.60 .64 1.00–5.00Overt victimization 1.43 .62 1.29 .49 1.35 .55 1.00–5.00Relational victimization 1.60 .67 1.56 .56 1.58 .61 1.00–5.00Depression 1.74 .47 1.89 .56 1.83 .52 1.00–3.70Loneliness 1.87 .46 1.80 .47 1.83 .46 1.00–3.60Self-esteem 3.07 .70 3.03 .78 3.05 .74 1.00–4.00Externalizing symptoms 1.60 .44 1.46 .39 1.53 .42 1.00–3.00Close friend social support 3.22 .62 3.43 .66 3.34 .65 1.00–4.00

1LISREL allows the researcher to examine path associations whilecontrolling for error variance in predictor and outcome variables.

Of the predictors that accounted for unique variability,relational victimization was the most consistent con-tributor of unique variance to the prediction of boys’and girls’ concurrent loneliness and low self-esteem,after we partialled out the shared variability among theother predictors (i.e., overt forms of victimization,overt aggression, and relational aggression). The find-ings also revealed that for both boys and girls, overt ag-gression was uniquely associated with externalizingbehavior.

Significant gender interactions were also revealed (p< .05), suggesting that aggression and victimization aredifferentially related to adjustment for boys and girls.First, relational aggression toward peers was associatedwith externalizing behavior for girls but not for boys.Second, overt victimization was associated with de-pression symptoms for boys but not for girls.

Social–Psychological Adjustment ofAdolescents Who Are Victims ofRelational and Overt Aggression

To examine the social–psychological adjustment ofadolescents who are victims of both relational and overtaggression, and to test the effect of sex, factorialMANOVAs were conducted. Although this analyticstrategy required the dichotomization of continuousvariables, thereby reducing variability, the use ofMANOVAs did allow for powerful testing of the rolesof aggression, victimization, and sex in one analysis.Replicating a procedure used in prior work (e.g., Crick& Bigbee, 1998), groups of relational aggressors andvictims were created for adolescents with frequenciesof relational victimization or overt victimization onestandard deviation above the mean. This identified fourdistinct groups of adolescents: relational victims only(boys, n = 22; girls, n = 31), overt victims only (boys, n= 23; girls, n = 21), both relational and overt victims(boys, n = 23; girls, n = 13), and neither relational norovert victims (boys, n = 185; girls, n = 248). Chi-squareanalyses revealed a marginally significant difference inthe sex distribution across these four victimization

485

OVERT AND RELATIONAL AGGRESSION

Table 3. Unique Contribution of Relational Aggression and Victimization to the Prediction of Concurrent Social–PsychologicalAdjustment

Aggression Victimization

Step 1: R2 for Overt Step 2: r2∆ for Relational Step 1: R2 for Overt Step 2: r2∆ for Relational

BoysDepression symptoms .07* .02 .28* .04*Loneliness .01 .03 .13* .06*Self-esteem .04 .01 .07* .06*Externalizing symptoms .19* .01 .10* .02

GirlsDepression symptoms .06* .01 .08* .09*Loneliness .00 .00 .05* .12*Self-esteem .01 .00 .03 .08*Externalizing symptoms .27* .03* .09* .00

*p < .001.

Table 4. Relative Contributions of Overt and Relational Aggression and Victimization to the Prediction of Concurrent Social–Psychological Adjustment

OvertAggression

RelationalAggression

OvertVictimization

RelationalVictimization Total R2

Total SharedVariance

BoysDepression symptoms .03 (.04) .09 (.12) .27 (.35)* .18 (.23) .34* .23Loneliness –.09 (–.11) .11 (.14) .14 (.18) .22 (.29)* .20* .11Self-esteem –.03 (–.04) –.07 (–.08) –.04 (–.06) –.21 (–.28) .14* .09Externalizing symptoms .25 (.32)* .08 (.09) .13 (.17) .07 (.09) .25* .16

GirlsDepression symptoms .11 (.14) .02 (.02) .09 (.10) .26 (.29)* .17* .08Loneliness –.01 (–.02) –.09 (–.10) .08 (.09) .35(.40)* .18* .04Self-esteem –.05 (–.07) .02 (.02) –.02 (–.03) –.27 (–.31)* .11* .03Externalizing symptoms .32 (.39)* .17 (.20)* .08 (.10) .00 (.00) .31* .17

Note: Numbers are semi-partial correlations (and betas).*p < .001.

With error variance accounted for, LISREL can derive more accuratepath coefficients and estimates of explained variance between con-structs by eliminating extraneous error variance in each variable.

groups, χ2(3) = 7.29, p = .06, suggesting that boys weremore likely than girls to be both relational and overtvictims.

A 2 (sex) × 4 (victimization group) MANOVA con-ducted on the set of four dependent variables of social–psychological adjustment revealed a significantmultivariate main effect for victimization group,Wilks’s L (12, 1366) = 10.20, p < .0001, and for sex,Wilks’s Λ (4, 516) = 4.99, p < .0001, but no significantinteraction effect, Wilks’s Λ (12, 1366) = .52, ns (seeTable 5 for means). Overall, the results consistently re-vealed that adolescents who were both relational andovert victims had higher levels of depression,externalizing behavior, and loneliness compared withadolescents victimized either relationally or overtlyonly, followed by adolescents who were not victimized(see Table 5).

Social–Psychological Adjustment ofAdolescents Who Are Relational andOvert Aggressors

We identified four groups of aggressors (i.e., rela-tional aggressor only, overt aggressor only, both rela-tional and overt aggressor, and neither relational norovert aggressors) by using the strategy described previ-ously. Chi-square analyses revealed that boys were sig-nificantly more likely than girls to be overt aggressorsonly or both overt and relational aggressors, χ2(3) =22.11, p < .0001 (see Table 6). A 2 (Sex) × 4 (Aggres-sion Group) MANOVA was conducted to examinewhether adolescents who were both relationally andovertly aggressive experienced more social–psycho-logical maladjustment than teens who used only one orno form of aggression. Significant multivariate main ef-fects for sex, Wilks’s Λ (4, 516) = 7.80, p < .0001, andaggression group, Wilks’s Λ(12, 1366) = 10.20, p <.0001, were qualified by a significant interaction effect,Wilks’s Λ(12, 1366) = 2.40, p < .01. This interaction ef-fect was significant at a univariate level for adolescentdepression, F(3, 519) = 3.11, p < .05; loneliness, F(3,519) = 4.36, p < .01; and externalizing behavior, F(3,519) = 2.75, p < .05. As shown in Table 6, adolescents

who were overt aggressors only or both overt and rela-tional aggressors had significantly higher levels ofexternalizing behavior than other adolescents. Addi-tionally, within the group of adolescents who wereovert aggressors only, girls had significantly greater de-pression and lower self-esteem than boys. For adoles-cents who were relational aggressors only and bothrelational and overt aggressors, boys had significantlygreater loneliness than girls.

Buffering Effect of Close Friend SocialSupport for Peer Victimization andAdolescents’ Social–PsychologicalAdjustment

The final goal of this study was to examine a buffer-ing effect of social support from a close friend in the re-lation between peer victimization and social–psychological adjustment. Because close friend socialsupport was a negatively skewed variable (see Table 2for means and standard deviations), a dummy variablewas computed for adolescents’ close friend social sup-port to divide those with scores ≤1 SD below the mean(0) and ≥1 SD above the mean (1), thus identifying ado-lescents with or without substantial close friendshipsupport. By using this subset of the original sample (n =299), we conducted a hierarchical multiple regressionincluding overt and relational forms of victimizationand the dummy-coded close friend support variable onan initial step, and two interaction terms (Overt Victim-ization × Close Friend Support; Relational Victimiza-tion × Close Friend Support) on a second step. Theinteraction terms added significantly to the regressionmodel predicting externalizing behavior (r2∆ = .02, p <.05), and a significant interaction between close friendsupport and relational victimization was revealed (β = –.49, p < .01) for this model. Correlation coefficientswere computed to explore the nature of this interactioneffect, and these results revealed that for adolescentswith low close friend social support, relational victim-ization was significantly associated with externalizingbehavior (r = .39, p < .001). In contrast, for adolescentswith high levels of close friend social support, there was

486

PRINSTEIN, BOERGERS, VERNBERG

Table 5. Means and Standard Deviations of Social–Psychological Adjustment for Adolescents Who Are Relationally and/orOvertly Victimized

Neither Relationalnor Overt Relational Only Overt Only

Both Relational andOvert

M SD M SD M SD M SD

Depression 1.73 .48a 2.00 .48b 2.06 .53b 2.39 .63c

Self-esteem 3.16 .70a 2.71 .82b 2.82 .73b 2.51 .71b

Loneliness 1.73 .42a 2.05 .45b 2.05 .48bc 2.30 .47c

Externalizing 1.47 .39a 1.54 .41ab 1.69 .47b 1.94 .40c

Note: Row means with different superscripts are significantly different (Tukey honestly significant difference, p < .05).

487

OVERT AND RELATIONAL AGGRESSION

Tabl

e6.

Mea

nsan

dSt

anda

rdD

evia

tion

sof

Soci

al–P

sych

olog

ical

Adj

ustm

entf

orA

dole

scen

tsW

hoA

reR

elat

iona

lly

and/

orO

vert

lyA

ggre

ssiv

e

Boy

sG

irls

Nei

ther

Rel

atio

naln

orO

vert

(n=

188)

Rel

atio

nal

Onl

y(n

=16

)O

vert

Onl

y(n

=28

)B

oth

Rel

atio

nal

and

Ove

rt(n

=21

)

Nei

ther

Rel

atio

naln

orO

vert

(n=

272)

Rel

atio

nal

Onl

y(n

=21

)O

vert

Onl

y(n

=11

)B

oth

Rel

atio

nal

and

Ove

rt(n

=9)

MSD

MSD

MSD

MSD

MSD

MSD

MSD

MSD

Dep

ress

ion

1.67

.44a

1.92

.57a

b1.

87.4

2ab

2.09

.57b

1.84

.54a

1.93

.54a

2.61

.49b

2.27

.45a

b

Self

-est

eem

3.14

.68

2.74

.82

3.05

.61

2.67

.68

3.05

.78

3.09

.72

2.60

.51

2.67

.95

Lon

elin

ess

1.81

.44a

2.16

.35a

b1.

81.4

4ab

2.13

.56b

1.78

.46

1.81

.53

2.10

.63

1.66

.37

Ext

erna

lizin

g1.

51.4

2a1.

66.3

8ab

1.84

.30b

2.03

.41b

1.40

.33a

1.59

.35a

1.98

.51b

2.30

.33b

Not

e:W

ithin

sex,

row

mea

nsw

ithdi

ffer

ents

uper

scri

pts

are

sign

ific

antly

diff

eren

t.M

eans

inbo

ldre

pres

ents

igni

fica

ntge

nder

diff

eren

ces

with

inag

gres

sion

grou

p.

no significant relation between relational victimizationand externalizing behavior (r = .12, ns), thus supportinga buffering hypothesis for the effect of close friend so-cial support. Separate analyses conducted by sex re-vealed no meaningful differences in this interactioneffect.

Discussion

This study is among the first to examine relationaland overt forms of aggression in adolescents and tostudy associations between both aggression and vic-timization in predicting adolescents’ concurrent so-cial–psychological adjustment. Results from this studyoffer an important extension to the growing literatureon overt and relational forms of aggression and victim-ization and provide preliminary evidence to supportseveral new hypotheses regarding relational aggressionand victimization as important contributors to adoles-cent social–psychological adjustment.

Several findings from previous work on relationalaggression and victimization in elementary school-agechildren were replicated in this study on adolescents.First, as with younger children, adolescents were suc-cessfully able to discriminate between relational andovert forms of aggression as well as relational and overtforms of victimization. Moreover, the correlations be-tween these forms of aggression and of victimizationsuggested that these are distinct constructs (Crick &Bigbee, 1998; Crick, Casas, & Ku, 1999) and may beimportant to assess for adolescents.

Also as demonstrated in prior work, overt forms ofaggression and victimization appeared to be more prev-alent among boys compared with girls, whereas rela-tional forms were reported with comparablefrequencies across sexes. This is consistent with thegender patterns of aggression and victimization re-ported in several prior studies in middle childhood(e.g., Crick & Grotpeter, 1996). However, examinationof effect sizes in this study suggested that the actualgender differences in the frequency of overt aggressionand overt victimization were not substantial. This islikely due to the overall low frequencies of overt ag-gression reported by adolescents in this sample, whichhas been observed previously during adolescence com-pared with middle childhood (Cairns et al., 1989).

Prior work also has suggested that relational aggres-sion and victimization contribute uniquely to the pre-diction of concurrent and future social–psychologicaldifficulties, particularly for girls (Crick & Bigbee,1998). The results from this study partially replicatedthese results for adolescents. Despite relatively low re-ported levels of adolescent aggression and victimiza-tion, the results revealed that these social experienceswere important contributors to understanding adoles-cent adjustment, with significant findings indicating

that relational aggression explained a significant pro-portion of variance in girls’ externalizing behavior.More notably, however, relational victimization ex-plained variability in social–psychological adjustmentafter we controlled for associations with overt victim-ization and the shared variability between overt and re-lational forms of victimization. As indicated in priorresearch, the role of relational victimization, comparedwith overt victimization, was substantial in relation togirls’ internalizing outcomes (i.e., depression, loneli-ness, self-esteem).

In addition to this important extension of past resultson children’s relational aggression and victimization toa diverse group of adolescents, a main goal of this studywas to examine the relative associations among rela-tional and overt forms of aggression and victimizationwith concurrent psychological adjustment, which wasparticularly important given that both aggression andvictimization have been linked with similar adjustmentoutcomes. In analyses conducted to examine these rela-tive contributions, findings consistently revealed thatafter controlling for the shared variability among theseconstructs, adolescents’ aggression toward their peerswas associated with greater externalizing symptoms.However, this overall effect was qualified by poten-tially important gender differences. For example, al-though girls’ reports of their own relational aggressiontoward peers explained additional variance inexternalizing symptoms, this was not found for boys.Externalizing symptoms measured here were drawnfrom diagnostic criteria for oppositional defiant disor-der (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), and these find-ings suggest that perpetrating relational aggressiontoward peers (e.g., telling rumors, excluding peers fromactivities), along with overt aggression, is a notableconcomitant of these disruptive behavior disorders foradolescent girls but not for boys. Inquiry regarding anadolescent’s use of relational aggression may be impor-tant in clinical assessments of girls who present withovert aggression and other disruptive behaviors andalso may be a critical focus of interventions.

In contrast to the findings on externalizing behaviorand forms of peer aggression, the findings indicatedthat adolescents who were the targets of peers’ aggres-sion, particularly through relational victimization, alsoreported higher levels of internalizing symptoms com-pared with other teens. This was true for both boys andgirls after we controlled for variance shared by otherRPEQ subscales. This supports the view that relationalvictimization is troubling to many adolescents regard-less of sex and is a feature associated with higher levelsof depression symptoms, higher levels of loneliness,and lower global self-worth. For boys, but not for girls,overt victimization also was associated with depressionsymptoms, which is consistent with past work on boys’overt victimization. Thus, the results supported thegeneral idea that relational victimization may contrib-

488

PRINSTEIN, BOERGERS, VERNBERG

ute to adolescents’subjective distress, and overt victim-ization, which is reported with higher frequency forboys, also contributes to boys’ adjustment.

These concurrent associations also allow for at leasttwo alternate interpretations. First, rather than the uni-directional prediction of adjustment difficulties fromaggression and victimization, these factors may mutu-ally contribute to one another. This transactional modelsuggests that victimization indeed may predict concur-rent and prospective psychological adjustment (Crick,1996; Vernberg, 1990) but also that adolescents experi-encing adjustment difficulties may be more vulnerableto subsequent victimization by peers (Crick & Bigbee,1998; Parker at al., 1995; Vernberg, 1990). Similarly,peer aggression may be exacerbated by adjustment dif-ficulties and contribute to future maladjustment. Sec-ond, it is possible that adolescents with social–psychological adjustment difficulties are more likely toperceive peers’ behavior as aggressive and thus reporthigher levels of victimization (Lochman & Dodge,1994; Quiggle, Garber, Panak, & Dodge, 1992). Thissocial–information processing perspective also sug-gests a transactional model, given that prior negativepeer experiences may have contributed to the develop-ment of this cognitive bias (Crick, Grotpeter, &Rockhill, 1999), which subsequently potentiates futurenegative peer experiences. Overall, these findings areconsistent with each of these models of peer aggres-sion, peer victimization, and adjustment.

It was also of interest to examine whether adoles-cents who exhibited co-occurring relational and overtforms of aggression or reported both relational andovert forms of victimization experienced more adjust-ment difficulties than the perpetrators or victims of oneform of aggression alone, because this question rarelyhas been examined and never before has been investi-gated for adolescents. Indeed, the findings consistentlyindicated that the most severely maladjusted adoles-cents were best identified by assessing both relationaland overt forms of aggression and victimization. Ado-lescents who were victimized by peers through both re-lational and overt aggression had higher levels ofdepression, loneliness, and externalizing behaviorcompared with adolescents who were victims of eitherrelational or overt aggression alone. It would be inter-esting to assess the sources of victimization, to betterunderstand whether these adolescents who are victim-ized through both overt and relational means are in facttargeted by multiple groups of aggressors who use dif-ferent strategies of victimization or by one set of peerswith multiple forms of aggression in their arsenal. Theresults from this study suggested that some teens whoare aggressive use both relational and overt means andare significantly more likely to be boys.

Among aggressive adolescents, teens who used gen-der non-normative forms of aggression appeared to beat somewhat heightened risk for maladjustment (Crick,

1997). For instance, overt aggression is often closelyassociated with boys and may be considered atypicalwhen exhibited by girls. Consistent with this idea, andwith prior results on younger children (Crick, 1997),overtly aggressive girls in this sample accordingly hadlower self-esteem and more depressive symptoms thanovertly aggressive boys. Similarly, boys who used rela-tively high levels of relational aggression (a character-istic typically associated with girls), either exclusivelyor in conjunction with overt aggression, had higher lev-els of loneliness than relationally aggressive girls. Insum, teachers and clinicians may be guided by two as-pects of these findings. First, assessment of aggressiveadolescents should include an examination of both rela-tional and overt forms of aggression; and second, teens’use of aggression that is stereotypically gendernonnormative may be a good marker of internalizeddistress.

The final goal of this investigation was directed spe-cifically toward intervention efforts by examining thebuffering role of close friendship support in the contextof relational victimization. We hypothesized that socialsupport within the context of a close friendship may bean active mechanism responsible for the finding thatfriendless, victimized children are more likely to expe-rience distress than victimized children who have aclose friend. In support of this hypothesis, our findingsindicated that high levels of close friendship supportmitigated the association between relational victimiza-tion and social–psychological maladjustment, specifi-cally ODD/CD symptoms. These findings corroborateprior results on the importance of close friendships as aprotective factor for youth otherwise vulnerable to ad-justment difficulties (Hartup, 1996; Hodges et al.,1999). Thus, adolescents perhaps would be well ad-vised to solicit support from their close friends to copewith relational victimization. However, this strategymay prove especially difficult when both relational vic-timization and social support occur within the contextof the same friendship.

In sum, this investigation provides an important ex-tension of prior work on relational aggression and vic-timization by examining these constructs in a samplethat is different in ethnic composition and developmen-tal period than has been included in prior work. Thisstudy also offers new insight into the relative and com-bined effects of overt and relational aggression and vic-timization on social–psychological adjustment. Futurework would benefit by addressing some of the limita-tions of this investigation. For instance, although it wasof interest in this study to examine adolescents’percep-tions of overt and relational forms of aggression andvictimization, future work may also include peers’ re-ports of these behaviors. The use of exclusively self-re-port data in this investigation allowed for the possibilitythat significant associations were due to shared methodvariance, which could make it difficult to rule out a ten-

489

OVERT AND RELATIONAL AGGRESSION

dency for distressed teens to overreport the frequencyof their aggressive behavior or victimization frompeers. Although this is a significant issue that should beaddressed in future work, the results from this studyprovided some evidence that this effect may not haveunduly affected the study findings. First, we selected ameasure that has demonstrated good correspondence toexternal informants’ reports of aggression and victim-ization and is similar in format to measures that have re-vealed no significant reporting bias (Crick & Bigbee,1998). Second, the findings revealed discriminant asso-ciations, in that not all subscales were significantlyintercorrelated in regression analyses, as would likelybe the case if method variance or bias was predomi-nantly responsible for significant associations. More-over, because it is unlikely that a reporting bias wouldexist for only a specific subset of the sample (e.g., forboys but not for girls), analyses examining group differ-ences, gender effects, and moderating variables wereless likely to be affected by a possible bias. Last, enter-ing variables as a block in multiple regression proce-dures provided some statistical control of possiblemethod variability. By examining the unique associa-tions between aggression and victimization predictorsafter their shared variability with each outcome waspartialled, we could consider relationships after con-trolling for common shared variance. Nevertheless, thisissue remains an important limitation, and future workwould benefit from the use of multiple reporters whenidentifying overt and relational aggressors and victims.

Another important issue for future work in this areawill be to obtain longitudinal data that would furtherclarify the direction of effect between social–psycho-logical adjustment and relational aggression and vic-timization and, in particular, to examine possiblereciprocal associations. Most interestingly, longitudi-nal work may benefit by focusing specifically on devel-opmental junctures during which increases inaggression and victimization are most likely to identifycritical periods of psychological risk.

The examination of relational aggression and vic-timization within an ethnically diverse sample in thisstudy allowed for an important extension of past re-search, given that prior work has so rarely included sub-stantial proportions of participants of color. The resultsrevealed no differences in the frequencies of aggressionor victimization across ethnic groups or significant dif-ferences in the associations among aggression, victim-ization, and adjustment. This finding may have beeninfluenced by the exceptional diversity and integrationof the school from which these data were collected.Replication studies based in multiple schools or in dis-tricts with a defined minority group may reveal differ-ent findings. Subsequent investigators may wish toexamine whether some forms of victimization may betargeted specifically toward minority or majoritygroups. Further investigations also may examine

whether there exist qualitatively different forms of ag-gression perpetrated by teens within the same ethnicgroup, compared with aggression toward a member of adifferent ethnic group, and how these intraethnic andinterethnic victimization experiences may differen-tially impact adjustment.

Future work would benefit from increased attentionto theoretical models that will begin to explicate themanner in which relational forms of aggression and vic-timization develop, the process by which they lead tosubsequent adjustment difficulties, and the associatedpsychosocial factors that also contribute to similar out-comes. This would provide an important extension andelaboration to research over the past half-decade that,along with this study, has supported the importance ofrelational aggression and victimization for children andadolescents across development, for boys and girls, andfor samples of ethnically and financially diverse youth(Crick, 1996; Crick et al., 1999; Werner & Crick, 1999).This work also would benefit from investigating chil-drenandadolescents frombothnormativeandclinicallyreferred samples to better examine aggression, victim-ization, and adjustment across a broader range of sever-ity than has been included in prior studies on relationalaggression and victimization.

Overall, this study suggested that relational forms ofaggression and victimization are distinct constructsamong adolescents and may be particularly relevant forthis developmental stage compared with overt behav-iors. The findings also suggested that, when examiningadolescents’ psychological adjustment, researchersshould consider overt forms of aggression and victim-ization in conjunction with relational aggression andvictimization as well as social support from closefriends. Identification of adolescents who arerelationally aggressive or relationally victimized willbe important for understanding varied social–psycho-logical adjustment outcomes.

References

Achenbach, T. M., McConaughy, S. H., & Howell, C. T. (1987).Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: Implica-tions of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity.Psychological Bulletin, 101, 213–232.

Boivin, M., Hymel, S., & Bukowski, W. M. (1995). The roles of so-cial withdrawal, peer rejection, and victimization by peers inpredicting loneliness and depressed mood in childhood. Devel-opment and Psychopathology, 7, 765–786.

Boulton, M. J., & Underwood, K. (1992). Bully/victim problemsamong middle school children. British Journal of EducationalPsychology, 62, 73–87.

Brown, B. B. (1989). The role of peer groups in adolescents– adjust-ment to secondary school. In T. J. Berndt & G. W. Ladd (Eds.),Peer relationships in child development (pp. 188–215). NewYork: Wiley.

Cairns, R. B., Cairns, B. D., Neckerman, H. J., Ferguson, L. L., &Gariépy, J. L. (1989). Growth and aggression: 1. Childhood toearly adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 25, 320–330.

490

PRINSTEIN, BOERGERS, VERNBERG

491

OVERT AND RELATIONAL AGGRESSION

Census of Population and Housing. (1990). Bureau of the Census:1990 census of population and housing. Washington, DC: Bu-reau of the Census.

Champion, K. M. (1997). Bullying in middle school: Exploring theindividual and interpersonal characteristics of the victim. Un-published doctoral dissertation, University of Kansas,Lawrence.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Kupersmidt, J. B. (1990). Peer group be-havior and social status. In S. R. Asher & J. D. Coie (Eds.), Peerrejection in childhood. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. (1985). Stress, social support, and the bufferinghypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357.

Creusere, M. (1999). Theories of adults’ understanding and use ofirony and sarcasm: Applications to and evidence from researchwith children. Developmental Review, 19, 213–262.

Crick, N. R. (1995). Relational aggression: The role of intent attribu-tions, feelings of distress, and provocation type. Developmentand Psychopathology, 7, 313–322.

Crick, N. R. (1996). The role of overt aggression, relational aggres-sion, and prosocial behavior in the prediction of children’s fu-ture social adjustment. Child Development, 67, 2317–2327.

Crick, N. R. (1997). Engagement in gender normative versusnonnormative forms of aggression: Links to social–psychologi-cal adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 33, 610–617.

Crick, N. R., & Bigbee, M. A. (1998). Relational and overt forms ofpeer victimization: A multiinformant approach. Journal of Con-sulting and Clinical Psychology, 66, 337–347.

Crick, N. R., Casas, J. F., & Ku, H. C. (1999). Relational and physicalforms of peer victimization in preschool. Developmental Psy-chology, 35, 376–385.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational aggression, gen-der, and social–psychological adjustment. Child Development,66, 710–722.

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1996). Children’s treatment by peers:Victims of relational and overt aggression. Development andPsychopathology, 8, 367–380.

Crick, N. R., Grotpeter, J. K., & Rockhill, C. M. (1999). A social in-formation-processing approach to children’s loneliness. In K. J.Rotenberg & S. Hymel (Eds.), Loneliness in childhood and ado-lescence. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Galen, B. R., & Underwood, M. K. (1997). A developmental investi-gation of social aggression among children. DevelopmentalPsychology, 33, 589–600.

Harter, S. (1988). Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Adoles-cents. Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Harter, S. (1989). Manual for the Social Support Scale for Childrenand Adolescents. Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Hartup, W. W. (1996). The company they keep: Friendships and theirdevelopmental significance. Child Development, 67, 1–13.

Hodges, E. V. E., Boivin, M., Vitaro, F., & Bukowski, W. M. (1999).The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycleof peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 35, 94–101.

Hogue, A., & Steinberg, L. (1995). Homophily of internalized dis-tress in adolescent peer groups. Developmental Psychology, 31,897–906.

Lochman, J. E., & Dodge, K. A. (1994). Social–cognitive processesof severely violent, moderately aggressive, and nonaggressiveboys. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 62, 366–374.

Lopez, C. (1998). Peer victimization: Preliminary validation of aself-report measure for young adolescents. Presented at the So-ciety for Research on Adolescence, San Diego, California.

Lucas, C., Zhang, H., Fisher, P., Shaffer, D., Regier, D., Narrow, W.,Bourdon, K., Dulcan, M., Canino, M., Rubio-Stipec, M., Lahey,B., & Friman, P. (1999). The DISC Predictive Scales (DPS): Ef-ficiently screening for diagnosis. Manuscript submitted forpublication.

Olweus, D. (1992). Victimization by peers: Antecedents and longterm outcomes. In K. H. Rubin & J. B. Asendorph (Eds.), Socialwithdrawal, inhibition, and shyness in childhood. Hillsdale, NJ:Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1987). Peer relations and later personaladjustment: Are low-accepted children at risk? PsychologicalBulletin, 102, 357–389.

Parker, J. G., Rubin, K. H., Price, J. M., & DeRosier, M. E. (1995).Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A devel-opmental psychopathology perspective. In D. Cicchetti & D. J.Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology (Vol. II). NewYork: Wiley.

Quiggle, N. L., Garber, J., Panak, W. F., & Dodge, K. A. (1992). So-cial information processing in aggressive and depressed chil-dren. Child Development, 63, 1305–1320.

Roberts, R. E., Andrews, J. A., Lewinsohn, P. M., & Hops, H. (1990).Assessment of depression in adolescents using the Center forEpidemiological Studies Depression scale. Psychological As-sessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2,122–128.

Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The RevisedUCLA–Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validityevidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39,472–480.

Shaffer, D., Fisher, P., Dulcan, M. K., Davies, M., Piacentini, J.,Schwab-Stone, M. E., Lahey, B. B., Bourdon, K., Jensen, P. S.,Bird, H. R., Canino, G., & Regier, D. A. (1996). The NIMH Di-agnostic Interview Schedule for Children 2.3 (DISC 2.3): De-scription, acceptability, prevalence rates, and performance inthe MECA study. Methods for the Epidemiology of Child andAdolescent Mental Disorders Study. Journal of the AmericanAcademy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 865–877.

Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. NewYork: Norton.

Vernberg, E. M. (1990). Psychological adjustment and experienceswith peers during early adolescence: Reciprocal, incidental, orunidirectional relationships? Journal of Abnormal Child Psy-chology, 18, 187–198.

Vernberg, E. M., Fonagy, P., & Twemlow, S. (2000). Preliminary re-port of the Topeka Peaceful Schools Project. Topeka, KS:Menninger Clinic.

Vernberg, E. M., Jacobs, A. K., & Hershberger, S. L. (1999). Peer vic-timization and attitudes about violence during early adoles-cence. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 28, 386–395.

Werner, N. E., & Crick, N. R. (1999). Relational aggression and so-cial–psychological adjustment in a college sample. Journal ofAbnormal Psychology, 108, 615–623.

Winner, E. (1988). The point of words: Children’s understanding ofmetaphor and irony. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UniversityPress.

Manuscript received June 30, 2000Final revision received February 1, 2001